Introduction

Central part of this anatomical study is to clarify the course of the superior epigastric artery (SEA). Starting point is an obvious and unexplained discrepancy between the topographic relations presented in anatomical specimens and the generally represented German-language textbooks opinion.

In nature, the SEA is a vessel of the chest and abdominal wall. As one of the terminal branches of the internal thoracic artery it commences in the angle between the ribs and transversus thoracis muscle. To reach the ventral aspect of the dorsal wall of the rectus sheath, it continues in the same layer and thus enters the anterolateral abdominal wall. In a highly variable manner, within the rectus abdominis muscle it anastomoses with the inferior epigastric artery.[

1,

2]

In contrast to these established facts, some German textbooks suggest that the superior epigastric artery (SEA) passes through the sternocostal triangle (Larrey's fissure) of the diaphragm [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].This gap represents a weak region between the sternal and costal parts of the diaphragm and connects the pleural cavity with the peritoneal cavity. Therefore, embryological as well as topographic anatomical considerations lead to the conclusion that this course has to be considered as unrealistic. Our study carried out in a significant number of anatomic specimens (N= 40) has revealed that these textbook views are really misleading.

In addition, by exact study of anatomy books published since the days of Dominique Larrey we have found that unexpectedly, but obviously Joseph Hyrtl [

14,

15,

16] has created this erroneous description. In contrast to his remaining and generally outstanding work he slipped in some misunderstanding of the original description given by Larrey who has definitely stated that the sternocostal tiangle is a space "free of any vessels".[

17] However, because a SEA passing through Larrey's fissure could potentially resemble a rare anatomical variation, this description has also been carefully considered to ensure accuracy.

Material and Methods

This study is based on anatomical specimens from 40 voluntary body donors. The thoracic and abdominal walls were dissected layer by layer, and the course of the SEA was meticulously documented. The focus was exclusively on the anterior part of the thoracoabdominal wall and the anterior insertions of the diaphragm.

Our study included 40 individuals of both genders. These are formalin-fixed anatomical specimens from donors who voluntarily and with compensation provided their bodies to the Center for Anatomy and Cell Biology at the Medical University of Vienna for educational and research purposes. A sample of the last will and testament used for this purpose can be found in the appendix of this thesis. This project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Vienna. The study was conducted during the anatomical dissection courses, specifically the mandatory course "Organ Morphology”.

For the fixation and preservation of the anatomical specimens, a perfusion fixation is first applied. A solution of 4% phenol and 0.5% formalin (37% formaldehyde in aqueous solution) is infused via the femoral artery (usually on the right) under hydrostatic pressure. This perfusion typically lasts around 12 to 24 hours. Subsequently, the cadavers are immersed in a solution of 4.5% phenol and 0.9% formalin for at least 9 months to ensure sufficient tissue penetration despite the low concentration of preservatives, thereby providing protection against infections.

Results

The Anatomic Results

The internal thoracic artery (ITA) arises from the subclavian artery as its sole branch from the caudal side. The origin of the ITA is covered by the internal jugular vein. It then descends obliquely to the first rib and is positioned between the subclavian vein (ventrally) and the pleural dome (dorsally). At this level, the phrenic nerve typically runs along its lateral side, crossing it either ventrally or dorsally and then continues parallel to it. The vagus nerve runs approximately 2-3 cm lateral to the ITA. As the artery continues its vertical descent, it reaches the anterior wall of the thorax, where it runs parallel to the sternum at a distance of about 1 cm, aligning itself with the inner surface of the costal cartilages. Thus, it lies dorsally to the costal cartilages and intercostal spaces, and ventrally to the endothoracic fascia and parietal pleura. In each of the upper five or six intercostal spaces, the ITA gives off anterior intercostal arteries to the intercostal spaces. Thin, fine branches called perforating branches (ventral cutaneous branches) emerge from within to reach the skin of the chest wall. The ITA also gives off other important branches, namely the mediastinal branches to the mediastinum, sternal branches to the sternum, and a long branch, the pericardiacophrenic artery, which supplies the muscular parts of the diaphragm.

