1. Introduction

Candidiasis is one of the most prevalent infectious diseases that affect the oral mucosa. The primary etiological agent is a yeast-like fungus belonging to the genus

Candida (C.) [

1].

C. albicans is the most frequently isolated species, accounting for 47-84% of fungal infections in the oral cavity [

2]. However, long-term epidemiological studies indicate an increasing prevalence of infections due to other

Candida species, collectively referred to as

non-albicans Candida (NAC). NAC species include, but are not limited to:

C. glabrata,

C. tropicalis,

C. pseudotropicalis,

C. parapsilosis,

C. dubliniensis,

C. guilliermondii,

C. krusei,

C. kefyr, C

. lusitaniae and

C. stellatoidea [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The increasing frequency of NAC isolation can be attributed to several factors, including prolonged exposure to antifungal medications, technological advancements in laboratory diagnostics, climate change, and pandemics. Significant control challenges for these pathogens pertain to their capacity to circumvent the mechanisms of action of diverse drugs, leading to the development of antimycotic resistance, and their ability to evade host immune responses. The environmental pressures resulting from climate change and the ongoing global pandemic have contributed to the isolation of very rare fungal species, including

C. palmioleophila,

C. nivariensis,

C. auris,

C. spencermartinsiae, and

C. quercitrusa,

C. pseudohaemulonii,

C. duobushaemulonii,

C. sphaerica,

C. rugosa,

C. haemulonii,

C. bracarensis, and

C. utilis [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Furthermore, in recent years, there has been an increase in the number of cases of a species of

C. auris, first described in 2009 in Japan, in countries including those in East Asia and Asia Minor, South Africa, the United States, South America, and the United Kingdom. This multidrug-resistant strain is responsible for significant outbreaks of invasive infections, particularly in patients who have received medical care, especially those who have recovered from SARS-CoV-2, those with cancer, and those with intact immune systems. The fungus poses a significant global threat, exhibiting characteristics such as ease of transmission, resistance to antifungal drugs and disinfectants, and a wide range of virulence factors. It causes severe infections with an estimated mortality rate of up to 72% [

13,

14].

C. palmioleophila is another strain that is challenging to identify and is associated with severe endogenous fungal intraocular inflammation [

11]. Additionally,

Candida spp. may be a significant contributor to oral epithelial carcinogenesis, particularly about squamous cell carcinoma, due to their capacity to convert nitrite and nitrate into nitrosamines and produce acetaldehyde [

15]. Additionally, the infection is accompanied by the formation of other substances that promote metaplasia (candelysin, esterase) and morphological alterations in cell structure and genotype, which may further predispose to a precancerous state and/or cancer [

15,

16]. The prevalence of fungal infections affecting the oral mucosa, genitals, and skin, among other sites, has risen globally over the past few decades [

17]. Although candidiasis is often considered a superficial infection affecting only the mucosal surface in dentistry, candidemia represents a significant medical concern, ranking among the most prevalent hospital bloodstream infections (BSIs). It is the most common manifestation of invasive candidiasis, with a mortality rate reaching 50%. In the United States and Europe, bloodstream infections (BSIs) caused by

Candida account for more than 90% of fungal BSIs, ranking fourth and seventh, respectively, among all reported BSIs in these regions. Among neonates, it ranks third [

18,

19]. Furthermore, yeast is capable of tigmotropism, which is the ability to grow directionally in response to contact with a surface. This enables it to invade intravascular spaces and subsequently invade the deep tissues of the patient’s target organs, including the liver, spleen, kidneys, heart, and brain. This can result in life-threatening organ mycoses [

20]. The formation by

C. albicans of an organized multi-strain biofilm on the surface of the mucosa and teeth in conjunction with certain bacteria (e.g.,

Streptococcus (S.) gordonii,

S. salivarius,

S. oralis) is an increasingly well-documented phenomenon. Additionally, the presence of multiple NAC strains has been observed within this biofilm. These strains are inherently less sensitive and/or resistant to common antimicrobials, primarily due to morphological alterations in the cell wall, including reduced ergosterol levels and altered beta-glucan structure [

21]. Pharmacological inconsistencies, including the administration of antifungal therapy that is insufficient in duration and the utilization of suboptimal sub-threshold doses of pharmaceutical agents, have been identified as contributing factors to the suboptimal outcomes observed in candidiasis therapy. This has led to the necessity for the concurrent administration of multiple antifungal agents at elevated doses, which has, in turn, resulted in a heightened propensity for recurrent episodes of infection [

22,

23,

24,

25]. This situation is prompting the search for new antifungal drugs and alternative therapies that could complement or even replace conventional drug therapy. Alternative methods include pharmacotherapy, which encompasses the use of essential oils, plant extracts, propolis solution, probiotics, colloidal solutions of nano-metals (silver, copper, gold), and methods such as antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) and ozone therapy [

18,

26,

27,

28,

29]. The objective of this study was to retrospectively evaluate the prevalence and drug susceptibility of Candida in patients of the Department of Periodontal and Oral Mucosa Diseases in Zabrze, Silesian Medical University in Katowice, who had been diagnosed with oral mucosa candidiasis between 2018 and 2022. Additionally, the study aimed to analyze the risk factors that predispose to its development.

2. Materials and Methods

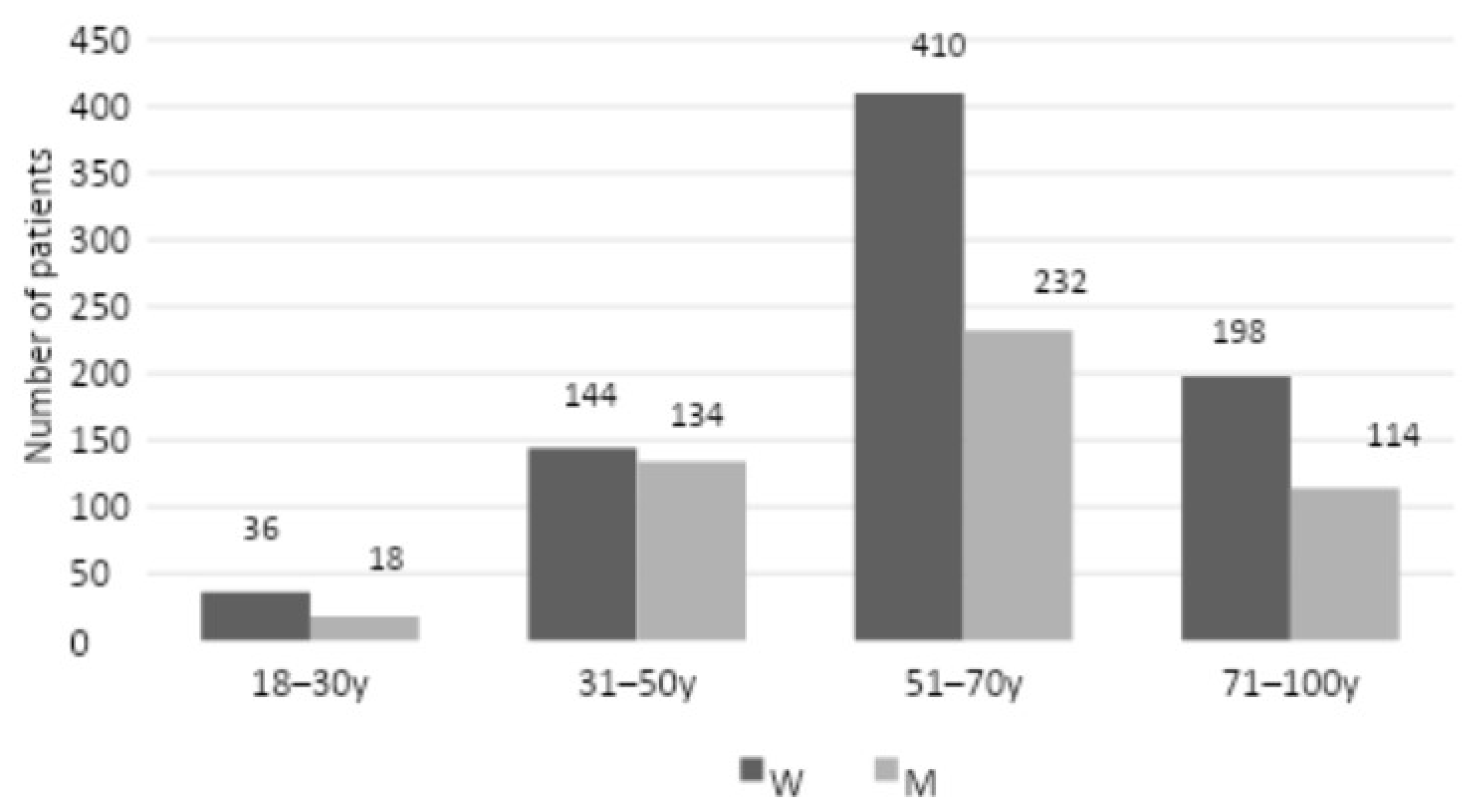

The study included 1,286 patients from the Department of Periodontal and Oral Mucosa Diseases at Silesian Medical University in Katowice who were admitted between 2018 and 2022 with an initial clinical diagnosis of oral mucosal candidiasis. The study group comprised 788 women and 498 men, with an age range of 18 to 100 years for the former and 18 to 90 years for the latter. The patients were divided into four age groups, with 18-30 years comprising 36 women and 18 men, 31-50 years comprising 144 women and 134 men, 51-70 years comprising 410 women and 232 men, and 71-100 years comprising 198 women and 114.

A retrospective analysis of the medical records of the patients was conducted, with particular attention paid to the data from the subject and the physical examination that could potentially predispose to candidiasis. The following information was subjected to analysis according to the following criteria:

1. personal information: age, gender,

2. data on candidiasis: the Candida strain(s) isolated from the oral mucosa, the primary or secondary nature of the condition (number of recurrences of candidiasis in the last 5 years), the location of the infection found in the oral cavity (tongue, palate, cheeks, denture plate), the coexistence of other foci of candidiasis (skin and its appendages, other mucous membranes), the coexistence of another infection of the oral mucosa (bacterial/viral),

3. data on the therapy of candidiasis: sensitivity of the strain(s) to the basic antifungal drugs according to the antimycogram, the way of conducted therapy (topical and/or systemic - names of preparations, time of application),

4. concomitant local factors predisposing to mycosis fungoides: use of removable dentures (24/7/removed overnight), duration of use of last set of dentures), nicotinis

5. (number of cigarettes smoked, a form of tobacco smoked (traditional, self-rolled, slim, e-cigarettes), duration of habit), poor oral hygiene (API Lange et al. ), reduced saliva secretion (mirror test, resting/stimulated sialometry),

6. Systemic comorbidities: diseases and conditions with potential immune deficiencies (with details on diabetes mellitus (hyperglycemia as defined by HbA1c ratio), systemic immunosuppressive therapy, glucocorticosteroid therapy (systemic/inhaled), systemic chemotherapy, radiation therapy administered in the head and neck region, AIDS/HIV, antibiotic therapy in the 6 months preceding the diagnosis of fungal infection, and other immune deficiency diseases - neutropenia)

2.1. The Process of Diagnosing Patients

The rationale for referring the patient for an objective diagnosis was based on an analysis of the patient’s history and the clinical presentation of the lesions. Following the classification proposed by Holmstrup et al., oral candidiasis can manifest in several different forms [

30,

31]. The specific form of candidiasis was identified based on the presence of distinctive characteristics.

