1. Introduction

Detection of mismatch repair deficiency (MMRd) is of critical importance to the care of people with cancer and their families as it is a primary determinant of the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade therapy [

1,

2] and helps to identify individuals with Lynch syndrome (LS) who can benefit, along with affected family members, from enhanced surveillance and chemoprevention [

3,

4].

LS, the most common inherited cancer syndrome, predisposes to a range of tumours, with colorectal cancer (CRC) and endometrial cancer (EC) being the most common [

5,

6]. It is caused by heterozygous pathogenic variants affecting one of four genes central to the mismatch repair (MMR) pathway;

MLH1,

MSH2,

MSH6 and

PMS2. Somatic loss of the second allele leads to failure of DNA repair and accumulation of potentially tumorigenic variants. Repetitive sequences are especially prone to error induced by replication slippage, resulting in the associated molecular phenotype of microsatellite instability (MSI) [

7,

8]. Tumour spectrum and penetrance varies extensively by gene affected [

9], leading to the suggestion that LS be considered four separate clinical entities [

10].

Almost all CRCs and ECs are routinely screened in England to identify LS cases, primarily using immunohistochemistry (IHC) or MSI analysis [

11]. The former involves analysis of expression of all four MMR proteins in tumour sections [

12]. The latter most commonly involves fragment length analysis of highly informative PCR amplified microsatellite markers (FLA-PCR [

13,

14]) using, for example, the Promega MSI Analysis System V1.2 (Promega MSI, [

15]). Melt curve analysis of MSI marker amplicons [

16], or analysis of markers within high throughput/panel sequencing data [

17,

18] are also now used.

These methods vary in terms of cost, throughput, and ease of use and result interpretation [

11,

12,

13]. For instance, IHC is readily integrated with hospital pathology services, can often identify the gene affected, and is robust to heterogeneity in tumour cell content, but it requires expert interpretation and can miss up to 6% of pathogenic variants which do not affect antibody binding [

19]. As a result, there is no single gold standard method for MMRd detection, and tumour specific guidelines for LS screening have been developed in the UK based on health economic evaluation [

20,

21], with IHC or FLA-PCR based MSI methods recommended for CRCs (

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg27), and IHC specifically recommended for ECs (

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg42). Similarly, US and European medical professional organisations recommend the use of IHC over MSI to determine MMR status in EC patients being considered for immunotherapy [

22,

23].

One factor contributing to tumour specific guidelines is that while IHC and MSI give highly concordant results in CRCs [

24,

25], test concordance in ECs is much more variable [

11,

26]. Some variability can be attributed to use of dinucleotide repeat markers in early MSI assays which do not efficiently identify

MSH6 deficiency, common in EC [

27,

28,

29]. Levels of MSI are also generally lower in EC relative to CRC [

30,

31], suggesting that current MSI assays lack sensitivity or need to be optimised for use in this tumour type [

18].

We have recently developed an amplicon sequencing based MSI method [

32,

33] which has been adopted as the primary assay of MMRd in CRC in our NHS region – the Newcastle MSI assay (NCL_MSI). Here we use this assay to analyse previously well characterised clinical trial cohorts with distinct concordance levels between IHC and MSI [

34,

35,

36], and assess the impact both of using a larger and more sensitive MSI marker panel [

32] and classification criteria specific for ECs. We also analyse the MSI signal within sporadic and LS tumours with respect to MMR protein loss and MMR gene affected.

