Submitted:

06 October 2024

Posted:

07 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. History of Submerged Prehistory

1.2. Citizen Sources

1.3. Depth Dependent Likelihood of Detecting Prehistoric Sites

1.4. Models for Detecting Sites

1.5. The Utilization of Paleosols and Rocky Coastal Areas by Prehistoric Populations

1.6. The Importance of Archaeological Investigations to Corroborate the Anthropogenic Nature of a Site

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

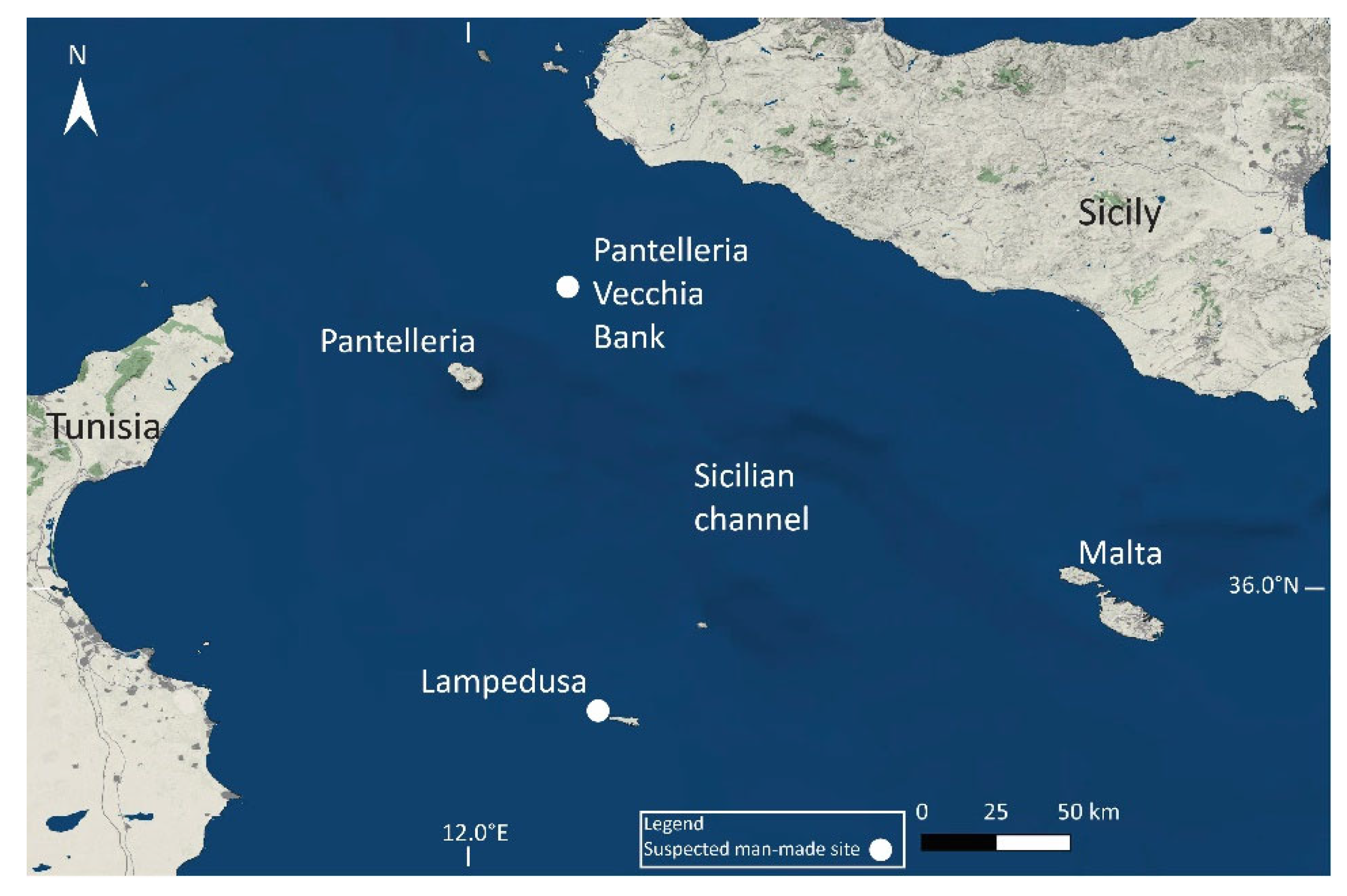

3.1. The Pantelleria Vecchia Bank

- Archaeological setting:

- Geological setting:

- Past studies:

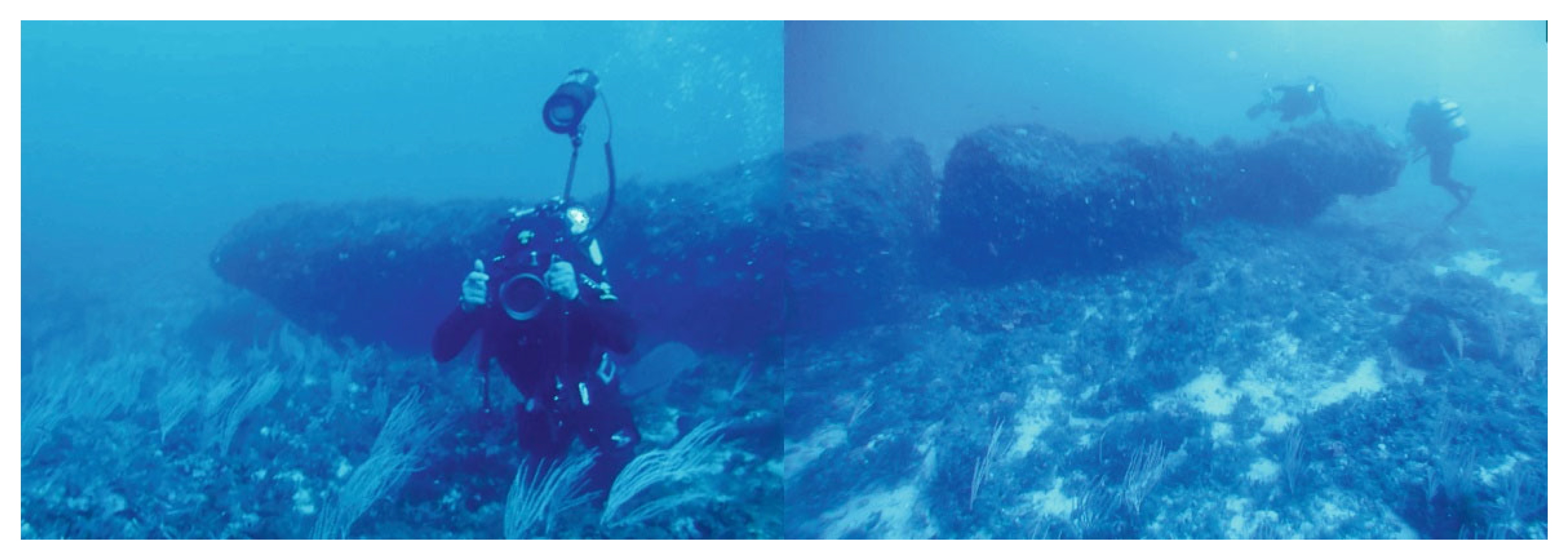

- Ridge 1; is an 820m long stone ridge whose lower part is covered with sediment while the upper part comprises what Lodolo et al. (58) describe as "horizontally arranged" stone blocks 0.5m thick, some rectangular in shape, with the largest measuring ~3.4m (Figure 2A and Figure 3). Based on thin section petrography analysis of samples collected from the features, their lithology was classified as bioclastic sandstone (SI Table S1). The ridge was interpreted as having been initially embedded in coarse sand during a low sea-level stand some 40,000 BP. Lodolo et al. (58) suggest that later, ~9000 BP, the natural deposit was modified and stone blocks intentionally erected by prehistoric inhabitants of the region to serve as a coastal defense against sea-level rise.Figure 3. Rock blocks on Ridge 1 after [58].Figure 3. Rock blocks on Ridge 1 after [58].

