1. Introduction

The oral or nasal cavities are the first regions of contact with all external nonself-materials including pathogenic microorganisms and allergic compounds. Airborne viruses such as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and influenza enter from these upper respiratory tract mucosae. Therefore, these mucosae function as the first line of defense against these viruses. The mucosal protection generally operates through both mucosal and systemic immune responses, resulting in antibody-mediated and cytotoxic T cell reactions. Sublingual or intranasal vaccines elicit these immune responses, dispense with the need for medical staff, and allow needle-free administration. Vaccines are primarily categorized into two types: RNA/DNA vaccines and protein-based vaccines. During the COVID-19 pandemic, gene-based RNA or DNA vaccines were employed to combat the disease; however, these vaccines were associated with side effects, including fever, headache, nausea, and chills [

1]. Conversely, protein-based vaccinations exhibit fewer adverse effects and are employed in the prevention of hepatitis and several viral illnesses [

2]. Although the development of a protein vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 requires time, it is anticipated to become a cornerstone in the global protection against COVID-19 [

3,

4]. A protein-based vaccine requires an immunity-stimulating adjuvant, which is classified into two categories. The first, MF59 or AS03, is an oil-in-water nano-emulsion vaccine that stimulates Th1/Th2 cytokines [

5]. The second is double-stranded (ds) RNA (polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (Poly(I:C)), a ligand for Toll-like receptor (TLR) 3 that induces immunological and proinflammatory responses [

6]. MF59 and AS03 received approval as adjuvants for intramuscularly administered influenza vaccinations [

7]. Nevertheless, Poly(I:C) remains unapproved because of its adverse effects, including fever and the generation of proinflammatory cytokines.

The vaccination site is also a limiting factor in developing a protein-based vaccine. Protection against upper respiratory tract viruses, such as SARS-CoV-2 and influenza, can be provided using sublingual or intranasal vaccines. Sublingual vaccines, like nasal vaccines, elicit mucosal immune responses in the upper and lower respiratory tracts, stomach, small intestine, and reproductive tracts, as well as a systemic response [

8,

9]. Another advantage of the sublingual vaccination is that it is safer than intranasal vaccines, which can harm the brain, central nervous system, and lungs [

10,

11]. The sublingual vaccine is also administered needle-free, resulting in good patient compliance and the ability to self-administer without the assistance of medical personnel. However, administering vaccines sublingually has practical issues, such as a mucin barrier that prevents vaccine access into immune cells and a large volume of saliva that dilutes the vaccine.

We previously developed a sublingual vaccine formulation with Poly (I:C) adjuvant and SARS-CoV-2- receptor binding domain (RBD) [

12,

13] or influenza HA [

14] antigens using a non-human primate model, cynomolgus macaques. These sublingual Poly (I:C)-adjuvanted vaccines induced mucosal and systemic immunological responses, resulting in antigen-specific antibodies in the saliva, nasal washes, and blood. In these studies, we avoided mucin inhibition by pre-treating the sublingual surface with N-acetyl cysteine (NAC), a moderately reducing reagent that disintegrates the mucin layer [

12,

15,

16]. We also avoided saliva dilution by using an anesthetic, a combination of medetomidine and ketamine, to decrease saliva output during vaccination [

12]. DNA microarray analysis revealed that sublingual Poly (I:C)-adjuvanted vaccinations elicited immunological responses via a previously unknown mechanism that generates balanced activation and inhibition in a "Yin/Yang" concept [

2,

13]. The Poly (I:C)-adjuvanted vaccines administered via sublingual route appeared to be safe based on gene expression analyses of proinflammatory-related factors in peripheral blood white cells (PBWCs) in comparison with the AddaS03 adjuvant, which has the same composition as AS03 [

14], but its safety remains to be further evaluated.

This study aimed to evaluate the safety of sublingual Poly (I:C)-adjuvanted vaccinations. The evaluation was conducted through quantitative gene expression analyses (RT-qPCR) of inflammatory-related factors in several tissues/sites, including brain (olfactory bulb and pons), from both mice/rodents and macaque monkeys/non-human primates that were administered a Poly (I:C)-adjuvanted influenza HA vaccine via sublingual and intranasal routes. Intranasally administered Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccination significantly upregulated the expression of inflammatory-related genes in the olfactory bulb of mice, unlike the sublingually administered vaccine, which did not produce this effect in either mice or macaques. The adverse effect caused by the intranasally administered vaccination was also noted in the olfactory bulb of macaques, although the effects were less pronounced. The previously reported adverse effects of the Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccination resulted in particular events in the olfactory bulb of rodents. Consequently, the sublingual Poly (I:C)-adjuvanted vaccination appears to be safe in primates, including humans.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

NAC, bovine serum albumin, Na-Casein, and sodium azide (NaN3) were obtained from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Japan). Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Nissui, Japan), a quadrivalent FLUBIK HA Syringes™ vaccine (The Research Foundation for Microbial Diseases of Osaka University, Suita, Japan), and poly(I:C) HMW vaccine grade ((Poly(I:C); Invitrogen) were also used. RNAiso Plus, PrimeScript™ Reverse Transcriptase, 2680, Recombinant RNase Inhibitor, TB Green® Premix Ex Taq™ (Tli RNaseH Plus, Japan), RR420(Takara Bio, Japan), RNeasy MinElute Cleanup Kit (QIAGEN, USA), dNTP Mix and Oligo(dT)15 Primer (Promega, USA), Low Input Quick Amp Labeling Kit, and RNA6000 Nano Kit (Agilent Technologies, USA) were used in this study.

2.2. Animals

Thirty-two male mice (ICR; aged 8 to 9 weeks) and six male macaque monkeys (Macaca fascicularis and Macaca mulatta; aged 15 to 20 years) were used. In accordance with the 3R policy for animal use, the number of macaque monkeys was minimized. The monkeys tested negative for B virus, simian immunodeficiency virus, TB, Shigella spp., Salmonella spp., and helminthic parasites.

The animal examinations were performed in accordance with the regulations set forth by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Intelligence and Technology Lab, Inc. (ITL), adhering to the standards for the Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments. The Animal Care Committee of ITL sanctioned these examinations, designating them with the code AE2022022 and granting approval on 24 November 2022. The ITL Biosafety Committee has sanctioned additional studies.

