Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study among Moroccan medical students during the academic year 2021-2022. We included medical students from the 9 universities of Morocco; students who have validated their gynecology module, i.e., students in the 3rd cycle : 6th year, 7th year, interns, students in the process of completing their thesis as well as doctoral students who have not yet started their residency or practice as a general practitioner. We excluded: specialists, residents and general practitioners; students who have not completed their 5th year of medicine, students from foreign universities and students who have not given their consent.

Our survey contained three sections: general information, cervical cancer and Human Papillomavirus. We assessed their knowledge about each topic, their perceptions and their trainings’ satisfaction.

Knowledge was scored out of 36 points, with each correct answer counted as one point, broken down as follows: a score out of 20 for knowledge of cervical cancer (10 points for risk factors and 10 points for screening and diagnosis), out of 11 points for knowledge of HPV infection and out of 5 for HPV vaccine.

Perception was rated out of 10 points, with each perception with a positive connotation counted as one point, broken down as follows: a score out of 4 for the perception of cervical cancer and a score out of 6 for HPV infection and vaccination.

Satisfaction with the training was rated out of 40 points, with each item rated from 1 to 5 (from not at all satisfied to extremely satisfied), broken down as follows: a score out of 20 for satisfaction with the cervical cancer training and a score out of 20 for satisfaction with the HPV infection and vaccination training.

The questionnaire was reviewed by the authors and an epidemiology expert, and then a pilot study was launched with 10 students to ensure clarity of the questions. Ethical considerations were taken into account, and the university’s ethics board approved the study.

We collected the data passively via the electronic platform “Google Forms.” The questionnaire was shared throughout the 2021-2022 academic year, with three follow-ups: one in September, one in January, and one in June to all medical universities in the Kingdom. The questionnaire was preceded by a text explaining the nature and objectives of the study. The questionnaire was completed anonymously by the participants. Participants gave electronic informed consent by stating that they agreed to complete the questionnaire. The questionnaire was automatically terminated if the participants refused to take part in the study.

Descriptive data analysis was performed using: Google Forms and Microsoft Excel version 14.0. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA) and RStudio 1.4.1717. The p value was considered significant when it was less than or equal to 0.05. We used different tests to compare the groups by following the characteristics of each group. To compare between two groups, a parametric t-test was performed when both groups had numbers greater than 30 and a Mann Whitney test when one of the two groups had numbers less than 30. For comparisons between three or more groups, an anova test was used. For correlation analysis, we performed a non-parametric Spearman test.

