1. Introduction

1.1. Context

The increasing complexity and dynamism of markets have led companies to reconsider their strategic and operational approaches, especially in human resource management. Innovation and dynamic capability (dynamic capability) have become strategic imperatives to meet organizational challenges (Cappelli & Tavis, 2018; Teece, 2007). This environment requires companies to promote organizational learning and optimize both processes and resource allocation, which is essential to maintain competitiveness (Wollersheim & Heimeriks, 2016).

However, organizational adaptability requires an evolution beyond traditional, linear management models, which are typically deterministic and hierarchical. These approaches assume a rarely observed stability of the environment, making them obsolete strategies in the face of changing conditions (Hoverstadt, 2020). Companies face constantly changing environments, characterized by uncertainty and complexity, which require agile and flexible responses (Lechler et al., 2022). The ability to adapt and evolve becomes crucial to add value and ensure organizational sustainability (McMackin & Heffernan, 2021).

In this context, human resource management (HRM) has positioned itself as a key strategic component. Beyond traditional functions, HRM seeks to create competitive advantage by effectively managing human capital, promoting not only efficiency, but also employee well-being (Jiang et al., 2012; Wright & Ulrich, 2017). This transformation towards agile HRM involves a restructuring that goes beyond process redesign and the implementation of tools such as kanban, scrums and sprints, which, although useful, are not sufficient when employed in isolation (McMackin & Heffernan, 2021). True organizational agility requires a profound cultural change that integrates flexible structures, adaptive mindsets and effective information flows.

Systems thinking emerges as an essential approach to agile HRM adoption, enabling a holistic view of the organization as a complex adaptive system (CAS), characterized by self-organization, emergence, and continuous evolution (Holland, 1995). This perspective challenges traditional logic, promoting self-organization and adaptation without strict centralized supervision, resulting in a more resilient organization capable of responding proactively to changes in the environment (Bohórquez Arévalo, 2013).

Companies that adopt this systemic approach will be able to visualize their operations not as a set of isolated activities, but as an interconnected and dynamic system. This viable HRM model facilitates the understanding of organizational complexity and promotes collaboration and co-creation across all areas of the company, enabling HR leaders to design practices that respond effectively to the complex and changing environment (Burke & Morley, 2023a; McMackin & Heffernan, 2021).

1.2. Conceptual Framework

1.2.1. Systemic Thinking

Systems thinking has established itself as a key alternative for understanding organizational dynamics, particularly in the face of the growing complexity of business environments. As simple solutions have proven insufficient to address complex problems, the systems approach has gained relevance for its ability to offer an integrative and holistic view (Jackson, 2003; Senge, 2005). This approach does not focus solely on the individual parts of an organization, but on how they interact with each other and with their environment. Instead of fragmenting the company, it is analyzed as an integrated whole, understanding the interrelationships and synergies that determine its functioning (Midgley & Lindhult, 2021; Wilber, 1996).

From this perspective, the firm is conceived as a system composed of subsystems operating within a suprasystem, where each component has an essential role in a recursive and adaptive structure (Jackson, 2003). Systems thinking is especially useful for addressing organizational problems that involve multiple interrelated factors, allowing for a deeper understanding and more effective response to uncertainty and complexity (Hoverstadt, 2020). By looking at the connections and dependencies between elements, this approach facilitates the identification of emerging patterns and innovative solutions.

However, recognizing the importance of systems thinking is not enough. Its implementation requires active development and strategic application to solve organizational problems creatively (Midgley et al., 2013). This involves adopting diverse perspectives to enhance the organization's ability to adapt and anticipate change. Systems thinking fosters a mindset of continuous improvement and organizational learning, fundamental to manage complexity and ensure long-term sustainability (Jackson, 2003; Senge, 2005).

1.2.2. Characterization of the Company as an Adaptive Complex System

Companies can be understood as complex adaptive systems (CAS) due to their non-linear feedback loops, which arise from the interaction between the people that make them up. These interactions generate patterns of behavior that, on many occasions, emerge without clear intentionality and without being aligned with the original purposes of those who provoke them, resulting in unplanned and often intuitive actions. Firms, being systems sensitive to their environment and innovations, operate far from equilibrium, making them dynamic organisms that respond in a nonlinear way to changes in the environment (Holland, 1995; Stacey, 1995). Interactions among employees depend on their individual perceptions, which adds a layer of complexity to organizational dynamics, making outcomes often unpredictable and difficult to manage through traditional approaches (Colbert, 2004)

As complex adaptive systems, firms are characterized by self-organization and constant exchange of information with their environment, positioning them in dissipative structures that require a balance between exploration and exploitation of the environment to remain competitive (Prigogine & Stengers, 2018). These processes allow companies to evolve and co-evolve with their environment, developing capabilities for internal transformation and adaptation to external changes (Espinosa & Porter, 2011). The nonlinear nature of CAS complicates the prediction and control of the organizational future through linear or deterministic approaches (Bohórquez Arévalo, 2013), underscoring the need for more dynamic and flexible approaches to manage complexity and uncertainty in today's organizations (Burke & Morley, 2023).

1.2.3. HRM

Human resource management (HRM) has become a key strategic approach to managing human capital, considered one of the most valuable assets within an organization. Human resources (HR), both individually and collectively, play a key role in meeting business objectives (Armstrong & Taylor, 2020). HRM is defined as a dynamic set of policies and processes that, aligned with business strategy, contribute to improving organizational efficiency (Jiang et al., 2012). From a resource perspective, HRM enables companies to select, develop and optimize their human capital, turning it into a source of sustainable competitive advantage, provided it possesses characteristics such as differentiation, value and inimitability (Barney, 2000; Becker & Huselid, 2006). This approach encourages comprehensive management that not only maximizes organizational performance, but also promotes the development of unique capabilities that are difficult for competitors to replicate (Wright & Ulrich, 2017).

