1. Introduction

The edible films and coatings can be produced from the natural polymers, such as, proteins, polysaccharides or their combination, which are perfectly biodegradable and safe to environment [

1]. However, the main disadvantages of lipid-based films and coatings are their opaqueness, fragility and instability [

2]. Among the edible films based on hydrocolloids, alginate films have attracted particular interest for maintaining quality and extending shelf-life of fruits, vegetables, meat, poultry, seafoods, and cheeses by reducing dehydration, controlling respiration, enhancing product appearance and improving mechanical properties [

2].

The main advantage of the application of an edible coating with incorporated antioxidants is the decrease of oxidation due to the gas barrier properties of the alginate coating and the synergistic effect between these two factors [

2].

Surfactants are key ingredients used to improve the adhesion of coating materials [

3]. Soy lecithin, as a surfactant and component of edible films or coatings, particularly impacts their color, solubility, opacity and microstructure [

4]. Besides the factors mentioned above, lecithins may affect the antimicrobial properties of the films [

5].

Coffee, is one of the most widely consumed beverages in the world, and is prepared from green or roasted coffee beans. The health-promoting properties of a coffee brew are, to a great extent, determined by the presence of phenolic compounds in green coffee beans, as well as the both phenolic compounds and melanoidins in the case of roasted coffee beans. The predominant group of phenolic compounds present in coffee are the chlorogenic acids [

6].

Taking into account the bioactive properties of both green and roasted coffee beans, many in vitro and in vivo studies have shown hypoglycemic, antiviral, hepatoprotective and immunoprotective activity of coffee extracts [

6]. Moreover, consumption of coffee brews results in a decrease of 8-hydroxydeoxyguanoside which is widely used as a biomarker of oxidative damage [

7].

It was stated that some components of coffee brew: such as, caffeine, volatile and non-volatile phenolics, and phenolic acids are reported to have an antimicrobial activity. Regarding the properties of phenolic compounds, Almedia et al. [

8]has observed that of all the bioactive compounds of coffee brews; caffeine, trigoneline and protocatechuic acid are the most potential antimicrobial agents.

The cytotoxicity study of the effect of different degrees of roasting of commercial and special quality coffee on HepG2 cells showed that in the case of commercial quality samples, cancer cells were more sensitive to the cytotoxic effect of the extract from the dark roasted sample (IC50 0.2244 mg/ml), followed by light roasted samples (IC50 0.3721 mg/ml) and medium roasted sample (IC50 0.4343 mg/ml) [

9].

Among the special quality samples, it was found that HepG2 cells were more sensitive to treatment with the medium roasted sample, and the percentage of cell death at the lowest concentration reached 76.58 ± 2.99%. For the light roasted sample, the IC50 was 0.1849 mg/ml, followed by 0.2927 mg/ml for the dark roasted sample [

9].

The proliferation study showed that a 2-hour incubation with green coffee beans extracts (GCBE) did not affect the proliferation of A549 and OE-33 cancer cells, while it reduced proliferation in Caco-2 cells, and at the highest concentrations in T24 bladder cells. For 24-hour exposure, only the highest concentrations of GCBE reduced the proliferation of all tested cell lines, except OE-33 [

10].

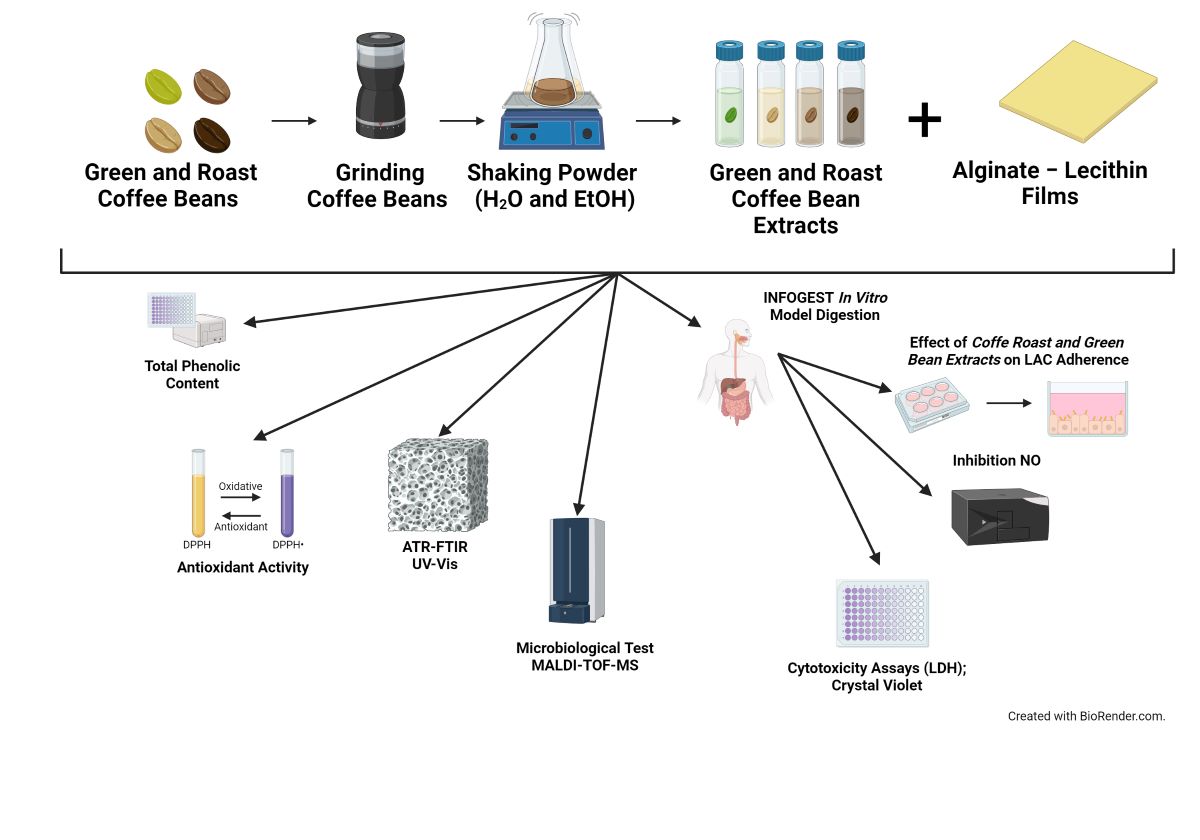

The aim of the study was to obtain new alginate-lecithin films with the addition of various coffee extracts. We hypothesized that the obtained films would be materials with good functional properties that determine their suitability as edible food packaging. We aimed to exclude cytotoxicity against human cells, determine anti-inflammatory, anti-microbial and physicochemical properties of the tested films, and to investigate the phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of the films.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC) of the Coffee Extracts

Values of TPC for the studied extract, expressed as mg of GAE per 1 dm

3 of extract, are collected in

Table 1. It was stated that roasting process of coffee beans had a significant impact on TPC in the studied extracts (

Table 1). The highest value of this parameter (134.86 mg GAE/dm

3) was observed for light roasted coffee beans; whereas, in the case of dark roasted ones was the lowest (102.89 mg GAE/dm

3) (

Table 1). With respect to the coffee beans, the most important components which can react with Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent may be divided into two groups. The first one includes coffee phenolics, mainly chlorogenic acids. This class of compounds is present in significant quantities in green coffee beans, and in smaller quantities in roasted ones. Whereas, the second group includes melanoidins, which content increases with increasing degree of roasting, and which are present only in roasted coffee beans. It was found that the TPC in light roasted coffee was significantly higher than that observed in green coffee (113, 36 mg GAE/L). During the roasting of green coffee beans, the content of chlorogenic acids decreases, resulting in formation of melanoidins. Similarly to phenolic acids, these latter compounds are also characterized by strong antioxidant activity [

11]. Thus, a decrease of phenolic acids content during roasting may be partially compensated by an increase of melanoidins content, what resulted in an increase of TPC value for extract of light roasted coffee when compared with that of green ones. The balance between natural coffee phenolics and melanoidins content is the most favorable in the case of light roasted coffee beans.

2.2. Antioxidant Activity of the Coffee Extract

The values of antioxidant activity of coffee extracts, expressed in mM of Trolox (T)/dm3 were collected in

Table 1. The results showed that all the extracts had a significant AA, but their values fluctuated considerably. Similarly, as in the TPC, the light roasted coffee exhibited the highest AA (0.88 mM T/L) following by medium roasted sample (0.82 mM T/L); whereas, dark roasted coffee extract was the lowest (0.64 mM T/dm3). The green coffee sample was characterized by an average value (0.735 mM T/L), among all the extracts. Similarly, to TPC, the AA of light and medium coffee exceeded that of green one despite the fact that the last sample was the richest in natural phenolic (chlorogenic acids). Thus, the obtained results confirm a high AA of melanoidins present in roasted coffee beans. In our study, a very high linear correlation (r = 0.99) was observed between the AA and TPC for the coffee extracts. However, besides chlorogenic acids and melanoidins, also the other factors are also involved in creating of antioxidant properties, including all the non-phenolic compounds generated in all stages of the Maillard reaction undergoing during roasting process.

2.3. Chlorogenic Acids (CGAs) Content in the Coffee Extracts

The amounts of individual chlorogenic acids, i.e., chlorogenic (5-CQA), cryptochlorogenic (4-CQA), neochlorogenic (3-CQA), 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic (3,4-diCQA), 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic (3,5-diCQA) and 4,5-dicaffeoylquninic (4,5-diCQA) acids in the coffee extracts, expressed in mg per 1 dm3 are specified in

Table 1. Total content of CGAs ranged from 405 to 3208 mg/L for the dark roasted and green coffee extract, respectively. Among the CGAs under study, 5-CQA was present at the highest content, ranging from 232.04 to 2052.66 mg/L of coffee extract, and comprising from 57% to 64% of the total CGAs content. On the contrary, 4,5-diCQA was present at the lowest level, ranging from 6.24 to 86.31 mg/L. CGAs contents were detected in a decreasing order, 5-CQA > 4-CQA > 3-CQA > 3,5-diCQA > 3,4-CQA > 4,5-CQA. The different order in case of dicaffeoylquinic acids (diCQAs) was observed by Fuijoka and Shibamoto [

12] who investigated various brands of coffees, where diCQAs content was detected in a decreasing order 3,4-diCQA > 4,5-diCQA >3,5-diCQA. This fact may result from differences between the coffee samples in terms of their botanical and geographical origin. The roasting process of coffee beans resulted in a decrease of CGAs content in the extracts. The extract of green coffee was characterized by the highest level of all the investigated CGAs; however, the obtained data did not correspond to the values of TPC and AA. Extract of light roasted coffee was characterized by the highest values of the latter parameters. That phenomenon may result from the fact that during light roasting of green beans the process of thermal decomposition of chlorogenic acids was compensated by formation of melanoidins exhibiting a strong antioxidant properties. Thus, the most optimal balance between chlorogenic acids and melanoidins (in terms of antioxidant activity) was achieved for light roasted coffee.

2.4. Free phenolic Acids (FPAs) Content in the Coffee Extracts Determined after an Alkaline Hydrolysis

Despite many reports focusing on presence of chlorogenic acids in coffee, scarce are data concerning research on the content of free phenolic acids (i.e., caffeic, p-coumaric and ferulic acid) creating the structure of chlorogenic acids [

13]. Thus, in order to determine FPAs content, an alkaline hydrolysis was performed, and resulted in a release of FPAs from the bounded forms. The amounts of individual FPAs (i.e., caffeic, p-coumaric and ferulic acids), expressed in mg/dm

3 of extract are specified in

Table 2. Among the acids under study, caffeic acid was a predominant compound in all extracts, and its level ranged from 294.2 to 1594.74 mg/dm

3. The presence of CA after hydrolysis was due to hydrolytic decomposition of mono- and dicaffeoylquinic acids. Ferulic acid turned out to be the second in terms of content acid was formed as a result of hydrolytic decomposition of 3-feruolylquinic, 4-feruoylquinic and 5-feruoylquinic acids belonging to the group of chlorogenic acids. The level of p-coumaric acid ranged from 9.19 to 25.33 mg/dm

3 of extract, and was the lowest among the acid tested. The chlorogenic acids were sensitive to roasting process, and the total level of CA in dark roasted coffee (

Table 2) comprising only 18.44% (in a form of CGAs) of its value for the green coffee extract. Similarly, as in the case of chlorogenic acids, green coffee extract was the richest in terms of FPAs content; whereas, the dark roasted coffee extract was the poorest. Again, the levels of FPAs did not correspond to the values of TPC and AA.

