1. Introduction

Climate change is not just an environmental crisis but also a profound sociological issue, deeply intertwined with socio-structural factors that shape human behavior, institutions, and power relations [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Its effects are felt globally, but the burdens are unevenly distributed, with marginalized communities often bearing the brunt of its consequences [

5,

6,

7]. This disparity highlights the urgent need for climate justice, which seeks to address the inequities in both the causes and impacts of climate change. At its core, the fight for climate justice is a call for the transformation of social, political, and economic structures that perpetuate environmental degradation and inequality.

Environmental sociology plays a critical role in understanding the multifaceted nature of climate change. It examines how institutions, cultural beliefs, values, and social practices contribute to environmental destruction and offers insights into how these systems can be transformed to promote sustainability and equity. As such, climate change is a deeply sociological concern [

1,

3,

8]. Sociology brings two essential approaches to the study of climate change: first, it provides tools to analyze the causes and consequences of the crisis, and second, it offers a form of social critique that challenges dominant socioeconomic practices and belief systems [

1,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. This essay explores the environmental sociology of climate change, with a particular focus on the need for climate justice, by expanding on these ideas.

Climate change is primarily socio-structural in nature, driven by human activities embedded within broader systems of production, consumption, and governance. These activities, particularly those related to the extraction and use of fossil fuels, deforestation, and industrial agriculture, are deeply rooted in global capitalist systems that prioritize economic growth over ecological sustainability [

8,

14]. The environmental consequences of these practices are vast, from rising global temperatures to more frequent extreme weather events, and these impacts are disproportionately experienced by vulnerable populations, particularly in the Global South.

As Islam and Kieu note, climate change is not just a product of human actions but of the social systems that facilitate those actions [

8]. For instance, global economic structures incentivize the extraction and burning of fossil fuels, while political institutions often fail to adequately regulate or mitigate the environmental impacts of industrial activities. Moreover, cultural beliefs that equate progress with material consumption and technological advancement further entrench unsustainable practices. This socio-structural understanding of climate change emphasizes the need for systemic change to address both the root causes and the unequal impacts of the crisis [

15,

16,

17].

After this brief introduction, the second section of the paper delves into sociological approaches to climate change, exploring how these perspectives illuminate the social dimensions of the climate crisis. The third section shifts focus to the pressing need for a social justice framework, examining various forms of inequality and injustice that exacerbate climate impacts. In the fourth section, the paper draws on three key traditions in environmental sociology—such as the New Ecological Paradigm, post-growth society, and environmental justice paradigms—to develop an integrative climate justice model. This model offers a comprehensive framework that addresses both environmental sustainability and social equity. Finally, the fifth section concludes by discussing the broader implications of this new climate justice model, considering its potential to influence future policy, research, and global climate governance.

2. Sociological Approaches to Climate Change

As alluded to earlier, Sociology brings two distinct and advantageous approaches to understanding and addressing climate change. First, it provides the tools to analyze the social dimensions of the crisis, including its causes, consequences, and potential solutions. Second, it offers a form of social critique that challenges the dominant ideologies and practices that contribute to environmental degradation [

3,

18].

2.1. Analyzing the Causes and Consequences of Climate Change

One of the key contributions of sociology to the study of climate change is its ability to analyze the social forces that drive environmental degradation. Sociologists such as Robert Brulle and his colleagues, for example, argue that climate change is not simply the result of individual actions but is deeply embedded in social structures, particularly those related to capitalism and neoliberalism [

19]. These systems prioritize economic growth and the accumulation of wealth, often at the expense of environmental sustainability. The result is a global economy that is dependent on fossil fuels, deforestation, and other environmentally destructive practices [

1,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

In addition to examining the causes of climate change, sociology also provides insights into its social consequences. Climate change disproportionately affects marginalized groups, including low-income communities, indigenous peoples, and nations in the Global South. These groups often have less capacity to adapt to the impacts of climate change, such as rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and food insecurity. As such, the environmental crisis is also a social justice issue, with the most vulnerable populations bearing the brunt of its effects [

25,

26].

Climate justice, therefore, demands not only the mitigation of climate change but also the redistribution of resources and power to ensure that marginalized communities are protected and empowered to adapt to the changing climate. This requires a critical examination of global economic and political systems, as well as the development of policies that prioritize equity and sustainability.