4. Discussion

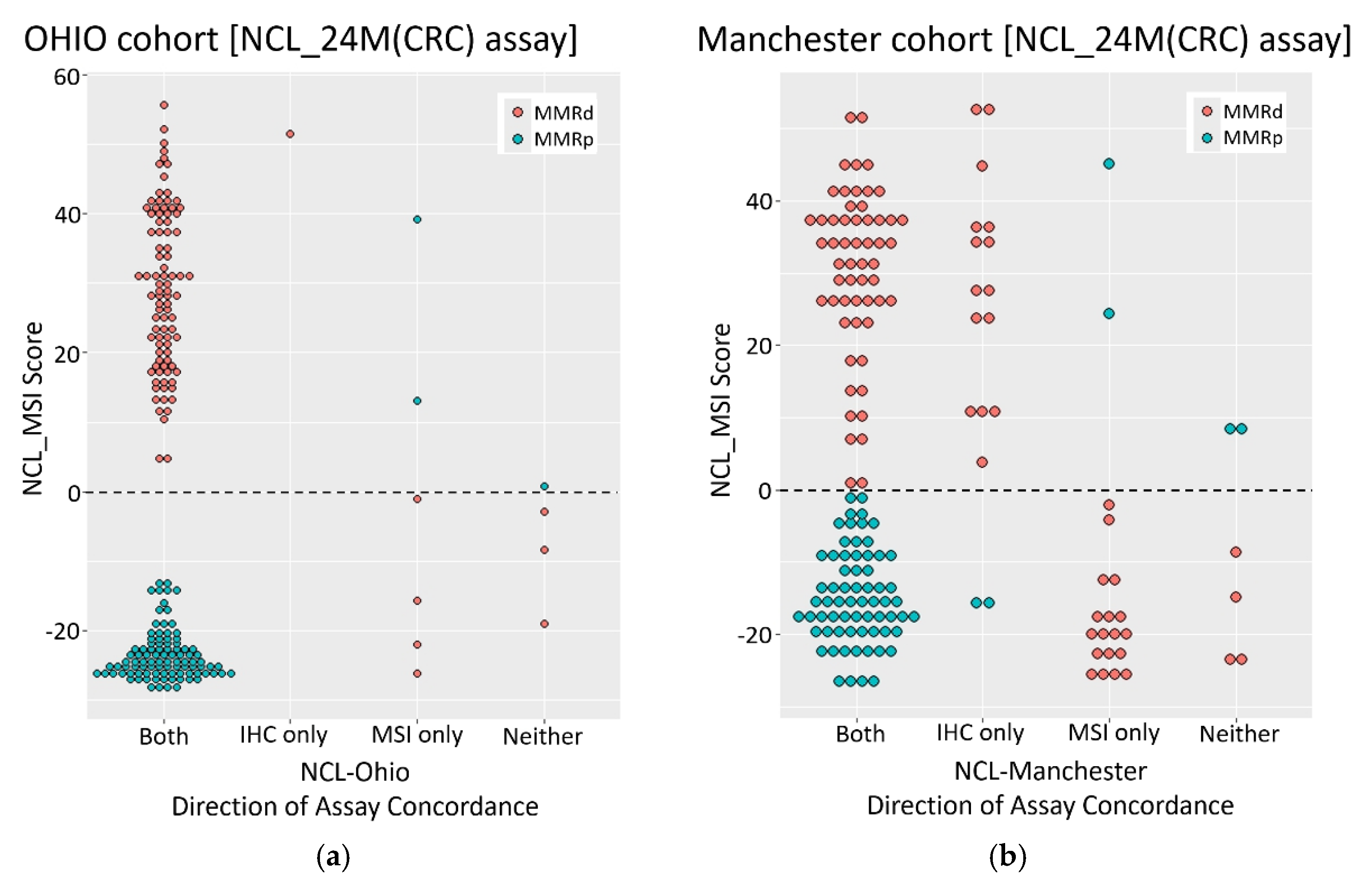

We assessed the performance of the amplicon sequencing based NCL_MSI assay for use in ECs by re-analysing well characterised tumour cohorts from prospective clinical trials, and investigated the basis of previously reported discordance between IHC and MSI results. The NCL_MSI results were very consistent with the Ohio studies; concordance between NCL_MSI, IHC, and the original MSI results being >94%, comparable to the concordance between IHC and MSI in CRCs [

12,

19,

24,

43]. In the Manchester cohort, the NCL_MSI assay improved MSI sensitivity with respect to IHC by over 10% compared to the Promega MSI assay.