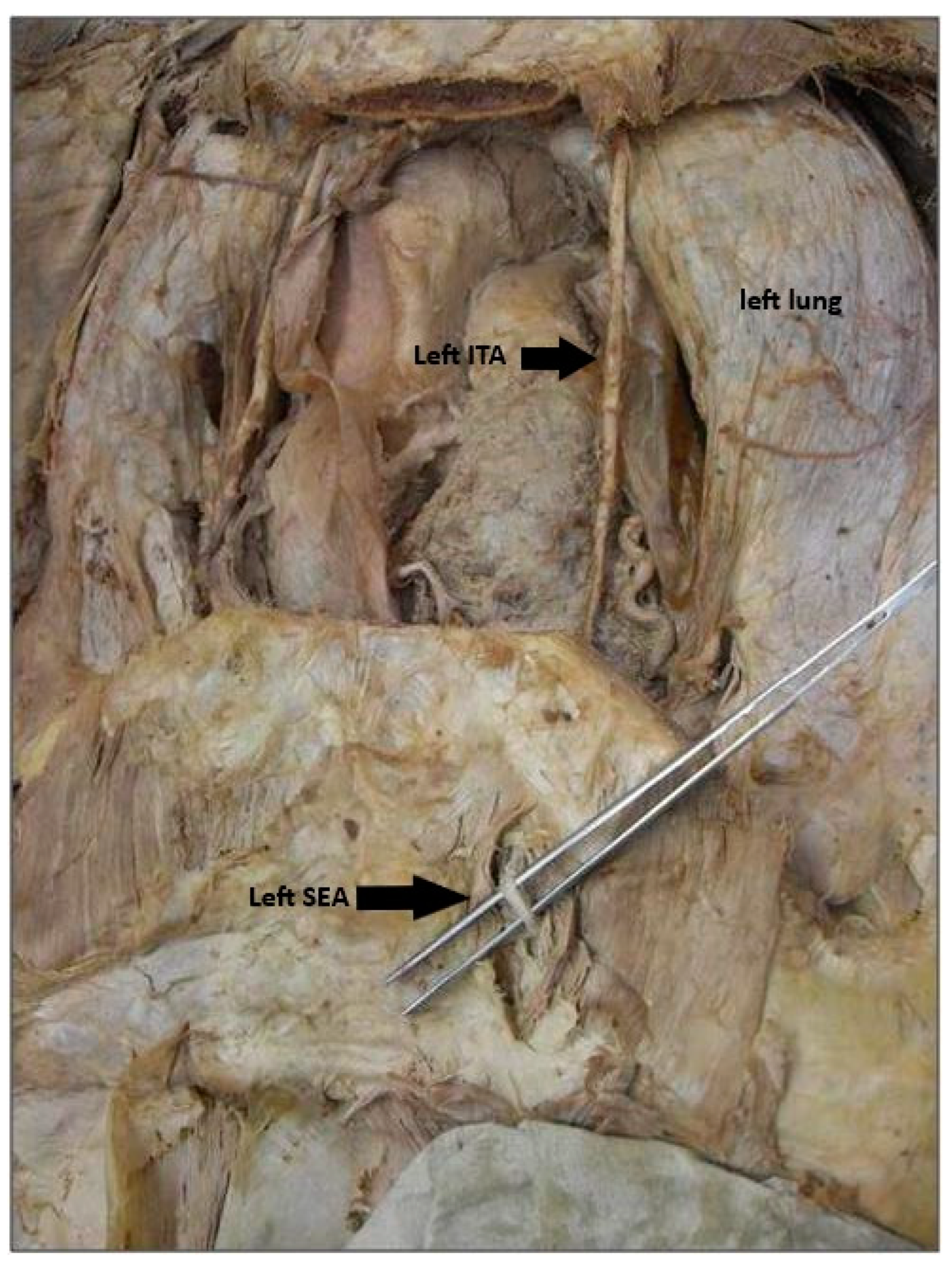

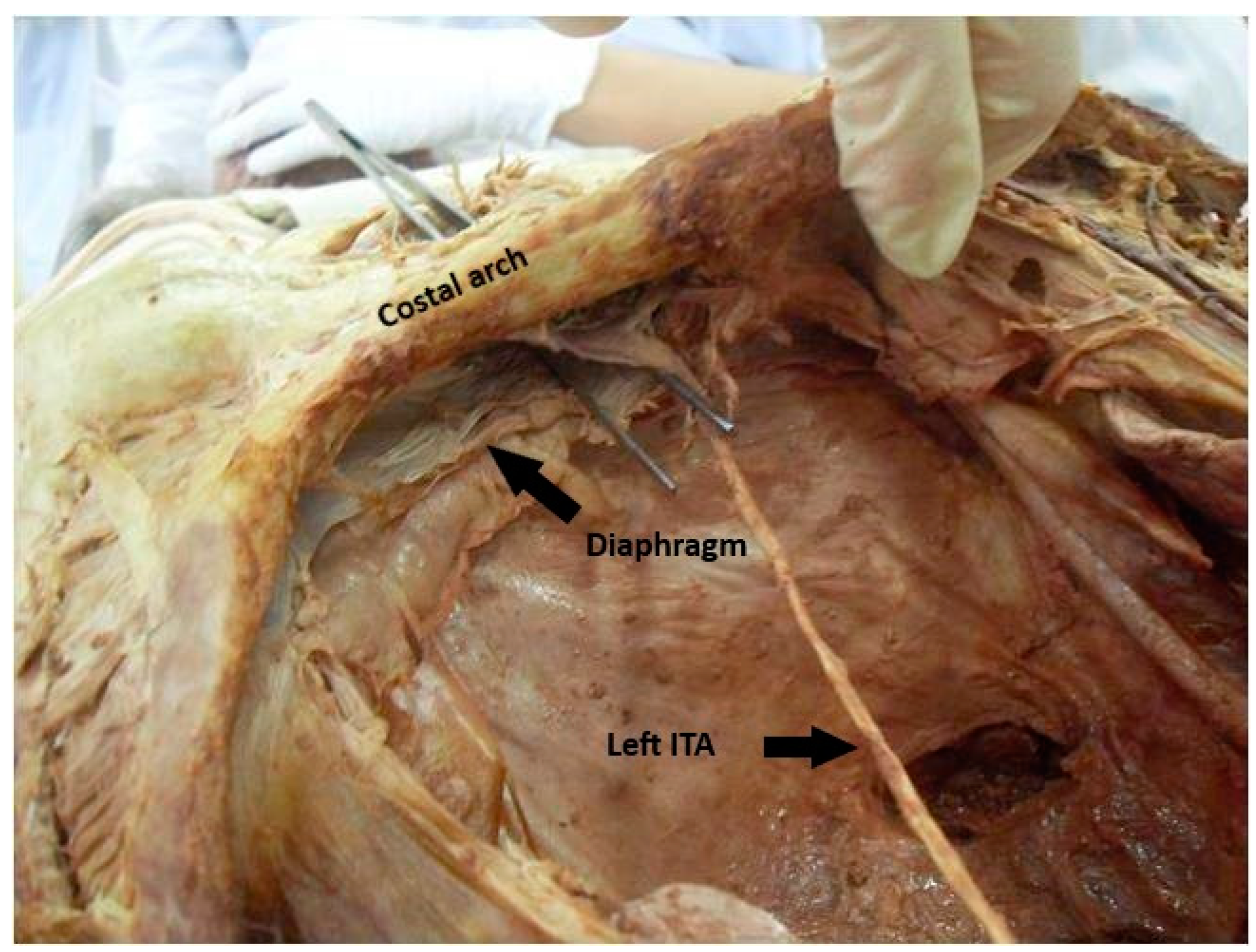

In half of the individuals we studied n=20, the internal thoracic artery divides at the level of the sixth rib, while in the other half n=20, it divides at the level of the seventh rib into its two terminal branches, the SEA and the musculophrenic artery. The musculophrenic artery runs laterally along the last costal cartilage, travels a variable distance within the muscular layer of the diaphragm, which it supplies, and terminates at the 10th rib. The SEA continues the course of the ITA

Figure 1. It passes between the costal arch and the transversus thoracis muscle to enter the rectus sheath

Figure 2. There, it initially runs ventral to the posterior layer of the rectus sheath, which is formed cranially by the transversus thoracis muscle and later by the transversus abdominis muscle. At a variable height, it enters the dorsal surface of the rectus abdominis muscle and anastomoses within this muscle with the inferior epigastric artery.

