Submitted:

28 September 2024

Posted:

29 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Archaeological Setting

2.2. Isolation of DNA, DNA Amplification, Molecular Labelling

2.3. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Data Processing

2.4. Data Analyses

3. Results and Discussions

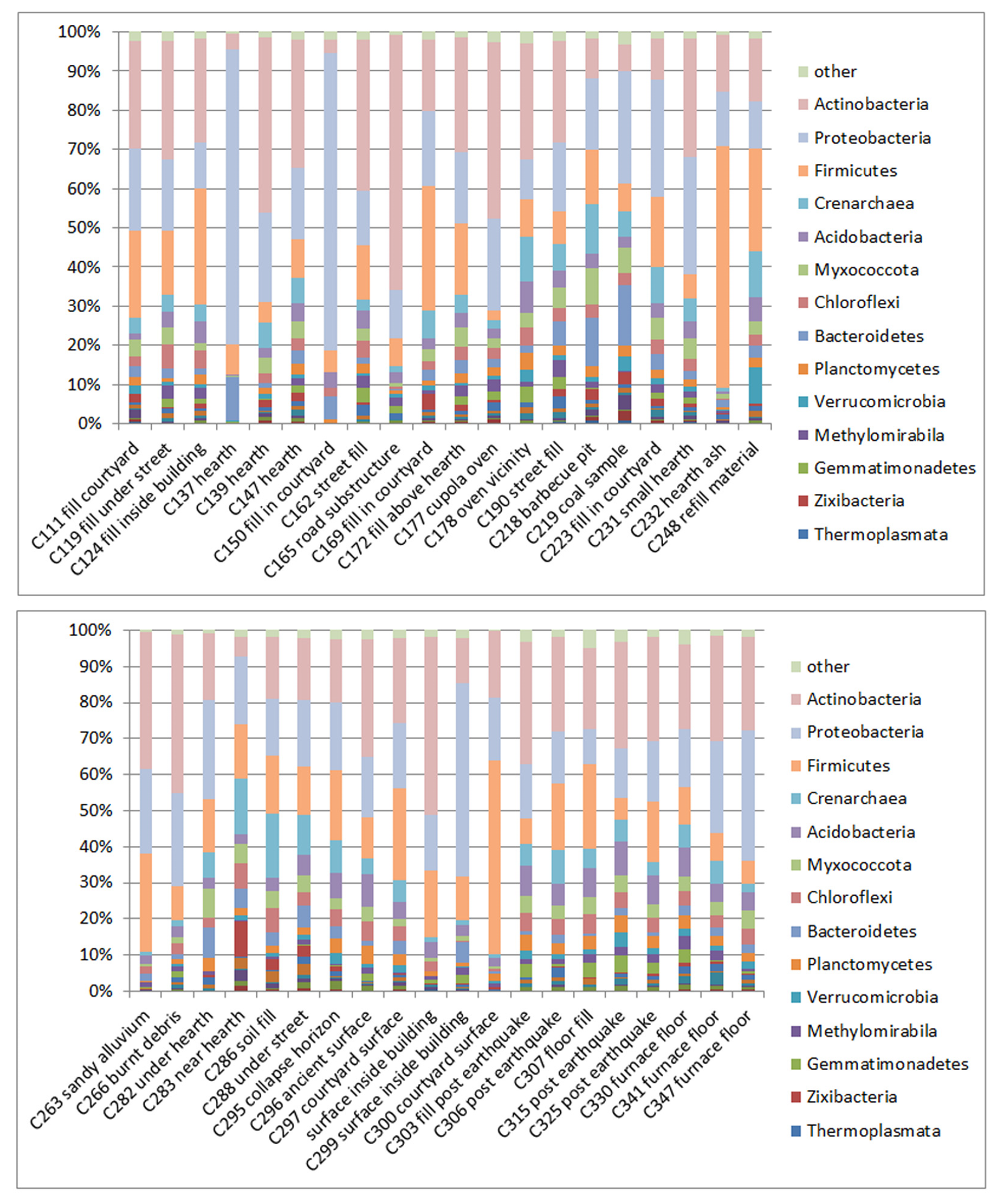

3.1. Composition of Soil Bacteria Communities by Phyla

3.2. Composition of Soil Bacterial Communities by OTUs

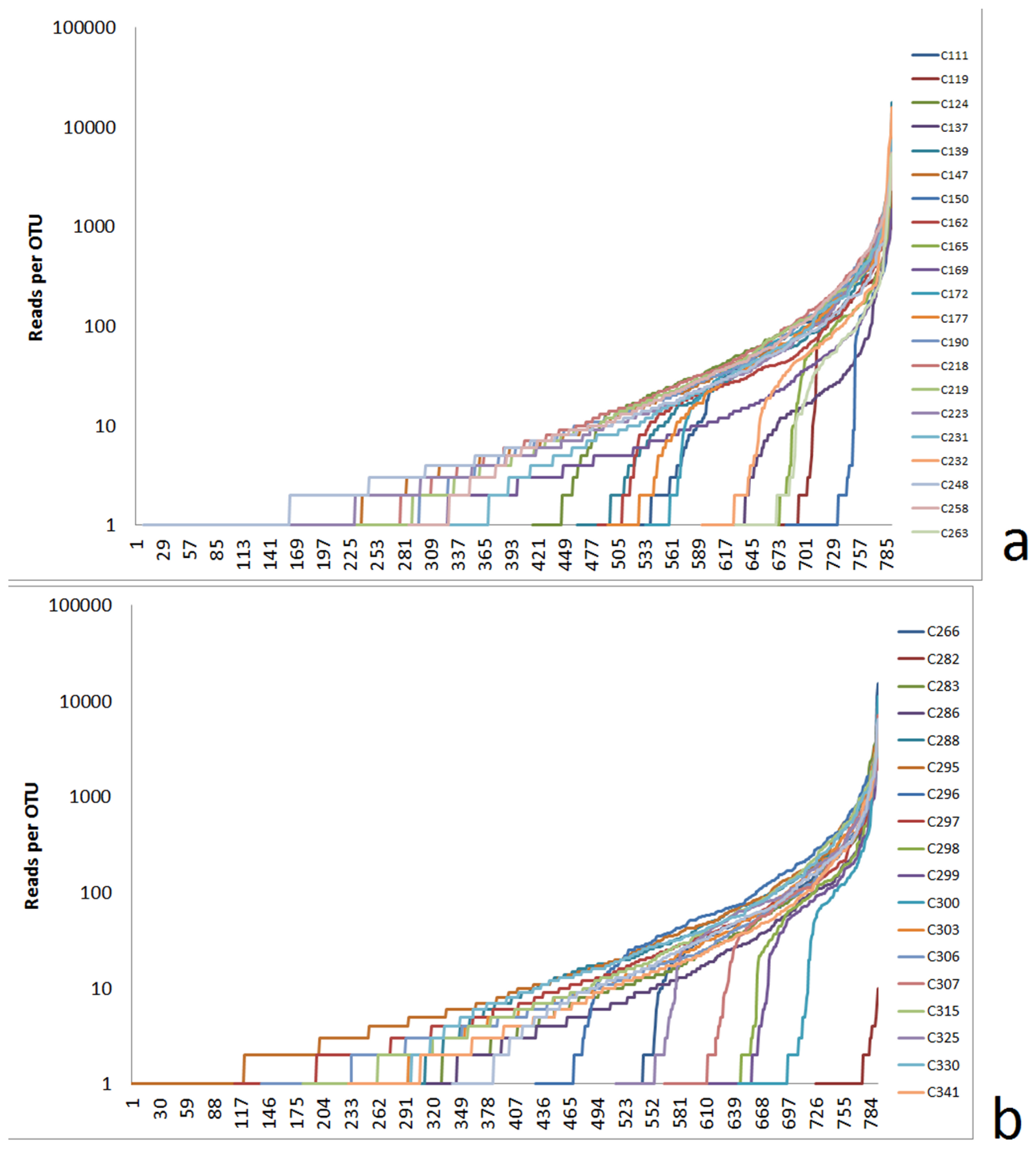

3.2.1. Alpha Diversity Characterized by Logarithmic Rank Functions

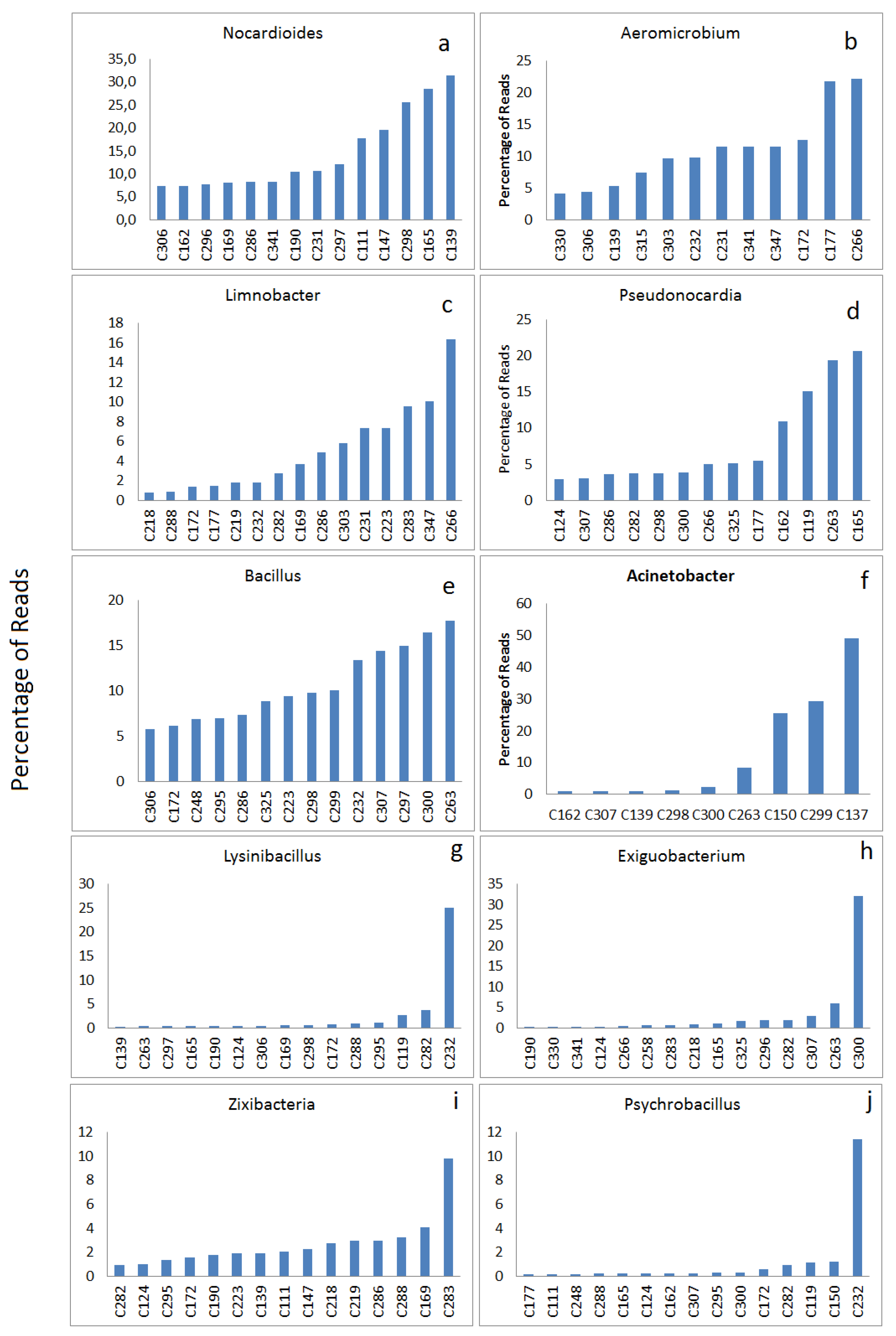

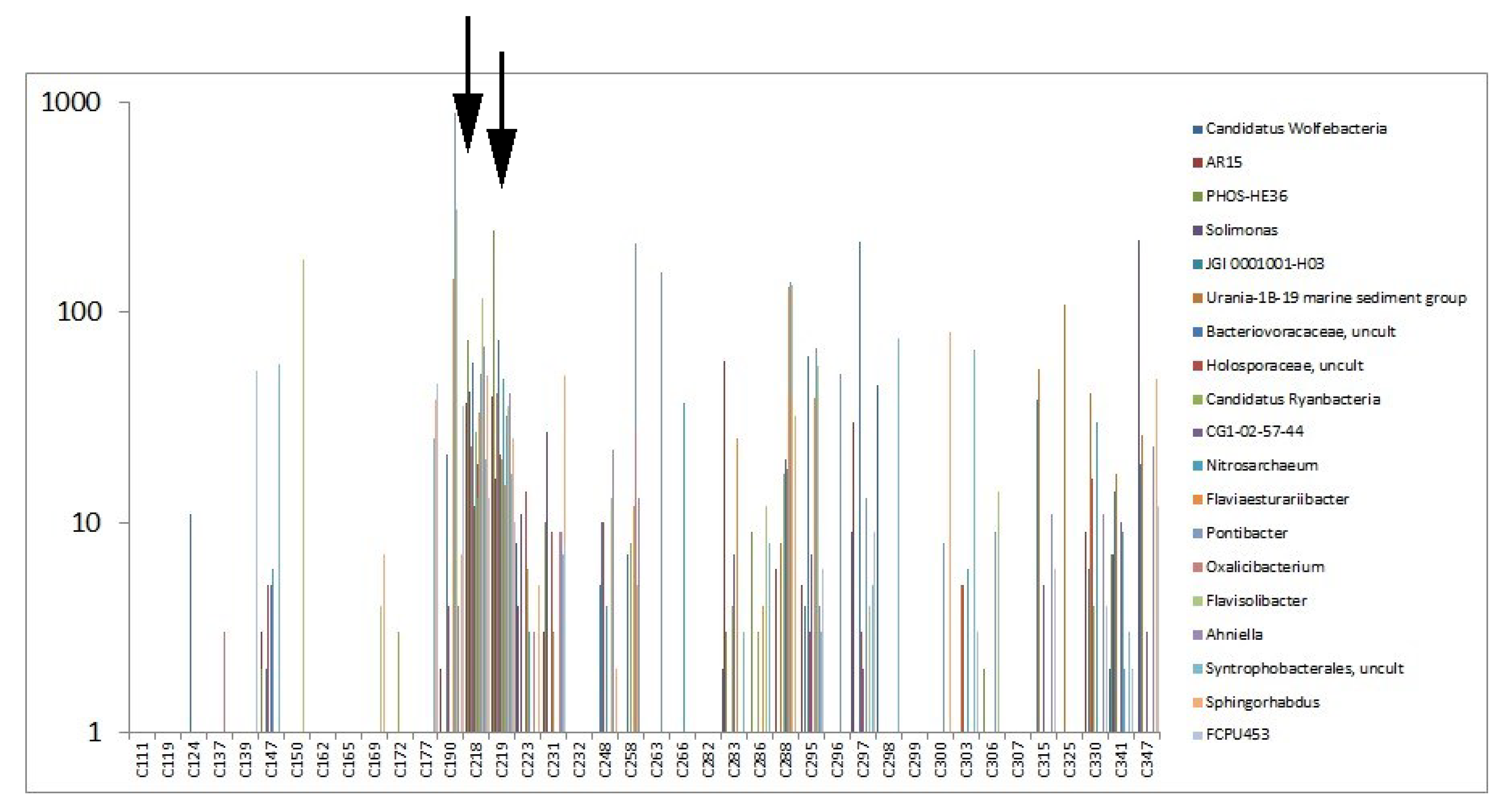

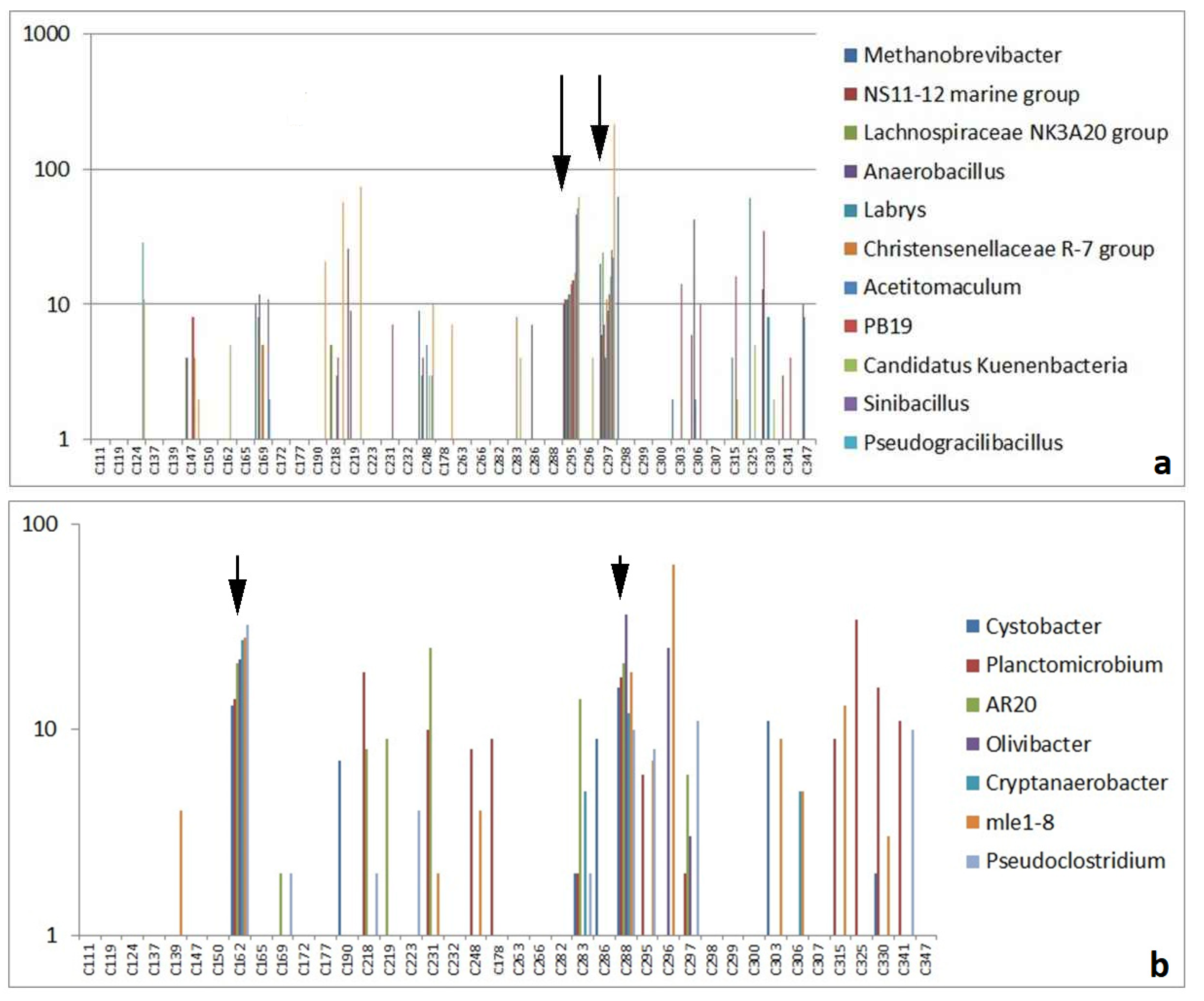

3.2.2. Highly Abundant Special Bacteria

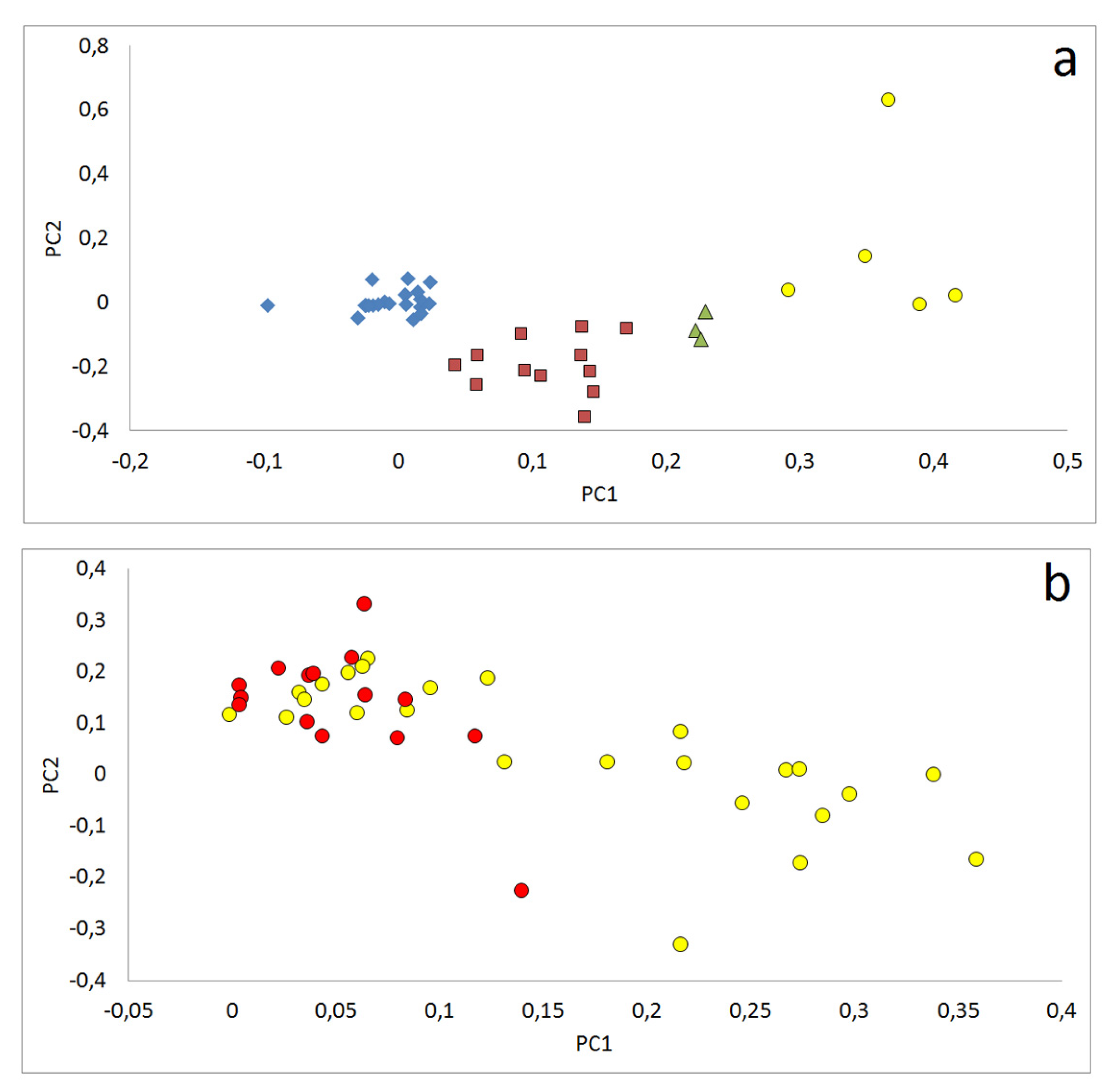

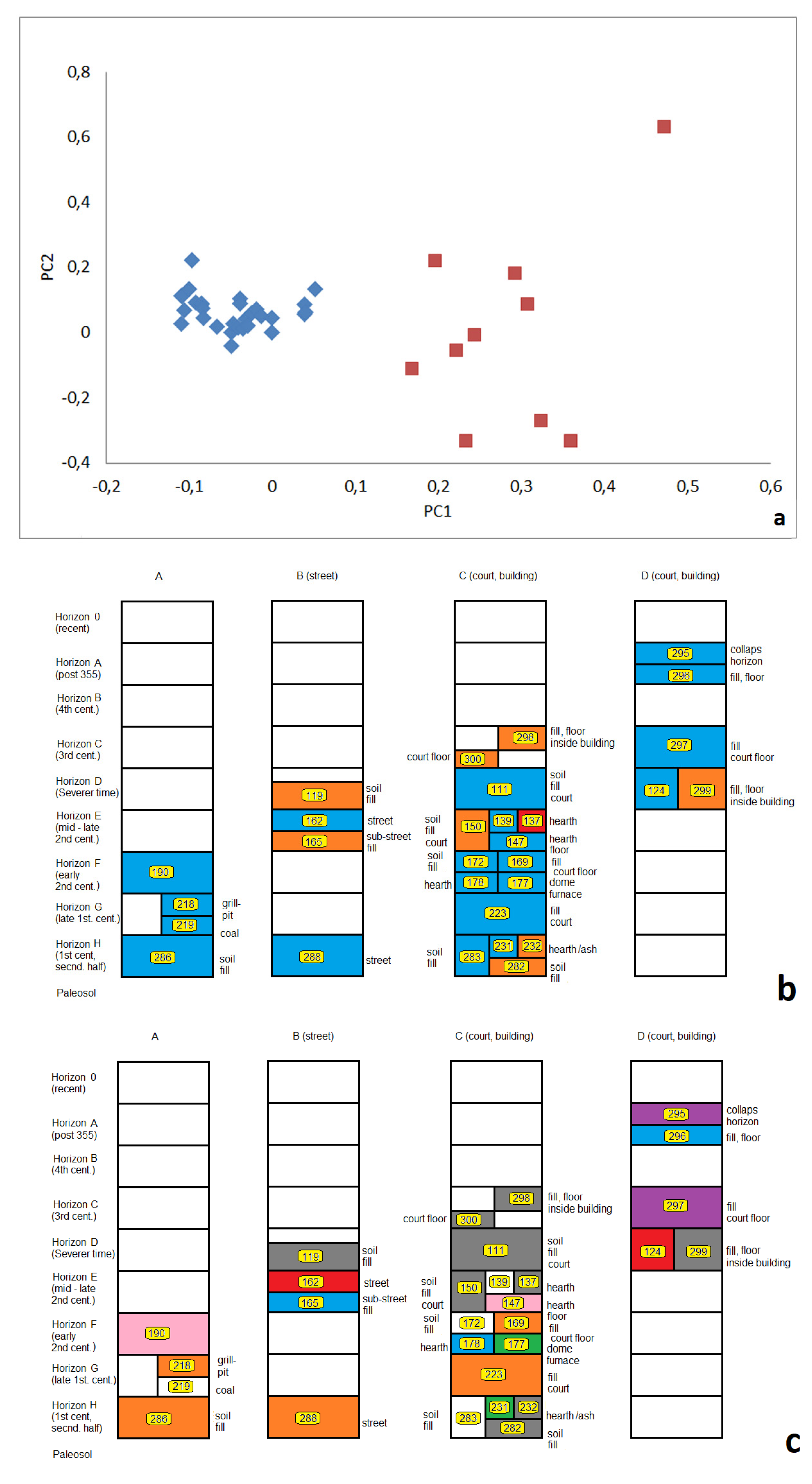

3.2.3. Relations between Samples Reflected by Principle Component Analyses (PCA)

3.3. Finger Print-like Abundance Patterns (FPP) and Relations between Samples

3.3.1. Close Neighbourhood

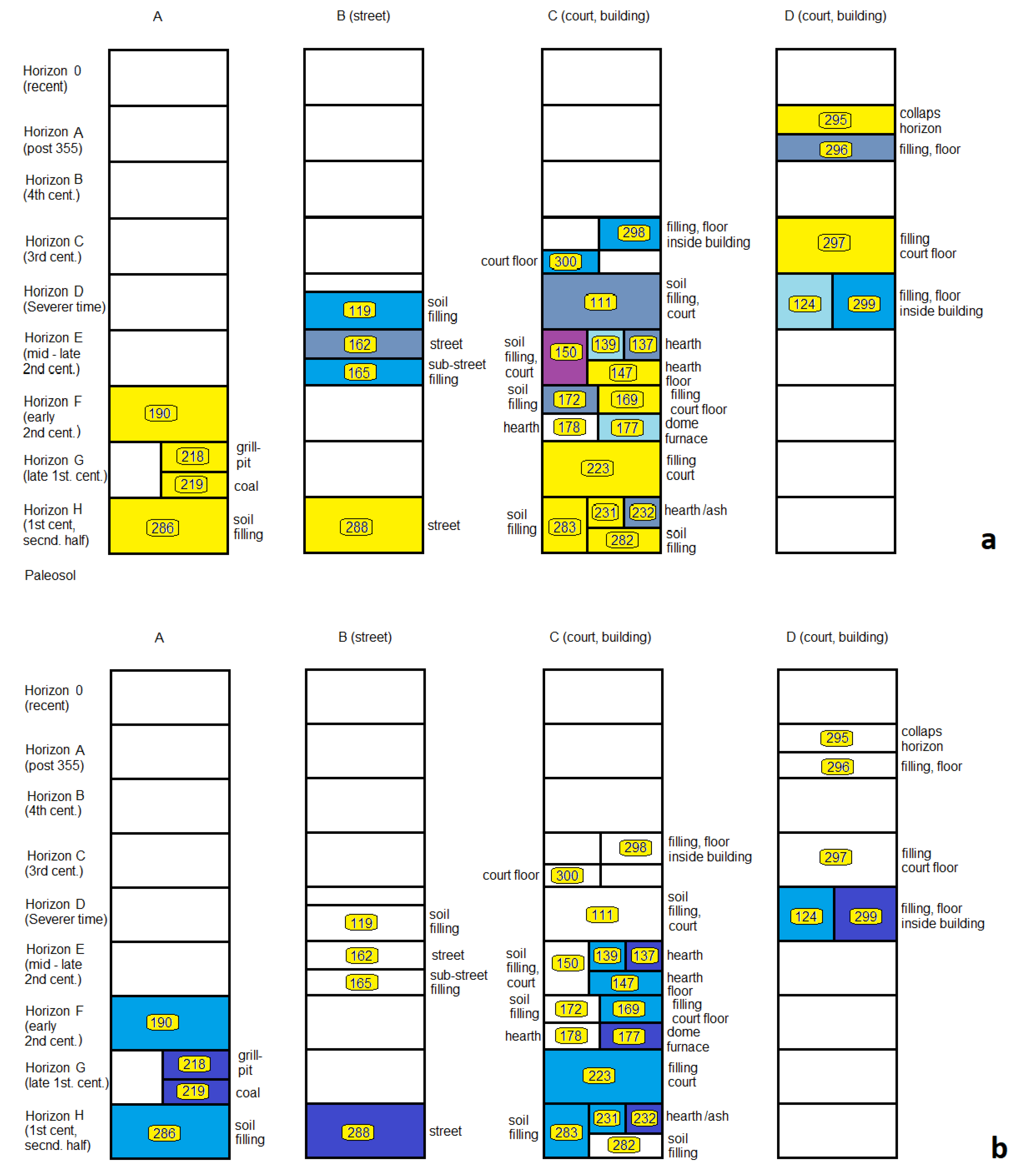

3.3.2. Stratigraphic Relations

3.3.3. Fill-Related Patterns

3.3.4. Fire- or Heat-Related Abundance Patterns

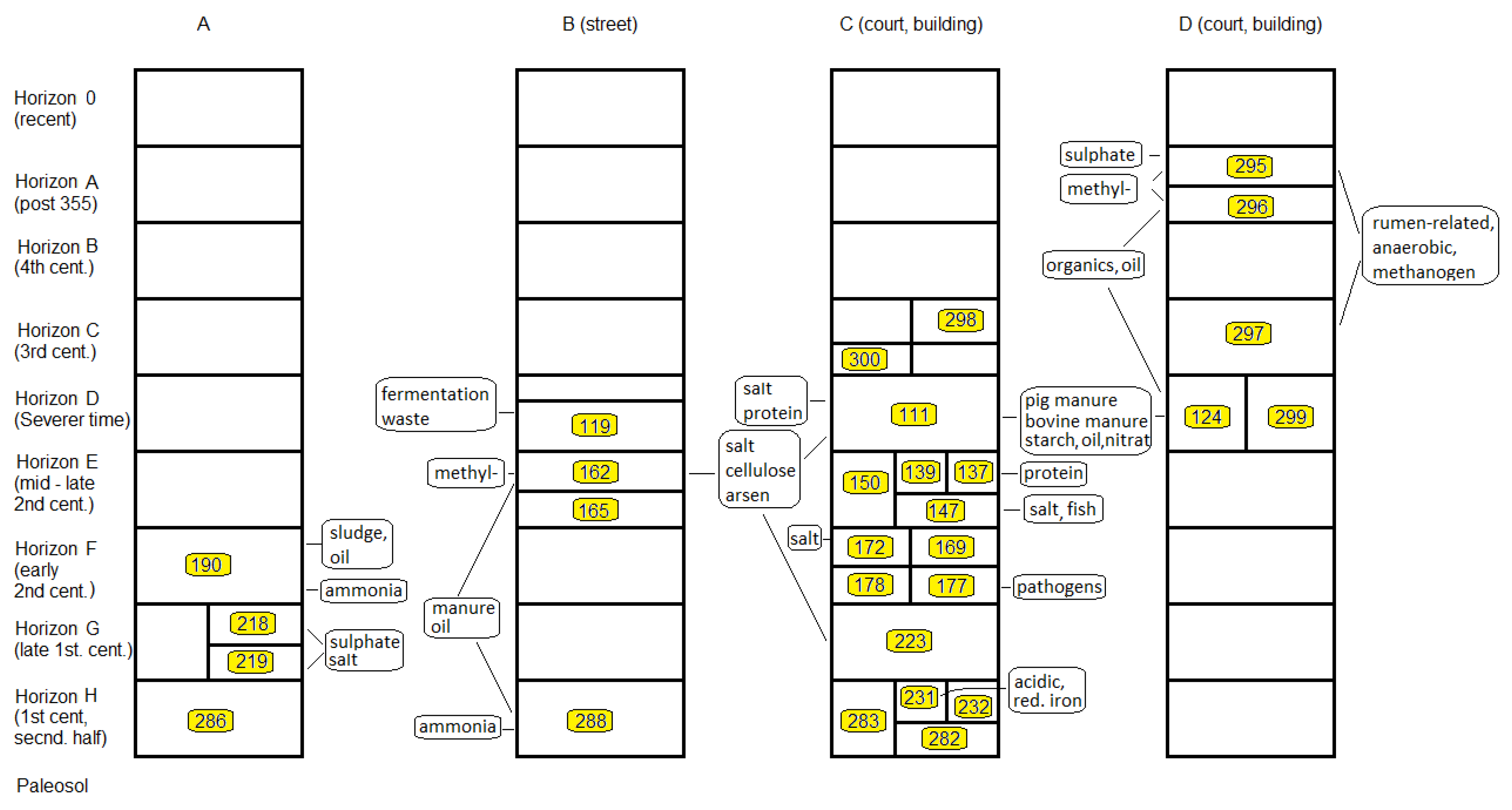

3.4. Local Distribution of OTUs on Excavation Site M08

4. OTU Patterns of Single Samples

5. Archaeological Interpretation

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warinner, Ch.; Herbig, A.; Mann, A.; Yates, J.A.F.; Weiß, C.L.; Burbano, H.A.; Orlando, L.; Krause, J. A robust framework for microbial archaeology. Ann. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 2017, 18, 321–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Philips, A.; Stolarek, I.; Kuczkowska, B.