Submitted:

28 September 2024

Posted:

30 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature

2.1. Positive Effects

2.1.1. Improving Efficiency

2.1.2. Improves Stability

2.2. Negative Effects

2.2.1. Active Impact

2.2.2. Passive Impact

2.3. Hypothesis

3. Methodology

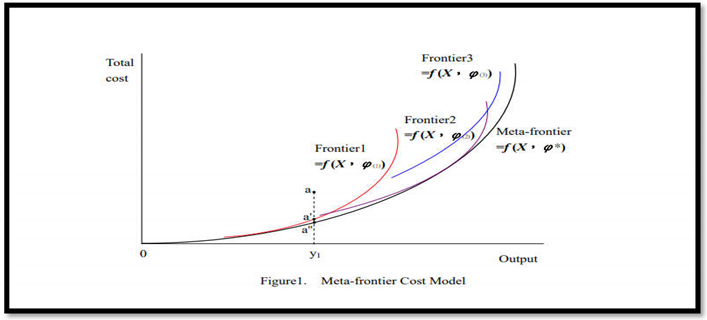

3.1. Modeling

3.2. The Efficiency Score and the Technology Gap Ratio "TGR"

where (Ln CT) is the natural logarithm of the total cost of the bth bank in the period t, (Ln wi bt) is the natural logarithm of its ith input prices, (Ln yk) represents the natural logarithm of its kth output, (Ln F) denotes its capitalization ratio used to control observable heterogeneity among banks.

where (Ln CT) is the natural logarithm of the total cost of the bth bank in the period t, (Ln wi bt) is the natural logarithm of its ith input prices, (Ln yk) represents the natural logarithm of its kth output, (Ln F) denotes its capitalization ratio used to control observable heterogeneity among banks.3.3. Sample and Database

4. Results

4.1. Variable Concentration "Conc"

4.2. The Variable Presence of Foreign Banks "Presence":

4.3. Variable Financial Disintermediation "Disinter," Actual Interest Rate "RealInterate" and Economic Development "GDP per Capita":

4.4. Effects of Specific Variables to Banks on Their Efficiency Levels

4.4.1. Other Non-Performing Assets "OtherNProAssets"

4.4.2. The Variable Net Loans/Total Assets "Net Loans) in%":

4.4.3. The Variable "Income Ratio (Coeffiexplo)":

4.5. Interaction Terms:

5. Conclusions

Appendix A

| Number of domestic and foreign banks in domestic banking sector | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continent | countries | Total Number of Commercial Banks* | Number of Domestic Banks** | Number of Foreign Banks*** |

| Argentina | 98 | 80 | 18 | |

| Bolivia | 16 | 14 | 2 | |

| Brazil | 159 | 130 | 29 | |

| Chile | 34 | 25 | 9 | |

| Colombia | 30 | 24 | 6 | |

| Latin America | Costa Rica | 27 | 26 | 1 |

| (13 countries) | Écuador | 40 | 39 | 1 |

| Jamaica | 12 | 9 | 3 | |

| Mexico | 40 | 25 | 15 | |

| Paraguay | 27 | 21 | 6 | |

| Peru | 27 | 20 | 7 | |

| Uruguay | 21 | 9 | 12 | |

| Venezuela | 46 | 41 | 5 | |

| Algeria | 6 | 5 | 1 | |

| Botswana | 6 | 1 | 5 | |

| Africa | Egypt | 30 | 23 | 7 |

| (8 countries) | Marocco | 13 | 9 | 4 |

| Nigeria | 46 | 42 | 4 | |

| South Africa | 33 | 26 | 7 | |

| Tunisia | 12 | 7 | 5 | |

| Zimbabwe | 9 | 5 | 4 | |

| Armenia | 7 | 6 | 1 | |

| Austria | 33 | 22 | 11 | |

| Bulgaria | 18 | 12 | 6 | |

| Croatia | 40 | 28 | 12 | |

| Cyrus | 17 | 12 | 5 | |

| Estonia | 8 | 5 | 3 | |

| Hungary | 34 | 10 | 24 | |

| Latvia | 25 | 18 | 7 | |

| Lithuania | 15 | 7 | 8 | |

| Malta | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| Europe | Polond | 59 | 23 | 36 |

