1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis, the most common form of arthritis, is a disease that includes all elements from the synovial joints to the mainly affected components of cartilage and subchondral bones [

1]. It is known as the most common cause of functional failure in the elderly [

2], usually affecting the hand and large weight-bearing joints, often the knee and the hip [

3]. Although the pathogenesis of the disease is not clear, there is molecular evidence about the coordinated release of cytokines and inflammatory mediators from elements of synovial joints. Untreated or inadequately managed chronic pain can significantly diminish the quality of life, impose functional limitations, and restrict mobility in the elderly [

4]. In light of the increasing prevalence of OA and the growing need for improved pain management among the elderly, it is imperative to explore alternative treatments such as periarticular injections of GerovitalH3 to alleviate OA-related pain. The progression of OA has been associated with various risk factors including mechanical stress, biochemical abnormalities, genetic predisposition, and metabolic disorders, thus underscoring the importance of investigating novel therapeutic approaches [

5,

6]. Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate, either individually or in combination, are widely utilized globally by individuals experiencing osteoarthritis (OA) discomfort. While they are available as over-the-counter dietary supplements in some countries, they require a prescription in others. Prolonged use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular issues, gastrointestinal complications, and the progression of osteoarthritis. Managing and preventing these complications incur substantial costs [

7,

8].

An original Romanian “biotrophic” drug, GerovitalH3, developed by Ana Aslan in 1953, is used in the treatment of age-related rheumatic diseases and dystrophic disorders. Gerovital H3 contains the procaine component, first synthesized by Alfred Einhorn in 1905, and its metabolism involves two compounds: diethylaminoethanolic acid (DEAE) and para-aminobenzoic acid (PAB). Gerovital H3 action takes place at the cellular level where it stabilizes cell membranes, reduces the formation and accumulation of free radicals and inhibits the release of lysosomal enzymes [

9]. GH3, featuring the acetylcholine precursor DEAE, augments cerebral catecholamine activity, yielding favorable antiparkinsonian effects, and suppresses monoamine oxidase (MAO), thereby eliciting antidepressant effects [

10,

11]. Another metabolic compound – paraaminobenzoic acid (PAB) inhibits the solubilization of precolagen. According to recent research, proteolytic enzymes have the ability to increase the body’s self-healing mechanisms by promoting and quickening inflammatory and immunological responses. Additionally, they show a decreased incidence of treatment-emergent adverse events and a good safety profile [

12]. Its use as an adjuvant in the treatment of chronic degenerative rheumatism has led to pain control in approximately 92% of patients and to an increase in joint mobility in 50% of these. Numerous experiments on animals and tissue cultures have shown that procaine prolongs the average life span by 15-28% [

13].

2. Materials and Methods

A case-control, interventional and cross-sectional clinical trial was conducted to assess the efficacy of GerovitalH3 in reducing pain and enhancing functional abilities in elderly patients with knee and/or hip OA. This study design was deemed most suitable due to its ability to analyze a well-defined population within a relatively short timeframe.

Participants were assured that their privacy would be respected and that their responses would be analyzed anonymously. Additionally, a limited set of socio-demographic data, including age, gender, and place of residence, was collected.

Study design: The study comprised 220 patients who were enrolled between February 2023 and July 2024 in the Geriatrics and Gerontology Discipline Clinic from “Sf. Luca” Hospital Bucharest, Romania. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the “Sf. Luca” Chronic Disease Hospital and was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent.

Inclusion criteria: Eligible patients were men and women over 65 years old who had symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee and/or hip as defined by criteria of the American College of Rheumatology [

14].