2.5. ATR-FTIR Spectrophotometry

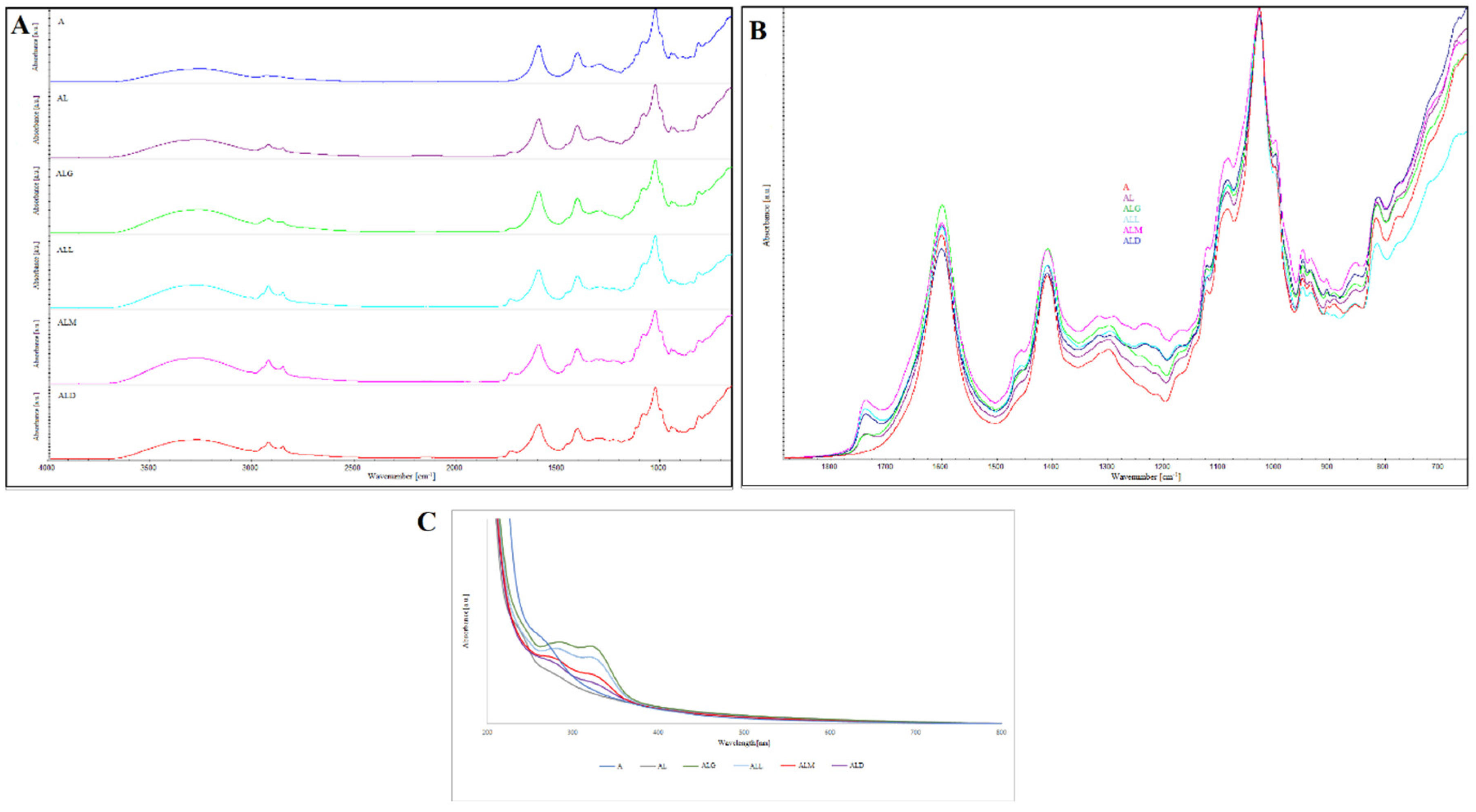

Fourier transformed infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy was used to identify the functional groups and carried out to observe the structural interactions of alginate-lecithin films enriched with the coffee extracts.

Figure 1A-B displays six FTIR spectra of the films with (and without) the addition of the coffee extracts.

There was a very limited number of changes between the obtained absorption spectra (

Figure 1A-B). A comparative evaluation of the FTIR bands indicated that most of the bands were similar in their band characteristics such as peak position and broad nature.

The FTIR spectra for alginic acid showed a typical infrared spectrum described in the literature [

14,

15,

16]. The alginate film spectrum revealed a broad band at 3300 cm-1 for the O–H stretching, and two bands at 1595 cm-1 and 1403 cm-1 characteristic for the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of carboxylate salt ions, respectively [

14]. The band with the highest absorbance, in the range between 1100–950 cm-1, and at 1020 cm-1, is associated with C–C stretching of D-guluronic acid from alginate [

15]. Further, the weak signal showing the presence of C–H stretching vibration [

16] was observed in the spectra at 2849 cm-1.

In the present study, FTIR spectra alginate/lecithin films, the most intense bands are those corresponding to alginate. In the spectral region between 1200 and 1100 cm−1, and centered around 1121 cm−1 there are the overlapped PO2− and P–O–C infrared active vibrations characteristic to lecithin lipids [

17]. It is worthy to note that lecithin has also a N(CH3)3 group band visible in the spectra at 935 cm-1 [

18]. The broad peak centered at 3400 cm-1 is corresponding to hydroxyl group from alcoholic esters. The weak band at 1733 cm-1 represent C=O esters groups, indicating phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine moiety presented in lecithin [

19].

The absorption spectra of alginate/lecithin films with the coffee extracts show some bands of the coffee components like caffeine, lipids, chlorogenic acids and carbohydrates. Analysis of these spectra reveals important regions (1750–1650 cm–1, and 1200–1100 cm–1) that could be helpful for the comparison. Spectra show also some common and significant features, such as the bands at around 1121 cm−1 related to PO2− and P–O–C infrared active vibrations characteristic for lecithins. Besides, the band around 1733 cm−1 is the best visible in the films with roasted coffee extracts what may be associated with the compounds polyphenolic in character. Nevertheless, it is observed a blue-shift about 6.0 cm–1 between the spectra made for the alginate/lecithin films with addition of the light and medium roasted coffee extracts. The other bands appear at 2914 and 2849 cm–1 are corresponding to the antisymmetric and symmetric vibrations of methyl group (–CH3) [

20], particularly those originating from lipids (Wang & Lim, 2012). The peaks attributed to caffeine present at the wavenumber around 2849 cm−1, and in the region of 1650–1600 cm−1 [

21] were overlapped with the peak of alginate carboxyl groups. The spectra region in the range 1800-1680 cm-1 is characteristic to carbonyl group, especially of coffee ingredients like aromatic and aliphatic acids, ketones, aldehydes or aliphatic esters [

22].

Nevertheless, a weak band at 1740 cm-1 is attributed to the carbonyl (C=O) vibration associated to the ester group in triglycerides. Lyman et al. [

22] also attributed to the band in that region to aliphatic esters. Coffee lipids band was attributed also at the wavenumber centered around 2930 cm−1 which is related to stretching vibration of the carbonyl and stretching asymmetric C–H of methylene groups. The band of chlorogenic acid present in the range of 1450–1400 cm−1 and centered around 1410 cm-1 [

22], are better visible in the case of films enriched with the medium and light roasted coffee extracts.

In the study concerning chemometric analysis of processed Brazilian coffees, Ribeiro et al. [

23] attributed the spectra in the range of 1700–1600 cm-1 to chlorogenic acids and caffeine concentration. Another author demonstrated that caffeine band is commonly detected in the range between 1650 and 1600 cm−1 [

24]. In our study we cannot observe the single bands corresponding to caffeine and chlorogenic acids due to the strong absorption of –COO- group (originating from alginate). However, the band stretch suggests that the spectra of other compounds are overlapped under carboxylate band.

In the spectra corresponding to the films enriched with coffee extracts, the band corresponding to the –OH vibration was shifted to 3400 cm-1, and is broader than that for the alginate films. This phenomenon may result from the presence of phenols and carboxylic acids originating from the coffee extracts and to the crosslinking interaction between these compounds and alginate/lecithin film.

2.6. UV–Vis Spectrophotometry

Figure 1C shows the UV-Vis absorption spectrum of alginate, alginate/lecithin and alginate/lecithin films with coffee extract of different degree of roasting.

In the range of 200–400 nm, there were observed two absorption peaks for all samples excluding alginate films. Characteristic peak for alginate was detected at 280 nm. As observed, UV–Vis absorbance spectrum of alginate/lecithin films displayed a two significant peaks at 245 nm and 290 nm.

The UV-Vis spectroscopy cannot be used directly for the determination of caffeine in coffee seeds due to the matrix effect and overlapping of UV absorbing substances [

25].

From the literature data the other compounds can absorbed in these regions e.g., chlorogenic acid (CGA) related compounds (p-coumaroyquinic acid). It has been shown that the chlorogenic acid makes complexes with caffeine [

26]. The authors concluded that, there is spectral interference from caffeine and CGA in the wavelength regions of 200-500 nm. In their research they show the spectrum of coffee beans dissolved in water. They observed two peaks in these wavelength regions. The first peak was register in the regions between 250-300 nm which belongs to the peak of caffeine. The second peak was observed in the 300-350 nm region and corresponds to the peak of CGA [

26,

27]. Analogous observations have been observed for our films with coffee extract of different degree of roasting. As observed in a

Figure 1C the absorption intensity of peaks is higher for the ALG films. This may be due to the fact that green coffee extract is richer in caffeine and chlorogenic acid. This data confirmed that the roasting process of coffee beans causes a decrease of chlorogenic acids in the extracts. Summarizing, the UV-Vis results ascertained the successful interaction between coffee extracts and alginate/lecithin matrix.