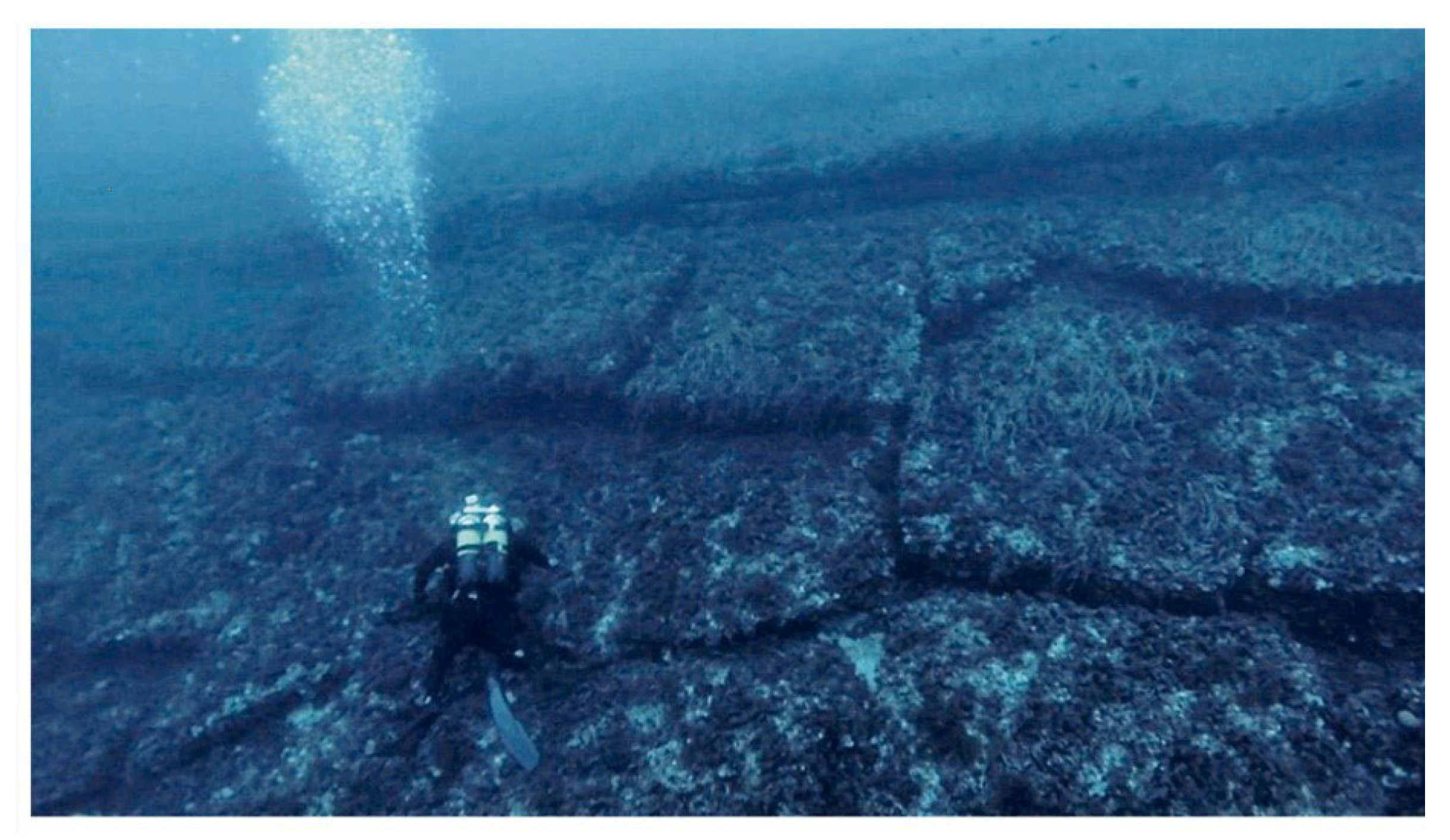

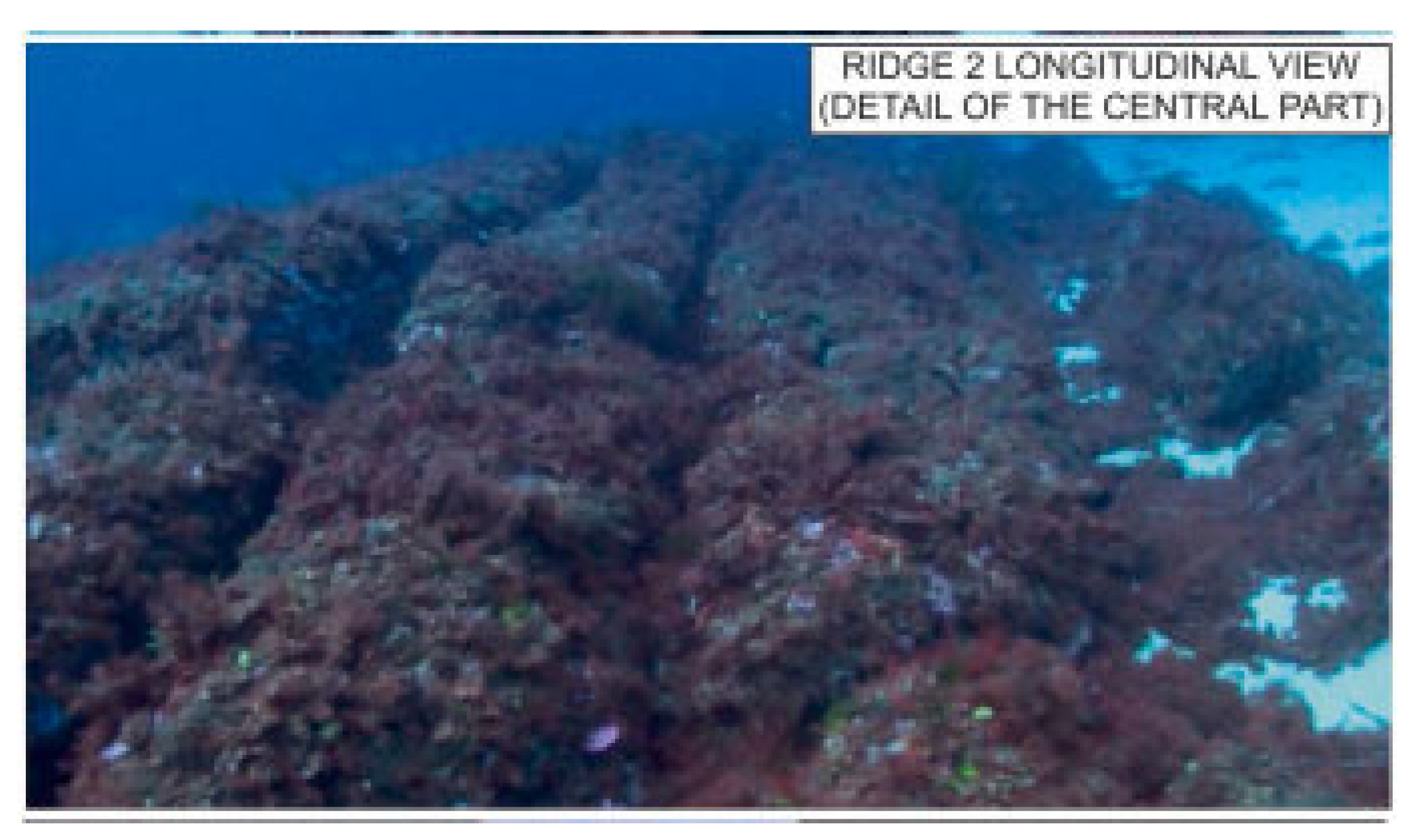

- Ridge 2; is an 82m long and 6–8m wide stone feature that lies perpendicular to, and 100 m north-east of the west end of Ridge 1 (Figure 2B and Figure 4). It too is characterized by rectangular stone blocks that rise 1m above the surrounding seafloor. Based on thin section petrography analysis of samples collected from the features, their lithology was classified as bioclastic sandstone (SI Table 1). In their 2023 paper [58], Lodolo and Ben Avraham suggested that “It seems unlikely that this concentration of peculiar and geometrically regular structures would develop by natural processes in this small (∼0.5 km) study area. …………… In view of the above, it seems possible that the two ridges are associated with human occupation”.Figure 4. Rock blocks on Ridge 2 after [58].Figure 4. Rock blocks on Ridge 2 after [58].

- The stone Monolith is located at 35m depth, some 200 m north of Ridge 1. It is described in the 2015 paper [59] as a ~12m long stone Monolith that broke into three stone blocks that are now arranged in a line (Figure 2C and Figure 5). Based on thin section petrography analysis of samples collected from the features, its lithology was classified as bioclastic sandstone, similar to Ridge 1 described above (SI Table S1). In three different places on this rock, there are holes, one which runs through the rock from side to side. The authors suggest that the rock represents a broken human-made megalith, associated with a Mesolithic culture that occupied the Pantelleria Vecchia Bank during low sea-level ~13,000 years BP, that was probably placed in a erect position. They therefore assume that people extracted the rock and transported it some 300m from Ridge 1 and then erected it. The following features were offered by them to support the anthropogenic origin of the Monolith: 1) It is made of the same rock and is the same age as Ridge 1; 2) there is no natural process that could create the three symmetrical holes of similar size (diameter) that are found in specific locations at the top and side of the Monolith; 3) the location of the rock and its isolated position would have made it stand out in the landscape.

- The half-ring features are sequence of blocks (up to 3m long and 0.5m thick) accumulations forming parallel, curved, ridges stretching a few hundred meters to the north of Ridges 1 and 2. Based on thin section petrographic analysis of samples collected from the half-ring features (see SI Table S1), their lithology was classified as bioclastic limestone dated to the Late Miocene (Tortonian) [59,60]. The rock type of the half-rings ridges is identical to the surrounding rocks forming the Pantelleria Vecchia Bank. Lodolo and colleagues excluded the possibility that the concentric half-rings were formed by natural processes and suggest that they were originally part of humanmade structures functioning either as, fortifications, anchorage, fishing installation, archeological trasses, or used for ritual practices [60].

3.2. The Lampedusa Site

- Archaeological setting:

- Geological setting:

- Past and present studies:

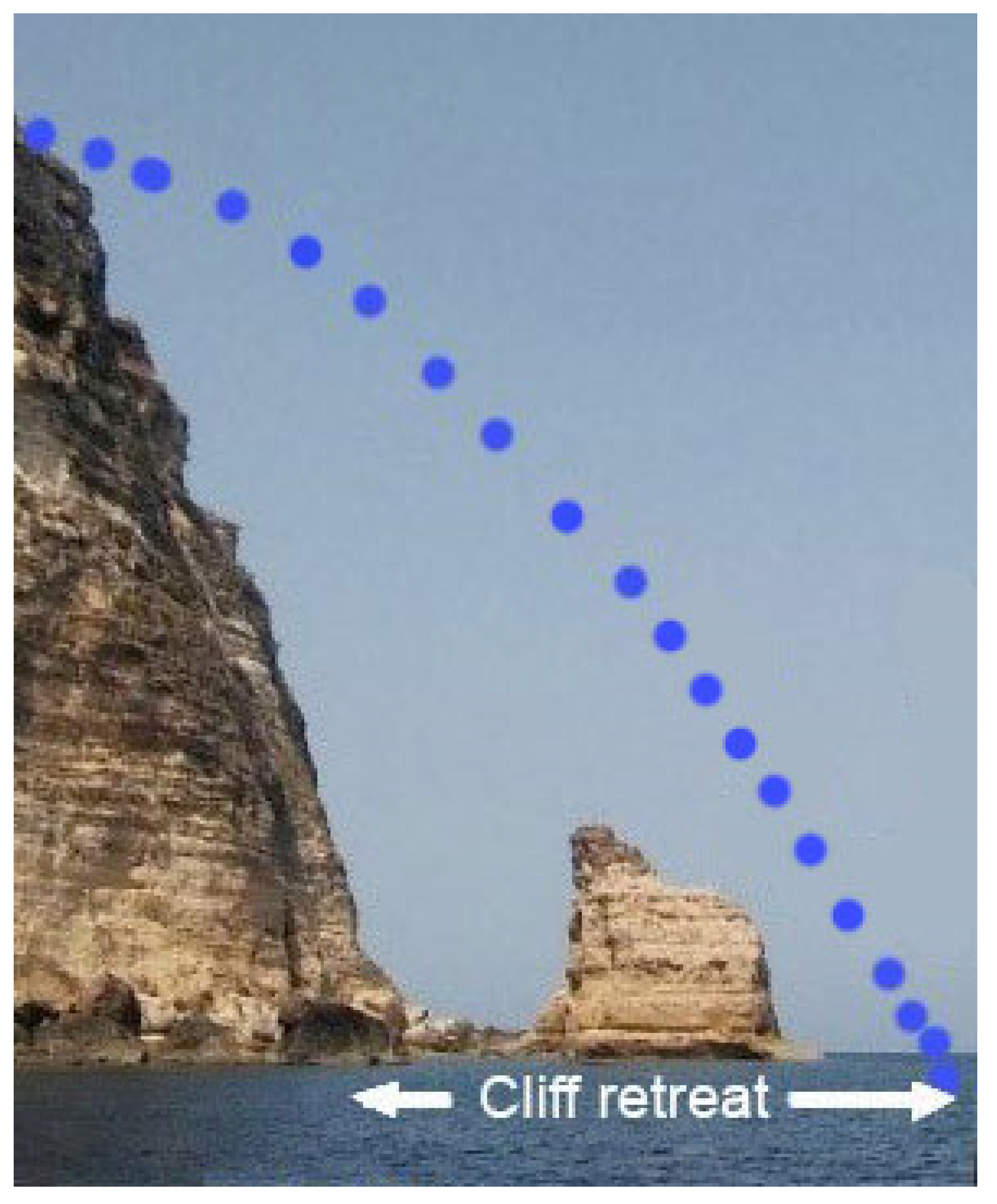

- Clusters of boulders of various sizes and shapes, which had collapsed from the coastal cliff. These are scattered in a random pattern on the shallow (1-12m deep) sea bottom, close to the foot of the coastal escarpment as usually can be found in colluvial deposits and landslides (Figure 7). Of the hundreds of boulders found there (Figure 9), some stone clusters may resemble human-made “stone arrangements”.

- Rock features protruding from the original in-situ rocky deposit on the sea bottom. These are the remains of rock deposits which were more resistant, thus underwent erosion and remained in their original location. Some of these are isolated, vertical protrusions (Figure 10 no. 4), while others are large (up to 50x30x3m) rock surfaces (Figure 10 no. 3). Galili and Ogloblin-Ramirez [67] summarized their research in an unpublished report, in which they noted that the boulders concentrations on the sea bottom are situated close to (10m or more) the foot of the coastal cliff, and that the numerous features identified on the sea bottom are typical products of a coastal escarpment under erosion (Figure 6).Figure 11. Suspected zoomorphic feature or erosional feature at the Lampedusa site (for location see Figure 10 no. 4) (E. Galili).Figure 11. Suspected zoomorphic feature or erosional feature at the Lampedusa site (for location see Figure 10 no. 4) (E. Galili).

4. Discussion

4.1. The Pantelleria Vecchia Bank Site

- Geomorphological considerations:

- Sea level and tectonic considerations:

- Holes and “chimney” features on intertidal, rocky environment:

- Dating considerations:

- Archaeological considerations:

- The absence of human-made finds in the suspected anthropogenic site:

4.2. The Lampedusa Site

- Possible parallel archaeological features on Lampedusa, Malta and Sicily:

- The MIS5e deposits and the archaeological sea-level markers used for testing tectonic stability and sea-level changes:

- Mid-Holocene sea-level indicators:

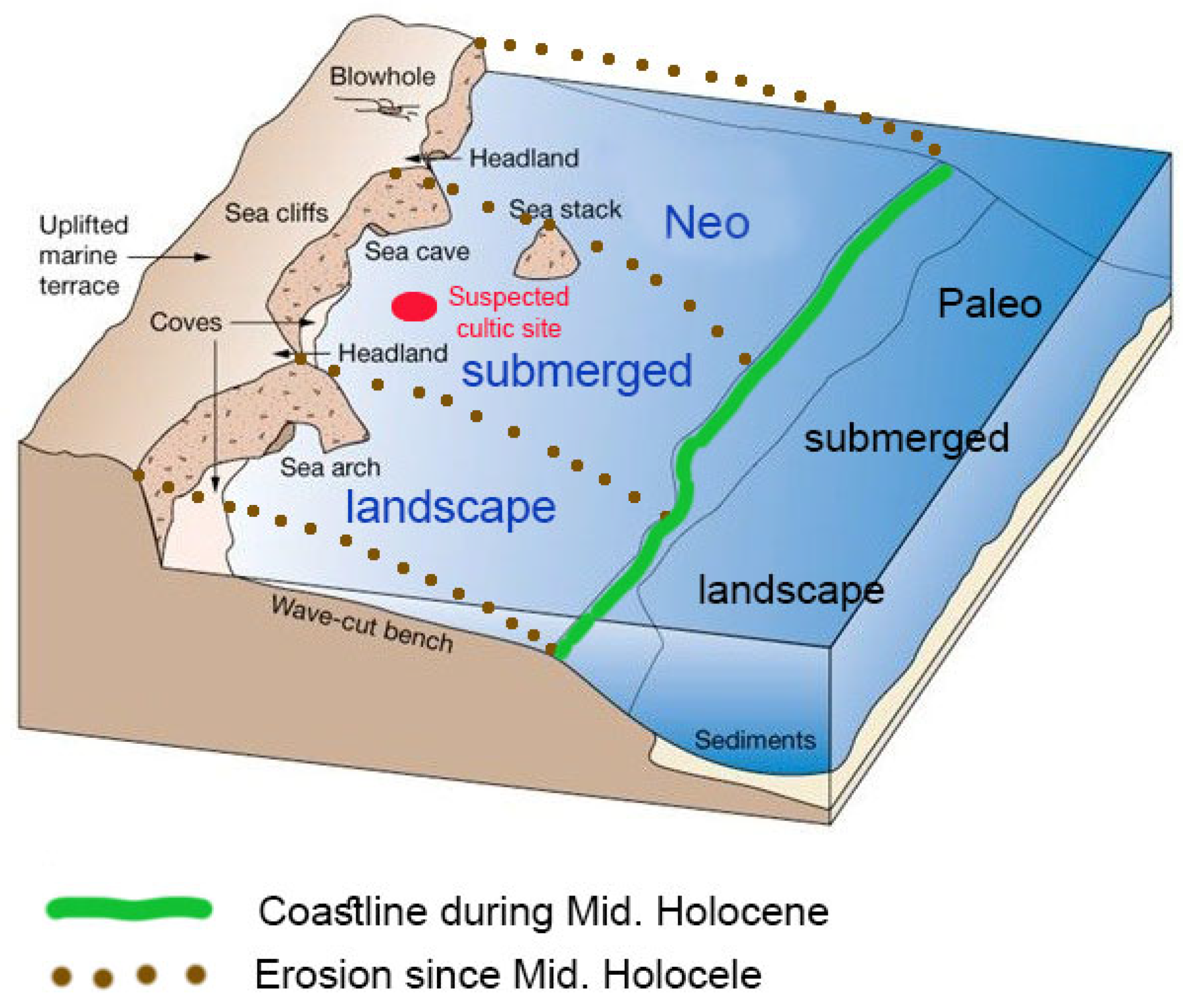

- Submerged paleo-landscape versus submerged neo-landscape:

5. Conclusions

5.2. The Submerged Features on the Pantelleria Vecchia Bank

5.2. The Suspected Megalithic Feature in North-Western Lampedusa

5.4. In Case of a Doubt, There Should Be No Doubt

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

References

- Lambeck, K.; Purcell, A. Sea-level change in the Mediterranean Sea since the LGM: model predictions for tectonically stable areas. Quaternary Science Reviews 2005, 24(18-19), 1969–1988.

- Lambeck, K.; Woodroffe, C.D.; Antonioli, F.; Anzidei, M.; Gehrels, W.R.; Laborel, J.; Wright, A.J. Paleoenvironmental records, geophysical modelling and reconstruction of sea level trends and variability on centennial and longer time scales. Understanding sea level rise and variability 2010, 61–121. [Google Scholar]

- Master, P.M.; Flemming, N.C. Quaternary Coastlines and Marine towards the Prehistory of Land Bridges and Continental Shelves; Academic Press: London, England, 1983; Passim. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, J.; Fischer, A.; Pickard, C.; Bonsall, C. Submerged Prehistory; Oxbow Book: Oxford, England, 2011; Passim. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, A.M.; Flatman, J.C.; Flemming, N.C. Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf: A Global Review; Springer: New York, USA, 2014; Passim. [Google Scholar]

- Harff, J.; Bailey, G. N.; Lüth, F. Geology and archaeology: submerged landscapes of the continental shelf: an introduction. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2016, 411 (1); 1–8.

- Blanc, A.C. Low levels of the Mediterranean Sea during the Pleistocene glaciation. Geological Society of London Quarterly Journal 1937, 93, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.C. Low levels of the Mediterranean. Sea during the Pleistocene glaciation. Quarterly. Journal of the Geological Society 1937, 93, 621–651. [Google Scholar]

- Galili, E.; Weinstein-Evron, M. Prehistory and paleoenvironments of submerged sites along the Carmel coast of Israel. Paléorient 1985, 11(1), 37–52.

- Bailey, G.N.; Flemming, N.C. Archaeology of the continental shelf: marine resources, submerged landscapes and underwater archaeology. Quaternary Science Reviews 2008, 27(23-24), 2153–2165.

- Flatman, J.C.; Evans, A.M. Prehistoric archaeology on the continental shelf: the state of the science. In Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf. A Global Review; Evans, A.M., Flatman, J.C., Flemming, N.C., Eds.; Springer: New York; USA, 2014, pp. 1–12.

- Flemming, N.C.; Harff, J.; Moura, D. Non-cultural processes of site formation, preservation and destruction. In Submerged Landscapes of the European Continental Shelf: Quaternary Paleoenvironments; Flemming, N.C., Harff, J., Moura, D., Burgess, A., Bailey, G.N., Eds.; Willey Blackwell, Hoboken NJ, USA, West Sussex, UK, 2017a; pp. 51-82.

- Flemming, N.C.; Harff, J.; Moura, D.; Burgess, A.; Bailey, G.N. Introduction: prehistoric remains on the continental shelf- Why do sites and landscapes survive inundation? In Submerged Landscapes of the European Continental Shelf Quaternary Paleoenvironments, Flemming, N.C., Harff, J., Moura, D., Burgess, A., Bailey, G.N. Eds.; Willey and Son: London, UK, 2017b pp. 1–10.

- Kimura, M. Ancient megalithic construction beneath the sea off Ryukyu islands in Japan, submerged by post glacial sea-level change. In Oceans' 04 MTS/IEEE Techno-Ocean'04 (IEEE Cat. No. 04CH37600), Vol. 2; Ed 1, a., Ed.; 2004; pp. 947–953.

- Hancock, G. Underworld: The Mysterious Origins of Civilization. Crown: Chichester, UK, 2009:596-625.

- Benjamin, J.; Hale, A. Marine, maritime, or submerged prehistory? Contextualizing the prehistoric underwater archaeologies of inland, coastal, and offshore environments. European Journal of Archaeology 2012, 15(2), 237–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, E. Prehistoric archaeology on the Continental Shelf: A global review. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 2017, 12(1), 147–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missiaent, T.; Sakellariou, D.; Flemming, N.C. Survey strategies and techniques in underwater geoarchaeology research: An overview with emphasis on prehistoric sites. In Under the Sea: Archaeology and Paleolandscapes of the Continental Shelf, Bailey, G.N., Harff, J., Sakellariou, D., Eds.; Springer: Switzerland, 2017; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Galili, E.; Horwitz, L.K.; Rosen, B. The “Israeli Model” for the detection, excavation and research of submerged prehistory. TINA-Maritime Archaeology Periodical 2019, 10, 31–69. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, K. O.; Edwards, R. L. Archaeological potential of the Atlantic continental shelf. American Antiquity 1966, 31(5Part1), 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, K.P. Note on the Late Post-Glacial Submergence of the Solent Margins. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 1943, 9, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steers, J.A., 1948. The coastline of England and Wales. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

- Flemming, N.C. Survival of submerged Lithic and Bronze Age artifact sites: A review of case histories. In Quaternary Coastlines and Marine Archaeology, Master, P.M., Flemming, N.C., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1983; pp. 135–73. [Google Scholar]

- Flemming, N.C. Preface. In Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf. A Global Review, Evans, A.M., Flatman, J.C., Flemming, N.C., Eds.; Springer, New York; 2014; pp. I–IV.

