Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

08 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Literature Review and Hypothesis

Task Approach and RBTC

Technological Change and Non-Standard Employment

The Principal-Agent Model, Routine Tasks, and Research Design

Data and Methods

Data

Methods

Results and Robustness Check

Regression Results

Conclusions, Implications and Future Directions

Conclusions

Implications

Future Directions

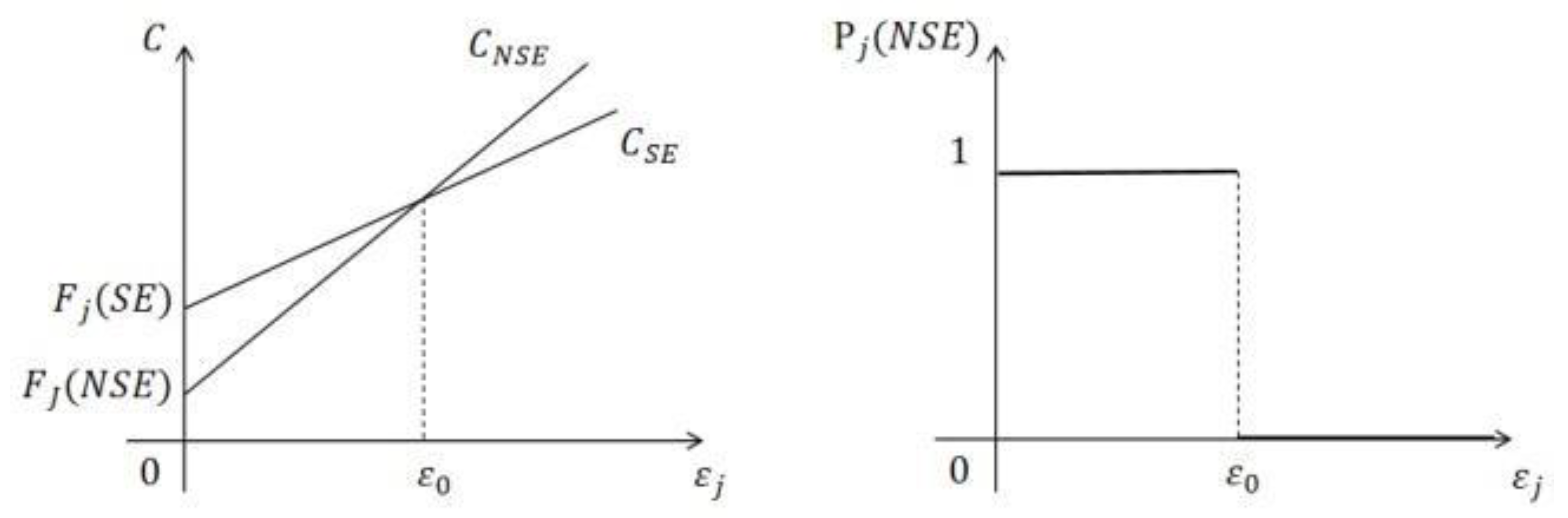

