Submitted:

07 October 2024

Posted:

08 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

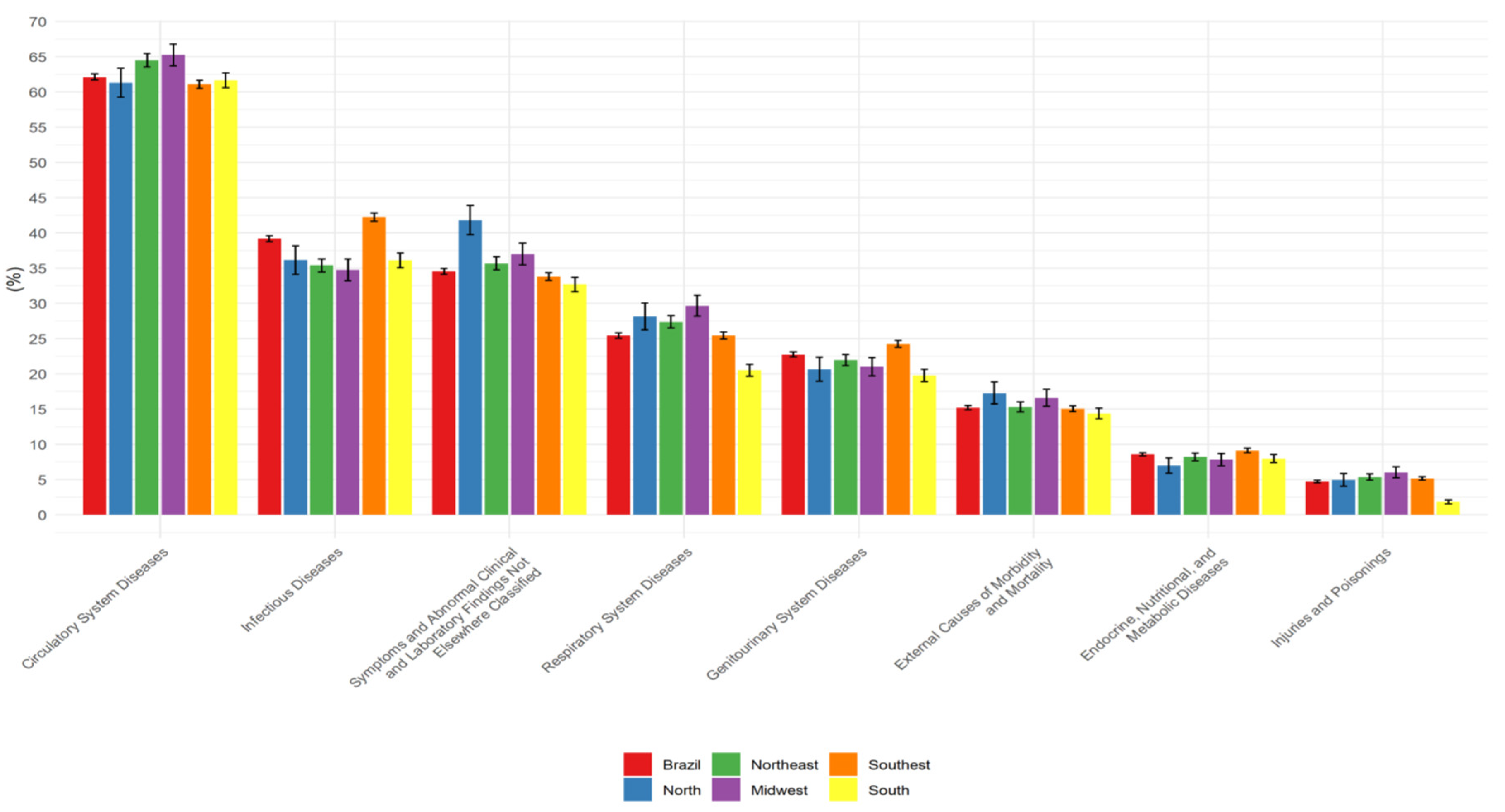

3.1. Analysis of the General Profile of Deaths Mentioning IE

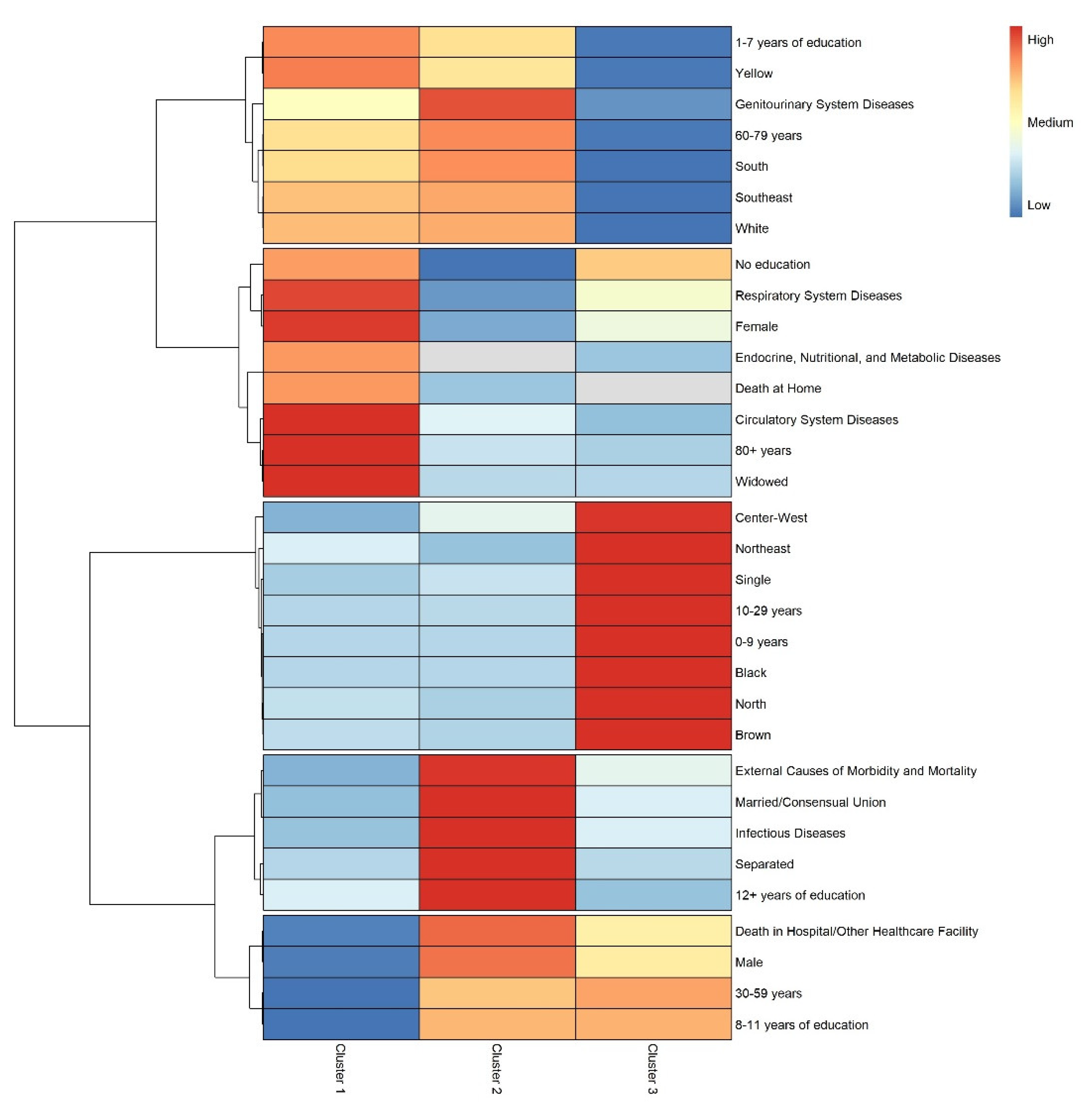

3.2. Analysis of Clusters with Mention of Deaths Due to IE

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Delgado, V.; Ajmone Marsan, N.; de Waha, S.; Bonaros, N.; Brida, M.; Burri, H.; Caselli, S.; Doenst, T.; Ederhy, S.; Erba, P. A.; Foldager, D.; Fosbøl, E. L.; Kovac, J.; Mestres, C. A.; Miller, O. I.; Miro, J. M.; Pazdernik, M.; Pizzi, M. N.; Quintana, E.; Rasmussen, T. B.; Ristić, A. D.; Rodés-Cabau, J.; Sionis, A.; Zühlke, L. J.; Borger, M. A.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Endocarditis: Developed by the Task Force on the Management of Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Endorsed by the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44 (39), 3948–4042. [CrossRef]