2.3. Vaccination and Sampling

The preparation and administration of a vaccine made with Poly(I:C) adjuvant and influenza HA antigen were performed as previously described [

14]. The following procedures were used to administer vaccines and collect samples from mice and macaques (

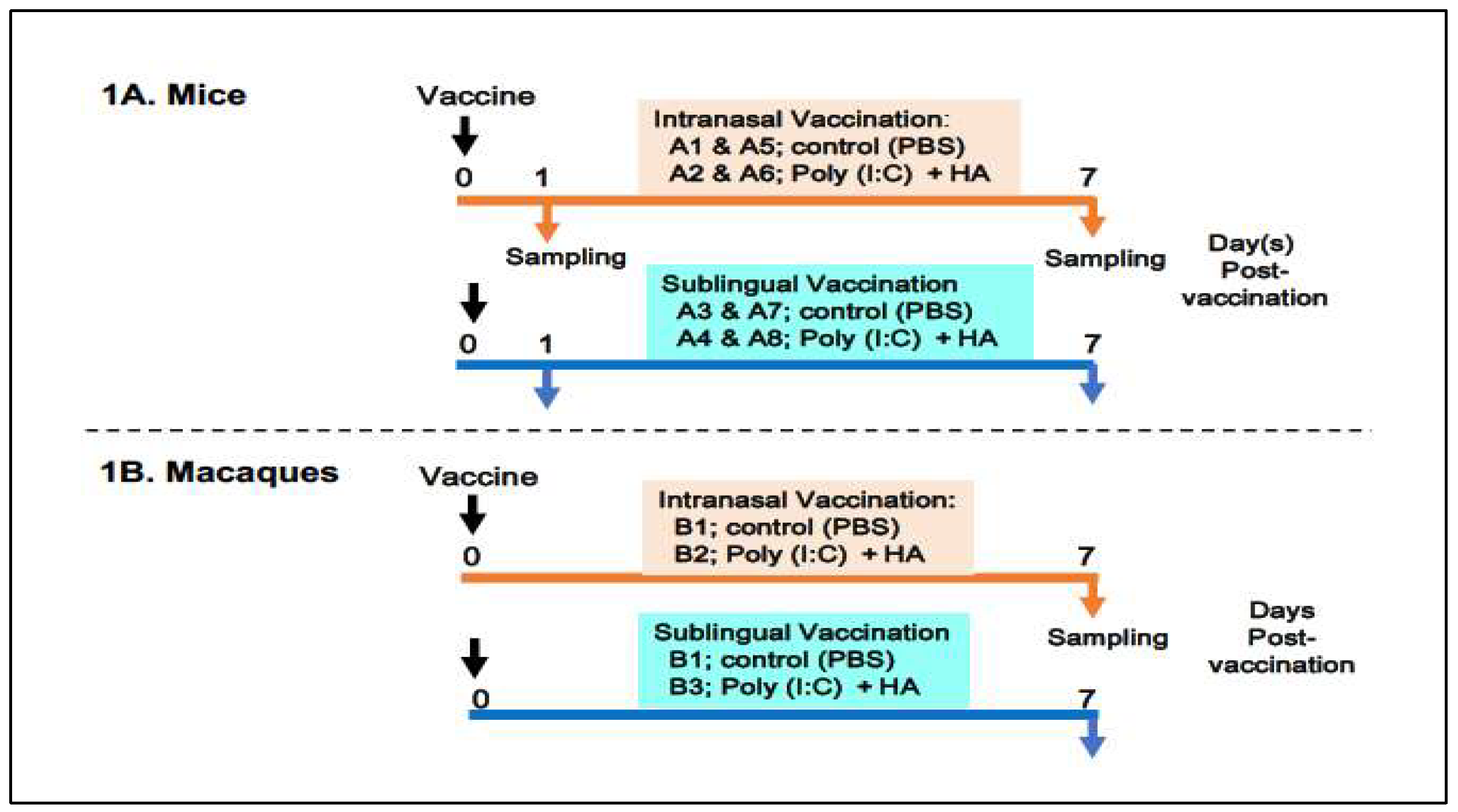

Figure 1).

(In mice)

Figure 1A shows an outline of vaccination and sampling in mice. Thirty-two mice were divided into eight groups, A1 to A8, with each group including four animals. Groups A1, A2, A5, and A6 were designated for intranasal administration, whereas groups A3, A4, A7, and A8 were allocated for sublingual vaccinations. Groups A1 and A5 were administered PBS as a control of the oral route, whereas groups A3 and A7 received PBS as a control of the sublingual route. Groups A2 and A6 received the Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccine via the intranasal route, whereas groups A4 and A8 were vaccinated sublingually. The animals were given either 10 μL/head of PBS in the control groups (A1, A5, A3, and A7) or 10 μL/head of vaccine for each of the vaccinated groups (A2, A6, A4, and A8). Mice from groups A1 to A4 and A5 to A8 were euthanized to obtain blood and tissue samples at 1 day or 7 days post-administration of PBS or the vaccine, respectively. Tissue samples from the olfactory bulb, pons, lung, tongue, and (submandibular) lymph node were obtained at two times points.

(In macaque monkeys)

Figure 1B shows six macaque monkeys divided into three groups, B1 to B3, with each group consisting of two macaques. Group B1 was used as a control for intranasal or sublingual administration of PBS. Group B2 (intranasal route) and Group B3 (sublingual route) received the vaccine under previously described conditions [vaccines’ paper]. Briefly, macaques were administered either 500 μL of PBS per head in the control group (B1) or 500 μL of the vaccine per head in the vaccinated groups (B2 and B3). Macaques from three groups (B1, B2, and B3) were euthanized to collect blood and tissues 7 days post-administration of PBS or the vaccine. Tissue samples from the olfactory bulb, pons, lung, tongue, and (submandibular) lymph node were obtained at the indicated time point.

2.4. Blood Testing

In mice, fresh blood samples were collected from animals at two time points, 1 and 7 days after vaccination via intranasal or sublingual routes. After centrifugation of the blood, the plasma samples were assayed for 13 biochemical tests: total protein, albumin, albumin/globulin ratio, total bilirubin, aspartate transaminase (glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase), alanine transaminase (glutamic pyruvic transaminase), alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, urea nitrogen-BUN, creatinine, total cholesterol, neutral fats, and C-reactive protein (CRP).

In macaque monkeys, fresh blood samples were collected 7 days after sublingual or intranasally vaccination. Whole blood samples were examined for the complete blood count of eight items: red blood cells, white blood cells (WBC), hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean cell volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, and platelets. Plasma samples were assayed for the same 13 items as mice.

2.5. RNA Isolation

Tissue samples from each animal of the experimental groups, A1~A8 of mice and B1~B3 of macaques, were used for RNA preparation. RNA isolation and its quality tests were performed as previously described [

13]. In both mice and macaques, equal amounts of purified RNAs from each tissue of individual animals were combined and pooled per the group and then used for gene expression analyses.

2.6. Gene Expression Analyses Using Quantitative Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-qPCR)

The mRNA levels of target genes in tissue samples were determined using RT-qPCR as described previously [

13]. cDNA was synthesized from the pooled RNA using Prime Script Reverse Transcriptase with RNase Inhibitor (Takara Bio Inc.), dNTP mixture (Promega Corp., USA), and Oligo dT primers (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Real-time PCR was performed using the Mx3000P QPCR System (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA) with a SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNase H Plus) Kit (Takara Bio Inc., Japan). Specific primers for twelve mouse genes:

Saa3, Tnf, IL6, IL1b, Ccl2, Timp1, C2, Ifi4, Aif1, Omp, Nos2 and

Gzmb; nine monkey genes:

SAA2, TNF,

IL1Bb,

IL6,

AIF1, CCL2, TIMP1, C2, and

GZMB; and the reference gene low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 10 (

Lrp10/LRP10) were designed using Primer3 and Primer-BLAST [

17]. A standard curve was generated by serial dilution of a known amount of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase amplicon to calculate the cDNA copy number of the genes. The PCR conditions included initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 s, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s and annealing/extension at 63°C for 30 s, with a dissociation curve. The quantity of target gene mRNA was expressed as the ratio against that of a suitable reference gene,

LRP10 [

18].