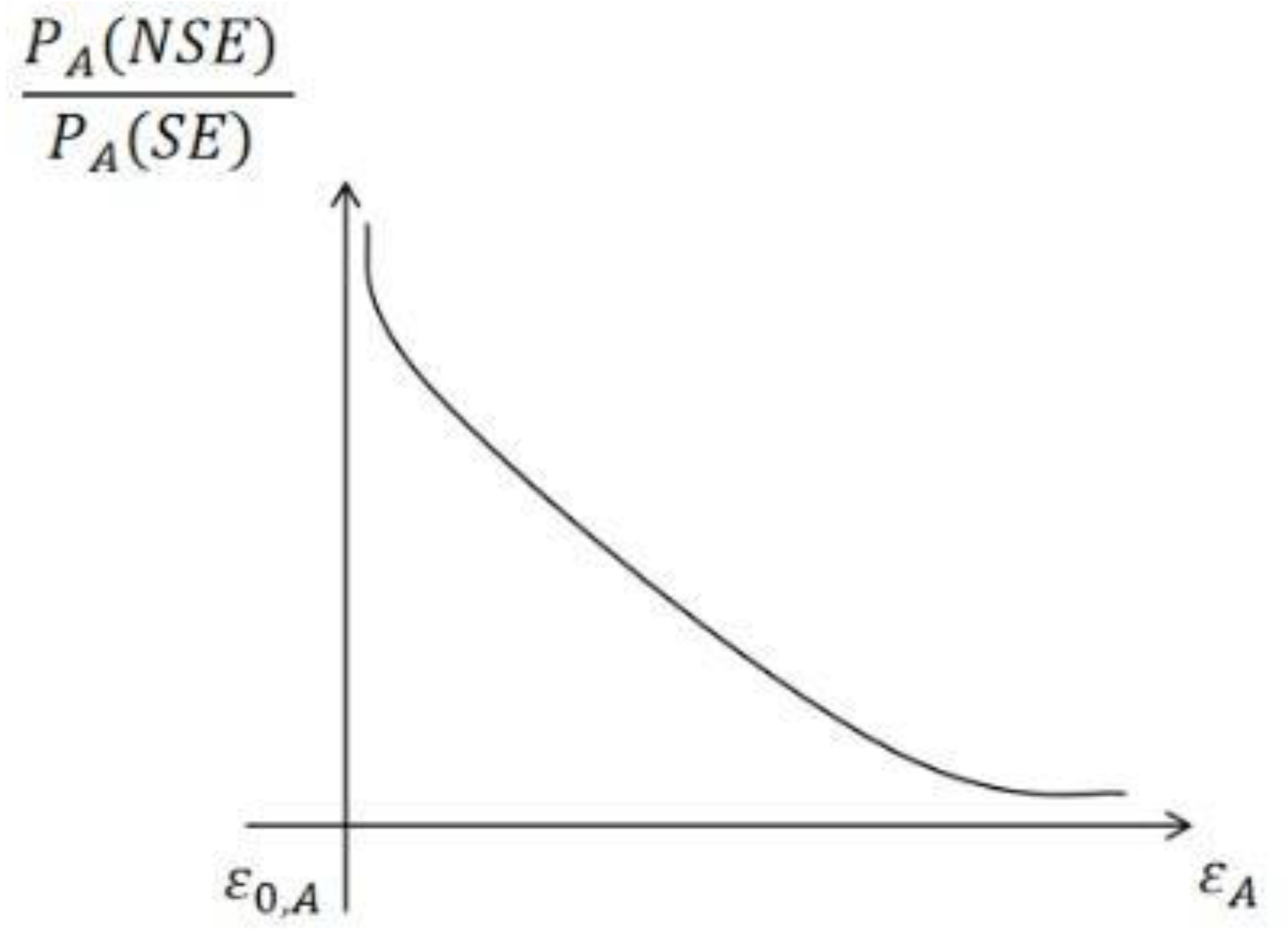

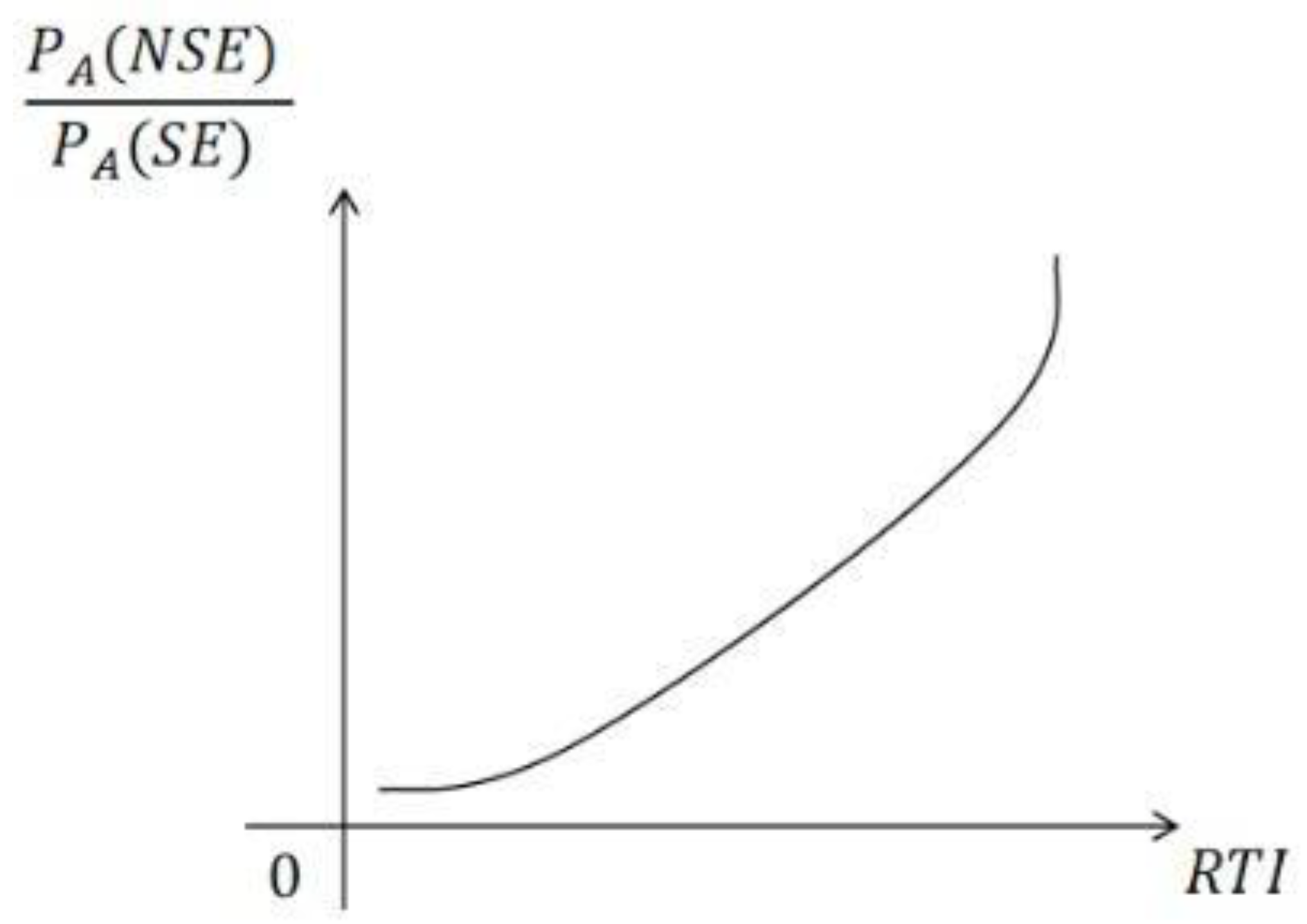

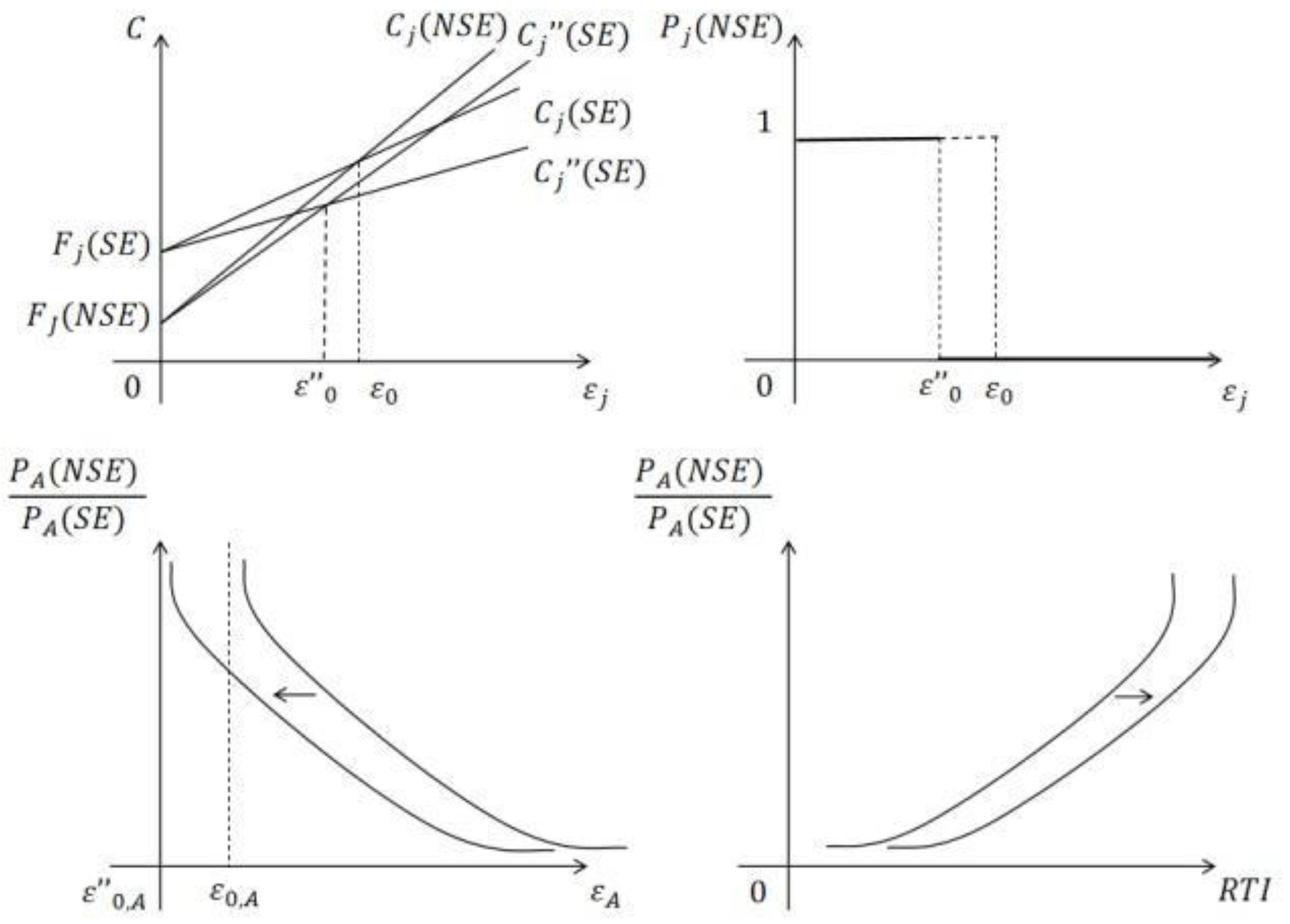

| 1 | To illustrate this intuition clearly, a simple formula derivation of Assumptions and Hypothesis was raised in Appendix A in the end of the text. |

| 2 | Some studies applied U.S. datasets O*NET to calculate RTI (Autor and Dorn, 2013; Cortes, 2016). However, task data from O*NET was gathered from few incumbents or experts (around 20-50) based on working information merely in U.S.. Further more, O*NET RTI was hinged on U.S. occupation code SOC, while PIAAC data used ISCO occupation code. There might be loss of accuracy when transforming occupation code if applying O*NET RTI. Since the study aims to test a universal impact of RTI on employment relations and to test heterogeneous effect of various social contexts, the author decided not to use O*NET and to use PIAAC to calculate RTI. |

| 3 | PIAAC also has datasets in 2014 and 2017. However, numbers of survey countries are much lower: 9 in 2014 and 6 in 2017, compare to 24 in 2012. Though the data is relatively old, recent studies used it for it high quality (Hämäläinen et al., 2021; Van Nieuwenhove and De Wever, 2022). Therefore, the study uses 2012 datasets to test Hypothesis. |

Appendix A: The Formula Derivation of Intuition

References

- Acemoglu D and D H Autor. (2011). Skills, Tasks and Technologies: Implications for Employment and Earnings. Handbook of Labor Economics (1043-1171). Elsevier Science Ltd.