- Ambrosioni, J.; Hernandez-Meneses, M.; Téllez, A.; Pericàs, J.; Falces, C.; Tolosana, J. M.; Vidal, B.; Almela, M.; Quintana, E.; Llopis, J.; Moreno, A.; Miro, J. M.; Hospital Clinic Infective Endocarditis Investigators. The Changing Epidemiology of Infective Endocarditis in the Twenty-First Century. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2017, 19 (5), 21. [CrossRef]

- Bin Abdulhak, A. A.; Baddour, L. M.; Erwin, P. J.; Hoen, B.; Chu, V. H.; Mensah, G. A.; Tleyjeh, I. M. Global and Regional Burden of Infective Endocarditis, 1990–2010: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Glob. Heart 2014, 9 (1), 131–143. [CrossRef]

- Ferreiros, E.; Nacinovich, F.; Casabé, J. H.; Modenesi, J. C.; Swieszkowski, S.; Cortes, C.; Arazi, H. C.; Kazelian, L.; Varini, S. Epidemiologic, Clinical, and Microbiologic Profile of Infective Endocarditis in Argentina: A National Survey. The Endocarditis Infecciosa en la República Argentina–2 (EIRA-2) Study. Am. Heart J. 2006, 151 (2), 545–552. [CrossRef]

- Damasco, P. V.; Ramos, J. N.; Correal, J. C.; Potsch, M. V.; Vieira, V. V.; Camello, T. C.; Pereira, M. P.; Marques, V. D.; Santos, K. R.; Marques, E. A.; Castier, M. B.; Hirata, R. Jr.; Mattos-Guaraldi, A. L.; Fortes, C. Q. Infective Endocarditis in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: A 5-Year Experience at Two Teaching Hospitals. Infection 2014, 42 (5), 835–842. [CrossRef]

- Rajani, R.; Klein, J. L. Infective Endocarditis: A Contemporary Update. Clin. Med. (Lond.) 2020, 20(1), 31–35. [CrossRef]

- Cresti, A.; Baratta, P.; De Sensi, F.; Aloia, E.; Sposato, B.; Limbruno, U. Clinical Features and Mortality Rate of Infective Endocarditis in Intensive Care Unit: A Large-Scale Study and Literature Review. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2024, 28(1), 44–54.

- Damasco, P. V.; Correal, J. C. D.; Cruz-Campos, A. C. D.; Wajsbrot, B. R.; Cunha, R. G. da; Fonseca, A. G. da; et al. Epidemiological and Clinical Profile of Infective Endocarditis at a Brazilian Tertiary Care Center: An Eight-Year Prospective Study. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2019, 52, e2018375. [CrossRef]

- Jorge, M. S.; Rodrigues, A. J.; Vicente, W. V. A.; Evora, P. R. B. Cirurgia de Endocardite Infecciosa. Análise de 328 Pacientes Operados em um Hospital Universitário Terciário. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2023, 120(3), e20220608. [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, R. L.; Salgado, L. S.; Silva, Y. M. da; Figueiredo, G. G. R.; Bezerra Filho, R. M.; Machado, E. L. G.; et al. Epidemiological Profile of Patients with Infective Endocarditis at Three Tertiary Centers in Brazil from 2003 to 2017. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Sci. 2022, 35(4), 467–475. [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, R. de F.; Bastos, R. R.; Barcellos, C. Microdatasus: Pacote para Download e Pré-processamento de Microdados do Departamento de Informática do SUS (DATASUS). Cad. Saúde Pública 2019, 35(9), e00032419. [CrossRef]

- Wells, R. H. C.; Bay-Nielsen, H.; Braun, R.; Israel, R. A.; Laurenti, R.; Maguin, P.; Taylor, E. CID-10: Classificação Estatística Internacional de Doenças e Problemas Relacionados à Saúde; EDUSP: São Paulo, 2011.

- Lê, S.; Josse, J.; Husson, F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw. 2008, 25(1), 1–18. [CrossRef]

- Piron, M.; Lebart, L.; Morineau, A. Statistique Exploratoire Multidimensionnelle; DUNOD: Paris, France, 1995; 439 pp.

- Kolde, Raivo; Kolde, Maintainer Raivo. Package ‘pheatmap’. R package, v. 1, n. 7, p. 790, 2015. || pheatmap Package Documentation. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/pheatmap/index.html (accessed 01-10-2024).

- Avellana, P. M.; Aurelio, M. G.; Swieszkowski, S.; Nacinovich, F.; Kazelian, L.; Spennato, M.; Gagliardi, J. A. Infective Endocarditis in Argentina: Results of the EIRA 3 Study. Rev. Argent. Cardiol. 2018, 86(1), 19–27.

