Submitted:

29 September 2024

Posted:

11 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

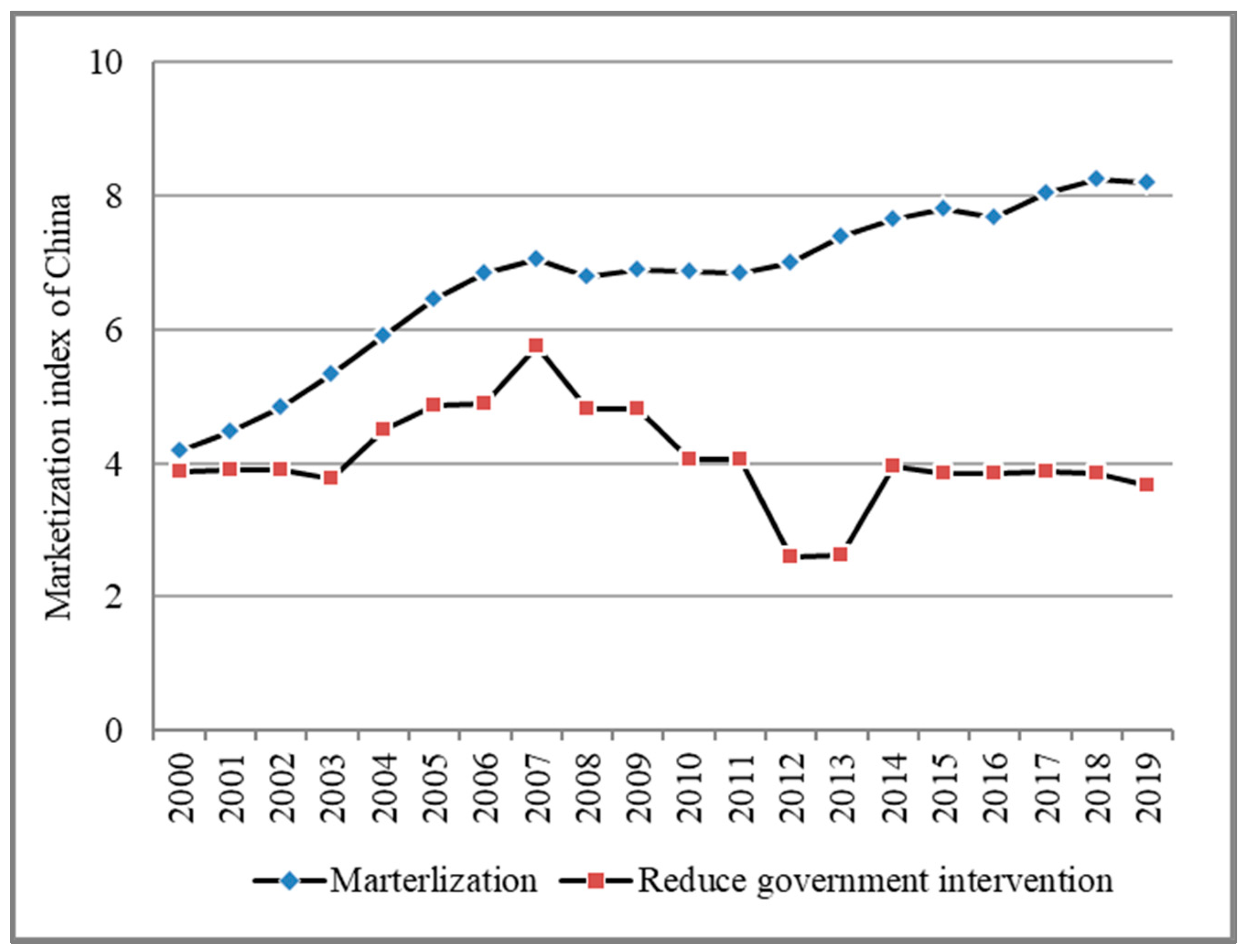

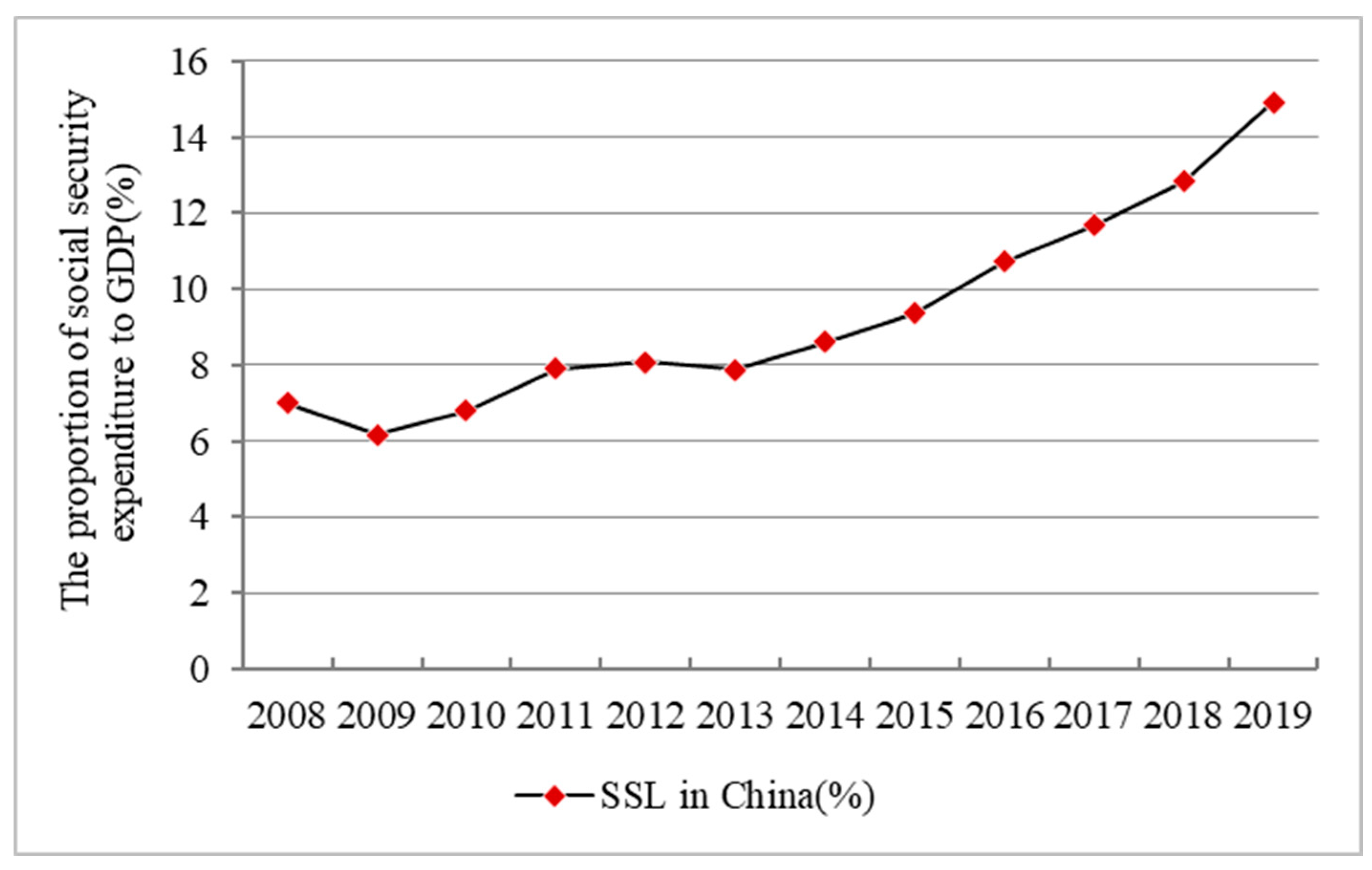

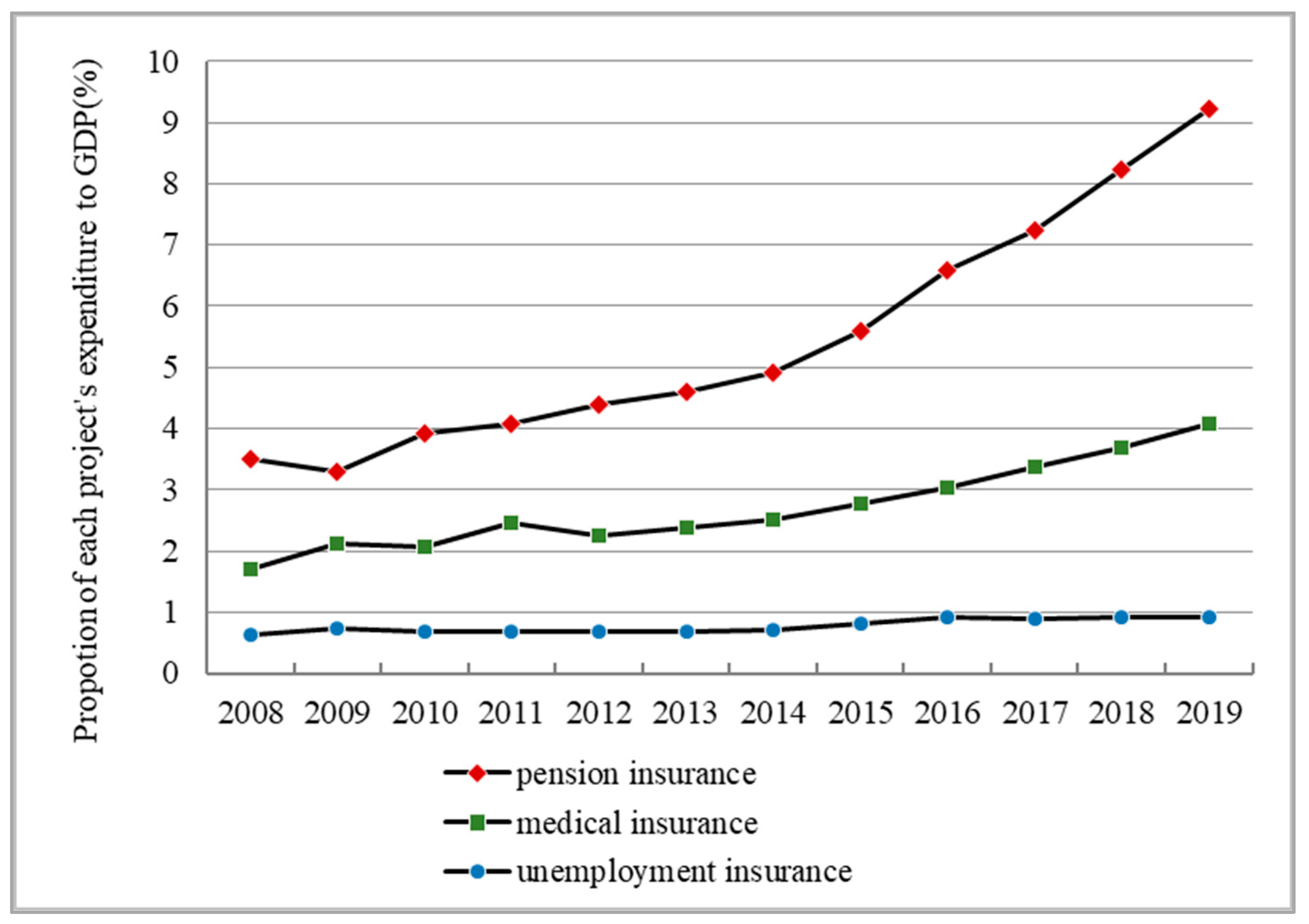

1.1. Social Security Level (SSL) in China