| (16 countries) | Russia | 112 | 103 | 9 |

| Slovakia | 21 | 14 | 7 | |

| Slovenia | 23 | 20 | 3 | |

| Turkey | 61 | 59 | 2 | |

| Ukraine | 38 | 32 | 6 | |

|

Asia (17 countries) |

Bahrain | 9 | 5 | 4 |

| China | 41 | 39 | 2 | |

| India | 63 | 60 | 3 | |

| Indonesia | 105 | 82 | 23 | |

| Jordan | 11 | 9 | 2 | |

| Lebanon | 70 | 55 | 15 | |

| Malaysia | 52 | 40 | 12 | |

| Nepal | 9 | 7 | 2 | |

| Pakistan | 23 | 23 | 0 | |

| Philippines | 41 | 34 | 7 | |

| Qatar | 5 | 5 | 0 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 10 | 7 | 3 | |

| Singapore | 21 | 16 | 5 | |

| South Korea | 53 | 49 | 4 | |

| Syria | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Thailand | 16 | 10 | 6 | |

| Vietnam | 16 | 15 | 1 | |

References

- Abut D., S. Bigio et D.A. Siller, 1999. The independent local bank in Latin America. Goldman Sachs Investment Research. November 23.

- Agénor P., 2001. Benefits and costs of international financial integration: Theory and Facts. Paper prepared for the conference on Financial Globalization: Issues and Challenges for Small States (Saint Kitts, March 27-28, 2001), organized by the Word Bank Institute in collaboration with the Malta Institute for Small States and the Eastern Caribbean Central Bank.

- Angbazo L.,1997. Commercial bank net interest margins, default risk, interest-rate risk, and off-balance sheet banking. Journal of Banking and Finance, (21), pp 55-87.

- Atkinson S.E., et C. Cornwell, 1993. Measuring technical efficiency with panel data: A dual approach. Journal of Econometrics 59, pp 257-261. [CrossRef]

- Aziz I., W. Bailey, C.X. Mao, F. Siddik et W. Thorbecke, 2002. Firm behavior, economic vulnerability, and the credit crunch: an analysis of micro-macro interactions, mimeo. Asian Development Bank Institute.

- Barajas A, R. Steiner, et N. Salazar, 2000. The impact of liberalization and foreign investment in Colombia’s financial sector, Journal of Development Economics, Vol 63, pp 157–196. [CrossRef]

- Barth J. R, G. Caprio et R. Levine, 2001. The regulation and supervision of banks around the world a new data base, The world banks.

- Berger A. N., et R. DeYoung, 2001. The effects of geographic expansion on bank efficiency, Journal of Financial Services Research, Vol 19, N° 2-3, pp 163-184. [CrossRef]

- Berger A.N., et R. Deyoung, 1997. Problem loans and cost efficiency in commercial banks, Journal of Banking and Finance 21 N 6, pp 849-870.

- Berger A.N., et T.H. Hannan, 1998. The Efficiency cost of market power in the banking industry: A test of the « Quiet Life » and related hypotheses, The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol 80, No.3, pp 454-465. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya J., 1993. The role of foreign banks in developing countries: A survey of evidence, Unpublished manuscript, Cornell University.

- Bonaccorsi di Patti E., et D.C. Hardy, 2005. Financial sector liberalization, bank privatization, and efficiency: Evidence from Pakistan, Journal of Banking & Finance 29, pp 2381–2406. [CrossRef]

- Bosco M.G., 2003. Are foreign banks more efficient than domestic banks? An empirical study of transition and MED countries, Proceedings of the Global economic Modelling Network, International Conference on Policy Modelling, July 2003.

- Buch C.M., 1997. Opening up for foreign banks: how central and Eastern Europe can benefit, Economics of Transition, Vol 5 (2), pp 339-366. [CrossRef]

- Cao M., et S. Shi, 2000. Screening, bidding, and the loan market, Queen S. University, mimeo.

- Chantapong S., 2003. Comparative study of domestic and foreign bank performance in Thailand: The regression Analysis, Economic Change and Restructuring, Vol 38, N° 1, pp 63-83. [CrossRef]

- Claessens S., A. Demirgüç-Kunt et H. Huizinga, 2001. How does foreign entry affect the domestic banking market? Journal of Banking and Finance 25, pp 891-911.