- Cresti, A.; Chiavarelli, M.; Scalese, M.; Nencioni, C.; Valentini, S.; Guerrini, F.; D’Aiello, I.; Picchi, A.; De Sensi, F.; Habib, G. Epidemiological and Mortality Trends in Infective Endocarditis: A 17-Year Population-Based Prospective Study. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2017, 7(1), 27–35.

- Oliveira, J. M.; Freitas, R. B.; Quirino, R. L.; Gomes, J. H.; Paula, B. P. Levantamento da Morbimortalidade por Endocardite de Valva no Brasil: Análise das Complicações da Doença e os Desafios do Diagnóstico e Terapêutica para a Melhora do Paciente. Braz. J. Health Rev. 2023, 6(6), 32590–32603.

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Censo Demográfico 2022: Resultados Gerais. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/ (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Diógenes, V. H. D.; Pinto Júnior, E. P.; Gonzaga, M. R.; Queiroz, B. L.; Lima, E. E. C.; Costa, L. C. C. da; et al. Differentials in Death Count Records by Databases in Brazil in 2010. Rev. Saúde Pública 2022, 56, 92. [CrossRef]

- David, L. E. S.; Cirilo, L. M.; Borges, P. V. B.; Souza, R. A. O.; Chalegre, M. C. T.; Silva, L. M. F.; Lima, L. C. S. Avaliação do Perfil Epidemiológico da Mortalidade por Endocardite Infecciosa no Brasil entre 2012 e 2021. In Anais do XXIII Congresso Brasileiro de Infectologia, Outubro de 2023; The Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2023; Vol. 27, Supplement 1, Paper e8828. [CrossRef]

- Melo, S. N. de; Torres, B. R. S.; Nascimento, M. M. G. do; Júnior, A. F. da S. X.; Rodrigues, W. G.; Lima, R. B. de S.; Souza, N. S. S. de; Menezes, L. E. de F. B. Caracterização do Perfil Epidemiológico da Mortalidade por Endocardite Infecciosa na Região Nordeste de 2010–2019. Rev. Eletrônica Acervo Saúde 2021, 13(9), e8828. [CrossRef]

- Ahtela, E.; Oksi, J.; Sipilä, J.; Rautava, P.; Kytö, V. Occurrence of Fatal Infective Endocarditis: A Population-Based Study in Finland. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19(1), 987. [CrossRef]

- Costa, M. A. C. da; Wollmann Jr, D. R.; Campos, A. C. L.; Cunha, C. L. P. da; Carvalho, R. G. de; Andrade, D. F. de; et al. Índice de Risco de Mortalidade por Endocardite Infecciosa: Um Modelo Logístico Multivariado. Braz. J. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007, 22(2), 192–200. [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Cruz, I.; Caldeira, D.; Alegria, S.; Gomes, A. C.; Broa, A. L.; et al. Risk Factors for In-Hospital Mortality in Infective Endocarditis. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2020, 114(1), 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, P.; Kestler, M.; De Alarcon, A.; Miro, J. M.; Bermejo, J.; Rodríguez-Abella, H.; Fariñas, M. C.; Cobo Belaustegui, M.; Mestres, C.; Llinares, P.; Goenaga, M.; Navas, E.; Oteo, J. A.; Tarabini, P.; Bouza, E.; Spanish Collaboration on Endocarditis-Grupo de Apoyo al Manejo de la Endocarditis Infecciosa en España (GAMES). Current Epidemiology and Outcome of Infective Endocarditis: A Multicenter, Prospective, Cohort Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015, 94(43), e1816. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, C.; Pinto, F. J. Endocardite Infecciosa: Ainda Mais Desafios que Certezas. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2022, 118(5), 976–988. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Brazil 52.0551 |

North 2.1681 |

Northeast 9.9221 |

Midwest 3.6451 |

Southeast 28.1141 |

South 8.2061 |

p-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | <0,001 | ||||||

| 0 to 9 | 1.492 (2.9%) | 150 (6.9%) | 355 (3.6%) | 95 (2.6%) | 756 (2.7%) | 136 (1.7%) | |

| 10 to 29 | 4.210 (8.1%) | 400 (18.5%) | 1.509 (15.2%) | 316 (8.7%) | 1.596 (5.7%) | 389 (4.7%) | |

| 30 to 59 | 19.003 (36.5%) | 897 (41.4%) | 3.887 (39.2%) | 1.528 (41.9%) | 9.939 (35.4%) | 2.752 (33.5%) | |