The fundamental purpose of HRM is to equip the firm with capabilities that ensure its organizational performance by addressing three key dimensions (Delery & Roumpi, 2017; Jiang et al., 2012). The first is to equip employees with the knowledge, skills and attitudes necessary to fulfill their roles efficiently; to this end, recruitment, selection, training and development processes are essential (Apascaritei & Elvira, 2022). The second dimension seeks to motivate employees both intrinsically and extrinsically, through remuneration policies, performance management and labor relations management. Finally, the third dimension ensures that employees have opportunities for professional growth and development, with job design and talent management being key to facilitating their impact on the organization (Lepak et al., 2006). Taken together, these dimensions enable HRM to not only support the achievement of business objectives, but also contribute to employee well-being and organizational sustainability in the long term (Sparrow et al., 2017).

2. Applicable Approaches and Methodologies

2.1. Complex Adaptive Systems

Complex adaptive systems (CAS) as proposed by Holland (1995) are systems whose behavior depends predominantly on the interactions between their components, rather than on their individual actions. CAS are made up of agents that interact and adapt as they gain experience, but none of these interactions alone determines the overall behavior of the system. Feedback processes are essential in CASs, as they contribute to the diversity and ability of the system to respond to changes in its environment. Fundamental characteristics of CASs are self-organization, emergence, and evolution, which allow the system to adjust and evolve from the interactions between its parts (Colbert, 2004; Miltleton-kelly, 2003). These systems exhibit emergent behaviors, which means that collective dynamics are not reducible to the actions of individual agents but emerge from the interaction between them (McKelvey, 1999).

Self-organization in CAS occurs in open systems that exchange information and energy with their environment, maintaining themselves in states of limited instability (Nicolis & Prigogine, 1989). These systems are characterized by the coexistence of stable and unstable, predictable and unpredictable states (Kauffman, 1995). Emergence is the result of events arising from interactions between agents, making it difficult to project future scenarios (Holland, 2015; Vesterby, 2019). Through this process, CASs create new dissipative structures that transform existing patterns, promoting self-organization and continuous change. Evolution, understood as the system's capacity for transformation, depends on adaptive flexibility to the environment and on the efforts of each agent to improve its capabilities in response to system demands (Espinosa & Porter, 2011; Holland, 1995). This systemic approach stresses the importance of adaptability and constant evolution in dynamic and complex environments.

2.2. Viable System Model (VSM)

The viable system model (VSM) has established itself as an effective tool for understanding how human resource management (HRM) deals with the complexity inherent in its tasks. The VSM provides a structured representation of the enterprise and its subsystems, making it possible to visualize how they interact with each other and with their environment (Hoverstadt, 2020). It is characterized by its capacity for self-organization, self-control and autonomy, which makes it a highly adaptive model (Beer, 1984). By interpreting organizations as organisms with brains, the VSM facilitates the capture of their “essential organization”, i.e., the configuration that allows a system to maintain its identity and autonomy in the face of external changes (Beer, 1995; Jackson, 2003). This approach is crucial to understanding how firms can remain viable in increasingly complex and changing environments.

Self-organization in CAS occurs in open systems that exchange information and energy with their environment, maintaining themselves in states of limited instability (Nicolis & Prigogine, 1989). These systems are characterized by the coexistence of stable and unstable, predictable and unpredictable states (Kauffman, 1995). Emergence is the result of events arising from interactions between agents, making it difficult to project future scenarios (Holland, 1995; Vesterby, 2019). Through this process, CASs create new dissipative structures that transform existing patterns, promoting self-organization and continuous change. Evolution, understood as the system's capacity for transformation, depends on adaptive flexibility to the environment and on the efforts of each agent to improve its capabilities in response to system demands (Espinosa & Porter, 2011 Holland, 1995). This systemic approach stresses the importance of adaptability and constant evolution in dynamic and complex environments.

2.3. Previous Investigations

Studies that approach organizations from complexity conceive them as nonlinear systems (Allen et al., 2011). In the last decade, research on human resource management (HRM) from the perspective of complex adaptive systems (CAS) has been limited in the Web of Science database. According to the literature review conducted, no publications with “HRM” and “CAS” in the title were found, although four publications were identified with the terms “human resource management” and “complexity”. Only one of these focuses on sustainable human resource management from a CAS perspective (Nuis et al., 2021), while the other three address topics such as controversies between HRM and organizational outcomes (Truss, 2001), complexity in labor relations (Ackers, 2019), and tensions between HRM and technology departments (Tate et al., 2013).

With the term “human resource management” and “complex”, four studies were identified, of which only one theorizes the contemporary HRM ecosystem as complex and adaptive (Burke & Morley, 2023). The others address root-cause optimization (Andrade & Carinhana, 2021; Butko, 2019), the design of an HRM model based on complex systems (Yu & Wu, 2017), and the application of complexity principles in human resources (Colbert, 2004). Regarding the descriptor “human resources management” and “viable”, two publications were found: one on project-oriented HRM based on the viable system (Huemann, 2016) and another examining how the viable systems approach contributes to governance in government service systems (Golinelli et al., 2002).

Although there are studies linking HRM to complex and viable systems, research remains limited (Bohórquez Arévalo, 2013; Espinosa & Porter, 2011).The existing literature focuses mostly on the relationship between HRM practices and organizational performance, neglecting a deeper understanding of processes. Many authors recognize gaps in knowledge about managing complex problems and optimizing resources within organizations. Furthermore, they agree on the need for models that identify key causes of problems (Andrade & Carinhana, 2021) and enhance the understanding of dialogue in the context of HRM as an emergent process within complex systems (Nuis et al., 2021). To advance systems thinking and foster collaborative capabilities in HRM, this research proposes to design a viable model of HRM based on systems thinking to better understand its complexity.

The research is divided into five sections: introduction, method, results, and finally, discussion and conclusions.