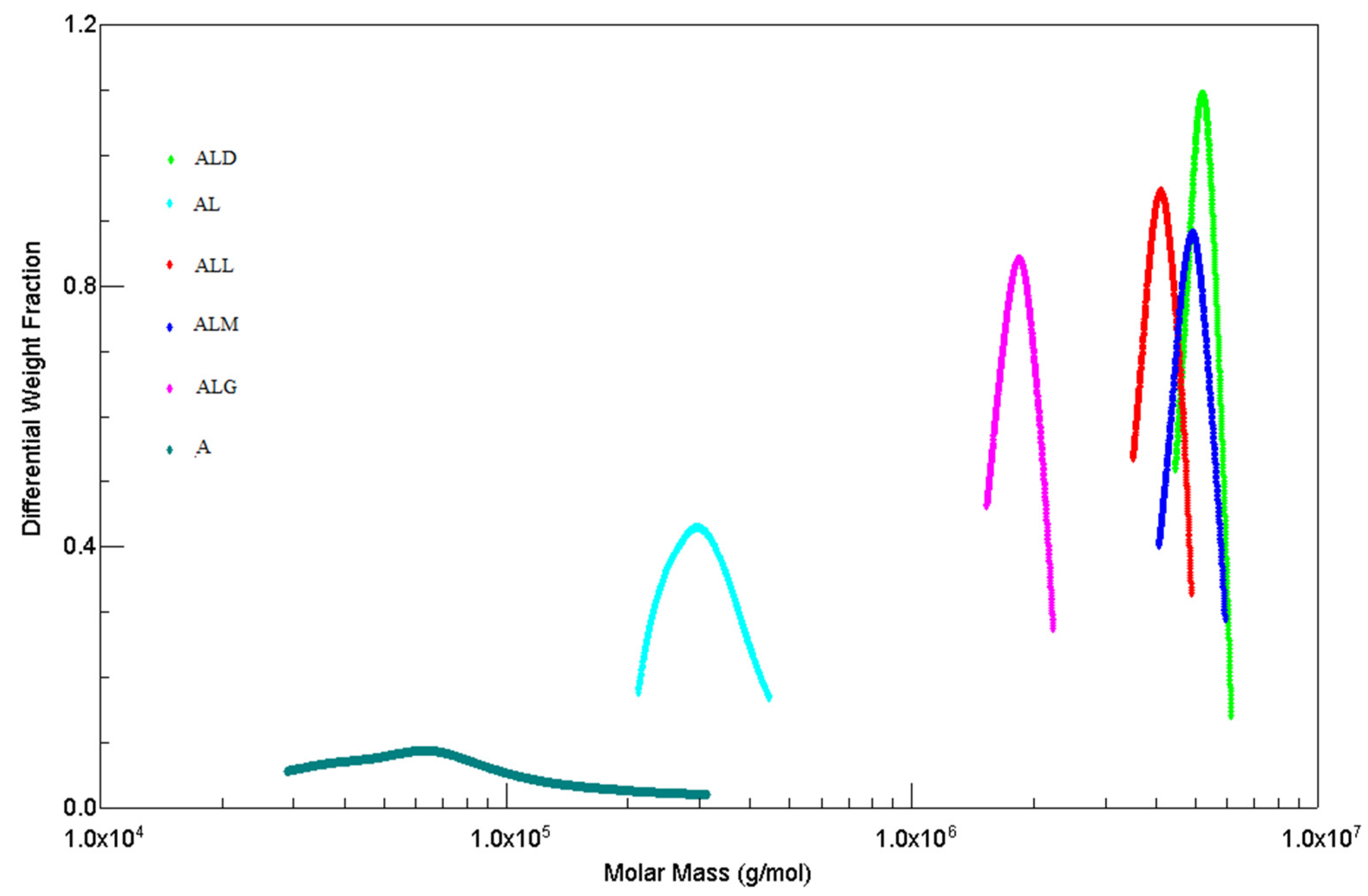

2.7. High-Performance Size Exclusion Chromatography (HPSEC–MALLS–RI)

A high-performance size exclusion chromatography (HPSEC) coupled with multi angle laser light-scattering (MALLS) and differential refractive index (RI) detector was used to determine the weight-average molecular weight (Mw) and radii of gyration (Rg) of alginate/lecithin films with coffee extracts (

Table 3).

The differential weight fraction vs molecular weight plots for samples of alginate, alginate/lecithin and alginate/lecithin films with the coffee extracts are illustrated in

Figure 2.

A differential weight fraction is the mass share of a sample containing molecules with a molecular mass constituting given fraction in relation to the total mass of the sample [

28].

The pure alginate sample exhibited a much broader molecular weight distribution than alginate/lecithin film and the films made with addition of the coffee extracts. We observed that the polydispersity of pure alginate was higher than that of all the films tested. The addition of lecithin and coffee extracts causes a reduction in the molar mass polydispersity.

Figure 2 shows that sodium alginate is characterized by a wide band of molecular weight distribution, while the alginate-lecithin film as well as the films made with the addition of coffee extracts are characterized by an increase of the homogeneity of the sample.

The addition of various coffee extracts to alginate/lecithin films led to a significant increase in the molecular weight of eluted polysaccharide chains, and exhibited a narrow Mw (

Table 3) distribution. Concurrently, a significant decrease in the polydispersity of the eluted molecules was observed when compared with the films without addition of the coffee extract.

It is worthy to note that addition of the coffee extracts changed the values of the weight-average molecular weights; however, it widely decreased the dispersity of the sample, which was reflected in the values of the radius of gyration. These significant increases in Mw (

Table 3) could be caused by interactions (crosslinking) between the alginate/lecithin films and the phenolic compounds (chlorogenic acids) and melanoidins present in the coffee extracts.

2.8. Thermal (DSC) Analysis of the Alginate Films

Evaluation of biopolymer film using of DSC analysis is valuable source of information on interactions between tested polymer and additives used during film preparation. These interactions may be responsible for changing thermal properties of biopolymers. In order to find the presence of an interaction between alginate and lecithin as well as between tested polymer and components of coffee extract, DSC spectra of the tested films were made and analyzed (

Table 4).

For all tested samples, only two peaks (corresponding to the phase transitions) were found on the DSC spectra. The first one at the temperature range 166.9 – 186.6°C can be attributed to the endothermic fusion associated with a melting of polysaccharide [

29,

30]; whereas, the second one at the temperature range 232.4 – 242.2°C was related to the exothermic fusion resulting from the polymer degradation processes. Alginate decomposition process is caused by a partial decarboxylation of protonated carboxyl groups of alginate following oxidation reaction of the polyelectrolite [

31]. With respect to our results (

Table 4), the highest differences between the values of studied thermal parameters i.e., temperature of endothermic fusion (associated with a melting process), and the heat of this fusion were observed between the film obtained for pure alginate and the alginate with the addition of lecithin (5% w/w). Incorporation of lecithin caused a decrease of temperature of melting point of alginate film by about 20°C accompanied by an increase in the heat of this fusion (from 76.96 to 174.53 J/g, respectively). In the contrary, addition of roasted coffee bean extracts to the AL film resulted in a decrease in melting point of polymer; however, a much lower than that observed for the film with only lecithin addition. With respect the heat of fusion (ΔHm) for melting, the observed increase (more than 2-fold) of that value was probably caused by formation of strong electrostatic interactions (ion – ion type) between the quaternary ammonium groups of lecithin and negatively charged alginate carboxyl groups, as well as hydroxyl groups (attributed to ion – dipole interactions). Within the samples under study incorporated with coffee extracts, no statistically significant differences were found between values of melting temperature (Tm) and enthalpy ΔHm of that process (

Table 4), with the exception of ALD sample for which ΔH (81.45 J/g) was significantly lower. A significant decrease in values of enthalpy in films enriched with roasted coffee components when compare with AL film was observed. That effect may result from a weakening of the strength of electrostatic interactions between alginate and lecithin and formation of competitive interactions between the positively charged quaternary choline moiety of lecithin and negatively charged carboxylic and/or hydroxyl groups of chlorogenic acids and melanoidins present in the roasted coffee extracts. Values of temperature of an exothermic fusion (attributed to a polymer decarboxylation) ranged from 232.4 to 233.9°C; however, they did not differ significantly within the analyzed samples (

Table 4). The statistically significant differences were only observed between the values of heat of exothermic fusion (ΔHm) which ranged from 144.1 to 350.63 J/g. The highest value of heat of decarboxylation process was observed in the case of alginate with lecithin addition (350.63 J/g) for which that value was two-times higher when compared to pure alginate. This fact proves the importance and strength of electrostatic interactions between the carboxyl groups of alginate and the positively charged lecithin used as a surfactant. Within the samples with addition of coffee extracts, the significant differences were also noticed between the values of heat of exothermic fusion ΔHm (

Table 4). The highest value of ΔHm (235.53 J/g) was observed for sample with addition of green coffee extract, while the lowest (144.10 J/g) for sample enriched with light roasted coffee.

2.9. Mechanical Properties of the Films

For the alginate/lecithin films, the effect of coffee extract on their mechanical properties was also analyzed (

Table 4).

Tensile strength (TS) is defined as the maximum load that a material can withstand without fracture. Values of this parameter for the films ranged from 108.5 to 172.3 MPa. The ALM film and the control sample had the highest tensile strength; whereas, ALG film had the lowest tensile strength (

Table 4). With the exception of ALM film, the enriched films have lower values of tensile strength in relation to the baseline film (

Table 4). An analogous trend was observed for the second parameter characterizing strength of the films, i.e., the maximum breaking load (MBL), with values ranging from 13.78 N for the ALL to 21.21 N for the ALM film. The mechanical properties of alginate and lecithin films are based on bonding forces in the polymer network i.e., strong electrostatic interactions between positively charged quaternary ammonium groups of lecithin and the negatively charged carboxyl and hydroxyl groups of alginate. This was also reflected in a significant increase in enthalpy value (from 76.97 to 174.53 J·g-1) for endothermic process (melting) of alginate/lecithin film compared to pure alginate (

Table 4). Higher enthalpy value ΔH (for melting the film), the more energy is required to break interaction between lecithin and alginate. Bioactive antioxidants present in coffee extracts with different roasting levels, such as chlorogenic acids and melanoids, can, through the competitive interactions of hydroxyl groups with positively charged lecithin fragments, cause the weakening of the alginate-lecithin interactions forming the film structure, which leads to destabilization of polymer network of the film, resulting in weakening of its strength (which leads to reduction in values of mechanical parameters of the film). In contrast, the ALM film shows better mechanical properties (MBL and TS) (

Table 4) compared to other films and the control film. Therefore, medium roast coffee extract can be considered as a crosslinking agent that improves the mechanical properties of film. These unique properties of medium roast coffee extract may be due to the fact that this type of extract presumably contains comparable amounts of two groups of bioactive antioxidants, (chlorogenic acids) and melanoidins formed during roasting of coffee beans. In this case, it is most likely that the strength of interactions created between melanoids and chlorogenic acids balances strength of the competitive interactions between these components of coffee extract and the structure forming film. So, that it is not weakened, unlike when one group of these compounds predominates in the extract. These results are partly justified by the literature data, according to which individual antioxidants can have positive or negative effect on film strength, depending on structure of phenolic compound and its concentration in the film. Phenolic compounds, such as tert-butylhydroquinone or quercetin, when added to cassava starch/gelatin film at high concentrations, result in a decrease in tensile strength parameter, which is due to formation of hydrogen bonds between hydroxyl groups of antioxidant and gelatin/starch molecules [

32]. On the contrary, an addition of tea-derived polyphenols to gelatin/sodium alginate film resulted in an increase in value of TS parameter which means that tea-derived polyphenols may serve as crosslinking agents for protein/polysaccharide polymers [

33]. These results confirm that extracts rich in phenolics compounds used as additives to polysaccharide films can have a positive or negative effect on mechanical properties of edible film, depending on their structure, and especially on their molecular weight and polarity. The modulus of elasticity (ME), i.e., the mechanical parameter that determines elasticity, was also specified. The value of the ME ranged from 3693.2 MPa for the film with green coffee to 6709.9 MPa for the reference film (

Table 4). Coffee extract added to alginate/lecithin film results in a decrease in ME values, but the decrease is smallest for film with medium roast coffee for which ME is equal 5749.1 MPa.

2.10. Water Absorption and Solubility

The water content in films is an indicator of the film hydrophilicity. According to researcher [

34], the difference in moisture level may be occurred due to the change in hydrophilicity of the films. In this case it may have an impact on the water permeability properties of edible films. The results regarding the water properties of the alginic, alginic/lecithin and films with coffee extract of different degree of roasting are presented in

Table 4.

Water content analysis of all samples demonstrated that the values were within the range of 11.29-17.31 %. Integration of coffee extracts had a significant influence on the moisture content of the films. The reduced water solubility of ALM and ALD films is due to the lower content of free phenolic acids (FPAs), TPCs and AAs, and therefore the higher content of melanoid compounds.

The solubility of the obtained films was 100% regardless of the additives. These results are in line with data available in literature on the subject, estimating the solubility of alginic acid as 100%.

Due to their total water solubility, alginate/lecithin films, regardless of the type of added extract, can be used as edible films, where solubility is one of the most important properties in food or pharmaceutical applications.

2.11. Water Contact Angle Determination

Water contact angle (WCA) is considered an important indicator that is used to assess level of hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity of film surface. Film surface is considered hydrophilic if WCA is low (below 90º) and hydrophobic if it is higher (above 90º). The results show that the type of extract used for the lecithin/alginate film affects the WCA value. It reaches lowest value for the ALG film (32.46) and highest value for the ALD film (41.30) (

Table 4). Observed increase in film hydrophobicity that accompanies an increase in coffee roasting level indicates a significant difference between physicochemical nature of polyphenols present in green coffee and melanoids that predominate in dark roast coffee. Chlorogenic acids present in the ALG film exhibit strong polarity, which influences on their ability to form hydrogen bonds between components of alginate/lecithin film and water molecules. These results in a clear advantage of hydrophilic properties of this film over other films tested (

Table 4). In contrast, macromolecular melanoids, show much lower tendency to form hydrogen bonds, with film components and water molecules. This results in an increase in hydrophobicity of the film.