- Acemoglu D and P Restrepo. The Race Between Man and Machine: Implications of Technology for Growth, Factor Shares, and Employment. American Economic Review 2018, 6, 1488–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu D and P Restrepo. Tasks, Automation, and the Rise in U.S. Wage Inequality. Econometrica 2022, 90, 1973–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akcomak S, S Kok and H Rojas-Romagosa. Technology Offshoring and the Task Content of Occupations in the United Kingdom. International Labour Review 2015, 155, 201–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B. Migration, Immigration Controls and the Fashioning of Precarious Workers. Work Employment and Society 2010, 24, 300–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor D H and D Dorn. The Growth of Low-Skill Service Jobs and the Polarization of the Us Labor Market. American Economic Review 2013, 5, 1553–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor D H, F Levy and R J Murnane. The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration. Quarterly Journal of Economics 2003, 118, 1279–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor D H, L F Katz and M S Kearney. The Polarization of the U.S. Labor Market. American Economic Review 2006, 2, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor, D. The Polarization of Job Opportunities in the U.S. Labor Market: Implications for Employment and Earnings. Center for American Progress and the Hamilton Project 2010, 6, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bárány Z L and C Siegel. Job Polarization and Structural Change. American Economic Journal. Macroeconomics 2018, 10, 57–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbieri P and S Scherer. Labour Market Flexibilization and its Consequences in Italy. European Sociological Review 2009, 25, 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barley S R, B A Bechky and F J Milliken. The Changing Nature of Work: Careers, Identities, and Work Lives in the 21St Century. Academy of Management Discoveries 2017, 2, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biemann T, H Zacher and D C Feldman. Career Patterns: A Twenty-Year Panel Study. Journal of Vocational Behavior 2012, 81, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blair, H. 'You're Only as Good as Your Last Job': The Labour Process and Labour Market in the British Film Industry. Work Employment and Society 2001, 15, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth A L and J C van Ours. Part-Time Jobs: What Women Want? Journal of Population Economics 2013, 26, 263–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busilacchi G, G Gallo and M Luppi. I would Like to but I Cannot: What Influences the Involuntariness of Part-Time Employment in Italy. Social Indicators Research 2024, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Cahuc P, S Carcillo and A Zylberberg. (2014). Labor Economics The MIT Press.

- Caro D H, K S Cortina and J S Eccles. Socioeconomic Background, Education, and Labor Force Outcomes: Evidence From a Regional U.S. Sample. British Journal of Sociology of Education 2015, 36, 934–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casey C and P Alach. 'Just a Temp?' - Women, Temporary Employment and Lifestyle. Work Employment and Society 2004, 18, 459–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connelly C E and D G Gallagher. Emerging Trends in Contingent Work Research. Journal of Management 2004, 30, 959–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes G, M. Where Have the Middle-Wage Workers Gone? A Study of Polarization Using Panel Data. Journal of Labor Economics 2016, 34, 63–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebenstein A, A Harrison, M McMillan and S Phillips. Estimating the Impact of Trade and Offshoring on American Workers Using the Current Population Surveys. Review of Economics and Statistics 2014, 96, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eloundou T, S Manning, P Mishkin and D Rock. (2023). GPTs are GPTs: An Early Look at the Labor Market Impact Potential of Large Language Models. Arxiv, arXiv:2303.10130.

- Esposito P and S Scicchitano. Educational Mismatch and Labour Market Transitions in Italy: Is there an Unemployment Trap? Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 2022, 61, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito P and S Scicchitano. Drivers of Skill Mismatch Among Italian Graduates: The Role of Personality Traits. Applied Economics 2023, 55, 4642–4663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantom N J and U Serajuddin. (2016). The World Bank's Classification of Countries by Income. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series.

- Fernández-Macías E and J Hurley. Routine-Biased Technical Change and Job Polarization in Europe. Socio-Economic Review 2017, 3, 563–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca T, F Lima and S C Pereira. Job Polarization, Technological Change and Routinization: Evidence for Portugal. Labour Economics 2018, 51, 317–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey C B and M A Osborne. The Future of Employment: How Susceptible are Jobs to Computerisation? Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2017, 114, 254–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George E and P Chattopadhyay. (2015) Non-Standard Work and Workers: Organizational Implications. ILO Geneva, Switzerland.