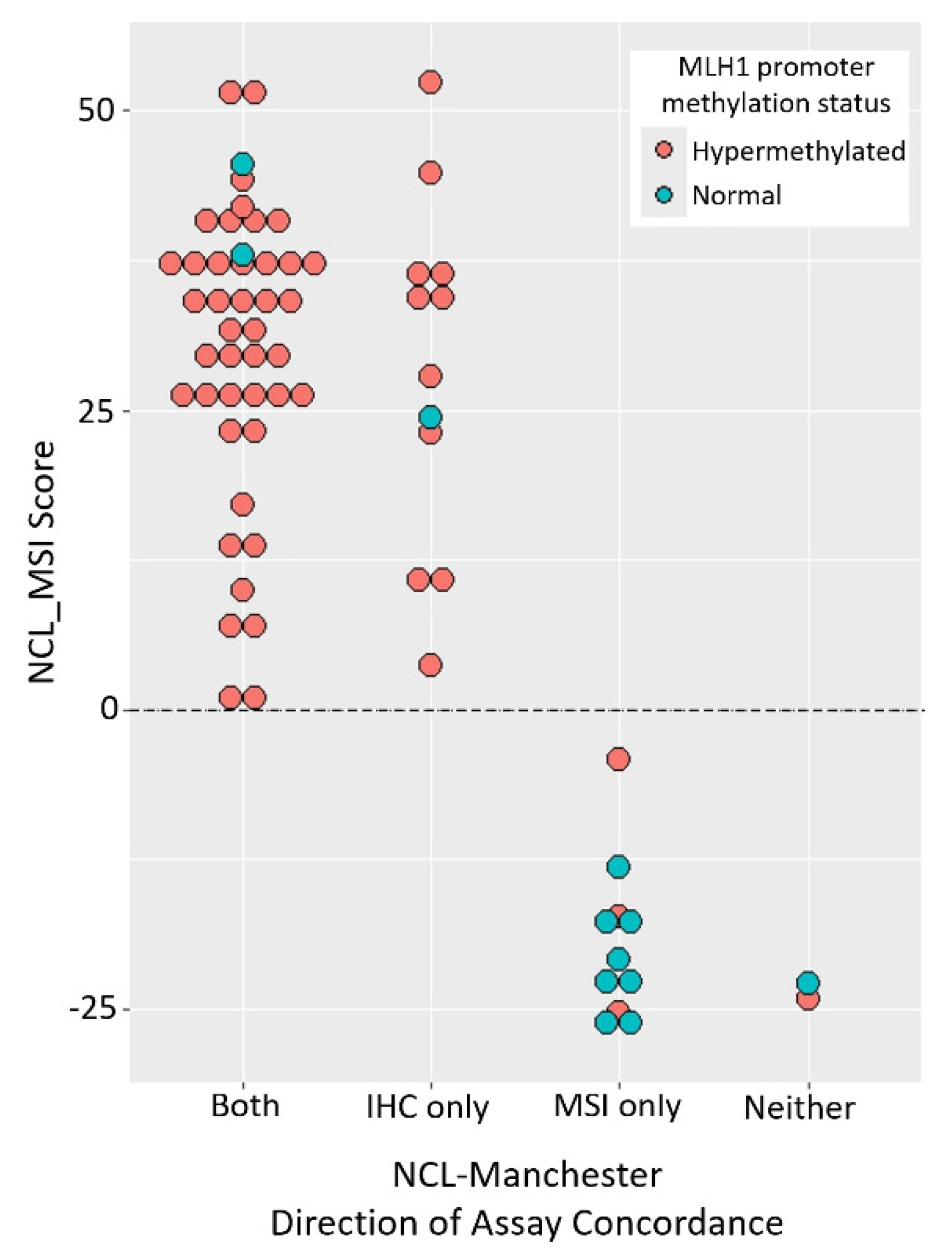

MLH1 promoter methylation data enabled two main groups of discordant samples to be identified (