Results

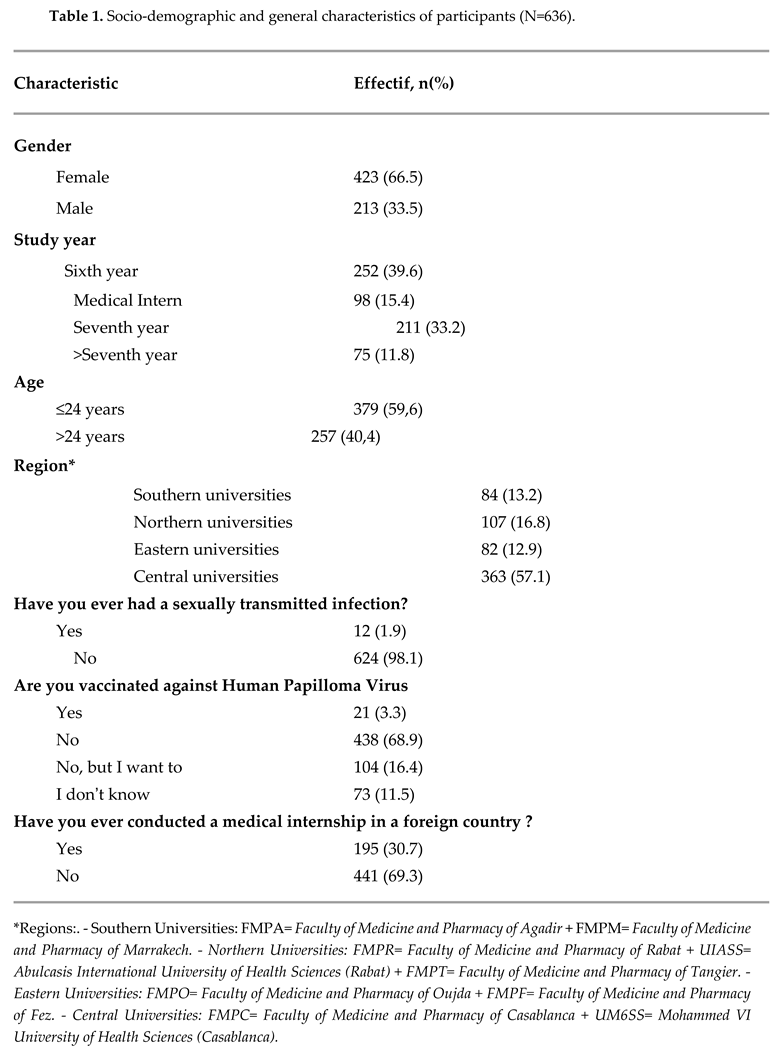

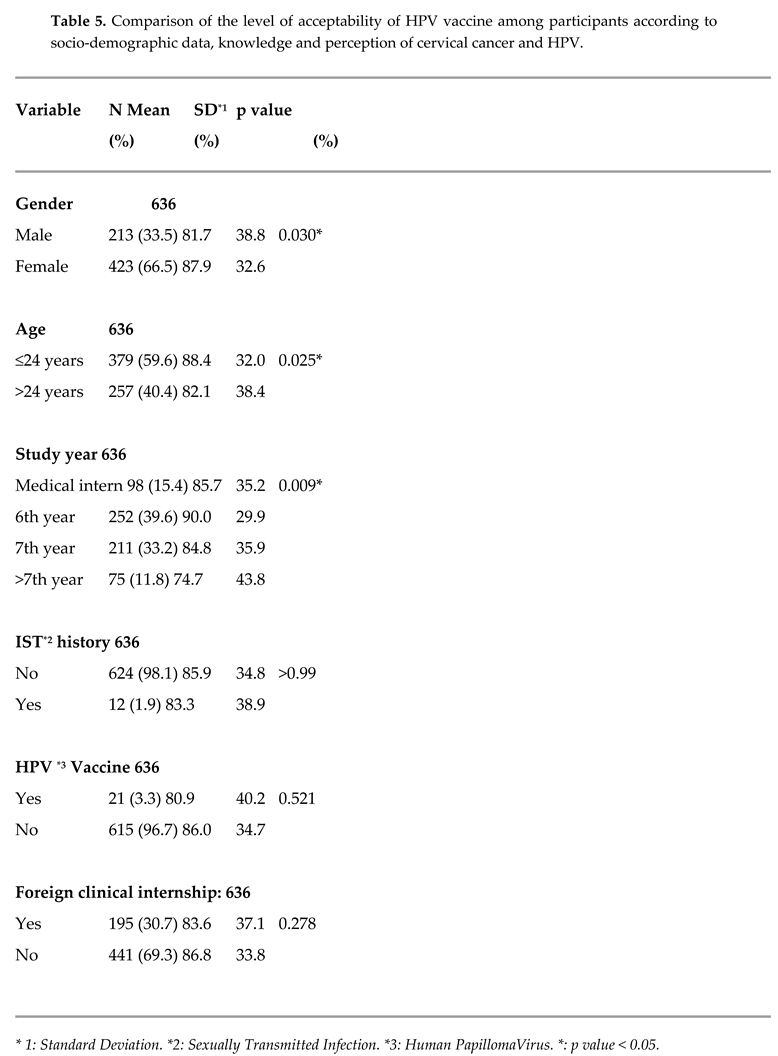

We collected 644 questionnaires, only 636 were included (8 did not give their consent). The age of the participants ranged from 20 to 30 years with an average age of 24.2 +/- 1.4 years. The sex ratio (M/F) in our population was 0.5. Students from central universities represented 57.1% (n=363) of our population and sixth year medical students 39.6% (n=252). Moreover, 1.9% (n=12) reported ever having a sexually transmitted infection and 3.3% (n=21) reported having been vaccinated against HPV. Age of vaccination ranged from 11 to 25 years, with a mean of 16.7 +/- 3.9 years, two students did not know their age of vaccination. In our population, 30.7% (n=195) have already completed a clinical internship abroad. (Table 1)