- Claessens S., et M. Jansen, 2000. The internationalization of financial services: Issues and lessons for developing countries: overview, In The internationalization of financial services: issues and lessons for developing countries, Kluwer law international, The Hague.

- Claessens S., et T. Glaessner, 1999. Internationalization of financial services in Asia In Hanson, J. and S. Kathuria (eds.), India: A Financial Sector For the Twenty-First Century. Washington, D.C.: World Bank, New York, Oxford University Press.

- Clarke G., R. Cull, L. D’Amato et A. Molinari, 1999. The effect of foreign entry on Argentina’s domestic banking sector, The World Bank Series: Policy Research Working Paper Series Number 2158.

- Clarke G., R. Cull, M. Martinez Peria et S.M. Sanchez, 2001. Foreign bank entry: experience, implication for developing countries, and agenda for further research, The World Bank in its series, Policy Research Working Paper Series, N° 2698.

- CNB, 1998. Banking supervision in the Czech Republic, Czech National Bank, Prague.

- Crystal J.S, G.B. Dages et L.S. Goldberg, 2002. Has foreign bank entry led to sounder banks in Latin America, Current Issues in Economics and Finance, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, V 8, N° 1, pp 1-6.

- Daniel Ofori-Sasu, L. Mensah, J.K. Akuma et| I. Doku 2019. Banking efficiency in emerging economies: Does foreign banks entry matter in the Ghanaian context? International Journal of Finance & Economics, vol 24, Issue 3, pp 1091-1108. [CrossRef]

- Dell’Ariccia G., 2000. Learning by lending, competition, and screening incentives in the banking industry, International Monetary Fund, mimeo.

- Demirguç-Kunt A., et H. Huizinga, 1999. Determinants of commercial bank interest margins and profitability: some international evidence, The World Bank Economic Review, vol. 13, Nº 2, pp 379-408. [CrossRef]

- Demirgüç-Kunt A., R. Levine et H.G. Min 1998. Opening to foreign banks: issues of stability, efficiency, and growth, In Proceedings of the Bank of Korea Conference on the Implications of Globalization of World Financial Markets, pp 83-105.

- Demsetz H., 1973. Industry structure, market rivalry, and public policy, Journal of Law and Economics, 16, pp 1-9.

- Denizer C., 1999. Foreign entry in Turkeys banking sector, 1980–1997 The World Bank.

- Detragiache E. et P. Gupta, 2004. Foreign banks in emerging market crises: Evidence from Malaysia, IMF Working Paper.

- Detragiache E., T. Tressel, et P. Gupta, 2006. Foreign Banks in Poor Countries: Theory and Evidence, IMF Working Paper, WP/06/18. [CrossRef]

- Deyoung R., et G. Whalen, 1994. Is a consolidated banking industry a more efficient banking industry?, Office of The Comptroller of The Currency, Quarterly Journal, Vol 13, N° 3, pp 11-21.

- Dietsch M., 1996. Efficience et prise de risque dans les banques en France , Revue économique, Vol47, N 3, pp 745 – 754.

- Drakos K., 2003. Assessing the success of reform in transition banking 10 years later: an interest margins analysis, Journal of Policy Modelling, (25), pp 309–317. [CrossRef]

- Esho N., 2001. The determinants of cost efficiency in cooperative financial institution: Australian evidence, Journal of Banking and Finance, V 25, N 35, pp 941-964. [CrossRef]

- Feldstein M., 2002. Economic and financial crises in emerging markets economies: overview of prevention and management, NBER Working paper.

- Fries S., et A. Taci, 2005. Cost efficiency of banks in Transition: Evidence From 289 Banks in 15 Post-Communist Countries, Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol 29, pp 55-81. [CrossRef]

- Garber P.M., 2000. What you see vs. what you get: derivatives in international capital flows, paper prepared for World Bank–Brookings–IMF Financial Markets and Development Conference on “Emerging Markets in the New Financial System: Managing Financial and Corporate Distress,” Florham Park, New Jersey, March 30–31.

- Goldberg L., 2001. When is U.S. bank lending to emerging markets volatile? Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Mimeo.