2.7. Histological Examination

Tissue samples were collected from three macaque groups: B1 (control), B2 (intranasal vaccine), and B3 (sublingual vaccine) 7 days post-vaccination and subsequently fixed with formaldehyde. A paraffin block of the formaldehyde-fixed samples was sectioned into 4-μm slices using a microtome, REM-710 (Yamato Kohki Industrial, Asaka, Japan). The sections were stained with hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and subsequently examined using an Olympus BX43 optical microscope (Evident, Tokyo, Japan) under ×10 eye and ×10 and/or ×40 objective lenses.

3. Results

3.1. Blood Testing

Blood tests were conducted to evaluate the deleterious effects of a Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted sublingual and intranasal vaccine in both mice and macaque monkeys. Plasma samples from mice vaccinated sublingually and intranasally were analyzed for 13 biochemical blood tests (total protein, albumin, albumin/globulin ratio, total bilirubin, aspartate and alanine transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, urea nitrogen, creatinine, total cholesterol, neutral fats, and CRP at 1 day and 7 days post-vaccination. Compared to the control group, the 13 biochemical parameters exhibited minimal variation in both sublingually and intranasally vaccinated mice, whereas modest individual differences were observed (data not shown).

In macaque monkeys, fresh blood samples were analyzed for complete blood counts of eight parameters (red blood cells, WBCs, hemoglobin, hematocrit, mean cell volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, and platelets) 7 days post-sublingual and intranasal vaccinations. Plasma samples were analyzed for the same 13 biochemical parameters as mice 7 days post-sublingual and intranasal vaccinations. Minimal differences were observed between the control group and the vaccinated monkeys in the complete blood counts and biochemical blood tests, except for individual variations (data not shown).

The Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccine, administered sublingually or intranasally to both mice and monkeys, had negligible adverse effects on blood tests conducted 7 days post-vaccination.

3.2. Gene Expression Analyses of Inflammation-Related Genes

To assess the deleterious effects of Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted sublingual or intranasal vaccines in both mice and macaque monkeys, quantitative gene expression analyses using RT-qPCR were conducted for inflammation-related genes utilizing RNA from several tissues.

Table 1 and

Table 2 represent the target genes, tissue samples, and sampling time points for the gene expression analysis.

3.2.1. In Mice

Table 1 shows the selection of inflammation-associated genes in mice, comprising eight common genes (

Saa3, Tnf, IL-6, IL-1b, Ccl2, Timp1, C2, and

Ifi4) with additional genes (

Aif1, Omp, Nos2, and

Gzmb) for gene expression analysis. RNA samples from five tissues—olfactory bulb, pons, lung, tongue, and lymph node that were obtained 1 day and 7 days post-vaccination, respectively—were used (

Table 1).

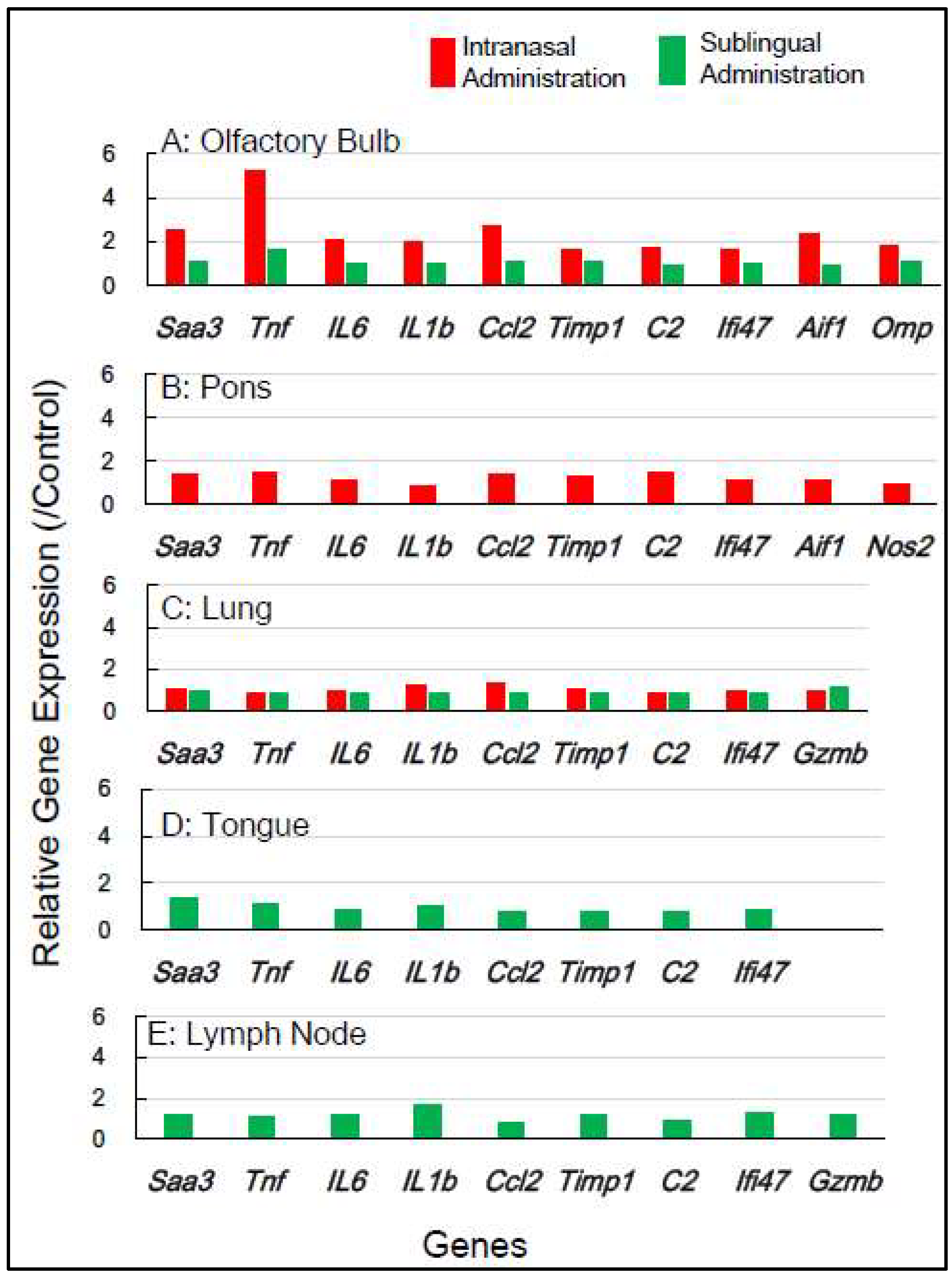

Figure 2 shows the change in expression of inflammation-associated genes in the five tissues 1 day post-vaccination with the intranasal vaccine. In the olfactory bulb, a remarkable upregulation of two genes,

Saa3 and

Tnf, was observed at rates of 3.8 to 5.8 times, respectively, alongside a significant upregulation of additional genes ranging from 1.5 to 2.8 times. In the pons, a moderate upregulation of 1.5 to 2.3 times in the expression of 5 genes—

Saa3, Tnf, Ccl2, Timp1, and C2—was observed. In the lung, a huge upregulation of five genes—

Saa3, Tnf, IL-6, Ccl2, and

Timp1—was observed, ranging from 5.5 to 13.5 times. Conversely, the sublingual vaccine exhibited little effect on the expression profile of inflammation-related genes in the olfactory bulb and other tissues 1 day post-vaccination (

Figure 2).

