Submitted:

06 October 2024

Posted:

07 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

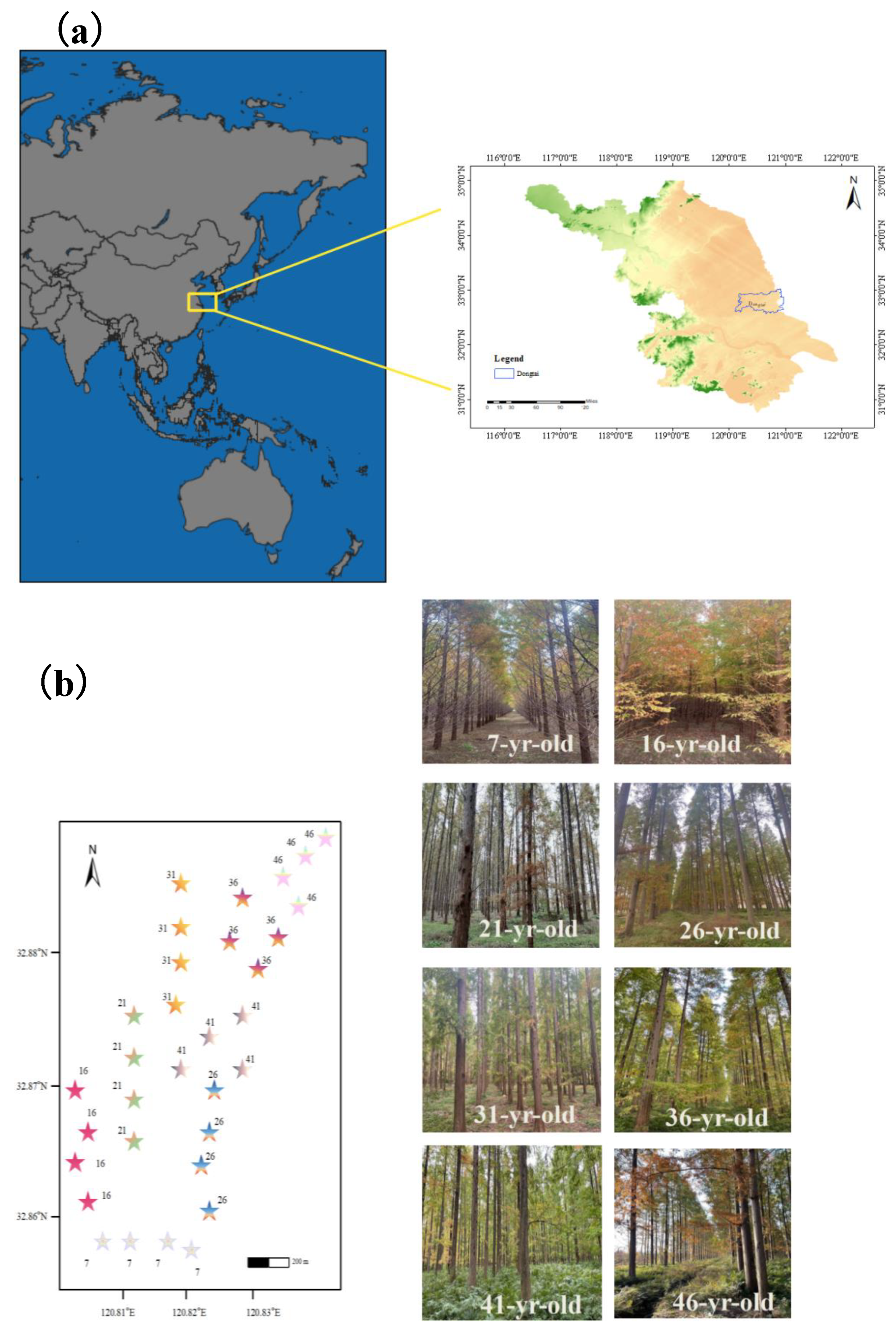

2.1. Site Description and Experimental Design

2.2. Collection and Identification of Soil Macrofauna

2.3. Measurement of Soil and Surface Litter Physicochemical Properties

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

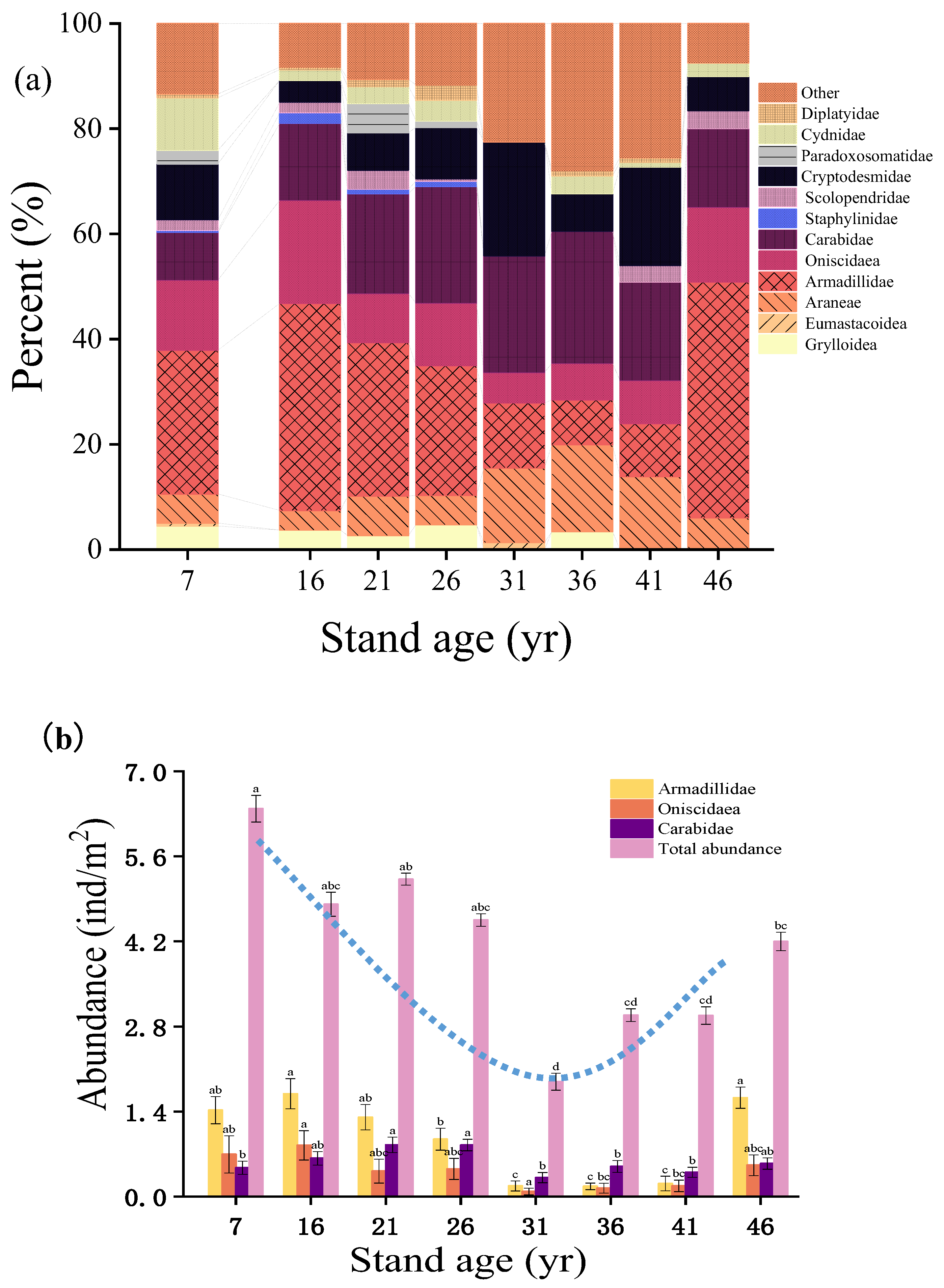

3.1. Composition of Soil Macrofauna Communities as Forest Development

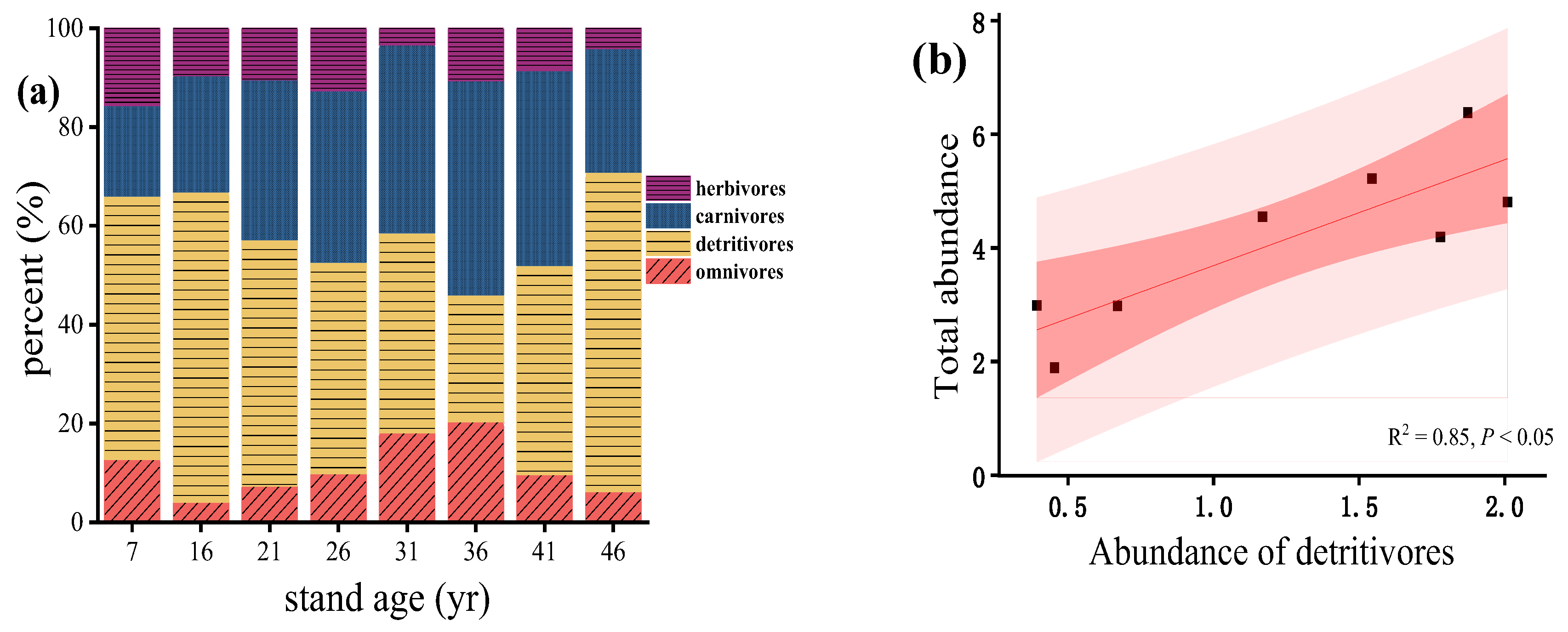

3.2. Distribution of Functional Groups in Soil Macrofauna Communities

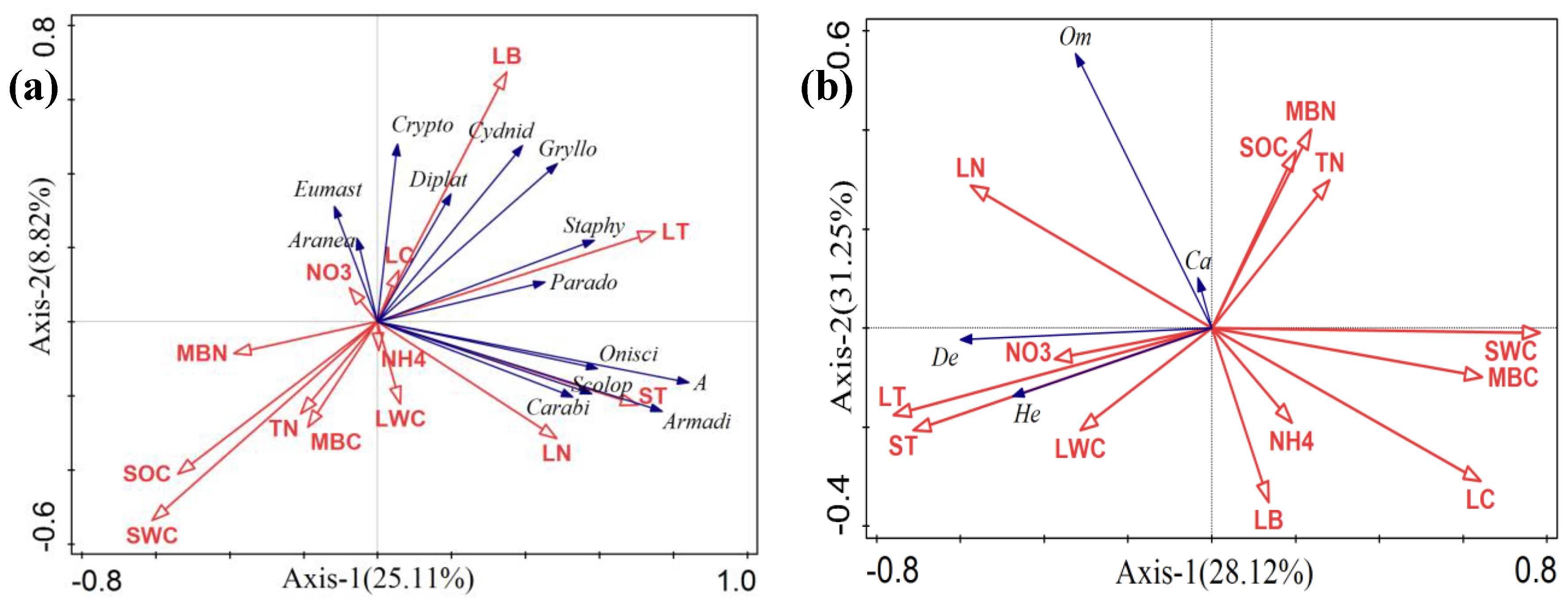

3.3. Associations between Environmental Factors and Soil Macrofauna Communities

4. Discussion