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of microorganisms accompanying human archaeological remains. GigaScience 2017, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsburgh, K.A.; Gosling, A.L.; Cochrane, E.E.; Kirch, P.V.; Swift, J.A.; McCoy, M.D. Origins of Polynesian pigs revealed by mitochrondrial whole genome ancient DNA. Animals 2022, 12, 2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chernysheva, E.; Korobov, D.; Borisov, A. Thermophilic microorganisms in arable land around medieval archaeological sites in Northern Caucasus, Russia: Novel evidence of past manuring practices. Geoarchaeol. Intern. J. 2017, 32, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallory, J.; Dybo, A.; Balanovsky, O. The impact of genetic research on archaeology and linguistics in Eurasia. Russian J. Genetics 2019, 55, 1472–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Brown, T. Agricultural origins: the evidence of modern and ancient DNA. Holocene 2000, 10, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabin, S.; Yeh, H.Y.; Pluskowski, A.; Clamer, C.; Mitchell, P.D. Bos, K.I. Estimating molecular preservation of the intestinal microbiome via metagenomics analyses of latrine sediments from two medieval cities. Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. B 2020, 375, 20190576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warinner, C. An archaeology of microbes. J. Anthropol. Res. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Romanowicz, K.J.; Freedman, Z.B.; Upchurch, R.A.; Argiroff, W.A.; Zak, D.R. Active microorganisms in forest soils differ from total community yet are shaped by the same environmental factors: the influence of pH and soil moisture. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2016, 92, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolinska, A.; Wlodarczyk, K.; Kuzniar, A.; Marzec-Grzadziel, A.; Grzadziel, J.; Galazka, A.; Uzarowicz, L. Soil microbial community profiling and bacterial metabolic activity of technosols as an effect of soil properties following land reclamation: a case study from abandoned iron sulphide and uranium mine in Rudki (south-central Poland). Agronomy 2020, 10, 1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsvik, V.; Sorheim, R.; Gokskoyr, J. Total bacterial diversity in soil and sediment – a review. J. Indust. Microbiol. 