- Goldberg L., B.G. Dages et D. Kinney, 2000. Foreign and domestic bank participation in emerging markets: lessons from Mexico and Argentina, FRBNY Economic Policy Review, 6 (3), pp 17-36.

- Hainz C., et M. Schnitzer, 2001. “The development of the banking sector in Eastern Europe : the next decade”, In: Winkler, Adalbert (Hrsg.): Banking and Monetary Policy in Eastern Europe – The First Ten Years, Palgrave, Houndsmills/Basingstoke, pp 205–216.

- Haiyan Yina, J. Yangb et Xing Lu 2020. Bank globalization and efficiency: Host- and home-country effects. Research in Internaional Business and Finance, Vol 54.

- Hermes N., et R. Lensink, 2004. The short–term effects of foreign bank entry on domestic bank behavior: does economic development matter?, Journal of banking and finance, vol 28, pp 553-568. [CrossRef]

- Huang T.H., et T.L. Kao, 2006. Joint estimation of technical efficiency and production risk for multi-output banks under a panel data cost frontier model, Journal of Productivity Analysis, 26, pp 87–102. [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky G., et C. M. Reinhart., 1999. The twin crises: the causes of banking and balance of payments problems, American Economic Review; 89(3), pp 473-500.

- Keeton W.R., 1999. Does faster loan growth lead to higher loan losses? Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Economic Review, 84 (2), pp 57-75.

- Kraft E., R. Hofler et J. Payne, 2002. Privatization foreign bank entry and bank efficiency in croatia A fourier-flexible function stochastic cost frontier analysis, Working Paper: The Croatian National Bank.

- Kroszner R., 1998. On the political economy of banking and financial regulatory reform in emerging markets, CRSP Working Paper, N° 472.

- Leightner J.E., et C.C. Knox Lovell, 1998. The Impact of financial liberalization on the performance of Thai banks, Journal of Economic and Business, (50), pp 115-131. [CrossRef]

- Levine R, 1996. Foreign banks, financial development, and economic growth, In: Claude, E., Barfied, (eds), International Financial Markets. AEi Press, Washington, DC.

- Levine.R, 1999. Foreign bank entry and capital control liberalization: effects on growth and stability, mimeo. University of Minnesota.

- Liu L., 2002a. Beyond sequencing: A risk management approach to financial liberalization, ADB Institute.

- Liu L., 2002b. Sequencing PRC.s banking sector reform after the WTO: options and strategy ADB Institute.

- Mathieson D., et J. Roldos, 2001. The role of foreign banks in emerging markets, Paper prepared for the FMI-World Bank-Brookings institution Conference on Financial Markets and Development, 19-21 April, New York.

- Mc Fadden C., 1994. Foreign banks in Australia, The World Bank.

- Montgomery H., 2003. The role of foreign banks in Post-crisis Asia: The importance of method of entry, Asian Development Bank Institute, Research Paper, N° 51.

- Nikiel E.M., et T.P. Opiela, 2002. Customer type and bank efficiency in Poland: implication for emerging market banking, Comptemporary Economic Policy, Vol 20, N° 3, pp 255-271. [CrossRef]

- Palinski A., 1999. Evaluation of bank debt restructuring in 1992-1998 for selected polish bank’s, Bank and Credit, National Bank of Poland, 12.

- Peek J., et E. Rosengren, 2000b. Implications of the globalization of the banking sector: the Latin American experience, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston New England Economic Review September/October 2000.

- Rojas-Suarez L., 1998. Early warning indication of banking crises: what works for emerging markets? With Application to Latin America, Deutsche Bank Securities Working paper.

- Shaffer S., 1998. The winner curse in banking, Journal of Financial Intermediation, 7, pp 359-92. [CrossRef]

- Tschoegl A.E., 2003. Financial crises and the presence of foreign banks, Paper presented at the World Bank conference on Systemic financial distress: containment and resolution, 7-8 October 2003.

- Unite A., et M. Sullivan, 2003. The effect of foreign entry and ownership structure on the Philippine domestic banking market Journal of Banking & Finance 27, pp 2323–2345. [CrossRef]

- Weill L., 2003. Banking efficiency in transition economies the role of foreign ownership Economic of Transition :September 2003, Vol 11, N° 3, pp 569-592. [CrossRef]

- Weller C.E, et A.S. Hersh, 2002. Increased competition from large foreign lenders threaten domestic banks, raises financial instability, Economic Policy Institute, Issue Brief N° 178.