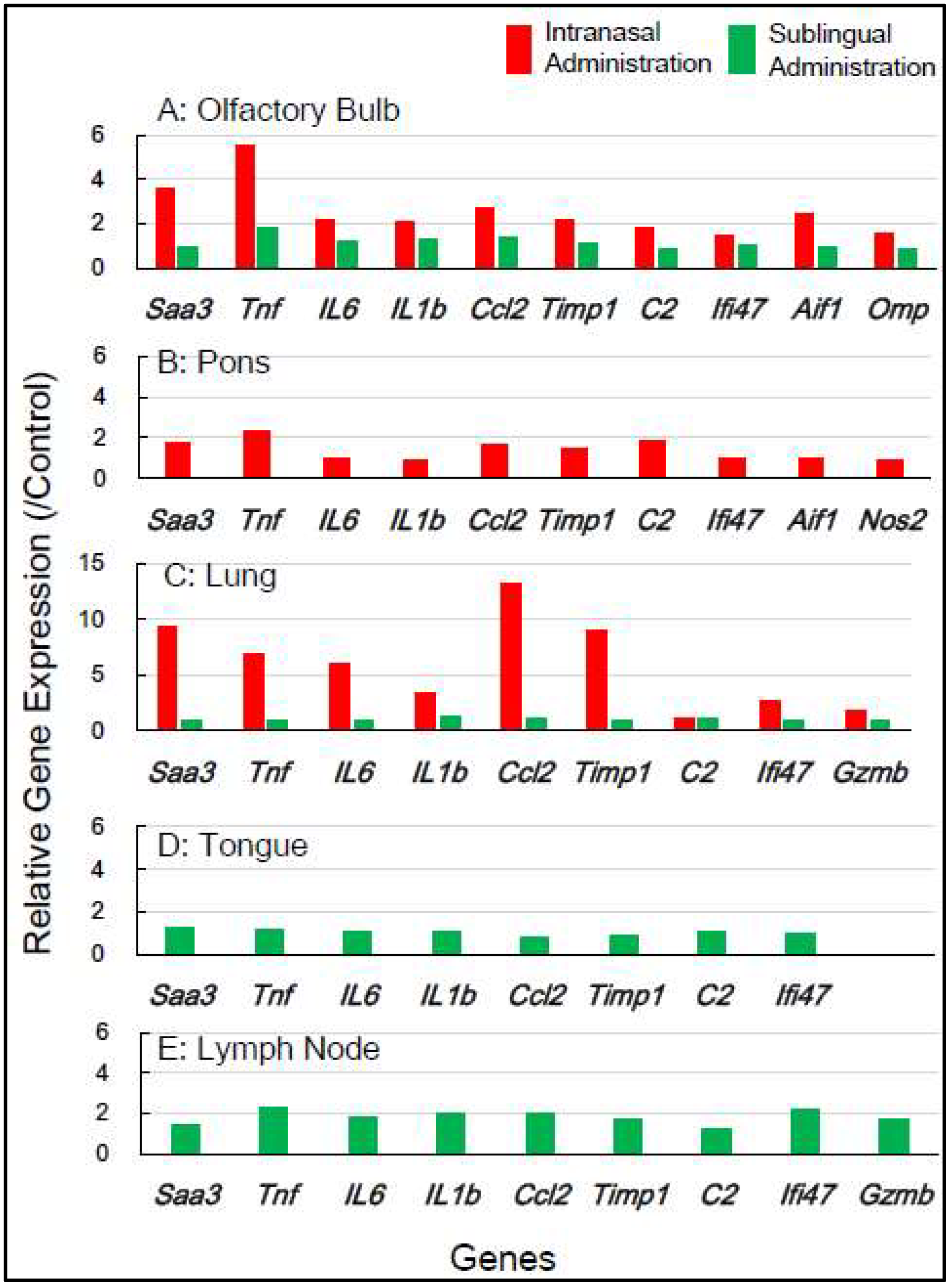

Figure 3 displays the effect of the internasal vaccine on the expression of these genes 7 days post-vaccination. The intranasal vaccine upregulated inflammatory-related genes in both the olfactory bulb and pons 7 days post-vaccination, whereas the sublingual vaccine had negligible effects on the upregulation of these genes in four tissues, except for the lymph node, where a slight upregulation of a few genes was observed (

Figure 3).

In mice, the intranasal administration of the Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccine upregulated

inflammation-related genes in the olfactory bulb and pons at both 1 day and 7 days post-vaccination, including in the lungs 1 day post-vaccination. On the other hand, the sublingual administration of the Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccine resulted in little upregulation of these genes in the examined tissues after both 1 and 7 days. These indicate that the Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccination exhibits negligible side effects when administered sublingually in mice.

3.2.2. In Macaque Monkeys

Gene expression analyses of macaque monkey samples were performed to complement the above-mentioned results in mice because of the differences in nasal structure and function between rodents and primates, including humans. Tissue samples from macaques were obtained from the smallest number of animals, specifically two individuals for each of the control, sublingual, and intranasal vaccination groups. Nine inflammation-associated genes in macaques (

SAA2, TNF, IL6, IL1B, CCL2, TIMP1, C2, AIF1, and

GZMB) were chosen for RT-qPCR analysis utilizing RNA from five tissues, olfactory bulb, pons, lung, tongue, and lymph node, collected 7 days post-vaccination (

Table 2).

