1. Introduction

Coffee is one of the most consumed beverages in the world. Consequently, millions of tons of coffee by-products, such as coffee pulp, mucilage and silverskin, are produced every year. Therefore, with increasing coffee production and the environmental impact of waste accumulation, this needs to be properly managed [

1]. In recent years, much research has been carried out to identify new coffee residue applications. Recent studies have evidenced that coffee residues contain a complex mixture of components, such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids and bioactive compounds, including caffeine, trigonelline, chlorogenic acids and diterpenes, giving this product unique characteristics [

2,

3]. Viñas et al. [

4] identified chlorogenic acid, caffeolquinic acid, feruloquinic acid and p-coumaroquinic acid as the main polyphenols and proanthocyanidins, as well as glycosides and epicatechin as flavonoids. Some of the phenolic compounds and alkaloids identified in coffee residues have been reported to have biological activity against different species of fungi [

5] which allows for the potential application of this extract as an antimicrobial agent. These applications require a preliminary separation of bioactive molecules from coffee by-products; thus, it is important to develop simple and efficient extraction methods to obtain extracts with high levels of bioactive compounds such as solid–liquid extraction [

6]. However, the fungi of the genus

Rhizopus are causal agents of deterioration during the marketing of fruit and vegetable products [

7] which is mainly responsible for the reduction of the useful life of the tomato [

8]. Control with agrochemicals causes resistance in phytopathogens against the few authorized fungicides, and efforts have been made to replace these products with materials, such as the use of natural residues contain bioactive compounds derived from plant extracts and mango by-products that have demonstrated the notable control exerted on various postharvest fungi [

9]. Chitosan is used in the preparation of edible coatings because it contributes to preserving the sensory quality and nutritional content of vegetables during storage [

10]. This polymer has a broad antimicrobial spectrum and can incorporate functional substances to reduce the damage caused by pathogens. Chitosan-based coating can be structured on micro- and nanometric scales to increase their effectiveness [

11]. Nanostructured coatings significantly improve shelf life and preserve the bioactive components in fruits [

12], have greater antimicrobial activity and barrier properties [

13].

The objective of this research was to extract bioactive compounds from coffee residues, identify chemical compounds in the extract using chromatographic techniques, and evaluate their efficiency in vitro and in vivo in the control of postharvest fungi when encapsulated in chitosan nanoparticles incorporated into nanostructured coatings as substitutes for synthetic fungicides.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Coffee Residue Extracts (CRE) and Chemical Profile by High-Resolution Liquid Chromatography and Mass Spectrometry (HPLC/MS)

The plant species

Coffea arabica was collected in Nepantla, Mexico State, Mexico. The fruit was submerged in a 0.03% citric acid solution to retard oxidation. The peels were separated, weighed and macerated in a 1:5 ratio of ethanol at 96% for 24 h in the dark at 27°C. It was filtered and concentrated on a rotary evaporator (Buchi R-300, Labortechnik, Switzerland) under the conditions reported by Istúriz-Zapata [

36].

The compounds were identified using HPLC-MS analysis with Ultimate 3000 equipment (Dionex Corp., CA) equipped with an array of diodes and a micrOTOF Q-II analyzer in electrospray ionization (ESI) system mode (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA) was used. Chromatograms were obtained at 280 nm, the data were analyzed with Data Analysis 4.0 software (Bruker Daltonics) to obtain the detected compounds and their concentrations [

14].

2.2. Nanoparticle Elaboration and Characterization

The nanoprecipitation method proposed by Luque-Alcaraz et al. [

15] was employed for chitosan nanoparticle elaboration. Chitosan was dissolved in glacial acetic acid (1% v/v) and distilled water to form the chitosan solution (0.05% w/v); the solution was adjusted to pH 5.6 with 1N NaOH. Using a peristaltic pump (MasterFlex C/L, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), 18.75 mL of 0.05% chitosan was passed at a rate of 0.05 mL/minute into a 300 mL solution of 96% cane ethanol (Milab Distribuidora) and 0.3% v/v Tween 80. Subsequently, the nanoparticle solution was concentrated in a Rotavapor® R-300. The same procedure was used to prepare the nanoparticles with the coffee residue extract (CNP-CRE) at a concentration of 0.05, 0.5, 1, 1.5 and 2.0 % v/v, adding the extract to the ethanol and Tween solution.

The average size distribution of CNP and CNP-CRE and their charge (Zeta potential) were determined using a Zetasizer Nano-ZS90 (Malvern Instruments, United Kingdom). Samples were sonicated for 15 min at 64 Hz before analysis. With Confocal Micro-Raman Spectroscopy equipment coupled with Fourier Transformed Infrared (FTIR) (CRAIC Technologies, USA), a reflection spectrum of the functional groups in the residue extract, CNP and CNP-CRE samples was obtained. For TEM analysis and with the purpose of obtaining a homogeneous emulsion of nanoparticles, 500 μL of samples were centrifuged for 8 minutes at 8000 rpm. The supernatant was removed, and 500 µl of ethanol was added. The sample was shaken until the pellet was dissolved with the help of a vortex, and 20 µL of CNP or CNP-CRE was placed on a copper grid. The shape, aggregation and size of the particles were observed using a JEM 2010 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, USA) at an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. The particle size was reported as the average of the samples observed, which was calculated using IMAGEJ version 1.46 software.

2.3. Nanostructured Coating Elaboration

Two coatings were prepared according to the procedure of Correa-Pacheco et al. [

16], and Istúriz-Zapata [

36]. Coating with chitosan nanoparticles (CCNP) and coating with nanoparticles with coffee residues extract (CCNP-CRE), at a concentration of 1.0% of CRE were elaborated.

2.4. In Vitro Assays

To evaluate the residue extracts, PDA medium was prepared, sterilized, mixed with coffee residue extracts at concentrations of 2.5, 5, 7.5 and 10%, and poured in Petri plates (60 × 15 mm2). A 5 mm diameter cylindrical fragment from actively growing R. stolonifer was placed in the center of each box. The boxes were incubated in darkness for 3 days at 28 ± 2°C. The equatorial diameter of the mycelial growth of each fungus was measured with a digital vernier every 24 h until the growth of the fungus reached the edge of the box in the control group.

The germination inhibition (GI) and morphological changes on

R. stolonifer were evaluated by the technique described by Black-Solís et al. [

17] for the different concentrations. To visualize the changes in the structures, the conidia were observed with a confocal laser microscope (Carl Zeiss, model LSM 800, Germany) and Zen 2.5 blue edition software. The conditions were as follows: laser at 488 nm, 8% intensity, detection wavelength of 450–700 nm, PinHole 0.50, AU/18 μm, with a 40× apochromatic objective (40×/ 1.3).

For the in vitro evaluation, each of the solutions of nanoparticles was added to PDA culture medium in volumes of 50, 100, 200 and 300 µl/mL, the control contained PDA only. Measurements of mycelial growth were made every four hours until the control treatment reached the edge of the box. A database was built to plot the equation of the line and obtain the slope (growth rate).

The percentage of mycelial inhibition was calculated using equation 1:

where A and B are the mycelial growth of the fungus in the control group and the treatments, respectively.

2.5. Preharvest Assay

Naples tomatoes were grown in the greenhouse at a temperature of 26°C in cycles of 12 h of light and 12 h of darkness. Inorganic fertilization was applied and three experimental groups were tested, spraying the fruit with 500 µL of the following solutions for each bath: CCNP, CCNP-CRE and sterile distilled water (control). These were applied 20 d after flowering. The tomatoes were evaluated at 0, 15 and 30 d after the application of the coating at ambient temperature.

2.6. Postharvest Assay

The coatings were applied to Naples tomatoes of homogeneous size, harvested at commercial maturity stage 4 (USDA). The fruit was disinfected with 1% v/v sodium hypochlorite for 30 s, rinsed with distilled water, and dried at room temperature (28 ± 2°C). After this period, the fruit was sprayed with 500 µL of the nanocoating solutions of CNP, CNP-CRE, distilled water (control) and allowed to dry. Six fruits per treatment, per evaluation day (3), were used. The fruit was incubated at 10 ± 2°C and 96% RH. The tomatoes were evaluated at 0, 10 and 14 d after the application of the nanocoating.

2.6.1. Quality Variables: Weight Loss, Firmness, Color, Total Soluble Solids (TSS) and Titratable Acidity (TA).

Weight loss was determined as the weight difference between the initial day and the evaluation day using a digital balance (Ohaus CS2000, USA), and the results were expressed as a percentage. Firmness was measured in two equidistant areas of the fruit using a digital penetrometer (T.R. Turoni, Italy), equipped with a cylindrical tip of 8 mm in diameter, the result was reported in newtons (N). The color indices that were measured in the fruit were hue angle (°Hue) and color purity (CHROMA). The results were calculated from the a* and b* coordinates obtained with a digital colorimeter (Konica Minolta Sensing, Tokyo, Japan) from the measurement of two equidistant areas of the same fruit. A fruit was considered a repetition. Each treatment had six repetitions.

Equation to calculate the angle °Hue:

Equation to calculate color purity (CROMA):

Total Soluble Solids (TSS) was measured by placing a drop of fruit juice directly on the sensor of the handheld refractometer (Atago N-1E, Japan). Previously, the equipment was calibrated with distilled water in the sensor, each treatment had three repetitions.

Titratable acidity was determined using the method of the Association of Official Analytic Chemists [

18]. This consisted of taking 10 g of tomato, adding 50 mL of distilled water, and grinding the sample with a mixer-type homogenizer (Taurus, Mexico) until it had a homogeneous appearance. The mixture was then filtered; subsequently, 5 mL was titrated with 0.1N NaOH (Fermont, Nuevo León) until a pH of 8.3 was attained. The percentage of titratable acidity was reported as a function of citric acid (0.0064 g) as the predominant organic acid in the sample.