Primary oral candidiasis:

1.1. Pseudomembranous candidiasis:

1.1.1. Acute - is characterized by the appearance of white or cream-colored papules or plaques on the oral mucosa. These lesions are associated with the substrate and have a consistency that resembles clotted or sugared milk. The white plaques are composed of exfoliated epithelial cells, immune response cells, and yeast mycelium. The efflorescences can be removed by rubbing them off, for example, with gauze. The remaining surface is red and partially devoid of epithelium, with bleeding points.

1.1.2. Chronic – is characterized by the presence of white or cream-colored lumps or plaques on the oral mucosa. These lesions often bleed when attempts are made to remove them and have a tendency to persist for an extended period

1.2. Erythematous candidiasis:

1.2.1.Acute - manifests as smooth, red patches on the hard or soft palate, the back of the tongue, or the mucous membrane of the cheeks. The epithelium exfoliates, and erosions and cracks may develop. Subjective symptoms include a burning sensation in the mouth or on the tongue, mucosal tenderness, and increased sensitivity to various foods, particularly spicy foods.

1.2.2. Chronic - occurs in patients using removable prosthetic restorations. The mucosal alterations that can be observed are typically confined to the region encompassed by the denture plate. Such lesions are most frequently observed on the palate, though they may also manifest in the mandible. The lesions present as diffuse erythematous patches, with abraded and tender epithelium. Subjective discomfort may be absent in some patients but burning or pain may be reported.

1.3. Hyperplastic candidiasis (fungal leukoplakia) – is characterized by the emergence of white, firmly adherent patches or plaques on the mucosa that cannot be removed. Such lesions are typically bilateral and distributed on the buccal mucosa in the vicinity of the corners of the mouth, the vermilion border of the lips, and the dorsum of the tongue.

1.4. Changes associated with Candida infection:

1.4.1. Prosthetic stomatitis is characterized by the presence of diffuse erythematous patches in the area of contact between the denture and the oral mucosa.

1.4.2. Chronic erythematous candidiasis is often accompanied by inflammation of the angles of the lips. This occurs in individuals who use prosthetic restorations or possess reduced stenosis height. In such cases, the vertical dimension of the face is diminished, and wrinkles emerge along the nasolabial folds and around the corners of the mouth. The typical symptoms include redness, and cracking of the skin and mucous membrane around the corners of the mouth, often accompanied by bleeding while speaking and eating. In more advanced lesions, yellowish scabs may appear.

1.4.3. Rhomboiditis of the middle part of the tongue presents clinically as a hypertrophic or atrophic rhomboid-shaped area in the mid-dorsal part of the tongue. In most cases, central atrophy of the papillae of the tongue does not result in subjective symptoms. However, it is frequently associated with chronic Candida infection

1.4.4. Linear reddening of the gingiva manifests as linear erythema 2-3 mm wide of the marginal gingiva along with petechiae/diffuse erythematous lesions in the zone of the attached gingiva (possibly accompanied by bleeding).

1.5. Diseases with keratinization disorders infected by Candida fungi:

1.5.1. Leukoplakia

1.5.2. Lichen planus

1.5.3. Lupus erythematous

The clinical diagnosis of oral candidiasis was made based on the quantitative and qualitative results of the mycological examination of the biological material collected in the form of a swab (strong rubbing) from the oral mucosa, prosthesis, or young. The material was collected from the patient and the examination was performed by a diagnostician at an external, certified center that has a long-standing collaborative relationship with our department (Central Analytical Laboratory, Piastowska 11, 41-800 Zabrze). The collected material was sown simultaneously on two media: the first was Sabouraud’s with chloramphenicol (BTL Sp. z o. o., Lodz, Poland), which was used to determine the genus of fungi; the second was BRILLIANCE™ CANDIDA AGAR chromogenic mixture (Argenta Sp. z o. o., Poznan, Poland), which was employed for species differentiation. The samples were incubated at 32°C for a period of 24 to 48 hours under aerobic conditions. The quantitative interpretation was based on the following scheme:

0 – no fungal growth,

1 – poorly abundant growth (+) - single colonies (from 1 to 10 colonies),

2 – medium abundant growth (+ +) - from 11 to 30 colonies,

3 – abundant growth (+ + +) - from 31 to 100 colonies,

4 – growth very abundant, sink (+ + + +) - over 100 colonies.

The susceptibility of individual fungal strains to various antifungal drugs was evaluated using the Candifast® test (ELITech Group SAS, Puteaux, France). Identification was based on observation of the growth of Candida strains in the presence of antifungal drugs, including amphotericin B (5 µg/mL), nystatin (200 µg/mL), flucytosine (35 µg/mL), econazole (16 µg/mL), ketoconazole (16 µg/mL), miconazole (16 µg/mL), and fluconazole (16 µg/mL). The indicator employed was phenol red. A yellow-orange coloration indicated that the test strain could grow in the presence of an antifungal agent, thereby confirming drug susceptibility. Conversely, a red-pink color change confirmed the strain’s drug resistance. All steps, including visual observation of the color changes and interpretation of the results from the provided color chart performed in according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

The results of the mycological examination, as indicated by the antimycogram, are as follows:

type of test

the place where the materials were taken

isolated strain(s)

quantitative evaluation of the growth of the strain(s)

assessing the drug susceptibility of the strain(s) to 7 antimycotics

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica v. 7.1 PL from StatSoft. A significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted. A chi-square test of independence supplemented by Yates correction where necessary was used.

3. Results

The medical records of a total of 1,286 patients admitted to the Department of Periodontal and Oral Mucosa Diseases at Silesian Medical University in Katowice between 2018 and 2022 with clinical symptoms indicative of oral mucosal candidiasis were analyzed. A summary of the demographic characteristics of the patients is presented in

Figure 1.

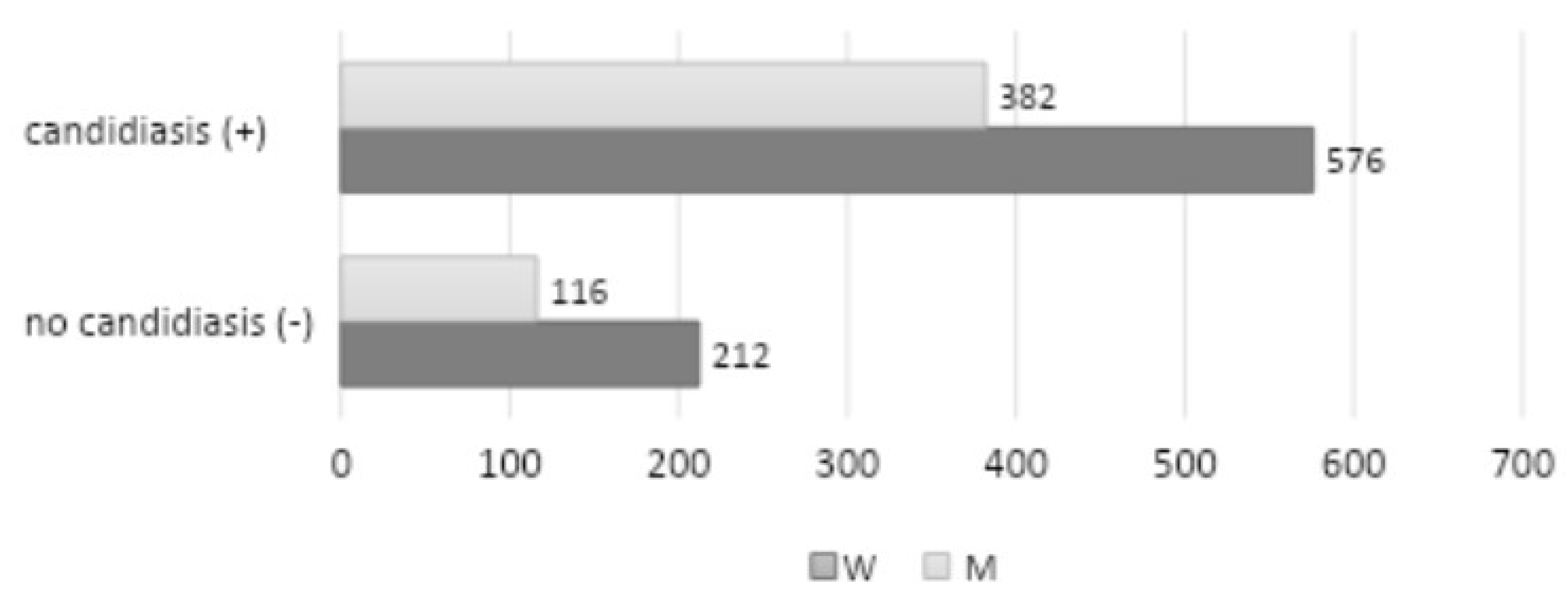

A review of personal data by age group and gender distinction revealed that the largest representation among patients with clinical symptoms of candidiasis was observed in the 51-70 age range (642 patients, 410 women, and 232 men), followed by the 71-100 age range (312 patients, 198 women, and 114 men). The 31-50 age range exhibited the lowest representation (278 patients, 102 women, and 102 men), while the 18-30 age range demonstrated the least representation (54 patients, 36 women and 18 men). Among the 1,286 patients examined, a positive mycological examination (quantitative interpretation: 1-4) was observed in 958 patients (576 women and 328 men) (

Figure 2).

A five-year retrospective analysis revealed that 1,102 cases of oral candidiasis had been confirmed through mycological examination.

Table 1 illustrates the distribution of various

Candida strains.