3. Materials and Methods

This qualitative, desk-based research (Creswell & Creswell, 2017) was conducted in two phases. The first consisted of a literature review at the frontier of knowledge to answer the questions: are there publications that relate HRM to complexity? Have HRM proposals based on the VSM been published? For this purpose, the Web of Science (WoS) database was used, and two inclusion criteria were applied: publications in English and containing in the title the combinations of descriptors “HRM” and “complexity”, “complex”, or “viable”. Following the PRISMA framework (Page et al., 2021), 19 records were identified. In the filtering phase, four duplicates and three were eliminated for not meeting the criteria, leaving a total of 12 records for qualitative synthesis. The objectives and methodologies of these studies were analyzed, evidencing a paucity of research on HRM from the perspective of VSM and CAS.

In the second phase, a viable HRM model was designed based on Beer's (1995) VSM, using Checkland's (1999) soft systems methodology. The process included three stages: selection of the systemic tool, transdisciplinary data collection, and model configuration. Levels of system recursion were identified, and a diagnostic was performed to analyze the environment and the five key systems of the VSM, ensuring their coherence and viability in the context of human resource management in complex environments.

In phase three, the viable HRM model (Beer, 1995; Jackson, 2003) is configured in two main stages: i) System identification, where the three levels of recursion are determined. The “focus system” is identified (recursivity level 1, the company), the system of which it is a part is specified (level 0, the industrial sector), and the viable parts of the “focus system” (level 2, HRM). ii) System diagnosis, where the environment and the five key systems are analyzed. System one studies operations and measures performance, system two identifies sources of conflict or harmonization, system three monitors auditing and compliance, system four focuses on adapting to the future, and system five defines system policy and identity. Finally, it ensures that systems two, three, four and five work in a coordinated manner to ensure the viability and success of the system.

4. Results

The Viable Model of Human Resource Management (MV-HRM) seeks to facilitate the understanding of HRM through a systemic approach, especially from the perspective of complexity. This model highlights the interaction, interrelation and interconnection between the systems that comprise it, as well as their link with the environment. Emergence and self-organization are conceived as inherent properties of both the enterprise and HRM, since it is composed of five autonomous systems (implementation, coordination, operational control, development and policy) that interact continuously, altering or transforming the behavior of the whole (Holland, 1995). Importantly, the behavior of these systems is determined by the configuration of shared meanings that emerge from the processes of system interaction (Weick et al., 2005). After all, the firm operates in adaptive environments that are constantly transforming (Holland, 1995).

4.1. MV-HRM Recursion

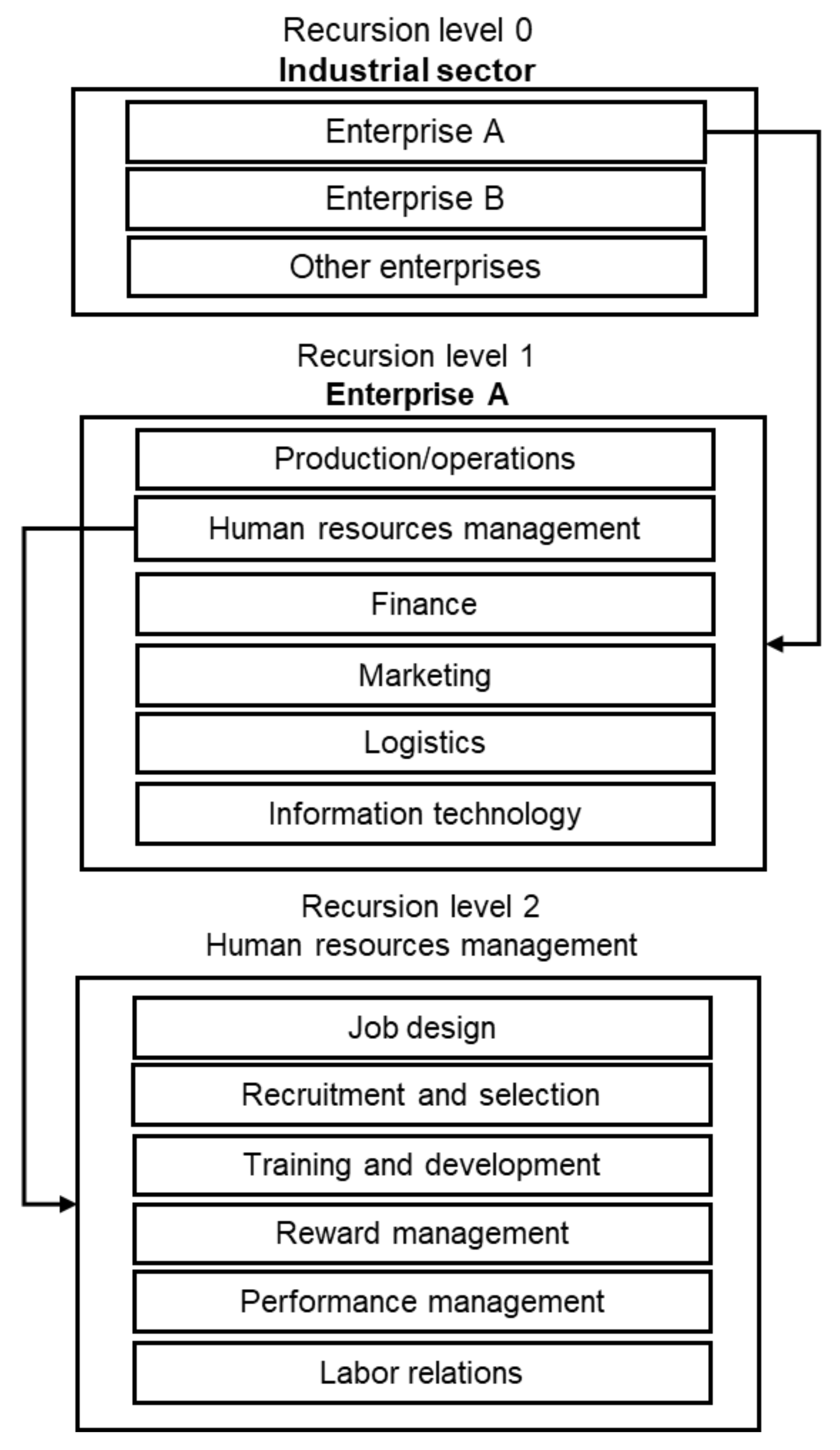

Based on the assumption that complex systems have a recursive nature, i.e., that systems occur in hierarchies, and that the organizational form of higher-level systems can be found repeated in the parts (according to cybernetics, all viable systems manifest the same organizational characteristics) (Beer, 1995), the recursive nature of the MV-HRM is established, see

Figure 1.

