Submitted:

07 October 2024

Posted:

10 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Pre-transport management activities can cause stress, injuries, and mortality in poultry. This study aimed to gather information about the current pre-transport practices (selection of unfit chickens, catching preparations, catching, and crating) for spent hens and broilers by questioning Flemish poultry farmers. The results showed that catching preparations such as an extra selection of chickens unfit for transport was performed by a minority of the poultry farmers, and that layer farmers were less in line with the EU-legislation for water and feed withdrawal than broiler farmers. All birds were caught inverted except for one broiler farmer who used mechanical catching (not yet common in Flanders). Additionally, mechanical catching may involve extra costs, increased biosecurity risks, and specific recommendations for the stable (height and width). The broiler farmers preferred mechanical catching for broiler catchers' well-being, while upright catching was considered better for animal welfare than catching more than three chickens by one/two legs, mechanically, or by wings. Awareness of the need to perform an extra selection by the poultry farmers before catching is required. Preparations like closing areas under the aviary system and removing litter (layers) can further streamline the process and reduce animal suffering.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Respondents

2.2. Questionnaires

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. General Information

3.2. Selection of Unfit Chickens During The Production Cycle

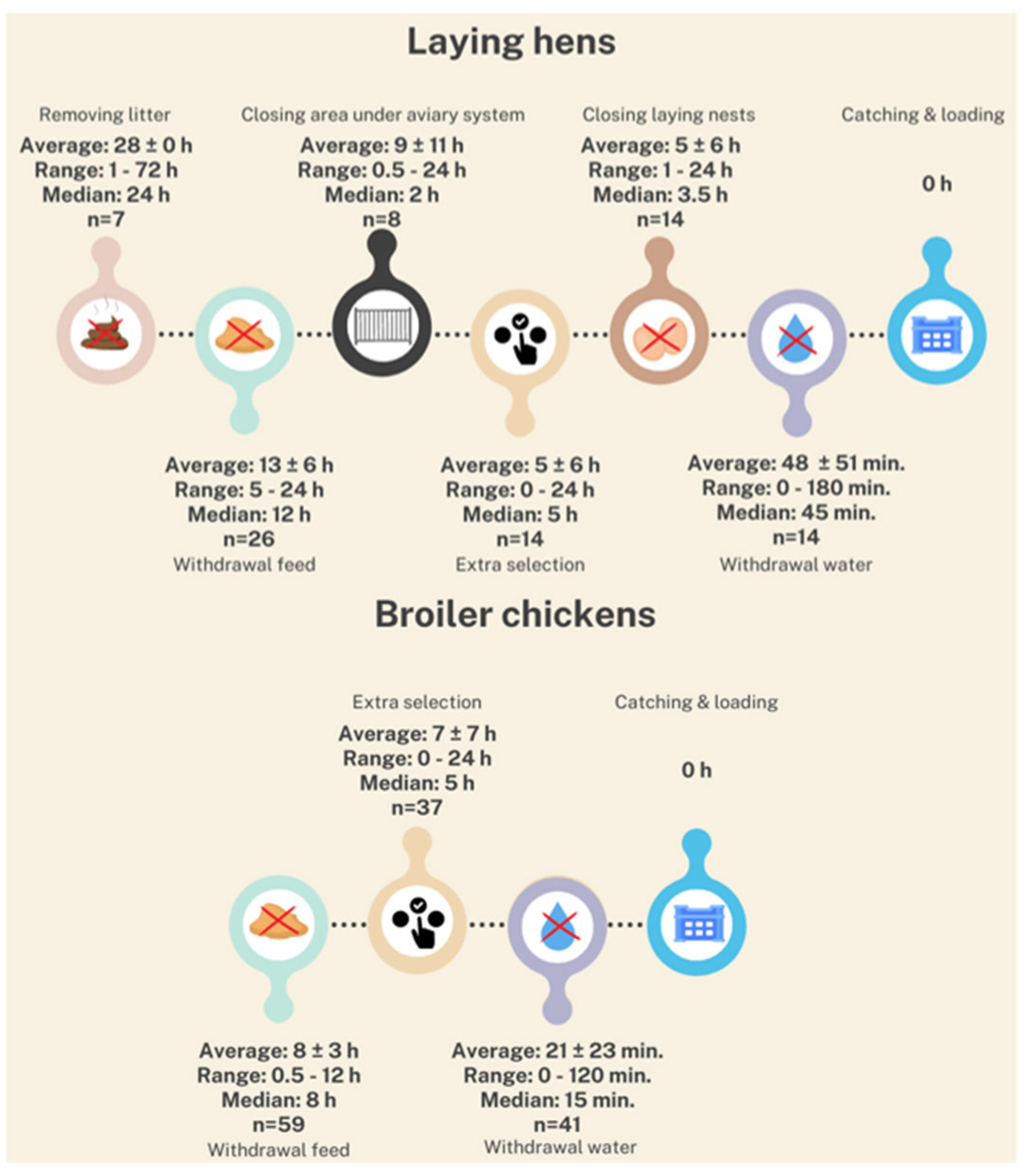

3.3. Preparations before Catching and Loading

3.1.1. Feed Withdrawal

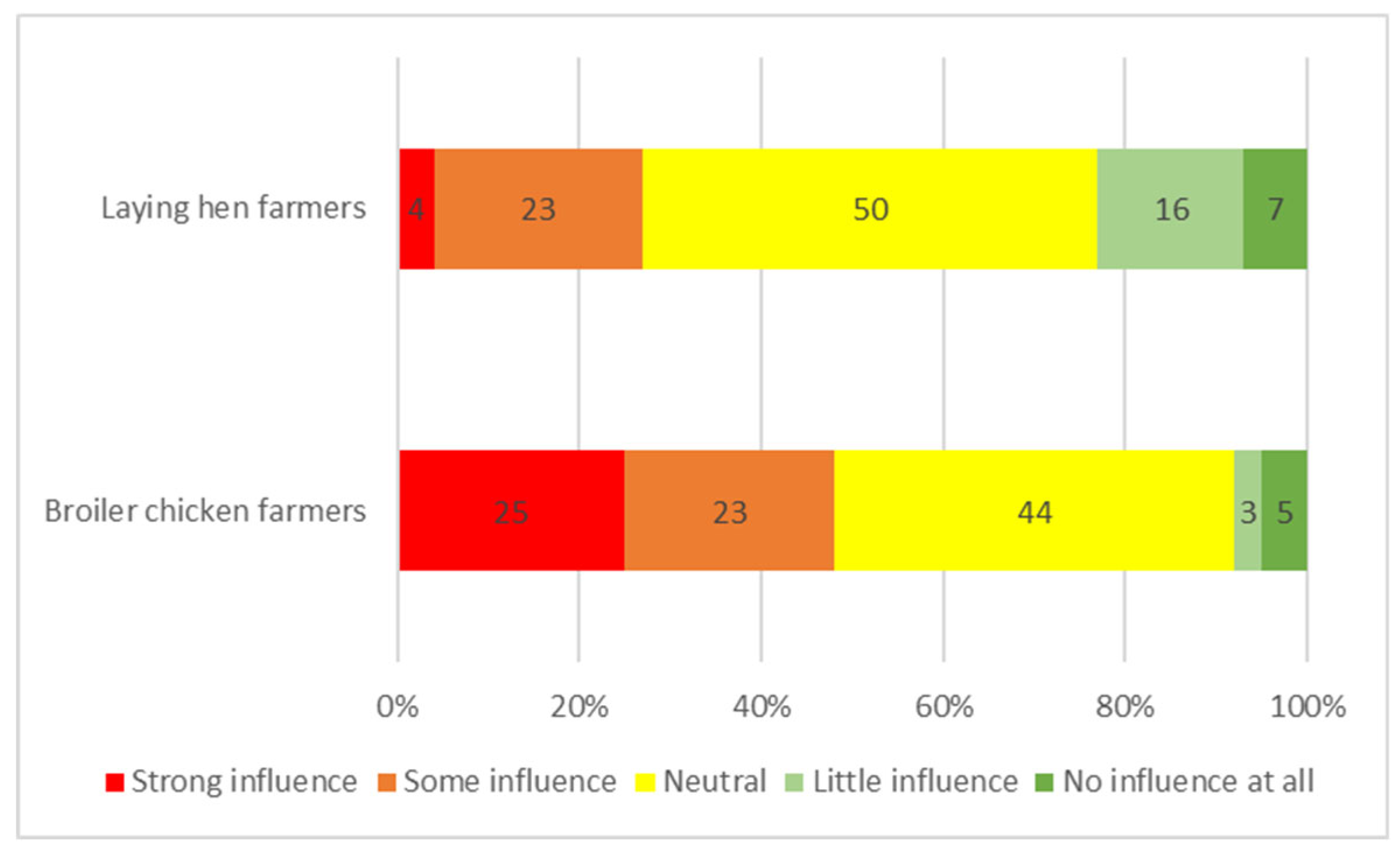

3.1.2. Extra selection before catching and loading

3.1.3. Water Withdrawal

3.1.1. Other Preparations Specific for Laying Hens

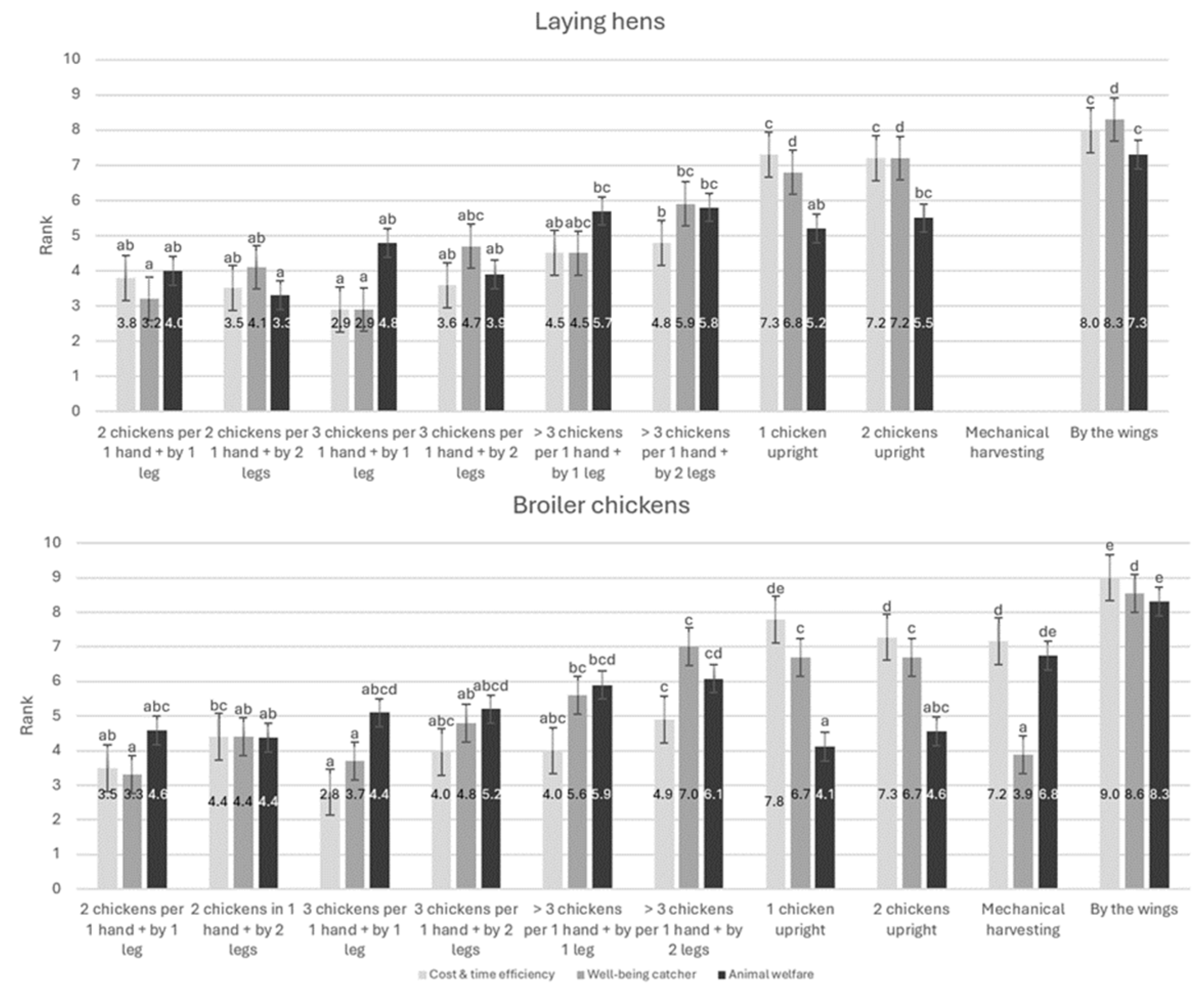

3.4. Catching and Crating for Transport

3.5. Farmers’ Opinion about Catching Methods

4. Conclusions

5. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gerpe, C.; Stratmann, A.; Bruckmaier, R.; Toscano, M.J. Examining the Catching, Carrying, and Crating Process during Depopulation of End-of-Lay Hens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2021, 30, 100115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, L.; Delezie, E.; Duchateau, L.; Goethals, K.; Tuyttens, F.A.M. Broiler Chickens Dead on Arrival: Associated Risk Factors and Welfare Indicators. Poult. Sci. 2017, 96, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, P. V; Kloeze, H.; Dam, A.; Ward, D.; Leung, N.; Brown, E.E.L.; Whiteman, A.; Chiappetta, M.E.; Hunter, D.B. Mass Depopulation of Laying Hens in Whole Barns with Liquid Carbon Dioxide: Evaluation of Welfare Impact. Poult. Sci. 2012, 91, 1558–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newberry, R.; Webster, A.; Lewis, N.; Arnam, C. Management of Spent Hens. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 1999, 2, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, A.B.; Collett, S.R. A Mobile Modified-Atmosphere Killing System for Small-Flock Depopulation. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2012, 21, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herborn, K.A.; Graves, J.L.; Jerem, P.; Evans, N.P.; Nager, R.; McCafferty, D.J.; McKeegan, D.E.F. Skin Temperature Reveals the Intensity of Acute Stress. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 152, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, S.S.; Alvarez, J.; Bicout, D.J.; Calistri, P.; Canali, E.; Drewe, J.A.; Garin-Bastuji, B.; Gonzales Rojas, J.L.; Gortázar Schmidt, C.; Herskin, M.; et al. Welfare of Domestic Birds and Rabbits Transported in Containers. EFSA J. 2022, 20, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 1/2005. 2005, 2001.

- Dawkins, M.S. The Science of Animal Suffering. Ethology 2008, 114, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doonan, G.; Benard, G.; Cormier, N. Livestock and Poultry Fitness for Transport--the Veterinarian’s Role. Can. Vet. J. = La Rev. Vet. Can. 2014, 55, 589–590. [Google Scholar]

- Weary, D.M. What Is Suffering in Animals? CABI 2014, 188–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockram, M.S. Fitness of Animals for Transport to Slaughter. Can. Vet. J. = La Rev. Vet. Can. 2019, 60, 423–429. [Google Scholar]

- Nalon, E.; Maes, D.; Piepers, S.; van Riet, M.M.J.; Janssens, G.P.J.; Millet, S.; Tuyttens, F.A.M. Mechanical Nociception Thresholds in Lame Sows: Evidence of Hyperalgesia as Measured by Two Different Methods. Vet. J. 2013, 198, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenka Valkova Vladimir Vecerek, E.V.M.K.D.T.; Brscic, M. Animal Welfare during Transport: Comparison of Mortality during Transport from Farm to Slaughter of Different Animal Species and Categories in the Czech Republic. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 21, 914–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union COUNCIL DIRECTIVE 2007/43/EC of 28 June 2007 Laying down Minimum Rules for the Protection of Chickens Kept for Meat Production. Off. J. Eur. Union 2007, 19–28.