The highest percentage of identified strains was

C. albicans (736 infections, representing 66.79% of the total), followed by

C. glabrata (108 infections, 9.80%),

C. tropicalis (80 infections, 7.26%), and other strains. The remaining identified strains included

C. krusei (49 infections, 4.45%),

C. dubliniensis (44 infections, 3.99%),

C. kefyr (41 infections, 3.72%),

C. lusitaniae (19 infections, 1.72%), and

C. parapsilosis (16 infections, 1.45%).

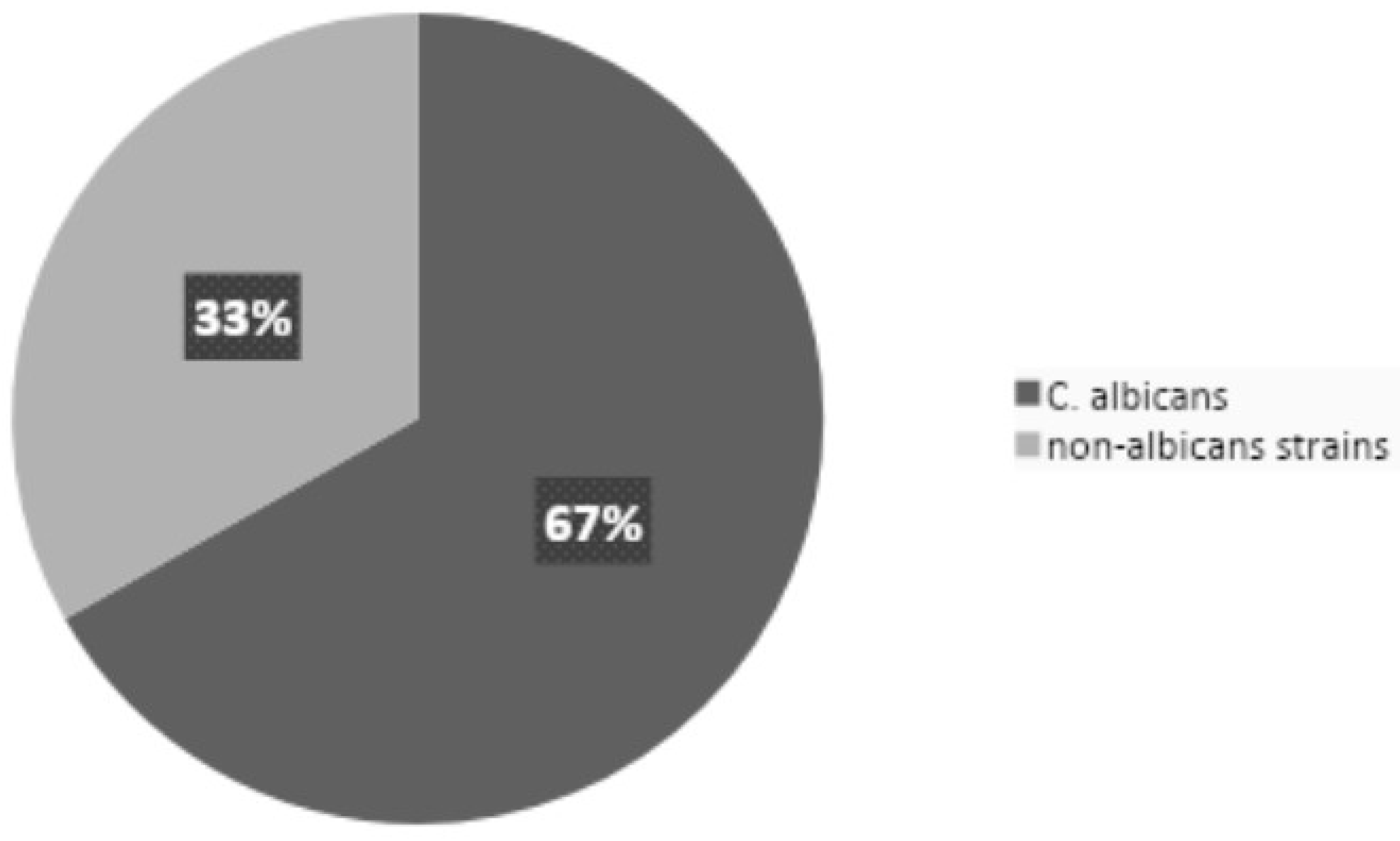

Figure 3 illustrates the proportion of NAC strains relative to

C. albicans.

The prevalence of NAC infections was found to be 33.21%. Additionally, nine infections (0.82%) were identified, representing rare strains such as

C. stellatoidea,

C. palmioleophila, and

C. nivariensis.

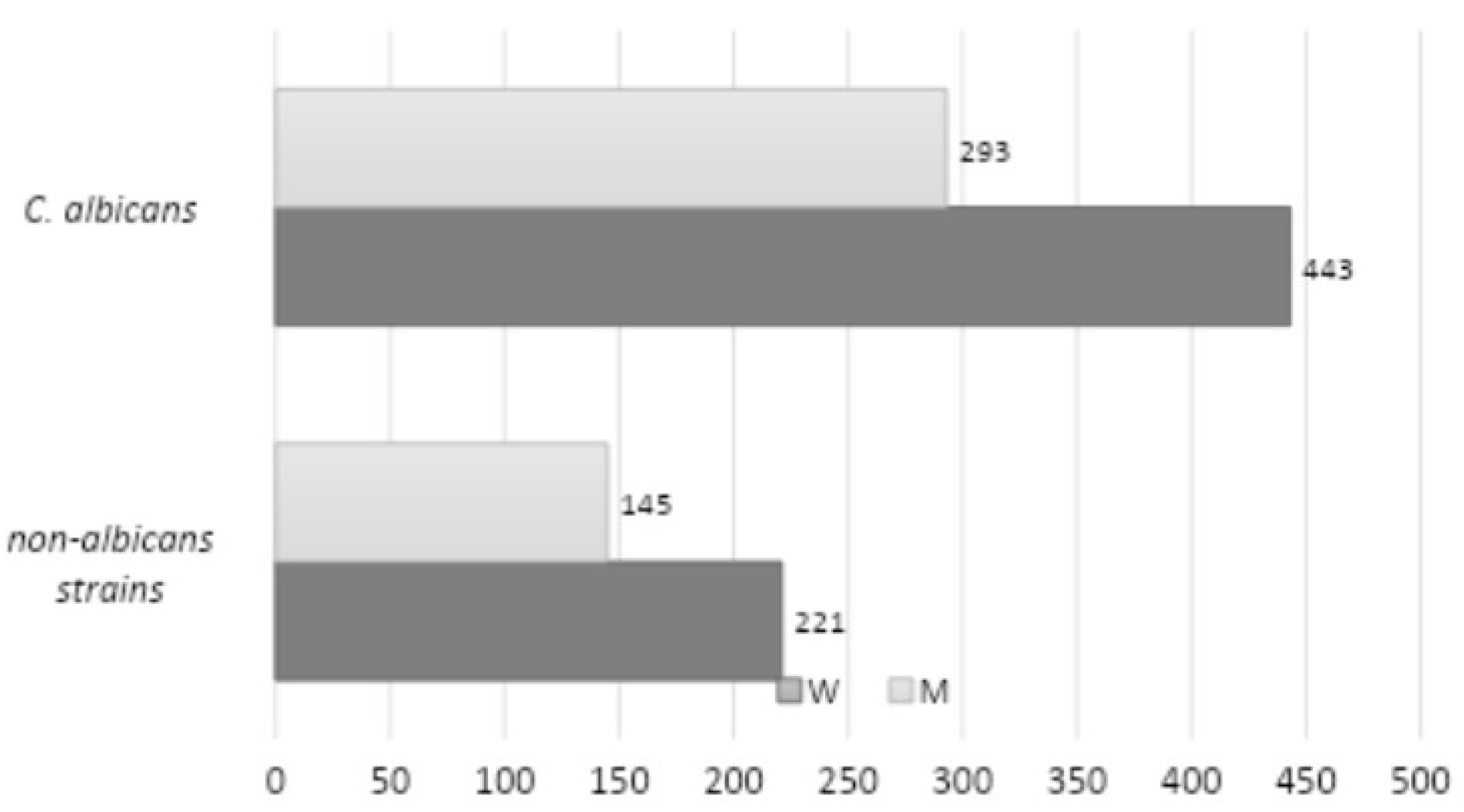

Figure 4 presents a comparison of the frequency of infections caused by

C. albicans and NAC, stratified by gender. A total of 736 strains of

C. albicans were identified (443 among women and 293 among men), while 377 strains of NAC were identified (221 among women and 145 among men). The study revealed no statistically significant correlation between the strain type and gender (

p = 0.9515).

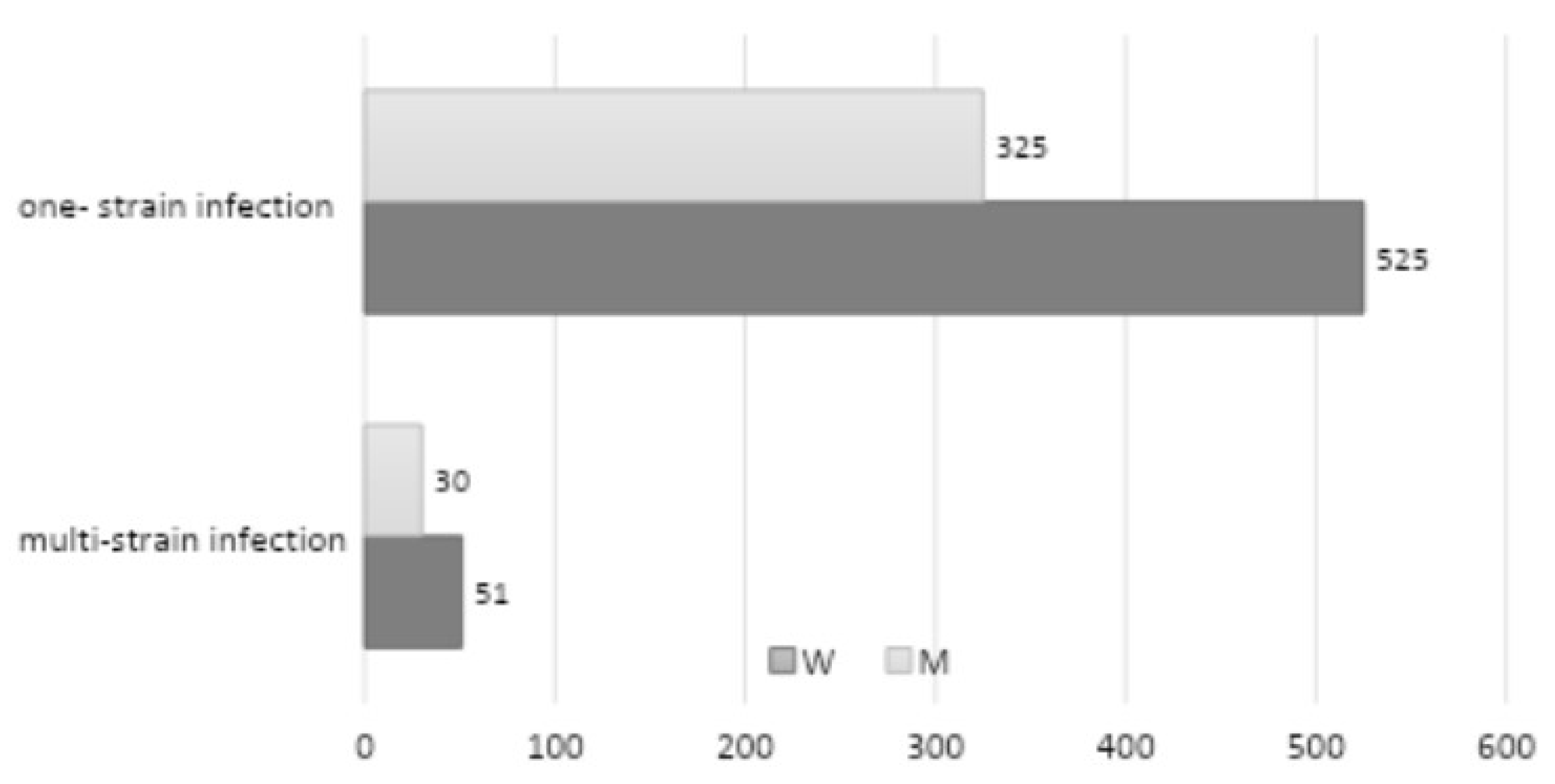

A five-year retrospective review documented a multi-strain infection in 81 patients (