2.2. Social Critique: Challenging Dominant Ideologies and Practices

The second key contribution of sociology to the study of climate change is its role in providing social critique. Sociologists have long challenged the belief systems and practices that contribute to environmental degradation, particularly those related to capitalism, consumerism, and technological optimism [

14,

23,

24,

27]. One of the central critiques offered by sociologists is the reliance on technical fixes as a solution to climate change. While technological innovations such as renewable energy and carbon capture are undoubtedly important, they are insufficient to address the deeper social and economic structures that drive environmental degradation [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. As Giddens argues, the belief that climate change can be solved through technology alone ignores the fact that human behavior is shaped by social, political, and economic forces [

2]. Without addressing the underlying social drivers of climate change, technological solutions are likely to be limited in their effectiveness [

28,

29,

30].

Moreover, scholars such as Naomi Klein have critiqued the capitalist economic system for its role in driving environmental destruction. Klein argues that capitalism’s emphasis on growth and consumption is fundamentally incompatible with the ecological limits of the planet [

5]. Addressing climate change, therefore, requires a fundamental transformation of the global economic system, one that prioritizes sustainability and equity over profit and growth. This critique challenges the dominant economic paradigm and calls for a more holistic approach to addressing climate change.

3. The Imperative for Climate Justice

Climate justice is a concept that has gained prominence in recent years as activists, scholars, and policymakers have recognized the unequal distribution of the causes and impacts of climate change. It emphasizes the need to address the disproportionate burden of climate change on marginalized communities, particularly those in the Global South and in low-income communities in the Global North.

3.1. Inequality in Suffering and Responsibility in Climate Change

One of the key dimensions of inequality in addressing climate change is the disproportionate suffering experienced by poorer nations compared to wealthier ones [

31]. The world's most vulnerable populations, especially those in developing countries, bear the brunt of climate-related disasters for two reasons. First, they experience more frequent climate disasters, and second, their limited resources and capacities make them ill-prepared to manage and recover from these events [

30,

31,

32,

33].

According to Beck’s risk society theory, modern societies are defined by the anticipation of unprecedented risks, including the unpredictability of climate change. However, Beck’s view of these risks being equally distributed does not reflect the reality of the unequal burden borne by different nations. Islam’s concept of a “double-risk society” offers a more accurate framework to examine these disparities, highlighting that the Global South is far more vulnerable to climate-related risks than the Global North due to limited resources [

4].

In developing nations, the impact of climate disasters is magnified by a lack of financial, technological, and institutional capacities. For example, an earthquake in 1973 Nicaragua resulted in over 6,000 deaths, while a similar earthquake in 1971 California resulted in just 56. This discrepancy illustrates the stark differences in risk management between rich and poor nations [

34]. While both are exposed to risks, poorer nations are disproportionately affected due to inadequate infrastructure and preparation [

35,

36].

The Global South not only faces higher environmental risks but also receives a larger share of harmful environmental externalities. Toxic waste and hazardous materials are often offloaded onto these nations from wealthier countries. This redistribution of environmental burdens worsens their plight, creating a cycle of vulnerability in which the least responsible countries bear the heaviest impacts [

37,

38,

39,

40].

3.2. Inequities in Responsibility for Climate Change

Developed countries are largely responsible for the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions driving climate change, yet it is the developing nations that suffer the most from its consequences. Data shows that wealthier nations such as the U.S., Germany, and Russia remain top contributors to carbon dioxide emissions per capita. In contrast, countries like Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Nigeria, which emit less than one ton per capita, are disproportionately affected by climate-related disasters [

4,

25,

30].

This inequality is glaring in regions like Africa, where climate change has exacerbated existing challenges like droughts and floods. African nations contribute less than 8% of global emissions, yet suffer immensely from climate change impacts. Similarly, small island states are threatened by rising sea levels, unpredictable weather patterns, and devastating storms, despite contributing little to GHG emissions. Their very existence is at risk, as evidenced by the erosion of islands like the Kinilailau Islands [

41,

42].

The inequities in responsibility and suffering from climate change highlight the issue of climate injustice. Developing countries, which are the least responsible for climate change, are the ones most affected by it. Without addressing these inequalities, the gap between those contributing to and those suffering from climate change will only widen.