- The Council of the European Union Council Directive 99/74/EC of 19 July 1999 Laying down Minimum Standards for the Protection of Laying Hens. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1999, 53–57.

- Hester, P.Y. Impact of Science and Management on the Welfare of Egg Laying Strains of Hens1. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasschaert, G.; De Zutter, L.; Herman, L.; Heyndrickx, M. Campylobacter Contamination of Broilers: The Role of Transport and Slaughterhouse. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 322, 108564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warriss, P.D.; Wilkins, L.J.; Brown, S.N.; Phillips, A.J.; Allen, V. Defaecation and Weight of the Gastrointestinal Tract Contents after Feed and Water Withdrawal in Broilers. Br. Poult. Sci. 2004, 45, 61–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Verma, A.K.; Umaraw, P.; Mehta, N.; Sazili, A.Q. 9 - Processing and Preparation of Slaughtered Poultry. In Postharvest and Postmortem Processing of Raw Food Materials; Jafari, S.M., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing, 2022. 281–314ISBN 978-0-12-818572-8.

- Gomes, H.A.; Vieira, S.L.; Reis, R.N.; Freitas, D.M.; Barros, R.; Furtado, F.V.F.; Silva, P.X. Body Weight, Carcass Yield, and Intestinal Contents of Broilers Having Sodium and Potassium Salts in the Drinking Water Twenty-Four Hours Before Processing. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2008, 17, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D.; Duncan, I.J. WellBeing International. 1998, 7, 383–396.

- Chauvin, C.; Hillion, S.; Balaine, L.; Michel, V.; Peraste, J.; Petetin, I.; Lupo, C.; Le Bouquin, S. Factors Associated with Mortality of Broilers during Transport to Slaughterhouse. Animal 2011, 5, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, V.A.; Ceballos, M.C.; Gregory, N.G.; Da Costa, M.J.R.P. Effect of Different Catching Practices during Manual Upright Handling on Broiler Welfare and Behavior. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 4282–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnár, A.; Maertens, L.; Ampe, B.; Buyse, J.; Kempen, I.; Zoons, J.; Delezie, E. Changes in Egg Quality Traits during the Last Phase of Production: Is There Potential for an Extended Laying Cycle? Br. Poult. Sci. 2016, 57, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, M.; Kettlewell, P. Chapter 30: Transport of Chicks, Pullets and Spent Hens. Welf. Lay. Hen. 2004, 361–374. [Google Scholar]

- Elkaoud, N.; Hassan, M. Maximize the Utilization of Traditional Cooling Units for Broiler Houses. Misr J. Agric. Eng. 2018, 35, 1515–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cockram, M.S.; Jung Dulal, K.; Stryhn, H.; Revie, C.W. Rearing and Handling Injuries in Broiler Chickens and Risk Factors for Wing Injuries during Loading. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 100, 402–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langkabel, N.; Baumann, M.P.O.; Feiler, A.; Sanguankiat, A.; Fries, R. Influence of Two Catching Methods on the Occurrence of Lesions in Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 1735–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayliss, P.A.; Hinton, M.H. Transportation of Broilers with Special Reference to Mortality Rates. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1990, 28, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kettlewell, P.J.; Turner, M.J.B. A Review of Broiler Chicken Catching and Transport Systems. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 1985, 31, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knierim, U.; Gocke, A. Effect of Catching Broilers by Hand or Machine on Rates of Injuries and Dead-On-Arrivals. Anim. Welf. 2003, 12, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijdam, E.; Delezie, E.; Lambooij, E.; Nabuurs, M.J.A.; Decuypere, E.; Stegeman, J.A. Comparison of Bruises and Mortality, Stress Parameters, and Meat Quality in Manually and Mechanically Caught Broilers. Poult. Sci. 2005, 84, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mönch, J.; Rauch, E.; Hartmannsgruber, S.; Erhard, M.; Wolff, I.; Schmidt, P.; Schug, A.R.; Louton, H. The Welfare Impacts of Mechanical and Manual Broiler Catching and of Circumstances at Loading under Field Conditions. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 5233–5251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ekstrand, C. An Observational Cohort Study of the Effects of Catching Method on Carcase Rejection Rates in Broilers. Anim. Welf. 1998, 7, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broom, D.; Knowles, T.G. The Assessment of Welfare during the Handling and Transport of Spent Hens.; 1989.