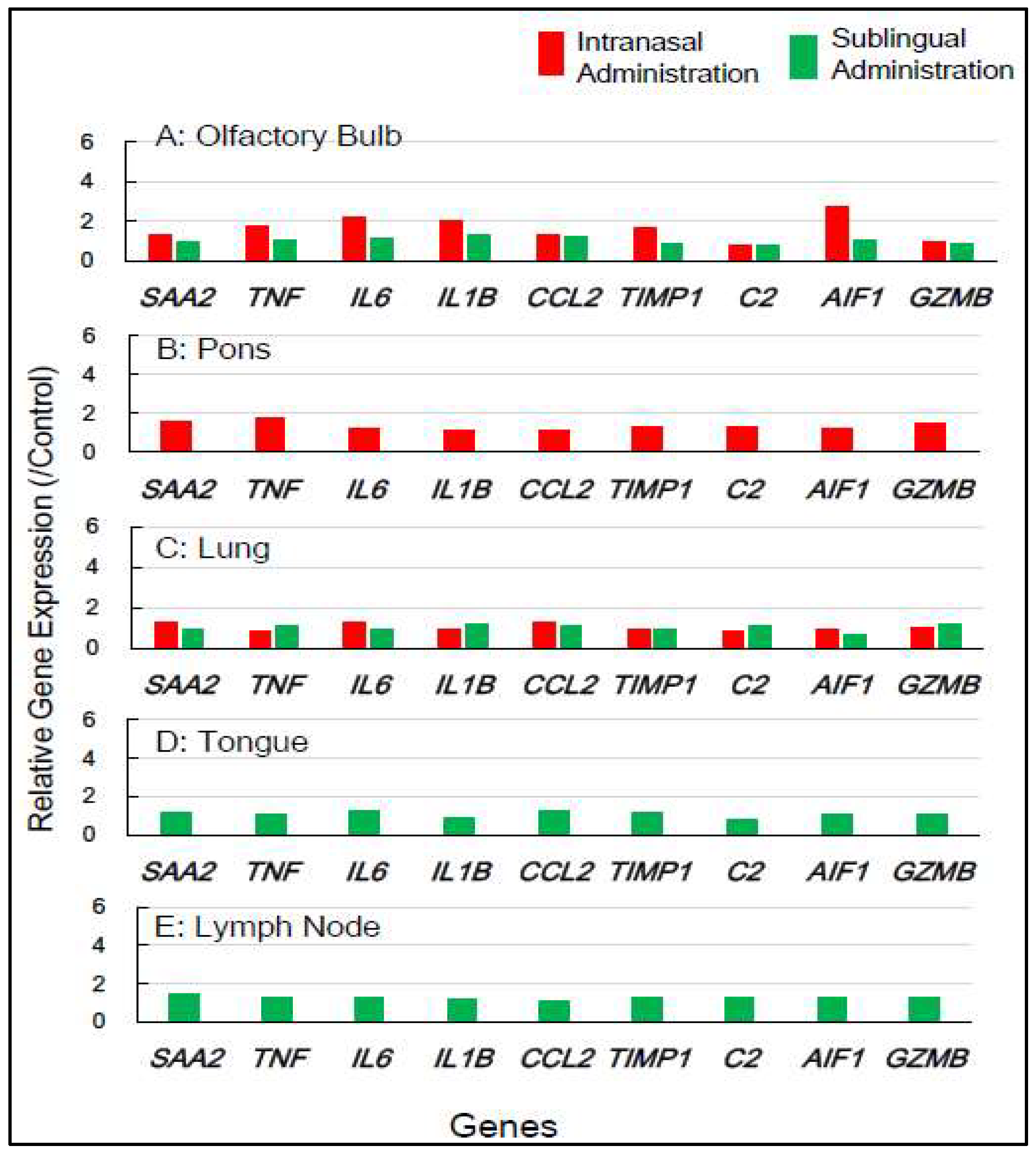

Figure 4 shows that intranasal vaccination significantly upregulated the expression of five genes—

TNF, IL6, IL1B, TIMP1, and

AIF1—by 1.7 to 2.8-fold in the olfactory bulb 7 days post-immunization, but sublingual vaccination resulted in little upregulation of these genes. The intranasal vaccine led to a moderate upregulation, approximately 1.3 to 1.8-fold, of six genes—

SAA2, TNF, TIMP1, C2,

AIF1, and

GZMB—in the pons (

Figure 4). The sublingual vaccinations elicited a slight increase, approximately 1.2 to 1.4-fold, in the expression of several genes, specifically

SAA2, IL6,

CCL2,

TIMP1, and

AIF1, in lymph nodes 7 days post-vaccination (

Figure 4). No upregulation of gene expression was observed in either the lung or tongue 7 days post-sublingual and/or intranasal immunization (

Figure 4).

In macaques, intranasally administered vaccines also resulted in minimal unfavorable effects in both the olfactory bulb and pons, but sublingual vaccination had little side effects in these tissues. Sublingual vaccination elicited a slight upregulation of these genes in the lymph nodes, indicating the activation of an immune-inflammatory response in the lymphatic sites near the vaccinations. The gene expression analyses of inflammation-associated factors suggest that sublingual administration of the Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccine is safe, especially for macaque monkeys.

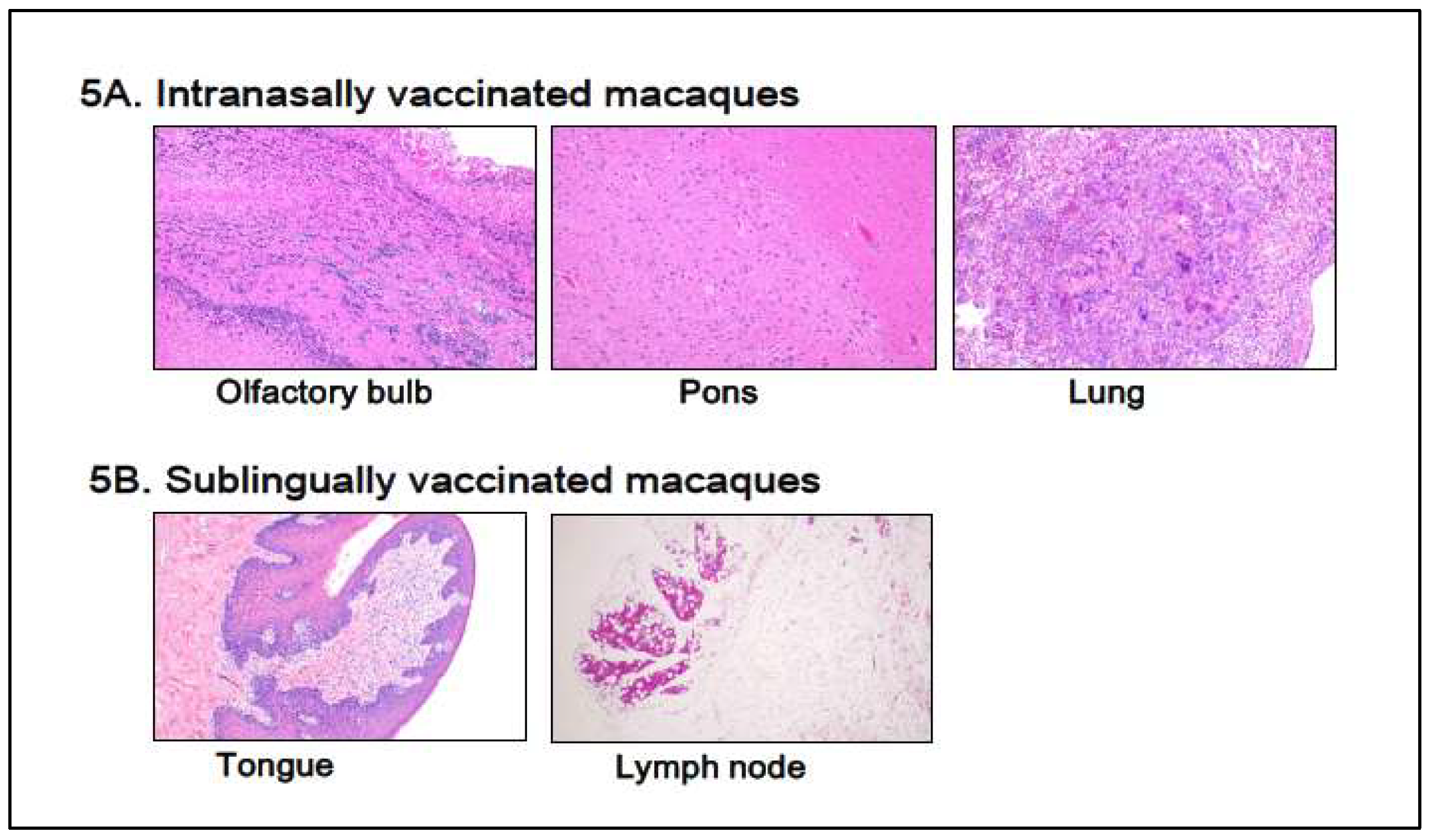

3.3. Histological Examination

Histological examinations were performed on macaque monkey samples because the structure and/or function of the oral and nasal cavities, other biological characteristics, and/or immune-inflammatory responses are quite similar to those of humans. Patho-histopathological investigations were conducted using optical microscopy on HE-stained tissue specimens taken from macaques who were given PBS (control) or Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccine via sublingual and intranasal routes, respectively.