Figure 5) (51 among women and 30 among men—8.46% of the total number of patients with a positive mycological examination) (the most common co-occurrence was

C. albicans with

C. glabrata,

C. albicans with

C. tropicalis, and

C. albicans with

C. krusei, while among NAC,

C. glabrata with

C. tropicalis). Infection with two strains was identified in 37 patients (3.86% of the total number of mycological positive patients), with three strains in 25 patients (2.61% of the total number of mycological positive patients), and with four strains in 19 patients (1.98% of the total number of mycological positive patients). The study demonstrated that there was no statistically significant correlation between multi-strain infection and gender (

p = 0.5899).

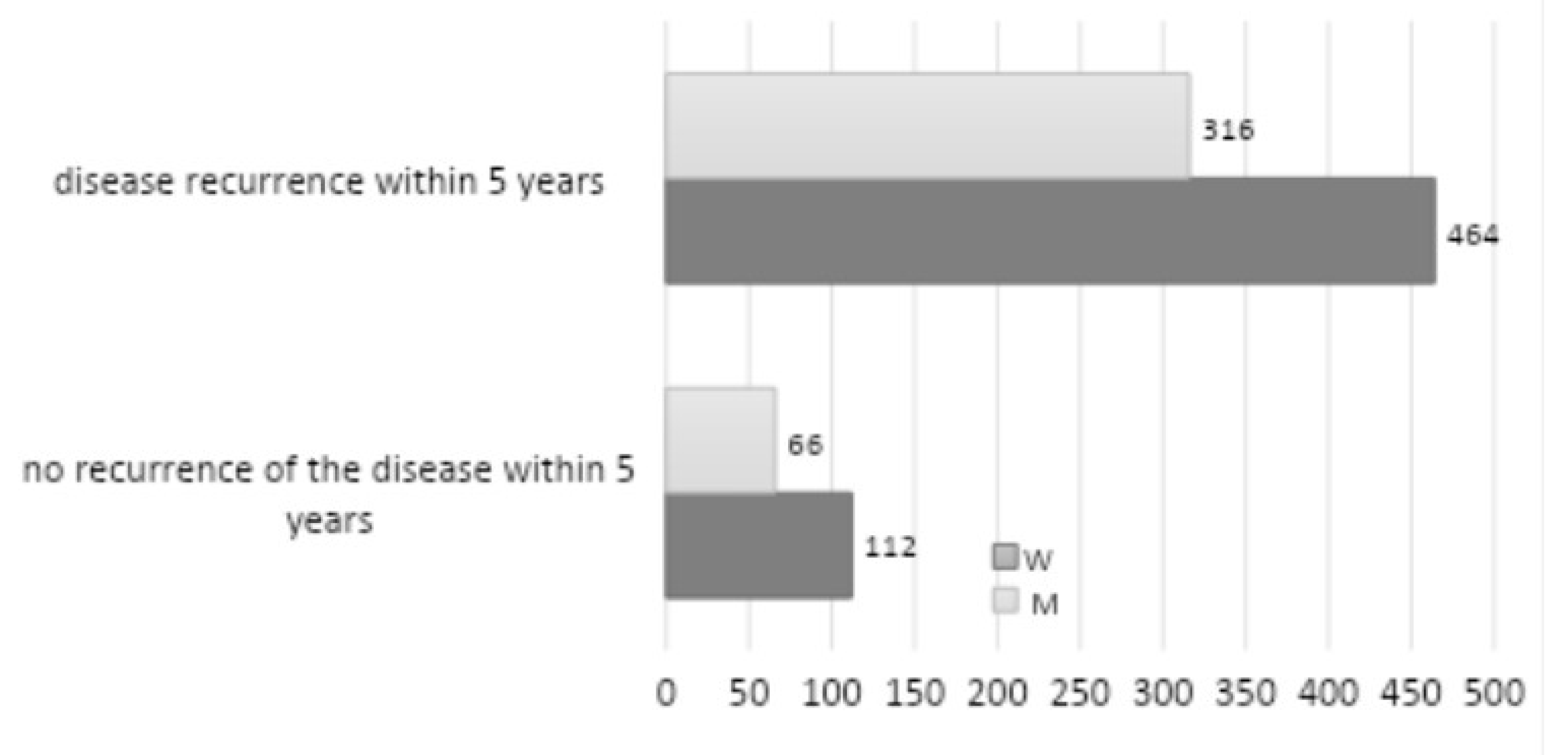

A total of 178 patients exhibited recurrence over five years (

Figure 6). Among these patients, 112 were women, and 66 were men, representing 18.58% of the total number of patients with a positive mycological examination. The most prevalent site of oral candidiasis was the palate, followed by infection localized on the denture plate, and less frequently on the tongue, cheeks, and corners of the mouth. Other etiologies, including bacterial and viral infections, were identified in 19 patients (1.71%), while candidiasis also manifested in locations outside the oral cavity in 13 patients (1.17%). These included the skin, hand, foot, nails, genitals, and the entire body. The data revealed no statistically significant correlation between recurrence and gender (

p = 0.3985). The most prevalent form of candidiasis observed in the oral cavity, based on distinctive characteristics, was chronic erythematous candidiasis (presenting with symptoms of prosthetic stomatitis and inflammation of the angles of the lips) (42.92%–552 of the total patients), followed by acute pseudomembranous candidiasis (26.83%–345 patients). A total of 323 patients (25.12%) were diagnosed with keratosis and superinfection with fungi, including lichen planus, leukoplakia, and lupus erythematosus. Hyperplastic candidiasis was identified in 49 patients (3.81%), erythematous acute in 42 patients (3.27%), and pseudomembranous chronic in 36 patients (2.80%). Rhomboid inflammation of the middle part of the tongue was diagnosed in 29 patients (2.26%) of the total number of patients.

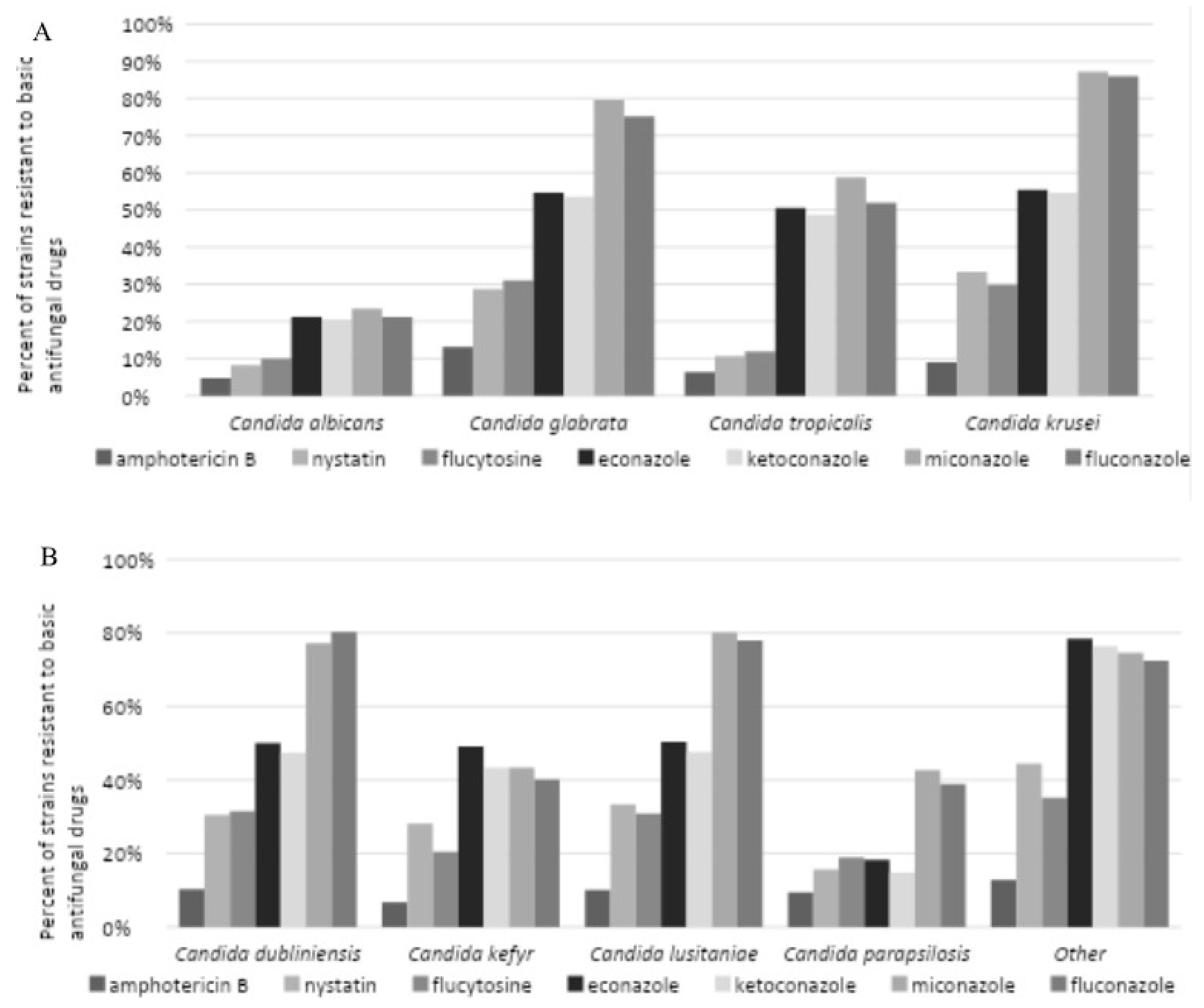

The data obtained permitted the assessment of drug susceptibility of eight

Candida strains, including

C. albicans,

C. glabrata,

C. tropicalis,

C. krusei,

C. dubliniensis,

C. kefyr,

C. lusitaniae,

C. parapsilosis and

C. stellatoidea. The results demonstrated exhibited resistance to seven primary antimicrobials, including amphotericin B, nystatin, flucytosine, econazole, ketoconazole, miconazole, and fluconazole (