- Goos M and A Manning. Lousy and Lovely Jobs:the Rising Polarization of Work in Britain. Review of Economics and Statistics 2007, 89, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goos M, A Manning and A Salomons. Explaining Job Polarization: Routine-Biased Technological Change and Offshoring. American Economic Review 2014, 104, 2509–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen R, K Nissinen, J Mannonen, J Lämsä, K Leino and M Taajamo. Understanding Teaching Professionals' Digital Competence: What Do PIAAC and TALIS Reveal About Technology-Related Skills, Attitudes, and Knowledge? Computers in Human Behavior 2021, 117, 106672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy W, R Keister and P Lewandowski. Educational Upgrading, Structural Change and the Task Composition of Jobs in Europe. Economics of Transition 2018, 26, 201–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey G, C Rhodes, S J Vachhani and K Williams. Neo-Villeiny and the Service Sector: The Case of Hyper Flexible and Precarious Work in Fitness Centres. Work, Employment and Society 2017, 31, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman D and A Rafferty. The Convergence and Divergence of Job Discretion Between Occupations and Institutional Regimes in Europe From 1995 to 2010. Journal of Management Studies 2018, 55, 619–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horemans, J. Polarisation of Non-Standard Employment in Europe: Exploring a Missing Piece of the Inequality Puzzle. Social Indicators Research 2016, 125, 171–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg A, L. Nonstandard Employment Relations: Part-Time, Temporary and Contract Work. Review of Sociology 2000, 26, 341–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg A, L. Flexible Firms and Labor Market Segmentation: Effects of Workplace Restructuring on Jobs and Workers. Work and Occupations 2003, 30, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg A L and P V Marsden. Externalizing Organizational Activities: Where and How U.S. Establishments Use Employment Intermediaries. Socio-Economic Review 2005, 3, 389–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmeyer, C. Trade Union Decline, Deindustrialization, and Rising Income Inequality in the United States 2018, 1947 to 2015. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 2018, 57, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korinek, A. (2023). Language Models and Cognitive Automation for Economic Research: National Bureau of Economic Research No. w30957.

- Lazear E, P. (1995). Personnel Economics. MIT press.

- Lee, C. International Migration, Deindustrialization and Union Decline in 16 Affluent OECD Countries, 1962-1997. Social Forces, 2005, 84, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughlin C and J Barling. Young Workers' Work Values, Attitudes, and Behaviours. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 2001, 74, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald R and A Giazitzoglu. Youth, Enterprise and Precarity: Or, What is, and What is Wrong with, the ‘Gig Economy’? Journal of Sociology 2019, 55, 724–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcolin L, S Miroudot and M Squicciarini. To be (Routine) Or Not to be (Routine), that is the Question: A Cross-Country Task-Based Answer. Industrial and Corporate Change 2019, 28, 477–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minardi S, C Hornberg, P Barbieri and H Solga. (2023). The Link Between Computer Use and Job Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Job Tasks and Task Discretion. British Journal of Industrial Relations 2023. [CrossRef]

- Olsen K M and A L Kalleberg. Non-Standard Work in Two Different Employment Regimes: Norway and the United States. Work Employment and Society 2004, 18, 321–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oster, E. Unobservable Selection and Coefficient Stability: Theory and Evidence. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 2019, 37, 187–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer J and J N Baron. Taking the Workers Back Out: Recent Trends in the Structuring of Employment. Research in Organizational Behavior 1988, 10, 257–303. [Google Scholar]

- Reijnders L S and G J de Vries. Technology, Offshoring and the Rise of Non-Routine Jobs. Journal of Development Economics 2018, 135, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rica S D L, L Gortazar and P Lewandowski. Job Tasks and Wages in Developed Countries: Evidence From PIAAC. Labour Economics 2020, 65, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taplin I, M. Flexible Production, Rigid Jobs: Lessons From the Clothing Industry. Work and Occupations 1995, 22, 412–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilly, C. Reasons for the Continuing Growth of Part-Time Employment. Monthly Lab. Rev. 1991, 114, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Uzzi B and Z I Barsness. Contingent Employment in British Establishments: Organizational Determinants of the Use of Fixed-Term Hires and Part-Time Workers. Social Forces 1998, 76, 967–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nieuwenhove L and B De Wever. Why are Low-Educated Adults Underrepresented in Adult Education? Studying the Role of Educational Background in Expressing Learning Needs and Barriers. Studies in Continuing Education 2022, 44, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong C and M A Campion. Development and Test of a Task Level Model of Motivational Job Design. Journal of Applied Psychology 1991, 76, 825–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Components of routine tasks | Describe | N | mean | std. | min | max |

