Submitted:

27 September 2024

Posted:

30 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

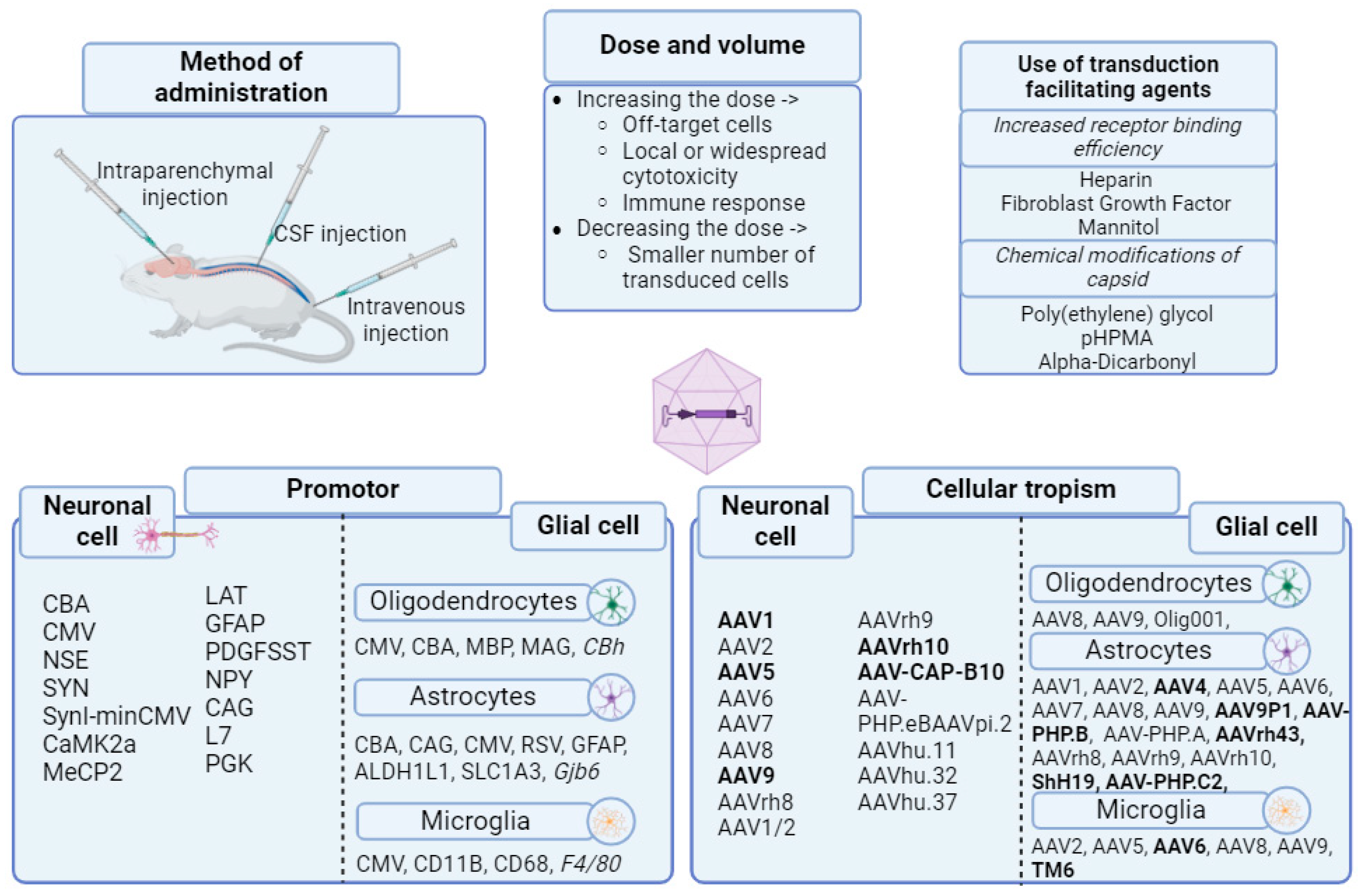

2.1. Tropism and Transduction Capacity of AAV Vectors

2.2. Pathogenesis of Epilepsy

2.3. Gain of Function Using an AAV Vector in the Treatment of Epileptic Disorders

2.3.1. Neuropeptides

2.3.2. Ion Channels, Receptors and Membrane Proteins

2.3.3. Neurotrophic and Transcription Factors

2.3.4. Other Transgenes for Delivery

2.4. Loss of Function Using AAV Vectors

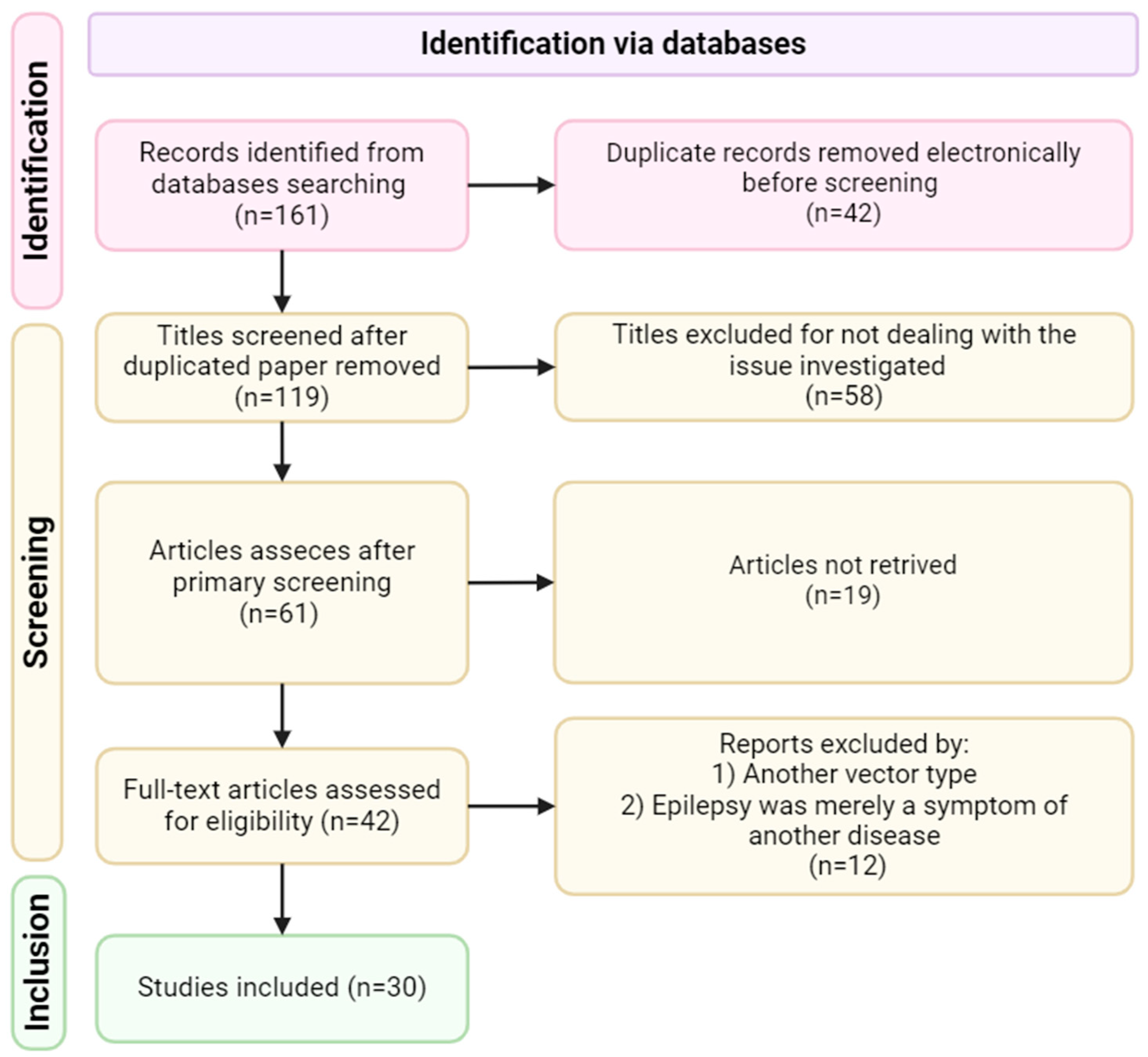

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Inclusion Criteria

3.2. Exclusion Criteria

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fisher, R.S.; et al. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia, 2014, 55, 475–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riney, K.; et al. International League Against Epilepsy classification and definition of epilepsy syndromes with onset at a variable age: position statement by the ILAE Task Force on Nosology and Definitions. Epilepsia, 2022, 63, 1443–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheffer, I.E.; et al. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia, 2017, 58, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.S.; et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia, 2017, 58, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, R.R.; et al. Neurochemical abnormalities in the hippocampus of male rats displaying audiogenic seizures, a genetic model of epilepsy. Neurosci Lett 2021, 761, 136123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Numis, A.L.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing with targeted analysis and epilepsy after acute symptomatic neonatal seizures. Pediatr Res, 2022, 91, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Møller, R.S., H.A. Dahl. and I. Helbig, The contribution of next generation sequencing to epilepsy genetics. Expert Rev Mol Diagn, 2015, 15, 1531–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.L.; et al. Clinical Utility of Exome Sequencing and Reinterpreting Genetic Test Results in Children and Adults With Epilepsy. Front Genet, 2020, 11, 591434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salzmann, A. and A. Malafosse, Genetics of temporal lobe epilepsy: a review. Epilepsy Res Treat, 2012, 2012: 863702.

- Cavalleri, G.L.; et al. Failure to replicate previously reported genetic associations with sporadic temporal lobe epilepsy: where to from here? Brain, 2005, 128 Pt 8, 1832-40.

- Pfisterer, U.; et al. Identification of epilepsy-associated neuronal subtypes and gene expression underlying epileptogenesis. Nat Commun, 2020, 11, 5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, G.; et al. Proteomic differences in the hippocampus and cortex of epilepsy brain tissue. Brain Commun, 2021, 3, fcab021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bando, S.Y.; et al. Correction: Complex Network Analysis of CA3 Transcriptome Reveals Pathogenic and Compensatory Pathways in Refractory Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. PLoS One. 