There are three levels of recursion (Beer, 1995). At level zero, or suprasystem, is the industrial sector to which the company belongs. Level one, called “focus system”, corresponds to the company itself, composed of areas such as HRM, marketing, production, finance and logistics. At level two, considered a subsystem of level one, is HRM, which encompasses key processes such as job design, recruitment and selection, training and development, compensation administration, performance management and labor relations (Armstrong & Taylor, 2020; Jiang et al., 2012; Snell et al., 2020; Wright & Ulrich, 2017).

4.2. Viable HRM System

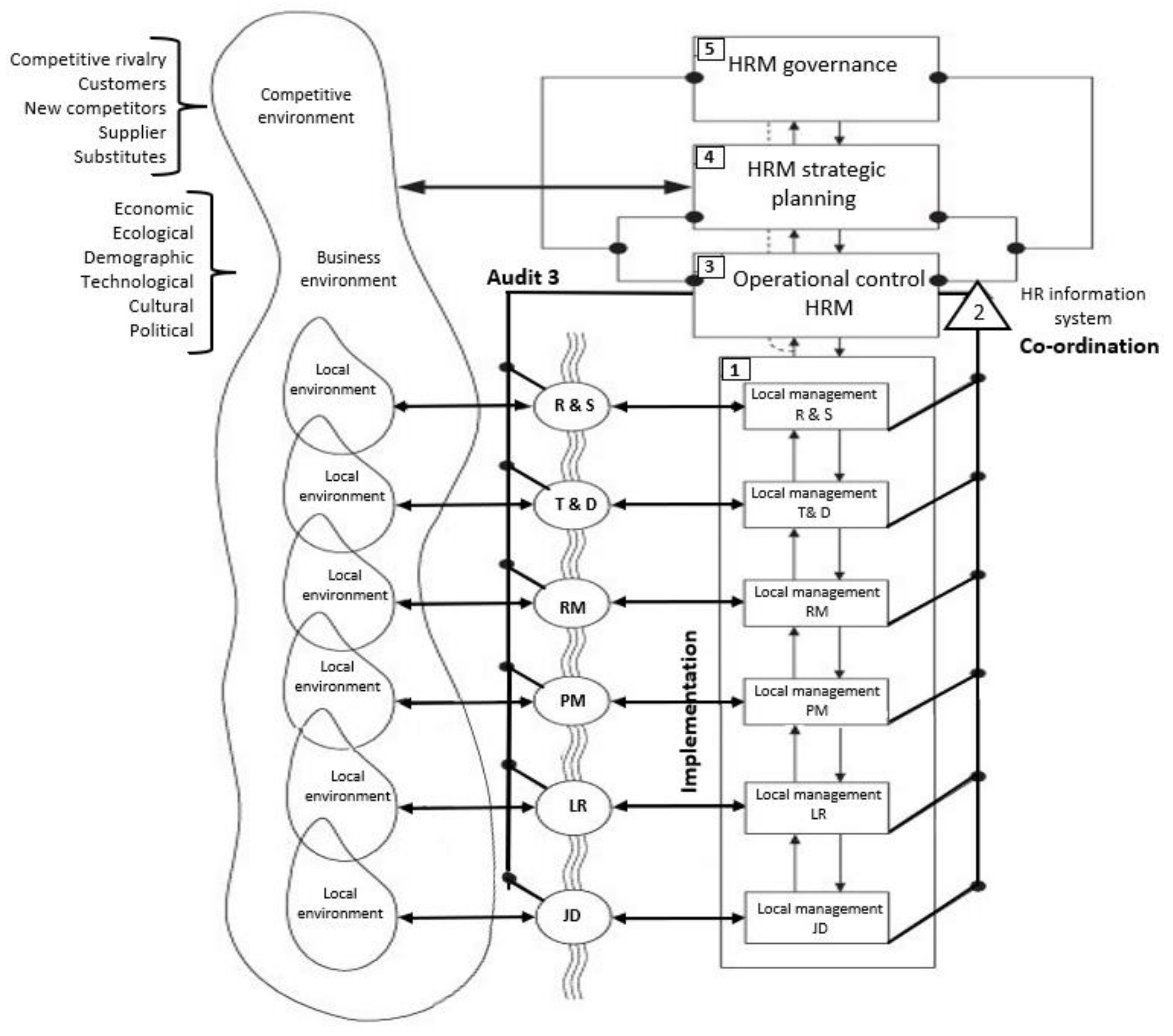

The Viable Model of Human Resource Management (MV-HRM), based on Beer's (1995) Viable Systems Model (VSM), is made up of the environment and five interconnected systems. System one (S1) encompasses HRM's operational processes; system two (S2) refers to HR's information system; system three (S3) corresponds to HRM's operational control; system four (S4) manages strategic planning; and system five (S5) is responsible for HRM's overall governance and direction. See

Figure 2.

System 1 (S1) of the Viable Human Resources Model (MV-HRM) reflects the key objectives and functions of human resource management (HRM). Each process within HRM, such as recruitment and selection (R&S), training and development (T&D), compensation administration (RA), performance management (PM), labor relations (LR), and job design (PD), is linked to environmental factors that directly influence its operations. These processes do not operate in isolation, but interact with each other, sharing resources, information or even facilities. The operational autonomy of each process allows an agile response to changes in the environment, based on its own policies and operational plans. This approach allows HRM processes not only to adapt to changes but also to maintain effective control and leadership within the organizational system (Beer, 1995). A clear example is the recruitment process, which follows the guidelines established by management, but is adjusted according to operational particularities and receives constant feedback to implement improvements.

