Globally, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is widely acknowledged as the gold standard treatment for people who suffer from symptomatic gallstone disease, a condition affecting between 10 and 15% of people. In the United States, there are more than 700,000 laparoscopic cholecystectomies performed every year, making up close to 90% of all procedures on the gallbladder. This surgical method affords many edge over open cholecystectomy, including smaller incisions leading to less postoperative pain, shorter hospital stays, and faster recuperation. Despite the superior benefits, complications, such as transient rises in liver function test results (LFTs) and bilirubin levels, can impact up to 1-5% of patients [

1].

The condition of raised LFTs and bilirubin following surgery in the acute phase, even without an apparent intraoperative injury, poses a severe clinical problem. There is regularly a sense that this rise is caused by bile duct injuries or other complications, even though, in many instances, the pathological results are indistinct. It is challenging to figure out what is causing these short-term changes since the patients' LFTs and bilirubin levels return to normal quickly over days with no intervention.

A number of concepts (Hypothesis) have been put forward to explain this member of individuals' claim that having pneumoperitoneum during laparoscopic surgery could cause short-term hepatic ischemia, which could then lead to sharp rises in liver tests. Ultimately, reactions to the stress that comes from anesthesia and surgery can damage liver cells or make the bile duct narrow. Inflammation that happens after surgery can also have an aspect, especially in people who already have diseases like diabetes and high blood pressure that affect liver function. This case study looks into why some patients who chose to have a laparoscopic cholecystectomy at the facility had higher-than-normal levels of liver function tests (LFTs) and bilirubin. The study identifies likely reasons for this trend and reviews its clinical relevance in developing improved postoperative management plans.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Data Collection

This is a retrospective study of 200 patients who underwent elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy at the Papageorgiou General Hospital and the Interbalkan Medical Center of Thessaloniki from 2019 to 2023. The following data were extracted from the patient’s medical records in a predetermined data sheet: patient age, sex, BMI, preoperative laboratory tests, day of surgery, days of hospitalization, surgical technique, intraoperative complications, postoperative laboratory tests including WBCs, hemoglobulin, SGOT, SGPT, total bilirubin, and direct bilirubin on the day of surgery and postoperative days 1 and 3, imaging studies available including abdominal CT or MRI/MRCP, and postoperative patient vitals.

Surgical Technique

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed via the 4-port technique and Hasson pneumoperitoneum by two surgeons (first surgeon and assistant). The “critical view of safety” was established in all the cases through careful dissection in the Calot’s Triangle before proceeding to cystic duct and artery ligation. In case of uncertain identification of the Calot’s Triangle contents or major complications including but not limited to major bleeding or bile duct injury, conversion to laparotomy was decided.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this study were adult patients who underwent elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstone disease from 2019 to 2023. Those with pre-existing liver diseases, clear-cut bile duct injuries, or any other extremity factors that may reflect in such findings as LFT and bilirubin levels were not involved in the analysis.

Data Analysis

The analyzed data focused on changes in LFTs and bilirubin levels from the day of surgery (day 0) to the postoperative day 3. Means and percentages, as descriptive statistics, were calculated to measure the amount of normalization, which is the most prominent feature in the case series.

Accessories were computed to represent the amendment of hepatic function laboratory tests and bilirubin levels on day 0 for easier comprehension and interpretation. The indices were calculated as follows:

Index Day 1 vs. Day 0 = (Day 1 value / Day 0 value) × 100%

Index Day 3 vs. Day 0 = (Day 3 value / Day 0 value) × 100%

These indices allowed for the evaluation of the relative increase and decrease in LFTs and bilirubin levels compared to the baseline.

Results

This cohort study included 200 patients who received elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy during the years 2019 through 2023. Of the total, six patients (3%) had temporary elevations in their liver function tests (LFTs) and bilirubin levels on their first day after surgery (Day 1), showing no symptoms that could suggest an intraoperative injury or complications, such as jaundice or abdominal pain. This rise in biochemical indicators without symptoms motivated the added probe.

Table 1 highlights the patient demographics and their preoperative attributes, with several showing comorbid conditions like hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia, which may impact liver function following surgery.