1996, 17, 170–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, M.W.; VanMoorsel, S.J.; Hahkl, T.; DeLuca, E.; DeDeyn, G.B.; Wagg, C.; Niklaus, P.A.; Schmid, B. Effects of plant community history, soil legacy and plant diversity on soil microbial communities. J. Ecology 2021, 109, 3007–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.E.; Lennon, J.T. Dormancy contributes to the maintenance of microbial diversity. PNAS 2010, 107, 5881–5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aanderud, Z.T.; Jones, S.E.; Fierer, N. 2015. Resuscitation of the rare biosphere contributes to pulses of ecosystem activity. Frontiers in Microbiology 2015, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. E Wegner, W. Liesack. Unexpected dominance of elusive acidobacteria in early industrial soft coal slags. Frontiers Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1023. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, D.; Herndon, E.; Zemanek, L.; Kortney, C.; Sander, T.; Senko, J.; Perdrial, N. Biogeochemical controls on the potential for long-term contaminated leaching from soils developing on historical coal mine spoil. Soil Syst. 2021, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margesin, R.; Siles, J.A.; Cajthaml, T.; Ohlinger, B.; Kistler, E. Microbiology meets archaeology: soil microbial communities reveal different human activities at archaic Monte Iato (Sixth century BC). Microbial Ecol. 2017, 73, 925–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.M; Kalensee, F.; Günther, P.M.; Schüler, T.; Cao, J. The local ecological memory of soil: majority and minority components of bacterial communities in prehistoric urns from Schöps (Germany). Int. J. Environ. Res. 2018, 12, 575–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.M.; Beetz, N.; Günther, P.M.; Möller, F.; Schüler, T.; Cao, J. Microbial