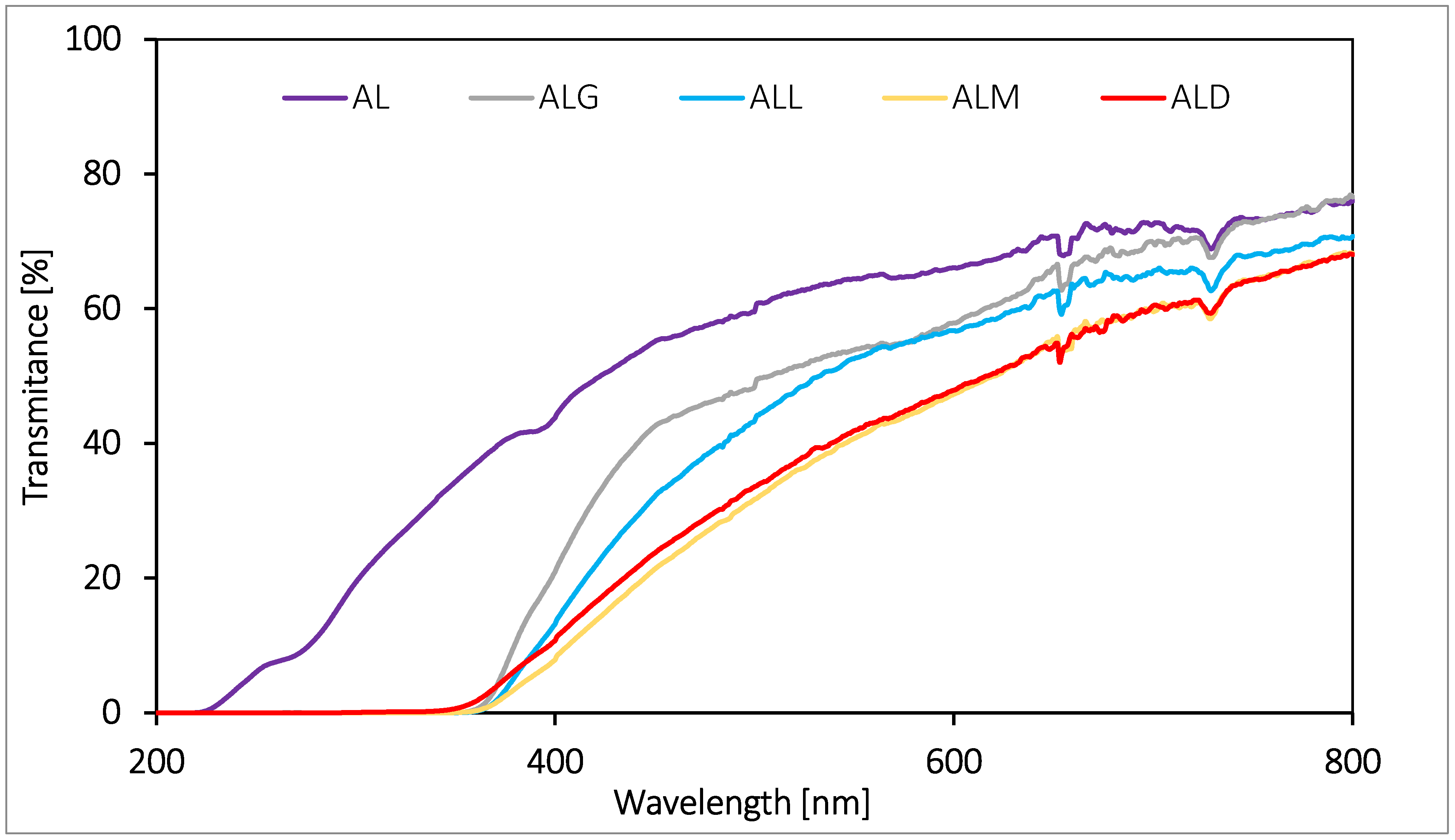

2.12. Foil Barrier Properties Estimated against UV-Vis Light

The barrier properties of edible films and packaging against UV-Vis light play a very important role. Visible and ultraviolet light is responsible for decomposition processes and especially for oxidation of food components, which results in adverse changes in the appearance, taste, and smell of food products and a reduction in nutritional value. Transmission spectra in range of light (200–800 nm) were performed for the lecithin/alginate films tested (

Figure 3). The obtained spectra revealed that the addition of coffee extract resulted in a significant improvement in barrier properties of the films against UV light, irrespective of the type of extract added. That phenomenon is reflected by a drastic decrease in transmittance values of tested samples in range from 200 to 400 nm with respect to the control film (AL). In the case of films with coffee of different roasting level, the coffee extract was also found to affect the barrier properties of the film against visible light (400–700 nm). This effect was observed to the greatest extent for the ALM and ALD films and to the least extent for the ALG and ALL films. This indicates that melanoids play the largest role in shaping barrier properties against Vis light. This fact confirms the benefits of using the new type of natural additive for alginate-lecithin films, the purpose of which is to protect the product from the harmful effects of sunlight.

2.12. Color Parameters and Opacity of the Films

Based on the obtained results, it was found that adding coffee extract to alginate/lecithin film results in a decrease in lightness (L

*) compared to the extract-free baseline film (AL) (

Table 5), as well as an increase in the values of the color parameters determining the balance between red and green (a

*) and between yellow and blue (b

*). Significant differences between the values of color parameters for the films were observed depending on the type of extract used. The film with green coffee extract was the lightest (L

* = 83.33), while the one enriched with dark roast coffee extract was the darkest (L

* = 64.21), which was due to the highest concentration of dark melanoids in latter sample. The films containing extracts of roasted coffees were more reddish and yellowish compared to the film with green coffee. In contrast to lightness, the highest values of a

* and b

* were found for the film enriched with dark roast coffee extract. These observations were confirmed for the values of WI (whiteness index) and YI (yellowness index) (

Table 5) calculated with the use of the measured L

*, a

* and b

* values. It was found that the non-enriched control film had the highest WI (87.03), while the sample with dark roast coffee extract had the lowest WI (48.31). The opposite trend was observed for YI, with the smallest value for the control film (16.46). In addition, the value of the total color difference (ΔE) was calculated (

Table 4). In contrast to the previously discussed color parameters, it was found that the film with medium roast coffee had the highest value of ΔE, relative to the control film (35.58), while the film with green coffee had the lowest value (11.66). Nevertheless, the calculated ΔE values indicate clear differences in color between the control film and the samples enriched with coffee extracts.

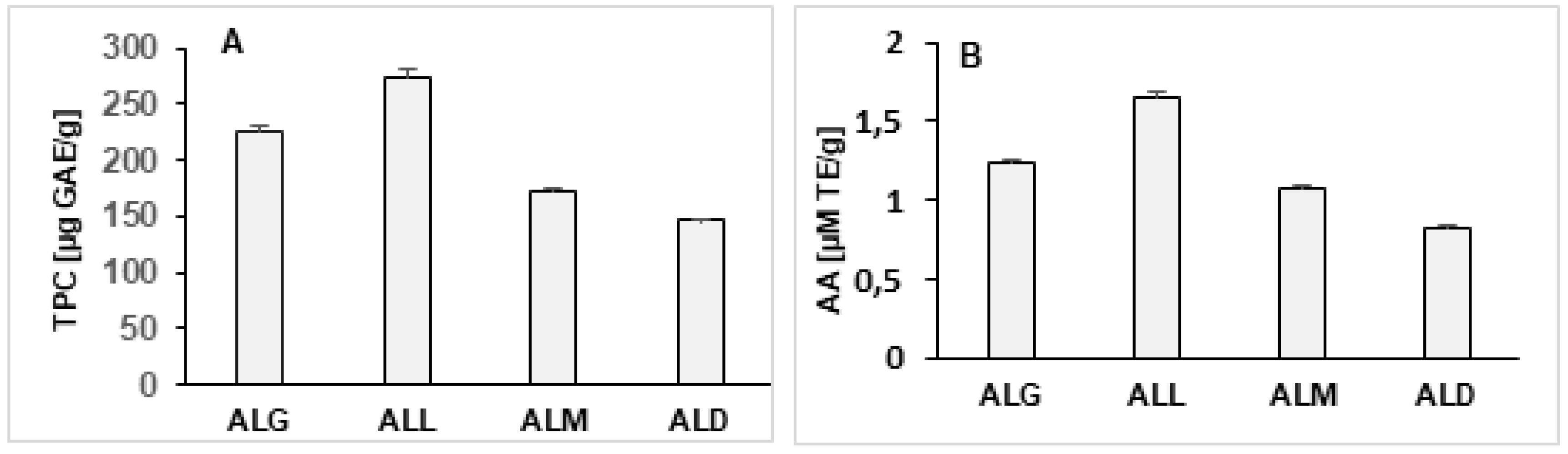

2.13. Determination of TPC and AA of the Coffee Extracts and Films

The content of TPC in studied films was shown in

Figure 4A. It was stated that alginate/lecithin films enriched with coffee extracts differed significantly in the term of this parameter. The values of TPC for tested samples, expresses in GAE ranged from 172.83 to 275.12 μg GAE per 1 g of film. The ALL film was characterized by the highest TPC (275.21), while the ALD was the lowest (146.34). Taking into account the content of antioxidants, the ALL film is characterized by the most favorable proportion between chlorogenic acids and melanoidins, the both responsible for ability to reduce Folin-Ciocalteu reagent by components of extracts added to the films. The tested films were also characterized by a varied AA measured in reaction with DPPH radicals (

Figure 4B). The ALL film had the highest AA value (1.652 µM/T) while the ALD film had the lowest (0.827 µM/T), respectively. A statistically significant correlation was found between the content of TPC and AA of the films (r = 0.981). Based on the results obtained, it can be concluded that an addition of coffee extracts to alginate/lecithin films significantly affects the antioxidant properties of this type of edible films.