Literature Rewiev

The first response regarding the misinterpretation of the course of the SEA was published by Kubik and Steiner in 1973 in the

Swiss Journal of the History of Medicine and Sciences.[

18] Like in German anatomy textbooks, in the French literature, there are also discrepancies, as highlighted by the study of Baudoin et al.[

19]

JEAN-DOMINIQUE LARREY (1766-1842), the greatest French military surgeon of his time, published his collected surgical experiences in the work "Surgical Clinic." In the chapter "On Wounds of the Pericardium and the Heart," he describes new approaches to opening the pericardium in cases of effusion. [

20]

The first anatomist to mention Larrey was Joseph HYRTL (1811-1894). In his "Textbook of Human Anatomy" from 1846, he writes in the chapter on the diaphragm: "Between the costal segment that originates from the 7th rib cartilage and the one that arises from the xiphoid process, there exists a triangular gap through which the pleura and peritoneum come into contact.[

14] Larrey advised puncturing the pericardium through this gap." A year later, in his "Handbook of Topographical Anatomy" (1847), Hyrtl states: "According to Larrey, there is a gap which he recommended for performing pericardial puncture."[

15] The decision to associate Larrey's name with this triangular muscle-free zone was made 13 years later, in the 4th edition of Hyrtl's Topographical Anatomy[

16]. In this edition, a new chapter titled "Larrey's Diaphragmatic Space" was introduced, where it is stated: "Between the bundles of the diaphragm that originate on either side from the xiphoid process and the 7th rib cartilage, there is, according to Larrey, a gap that is covered or closed from below by the peritoneum and from above by the pericardium." [

18]

The first transmission of the name "Larrey's Diaphragmatic Space" for the sternocostal triangle, as coined by Hyrtl, was made by Mihalkovics from Budapest in 1888, an anatomist from the Vienna School.[

20] He was followed by Merkel (1899) [

21] and Joessel-Waldeyer (1899)[

22]. However, the majority of authors at that time did not even mention Larrey's name. Then, the situation suddenly changed, and from around 1900, we find the term "Larrey's Space" being used as a synonym for the sternocostal triangle in almost all German-language anatomy textbooks.[

18] Although Larrey was Napoleon's military surgeon, interestingly, his name does not appear in French anatomical literature in this context until as late as 1930.[

23,

24,

25] This example illustrates that the content of most books, even today, is still heavily influenced by preceding literature in the same language.

Among French authors, similar disagreements and controversies can be found in anatomical literature, with some also suggesting that the superior epigastric artery passes through Larrey's diaphragmatic space.[

26,

27] In contrast, Netter (in the French version) holds a different view, correctly asserting that the superior epigastric artery runs between the costal arch and the transversus abdominis muscle.[

28,

29]

Unfortunately, Hyrtl's description does not clarify whether he referred to the sternocostal triangles on both sides of the body under the term "Larrey's space" or only to the left-sided weakness through which Larrey originally described his access to the pericardium. The latter seems likely since Hyrtl described the space as "covered or closed from below by the peritoneum and from above by the pericardium." [

16] In most anatomical textbooks published since then, Larrey's space is described as the passage for the paired superior epigastric vessels.[

18]

In 1957, surgeons Zenker and Grill [

30] named the right-sided triangle after Morgagni and the left-sided one after Larrey. They explained that the right diaphragmatic hernia was named after Morgagni in 1761 due to a hernia he found during an autopsy at this site. Thus, it entered the literature as the "Morgagni hernia." Interestingly, Morgagni actually described the occurrence of diaphragmatic hernias in both sternocostal triangles.[

18,

31]

Regarding the vessels passing through this area, various terms are found in the literature. While Luschka (1863)[

32], Merkel (1899)[

21], and Joessel-Waldeyer (1899)[

22] identified the "Vasa mammaria interna," or the internal thoracic artery (ITA), in this space, more recent textbooks (such as Eisler in 1912[