2.6.2. Biochemical Variables

The extraction of carotenoids was based on the technique described by Rodriguez-Amaya [

19] with some modifications. One gram of tomato was weighed and macerated in 5 mL of a hexane/acetone/ethanol solution (50:25:25 v/v). The macerate was centrifuged (Prism Labnet, USA) at 6500 rpm for 10 min. The hexane phase was recovered and made up to 10 mL with hexane. The absorbance of the hexane samples was measured in a Genesys 10s UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) at 450 nm. Absorbance values were substituted into the following formula to calculate the total carotenoid content:

Molar extinction coefficient β-carotene = 2505 nM−1) cm−1

This process was carried out for each tomato, with three repetitions for each fruit.

2.6.3. Physiological Variables

The fruit (2) was placed in hermetically sealed containers for 1 h at room temperature (three containers for each treatment). A 5 mL sample was collected with a syringe and placed in vacutainer tubes at 8°C until use. One milliliters of each sample was taken and injected into a model 7890B GC gas chromatograph (Agilent Technologies, USA) with helium as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 10 mL/min. The equipment had two columns: HP-PLOT/Q and CP-MOLSIEVE 5A (Agilent Technologies, USA), a flame ionization detector (FID) at 300°C, and a thermal conductivity detector (TCD) at 250°C. The injector was kept at 200°C in split mode 1:10 for CO2 and in splitless mode for ethylene. The content of CO2 was expressed as mL CO2 kg−1 h−1 and the ethylene gas content was expressed in mg C2H4 kg−1 h−1.

2.6.4. Disease Incidence and Severity Index of R. stolonifer on Tomato

The tomato fruit was disinfected with sodium hypochlorite (1%) for 30 s and rinsed again with distilled water. The fruit was allowed to dry at room temperature (28 ± 2°C) and further inoculated as a curative treatment (before treatment applications). Thus, the tomato was injured with a sterile dissecting needle in the equatorial part of the fruit and inoculated in two wounds per fruit with 10 μL of spore suspension of

R. stolonifer (10

5 spores/mL). All fruit was placed individually in a high moisture chamber and incubated at room temperature for 24 h (28 ± 2°C). After this period, the disinfected and inoculated fruit was sprayed with 500 μL of CCNP and CCNP-CRE. The same procedure was performed with the control fruit, which was immersed only in distilled water. The disease incidence and severity index were determined after 3 days of incubation using the following formula:

The severity index was determined by the affected surface.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

In vitro and in situ experiments were performed using a randomized experimental design. Parametric data were analyzed with a two-way repeated measures analysis of variance and Tukey test (P<0.05). Data analysis was carried out using Sigma Plot 12.0.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterization of CRE by HPLC-MS

In total, 9 compounds, which belong to seven functional groups, namely carboxylic acids (40.92%), polyphenols (2.27%), alkaloids (42.97%), monosaccharide (3.64%), purine base (5.52%), amino acid (2.86%), and amides (0.01%) (

Table 1), were identified.

Caffeine was the most abundant compound belongs to the group of nitrogenous secondary metabolites and has been widely identified in coffee [

20,

21]. Sangta et al. [

22] reported 71% inhibition of the mycelial growth of

Alternaria bassicicola in the presence of caffeine and catechin. Gallic acid is a compound from the group of polyphenols that has been recorded in coffee pulp residues, although the amount and presence of this compound depend on the cultivar. Gallic acid and catechin inhibited the development of

Penicillium digitatum 100% [

23]

. Chlorogenic acid inhibits the development of

R. stolonifer 89% and the germination of Sclerotinia spores 100% [

24,

25]. Xanthine and vulgaxanthine molecules were observed, which are responsible for the pigmentation of yellow tones and have antimicrobial activity.

3.2. Nanoparticle Characterization

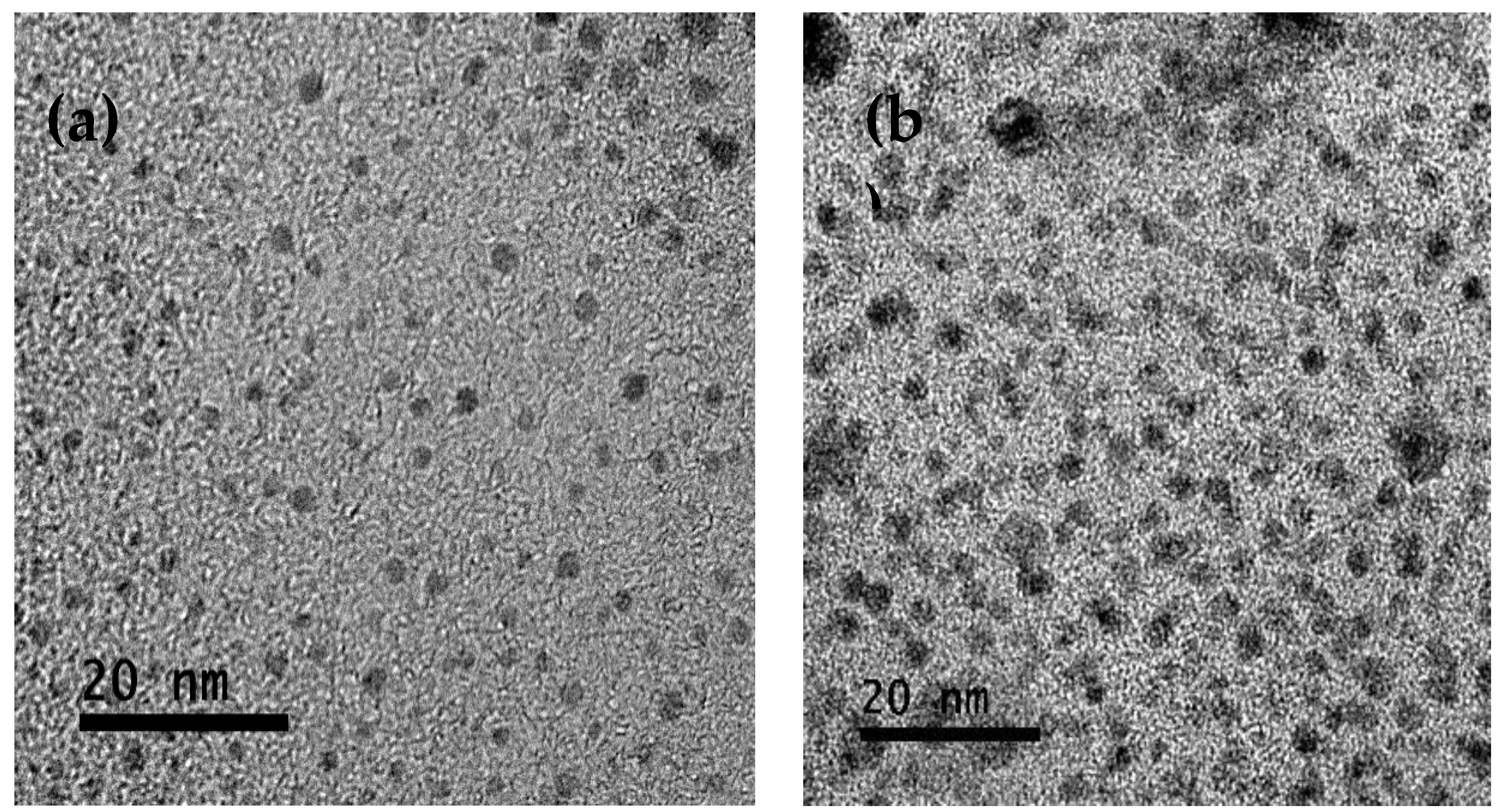

The morphology of the nanoparticles is shown in

Figure 1. TEM micrographs showed a spherical shape and were well dispersed in CNP (

Figure 1a) and CNP-CRE (

Figure 1b). The average size was 2.4 ± 0.24 nm and 3.9± 0.55 nm for CNP and CNP-CRE, respectively. The average diameter increased after CRE incorporation. It has been reported in the literature that the incorporation of essential oils [

12,

19] or plant extracts increases the size of chitosan nanoparticles.

The micrographs obtained with TEM showed that CNP-CRE was agglomerated, which agrees with the low Z potential value obtained for the CNP-CRE of −0.89 mV. It has been reported that chitosan nanoparticles added to cinnamon oil with low Z potential values −1.32 mV had an effect in reducing the growth of

