1. Introduction

University students face many difficulties during their formative years in college, such as adjusting to new schedules, creating new social networks, and adjusting to changes in the built and social environments [

1]. College students are more likely to engage in risky health behaviours during this time of life, such as stress, poor dietary habits, and physical inactivity, which are known to affect well-being negatively [

2,

3]. Numerous studies conducted in Saudi Arabia have shown that college students have unhealthy eating and exercise habits [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Other studies that investigated Saudi health college students also found that, despite their awareness of the value of forming healthy habits, they were not fully following the recommended guidelines [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Saudi college students are more likely to gain weight as a result of these behavioural factors, which raises their risk of illness [

12,

13].

Health behaviors are actions that have an impact on an individual’s or a community’s health, such as food and exercise. The possibilities that exist for places where people live, work, learn, and play serve as its foundation. According to the World Health Organization [

14], diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and stroke are examples of chronic (long-term) diseases that are the leading causes of death globally. Adult chronic disease morbidity and mortality are heavily influenced by behavioural risk factors, such as obesity, sedentary behaviour, and physical inactivity [

15]. Unhealthy lifestyle choices and excess body weight increase the risk of noncommunicable diseases. Students at universities are more prone to obesity and bad habits.

Peer pressure and food availability and affordability are examples of societal and environmental factors. Students claim that perceptions of the health benefits of food and nutrition knowledge (NK), along with other personal factors like cooking abilities, also influence dietary behaviour [

16]. It has been discovered that NK in college students is positively correlated with eating more fruit, dairy, protein, and wholegrain foods [

17] or other dietary behaviours (e.g., reading food labels).

Results from previous cross-sectional studies on college students point to a lack of understanding on a variety of nutritional subjects. Students specifically mis answered more than 50% of the questions about fruit and vegetables [

18], milk, its substitutes, and fermented dairy products [

18], vitamin D [

19,

20], food labels [

21], and the connection between diet and chronic illness [

22,

23,

24].

Research is increasingly showing that behavioural risk factors, including physical inactivity, obesity, and sedentary behaviour, co-occur in youth and raise the risk of chronic illnesses more than the sum of their individual impacts [

25]. In addition to the health behaviours as modifiable risk factors that can be changed there are other non-modifiable ones like age, sex, and ethnicity, contribute to the development of chronic disease [

26].

A study conducted by [

27] investigated on the effects of weekly training time, daily sitting time, and body mass index BMI) on exercise-induced heart rate and systolic blood pressure in first-year health sciences college students at Dammam Saudi Arabia University. The study discovered that approximately 65% of the individuals did not reach the suggested threshold for physical activity related to health. Additionally, evidence demonstrating the connection between TV watching, the Internet, and academic pressure all contributed to a decrease in interest in fitness training. Inactivity and sedentary behaviour are two prevalent risk factors for health [

28]. Since some activities may be risk-free when done in moderation, engaging in no activity at all may be harmful, the definition of risk behaviour recognizes the significance of young people getting at least a minimum amount of exercise each day such as having a severely sedentary lifestyle [

29].

Physical activity is one of the practices associated with improved mental health. In addition to physical well-being [

30], high physical activity (PA) is linked to mental and social well-being [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Elevated levels of physical activity have a positive correlation with overall well-being and a negative correlation with signs of anxiety and depression [

36]. An increased prevalence of anxiety is linked to low PA levels [

37]. In a similar line, PA has a significant medium effect on reducing depressive symptoms and a low effect on reducing anxiety symptoms, according to a meta-analysis of 92 studies [

38]. However, two meta-analyses concluded that PA could offer protection against the onset of depression [

39,

40].

University students who adhere to PA guidelines are more likely to report positive mental health [

41]. Moderate and high levels of PA are inversely correlated with anxiety and depression scores, according to research conducted on university students [

42,

43]. It is also found that university students who engage in regular PA correlate favorably with quality of life and negatively with stress, anxiety, and depression [

44].

Students’ behaviour is influenced by the quick changes in their biological, emotional, cognitive, and social development when they get to high school or university. Adolescents and young adults typically exhibit curiosity at this age and experiment with a wide range of activities that are thought to be a necessary part of growing up. Different societies have boundaries for certain behaviours, which are deemed undesirable and detrimental to both the individual and the community [

5].

An important component of making an informed decision regarding a healthy lifestyle is knowing the links between behavior and health (risk awareness). Examples such as belief or attitude are considered factors associated with risk awareness. As demonstrated by numerous research (e.g., [

45,

46]), the perceived benefits of some health behaviors are linked to their actual adoption. Positive health behaviours include protecting against disease risk, detecting disease and impairment through physical activity, and promoting and enhancing health. Consensus in science, medicine, and society determines such behaviours, which are not fixed. Typical healthy behaviours include eating a low-fat diet, regular exercise, and eating fruits and vegetables. The health habits that formed in childhood and adolescence can significantly influence the likelihood of developing diseases later in life [

47]. Behavioral factors like physical activity, food, and routine health checks are firmly linked as risk factors even if the complete aetiology of any of these diseases is yet unknown.

It is important to focus on university students to obtain a strong and regularly updated database regarding students’ health and wellbeing is necessary to derive targeted and sustainable health promotion interventions and strategies, as universities are being urged more and more to support a healthy academic environment with limited resources. In light of all causes mentioned earlier, the current study inquiries were developed to investigate whether the higher MH among undergraduate students correlates with PA and investigate the relationships between PA and MH levels in university students, with a focus on determining whether these associations can vary based on the level of PA (low, medium, or high) and the students’ knowledge concerning nutrition.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

In this study, a cross-sectional quantitative survey method was employed. It is a quantitative evaluation of the risky and health-related behaviors, psychological health, and health-related behaviors of female university students. The study was carried out during the academic year 2023. The students sample filled an e- questionnaire face to face with a peer student who was well-trained to assess fitness levels and body composition as well by engaging in practical and technical training. The trained student verify if the sample students have any questions, comprehends the questionnaire, and finally submits their responses. From each college, one department was chosen randomly (probability of selection correlated with department size). A survey instrument was created to gauge and examine students’ perspectives regarding healthy habits and exercises that enhance their physical and mental well-being. Participants received explanations about the study and the health-related activities, as well as the reason behind the survey. Blood pressure was taken by a medical staff (nurse) and physical characteristics (weight and length) were measured by the trained research team to ensure the accuracy of the measurements and standardization of the measurement method. A total of 153 students, ranging in age from 18 to 25, from all colleges, who did not have a history of psychological issues, or a prior diagnosis of physical disabilities met the inclusion criteria for this study.