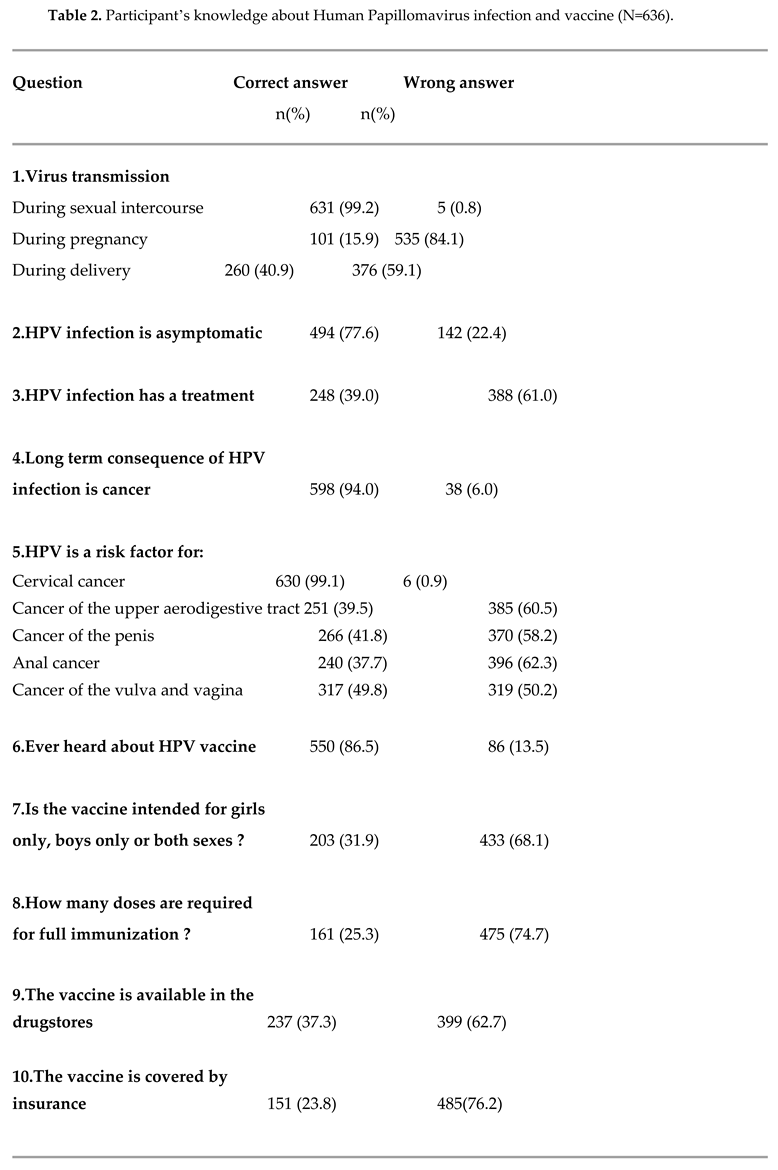

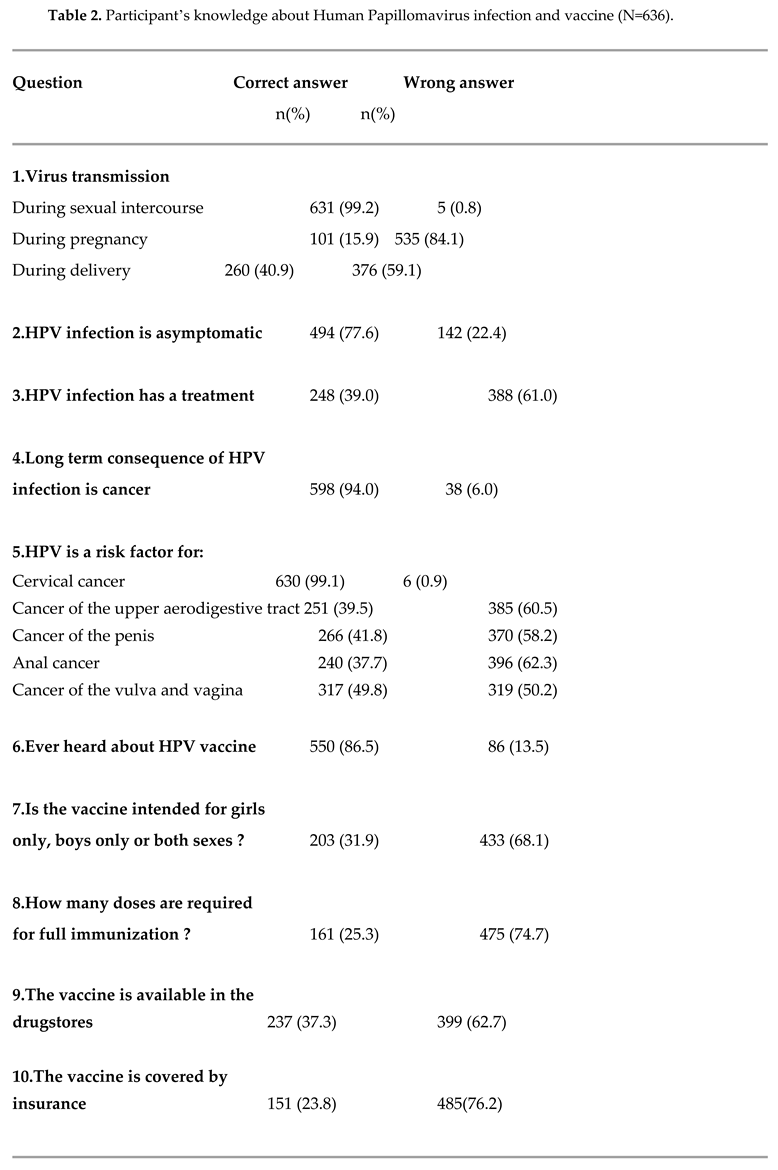

Regarding the HPV infection knowledge, we found an average of 6.3 +/- 2 /11, equivalent to a percentage of 57.2% of correct answers, the lowest score was 2 and the highest was 11. For the virus transmission they answered “yes” at 99.2% (n=631), 15.9% (n=101) and 40.9% (n=260) respectively to: “during sexual intercourse”, “during pregnancy” and “during delivery”. The statement “ HPV infection is asymptomatic” was answered “yes” by 77.6% (n=494) of our population. For the question “Is there a treatment for HPV infection?”: 36.6% (n=233) answered “yes”; 39% (n=248) “no” and 24.4% (n=155) “I don’t know”. 94.0% (n=598) thought that the long-term consequence of HPV infection is cancer. The participants answered that “HPV wasn’t a risk factor” for “cancer of the upper aerodigestive tract”, “cancer of the penis”, “anal cancer” and “cancer of the vulva and vagina” at respectively: 41.0% (n=261), 29.6% (n=188), 32.4% (n=206) and 21.4% (n=136). (Table 2)