4.1. Abundance of Soil macrofauna Changes with Plantation Development

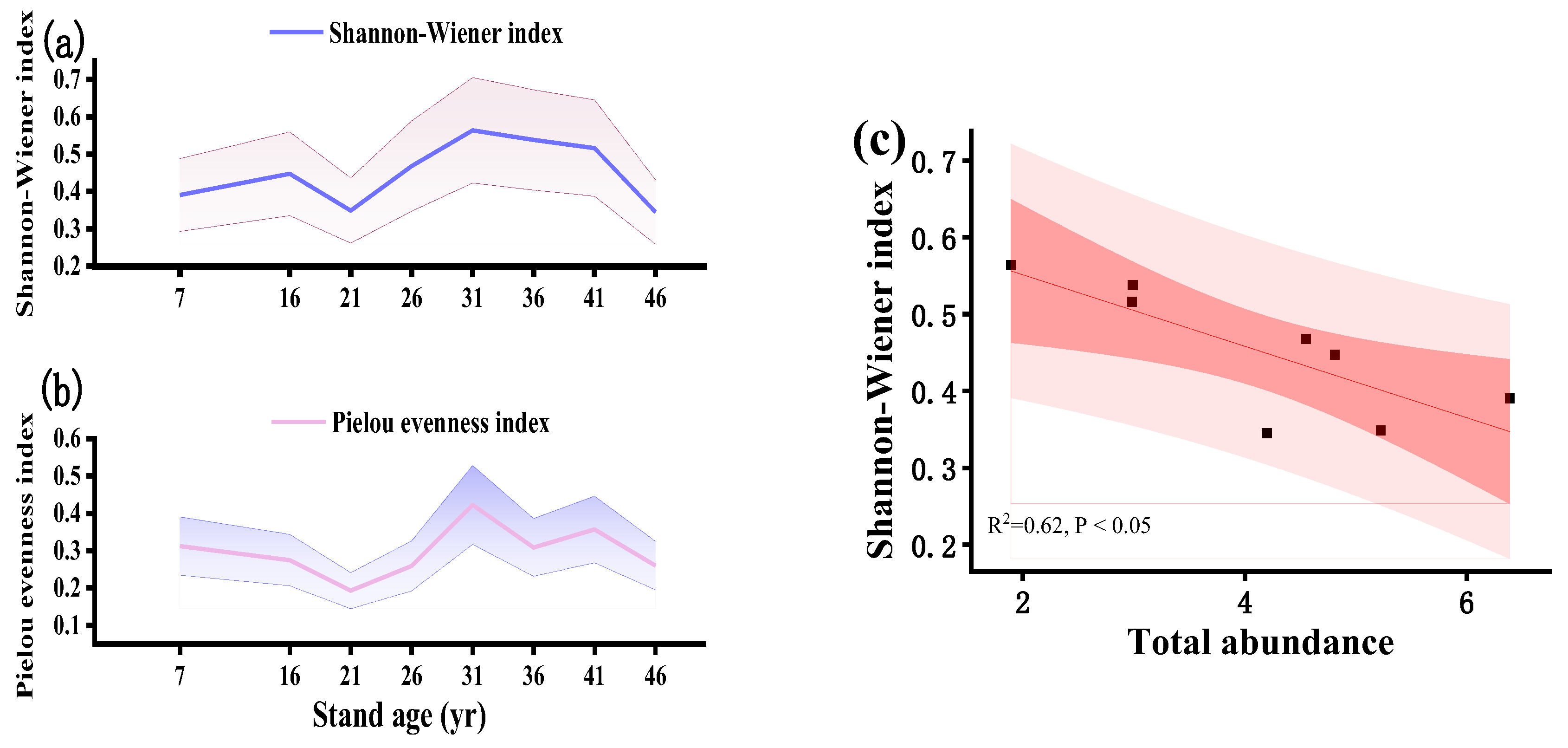

4.2. Relationships between the Total Abundance and Diversity of Soil Macrofauna with Plantation Development

4.3. Relationships between the Total Abundance of Soil Macrofauna and Functional Groups with Plantation Development

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wardle, D. A.; Bardgett, R. D.; Klironomos, J. N.; Setälä, H.; van der Putten, W. H.; Wall, D. H. , Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota. Science 2004, 304(5677), 1629–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellers, J.; Berg, M. P.; Dias, A. T. C.; Fontana, S.; Ooms, A.; Moretti, M. , Diversity in form and function: Vertical distribution of soil fauna mediates