| Teaching People (inverse) | How often Does your Job usually involve instructing, training or teaching people, individually or in groups? | 73,993 | 3.437 | 1.529 | 1 | 5 |

| Presentations (inverse) | How often Does your Job usually involve making speeches or giving presentations in front of five or more people? | 73,993 | 4.163 | 1.244 | 1 | 5 |

| Advising People (inverse) | How often Does your Job usually involve advising people? | 73,993 | 2.561 | 1.589 | 1 | 5 |

| Planning Own Activities (inverse) | How often Does your Job usually involve planning your own activities? | 73,993 | 2.109 | 1.563 | 1 | 5 |

| Organizing Own Time (inverse) | How often Does your Job usually involve organizing your own time? | 73,993 | 1.976 | 1.548 | 1 | 5 |

| Sequence Tasks (inverse) | To what extent can you choose or change the sequence of your tasks? | 73,993 | 2.701 | 1.285 | 1 | 5 |

| Flexibility (inverse) | To what extent can you choose or change how you do your work? | 73,993 | 2.663 | 1.255 | 1 | 5 |

| VARIABLES | N | Mean | Std. | Min | Max |

| non-standard employment | 73,993 | 0.102 | 0.302 | 0 | 1 |

| RTI | 73,993 | 2.849 | 1.039 | 1 | 5 |

| male | 73,993 | 0.513 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| living_with_partner | 73,993 | 0.756 | 0.429 | 0 | 1 |

| child | 73,993 | 0.669 | 0.471 | 0 | 1 |

| less_than_high_school | 73,993 | 0.109 | 0.311 | 0 | 1 |

| above_high_school | 73,993 | 0.489 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| high_school | 73,993 | 0.402 | 0.490 | 0 | 1 |

| working_hours_40less | 73,993 | 0.373 | 0.484 | 0 | 1 |

| working_hours_40_50 | 73,993 | 0.498 | 0.500 | 0 | 1 |

| working_hours_50_60 | 73,993 | 0.085 | 0.279 | 0 | 1 |

| working_hours_60more | 73,993 | 0.043 | 0.204 | 0 | 1 |

| age_25less | 73,993 | 0.095 | 0.293 | 0 | 1 |

| age_25_54 | 73,993 | 0.749 | 0.434 | 0 | 1 |

| age_55_65 | 73,993 | 0.156 | 0.363 | 0 | 1 |

| income_less10 | 73,993 | 0.093 | 0.291 | 0 | 1 |

| income_10_25 | 73,993 | 0.150 | 0.357 | 0 | 1 |

| income_25_50 | 73,993 | 0.304 | 0.460 | 0 | 1 |

| income_50_75 | 73,993 | 0.217 | 0.412 | 0 | 1 |

| income_75_90 | 73,993 | 0.133 | 0.340 | 0 | 1 |

| income_90more | 73,993 | 0.103 | 0.304 | 0 | 1 |

| father_edu | 73,993 | 1.718 | 0.746 | 1 | 3 |

| mother_edu | 73,993 | 1.619 | 0.725 | 1 | 3 |

| numeracy | 73,993 | 1.577 | 1.217 | 0 | 6.050 |

| reading | 73,993 | 1.914 | 1.054 | 0 | 7.021 |

| migrant | 73,993 | 0.099 | 0.299 | 0 | 1 |

| native_speaker | 73,993 | 0.918 | 0.275 | 0 | 1 |

| overskilled | 73,993 | 0.838 | 0.369 | 0 | 1 |

| underskilled | 73,993 | 0.339 | 0.473 | 0 | 1 |

| overeducated | 73,993 | 0.197 | 0.397 | 0 | 1 |

| undereducated | 73,993 | 0.106 | 0.307 | 0 | 1 |

| shareinfo | 73,993 | 4.312 | 1.164 | 1 | 5 |

| problemsolv | 73,993 | 3.867 | 1.308 | 1 | 5 |

| complex | 73,993 | 2.796 | 1.305 | 1 | 5 |

| physical | 73,993 | 3.038 | 1.811 | 1 | 5 |

| finger | 73,993 | 3.780 | 1.709 | 1 | 5 |

| cooperate | 73,993 | 3.454 | 1.417 | 1 | 5 |

| a:the definition of all variables are shown in Table B1. b: Marital status may affect employment status. The datasets have no marital status, “living with partner” was applied as a proxy. | |||||