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löscher, W.; et al. Drug Resistance in Epilepsy: Clinical Impact, Potential Mechanisms, and New Innovative Treatment Options. Pharmacol Rev, 2020, 72, 606–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, D. and W. Löscher. Drug resistance in epilepsy: putative neurobiologic and clinical mechanisms. Epilepsia, 2005, 46, 858–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meij, P.; et al. Advanced therapy medicinal products. Brief Pap, 2019, 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 320/12, D.o.t.G.C.o.A.J.C.N.I.A., “Bolar Exemption–Poland” Directive 2001/83/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 November 2001 on the Community Code Relating to Medicinal Products for Human Use, Art. 10 (6); Law on Industrial Property, Arts. 61 (1)(4), 63 (1). 2013, Springer.

- Shaimardanova, A.A.; et al., Gene and Cell Therapy for Epilepsy: A Mini Review. Front Mol Neurosci, 2022, 15: 868531.

- Detela, G.; Lodge, A. EU Regulatory Pathways for ATMPs: Standard, Accelerated and Adaptive Pathways to Marketing Authorisation. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev, 2019, 13, 205–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulak, J., J. Uchto. 50 years of gene therapy--a contribution of Wacław Szybalski to science and humanity. Gene, 2013, 525, 149–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lentz, T.B., S.J. Gray. Viral vectors for gene delivery to the central nervous system. Neurobiol Dis, 2012, 48, 179–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candolfi, M.; et al. Optimization of adenoviral vector-mediated transgene expression in the canine brain in vivo, and in canine glioma cells in vitro. Neuro Oncol, 2007, 9, 245–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpers, C. and S. Kochanek, Adenoviral vectors for gene transfer and therapy. J Gene Med, 2004, 6 Suppl 1: S164-71.

- Thomas, C.E.; et al. Acute direct adenoviral vector cytotoxicity and chronic, but not acute, inflammatory responses correlate with decreased vector-mediated transgene expression in the brain. Mol Ther, 2001, 3, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozier, J.N.; et al. Toxicity of a first-generation adenoviral vector in rhesus macaques. Hum Gene Ther, 2002, 13, 113–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markert, J.M.; et al. Phase Ib trial of mutant herpes simplex virus G207 inoculated pre-and post-tumor resection for recurrent GBM. Mol Ther, 2009, 17, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, Y., X.O. Breakefield. Improved HSV-1 amplicon packaging system using ICP27-deleted, oversized HSV-1 BAC DNA. Methods Mol Med, 2003, 76, 51–60. [Google Scholar]

- Goff, S.P. Retroviridae: The Retroviruses and Their Replication, in Fields Virology, D.M. Knipe and P.M. Howley, Editors. 2007, Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia. 2000–2069.