Figure 5 shows typical histological photographs for the intranasally vaccinated group, olfactory bulb, pons, and lung (

Figure 5A), and the sublingually vaccinated group, tongue, and lymph node (

Figure 5B). Intranasally vaccinated macaques had trace amounts of infiltrated white cells (lymphocytes, macrophages, and eosinophils) in the olfactory bulb, pons, and lung (

Figure 5A), but the same amount of infiltrated white cells was detected in tissue specimens from control animals (data not shown). A slight infiltration of white cells was found in both the tongue and the lymph node (

Figure 5B), as seen in control animal samples.

Thus, Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccination appears to have almost no histopathologically detectable negative effect on tissues associated with vaccinated locations, such as sublingual and intranasal cavities, in macaques.

4. Discussions

4.1. Poly(I:C) Adjuvant

An immunity-stimulating adjuvant is a crucial component for the development of a protein-based vaccine. Pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) are adjuvants for numerous subunit vaccines. Poly(I:C) serves as a PAMP-adjuvant to stimulate several components of the host defense in a manner analogous to a viral infection. Poly(I:C) is a synthetic double-stranded RNA molecule that activates both innate and adaptive immune responses. It mimics viral infections and elicits host immune responses by activating particular pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). Poly(I:C) primarily signals through TLR3, a transmembrane and mostly endosomal receptor, and MDA-5, a cytoplasmic receptor. Poly(I:C) induces an interferon response through TLR3 and MDA-5 signaling, resulting in the production of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and/or costimulatory factors. Poly(I:C) remains unapproved owing to its adverse effects, including fever and the production of proinflammatory cytokines. This is why more preclinical investigations on its safety utilizing non-human primates (NHPs) are needed. In previous studies, we developed a Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccine administered via the sublingual cavity. The sublingual vaccination adjuvanted with Poly(I:C) appeared to be safe based on preclinical examinations. The present work thoroughly evaluated the safety of the Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccine by comparing its sublingual and intranasal administrations in both mice/rodents and macaques/NHPs as discussed below.

4.2. Safety Assessment of the Vaccine in Mice

The administration site or route is another limiting aspect in the development of effective vaccination. Airborne viruses, SARS-CoV-2 and influenza, invade the mucosal surfaces of the upper respiratory tract. Consequently, the vaccine ought to induce the production of virus antigen-specific IgA in the mucosal tissue of the oral cavity and/or nasal passages, rather than generating specific IgG or IgA in the blood [

7,

28]. Recently, alternate administration routes, such as oral delivery, for allergy immunotherapy or vaccination have been developed to provoke mucosal immune responses distinct from systemic responses [

29]. Vaccinations via these approaches have greater efficacy than conventional subcutaneous vaccinations. Despite the establishment and partial practical application of intranasal vaccines [

30], adverse effects on the brain/central nervous system or lungs have been described from oral administration [

20,

31,

32]. On the contrary, the oral/sublingual vaccine has satisfactory efficacy and improved safety, devoid of adverse effects on the brain [

33]. In primates, including monkeys and humans, the sublingual region possesses ample space, making it more conducive for vaccinations compared to the nasal cavity. Sublingual vaccination, therefore, should better activate the mucosal immune response. Moreover, the previously mentioned adverse effects of the Poly(I:C) adjuvant were reported in intranasal administration using a mouse model [

19,

20,

32]. The reported side effects probably result from differences in adjuvant reactivity between rodents and primates related to nasal structure and function [

34], genomic characteristics, and immune response [

35]. Notably, Poly(I:C) serves as the most effective inducer of type I interferon among TLR agonists, activating the proinflammatory cytokine pathway in rodents [

36].

Mice/rodents exhibit nocturnal behavior and possess an exceptionally acute sense of smell, facilitated by their olfactory system and associated neural pathways, enabling their survival in darkness. The olfactory system of mice exhibits higher reactivity to foreign compounds, including vaccines, that are administered through the intranasal route. Conversely, macaques/primates are diurnal and do not require sensitive olfactory reactivity as mice/rodents. These biomedical factors explain why the intranasally administered vaccination elicited significant adverse effects in mice but not in macaques. In preclinical evaluations of vaccinations and/or medications administered intranasally in mice/rodents, it is necessary to account for the hypersensitive reactivity of the nasal and olfactory systems, which differ from those in macaques/primates.

4.3. Gene Expression Analyses as Vaccine Safety Evaluation

Gene expression analysis is a method for precisely monitoring intracellular molecular events at the mRNA level, which serves as precursors for proteins, enzymes, cytokines, and inflammatory mediators. Real-time RT-PCR (RT-qPCR) is a reliable technique for quantifying changes in mRNA expression. RT-qPCR assays of proinflammatory genes have been suggested as a valuable tool for the safety assessment of vaccinations [

37,

38]. In our prior preclinical studies using macaques, we reported that the sublingual administration of a Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccine appeared safe, as evidenced by RT-qPCR analysis of inflammatory-related genes utilizing mRNA from PBWCs [

13]. In PBWCs, the Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted sublingual vaccination upregulated inflammatory genes 1 day post-vaccination, but baseline levels were restored 7 days post-vaccination. The present study investigated the effects of Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted sublingual vaccination on the expression of the inflammatory-related genes, which were

Saa3, Tnf, IL1b, IL6, Ifi4, Ccl2, Timp1, C2, Aif, and

Omp in mice and

SAA2, TNF, IL1B, IL6, CCL2, TIMP, C2, GZMB, AIF1D, and

OMP, in macaques in the brain (olfactory bulb and pons) in both mice and macaques and compared with internasal vaccination. In the olfactory bulb of mice, the intranasal administration of a Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccine led to markedly upregulated expression of these genes even 7 days post-vaccination, unlike sublingual vaccination (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). The adverse effects that led to upregulated inflammatory genes in the olfactory bulb, corresponded to unique molecular events mediated by intranasal vaccination in mice, which resulted from the sensitive reactivity of olfactory perception in mice.

In another brain region, the pons, upregulation of many inflammatory genes (

Saa3, Tnf, IL1b, IL6, Ifi4, Ccl2, and

C2) was still evident 7 days after intranasal vaccinations, but not sublingual vaccinations, in mice (

Figure 3). In macaque pons, upregulation of these inflammation-related genes was observed 7 days after intranasal vaccinations, but not sublingual vaccination (

Figure 4). Intranasal vaccination induces a high risk of Bell’s palsy with inactivated influenza vaccines [

39]. The association between intranasal vaccines and Bell’s palsy was also reviewed in a recent article [

40]. Bell's palsy is most commonly caused by an impairment of the facial nerve that emerges from the facial nerve nucleus in the pons [

41]. As above-mentioned, vaccine administration via an intranasal route resulted in upregulated inflammation-related genes in pons 7 days after vaccination in both mice and macaques. Upregulated expression of these genes may induce a proinflammatory condition that impairs the facial nerve. Thus, vaccination-associated Bell's palsy could be mediated by upregulated gene expression in the pons, which is caused by intranasal vaccines. Based on the gene expression analyses, one should avoid intranasal administration of vaccines owing to their deleterious effects on the brain, both on the olfactory bulb and pons, and therefore one should look into alternate routes, such as sublingual administration.

