1. Introduction

It is known that the fecundity of women decreases gradually over the years. The decrease starts at the age of 32 and rapidly changes after the age of 37 [

1]. An ever-increasing number of women choose to delay childbearing for various reasons. Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) has evolved with time due to that always increasing need to preserve female fertility. ICSI, oocyte, sperm and embryo cryopreservation and In-Vitro Fertilization (IVF) list the different ART methods. ART has been around for over 40 years providing both physicians and patients ever evolving techniques. Embryo and sperm cryopreservation are already widely considered ART effective techniques. Oocyte cryopreservation nowadays tends to be more in the spotlight. Due to its improved techniques regarding safety and efficiency, both the Practice Committees of the American Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology and the ESHRE Task Force on Ethics and Law do not consider oocyte cryopreservation to be experimental anymore [

2,

3]. As a result, it is already considered the method of choice for preserving female fertility not only by women who face medical problems and conditions but also by women who are considered physically healthy. Thus, providing the opportunity for these women to have a biological offspring and become mothers while avoiding making neither haste nor important decisions right on the spot [

4].

The use of said method for non-medical reasons raises various ethical, social, economic and legal questions. The purpose of this paper is to review the various social reasons that may or may not interfere with women’s decision-making concerning egg freezing collected from articles.

1.1. Brief History Report

Fertility has always been at the center of worshiped rituals by all kinds of different cultures throughout the existence of mankind since ancient times all over the world. Museums all over the world present artifacts such as little or big stone statues, paintings and various types of metallic creations dedicated to deities associated with the stimulation of production either in humans or in the natural world. Africans, ancient Egyptians, Incas, Inuits, Aztecs, Mayans, Chinese, Indians, Celtics, Germanics, ancient Greeks, Romans, Slavics and Indigenous Australians are but a few of the well-studied civilizations that had their own list of fertility gods and goddesses to pray to. Furthermore, when Ancient Greek physicians were facing reproductive failure in married couples, procreative disruption took place and thus “infertility” was noted. If after a long list of medical either liquid or surgical remedies the problem of childlessness remained, there were gods upon who ancient Greeks would pray to resolve the problem [

5]. Therefore, fertility in both the human and the natural world and its celebration goes back centuries and has a long history.

1.2. Definition of ART [6]

Assisted reproductive technologies (ART) by the American Center for Disease Control (CDC) are fertility- related treatments that help in achieving pregnancy conception in individuals who are having difficulty doing so spontaneously. They are procedures during which oocytes or embryos are manipulated. Any procedure that involves sperm manipulation is not included in this definition. Procedures that involve ovarian stimulation without retrieving an egg in the end, are also excluded from said definition. In vitro fertilization (IVF) is by far the most common ART procedure preferred alongside cryopreservation and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

1.3. Definition of Cryopreservation

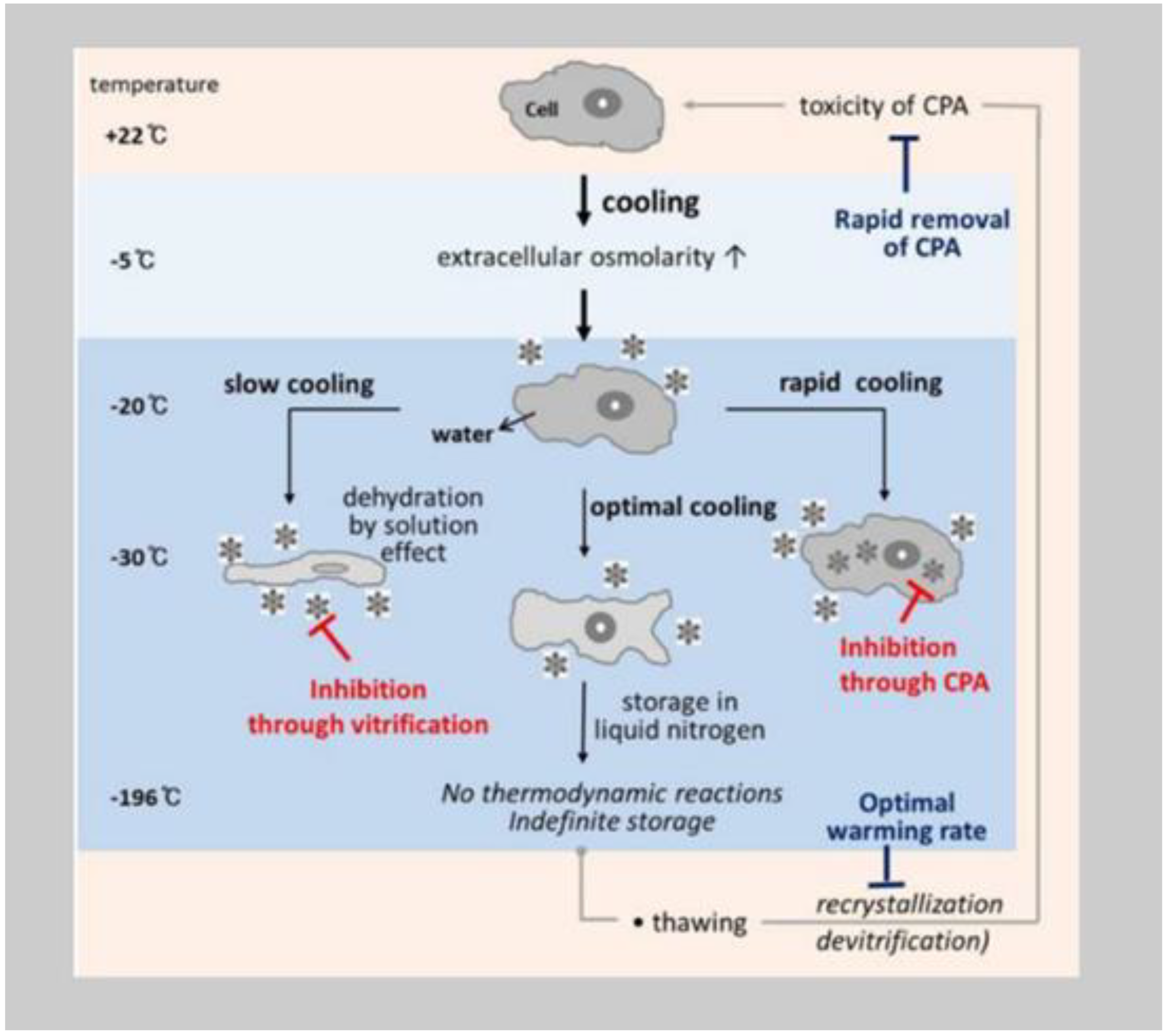

Cryopreservation is the technique during which any type of biological construct is preserved for any amount of time, by being cooled at a very low temperature [