- Elson, A. The Laying Hen: Systems of Egg Production. CABI 2004, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicol, C.J.; Scott, G.B. Pre-Slaughter Handling and Transport of Broiler Chickens. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1990, 28, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watteyn, A.; Van Noten, N.; Tuyttens, F. Ontwikkeling van Een Onmiddellijk Implementeerbaar Monitoringssysteem Voor Het Meten van Het Welzijn van Legkippen Aan de Slachtlijn. 2023, 90748.

- Rapport, L. 2024_Landbouw Rapport_Agentschap Landbouw En Zeevisserij_rapport. 2024.

- Martin, J.E.; Sandercock, D.A.; Sandilands, V.; Sparrey, J.; Baker, L.; Sparks, N.H.C.; McKeegan, D.E.F. Welfare Risks of Repeated Application of On-Farm Killing Methods for Poultry. Anim. an open access J. from MDPI 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodenburg, T.B.; Komen, H.; Ellen, E.D.; Uitdehaag, K.A.; van Arendonk, J.A.M. Selection Method and Early-Life History Affect Behavioural Development, Feather Pecking and Cannibalism in Laying Hens: A Review. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 110, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodenburg, T.B.; Tuyttens, F.A.M.; de Reu, K.; Herman, L.; Zoons, J.; Sonck, B. Welfare Assessment of Laying Hens in Furnished Cages and Non-Cage Systems: Assimilating Expert Opinion. Anim. Welf. 2008, 17, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HSA - Humane slaughter association Poultry Catching and Handling Summary. Tech. Note No 15 2018, 1–8.

- Knowles, T.G.; Wilkins, L.J. The Problem of Broken Bones during the Handling of Laying Hens–a Review. Poult. Sci. 1998, 77, 1798–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belplume Lastenboek. 2021.

- Prayitno, D.S.; Phillips, C.J.; Omed, H. The Effects of Color of Lighting on the Behavior and Production of Meat Chickens. Poult. Sci. 1997, 76, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerpe, C.; Toscano, M.J. Solutions to Improve the Catching, Handling, and Crating as Part of the Depopulation Process of End of Lay Hens. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2023, 32, 100358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, F.M.; Garcia, R.G.; Binotto, E.; Burbarelli, M.F. de C. What Do We Know about the Impacts of Poultry Catching? Worlds. Poult. Sci. J. 2021, 77, 983–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, C.A. Poultry Handling and Transport. Livest. Handl. Transp. Fourth Ed. 2014, 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross Broiler Management Handbook. Aviagen Ross Manag. Guid. 2018, 1–147.

- Cransberg, P.H.; Hemsworth, P.H.; Coleman, G.J. Human Factors Affecting the Behaviour and Productivity of Commercial Broiler Chickens. Br. Poult. Sci. 2000, 41, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandin, T. The Effect of Economic Factors on the Welfare of Livestock and Poultry. Improv. Anim. Welf. A Pract. Approach 2nd Ed. 2015, 278–290. [Google Scholar]

- Pilecco, M.; Almeida, I.; Tabaldi, L.; Naas, I.; Garcia, R.; Caldara, F.; Francisco, N. Training of Catching Teams and of Back Scratches in Broilers. Brazilian J. Poult. Sci. 2013, v.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weeks, C.A. Poultry Handling and Transport. CABI 2014, 378–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Committee, A.W.; House, N. Opinion on the Welfare Implications of Different Methods and Systems for the Catching , Carrying , Collecting and Loading of Poultry. 2023.

