Submitted:

17 October 2024

Posted:

18 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Possible Causes Affecting Influenza Immunization During the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.2. Efficacy of Surveillance Systems on Epidemiology of Influenza During the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.3. Influenza Vaccination in Central America and Mexico Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic

3.4. Access to Influenza Vaccine in Central America and Mexico

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vicari AS, Olson D, Vilajeliu A, et al. Seasonal Influenza Prevention and Control Progress in Latin America and the Caribbean in the Context of the Global Influenza Strategy and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2021; 105(1): 93-101. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8274756/. [CrossRef]

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Reunión del Grupo Técnico Asesor (GTA) sobre Enfermedades Prevenibles por Vacunación. Las vacunas nos acercan, 14 al 16 de julio del 2021. https://www.paho.org/es/documentos/xxvi-reunion-grupo-tecnico-asesor-gta-sobre-enfermedades-prevenibles-por-vacunacion.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Inmunización en las Américas. Resumen 2020. 2020. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/55370.

- Leung NHL. Transmissibility and transmission of respiratory viruses. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021; 19(8): 528-45. Epub 2021 Mar 22. [CrossRef]

- Nasrullah A, Gangu K, Garg I, Javed A, Shuja H, Chourasia P, et al. Trends in Hospitalization and Mortality for Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Vaccines (Basel) 2023; 11(2): 412. [CrossRef]

- Doroshenko A, Lee N, MacDonald C, Zelyas N, Asadi L, Kanji JN. Decline of Influenza and Respiratory Viruses With COVID-19 Public Health Measures: Alberta, Canada. Mayo Clin Proc 2021; 96(12): 3042-52. [CrossRef]

