Submitted:

08 October 2024

Posted:

09 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Settings

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Population

2.4. Sampling and Sample Size

2.5. Data Collection Tool

2.5.1. Knowledge of Healthcare Ethics

2.5.2. Practise of Healthcare Ethics

2.5.3. Demographics

2.6. Data Collection Procedure

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

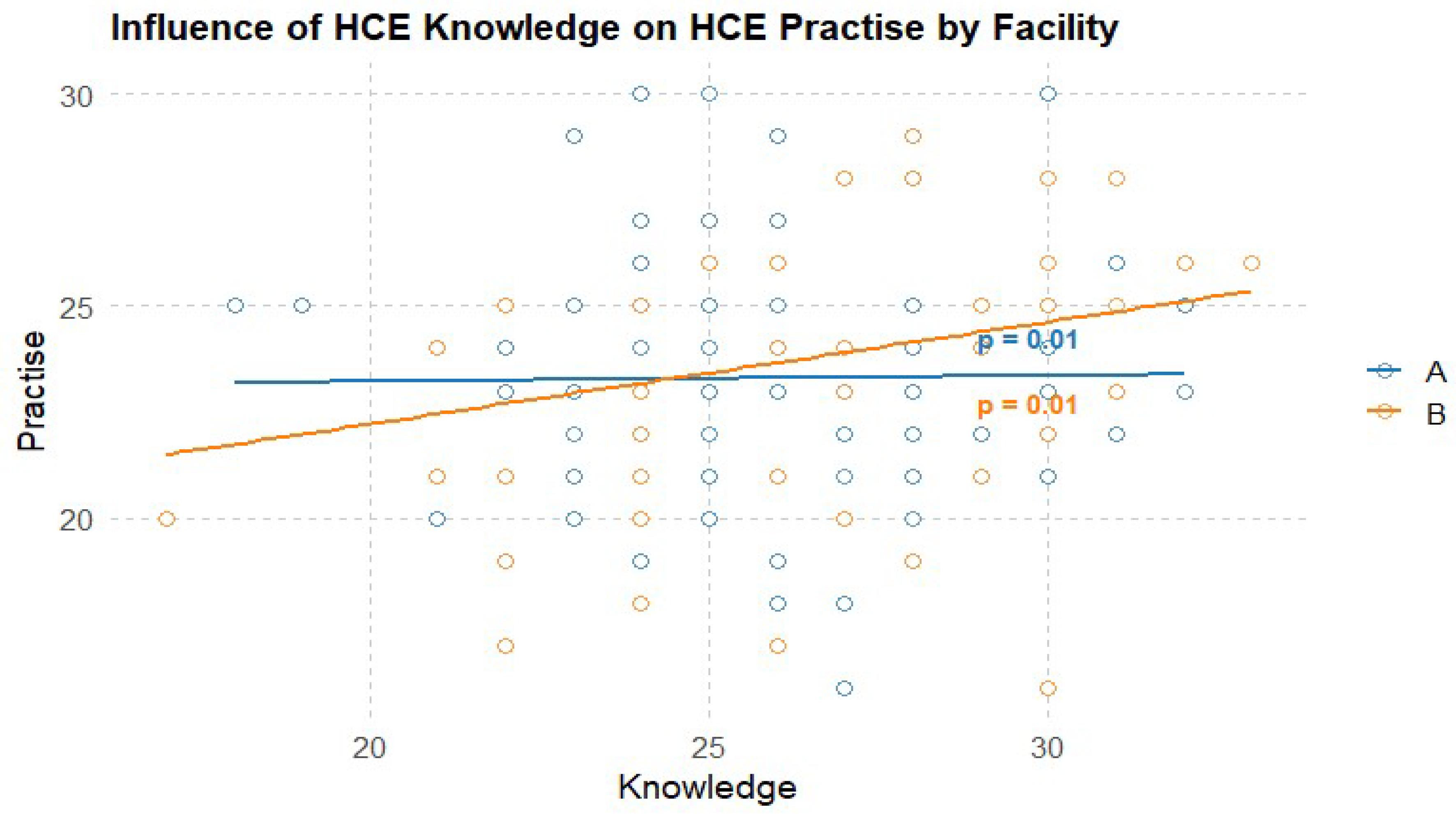

3.1. Influence of HCE Knowledge on HCE Practise

3.2. Key Influencing Factors of Healthcare Ethics Practice

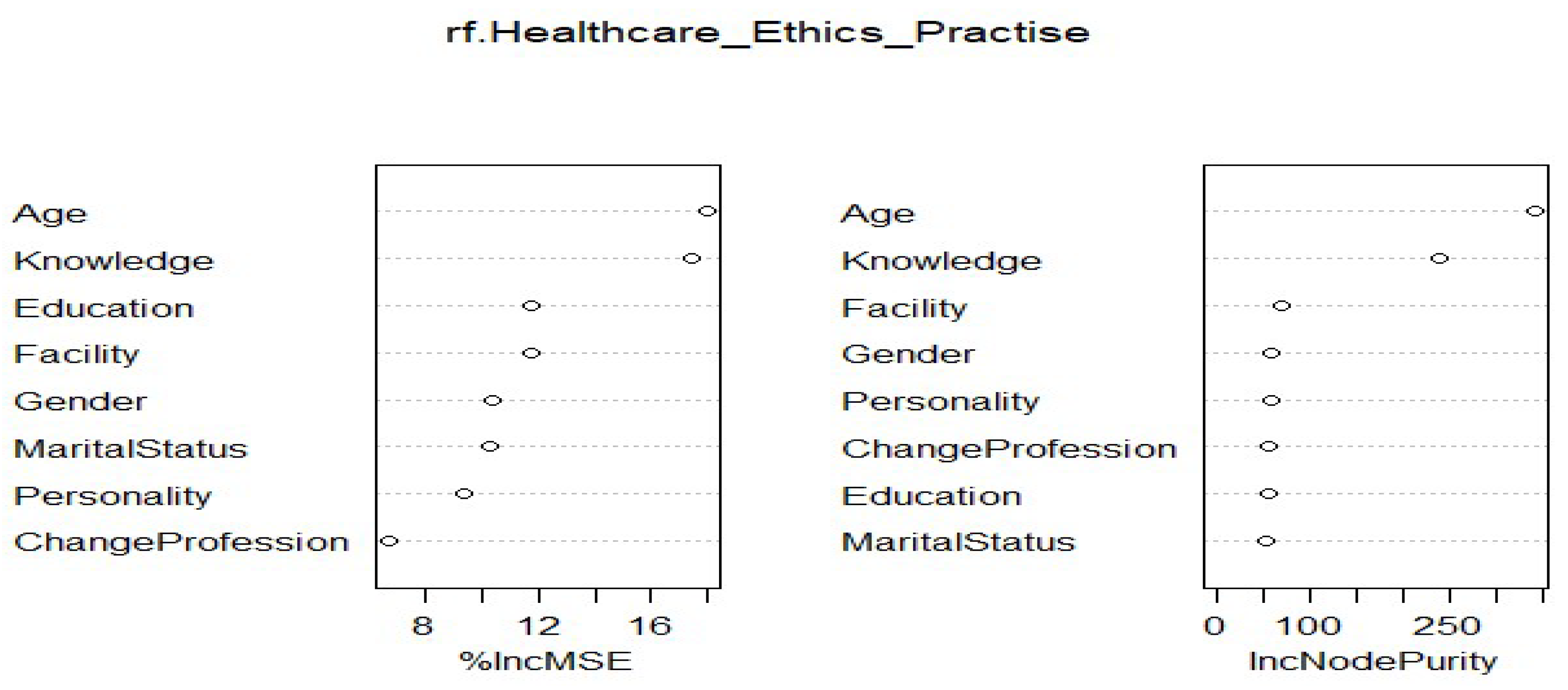

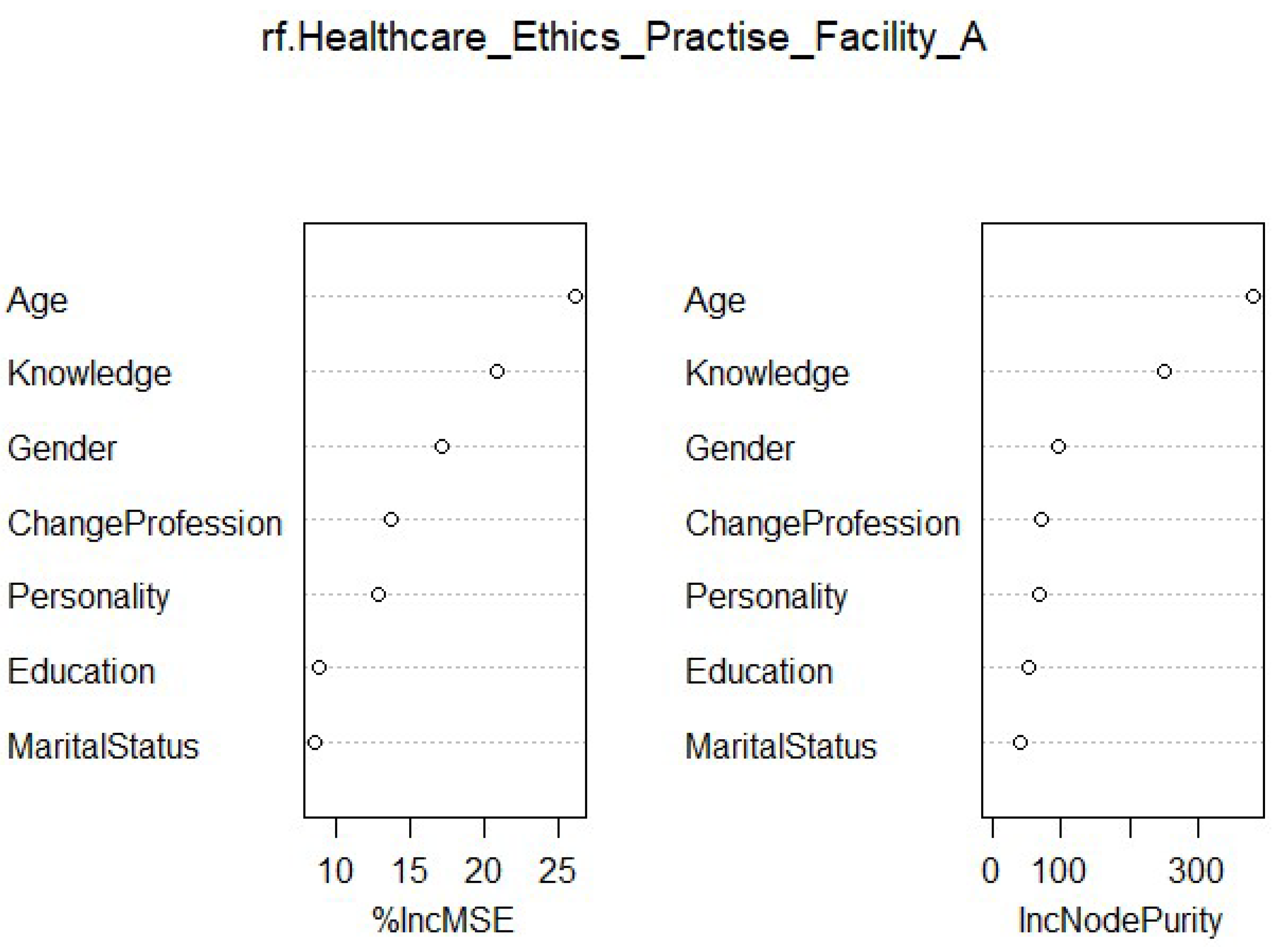

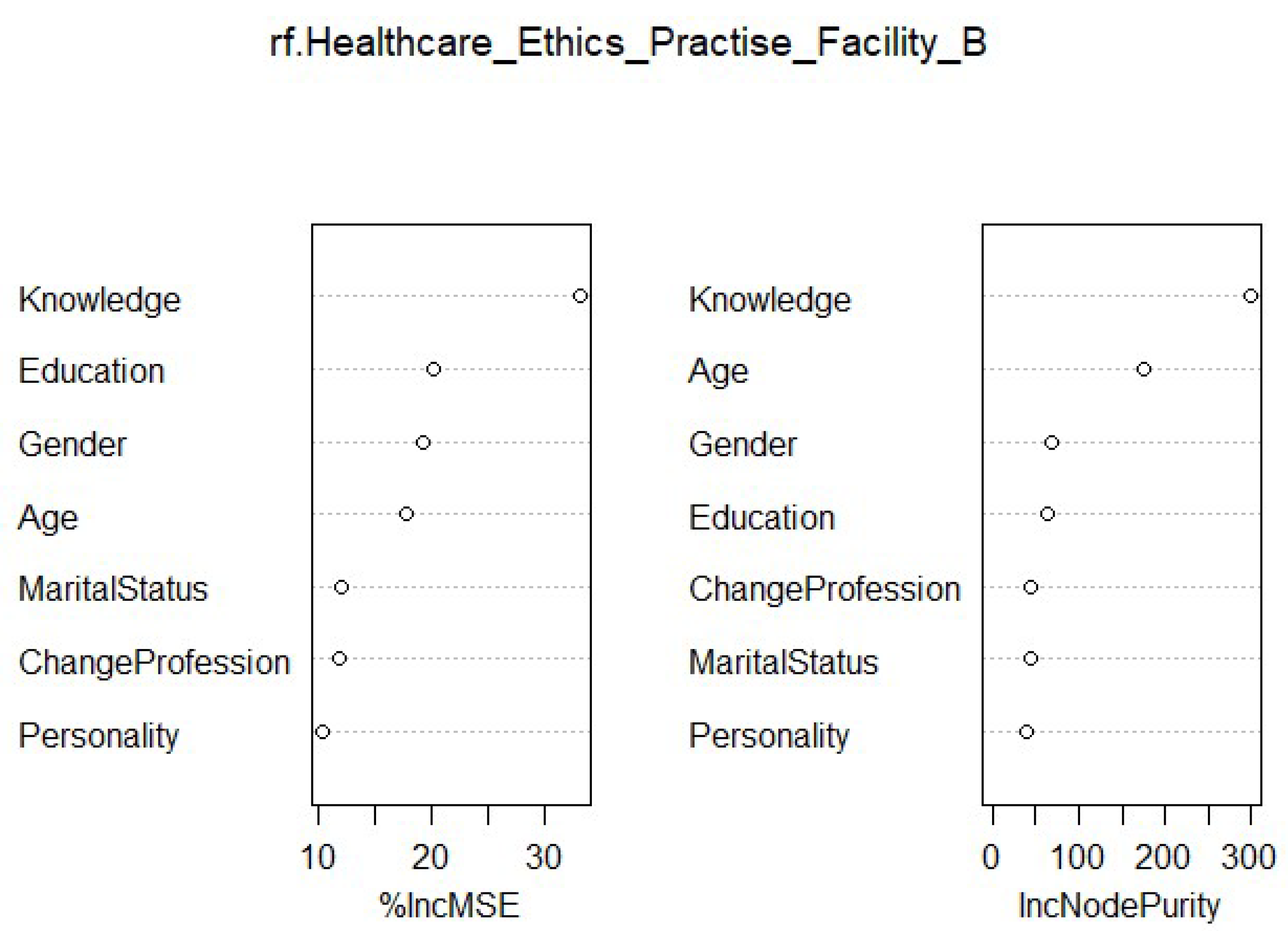

3.3. Order of Influencing Factors of Healthcare Ethics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion and Implications for Practice