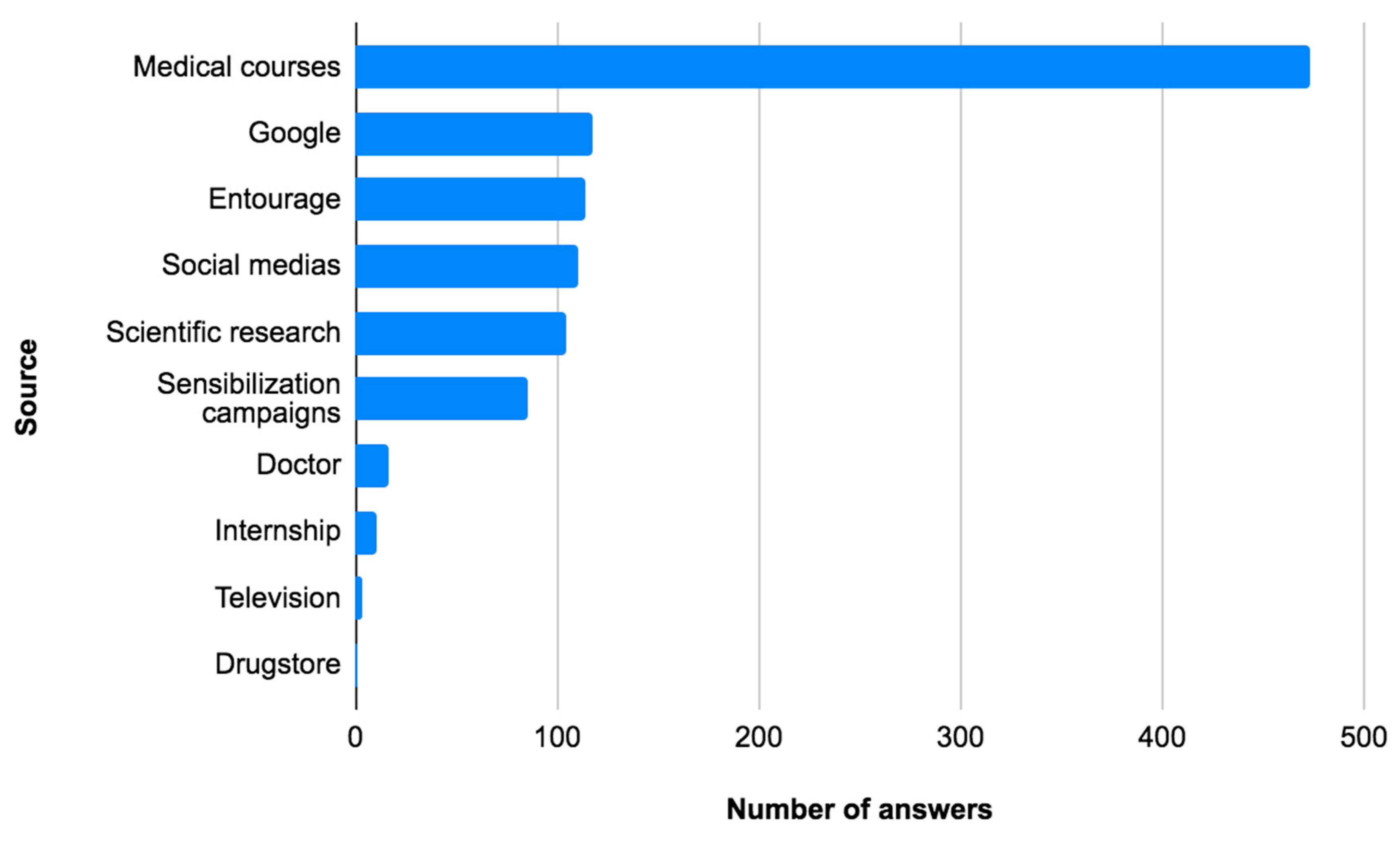

Moreover, we assessed HPV vaccine knowledge and found an average of 2.0 +/- 1.1/5, equivalent to a percentage of 40% correct answers, the lowest score was 0 and the highest was 5. 12.1% (n=77) had never heard about the HPV vaccine, 31.9% (n=203) thought that the vaccine was intended for both sexes, 50.5% (n=321) did not know how many doses were required for full immunization, 50.3% (n=320) did not know if the vaccine was available in the drugstores and 68.7% (n=437) did not know if the vaccine was covered by insurance (Table 2). Medical courses were a source of information about HPV for 84.9% of students, google for 21.2%, entourage for 20.5% and social medias for 20% (

Figure 1).

Furthermore, we assessed the satisfaction with HPV vaccine training and found an average of 7.3 +/- 2.6 /20, equivalent to a percentage of 36.5%, the lowest score was 4 and the highest 20. With an average of 1.9/5 for the quality of the theoretical training (38%), 1.8/5 for the hourly volume (36%), 1.7/5 for the quality of the practical training (34%) and 1.9/5 for the confidence in putting the knowledge into practice (38%).