7]. Physically there is water inside the cells and there is water surrounding them. So, when we try to freeze living cells or tissue, we submerge the sample in an extremely cold liquid, resulting in ice formation both inside the cell and in its surrounding environment. Causing changes in the cellular structure and then its damage. The obstacle of cells of water to ice transition, is what the cryoprotective agents are here to help them overcome. These liquids were developed to minimize the ice formation both inside and outside of the cells at no matter how low the temperatures would be.

The following figure demonstrates the events of cellular cryoinjury (

Figure 1).

1.4. IVF and Cryopreservation Law

Assisted reproductive techniques have had their definition originally established by the Greek law in the late 1999 with surrogacy being the first term to be legislated. Heterosexual couples that were trying to have a child outside of wedlock, had a lot of legal things to deal with. Mutual consent and recognition of the offspring were being individualized at every case due to at that time insufficient Greek legislation. The Greek legal framework concerning assisted reproduction was originally established in 2002 and it regulated kinship and inheritance rights for the children that were born with the help of assisted reproduction. According to article 1455 of the Greek law 3089/2002, assisted reproduction was only allowed in case a couple dealt with infertility or they were trying to avoid passing on to the child some kind of serious illness. The couple didn’t have the right to predetermine the sex of the baby unless a severe sex related inheritable disease was at stake. It had also been regulated by the same law, the transfer of fertilized eggs without compensation.

After only 3 years, a new legal framework was established. Even though assisted reproduction methods were increasingly wildly spreading in the private medical community, there hadn’t been a clarification neither for the exact assisted reproduction techniques that were being performed nor for the proper operation of private assisted reproduction clinics nor the cryopreservation banks. Women’s age limit for undergoing assisted reproduction was set to be their 50th year and the time allowed to cryopreserve semen and testicular tissue, embryos, unfertilized oocytes and ovarian tissue was for 10 years, 5 years (with a 5-year time extension) and 5 years accordingly. Penalties for failure to comply with the conditions set by the law, were also regulated. That newly established law still stands to this day with some alterations. According to the recent Greek legislation 4958/2022, the women’s age limit for undergoing assisted reproduction was reformed to 54 years. In addition, the law states that gametes or embryo cryopreservation apply for both therapeutic and fertility preservation purposes. In any case of gamete or embryo cryopreservation, the time of extensions has set to be indefinite [

8].

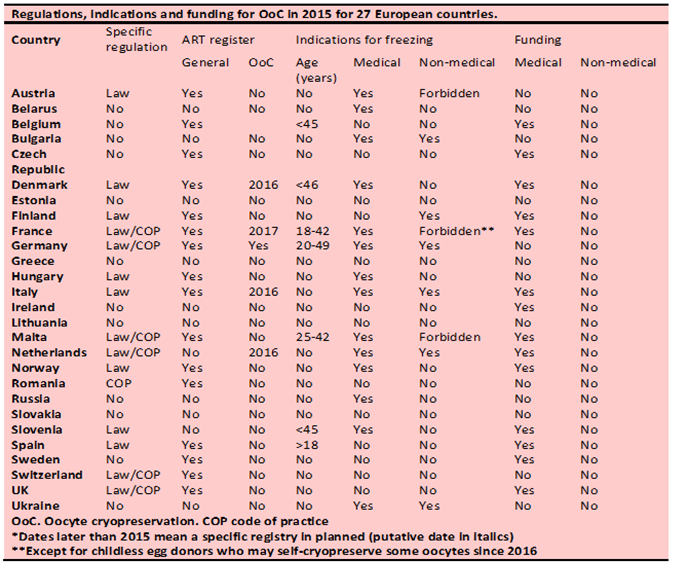

According to the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology [

9] and its following table (

Table 1), legal legislation regarding oocyte cryopreservation varies across the countries in Europe. In 2017 some of the European countries had a specific regulation concerning oocyte cryopreservation whereas none of that resulted in any kind of funding or even partial refund for social egg freezers. 14 out of 27 countries, allow egg freezing when there is a pre-existing medical reason whereas in Austria, France and Malta social egg freezing is forbidden. The rest of the countries in Europe continue to practice oocyte freezing regardless of the lack of a specific legal regime. Estonia and Lithuania are the only 2 European countries that have no regulations, no indications and no funding for oocyte cryopreservation, while Ireland funds women who undergo egg freezing for medical reasons. Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece (according to the newly reformed law), Malta and Slovenia have set a time limit to allow women to cryopreserve their eggs, whereas Spain just requires from women to be adults.

1.4.1. Cryopreservation Law in Asia

According to the current Chinese regulations, specific groups of people that don’t meet the criteria about national population and family planning, aren’t allowed to be artificially reproductively assisted [

10]. These groups include single or unmarried women, unmarried couples, homosexuals, transgender people as well as people performing high-risk occupations [

11]. Although only Chinese Jilin province may has made a regulative exception about ART concerning the previously mentioned groups, local physicians support that said exception has never been put into practice because the local hospitals don’t want to go against the national health authority [

12]. In Japan [

13], women with pre-existing pathological reasons affecting future fertility are allowed to undergo oocyte or oocyte tissue cryopreservation only after they are appropriately and rightfully informed about the procedure and its possible affects. Women who wish to avoid age related infertility are also legally allowed to take refuge in cryopreserving their eggs according to the Japanese Ethics Committee of Reproductive Medicine. According to the Russian federal laws [

14], every woman eligible for childbearing has the right to access any ART. Although up until recently, Russian clinics would refuse to treat single men or women to surrogacy via artificial fertilization, due to the issues that would arise for the children that would be born from surrogacy to a single parent family, thanks to new Russian law, that has started to shift. There have been several cases of single parents (regardless of their sex) that were registered by Russian courts as the single parent to their adoptive child (via surrogacy) proving that even though Russia could be considered a reproductive paradise due to its low ART practice costs, the one thing that hasn’t changed through time is that the only indications for women to seek help in ART that are justified by the Russian law, are the medical ones.