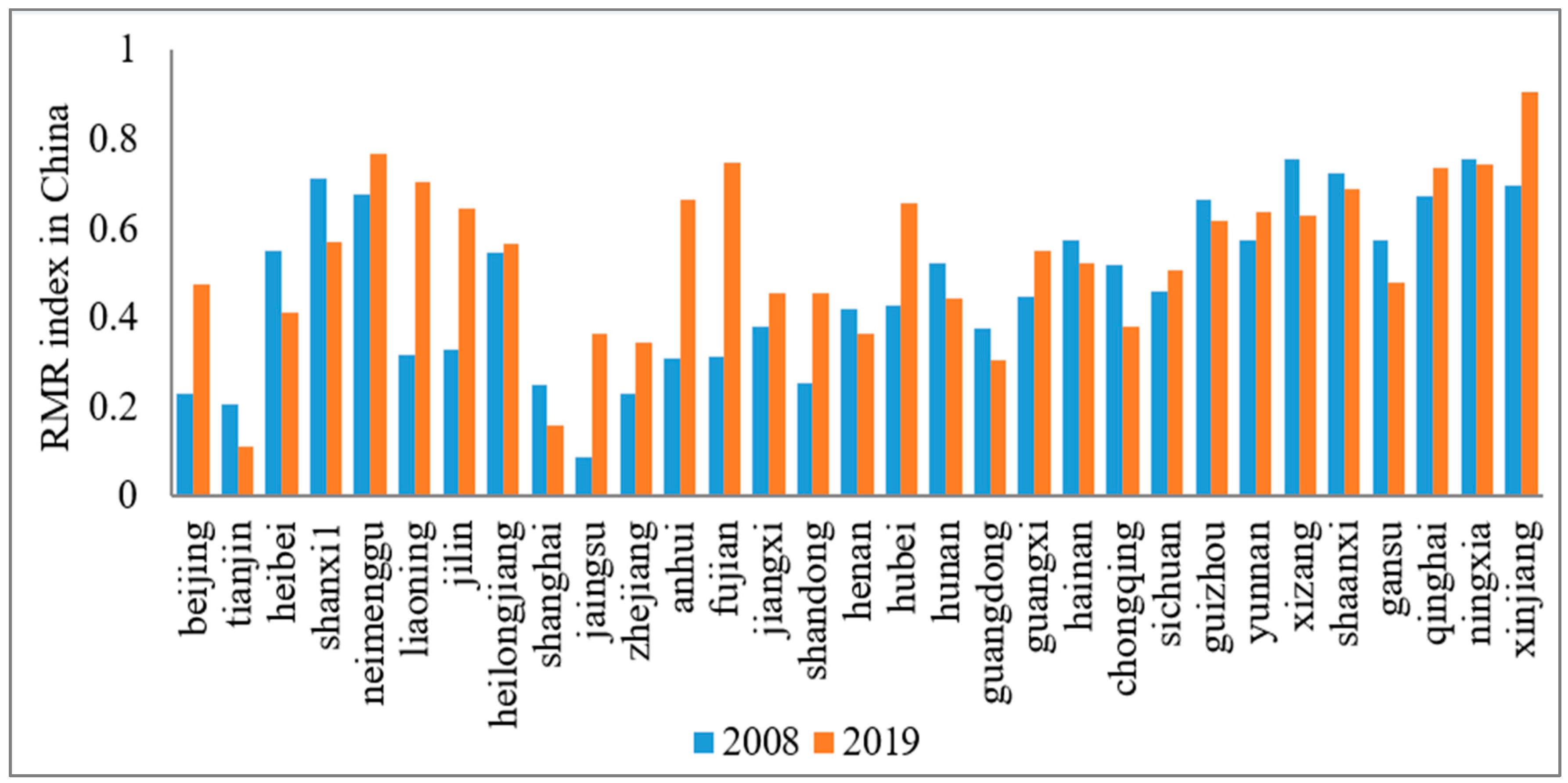

1.2. Relaxation of Market Regulation (RMR) in China

1.3. The Impact of RMR on SSL: Pros and Cons

1.4. Aims of This Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Variable and Measurement

2.3. Models

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Impact of RMR on SSL

3.2. Robustness Test

3.3. Mediation Analysis

3.4. Further Discussion: Why Didn’t Social Security Equity Play a Mediating Role?

3.5. Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng,G.C. Forty Years of Social Insurance in China (1978—2018)——Institutional Transformation, Path Selection and Chinese Experience. Teaching and Research, 2018, 11, 5-15. http://jxyyj.ruc.edu.cn/EN/Y2018/V52/I11/5.