- Bokhoven, M.; et al. Insertional gene activation by lentiviral and gammaretroviral vectors. J Virol, 2009, 83, 283–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hacein-Bey-Abina, S.; et al. LMO2-associated clonal T cell proliferation in two patients after gene therapy for SCID-X1. Science, 2003, 302, 415–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.E., A. Ehrhardt. Progress and problems with the use of viral vectors for gene therapy. Nat Rev Genet, 2003, 4, 346–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimm, D. and M.A. Kay. From virus evolution to vector revolution: use of naturally occurring serotypes of adeno-associated virus (AAV) as novel vectors for human gene therapy. Curr Gene Ther, 2003, 3, 281–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, S.A.; et al. Gene therapy for neurological disorders: challenges and recent advancements. J Drug Target, 2020, 28, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullagulova, A.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Intravenous and Intrathecal Delivery of AAV9-Mediated ARSA in Minipigs. Int J Mol Sci, 2023, 24(11).

- Massaro, G.; et al. Gene Therapy for Lysosomal Storage Disorders: Ongoing Studies and Clinical Development. Biomolecules, 2021, 11(4).

- Janson, C.; et al. Clinical protocol. Gene therapy of Canavan disease: AAV-2 vector for neurosurgical delivery of aspartoacylase gene (ASPA) to the human brain. Hum Gene Ther, 2002, 13, 1391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corti, M.; et al. Adeno-associated virus-mediated gene therapy in a patient with Canavan disease using dual routes of administration and immune modulation. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev, 2023, 30: 303-314.

- Worgall, S.; et al. Treatment of late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis by CNS administration of a serotype 2 adeno-associated virus expressing CLN2 cDNA. Hum Gene Ther, 2008, 19, 463–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardieu, M.; et al. Intracerebral administration of adeno-associated viral vector serotype rh.10 carrying human SGSH and SUMF1 cDNAs in children with mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA disease: results of a phase I/II trial. Hum Gene Ther, 2014, 25, 506–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hocquemiller, M.; et al. AAVrh10 Vector Corrects Disease Pathology in MPS IIIA Mice and Achieves Widespread Distribution of SGSH in Large Animal Brains. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev, 2020, 17: 174-187.

- Mingozzi, F. and K.A. High. Therapeutic in vivo gene transfer for genetic disease using AAV: progress and challenges. Nat Rev Genet, 2011, 12, 341–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kido, J., K. Sugawara. Gene therapy for lysosomal storage diseases: Current clinical trial prospects. Front Genet, 2023, 14, 1064924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z., A. Asokan. Adeno-associated virus serotypes: vector toolkit for human gene therapy. Mol Ther, 2006, 14, 316–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengel, J.; Carette, J.E. Structural and cellular biology of adeno-associated virus attachment and entry. Adv Virus Res, 2020, 106, 39–84. [Google Scholar]

- Naso, M.F.; et al. Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) as a Vector for Gene Therapy. BioDrugs, 2017, 31, 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samulski, R.J., L.S. Chang. Helper-free stocks of recombinant adeno-associated viruses: normal integration does not require viral gene expressio. J Virol, 1989, 63, 3822–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samulski, R.J.; et al. Rescue of adeno-associated virus from recombinant plasmids: gene correction within the terminal repeats of AAV. Cell, 1983, 33, 135–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyöstiö, S.R.; et al. Analysis of adeno-associated virus (AAV) wild-type and mutant Rep proteins for their abilities to negatively regulate AAV p5 and p19 mRNA levels. J Virol, 1994, 68, 2947–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henckaerts, E. and R.M. Linden. Adeno-associated virus: a key to the human genome? Future Virol, 2010, 5, 555–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; et al. Parvovirus RNA processing strategies. 2006: Hodder Arnold, London, UK.

- James, J.A.; et al. Crystal structure of the SF3 helicase from adeno-associated virus type 2. Structure, 2003, 11, 1025–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickman, A.B.; et al. The nuclease domain of adeno-associated virus rep coordinates replication initiation using two distinct DNA recognition interfaces. Mol Cell, 2004, 13, 403–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surosky, R.T.; et al. Adeno-associated virus Rep proteins target DNA sequences to a unique locus in the human genome. J Virol, 1997, 71, 7951–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon-Robarts, M.; et al. Residues within the B' motif are critical for DNA binding by the superfamily 3 helicase Rep40 of adeno-associated virus type 2. J Biol Chem, 2004, 279, 50472–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, M.S. and M. Agbandje-McKenna, Atomic structure of viral particles. Parvoviruses, 2006: 107-23.

- Sonntag, F.; et al. The assembly-activating protein promotes capsid assembly of different adeno-associated virus serotypes. J Virol, 2011, 85, 12686–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Backer, M.W.; et al. Recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors. Methods Mol Biol, 2011, 789, 357–76. [Google Scholar]

- Issa, S.S.; et al. Various AAV Serotypes and Their Applications in Gene Therapy: An Overview. Cells, 2023, 12(5).

- Zincarelli, C.; et al. Analysis of AAV serotypes 1-9 mediated gene expression and tropism in mice after systemic injection. Mol Ther, 2008, 16, 1073–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cearley, C.N. and J.H. Wolfe. Transduction characteristics of adeno-associated virus vectors expressing cap serotypes 7, 8, 9, and Rh10 in the mouse brain. Mol Ther, 2006, 13, 528–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G., L.H. Vandenberghe. New recombinant serotypes of AAV vectors. Curr Gene Ther, 2005, 5, 285–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harbison, C.E., J.A. Chiorini. The parvovirus capsid odyssey: from the cell surface to the nucleus. Trends Microbiol, 2008, 16, 208–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; et al. Recombinant AAV viral vectors pseudotyped with viral capsids from serotypes 1, 2, and 5 display differential efficiency and cell tropism after delivery to different regions of the central nervous system. Mol Ther, 2004, 10, 302–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taymans, J.M.; et al. Comparative analysis of adeno-associated viral vector serotypes 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8 in mouse brain. Hum Gene Ther, 2007, 18, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, K.; et al. Robust systemic transduction with AAV9 vectors in mice: efficient global cardiac gene transfer superior to that of AAV8. Mol Ther, 2006, 14, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabner, J.; et al. Adeno-associated virus type 5 (AAV5) but not AAV2 binds to the apical surfaces of airway epithelia and facilitates gene transfer. J Virol, 2000, 74, 3852–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A. In vivo tissue-tropism of adeno-associated viral vectors. Curr Opin Virol, 2016, 21, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; et al. Gene transfer and expression in oligodendrocytes under the control of myelin basic protein transcriptional control region mediated by adeno-associated virus. Gene Ther, 1998, 5, 50–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; et al. Quantitative comparison of expression with adeno-associated virus (AAV-2) brain-specific gene cassettes. Gene Ther, 2001, 8, 1323–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.J.; et al. Optimizing promoters for recombinant adeno-associated virus-mediated gene expression in the peripheral and central nervous system using self-complementary vectors. Hum Gene Ther, 2011, 22, 1143–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, S.K., R.J. Samulski. AAV Capsid-Promoter Interactions Determine CNS Cell-Selective Gene Expression In Vivo. Mol Ther, 2020, 28, 1373–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.L.; et al. Better Targeting, Better Efficiency for Wide-Scale Neuronal Transduction with the Synapsin Promoter and AAV-PHP.B. Front Mol Neurosci, 2016, 9: 116.