community types and signature-like soil bacterial patterns from fortified prehistoric hills of Thuringia (Germany). Community Ecology 2020, 21, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhler, J.M.; Kalensee, F.; Cao, J.; Günther, P.M. Hadesarchaea and other extremophile bacteria from ancient mining areas of the East Harz region (Germany) suggest an ecological long-term memory of soil SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J.M. Köhler, L. Ehrhardt, J. Cao, F. Möller, T. Schüler, P.M. Günther. Beta-Diversity Enhancement by archaeological structures: bacterial communities of an historical tannery area of the city of Jena (Germany) reflected the ancient human impact. Ecologies 2023, 4, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfennia, O.E.; Ivanova, A.E.; Sacharov, D.S. The mycologicl properties of medieval cultur layers as a form of ‘soil biological memory’ about urbanization. J. Soils Sediments 2008, 8, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergacheva, M. Ecological function of soil humus. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2001, 34, 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- Khalighi, M; Gonze, D.; Faust, K.; Sommeria-Klein, G.; Lathi, L. Quantifiying the impact of ecological memory on the dynamics of interacting communities. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2022, 1009396.

- Benito, B.M.; Gil-Romera, G.; Birks, H.J.B. Ecological memory at millennial time-scales: the importance of data constraints, species longevity and niche features. Ecography 2019, 43, 04772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonze, D.; Coyte, K.; Lahti, L.; Faust, K. Microbial communities as dynamical system. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2018, 44, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogle, K.; Barber, J.J.; Baron-Gafford, G.A.; Benthley, L.P.; Young, J.; Huxman, T.E.; Loik, M.E.; Tissue, D.T. Quantifying ecological memory in plant and ecosystem processes. Ecol. Lett. 2015, 18, 221–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canarini, A.; Schmidt, H.; Fuchslueger, L.; Martin, V.; Herbold, C.W.; Zezula, D.; Gundler. Ph.; Hasibeder, R.; Jecmenia, M.; Bahn, M. et al. Ecological memory of recurrent drought modifies soil processes via changes in soil micribial community. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 25675–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvyaintsev, D.G.; Dobrovolskaya, T.G.; Babeya, I.P.; Zenova, G.M.; Lysak, L.V.; Marfennia, O.Y. Role of microorganisms in the biogeocenotic functions of soil. Eurasian Soil Sci. 1992, 24, 30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Borisov, A.V.; Demkina, T.S.; Kashirskaya, N.N.; Khomutova, T.E.; Chernysheva, E.V. Changes in the past soil-forming conditions and human activity in soil biological memory: microbial and enzyme components. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2021, 54, 1078–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, V. Alien invasiens, eclogical restoration in cities and the loss of ecological memory. Restoration Ecology 2009, 17, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konecny, A.; Fuchshuber, N.; Pollhammer, E. Grabungen in den canabae legions von Carnuntum. Acta Carnuntina 2022, 12/2, 22 –41. [Google Scholar]

- Humer, F (ed.). Carnuntum. Wiedergeborene Stadt der Kaiser, Darmstadt 2014: Philip von Zabern.

- Gassner, V.; Jilek, S.; Ladstätter, S. Am Rande des Reichs. Die Römer in Österreich, Vienna: Ueberreuter 2002.

- Kandler, M; Humer, F. Carnuntum, in: Šašel Kos, M.; Scherrer, P. (eds.), The autonomous towns of Noricum and Pannonia II, Noricum,2004, Situla 42, Ljubljana: Narodni Muzej Slovenije,11−66.

- Gersbach, E. Ausgrabung heute. Methoden und Techniken der Feldgrabung, 3rd ed., 1999 Stuttgart,Theiss.

- Harris, E. Principles of Archaeological Stratigraphy, 2nd ed., London: Academic Press 1989.