Fusarium solani [

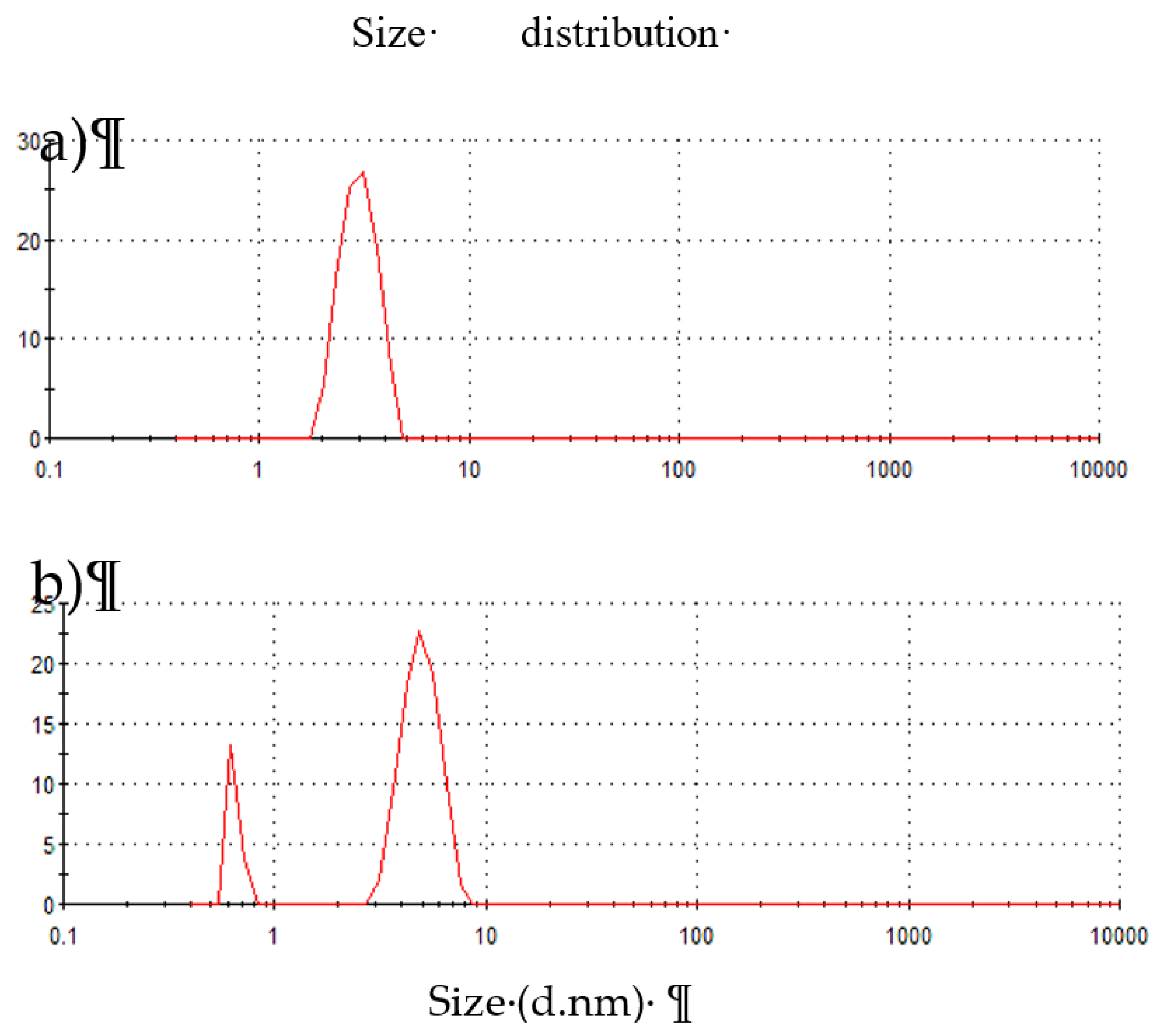

12] it was also observed in this study. The results for the particle size distribution calculated by the DLS are shown in

Figure 2. The distribution for CNP was unimodal, with 88.3% of the population of nanoparticles between 3 and 4 nm (

Figure 2a), and a Z potential of −1.62 mV was obtained. For CNP-CRE, a bimodal size distribution was observed, with 83.1% of the population being between 2.69 and 8.72 nm for nanoparticles with a higher diameter; 16.9% were between 0.53 and 0.83 nm for small nanoparticles (

Figure 2b), with a Z potential value of 0.89 mV. The differences in size between the CNP and CNP-CRE may be related to a stabilization in the suspension of CNP-CRE due to the anionic components in the extract, which prevents its agglomeration and precipitation. In this study, the values of particle size obtained by TEM were smaller than the values reported by DLS. Particle size and distribution depend on the preparation method and characterization technique used for the measurement [

26,

27]

.

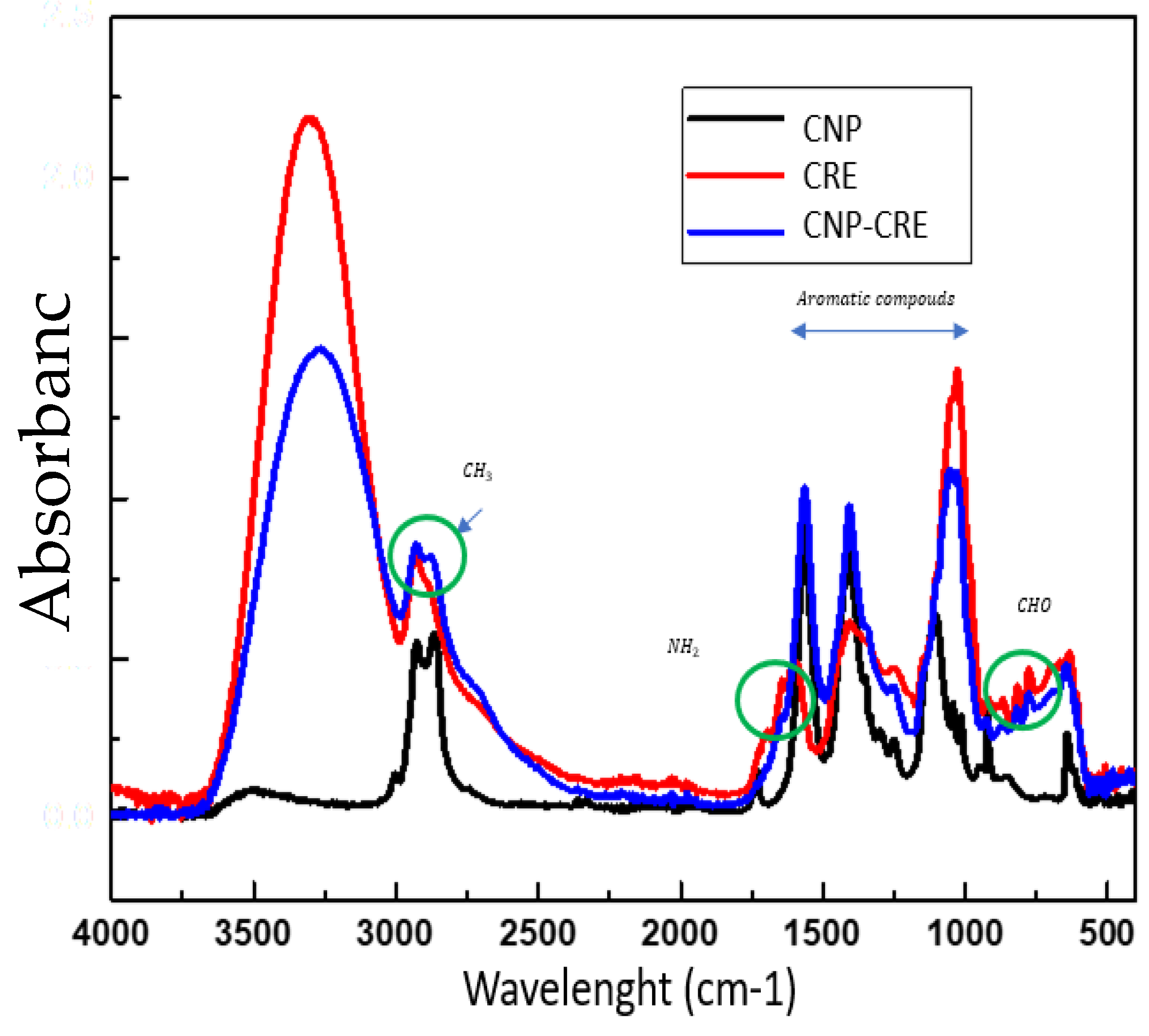

The functional groups of CNP and CNP-CRE were determined by FTIR analysis (

Figure 3). The characteristic absorption bands are at 1600 cm

−1, corresponding to the amino groups (NH

2) of chitosan [

27]. Barrios-Rodríguez et al. [

28] reported a broad band with a peak at 3280 cm

−1 corresponding to (OH) groups. An analogous band between 3000 and 3648 cm

−1 is seen in the CRE spectrum. Peaks are also observed between 2823 and 3000 cm

−1 corresponding to the methyl group (CH), which is present in the caffeine alkaloid (2800–3000 cm

−1) [

29]. Akbar et al. [

30] pointed out that an absorbance between 2800 and 2900 cm

−1 is associated with the presence of the methyl group in an ethanolic extract of

Arabica coffee.

The peaks between 1500 and 1000 cm

−1 are due to the presence of residual acids (C-O), carbohydrates (CHO) and nitriles (C-N). Furthermore, the peak at 1408 cm

−1 could be related to chlorogenic acid. Within this functional group, Cortés & Guzmán[

31] reported the presence of quinic acid at 1053 cm

−1. A peak at 1048 cm

−1 was observed in this study and can be attributed to the presence of quinic acid. The green circles indicate the presence of the coffee extract in the chitosan nanoparticles. The integration of amino groups at 1600 cm

−1 was observed in the CNP-CRE spectrum. However, the biomolecules present in the CRE were coupled with chitosan nanoparticles, as the same peaks were observed in the CNP-CRE spectrum.

3.3. In Vitro Assays

Significant differences were observed between the concentrations of Nepantla CRE. The lowest mycelial growth was from a concentration of 5 to 10% compared to the control. Peñuelas-Rubio et al. [

32] reported that the application of ethanolic extracts of

Larrea tridentata at a concentration of 250 ppm inhibited the growth of

Rhizopus oryzae 100%, and at a concentration of 2000 ppm, it reduced the growth from 5 to 1.15 cm in

Penicillium polonicum. Germination of 1% was obtained with CRE at a concentration of 10% after 8 h of incubation (

Table 2). Similar results were reported by Alvarado-Hernández et al. [

33] when applying clove essential oil at 0.1 mg/mL on

Rhizopus spores; the germination percentage was 32%, and when increasing the dose to 0.3 mg/mL, the germination percentage decreased to zero.