- Verdera, H.C., K. Kuranda. AAV Vector Immunogenicity in Humans: A Long Journey to Successful Gene Transfer. Mol Ther, 2020, 28, 723–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, H.K.E., M. Isalan, and M. Mielcarek, Gene Therapy Advances: A Meta-Analysis of AAV Usage in Clinical Settings. Front Med (Lausanne), 2021, 8: 809118.

- Dhungel, B.P.; et al. Understanding AAV vector immunogenicity: from particle to patient. Theranostics, 2024, 14, 1260–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salganik, M., M. L. Hirsch, and R.J. Samulski, Adeno-associated Virus as a Mammalian DNA Vector. Microbiol Spectr, 2015, 3(4).

- Arjomandnejad, M.; et al. Immunogenicity of Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) Vectors for Gene Transfer. BioDrugs, 2023, 37, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; et al. Subthalamic GAD gene therapy in a Parkinson's disease rat model. Science, 2002, 298, 425–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- andel, R.J. and C. Burger. Clinical trials in neurological disorders using AAV vectors: promises and challenges. Curr Opin Mol Ther, 2004, 6, 482–90. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, G., K.K. Wong. Efficient gene transfer into nondividing cells by adeno-associated virus-based vectors. J Virol, 1994, 68, 5656–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, B.; et al. Efficient transduction of human neurons with an adeno-associated virus vector. Gene Ther, 1996, 3, 254–61. [Google Scholar]

- Jooss, K.; et al. Transduction of dendritic cells by DNA viral vectors directs the immune response to transgene products in muscle fibers. J Virol, 1998, 72, 4212–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplitt, M.G.; et al. Long-term gene expression and phenotypic correction using adeno-associated virus vectors in the mammalian brain. Nat Genet, 1994, 8, 148–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, R.R.; et al. Gene transfer into the mouse retina mediated by an adeno-associated viral vector. Hum Mol Genet, 1996, 5, 591–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.S., R.J. Samulski. Selective and rapid uptake of adeno-associated virus type 2 in brain. Hum Gene Ther, 1998, 9, 1181–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vite, C.H.; et al. Adeno-associated virus vector-mediated transduction in the cat brain. Gene Ther, 2003, 10, 1874–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- During, M.J.; et al. In vivo expression of therapeutic human genes for dopamine production in the caudates of MPTP-treated monkeys using an AAV vector. Gene Ther, 1998, 5, 820–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankiewicz, K.S.; et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of AAV vector in parkinsonian monkeys; in vivo detection of gene expression and restoration of dopaminergic function using pro-drug approach. Exp Neurol, 2000, 164, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freese, A.; et al. Direct gene transfer into human epileptogenic hippocampal tissue with an adeno-associated virus vector: implications for a gene therapy approach to epilepsy. Epilepsia, 1997, 38, 759–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastakov, M.Y.; et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus serotypes 2- and 5-mediated gene transfer in the mammalian brain: quantitative analysis of heparin co-infusion. Mol Ther, 2002, 5, 371–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, J.B.; et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of AAV-2 combined with heparin increases TK gene transfer in the rat brain. Neuroreport, 2001, 12, 1961–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naidoo, J.; et al. Extensive Transduction and Enhanced Spread of a Modified AAV2 Capsid in the Non-human Primate CNS. Mol Ther, 2018, 26, 2418–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoganson, D.K.; et al. Uptake of adenoviral vectors via fibroblast growth factor receptors involves intracellular pathways that differ from the targeting ligand. Mol Ther, 2001, 3, 105–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastakov, M.Y.; et al. Combined injection of rAAV with mannitol enhances gene expression in the rat brain. Mol Ther, 2001, 3, 225–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; et al. Self-complementary adeno-associated virus serotype 2 vector: global distribution and broad dispersion of AAV-mediated transgene expression in mouse brain. Mol Ther, 2003, 8, 911–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajiri, N.; et al. Breaking the Blood-Brain Barrier With Mannitol to Aid Stem Cell Therapeutics in the Chronic Stroke Brain. Cell Transplant, 2016, 25, 1453–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, C.; et al. Systemic mannitol-induced hyperosmolality amplifies rAAV2-mediated striatal transduction to a greater extent than local co-infusion. Mol Ther, 2005, 11, 327–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foley, C.P.; et al. Intra-arterial delivery of AAV vectors to the mouse brain after mannitol mediated blood brain barrier disruption. J Control Release, 2014, 196: 71-78.

- Chirmule, N.; et al. Immune responses to adenovirus and adeno-associated virus in humans. Gene Ther, 1999, 6, 1574–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskalenko, M.; et al. Epitope mapping of human anti-adeno-associated virus type 2 neutralizing antibodies: implications for gene therapy and virus structure. J Virol, 2000, 74, 1761–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peden, C.S.; et al. Circulating anti-wild-type adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) antibodies inhibit recombinant AAV2 (rAAV2)-mediated, but not rAAV5-mediated, gene transfer in the brain. J Virol, 2004, 78, 6344–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanftner, L.M.; et al. Striatal delivery of rAAV-hAADC to rats with preexisting immunity to AAV. Mol Ther, 2004, 9, 403–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, B.L.; et al. Recombinant adeno-associated virus type 2, 4, and 5 vectors: transduction of variant cell types and regions in the mammalian central nervous system. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2000, 97, 3428–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alisky, J.M.; et al. Transduction of murine cerebellar neurons with recombinant FIV and AAV5 vectors. Neuroreport, 2000, 11, 2669–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passini, M.A.; et al. Intraventricular brain injection of adeno-associated virus type 1 (AAV1) in neonatal mice results in complementary patterns of neuronal transduction to AAV2 and total long-term correction of storage lesions in the brains of beta-glucuronidase-deficient mice. J Virol, 2003, 77, 7034–40. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, G.P.; et al. Novel adeno-associated viruses from rhesus monkeys as vectors for human gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2002, 99, 11854–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.; et al. Total correction of hemophilia A mice with canine FVIII using an AAV 8 serotype. Blood, 2004, 103, 1253–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, H.; et al. Unrestricted hepatocyte transduction with adeno-associated virus serotype 8 vectors in mice. J Virol, 2005, 79, 214–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; et al. Adeno-associated virus serotype 8 efficiently delivers genes to muscle and heart. Nat Biotechnol, 2005, 23, 321–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, T.C.; et al. Enhanced gene transfer efficiency in the murine striatum and an orthotopic glioblastoma tumor model, using AAV-7- and AAV-8-pseudotyped vectors. Hum Gene Ther, 2006, 17, 807–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, S.J.; et al. Preclinical differences of intravascular AAV9 delivery to neurons and glia: a comparative study of adult mice and nonhuman primates. Mol Ther, 2011, 19, 1058–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, D.; et al., Deep Parallel Characterization of AAV Tropism and AAV-Mediated Transcriptional Changes via Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Front Immunol, 2021, 12: 730825.