2.2. Study Instruments

Saudi college students were approached via an online Survey Monkey. The questionnaire was designed with three main sections. The initial subdivision focused on sociodemographic and general health information concerning respondents. It includes questions related to age, sex, educational background, and health status. The second and third sections consisted of self-report questionnaires targeted assessing participants’ engagement in PA and health related behavior as well as mental health. These inquiries were chosen with care to offer thorough insights into participants’ knowledge concerning their general and mental health and PA.

2.2.1. Sociodemographic and General Information

For the sociodemographic questionnaire participants were requested to disclose their age, to rate their health status as excellent, very good, good or poor, to indicate their GPA of the previous semester, their marital status, to reveal their residence status, and to indicate the perception of their body weight.

2.2.2. International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)

This questionnaire is employed to explore the extent to which students engage in physical activity while they are at college, during commutes, during leisure time, and other activities that are considered forms of physical exercise. The number of days per week that were dedicated to moderate activities was documented in the questionnaire that was prepared to document these queries. The questionnaire is a self-administered questionnaire. Its objective is to offer standard tools that can be used to gather data on physical activity related to health that are comparable across borders [

48].

2.2.3. Health Belief Model (HBM)

Participants were asked to rate the importance of a series of behaviours for health maintenance according to their importance to health. According to [

49] the health belief model is a psychological framework that focuses on people’s attitudes and beliefs to explain and forecast health-related behaviours [

49].

2.2.4. Health Risk Appraisal (HRA)

The risk-knowledge items involved asking the participants to indicate whether or not each of dietary fat, exercise, smoking and alcohol consumption contributed to five different health problems (heart disease, lung cancer, mental illness, breast cancer, high blood pressure) [

50,

51]. It describes a person’s chances of becoming ill or dying from selected diseases. HRA has become a popular approach to help people identify the risks associated with personal characteristics (biological, lifestyle, family history).

2.2.5. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

A 7-item screener is used to identify PTSD symptoms in the past month [

52]. Items ask whether the respondent had experienced difficulties related to a traumatic experience (e.g., “Did you begin to feel more isolated and distant from other people?”, “Did you become jumpy or get easily startled by ordinary noises or movements?”).

2.3. Procedure of Data Collection

The participants’ physical characteristics were measured by trained researchers using standardized weight. The standing height of each student is measured to the nearest 0.1 cm without shoes, using a stature meter. Participants are weighed to the nearest 0.01 kg, on a load-cell-operated digital scale having a weighing capacity of 140 kg. The scale used during the survey is first calibrated with a standard weight and checked daily. Body mass index (BMI) was computed for each participant by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. Waist circumference is measured around the waist through a point one third, using a non-stretchable tape measure [

53]. Hip circumference is measured around the hips through a point 4 cm below the superior anterior iliac spine [

54]. Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) is calculated for each participant by dividing the waist measurement by the hip measurement.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

The Institutional Review Board of Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University (IRB: Approval Number: # 21-0429) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, reviewed and approved the study. The study’s description, informed consent, and information confidentiality were acquired at the outset of the survey.

2.4. Data Analysis

The acquired data were analyzed using descriptive statistics; frequency and percentage were used for the quantitative variables. The relationships between the respondents’ level of physical activity, health behavior, and personal characteristics were examined using the chi-square test. The collected data have been arranged in an Excel sheet as a database file to be analyzed by using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), which was also utilized to measure the distribution of frequencies of the variables under consideration. The Chi-square test is used to analyze the association between variables.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Data

The participant demographics indicate that the vast majority of respondents, 98.0% (n=150), speak Arabic, with only 2.0% (n=3) speaking English. In terms of age, the largest group is 18-year-olds, making up 49.0% (n=75) of the participants, followed by 19-year-olds at 41.2% (n=63). Most participants, 92.8% (n=142), reside with their parents, while a small portion, 7.2% (n=11), live in university housing. Regarding health conditions, most respondents rate their health as Very Good, accounting for 41.8% (n=64), followed by those who rate it as Good at 24.2% (n=37). (See