| 60 to 79 | 20.135 (38.7%) | 580 (26.8%) | 2.997 (30.2%) | 1.322 (36.3%) | 11.531 (41.0%) | 3.705 (45.1%) | |

| 80 or more | 7.215 (13.9%) | 141 (6.5%) | 1.174 (11.8%) | 384 (10.5%) | 4.292 (15.3%) | 1.224 (14.9%) | |

| Gender | <0,001 | ||||||

| Female | 23.593 (45.3%) | 937 (43.2%) | 4.644 (46.8%) | 1.637 (44.9%) | 12.896 (45.9%) | 3.479 (42.4%) | |

| Male | 28.462 (54.7%) | 1.231 (56.8%) | 5.278 (53.2%) | 2.008 (55.1%) | 15.218 (54.1%) | 4.727 (57.6%) | |

| Race/Color | <0,001 | ||||||

| Yellow | 336 (0.7%) | 7 (0.3%) | 22 (0.2%) | 17 (0.5%) | 263 (1.0%) | 27 (0.3%) | |

| White | 30.908 (63.6%) | 604 (29.0%) | 2.963 (33.0%) | 1.761 (50.7%) | 18.491 (70.4%) | 7.089 (91.2%) | |

| Indigenous | 83 (0.2%) | 27 (1.3%) | 9 (0.1%) | 22 (0.6%) | 15 (0.1%) | 10 (0.1%) | |

| Brown | 13.702 (28.2%) | 1.307 (62.7%) | 5.179 (57.7%) | 1.443 (41.5%) | 5.419 (20.6%) | 354 (4.6%) | |

| Black | 3.546 (7.3%) | 138 (6.6%) | 804 (9.0%) | 232 (6.7%) | 2.083 (7.9%) | 289 (3.7%) | |

| Unknown | 3.480 | 85 | 945 | 170 | 1.843 | 437 | |

| Marital Status | <0,001 | ||||||

| Single | 12.534 (26.2%) | 761 (39.9%) | 3.260 (38.0%) | 948 (28.8%) | 6.162 (23.4%) | 1.403 (18.1%) | |

| Married/Consensual union | 23.873 (49.9%) | 876 (45.9%) | 3.920 (45.7%) | 1.613 (49.1%) | 13.153 (49.9%) | 4.311 (55.5%) | |

| Legally separated | 3.121 (6.5%) | 78 (4.1%) | 296 (3.5%) | 243 (7.4%) | 1.992 (7.6%) | 512 (6.6%) | |

| Widowed | 8.338 (17.4%) | 192 (10.1%) | 1.097 (12.8%) | 483 (14.7%) | 5.028 (19.1%) | 1.538 (19.8%) | |

| Unknown | 4.189 | 261 | 1.349 | 358 | 1.779 | 442 | |

| Education Level | <0,001 | ||||||

| None | 3.750 (10.4%) | 228 (13.7%) | 1.126 (17.6%) | 368 (13.6%) | 1.561 (8.1%) | 467 (8.0%) | |

| 1 to 7 years | 20.353 (56.7%) | 864 (51.8%) | 3.388 (53.0%) | 1.496 (55.1%) | 10.888 (56.5%) | 3.717 (63.6%) | |

| 8 to 11 years | 7.746 (21.6%) | 418 (25.1%) | 1.290 (20.2%) | 587 (21.6%) | 4.320 (22.4%) | 1.131 (19.4%) | |

| 12 years or more | 4.037 (11.2%) | 158 (9.5%) | 583 (9.1%) | 263 (9.7%) | 2.505 (13.0%) | 528 (9.0%) | |

| Unknown | 16.169 | 500 | 3.535 | 931 | 8.840 | 2.363 | |

| Place of Death | <0,001 | ||||||

| Home | 3.027 (5.8%) | 94 (4.3%) | 735 (7.4%) | 273 (7.5%) | 1.310 (4.7%) | 615 (7.5%) | |

| Hospital/Other healthcare facility | 48.378 (93.0%) | 2.047 (94.6%) | 9.014 (91.0%) | 3.316 (91.0%) | 26.554 (94.5%) | 7.447 (90.9%) | |

| Others | 604 (1.2%) | 23 (1.1%) | 152 (1.5%) | 53 (1.5%) | 241 (0.9%) | 135 (1.6%) | |

| Unknown | 46 | 4 | 21 | 3 | 9 | 9 | |

| 1n (%); 2Chi-squared test of independence | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).