1.4.2. Cryopreservation Law in USA, Australia, Canada and UK

In the USA [

15], legal framework about ART and egg cryopreservation is a little different than that of the rest of the world. Sperm, egg and embryo cryopreservation are under the protection of US federal laws and single and married women are allowed to hire surrogate parents. Unfortunately, any other regulations, including that of embryo disposal, are set by each case and court in individual states. We come across similar constitutional laws both in Australia and Canada as well [

16]. There is a basic legal framework that embodies ART and surrogacy, but every case is different, and every state can regulate its own legal regime. Women who have been declared infertile or have a higher chance of having a child with a hereditary disease (married, single or lesbian) have the right to access any form of ART. Little is classified though about single women trying to undergo egg cryopreservation to avoid age-related infertility, same-sex couples and transgender people when resulting in any form of ART.

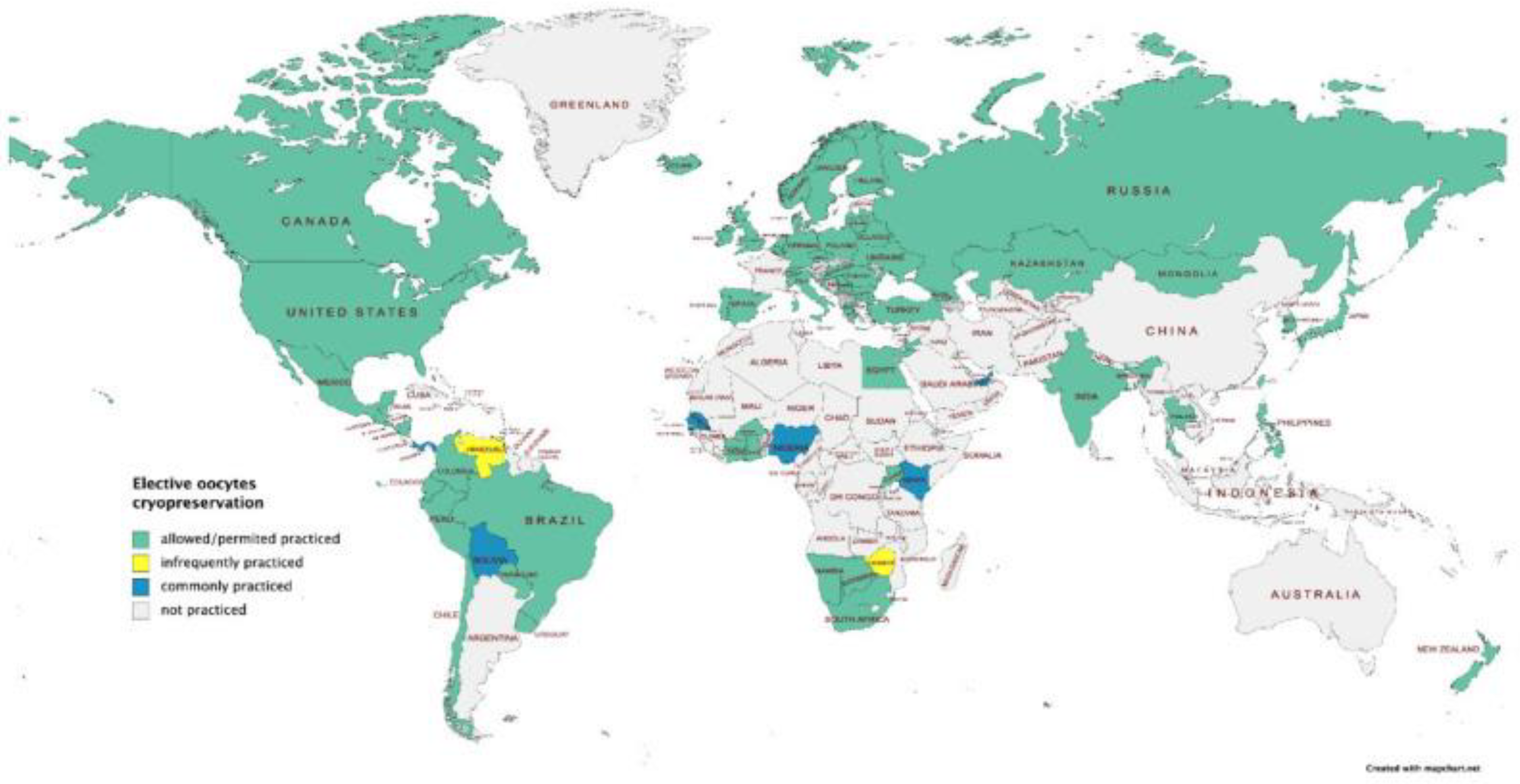

According to Varlas et al. and their paper in 2021, the following image depicts in which countries Selective Egg Freezing (SEF) is permitted or practiced (countries with the green color), in which countries is a common practice (blue depicted countries), in which isn’t a common practice (yellow depicted countries) while in grey are depicted countries that SEF isn’t practiced at all (

Figure 2).

1.5. IVF and ICSI

In vitro fertilization (IVF) is a method during which both sperm and eggs are added together in a dish to be fertilized whereas ICSI involves injecting a single sperm in a single egg [

18]. ICSI is highly effective when dealing with male factor infertility [

18] and are current various indications for ICSI that are widely adopted, rendering it the most popular insemination method worldwide [

19]. In both methods, when those embryos are successfully fertilized and matured, either they are inserted in the women undergoing the infertility treatment right away or they are cryopreserved, and a new later date will be set for the embryo implantation.