Means with capital letters indicate significant differences between treatments Tukey (p<0.05)

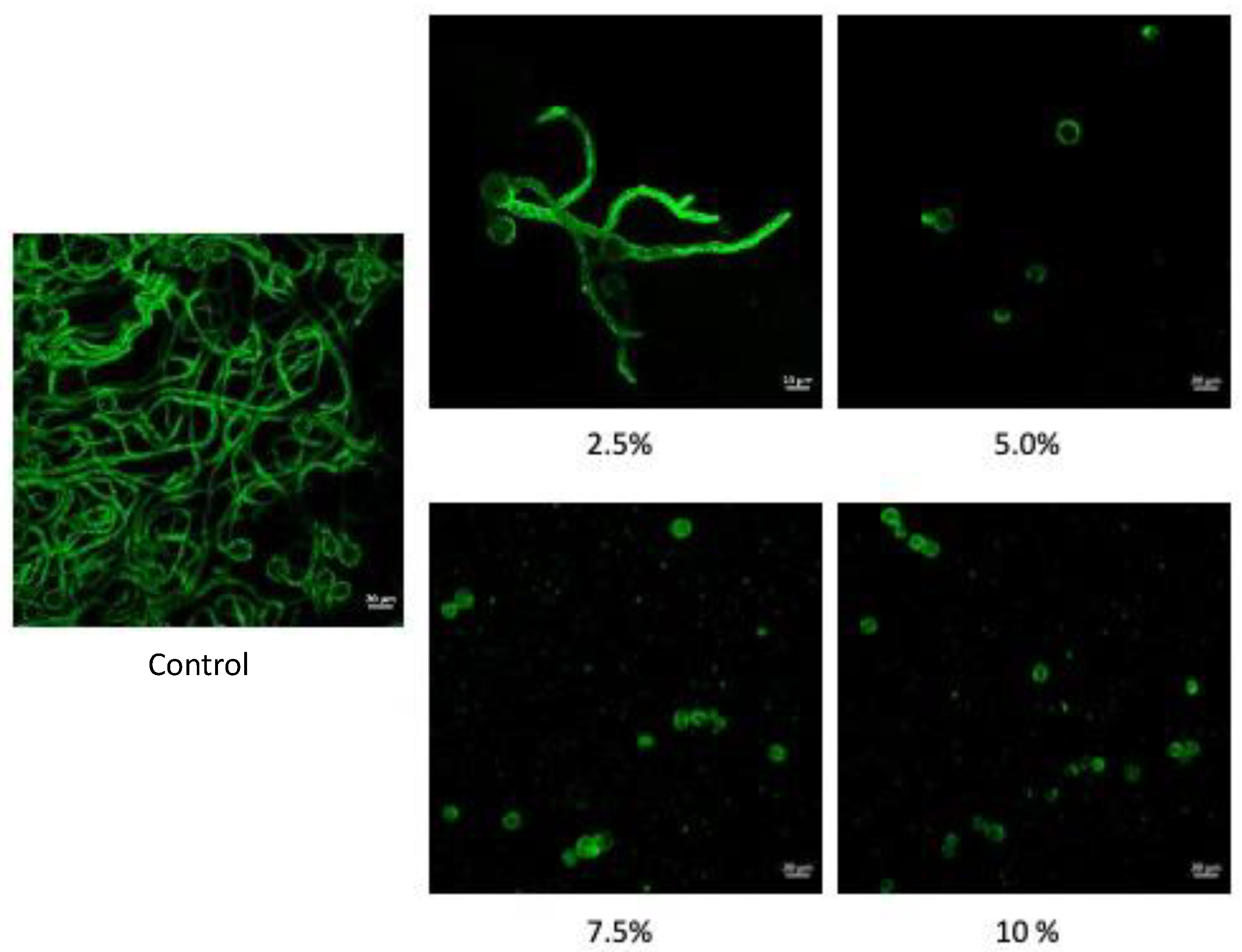

The micrographs obtained by laser confocal microscopy for the spores of

R. stolonifer at 8 hours of incubation in CRE showed the inhibition of the development of the germinative tube at a concentration of 5%, compared to the spores of the control, which after 8 hours emitted a germ tube and had hyphal development (

Figure 4). With increasing concentrations and secondary metabolites of CRE, spore germination decreased. The spores that were in contact with the extracts of CRE exhibited changes in size and structure conformation, as well as deformation and internal spore degradation. Some authors have reported that most oils stop spore germination. However, none of the treatments caused deformation in the spores of

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides [

34]

. The essential oils and extracts of aromatic species with biological activity against phytopathogens are related to the damage to the cytoplasmic membrane, the degradation of the cell wall, damage to proteins, filtration of cell content, coagulation to the cytoplasm or a decrease in the motive force of the cell [

35]

.

In previous works to prepare CNP and extracts, it has been reported that by decreasing the concentration of the extract, the biological activity is more efficient [

36], for this razon concentration of CRE 1% was used in this research. The growth of the pathogen in the CNP-CRE 1% treatment was slower than in the control. The growth rates of CNP100 CRE at 0.05% and CNP50 CRE at 1% (0.0749 and 0.0748, cm/h, respectively) had the lowest values compared to the control (0.1426). This same effect was observed in the mean mycelial growth (MG), where both treatments decreased MG (1.138 and 0.967 cm, respectively) compared to the control (2.184 cm). Mycelial growth inhibition (MGI) was 41.85% with CNP100 CRE at 0.05% and 42.7% with CNP50 CRE at 1% (

Table 3). By encapsulating the coffee residue extract in the nanoparticles, lower concentrations of the extract can be used and greater efficiency of inhibition of mycelial growth and spore germination can be obtained compared to the application of the unencapsulated extract. Hernández-Lauzardo et al. [

37] reported that for a concentration of 2 mg/mL of chitosan, a MGI of 20% was observed. In this study, the chitosan concentration for the preparation of nanoparticles was four times lower (0.5 mg/mL), and a MGI of 31% was obtained. The inhibitory effect was possibly due to the electrostatic interactions between the CNP, which has a positive charge given by the amino groups (NH

2), and the negative charges of the phospholipids present in the fungal membrane, which affects its integrity [

38] and allows the polymer to enter the cell cytoplasm, damaging the rest of the organelles.

Data represent mean mycelial growth (MG) ± SD, Standard Deviation. Values with different lowercase letters in the same column are statistically different (p<0.001). Mycelial Growth Inhibition, MGI (p<0.008).

3.4. Preharvest Assay

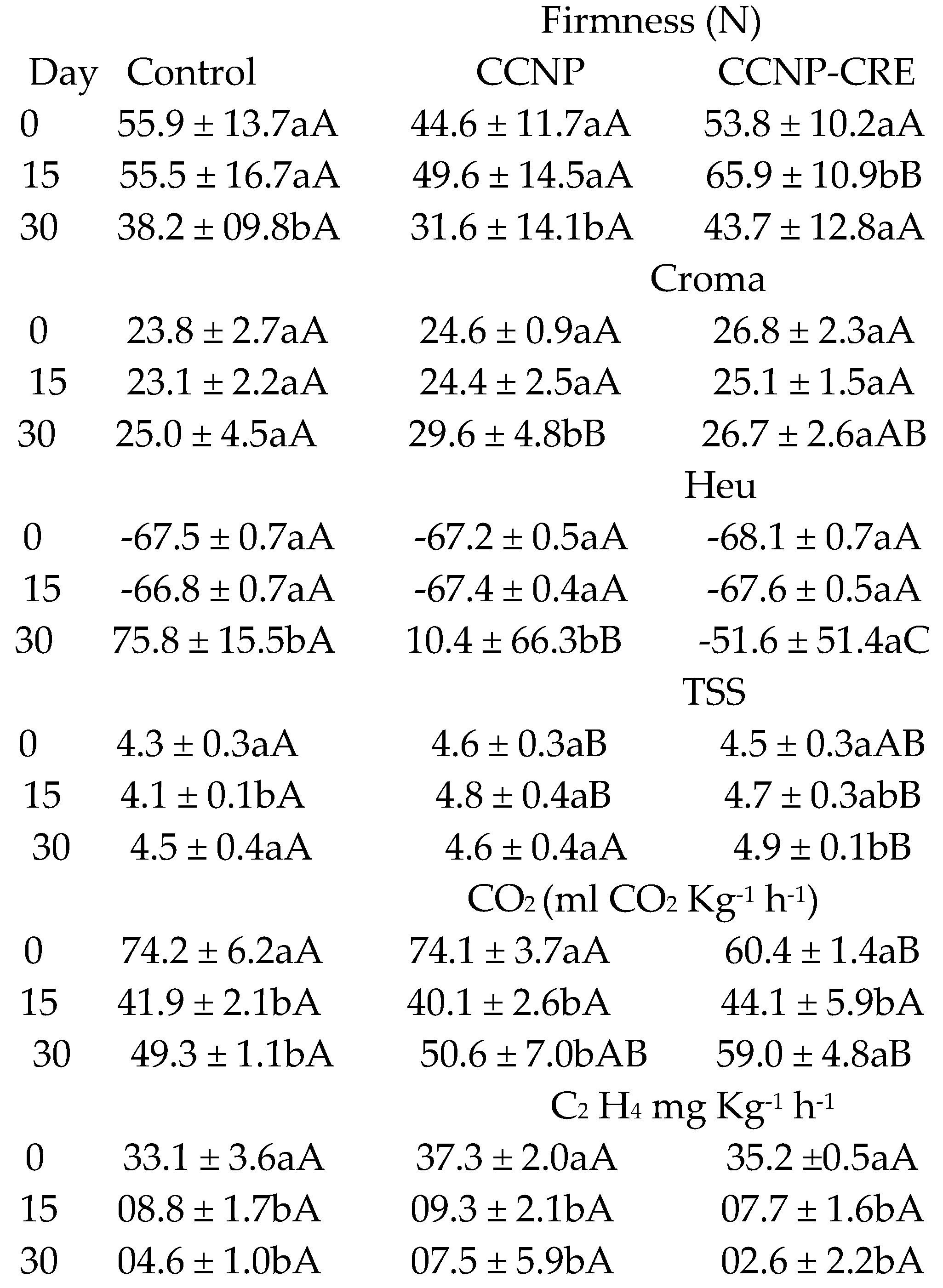

3.4.1. Effect of Coatings on the Quality and Physiological Parameters of Fruit

The firmness results did not show significant differences between the treatments (F=8.658) (

Table 4). On day 30 of the evaluation, fruit treated with CCNP-CRE had higher firmness with significant differences (p>0.05) compared to the control. The intensity of the colour reported with the variable CHROMA and the Hue angle showed significant differences at the end of the evaluation between the control and the treatments, attributed to the effect of the treatment (p<0.001). Tomatoes coated with CCNP-CRE on day 30 had negative values in the hue variable, indicating that they were not in the red tones within the chromaticity diagram. These values corresponded to maturity index grade 4, with less than 60% of the fruit surface in yellow, orange or red colors, while the fruit of the control group was at maturity index grade 5 (INTA 2013). The percentage of TSS in preharvest tomatoes treated with CCNP-CRE was statistically different (p<0.05) from the control and presented the highest values of TSS on day 30. The high percentage of TSS in tomatoes treated with CCNP-CRE indicates that the application of the coatings could be related to the high concentration of sucrose, which later formed starch in the fruit [

39]. TSS also covers organic acids and other compounds, such as minerals and amino acids [

40]. Titratable acidity expresses the presence of organic acids in the fruit mesocarp. Citric acid and malic acid are very abundant in tomato fruit [

41,

42]. High concentrations of these acids indicate the beginning of ripening [

43].