Figure 7A and B). Regarding the most commonly identified strain,

C. albicans, drug resistance of less than 10% to amphotericin B, nystatin, and flucytosine was observed. In contrast, drug resistance to econazole, ketoconazole, miconazole, and fluconazole reached 30%. Most NAC strains (except for

C. parapsilosis) demonstrated a high level of resistance to azole drugs, with a resistance rate exceeding 40%.

C. krusei exhibited the highest level of drug resistance. Amphotericin B was identified as the most effective antifungal drug, exhibiting drug resistance below 15% across all strains tested. Nystatin demonstrated interaction with

C. albicans and exhibited drug resistance in 8.23% of the tested cases, with drug resistance levels below 20%.

C. tropicalis and

C. parapsilosis exhibited drug resistance in 30% of cases.

C. glabrata,

C. kefyr,

C. krusei,

C. dubliniensis, and

C. lusitaniae. The highest levels of drug resistance were observed for miconazole and fluconazole, with over 50% of NAC strains (excluding

C. kefyr and

C. parapsilosis) exhibiting resistance.

A review of the data collected revealed local factors that may contribute to an increased risk of oral mucosal fungal infections among the study group (

Table 2).

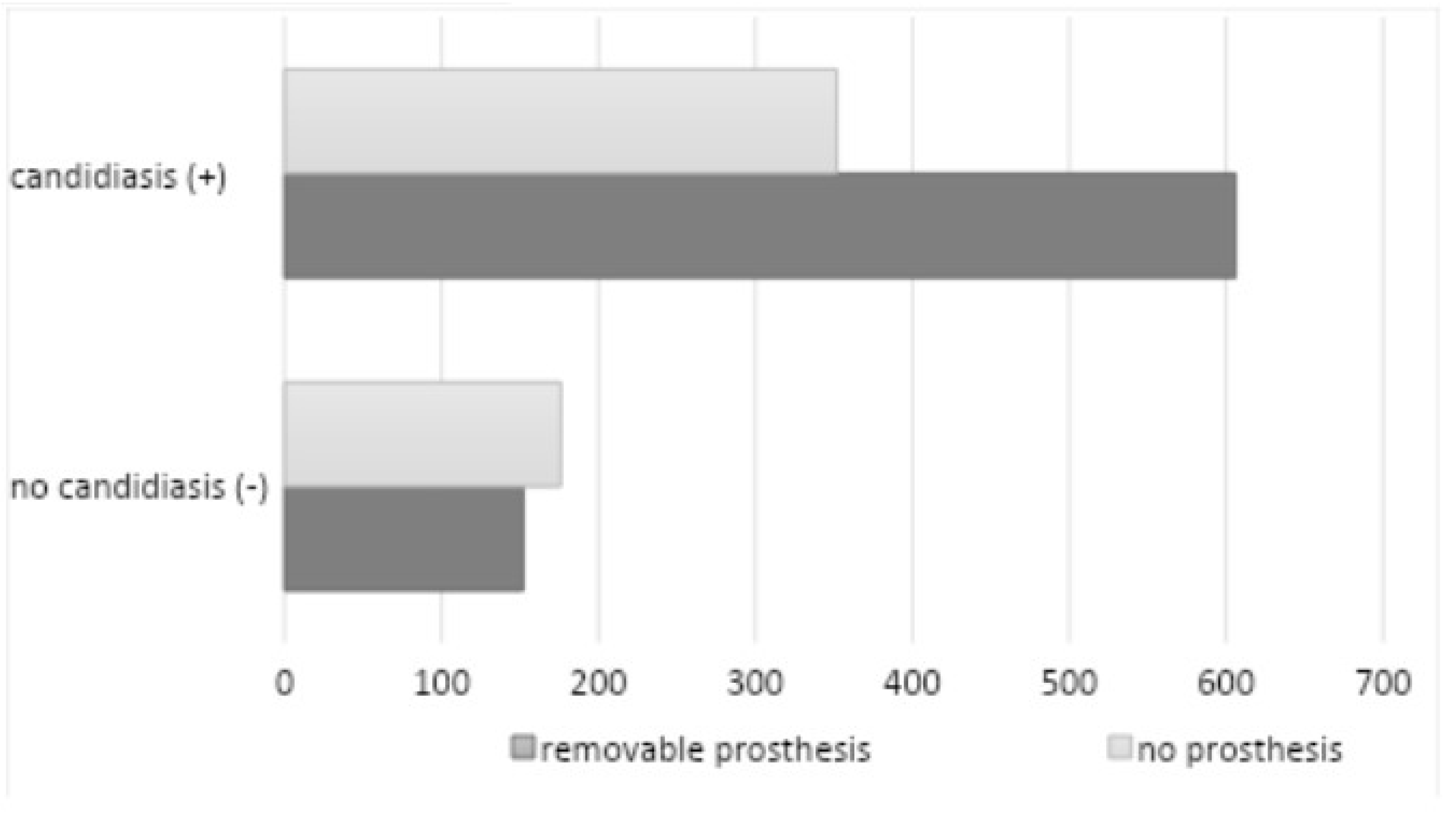

The use of removable dentures was documented among 758 patients (58.94%) (450 female and 308 male subjects), of whom 606 individuals exhibited a favorable mycological examination outcome (

Figure 8).

A total of 170 subjects (122 women and 48 men) were confirmed to have used dentures continuously. The study revealed a statistically significant correlation between the utilization of removable dentures and the prevalence of oral candidiasis (

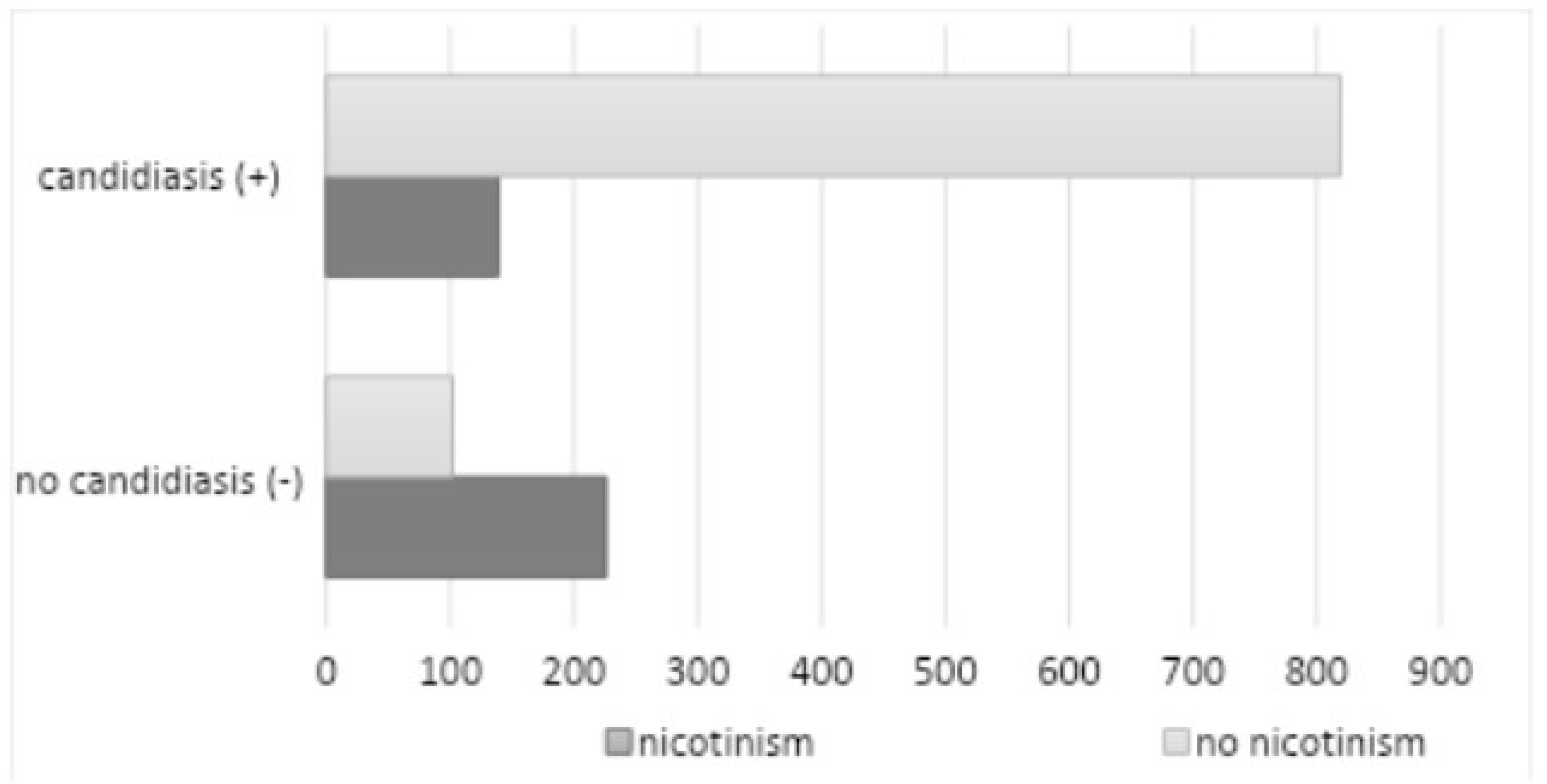

p=0.042). A total of 365 subjects (28.38%) reported nicotine dependence (201 women and 164 men), of whom 139 subjects had a positive mycological examination (

Figure 9).