The integration of the different HRM processes with the environment and with each other is essential to ensure their success. Through the MV-HRM, it is highlighted how the R&S processes depend on coordination with other subsystems such as C&D, RA and AD to achieve their objectives. The HRM information system (HRIS), known as S2, plays a crucial role in ensuring that these processes are properly coordinated and do not conflict. The HRIS facilitates communication between the various processes by collecting and analyzing relevant data, enabling informed and strategic decision making (Falletta & Combs, 2020; Marler & Boudreau, 2017). This data can be both internal and external and covers various areas of the company, such as finance, production and marketing (Ontrup et al., 2021). Data quality and availability are essential to ensure that decisions based on this data are accurate and effective (Guzzo et al., 2015).

The HRM operational control system, designated as S3, is responsible for ensuring that the objectives set by strategic planning (S4) and HRIS guidelines are effectively met. This system constantly audits and evaluates the performance of HRM processes, using key performance indicators at both the individual and organizational levels. If deviations are detected, the S3 can correct them immediately, ensuring that the system functions optimally. In addition, this system collects key information that is then transmitted to the governance system (S5) for decision making at the political and strategic level. The role of the S3 is crucial, as it ensures alignment between overall HRM policies and day-to-day operations (Armstrong, 2006).

While HRM subsystems such as S2 and S3 have some autonomy, they lack a global view of the business environment. This is where HRM strategic planning (S4) comes into play, whose function is to integrate environmental information with operational data and respond to both future opportunities and threats. This system can project the company's needs in terms of human resources, both in terms of quantity and quality. In addition, S4 is responsible for processing the information gathered by S3 to ensure that the company not only remains operational, but also evolves effectively in a dynamic environment (Beer, 1995). The responsiveness of S4 to changes in the environment is vital to maintaining organizational competitiveness.

Finally, the HRM governance system (S5) is responsible for directing and coordinating the entire system. Based on the information provided by S4, S5 establishes general policies and ensures that they are applied in the various HRM processes. This system faces the challenge of balancing the internal and external demands of the organization, ensuring that the company adapts to its environment without compromising its internal stability. In addition, S5 involves various stakeholders, both internal and external, who participate in strategic decision making. The ability of S5 to integrate interactions and maintain organizational flexibility is crucial for the HRM system to remain viable and aligned with the objectives of the firm (Beer, 1995).

Figure 2 shows how feedback flows in both directions, allowing for greater adaptation and self-management of the system in the face of a complex and changing environment.

4.3. MV-HRM Processes

According to the viable model, the processes are linked to each other and to the environment. To specify these interrelationships that are configured by means of information, the following shows (in a crude way and as an example) the information that each process receives or requires -from outside and inside the system-, as well as the output information generated by each one.

4.3.1. Job Design Process (PDP)

The Job Design Plan (PDP) focuses on determining the workflow and job mix needed to meet the company's objectives (Armstrong, 2006; Snell et al., 2020). To do so, it requires external information, such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically those related to gender equality, decent work, innovation and infrastructure, and reducing inequalities. It also needs data on global markets, such as labor mobility, downsizing (job elimination), outsourcing (process outsourcing) and offshoring (moving work abroad), as well as on labor regulations and labor market trends, including job supply and demand, wages and job descriptions (Snell et al., 2020). In addition, information on the human resources market is considered relevant: age, schooling, gender, health and nationality.

In terms of internal inputs, the PDP requires data from other business processes, such as their functioning and objectives, as well as information from HRM processes: training and development (job competencies), compensation administration (job evaluation and salaries), labor relations (collective and individual bargaining), and performance management (competency standards and performance appraisal). The PDP generates as outputs key information, such as workflow, job analysis and descriptions, and job design methods (See

Table 1). These outputs also serve as inputs for other processes, thus integrating the PDP with the rest of the company's internal and external systems.

4.3.2. Recruitment and Selection Process (R&S)

The objective of the R&SP is to locate, attract and select the most suitable candidates for the company (Armstrong, 2006; Snell et al., 2020). This process is linked to both external factors, such as the labor market and staffing needs, and internal factors, such as the requirements of areas like production and marketing, as well as the budget allocated by finance. It also interfaces with other HRM processes, such as job design, training and development, compensation management, performance and labor relations. PR&S outputs include job offers, candidate profiles, reports to government agencies, and recruitment and selection methods. See details in

Table 2.

4.3.3. Training and Development Process (T&D Process)

The T&D Process aims to promote learning and develop the labor competencies of personnel (Armstrong, 2006; Snell et al., 2020). It is externally connected to educational institutions, the labor market, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), global markets, and labor regulations. Internally, it is linked with other company processes, according to their objectives and training needs, and with the finance department, due to the allocated budget. Additionally, it is interrelated with HRM processes such as job design, performance management, and labor relations. The outputs of the T&D Process include the training program, career plans, career path, reports for government agencies, and training and development methods. See details in

Table 3.

4.3.4. Remuneration Administration Process (RAP)

The RAP is responsible for designing strategies, policies, and processes to ensure that employees' contributions are recognized both financially and non-financially (Armstrong & Murlis, 2007). It requires external information, such as economic data, labor regulations, government policies, labor market behavior, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and input from unions. Internally, the RAP is linked with other company processes, especially with finance, to determine the economic capacity and budget allocated for remuneration. Additionally, it is interrelated with HRM processes, such as job design, performance management, labor relations, and recruitment and selection. The outputs of the RAP include job evaluations, salary scales, benefits, incentives, payroll, reports to government agencies, and remuneration administration methods. See details in

Table 4.