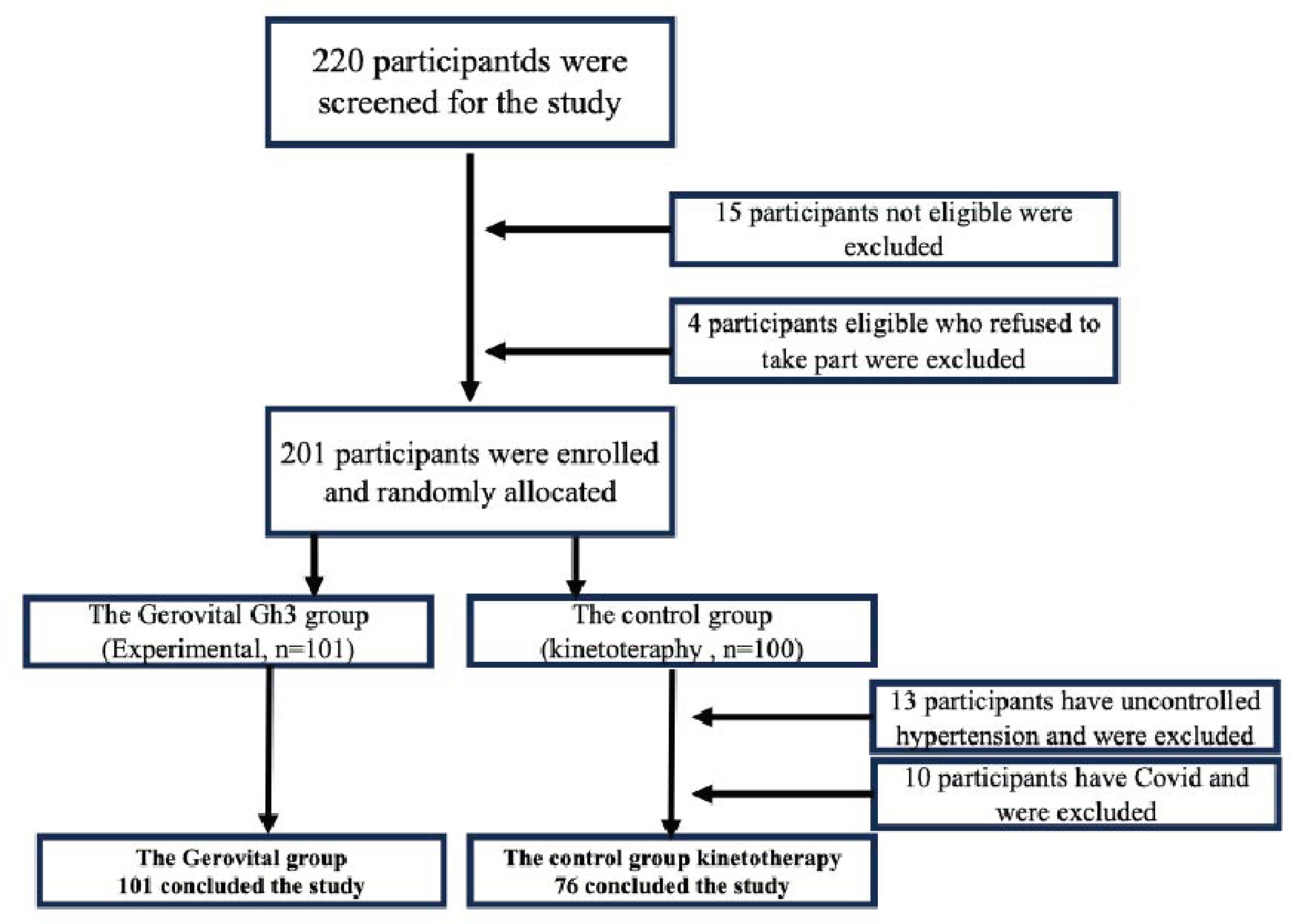

Exclusion criteria: The study excluded 15 individuals who had Alzheimer’s Disease, severe depression, mental illness, cancer of any type, history of any severe disease diagnosis (including severe diabetes, cardiovascular disease, etc.), those currently (within 30 days) taking any prescription or over-the-counter drugs that may affect neuroendocrine function or physical therapy within the past six months. We also excluded 4 individuals who were eligible but had refused to join the study, so there was a total of 201 participants who took part in this randomized study at the beginning.

Groups: Using random number tables, the 201 participants who met all the eligibility criteria provided written, informed consent prior to the study and were randomly allocated into the GH3 group (Experimental, n=101) or the control group (Control, n=100) with simple randomization method. In the control group, 13 patients had uncontrolled hypertension and could not do physical therapy, and 10 had Covid-19, and they were also excluded (Control, n=76). The primary outcome was the patients’ global assessment of pain in the affected joint as measured with VAS. Other outcome measurements included the Lequesne Functional Index, ADL and IADL index, and demographic characteristics.