1.6. Cryopreservation techniques

Cryopreservation involves the preservation of cells and tissue for long periods of time at sub-zero temperatures. Oocyte cryopreservation is an established and widely used treatment for women who are willing to postpone child- bearing. As a procedure, oocyte cryopreservation involves ovarian hormonal stimulation, oocyte retrieval, freezing and oocyte storage [

20]. Cryoprotective additives (CPAs) are used to reduce cryodamage by preventing ice formation. There are two basic techniques applied to the cryopreservation of human oocytes: controlled slow freezing, which was more commonly used in the early years and ultrarapid cooling by vitrification which is more commonly used nowadays. Slow freezing results in a liquid changing to a solid state whereas vitrification result in a non- crystalline amorphous solid [

21]. According to Argyle et al. in a systematic review they did in 2016, vitrification is the cryopreservation technique of choice [

21]. Embryos can also be cryopreserved and are widely used in IVF treatments but that requires legal ownership between both partners, which is more complex and leads to further difficulties. The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology states for example, if a couple has cryopreserved their embryos but they end up splitting prior to the IVF treatment, the person willing to become pregnant can’t do so if their partner has retracted their consent [

22].

1.6.1. Optimal timing of cryopreservation

It is well known that the success rates of IVF cycles using cryopreserved oocytes decline rapidly as the age of women increases [

23]. The optimal timing for women to freeze their eggs, with a much higher success rate, is under 35 years according to systematic studies from both Alteri et al. and Varlas et al. [

24,

25]. Cryopreserving eggs at an earlier age can minimize the number of cycles necessary to obtain sufficient eggs and maximize egg quality, with the risk of never using them [

25]. In women aged ≤35 years, the cumulative live birth rate (CLBR), considering the total number of oocytes used in consecutive procedures, was significantly higher compared with those aged >36 years, despite the same number of oocytes being utilized [

24,

26]. Another survey by Doyle et al. came to a similar conclusion that to achieve the highest probability of live birth rate from cryopreserved oocytes, these oocytes should have been retrieved prior the age of 36-38 years [

27]. Unfortunately, most women undergo treatment after a significant decline in fertility. Indeed, studies based on surveys, showed that the average age to cryopreserve oocytes is between 36 and 38 years [

24].

1.6.2. The optimal number of oocytes

The number of oocytes retrieved should be individualized according to each patient’s age, ovarian reserve and clinical circumstances. Different studies about fertility preservation from all over the world lead up to the same conclusion, that the better the quality of the oocyte used, the higher the success rate of a healthy pregnancy outcome and a viable genetically related offspring. According to Doyle’s et al. study, women between 35 and 38 years of age with 20 cryopreserved oocytes would have live birth rates of 80% and 60% respectively [

27]. Whereas Cobo et al. concluded that pregnancy rates are age-dependent and a minimum of 8-10 oocytes need to be retrieved to achieve pregnancy [

28]. Cryopreserving a small number of oocytes can lead to low success pregnancy rates.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Purpose of This Paper

The purpose of this paper is to review the reasons women of reproductive age, free from pathological medical conditions, would turn to cryopreserving their oocytes to prolong fertility and postpone pregnancy.

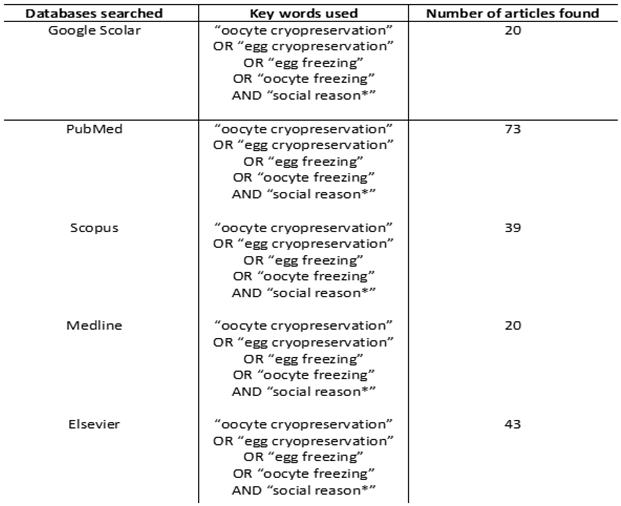

2.2. Methods

Online search of databases was performed in Google Scolar (1980- 2023), PubMed (1980- 2023), Scopus (1980- 2023), Medline (1980-2023) and Elsevier (1980-2023). The combination of words that was used for citations was for oocyte cryopreservation (“oocyte cryopreservation”, “oocyte freezing”, “egg freezing” or “egg cryopreservation”) and social reasons (“social reason*”). To generate final citations on all databases ‘AND’ was used between oocyte cryopreservation and social reasons. The filter for citations regarding human studies was also set. Language restrictions were used on the search so that only English published articles could be included. Exclusion criteria were citations that either would provide only the abstract or there was no free way to access their results. Citations that were also not included in this paper were studies that oocyte cryopreservation was the only fertility preservation option due to any form of preexisting pathological or oncological condition (

Table 2).

3. Results

3.1. Social Reasons Lead Women to Egg Cryopreservation and Women’s Attitude Regarding ART

Oocyte cryopreservation has technologically improved in the last 30 years that it is no longer considered only as a fertility treatment for cancer patients of for women with severe medical conditions, but also as a solution for women dealing with age -related fertility loss. Oocyte cryopreservation or egg freezing for non- medical reasons, is increasing and has replaced at a certain point embryo cryopreservation, according to ESHRE, in order women without a male partner to preserve their fertility. Women undergoing egg cryopreservation are usually healthy and they don’t have a pre-existing medical condition that would endanger their ability to become mothers in the future. So, the motivations, in this case, are a little different [

29]. A recent Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) Scientific Opinion piece on the topic stated that elective egg freezing for non-medical reasons provides an opportunity for women to mitigate the decline in their fertility with age but highlight that women undertaking oocyte cryopreservation should only do so with a full understanding of the likelihood of success [

20]. Various studies worldwide have investigated the knowledge, the attitude and the awareness women have concerning fertility decline and egg freezing. They all conclude that women need to be better and fully informed about the optimal time of having a child as well as that further investigation is needed about the always evolving reproductive technological advancements [

30,

31,

32].