Characteristics of the smoking group: 1-10 cigarettes/day: 31.06%; 11-20 cigarettes/day: 52.44%; >20 cigarettes/day: 16%. A majority (65%) of diagnosed patients smoke traditional, factory-made cigarettes. Another relatively common form of tobacco selected by respondents was roll-your-own tobacco (21%), while slim cigarettes (6%) and menthol cigarettes (5%) were smoked by few, with a higher prevalence among women than men. The use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) was reported by 5% of the surveyed population, with a particularly high prevalence among individuals aged 18-30 (29.5%), compared to traditional cigarettes (26.2%). The mean duration of the subject’s addiction was 22 years. The study found no statistically significant correlation between nicotine addiction and oral fungus (

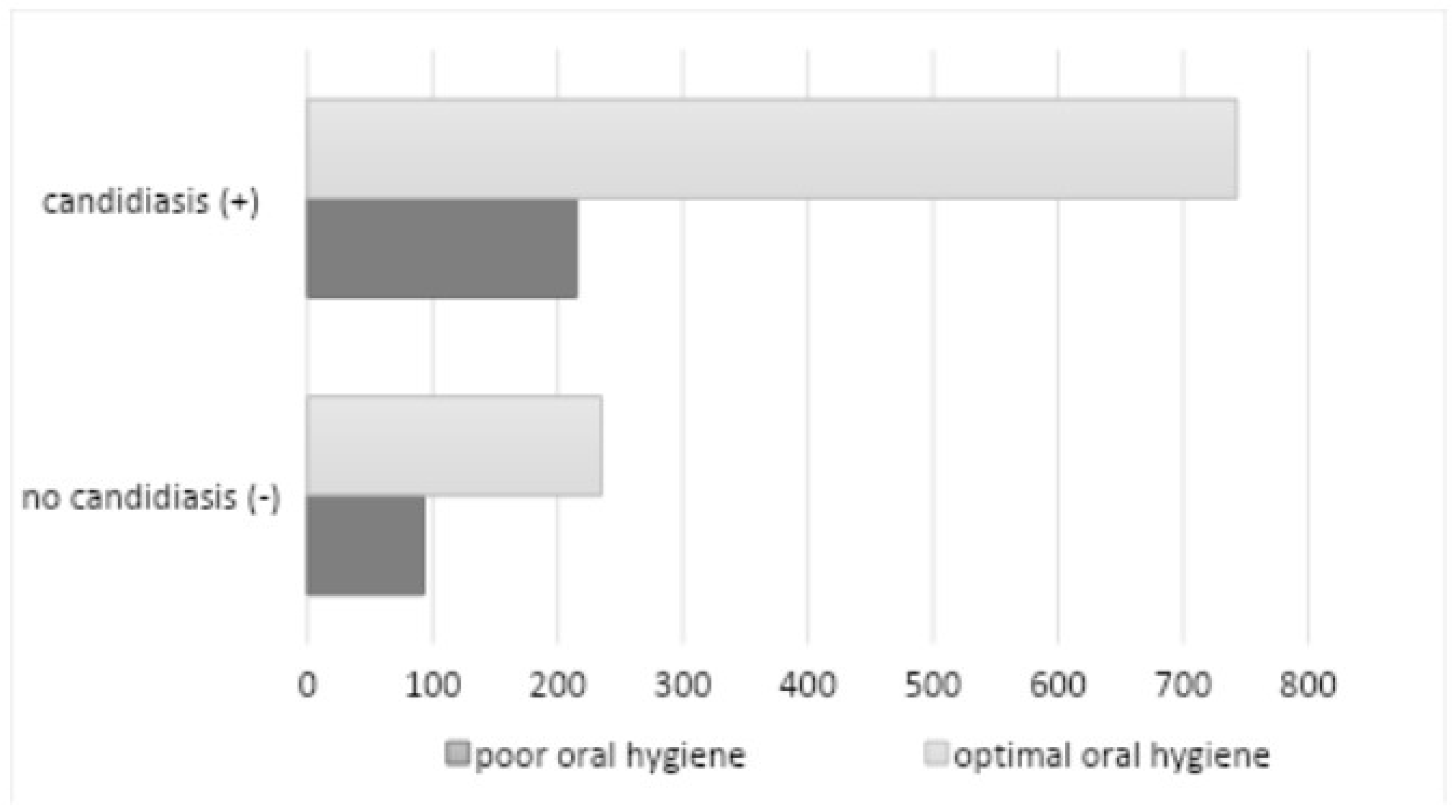

p=0.1446). Poor hygiene (API > 70%) was observed in 308 subjects (23.95%) (180 among women and 128 among men), of whom 215 subjects had a positive mycological examination (

Figure 10).

The study demonstrated a statistically significant correlation between poor oral hygiene and the occurrence of oral candidiasis (

p=0.0473). Decreased salivary secretion was observed in 248 patients (19.28%), comprising 164 women and 84 men, of whom 220 subjects exhibited a positive mycological examination (

Figure 11).

The factor was evaluated through the analysis of data obtained from an oral clinical examination. The study revealed a statistically significant correlation between reduced salivary secretion and the occurrence of oral candidiasis (p=0.0447).

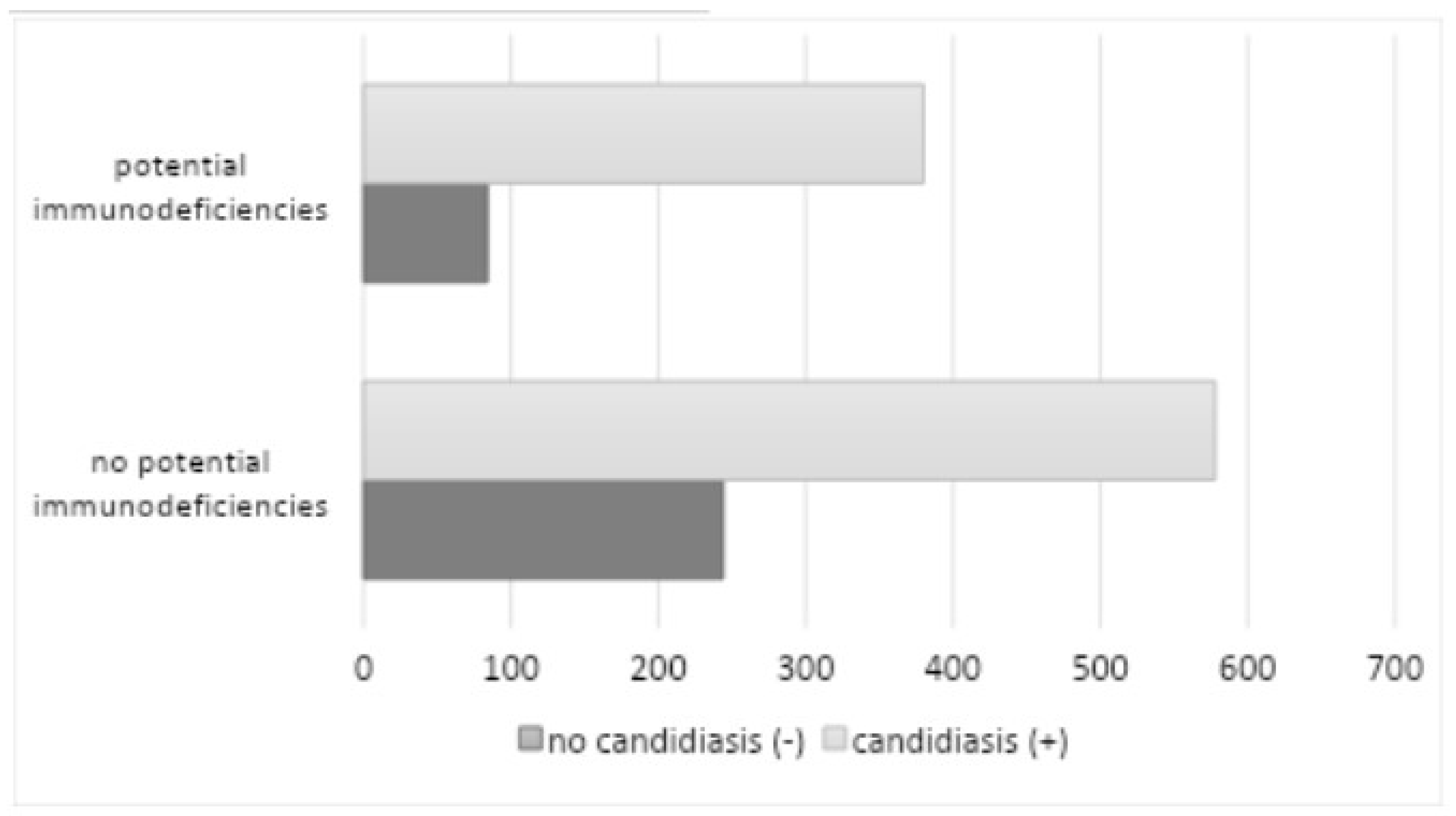

The data extracted from the analysis demonstrated the coexistence of systemic diseases and conditions that may increase the risk of oral mucosal candidiasis and exacerbate its course (

Table 3) in 464 patients (36.08%) (286 among women and 178 among men), 380 of whom had a positive mycological examination.

The most prevalent form of diabetes mellitus was uncompensated, affecting 172 patients (13.37%) with an HbA1c level of ≥6.5% (48 mmol/mol). The second most common form was systemic glucocorticosteroid therapy/inhaled steroid therapy, affecting 82 patients (6.38%). The most used glucocorticosteroids in this context were prednisone, prednisolone, and methylprednisolone, while betamethasone, budesonide, dexamethasone, and fluticasone were used in inhaled form. The use of systemic antibiotic therapy in the six months preceding the study was reported in 59 patients (4.59%) (penicillins, cephalosporins, and macrolides were the most used antibiotics), while AIDS/HIV was the least common, with eight patients (0.62%), and other immunodeficiency diseases and conditions (neutropenia), with five patients (0.39%). The study revealed a statistically significant correlation between systemic diseases and conditions with immune deficiency and the presence of oral candidiasis (p=0.0358). The data analyzed also provided information on the coexistence of other oral mucosal diseases among the 1286 patients. The most common comorbidity was lichen planus (196 patients - 15.24%), followed by recurrent oral ulcers (138 patients - 10.73%), burning mouth (122 patients - 9.49%), oral leukoplakia (118 patients - 9.18%) oral mucositis due to radiotherapy/chemotherapy (63 patients - 4.90%), geographic tongue (55 patients - 4. 28%), chronic labyrinthitis (36 patients - 2.80%), Sjögren’s syndrome (24 patients - 1.87%), lupus erythematosus (9 patients - 0.70%), ), pemphigoid (7 patients - 0.54%), pemphigus (6 patients - 0. 47%), stomatitis associated with anemia (5 patients - 0.39%), graft-versus-host disease (5 patients - 0.39%), oral mucosal carcinoma is the least common (4 patients - 0.31%).