The scores were assessed on presentation day (T0) and on the discharge day (T1) following the intervention. The determination of the sample size was influenced by limitations in the research period and available research funds.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study.

Researcher masking: Patients, the main researcher, and the researchers that evaluated the outcomes did not know which group the patients were allocated to.

Intervention: Each participant in the experimental group received periarticular injectable Gerovital H3 solution (5 ml contains 100 mg procaine hydrochloride) for 10 days. All patients were treated using the sterile injection technique. Participants in the experimental group (GH3 group) and in the control group both performed physical therapy daily. Before using Gerovital H3, the patient’s sensitivity to procaine hydrochloride was tested by the subcutaneous administration of 0.5 ml injectable Gerovital H3 solution, the presence of any allergic reaction contraindicating treatment. In the absence of sensitization to the tested substance, Gerovital H3 was administered.

Technique: The more painful and less functional knee was selected for the procedure. The injections were performed with the knee in a flexed position. Antisepsis was performed by applying gauze soaked in 70˚ GL alcohol, using circular, centrifugal movements three times in succession. The point of entrance of the needle was the femorotibial periarticular interline, and 1.5 cm below the apex of the patella to avoid the puncture of the Hoffa’s fat pad [

15]. Before injecting, aspiration of the syringe was performed to avoid joint effusion that might be present and ensure that the needle was not inside a blood vessel. Periarticular injections are well-tolerated and safe. Careful injection technique enhances the effectiveness in pain control. This procedure was repeated once daily for 10 consecutive days.

Evaluation tools:

Visual Analogue Scale (VAS): VAS is one of the most commonly used instruments to measure pain in the general population as it is considered the most sensitive, reproducible, and simplest pain scale. It is a 10-centimeter line with anchors at both extremities, with the words “without pain” at one end and “unbearable pain” at the other end. The patient is required to mark a point indicating their pain and a 0-100mm ruler is used to quantify the measure [

16].

Lequesne Index: Lequesne index comprises of 10 specific questions for patients with knee osteoarthritis, 5 related to pain or discomfort, 1 to maximum distance walked, and 4 to daily life activities. The score varies between 0-24 points and the higher the score, the worse the pain and function [

17].

Activity Daily Living (ADL): The Activities of Daily Living are a series of basic activities performed by individuals on a daily basis necessary for independent living at home or in the community. There are many variations on the definition of the activities of daily living, but most organizations agree there are 6 basic categories: personal hygiene, dressing, eating, continence, mobility and rest. Whether or not an individual is capable of performing these activities on their own or if they rely on a family caregiver for assistance to perform them serves a comparative measure of their independence. The score varies between 0-6 points and the lowest score represents dependence status [

18,

19]

Instrumental Activity Daily Living (IADL): IADL assessments evaluate patients’ ability to manage money, shop, cook, take medication, and use transportation for social integration. The total score is 0 (poor functioning, dependent) to 8 (high functioning, independent) [

20].

The diagnosis were grouped as follows: BAP: gonarthrosis, coxarthrosis, PSH = osteoarthritis of the peripheral joints (POA), BAV = spine osteoarthritis (SOA), BAVP = both central (spine) and peripheral joints are affected by osteoarthritis (SPOA), HD: spinal disc herniation and sciatica Osteoporosis Trauma (fracture).

Data analysis: All parameters were compared between the group of patients who received Gerovital H3 (GH3) associated with physical therapy versus the control group of patients who received only physical therapy (KT). According to the results, age and Lequesne variables were normally distributed. Non-parametric tests were used due to the unequal variances. Descriptive statistics were expressed in mean ± standard deviation (SD), and median (min-max) for continuous variables. Chi-square test for nominal and categorical variables (gender, residence, diagnosis, age categories) and independent-sample t-test for numerical variables (age) were used. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software.

3. Results

One hundred seventy-seven patients participated at the study. This group of older patients experienced at least one of the following symptoms/complaints: vertebral pain, memory decline, insomnia, , pain in the knees or hips.