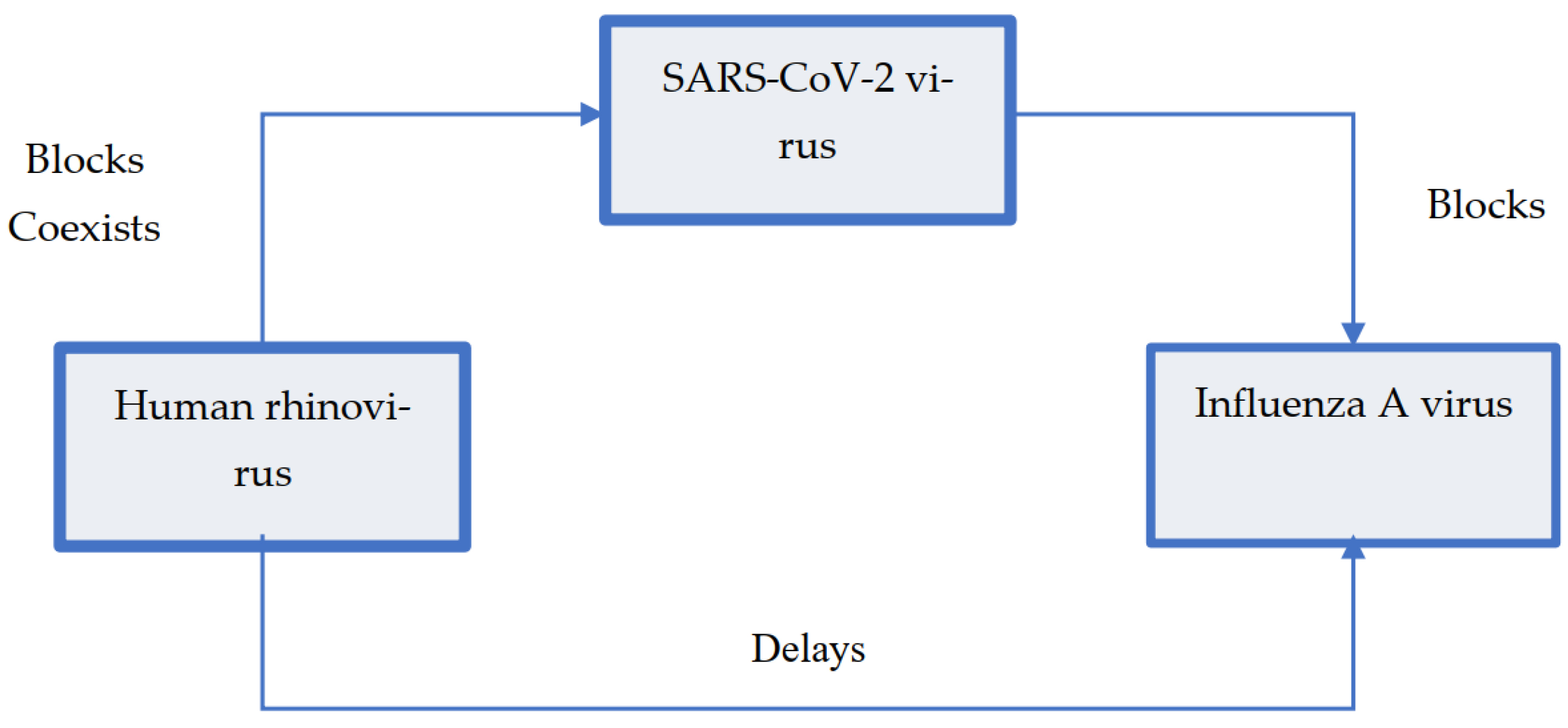

- Kiseleva I, Ksenafontov A. COVID-19 Shuts Doors to Flu but Keeps Them Open to Rhinoviruses. Biology (Basel) 2021; 10(8). [CrossRef]

- Wu A, Mihaylova VT, Landry ML, Foxman EF. Interference between rhinovirus and influenza A virus: a clinical data analysis and experimental infection study. Lancet Microbe 2020; 1(6): e254-e62. [CrossRef]

- Dee K, Goldfarb DM, Haney J, Amat J Ar, Herder V, Meredith S, et al. Human Rhinovirus Infection Blocks Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Replication Within the Respiratory Epithelium: Implications for COVID-19 Epidemiology. J Infect Dis 2021; 224(1): 31-8. [CrossRef]

- Moriyama M, Hugentobler WJ, Iwasaki A. Seasonality of Respiratory Viral Infections. Annu Rev Virol 2020; 7(1): 83-101. [CrossRef]

- Pan American Health Organization. Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses: Surveillance in the Americas 2021. 2022. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/56544.

- World Health Organization. FluNet Summary. 2024. https://www.who.int/tools/flunet/flunet-summary.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Vacuna contra la influenza. 2023. https://www.paho.org/es/vacuna-contra-influenza.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Precios Vacunas del Fondo Rotatorio de la OPS 2023. https://www.paho.org/es/documentos/precios-vacunas-fondo-rotatorio-ops-2023.

- Ministerio de Salud. Republica de Costa Rica. Lineamiento para la Jornada de Vacunación con Influenza Estacional 2022 en los establecimientos de salud de la Caja Costarricense del Seguro Social. 2022. https://www.cendeisss.sa.cr/wp/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Lineamiento-Influenza-2022.pdf.

- Influenza puede causar enfermedad grave en grupos de riesgo; vacúnese. 2021. https://lawebdelasalud.com/influenza-puede-causar-enfermedad-grave-en-grupos-de-riesgo-vacunese/.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud - iris Institucional Repository for Information Sharing. Preguntas frecuentes: Formulario conjunto para la notificación de datos sobre inmunización y estimaciones de la OMS y el UNICEF sobre la cobertura nacional de inmunización. 2020. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/52556.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Cobertura de vacunación contra influenza 2018. https://ais.paho.org/imm/InfluenzaCoverageMap.asp.

- UNICEF. Immunization coverage estimates dashboard. 2023. https://data.unicef.org/resources/immunization-coverage-estimates-data-visualization/.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Inmunización en las Américas, Resumen 2018. 2018. https://www.paho.org/es/node/59921.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Inmunización en las Américas, Resumen 2019. 2019. https://www.paho.org/es/documentos/inmunizacion-americas-resumen-2019.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Inmunización en las Américas. Resumen 2021. 2021. https://www.paho.org/es/documentos/inmunizacion-americas-resumen-2021#:~:text=Resumen%202021,-.

- Sparrow E, Wood JG, Chadwick C, Newall AT, Torvaldsen S, Moen A, et al. Global production capacity of seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccines in 2019. Vaccine 2021; 39(3): 512-20. [CrossRef]

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. La compra conjunta como parte de la preparación y respuesta frente a pandemias: Potenciar los fondos rotatorios de la OPS para fortalecer la equidad en la salud y la resiliencia. 2022. https://iris.paho.org/handle/10665.2/56956.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Estrategia Mundial contra la Gripe 2019-2030. 2019. https://www.paho.org/es/documentos/estrategia-mundial-contra-gripe-2019-2030#:~:text=La%20Estrategia%20Mundial%20contra%20la,y%20el%20control%20de%20la.