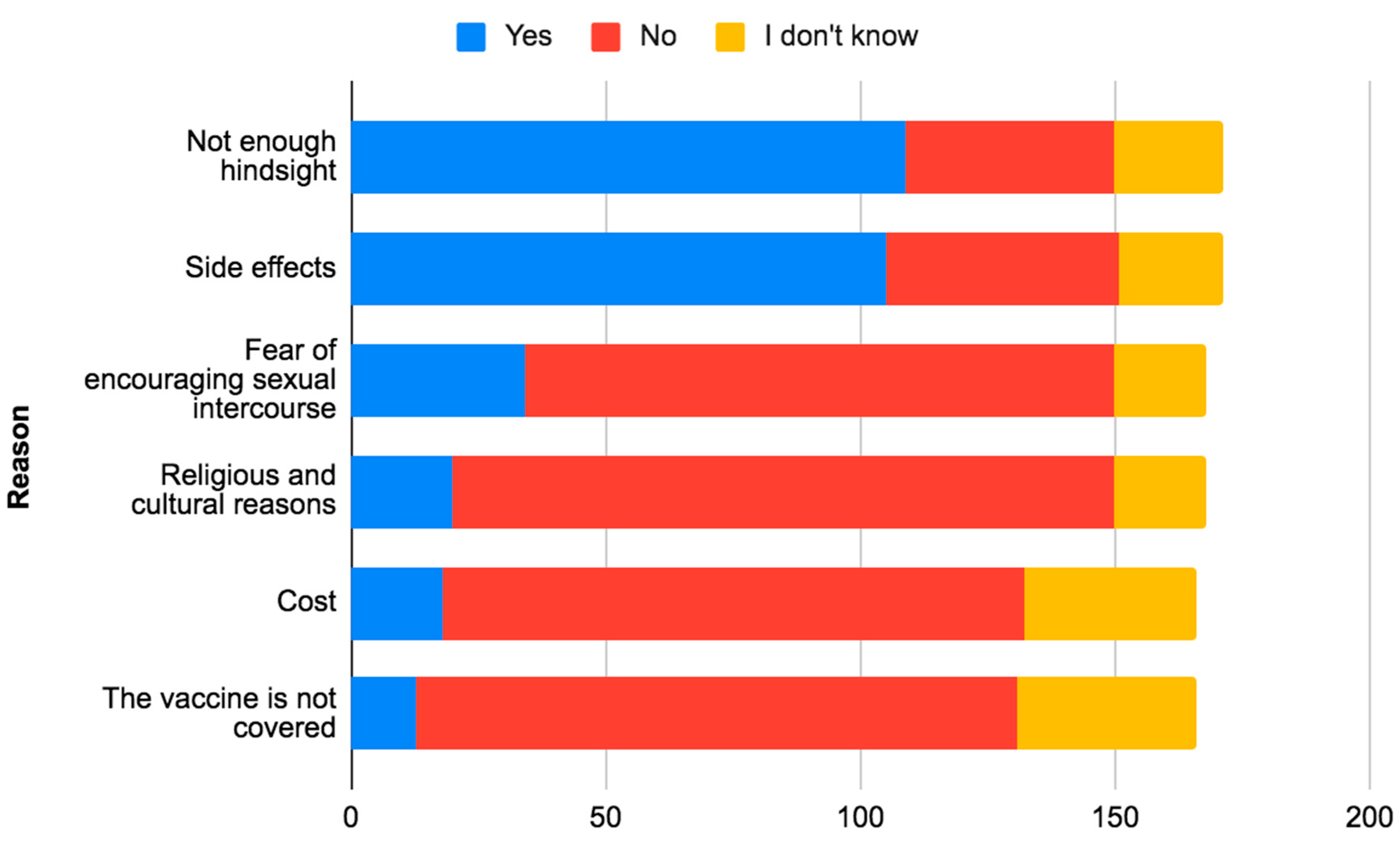

Regarding HPV vaccine’s perception, we found an average of 4.6 +/- 1.3 /6, which is equivalent to a percentage of 76.7%, the lowest score was 0 and the highest was 6. Among our participants, 90.2% (n=574) were in favor of HPV vaccination, 66.7% (n=424) thought that the vaccine was not easily accessible in Morocco, 88.7% (n=564) that the vaccine had not a lot of side effects, 86.9% (n=553) that the vaccine was effective in preventing cervical cancer, 76.6% (n=487) were in favor of systematically vaccinating their children and 85.8% (n=546) were in favor of integrating the vaccine into the national immunization program in Morocco. Among the reasons why Moroccan medical students would not be in favor of systematically vaccinating their children: not enough hindsight at 17.1% ( n=109) and side effects at 16.5% (n=105) (