- Devinsky, O.; et al. Glia and epilepsy: excitability and inflammation. Trends Neurosci, 2013, 36, 174–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O'Carroll, S.J., W.H. Cook, and D. Young, AAV Targeting of Glial Cell Types in the Central and Peripheral Nervous System and Relevance to Human Gene Therapy. Front Mol Neurosci, 2020, 13: 618020.

- Chandran, J.; et al. Assessment of AAV9 distribution and transduction in rats after administration through Intrastriatal, Intracisterna magna and Lumbar Intrathecal routes. Gene Ther, 2023, 30(1-2): 132-141.

- Foust, K.D.; et al. Intravascular AAV9 preferentially targets neonatal neurons and adult astrocytes. Nat Biotechnol, 2009, 27, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraiva, J., R. J. Nobre, and L. Pereira de Almeida, Gene therapy for the CNS using AAVs: The impact of systemic delivery by AAV9. J Control Release, 2016, 241: 94-109.

- Deverman, B.E.; et al. Cre-dependent selection yields AAV variants for widespread gene transfer to the adult brain. Nat Biotechnol, 2016, 34, 204–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, G.; et al. AAV-PHP.B-Mediated Global-Scale Expression in the Mouse Nervous System Enables GBA1 Gene Therapy for Wide Protection from Synucleinopathy. Mol Ther, 2017, 25, 2727–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S., S. Huang. Acceleration of rare disease therapeutic development: a case study of AGIL-AADC. Drug Discov Today, 2019, 24, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeler, A.M. and T.R. Flotte. Recombinant Adeno-Associated Virus Gene Therapy in Light of Luxturna (and Zolgensma and Glybera): Where Are We, and How Did We Get Here? Annu Rev Virol, 2019, 6, 601–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, H.A. Onasemnogene Abeparvovec: A Review in Spinal Muscular Atrophy. CNS Drugs, 2022, 36, 995–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, Y.A. Etranacogene Dezaparvovec: First Approval. Drugs, 2023, 83, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shariff, S.; et al. Advances in understanding the pathogenesis of epilepsy: Unraveling the molecular mechanisms: A cross-sectional study. Health Sci Rep, 2024, 7, e1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staley, K. Molecular mechanisms of epilepsy. Nat Neurosci, 2015, 18, 367–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.H. and A.S. Hazell. Excitotoxic mechanisms and the role of astrocytic glutamate transporters in traumatic brain injury. Neurochem Int, 2006, 48, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLorenzo, R.J., D.A. Sun. Erratum to "Cellular mechanisms underlying acquired epilepsy: the calcium hypothesis of the induction and maintenance of epilepsy." [Pharmacol. Ther. 105(3) (2005) 229-266]. Pharmacol Ther, 2006, 111, 288–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treiman, D.M. GABAergic mechanisms in epilepsy. Epilepsia, 2001, 42 Suppl 3: 8-12.

- Aroniadou-Anderjaska, V.; et al. Pathology and pathophysiology of the amygdala in epileptogenesis and epilepsy. Epilepsy Res, 2008, 78(2-3): 102-16.

- Hirose, S.; et al. Are some idiopathic epilepsies disorders of ion channels?: A working hypothesis. Epilepsy Res, 2000, 41, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, T.D. Ion channels and epilepsy. QJM, 2006, 99, 201–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkovic, S.F.; et al. Human epilepsies: interaction of genetic and acquired factors. Trends Neurosci, 2006, 29, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boleti, A.P.A.; et al. Pathophysiology to Risk Factor and Therapeutics to Treatment Strategies on Epilepsy. Brain Sci, 2024, 14(1).

- Chugh, D.; et al. Alterations in Brain Inflammation, Synaptic Proteins, and Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis during Epileptogenesis in Mice Lacking Synapsin2. PLoS One, 2015, 10, e0132366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clynen, E.; et al. Neuropeptides as targets for the development of anticonvulsant drugs. Mol Neurobiol, 2014, 50, 626–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laing, B.T.; et al. AgRP/NPY Neuron Excitability Is Modulated by Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor 1 During Fasting. Front Cell Neurosci, 2018, 12: 276.

- Colmers, W.F. and D. Bleakman, Effects of neuropeptide Y on the electrical properties of neurons. Trends Neurosci, 1994, 17, 373–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Greber, S., C. Schwarzer. Neuropeptide Y inhibits potassium-stimulated glutamate release through Y2 receptors in rat hippocampal slices in vitro. Br J Pharmacol, 1994, 113, 737–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richichi, C.; et al. Anticonvulsant and antiepileptogenic effects mediated by adeno-associated virus vector neuropeptide Y expression in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci, 2004, 24, 3051–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noè, F.; et al. Neuropeptide Y gene therapy decreases chronic spontaneous seizures in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain, 2008, 131(Pt 6): 1506-15.

- Noe, F.; et al. Anticonvulsant effects and behavioural outcomes of rAAV serotype 1 vector-mediated neuropeptide Y overexpression in rat hippocampus. Gene Ther, 2010, 17, 643–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, Y.; et al. Potent and selective tools to investigate neuropeptide Y receptors in the central and peripheral nervous systems: BIB03304 (Y1) and CGP71683A (Y5). Can J Physiol Pharmacol, 2000, 78, 116–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.J.; et al. Differential actions of NPY on seizure modulation via Y1 and Y2 receptors: evidence from receptor knockout mice. Epilepsia, 2006, 47, 773–80. [Google Scholar]

- El Bahh, B.; et al. The anti-epileptic actions of neuropeptide Y in the hippocampus are mediated by Y and not Y receptors. Eur J Neurosci, 2005, 22, 1417–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furtinger, S.; et al. Plasticity of Y1 and Y2 receptors and neuropeptide Y fibers in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci, 2001, 21, 5804–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, C., N. Kofler. Up-regulation of neuropeptide Y-Y2 receptors in an animal model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Mol Pharmacol, 1998, 53, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzani, A.; et al. Plastic changes in neuropeptide Y receptor subtypes in experimental models of limbic seizures. Epilepsia, 2000, 41 Suppl 6: S115-21.