Figure 2): one suggesting Promega MSI false negatives (11 with MLH1 loss, hypermethylation, MSI-H by NCL_MSI but MSS by Promega MSI), the other IHC false positives (eight with MLH1 loss, normal methylation, and MSS by both MSI assays). This suggests that in the original Manchester analysis, up to 16% of tumours with MLH1 protein loss were Promega MSI false negatives, and up to 12% with loss of MLH1 were IHC false positives.

These results establish that the NCL_MSI assay can be more sensitive than Promega MSI in some EC cohorts. One potential confounding factor is that Ohio samples analysed were the same DNA aliquots used in the trials, whereas the Manchester samples were DNAs extracted from independent tissue curls taken from the original FFPE blocks analysed. This resulted in sample drop out and may have contributed to the higher discordance of the NCL_MSI assay with these samples. However, it cannot account for the significant skew with respect to IHC/Promega MSI classification, or significant association of NCL_MSI-H calls with MLH1 promoter methylation status among discordant samples.

The results do not establish why assay concordance was significantly different between the original Ohio and Manchester analyses. All three trials (OCCPI, OPTEC, PETALS) had very similar enrolment and study protocols, but there are two potentially important differences.

First, although IHC methodology was comparable between studies, how tumours were dichotomised as MMRd or MMRp differed. Ohio samples were classified using College of American Pathologist (CAP) guidelines [

44], where samples with equivocal or weak IHC staining (cut off defined as >1% positive nuclei) are classified as mismatch repair proficient (MMRp). In the Manchester cohort, classification of such samples was based on consensus guidelines [

37], staining was repeated if results were inconclusive, and final classification was agreed by a team of expert pathologists. As a result, some samples with patchy IHC staining were classified as MMRd, others as MMRp (Table s003 [

36]), with all being referred on for germline MMR gene testing.

The potential impact of this difference can be understood by considering how IHC was conceptually embedded within the care pathways. In Ohio, it was complementary to MSI testing, with the expectation that any MMRd tumours missed as a result of the stringent IHC classification would be picked up by MSI testing [

43]. Within Manchester, IHC was deployed as a stand alone assay to identify all potential LS cases, with anomalous results leading to referral for germline testing irrespective of MSI status [

37]. In such a pipeline, a small number of IHC MMRd false positives can be tolerated, even considered desirable, as they are of minor consequence relative to a missed LS diagnosis and would be excluded in subsequent steps of the LS diagnostic pathway.

In this context it is noteworthy that regions of tumours with patchy or subclonal MMR protein loss are known to have elevated frequencies of MSI [

45] or somatic MMR gene mutations [

46,

47], and subclonal or weak MMR protein staining has recently been shown to account for much of the discordance between IHC and MSI assays [

48,

49]. This has led to the revision of US CAP recommendations to ensure that anomalous staining patterns are reported and interpreted consistently [

48].

Second, review of Pathology reports established that some Manchester samples had low TCC, with a quarter having 20% or below and requiring enrichment prior to MSI analysis. Several were 5% or lower. Given that the limit of detection of Promega MSI is 10% tumour cells for CRC material [

15], compared to ~3% for NCL_MSI [

33], the significant association between low TCC and Promega MSS calls in the Manchester data strongly suggest that this contributed to Promega false negatives, and highlights the importance of selecting material with high TCC for molecular testing in ECs.