3.1.1. Lack of Partner

In the Netherlands [

33], during a study, when women were questioned about their motivations as to why they were trying egg freezing, two reasons came up most often. Rapid fertility decline and lack of a male partner. When women felt the pressure of time on starting a family and realized that their fecundity was deteriorating, it was realized that the only way to fulfil the desire of having a baby was with the medical aid of egg cryopreservation. The constant stress of a medical ‘timetable’ led to various psychological issues. Some women even experienced health problems such as depression and fatigue due to the constant denial of either a partnerless or a childless future. Thus, it was considered by women, discussing future family plans with relatives and friends, an inappropriate matter [

33]. When women talked about cryopreserving their eggs, a sense of ‘breathing space’ was created. When those women would consider their eggs “being in the freezer”, an idea of insurance was revived, and a weight was lifted off from their shoulders. Even thought it was understood that their frozen eggs were not a guarantee of a future living offspring, it was believed that an effort should be made to achieve that. Not taking any action most often would lead to regret. Hope about the future and a peace of mind were the results of ‘the backup plan’ [

33].

When women were questioned about their future family ‘picture’, the most significant aspect was a same-minded partner and a stable relationship. It was vital for women for the family to consist of a father and a mother raising a genetically related to it child. For the child to bare similar physical characteristics passed on from its parent’s genes, was something women wished for. Women coming from all types of family backgrounds (either small or big families) realize the importance of family. Even women that might have had doubts about having children, would prefer to have a time limit when starting to create a family. Even though most women would prefer, when asked, to have a baby in the “natural” way, when time started to pass they too started to consider alternative options and ways of becoming mothers. Other ways were single motherhood or even having children and co-parenting with male homosexual couples. There were also women who expressed their doubts about taking on single motherhood due to the excess financial responsibility they would have to take. Some women would also give up the ideal look of a family and ended up considering adoption or fostering children as well [

33].

A study conducted in Spain [

32] resulted also in more than 70% of single women’s motivation for undergoing IVF/ICSI and more than 60% that electively froze their egg was in both cases, the lack of partner. An interesting finding in the study, was that women who underwent IVF/ICSI perceived a stronger family support than women undergoing SEF. Another conclusion of the study was that all women who underwent SEF knew the possibility of needing a sperm donor, whereas only 59,9% of women undergoing IVF/ICSI were informed about SEF. The results of said study, in contradiction with the one conducted in the Netherlands [

33], showed the importance of family ties during women’s decision making when and if starting IVF/ICSI as single women and the misinformation of women about SEF as an established method of delayed motherhood.

Jones et al. study [

34] in the UK came to similar conclusion that 70% of women resulting in freezing their eggs were influenced by the lack of a partner. In a retrospective analysis in the UK [

35] that proceeded Jones’s study [

34], it was also noted, that women’s motivations for undergoing egg freezing in the first place was also the lack of a male partner. The British analysis resulted in the singleness of all women, who underwent egg freezing, when returned to use their originally frozen eggs.

In Belgium [

36] Pennings in 2021, wanted to look deeper into to the actual reason for lack of partners for highly educated women and he concluded that women were concerned about “marrying down” if they chose a partner with a lower degree in education. For decades, it was stereotypically expected by people that the major role a person had to play was that of a parent. Through marriage, heterosexual couples were expected to have biologically related to them children while the male, because of it’s higher than his partner education, would earn more and he would be the breadwinner and the woman would be the homemaker. But after decades of constant efforts, the number of women trying and achieving tertiary education has increased. Thus, leading to an inevitable gender inequality. Relationships were created where both male and female counterparts felt that they were being wronged. Some men were intimidated by the fact that their partners had either a higher degree in education than them or they were earning more, or sometimes even both. Whereas women had to put up with a lot of pressure all these years when dealing with the economic and educational advantage of men, that now it’s hard for them to settle for something less. Hence, the reversed gender mismatch was cultivated. The egg freezing has resulted in some sort of reproductive autonomy for women but the problem of social imbalance between the two genders remains. Although the ever-advancing technology has procured as with more safety for both sexes and their gametes, Pennings resulted in the irreversibility of the gender education gap.

3.1.2. Education and Career advancement

Among the reasons women are considering delaying childbearing for, are also education and career prioritization [

37]. It is a noticeable worldwide fact that women have been trying to extend their knowledge and ascend in the workplace. When female residents in the USA [

38] were questioned about the reasons leading to postponing pregnancy, residency was considered of vital importance by more than 70%. Both career plans and future childcare were considered important reasons by more than 50% of the female residents, to delay creating a family too. SEF being very attractive to people with a higher education was also confirmed in Schick’s study [

39]. More participants in said German study with a university degree, understood the use of SEF due to the unwillingness of balancing both a career and a family.

3.1.3. Financial Instability and SEF

When women were questioned about the financial journey they would take upon when cryopreserving their eggs, concluded to the fact that said reproductive technique should be offered to everybody, regardless of their income. It is considered by many women that if SEF was to be more widely financially accessible, more women would be given the opportunity to plan their future regarding childbearing [

40]. Women also noted the aid of their drastic income increase, led to easier access to egg freezing. The discrimination between women who can afford to pay to have their eggs frozen and those who can’t, was inevitable. There is also another issue that was unveiled. When women were informed that either homosexual couples or heterosexual couples battling with long-life infertility would receive financial coverage, felt discriminated upon. The idea of creating same opportunities for all, remained. But having single mothers bare the financial burden on their own was deemed unfair. That led to a suggestion that cryopreservation expenses be covered by either healthcare insurances or the state [

33,

41]. Partial compensation was also considered a viable option by many [

33].

The economic burden of SEF isn’t only in the mind of people undergoing it, but it is also a worldwide concern. Both international company employers [

42] and bioethicists [

43,

44] have been in a constant battle as to whether full or even a partial coverage for SEF should be offered and by whom. There is an ongoing question as to who deserves to be compensated for SEF procedures, why and how much is the right amount of compensation. Every woman that decides to go down that path, has different characteristics and needs. There are women who have already had a pre-existing medical condition that prevented them from getting pregnant naturally on their own. Older women whose fertility is declining rapidly. Women who are simply lacking a male partner. Women who choose to postpone childbearing for some time. So, the need for compensation should be differentiated in every single case. Egg cryopreservation and its individual procedures (ovarian stimulation, oocyte retrieval, cryopreservation, storage and later if necessary, thawing and fertilization) are considered a well-established method today to countereffect infertility. In most countries infertility treatments are financially covered by the public healthcare system. So, the logical thing would be for each country’s public healthcare system to cover any expenses on SEF. But the reality is far from that. Private fertility clinics offer their services, so most women and couples end up covering their own expenses with no refund at all.