multidimensional trait variation. Journal of Animal Ecology 2018, 87(4), 933–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidi, C.; Frey, B.; Brunner, I.; Meusburger, K.; Vogel, M. E.; Chen, X. M.; Stucky, T.; Gwiazdowicz, D. J.; Skubala, P.; Bose, A. K.; Schaub, M.; Rigling, A.; Hagedorn, F. , Soil fauna drives vertical redistribution of soil organic carbon in a long-term irrigated dry pine forest. Global Change Biology 2022, 28(9), 3145–3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardgett, R. D.; van der Putten, W. H. , Belowground biodiversity and ecosystem functioning. Nature 2014, 515(7528), 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenhauer, N. , Aboveground-belowground interactions as a source of complementarity effects in biodiversity experiments. Plant and Soil 2012, 351, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo, Y.; Ball, B. A.; Bradford, M. A.; Jordan, C. F.; Molina, M. , Soil fauna alter the effects of litter composition on nitrogen cycling in a mineral soil. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 2011, 43, 1440–1449. [Google Scholar]

- Hedenec, P.; Jose Jimenez, J.; Moradi, J.; Domene, X.; Hackenberger, D.; Barot, S.; Frossard, A.; Oktaba, L.; Filser, J.; Kindlmann, P.; Frouz, J. Global distribution of soil fauna functional groups and their estimated litter consumption across biomes. Scientific Reports 2022, 12 (1).

- Darby, B. J.; Neher, D. A.; Housman, D. C.; Belnap, J. Few apparent short-term effects of elevated soil temperature and increased frequency of summer precipitation on the abundance and taxonomic diversity of desert soil micro- and meso-fauna. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 2011, 43 (7), 1474-1481.

- Payn, T.; Carnus, J.-M.; Freer-Smith, P.; Kimberley, M.; Kollert, W.; Liu, S.; Orazio, C.; Rodriguez, L.; Silva, L. N.; Wingfield, M. J. , Changes in planted forests and future global implications. Forest Ecology and Management 2015, 352, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. T.; He, B.; Guo, L. L.; Yan, X.; Zeng, Y. L.; Yuan, W. P.; Zhong, Z. Q.; Tang, R.; Yang, Y.; Liu, H. M.; Chen, Y. N. Global Forest Plantations Mapping and Biomass Carbon Estimation. Journal of Geophysical Research-Biogeosciences 2024, 129 (3).