| Group | Countries | Group | Countries |

| Anglo Saxon | New Zealand | Nodic | Denmark |

| United Kingdom | Norway | ||

| United States | Sweden | ||

| Middle East EU | Czech Republic | South West EU | Austria |

| Estonia | Belgium | ||

| Hungary | Germany | ||

| Lithuania | France | ||

| Poland | Greece | ||

| Slovak Republic | Ireland | ||

| Slovenia | Italy | ||

| East Asia | Japan | Netherlands | |

| Korea Republic | Spain | ||

| a: Detail statistics of non-standard employment and RTI of each groups are shown in Table B4. | |||

| VARIABLES | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) |

| z_RTI | 1.264*** | 1.144*** | 1.124*** | 1.133*** | 1.124*** |

| (0.015) | (0.019) | (0.020) | (0.024) | (0.025) | |

| Constant | 0.111*** | 0.049*** | 0.037*** | 1,598.894*** | 821.78*** |

| (0.001) | (0.005) | (0.004) | (567.486) | (316.595) | |

| Individual Controls | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Organizational Controls | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Country Controls | √ | √ | |||

| Industry Fixed Effect | √ | ||||

| Observations | 73,993 | 73,993 | 73,993 | 73,993 | 73,993 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.008 | 0.064 | 0.085 | 0.398 | 0.408 |

| LL | -24112.1 | -22735.72 | -22239.47 | -14634.66 | -14380.49 |

| AIC | 48228.19 | 45537.44 | 44560.93 | 29371.33 | 29038.97 |

| seEform in parentheses; *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1; the VIF of all independent variables are less than 10. In the e-form of coefficient, the result minus 1 is the changing odds-ratio of dependent variable for every change of independent variable. | |||||

| VARIABLES | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| z_RTI | 1.145*** | 1.428*** | 1.136*** | 1.435*** |

| (0.025) | (0.096) | (0.026) | (0.098) | |

| Anglo_Saxon | 0.017*** | 0.017*** | 0.016*** | 0.016*** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| Middle_East_EU | 0.01*** | 0.01*** | 0.01*** | 0.01*** |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| East_Asia | 0.016*** | 0.017*** | 0.013*** | 0.014*** |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.003) | (0.004) | |

| South_West_EU | 0.01*** | 0.011*** | 0.013*** | 0.013*** |

| (0.002) | (0.002) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| Nordic (referee group) | - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - | |

| Anglo_Saxon_z_RTI | 0.764*** | 0.765*** | ||

| (0.057) | (0.057) | |||

| Middle_East_EU_z_RTI | 0.818*** | 0.787*** | ||

| (0.063) | (0.061) | |||

| East_Asia_z_RTI | 0.781*** | 0.767*** | ||

| (0.060) | (0.060) | |||

| South_West_EU_z_RTI | 0.797*** | 0.788*** | ||

| (0.057) | (0.057) | |||

| Constant | 918,833.084*** | 870,234.058*** | 1825478.453*** | 1740741.184*** |

| (635,962.156) | (604,061.379) | (1287979.406) | (1231838.829) | |

| Individual Controls | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Organizational Controls | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Country Controls | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| Industry Fixed Effect | √ | √ | ||

| Observations | 73,993 | 73,993 | 73,993 | 73,993 |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.41 | 0.411 | 0.419 | 0.419 |

| LL | -14329.11 | -14322.05 | -14120.41 | -14113.36 |

| AIC | 28768.21 | 28762.09 | 28526.81 | 28520.71 |

| seEform in parentheses; *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1 | ||||

| Bound Estimate | Inputs from Regressions | Other Inputs | |||

| delta | Coeff. | R2 | R_max | Beta | |

| 1.07815 | Uncontrolled | 0.02186 | 0.005 | 0.8 | 0.1 |

| Controlled | 0.00498 | 0.357 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).