On the one hand, according to bioethicists [

44,

45], corporates attempting to entice people and benefit their employees with infertility procedures coverage contracts, was perceived poorly. Companies were suggested to find other ways to show their family friendly policies. Increased benefits, longer maternal and/or paternal work leave or even assistance with day care were some of the new policies that were suggested. On the other hand, other bioethicists [

46] argued with the belief that company sponsored egg freezing was limiting women’s autonomous choice about family making. Under well informed and specific conditions, company policy guidelines and no pressure, women should ensure their autonomous choices about the time they would choose to start their family. It was also pointed out that if any woman felt the need to comply with their employer’s dictations no matter their own personal beliefs and wishes, that this was no different than any other type of pressure the labor market would put on them that would be more easily accepted.

3.2. Women’s attitude on SEF

A recent study in Italy by Tozzo et al. asked 930 female students of the Padova University about their understanding and attitude towards social egg freezing [

47]. Data collected in this study revealed some important points about young women and their knowledge about social oocyte freezing in Italy as compared to other European countries and the United States. Overall, 34.3% of the students reported having heard about the possibility of oocyte cryopreservation for non-medical reasons and being aware of the meaning of this procedure; only 19.5% were in favor of social egg freezing and 48.4% thought that the cost for this procedure should be borne entirely by the woman herself. The study showed that young Italian women are significantly less aware of age-related decline in fertility and the possibility of using social egg freezing compared to their similarly situated counterparts in other Western countries.

In Austria [

48], when women were asked about their opinions and viewpoints concerning egg-freezing, interesting results were identified. Although Austria being one of the countries in Europe that egg-freezing is not allowed neither for medical nor for social reasons and even though women believe that having a child is not just a ‘right’, it was highly perceived that women should be able to decide for themselves regardless of the different types of policy interventions. In addition, when women were questioned about the technological advancements that nowadays can provide women with the option of egg freezing, showed clear favor of restrictions to such reproductive technologies and a tendency to create better policies in the labor market to enhance work- life. Austrian women while may consider egg freezing to be a real option, are not in favor of regulatory interventions (neither by companies, employers nor the state itself) when they decide to have a baby and suggest that every woman should ask herself, prior to starting a family, what is the real reason she is doing that and who is she truly doing that for.

Stoop et al. [

49] when they researched the opinion and attitude of women of reproductive age about egg freezing resulted in conflicting views. When more than 31% of respondents would consider themselves potential elective egg freezers, a 51.8% would not consider it. In addition, more than 16% of women had no comment on the matter. The results of Schick’s study that took place in Germany [

50], add to and confirm the prementioned existing data. Even though more than 1/3 of the sample of the German study had a positive attitude towards SEF, more than half of the people were opposed to it. The use of SEF for preexisting pathological conditions is highly valued by people, as opposed to using it for social reasons. Women would decide undergoing elective egg freezing under the circumstances that the procedure wouldn’t alternate neither their current natural fertility nor the health of their future children [

49,

50].

In the UK [

51], in a recent study, when women were questioned about SEF in general, most women were informed about the high failure rates of having a genetically related to them offspring and more than 90% of women had no regrets undergoing SEF. Even though SEF has evolved even more nowadays with its enhanced medical protocols and advanced technology, the pressure women feel to “fulfill their role “in society by getting married and becoming mothers is still there [

52].

Although almost every single resident in Esfandiari’s survey [

38] was educated about egg freezing during their reproductive endocrinology and infertility classes, only half of the female residents felt comfortable enough to counsel patients about it. It is vital in the future, not only infertility doctors but also physicians, to have better and more extensive knowledge about family planning, so they can be better educated and therefore feel more comfortable counselling people about it. A similar point of view about SEF, have Iranian post-graduate students [

41]. All of the above are again confirmed by an American study [

54]. It is of vital importance educating regularly and correctly both future physicians and women about fertility, family planning and egg freezing.

Women all over Europe aren’t just more open in using ART nowadays to assist them in family making [

40,

53] but are becoming even more well informed and acquainted with the notion of pre-fertility testing such as ovarian reserve testing [

40]. A more advanced method that at a theoretical point could help women plan their future and avoid unwanted childlessness. Although women knowing their ovarian reserve might cause excess stress and anxiety towards the future, it is considered by most their right [

40].

4. Discussion

We could aim to eradicate gender inequality and reduce pressure put on women to become mothers. Research more about how we could better educate doctors and common people about SEF and ART and their true success and failure percentages. It would also be plausible to attempt to gap the financial disparity between people and ART procedures, to create extended public access to every form of ART. More studies need to be conducted to get a clearer view on people’s opinions and feelings about ART and SEF too. It would also be profitable if bioethicists were to further define the correlation between private companies’ intentions on their employees and the use of SEF.

5. Conclusions

The ever evolving technology is nowadays able to assist both doctors and individuals at the same time regarding infertility issues too. Despite the multiple legal differences on gamete and embryo cryopreservation within every country across the world, ART is a well established and wildly applicable method for assisting people with childbearing. Whether ART is publicly funded, or couples pay on full their own expenses, ART has taken the world by storm.

It has also been established that fertility in women faces a rapid decline after the age of 35. While the most frequent answer to the ‘ideal’ type of family is a heterosexual couple raising their own biological offspring, worldwide studies have proven repeatedly that when women or couples face age-related infertility, they result in some not so ‘ideal’ solutions. Artificial Reproductive Technologies, adoption and foster care are among these solutions.

The number one reason for women undergoing SEF in the first place, is the lack of male partner. That number one reason combined with age-related infertility has led to a spiked rise of SEF all over the world. While scientists are constantly attempting to justify the rise of said ‘lack of a male partner’ the problem is irreversible. Years of female sexism has led to an increase in women’s desire for educational and professional ascension. Thus, resulting to a wider gender education gap and further social gender imbalance. Also, because most women consider education and career to be of vital importance, postponing pregnancy is inevitable.