Table 2 illustrates the changes in liver enzymes and bilirubin levels across three-time points: procedural preparation (Day 0), postoperative (Day 1), and postoperative follow-up (Day 3). The findings revealed substantial elevations on Day 1, with increases in the mean amounts of SGOT and SGPT of 161.9% and 182.7%, respectively, along with total bilirubin increasing by 160%. Even with these heightened markers, none of the patients developed any clinical symptoms relating to bile duct injury or other complications. This finding corresponds with earlier reports of biochemical disturbance after minimally invasive procedures.

Table 3 illustrates the change indices for LFT and bilirubin levels compared to their preoperative values, pointing out the transient nature of these elevations. On Day 3, we observed a drop of 65.9% in SGOT and 189.3% in SGPT, along with normalized total bilirubin and direct bilirubin levels of 60.0% and 35.3%, respectively, since Day 0. Without any input, this significant drop backs the theory of a gentle, automatic self-limiting process.

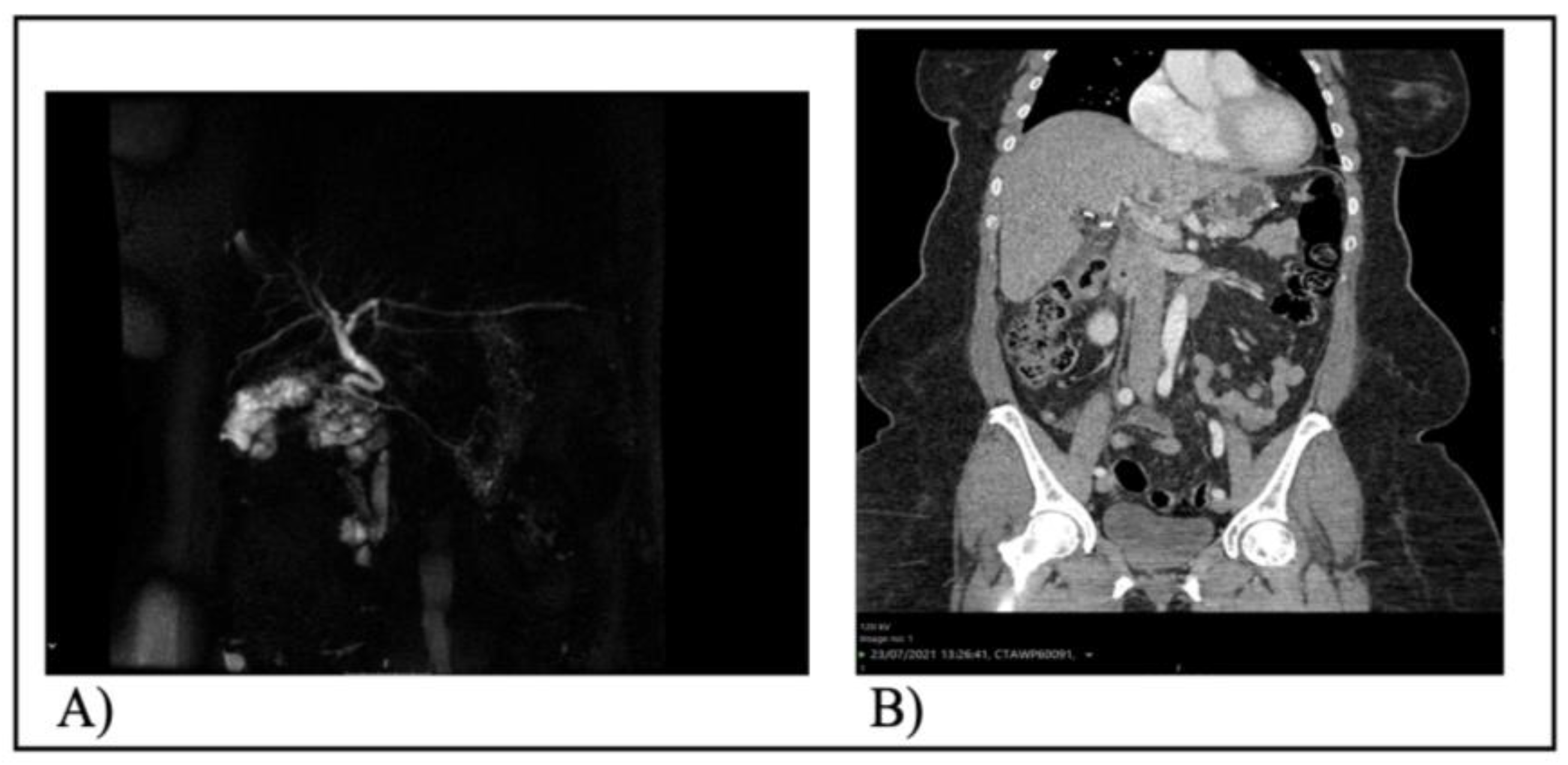

Documentation shows that diagnostic imaging was conducted for all patients to exclude abdominal intra-complications. Neither triple-phase CT scans nor MRCP revealed any pathological findings, including bile duct injuries, injuries to the hepatic artery, or remaining gallstones.

Figure 1 features the MRCP of patient 2 and the CT scan of the abdomen for patient 5, which validated the lack of postoperative problems

By Day 3, all biochemical irregularities had resolved independently without requiring any medical or surgical care. The consistent normalization of LFTs and bilirubin levels was observed in all patients, with no symptoms or complications during the brief follow-up period after recovery. Experts believe that the fleeting increases in LFTs and bilirubin result from perioperative elements, including pneumoperitoneum, the maneuvering of the liver during surgery, or anesthesia impacts.

These results suggest that postoperative elevations in LFTs and bilirubin can be alarming, but they could instead reflect a benign, self-limiting reaction to the surgical procedure if there are no clinical symptoms or imaging indicative of damage. None of the patients needed extended hospital stays; they were all discharged incident-free without any reported complications after the follow-up.

Discussion