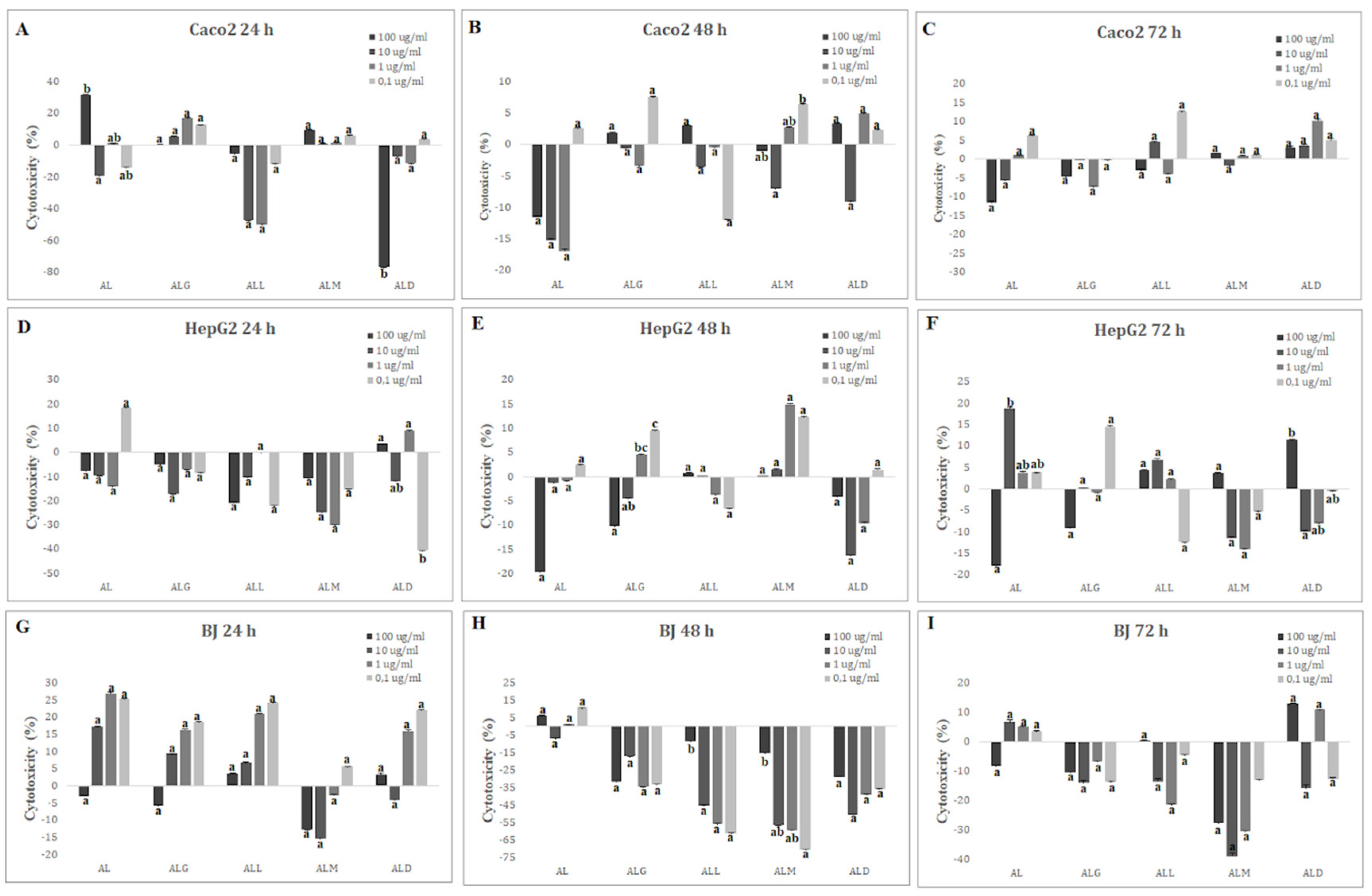

2.14. Cytotoxicity and Viability Analysis

Caco-2, HepG2 and BJ cell lines were treated with final concentrations (0,1 ug/mL->100 ug/mL) of digested films (AL, ALG, ALL, ALM and ALD). As indicated in

Figure 5A-I, all concentrations of films were below IC50% at all time points (24, 48, and 72 h), suggesting the safety of the films even at the highest concentration (100 ug/mL). In Caco-2 cell line the highest cytotoxicity (31.69±0.05) was observed for the AL film after 24 h incubation (

Figure 5A) with the highest dose 100 ug/mL while after 48 and 72 hours (

Figure 5B-C) it reached -11.50±0.17 and -11.53±0.32, respectively. The lowest cytotoxicity (-76.97±0.02) for Caco-2 cell line was observed for the ALD film after 24 hour in dose 100 ug/mL.

For the HepG2 and BJ lines, cells were most sensitive to the AL film in 10 ug/mL dose (18.84±0.63) after 72 hours (

Figure 5F) for HepG2 and 1 ug/mL (27.02±0.18) after 24 hours for BJ line (

Figure 5G). The lowest levels of cytotoxicity for both lines were observed for the ALM films in concentration of 1 ug/mL after 24 hours (-30.07±0.12) for HepG2 cells (

Figure 5D) and after 48 hours incubation with 0,1 ug/mL (-70.55±0.09) for BJ cell line (

Figure 5H).

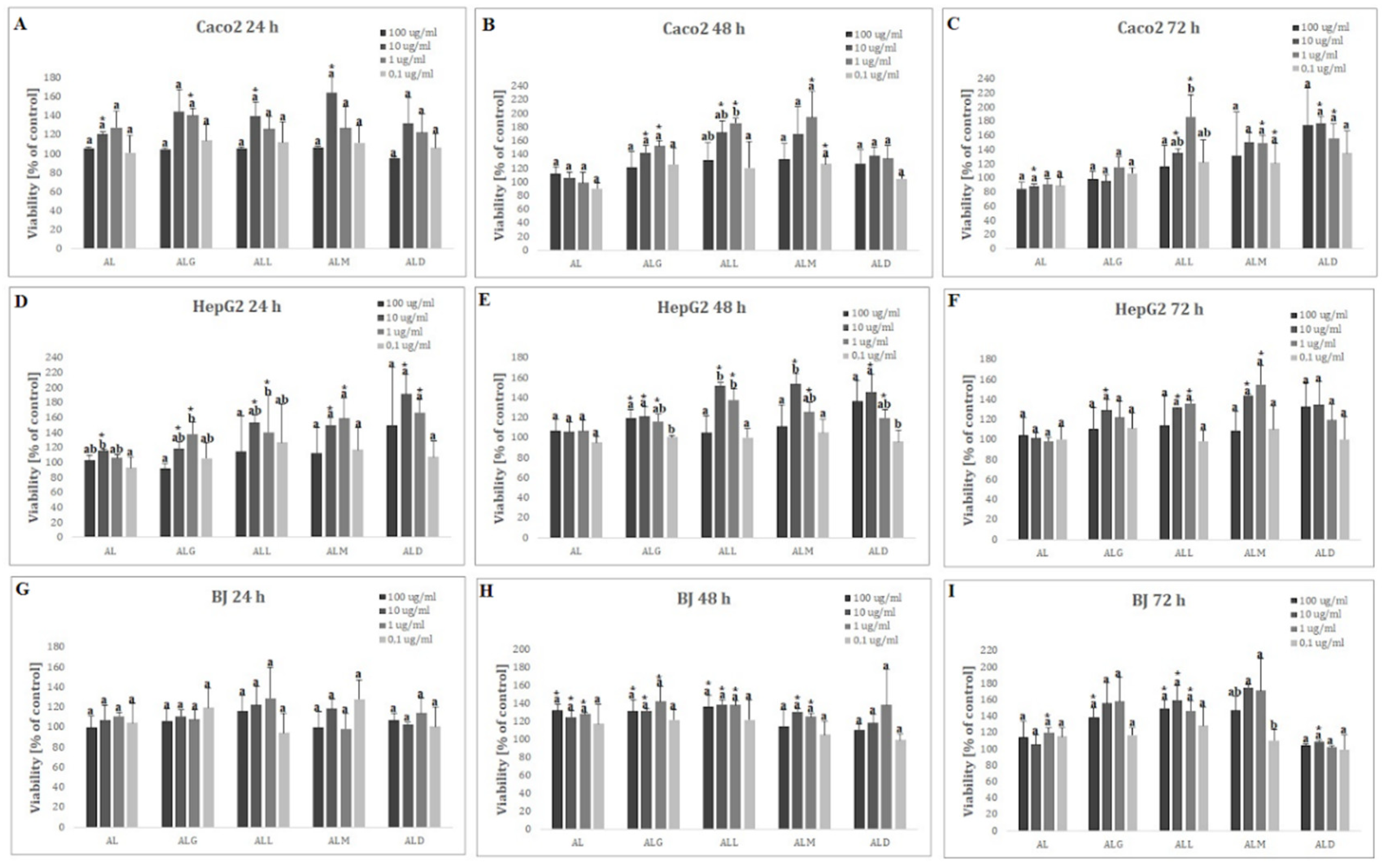

In cell viability analysis only in Caco-2 cell line, after 72 h-treatment with 10 ug/mL of digested AL film, a statistically significant decrease in cell viability (% of control: 87.96±4.31), as compared to untreated cells (negative control), was observed (

Figure 6C).

In contrast, a statistically significant increase in cell viability relative to the negative control was noted for all cell lines (

Figure 6A-I). The highest increase of viability was observed after 48 hours in dose 1 ug/mL for ALM film (% of control: 194.43±38.30), after 24 hours in concentration of 10 ug/mL of ALD (% of control 191.67±26.09) and after 72 hour in dose 10 ug/mL of ALM film (% of control 174.95±3.81) for Caco-2, HepG2 and BJ cell lines respectively.

In our earlier study, we showed that alginate-based biocomposites with the addition of antioxidant plant extracts did not exhibit cytotoxic properties (IC50 not reached) and had no negative effect on HepG2 and BJ cell proliferation [

35].

Hutachok et al. [

36] in their study on viability of PBMC, MDA-MB-231 and MCF-7 cells treated with roasted coffee extracts demonstrated that they were neither toxic to normal mononuclear cells nor breast cancer cells. PBMC cells viability after 48-hours treatment with all extracts were significantly increased in a concentration-dependent manner.

The study on the cell cytotoxicity of green coffee beans extracts (GCBE) reported that 10 µg/ml concentration showed differences after 24 hours of treatment in OE-33 and T24 cancer cells, while 100 µg/mL GCBE showed little effect, and only the highest dose (1000 µg/mL) affected the viability of normal CCD-18Co cells with reductions ranging from 87% (2 hours exposition) to only 22% in the Caco-2 cancer line (24 hours exposition) compared to the control cells [

10].

Additionally, in genotoxicity studies using the Cytokinesis-Block Micronucleus Assay on HepG2 cells, none of the coffee extracts of different degrees of roasting from commercial and special quality coffee evaluated were able to induce clastogenicity or aneugenicity in tested cells. For all samples in all tested concentrations the CBPI values ranged from 1.70 to 1.83 which indicated that most of the treated cells were binucleated. The obtained RI values for all the samples at all tested concentrations, showed that most of the treated cells were normally divided. Also, the inhibition of cell growth was up to 7.2%. This indicated that none of the coffee samples showed cytotoxicity of HepG2 cells at the treated concentrations [

9].

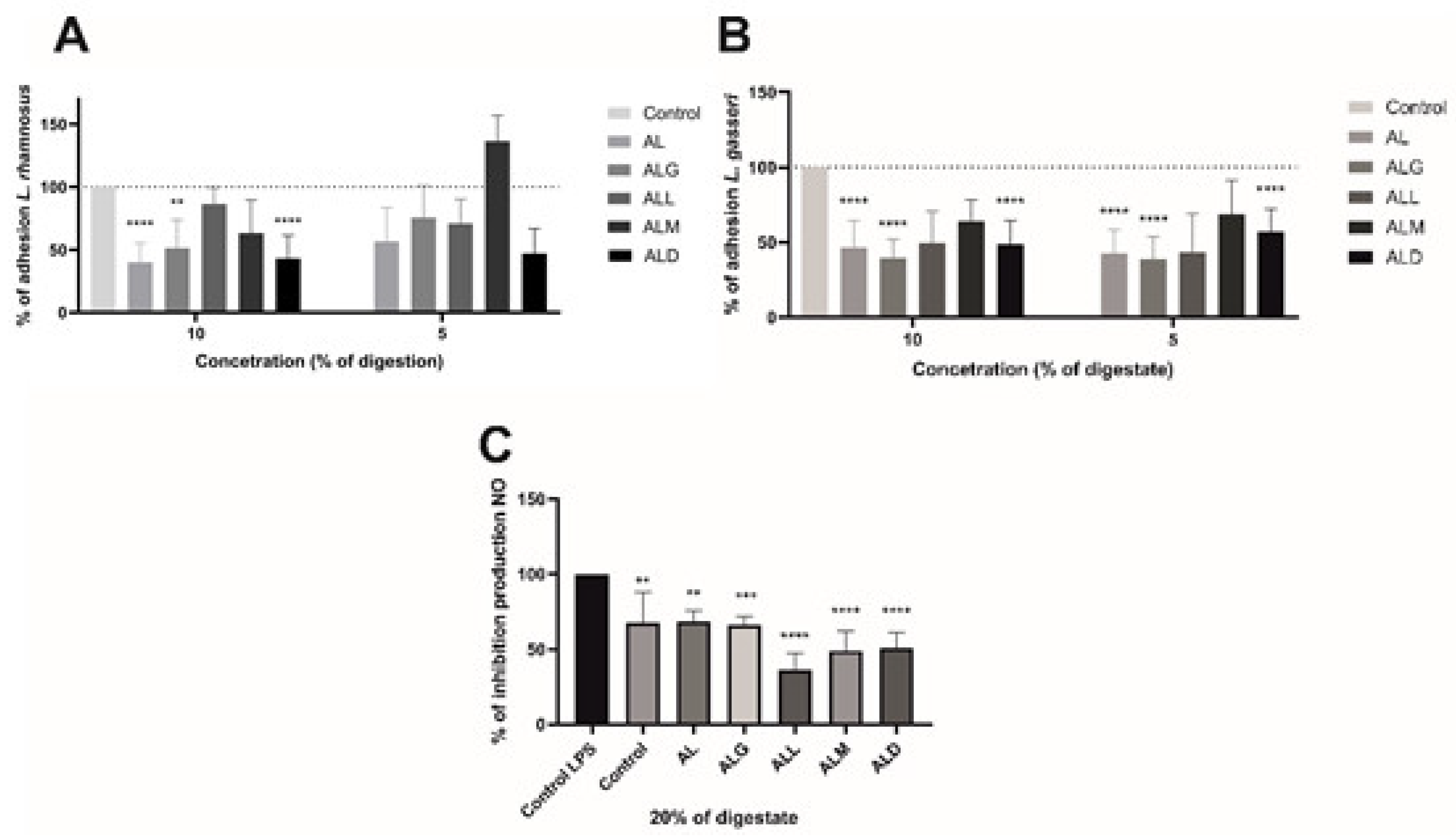

2.15. Influence of Digestion of Film to Adhesion of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Anti-Inflammatory Response in Murine Macrophages on Their Produce Nitric Oxide

For adhesion assays, 10% and 5% of the digest (at concentrations of 250 and 125 µg film/ml, respectively) were introduced to the cell lines along with

L. rhamnosus and

L. gasseri (

Figure 7). Notably, for

L. rhamnosus, all materials exhibited a reduction in adhesion ranging from 14% to 60% at a 10% concentration of digestate. At a 5% concentration of digestion, adhesion was similarly decreased by 25% to 53%, except for the ALM film, which showed a contrary increase of 36.6% in adhesion. In the case of

L. gasseri, the reduction in adhesion was more pronounced at a 10% digestive of film concentration, ranging from 35% to 60%, and at a 5% digestive of film concentration, it was reduced by 32% to 61%.