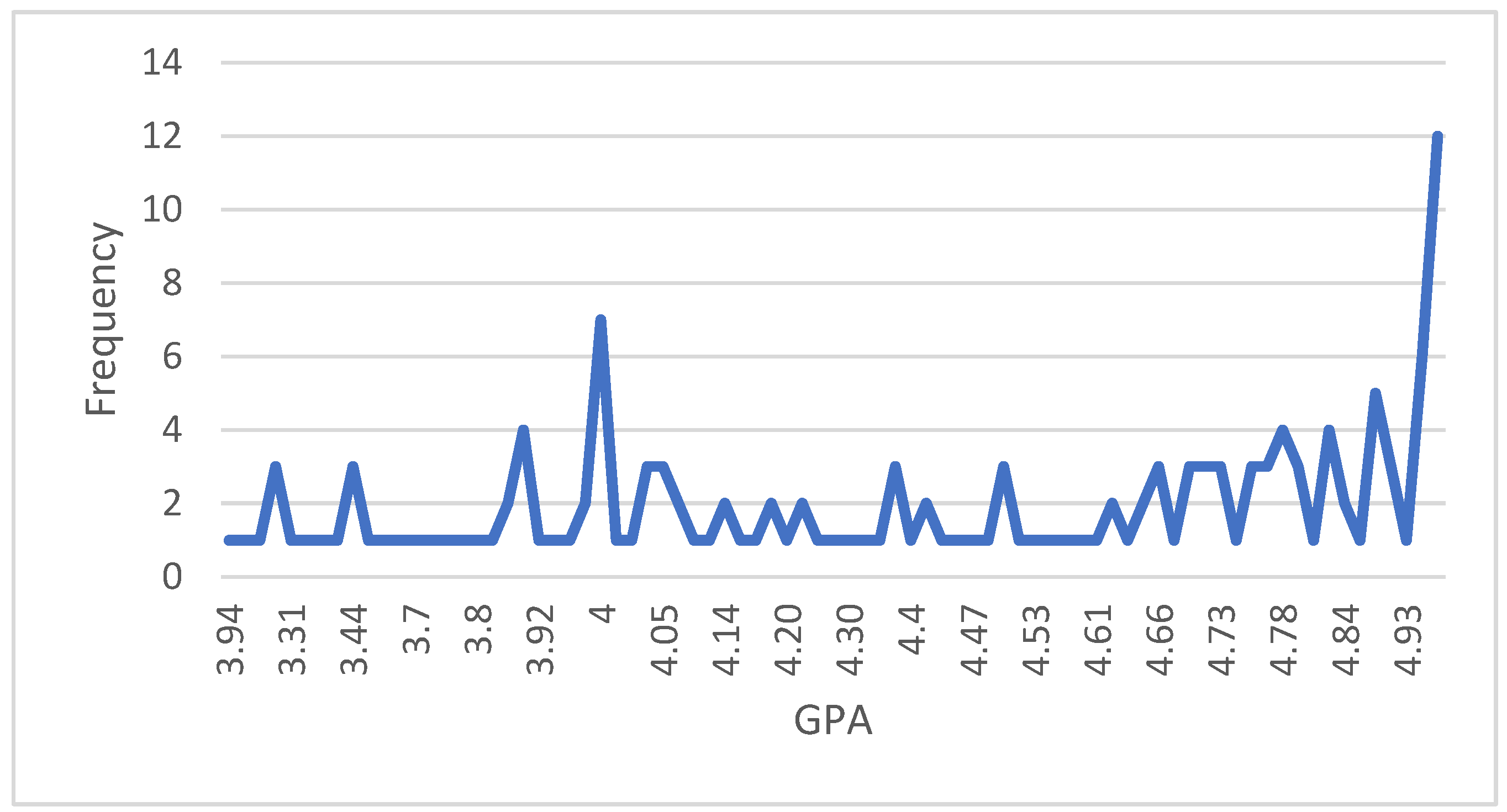

Table 1). All students who participated in our study were unmarried in their foundation year at the university. Their GPA distribution is given in

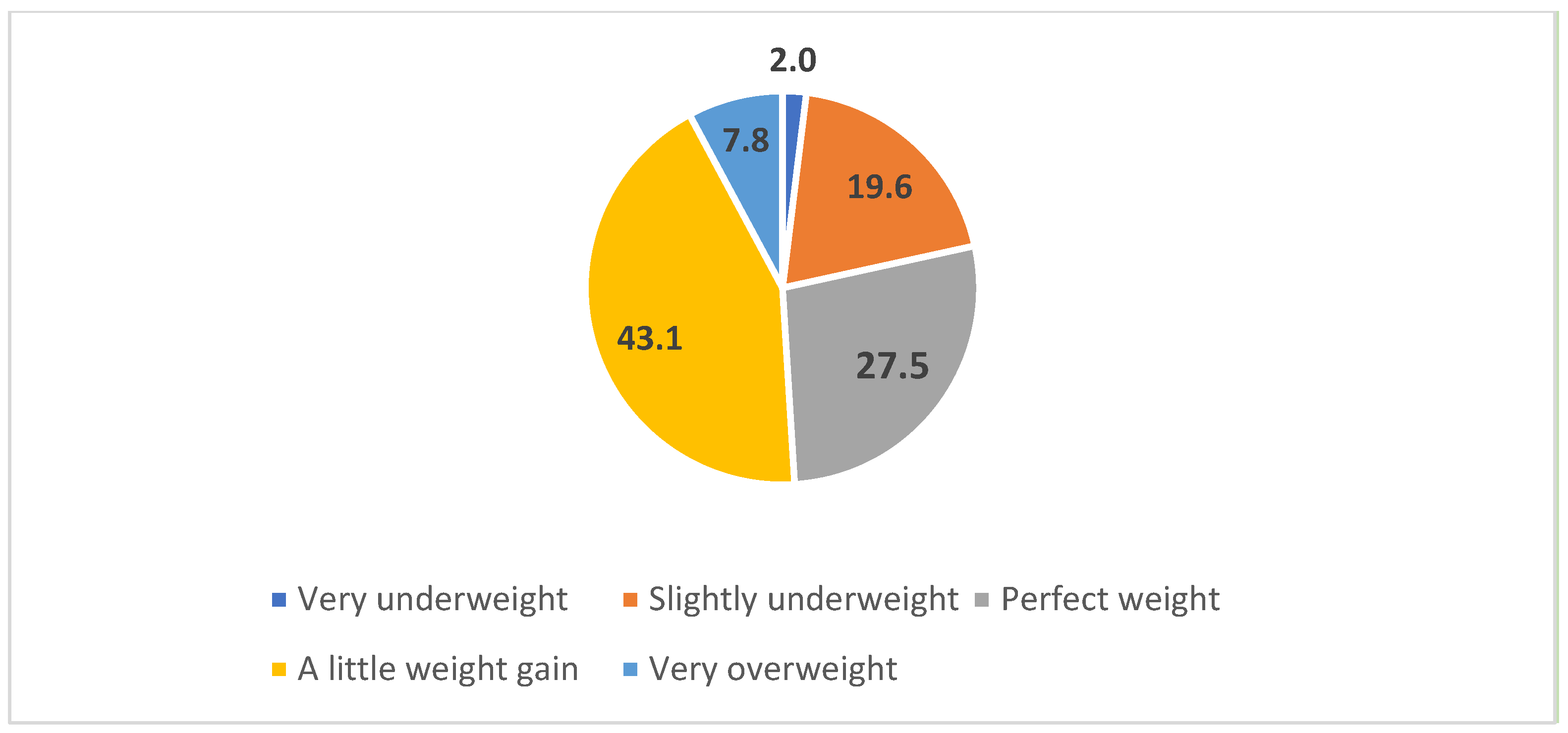

Figure 1. Participants were also asked how they perceive their body weight to be, and their responses are given in

Figure 2 Weight.