One hundred and one patients received GH3 with mean age 70.10 ± 8.53 years. Seventy-six patients received kinesiotherapy (KT) with a mean age of 71.32 ± 9.33 years; the difference was not statistically significant (NS) between the two groups. The difference was not statistically significant (NS) between the two groups for gender either but was statistically significant regarding the residence: 121 (68.75%) patients from urban areas vs. 55 (31.25%) patients from rural areas; p<0.001. The administration of Gerovital H3 was done safely, no side effects were recorded. In our study group, we discovered that 50% of the female patients had gonarthrosis. Furthermore, regardless of the gender, 22% of those aged 66–74 developed gonarthrosis, the highest frequency of any age group.

In the cohort that received Gerovital H3 (GH3), the scores improved at the end of hospitalization (at T1 vs. T0), with the exception of walking and the depression scale, as follows:

Visual analogue scale improvement (VAST01); p<0.001

Pain score improvement (DT01); p=0.001

Walking score improvement (MT01); NS

Less difficulties in performing daily activities (AT01); p<0.001

Functional index Lequesne improvement (LT01); p<0.001

Geriatric depression scale improvement (GDST01), NS; p=0.078 – close to statistical significance. Interestingly, the data suggested that KT may be more effective than Gerovital H3 in reducing symptoms of depression (

Table 1).

The VAS revealed substantial variations across distinct diagnoses and age groups among the measured parameters (

Table 2).

Of all the indicators, VAS score was mostly improved in osteoarthritis of the peripheral joints (POA) and in the 2nd category (the elderlies). Additionally, it appears that following the intervention, the 4th category (the oldest old) may have the greatest potential for improvement in their walking ability compared to the other categories.