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; Peplies, J.; Glockner, F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D590–D596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klindworth, A.; Pruesse, E.; Schwee, T.; Peplies, J.; Quast, C.; Horn, M.; Glockner, F.O. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yilmaz, P.; Parfrey, L.-W.; Yarza, P.; Gerken, J.; Pruesse, E.; Quast, C.; Schweer, T.; Peplies, J.; Ludwig, W.; Glockner, F.O. The SILVA and “All-species Living Tree Project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acid Res. 2014, 42, D643–D648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, S.; Kämpfer, P.; Schleifer, K. H. Limnobacter thiooxidans gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel thiosulfate-oxidizing bacterium isolated from freshwater lake sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001, 51, 1463–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wu, W.-M.; Zhao, J.; Song, Y.; Gao, L.; Yang, R.; Jiang, L. Biodegradation and Mineralization of Polystyrene by Plastic-Eating Mealworms: Part 2. Role of Gut Microorganisms. Environmental science & technology 2015, 49, 12087–12093. [Google Scholar]

- Irgens, R. L.; Gosink, J. J.; Staley, J. T. Polaromonas vacuolata gen. nov., sp. nov., a psychrophilic, marine, gas vacuolate bacterium from Antarctica. International journal of systematic bacteriology 1996, 46, 822–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. M.; Kim, J. Limnobacter humi sp. nov., a thiosulfate-oxidizing, heterotrophic bacterium isolated from humus soil, and emended description of the genus Limnobacter Spring et al. 2001. Journal of microbiology (Seoul, Korea) 2017, 55, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eloe-Fadrosh, E. A.; Paez-Espino, D.; Jarett, J.; Dunfield, P. F.; Hedlund, B. P.; Dekas, A. E.; Grasby, S. E.; Brady, A. L.; Dong, H.; Briggs, B. R.; et al. Global metagenomic survey reveals a new bacterial candidate phylum in geothermal springs. Nature communications 2016, 7, 10476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. K.; Kim, Y.-J.; Cho, D.-H.; Yi, T.-H.; Soung, N.-K.; Yang, D.-C. Solimonas soli gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from soil of a ginseng field. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 2591–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baer, M. L.; Ravel, J.; Chun, J.; Hill, R. T.; Williams, H. N. A proposal for the reclassification of Bdellovibrio stolpii and Bdellovibrio starrii into a new genus, Bacteriovorax gen. nov. as Bacteriovorax stolpii comb. nov. and Bacteriovorax starrii comb. nov., respectively. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000, 50 Pt 1, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, M.-Y.; Islam, M. A.; Gwak, J.-H.; Kim, J.-G.; Rhee, S.-K. Nitrosarchaeum koreense gen. nov., sp. nov., an aerobic and mesophilic, ammonia-oxidizing archaeon member of the phylum Thaumarchaeota isolated from agricultural soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 3084–3095. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kang, J. Y.; Chun, J.; Seo, J.-W.; Kim, C. H.; Jahng, K. Y. Flaviaesturariibacter amylovorans gen. nov., sp. nov., a starch-hydrolysing bacterium, isolated from estuarine water. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2209–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedashkovskaya, O. I.; Kim, S. B.; Suzuki, M.; Shevchenko, L. S.; Lee, M. S.; Lee, K. H.; Park, M. S.; Frolova, G. M.; Oh, H. W.; Bae, K. S.; et al. Pontibacter actiniarum gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel member of the phylum ‘Bacteroidetes’, and proposal of Reichenbachiella gen. nov. as a replacement for the illegitimate prokaryotic generic name Reichenbachia Nedashkovskaya et al. 2003. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 2583–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamer, A. U.; Aragno, M.; Sahin, N. Isolation and characterization of a new type of aerobic, oxalic acid utilizing bacteria, and proposal of Oxalicibacterium flavum gen. nov., sp. nov. Systematic and applied microbiology 2002, 25, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, M.-H.; Im, W.T. Flavisolibacter ginsengterrae gen nov., sp. nov. And Flavisolibacter ginsengisoli sp. nov., isolated from ginseng cultivating soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 1834–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W. M.; Ko, Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Kang, K. Ahniella affigens gen. nov., sp. nov., a gammaproteobacterium isolated from sandy soil near a stream. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 2478–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogler, M.; Chen, H.; Simon, J.; Rohde, M.; Busse, H.-J.; Klenk, H.-P.; Tindall, B. J.; Overmann, J. Description of Sphingorhabdus planktonica gen. nov., sp. nov. and reclassification of three related members of the genus Sphingopyxis in the genus Sphingorhabdus gen. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 1342–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balch, W. E.; Fox, G. E.; Magrum, L. J.; Woese, C. R.; Wolfe, R. S. Methanogens: reevaluation of a unique biological group. Microbiological reviews 1979, 43, 260–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsodi, A. K.; Aszalós, J. M.; Bihari, P.; Nagy, I.; Schumann, P.; Spröer, C.; Kovács, A. L.; Bóka, K.; Dobosy, P.; Óvári, M.; et al. Anaerobacillus alkaliphilus sp. nov., a novel alkaliphilic and moderately halophilic bacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 69, 631–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasilyeva, L.V.; Semenov, A.M. Labrys monahos, a new buddng prosthecate bacterium with radial symmetry. Mikrobiologiya 1984, 53, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Greening, R. C.; Leedle, J. A. Enrichment and isolation of Acetitomaculum ruminis, gen. nov., sp. nov.: acetogenic bacteria from the bovine rumen. Archives of microbiology 1989, 151, 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Zhou, S. Sinibacillus soli gen. nov., sp. nov., a moderately thermotolerant member of the family Bacillaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 1647–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glaeser, S. P.; McInroy, J. A.; Busse, H.-J.; Kämpfer, P. Pseudogracilibacillus auburnensis gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from the rhizosphere of Zea mays. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2442–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntougias, S.; Fasseas, C.; Zervakis, G. I. Olivibacter sitiensis gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from alkaline olive-oil mill wastes in the region of Sitia, Crete. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 398–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juteau, P.; Côté, V.; Duckett, M.-F.; Beaudet, R.; Lépine, F.; Villemur, R.; Bisaillon, J.-G. Cryptanaerobacter phenolicus gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobe that transforms phenol into benzoate via 4-hydroxybenzoate. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tu, B.; Dai, L.-R.; Lawson, P. A.; Zheng, Z.-Z.; Liu, L.-Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, L. Petroclostridium xylanilyticum gen. nov., sp. nov., a xylan-degrading bacterium isolated from an oilfield, and reclassification of clostridial cluster III members into four novel genera in a new Hungateiclostridiaceae fam. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68, 3197–3211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämpfer, P.; Young, C.-C.; Arun, A. B.; Shen, F.-T.; Jäckel, U.; Rosselló-Mora, R.; Lai, W.-A.; Rekha, P. D. Pseudolabrys taiwanensis gen. nov., sp. nov., an alphaproteobacterium isolated from soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 2469–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.-L.; Xie, B.-S.; Cai, M.; Tang, Y.-Q.; Wang, Y.-N.; Cui, H.-L.; Liu, X.-Y.; Tan, Y.; Wu, X.-L. Halodurantibacterium flavum gen. nov., sp. nov., a non-phototrophic bacterium isolated from an oil production mixture. Current microbiology 2015, 70, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inahashi, Y.; Matsumoto, A.; Danbara, H.; Ōmura, S.; Takahashi, Y. Phytohabitans suffuscus gen. nov., sp. nov., an actinomycete of the family Micromonosporaceae isolated from plant roots. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 2652–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vandieken, V.; Niemann, H.; Engelen, B.; Cypionka, H. Marinisporobacter balticus gen. nov., sp. nov., Desulfosporosinus nitroreducens sp. nov. and Desulfosporosinus fructosivorans sp. nov., new spore-forming bacteria isolated from subsurface sediments of the Baltic Sea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 1887–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ventosa, A.; Marquez, M. C.; Ruiz-Berraquero, F.; Kocur, M. Salinicoccus roseus gen. nov., sp. nov., a new moderately halophilic gram-positive coccus. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1990, 13, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Rückert, C.; Li, G.; Huang, P.; Schneider, O.; Kalinowski, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zotchev, S. B.; Jiang, C. Prauserella flavalba sp. nov., a novel species of the genus Prauserella, isolated from alkaline soil. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2020, 70, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Kojima, H.; Fukui, M. Sulfuriferula multivorans gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from a freshwater lake, reclassification of ‘Thiobacillus plumbophilus’ as Sulfuriferula plumbophilus sp. nov., and description of Sulfuricellaceae fam. nov. and Sulfuricellales ord. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 1504–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, K.; Hiraishi, A.; Yoshimi, Y.; Kawaharasaki, M.; Masuda, K.; Kamagata, Y. Microlunatus phosphovorus gen. nov., sp. nov., a new gram-positive polyphosphate-accumulating bacterium isolated from activated sludge. International journal of systematic bacteriology 1995, 45, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, T.; Ve, N. B.; Kimoto, K.-I.; Iwabuchi, N.; Sumida, H.; Hasegawa, I.; Sasaki, S.; Tamura, T.; Kudo, T.; Suzuki, K.-I.; et al. Curtobacterium ammoniigenes sp. nov., an ammonia-producing bacterium isolated from plants inhabiting acidic swamps in actual acid sulfate soil areas of Vietnam. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 1447–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Du, Y.; Wang, G. Knoellia flava sp. nov., isolated from pig manure. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2012, 62, 384–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinero, N.; Conti, E.; Sánchez, B.; Walker, A. W.; Margolles, A.; Duncan, S. H.; Delgado, S. Ruminococcoides bili gen. nov., sp. nov., a bile-resistant bacterium from human bile with autolytic behavior. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2021, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.; Nguyen, S. V.; Connor, M.; Fairley, D. J.; Donoghue, O.; Marshall, H.; Koolman, L.; McMullan, G.; Schaffer, K. E.; McGrath, J. W.; et al. Terrisporobacter hibernicus sp. nov., isolated from bovine faeces in Northern Ireland. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2023, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Guo, X.; Wang, Y.; He, M.; Ma, K.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Kong, D.; Yang, Z.; Ruan, Z. Terrisporobacter petrolearius sp. nov., isolated from an oilfield petroleum reservoir. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 3522–3526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortina, M. G.; Pukall, R.; Schumann, P.; Mora, D.; Parini, C.; Manachini, P. L.; Stackebrandt, E. Ureibacillus gen. nov., a new genus to accommodate Bacillus thermosphaericus (Andersson et al. 1995), emendation of Ureibacillus thermosphaericus and description of Ureibacillus terrenus sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001, 51, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fraj, B.; Ben Hania, W.; Postec, A.; Hamdi, M.; Ollivier, B.; Fardeau, M.-L. Fonticella tunisiensis gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from a hot spring. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 1947–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koeck, D. E.; Ludwig, W.; Wanner, G.; Zverlov, V. V.; Liebl, W.; Schwarz, W. H. Herbinix hemicellulosilytica gen. nov., sp. nov., a thermophilic cellulose-degrading bacterium isolated from a thermophilic biogas reactor. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2365–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antunes, A.; Rainey, F. A.; Wanner, G.; Taborda, M.; Pätzold, J.; Nobre, M. F.; da Costa, M. S.; Huber, R. A new lineage of halophilic, wall-less, contractile bacteria from a brine-filled deep of the Red Sea. Journal of bacteriology 2008, 190, 3580–3587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyuzhnaya, M. G.; Bowerman, S.; Lara, J. C.; Lidstrom, M. E.; Chistoserdova, L. Methylotenera mobilis gen. nov., sp. nov., an obligately methylamine-utilizing bacterium within the family Methylophilaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 2819–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Zhou, L.; Zeng, X.-C.; Liu, L.; Pan, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Li, S.; Li, W.-J.; Wang, Y. Arsenicitalea aurantiaca gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the family Hyphomicrobiaceae, isolated from high-arsenic sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 5478–5484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.V. Simankova, M.V.; Chernych, N.A.; Osipov, G.A.; Zavarzin, G.A. Halocella cellulolytica gen. nov., sp. nov., a New Obligately Anaerobic, Halophilic, Cellulolytic bacterium Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 1993, 16, 385–389. [Google Scholar]