3.3. Power Imbalance in Global Climate Negotiations

Inequality in power dynamics also plagues the international response to climate change. In forums such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and its Conference of the Parties (COPs), poorer nations often find their interests marginalized. Wealthy nations, armed with superior financial and technical resources, dominate negotiations. They are backed by a large cadre of experts, while poorer nations lack the personnel and resources to effectively advocate for their interests [

43,

44]. For instance, most climate research, including that conducted by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), is produced by scientists from the Global North. As a result, the IPCC reports tend to focus more on adaptive policies that benefit wealthier countries, rather than mitigation strategies favored by developing nations. This imbalance in scientific and technical expertise skews climate negotiations in favor of wealthier countries, leaving poorer nations at a disadvantage [

5,

44].

An example of this power imbalance was seen during the 6th COP in The Hague in 2000, when the Group of 77 (G77) and China expressed dissatisfaction with decisions made in secretive "Green Room" meetings attended only by wealthier nations. The exclusion of poorer nations from key negotiations reflects the systemic marginalization of their interests in international climate talks [

25,

44].

3.4. Economic and Political Vulnerabilities

Developing nations are also constrained by their economic and political vulnerabilities. Many are burdened by debt and subject to the conditions imposed by multilateral financial institutions like the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF). These institutions often prioritize the interests of wealthier nations, further weakening the bargaining power of developing countries [

45,

46,

47]. The structural adjustment policies imposed on developing nations in the wake of the 1980s debt crisis undermined their national sovereignty and weakened their collective negotiating power. The process of debt management has made these nations more vulnerable to foreign influence, limiting their ability to pursue independent climate policies [

4,

48,

49].

Moreover, developing countries often find themselves locked into global supply chains where they are responsible for resource extraction and industrial production, while the environmental burdens, including pollution and GHG emissions, are outsourced from wealthier nations. This dynamic exacerbates the environmental degradation in developing countries, while wealthier nations reap the economic benefits without bearing the full environmental costs. In another twist of irony, the World Bank, which has funded numerous polluting projects in the Global South, was appointed interim trustee of the Green Climate Fund (GCF) in 2010. This fund was established to help developing nations cope with climate change, with the aim of raising

$100 billion annually by 2020. However, the involvement of the World Bank raises concerns about the potential conflicts of interest in how climate funds are managed and distributed [

5,

43,

50,

51].

3.5. Fragmentation and Weakening of Developing Nations' Negotiating Power

The political and economic vulnerabilities of developing nations have also led to fragmentation in their collective negotiating power. The once-unified “G77 + China” bloc, consisting of 134 developing countries, has splintered into various ad-hoc groups such as BASIC (Brazil, South Africa, India, and China), the Least Developed Countries (LDCs), and ALBA (Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America). Each group prioritizes its own interests in climate negotiations, weakening the collective bargaining position of developing nations [

5,

43].

This fragmentation was evident in the 2009 Copenhagen Accord and the subsequent Cancun Agreement in 2010, where the collective power of developing nations was diminished. The pursuit of national advantage and economic interests has led to a lack of unity among developing nations, further weakening their ability to influence global climate policy [

4,

5].

3.6. Obstacles to North-South Cooperation on Climate Change

The unequal distribution of power and responsibility in the global political and economic system has created major obstacles to international cooperation on climate change. Despite the success of the UNFCCC in engaging 154 states and the European Union in climate talks, disagreements over the principle of "differentiated responsibilities" have hindered progress [

41]. Wealthier nations, particularly the U.S., have been reluctant to commit to legally binding emission reductions, especially when fast-developing countries like China and India are not subject to similar restrictions. The U.S., for example, delayed its participation in the Kyoto Protocol, demanding that key developing nations also commit to emission reductions. Ultimately, the U.S. withdrew from the Protocol in 2001, citing concerns about its economic competitiveness [

5,

43].

On the other hand, developing nations argue that they should not bear the same responsibilities as wealthier countries, given their historical contributions to climate change and their need for economic development. Countries like China and India insist on their right to industrialize and have demanded that developed nations take responsibility for their own emissions [

5,

50].

3.7. The Role of Grassroots Movements

Grassroots movements have played a crucial role in advocating for climate justice, challenging the dominant systems of power and calling for more equitable and sustainable approaches to environmental governance. Movements such as the Global Climate Strike, led by young activists like Greta Thunberg, have brought attention to the need for urgent action on climate change, while indigenous movements around the world have emphasized the importance of protecting traditional lands and resources from environmental degradation [

6,

51].