33], Sieglbauer in 1927[

34], and Schubert in 1964[

35]) describe the transition of the internal thoracic artery into the superior epigastric vessels in Larrey's space.[

18]

From the facts just described, we can conclude that the error regarding "the internal thoracic artery or its abdominal terminal branch, the superior epigastric artery, passing through the sternocostal triangle" does not originate with Larrey. On the contrary, he described during his operation that "no significant vessel is encountered along this entire route." Hyrtl, who first referred to the space as "Larrey's space," also did not explicitly mention the presence of vessels in this weak spot. The first mistaken connection between these anatomical facts seems to have been made by Luschka in 1863, as he wrote: "The size of these gaps filled with loose, fatty tissue between the sternal and costal parts, through which the internal thoracic artery takes its course..." He also referenced Larrey, stating that "on the right side, this triangular space is covered by the pleura, whereas on the left it is free and can therefore be used for pericardial puncture according to Larrey's method."[

18]

In Friedrich Merkel's textbook from 1899[

21], it is stated unequivocally: "There are two weak spots that are only closed by loose connective tissue: the space between the sternal and costal portions, Larrey's space, and the space between the costal and vertebral portions. The former abuts the pleura on the right and the pericardium on the left. Through these, the internal thoracic vessels enter the abdominal cavity." This interpretation was subsequently adopted by all authors.[

18]

Formularbeginn

Formularende

Discussion

Our results are consistent with the findings of studies by Ludwig[

36], Gurriet, and Thevenat[

37], who as early as 1955 pointed out the incorrect representation in anatomy textbooks. Interestingly, these publications have so far not been acknowledged by the authors and editors of German-language anatomical works; in all the standard textbooks, the false description of the course of the superior epigastric artery through Larrey's space persists. These authors [

3,

13] overlook the fact that, for this to be true, the vessel would have to cross from the thoracic cavity into the abdominal cavity. This would mean that it would run along the anterior surface of the liver on the right side and more or less "freely" in front of the stomach on the left side. Such courses are simply impossible, especially since a separate ventral mesentery would have to develop for this intra-abdominal vessel. This entire description is therefore absurd. The internal thoracic artery and its direct continuation, the superior epigastric artery, are vessels of the chest and abdominal wall that run ventral to the pleural and peritoneal cavities.

In American and Japanese literature (such as in Gray[

38] and Okajima[

39]), the correct description can sometimes be found. Similarly, in classic anatomical textbooks, which are still largely in Latin (like those of Vesalius[

40] and Verheyen[

41]—the latter also in German, being the first German-language anatomy textbook from 1708), the accurate details are also present. Of particular significance in this comparison is Verheyen's anatomy textbook, written in its original Latin version[

42]. The logical and clear interpretation of the course of the internal thoracic artery and the superior epigastric artery is evident when reading this work from 1699.

Our literature review revealed that Larrey himself had nothing to do with this misconception. Instead, it appears to have originated from Friedrich Merkel's textbook[

21], where—contrary to his usual precise observations—he made an evident translation and interpretation error. Several decades later, anatomists Ludwig[

36], Guerrier, and Thevenat[

37] simultaneously attempted to correct this description in their publications. Unfortunately, few have followed their anatomically accurate observations to this day.

In this anatomical study, I was able to determine that there are generally no gaps or potential openings between the sternal and costal parts of the diaphragm. We have also repeatedly emphasized that Larrey did not penetrate the diaphragm when performing a pericardial puncture. The parts of the diaphragm we have been discussing are not gaps or openings, but rather sections where the diaphragm is formed by connective tissue fibers rather than muscle.

Furthermore, Kubik and Steiner[

18] were able to demonstrate in their study that the misleading description found in anatomical textbooks resulted from a chain of misinterpretations and citations. It was highly interesting to trace this chain of arguments back over more than a hundred years and to observe the often differing interpretations by the same authors at various points and in different editions of their works. Additionally, it is quite surprising that, after nearly five hundred years of the history of scientific human anatomy (since Vesalius' "Fabrica" in 1543)[

40], there are still "gaps" in a field often considered "complete."