In this study, the low percentage of acidity in fruit with nanostructured coatings refers to the slow assimilation of these organic acids. Chitosan coatings reduce the respiration rate of fruit. In turn, this affects the slowness of the metabolic processes in the tomato. This occurs in the degradation of TSS, which is mediated by the respiration of the fruit [

44]. Chitosan coatings with oregano essential oil moderated the metabolism of Cherry tomatoes and therefore their flavor, given by the acid–sugar ratio, remained in balance for longer [

45]

.

Different lowercase letters between columns indicate statistical differences between the evaluation days (p<0.001). Different capital letters between rows indicate statistical differences between treatments (p<0.001).

The respiratory rate of the tomatoes treated with the nanostructured coatings had a slight decrease in contrast to the control, and it was attributed to the effect of the coatings together with the evaluation time (p<0.05). The ethylene synthesis of tomatoes reached its maximum point on day 15 of the evaluation (

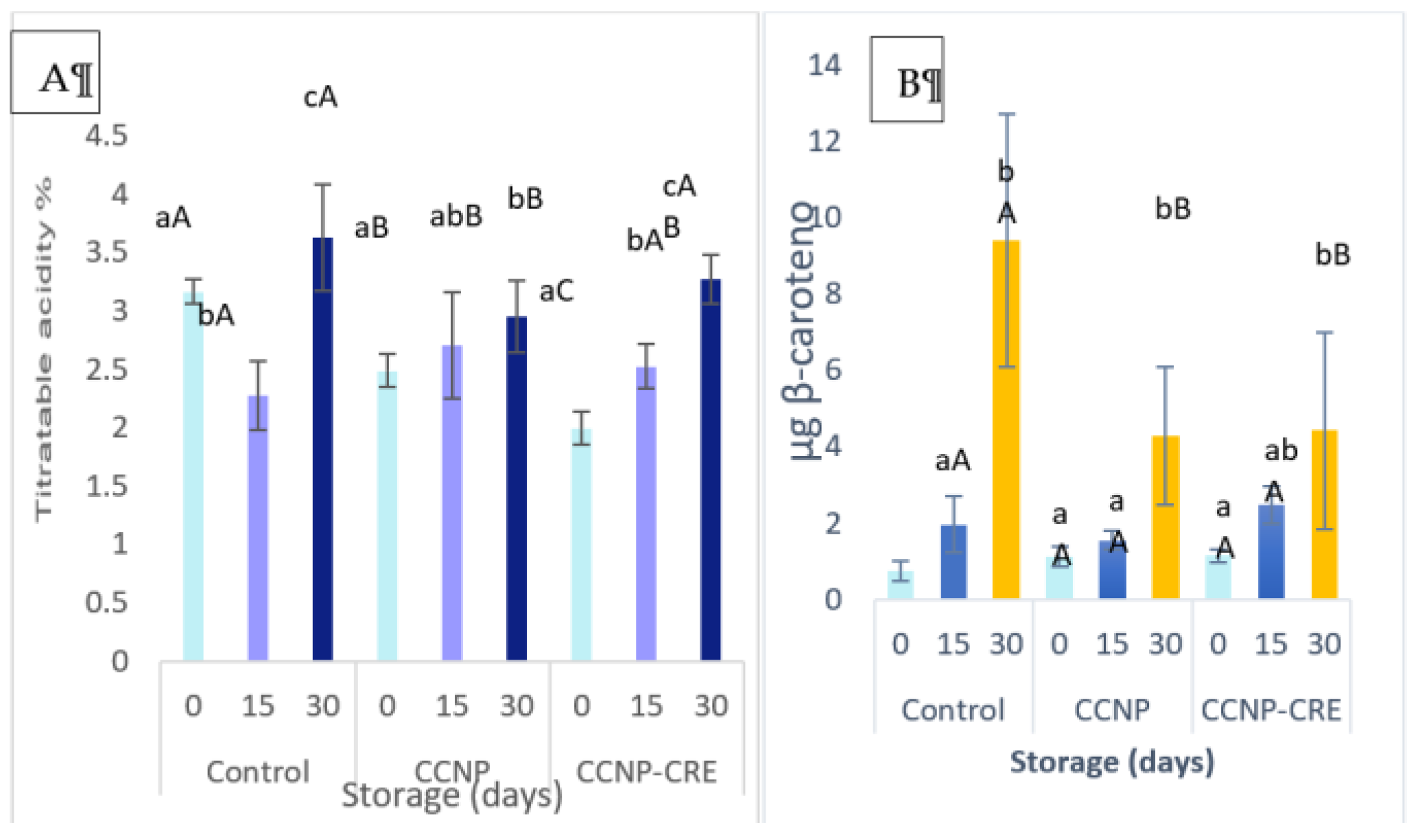

Table 4). However, on the last day of evaluation that corresponded to the fruit cutting time (maturity stage grade 4), ethylene synthesis was higher in the control group (p>0.05). On day 30 of the evaluation, the tomatoes treated with the nanostructured coatings had the percentage of titratable acidity lower and statistically different with respect to the control (p<0.05) (

Figure 5A). Regarding the evaluation time, an increase in titratable acidity was observed in all treatments. The fruit treated with both coatings exhibited a lower content of carotenoids, and it was different (p<0.05) with respect to the control (

Figure 5B).

The coloration in the tomatoes treated with CCNP-CRE was related to the low amounts of total carotenoids in the fruit compared to the control group. The synthesis of carotenoids begins with the degradation of chlorophyll and the intervention of enzymes, such as lycopene cyclases [

46]. These metabolic processes are mediated by the presence of ethylene. In this study, the results corresponding to the ethylene values in tomatoes with CCNP and CCNP-CRE were lower compared to the control, which could justify the low accumulation of carotenoids in the coated fruit. The effect of nanostructured chitosan coatings to preserve carotenoid content in tomato fruit agrees with that reported by Migliori on the retention of carotenoids when applying a chitosan solution preharvest in tomato fruit [

42]

.

3.5. Postharvest Assay

3.5.1. Effect of Coatings on the Quality and Physiological Parameters of Fruit

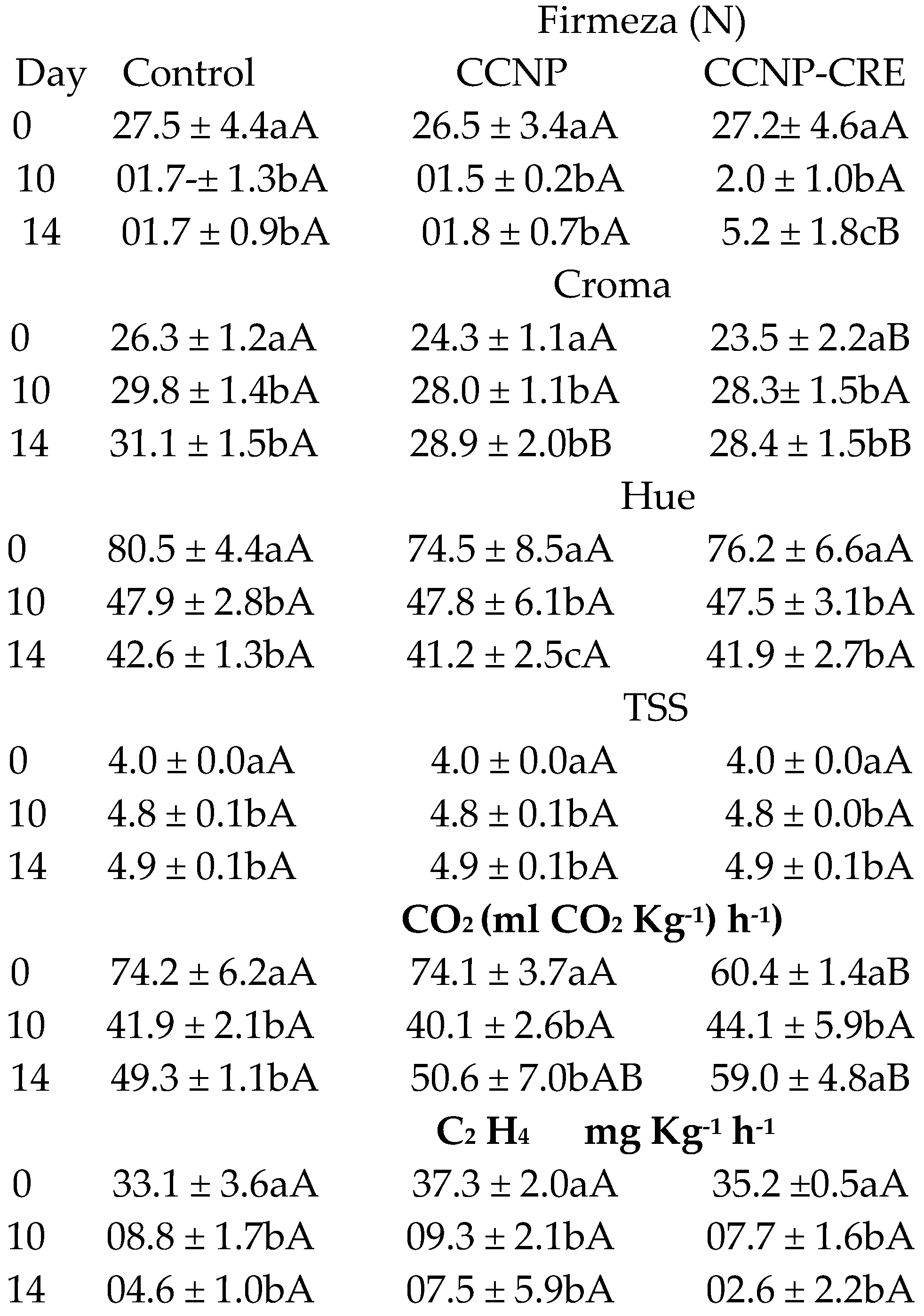

The application of the nanostructured coatings on the tomatoes did not significantly influence the percentage of weight loss of the fruit with respect to the control (p=0.1). Regarding the storage time, no significant differences (p>0.05) were observed between the control and both coatings. The firmness of the tomatoes in the postharvest stage decreased in the control group and in the nanostructured coatings (

Table 5). However, fruit covered with CCNP-CRE was firmer compared to the control (p<0.05).