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Unnikrishnan, B.; Kanchan, T.; Kulkarni, V.; Kumar, N.; Papanna, M.K.; Rekha, T.; Mithra, P. Perceptions and practices of medical practitioners towards ethics in medical practice–A study from coastal South India. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 2014, 22, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faden, R.R.; Kass, N.E.; Goodman, S.N.; Pronovost, P.; Tunis, S.; Beauchamp, T.L. An ethics framework for a learning health care system: a departure from traditional research ethics and clinical ethics. Hastings Center Report 2013, 43, S16–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.; Ali, H.S.; Mahmoud, M.A. Prioritizing Well-being of Patients through Consideration of Ethical Principles in Healthcare Settings: Concepts and Practices. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy 2020, 11, 643–648. [Google Scholar]

- Quitio Arevalo, C.M.; Guambuguete, J.I. Principios éticos del cuidado enfermero en seguridad. relatos de pacientes dados de alta. Hospital Alfredo Noboa Montenegro octubre 2019–febrero 2020. bachelor’s thesis, Universidad Estatal de Bolìvar: Carrera de Enfermeria.

- Jones-Bonofiglio, K. Health care ethics through the lens of moral distress; Springer: Cham, 27 Aug 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wesarat, P.O.; Mathew, J. Linking ethical standards for healthcare professionals with Indian cultural values. Asia Pacific Journal of Health Management 2021, 16, 49–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, M.A.; Bobinski, M.A.; Orentlicher, D.; Cohen, I.G.; Bagley, N.; Sawicki, N.N. Health Care Law and Ethics: [Connected EBook]; Aspen Publishing, 19 Feb 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi, S. Global Ethical Principles in Healthcare Networks, Including Debates on Euthanasia and Abortion. Cureus 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepper, M.S.; Slabbert, M.N. Is South Africa on the verge of a medical malpractice litigation storm? South African Journal of Bioethics and Law 2011, 4, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Moodley, K.; Kabanda, S.M.; Kleinsmidt, A.; Obasa, A.E. COVID-19 underscores the important role of Clinical Ethics Committees in Africa. BMC Medical Ethics 2021, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastav, S. Medico-Legal Practices and Doctor-Patient Relationship in India’s Evolving Healthcare Landscape. Healthcare Administration and Managerial Training in the 21st Century 2024 (pp. 107-146). IGI Global.