- Ronen, A.; Raban, A. Underwater State-Wide Survey. Bimtzulot Yam; Underwater Exploration Society of Israel?: Israel, 1965(3-4): 5 (in Hebrew).

- Raban, A. Submerged prehistoric sites on the Mediterranean coast of Israel. In Quaternary Coastlines and Marine Archaeology, Masters, P.M., Flemming N.C., Eds.; Cambridge: MA, 1983; pp. 215–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wreschner, E.E. Newe Yam–A submerged late-Neolithic settlement near Mount Carmel. Eretz-Israel 1977, 13, 260–271. [Google Scholar]

- Wreschner, E.E. The submerged Neolithic village Neve Yam on the Israeli Mediterranean coast. Quaternary coastlines and marine archaeology 1983, 325–333. [Google Scholar]

- Galili, E.; Weinstein-Evron, M.; Hershkovitz, I.; Gopher, A.; Kislev, M.; Lernau, O.; Lernaut, H. Atlit-Yam: a prehistoric site on the sea floor off the Israeli coast. Journal of Field Archaeology 1993, 20(2), 133–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili E.; Horwitz L.K. Submerged prehistory in Israel: A relatively new discipline. Strata Journal of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society. 2024. (in press).

- Faught, M.K.; Donoghue, J.F. Marine inundated archaeological sites and paleofluvial systems: Examples from a karst-controlled continental shelf setting in Apalachee Bay, northeastern Gulf of Mexico. Geoarchaeology 1997, 12, 417–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson C.E., Weinstein R.A., Sherwood M.G and Kelley D.B. 2014. Prehistoric Site Discover on the Outer Continental Shelf, Golf of Mexico, United States of America, In Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf. A Global Review; Evans, A.M., Flatman, J.C., Flemming, N.C., Eds.; Springer: New York; USA, 2014, pp. 53–72.

- Fisher, A. An entrance to the Mesolithic world below the ocean. Status of ten years’ work on the Danish Sea floor. In Man and Sea in the Mesolithic, Fisher, A. Ed.; Oxbow Press: London, UK,1995a; pp. 371– 384.

- Fischer, A. Man and the Sea in the Mesolithic: Coastal Settlement Above and Beyond Present Sea Level, Oxbow Monographs in Archaeology; Oxbow Books: Oxford, UK, 1995b: Passim.

- Fischer, A. Drowned forests from the Stone Age. In The Danish Storebaelt since the Ice Age: Man, Sea and Forest, Pedersen. L., Fischer, A., Aaby, B. Eds.; Danish National Museum: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1997: Passim.

- Gagliano, S.M.; Pearson, C.E.; Wiseman, D.E.; McClendo, C.M. Sedimentary studies of prehistoric archaeological sites: criteria for the identification of submerged archaeological sites of the north Gulf of Mexico, continental shelf. In Prepared for the U.S. Department of the Interior, vol. 3500379, National Park Service, Division of the State Plans and Grants, Contract, 1982.

- Murphy E.L. 8SL17: Natural Site-Formation Processes of a Multiple-Component Underwater Site in Florida. Submerged Cultural Resource, Special Report, 1990;29–36.

- Faught, M.K. Remote sensing, target identification and testing for submerged prehistoric sites in Florida: process and protocol in underwater CRM projects. In Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf: A Global Review, Evans, A.M., Flatman J.C., Flemming N.C. Eds.; Springer: New York, 2014; pp. 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson C.E., Weinstein R.A., Sherwood M.G and Kelley D.B. 2014. Prehistoric Site Discover on the Outer Continental Shelf, Golf of Mexico, United States of America, In Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf. A Global Review; Evans, A.M., Flatman, J.C., Flemming, N.C., Eds.; Springer: New York; USA, 2014, pp. 53–72.

- Skriver, C.; Borup, P.; Astrup, P.M. Hjarnø Sund: an eroding Mesolithic site and the tale of two paddles. In Under the Sea: Archaeology and Paleolandscapes of the Continental Shelf, Bailey, G.N., Harff, J., Sakellariou, D. Eds.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2017; pp. 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Galili, E.; Rosen, B.; Evron, M. W.; Hershkovitz, I.; Eshed, V.; Horwitz, L.K. Israel: Submerged prehistoric sites and settlements on the Mediterranean coastline—The current state of the art. In The Archaeology of Europe’s Drowned Landscapes, Bailey, G. Galanidou, N., Peeters, H., Jöhns, H., Mennenga, M. Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2020b; pp. 443–481.

- Bav´on, M.C.; Politis, G.G. The intertidal zone site of La Olla: early middle Holocene human adaptation on the Pampean coast of Argentina. In Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf. A Global Review, Evans, A.M., Flatman, J.C., Flemming, N.C. Eds.; Springer: New York, 2014; pp. 115–130. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, L.F.; Newman, W.S. Hominid migrations and the eustatic sea level paradigm: A critique. In Quaternary Coastlines and Marine towards the Prehistory of Land Bridges and Continental Shelves, Master, P.M., Flemming, N.C. Eds.; Academic Press: London, 1983; pp. 63–85. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, D. F.; Ballard, R.D. Oceanographic methods for underwater archaeological surveys. In Archaeological Oceanography, Ballard, R.D. Ed.; Princeton University Press: New Jersey, 2008; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Jöns, H.; Harff, J. Geoarchaeological research strategies in the Baltic Sea area: Environmental changes, shoreline-displacement and settlement strategies. In Prehistoric Archaeology on the Continental Shelf: A Global Review, Evans, A.M., Flatman, J.C., Flemming, N.C. Eds.; Springer: New York, 2014: 173–192.

- Benjamin, J.; O’Leary, M.; McDonald, J.; Wiseman, C.; McCarthy, J. Correction: Aboriginal artefacts on the continental shelf reveal ancient drowned cultural landscapes in northwest Australia. PLOS ONE 2023, 18(6), e02874902020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tizzard, L.; Bicket, A. R.; Benjamin, J.; Loecker, D.D. A Middle Palaeolithic site in the southern North Sea: investigating the archaeology and palaeogeography of Area 240. Journal of Quaternary Science 2014, 29(7), 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogloblin Ramirez, I.; Galili, E.; Shahack-Gross, R. Underwater Neolithic combustion features: A micro-geoarchaeological study in the submerged settlements off the Carmel Coast, Israel. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 2024, 19(3), 587–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, A. Stone Age on the Continental Shelf: an eroding resource. In Submerged Prehistory, Benjamin, J., Bonsall, C., Pickard, C., Fisher, A. Eds.; Oxbow Book: Oxford, 2011; pp. 298–310. [Google Scholar]

- Flemming, N.C. Research infrastructure for systematic study of prehistoric archaeology of the European submerged continental shelf. In Submerged Prehistory, Benjamin, J., Bonsall, C., Pickar, C., Fisher, A. Eds.; Oxbow Books: Oxford, 2011; pp. 287–297. [Google Scholar]

- Gusick, A.E.; Faught, M.K. Prehistoric archaeology underwater: A nascent subdiscipline critical to understanding early coastal occupations and migration routes. In Trekking the Shore: Changing Coastlines and Antiquity of Coastal Settlements, Bicho, N.F., Haws J.A., Davis, L.G. Eds.: Springer: New York, 2011; pp. 22–50.