These movements highlight the intersection of environmental and social justice, emphasizing that climate change cannot be addressed without also addressing issues of inequality, marginalization, and exploitation. The fight for climate justice, therefore, is not only about mitigating the effects of climate change but also about transforming the systems of power that perpetuate environmental and social inequality.

4. Towards an Integrated Climate Justice Approach

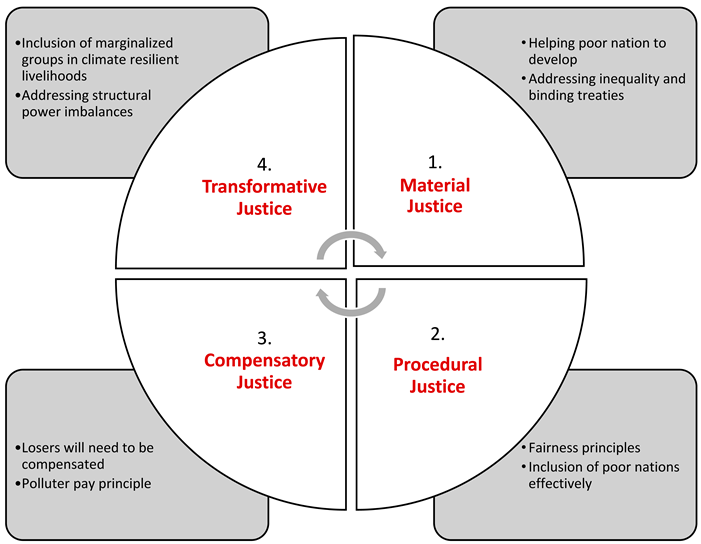

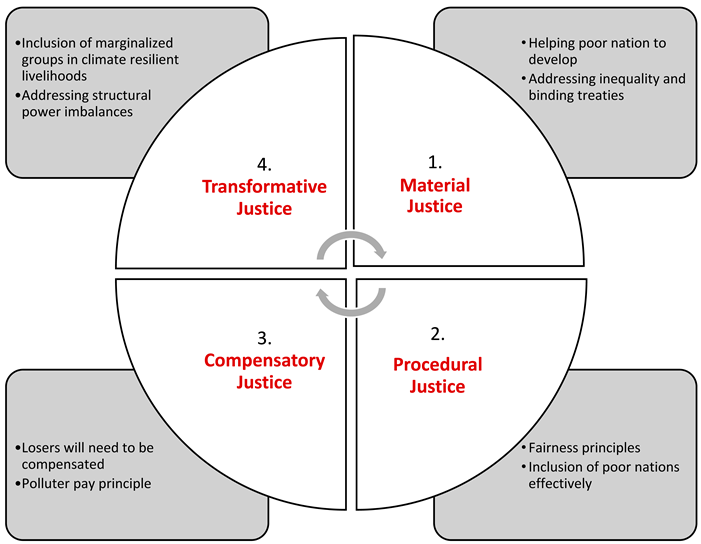

Environmental sociology provides critical frameworks for understanding the intersection of social systems and environmental crises, offering insights into how societies can achieve climate justice. Among the most influential paradigms are the New Ecological Paradigm (NEP), the Post-Growth Society, and the Environmental Justice paradigm. Together, these approaches form the basis for a comprehensive sociological model of climate justice that includes material justice, procedural justice, compensatory justice, and transformative justice. This section will first elaborate on these paradigms and then propose a unified model of climate justice.

4.1. The New Ecological Paradigm (NEP)

The New Ecological Paradigm (NEP), developed by Riley Dunlap and colleagues, challenges the traditional human-centered or anthropocentric worldview. It argues for a more eco-centric perspective, one that recognizes the interconnectedness of humans with the natural world. The NEP is rooted in four key principles [