Conclusions

We can conclude that there is no apparent reason for the course of the superior epigastric artery through the so-called Larrey's space, i.e., the sternocostal triangle of the diaphragm. We did not observe any such anatomical variation in our study, nor are there any publications on this topic. The erroneous description, which has been perpetuated in German-language anatomy textbooks for almost 200 years, can be traced back to an evidently incorrect combination of various anatomical facts by Friedrich Merkel in 1899. Although Ludwig in 1955 and Kubik and Steiner in 1973 have already pointed this out, little has changed to this day.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Loukas, Marios., Tubbs, Shane R., Benninger, Brion. GRAY'S Klinischer Fotoatlas Anatomie: Anleitung zum Präparieren. Deutschland: Urban & Fischer, 2023. Page 194.

- Terfera, David., Jegtvig, Shereen. Anatomie für Dummies. Deutschland: Willey, 2022.

- Sobotta Lehrbuch Anatomie. Deutschland: Urban & Fischer, 2019. Page 94.

- Aumüller, Gerhard., Aust, Gabriela., Conrad, Arne., Engele, Jürgen., Kirsch, Joachim., Maio, Giovanni., Mayerhofer, Artur., Mense, Siegfried., Reißig, Dieter., Salvetter, Jürgen., Schmidt, Wolfgang., Schmitz, Frank., Schulte, Erik., Spanel-Borowski, Katharina., Wennemuth, Gunther., Wolff, Werner., Wurzinger, Laurenz J.., Zilch, Hans-Gerhard. Duale Reihe Anatomie. Deutschland: Georg Thieme Verlag, 2020 Page 321.

- Maier, Hans., Winkelmann, Andreas. Präparierkurs: Präparieranweisungen und Theorie. Deutschland: Lehmanns Media, 2024. Page 77.

- Taschenbuch Anatomie. Deutschland: Urban & Fischer, 2020 Page 149.

- Sobotta, Atlas der Anatomie des Menschen Band 1: Allgemeine Anatomie und Bewegungsapparat. Deutschland: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2022 Page 162.

- Krenek, Beate. Atem-Physiotherapie. Deutschland: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2023 Page 6.

- Waldeyer, Anton. Waldeyer - Anatomie des Menschen: Lehrbuch und Atlas in einem Band. Deutschland: De Gruyter, 2012 Page 431.

- Pschyrembel, Willibald. Pschyrembel Klinisches Wörterbuch: Mit klinischen Syndromen und Nomina anatomica. Deutschland: De Gruyter, 2022 Page 924.

- Kretz, Oliver. Sobotta Malbuch Anatomie. Deutschland: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2021 Page 88.

- Bauer, Robin., Wolfram, Sandro. Palpationsatlas. Deutschland: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2022 Page 146.

- Corts, Magga. Set Anatomie für Osteopathen. Deutschland: Thieme, 2023 Page 62.

- HYRTL J, Lehrbuch der Anatomie des Menschen, F Ehrlich, Prag 1846, Seite 312.

- HYRTL J, Handbuch der topographischen Anatomie, J.B. Wallishauser, Wien 1847, Band 1, Seite 399-400.

- HYRTL J, Handbuch der topographischen Anatomie, 4.Auflage, W. Braumüller, Wien 1860, Seite 541.

- J.-D. LARREY „Chirurgische Klinik“ übersetzt von A. Sachs, C.F. Amelang, Berlin 1831, Band 2, Seiten 247-248, 257-261.

- KUBIK ST, STEINER R, „Die Larreysche Spalte, eine anatomische Fehlinterpretation“, Gesnerus 1973, Volume 30, Verlag Sauerländer Aarau, Seiten 150-159.

- BAUDOIN, Y.-. P, HOCH M, PROTIN X.-M, OTTON B.-J, GINON B, VOIGLIO E.-J, „The superior epigastric artery does not pass through Larrey`s space (trigonum sternocostale), Surg Radiol Anat 2003 25: Seiten 259-262.

- MIHALKOVICS G, „A leiro emberbonctan es tajbonctan tankönyve“, Franklin Tarsulat, Budapest (1888), Seiten 431, 945.