- Orsi, P. 1991. Pantelleria. Risultati di una missione archeologica. Palermo: Cossira. (Reprinted from Orsi, P. 1899, Pantelleria. Monumenti Antichi dei Lincei IX, 449–540.

- Tusa, S. Archeologia e storia di un’isola nel Mediterraneo, In Pantellerian ware. Archeologia Subacquea e Ceramiche da Fuoco a Pantelleria, Santoro Bianchi, S., Guiducci, G., Tusa, S. Eds.; Palermo: Flaccovio Editore, 2003; pp. 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mantellini, S. The implications of water storage for human settlement in Mediterranean waterless islands: The example of Pantelleria. Environmental Archaeology 2015, 20(4), 406–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civile, D.; Lodolo, E.; Zecchin, M.; Ben-Avraham, Z.; Baradello, L.; Accettella, D.; Caffau, M. The lost adventure archipelago (Sicilian channel, mediterranean sea): morpho-bathymetry and late quaternary palaeogeographic evolution. Global and Planetary Change 2015, 125, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferranti, L.; Antonioli, F.; Mauz, B.; Amorosi, A.; Dai Pra, G.; Mastronuzzi, G.; Monaco, C.; Orrù, P.; Pappalardo, M.; Radtke, U.; Renda, P.; Romano, P.; Sansò, P.; Verrubbi, V.; Markers of the last interglacial sea level highstand along the coast of Italy: tectonic implications. Quaternary International 2006, 145–146, 30–54.

- Serpelloni, E.; Anzidei, M.; Baldi, P.; Casula, G.; Galvani, A. Crustal velocity and strain rate fields in Italy and surrounding regions: new results from the analysis of permanent and nonpermanent GPS networks. Geophysical Journal International 2005, 16, 861–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodolo, E.; Nannini, P.; Baradello, L.; Ben-Avraham, Z. Two enigmatic ridges in the Pantelleria Vecchia Bank (NW Sicilian Channel). Heliyon 2023, 9(3), e14575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodolo, E.; Ben-Avraham, Z. A submerged monolith in the Sicilian Channel (central Mediterranean Sea): Evidence for Mesolithic human activity. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 2015, 3, 398–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodolo, E.; Baradello, L.; Ben-Avraham, Z. Exploring the nature of the concentric half-rings in the Pantelleria Vecchia Bank (Sicilian Channel). Social Sciences & Humanities Open 2024, 9, 100892. [Google Scholar]

- Tusa, S. Il popolamento di Pantelleria e Lampedusa dalle prime frequentazioni neolitiche al villaggio di Mursia. Scienze dell'Antichità 2016, 22 (2), 363–385.

- Ratti, D. La Prehistoria di Lampedusa. Archivo Storico Lampedusa: 2015.

- Surico, G. Lampedusa: dall’agricoltura, alla pesca, al turismo. Firenze University Press: 2020.

- Ratti, D. Prehistoric village of Tabaccara coast. “Lampedusa: possible underwater prehistoric cult area.” Quaderni Dell’associazione Culturale Archive Storico Lampedusa 2014, 5: 1–23.

- Ratti, D. (2019). Lampedusa: possible underwater prehistoric place of worship. Diego Ratti - Academia.edu 19.4.2019. Associazione Culturale Archivio Storico Lampedusa - August 2016. https://www.academia.edu/27713754/Lampedusa_possible_underwater_prehistoric_place_of_worship 2/30.

- Grasso, M.A.R.I.O.; Pedley, H.M. The Pelagian Islands: A new geological interpretation from sedimentological and tectonic studies and its bearing on the evolution of the Central Mediterranean Sea (Pelagian Block). Geologica Romana 1985, 24(11), 13–34. [Google Scholar]

- Galili, E.; Ogloblin-Ramirez, I. Lampedusa surveys. 2019 (unpublished report).

- Ratti, D. 2022. Lampedusa Prehistorica. https://www.academia.edu/92709656/Lampedusa_preistorica?auto=download.

- Tusa, S.; Antonioli F.; Anzidei M. Il monolite sommerso a Pantelleria? E' una bufala.Ecco perchè. 2015; https://www.tp24.it/immagini_articoli/03-09-2015/1441286838-0-il-monolite-sommersoa-pantelleria-e--una-bufala-ecco-perche.jpg Gallery accessed 6/26/23, 7:51 PM.

- Siddall, M.; Rohling, E.J.; Thompson, W.G.; Waelbroeck, C. Marine isotope stage 3 sea level fluctuations: Data synthesis and new outlook. Reviews of Geophysics 2008, 46(4): RG4003.

- Waelbroeck, C.; Labeyrie, L.; Michel, E.; Duplessy, J.C.; Mcmanus, J.F.; Lambeck, K.; McManus J.F.; Balbon E.; Labracherie, M. Sea-level and deep-water temperature changes derived from benthic foraminifera isotopic records. Quaternary Science Reviews 2002, 21(1-3), 295–305.

- Lodolo, E.; Renzulli, A.; Cerrano, C.; Calcinai, B.; Civile, D.; Quarta, G.; Calcagnile, L. Unraveling past submarine Eruptions by dating lapilli tuff-encrusting coralligenous (Actea Volcano, NW sicilian channel). Frontiers in Earth Science 2021, 9, 664591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karkani, A.; Evelpidou, N.; Vacchi, M.; Morhange, C.; Tsukamoto, S.; Frechen, M.; Maroukian, H. Tracking shoreline evolution in central Cyclades (Greece) using beachrocks. Marine Geology 2017, 388, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deiana, G.; Lecca, L.; Melis, R.T.; Soldati, M.; Demurtas, V.; Orrù, P.E. Submarine geomorphology of the southwestern Sardinian continental shelf (Mediterranean Sea): Insights into the last glacial maximum sea-level changes and related environments. Water 2021, 13(2), 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddall, M.; Chappell, J.; Potter, E.K. Eustatic sea level during past interglacials. Developments in Quaternary Sciences 2007, 7, 75–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bar, A.; Bookman, R.; Galili, E.; Zviely, D. Beachrock morphology along the Mediterranean coast of Israel: Typological classification of erosion features. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2022, 10 (11),1571.78.