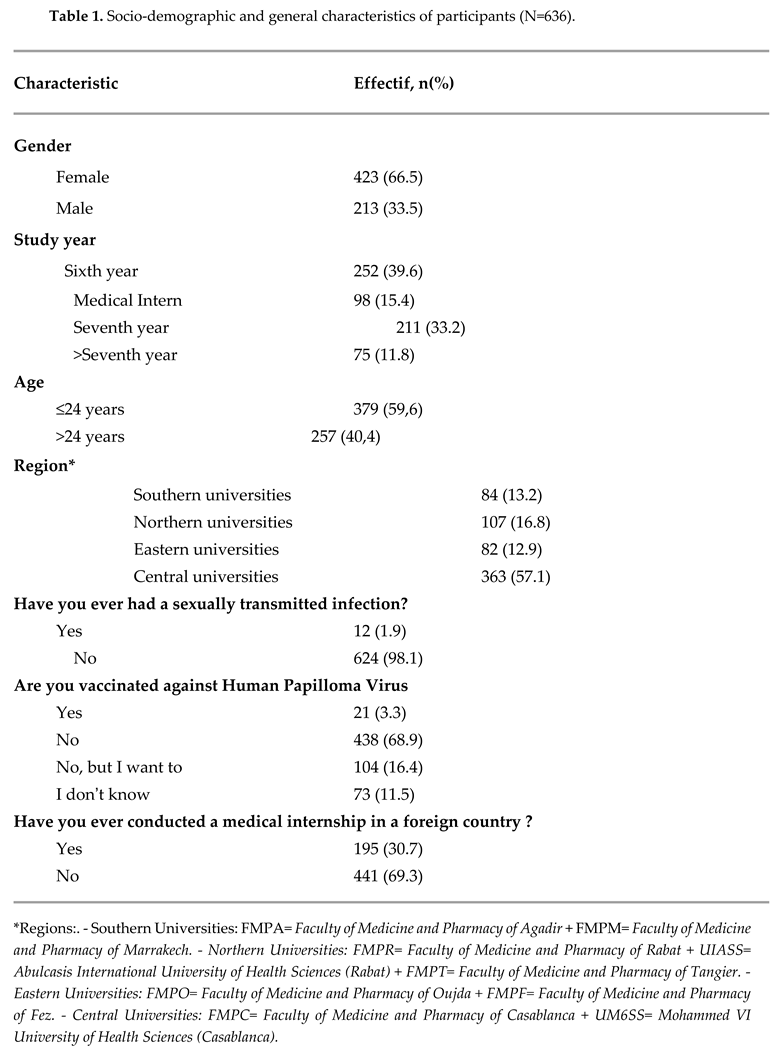

Figure 2). We compared the level of acceptability of HPV vaccine integration among participants according to socio-demographic and general characteristics and found a p-value<0.05 for: gender, age and study year. (Table 4)

The topic of HPV vaccination was already discussed during clerkships for 46.9% of the participants (N=298). Moreover, 15.4% of the students (N=98) had already witnessed the explanation of the interest of HPV vaccination to a patient and 6% (N=38) had already witnessed the prescription of this vaccine in a consultation. 87.1% of participants (N=541) responded that they would recommend HPV vaccine to eligible individuals in their future medical practice and 11.3% (N=70) responded that they did not know yet.

Discussion

In our study, our population was predominantly female, with a sex ratio (M/F) of 0.5. This is in line with other similar studies in the literature [

16,

17,

18,

20,

22], except for the study of A. Al-Darwish and al [

22] which had a sex ratio (M/F) of 1.4. The mean age of our study is much higher than the mean age of the rest of the studies (9-13), which is explained by the fact that our study was intended for students who had validated their gynecology module; which is taught during the fifth year of medicine at the Moroccan medical schools, thus third cycle students, while the rest of the studies were mostly intended for first or second cycle students. Our study has the lowest rate of HPV vaccination, with a percentage of 3.3% of participants vaccinated, closely followed by the study of S. Patel and al [

17]; this may be explained by the non-inclusion of HPV vaccine in the national immunization program in Morocco at the time of the study. However, this information is not available in all studies.

The percentage of correct answers on general knowledge of HPV infection and HPV vaccination was 52.5% in our study, much lower than in the rest of the studies [16,18,19,21[. The lack of knowledge was more pronounced for vaccine knowledge, with a percentage of correct responses of only 40%, which is nevertheless equivalent to that of the study by M. Alsous and al [

16].

Regarding knowledge of HPV infection, 99.2% (N=631) of the participants knew that it could be transmitted during sexual intercourse, compared with 88.9% in the Jordanian study [

16]. However, more than half did not know that it could also be transmitted during pregnancy and one third did not know that it could be transmitted during vaginal delivery; with high “I don’t know” rates of about one quarter for the last two cases. This is in contrast with the Evans and al. study, where 74.25% of participants answered the question of modes of transmission correctly [

21]. In our study, only 77.6% of participants knew that infection could be asymptomatic compared to 99% among graduate students in the Milecki and al. study [

18]. The question about the existence of treatment for HPV was divided, with the responses being almost proportional between “yes”, “no” and “I don’t know”, whereas the graduate students in the Milecki and al. study had a rate of 71% [

18]. Only very few students were aware that HPV infection was a risk factor for other cancers, namely 39.5% for upper aerodigestive tract cancer, 41.8% for penile cancer, 37.7% for anal cancer, and 49.8 for vulvar and vaginal cancer. This is consistent with the results of the Evans and al. study where only 33.6% of participants were aware that HPV was a risk factor for oropharyngeal cancers [

21]. The Milecki and al. study found slightly higher rates for undergraduates with 51% for vulvar and penile cancer, 63% for upper aerodigestive tract cancer and 48% for anal cancer; but much higher rates for graduate students with 80%, 95% and 83% respectively [

18].

There is a real lack of education regarding HPV vaccine knowledge, as only 31.9% (N=203) knew that the vaccine could be given to both sexes, a lower rate than the Jordanian study at 54% [

16] and Afonso and al. at 79% [

19] but higher than the Patel and al. study at 18.5% [

17]. In addition, 10.8% thought that one dose, 25.3% two doses and 13.4% three doses were needed to achieve good post-vaccination immunization; compared to 9.7%, 13.9% and 19.0% respectively in the Jordanian study [

16], a low rate was also found in the Patel and al. study where only 14.0% had the correct answer for the number of doses [

17] and a higher rate at 30% in the Evans and al. study [

21]. In both studies, more than half responded that they did not know the correct number of doses to deliver. The majority of the participants in our study did not know the availability of the vaccine in Morocco, 50.3% did not know if it was available at the pharmacy level and 68.7% did not know if it was refundable by insurance; these results are comparable to those of the Jordanian study where only 46.8% knew that the vaccine was available in Jordan [

16] and 38.3% in Saudi Arabia in the study of Al-Darwish and al. [

22]. While only 9.7% of participants from a medical school knew that it was available in Serbia in the study of Rancic and al [

20]. This lack of knowledge about vaccination was also found in the study of Adejuyigbe and al [

23], which found a good level of knowledge in only 21.1% of participants.