In tomatoes with coatings, the color intensity (CHROMA) was lower and statistically different compared to the control (

Table 5). The values of the hue angle (Hue) decreased in the fruit control group and in the fruit with coating and were not statistically different (p>0.05). The CHROMA values increased in the fruit stored from day 10, while Hue values decreased; this is attributed to the effect of storage time (p<0.001). According to Gutiérrez-Molina et al. [

47] the color change of postharvest tomatoes was not affected by the application of treatments based on chitosan nanoparticles with nanche extract (

Byrsonima crassifolia). The TSS content of the fruit in the postharvest stage did not show differences between the treatments (F=0.163); however, the refractive index increased on days 10 and 14 due to the ripening process of the tomatoes (F=715.202) (

Table 5). Athayde et al. [

41] reported an increase in the TSS content of tomatoes with a coating of chitosan and oregano essential oil; however, the evaluation was carried out at room temperature, to which the change in TSS in the fruit could be attributed. However, chitosan coatings applied to Cherry tomatoes did not cause significant changes in TSS during fruit storage at cold temperatures [

44]. These data are similar to those obtained in this investigation.

Different lowercase letters between columns indicate statistical differences between the evaluation days (p<0.001). Different capital letters between rows indicate statistical differences between treatments (p<0.001).

The respiration rate and production of ethylene gradually decreased during storage, independently of the applied nanostructured coatings. Previous research has shown that chitosan coatings can reduce the speed of ripening by decreasing the respiratory rate of fruit, such as tangerines [

48]

, apricots [

49] and strawberries [

50]. However, nanostructured coatings combined with nanche extract (

Brysonima crossifolia) applied on tomatoes [

47] as well as the application of chitosan-surfactant nanostructures on tomatoes [

51] did not have significant repercussions (p>0.05) on the respiration rate of the fruit. A possible explanation is that due to the nanometric size, the coating was absorbed by the surface of the fruit, and this left areas without coating. Therefore, it is suggested that future research review the proportion of nanoparticles in the coating [

19].

In this investigation, the CCNP-CRE coating on the fruit in the preharvest stage reduced their respiration throughout the evaluation period (

Table 5), while in the postharvest stage, the respiration of the tomatoes treated with CCNP-CRE was higher with respect to the control (

Table 5). The application of nanostructured chitosan coatings at preharvest can delay the metabolic processes in tomatoes by controlling the rate of respiration of the fruit, which is important for increasing its shelf life. In line with these results, some authors have indicated that spraying chitosan on tomatoes in the preharvest stage preserved the physicochemical properties of fruit stored at room and controlled temperatures; therefore, their shelf life was prolonged [

52]

. A study carried out on table grapes also reported that the preharvest foliar spraying of chitosan and aloe vera increased the shelf life of the fruit [

53]

.

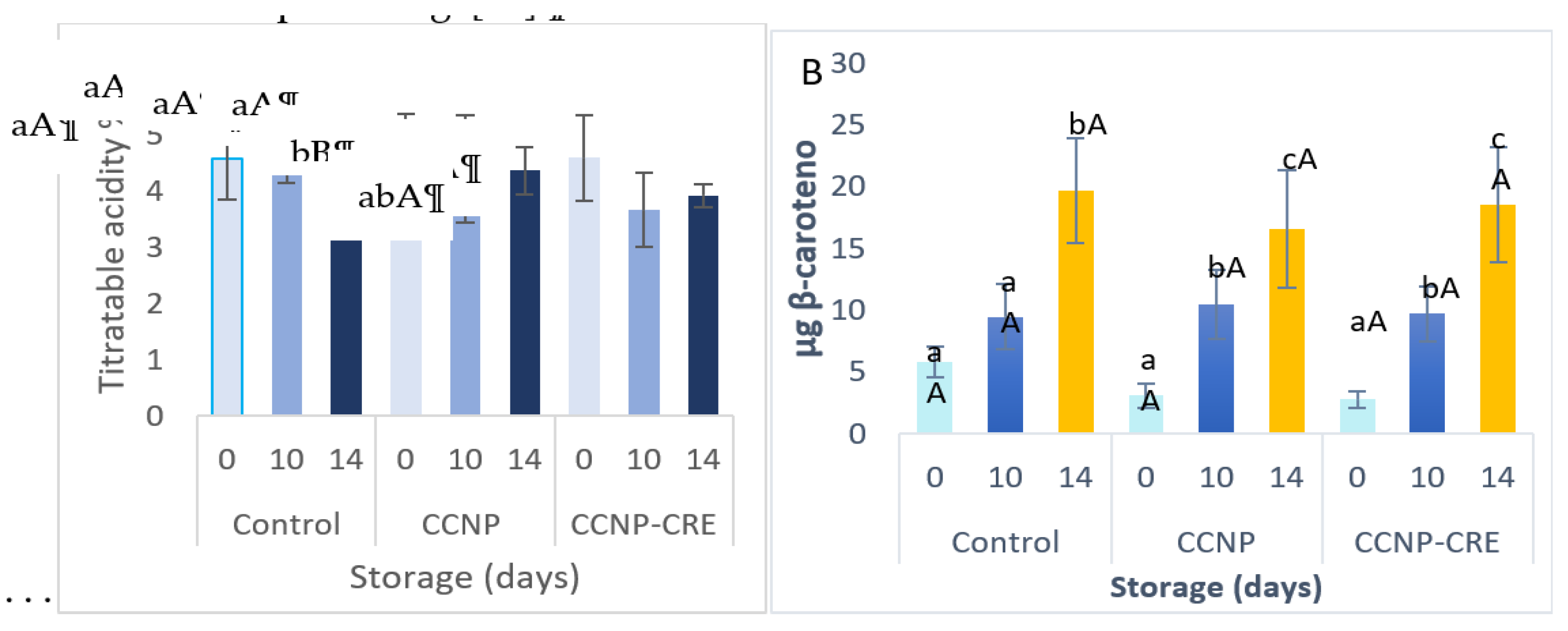

The percentage of titratable acidity in tomatoes from the control group decreased gradually (p=0.06), while the results corresponding to the treatments had no changes (

Figure 6A). According to Guerra et al. [

54] the application of chitosan coatings with the essential oil of oregano decrease in titratable acidity could be justified by the import of organic acids into the Krebs cycle (respiration). Organic acids have various destinations; they are precursors of amino with postharvest coatings decreased during cold storage (

Figure 6A); similarly, the TSS tomatoes, which is convenient because the fruit is in the consumption stage [

55]

.

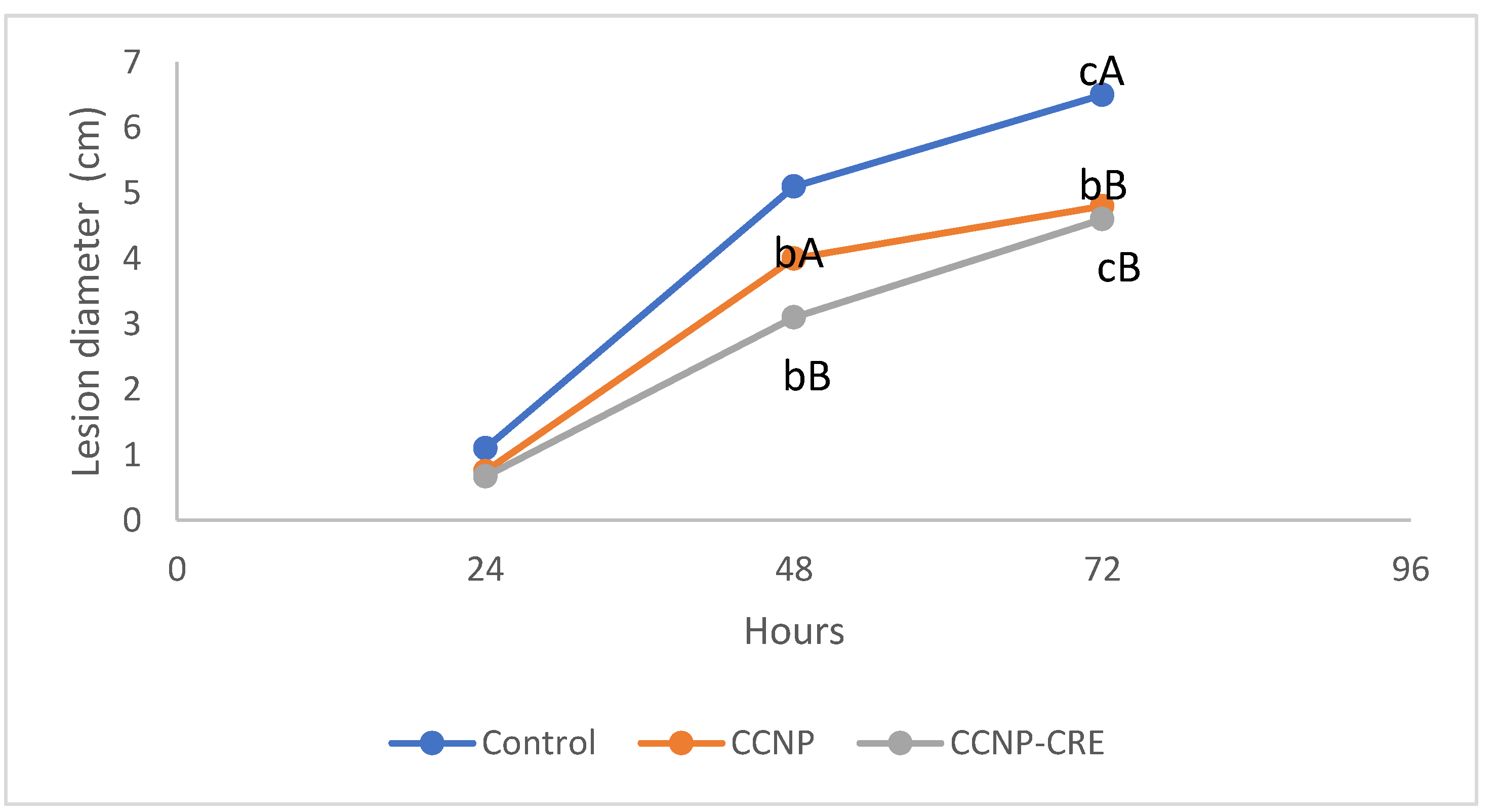

3.5.2. Incidence and Severity of Rhizopus stolonifer

The incidence of the disease in the control was 100%, in the fruit treated with CCNP was 93% and with CCNP-CRE, was 86%. The control group had the largest lesion diameter at the end of the evaluation and was statistically different from the tomatoes treated with CCNP and CCNP-CRE (p<0.05), as shown in

Figure 7. The application of CCNP-CRE reduced the incidence and severity of

R. stolonifer in tomato, which agrees with the antifungal effect observed in the in vitro study. The CCNP and CCNP-CRE coatings prevented disease development on tomatoes. Possibly the particle size distribution in the coating or the synergistic effect of chitosan and CRE was responsible for this.