52,

53,

54,

55]:

| No. |

Principles |

Elaboration |

| 1. |

Human Dependence on Nature |

The NEP stresses that humans are part of a larger ecological system. They depend on the finite biophysical environment for survival, contrary to the widely held belief that technology or human ingenuity can fully compensate for ecological degradation. |

| 2. |

Interconnectedness of Species: |

NEP emphasizes that humans are one among many species in the global ecosystem, and that all species are interconnected in a vast web of life. This recognition urges the protection of biodiversity and the acknowledgment that other species have the right to exist and thrive alongside humans. |

| 3. |

Limits to Growth |

This paradigm also emphasizes the finite nature of Earth's resources. The environment imposes constraints on human activity, and humanity cannot bypass the laws of ecology. The unchecked pursuit of growth, without regard to these limits, results in ecological crises. |

| 4. |

Ethical Obligations to Non-Human Entities |

The NEP asserts that plants, animals, and ecosystems possess intrinsic rights to exist independently of human needs or desires. Human exceptionalism—the belief that humans are exempt from ecological constraints—must be dismantled. |

In light of these principles, the NEP argues that environmental problems such as climate change are rooted in the dominance of human-centered worldviews. For climate justice to be realized, humans must acknowledge their role as part of nature and cease acting as if they are above ecological limits.

4.2. The Post-Growth Society

The concept of the Post-Growth Society, championed by thinkers like Gus Speth, challenges the capitalist obsession with GDP growth. This paradigm suggests that perpetual economic growth is not only unsustainable but also harmful to the environment and society. A post-growth society envisions an economic and social system that prioritizes well-being, environmental sustainability, and equity over GDP expansion [

56,

57]:

| No. |

Principles |

Elaborations |

| 1. |

Quality of Life Over Quantity of Growth |

In a post-growth society, the well-being of communities, the natural environment, and public health would take precedence over GDP growth. Economic policies would prioritize shorter workweeks, longer vacations, and a balanced life over material consumption. |

| 2. |

Rejection of Growth Mania |

Post-growth theorists argue that the pursuit of continuous economic growth is an illusion that exacerbates environmental degradation and social inequality. Instead, society should strive to develop in ways that improve social and environmental well-being. |

| 3. |

Reshaping Corporate Power |

The paradigm also suggests redefining corporate goals to align with social and environmental priorities. This would include dismantling corporate dominance and enacting pro-democracy reforms that limit the power of large corporations over environmental and economic policies. |

In the context of climate justice, a post-growth society offers a transformative model. By decoupling societal progress from economic growth, resources can be redistributed in a way that addresses environmental injustices, while simultaneously protecting the natural world.

4.3. The Environmental Justice Paradigm

The Environmental Justice (EJ) paradigm, developed by Robert Bullard and other scholars, examines how marginalized communities disproportionately bear the burden of environmental degradation due to unequal laws, regulations, and policies. Environmental justice seeks equitable treatment for all people, regardless of race, ethnicity, income, or geography, in the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental policies [

58,

59,

60,

61,

62]

| No. |

Principles |

Elaborations |

| 1. |

Fair Treatment |

Fair treatment in environmental justice means that no group should bear a disproportionate share of the negative environmental consequences resulting from industrial, governmental, or commercial operations. This principle challenges existing systems of environmental inequality, which often expose marginalized communities to greater risks of pollution and climate-related disasters. |

| 2. |

Meaningful Participation |

Environmental justice emphasizes the importance of meaningful participation, ensuring that marginalized and affected communities have a say in the decision-making processes that impact their lives. For climate justice, this means that those most affected by climate change—often communities in the Global South—must be included in global discussions and decision-making. |

| 3. |

Non-discrimination |

EJ mandates non-discriminatory environmental policies that do not disproportionately harm vulnerable populations. Historically, communities of color, indigenous peoples, and low-income groups have been systematically excluded from decision-making, resulting in environmental harm being concentrated in these communities. |

The EJ paradigm underscores the need for a climate justice framework that addresses systemic inequalities. To achieve climate justice, the impacts of climate change must be viewed through the lens of social justice, with a focus on protecting vulnerable communities.

4.4. Sociological Model of Climate Justice

Combining insights from these three paradigms, we can propose a comprehensive sociological model of climate justice that includes material, procedural, compensatory, and transformative justice.

4.4.1. Material Justice

Material justice refers to the equitable distribution of environmental goods (e.g., clean air, water, and land) and the burdens of environmental harm [

62]. In a climate justice framework, this means ensuring that the benefits of climate adaptation and mitigation efforts are shared fairly and that no group disproportionately bears the negative impacts of climate change.