- Mu, H.Z. Research on the Optimal Level of Social Security. Economic Research, 1997, 2, 56-63.

- Cai, Y.; Cheng, Y. Pension reform in China: Challenges and opportunities. China’s Economy: A Collection of Surveys, 2015, 45-62. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Walker, A. Pension system reform in China: Who gets what pensions? Social Policy & Administration, 2018, 52(7), 1410-1424. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Liu, C.; Guan, X., et al. China’s rapidly aging population creates policy challenges in shaping a viable long-term care system. Health Affairs, 2012, 31(12), 2764-2773. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W. The impacts of health insurance on health care utilization among the older people in China. Social science & medicine, 2013, 85, 59-65. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, J.; Hu, S., et al. The primary health-care system in China.The Lancet, 2013, 390, 2584-2594. [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.; Wang, X.L.; Zhu, H.P. NERI index of Marketlization of China’s Provinces 2021 Report. Economic and Science Press: Beijing, China, 2021. cser.org.cn.

- Eichhorst, W.; Marx, P.; Wehner, C. Labor market reforms in Europe: towards more flexicure labor markets? Journal for labour market research, 2017, 51,1-17. [CrossRef]

- Bothfeld, S.; Rosenthal, P. The end of social security as we know it–The Erosion of status protection in German labour market policy. Journal of Social Policy, 2018, 47(2), 275-294. [CrossRef]

- Kongtip, P., Nankongnab, N.; Chaikittiporn, C., et al. Informal workers in Thailand: occupational health and social security disparities. New Solutions: A Journal of Environmental and Occupational Health Policy, 2015, 25(2), 189-211. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L. A. Official Promotion Tournament and Competitive Impulse. People’s Forum, 2010, 15, 26-27. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Weingast, B. R. Federalism as a commitment to preserving market incentives. Journal of Economic perspectives, 1997, 11(4), 83-92. [CrossRef]

- Fu, M. J.; Zhang, P. Economic Growth in the Reform of Socialist Market Economy System: A Political Economy Exploration. Economic Research, 2022, 57(7), 189-208.

- Li, H.; Zhou, L. A. Political turnover and economic performance: the incentive role of personnel control in China. Journal of public economics, 2005, 89(9-10), 1743-1762. [CrossRef]

- Lo, D. China confronts the Great Recession: ‘rebalancing’ neoliberalism, or else? Emerging Economies during and after the Great Recession, 2016, 232-269. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137485557_7.

- Bardhan, P. The Chinese governance system: Its strengths and weaknesses in a comparative development perspective. China Economic Review, 2020, 61, 101430. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W. Transplanting antitrust in China: economic transition, market structure, and state control. U. Pa. J. Int’l L., 2010, 32, 643. https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub/221/.

- Huang, G. ; Cai. Z. Understanding social security development: Lessons from the Chinese case. SAGE Open, 2021, 11(3),1-13. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. The politics of social welfare reform in urban China: Social welfare preferences and reform policies. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 2013, 18(1), 61-85. [CrossRef]

- Feng, H. Public Interest, Government Regulation, and Substantive Rule of Law. Political and Legal Forum, 2024, 42(02), 132-141.

- Xing, H. F. On the Guarantee Responsibility of Government Purchasing Public Services . Legal and Business Research, 2022, 39(01), 144-158. 10.16390/j.cnki.issn1672-0393.2022.01.011.

- Haveman; Heather, A., et al. The dynamics of political embeddedness in China. Administrative Science Quarterly , 2017, 62(1), 67-104. [CrossRef]

- Barbieri, P.; Bozzon, R. Welfare, labour market deregulation and households’ poverty risks: An analysis of the risk of entering poverty at childbirth in different European welfare clusters. Journal of European Social Policy, 2016, 26(2), 99-123. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. Housing, urban growth and inequalities: The limits to deregulation and upzoning in reducing economic and spatial inequality. Urban Studies, 2020, 57(2), 223-248. [CrossRef]

- Enev, P. Monopoly and competition on Bulgarian pension market. Trakia Journal of Sciences, 2015, 13(1), 207-211. [CrossRef]

- Hastings, J.; Hortaçsu, A.; Syverson, C. Sales force and competition in financial product markets: the case of Mexico’s social security privatization. Econometrica, 2017, 85(6),1723-1761. [CrossRef]

- Heidenheimer, A. J. Education and social security entitlements in Europe and America. In Development of welfare states in Europe and America. Routledge, Arnold J. Heidenheimer, Publisher: Routledge, USA, 2017.