As reported by Grzelczyk et al. [

37], there is a 45-55% reduction in bacterial viability during digestion, depending on the type of coffee. This could also affect the intrinsic adhesion of the bacterial strains we added and reduce their ability to adhere better. However, an extended digestion time might lead to a higher release of bioactive compounds from the film, potentially positively influencing the gut microbiota [

37]. Therefore, digestion plays a crucial role in releasing polyphenols into the gut environment and influencing their interaction with the gut microbiota.

Polyphenols modulate the gut microbial population, and their metabolism by the microbiota alters their bioavailability. Higher molecular weight polyphenols, fully available for metabolism in the hindgut, are particularly significant for host health [

38]. The interplay between dietary polyphenolic bioactives and the gut microbiota is crucial to health outcomes. The interactions involve how polyphenols are metabolized by the microbiota and how they can modulate the microbiota to enhance their impact on preventing and improving certain [

39]. While the gut microbiota influences polyphenol metabolism and produces bioactive metabolites, polyphenols also shape the composition of the microbiota [

40].

The subsequent effect under investigation was the impact of digestion on the ability to inhibit nitric oxide production in mouse macrophages of the RAW 264.7 cell line when stimulated with LPS. According to the findings, all the materials tested (at 20% digestion or 500 µg/ml sample concentration) exhibited a reduction in nitric oxide (NO) production. Nevertheless, compared to the internal control, only the ALL sample displayed a noteworthy effect in significantly decreasing NO production. A statistically significant reduction of more than 31% in NO production was observed with a p-value less than 0.05 [

41]. As indicated by previous studies, chlorogenic acid has been observed to suppress LPS-induced NO expression in the RAW264.7 cell line, as reported by Kim et al. [

41]. As reported by Funakoshi-Tago et al. [

42] in a dose-dependent manner, coffee extracts significantly reduce NO production in the same cell line, even by more than 80% at a dose of 5% v/v. Similarly, the same is true for iNOS mRNA production [

43,

44].

2.16. Microbiological Tests

The results of the microbiological analyzes are presented in

Table 6. Each of the tested films with the addition of extract from green coffee beans or coffee beans of different degrees of roasting had growth inhibitory properties towards selected species of bacteria.

Analysis of ALG film showed growth inhibition of

E. coli,

S. aureus,

S. equorum,

S. xylosus and

E. faecalis. Similar results were observed by other scientists for

S. aureus and

S. enteritidis [

45]. These results are very important, mainly due to the fact that

E. coli and

S. aureus as potentially pathogenic bacteria, which are often, serve as model bacteria in studies on the bacteriostatic and bactericidal properties of various compounds [

46,

47,

48,

49].

Analysis of ALD and ALM films showed growth inhibition of

B. megaterium,

S. equorum,

S. xylosus,

E. faecalis, and

S. typhimurium (

Table 6). Analysis of ALL film showed growth inhibition of

B. megaterium,

S. equorum,

S. xylosus, and

E. faecalis (

Table 6). The obtained results are consistent with the results of the research conducted by Daglia et al. [

50], where all the tested samples of roasted coffee (light, medium and dark) showed a clear antibacterial effect, depended mainly on the roasting process.

Our studies showed that the largest zone of inhibition for each tested films with coffee extracts was observed for S.aureus, but growth inhibition was not observed for B. thuringiensis, B. cereus, M. luteus, and S. enteritidis.

Compounds contained in coffee can inhibit the growth of bacteria by changing the structure and function of the bacterial cytoplasm [

45]. It was found that caffeine contained in coffee at a concentration of 62.5 to >2000 μg·mL-1 can inhibit the growth of bacteria, while higher concentration (>5000 μg·mL-1) inhibits the growth of mold [

51].

The antibacterial activity of films with coffee extract against pathogenic bacteria was confirmed by Dondapati et al. [

52] and Rante et al. [

53]. It was found that coffee has significant activity against the growth of food spoilage bacteria [

54].

The antimicrobial activity of coffee extracts was described inter alia against

E. coli,

S. typhi,

P. aeruginosa,

S. aureus,

B. cereus, and

S. faecalis [

8,

54,

55,

56,

57]. However, the results obtained in our research are contradictory and indicate a lack of antimicrobial activity of the studied films against

B. cereus. On the other hand, the research conducted by Duangjai et al. [

58] showed antibacterial activity of coffee pulp extracts (Coffea arabica L.) against both Gram-positive bacteria (

S. aureus and

S. epidermidis) and Gram-negative bacteria (

P. aeruginosa and

E. coli) [

58]. In the case of

S. typhimurium, zones of growth inhibition were observed only for the ALD and ALM films.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Coffee Beans

Green Brasilia Santos Arabica coffee beans were purchased from the local shop in Krakow (Poland). The part of these beans was roasted in the coffee roasting plant in order to obtain beans of different degree of roasting (light, medium and dark).

3.2. Preparation of Coffee Extract

Extraction of phenolics from the coffee samples was performed according to Andrade et al. [

13] with minor modification. The 5 g of green and roasted coffee beans were homogenized and then the powdered samples were mixed with 60 mL of ethanol/water mixture (40/60, v/v) during 24 h. Obtained mixture was filtered and stored in the dark at 4°C.

3.3. Carbohydrate Polymer Characterization

Sodium alginate (extracted from the alga

Macrocystis pyrifera) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St Louis, USA). The viscosity of sodium alginate was 15.0–25.0 cps., mannuronate/guluronate ratio of 1.58, obtained from FT-IR spectroscopic analysis [

59].

3.4. Films Preparation

Soya lecithin powder, GMO free, 95% phosphatidylcholine (Louis Francois, Marne La Vallee, France) was dissolved in distilled water and stirred at 300 rpm at room temperature overnight. The films formulations were made by dissolving sodium alginate viscosity 15 - 25 cps (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, USA) (2,5%, w/v) in deionized water while stirring at temperature of 70°C, then glycerol (StanLab, Lublin, Poland) (1%, w/w) was added. Next dissolved lecithin (5%, w/w) was added drop by drop to the final solution and mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. The final solution was then homogenized with laboratory homogenizer (15000 rpm) for 5 min. Subsequently, the obtained final solution (alginate 2,5%, w/v; lecithin 5%, w/w and glycerol 1%, w/w) was a control film (AL). For the preparation of AL-coffee extracts complexes to the portions of AL solution were added ethanol/water mixtures of the four different coffee extracts (5%, v/v). All solutions of AL-coffee extracts (green (G), light (L), medium (M) or dark (D) roasted coffee) were homogenized with a laboratory homogenizer (15000 rpm) for 5 min. Finally, the samples were transferred into Petri dishes and dried at the same conditions and time like AL. In this manner, the four complexes with different additions of coffee extracts were obtained (ALG, ALL, ALM and ALD).

3.5. Determination of Total Phenolic Content (TPC) in the Coffee Extracts

The TPC was determined using a Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent following the procedure described by Singelton and Rossi [

60]. The measurements were performed in triplicate. The TPC was calculated mg of gallic acid equivalents per 1 L of the coffee extract.

3.6. Determination of Antioxidant Activity (AA) in the Coffee Extracts

Determination of AA was performed in the reaction with DPPH radical, according to the procedure described by Blois [

61]. The measurements were performed in triplicate. The AA was calculated as mM of Trolox equivalent per 1 L of coffee extract.

3.7. Determination of chlorogenic Acids (CGAs) Content in the Studied Coffee Extracts

The phenolic profile of coffee extracts was performed using a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) according to the procedure developed by Andrade et al. [

13]. The determination of chlorogenic acids content was performed by the use of a HPLC apparatus (HPLC, Jasco, Japan) equipped with a DAD detector (MD-2018 plus, Jasco, Japan). The chromatographic analysis was carried out on a Spherisorb (ODS) column (250 mm x 4 mm, particle size 5 µm) at a temperature of 30°C, and a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The qualitative and quantitative analyses of chlorogenic acids (i.e., chlorogenic, cryptochlorogenic and neochlorogenic acids, as well as 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic, 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic and 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acids) were made.

3.8. Determination of Free Phenolic Acids (FPA) in the Studied Coffee Extracts

In order to estimate the total content of FPA by means of HPLC including free forms of phenolics (i.e.,: caffeic, p-coumaric and ferulic acids released from their bound forms, i.e., chlorogenic acids) in the coffee extract, a hydrolytic procedure was performed according to Nardini and Ghiselli [

62]. The qualitative analysis of phenolic acids was carried out using a DAD detector (MD-2018 Plus, Jasco, Japan). The calibration curves of analyzed phenolic acids were made in triplicate for each individual standard and were plotted separately for each standard at concentration in the range 0.02 – 0.2 mg/L. The analyses of phenolic acids in coffee extract samples were carried out three times.

3.9. Physicochemical Properties of the Films

3.9.1. ATR-FTIR Spectrophotometry

The spectral measurements of the films were made with the ATR–FTIR spectrophotometer Nicolet iS5 (Thermo Scientific). A MIRacle ATR accessory equipped with a ZnSe crystal was used for sampling. The FTIR spectra were recorded in the range of 4000–700 cm-1 at a resolution of 4 cm-1. All the spectra were performed at room temperature (23 ± 0.5°C).

3.9.2. UV–Vis Spectrophotometry

The UV–Vis absorption spectra of the films were recorded using a Shimadzu 2101 scanning spectrophotometer (SHIMADZU, UV-2101PC, Japan). The absorbance spectrum was registered between 200 nm and 800 nm using 1 mL cells (Hellma). Concentration of solution was 100 μg/mL.

3.9.3. High-Performance Size Exclusion Chromatography (HPSEC–MALLS–RI)

The HPSEC system and methods of measurement are described in our previous publications [

28,

63]. Astra 4.70 software (Wyatt Technology, Santa Barbara, California, USA) with a Berry plot third-order polynomial fit was applied for the calculation of M

w and R

g values of alginate, alginate/lecithin and another films [

64,

65].

3.9.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) Analysis

The DSC analyses were obtained using a differential scanning calorimeter (Netzsch, Germany, Phoenix DSC 201 F1). The investigated film samples (approx. 2 mg) were closed hermetically in a standard aluminum pan and heated from 25°C to 300°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min under constant purging of nitrogen at 20 ml/min. An empty aluminum pan was used as the reference probe. The temperatures and enthalpy of thermal transitions were determined with the use of instrument’s software Proteus Analysis (Netzch, Germany). The characteristic peak temperature and enthalpy values of endotherm and exotherm were recorded. The analyses were carried out in three replications.