- Peng, S.-S.; Piao, S.; Zeng, Z.; Ciais, P.; Zhou, L.; Li, L. Z. X.; Myneni, R. B.; Yin, Y.; Zeng, H. , Afforestation in China cools local land surface temperature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111(8), 2915–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, J.; Liu, Y.-R.; Eldridge, D.; Huang, Q.; Tan, W.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M. , Geologically younger ecosystems are more dependent on soil biodiversity for supporting function. Nature communications 2024, 15(1), 4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, W.; Saqib, H. S. A.; Adnan, M.; Wang, Z.; Tayyab, M.; Huang, Z.; Chen, H. Y. H. , Differential response of soil microbial and animal communities along the chronosequence of Cunninghamia lanceolata at different soil depth levels in subtropical forest ecosystem. Journal of Advanced Research 2022, 38, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M. W.; Zou, X. M. Soil macrofauna and litter nutrients in three tropical tree plantations on a disturbed site in Puerto Rico. Forest Ecology and Management 2002, 170 (1-3), 161-171.

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, P.; Yu, M. K.; Wu, T. G. In Soil organic carbon content and stocks in an age-sequence of Metasequoia glyptostroboides plantations in coastal area, East China, 4th International Conference on Sustainable Energy and Environmental Engineering (ICSEEE), Shenzhen, PEOPLES R CHINA, Dec 20-21; Shenzhen, PEOPLES R CHINA, 2015; pp 1004-1012.

- Bird, S. B.; Coulson, R. N.; Fisher, R. R. Changes in soil and litter arthropod abundance following tree harvesting and site preparation in a loblolly pine (Pinus taeda L.) plantation. Forest Ecology and Management 2004, 202 (1-3), 195-208.

- Scheu, S.; Albers, D.; Alphei, J.; Buryn, R.; Klages, U.; Migge, S.; Platner, C.; Salamon, J. A. , The soil fauna community in pure and mixed stands of beech and spruce of different age: trophic structure and structuring forces. Oikos 2003, 101(2), 225–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G. R.; Zhang, Y. X.; Zhang, S.; Ma, K. M. Biodiversity associations of soil fauna and plants depend on plant life form and are accounted for by rare taxa along an elevational gradient. Soil Biology & Biochemistry 2020, 140.

- Wang, G. L.; Chen, Y. W.; Liu, C. Z.; al., e., Effects of Eco-restoration of Abandoned Farmland on Soil Invertebrate Diversity in the Loess Plateau. Journal of Desert Research 2010, 30, 140-145.

- Yang, X.; Shao, M. A.; Li, T. C.; Gan, M.; Chen, M. Y. , Community characteristics and distribution patterns of soil fauna after vegetation restoration in the northern Loess Plateau. Ecological Indicators 2021, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; You, W. H.; Song, Y. C. , Soil aninal communities in the litter of the evergreen broad-leaved forest at five succession stages in Tiantong. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2005, (03), 466–473. [Google Scholar]

- Wike, L. D.; Martin, F. D.; Paller, M. H.; Nelson, E. A. , Impact of forest seral stage on use of ant communities for rapid assessment of terrestrial ecosystem health. Journal of Insect Science 2010, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, B. M.; Zhang, D. Z.; Cui, J.; Zhang, H. B.; Zhou, C. L.; Tang, B. P. , Biodiversity Variations of Soil Macrofauna Communities in Forests in a Reclaimed Coast with Different Diked History. Pakistan Journal of Zoology 2014, 46(4), 1053–1059. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, J. C.; McCann, K.; Setälä, H.; De Ruiter, P. C. , Top-down is bottom-up:: Does predation in the rhizosphere regulate aboveground dynamics? Ecology 2003, 84(4), 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, R.; Li, T.; Dai, Y. Changes of soil fauna along the non-native tree afforestation chronosequence on Loess Plateau. Plant and Soil 2023, 485 (1-2), 489-505.

- Zhang, Y. K.; Peng, S.; Chen, X. L.; Chen, H. Y. H. , Plant diversity increases the abundance and diversity of soil fauna: A meta-analysis. Geoderma 2022, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Fang, S.; Chen, H. Y. H.; Zhu, R.; Peng, S.; Ruan, H. , Soil Aggregation and Organic Carbon Dynamics in Poplar Plantations. Forests 2018, 9(9), 508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L. R.; Wardle, D. A.; Bardgett, R. D.; Clarkson, B. D. , The use of chronosequences in studies of ecological succession and soil development. Journal of Ecology 2010, 98(4), 725–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, W. Y. Subtropical soil animals of China. Beijing: Science Press: 1992; p 618.

- Yin, W. Y. , Pictorical keys to soil animals of China. Beijing: Science Press: 1998; p 756.