Therefore, SEF is considered by those women, who are unwilling to balance a family and a career simultaneously, the most effective option. In addition, since starting a family is resourceful, securing a stable and adequate income is important as well. Since that financial security takes time to achieve, SEF has created a biological ‘safety net’ for a lot of women. Questions of financial coverage, partial refund and the bioethical aspect of the use of SEF have also risen. It is also vital for more studies to be conducted to clarify the extent of knowledge and understanding of people willing to undergo SEF or some other form of ART.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, a big thank you to my supervising professor Christopoulos Panagiotis, for providing me with the knowledge and the right guidance to accomplish this enormous task of my post-graduate thesis. I would also like to be grateful for my supervising professor’s assistant Mr. Alkis Matsas, whose contribution made this paper complete. Furthermore, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to every single member of my family whose constant support has made it possible for me to go through this rugged journey. I would certainly not have been able to complete this manuscript without them.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Gynecologic Practice and The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (2014), Female age-related fertility decline, Available at: https://www.fertstert.org/action/showPdf?pii=S0015-0282%2813%2903464-X (Accessed: 24 June 2024).

- Mature-oocyte-cryopreservation--a-guideline_2012_f.pdf (The Practice Committees of the American Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology).

- Oocyte cryopreservation for age-related fertility loss† | Human Reproduction | Oxford Academic (oup.com) (ESHRE Task Force on Ethics and Law, including, W. Dondorp, G. de Wert, G. Pennings, F. Shenfield, P. Devroey, B. Tarlatzis, P. Barri, K. Diedrich).

- Medical versus social egg freezing: the importance of future choice for women’s decision-making | Monash Bioethics Review (springer.com).

- Flemming, R. The invention of infertility in the classical Greek world: medicine, divinity, and gender. Bull Hist Med. 2013 Winter;87(4):565-90. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain M, Singh M. Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) Techniques. [Updated 2023 Jun 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK576409/.

- Jang TH, Park SC, Yang JH, Kim JY, Seok JH, Park US, Choi CW, Lee SR, Han J. Cryopreservation and its clinical applications. Integr Med Res. 2017 Mar;6(1):12-18. Epub 2017 Jan 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fotios Spiropoulos (2020), H ιατρικά υποβοηθούμενη αναπαραγωγή: Νομική αντιμετώπιση και ηθικά ζητήματα, Available at: https://www.lawspot.gr/nomika-blogs/fotios_spyropoylos/i-iatrika-ypovoithoymeni-anaparagogi-nomiki-antimetopisi-kai-ithika In Vitro Fertilisation: Legal framework and moral issues. (Accessed: 24 June 2023).

- ESHRE Working Group on Oocyte Cryopreservation in Europe, Shenfield, F., De Mouzon, J., Scaravelli, G., Kupka, M., Ferraretti, A. P.,... & Goossens, V. (2017). Oocyte and ovarian tissue cryopreservation in European countries: statutory background, practice, storage and use. Human Reproduction Open, 2017(1), hox003. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y., & Fu, H. (2023). Social Egg Freezing for Single Women in China: Legal and Ethical Controversies. Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 2379-2389. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Wei, L., Deng, X., Luo, C., Zhu, Q., Lu, S., & Mao, C. (2022). Current status and reflections on fertility preservation in China. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 39(12), 2835-2845. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. (2023). Single women’s access to egg freezing in mainland China: an ethicolegal analysis. Journal of Medical Ethics. [CrossRef]

- García, D. , Vassena, R., & Rodríguez, A. (2020). Single women and motherhood: right now or maybe later? Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 41(1), 69-73. [CrossRef]

- Svitnev, K. (2012). New Russian Legislation on assisted reproduction.

- Crockin, S. L. , & Gottschalk, K. C. (2018, September). Legal issues in gamete and embryo cryopreservation: an overview. In Seminars in Reproductive Medicine (Vol. 36, No. 05, pp. 299-310). Thieme Medical Publishers. [CrossRef]

- Magri, S. , & Seymour, J. (2004). ART, surrogacy and legal parentage: A comparative legislative review. Victorian Law Reform Commission.

- Varlas, V. N. , Bors, R. G., Albu, D., Penes, O. N., Nasui, B. A., Mehedintu, C., & Pop, A. L. (2021). Social freezing: Pressing pause on fertility. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 8088. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal B, Evans AL, Ryan H, Martins da Silva SJ. IVF or ICSI for fertility preservation? Reprod Fertil. 2021 Mar 5;2(1):L1-L3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill CL, Chow S, Rosenwaks Z, Palermo GD. Development of ICSI. Reproduction. 2018 Jul;156(1):F51-F58. Epub 2018 Apr 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.A.; Davies, M.C.; Lavery, S.A.; Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Elective Egg Freezing for Non-Medical Reasons: Scientific Impact Paper No. 63. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 127, e113–e121. [CrossRef]

- Argyle, C. E., Harper, J. C., & Davies, M. C. (2016). Oocyte cryopreservation: where are we now? Human reproduction update, 22(4), 440-449. [CrossRef]

- ESHRE. Female Fertility Preservation Guideline of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embriology. 2020. Available online: https://www.eshre.eu/Guidelines-and-Legal/Guidelines/Female-fertility-preservation.

- Garcia-Velasco JA, Domingo J, Cobo A, Martínez M, Carmona L, Pellicer A. Five years’ experience using oocyte vitrification to pre- serve fertility for medical and nonmedical indications. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1994-1999. [CrossRef]

- Alteri, A., Pisaturo, V., Nogueira, D., & D’Angelo, A. (2019). Elective egg freezing without medical indications. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 98(5), 647-652. 5). [CrossRef]

- Varlas, V. N. , Bors, R. G., Albu, D., Penes, O. N., Nasui, B. A., Mehedintu, C., & Pop, A. L. (2021). Social freezing: Pressing pause on fertility. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 8088. [CrossRef]

- Cil, A. P. , Bang, H., & Oktay, K. (2013). Age-specific probability of live birth with oocyte cryopreservation: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Fertility and sterility, 100(2), 492-499. [CrossRef]

- Doyle, J. O., Richter, K. S., Lim, J., Stillman, R. J., Graham, J. R., & Tucker, M. J. (2016). Successful elective and medically indicated oocyte vitrification and warming for autologous in vitro fertilization, with predicted birth probabilities for fertility preservation according to number of cryopreserved oocytes and age at retrieval. Fertility and sterility, 105(2), 459-466. [CrossRef]

- Cobo, A. , García-Velasco, J., Domingo, J., Pellicer, A., & Remohí, J. (2018). Elective and onco-fertility preservation: factors related to IVF outcomes. Human reproduction, 33(12), 2222-2231. [CrossRef]

- ESHRE. Female Fertility Preservation Guideline of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embriology. 2020. Available online: https://www.eshre.eu/Guidelines-and-Legal/Guidelines/Female-fertility-preservation.