4.4. Use of PBWCs for Safety Assessment of Vaccines and/or Adjuvants

The lung is a suitable tissue for evaluating the harmful effects of vaccines using gene expression analyses [

20]. Except for C2a, the intranasally administered vaccine significantly upregulated the inflammation-related genes in mice's lungs only 1 day after immunization, but not after 1 or 7 days after sublingual vaccination. No upregulation of these inflammation-related genes was observed in the lung of macaques 7 days after sublingual vaccinations. In previous studies, we found that administering a Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccine sublingually upregulated inflammatory/proinflammatory genes in PBWCs on the first day after vaccination, but basal levels were restored after 7 days [

13]. PBWCs respond to administered vaccinations by upregulating inflammation-related genes in a time course comparable to that of the lung. These findings imply that PBWCs are a far superior monitoring window than the lung for assessing the adverse effects of vaccinations and/or adjuvants, as assessing PBWCs is non-invasive, which is advantageous in clinical applications.

Compared to RT-qPCR, histopathological examination was less sensitive in assessing vaccine-induced adverse reactions. The histological method detected little adverse event in the olfactory bulb and pons 7 days after vaccinations in macaques, despite upregulated inflammation-related marker genes in these tissues.

4.5. Safety of the Sublingual Poly(I:C)-Adjuvanted Vaccine

An adjuvant is essential for the safety and effectiveness of a mucosal vaccine. Although numerous adjuvants exist, two are particularly notable. MF59 or AS03 is an oil-in-water nano-emulsion that stimulates Th1/Th2 [

5]. The other is double-stranded (ds) RNA poly(I:C), a ligand for TLR 3 that induces immunological and proinflammatory responses [

6]. MF59 and AS03 have been authorized as adjuvants for intramuscularly administered influenza vaccines. However, the clinical application of Poly(I:C) as a vaccine adjuvant remains unapproved, except for restricted use in oncology. Studies utilizing intranasal vaccination in mice predominantly indicated the generation of proinflammatory cytokines and associated factors mediated by Poly(I:C) [

19,

20]. Nevertheless, these proinflammatory reactions were overestimated owing to the hypersensitive reaction observed with intranasal administration of the Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccination in mice, as mentioned above. In our prior studies utilizing a non-human primate model, the sublingually administered Poly(I:C)-adjuvant vaccine showed safety outcomes equivalent to those of AddaS03, a non-clinical derivative of the AS03 adjuvant, when assessing total blood count, biochemical blood tests, and plasma CRP. The sublingual Poly(I:C)-adjuvant vaccine exhibited gene expression profiles identical to those of AddaS03 concerning proinflammatory cytokines and associated factors (IL12a, IL12b, GZMB, IFN-alpha1, IFN-beta1, and CD69) [

13]. The Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted vaccination elicited plasma production levels comparable to those of AddaS03 in inflammation-related cytokines: IFN-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-12, and IL-17. The safety of the Poly(I:C) adjuvant should be considered comparable to that of AS03 in the case of sublingual vaccinations.

Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted sublingual vaccination evoked hitherto unrecognized immunological responses, including aberrant upregulation or downregulation of gene expression associated with immune suppression or tolerance, Treg differentiation, and T cell exhaustion [

13]. Thus, the Poly(I:C) adjuvant elicits a balanced "Yin/Yang"-like enhancement and suppression of immune responses, rendering it both safe and effective for sublingual vaccination [

13,

14].

5. Conclusion

Poly(I:C)-adjuvanted influenza HA vaccine administered sublingually had little adverse effect and was assessed as safe based on RT-qPCR results of inflammatory-associated genes in the brain (olfactory bulb and pons), lungs, tongue, and (submandibular) lymph node in both macaques and mice. Conversely, the intranasally administered vaccination caused deleterious side effects by upregulating these genes in the olfactory bulb, pons, and lungs in both macaques and mice, as well as severe detrimental effects in brain (olfactory bulb and pons), particularly in mice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T. Y. and S.N.; methodology, F.M.; investigation, F.M and S.N.; resources, T. Y.; data curation, M.H. and K.W.; writing-original draft preparation, S.N., M.H. and F.M.; writing-review and editing, S.N. T. Y., and A. K.; visualization, F.M., and K.T.; supervision and project administration, T. Y.; funding, T. Y.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of Institutional Animal Care and Committee Guide of Intelligence and Technology Lab, Inc. (ITL) based on the Guidelines for Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments and approved by the Animal Care Committee of the ITL (approved number: AE2022022, date: 24 November 2022). This study was also approved by the ITL Biosafety Committee (approved number: BS2022022, date: 24 November 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from S.N. upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank to Kazuhiro Kawai for his invaluable technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pushparajah, D.; Jimenez, S.; Wong, S.; Alattas, H.; Nafissi, N.; Slavcev, R.A. Advances in gene-based vaccine platforms to address the COVID-19 pandemic. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2021, 170, 113–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soema, P.C.; van Riet, E.; Kersten, G.; Amorij, J.-P. Development of Cross-Protective Influenza A Vaccines Based on Cellular Responses. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arashkia, A.; Jalilvand, S.; Mohajel, N.; Afchangi, A.; Azadmanesh, K.; Salehi-Vaziri, M.; Fazlalipour, M.; Pouriayevali, M.H.; Jalali, T.; Nasab, S.D.M.; et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 spike (S) protein based vaccine candidates: State of the art and future prospects. Rev. Med Virol. 2020, 31, e2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolgin, E. How protein-based COVID vaccines could change the pandemic. Nature 2021, 599, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rosa, S.C.; Cohen, K.W.; Bonaparte, M.; Fu, B.; Garg, S.; Gerard, C.; A Goepfert, P.; Huang, Y.; Larocque, D.; McElrath, M.J.; et al. Whole-blood cytokine secretion assay as a high-throughput alternative for assessing the cell-mediated immunity profile after two doses of an adjuvanted SARS-CoV-2 recombinant protein vaccine candidate. Clin. Transl. Immunol. 2022, 11, e1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, A.M.; Corthésy, B.; Merkle, H.P. Particulate formulations for the delivery of poly(I:C) as vaccine adjuvant. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 1386–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainai, et al. Human immune responses elicited by an intranasal inactivated H5 influenza vaccine, Microbiology and Immunology 64 (2020): 313–325.

- Mudgal R, et al. Prospects for mucosal vaccine: shutting the door on SARS-CoV-2, Human Vaccine Immnunother 16 (2020): 2921–2931.