3.2. Physical Activity

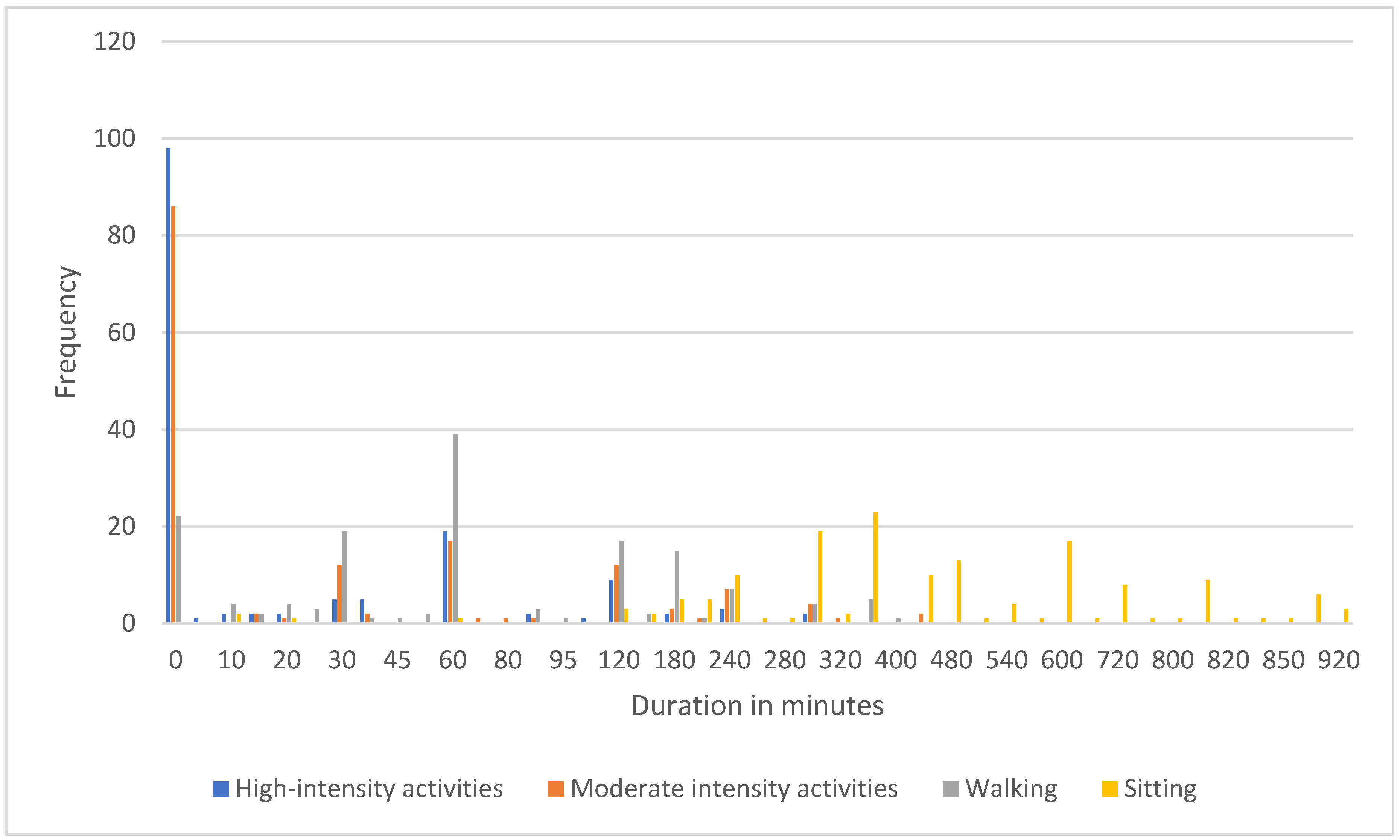

The participant demographics reveal that 66.0% (n=101) do not engage in any high-intensity physical activity. Additionally, 54.9% (n=84) do not participate in moderate-intensity workouts. When it comes to walking, 34.0% (n=52) of participants walk every day, with 25.5% (n=39) spending 60 minutes walking daily. Regarding sedentary behaviour, 15.0% (n=23) of participants sit for 360 minutes (6 hours) daily. The time duration spent on high-intensity and low-intensity activities, walking, and sitting is shown in

Figure 3.

3.3. Life Experiences

The participant responses indicate that 54.2% (n=83) have avoided being reminded of a frightening or upsetting experience by staying away from certain places, people, or activities. Additionally, 66.0% (n=101) have lost interest in activities that were once important or enjoyable. A significant portion, 63.4% (n=97), began to feel more isolated or distant from other people, while 40.5% (n=62) found it hard to have love or affection for other people. Only 17.6% (n=27) began to feel that there was no point in planning for the future. Furthermore, 65.4% (n=100) had more trouble than usual falling asleep or staying asleep, and 66.7% (n=102) became jumpy or easily startled by ordinary noises or movements.

3.4. CES-D

The majority response for each statement regarding feelings during the past week reveals that 36.6% (n=56) were rarely bothered by things that usually do not bother them, while 34.6% (n=53) often had trouble keeping their mind on what they were doing. Similarly, 34.6% (n=53) often felt that everything they did was an effort. Depression was rarely felt by 29.4% (n=45) of the participants. Hopefulness about the future was felt a little (a day or two) by 37.9% (n=58). Fearfulness was often experienced by 27.5% (n=42), and restless sleep was often reported by 28.1% (n=43). Happiness was equally felt a little and often by 37.9% (n=58) of participants. Loneliness was rarely felt by 31.4% (n=48), and 43.8% (n=67) rarely found it difficult to get going. Scores were assigned from 1-4 for rarely to most days. The scores were reversed for items 5 and 8. The mean and standard deviation and complete responses are given in

Table 2.