- Liebman, J. B.; Luttmer, E. F. P. Would people behave differently if they better understood social security? Evidence from a field experiment. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2015, 7(1),275-299. [CrossRef]

- Von Mises, L. Omnipotent government. Read Books Ltd. ,2011.

- Lin, J. Y. New structural economics: A framework for rethinking development. The World Bank Research Observer, 2011, 26(2), 193-221. [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.Z. Research on the Optimal Level of Social Security. Economic Research, 1997, 2, 56-63.

- Gao, L. The Level and Adequate Selection of Social Security in Shandong Province. Population and Economics, 2002, 05, 64-72.

- Guo, G. Z.; Yang, C. Y. The Study on the Fiscal Responsibility of Local Social Security and Its Relationship with Economic Development: Based on Panel Data Analysis of 31 Provinces in China. Northwest Population, 2010, 31(06), 1-4.

- Liu, L. L.; Ren, B. The Impact of Official Exchanges on the Development of Social Security Undertakings: Empirical Evidence from Exchanges between Provincial Governors and Provincial Party Secretaries. Southern Economic Journal, 2015, 10, 64-84. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Yang, Y.; Yang, Y., et al. Different impact on health outcomes of long-term care insurance between urban and rural older residents in China. Scientific Reports, 2023, 13(1),253. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-27576-6.

- Chirinko, R. S.; Wilson, D. J. Tax competition among US states: Racing to the bottom or riding on a seesaw. Journal of Public Economics, 2017, 155, 147-163. [CrossRef]

- Tang, R; Liu, H.Q. From GDP Competition to Binary Competition: The Logic of Change in Local Government Behavior in China. Journal of Public Administration, 2012, 1, 9-16.

- Wen, Z.L.; Zhang, L.; Hou, J.T., et al. Testing Procedures for Mediation Effects and Their Applications. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 2004, 5, 614-620.

- Jiang, T. Mediation and Moderation Effects in Empirical Research on Causal Inference. China Industrial Economics, 2022, 5, 100-120. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. The Legal Route of Government Regulation Reform under the Simplification of Administration and Delegation of Power. Law Review, 2016, 2, 28-41.

- Eichhorst, W.; Marx, P.; Wehner, C. Labor market reforms in Europe: towards more flexicure labor markets [J]. Journal for labour market research, 51, 1-17(2017). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12651-017-0231-7.

- Zhu, Q. W. Understanding the New Dimension of Public Administration: Interaction between Government and Society. China Public Administration, 2020, 3, 45-51.

- Huang, G.; Cai, Z. Understanding social security development: Lessons from the Chinese case[J]. SAGE Open, 2021, 11(3), 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X. The politics of social welfare reform in urban China: Social welfare preferences and reform policies. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 2013, 18(1), 61-85. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11366-012-9227-x. [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, J.; Geys, B.; Heyndels, B., et al. Competition in the political arena and local government performance. Applied Economics, 2014, 46(19), 2264-2276. [CrossRef]

- Boyne, G. A. Competition and local government: A public choice perspective [J]. Urban Studies, 33(4-5), 703-721(1996).

- Li, L. Government Regulation and Benchmark Competition: Governance Path Analysis of Medical Insurance Payment Reform. Comparative Economic & Social Systems, 2021, 03, 80-88 .

- Li, L.; Yu, Q. Government Regulation, Benchmark Competition, and Medical Insurance Payment Reform. Chinese Public Administration, 2022, 10, 90-98.