- Monsudi, K.F.; Oladele, T.O.; Nasir, A.A.; Ayanniyi, A.A. Medical ethics in sub-Sahara Africa: closing the gaps. African Health Sciences 2015, 15, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, A.M. Baseline Survey of knowledge, attitude, and practice of healthcare ethics, in healthcare practitioners of a tertiary healthcare institution in Ghana, a Sub-Saharan Country. Bangladesh Journal of Bioethics 2023, 14, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, P.; Ansah, E.W.; Sambah, F. Ethics in healthcare: Knowledge, attitude, and practices of nurses in the Cape Coast Metropolis of Ghana. PloS one 2022, 17, e0263557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ofosu-Poku, R. Perspective Chapter: Who Is Making Decisions? An open letter to healthcare professionals in the developing world. In Suggestions for Addressing Clinical and Non-Clinical Issues in Palliative Care; 2021; Volume 325. [Google Scholar]

- Kirilmaz, H.; Akbolat, M.; Kahraman, G. Research about the ethical sensitivity of healthcare professionals. International Journal of Health Sciences 2015, 3, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadakia, E. Navigating the Complexities of Medical Error and Its Ethical Implications. Doctoral dissertation, Temple University. Libraries.

- Donkor, N.T.; Andrews, L.D. Ethics, culture and nursing practice in Ghana. International nursing review 2011, 58, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amuasi, J.H.; Kyere, A.K.; Schandorf, C.; Fletcher, J.J.; Boadu, M.; Addison, E.K.; Hasford, F.; Sosu, E.K.; Sackey, T.A.; Tagoe, S.N.; Inkoom, S. Medical physics practice and training in Ghana. Physica medica 2016, 32, 826–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, N.; Samuel, A.; Geta, A.; Desalegn, F.; Gebru, L.; Tadele, T.; Genet, E.; Abate, M.; Jemal, K. Clinical ethical practice and associated factors in healthcare facilities in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Medical Ethics 2022, 23, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, F.; Tarar, A.Z.; Farooq, M.W.; Majeed, F.; Riaz, A.; Imran, M.; Saleem, J.; Ullah, S.; Haider, N.; Tahir, M.N. Assessing medical doctors’ knowledge about medical ethics in health practices: A cross-sectional survey in Lahore, Pakistan. International Journal of Health Sciences 2023, 7, 960–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Statistical Service. In Population and Housing Census 2021. Available from: https://census2021.statsghana.gov.gh.

- Baatiema, L. The knowledge-practice gap: Evidence-based practice for acute stroke care in Ghana. Doctoral dissertation, Australian Catholic University.

- Bhardwaj, A.; Chopra, M.; Mithra, P.; Singh, A.; Siddiqui, A.; Rajesh, D.R. Current Status of Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices towards Healthcare Ethics Among Doctors and Nurses from Northern India-A Multicentre Study. Pravara Medical Review 2014, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline for selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of chiropractic medicine 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petkovic, D.; Altman, R.; Wong, M.; Vigil, A. Improving the explainability of Random Forest classifier–user-centered approach. InPacific Symposium on Biocomputing. Pacific Symposium on Biocomputing 2018 (Vol. 23, p. 204). NIH Public Access.

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J.H.; Friedman, J.H. The elements of statistical learning: data mining, inference, and prediction; Springer: New York, Aug 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Statnikov, A.; Wang, L.; Aliferis, C.F. A comprehensive comparison of random forests and support vector machines for microarray-based cancer classification. BMC bioinformatics 2008, 9, 1–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulesteix, A.L.; Janitza, S.; Kruppa, J.; König, I.R. Overview of random forest methodology and practical guidance with emphasis on computational biology and bioinformatics. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2012, 2, 493–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, F.; Luo, Z. An experimental study of the intrinsic stability of random forest variable importance measures. BMC bioinformatics 2016, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhn, S.; Egert, B.; Neumann, S.; Steinbeck, C. Building blocks for automated elucidation of metabolites: Machine learning methods for NMR prediction. BMC bioinformatics 2008, 9, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mortell, M. Theory-practice-ethics: Is there a gap? A unique concept to reflect on. Acta Scientific Women’s Health 2019, 2, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.; Smith, J.; Phillips, J.D.; Falkenheimer, S. Solving Ethical Dilemmas in International Healthcare Professional Education: A Case Study Using a Revised Ethical Model. Christian Journal for Global Health 2018, 5, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, K.; Kitchlew, N. Ethical Leadership and Institutionalization of Ethics: Intervening Role of Personal Factors. InAcademy of Management Proceedings 2021 (Vol. 2021, No. 1, p. 15215). Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510: Academy of Management.