4.3.5. Performance Administration Process (PAP)

The PAP aims to motivate and promote employee development (Armstrong, 2006; Snell et al., 2020). Its external inputs include SDG 5 (gender equality), the behavior of global and labor markets, and labor regulations. Regarding internal inputs, it is linked with company processes, particularly finance, and with HRM processes, such as job design, training and development, and labor relations. The outputs of the PAP include performance standards and labor competencies, performance evaluations, validation of selection tests, as well as promotions, transfers, dismissals, and performance management methods. See details in the

Table 5.

4.3.6. Labor Relations Process (LRP)

The LRP focuses on establishing and maintaining the link between the company and its workers (Armstrong & Taylor, 2020). Its external inputs include labor and political regulations, the economic behavior of the labor market, global markets, and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Regarding internal inputs, information is required from other business processes, such as their objectives and operations, and from the finance process, specifically the company’s financial capacity. Information from other HRM processes, such as job design, performance management, training and development, and remuneration administration, is also essential. The outputs of the LRP include individual and collective labor negotiations and contracts, management of occupational risks and disability, internal work regulations, safety and health programs, and collective bargaining methods. See details in

Table 6.

By observing the 6 processes of the HRM system, they are closely linked to the environment, so their autonomy is crucial to achieving objectives and responding to the dynamism and complexity of today's world. However, it is essential to balance control and autonomy: too much control limits operations and hinders adaptation to the environment, while too much autonomy can prevent the achievement of objectives (Beer, 1995). HRM governance defines direction, strategic planning establishes the relationship with the external environment, operational control measures performance, and the information system synchronizes activities. The HRM processes are the operational action of the system. By conceiving HRM as a viable system that self-organizes and controls itself, the connection with the internal and external environment is facilitated, allowing for more effective decisions to equip the company with the necessary capabilities to meet its objectives and vision.

5. Discussion

The companies that survive are those that best adapt to their environment, regardless of their size (Snell et al., 2020). To face changes, it is key to redesign the company to make it agile (Snell et al., 2020) and to understand it from a systems thinking perspective (Beer, 1995; Checkland & Scholes, 1999; Senge, 2005; Wilber, 1996). In human resources management (HRM), a simple view rarely works due to its complexity, requiring holistic (Wilber, 1996) and creative (Jackson, 2003) solutions. It is no longer viable to see companies in a fragmented way, losing connection with the whole (Senge, 2005).

Given the relevance of HR in value generation, it is crucial to analyze and understand the HRM system as a source of sustainable competitive advantage. It is necessary to overcome the classic management view that separates the system into parts without understanding the whole(Wright & Ulrich, 2017). These parts must be controlled by manipulating inputs and supervising outputs (Beer, 1995) to help companies achieve their objectives. It is not about adopting the most popular management, but about a profound change that fosters systems thinking (Beer, 1995) and ensures flexible structures, organizational efficiency, and transformational leadership (Chen et al., 2016; Ramezan, 2011).

The business environment is dynamic: consumer preferences change, new competitors emerge, and political and social arrangements are modified. The HRM system will be viable if it can skillfully adapt to these changes (Beer, 1995; Jackson, 2003). Companies oscillate between order and chaos, and when they deviate from pre-established patterns, they encourage creativity and innovation (Kauffman, 1995). The MV-HRM questions the traditional managerial role, promoting participatory decision-making, where responsibility falls on all members of the HRM system, not just management (Beer, 1995).

To generate a competitive advantage, a company must be agile (Snell & Morris, 2020), which requires a new vision and the development of capabilities in the HRM system’s collaborators. The MV-HRM shows how HRM practices impact both the internal environment, affecting financial outcomes and organizational resources (De Cieri & Lazarova, 2021; Jiang et al., 2012), and the external one, influencing the economic, political, social, and environmental spheres.

6. Conclusion

The agility and performance of the HRM system do not depend on a single process but on the proper interaction between all its parts. Optimizing an isolated component is not enough if the interactions do not function correctly, as this can destabilize the system as a whole (Beer, 1995; Jackson, 2003). For this reason, a viable HRM model based on systems thinking is proposed, facilitating the understanding of its complexity through Beer’s VSM (Beer, 1995), which organizes the structure and processes that make up the system.

The MV-HRM consists of five key systems: HRM processes (S1), the HRM information system (S2), operational control (S3), strategic planning (S4), and HRM governance (S5). The model emphasizes interactions with the immediate and future environment, highlighting the importance of constant feedback. The objectives are dynamic and constantly changing due to the system's dependence on its external and internal environment. Information and communication are essential to ensure the system’s cohesion and adaptation.

The results of the literature review in WoS show a lack of research that studies HRM from a systemic and complex perspective (Ackers, 2019; Andrade & Carinhana, 2021; Burke & Morley, 2023a; Colbert, 2004; Nuis et al., 2021). Most studies focus on the relationship between HRM practices and performance, neglecting a deeper understanding of the processes (Wright & Ulrich, 2017). The MV-HRM focuses on analyzing the entire functioning of the HRM system, providing a new perspective from complex adaptive systems and attracting the interest of strategists in developing better practices.

As a limitation, the MV-HRM is a theoretical proposal that requires a deeper analysis of the immediate and future environment. Furthermore, the literature review only included English-language publications from WoS. It is suggested to broaden the scope in future research and combine the perspectives of performance with those of CAS and VSM to more accurately study the links and functioning of the HRM system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.F., G.S. and A.B.; methodology, M.A.F; software, M.A.F.; validation, M.A.F., G.S. and A.B.; formal analysis, M.A.F. and G.S; investigation, M.A.F. and G.S; resources, M.A.F. and G.S.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.F.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, M.A.F.; supervision, G.S.; project administration, M.A.F.; funding acquisition, M.A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Instituto Politécnico Nacional, the Secretaría de Investigación y Posgrado, and the Unidad Interdisciplinaria de Ingeniería y Ciencias Sociales y Administrativas for the facilities granted for this work. We also thank the Sistema Nacional de Investigadores del Conahcyt, the Conahcyt postgraduate scholarship and the Programa de Estímulo al Desempeño Docente, as well as the participants in this research for their collaboration and willingness. The authors are grateful to the editors and anonymous reviewers for their comments and discussions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ackers, P. (2019). Neo-pluralism as a research approach in contemporary employment relations and HRM: complexity and dialogue. Chapters, 34–52. Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/h/elg/eechap/17759_3.html.