Similar results have been reported by Correa Pacheco et al. [

19] for nanostructured coatings of chitosan with thyme essential oil applied in avocados cv. Hass and inoculated with

C. gloesporioides.

5. Conclusions

The lowest mycelial growth and spore germination of R. stolonifer was observed at concentrations of 5% to 10% of CRE, with inhibition of the development of the germinative tube. The average diameter of nanoparticles increased after incorporation of the coffee residue extract, and the mycelial growth inhibition was 42.7% with CNP50 CRE at 1%. During the preharvest stage, the application of both coatings showed significant differences at the end of the evaluation in the intensity of the color and exhibited a lower carotenoid content. In the postharvest stage, the application of both coatings had no effect on the quality or physiological parameters of the fruit. The use of nanostructured coatings as food preservation technology decreased the incidence of the disease (86 %) in the fruit treated with CCNP-CRE and the severity index (33%) which improve the safety and shelf life of tomatoes.

Author Contributions

Laura Leticia Barrera-Necha: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing original draft preparation, edition. Mariana Pérez Garcia and Andrea Mendoza Juárez Visualization, Investigation, Methodology. Mónica Hernández López: Methodology, Investigation. Zormy Nacary Correa-Pacheco: Supervision. Silvia Bautista Baños: Writing - reviewing.

Data Availability

The data presented in this study are available by request from the.

Corresponding author: Dra Laura Leticia Barrera Necha

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The National Polytechnic Institute, and Dr. Nicolás Cayetano Castro, Dr. Daniel Arrieta Baez to the Center for Nanoscience and Micro-Nanotechnology for its support in the TEM, HPLC/MS and FTIR analysis. Thanks also go to Dr. Eduardo San Martín from CICATA-Legaria for the DLS measurements and Dr Daniel Tapia Maruri for the micrographs obtained by laser confocal microscopy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Janissen, B.; Huynh, T. Chemical composition and value-adding applications of coffee industry by-products: A review. Resources Conservation and Recycling. 2018, 128, 110–117. [CrossRef]

- Kitzberger, C. S. G.; Scholz, M. B. S.; Pereira, L. F. P.; Benassi, M. T. Composição química de cafés árabica de cultivares tradicionais e modernas. Pesquisa Agropecuárica Brassileira. 2013, 48,1498–1506. [CrossRef]

- Kurzrock, T.; Speer, K. Diterpenes and diterpene esters in coffee. Journal Food Reviews International. 2001, 17, 433–450. [CrossRef]

- Viñas, M.; Gruschwitz, M.; Schweiggert, R.M.; Guevara, E.; Carle, R.; Esquivel, P.; Jiménez, V.M. Identification of phenolic and carotenoid compounds in coffee ( Coffea Arabica ) pulp, peels and mucilage by HPLC Electrospray Ionization Mass spectrometry. 24th International Conference on Coffee Science. Ed. Association for Science an Information on Coffee (ASIC). San Juan, Costa Rica. 2012, 127-135. [CrossRef]

- Vio-Michaelis, S.; Apablaza-Hidalgo, G.; Gómez, M.; Peña-Vera, R.; Montenegro, G.Antifungal Activity of three Chilean Plant Extracts on Botrytis cinerea. Botanical Sciences. 2012, 90, 179-183. [CrossRef]

- Iriondo-DeHond, A.; Garcia, N.A.; Fernandez-Gomez, B.; Guisantes-Batan, E.; Escobar, F.V.; Blanch, G.P. (2019). Validation of coffee by-products as novel food ingredients. Innov. Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2019, 51, 194–204. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ifset.2018.06.010.

- Pernezny, K.L.; Roberts, D.P.; Murphy, F.J.; Goldberg, P.N. Compendium of pepper diseases. A. Phytopathological Soc. 2003, 88. https://www.cabdirect.org.

- Troncoso Rojas R.; Tiznado Hernández M.R. Postharvest Decay Control Strategies Alternaria alternata (Black Rot, Black Spot) Academic Press. 2014. https://www.researchgate.net.

- Istúriz-Zapata, M.A.; Correa-Pacheco, Z.N.; Bautista-Baños, S.; Acosta-Rodríguez, J.L.; Hernández-López, M.; Barrera-Necha, L.L. Efficacy of extracts of mango residues loaded in chitosan nanoparticles and their nanocoatings on in vitro and in vivo postharvest fungal. J. Phytopathology. 2022, 170, 661-674. [CrossRef]

- Poverenov, E.; Y. Zaitsev, E.; Arnon, H.; Granit, R.; Alkalai-Tuvia, S.; Perzelan, Y.; Weinberg, T.; Fallik, E. Effects of a composite chitosan–gelatin edible coating on post- harvest quality and storability of red bell peppers. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2014, 96, 106–109. [CrossRef]

- Istúriz-Zapata, M.A.; Hernández-López, M.; Correa-Pacheco, Z.N.; Barrera-Necha, L.L. Quality of cold-stored cucumber as affected by nanostructured coatings of chitosan with cinnamon essential oil and cinnamaldehyde. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 123 109089 . [CrossRef]

- Eshghi, S.; Hashemi, M.; Mohammadi, A.; Badii, F.; Mohammadhoseini, Z.; Ahmadi, K. Effect of nanochitosan-based coating with and without copper loaded on physicochemical and bioactive components of fresh strawberry fruit (Fragaria x ananassa Duchesne) during storage. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2014, 7, 2397–2409. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, A.; Hashemi, M.; Hosseini, S.M. Chitosan nanoparticles loaded with Cinnamomum zeylanicum essential oil enhance the shelf life of cucumber during cold storage. Postharvest Biol. Technol 2015, 110, 203–213. [CrossRef]

- González-Quijano, G.; Arrieta, B.D.; Dorantes, A.L.; Aparicio, O.G.; Guerrero, L.I. (2019). Effect of extraction method in the content of phytoestrogens and main phenolics in mesquite pod extracts (Prosopis sp.). R, Mex. de Ing. Química. 2019, 18, 303–312. [CrossRef]

- Luque-Alcaraz, A.G.; Lizardi, J.; Goycoolea, F.M.; Valdez, M.A.; Acosta, A.L.; Iloki-Assanga, S.B.; Argüelles-Monal, W. Characterization and antiproliferative activity of nobiletin-loaded chitosan nanoparticles. J. Nanomaterial 2012, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Correa-Pacheco, Z.N.; Bautista-Baños, S.; Valle-Marquina, M.A.; Hernández-López, M. The effect of nanostructured chitosan and chitosan-thyme essential oil coatings on Colletotrichum gloeosporioides growth in vitro and on cv Hass Avocado and fruit quality. J. Phytopathology. 2017, 165, 297–305. [CrossRef]

- Black-Solis, J.; Ventura-Aguilar, R.I.; Barrera-Necha, L. L.; Bautista-Baños, S. Modelamiento matemático del crecimiento y la germinación de Alternaria alternata por efecto de aceites esenciales. R. Mex. Fitopatología 2017, 35, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Official Methods of Analysis. 15th edition. Ed. Washington DC. USA. 2022. https://scirp.org.

- Rodríguez-Amaya, D.B. Carotenoides y preparación de alimentos: La retención de los carotenoides, provitamina A en alimentos preparados, procesados y almacenados. Departamento de Ciencias en Alimentos, Universidad Estatal de Campinas, Brasil. 1999, 27-33. [CrossRef]

- Heeger, A.; Kosinska-Cagnazzo, A.; Cantergiani, E.; Andlauer, W. Bioactives of coffee cherry pulp and this utilisation for production of Cascara beverage. F. Chemistry 2017, 22, 969-975. [CrossRef]

- Mirón-Mérida, V.A.; Yáñez-Fernández, J.B.; Montañez-Barragán, B.E.; Barragán-Huerta. Valorization of coffee parchment waste (Coffea arabica) as a source of caffeine and phenolic compounds in antifungal gellan gum films. LWT F. Sci. Technol. 2019, 101, 167-174. [CrossRef]

- Sangta, J.; Wongkaew, M.; Tangpao, T.; Withee, P.; Haituk, S.; Arjin, C.; Cheewangkoon, R. Recovery of Polyphenolic Fraction from Arabica Coffee Pulp and Its Antifungal Applications. Plants, 2021, 10, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Cáceres, R.L.I.; Colorado, V.R.; Salas, M.E.; Muñoz, C.L.; Hernández, O.L. (2013). Actividad Antifúngica in vitro de Extractos Acuosos de Especias contra Fusarium oxysporum, Alternaria alternata, Geotrichum candidum, Trichoderma spp., Penicillium digitatum y Aspergillus niger. R. Mex. Fitopatología 2013, 31, 105-112. http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=61231509002.