- Foti, S.; et al. Adeno-associated virus-mediated expression and constitutive secretion of NPY or NPY13-36 suppresses seizure activity in vivo. Gene Ther, 2007, 14, 1534–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woldbye, D.P.; et al. Adeno-associated viral vector-induced overexpression of neuropeptide Y Y2 receptors in the hippocampus suppresses seizures. Brain, 2010, 133, 2778–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledri, L.N.; et al. Translational approach for gene therapy in epilepsy: Model system and unilateral overexpression of neuropeptide Y and Y2 receptors. Neurobiol Dis, 2016, 86: 52-61.

- Powell, K.L.; et al. Gene therapy mediated seizure suppression in Genetic Generalised Epilepsy: Neuropeptide Y overexpression in a rat model. Neurobiol Dis, 2018, 113: 23-32.

- Melin, E.; et al. Disease Modification by Combinatorial Single Vector Gene Therapy: A Preclinical Translational Study in Epilepsy. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev, 2019, 15: 179-193.

- Wickham, J.; et al. Inhibition of epileptiform activity by neuropeptide Y in brain tissue from drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy patients. Sci Rep, 2019, 9, 19393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, E.; et al. Combinatorial gene therapy for epilepsy: Gene sequence positioning and AAV serotype influence expression and inhibitory effect on seizures. Gene Ther, 2023, 30(7-8): 649-658.

- Qian, J., W.F. Colmers. Inhibition of synaptic transmission by neuropeptide Y in rat hippocampal area CA1: modulation of presynaptic Ca2+ entry. J Neurosci, 1997, 17, 8169–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webling, K.; et al. Ala(5)-galanin (2-11) is a GAL(2)R specific galanin analogue. Neuropeptides, 2016, 60: 75-82.

- Konopka, L.M., T. W. McKeon, and R.L. Parsons, Galanin-induced hyperpolarization and decreased membrane excitability of neurones in mudpuppy cardiac ganglia. J Physiol, 1989, 410: 107-22.

- Papas, S. and C.W. Bourque. Galanin inhibits continuous and phasic firing in rat hypothalamic magnocellular neurosecretory cells. J Neurosci, 1997, 17, 6048–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishibori, M.; et al. Galanin inhibits noradrenaline-induced accumulation of cyclic AMP in the rat cerebral cortex. J Neurochem, 1988, 51, 1953–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, L.A. and R.L. Parsons. Neuropeptide galanin inhibits omega-conotoxin GVIA-sensitive calcium channels in parasympathetic neurons. J Neurophysiol, 1995, 73, 1374–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordstrom, O.; et al. Evidence for an inhibitory effect of the peptide galanin on dopamine release from the rat median eminence. Neurosci Lett, 1987, 73, 21–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogren, S.O.; et al. Differential effects of the putative galanin receptor antagonists M15 and M35 on striatal acetylcholine release. Eur J Pharmacol, 1993, 242, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zini, S.; et al. Galanin reduces release of endogenous excitatory amino acids in the rat hippocampus. Eur J Pharmacol, 1993, 245, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellmann, R.; et al. Enhanced rate of expression and biosynthesis of neuropeptide Y after kainic acid-induced seizures. J Neurochem, 1991, 56, 525–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loacker, S.; et al. Endogenous dynorphin in epileptogenesis and epilepsy: anticonvulsant net effect via kappa opioid receptors. Brain, 2007, 130(Pt 4): 1017-28.

- Stogmann, E.; et al. A functional polymorphism in the prodynorphin gene promotor is associated with temporal lobe epilepsy. Ann Neurol, 2002, 51, 260–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Lanerolle, N.C.; et al. Dynorphin and the kappa 1 ligand [3H]U69,593 binding in the human epileptogenic hippocampus. Epilepsy Res, 1997, 28, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartfai, T.; et al. M-15: high-affinity chimeric peptide that blocks the neuronal actions of galanin in the hippocampus, locus coeruleus, and spinal cord. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 1991, 88, 10961–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haberman, R.P., R.J. Samulski. Attenuation of seizures and neuronal death by adeno-associated virus vector galanin expression and secretion. Nat Med, 2003, 9, 1076–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.J.; et al. Recombinant AAV-mediated expression of galanin in rat hippocampus suppresses seizure development. Eur J Neurosci, 2003, 18, 2087–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCown, T.J. Adeno-associated virus-mediated expression and constitutive secretion of galanin suppresses limbic seizure activity in vivo. Mol Ther, 2006, 14, 63–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostinho, A.S.; et al. Dynorphin-based "release on demand" gene therapy for drug-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy. EMBO Mol Med, 2019, 11, e9963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo, J.A.; et al. Ion channels and epilepsy. Curr Pharm Des, 2005, 11, 1975–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, H.F. Glutamate, GABA and epilepsy. Prog Neurobiol, 1995, 47, 477–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- During, M.J.; et al. An oral vaccine against NMDAR1 with efficacy in experimental stroke and epilepsy. Science, 2000, 287, 1453–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.W.; et al. Incidence of Dravet Syndrome in a US Population. Pediatrics, 2015, 136, e1310–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogiwara, I.; et al. Nav1.1 localizes to axons of parvalbumin-positive inhibitory interneurons: a circuit basis for epileptic seizures in mice carrying an Scn1a gene mutation. J Neurosci, 2007, 27, 5903–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.H.; et al. Reduced sodium current in GABAergic interneurons in a mouse model of severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy. Nat Neurosci, 2006, 9, 1142–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; et al. Autistic-like behaviour in Scn1a+/- mice and rescue by enhanced GABA-mediated neurotransmission. Nature, 2012, 489, 385–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, C.; et al. Impaired excitability of somatostatin- and parvalbumin-expressing cortical interneurons in a mouse model of Dravet syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2014, 111, E3139–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanenhaus, A.; et al. Cell-Selective Adeno-Associated Virus-Mediated SCN1A Gene Regulation Therapy Rescues Mortality and Seizure Phenotypes in a Dravet Syndrome Mouse Model and Is Well Tolerated in Nonhuman Primates. Hum Gene Ther, 2022, 33(11-12): 579-597.

- van der Stelt, M.; et al. Acute neuronal injury, excitotoxicity, and the endocannabinoid system. Mol Neurobiol, 2002, 26(2-3): 317-46.

- Monory, K.; et al. The endocannabinoid system controls key epileptogenic circuits in the hippocampus. Neuron, 2006, 51, 455–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludanyi, A.; et al. Downregulation of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor and related molecular elements of the endocannabinoid system in epileptic human hippocampus. J Neurosci, 2008, 28, 2976–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, E.S. and L.V. Vinogradova. Potassium channels as prominent targets and tools for the treatment of epilepsy. Expert Opin Ther Targets, 2021, 25, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wykes, R.C.; et al. Optogenetic and potassium channel gene therapy in a rodent model of focal neocortical epilepsy. Sci Transl Med, 2012, 4, 161ra152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snowball, A.; et al. Epilepsy Gene Therapy Using an Engineered Potassium Channel. J Neurosci, 2019, 39, 3159–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magloire, V.; et al. KCC2 overexpression prevents the paradoxical seizure-promoting action of somatic inhibition. Nat Commun, 2019, 10, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; et al. On-demand cell-autonomous gene therapy for brain circuit disorders. Science, 2022, 378, 523–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohling, R. and J. Wolfart, Potassium Channels in Epilepsy. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2016, 6(5).