- Mechichi, T.; Stackebrandt, E.; Fuchs, G. Alicycliphilus denitrificans gen. nov., sp. nov., a cyclohexanol-degrading, nitrate-reducing beta-proteobacterium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 8Watanabe, M.; Kojima, H.; Fukui, M. Limnochorda pilosa gen. nov., sp. nov., a moderately thermophilic, facultatively anaerobic, pleomorphic bacterium and proposal of Limnochordaceae fam. nov., Limnochordales ord. nov. and Limnochordia classis nov. in the phylum Firmicutes. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2378–2384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatayama, K.; Shoun, H.; Ueda, Y.; Nakamura, A. Planifilum fimeticola gen. nov., sp. nov. and Planifilum fulgidum sp. nov., novel members of the family ‘Thermoactinomycetaceae’ isolated from compost. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 2101–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, A.; Busse, J.; Goor, M.; Pot, B.; Falsen, E.; Jantzen, E.; Hoste, B. ; Gillis,, M.;Kersters, K.; Auling, G.; De Ley, J. Hydrogenophaga, a New Genus of Hydrogen-Oxidizing Bacteria That Includes Hydrogenophaga flava comb. nov. (Formerly Pseudomonas flava), Hydrogenophaga palleronii (Formerly Pseudomonas palleronii), Hydrogenophaga pseudoflava (Formerly Pseudomonas pseudoflava and “Pseudomonas carboxy do flava”), and Hydrogenophaga taeniospiralis (Formerly Pseudomonas taeniospiralis). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 1989, 39, 319–332. [Google Scholar]