- Delanglez, F.; Watteyn, A.; Ampe, B.; Segers, V.; Garmyn, A.; Delezie, E.; Sleeckx, N.; Kempen, I.; Demaître, N.; Van Meirhaeghe, H.; et al. Upright versus Inverted Catching and Crating End-of-Lay Hens: A Trade-off between Animal Welfare, Ergonomic and Financial Concerns. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, G.; Mench, J.A. Influence of Different Handling Methods and Crating Periods on Plasma Corticosterone Concentrations in Broilers. Br. Poult. Sci. 1996, 37, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kittelsen, K.E.; Granquist, E.G.; Aunsmo, A.L.; Moe, R.O.; Tolo, E. An Evaluation of Two Different Broiler Catching Methods. Anim. an open access J. from MDPI 2018, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chloupek, P.; Bedanova, I.; Chloupek, J.; Vecerek, V. Changes in Selected Biochemical Indices Resulting from Various Pre-Sampling Handling Techniques in Broilers. Acta Vet. Scand. 2011, 53, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacy, M.P.; Czarick, M. Mechanical Harvesting of Broilers. Poult. Sci. 1998, 77, 1794–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, G.B.; Moran, P. Fear Levels in Laying Hens Carried by Hand and by Mechanical Conveyors. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1993, 36, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, F.A.A.; Lashin, A.I. Influence of Handling Processes for Broilers on Mortality and Carcass Quality At Slaughterhouse. Misr J. Agric. Eng. 2017, 34, 1923–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musilová, A.; Kadlčáková, V.; Lichovníková, M. The Effect of Broiler Catching Method on Quality of Carcasses. Mendel Net 2013, 2013, 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Hoorweg, F.A.; Riel, J.W. Van; Gerritzen, M.A. Vang- En Ketenletsel Bij Vleeskuikens Op Verschillende Momenten in de Keten. 2024.

- Löhren, U. Overview on Current Practices of Poultry Slaughtering and Poultry Meat Inspection. EFSA Support. Publ. 2017, 9, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Laying hen farmers | Broiler chicken farmers |

|---|---|---|

|

Age (%) <18 – 25 years 25 - 35 years 35 - 45 years 45 - 55 years 55 - 65 years > 65 years |

n=80 | n=133 |

|

0 (n=0) |

2 (n=2) |

|

| 8 (n=6) 14 (n=11) 25 (n=20) 50 (n=40) 3 (n=3) |

17 (n=22) 14 (n=19) 35 (n=46) 32 (n=42) 2 (n=2) |

|

|

Gender (%) Male Female X |

n=80 | n=132 |

|

79 (n=63) 21 (n=17) 0 (n=0) |

80 (n=106) 20 (n=26) 0 (n=0) |

|

|

Highest education level (%) Secondary degree High school degree University degree |

n=74 | n=131 |

|

70 (n=52) |

68 (n=89) |

|

| 20 (n=15) | 25 (n=33) | |

| 10 (n=7) | 7 (n=9) | |

|

Location of farms (Flemish provinces) (%) Antwerp Limburg East-Flanders Flemish Brabant West-Flanders |

n=80 | n=134 |

|

39 (n=31) 19 (n=15) 10 (n=8) 1 (n=1) 31 (n=25) |

37 (n=49) 11 (n=15) 16 (n=21) 2 (n=3) 34 (n=46) |

|

|

Housing system (%) Aviary Cage Ground |

n=57 42 (n=24) 37 (n=21) 12 (n=12) |

NA |

|

Breed (%) Lohman Isa Brown Dekalb White Nova Brown Bovan Brown Roman Classic Ross 308 Sasso Hubbart |