- Gebel, M.; Giesecke, J. Does deregulation help? The impact of employment protection reforms on youths’ unemployment and temporary employment risks in Europe. European Sociological Review, 2016, 32(4), 486-500. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G. Regulation and Entrepreneurship: Micro Evidence from China. Management World, 2015, 05, 89-99+187-188. [CrossRef]

- Heyes, J.; Lewis, P. Employment protection under fire: Labour market deregulation and employment in the European Union. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 2014, 35(4), 587-607. [CrossRef]

- Mai, W.; Hamid, N. Short-selling deregulation and corporate social responsibility of tourism industry in China. E3S Web of Conferences. EDP Sciences, 2021, 251,03032. [CrossRef]

- Rubery, J.; Piasna, A. Labour market segmentation and deregulation of employment protection in the EU. In Myths of employment deregulation: how it neither creates jobs nor reduces labour market segmentation. Brussels: ETUI, 2017, 43-60. http://pinguet.free.fr/etuideregula.pdf#page=42.

- Yaprak, A. Market entry barriers in China: A commentary essay. Journal of Business Research, 2012, 65(8), 1216-1218. [CrossRef]

- Vergeer, R.; Kleinknecht, A. The impact of labor market deregulation on productivity: a panel data analysis of 19 OECD countries (1960-2004). Journal of Post Keynesian Economics, 2010, 33(2), 371-408. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.2753/PKE0160-3477330208.

- Findling, L.; Arruñada, M.; Klimovsky E. Deregulation and equity: the Obras Sociales reconversion process in Argentina. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 2002, 18, 1077-1086. [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhou, Z.; Cao, D., et al. Did the integrated urban and rural resident basic medical insurance improve benefit equity in China.Value in Health, 2022, 25(9), 1548-1558. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, R.; Fang, Y. Effects of urban and rural resident basic medical insurance on healthcare utilization inequality in China. International Journal of Public Health, 2022, 68, 1605521. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Luo, S. Study on the Heterogeneity of Social Security Affecting the Sense of Security of Urban and Rural Residents. Complexity, 2022, 9, 8193726. [CrossRef]

- Stigler, G. J. The Theory of Economic Regulation .Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 1971,2, 3-21.

- Viscusi, W. Kip, Joseph E. Harrington Jr, and David EM Sappington. Economics of regulation and antitrust. MIT press, 2018.

- Meng, Q., et al. Consolidating the social health insurance schemes in China: towards an equitable and efficient health system. The Lancet, 2015, 386(10002), 1484-1492. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dupre, M. E.; Qiu, L. Urban-rural differences in the association between access to healthcare and health outcomes among older adults in China. BMC geriatrics, 2017, 17, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Song, Z.; Zong, Q. Urban-rural inequality of opportunity in health care: evidence from China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2021, 18(15), 7792. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fu, H. China’s health care system reform: Progress and prospects. The International journal of health planning and management, 2017, 32(3), 240-253. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Shi, L.; Tian, F.; et al. Care utilization with China’s new rural cooperative medical scheme: updated evidence from the China health and retirement longitudinal study 2011–2012. International journal of behavioral medicine, 2016, 23, 655-663. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. G.; Vortherms, S. A.; Hong, X. China’s health reform update. Annual review of public health, 2017, 38(1), 431-448. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Krumholz, H. M.; Yip, W.; et al. Quality of primary health care in China: challenges and recommendations. The Lancet, 2020, 395(10239), 1802-1812. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition | Average value |

Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSL | Calculated according to Formula 1, i.e., the ratio of social security expenditure to regional GDP. A higher value indicates a higher SSL; conversely, a lower value indicates a lower SSL.(ssl) | 0.0933 | 0.0433 |

| RMR | Measured based on the index of “reducing intervention in enterprises” in the MICR. A higher value indicates a higher level of RMR; conversely, a lower value indicates a lower level of RMR.(rmr) | 3.8359 | 2.9622 |

| Social security expenditure | The ratio of total social security expenditure to the total population in each province.( expenditure) | 4.4869 | 3.5262 |

| Social security fairness | The ratio of per capita social security benefits for urban employees in each province to per capita social security benefits for urban and rural residents. (fairness) | 23.0786 | 13.4292 |

| Social security efficiency | The ratio of the number of individuals participating in medical, pension, and unemployment insurance in each province to the total population. (efficiency) | 0.6147 | 0.0805 |