- MERKEL F, „Handbuch der topographischen Anatomie“, Vieweg, Braunschweig 1899, Seiten 338-339, 446.

- JOESSEL G,WALDEYER W, „Lehrbuch der topographisch-chirurgischen Anatomie“, Fr. Cohen, Bonn 1899, S. 39-40, 45.

- TESTUT L, LATARJET A, „Traite d`anatomie humaine“,tomes I, II, Doin 1948, Paris.

- HOVELACQUE, P. , MONOD O, EVRARD H: „Le Thorax“, Anatomie Medico-Chirurgicale. Librarie Maloine, Paris, I937.

- PATURET G, „Traite d`anatomie humaine“, T.2. Masson (1951), Paris.

- ROUVIERE H, DELMAS A, „ Anatomie humaine“, 2. Teil, 13. Auflage (1992) Masson, Paris, Seite 115.

- BOUCHET A, CUILLERET J „Anatomie humaine“, 2. Teil, 2.Auflage. (1991) Simep, Lyon, Seite 107.

- NETTER FH „Atlas d’anatomie humaine. Maloine“ (1997), Paris, Seite 236.

- BAUDOIN, Y.-. P, HOCH M, PROTIN X.-M, OTTON B.-J, GINON B, VOIGLIO E.-J, „The superior epigastric artery does not pass through Larrey`s space (trigonum sternocostale), Surg Radiol Anat 2003 25: Seiten 259-262.

- ZENKER R, GRILL W, „Die Eingriffe bei den Bauchbrüchen, einschliesslich der Zwerchfellbrüche“, In : GULEKE-ZENKER (Hg.), Allgemeine und spezifische chirurgische Operationslehre, Springer, Berlin 1957, Band 7, S.198, 232.

- MORGAGNI, G. B, De sedibus et causis morborum, Typog. Remondiniana, Venetiis 1761, 2 Vol, ins Französische übersetzt von M.A. DESOMERAUX und S.P. DESTOUET, Bechet, Paris 1823, Tome 7, S 493.

- LUSCHKA H, Die Anatomie des Menschen, H.Laupp, Tübingen 1863, S.158.

- EISLER P, „ Die Muskeln des Stammes „ In Bardeleben (Hrsg) Handbuch der Anatomie des Menschen“, 2. Band, Gustav Fischer Verlag Jena,(1912).

- SIEGLBAUER F, „Lehrbuch der normalen Anatomie des Menschen“, Urban-Schwarzenberg, Wien 1927, S 267, 587.

- SCHUBERT J, Topographische Anatomie, J.A. Barth, München 1964, S.65.

- LUDWIG K.S, „Die Beziehung der Arteria epigastrica cranialis zum Zwerchfell und zu den Musculi transversi thoracis et abdominis“, Acta Anat. 25 (1955) 85-91.

- GUERRIER Y, THEVENAT A, „Les insertions anterieures du diaphragme“, C.R.Ass Anat 86 (1955), 807-812.

- WILLIAMS P.L, BANNISTER L.H, BERRY M.M, COLLINS P, DYSON M, DUSSEK J.E, FERGUSON M.W.J, „GREY`S „Anatomy“; 38. Auflage, Verlag Churchill Livingstone, New York Edinburgh London Tokyo Madrid and Melbourne (1995),Seiten 814-817, 1534-1535.

- OKAJIMA K, „Anatomie“ , Keio Universität, Tokyo, Tohodo, Hongo (1933), Seite 734.

- VESALIUS, A. De Corporis Humani Fabrica Libri Septem. Liber II. Ligamentis. Ossa. Cartilaginesque Invicem. Nachdruck bei Anton et Jacob de Franciscis, Venedig (1604), Seiten 218-222.

- VERHEYEN PH, „Anatomie oder Zerlegung des Menschlichen Leibes“, (Aus dem lateinischen übersetzt, Druck nach dem Original von 1708, ) Antiqua Verlag Lindau (1981), Seiten 66-72, 254-270.

- VERHEYEN PH, „Corporis humani anatomia“, Autore Philippo Verheyen in Universitate Lovaniensi Anatomiae Professore Regio, Seiten 61,229, 528.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).