| Variables | SARS-CoV-2 | Influenza Virus |

|---|---|---|

| Transmissibility | ||

| Basic reproduction number (R0) | 0.5-8.0 | 1.0-21.0 |

| Household SAR (%) | 0-38.2 | 1.4-38.0 |

| Ways of transmission | ||

| Direct contact transmission | Yes | Yes |

| Fomite transmission | Yes | Yes |

| Airway transmission | Yes | Yes - main source of transmission |

| Aerosol transmission | Yes | Yes |

| Effectivity of non-pharmacological | ||

| Handwash | Yes | Yes |

| Face mask | Yes (within the house) | Yes |

| Surface cleanse | Limited | Limited |

| Close spaces ventilation | Yes | Yes |

| Country | SARI surveillance | ILI surveillance | National Center of Influenza | RT-PCR surveillance | External quality evaluation program | Last evaluation year | Flu ID report | Flu Net report |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belize | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2021 | Yes | Yes |

| Costa Rica | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2021 | Yes | Yes |

| El Salvador | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2020 | Yes | Yes |

| Guatemala | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No data | Yes | Yes |

| Honduras | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2021 | Yes | Yes |

| Mexico | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2021 | Yes | Yes |

| Nicaragua | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2020 | Yes | Yes |

| Panama | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2021 | Yes | No |

| Countries | Year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 (%) | 2018 (%) | 2019 (%) | 2020 (%) | 2021 (%) | 2022 (%) | 2023 (%) | |

| Influenza vaccine coverage in pregnant women | |||||||

| Belize | 8 | 48 | 72 | No data | 6 | 5 | 8 |

| Costa Rica | 72 | 73 | No data | No data | 69 | No data | 82 |

| El Salvador | 61 | 78 | 48 | 49 | 60 | 100 | 87 |

| Guatemala | 23 | No data | No data | 16 | 10 | 14 | 16 |

| Honduras | 78 | 82 | 85 | 84 | 63 | 60 | 67 |

| Mexico | 62 | 81 | No data | 78 | 88 | 88 | 81 |

| Nicaragua | 51 | 91 | 98 | No data | 89 | 87 | 98 |

| Panama | 58 | 64 | 63 | 73 | 58 | 79 | 93 |

| Influenza vaccine coverage in children | |||||||

| Belize | 73 | 70 | 83 | 54 | 85 | 41 | 43 |

| Costa Rica | 32 | 77 | No data | No data | 66 | 45 | 43 |

| El Salvador | 62 | 66 | 57 | 39 | 54 | 65 | 65 |

| Guatemala | 2 | 100 | 1 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 13 |

| Honduras | No data | No data | 62 | 53 | 47 | 38 | 47 |

| Mexico | 84 | 88 | 91 | 87 | 82 | 83 | 86 |

| Nicaragua | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Panama | 69 | 57 | 71 | 61 | 27 | 33 | 31 |

| Influenza vaccine coverage in elderly | |||||||

| Belize | 2 | 41 | 36 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Costa Rica | 92 | 99 | No data | No data | 61 | No data | 56 |

| El Salvador | 35 | No data | 42 | 37 | 45 | 57 | 64 |

| Guatemala | No data | No data | No data | No data | 3 | 3 | 5 |

| Honduras | 88 | 79 | 68 | 56 | 45 | 100 | 73 |

| Mexico | 94 | 94 | 94 | 94 | 95 | 95 | 95 |

| Nicaragua | No data | No data | No data | No data | 96 | 97 | No data |

| Panama | 100 | 100 | 83 | 99 | 18 | 67 | 65 |

| Influenza vaccine coverage in chronic conditions | |||||||

| Belize | No data | No data | No data | No data | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Costa Rica | No data | 79 | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| El Salvador | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data | No data |

| Guatemala | 100 | No data | No data | No data | 25 | 33 | 53 |

| Honduras | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | No data |

| Mexico | 100 | 99 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Nicaragua | No data | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Panama | No data | No data | No data | No data | 100 | 100 | No data |

| Influenza vaccine coverage in health personnel | |||||||

| Belize | No data | 78 | 46 | 12 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Costa Rica | 88 | 72 | No data | No data | 88 | No data | No data |

| El Salvador | 61 | 84 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99 |

| Guatemala | 74 | 90 | No data | 47 | 32 | 34 | 47 |

| Honduras | 100 | 100 | 85 | 82 | 59 | 88 | 91 |

| Mexico | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 95 | 100 |

| Nicaragua | 88 | 100 | 96 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Panama | 92 | 94 | 95 | 89 | 42 | 53 | 70 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).