- Weller C.E., 2000a. Financial liberalization, multinational banks and credit supply: the case of Poland”, International review of Applied Economics, Vol 14, N° 2, pp 193-211. [CrossRef]

- Williams B., 1998. Factors affecting the performance of foreign owned banks in Australia: a cross sectional study, Journal of Banking and Finance, (22), pp197-219. [CrossRef]

- Williams B., 2003. Domestic and international determinants of bank profits: foreign banks in Australia, Journal of Banking and Finance, V 27, N° 6, pp 1185-1210. [CrossRef]

- Williamson J., et M. Mahar, 1998. A survey of financial liberalization, Princeton Essays in International Finance, N° 211, November.

| Dependant variable explained: Cost efficiency score. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| Const | *0.7992599 (0.0421056) | -*0.4680112 (0.0256124) | *0.5229906 (.0130909) | *0.5172407 (0.0100529) | *0.5280572 (0.0092751) |

| Conc | *0.8763611 (0.0653141) | **0.3859111 (0.0218795) | *0.0734156 (0.0283208) | *0.0660494 (0.0172164) | *0.0715238 (0.0170773) |

| Presence | *-0.3802425 (0.1080383) | **-0.3650454 (0.0204817) | *-0.113541 (0.0243711) | **-0.0303685 (0.0149334) | *-0.0311921 (0.0150435) |

| Disinter | *0.0940121 (0.0261897) | *0.029934 (0.0072396) | *0.0267736 (0.0071825) | ||

| RealInterate | *0.0001677 (0.0000174) |

*0.0000486 (9.49 e-06) |

|||

| Ln size | **0.0180043 (0.001847) | ||||

| GDP PER CAPITA |

**0.0000771 (1.46e-06) |

||||

| OthrNProAssets | -0.0003637 (0.0066004) | ||||

| Coeffiexplo | ***-0.000068 (0.0000422) | ||||

| Net loans | **0.0003007 (0.0001422) | ||||

| χ2 | 362.9 (DF = 4) | 3486.28 (DF = 4) | 62.77 (DF = 4) | 32.32 (DF =4) | 26.52 (DF= 4) |

| Prob > χ2 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.000 |

| Log-likelihood | 362.9 | -4182.6669 | -1434.2935 | -2760.2958 | -2790.2618 |

| a: Dependant variables: adjusted efficiency score obtained following the Meta-frontier approach b: The results take into account data relating to domestic banks only c: The values in parentheses are standard deviations. DF: Degree of freedom * Variable significant at 1%. ** Variables significant at 5%. *** Variable significant at 10%. | |||||

| Dependant variable explained: Cost efficiency Score. |

||

|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | (6) | (7) |

| Const | *0.4527751 (0.0065672) | *0.6285067 (0.0475267) |

| Conc | *-0.0773446 (0.0125335) | *0.8723656 (0.0698601) |

| Presence | *-0.2303344 (0.0090853) | **-0.2018692 (0.0942831) |

| Disinter | *0.0201269 (0.0046199) | *0.0967843 (0.0252428) |

| Intereel | *0.0000213 (2.85e-06) | *0.0001658 (0.0000181) |

| PDEb | *-0.9304168 (0.0553807) | |

| PDEM | -0.6013531 (0.6188838) | |

| χ2 | 1179.16 (DL = 5) | 323.3 (DL = 5) |

| Prob > χ2 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Log-likelihood | 2428.453 | -6447.5456 |

| a: Dependant variables: adjusted efficiency score obtained following the Meta-frontier approach b: The results take into account data relating to domestic banks only c: The values in parentheses are standard deviations. DF: Degree of freedom * Variable significant at 1%. ** Variables significant at 5%. | ||

| 1 | For more details, see Atkinson et Cornwell (1994) and Huang et Kao (2006)). |

| 2 | This variable includes cash and assets that banks are required to hold with the central bank as reserve requirements. |

| 3 | Result confirmed by Unite A and M.J.Sullivan (2003); Cleassens.S et al (2001); Barajas et al (2000). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).