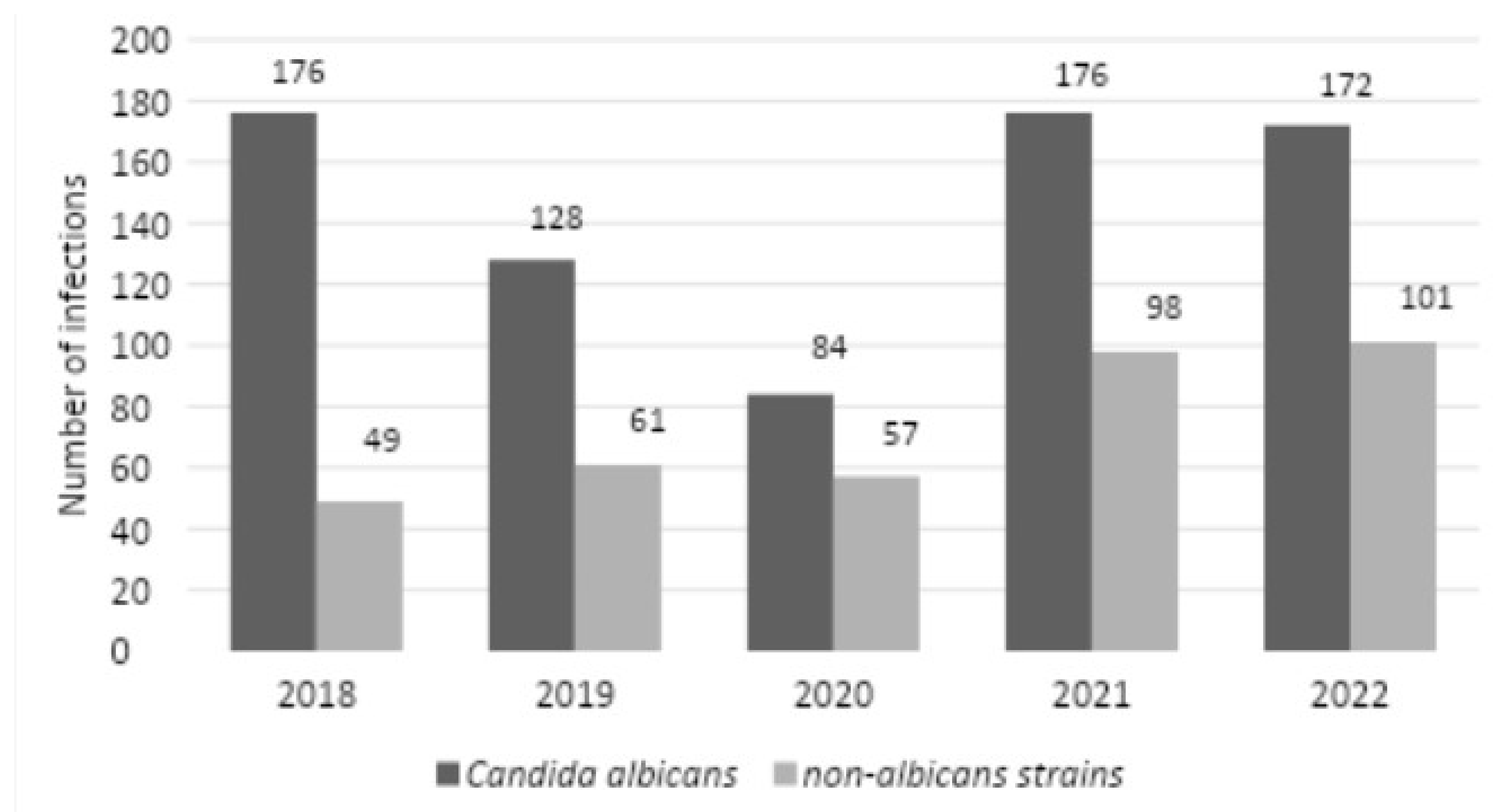

There were 176 C. albicans infections in 2018, while there were 128 infections in 2019, 84 infections in 2020, 176 infections in 2021, and 172 infections in 2022. For NAC infections, there were 49 infections in 2018, 61 infections in 2019, 57 infections in 2020, 98 infections in 2021, and 101 infections in 2022 (

Figure 12). In 2018-2021, the study found no statistically significant relationship between the distribution of different Candida strains (2019 vs. 2020,

p=0.1384; 2020 vs. 2021.

p=0.0663; 2019 vs. 2021,

p=0.4429), such a relationship was noted between 2018 and 2022 (

p=0.0290).

The medical records of 106 patients (8.24%) did not contain data on any of the risk factors analyzed in this study, but 56 patients (4.35%) had more than one risk factor for candidiasis.

4. Discussion

The primary objective of the retrospective study was to assess the prevalence of various Candida strains among patients presenting with diagnosed oral mucosal candidiasis at the Department of Periodontal and Oral Mucosa Diseases in Zabrze, Silesian Medical University in Katowice between 2018 and 2022. The increase in the incidence of fungal infections is paradoxically associated with medical advancements (cancer treatment, organ transplantation, prolonging the lives of immunocompromised patients, the development of new techniques for identifying microorganisms, the introduction of more invasive diagnostic methods, and the overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics in favor of targeted treatment) (32). In our study, a higher percentage of

C. albicans strains were detected compared to NAC, which is consistent with the retrospective analysis conducted at our Center in 2011 and with reports from Europe, South America, China, and the Middle East [

2,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37]. The epidemiological trends of

C. albicans and NAC exhibit considerable variation depending on geographic location, diagnostic center, and type of patient. However, the results of the retrospective study conducted at our Center (2011) indicate a notable increase in the frequency of NAC strains, from 22% in 2011 to 33.21% in the subsequent period. In an analysis conducted in 2020 by Bochniak et al. in Poland (228 patients), NAC was identified at 26.32%. In contrast, Muzaheed et al. reported in Saudi Arabia (1256 patients) a significantly higher prevalence of NAC, at 40%, between 2000 and 2019 [

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

38,

39,

40]. As observed in our study, a considerable proportion of

C. glabrata (9.8%) has been documented in previous research conducted in Europe, and North and South America [

39,

41]. Conversely, data from India indicated a notable prevalence of

C. tropicalis, in comparison to

C. glabrata [

42].

C. albicans remains the most prevalent pathogen responsible for BSIs, accounting for 35.9% of cases. However, the proportion of NACs has also risen over the past two decades [

43], with

C. glabrata being particularly prevalent in patients with candidemia [

44]. In contrast to the findings of the 2011 study, our retrospective analysis revealed the emergence of rare strains, accounting for 0.82% of the total strains identified (including

C. stellatoidea,

C. palmioleophila, and

C. nivariensis). In recent years, there has been an increase in the incidence of new strains that were previously rare and drug-resistant. It is imperative to accurately identify fungal species with distinctive susceptibility profiles, such as

C. auris or

C. palmioleophila, as treatment strategies typically rely on accurate species identification. [

10,

11,

45,

46,

47]. A multi-strain infection was documented in 8.46% of the total number of patients with a positive mycological examination, particularly in those using removable prosthetic restorations and afflicted with diseases and conditions linked to potential immune deficiencies. This finding is corroborated by a German study conducted by Hertel et al. [

2]. During the five years under analysis, a relapse was observed in 18.58% of the total number of patients with a positive mycological examination. In Poland, Bochniak et al. reported a recurrence of candidiasis in 27.63% of the subjects [

39].

Another objective of the analysis was to evaluate the drug susceptibility and resistance of

Candida strains to antimicotics. In comparison to the study conducted at our center in 2011,

C. albicans demonstrated a similar sensitivity to amphotericin B, nystatin, flucytosine, and econazole. However, there was an observed increase in sensitivity to ketoconazole, miconazole, and fluconazole.

C. glabrata demonstrated similar sensitivity to econazole, increased sensitivity to nystatin and ketoconazole, and decreased sensitivity to amphotericin B, flucytosine, miconazole, and fluconazole [

32]. The issue of antifungal drug resistance is a pervasive and increasingly prevalent phenomenon, as evidenced by a growing body of research [

4,

19,

48,

49]. The primary factor contributing to this shift is the excessive utilization of antifungal medications, particularly during prolonged therapeutic regimens and hospitalizations. This includes frequent prophylactic administration, the use of subtherapeutic doses, and the sequestration of drugs within the biofilm matrix. Additionally, inadequate infection control measures further exacerbate the problem. For example, an increase in

Candida resistance to azole derivatives was observed in the 1990s, which was attributed to prolonged antifungal therapy in individuals with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [

49]. Resistance can be based on different mechanisms that can vary from species to species. These include overexpression of a target enzyme that leads to its activity in the presence of antifungal drug, overexpression of drug scavenging pumps that reduce intracellular drug concentration, and mutations that lead to reduced intracellular drug accumulation by reducing drug import (48, 50). The efficacy of antimycotics is contingent upon the pharmacokinetics of the drugs, the quality of the immune system, and the site and severity of candidiasis. The host immune system plays a key role in the efficacy of antimycotic therapy. Antifungal drugs with a fixed formulation, such as azole derivatives, necessitate the support of the host immune system to effectively treat invasive infections caused by

Candida. In patients with severe neutropenia, the efficacy of these drugs may be diminished, necessitating the provision of supportive treatment [

49].

The subsequent objective of the review was to evaluate the risk factors associated with oral candidiasis. In most individuals diagnosed with the disease, one or more factors (4.35% of the subjects) predisposed to candidiasis could be identified. In only 8.24% of individuals within the study group, no predisposing factors could be identified. This finding aligns with the results of the Polish analysis by Bochniak et al., which indicated that approximately 8% of patients exhibited no predisposing factors [

39]. A review of the literature reveals a growing prevalence of predisposing factors for candidiasis across the globe in recent years, as evidenced by studies [

2,

4,

51].

The predominant risk factor (statistically significant) associated with oral mucosal candidiasis is the use of removable dentures. A fungal infection associated with denture use was reported in 47.12% of subjects in our 2011 study, 51.44% in an analysis from Poland, and 65.35% in data from China [

32,

34,

39]. Mycosis fungoides is a prevalent form of prosthetic stomatopathy. Chronic atrophic candidiasis represents the most common multifactorial chronic inflammatory condition of the oral cavity, affecting individuals who use dental prostheses, including partial or complete dentures, removable braces, and obturators. Additionally, the results of our current analysis indicate that this disease entity is the most prevalent among adult patients, accounting for 42.92% of the total patient population. The oral microbiome of denture wearers is less diverse than that of patients with full dentition, which may result in a higher rate of

Candida carriage [

52,

53,

54]. The pathogenesis of this condition is associated with

Candida infection, which may be caused by several factors, including ill-fitting dentures, suboptimal oral hygiene, nighttime denture wearing, and xerostomia [

55,

56,

57]. Saliva plays a dual role in the adhesion of

Candida to polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA). It displays physical cleansing activity and contains elements that are involved in non-specific immune mechanisms, including lysozyme, immunoglobulins, glycoproteins, lactoferrin, and peroxidase. These proteins interact with

Candida species, thereby reducing their adhesion and colonization on oral mucosal surfaces. A reduction in salivary flow beneath the surface of the prosthesis has been demonstrated to promote adherence of

Candida species and contribute to the formation of filamentous forms [

58,

59]. It has been demonstrated that trauma gives rise to an inflammatory response, which creates an environment conducive to the invasion of tissues and the initiation of infection by

C. albicans [

60]. The primary modalities of treatment are adherence to oral and denture hygiene protocols, the fitting or remaking of dentures, quitting smoking, avoiding wearing dentures at night, and the administration of topical or systemic antifungal drugs. Alternative treatments include microwave disinfection, phytomedicine, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy, and the incorporation of antifungal agents and nanoparticles into denture resins [

61,

62,

63,

64].