- Gierczyk, M.; Harrison, T. The effects of gender on the Ethical Decision-making of Teachers, Doctors and Lawyers.

- Bhuyan, B.; Kumar, S.; Choudhury, S.; Kashyap, K. Impact of demographic factors on the ethical conduct of physicians in India. Indian Journal of Public Health 2020, 11, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etherington, C.; Boet, S. Why gender matters in the operating room: recommendations for a research agenda. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2018, 121, 997–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, D.R.; Luth, M.T. The effectiveness of ethics education: A quasi-experimental field study. Science and engineering ethics 2013, 19, 545–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banait, S.H.; Jain, J.Y.; Bokariya, P.R.; Khan, S.H. Effectiveness of healthcare ethics training in the undergraduate medical curriculum: A quasi-experimental study from rural India. Indian J Med Ethics 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Blázquez, F.J.; Ruiz-Hontangas, A.; López-Mora, C. Bioethical knowledge in students and health professionals: a systematic review. Frontiers in Medicine 2024, 11, 1252386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, S.; Shah, N. Impact of personality traits on ethical behavior. The Government-Annual Research Journal of Political Science 2018, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Niazazari, K.; Enayati, T.; Behnamfar, R.; Kahroodi, Z. Relationship between Professional Ethics and Job Commitment. Iran J Nurs. 2014, 27, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, K.L.; Jordens, C.F.; Kerridge, I. Contextualising professional ethics: The impact of the prison context on the practices and norms of health care practitioners. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 2014, 11, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total Sample | Facility A (n= 210) |

Facility B (n=172) | X2 P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | 0.41 | ||||||

| Man | 159 | 41.62 | 83 | 39.52 | 76 | 44.18 | |

| Woman | 223 | 58.38 | 127 | 60.48 | 96 | 55.82 | |

| Education Level | 0.03 | ||||||

| Diploma and below | 242 | 63.35 | 144 | 68.57 | 98 | 56.97 | |

| Above Diploma | 140 | 36.65 | 66 | 31.43 | 74 | 43.03 | |

| Personality | 0.22 | ||||||

| Introvert | 172 | 45.03 | 101 | 48.1 | 71 | 41.28 | |

| Extrovert | 210 | 54.97 | 109 | 51.9 | 101 | 58.72 | |

| Intention to change profession | 0.71 | ||||||

| Yes | 135 | 35.34 | 72 | 34.29 | 63 | 36.63 | |

| No | 247 | 64.66 | 138 | 65.71 | 109 | 63.37 | |

| Marital Status | 0.02 | ||||||

| Yes | 139 | 36.4 | 65 | 74 | 43.02 | ||

| No | 243 | 63.6 | 145 | 98 | 56.98 | ||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | T-Test P value | |

| Age | 28.30 | 5.37 | 27.80 | 5.22 | 29.00 | 5.47 | 0.02 |

| Knowledge of HCE | 26.30 | 2.83 | 26.30 | 2.67 | 26.30 | 2.67 | 0.98 |

| Practice of HCE | 23.50 | 2.94 | 23.30 | 2.87 | 23.7 | 3.01 | 0.16 |

| General | Facility A | Facility B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | %IncMSE | IncNodePurity | %IncMSE | IncNodePurity | %IncMSE | IncNodePurity |

| Age | 18.02 | 341.438 | 26.179 | 379.897 | 17.854 | 174.785 |

| Knowledge | 17.449 | 238.554 | 20.888 | 250.651 | 33.264 | 299.882 |

| Education | 11.773 | 56.529 | 8.943 | 52.882 | 20.206 | 64.906 |

| Personality | 9.31 | 59.79 | 12.811 | 67.6444 | 10.288 | 40.824 |

| Gender | 10.327 | 60.25711 | 17.105 | 96.327 | 19.358 | 67.862 |

| Intention to Change Profession | 6.642 | 57.304 | 13.781 | 70.4688 | 11.795 | 43.803 |

| Marital Status | 10.267 | 54.022 | 8.557 | 40.911 | 12.016 | 43.377 |

| Facility | 11.735 | 71.329 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).