- Potapov, A. M.; Beaulieu, F.; Birkhofer, K.; Bluhm, S. L.; Degtyarev, M. I.; Devetter, M.; Goncharov, A. A.; Gongalsky, K. B.; Klarner, B.; Korobushkin, D. I.; Liebke, D. F.; Maraun, M.; Mc Donnell, R. J.; Pollierer, M. M.; Schaefer, I.; Shrubovych, J.; Semenyuk, II; Sendra, A.; Tuma, J.; Tumova, M.; Vassilieva, A. B.; Chen, T. W.; Geisen, S.; Schmidt, O.; Tiunov, A. V.; Scheu, S., Feeding habits and multifunctional classification of soil-associated consumers from protists to vertebrates. Biological Reviews 2022, 97 (3), 1057-1117.

- Chen, Z. B. , Instumental analysis experiment. Shanghai: Fudan University Press: 2018; p 105.

- Drolc, A.; Vrtovsek, J. , Nitrate and nitrite nitrogen determination in waste water using on-line UV spectrometric method. Bioresource Technology 2010, 101(11), 4228–4233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, R. K. , Methods for the chemical analysis of soil agriculture. Beijing: China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: 2000; p 638.

- Zhou, H. Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D. J.; Zhang, J.; Wei, D. P.; Zhao, Y. B.; Zhao, B.; Li, C. B. , Community characteristics of soil fauna for different canopy density of a Pinus massoniana plantation. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2017, 37(06), 1939–1955. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Sun, D. Y. , Effects of Different Ages of Japanese Larix kaempferi Artificial Forest on Litters and Soil Physicochemical Characteristics. Chinese Agricultural Science Bulletin 2016, 32(01), 12–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, Y. F.; Li, X.; Wan, X. H.; Zou, B. Z.; Wang, S. R.; Huang, Z. Q. Changes of Soil Microbial Community Structure across Different Succession Stages of Secondary Forest. Journal of Subtropical Resources and Environment 2021, 16 (01), 23-28+34.

- Tong, F. C.; Wang, Q. L.; Liu, S. X.; Xiao, Y. H. , Dynamics of soil fauna communities during succession of secondary forests in Changbai Mountain. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology 2004, (09), 1531–1535. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, P. S.; Lin, H. C.; Lin, C. P.; Tso, I. M. , The effect of thinning on ground spider diversity and microenvironmental factors of a subtropical spruce plantation forest in East Asia. European Journal of Forest Research 2014, 133(5), 919–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diekötter, T.; Wamser, S.; Wolters, V.; Birkhofer, K. Landscape and management effects on structure and function of soil arthropod communities in winter wheat. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 2010, 137 (1-2), 108-112.

- Wei, X. X.; Chen, A. L.; Wang, S. Y.; Cao, G. Q.; Cai, P. Q.; Li, S. , A comparative study of soil microbial carbon source utilization in different A comparative study of soil microbial carbon source utilization in different successive rotation plantations of Chinese fir. Chin J Appl Environ Biol 2016, 22(03), 518–523. [Google Scholar]

- Tilman, D. , THE ECOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES OF CHANGES IN BIODIVERSITY: A SEARCH FOR GENERAL PRINCIPLES. Ecology 1999, 80(5), 1455–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staab, M.; Schuldt, A.; Assmann, T.; Bfuelheide, H.; Klein, A.-M. Ant community structure during forest succession in a subtropical forest in South-East China. Acta Oecologica-International Journal of Ecology 2014, 61, 32-40.

- Leibold, M. A.; Holyoak, M.; Mouquet, N.; Amarasekare, P.; Chase, J. M.; Hoopes, M. F.; Holt, R. D.; Shurin, J. B.; Law, R.; Tilman, D.; Loreau, M.; Gonzalez, A. , The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecology Letters 2004, 7(7), 601–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravenek, J. M.; Bessler, H.; Engels, C.; Scherer-Lorenzen, M.; Gessler, A.; Gockele, A.; De Luca, E.; Temperton, V. M.; Ebeling, A.; Roscher, C.; Schmid, B.; Weisser, W. W.; Wirth, C.; de Kroon, H.; Weigelt, A.; Mommer, L. , Long-term study of root biomass in a biodiversity experiment reveals shifts in diversity effects over time. Oikos 2014, 123(12), 1528–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H. Y. H.; Chen, X. L.; Huang, Z. Q. , Meta-analysis shows positive effects of plant diversity on microbial biomass and respiration. Nature Communications 2019, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Zhang, X. P.; Zhang, L. M. , Spatial and temporal variation of soil macro-fauna community structure in three temperate forests. Acta Ecologica Sinica 2013, 33(19), 6236–6245. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, M. P.; Hemerik, L. , Secondary succession of terrestrial isopod, centipede, and millipede communities in grasslands under restoration. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2004, 40(3), 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Soil fauna taxa | Environmental factors | |||||||||||