The present study shows that a pattern involving measured transient increases in LFTs and bilirubin levels after elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which later return to normal without intervention, is consistently observed within a few days. This finding has also been reported in other studies, but the exact mechanisms still need to be discovered, and the researchers are still investigating. Surgical activity is closely related to the stone formation, visible inflammation processes, and dissection of the liver bed during the laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The immune response to the postoperative stress may result in local inflammation and damage to the liver cells, leading to elevated SGOT and SGPT serum levels [

2]. Moreover surgical site fluid accumulation could affect the bile flow , thus increasing the bilirubin levels. Ligation or banding of the cystic duct could cause interruption or edema that hinders the biliary flow. Buildup of bile ensues and subsequently, the sign of an increased level of bilirubin occurs [

3]. Bile retention after surgery occurs because of surgical manipulation using trocars. Thus, the transient elevation in bilirubin levels seen days after laparoscopic cholecystectomy possibly results from bile reabsorption. Eventually, the obstruction is resolved, and bilirubin levels are normalized. Sometimes, low bile flow develops spontaneously during surgery, due to surgical instrument manipulation causing bile retention and elevation of bilirubin levels after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Psychosomatic stress will be faced due to surgical stress characteristic of this laparoscopic cholecystectomy, leading to the release of inflammatory mediators and cytokines [

4]. Beyond these roles, the mediators had the potential to produce transient hepatocellular injury and impaired bile excretion, which would consequently lead to transient elevations in LFTs and bilirubin levels.

Clinical Implications

A significant point in this study is that the sudden LFT and bilirubin elevations resolved themselves naturally without any intervention, after which the patients were discharged asymptomatic without any other postoperative complications. This implies that these elevations are benign and a self-limiting phenomenon that is expected after uneventful laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Nevertheless, proper interpretation of these insights in the medical practice and other possible factors that can invalidate these explanations, especially medical conditions, must be considered. Therefore, a persistent rise in LFTs and bilirubin levels may require careful diagnosis should be investigated for other causes, such as bile duct injuries, hepatic dysfunction, or complications during and after the operation[

5].