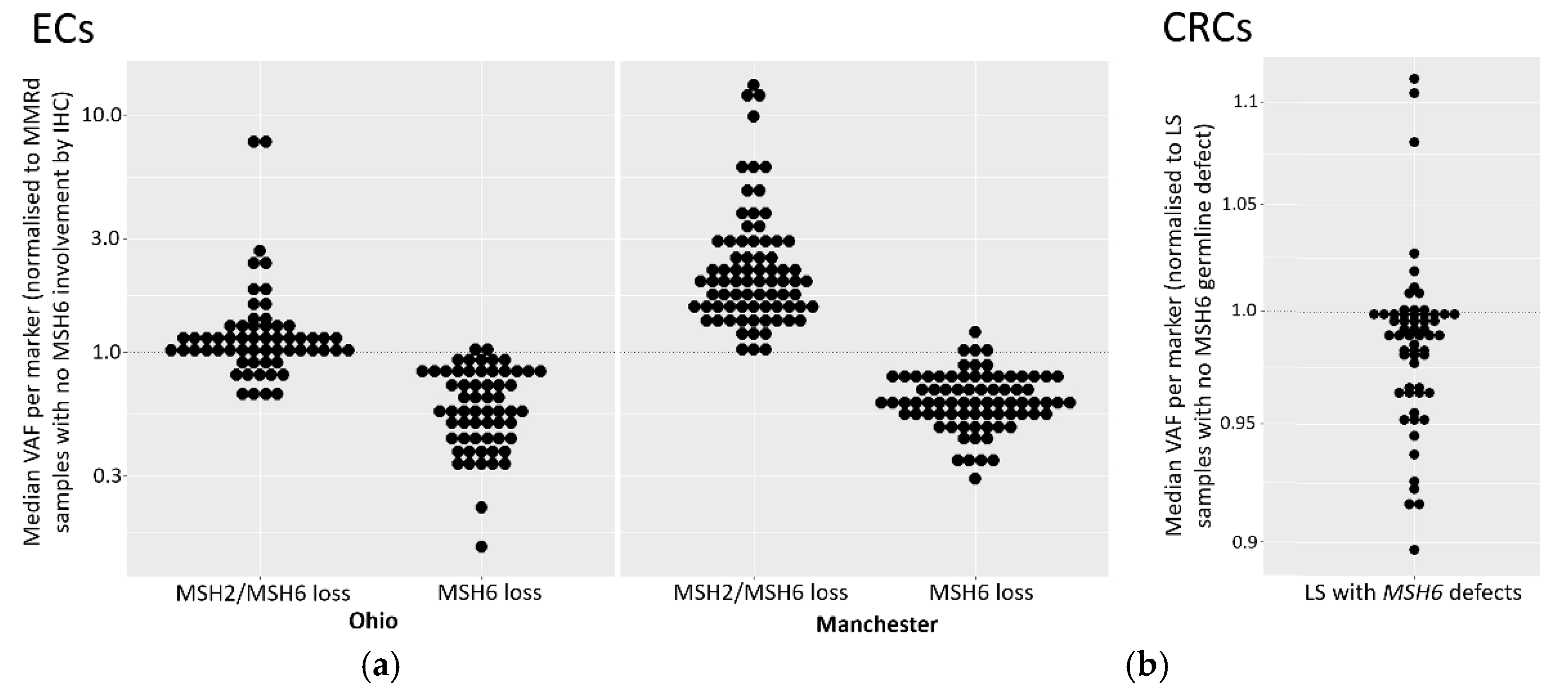

Despite the increased sensitivity of the NCL_MSI assay in the Manchester cohort, it could not reliably identify tumours with inherited pathogenic MMR mutations, particularly cases with isolated MSH6 loss by IHC, classifying six out of 11 as MSS (

Table 3). While low TCC could be a contributing factor with specific samples (PET31 in particular), three of the Manchester LS MSH6 samples classified as MSS by NCL_MSI had TCCs of 50% or above (

Table S7). These results therefore support current guidelines recommending IHC as the primary assay for LS detection, and assessment for immunotherapy treatment in EC patients (

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/dg42, [

22,

23]).