3.10. Determination of Mechanical Properties of the Films

In order to determine the mechanical properties of the films the following parameters were tested: maximum breaking load (MBL), modulus of elasticity (ME) and tensile strength (TS). These parameters were evaluated using a Shimadzu EZ-SX texturometer (Japan) in a stretch mode (with head movement speed 1 mm/s) and according to the ASTM D882-18 [

66]. The analyses were carried out in four replications.

3.11. Water Content and Solubility of the Films

The water content (WC) of prepared films were measured according to the method by Souza et al. [

67] with slight modifications. The films were cut into squares (3 cm x 3 cm) and weighed to the nearest ∼0.0001 g (W

1- initial weight). Then, the films were dried in an oven at 70°C for 24 hours to obtain the initial dry matter (W

2). After drying, samples were placed into 30 mL of Milli-Q water for 24 hours. Since our films dissolved completely, no further measurements were performed. Water content was calculated by Eqs.:

3.12. Water Contact Angle Determination

Water contact angle (WCA) was determined according to Jamróz et al. [

68].

3.13. Determination of Foil Barrier Properties against UV-Vis Light

In order to evaluate the foil barrier properties, the transmission spectra of the studied films were made in the range of 200 – 800 nm using a V-630 spectrophotometer (Jasco, Japan).

3.14. Determination of the Color Parameters and Opacity

Color parameters of the films were established in the CIELAB system by the reflection method (illuminant D65, range 400-700, measuring gap 25 nm, observer 10°) using a Color i5, X-Rite spectrophotometer (USA). The measurements were carried out in 5 replicates and were presented as L* (lightness), a* (red- green balance) and b* (yellow-blue balance). The measurements were carried out on a white background using a white master plate. The total value of color difference (ΔE) was calculated on the basis of the equation 1. ΔE was calculated in relation to the control sample (lecithin/alginate film). Additionally, the following parameters including WI (whiteness index) and YI (yellowness index) were calculated on the basis of equations 2 and 3.

Opacity (OP) of the films was determined using a spectrophotometr Jasco V-630 (Japan) at the wavelength of 600 nm and was calculated as: absorbance at 600 nm / thickness of the film (mm).

3.15. Determination of Total Phenolic Content

The TPC of studied films was determined using a Folin-Ciocalteu’s method. The small piece of the foil weighing appr. 200 mg was cut into small pieces that were placed in a test tube with the addition of 5 ml of 80% ethanol and left to shake for 24 h. The obtained mixture was filtered, and then 0.5 mL of the supernatant was analyzed according to the method developed by Singleton & Rossi [

60]. The measurements were performed in triplicate. The TPC of studied films was calculated as µg of GAE per 1g of the film.

3.16. Determination of Antioxidant Activity of the Films

Determination of the AA of studied films was performed using DPPH assay, accordingly to Chavoshizadeh et al. [

69] after minor modifications. The small piece of the foil weighing appr. 200 mg was cut into the small pieces that were placed in a test tube with the addition of 5 ml of 80% ethanol and left to shake for 24 h. The obtained mixture was filtered, then 0.3 mL of the supernatant was mixed with 3.7 mL of DPPH methanolic solution with the absorbance value of 0.5. After 30 min. of incubation the absorbance was measured using UV-Vis V-630 spectrophotometer (Jasco, Japan) at λ = 515 nm against methanol. The measurements were performed in triplicate. The AA of studied films was calculated as µg of trolox equivalents (TE) per 1g of the film.

3.17. In Vitro Digestion of Films

The in vitro static digestion model, conducted according to Brodkorb et al. (2019), was divided into three phases (oral, gastric, and intestinal). The temperature of 37°C was carefully maintained throughout the experiment in the incubator. For the digestion 1 g of sample was used. The oral phase lasted for 2 minutes, followed by the gastric and intestinal phases, both lasting 2 hours each. Samples were continuously mixed using special rotational shakers. During the gastric phase, the pH was lowered to 3 using hydrochloric acid, and during the intestinal phase, it was adjusted to pH 7 using sodium hydroxide. Digestion was subsequently halted by freezing the samples at -80°C.

3.18. Cell Culture

Human epithelial cell line Caco-2 derived from a colon carcinoma (ATCC

® HTB-37™), human hepatocyte carcinoma cell line HepG2 (ATCC

® HB-8065™) and human foreskin fibroblast cell line BJ (ATCC

® CRL-2522™) obtained from ATCC (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA;

https://www.atcc.org) were routinely cultured in EMEM medium (ATCC

®) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (ATCC

®) and antibiotic mixture.

Cell cultures were stored in standard conditions (37°C, 5% CO2, 98% humidity) in an incubator (NuAire, Plymouth, MN, USA). For the differentiation experiments, Caco-2 cells were seeded (50 000 cells) into upper compartments of 12-well 0.4 μm PET Transwell inserts (Greiner) and both upper and lower compartments were filled with the cell culture medium, which was replaced every 2-3 days. The differentiation progress was assessed after the monolayers reached confluence by measuring of transepithelial electric resistance (TEER) using EVOM electrode (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA), at the designated time points. HepG2 an BJ cells were cultured in the same conditions as Caco-2 cells.

3.19. Caco-2 Cells Permeability Assay

Caco-2 monolayers with an integrity equivalent to a trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TEER) higher than 200 Ω/cm2 were used for permeability experiments. The digested sample was placed on the top of the Caco-2 cells monolayer for 2 h. Collected filtrate was then used for cytotoxicity studies.

3.20. In vitro Cytotoxicity Analysis

In vitro cytotoxicity testing was performed using Cytotoxicity Detection Kit (LDH) (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Caco-2, HepG2 an BJ cells were seeded into 96-well plates (8 000 cells/well) and left for 24 h to attach. Next, the different concentrations of digested films were added and NADH oxidation after 24, 48, and 72 hours of treatment was specified by measuring absorbance with a Multiskan Go microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA USA) at 490 nm. The cytotoxicity % was calculated according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Cell viability was assessed by crystal violet assay. Caco-2, Hep G2 an BJ cells were seeded into 96-well plates (8 000 cells/well) and cultured for 24 h. Then cells were incubated with different concentrations of digested films for 24, 48 and 72 h. After that crystal violet assay was performed as described by Sularz et al. [

70]. The absorbance of the sample was measured using Thermo Scientific™ Multiskan™ GO Microplate Spectrophotometer (Waltham, MA, USA) at 540 nm. The results were expressed as % of negative control (100%).

3.21. Effect of Digestate on the Adhesion of Lactic Acid Bacteria

The digest samples underwent a threefold examination to assess their impact on the adhesion of lactic acid bacteria to intestinal cell lines. The bacterial adhesion procedures outlined in a prior study [

71] were employed with some adjustments. Human intestinal epithelial cell lines Caco-2 (ACC HBT-37) and HT29 (ACCT HBT-38) were procured from ATCC (USA, Virginia). A mixed cell culture, consisting of a 9:1 ratio of Caco-2 to HT29 cells at a concentration of 2×10

5, was cultivated in a 96-well plate for 14 days with periodic media replacement.

On the testing day, strains of

Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus (DSM20711) and

Lactobacillus gasseri (DSM20243T) were prepared at a concentration of 10

7 CFU/ml. The bacteria were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) at a final concentration of 25 µg/ml, with the staining process lasting 30 minutes at 37°C in a dark environment. Following staining, the bacteria underwent three washes with PBS and were introduced into the wells at a final concentration of 10

6 CFU/ml, along with samples containing 10% and 5% digestate. After a 2-hour incubation at 37°C in a CO

2 incubator, the plates underwent three washes with PBS, and fluorescence measurements were taken using a Tecan Infinite M200 instrument (Tecan Group, Männedorf, Switzerland) at an excitation wavelength of 495 nm and an emission wavelength of 519 nm. The percentage (%) of adhered bacteria was determined using the formula:

A is the fluorescence intensity after adherence of L. rhamnosus or L. gasseri to the cell culture; A 0 is the initial fluorescence value measured after removal of the redundant marker.

3.22. Effect of Digested on Inhibition of NO

The murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 (ATCC TIB-71) obtained from ATCC was cultured in RPMI1640 medium (BioWest, France), supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acids (BioWest), and 5% glucose (Sigma-Merck, Czech Republic). The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Nitric oxide (NO) secretion was assessed by measuring nitrite levels using Griess reagent (Sigma-Merck, Czech Republic). RAW264.7 cells line was seeded at 10

5 cells/well density into a 96-well plate. After a 2-hour incubation, the cells were treated for 24 hours with or without 1 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS, Sigma-Merck, Czech Republic) and samples at a concentration of 20% digestion. The supernatant media were collected, and 50 μL of the supernatant were mixed with 50 μL of Griess reagent in a separate well of the 96-well plate. The levels of NO in the supernatant were measured by assessing the absorbance of the mixture at 540 nm utilizing a TECAN Infinite M200 plate reader (Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland). The obtained absorbance values were compared against a standard curve generated with NaNO

3, as described in a prior study by Paudel et al. [

72].

3.23. Microbiological Tests

Microbiological analyzes were performed based on the discs diffusion method. For microbiological tests, 9 strains of environmental bacteria were used: 3 strains of Bacillus genus (B. thuringiensis, B. cereus, B. megaterium), 3 strains of Staphylococcus genus (S. aureus, S. equroum, S. xylosus), 1 strain of Escherichia genus (E. coli), 1 strain of Enterococcus genus (E. faecalis), 1 strain of Micrococcus genus (M. luteus) and 2 strains of Salmonella genus (S. typhimurium – ATCC 14028 and S. enteritidis – ATCC 13076, Biomaxima, Poland). Identification of species of environmental strains was carried out by using a modern ionization method of the sample combined with measurement of its mass – MALDI-Tof-MS system, using the Bruker Daltonic MALDI Biotyper. 18-hour bacterial cultures were used for preparation the suspensions of microorganisms in NaCl (0.85%) with an optical density of 0.5 McF. Next, the Petri plates were inoculated (with the tryptic-soy agar medium, TSA, Biomaxima, Poland) with prepared suspensions and after drying discs were applied (6 mm diameter) with 25 µl of tested samples (25 µl of sterile deionized water for control samples). The TSA plates were incubated for 18 hours in 37°C (for E. coli 18 hours in 44°C). After incubation the diameter (mm) of zone of growth inhibition of the microorganisms (including the diameter of the disc) was measured.

3.24. Statistical Analysis

The results were expressed as mean values ± standard deviations. The data were subjected to an analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, t-test or Fisher test, which were performed to determine whether differences were significant at p<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with the Statistica 13.3 PL program (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA) and GraphPad prism v10. (GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA).

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, new types of alginate-lecithin films were obtained with the addition of antioxidant-rich extracts from green coffee beans and coffee beans with different degrees of roasting.

The results from ATR-FTIR, UV-Vis spectrophotometry and DSC analysis confirmed the interactions, both between the functional groups of lecithin and alginate forming films and interactions between the phenolic groups of chlorogenic acids derived from coffee beans with the mentioned components of the tested films. Films with the addition of coffee extracts gained important antioxidant properties.

Furthermore, all films, regardless of the type of additive used, gained beneficial barrier properties against UV radiation. This makes them suitable for use as packaging to protect food products, both from light radiation and oxidative processes occurring on the surface of these products under the influence of oxygen and other negative physicochemical factors.

Cell line studies have shown that digested films do not negatively affect viability of the Caco-2, HepG2 and BJ cells, and do not have cytotoxic properties. This may indicate their safety as edible food packaging. Nevertheless, further studies on different cell lines and animal model are needed.

However, they negatively impact the colonization ability of selected lactic acid bacteria in the digestive tract while positively influencing the anti-inflammatory response. Specifically, they demonstrate significant capability in reducing nitric oxide production in the RAW264.7 cell line.

Based on the obtained results, tested films with coffee extracts showed selected antibacterial activities, which makes coffee promising potential natural food ingredient that extends the shelf life of food products. This biopolymer-phospholipid combinations with the addition of ethanol-water extracts of coffee polyphenols appear to be promising and require further research.