- Castelle, C.J.; Hug, L.A.; Wrighton, K.C.; Thomas, B.C.; Williams, K.H.; Wu, D.; Tringe, S.G.; Singer, S.W.; Eisen, J.A.; Banfield, J.F. Extraordinary phylogenetic diversity and metabolic versatility in aquifer sediment. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, J.; Wang, J.; Dai, H.-Q.; Zhang, Z.-D.; Tang, Q.-Y.; Ren, B.; Yang, N.; Goodfellow, M.; Zhang, L.-X.; Liu, Z.-H. Yuhushiella deserti gen. nov., sp. nov., a new member of the suborder Pseudonocardineae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2011, 61, 621–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, K.; Zong, R.; Li, Q.; Fu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, N. Oceaniovalibus guishaninsula gen. nov., sp. nov., a marine bacterium of the family Rhodobacteraceae. Current microbiology 2012, 64, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.-C.; Margesin, R. Gelidibacter sediminis sp. nov., isolated from a sediment sample of the Yellow Sea. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 2304–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Dong, X. Proteiniphilum acetatigenes gen. nov., sp. nov., from a UASB reactor treating brewery wastewater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksiezarek, M.; Ribeiro, T. G.; Rocha, J.; Grosso, F.; Perovic, S. U.; Peixe, L. Limosilactobacillus urinaemulieris sp. nov. and Limosilactobacillus portuensis sp. nov. isolated from urine of healthy women. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2019, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Niu, L.; Zhang, Y. Saccharofermentans acetigenes gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobic bacterium isolated from sludge treating brewery wastewater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 2735–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takii, S.; Hanada, S.; Tamaki, H.; Ueno, Y.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Ibe, A.; Matsuura, K. Dethiosulfatibacter aminovorans gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel thiosulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from coastal marine sediment via sulfate-reducing enrichment with Casamino acids. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 2320–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, A. L.; Albuquerque, L.; Tiago, I.; Nobre, M. F.; Empadinhas, N.; Veríssimo, A.; da Costa, M. S. Meiothermus timidus sp. nov., a new slightly thermophilic yellow-pigmented species. FEMS microbiology letters 2005, 245, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garnova, E.S.; Zhilina, T.N.; Tourova, T.P.; Kostrikina, N.A.; Zavarzin, G.A. Anaerobic, alkaliphilic, saccharolytic bacterium Alkalibacter saccharofermentans gen. nov., sp. nov. from a soda lake in the Transbaikal region of Russia. Extremophiles: life under extreme conditions. 2004, 8, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, D.; Ueki, A.; Katsuji, A.; Ueki, K. Desulfobulbus japonicus sp. nov., a novel Gram-negative propionate-oxidizing, sulfate-reducing bacterium isolated from an estuarine sediment in Japan. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007, 57(Issue 4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ley, J.; Segers, P.; Gillis, M. Intra- and intergeneric similarities of Chromobacterium and Janthinobacterium ribosomal ribonucleic acid cistrons. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology 1978, 28, 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, D. J.; Woese, C. R.; MacDonell, M. T.; Colwell, R. R. Systematic study of the genus Vogesella gen. nov. and its type species, Vogesella indigofera comb. nov. International journal of systematic bacteriology 1997, 47, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mang, S. M.; Frisullo, S.; Elshafie, H. S.; Camele, I. Diversity Evaluation of Xylella fastidiosa from Infected Olive Trees in Apulia (Southern Italy). The Plant Pathology Journal 2016, 32, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, M. D.; Lawson, P. A. The genus Abiotrophia (Kawamura et al.) is not monophyletic: proposal of Granulicatella gen. nov., Granulicatella adiacens comb. nov., Granulicatella elegans comb. nov. and Granulicatella balaenopterae comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2000, 50, 365–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, E. A.; Devereux, R.; Maki, J. S.; Gilmour, C. C.; Woese, C. R.; Mandelco, L.; Schauder, R.; Remsen, C. C.; Mitchell, R. Characterization of a new thermophilic sulfate-reducing bacterium Thermodesulfovibrio yellowstonii, gen. nov. and sp. nov.: its phylogenetic relationship to Thermodesulfobacterium commune and their origins deep within the bacterial domain. Archives of microbiology 1994, 161, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, N.; Lee, S. H.; Jin, H. M.; Jung, J. Y.; Schumann, P.; Jeon, C. O. Garicola koreensis gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from saeu-jeot, traditional Korean fermented shrimp. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2015, 65, 1015–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomila, M.; Pinhassi, J.; Falsen, E.; Moore, E. R. B.; Lalucat, J. Kinneretia asaccharophila gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from a freshwater lake, a member of the Rubrivivax branch of the family Comamonadaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Toyonaga, M.; Ohashi, A.; Matsuura, N.; Tourlousse, D. M.; Meng, X.-Y.; Tamaki, H.; Hanada, S.; Cruz, R.; Yamaguchi, T.; et al. Isolation and characterization of Flexilinea flocculi gen. nov., sp. nov., a filamentous, anaerobic bacterium belonging to the class Anaerolineae in the phylum Chloroflexi. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 988–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsubouchi, T.; Shimane, Y.; Mori, K.; Usui, K.; Hiraki, T.; Tame, A.; Uematsu, K.; Maruyama, T.; Hatada, Y. Polycladomyces abyssicola gen. nov., sp. nov., a thermophilic filamentous bacterium isolated from hemipelagic sediment. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 1972–1981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, H.; Schumann, P.; Chun, J. Demequina aestuarii gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel actinomycete of the suborder Micrococcineae, and reclassification of Cellulomonas fermentans Bagnara et al. 1985 as Actinotalea fermentans gen. nov., comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, T. D.; Lawson, P. A.; Collins, M. D.; Falsen, E.; Tanner, R. S. Cloacibacterium normanense gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel bacterium in the family Flavobacteriaceae isolated from municipal wastewater. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 1311–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.-J.; Wagner, I. D.; Brice, M. E.; Kevbrin, V. V.; Mills, G. L.; Romanek, C. S.; Wiegel, J. Thermosediminibacter oceani gen. nov., sp. nov. and Thermosediminibacter litoriperuensis sp. nov., new anaerobic thermophilic bacteria isolated from Peru Margin. Extremophiles : life under extreme conditions 2005, 9, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoozegar, M. A.; Bagheri, M.; Didari, M.; Shahzedeh Fazeli, S. A.; Schumann, P.; Sánchez-Porro, C.; Ventosa, A. Saliterribacillus persicus gen. nov., sp. nov., a moderately halophilic bacterium isolated from a hypersaline lake. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2013, 63, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.-S.; Im, W.-T.; Yang, H.-C.; Lee, S.-T. Shinella granuli gen. nov., sp. nov., and proposal of the reclassification of Zoogloea ramigera ATCC 19623 as Shinella zoogloeoides sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, H.D. Proposal of Ancylobacter gen. nov. as a Substitute for the Bacterial Genus Microcyclus Ørskov 1928, Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol 1983, 33, 397–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deming, J. W.; Somers, L. K.; Straube, W. L.; Swartz, D. G.; MacDonald, M. T. Isolation of an obligately barophilic bacterium and description of a new genus, Colwellia gen. nov. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 1988, 1, 1,152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, L.K.; Reid, R.P.; Dupraz, C.; Decho, A.W; Buckley, D.H. J.R.; Spear, K.M. Przekop, P.T. Visscher: Sulfate reducing bacteria in microbial mats: Changing paradigms, new discoveries. Sedimentary Geology 2006, 185, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utkin, I.; Woese, C.; Wiegel, J. Isolation and characterization of Desulfitobacterium dehalogenans gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobic bacterium which reductively dechlorinates chlorophenolic compounds. International journal of systematic bacteriology 1994, 44, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, L. A.; Rinna, J.; Humphreys, G.; Weightman, A. J.; Fry, J. C. Fluviicola taffensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel freshwater bacterium of the family Cryomorphaceae in the phylum ‘Bacteroidetes’. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 2189–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romanenko, L. A.; Schumann, P.; Zhukova, N. V.; Rohde, M.; Mikhailov, V. V.; Stackebrandt, E. Oceanisphaera litoralis gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel halophilic bacterium from marine bottom sediments. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 1885–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foesel, B. U.; Mayer, S.; Luckner, M.; Wanner, G.; Rohde, M.; Overmann, J. Occallatibacter riparius gen. nov., sp. nov. and Occallatibacter savannae sp. nov., acidobacteria isolated from Namibian soils, and emended description of the family Acidobacteriaceae. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, A. F.; Hupfer, H.; Klenk, H.-P.; Siering, C. Desmospora activa gen. nov., sp. nov., a thermoactinomycete isolated from sputum of a patient with suspected pulmonary tuberculosis, and emended description of the family Thermoactinomycetaceae Matsuo et al. 2006. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 454–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Ishikawa, S.; Kasai, H.; Yokota, A. Persicitalea jodogahamensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a marine bacterium of the family ‘Flexibacteraceae’, isolated from seawater in Japan. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2007, 57, 1014–1017.77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, D.H.; Ismail, N.; Olano, J.P.; McBride, J.W.; Yu, X.-J.; Feng, H.-M. Ehrlichia chaffeensis: a prevalent, life-threatening, emerging pathogen. Trans. Am. Clin. Climatol. Assoc. 2004, 115, 375–82, discussion 382-4. [Google Scholar]

- Im, W.-T.; Yokota, A.; Kim, M.-K.; Lee, S.-T. Kaistia adipata gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel alpha-proteobacterium. The Journal of general and applied microbiology 2004, 50, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, G. S. N.; Nagy, M.; Garcia-Pichel, F. Belnapia moabensis gen. nov., sp. nov., an alphaproteobacterium from biological soil crusts in the Colorado Plateau, USA. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2006, 56, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishijima, M.; Tazato, N.; Handa, Y.; Umekawa, N.; Kigawa, R.; Sano, C.; Sugiyama, J. Krasilnikoviella muralis gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of the family Promicromonosporaceae, isolated from the Takamatsuzuka Tumulus stone chamber interior and reclassification of Promicromonospora flava as Krasilnikoviella flava comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2017, 67, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.-L.; Tian, Q.; Zhang, J.; Yuan, X.-Z.; Shi, X.-S.; Guo, R.-B.; Qiu, Y.-L. Acetobacteroides hydrogenigenes gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobic hydrogen-producing bacterium in the family Rikenellaceae isolated from a reed swamp. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2986–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezaki, T.; Kawamura, Y.; Li, N.; Li, Z. Y.; Zhao, L.; Shu, S. Proposal of the genera Anaerococcus gen. nov., Peptoniphilus gen. nov. and Gallicola gen. nov. for members of the genus Peptostreptococcus. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2001, 51, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, J. P.; Nichols, C. M.; Gibson, J. A. E. Algoriphagus ratkowskyi gen. nov., sp. nov., Brumimicrobium glaciale gen. nov., sp. nov., Cryomorpha ignava gen. nov., sp. nov. and Crocinitomix catalasitica gen. nov., sp. nov., novel flavobacteria isolated from various polar habitats. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2003, 53, 1343–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, K. K.; Lee, H.-S.; Yang, S. H.; Kim, S.-J. Kordiimonas gwangyangensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a marine bacterium isolated from marine sediments that forms a distinct phyletic lineage (Kordiimonadales ord. nov.) in the ‘Alphaproteobacteria’. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2005, 55, 2033–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulichevskaya, I. S.; Danilova, O. V.; Tereshina, V. M.; Kevbrin, V. V.; Dedysh, S. N. Descriptions of Roseiarcus fermentans gen. nov., sp. nov., a bacteriochlorophyll a-containing fermentative bacterium related phylogenetically to alphaproteobacterial methanotrophs, and of the family Roseiarcaceae fam. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2558–2565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerst, J. A.; Hawkins, J. A.; Holmes, A.; Sly, L. I.; Moore, C. J.; Stackebrandt, E. Porphyrobacter neustonensis gen. nov., sp. nov., an aerobic bacteriochlorophyll-synthesizing budding bacterium from fresh water. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology 1993, 43, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberreich, M.; Steinhoff-Knopp, B.; Burkhard, B.; Kleemann, J. The research gap between soil biodiversity and soil-related cultural ecosystem services. Soil Systems 2024, 8, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-X.; Qin, Y.; Chen, T.; Lu, M.; Qian, X.; Guo, X.; Bai, Y. A practical guide to amplicon and metagenomic analysis of microbiome data. Protein and Cell 2021, 12, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).