- Ambrose, C.S.; Luke, C.; Coelingh, K. Current status of live attenuated influenza vaccine in the United States for seasonal and pandemic influenza. Influ. Other Respir. Viruses 2008, 2, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemiale, F.; Kong, W.; Akyürek, L.M.; Ling, X.; Huang, Y.; Chakrabarti, B.K.; Eckhaus, M.; Nabel, G.J. Enhanced Mucosal Immunoglobulin A Response of Intranasal Adenoviral Vector Human Immunodeficiency Virus Vaccine and Localization in the Central Nervous System. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 10078–10087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, E.; Momose, H.; Hiradate, Y.; Mizukami, T.; Hamaguchi, I. Establishment of a novel safety assessment method for vaccine adjuvant development. Vaccine 2018, 36, 7112–7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Tanji, M.; Mitsunaga, F.; Nakamura, S. SARS-CoV-2 sublingual vaccine with RBD antigen and poly(I:C) adjuvant: Preclinical study in cynomolgus macaques. Biol. Methods Protoc. 2023, 8, bpad017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Mitsunaga, F.; Wasaki, K.; Kotani, A.; Tajima, K.; Tanji, M.; Nakamura, S. Mechanism Underlying the Immune Responses of a Sublingual Vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 with RBD Antigen and Adjuvant, Poly(I:C) or AddaS03, in Non-human Primates. Arch. Microbiol. Immunol. 2023, 07, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Hirano, M.; Mitsunaga, F.; Wasaki, K.; Kotani, A.; Tajima, K.; Nakamura, S. Molecular Events in Immune Responses to Sublingual Influenza Vaccine with Hemagglutinin Antigen and Poly(I:C) Adjuvant in Nonhuman Primates, Cynomolgus Macaques. Vaccines 2024, 12, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pillai, K.; Akhter, J.; Chua, T.C.; Morris, D.L. A formulation for in situ lysis of mucin secreted in pseudomyxoma peritonei. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 134, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.; Nagatake, T.; Nasu, A.; Lan, H.; Ikegami, K.; Setou, M.; Hamazaki, Y.; Kiyono, H.; Yagi, K.; Kondoh, M.; et al. Impaired airway mucociliary function reduces antigen-specific IgA immune response to immunization with a claudin-4-targeting nasal vaccine in mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Coulouris, G.; Zaretskaya, I.; Cutcutache, I.; Rozen, S.; Madden, T.L. Primer-BLAST: A tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 134–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielsson et al. Evaluation of Reference Genes for Studies of Gene Expression in Human Adipose Tissue. Obesity Research. 13 (2005): 649-652.

- Pizarro-Delgado, J.; Deeney, J.T.; Martín-del-Río, R.; Corkey, B.; Tamarit-Rodriguez, J. Direct stimulation of islet insulin secretion by glycolytic and mitochondrial metabolites in KCl-depolarized islets. Plos One 2014, 11, e0166111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, E.; Asanuma, H.; Momose, H.; Furuhata, K.; Mizukami, T.; Hamaguchi, I. Immunogenicity and Toxicity of Different Adjuvants Can Be Characterized by Profiling Lung Biomarker Genes After Nasal Immunization. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loo, G.; Bertrand, M.J.M. Death by TNF: a road to inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2022, 23, 289–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tritto, E.; Muzzi, A.; Pesce, I.; Monaci, E.; Nuti, S.; Galli, G.; Wack, A.; Rappuoli, R.; Hussell, T.; De Gregorio, E. The Acquired Immune Response to the Mucosal Adjuvant LTK63 Imprints the Mouse Lung with a Protective Signature. J. Immunol. 2007, 179, 5346–5357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, B.S.; Forwood, M.R.; Morrison, N.A. Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 (MCP-1/CCL2) Drives Activation of Bone Remodelling and Skeletal Metastasis. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2019, 17, 538–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.-F.; Chuang, T.-Y.; Lan, M.-Y.; Chin, Y.-C.; Wang, W.-H.; Lin, Y.-Y. Excessive Expression of Microglia/Macrophage and Proinflammatory Mediators in Olfactory Bulb and Olfactory Dysfunction After Stroke. Vivo 2019, 33, 1893–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heneka, M.T.; Galea, E.; Gavriluyk, V.; Dumitrescu-Ozimek, L.; Daeschner, J.; O'Banion, M.K.; Weinberg, G.; Klockgether, T.; Feinstein, D.L. Noradrenergic Depletion Potentiates β-Amyloid-Induced Cortical Inflammation: Implications for Alzheimer's Disease. J. Neurosci. 2002, 22, 2434–2442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liy, P.M.; Puzi, N.N.A.; Jose, S.; Vidyadaran, S. Nitric oxide modulation in neuroinflammation and the role of mesenchymal stem cells. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 246, 2399–2406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsunaga, F.; Nakamura, S. A Sensitive and Simple Method to Assess NK Cell Activity by RT-qPCR for Granzyme B Using Spleen and Blood. J. Biosci. Med. 2021, 09, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainai, A.; van Riet, E.; Ito, R.; Ikeda, K.; Senchi, K.; Suzuki, T.; Tamura, S.; Asanuma, H.; Odagiri, T.; Tashiro, M.; et al. Human immune responses elicited by an intranasal inactivated H5 influenza vaccine. Microbiol. Immunol. 2020, 64, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudgal, R.; Nehul, S.; Tomar, S. Prospects for mucosal vaccine: shutting the door on SARS-CoV-2. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2020, 16, 2921–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, C.S.; Luke, C.; Coelingh, K. Current status of live attenuated influenza vaccine in the United States for seasonal and pandemic influenza. Influ. Other Respir. Viruses 2008, 2, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemiale, F.; Kong, W.; Akyürek, L.M.; Ling, X.; Huang, Y.; Chakrabarti, B.K.; Eckhaus, M.; Nabel, G.J. Enhanced Mucosal Immunoglobulin A Response of Intranasal Adenoviral Vector Human Immunodeficiency Virus Vaccine and Localization in the Central Nervous System. J. Virol. 2003, 77, 10078–10087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, E.; Momose, H.; Hiradate, Y.; Mizukami, T.; Hamaguchi, I. Establishment of a novel safety assessment method for vaccine adjuvant development. Vaccine 2018, 36, 7112–7118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.-H.; Nguyen, H.H.; Cuburu, N.; Horimoto, T.; Ko, S.-Y.; Park, S.-H.; Czerkinsky, C.; Kweon, M.-N. Sublingual vaccination with influenza virus protects mice against lethal viral infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 1644–1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotiwala, F.; Upadhyay, A.K. Next Generation Mucosal Vaccine Strategy for Respiratory Pathogens. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mestas, J.; Hughes, C.C.W. Of mice and not men: Differences between mouse and human immunology. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 2731–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longhi, M.P.; Trumpfheller, C.; Idoyaga, J.; Caskey, M.; Matos, I.; Kluger, C.; Salazar, A.M.; Colonna, M.; Steinman, R.M. Dendritic cells require a systemic type I interferon response to mature and induce CD4+ Th1 immunity with poly IC as adjuvant. J. Exp. Med. 2009, 206, 1589–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momose, H.; Mizukami, T.; Kuramitsu, M.; Takizawa, K.; Masumi, A.; Araki, K.; Furuhata, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Hamaguchi, I. Establishment of a New Quality Control and Vaccine Safety Test for Influenza Vaccines and Adjuvants Using Gene Expression Profiling. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0124392–e0124392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momose, H.; Sasaki, E.; Kuramitsu, M.; Hamaguchi, I.; Mizukami, T. Gene expression profiling toward the next generation safety control of influenza vaccines and adjuvants in Japan. Vaccine 2018, 36, 6449–6455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutsch, M.; Zhou, W.; Rhodes, P.; Bopp, M.; Chen, R.T.; Linder, T.; Spyr, C.; Steffen, R. Use of the Inactivated Intranasal Influenza Vaccine and the Risk of Bell's Palsy in Switzerland. New Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 896–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertin, et al. (2023) Vaccines and Bell's palsy: A narrative review. Therapie. 78:279-292. [CrossRef]

- Toulgoat, F.; Sarrazin, J.; Benoudiba, F.; Pereon, Y.; Auffray-Calvier, E.; Daumas-Duport, B.; Lintia-Gaultier, A.; Desal, H. Facial nerve: From anatomy to pathology. Diagn. Interv. Imaging 2013, 94, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).