- Masnada, S.; et al. Clinical spectrum and genotype-phenotype associations of KCNA2-related encephalopathies. Brain, 2017, 140, 2337–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muona, M.; et al. A recurrent de novo mutation in KCNC1 causes progressive myoclonus epilepsy. Nat Genet, 2015, 47, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbett, M.A.; et al. Dominant KCNA2 mutation causes episodic ataxia and pharmacoresponsive epilepsy. Neurology, 2016, 87, 1975–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, C.; et al. Mutations in the voltage-gated potassium channel gene KCNH1 cause Temple-Baraitser syndrome and epilepsy. Nat Genet, 2015, 47, 73–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kole, M.H., J.J. Letzkus. Axon initial segment Kv1 channels control axonal action potential waveform and synaptic efficacy. Neuron, 2007, 55, 633–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foust, A.J.; et al. Somatic membrane potential and Kv1 channels control spike repolarization in cortical axon collaterals and presynaptic boutons. J Neurosci, 2011, 31, 15490–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; et al. Modulation of intracortical synaptic potentials by presynaptic somatic membrane potential. Nature, 2006, 441, 761–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshchin, M.V.; et al. A BK channel-mediated feedback pathway links single-synapse activity with action potential sharpening in repetitive firing. Sci Adv, 2018, 4, eaat1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks-Kayal, A.R.; et al. Human neuronal gamma-aminobutyric acid(A) receptors: coordinated subunit mRNA expression and functional correlates in individual dentate granule cells. J Neurosci, 1999, 19, 8312–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks-Kayal, A.R.; et al. Selective changes in single cell GABA(A) receptor subunit expression and function in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Med, 1998, 4, 1166–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; et al. Effects of status epilepticus on hippocampal GABAA receptors are age-dependent. Neuroscience, 2004, 125, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raol, Y.H.; et al. Enhancing GABA(A) receptor alpha 1 subunit levels in hippocampal dentate gyrus inhibits epilepsy development in an animal model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci, 2006, 26, 11342–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, E.S.; et al. Overexpression of KCNN4 channels in principal neurons produces an anti-seizure effect without reducing their coding ability. Gene Ther, 2024, 31(3-4): 144-153.

- Guggenhuber, S.; et al. AAV vector-mediated overexpression of CB1 cannabinoid receptor in pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus protects against seizure-induced excitoxicity. PLoS One, 2010, 5, e15707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguro, K.; et al. Global brain delivery of neuroligin 2 gene ameliorates seizures in a mouse model of epilepsy. J Gene Med, 2022, 24, e3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deister, C. and C.E. Schmidt. Optimizing neurotrophic factor combinations for neurite outgrowth. J Neural Eng, 2006, 3, 172–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanter-Schlifke, I.; et al. Seizure suppression by GDNF gene therapy in animal models of epilepsy. Mol Ther, 2007, 15, 1106–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humpel, C.; et al. Neurons of the hippocampal formation express glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor messenger RNA in response to kainate-induced excitation. Neuroscience, 1994, 59, 791–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikuni, N.; et al. Time course of transient expression of GDNF protein in rat granule cells of the bilateral dentate gyri after unilateral intrahippocampal kainic acid injection. Neurosci Lett, 1999, 262, 215–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt-Kastner, R.; et al. Glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) mRNA upregulation in striatum and cortical areas after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in rats. Brain Res Mol Brain Res, 1994, 26(1-2): 325-30.

- Martin, D.; et al. Potent inhibitory effects of glial derived neurotrophic factor against kainic acid mediated seizures in the rat. Brain Res, 1995, 683, 172–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; et al. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor modulates kindling and activation-induced sprouting in hippocampus of adult rats. Exp Neurol, 2002, 178, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, Y.M.; et al. Neuroprotection of adenoviral-vector-mediated GDNF expression against kainic-acid-induced excitotoxicity in the rat hippocampus. Exp Neurol, 2006, 200, 407–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.M. and J.A. Johnson. An important role of Nrf2-ARE pathway in the cellular defense mechanism. J Biochem Mol Biol, 2004, 37, 139–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T., P. J. Sherratt, and C.B. Pickett, Regulatory mechanisms controlling gene expression mediated by the antioxidant response element. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 2003, 43: 233-60.

- Hybertson, B.M.; et al. Oxidative stress in health and disease: the therapeutic potential of Nrf2 activation. Mol Aspects Med, 2011, 32(4-6): 234-46.

- Mazzuferi, M.; et al. Nrf2 defense pathway: Experimental evidence for its protective role in epilepsy. Ann Neurol, 2013, 74, 560–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klugmann, M.; et al. AAV-mediated hippocampal expression of short and long Homer 1 proteins differentially affect cognition and seizure activity in adult rats. Mol Cell Neurosci, 2005, 28, 347–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerangue, N. and M.Kavanaugh. Flux coupling in a neuronal glutamate transporter. Nature, 1996, 383, 634–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, J.D.; et al. Knockout of glutamate transporters reveals a major role for astroglial transport in excitotoxicity and clearance of glutamate. Neuron, 1996, 16, 675–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathern, G.W.; et al. Hippocampal GABA and glutamate transporter immunoreactivity in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology, 1999, 52, 453–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proper, E.A.; et al. Distribution of glutamate transporters in the hippocampus of patients with pharmaco-resistant temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain, 2002, 125(Pt 1): 32-43.

- van der Hel, W.S.; et al. Reduced glutamine synthetase in hippocampal areas with neuron loss in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology, 2005, 64, 326–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- During, M.J. and D.D. Spencer. Extracellular hippocampal glutamate and spontaneous seizure in the conscious human brain. Lancet, 1993, 341, 1607–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eid, T.; et al. Loss of glutamine synthetase in the human epileptogenic hippocampus: possible mechanism for raised extracellular glutamate in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Lancet, 2004, 363, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessler, S.; et al. Expression of the glutamate transporters in human temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience, 1999, 88, 1083–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, S.H., I. Kuo. and D. Eisenberg, Discovery of the ammonium substrate site on glutamine synthetase, a third cation binding site. Protein Sci, 1995, 4, 2358–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suarez, I., G. Bodega, and B. Fernandez, Glutamine synthetase in brain: effect of ammonia. Neurochem Int, 2002, 41(2-3): 123-42.