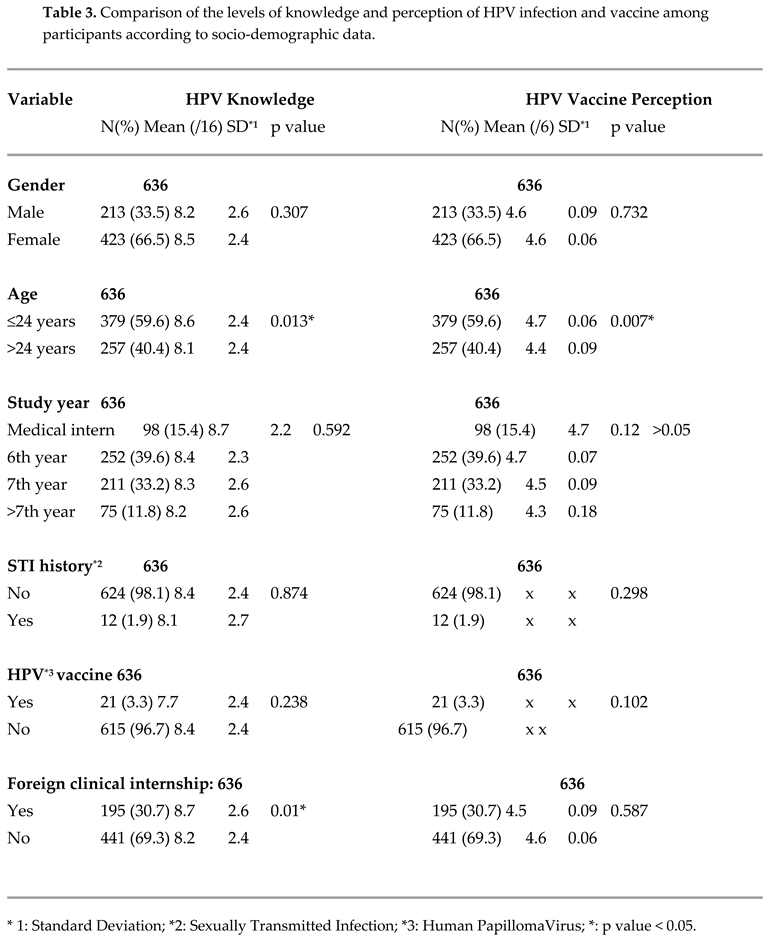

Statistical analysis of our study found that there was a significant association between knowledge of HPV infection and vaccination with age and clinical internship abroad, but not for gender, year of study, vaccination status and history of sexually transmitted infections. The misalignment between age and years of study may be explained by the fact that the distribution of years of study is not necessarily similar to that of ages. As for the rest of the studies, Alsous and al [

16] found a significant association with gender, university of origin and year of study; Milecki and al [

18] also found an association with year of study, sexual activity and number of sexual partners in the past, and no association with vaccination status; Wen and al [

24] found a significant association with gender, year of study and sexual activity but not with age, unlike our study. The study by Adejuyigbe and al [

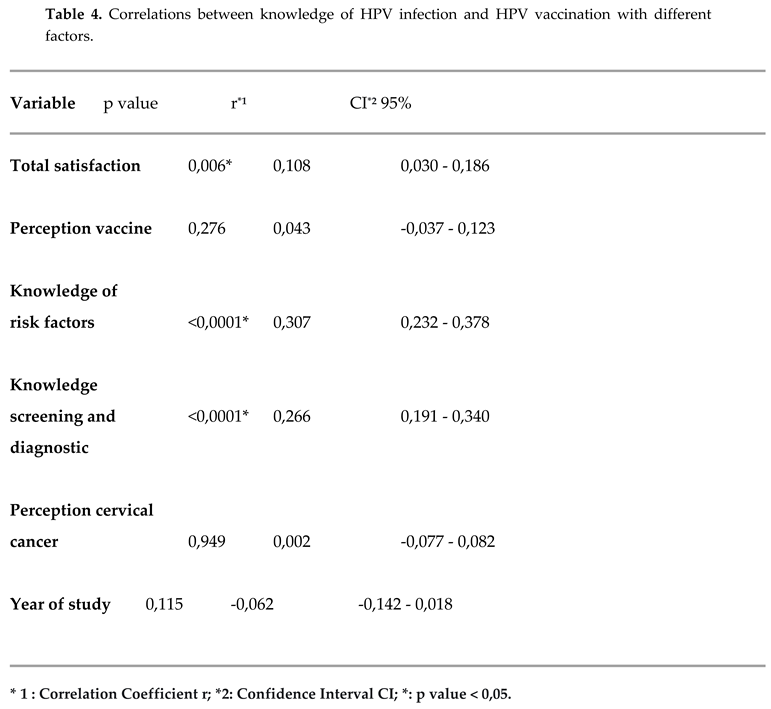

23] found that age and year of study were factors associated with the level of knowledge about HPV infection and vaccination. In our study, we found a correlation between knowledge about HPV infection and HPV vaccination with total satisfaction score and knowledge about cervical cancer risk factors and means of cervical cancer screening and diagnosis; this correlation was positive in all three cases. No other study found a Spearman-type correlation.