- Hafezi M, Zameni N, Nemati Aghamaleki SZ, Omani-Samani R, Vesali S. Awareness and attitude toward oocyte cryopreservation for non-medical reasons: a study on women candidates for social egg freezing. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2022 Dec;43(4):532-540. Epub 2022 Aug 23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giannopapa M, Sakellaridi A, Pana A, Velonaki VS. Women Electing Oocyte Cryopreservation: Characteristics, Information Sources, and Oocyte Disposition: A Systematic Review. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2022 Mar;67(2):178-201. Epub 2022 Feb 13. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, D. , Vassena, R., & Rodríguez, A. (2020). Single women and motherhood: right now or maybe later? Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 41(1), 69-73. [CrossRef]

- Kanters, N. T. J. , Brokke, K. E., Bos, A. M. E., Benneheij, S. H., Kostenzer, J., & Ockhuijsen, H. D. L. (2022). An unconventional path to conventional motherhood: A qualitative study of women’s motivations and experiences regarding social egg freezing in the Netherlands. Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics and Human Reproduction, 51(2), 102268. [CrossRef]

- Jones, B. P. , Kasaven, L., L’Heveder, A., Jalmbrant, M., Green, J., Makki, M.,... & Ben Nagi, J. (2020). Perceptions, outcomes, and regret following social egg freezing in the UK; a cross-sectional survey. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 99(3), 324-332. [CrossRef]

- Gürtin, Z. B. , Morgan, L., O’Rourke, D., Wang, J., & Ahuja, K. (2019). For whom the egg thaws: insights from an analysis of 10 years of frozen egg thaw data from two UK clinics, 2008–2017. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics, 36, 1069-1080. [CrossRef]

- Pennings, G. (2021). Elective egg freezing and women’s emancipation. Reproductive biomedicine online, 42(6), 1053-1055. [CrossRef]

- Jones, B. P. , Saso, S., Mania, A., Smith, J. R., Serhal, P., & Ben Nagi, J. (2018). The dawn of a new ice age: social egg freezing. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 97(6), 641-647. [CrossRef]

- Esfandiari, N. , Litzky, J., Sayler, J., Zagadailov, P., George, K., & DeMars, L. (2019). Egg freezing for fertility preservation and family planning: a nationwide survey of US Obstetrics and Gynecology residents. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 17, 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Schick, M. , Sexty, R., Ditzen, B., & Wischmann, T. (2017). Attitudes towards social oocyte freezing from a socio-cultural perspective. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 77(07), 747-751. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Y. , Martyn, F., Glover, L. E., & Wingfield, M. B. (2017). What women want? A scoping survey on women’s knowledge, attitudes and behaviours towards ovarian reserve testing and egg freezing. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 217, 71-76. [CrossRef]

- Akhondi, M. M. , Ardakani, Z. B., Warmelink, J. C., Haghani, S., & Ranjbar, F. (2023). Knowledge and beliefs about oocyte cryopreservation for medical and social reasons in female students: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Women’s Health, 23(1), 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Mark Tran (2014), Apple and Facebook offer to freeze eggs for female employees, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/oct/15/apple-facebook-offer-freeze-eggs-female-employees (Accessed: 24 June 2023).

- Mertes, H. , & Pennings, G. (2012). Elective oocyte cryopreservation: who should pay?. Human reproduction, 27(1), 9-13. [CrossRef]

- Mertes, H. (2015). Does company-sponsored egg freezing promote or confine women’s reproductive autonomy?. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics, 32, 1205-1209. [CrossRef]

- Zoll, M. , Mertes, H., & Gupta, J. (2015). Corporate giants provide fertility benefits: have they got it wrong?. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 195, A1-A2. [CrossRef]

- Petersen, T. S. , & Hansen, R. (2022). Company-sponsored egg freezing: an offer you can’t refuse?. Bioethics, 36(1), 42-48. [CrossRef]

- Tozzo, P. , Fassina, A., Nespeca, P., Spigarolo, G., & Caenazzo, L. (2019). Understanding social oocyte freezing in Italy: a scoping survey on university female students’ awareness and attitudes. Life sciences, society and policy, 15(1), 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Kostenzer, J. , de Bont, A., & van Exel, J. (2021). Women’s viewpoints on egg freezing in Austria: an online Q-methodology study. BMC medical ethics, 22, 1-12. Women’s viewpoints on egg freezing in Austria: an online Q-methodology study.

- Stoop, D. , Nekkebroeck, J., & Devroey, P. (2011). A survey on the intentions and attitudes towards oocyte cryopreservation for non-medical reasons among women of reproductive age. Human Reproduction, 26(3), 655-661. [CrossRef]

- Schick, M. , Sexty, R., Ditzen, B., & Wischmann, T. (2017). Attitudes towards social oocyte freezing from a socio-cultural perspective. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 77(07), 751-755. [CrossRef]

- Jones, B. P. , Kasaven, L., L’Heveder, A., Jalmbrant, M., Green, J., Makki, M.,... & Ben Nagi, J. (2020). Perceptions, outcomes, and regret following social egg freezing in the UK; a cross-sectional survey. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 99(3), 324-332. [CrossRef]

- Gil-Arribas, E. , Blockeel, C., Pennings, G., Nekkebroeck, J., Velasco, J. A. G., Serna, J., & De Vos, M. (2022). Oocyte vitrification for elective fertility preservation: a SWOT analysis. Reproductive biomedicine online, 44(6), 1005-1014. [CrossRef]

- Wennberg, A. L. , Rodriguez-Wallberg, K. A., Milsom, I., & Brännström, M. (2016). Attitudes towards new assisted reproductive technologies in Sweden: a survey in women 30–39 years of age. Acta obstetricia et gynecologica Scandinavica, 95(1), 38-44. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, A. G. , Woods, M., Keomany, J., Grainger, D., Shah, S., & Pavone, M. (2023). What do female medical students know about planned oocyte cryopreservation and what are their personal attitudes?. Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics, 40(6), 1305-1311.54. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).