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged:

Retrospective Design: A sense of retrospect in an experimental design, however, makes the admission of the unforeseen and undeterminable confounding factors inevitable, whereas relying on the accuracy of the medical records becomes crucial.The study consisted of only 6 cases, which restricted the extent to which the results could be generalized and reduced the study's power. With a small sample size, the chance of sampling error increases, making it impossible to assess the association or variance. The research study did not include any specific long-term follow-up data beyond postoperative day 3. However, the follow-ups may have provided some extra insights into the long-term results and the possible complications. The existence of the case-control group comparison or the comparison of those patients who experienced a transient elevation in LFTs and bilirubin levels during the laparoscopic surgery to those who did not disable the evolution of the underlying mechanisms. These restrictions make case-control studies less effective, and hence, there are serious concerns about defining the inclusion criteria and enlisting appropriate data collection strategies and control groups. Finally, our findings do not apply in case of an emergent cholecystectomy, as an ongoing inflammation interferes with the pathophysiology and may distort the clinical picture of the patient.

Future Direction

This case series offers a possible basis for future investigation directed at scouring the intricate mechanisms and clinical meaning of the transient elevation of LFTs and bilirubin levels following laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Potential research directions include:

Prospective Studies: A further step to getting consistent and reliable data would be to enlarge the scale of an ongoing study, which would entail applying a significant sample size and purely defined criteria of inclusion and exclusion. Prospective studies are likely to minimize the effects of confounding factors, standardize data collection, and methodologies, which will reduce bias. Such studies may lay the foundation for identifying the real-time prevalence, progression, and risk factors linked with continuously changing liver enzymes and bilirubin levels.

Mechanistic Studies: Investigating the possible mechanisms responsible for transient elevations is the critical finding block before any other narratives if we desire to present a comprehensive approach to the subject. Investigations examining inflammatory factors, physiology of bile ducts, hepatocellular injury,

Risk Factor Analysis: Identification of su.h risk factors, like patient-specific characteristics (age, gender, comorbidities), surgical techniques (length of surgery, approach), or perioperative care (drug use, anesthetic technique), that could predispose individuals to short-lived elevations might lead to the creation of preventive strategies or methods targeted at specific subgroups.

Long-term Follow-up: Long-term, large-scale follow-up studies might demonstrate therapeutic differences of prolonged cytokine peaks versus their transient accumulation in the development of liver diseases and other types of biliary or other long-term sequelae. Such investigation would give a clue to the disease progress and phenotype of individuals experiencing transient spikes, presenting evidence for decision-making and protocols for patient follow-up.

Conclusion

The present study shows that a transient increase of LFTs and bilirubin without notable intraoperative adverse events is self-limited within a couple of days after elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. However, the specific mechanisms remain an unresolved issue, and possible causes of surgery-related liver injury include surgical trauma, transient duct obstruction, leakage of bile and absorption reabsorption, and physiological stress response. With the global increase in the use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy, it is paramount that healthcare workers be aware of such a phenomenon and its clinical implications. Effective collaboration among surgeons, anesthesiologists, nurses, and other healthcare professionals can contribute to managing and improving the patient's condition and outcomes for laparoscopic surgery .This case series elevates an area for further research and also calls for ongoing investigation for the body's physiological response to the laparoscopic intervention.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dr. Kankan Chattopadhyay and Dr. Ratnajit DasLaparoscopic and open cholecystectomy: A comparative study. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V., & Jain, G. (2019). Safe laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Adoption of universal culture of safety in cholecystectomy. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery, 11(2), 62–84. [CrossRef]

- Majumder, A., Altieri, M. S., & Brunt, L. M. (2020). How do I do it: laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery, 5(0). [CrossRef]

- Villa, G., Lanini, I., Amass, T., Bocciero, V., Scirè Calabrisotto, C., Chelazzi, C., Romagnoli, S., De Gaudio, A. R., & Lauro Grotto, R. (2020). Effects of psychological interventions on anxiety and pain in patients undergoing major elective abdominal surgery: a systematic review. Perioperative Medicine, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Yu W, Jiang G, et al. Global Epidemiology of Gallstones in the 21st Century: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. Published online February 2024:S1542356524002052. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).