The four main sources of information on HPV vaccine cited by our series were “medical courses”, “google”, “friends and family” and “social networks” at 84.9%, 21.2%, 20.5% and 20% respectively. These figures are in agreement with those of the Jordanian study which found medical courses at 87.7%, Internet at 33.3%, books at 23.2% and social networks at 17.1% [

16]; but also the study of Patel and al. which found courses at 45.4% and 33.7% Internet [

17]; that of Wing and al [

24] which found courses in first position at 66.4% as well as that of Adejuyigbe and al [

23]. The study of Rancic and al. found another result with the media in first position at 62.6% [

20], which could be explained by the fact that it targeted students from all faculties.

Satisfaction with cervical cancer training was very low with a percentage well below the average at 36.5%, especially practical training which was counted at only 34.0%. Theoretical training, hourly volume, and confidence in practice had almost equivalent rates, which were recorded at 38%, 36%, and 38%, respectively. Confidence in applying knowledge was also lower than average in the study by Afonso and al. [

19] but quite high at 65.2% in the study by Evans and al. [

21]. No other study assessed satisfaction with training on HPV infection and vaccination.

In general, the students have a good perception of the HPV vaccine with a total of 76.7% in our study. The majority of them, 88.7%, were aware that the vaccine did not have many side effects, which is in line with the study by Afonso and al. which found a rate of 76.9% [

19]. Regarding the effectiveness of the vaccine in preventing cervical cancer, 86.9% thought it was effective, a rate similar to that of the Afonso and al. study at 91.1% [

19]. However, only 33.3% thought that the vaccine was easily available in Morocco.

In our study, the acceptability of the vaccine was significantly higher than the rest of the studies with a rate of 90.2%, which is contradictory to the rate of those vaccinated of 3.3% and the rate of those willing to systematically vaccinate their children which is only 76.6%. In addition, 85.8% of participants agreed that the HPV vaccine should be included in the national immunization program, a figure that is significantly higher than in other studies. The main barriers to acceptability of the vaccine in our study were lack of feedback (63.7%), side effects (61.4%) and fear of encouraging sexual intercourse (19.9%), which differs from the Jordanian study, where misinformation (62.5%), high cost (53.8%) and fear of complications (28%) were identified [

16]. In our study, high cost was not considered an obstacle at only 10.5%, as was the case in the study of Patel and al. which found a rate of only 7.5% [

17] and the study of Al-Shaikh and al. with a rate of 13.3% [

14]. Concerning the fear of promoting sexual intercourse, it was estimated at only 7% in the study of Afonso and al., contrary to ours [

19].

There are other studies that have focused on the acceptability of the vaccine in the general population. For example, in the study of Baddouh and al [

10], which targeted parents of Moroccan girls, acceptability was 63% and raised to 82% after explaining the causal link between HPV and cervical cancer, and 71% of them thought the vaccine should be part of the national immunization program, results slightly lower than ours. The reasons for rejection were dominated by fear of side effects in 51% of cases and cost in 40% of cases, unlike our study. Similar results were found in the study by Selmouni and al [

6], which also involved Moroccan mothers and fathers, with an acceptability rate of 76.8% for mothers and 68.9% for fathers, and reasons for refusal dominated by fear of side effects and lack of knowledge about the vaccine. However, a lower acceptability rate of 55% was found in the study of Bair and al, which targeted mothers of Latin origin [

8]; the acceptability rate was also low at 32% for mothers and 45% for fathers in the Moroccan study by Mouallif and al [

11]. A recently published study assessed the acceptability of HPV vaccination among living Muslims in the United States at 66%, with the main reason for rejection being the lack of information about the vaccine (63.1%) [

25], which highlights the essential role of the practitioner in educating and informing patients.

The acceptability of HPV vaccine is generally good in the Arab countries of the Middle East and North Africa [

12].

We performed a statistical analysis of the acceptability of integrating the vaccine into the Moroccan national immunization program according to the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants, which proved to be significant for gender, age and level of education; the study of Adejuyigbe and al [

23] found level of education as a factor, but not age and gender; the study of Milecki and al. [

18] found gender, having a close family member vaccinated against HPV and level of knowledge as final associated factors in the multivariate model; the study by Alsous and al [

16] found only the year of study as a socio-demographic factor associated with acceptability.

The topic of HPV vaccination is very rarely discussed in clinical placements, in fact it has already been discussed by only 46.9% of our participants and only 15.4% of the students have ever seen an explanation of the value of HPV vaccination for patients and 6% have ever seen it prescribed, mostly during a gynecology consultation. No other study has assessed practical experience with HPV vaccination.

Cervical cancer is an international scourge that is highly preventable through vaccination and screening measures. It is therefore very important to raise awareness among medical students, the future health leaders of tomorrow. The year 2022 was synonymous with change in our country, as the HPV vaccine was officially introduced into the Moroccan national immunization program in October 2022.

Through our study we have shown that there is a lack of knowledge about human papillomavirus infection and HPV vaccination and that very few medical students have ever witnessed the administration or explanation of this vaccine to a patient. In addition, only a limited number of Moroccan medical students are vaccinated against HPV, even though they are supposed to set an example for society. However, the acceptability of the vaccine is very positive among students. It is therefore essential to better educate our students on this subject and to act on the different factors influencing the lack of knowledge in order to eradicate cervical cancer from our country in the near future.