- Allen, P., Maguire, S., & McKelvey, B. (2011). The SAGE handbook of complexity and management. The SAGE Handbook of Complexity and Management, 1–644. [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M. Andrade, M., & Carinhana, D. (2021). Decision-making approach for complex problems management in a scarce human resources environment. Journal of Modelling in Management, 16, 1302–1327. [CrossRef]

- Apascaritei, P., & Elvira, M. M. (2022). Dynamizing human resources: An integrative review of SHRM and dynamic capabilities research. Human Resource Management Review, 32, 100878. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. (2006). Resource Management Resource Management Practices. Tenth Ediction, Kogan Page Publishing, London, 1–975. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/A_Handbook_of_Human_Resource_Management.html?hl=es&id=D78K7QIdR3UC.

- Armstrong, Michael., & Murlis, Helen. (2007). Reward management : a handbook of remuneration strategy and practice. 722. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Reward_Management.html?hl=es&id=oTaSWA-FeroC.

- Armstrong, Michael., & Taylor, Stephen. (2020). Armstrong’s handbook of human resource management practice. 763. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Armstrong_s_Handbook_of_Human_Resource_M.html?hl=es&id=g7zEDwAAQBAJ.

- Barney, J.B. (2000). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Advances in Strategic Management, 17, 203–227. [CrossRef]

- Becker, B. E., & Huselid, M. A. (2006). Strategic Human Resources Management: Where Do We Go From Here? 32, 898–925. [CrossRef]

- Beer, S. (1984). The Viable System Model: Its Provenance, Development, Methodology and Pathology. The Journal of the Operational Research Society, 35, 7. [CrossRef]

- Beer, S. (1995). Daignosing the System for Organisations. 178.

- Beer, Stafford. (1985). Diagnosing the system for organizations. 152. Available online: https://search.worldcat.org/title/11469665.

- Bohórquez Arévalo, L. E. (2013). La organización empresarial como sistema adaptativo complejo. Estudios Gerenciales, 29, 258–265. [CrossRef]

- Burke, C. M., & Morley, M. J. (2023a). Toward a non-organizational theory of human resource management? A complex adaptive systems perspective on the human resource management ecosystem in (con)temporary organizing. Human Resource Management, 62, 31–53. [CrossRef]

- Burke, C. M., & Morley, M. J. (2023b). Toward a non-organizational theory of human resource management? A complex adaptive systems perspective on the human resource management ecosystem in (con)temporary organizing. Human Resource Management, 62, 31–53. [CrossRef]

- Butko, M. (2019). Innovations in human resources management in Eurointegration conditions: case for Ukrainian agro-industrial complex. Marketing and Management of Innovations, 2, 74–82. [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, P., & Tavis, A. (2018, April). HR Goes Agile. Available online: https://hbr.org/2018/03/hr-goes-agile.

- Checkland, P., & Scholes, J. (1999). Soft systems methodology in action. Systems Research and Behavioral Science Syst. Res, 17, 11–58. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=mbmGEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP6&dq=Checkland,+P.+(1999).+&ots=bW_lnZajlK&sig=ZpQrfrCcKAASC7tA9Pc7BjGLRII.

- Chen, L., Zheng, W., Yang, B., & Bai, S. (2016). Transformational leadership, social capital and organizational innovation. Leadership and Organization Development Journal, 37, 843–859. [CrossRef]

- Colbert, B.A. (2004). The Complex Resource-Based View: Implications for Theory and Practice in Strategic Human Resource Management. The Academy of Management Review, 29, 341. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J., & Creswell, J. (2017). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Available online: https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=335ZDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT16&ots=YEuWPIAnvO&sig=0lUAMXlHO-8RzSwbwg1_gOP0fj8.

- De Cieri, H., & Lazarova, M. (2021). “Your health and safety is of utmost importance to us”: a review of research on the occupational health and safety of international employees. Human Resource Management Review, 31, 100790. [CrossRef]

- Delery, J. E., & Roumpi, D. (2017). Strategic human resource management, human capital and competitive advantage: is the field going in circles? Human Resource Management Journal, 27, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A., & Porter, T. (2011). Sustainability, complexity and learning: Insights from complex systems approaches. Learning Organization, 18, 54–72. [CrossRef]

- Falletta, S. V., & Combs, W. L. (2020). The HR analytics cycle: a seven-step process for building evidence-based and ethical HR analytics capabilities. Journal of Work-Applied Management, 13, 51–68 seven-step process for building evidence-based and ethical HR analytics capabilities. [CrossRef]

- Golinelli, G. M., Pastore, A., Mauro, G., Massaroni, E., Gatti, M., & Vagnani, G. (2002). The firm as a viable system: managing inter-organisational relationships. Researchgate.NetGM Golinelli, A Pastore, M Gatti, E Massaroni, G VagnaniSinergie Italian Journal of Management, 2011•researchgate.Net. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alberto-Pastore/publication/265361065_The_firm_as_a_viable_system_Managing_interorganisational_relationships/links/54b4debd0cf26833efd03a0c/The-firm-as-a-viable-system-Managing-interorganisational-relationships.pdf.

- Guzzo, R. A., Fink, A. A., King, E., Tonidandel, S., & Landis, R. S. (2015). Big data recommendations for industrial-organizational psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 8, 491–508. [CrossRef]

- Holland, J. H. (1995). Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity. Available online: https://philpapers.org/rec/HOLHOH.

- Holland, J.H. (2015). Complex Adaptive Systems. Source: Daedalus, 121, 17–30.