3.5. Nutrition

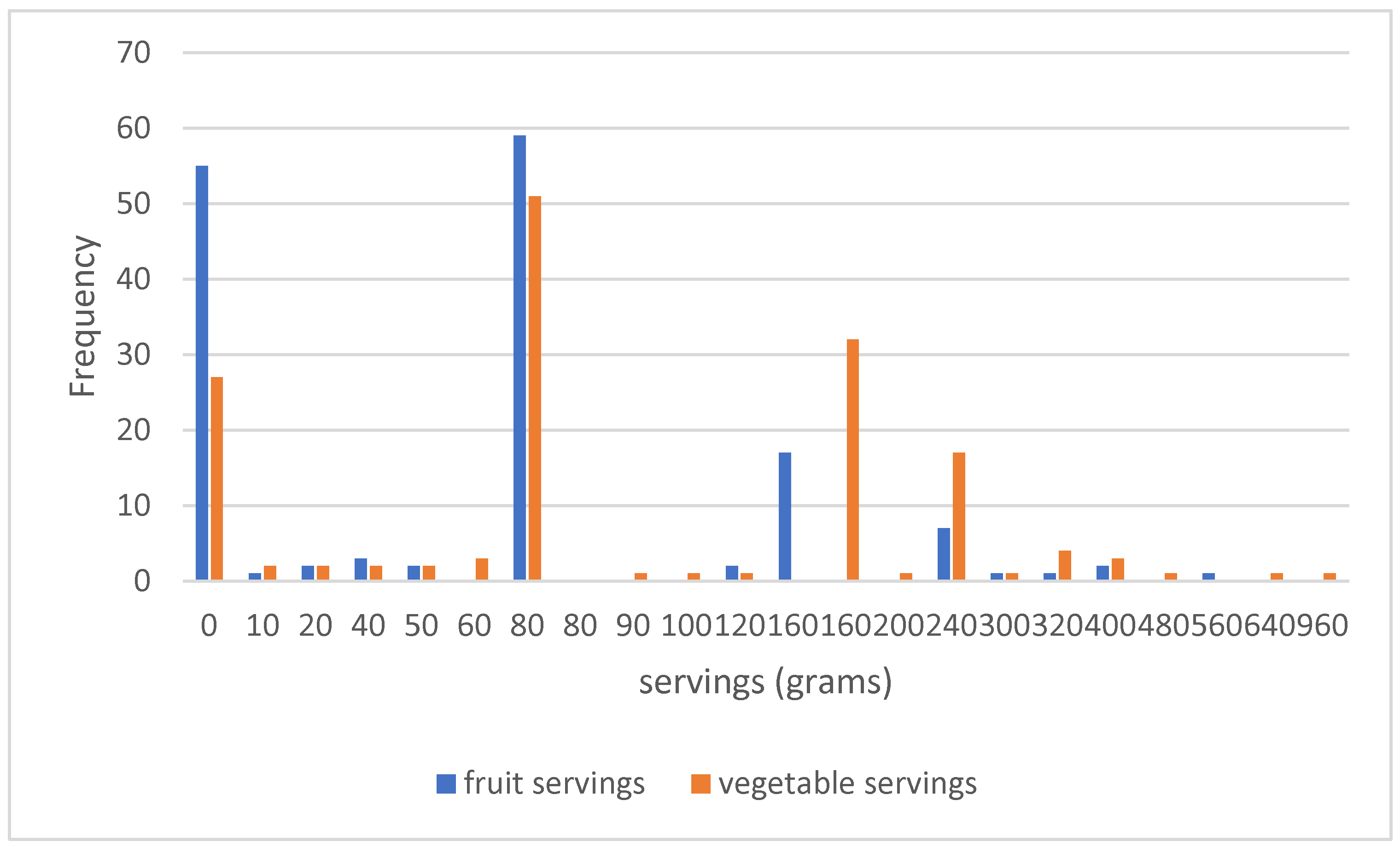

The responses indicate that breakfast is consumed occasionally by 35.3% (n=54) of participants, with 34.6% (n=53) eating it almost every day and 30.1% (n=46) rarely having it. Most participants, 52.9% (n=81), have two meals a day, while 24.2% (n=37) have three meals a day. When it comes to between-meal snacks, 35.3% (n=54) have two snacks a day, followed by 28.8% (n=44) who have one snack a day. Meals with meat are consumed seven times a week by 31.4% (n=48) of participants, and 30.1% (n=46) consume them either once or three times a week. Lastly, 43.1% (n=66) usually add salt to their meals, while 28.8% (n=44) add it occasionally. The fruit and vegetable servings consumed by the participants in the last 7 days are given in

Figure 4.

3.6. Food Consumption

The responses indicate that 24.8% (n=38) of participants consumed chocolate or candy 3-6 times in the last 7 days. Sugared tea or coffee was consumed once daily by 25.5% (n=39) of participants. When it comes to soft drinks, 48.4% (n=74) drank them less than once per day in the last 30 days. The frequency of fast-food consumption in the last 30 days was highest for one time, with 22.9% (n=35) of participants reporting this frequency. The complete response is given in

Table 3. Scores were assigned for the consumption frequency, 0=never to 6/7=more than once a day, and 0-never and 7- for all 7 days. A cumulative score of unhealthy food habits was calculated, with the least possible score of 0 and the highest possible score of 26. The lowest score of 1 was obtained by 1.3% (n=2) and the highest score of 22 was obtained by 0.7% (n=1).