4.4.2. Procedural Justice

Procedural justice involves fair and inclusive decision-making processes. Building on the EJ paradigm, it ensures that marginalized groups have meaningful participation in environmental governance [

5,

42]. Procedural justice in climate change mitigation would require that the voices of those most affected by climate change, such as indigenous peoples and climate refugees, are heard and respected in global climate negotiations.

4.4.3. Compensatory Justice

Compensatory justice seeks to rectify past injustices by providing compensation or reparations to those who have been harmed. In the context of climate justice, this means holding wealthy, industrialized nations accountable for their disproportionate contributions to greenhouse gas emissions and providing financial and technological support to vulnerable nations [

31].

4.4.4. Transformative Justice

Transformative justice in the context of climate action emphasizes not only addressing the immediate impacts of climate change but also creating long-term, systemic changes that foster inclusivity and equity. One critical aspect is the inclusion of marginalized groups in climate-resilient livelihoods. These communities, often the most vulnerable to climate impacts, must be empowered with access to sustainable resources, training, and opportunities to build resilience, ensuring their active participation in decision-making processes that shape their futures. Additionally, transformative justice addresses structural power imbalances by challenging the dominant political and economic systems that have historically marginalized these groups. It calls for the redistribution of resources, political influence, and decision-making power, enabling marginalized communities to not only survive but thrive in a climate-changed world. This holistic approach seeks to correct long-standing inequities while building a more just, inclusive, and resilient society [

58].

5. Conclusions

Climate change is one of the most pressing global challenges of the 21st century, and its root causes and impacts are deeply embedded in social structures. The environmental sociology of climate change emphasizes the need for climate justice, which seeks to address the unequal distribution of the causes and consequences of climate change. Sociology provides valuable tools for analyzing the social dimensions of the crisis and offers a critical perspective on the belief systems and practices that contribute to environmental degradation. Moving beyond technical fixes, the fight for climate justice requires systemic change that prioritizes sustainability, equity, and social justice.

As sociologists have argued, addressing climate change requires more than just technical fixes; it demands systemic change. This includes not only the development of renewable energy technologies and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions but also the transformation of social, political, and economic systems that prioritize profit and growth over sustainability and equity. Sociology’s emphasis on social critique and its focus on power relations make it a valuable tool for understanding and addressing the structural causes of climate change. By examining the ways in which social institutions, cultural beliefs, and power dynamics shape human behavior, sociology offers insights into how these systems can be transformed to promote sustainability and climate justice.

As shown in the paper, the inequalities in suffering, responsibility, and power between the Global North and South are central to the ongoing climate crisis. Developing nations, which contribute the least to global emissions, are disproportionately affected by climate change and marginalized in international climate negotiations. The structural inequalities embedded in the global political and economic system make it difficult to achieve a fair and effective global response to climate change. If these inequalities are not addressed, the gap between the nations contributing to and suffering from climate change will continue to grow, undermining the international community's ability to collectively address the climate crisis. Mutual trust and cooperation between North and South are crucial for achieving meaningful progress in tackling climate change and ensuring climate justice for all.

Environmental sociology offers profound paradigms, such as the NEP, the Post-Growth Society, and the Environmental Justice paradigm, that provide a comprehensive understanding of climate justice. These frameworks highlight the interconnectedness of humans and nature, the dangers of growth-oriented economies, and the importance of fair treatment for marginalized communities. A sociological model of climate justice must incorporate material, procedural, compensatory, and transformative justice, ensuring a holistic approach to addressing the climate crisis. This model emphasizes the need for systemic change, fair participation, and the protection of both vulnerable communities and the environment.

References

- Dunlap, R. E., & Brulle, R. J. Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives. Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Giddens, A. The Politics of Climate Change. Polity Press, 2009.

- Islam, M. S., & Kieu, E. Sociological Perspectives on Climate Change and Society: A Review. Climate, 2021, 9(7), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S. Development, Power and the Environment: Neoliberal Paradox in the Age of Vulnerability; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2013.

- Klein, N. This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate. Simon & Schuster, 2014. [CrossRef]

- McAdam, D. Social movements and climate change. Nature Climate Change, 2017, 7(3), 158-160.