- Hoverstadt, P. (2020). The Viable System Model. Systems Approaches to Making Change: A Practical Guide, 89–138. [CrossRef]

- Huemann, M. (2016). Human resource management in the project-oriented organization: Towards a viable system for project personnel. Human Resource Management in the Project-Oriented Organization: Towards a Viable System for Project Personnel, 1–172. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M. (2003). Systems Thinking: Creative Holism for Managers.

- Jiang, K., Lepak, D. P., Hu, J., & Baer, J. C. (2012a). How Does Human Resource Management Influence Organizational Outcomes? A Meta-analytic Investigation of Mediating Mechanisms. 55, 1264–1294. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K., Lepak, D. P., Hu, J., & Baer, J. C. (2012b). How Does Human Resource Management Influence Organizational Outcomes? A Meta-analytic Investigation of Mediating Mechanisms. 55, 1264–1294. [CrossRef]

- Kauffman, S.A. (1995). At home in the universe : the search for laws of self-organization and complexity. 321. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/At_Home_in_the_Universe.html?hl=es&id=o-Owb5IDkSQC.

- Lechler, R. C., Lehner, P., Röösli, F., & Huemann, M. (2022). The project-oriented organisation through the lens of viable systems. Project Leadership and Society, 3, 100072. [CrossRef]

- Lepak, D. P., Liao, H., Chung, Y., & Harden, E. E. (2006). A Conceptual Review of Human Resource Management Systems in Strategic Human Resource Management Research. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 25, 217–271. [CrossRef]

- Marler, J. H., & Boudreau, J. W. (2017). An evidence-based review of HR Analytics. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28, 3–26. [CrossRef]

- McKelvey, B. (1999). Complexity Theory in Organization Science: Seizing the Promise or Becoming a Fad? Emergence, 1, 5–32. [CrossRef]

- McMackin, J., & Heffernan, M. (2021). Agile for HR: Fine in practice, but will it work in theory? Human Resource Management Review, 31. [CrossRef]

- Midgley, G., Cavana, R. Y., Brocklesby, J., Foote, J. L., Wood, D. R. R., & Ahuriri-Driscoll, A. (2013). Towards a new framework for evaluating systemic problem structuring methods. European Journal of Operational Research, 229, 143–154. [CrossRef]

- Midgley, G., & Lindhult, E. (2021). A systems perspective on systemic innovation. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 38, 635–670. [CrossRef]

- Miltleton-kelly, E. (2003). Complex sytems and evolutionary perspectives on organizations the application of complexity theory to organisations. Available online: http://library.stik-ptik.ac.id/detail?id=35703&lokasi=lokal.

- Nicolis, G., & Prigogine, I. (1989). Exploring Complexity: An Introduction. Available online: https://philpapers.org/rec/NICECA.

- Nuis, J. W., Peters, P., Blomme, R., & Kievit, H. (2021). Dialogues in Sustainable HRM: Examining and Positioning Intended and Continuous Dialogue in Sustainable HRM Using a Complexity Thinking Approach. Sustainability 2021, Vol. 13, Page 10853, 13, 10853. [CrossRef]

- Ontrup, G., Schempp, P. S., & Kluge, A. (2021). Choosing the right (HR) metrics : digital data for capturing team proactivity and determinants of content validity. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness: People and Performance, 9.

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., Mcdonald, S., … Mckenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372. [CrossRef]

- Prigogine, I., & Stengers, I. (2018). Order out of chaos: Man’s new dialogue with nature. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=gOdOEAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR11&dq=Prigogine,+I.,+%26+Stengers,+I.+(2018).+Order+out+of+chaos:+Man%27s+new+dialogue+with+nature.+Verso.&ots=wBZajGmoF-&sig=_hDDtlZUPH4y9ZIybfQnvEkam-0.

- Ramezan, M. (2011). Intellectual capital and organizational organic structure in knowledge society: How are these concepts related? International Journal of Information Management, 31, 88–95. [CrossRef]

- Senge, P. (2005). La Quinta Disciplina en la Práctica: Estrategias y Herramientas para la Organización Abierta al Arbitraje. La Quinta Disciplina En La Práctica, 1–593. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/La_Quinta_Disciplina_en_la_Pr%C3%A1ctica.html?hl=es&id=h4Qfp7CkSCIC.

- Snell, Scott., Morris, S. S. ., García Álvarez, Consuelo., Torres Carrasco, Ruth., García Bencomo, M. I. ., Mora Basurto, Guillermina., Chávez Acevedo, Miguel., & Chruden, H. J. . (2020). Administración de recursos humanos. 576. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Administraci%C3%B3n_de_recursos_humanos.html?hl=es&id=gR0lzgEACAAJ.

- Sparrow, Paul., Brewster, Chris., & Chŏng, C. (2017). Globalizing human resource management. Routledge. Available online: https://www.routledge.com/Globalizing-Human-Resource-Management/Sparrow-Brewster-Chung/p/book/9781138950696.

- Stacey, R. D. (1995). The science of complexity: An alternative perspective for strategic change processes. Strategic Management Journal, 16, 477–495. [CrossRef]

- Tate, M., Furtmueller, E., & Wilderom, C. P. M. (2013). Localising versus standardising electronic human resource management: Complexities and tensions between HRM and IT departments. European Journal of International Management, 7, 413–431. [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 1319–1350. [CrossRef]

- Truss, C. (2001). Complexities and Controversies in Linking HRM with Organizational Outcomes. Journal of Management Studies, 38, 1121–1149. [CrossRef]

- Vesterby, V. (2019). The Intrinsic Nature of Emergence—With Illustrations. [CrossRef]

- Wilber, Ken. (1996). A brief history of everything (1st ed.). Shambhala. Available online: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/40363634-a-brief-history-of-everything.

- Wollersheim, J., & Heimeriks, K. H. (2016). Dynamic Capabilities and Their Characteristic Qualities: Insights from a Lab Experiment. Organ. Sci., 27, 233–248. [CrossRef]

- Wright, P. M., & Ulrich, M. D. (2017). A Road Well Traveled: The Past, Present, and Future Journey of Strategic Human Resource Management. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4, 45–65. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).