- Martínez, G.; Regente, M.; Jacobi, S.; Del Rio, M.; Pinedo, M.; de la Canal, L. Chlorogenic acid is a fungicide active against phytopathogenic fungi. Pestic Biochem. Physiol. 2017, 140, 30-35 . [CrossRef]

- Lobato-Calleros, C.; Alvarado-Ambriz, S.; Hernández-Rodríguez, L.; Vernon-Carter, E. Wet processing coffee waste as an alternative to produce extracts with antifungal activity: In vitro and in vivo valorization. R. Mex. Ing. Química 2020, 19, 135-149. [CrossRef]

- Goycoolea, M.; Valle-Gallego, A. R.; Stefani, B., Menchicchi, L.; David, C., Rochas, M.; Santander-Ortega, M.A. Chitosan-based nanocapsules: physical characterization, stability in biological media and capsaicin encapsulation. Coll Poly Sci 2012, 290, 1423–1434. [CrossRef]

- Luque-Alcaraz, A.; Cortez-Rocha, M.; Velazquez-Contreras, C.; Acosta-Silva, A.; Santacruz-Ortega, H.; Burgos-Hernandez, A.; Arguelles-Monal, W.; Plascencia-Jatomea, M. Enhanced Antifungal Effect of Chitosan/Pepper Tree (Schinus molle) Essential Oil Bionanocomposites on the Viability of Aspergillus parasiticus Spores. J. Nanomat. 2016, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Barrios-Rodríguez, Y.; Collazos-Escobar, G.A.; Gutiérrez-Guzmán N. ATR-FTIR for characterizing and differentiating dried and ground coffee cherry pulp of different varieties (Coffea Arabica L.). Engenharia Agri. 2016, 41, 70-77. https://www.scielo.

- Craig, A.P.; Franca, A.S.; Oliveira L.S. Evaluación del potencial de FTIR y quimiometría para la separación entre cafés defectuosos y no defectuosos. Quim. Alime. 2012, 132, 1368-1374. https://www.scielo.pe.

- Akbar, Z.; Idroes, R.; Yusuf, M.; Karma, T.; Ginting, B.; Rahimah, S.; Tallei, T.E. Clasificación del extracto etanólico de café Gayo Arábica mediante FTIR-PCA. En Serie de conferencias IOP: Earth and Environmental Science 2021, 66 12-41. [CrossRef]

- Cortés, C.A.M.; Guzmán, N.G. Evaluación del proceso de clasificación de café (Coffee arabica L.) por el método de la espectroscopia infrarroja FTIR. Ing. Región 2018, 19, 12-17. [CrossRef]

- Peñuelas-Rubio, O.; Arellano-Gil, M.; Vargas-Arispuro, I.C.; Lares-Villa, F.; Cantú-Soto, E.U.; Hernández-Rodríguez, S.E.; Gutiérrez-Coronado, M.A.; Mungarro-Ibarra C. Bioactividad in vitro de extractos de gobernadora (Larrea tridentata) sobre la inhibición de hongos poscosecha: Alternaria tenuissima, Aspergillus niger, Penicillium polonicum y Rhizopus oryzae. Polibotánica 2015, 40, 183-198. [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Hernández, M.A.; Barrera-Necha, L.L.; Hernández-Lauzardo, A.N.; Velázquez del Valle M.G. Actividad antifúngica del quitosano y aceites esenciales sobre Rhizopus stolonifer (Ehrenb.:Fr.) Vuill., agente causal de la pudrición blanda del tomate. R. Colom. Biotec. 2011, 2, 127-134. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, D.M.; Santos, P.L.; Kronka, A.Z. (2019). Essential oils inhibit Colletotrichum gloeosporioides spore germination. Summa Phytopathol 2019, 45, 432–433. [CrossRef]

- Andrade-Bustamante, G.; García, L.A.M.; Cervantes, D.L.; Aíl, C.C.E.; Borboa, F.J.; Rueda P.E.O.; Estudio del potencial biocontrolador de las plantas autoctonas de la zona arida del noroeste de Mexico: control de fitopatogenos. Revista FCA 2017, 49, 127–142.

- María Alejandra Istúriz-Zapata, Zormy Nacary Correa-Pacheco, Silvia Bautista-Baños, JoséLuis Acosta-Rodríguez, MónicaHernández-López, LauraLeticiaBarrera-Necha. Efficacy of extracts of mango residues loaded in chitosan nanoparticles and their nanocoatings on in vitro and in vivo postharvest fungal. Journal of Phytopathology 2022, 170:661-674 00. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Lauzardo, A.N.; Velázquez-del Valle, M.G.; Veranza-Castelán, L.,;Melo-Giorgana, G.E.; Guerra-Sánchez, M.G. Effect of chitosan on three isolates of Rhizopus stolonifer obtained from peach, papaya and tomato. Fruits 2010, 65, 245-253. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Téllez, C.; Plascencia-Jotomea, M.; Cortez-Rocha, M. (2016). Chitosan-Based Bionanocomposites: Development and Perspectives In Food and Agricultural Applications. 315-338. En: Bautista-Baños S., Romanazzi G. y Jiménez-Aparicio A. (eds.). Chitosan in the Preservation of Agricultural Commodities. Academic. Academic Press. 2016, 366. [CrossRef]

- Beckles, D.M. Factors affecting the postharvest soluble solids and sugar content of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) fruit. Posth. Biol. Technol. 2012, 63, 129-140. [CrossRef]

- Kader, A.A. Flavor quality of fruits and vegetables. J. Sci. Food and Agri. 2008, 88, 1863-1868. [CrossRef]

- Athayde, A.J.A.A.; De Oliveira, P.D.L.; Guerra, I.C.D.; Da Conceicao, M.L.; De Lima, M.A.B.; Arcanjo, N.M.O.; De Souza E.L. A coating composed of chitosan and Cymbopogon citratus (Dc. Ex Nees) essential oil to control Rhizopus soft rot and quality in tomato fruit stored at room temperature. J. Hort. Sci. Biotech 2016, 91, 582-59. [CrossRef]

- Migliori, C.A.; Salvati, L.; Di Cesare, L.F.; Scalzo, R.L.; Parisi M. Effects of preharvest applications of natural antimicrobial products on tomato fruit decay and quality during long-term storage. Sci. Horti. 2017, 222, 193-202. [CrossRef]

- Famiani, F.; Battistelli, A.; Moscatello, S.; Cruz-Castillo, J.G.; Walker R.P. Los ácidos orgánicos que se acumulan en la pulpa de las frutas: ocurrencia, metabolismo y factores que afectan su contenido una revisión. R. Chap. S. Horti. 2015, 21, 97-128. [CrossRef]

- D’Aquino, S.; Mistriotis, A.; Briassoulis, D.; Di Lorenzo, M.L.; Malinconico, M.; Palma A. Influence of modified atmosphere packaging on postharvest quality of cherry tomatoes held at 20◦C. Postharvest Biology and Technology 2016, 115, 103–112. [CrossRef]

- Barreto, T.A.; Andrade, S.C.; Maciel, J.F.; Arcanjo, N.M.; Madruga, M.S.; Meireles, B.; Magnani M. A chitosan coating containing essential oil from Origanum vulgare L. to control postharvest mold infections and keep the quality of cherry tomato fruit. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1724. [CrossRef]

- Fraser, P.D.; Truesdale, M.R.; Bird, C.R.; Schuch, W.; Bramley, P.M. Carotenoid biosynthesis during tomato fruit development (evidence for tissue-specific gene expression). Plant physiology 1994, 105, 405-413. [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Molina, J.; Corona-Rangel, M.L.; Ventura-Aguilar, R.I.; Barrera-Necha, L.L.; Bautista-Baños, S.; Correa-Pacheco, Z.N. Chitosan and Byrsonima crassifolia-based nanostructured coatings: Characterization and effect on tomato preservation during refrigerated storage. Food Biosci 2021, 42, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Baggio, J.S.; Gonçalves, F.P.; Lourenço, S.A.,;Tanaka, F.A.O.; Pascholati, S.F.; Amorim L. Direct penetration of Rhizopus stolonifer into stone fruits causing rhizopus rot. Plant Pathol 2016, 65, 633-642. [CrossRef]

- Gull , A.; Bhat, N.; Wani, S.M.; Masoodi, F.A.,;Amin, T.; Ganai S.A. Shelf life extension of apricot fruit by application of nanochitosan emulsion coatings containing pomegranate peel extract. Food Chem. 2021, 349, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Velickova, E.; Winkelhausen, E.; Kuzmanova, S.; Alves, V.D.; Moldão-Martins M. Impact of chitosan-beeswax edible coatings on the quality of fresh strawberries (Fragaria ananassa cv Camarosa) under commercial storage conditions. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2013, 52, 80–92. [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, M.A.; Ali, A.; Manickam, S.; Siddiqui, Y. Ultrasound-assisted chitosan-surfactant nanostructure assemblies: Towards maintaining postharvest quality of tomatoes. Food Biopro. Technol. 2014, 7, 2102–2111. [CrossRef]

- Almunqedi, B.; Kassem, H.; Almunqedhi, B.M.; Kassem, H.A.; Al-Harbi A.E.A.R. Effect of preharvest chitosan and/or salicylic acid spray on quality and shelf-life of tomato fruits. J. Sci. Engi. Res. 2017, 4, 114-122. https://www.researchgate.net.

- Nia, A.E.; Taghipour, S.; Siahmansour, S. Pre-harvest application of chitosan and postharvest Aloe vera gel coating enhances quality of table grape (Vitis vinifera L. cv. ‘Yaghouti’) during postharvest period. Food Chem. 2021, 347, 129012. [CrossRef]

- Guerra, I.C.D.; de Oliveira, P.D.L.; de Souza, A.L.; Lúcio, A.S.S.C.; Tavares, J.F.; Barbosa-Filho, J.M.; de Souza E.L. Coatings comprising chitosan and Mentha piperita L. or Mentha× villosa Huds essential oils to prevent common postharvest mold infections and maintain the quality of cherry tomato fruit. Inter. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 214, 168-178. [CrossRef]

- Peralta-Ruiz, Y.; David, C.; Tovar, G.; Sinning-Mangonez, A.; Coronell, E.A.; Marino, M.F.; Chaves-Lopez, C.C. Reduction of Postharvest Quality Loss and Microbiological Decay of Tomato “Chonto” (Solanum lycopersicum L.) Using Chitosan-E Essential Oil-Based Edible Coatings under Low-Temperature Storage. Polymers 2020, 12, 1-22. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).