However, IHC interpretation is subjective, can give equivocal results requiring repeat analysis, and relies on the expertise of the pathologist. Furthermore, MSI analysis can identify MMR mutations which do not affect antibody binding [

50]. The assays are therefore complimentary, and use of both is desirable [

43], and may be of particular importance in ECs given the variation in concordance observed here and elsewhere (reviewed in [

26]). We have recently developed a direct to sequencing multiplex PCR format of the NCL_MSI assay [

51] to facilitate routine and high throughput use. In addition, a further Promega MSI assay using longer microsatellite markers has been developed (LMR MSI) which also shows increased sensitivity for EC MMRd detection compared to the V1.2 assay [

52].

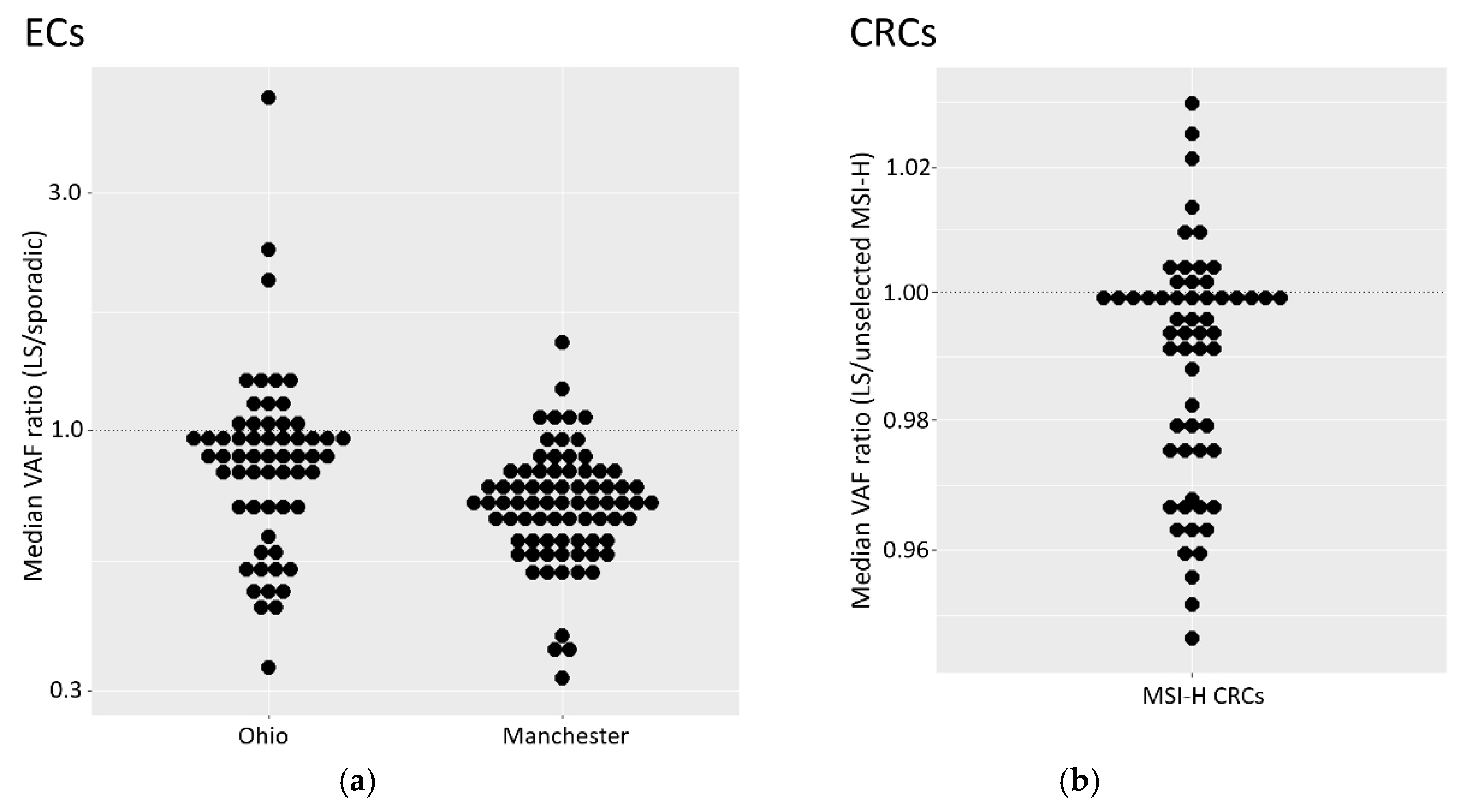

The reduction of MSI signal we observe in ECs with isolated MSH6 loss adds to a growing body of evidence that detection of such tumours is particularly challenging using MSI. That there is also a reduced signal in LS tumours suggests that MSI-based detection of MMRd in ECs from LS patients with MSH6 lesions is particularly difficult. Because of the relatively low number of LS and MSH6 tumours in both EC cohorts, we also analysed CRC cohorts, and identified small, but significant, reductions in VAFs in both MSH6 and LS tumours.

An attenuated MSH6 MSI signal was first reported in CRC over 20 years ago [

53] and is assumed to be due to functional redundancy between MSH6 and MSH3 [

54,

55]. The inclusion in early MSI panels of dinucleotide repeats, which MSH6 plays no role in repairing, may have accentuated this difference, but it has now been reported using a variety of MSI assays (including those using only mononucleotide repeats) and in a variety of disease contexts [

16,

32,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. This is particularly noticeable in EC due to lower levels of MSI relative to CRC [

30,

31].

The evidence for a weaker MSI signal in LS derived tumours is less well documented. An early comparison of inherited and sporadic CRC [