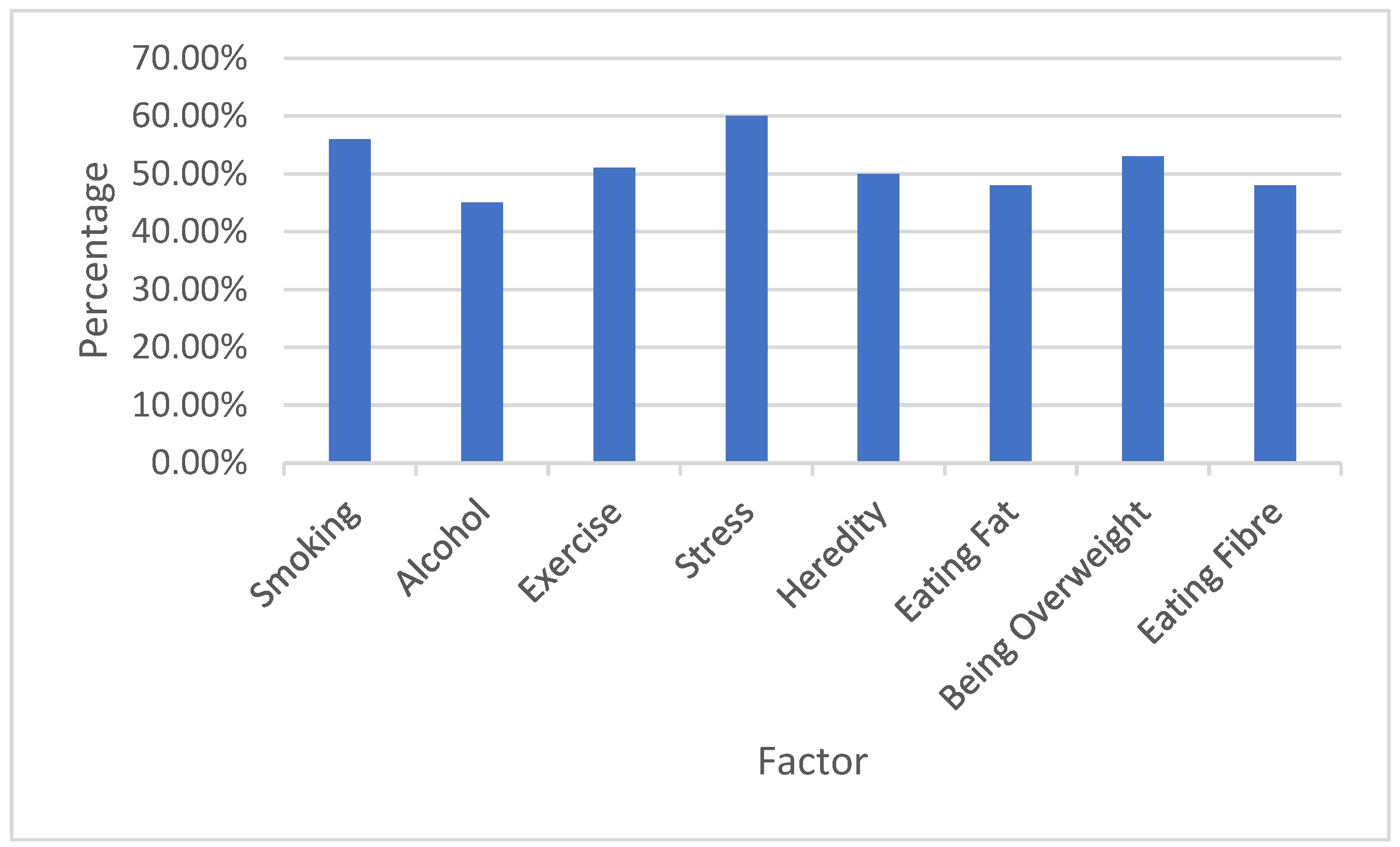

The participants’ perceptions of various factors influencing health problems were analyzed. Stress emerged as the most recognized factor, with 60% of participants identifying it as a major influence on health issues such as heart disease, lung cancer, mental illness, breast cancer, and high blood pressure. Smoking was also prominently identified, with 56% of participants acknowledging its impact across the same health conditions. Being overweight was recognized by 53% of the respondents, highlighting its perceived role in contributing to multiple health problems. Exercise was identified by 51% of participants, indicating awareness of its importance in maintaining health. Heredity, with 50% recognition, underscores the acknowledgment of genetic predispositions in health. Both eating fat and eating fiber were identified by 48% of participants, reflecting an understanding of dietary impacts on health. Alcohol was noted by 45% of respondents as a contributing factor. (See

Figure 5)

3.7. Sleep

The data reveals that the most common duration of sleep among participants is 8 hours, reported by 20.3% (n=31) of respondents. This is followed by 6 hours of sleep, reported by 17.6% (n=27), and 7 hours of sleep, reported by 15% (n=23). In terms of sleep problems, 30.7% (n=47) of participants reported having moderate sleep problems, while 27.5% (n=42) reported both light and intense sleep problems. Only 14.4% (n=22) reported having no sleep problems.

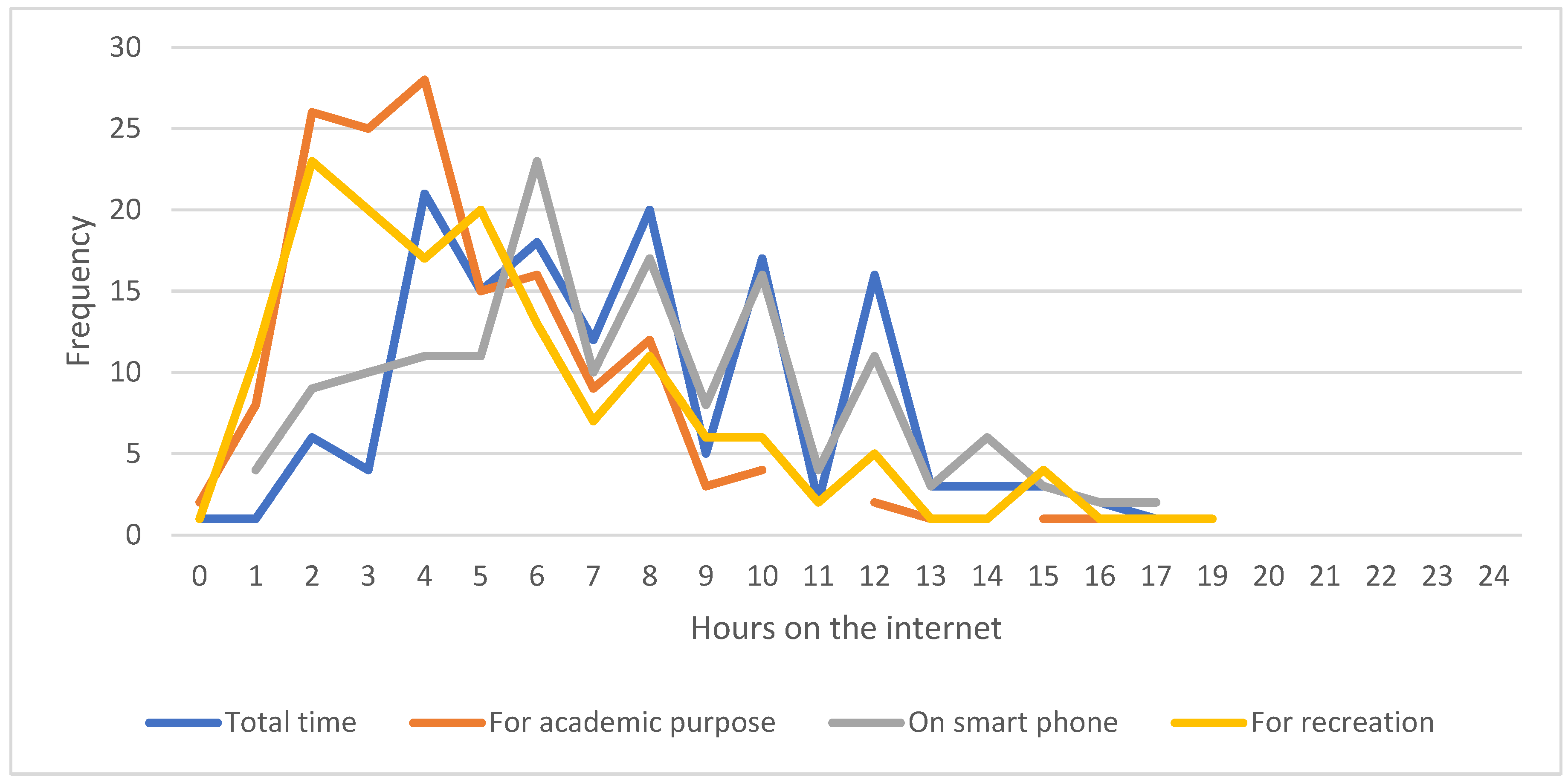

3.8. Internet Usage

The majority of participants spent 4 hours on the internet in total, reported by 13.7% (n=21) of respondents. For academic purposes, the highest frequency was also 4 hours, reported by 18.3% (n=28) of participants. When using a smartphone, the most common duration was 6 hours, reported by 15.0% (n=23) of respondents. For recreational purposes, the maximum response was 2 hours, reported by 15.0% (n=23) of participants. (See

Figure 6)

The majority of participants, 68.0% (n=104), feel preoccupied with the Internet and/or smartphone. A smaller portion, 47.7% (n=73), feel the need to use the Internet and/or smartphone with increasing amounts of time to achieve satisfaction. About 52.3% (n=80) have repeatedly made unsuccessful efforts to control, cut back, or stop Internet and/or smartphone use. Similarly, 49.0% (n=75) feel restless, moody, depressed, or irritable when attempting to cut down or stop Internet and/or smartphone use. A significant majority, 69.3% (n=106), stay online longer than originally intended. Only 26.1% (n=40) have jeopardized or risked the loss of significant relationships, jobs, educational, or career opportunities because of the Internet and/or smartphone use. Additionally, 26.8% (n=41) have lied to family members, therapists, or others to conceal the extent of their involvement with the Internet and/or smartphones. Finally, 76.5% (n=117) use the Internet and/or smartphones as a way of escaping from problems or relieving a dysphoric mood.