| Fiscal freedom | The ratio of general public budget expenditure to revenue in each province. | 2.5971 | 1.9821 |

| Economic growth rate | The annual growth rate of Gross Regional Product (GRP) in each province. | 9.5961 | 2.9551 |

| Elderly dependency ratio | The ratio of the population aged 65 and above to the working-age population in each province. | 13.485 | 3.2527 |

| Internal competition | The ratio of the number of cities to the number of districts and counties in each province. [37] | 0.1179 | 0.0406 |

| Central transfer payments | Measured by the transfer payments from the central government to local governments for social security in each province. [38] | 0.0135 | 0.0263 |

| Variables | OLS | 2SLS | ||

| Model (2) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (2) | |

| Column 1 | Column 2 | Column 3 | Column 4 | |

| rmr | 0.0008(0.0010) | 0.0013**(0.0007) | - | 0.0021***(0.0008) |

| L.rmr | - | - | 0.7541***(0.0435) | - |

| history-rmr | - | - | 0. 0521(0.0324) | - |

| constant | 0.0868***(0.0136) | 0.6640***(0.1417) | 0.3834 (0.7766) | 0.1384***(0.0172) |

| control variables | NO | YES | YES | YES |

| individual effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| annual effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R-squared | 0.5822 | 0.5364 | 0.7758 | 0.7211 |

| estat overid (p) | - | - | - | 0.4628 |

| robust F | - | - | - | 175.741 |

| capacity | 372 | 372 | 341 | 341 |

| Variables | Winsor processing examination | Policy shock examination | |

| Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (2) | |

| Column 1 | Column 2 | Column 3 | |

| rmr | 0.0015***(0.0007) | 0.0022***(0.0008) | 0.0014**(0.0007) |

| policy | - | - | 0.1505***(0.0185) |

| constant | 0 .6651***(0.1417) | 0.1286***(0.0135) | 0.6641***(0.1417) |

| control variables | YES | YES | YES |

| individual effects | YES | YES | YES |

| annual effects | YES | YES | YES |

| R-squared | 0.5358 | 0.7210 | 0.5364 |

| capacity | 372 | 341 | 372 |

| Variables | The Mediating Effect of Social Security Expenditure | The Mediating Effect of Social Security Fairness | The Mediating Effect of Social Security Efficiency | |||

| Model (5) | Model (4) | Model (5) | Model (4) | Model (5) | Model (4) | |

| Column 1 | Column 2 | Column 3 | Column 4 | Column 5 | Column 6 | |

| rmr | 0.2937*** (0.0663) |

0.0002 (0.0006) |

-1.4186*** (0.4467) |

0.0024*** (0.0011) |

0.0033 (0.0031) |

0.0027*** (0.0010) |

| expenditure | - | 0.0066*** (0.0007) |

- | - | - | - |

| fairness | - | - | - | -0.0022*** (0.0002) |

- | - |

| efficiency | - | - | - | - | - | 0.0018 (0.0022) |

| constant | 9.4069*** (1.1656) |

0.0675*** (0.01213) |

8.7550 (11.5655) |

0.1962*** (0.0177) |

0.5890*** (0.0528) |

0.1931*** (0.0213) |

| control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| individual effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| annual effects | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R-squared | 0.4567 | 0.5776 | 0.5589 | 0.6098 | 0.5980 | 0.4998 |

| capacity | 341 | 341 | 248 | 248 | 248 | 248 |

| Variables | Pension fairness | Medical benefit fairness | ||

| Model (3) | Model (3) | Model (3) | Model (3) | |

| Column 1 | Column 2 | Column 3 | Column 4 | |

| rmr | 0.0053***(0.0019) | - | 0.0109 (0.0152) | - |

| rmr-speed | - | 0.0002(0.0131) | - | -0.0299***(0.0133) |

| constant | 0.0301**(0.0015) | 0.1255(0.0992) | 0.2921***(0.1092) | - |

| control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| individual effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| annual effects | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| R-squared | 0.5409 | 0.2209 | 0.2091 | 0.5001 |

| capacity | 372 | 372 | 372 | 372 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).