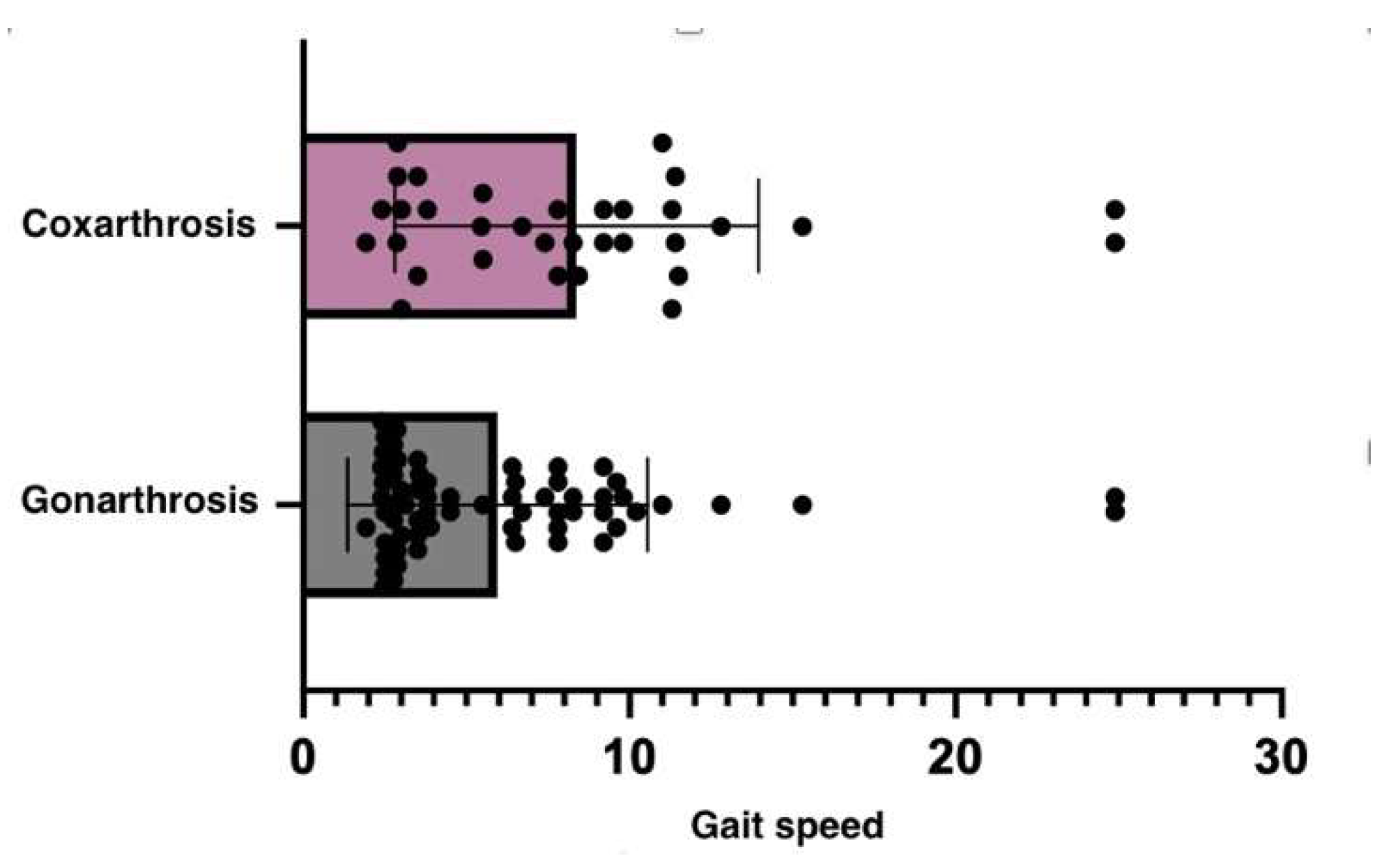

The VAS of pain was assessed before and after GH3 therapy in a group of patients with gonarthrosis, and statistical analysis revealed significant findings in the student t-test (p=0.0119). The actual change in pain ratings varied from -1.329 cm to -0.1714 cm, according to the 95% confidence interval, indicating that the therapy used had a significant effect in reducing pain in gonarthrosis patients, resulting in an improvement of their clinical condition (

Figure 2).

These results suggest that patients with coxarthrosis may experience more severe mobility and balance problems than those with gonarthrosis. The up-and-go test is more impacted in the coxarthrosis group (

Table 3). Since the hip joint is in charge of a wider range of motions and activities, its impairment can significantly determine a patient’s mobility and equilibrium.

The study demonstrated that there was no statistically significant variance in the improvement of parameters between coxarthrosis and gonarthrosis.

4. Discussion

Older adults have limitations in their daily activities and performance. In our study we examined the possibilities of increasing their well-being in terms of relieving pain, depression or augumenting mobility through another intervention besides oral NSAIDs or neuropathic drugs [

21,

22]. Comparative with these studies’ periarticular injection with GH3 didn’t have any adverse reactions.

Our results were also corroborated by those of Giombini et al., who used oxygen-ozone for 23 patients with knee OA and found it effective in relieving pain and improving function and quality of life [

23]. In spite of the randomization table being generated by a computer program, there were more patients in the ozone group than in the placebo group.

Physical function and physical activity have a well-established direct association that improves health outcomes for older persons [

24]. GH3 was found to improve pain and mobility, possibly linked to the anti-inflammatory effects reported by former studies [

9]. These improvements were documented by dedicated scales (VAS), pain and activities parts of Lequesne scale and the global Lequesne functional index.

In contrast to prior research, our study did not yield evidence supporting the use of Gerovital H3 for alleviating depression [

25,

26]. However, consistent with existing literature, we observed a significant role for physical therapy in managing depression symptoms [

27,

28,

29].

In addition to oral NSAIDs or neuropathic medications, our study examined various interventions’ potential to enhance patient well-being by reducing pain, alleviating distress, or enhancing mobility. Unlike prior inquiries, periarticular GH3 injection demonstrated no adverse side effects and led to increased functional activities.

One may argue that procaine, the first injectable local anesthetic, was the precursor to all contemporary local anesthetics. Procaine, a molecule consisting of a lipophilic aromatic head, a hydrophobic terminal amine tail, and a hydrophilic aromatic head joined to the aromatic acid by an ester link, is created when an aromatic acid (para-aminobenzoic acid) and an amino alcohol mix [

9].