| MBC | MBN | SOC | NH4+ | NO3- | TN | LC | LN | LB | LT | ST | SWC | |

| (mg kg-1) | (mg kg-1) | (g kg-1) | (mg kg-1) | (mg kg-1) | (g kg-1) | (g kg-1) | (g kg-1) | (g kg-1) | (℃) | (℃) | (%) | |

| TA | -0.344 | -0.399 | -0.779* | 0.13 | -0.308 | -0.643 | -0.007 | 0.594 | 0.534 | 0.65 | 0.67 | -0.63 |

| Oniscidae | -0.017 | -0.215 | -0.711* | 0.089 | -0.264 | -0.529 | -0.163 | 0.671 | 0.447 | 0.6 | 0.638 | -0.591 |

| Cryptodesmidae | -0.226 | 0.081 | -0.563 | 0.41 | -0.114 | -0.755* | -0.028 | -0.285 | 0.239 | 0.264 | 0.161 | -0.508 |

| Cydnidae | -0.521 | -0.331 | -0.738* | 0.129 | -0.453 | -0.906** | -0.132 | 0.251 | 0.691 | 0.307 | 0.122 | -0.59 |

| Armadillidae | -0.024 | -0.242 | -0.528 | 0.034 | -0.344 | -0.422 | -0.19 | 0.785* | 0.216 | 0.481 | 0.693 | -0.401 |

| Grylloidea | -0.431 | -0.299 | -0.911** | 0.229 | -0.152 | -0.594 | 0.186 | 0.263 | 0.839** | 0.595 | 0.291 | -0.753* |

| Araneae | -0.809* | -0.687 | 0.108 | -0.296 | -0.045 | -0.171 | 0.27 | -0.16 | 0.306 | 0.071 | -0.074 | 0.071 |

| Carabidae | -0.214 | -0.233 | -0.375 | 0.307 | -0.048 | 0.138 | 0.293 | 0.24 | 0.299 | 0.49 | 0.579 | -0.214 |

| Scolopendridae | -0.326 | -0.543 | -0.31 | -0.243 | -0.105 | -0.443 | 0.054 | 0.667 | 0.001 | 0.56 | 0.794* | -0.323 |

| Diplatyidae | -0.187 | 0.053 | -0.491 | 0.65 | -0.064 | -0.012 | 0.248 | -0.271 | 0.445 | 0.358 | 0.279 | -0.293 |

| Variables | Soil macrofauna composition | Functional groups | ||||||

| Explains % | Contribution % | Pseudo-F | Variables | Explains % | Contribution % | Pseudo-F | ||

| MBC | 3.9 | 7.4 | 1.2 | SWC | 17.3 | 51 | 26.3** | |

| MBN | 5.2 | 10 | 1.7* | LT | 6.9 | 20.5 | 11.5** | |

| SOC | 7.9 | 15 | 2.7* | LN | 2.1 | 6.1 | 3.5* | |

| NH4+ | 1.5 | 2.8 | 0.5 | ST | 2 | 5.9 | 3.4* | |

| NO3- | 3 | 5.8 | 1 | LC | 1.6 | 4.6 | 2.7* | |

| TN | 4.6 | 8.7 | 1.6 | NO3 | 0.9 | 2.8 | 1.7 | |

| LC | 2 | 3.9 | 0.8 | LB | 0.9 | 2.8 | 1.7 | |

| LN | 3.7 | 7 | 1.4 | LWC | 0.7 | 2.2 | 1.3 | |

| LB | 4.4 | 8.4 | 1.7* | SOC | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.7 | |

| LT | 1.7 | 3.1 | 0.6 | MBC | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.7 | |

| ST | 9.9 | 18.8 | 3.7* | MBN | 0.3 | 1 | 0.6 | |

| LWC | 2.6 | 5 | 1 | TN | 0.2 | 0.6 | 0.3 | |

| SWC | 2.3 | 4.3 | 0.9 | NH4 | <0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).