- Miller, W.R.; Mason, T.R. Erosional features of coastal beachrock and aeolianite outcrops in Natal and Zululand, South Africa. Journal of Coastal Research 1994, 10(2), 374–394. [Google Scholar]

- Shinn E.A. The mystique of beachrock. Int. Assoc. Sedimentol. Spec. Publ.2009, 41: 19–28.

- Abbott, A.T.; Pottratz, S.W. Marine pothole erosion, Oahu, Hawaii. Pac Sci 1969, 23(3), 276–290. [Google Scholar]

- Erginal, A.E.; Kiyak, N.G.; Ekinci, Y.L.; Demirci, A.; Ertek, T.A.; Canel, T. Age, Composition and paleoenvironmental significance of a Late Pleistocene eolianite from the western Black Sea coast of Turkey. Quaternary International 2013, 296, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambeck, K.; Antonioli, F.; Purcell, A.; Silenzi, S. Sea-level change along the Italian coast for the past 10,000 yr. Quaternary Science Reviews 2004, 23, 1567–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodolo, E.; Galassi, G.; Spada, G.; Zecchin, M.; Civile, D.; Bressoux, M. Post-LGM coastline evolution of the NW Sicilian Channel: Comparing high-resolution geophysical data with Glacial Isostatic Adjustment modeling. PLOS ONE 2020, 15(2), e0228087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bailey, G. N.; Harff, J.; Sakellariou, D. Under the sea: archaeology and palaeolandscapes of the continental shelf. Springer: Cham, Germany, 2017; Vol. 20; Passim.

- Abelli, L.; Agosto, M.V.; Casalbore, D.; Romagnoli, C.; Bosman, A.; Antonioli, F.; Chiocci, F.L. Marine geological and archaeological evidence of a possible pre-Neolithic site in Pantelleria Island, Central Mediterranean Sea. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 2016, 411(1), 97–110.

- Vella, C. Emerging aspects of interaction between prehistoric Sicily and Malta from the perspective of lithic tools. In Malta in the Hybleans, the Hybleans in Malta/Malta negli Iblei, gli Iblei a Malta, Bonanno A., Militello P. Eds.; Progetto KASA, Officina di Studi Medievali, Palermo. 2008: 81-93, 321-326.

- Evans, J.D. The Prehistoric Antiquities of the Maltese Islands: A Survey. The Athlone Press, University of London: London, UK, 1971; Passim.

- Trump, D.H. Skorba: Excavations carried out on behalf of the National Museum of Malta 1961–1963. Society of Antiquaries of London: London, UK, 1966: 1-102.

- Trump, D.H.; Cilia, D. Malta, Prehistory and Temples. Midsea Books Ltd, Malta. 2002.

- Bonanno, A. Insularity and isolation: Malta and Sicily in prehistory. In Malta in the Hybleans, the Hybleans in Malta/Malta negli Iblei, gli Iblei a Malta, Bonanno A., Militello P. Eds.; Progetto KASA, Officina di Studi Medievali, Palermo, 2008; 27–37.

- Procelli, E. Aspetti religiosi e apporti trasmarini nella cultura di Castelluccio. Journal of Mediterranean Studies 1991, 1.2, 252–266. [Google Scholar]

- Veca, C. Le tombe a camera dolmenica e la trasmissione di modelli funerari tra Malta e Sicilia durante il Bronzo. Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche 2020, LXX. S1, 531–537. [Google Scholar]

- Piccolo, S. Ancient Stones: The Dolmen Culture in Prehistoric South-Eastern Sicily. Brazen Head Publishing: Thornham, UK, 2013: 9-28.

- Antonioli, F.; Ferranti, L.; Fontana, A.; Amorosi, A.; Bondesan, A.; Braitenberg, C.; Stocchi, P. Holocene relative sea-level changes and vertical movements along the Italian and Istrian coastlines. Quaternary International 2009, 206(1-2), 102–133.

- Galili, E.; Zviely, D.; Ronen, A.; Mienis, H.K. Beach Deposits of MIS 5e high Sea Stand as Indicators for Tectonic Stability of the Carmel Coastal Plain, Israel. Quaternary Science Reviews 2007, 26, 2544–2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galili, E.; Sevketoglu, M.; Salamon, A.; Zviely, D.; Mienis, H.K.; Rosen, B.; Moshkovitz, S. Late Quaternary morphology, beach deposits, sea-level changes and uplift along the coast of Cyprus and its possible implications on the early colonists. In Geology and Archaeology:Submerged Landscapes of the Continental Shelf, Special Publications, Harff, J., Bailey, G., Lüth, F. Eds.; 2016, vol. 411.

- Galili, E.; Ronen, A.; Mienis, H.K.; Kolska Horwitz, L. Beach Deposits Containing Middle Paleolithic Archaeological Remains from Northern Israel. Quaternary International 2018, 464, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabrio, C.J.; Zazo, C.; Cabero, A.; Goy, J.L.; Bardají, T.; Hillaire-Marcel, C.; García-Blázquez, A.M. Millennial/submillennial-scale sea-level fluctuations in western Mediterranean during the second highstand of MIS 5e. Quaternary Science Reviews 2011, 30(3-4), 335–346.

- Mauz, B.; Vacchi, M.; Green, A.; Hoffmann, G.; Cooper, A. Beachrock: a tool for reconstructing relative sea level in the far-field. Marine Geology 2015, 362, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segre A.G. Geologia. Rendiconti Accademia Nazionale Dei XL, Serie IV, Vol. XI, 1960 pp. 115–162.

- Lambeck, K., Antonioli, F., Anzidei, M., Ferranti, L., Leoni, G., Scicchitano, G., & Silenzi, S. (2011). Sea level change along the Italian coast during the Holocene and projections for the future. Quaternary International, 232(1-2), 250-257: Figure 6.

- Galili, E.; Sharvit, J. Haifa, Tel Shiqmona–Underwater and Coastal Survey. Hadashot Arkheologiyot: Excavations and Surveys in Israel 2000, 112, 117. [Google Scholar]

- Galili E.; Sivan D. Introduction, Shikmona site-Physical conditions and ancient maritime activity. In Tel Shikmona. Gilboa, A. Ed.;(in press).

- Luo, E.C.R. Formation of beach profile with the design criteria of seawalls. Civil Engineering and Architecture 2014, 22(1), 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | The index fossil species Patella ferruginous and Arca noa were identified by the local geologist Giuseppe Sorrenti (personal communication). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).