The study and meta-analysis published in the Journal of Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine (JAMDA) shows a strong correlation between chronic pain and sarcopenia in the elderly. According to this research, patients with pain were 11% more likely to develop sarcopenia compared to those without pain, and sarcopenia was identified as independently associated with chronic pain [

30,

31]. There was no statistically significant difference in IADL performance between people with coxarthrosis and gonarthrosis (p = 0.3532). When comparing our study to Oliveria and colleagues’ [

32] age- and sex-standardized incidence rates of hip and knee symptomatic pain, the gender-specific differences in the percentage of people with gonarthrosis or coxarthrosis were not statistically significant (X2 = 0.005; df = 1; p = 0.940).

Various confounding factors such as age, weight, level of physical activity, sample size, and individual variability may contribute to these findings.

In a meta-analysis on the efficacy of intra-articular hyaluronic acid for the treatment of gonarthrosis, Arrich et al. found a mean difference in VAS scores of -8.7 mm between the hyaluronic acid treatment group and the control group when all trial results were pooled [

33]. Both hyaluronic acid treatment and Gerovital H3 treatment resulted in a statistically significant improvement in pain reduction, as indicated by p-values below the conventional threshold of 0.05 when comparing treatment group data. Based on the negative mean differences, it appears that both therapies successfully relieve pain.

Osteoarthrosis is the most prevalent joint disease and is the main cause of functional incapacity among elderly people [

34]. Knee OA is the fourth commonest cause of health problems among elderly women [

35] and also in our study we found a 52% prevalence.

The evidence for the medical use of GH3 is, for the most part, based on results of observational studies and case reports in which it has been used in the treatment of several diseases with large effectiveness.