- Okereke, C. Climate justice and the international regime. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Kieu, E. Tackling Regional Climate Change Impacts and Food Security Issues: A Critical Analysis across ASEAN, PIF, and SAARC. Sustainability 2020, 12, 883. [CrossRef]

- Kais, S.M.; Islam, M.S. Perception of Climate Change in Shrimp-Farming Communities in Bangladesh: A Critical Assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 672. [CrossRef]

- Bell, M.M. An Invitation to Environmental Sociology; Pine Forge Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004.

- Wiest, S.L.; Raymond, L.; Clawson, R.A. Framing, partisan predispositions, and public opinion on climate change. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2015, 31, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong-Parodi, G.; Feygina, I. Understanding and countering the motivated roots of climate change denial. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 42, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart-Pyatt, S.T.; Jorgenson, A.K.; Hamilton, L.C. Methodological Approaches for Sociological Research on Climate Change. In Climate Change and Society; Dunlap, R.E., Brulle, R.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 369–411. [Google Scholar]

- Schnaiberg, A. The Environment: From Surplus to Scarcity; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, A. The Refinement of Production: Ecological Modernization Theory and the Chemical Industry; Van Arkel: Utrech, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, M. Globalization and Environmental Reform: The Ecological Modernization of the Global Economy by Arthur P. J. Mol. Contemp. Sociol. 2002, 31, 727–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, A.; Sonnenfeld, D.A.; Spaargaren, G. (Eds.) The Ecological Modernisation Reader: Environmental Reform in Theory and Practice; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Norgaard, K.M. The sociological imagination in a time of climate change. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2018, 163, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brulle, R.J.; Carmichael, J.T.; Jenkins, J.C. Shifting public opinion on climate change: An empirical assessment of factors influencing concern over climate change in the U.S. 2002–2010. Clim. Chang. 2012, 114, 169–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. Climate Change and Society; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, E.A.; Rudel, T.K.; York, R.; Jorgenson, A.K.; Dietz, T. The Human (Anthropogenic) Driving Forces of Global Climate Change. In Climate Change and Society; Dunlap, R.E., Brulle, R.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 32–60. [Google Scholar]

- Buttel, F.H. Environment and Society: The Enduring Conflict. by Allan Schnaiberg, Kenneth Alan Gould. Contem. Sociol. 1994, 23, 509–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.S. (Ed.) Sustainability through the Lens of Environmental Sociology; MDPI (Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute): Wuhan, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Salleh, A. From Metabolic Rift to Metabolic Value: Reflections on Environmental Sociology and the Alternative Globalization Movement. Organ. Environ. 2010, 23, 205–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J.T.; Parks, B.C. A Climate of Injustice: Global Inequality, North-South Politics, and Climate Policy; The MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wackernagel, M.; William, R. Our Ecological Footprint; New Society: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Grundmann, R.; Stehr, N. Climate Change: What Role for Sociology? A Response to Constance Lever-Tracy. Curr. Sociol. 2010, 58, 897–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrow, C.; Pulver, S. Organizations and Markets. In Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives; Dunlap, R.E., Brulle, R.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 32–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt-Martinez, K.; Schor, J.B.; Abrahamse, W.; Alkon, A.H.; Axsen, J.; Brown, K.; Shwom, R.L.; Southerton, D.; Wilhite, H. Consumption and Climate Change. In Climate Change and Society; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 93–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kais, S.M.; Islam, M.S. Impacts of and Resilience to Climate Change at the Bottom of the Shrimp Commodity Chain in Bangladesh: A Preliminary Investigation. Aquaculture 2018, 493, 406–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, B. C., & Roberts, J. T. "Climate Change, Social Theory and Justice." Theory, Culture & Society, 2010, 27(2-3), 134-166. [CrossRef]

- Mennis, J.L.; Jordan, L. The Distribution of Environmental Equity: Exploring Spatial Nonstationarity in Multivariate Models of Air Toxic Releases. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2005, 95, 2, 249–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyiwul, L. Climate change adaptation and inequality in Africa: Case of water, energy and food insecurity. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yodmani, S. Disaster Risk Management and Vulnerability Reduction: Protecting the Poor. Asian Development Bank, 2001.