n=57 26 (n=15) 26 (n=15) 18 (n=10) 12 (n=7) 14 (n=8) 4 (n=2) NA NA NA |

n=110 NA NA NA NA NA NA 95 (n=104) 2 (n=2) 3 (n=4) |

|

# of chickens in stable (%) < 10,000 10,000 – 20,000 20,001 – 30,000 30,001 – 40,000 > 40,000 |

n=57 23 (n=13) 33 (n=19) 28 (n=16) 7 (n=4) 9 (n=5) |

n=110 10 (n=11) 41 (n=45) 25 (n=27) 15 (n=16) 10 (n=11) |

| Selection | Laying hen farmers | Broiler chicken farmers | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Performer (% of respondents) Farmer Farm staff Company veterinarian No one |

n=66 | n=103 | |

|

79x |

90x |

0.04 |

|

| 14y 0xy 21 |

4z 15y 29 |

0.03 0.10 NA |

|

|

Reasons (% of respondents) Stunted growth Leg problems/lame birds Feather pecking (victim) E. coli Huddled chickens |

n=44 | n=86 | |

|

14y 57x 43x 32yz 18yz |

71x 85x 3y 26z 13yz |

<0.001 <0.001 <0.001 0.45 0.41 |

|

|

Bottlenecks (% of respondents) Financial Time Insufficient knowledge |

n=66 | n=103 | |

|

15y |

47x |

<0.001 |

|

| 33x | 35x | 0.83 | |

| 8y | 7y | 0.85 | |

|

Advantages (% of respondents) Animal welfare Uniformity of the animals Preventing of disease Less feed waste |

n=66 | n=103 | |

|

55x 29y 49xy 30y |

74x 66x 63xy 47y |

0.01 <0.001 0.06 0.04 |

|

| Significant P-values (P < 0.05) between laying hen and broiler chicken farmers are indicated in bold and P-values between 0.05 and 0.10 are underlined. Superscripts (x,y,z) indicate pairwise significant differences within the column. | |||

| Catching and loading | Laying hen farmers | Broiler chicken farmers |

|---|---|---|

|

Lighting schedules (% of respondents) Completely dark Dimming lights No change |

n= 35 | n=60 |

|

66 (n=23) |

50 (n=30) |

|

| 26 (n=9) 9 (n=3) |

50 (n=30) 0 (n=0) |

|

|

Start time (% of respondents) 0 – 2 a.m. 3 – 5 a.m. 6 – 8 a.m. 9 – 12 a.m. 1 – 3 p.m. 4 – 5 p.m. 6 – 8 p.m. 9 – 12 p.m. |

n=42 | n=65 |

|

0 0 0 0 0 0 62 (n=26) 38 (n=16) |

17 (n=11) 25 (n=16 26 (n=17) 2 (n=1) 0 0 3 (n=2) 28 (n=18) |

|

|

End time (% of respondents) 0 – 2 a.m. 3 – 5 a.m. 6 – 8 a.m. 9 – 12 a.m. 1 – 3 p.m. 4 – 5 p.m. 6 – 8 p.m. 9 – 12 p.m. |

n=42 | n=65 |

|

55 (n=23) |

12 (n=8) |

|

| 19 (n=8) | 9 (n=6) | |

| 2 (n=1) 0 0 0 0 24 (n=10) |

28 (n=18) 37 (n=24) 3 (n=2) 6 (n=4) 0 5 (n=3) |

|

|

# of chickens per catch (% of respondents) 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 12 |

n=42 | n=65 |

|

17 (n=7) 0 33 (n=14) 12 (n=5) 29 (n=12) 0 5 (n=2) 2 (n=1) 2 (n=1) 0 |

0 0 25 (n=16) 60 (n=39) 9 (n=6) 2 (n=1) 2 (n=1) 0 2 (n=1) 2 (n=1) |

|

|

Presence of poultry farmer (% of respondents) Start End Whole process |

n=43 5 (n=2) 2 (n=1) 93 (n=10) |

n=65 9 (n=6) 0 91 (n=59) |

|

Task Poultry farmer (% of respondents) Supervision Instructions Catching |

n=42 72 (n=31) 30 (n=13) 12 (n=5) |

n=65 77 (n=50) 23 (n=15) 18 (n=12) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).