3.9. Life

Responses for the 7 items were collected on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1-strongly disagree to 7-strongly agree. The results indicate varying tendencies among participants regarding their perceptions of control and helplessness in their lives. On average, participants tend to somewhat disagree with the statement “There is little I can do to change many of the important things in my life” (Mean = 2.72, SD = 1.172), suggesting a moderate sense of control. Participants also show a slight tendency to agree with feeling helpless in dealing with problems (Mean = 3.1, SD = 1.236). There is a moderate agreement with the notion that achieving desired outcomes is in their own hands (Mean = 3.63, SD = 1.18), and a stronger agreement that future outcomes depend on themselves (Mean = 4.01, SD = 1.064). Conversely, there is a slight disagreement with having little control over things that happen to them (Mean = 2.67, SD = 1.18). Finally, participants tend to moderately agree that they can accomplish anything they set their mind to (Mean = 3.35, SD = 1.155).

The responses reveal that the highest percentage of participants, 43.1% (n=66), completely disagreed with the statement “If I were sick and needed someone to take me to a doctor, I would have trouble finding someone.” Similarly, 32.0% (n=49) of participants correctly agreed with the statement “I feel that there is no one I can share my most private concerns.” Finally, the highest response for the statement “I feel a strong emotional bond with at least one other person” was correct, with 29.4% (n=45) of participants agreeing strongly. Complete responses are given in

Table 4.

To assess the participants’ perception of their happiness data for 4 items were gathered in a 7-point Likert scale. Scores were assigned from 1=’not a very happy person to 7=’a very happy person. The results indicate that participants generally consider themselves to be happy, with a mean score of 3.67 (SD = 1.701) for the statement “In general, I consider myself a very happy person.” Compared to their peers, participants also tend to view themselves as happier, with a mean score of 3.54 (SD = 1.743). When asked to what extent they identify with the characterization of people who are generally very happy and enjoy life regardless of circumstances, participants had a mean score of 3.46 (SD = 1.777). Conversely, the extent to which participants identify with the characterization of people who are generally not very happy, though not depressed, yielded a mean score of 3.2 (SD = 1.722). Overall, these results suggest a moderate tendency among participants to perceive themselves as happy individuals.

3.10. Weight, Physical Activity, and Happiness

Pearson’s correlation concluded that the health condition categories (Poor to Excellent) and the number of physical activity days per week were positively correlated, r(151) = 0.03, p = 0.68. Indicating students who perceived their health in better condition were more physically active although it was not statistically significant.

Among the participants, the weight categories (Very underweight to Very overweight) and the number of physical activity days per week were negatively correlated, r(151) = -0.14, p = 0.13, indicating that as weight category increases, the number of physical activity days tends to slightly decrease, though this relationship is not statistically significant.

In order to assess the relationship between students’ mental health and physical activity and weight, Pearson’s correlation analysis was conducted between cumulative scores of responses to the CES-D instrument and physical activity and weight. The correlation between the CESD score and the number of physical activity days per week was weakly negative, r(151) = -0.11, p = 0.23. This indicates a weak trend where higher CES-D scores (indicating depression) are associated with fewer days of physical activity, but this relationship is not statistically significant. Further, the correlation between the CES-D score and weight categories (ranging from Very underweight to Very overweight) was also weakly negative, r(151) = -0.06, p = 0.53. This suggests a very slight trend where higher CES-D scores are associated with higher weight categories, but again, this relationship is not statistically significant.

The multiple regression analysis aimed to understand how weight categories and CESD scores together influence the number of physical activity days per week among the participants. The results indicated a weak and statistically nonsignificant relationship. The model explained only 3.6% of the variability in physical activity days R2 = 0.036. Specifically, each unit increase in weight category was associated with a decrease of 1.03 physical activity days (p = 0.112), and each unit increase in CESD score was associated with a decrease of 0.139 physical activity days (p = 0.197). These findings suggest that other factors may play a more significant role in influencing physical activity levels.

There was no statistically significant difference between the weight groups a and sleep problems determined by one-way ANOVA (F (3, 107) = 1.99, p = 0.12). Further, there was no statistically significant difference between physical activity and sleep problems as determined by one-way ANOVA (F(3, 107) = 0.39, p = 0.76).

4. Discussion

The demographic findings of this study offer valuable insights into the participants’ group. Most respondents (98%) are native Arabic speakers, reflecting the linguistic and cultural context of the study such as the high percentage of participants young adults, are residing with their parents (92.8%) indicates a strong familial support system. The age distribution is particularly among young adults, with 18- and 19-year-olds which aligns with the study’s focus on university-age students, suggesting that the university age group in Saudi is from 18 to 25 years of age. This could influence their academic and personal lives, such as access to resources, stress levels, and social interactions. The positive self-reported health ratings, with the majority of participants considering themselves in “Very Good” or “Good” health, are encouraging. Which indicates that participants perceive their overall physical and mental well-being to be in excellent condition. which suggests a positive attitude towards health and a general sense of well-being. However, it is important to note that self-assessment of health may not always accurately reflect underlying health conditions. Results of this study indicate the majority of the adolescent participants are gaining weight which could be due to the hormonal changes that occur at this life stage [

55]. Another study proved that adolescents are more susceptible to being overweight or obese due to several factors. These include frequent eating, using electronics for extended periods of time, having an obese family history, and believing that obesity is not a disease [

56]. The acquired grade point average (GPA) for the participants is acquiring 4 and 4.96, which indicates the majority are striving to get admitted into a highly competitive program that requires a high GPA.

4.1. Physical Activity

More than half of the study participants do not work out at a moderate to high intensity, and a sizable majority do not engage in high-intensity physical activity either. Participants of this study (34%) walk every day, which indicates their engagement in regular physical activity. Walking is a simple yet effective form of exercise that can provide numerous health benefits, including improved cardiovascular health, weight management, and reduced risk of chronic diseases while 25% of participants walk for 60 minutes which suggests insufficient physical activity that does not meet the recommended guidelines for moderate-intensity activity. Many health organizations recommend at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise per week [

57]. These findings align with numerous studies that have highlighted the prevalence of sedentary lifestyles and low physical activity levels in many populations. For instance, according to a recent study [

58], 1.8 billion adults worldwide—roughly one-third (31%) of the adult population—are physically inactive. In other words, they fall short of the global recommendations, which call for 150 minutes or more a week of moderate-intense physical activity. In the same study, adolescent girls were less active than adolescent boys, with 85% vs. 78%, not meeting WHO guidelines. This indicates the presence of preventing factors that face the study participants that hinder their engagement in walking for longer durations. These could include time constraints, physical limitations, lack of safe walking routes, or personal preferences.