- Harlan, S.L.; Pellow, D.N.; Roberts, J.T.; Bell, S.E.; Holt, W.G.; Nagel, J. Climate Justice and Inequality. In Climate Change and Society; Dunlap, R.E., Brulle, R.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 127–163. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, J.T.; Toffolon-Weiss, M.M. Chronicles from the Environmental Justice Frontline; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pellow, D.N. The state and policy: Imperialism, exclusion and ecological violence as state policy. In Twenty Lessons in Environmental Sociology; Gould, K.A., Lewis, T.L., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Downey, L. Environmental Racial Inequality in Detroit. Soc. Forces 2006, 85, 771–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, N.; Wei, W.; Zhao, N. Social inequality among elderly individuals caused by climate change: Evidence from the migratory elderly of mainland China. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 272, 111079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K. Bamboo Beating Bandits: Conflict, Inequality, and Vulnerability in the Political Ecology of Climate Change Adaptation in Bangladesh. World Dev. 2018, 102, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, R. Climate Change and the Poorest Nations: Further Reflections on Global Inequality. University of Colorado Law Review, 2007, 78(4), 1559-1624.

- Roberts, J T. (2011). Multipolarity and the new world (dis)order: US hegemonic decline and the fragmentation of the global climate regime. Global Environmental Change, 2011, 21(2011), 776-784. [CrossRef]

- Roberts, T.J. Climate Change: Why the Old Approaches Aren’t Working. In Twenty Lessons in Environmental Sociology; Lewis, T.L., Gould, K.A., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 191–208. [Google Scholar]

- Mearns, R.; Norton, A. Social Dimensions of Climate Change: Equity and Vulnerability in a Warming World; The World Bank: Herndon, VA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Agyeman, J. Sustainable Communities and the Challenge of Environmental Justice; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.; Pei, Y.H.; Mangharam, S. Trans-Boundary Haze Pollution in Southeast Asia: Sustainability through Plural Environmental Governance. Sustainability 2016, 8, 499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgenson, A.K.; Dick, C.; Shandra, J.M. World Economy, World Society, and Environmental Harms in Less-Developed Countries. Sociol. Inq. 2011, 81, 53–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmin, J.; Tierney, K.; Chu, E.; Hunter, L.M.; Roberts, J.T.; Shi, L. Adaptation to Climate Change. In Climate Change and Society; Dunlap, R.E., Brulle, R.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 164–198. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt-Martinez, K.; Rudel, T.K.; Norgaard, K.M.; Broadbent, J. Mitigating Climate Change. In Climate Change and Society; Dunlap, R.E., Brulle, R.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 199–234. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, D.J. The Social Bases of Environmental Treaty Ratification, 1900?1990. Sociol. Inq. 1999, 69, 523–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniglia, B.S.; Brulle, R.J.; Szasz, A. Civil Society, Social Movements, and Climate Change. In Climate Change and Society; Dunlap, R.E., Brulle, R.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 235–268. [Google Scholar]

- Catton, W.R., Jr.; Dunlap, R.E. Environmental Sociology: A New Paradigm. Am. Sociol. 1978, 13, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Catton, W.R.; Dunlap, R.E. A New Ecological Paradigm for Post-Exuberant Sociology. Am. Behav. Sci. 1980, 24, 15–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R. E., & Van Liere, K. D. "The 'New Environmental Paradigm': A Proposed Measuring Instrument and Preliminary Results." Journal of Environmental Education, 1979, 9(1), 10-19. [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, R. E. "The NEP Scale: From Marginality to Worldwide Use." The Journal of Environmental Education, 2008, 40(1), 3-18. [CrossRef]

- Speth, J. G. The Bridge at the Edge of the World: Capitalism, the Environment, and Crossing from Crisis to Sustainability. Yale University Press, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, T. Prosperity Without Growth: Economics for a Finite Planet. Earthscan, 2009.

- Agyeman, J., Bullard, R. D., & Evans, B. Just Sustainabilities: Development in an Unequal World. MIT Press, 2003.

- Bullard, R. D. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. Westview Press, 2000.

- Dunlap, R.E.; McCright, A.M. The Denial Countermovement. In Climate Change and Society: Sociological Perspectives; Dunlap, R.E., Brulle, R.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 300–332. [Google Scholar]

- Mascarenhas, M. "Environmental Inequality and Environmental Justice." Sociology Compass, 2009, 3(2), 123-139.

- Schlosberg, D. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature. Oxford University Press, 2007.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).