61] reported a reduction in the number of unstable markers in the former (72% vs 87%), but as six out of the 10 MSI markers used were dinucleotide repeats, this may have been related to higher rates of MSH6 deficiency among the inherited CRCs. Why LS tumours may have a reduced MSI signal is unknown, but could relate to differing tumorigenesis pathways and selection pressures. For example, MMRd tumours are highly immunogenic due to mutations in coding microsatellites leading to novel frameshift peptides [

62,

63], and increased T cell counts have been reported in the stroma, tumour, or invasive margins of MMRd/MSI-H LS derived CRCs [

64,

65], adenomas [

66], and ECs [

67,

68], relative to sporadic tumours. Furthermore, the normal colonic mucosa of MMR mutation carriers develop numerous MMRd crypt foci not present in the general population [

69] which could lead to immune surveillance, and LS cancers are often diagnosed before the 6th decade of life, the age at which the immune system begins to noticeably weaken [

70]. Both could increase selection against increased frameshift peptide burden caused by high levels of MSI and result in the observed lower MSI marker VAFs within LS tumours.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, John Burn, Mauro Santibanez-Koref and Michael Jackson; Data curation, Richard Gallon, Mauro Santibanez-Koref and Michael Jackson; Formal analysis, Peter Sowter, Richard Gallon, Mauro Santibanez-Koref and Michael Jackson; Funding acquisition, Emma Crosbie and John Burn; Investigation, Peter Sowter, Christine Hayes, Rachel Phelps, Shaun Prior, Jenny Combe and Neil Ryan; Project administration, Gillian Borthwick; Resources, Rachel Pearlman, Heather Hampel, Paul Goodfellow, D Evans, Emma Crosbie and Neil Ryan; Supervision, John Burn, Mauro Santibanez-Koref and Michael Jackson; Visualization, Peter Sowter and Mauro Santibanez-Koref; Writing – original draft, Richard Gallon, John Burn, Mauro Santibanez-Koref and Michael Jackson; Writing – review & editing, Peter Sowter, Richard Gallon, Holly Buist, Heather Hampel, Emma Crosbie, John Burn, Mauro Santibanez-Koref and Michael Jackson.