4.2. Life Experiences

The findings of this study showed that participants avoided being reminded of a frightening or upsetting experience. They tried to stay away from certain places, people, or activities. They lost interest in activities that were once important or enjoyable, felt more isolated or distant from other people, and found it hard to have love or affection for other people. These behaviors are often protective mechanisms that participants developed to cope with the emotional distress associated with the events they experienced. The experience can lead to a sense of hopelessness and a loss of motivation. As a result, individuals may lose interest in activities that were once enjoyable or important. This can contribute to feelings of isolation and a decreased quality of life. The experiences that they passed through can make individuals feel vulnerable and distrustful of others. This can lead to social withdrawal and a sense of isolation. Isolation can exacerbate feelings of loneliness and depression, making it difficult to recover from the hard experience. It is important to note that these behaviors are not a sign of weakness or a choice. They are often a natural response to difficult events. Participants generally felt they had some degree of control over significant aspects of their lives, rather than feeling helpless.

The results suggest that participants lean towards an internal locus of control. This means they believe they have a significant influence on their own outcomes, rather than attributing them to external factors like luck or fate. A sense of control is often associated with better psychological well-being, reduced stress, and increased motivation. Participants who feel they have agency in their lives may be more likely to engage in proactive problem-solving and pursue their goals. Proactive people can use proactive behavior to better regulate their emotions [

59]. A sense of control is often associated with better psychological well-being, reduced stress, and increased motivation. When individuals believe in their own ability to influence outcomes this can foster motivation and resilience. When faced with challenges, individuals with an internal locus of control may be more likely to persevere health and seek solutions [

60].

The findings of this study offered insights into the cultural dynamics and social networks within Saudi Arabia. The high percentage of participants suggest that there is a strong sense of community and social support within Saudi society. People are likely to feel confident in their ability to find assistance, especially during times of need. This could be attributed to factors such as family ties, and strong neighborhood bonds. Individuals within Saudi society have strong emotional connections and trust in others. This suggests that despite cultural norms or societal challenges, there are still opportunities for deep and meaningful relationships. The highest positive responses concerning the emotional support reinforced the presence of strong emotional bonds within Saudi society. This could be attributed to family ties, friendships, or religious affiliations. The emotional connection with others is a fundamental aspect of human experience and is clearly valued in Saudi culture [

61].

4.3. CES-D

The findings of the study describe the emotional states and experiences of the participants. It suggests that they were generally resilient to minor annoyances but often struggled with concentration, motivation, and sleep. While depression was uncommon, fearfulness and restlessness were frequent. Happiness and loneliness were experienced to varying degrees.

While a considerable number of participants skip breakfast, it is still a common practice, suggesting its importance in daily nutrition. The prevalence of snacking indicates that participants are seeking additional nourishment between meals, which can be beneficial for overall energy levels and nutrient intake. The high rate of meat consumption suggests that it’s a staple in many participants’ diets. This could have implications for health outcomes, depending on the types of meat consumed and preparation methods. The widespread use of salt is a concern, as excessive sodium intake can contribute to high blood pressure and other health issues [

62]. Efforts to reduce salt consumption could be beneficial for participants’ overall well-being.

4.4. Food Consumption

A relatively small portion of participants consumed chocolate or candy 3-6 times a week, sugared tea or coffee was a daily habit for 25.5%quarter of participants, while the majority of participants consumed soft drinks less than once a day and one-time consumption of fast food was the most common frequency, reported by participants. The high consumption rates of sugary beverages and fast food, even if not daily, suggest a significant portion of the population may be at risk for health issues associated with excessive sugar and unhealthy fats [

63].

4.5. Factors Influence Health

The findings suggest that participants have a general awareness of the factors that can influence health problems. Stress, smoking, and overweight emerged as the most commonly recognized factors, highlighting their perceived importance. The acknowledgment of exercise and heredity indicates an understanding of the roles of lifestyle and genetics in health. The recognition of both eating fat and fiber suggests a growing awareness of the importance of balanced nutrition.

The current data shows that the most common sleep duration among participants is 8 hours, followed by 6 and 7 hours. However, a significant number of participants reported experiencing sleep problems, with moderate sleep problems being the most common. A study conducted by [

64] in Saudi Arabia showed that 13.4% of the respondents specifically had obstructive sleep apnea, and 28.8% of the respondents reported having sleep disorders. This suggests that while 8 hours of sleep may be the ideal duration for many, achieving quality sleep can be a challenge for a considerable portion of the participants. Factors contributing to sleep problems such as lifestyle factors that include stress, irregular sleep schedules, excessive screen time, and caffeine consumption can all contribute to sleep disturbances [

65]. Certain medical conditions, including anxiety, depression, and chronic pain, can also disrupt sleep patterns [

66]. Further research is needed to understand the factors contributing to sleep problems and develop effective interventions to improve sleep quality.

The data suggests that a significant portion of the participants are heavy users of the internet and smartphones, spending a considerable amount of time online. The findings align with the criteria for internet addiction, including preoccupation, tolerance, withdrawal symptoms, and negative consequences. While a majority reported negative consequences like staying online longer than intended, a smaller percentage experienced severe issues like jeopardizing relationships or lying. This could suggest that many participants are aware of the negative impacts but are unable to quit due to addiction-like behaviors. The findings highlight the need for effective interventions to help individuals who are struggling with excessive internet and smartphone use. These interventions could include cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based techniques, and digital detox strategies [

67].

The correlation analysis between CES-D scores and physical activity days per week, as well as CES-D scores and weight categories, revealed weak negative trends. However, both correlations were statistically non-significant. This suggests that while there might be a slight tendency for individuals with higher depressive symptoms to engage in less physical activity or have higher weight categories, these relationships are not strong enough to be definitively established. The multiple regression analysis of the current study sought to examine how weight categories and CES-D scores together influence physical activity levels. The model explained a very small portion of the variability in physical activity days, indicating that other factors are likely more influential. While there were negative associations between both weight categories and CES-D scores with physical activity days, these relationships were again not statistically significant. The ANOVA analyses comparing weight groups and physical activity levels with sleep problems did not find any significant differences. This suggests that sleep problems are not significantly associated with either weight categories or physical activity levels in this sample.

4.6. Limitations of the Study

The sample size was small to make generalizability of the findings to the wider youth population. While CES-D is a widely used measure of depression, it may not capture the full spectrum of mental health issues. Other factors like anxiety, stress, or bipolar disorder might also influence physical activity. The self-report method of collecting data might have limitations in terms of accuracy or participant compliance.