Candidiasis is a frequent pathological condition affecting the oral mucosa with a predilection for the elderly, newborns, and those with immune disorders. The onset of symptoms associated with candidiasis is linked to some predisposing factors that disrupt the body’s natural equilibrium through both local and systemic effects. Patients with immune disorders are statistically significantly more likely (

p=0.0358) to have

Candida infections. In our study, this was the most significant predisposing factor for oral candidiasis among the subjects [

65]. Our analysis demonstrated that uncompensated diabetes mellitus is the most prominent systemic factor (statistically significant) associated with immune dysfunction, affecting 13.37% of the subjects. This represents an increase from the earlier study of 2.86%, up 3.28% from the Polish analysis by Bochniak et al. and down 6.33% from the Chinese work by Yang et al. [

32,

39,

43]. Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a chronic metabolic and degenerative disease that predisposes individuals to opportunistic infections, including those associated with

Candida spp. The prevalence of candidiasis in diabetic patients is more than 77%. The main etiological factors associated with infection are the suppression of the immune system in diabetic patients with inadequate glycemic control and the direct impact of elevated glucose levels in the blood, saliva, and gingival fluid, which collectively foster optimal conditions for intense fungal colonization [

66,

67,

68,

69]. Another statistically significant factor was systemic glucocorticosteroid/inhaled steroid therapy, which was recorded in 6.38% of subjects. This represents an increase of 1.2% from the earlier study, an increase of 0.68% from the Polish analysis by Bochniak et al., and a decrease of 7.32% from the Chinese work by Yang et al. [

32,

39,

43]. This phenomenon is considered to result from a combination of immune system suppression and an increase in salivary glucose levels [

2,

70]. The use of antibiotics has been demonstrated to affect the immune system in some ways, including the modulation of its function and the resulting changes in homeostasis and decreased defense potential. This can lead to an increased susceptibility to secondary infections. However, it should be noted that this factor was not statistically significant, with a recorded incidence of 4.59% of subjects, which represents a 12.95% decrease compared to the analysis conducted by Bochniak et al. and a 2.21% decrease compared to the German study by Hertel et al. [

2,

32,

39]. The administration of antibiotics has been demonstrated to have a negative impact on the intestinal immune system, impeding the maturation of Th17 lymphocytes through the eradication of commensal bacteria that are instrumental in their development. Additionally, antibiotics have been shown to directly interfere with metabolic processes in myeloid cells, thereby constraining their capacity to effectively eliminate pathogens. It is significant to identify antibiotics that may have potentially adverse side effects and to understand the mechanisms underlying these relationships. This knowledge is essential for developing future treatment strategies and immune-based therapies that can prevent the adverse effects of antibiotics on the host [

71]. Immunosuppressive therapy, used in transplant patients, weakens the natural immune response, so the body becomes more susceptible to all kinds of fungal infections (a statistically significant factor observed in 4.2% of subjects, representing a 0.36% increase over the Polish analysis by Bochniak et al. and a 0.6% increase over the German study by Hertel et al.) [

2,

32,

39]. The disease and the therapy often result in immunosuppression and disruption of the immune system’s humoral and cellular response mechanisms. Candidiasis represents the most prevalent opportunistic infection among transplant recipients, accounting for 50-60% of infections [

72]. The most recent guidelines recommend risk-adapted prophylaxis, which is targeted prophylaxis aimed only at high-risk patients. The choice of antimycotic is dependent on several factors, including the antifungal spectrum, toxicity, pharmacokinetic metabolism, tissue penetration, and potential interactions with other drugs [

73]. In the treatment of head and neck cancer, radiotherapy (RT) plays a key role, with a statistically significant factor reported in 4.12% of subjects, representing an increase from the previous study of 2.76% (1.49% more than the Polish analysis of Bochniak et al. and more than the Chinese work of Yang et al. 3.64%) [

32,

39,

43]. Candidiasis exacerbates radiation-induced toxicity, so the RT treatment regimen may need to be significantly modified. Fungal infection occurs in about 50% of head and neck cancers before RT, and this percentage increases to 75% during treatment.

C. albicans is responsible for 80% of the infection, followed by

C. glabrata and

C. tropicalis. Factors that impact mucosal homeostasis during RT include the quantity and composition of saliva, smoking, antibiotic, and steroid use, the presence of dentures, and poor oral hygiene [

16,

74]. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) can lead to the development of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition characterized by a decline in the number of CD4+ lymphocytes, diminished NK cell activity, and the loss of helper T cells. In this group of patients,

Candida albicans was the predominant species (with a high frequency of NAC isolation) (an agent noted in 0.62% of patients, which is 0.18% more than the Polish analysis by Bochniak et al. and less than the German work by Hertel et al. by 3.01%) [

2,

32,

67]. Oropharyngeal candidiasis (OPC) is observed in up to 90% of patients with AIDS, representing the most prevalent opportunistic infection in this population [

51,

75]. The development of candidiasis is significantly influenced by the presence of neutropenia, particularly profound neutropenia (less than 0.2 x G/L) and prolonged neutropenia (lasting more than nine days), as well as lymphopenia, predominantly affecting CD4+ lymphocytes. This observation was documented in 0.39% of the subjects, a figure that is 10.31% lower than the findings reported by Chinese researchers, Yang et al. [

43]. The hematological conditions mentioned may be the result of underlying diseases or the effects of treatment modalities such as chemotherapy, RT, or immunosuppression, which can predispose patients to mycosis infection [

76].

Cigarette smoke represents a significant risk factor for the development of non-communicable diseases associated with an unhealthy lifestyle. It affects the host immune function, predisposing smokers to infection (reduced activity of multinucleated leukocytes). In our study material, 28.38% of participants were identified as current smokers, which did not reach statistical significance. In the Polish analysis by Bochniak et al., 19.3% of participants were identified as current smokers, while in the German analysis by Hertel et al., 29.2% of participants were identified as current smokers [

2,

39]. In men, the prevalence was 32.93%, a value that is significantly higher than that observed in the female subgroup (28.38%). Of the risk factors that we analyzed; this was the only one for which the prevalence differed statistically differently between the sexes. Individuals who smoke are seven times more likely to be infected with

Candida in the mouth, particularly in the context of poor oral hygiene. Interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) have been demonstrated to serve as critical mediators of antifungal, protective Th17 immune-inflammatory responses, particularly in the context of

Candida infection. Similarly, the intracellular expression of TNF-α was also strongly diminished following exposure to cigarette smoke. Consequently, this results in an impairment of the host’s defense mechanisms against infection by

C. albicans. Additionally, nicotine also has a direct effect on

C. albicans by increasing biofilm thickness and adhesion rates [

68].

The risk of increased fungal carriage is also influenced by the overall level of oral sanitation. In our analysis, 23.95% of subjects exhibited poor oral hygiene, a statistically significant factor. A study conducted in Australia by Mun et al. revealed a positive correlation between the occurrence of active caries and the frequency of isolation of

Candida spp. from the oral cavity [

77].

The analysis showed that the number of female patients with candidiasis was almost double that of male patients, a finding that is consistent with the results of our center’s 2011 study and the Polish study by Loster et al. [

78]. A study conducted in China by Yang et al. reported a slightly higher prevalence of cases among males than females [

43]. The differences in the prevalence of candidiasis in men and women may be attributed to anatomical and physiological differences between the sexes. The higher incidence of candidiasis in men in China may be due to differences in healthcare practices or cultural attitudes toward the disease [

34]. Patients of advanced age are more susceptible to infection due to a reduction in immunity, the presence of underlying disease, and the occurrence of polyposis. Most cases of candidiasis are reported in intensive care units [

32,

34]. Patients in the ICU are typically in critical condition and exhibit a compromised immune system. Croatian studies have demonstrated that the use of invasive procedures, including the insertion of central venous catheters, urinary tract catheters, mechanical ventilation, and parenteral nutrition leads to

Candida pathogenesis [

79]. The analysis provides an understanding of the microbiological profiles, characteristics, and drug susceptibility of selected

Candida strains. The data presented offer valuable insights for medical practitioners, facilitating accurate diagnosis and treatment of candidiasis. Furthermore, they provide a basis for exploring alternative therapeutic options in challenging cases where conventional methods prove ineffective.

In the future, we should expect to see a further increase in the number of patients with infections with NAC strains, rare strains

(C. auris), multi-strain infections, further development of drug resistance (the creation by microorganisms of new mechanisms to reduce their sensitivity to antimycotics) and an increase in the prevalence of potential risk factors for oral fungal infections. This results in intensified pressure from the scientific community to find new compounds with antifungal properties and alternative or adjunctive therapies that could be employed in the conventional and complex treatment of candidiasis [

9]. The development of drug resistance in

Candida is prompting the need for more in-depth research into the underlying mechanisms of this phenomenon and the detection of resistant isolates. The differentiation of certain species can only be achieved through molecular methods, which are typically costly and require specialized techniques. Therefore, it is necessary to identify novel, efficacious diagnostic approaches in the future [

10,

11,

45,

46,

47].

It is important to note that our work is not without limitations. Primarily, our analysis is based on a single center, and thus, future research should be conducted on a larger population across multiple scientific and research centers with a similar periodontal profile to enhance the generalizability of the findings. The analysis of disease entities diagnosed and treated in the clinic is beneficial for monitoring the prevalence of risk factors and changes in their trends, which is crucial for the effective therapy and prevention of the recurrence of the condition [

80]. Further limitations include the five-year scope of the review conducted, which encompasses the period of the global pandemic caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus, during which patient access to specialized healthcare was limited. Additionally, the number of patients included in the review is relatively small, and certain specialized diagnostic tools, such as molecular identification, PCR analysis, and single-methodology assessments of drug resistance, were not available. Furthermore, outpatient treatment was conducted instead of inpatient treatment, which may have affected the results due to potential patient nonadherence to prescriptions.