Alginate-lecithin films with coffee bean extracts are environmentally friendly packaging. Likewise, their production does not require the use of harmful and environmentally hazardous chemical reagents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.S., A.S., A.W-Ś., and A.K; writing – original draft, A.S.; writing – review & editing, R.S., A.W-Ś, and A.K; methodology, R.S., A.S., A.W-Ś, L.J., E.N, K.B, K.F, I.D., B.L., and A.K.; investigation, R.S., A.S., A.W-Ś, L.J., E.N, K.B, K.F, I.D., B.L., and A.K.; data curation, A.S.; formal analysis, A.S., R.S., A.K.; funding acquisition, A.K, A.S., I.D.; visualization, A.S; supervision, A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by research subsidy 070015-D020 and the activation of the Doctoral School of the University of Agriculture in Kraków AD12. This study was further supported by the METROFOOD-CZ research infrastructure project (MEYS Grant No: LM2023064). The scientific team was responsible for all stages of the study. The funding sponsors had no role in the study design; data collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to publish the results.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within article and are available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zactiti, E.M.; Kieckbusch, T.G. Potassium Sorbate Permeability in Biodegradable Alginate Films: Effect of the Antimicrobial Agent Concentration and Crosslinking Degree. J Food Eng 2006, 77, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senturk Parreidt, T.; Müller, K.; Schmid, M. Alginate-Based Edible Films and Coatings for Food Packaging Applications. Foods 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senturk Parreidt, T.; Schott, M.; Schmid, M.; Müller, K. Effect of Presence and Concentration of Plasticizers, Vegetable Oils, and Surfactants on the Properties of Sodium-Alginate-Based Edible Coatings. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leimann, F. V.; Gonçalves, O.H.; Sakanaka, L.S.; Azevedo, A.S.B.; Lima, M. V.; Barreiro, F.; Shirai, M.A. Active Food Packaging From Botanical, Animal, Bacterial, and Synthetic Sources. In Food Packaging and Preservation; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 87–135.

- Zhang, H.; Dudley, E.G.; Davidson, P.M.; Harte, F. Critical Concentration of Lecithin Enhances the Antimicrobial Activity of Eugenol against Escherichia Coli. Appl Environ Microbiol 2017, 83, e03467-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, D.; Farah, A.; Donangelo, C.; Paulis, T.; Martin, P. Comprehensive Analysis of Major and Minor Chlorogenic Acids and Lactones in Economically Relevant Brazilian Coffee Cultivars. Food Chem 2008, 106, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Zeeland, A.A.; de Groot, A.J.L.; Hall, J.; Donato, F. 8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine in DNA from Leukocytes of Healthy Adults: Relationship with Cigarette Smoking, Environmental Tobacco Smoke, Alcohol and Coffee Consumption. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis 1999, 439, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.A.P.; Farah, A.; Silva, D.A.M.; Nunan, E.A.; Glória, M.B.A. Antibacterial Activity of Coffee Extracts and Selected Coffee Chemical Compounds against Enterobacteria. J Agric Food Chem 2006, 54, 8738–8743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.Q.; Fernandes, A. da S. ; Teixeira, G.F.; França, R.J.; Marques, M.R. da C.; Felzenszwalb, I.; Falcão, D.Q.; Ferraz, E.R.A. Risk Assessment of Coffees of Different Qualities and Degrees of Roasting. Food Research International 2021, 141, 110089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amigo-Benavent, M.; Wang, S.; Mateos, R.; Sarriá, B.; Bravo, L. Antiproliferative and Cytotoxic Effects of Green Coffee and Yerba Mate Extracts, Their Main Hydroxycinnamic Acids, Methylxanthine and Metabolites in Different Human Cell Lines. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2017, 106, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, F.M.; Coimbra, M.A. Role of Hydroxycinnamates in Coffee Melanoidin Formation. Phytochemistry Reviews 2010, 9, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujioka, K.; Shibamoto, T. Chlorogenic Acid and Caffeine Contents in Various Commercial Brewed Coffees. Food Chem 2008, 106, 217–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, P.B.; Leitão, R.; Seabra, R.M.; Oliveira, M.B.; Ferreira, M.A. 3,4-Dimethoxycinnamic Acid Levels as a Tool for Differentiation of Coffea Canephora Var. Robusta and Coffea Arabica. Food Chem 1998, 61, 511–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Aziz, M.S.; Salama, H.E. Developing Multifunctional Edible Coatings Based on Alginate for Active Food Packaging. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 190, 837–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badita, C.R.; Aranghel, D.; Burducea, C.; Mereuta, P. Characterization of Sodium Alginate Based Films. Rom. J. Phys 2020, 65, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, F.; Idris, S.N.; Nasir, N.A.H.A.; Nawawi, M.A. Preparation and Characterization of Sodium Alginate-Based Edible Film with Antibacterial Additive Using Lemongrass Oil. Sains Malays 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kuligowski, J.; Quintás, G.; Esteve-Turrillas, F.A.; Garrigues, S.; De la Guardia, M. On-Line Gel Permeation Chromatography–Attenuated Total Reflectance–Fourier Transform Infrared Determination of Lecithin and Soybean Oil in Dietary Supplements. J Chromatogr A 2008, 1185, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiadi, S.; Hidayah, N. The Effect of Papain Enzyme Dosage on the Modification of Egg-Yolk Lecithin Emulsifier Product through Enzymatic Hydrolysis Reaction. International Journal of Technology 2018, 9, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.R.; Gaitonde, U.N.; Ganesh, A. Influence of Soy-Lecithin as Bio-Additive with Straight Vegetable Oil on CI Engine Characteristics. Renew Energy 2018, 115, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeidat, S.M.; Hammoudeh, A.Y.; Alomary, A.A. Application of FTIR Spectroscopy for Assessment of Green Coffee Beans According to Their Origin. J Appl Spectrosc 2018, 84, 1051–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahachairungrueng, W.; Meechan, C.; Veerachat, N.; Thompson, A.K.; Teerachaichayut, S. Assessing the Levels of Robusta and Arabica in Roasted Ground Coffee Using NIR Hyperspectral Imaging and FTIR Spectroscopy. Foods 2022, 11, 3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyman, D.J.; Benck, R.; Dell, S.; Merle, S.; Murray-Wijelath, J. FTIR-ATR Analysis of Brewed Coffee: Effect of Roasting Conditions. J Agric Food Chem 2003, 51, 3268–3272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.S.; Salva, T.J.; Ferreira, M.M.C. Chemometric Studies for Quality Control of Processed Brazilian Coffees Using Drifts. J Food Qual 2010, 33, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, A.P.; Franca, A.S.; Oliveira, L.S.; Irudayaraj, J.; Ileleji, K. Application of Elastic Net and Infrared Spectroscopy in the Discrimination between Defective and Non-Defective Roasted Coffees. Talanta 2014, 128, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Lian, H.-Z.; Wang, W.; Chen, H.-Y. Separation of Caffeine and Theophylline in Poly(Dimethylsiloxane) Microchannel Electrophoresis with Electrochemical Detection. J Chromatogr A 2006, 1098, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, A.; Ture, K.; Redi, M.; Asfaw, A. Measurement of Caffeine in Coffee Beans with UV/Vis Spectrometer. Food Chem 2008, 108, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemta, A.; Gholap, A. Characterization and Determination of Chlorogenic Acid (CGA) in Coffee Beans by UV-Vis Spectroscopy. African Journal of Pure and Applied Chemistry 2009, 3, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khachatryan, G.; Krzeminska-Fiedorowicz, L.; Nowak, E.; Fiedorowicz, M. Molecular Structure and Physicochemical Properties of Hylon V and Hylon VII Starches Illuminated with Linearly Polarised Visible Light. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2014, 58, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadzińska, J.; Bryś, J.; Ostrowska-Ligȩza, E.; Estéve, M.; Janowicz, M. Influence of Vegetable Oils Addition on the Selected Physical Properties of Apple–Sodium Alginate Edible Films. Polymer Bulletin 2019, 77, 883–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimmo, T.; Marzadori, C.; Montecchio, D.; Gessa, C. Characterisation of Ca- and Al-Pectate Gels by Thermal Analysis and FT-IR Spectroscopy. Carbohydr Res 2005, 340, 2510—2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R.; Carvalho, A.; Vaz, D.C.; Gil, M.H.; Mendes, A.; Bártolo, P. Development of Novel Alginate Based Hydrogel Films for Wound Healing Applications. Int J Biol Macromol 2013, 52, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongdeesoontorn, W.; Mauer, L.J.; Wongruong, S.; Sriburi, P.; Reungsang, A.; Rachtanapun, P. Antioxidant Films from Cassava Starch/Gelatin Biocomposite Fortified with Quercetin and TBHQ and Their Applications in Food Models. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Li, B.; Zhang, K.; Chu, X.; Hou, H. Physical Properties and Antioxidant Activity of Gelatin-Sodium Alginate Edible Films with Tea Polyphenols. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 118, 1377–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, A.; Alam, M.; Bhatia, S.; Gupta, S. Studies on Development and Evaluation of Glycerol Incorporated Cellulose and Alginate Based Edible Films. Indian Journal of Agricultural Biochemistry 2017, 30, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Such, A.; Wisła-Świder, A.; Węsierska, E.; Nowak, E.; Szatkowski, P.; Kopcińska, J.; Koronowicz, A. Edible Chitosan-Alginate Based Coatings Enriched with Turmeric and Oregano Additives: Formulation, Antimicrobial and Non-Cytotoxic Properties. Food Chem 2023, 426, 136662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutachok, N.; Koonyosying, P.; Pankasemsuk, T.; Angkasith, P.; Chumpun, C.; Fucharoen, S.; Srichairatanakool, S. Chemical Analysis, Toxicity Study, and Free-Radical Scavenging and Iron-Binding Assays Involving Coffee (Coffea Arabica) Extracts. Molecules 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzelczyk, J.; Szwajgier, D.; Baranowska-Wójcik, E.; Budryn, G.; Zakłos-Szyda, M.; Sosnowska, B. Bioaccessibility of Coffee Bean Hydroxycinnamic Acids during in Vitro Digestion Influenced by the Degree of Roasting and Activity of Intestinal Probiotic Bacteria, and Their Activity in Caco-2 and HT29 Cells. Food Chem 2022, 392, 133328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona, F.; Andrés-Lacueva, C.; Tulipani, S.; Tinahones, F.J.; Queipo-Ortuño, M.I. Benefits of Polyphenols on Gut Microbiota and Implications in Human Health. J Nutr Biochem 2013, 24, 1415–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vamanu, E.; Gatea, F. Correlations between Microbiota Bioactivity and Bioavailability of Functional Compounds: A Mini-Review. Biomedicines 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, T.A.F.; Rogero, M.M.; Hassimotto, N.M.A.; Lajolo, F.M. The Two-Way Polyphenols-Microbiota Interactions and Their Effects on Obesity and Related Metabolic Diseases. Front Nutr 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Park, S.-Y.; Park, Y.-L.; Myung, D.-S.; Rew, J.-S.; Joo, Y.-E. Chlorogenic Acid Suppresses Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Nitric Oxide and Interleukin-1β Expression by Inhibiting JAK2/STAT3 Activation in RAW264. 7 Cells. Mol Med Rep 2017, 16, 9224–9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funakoshi-Tago, M.; Nonaka, Y.; Tago, K.; Takeda, M.; Ishihara, Y.; Sakai, A.; Matsutaka, M.; Kobata, K.; Tamura, H. Pyrocatechol, a Component of Coffee, Suppresses LPS-Induced Inflammatory Responses by Inhibiting NF-ΚB and Activating Nrf2. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollo-Hernanz, M.; Zhang, Q.; Aguilera, Y.; Martín-Cabrejas, M.A.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Relationship of the Phytochemicals from Coffee and Cocoa By-Products with Their Potential to Modulate Biomarkers of Metabolic Syndrome In Vitro. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, R.; Miao, L.; Zhang, H.; Tan, L.; Zhao, Y.; Tu, Y.; Angel Prieto, M.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Chen, L.; He, C.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Flavonols via Inhibiting MAPK and NF-ΚB Signaling Pathways in RAW264. 7 Macrophages. Curr Res Food Sci 2022, 5, 1176–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]