- Venkatesh, K.; et al. In vitro differentiation of cultured human CD34+ cells into astrocytes. Neurol India, 2013, 61, 383–8. [Google Scholar]

- Young, D.; et al. Adenosine kinase, glutamine synthetase and EAAT2 as gene therapy targets for temporal lobe epilepsy. Gene Ther, 2014, 21, 1029–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.I.; et al. Prolonged reduction of high blood pressure with an in vivo, nonpathogenic, adeno-associated viral vector delivery of AT1-R mRNA antisense. Hypertension, 1997, 29(1 Pt 2): 374-80.

- Evers, M.M., L. J. Toonen, and W.M. van Roon-Mom, Antisense oligonucleotides in therapy for neurodegenerative disorders. Adv Drug Deliv Rev, 2015, 87: 90-103.

- Xiao, X.; et al. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vector antisense gene transfer in vivo decreases GABA(A) alpha1 containing receptors and increases inferior collicular seizure sensitivity. Brain Res, 1997, 756(1-2): 76-83.

- Haberman, R.; et al. Therapeutic liabilities of in vivo viral vector tropism: adeno-associated virus vectors, NMDAR1 antisense, and focal seizure sensitivity. Mol Ther, 2002, 6, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theofilas, P.; et al. Adenosine kinase as a target for therapeutic antisense strategies in epilepsy. Epilepsia, 2011, 52, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; et al. Tubulin β-III modulates seizure activity in epilepsy. J Pathol, 2017, 242, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.L.; et al. Long non-coding RNA H19 contributes to apoptosis of hippocampal neurons by inhibiting let-7b in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Cell Death Dis, 2018, 9, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, C.L.; et al. Whole-transcriptome screening reveals the regulatory targets and functions of long non-coding RNA H19 in epileptic rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2017, 489, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, J.C.; et al. Selective targeting of Scn8a prevents seizure development in a mouse model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Sci Rep, 2018, 8, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peret, A.; et al. Contribution of aberrant GluK2-containing kainate receptors to chronic seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. Cell Rep, 2014, 8, 347–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, C.; et al. GluK2 Is a Target for Gene Therapy in Drug-Resistant Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Ann Neurol, 2023, 94, 745–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Serotype | Delivery gene | Model | Antiepileptic effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV2; AAV1/2 | NPY | КА, rats | Reducing the number of seizures. Reducing the duration of seizure activity | [139] |

| AAV2 | КА, rats | Increase in the latent period of limbic convulsive activity | [148] | |

| AVV1/2 | Electrical stimulation, rats | Reducing the frequency of seizures. Decrease in the progression of seizures by 80% | [140] | |

| AAV1 | КА, rats | Reducing the number of seizures by 55%. Reducing the duration of ictal activity | [141] | |

| AAV1/2 | КА, rats | Preventing the progression of the frequency of seizures by 57.5 ± 19.3%. Reducing the duration of seizure activity | [150] | |

| AAV1/2 | GAERS GGE, rats | Reducing the duration of seizure activity, reducing the number of seizures | [151] | |

| AAV1 | КА, rats | Reducing the severity of seizures. Increase in the latent time. Decrease in the frequency and total time of seizure activity. SRS suppression | [152] | |

| AAV1, AAV2, AAV8 | КА, rats + resected human hippocampus | AAV1 reduces the time spent on motor seizures and increases the latency period to SE | [154] | |

| AAV2 | Y2 | Kindling, КА, rats | Reduction of the cumulative degree of seizures. Reducing the number of severe grade 4-5 seizures and increasing the amount of stimulation needed to achieve grade 3 or 4-5 seizures | [149] |

| AAV2 | GAL | КА, rats, HEK 293 cells | Decrease of in vivo sensitivity to focal seizures and prevention of hilar cell death caused by kainic acid | [169] |

| AAV2 | КА, rats, HEK 293 cells | Increase in the threshold of excitability. Reduction of neuronal death | [170] | |

| AAV2 | КА, Kindling, rats | Suppression of limbic seizures. Increase in the stimulation current required to induce limbic convulsive activity | [171] | |

| AAV1/2 | HOMER1 | Electrical stimulation, rats | Suppression of SSLSE | [218] |

| AAV2 | GABRA4 | Electrical stimulation, rats | Suppression of SSLSE | [202] |

| AAV2 | GDNF | Kindling, rats | Suppression of SSLSE. Increased survival after SE | [207] |

| AAV1/2 | CB1 | КА, mice | Reducing the severity of seizures. Protection from excitotoxicity and neuronal death | [204] |

| AAV2 | Nrf2 | Lithium-pilocarpine model, mice | Decrease in microglia activation. The ratio between astrocytes/neurons and activated microglia/neurons was significantly lower | [217] |

| AAV9 | EAAT2 | КА, rats | There were no differences in the total duration of seizures between the animals that were injected with the EAAT2, GS vector, and the control vector | [230] |

| GS | ||||

| AAV1 | Dyn | КА, electrical stimulation, rats, mice | Suppression of seizures. The disappearance of generalized seizures | [172] |

| AAV2 | NL2 | Models of polygenic epilepsy, mice | Significant decrease in the duration, strength and frequency of seizures was observed over a 14-week period | [205] |

| AAV9 | SCN1A | Scn1a+/-, mice, primates | Reducing the frequency, duration and severity of spontaneous seizures and reduces the sensitivity of HTS in Dravet mice | [181] |

| AAV2 | KCNN4 | 4-aminopyridine model, mice | Powerful suppression of pharmacologically induced seizures in vitro both at the level of single cells and at the level of the local field with a decrease in peaks during ictal discharges | [203] |

| Serotype | Gene for blocking | Model | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAV2 | GABA(A) | КА, Kindling, rats | Modulation of colliculi inferiores convultions | [233] |

| AAV2 | NMDAR1 | КА, rats | Significant decrease in sensitivity to focal seizures within 4 weeks. The design of the pTet promoter caused the opposite effect — a significant increase in sensitivity to seizures. It has been shown that in the brain, NMDA receptor excitation can cause GABA inhibition [21], therefore, removing NMDA receptor excitation from these inhibitory interneurons can create a state of hyperexcitability. | [234] |

| AAV8 | ADK | Transgenic mice with spontaneous epilepsy | Preventing of convulsive activity | [235] |

| AAV9 | lnRNA H19 | КА, rats | The CA3 neurons were preserved | [238] |

| AAV10 | Scn8a | КА, mice | Protection from spontaneous seizures. Reduction of gliosis | [238] |

| AAV9 | GluK2 | Pilocarpine, mice | Reduction of chronic convulsive activity | [241] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).