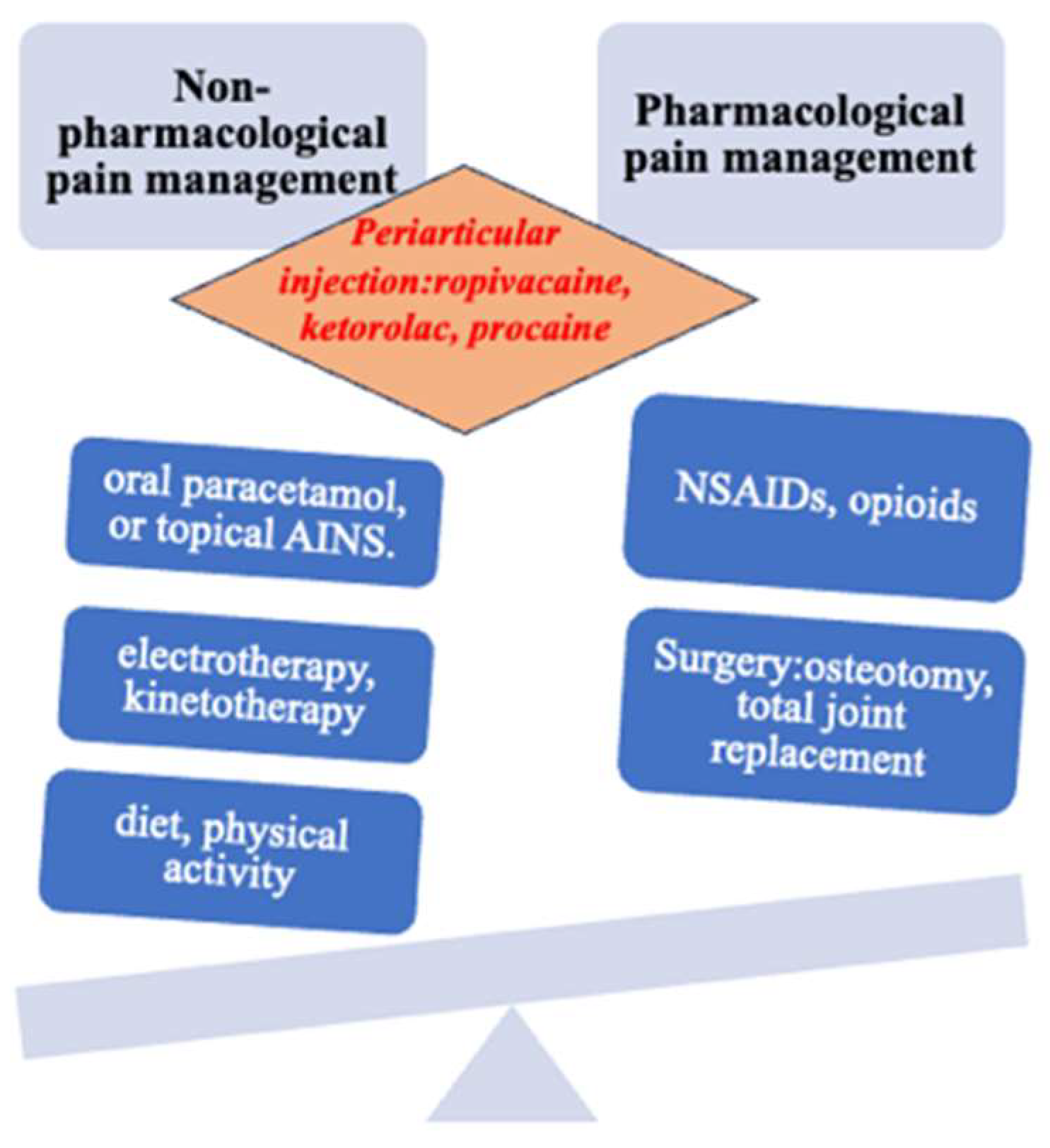

The management of osteoarthritis necessitates an individualized approach and often involves a combination of treatment modalities. Adjustments to the treatment plan should be made based on the patient’s response. Unfortunately, the majority of tested and utilized treatments revolve around pharmaceutical interventions, surgical procedures, or a combination of both.

For example, in a recent meta-analysis, 60% of trials assessed the effect of drug treatment and 26% evaluated surgical procedures. The lack of studies evaluating rehabilitation techniques, including bracing and other self-management techniques, has been labelled “research agenda bias” [

36] and is, in part, a consequence of lucrative opportunities for drug development. The toxicity and adverse event profile of the most commonly used existing treatments (such as NSAIDs, cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX 2) inhibitors, and total joint replacement) are unfavorably compared with conservative interventions such as exercise, weight loss, braces, and orthotics [

37,

38]. Some management guidelines are based on evidence from trials and expert consensus (see additional educational resources). The recommended hierarchy of management should consist of nonpharmacological treatments first, then drugs, and then, if necessary, surgery (

Figure 3). Too often the first step is forgotten or not emphasized sufficiently, to the patient’s detriment [

39].

Periarticular multimodal analgesia (PMA) injections are used to improve postoperative pain management by decreasing local inflammatory responses after total knee arthroplasty; nevertheless, the technique of administering the medicine plays a crucial role in their effectiveness. Due to its innervation, the periosteum of the tibia and femur is the main target of the injection around the knee [

40]. Numerous research have looked into the benefits of periarticular drug infiltration. Jiang et al. found that infiltration of analgesics for pain control gives better pain reduction than intravenous analgesia alone [

41]. The effectiveness of this alternative pain management technique with GH3 in elderly rehabilitation requires further research.

Safety and Tolerability

Periarticular Gerovital H3 has been shown to be safe for use. Adverse events are rare and transitory pain in the knee at the moment of Gerovital H3 puncture. In the present study, adverse effects were not collected but it was recorded in 3 patients (dizziness and orthostatic hypotension) and included only puncture accidents. Treatment compliance was 98.88%, with 2 drop-outs in the Gerovital H3 group for allergies.

Study Limitations

The low number of subjects and the short study period limit the analysis. No personality traits were analyzed, with a relevant variable missing. Considering that depression is linked to personality, individual characteristics should be considered in the future.

However, its evidential strength in establishing a causal relationship is comparatively less robust than other study methodologies. Nonetheless, it can be used as a documented starting point for further research using more rigorous scientific methods. The case and control pairs selected for the study may not be truly representative of the disease, especially since the cases were seen in a teaching hospital, a highly specialized setting compared to most locations where this disease can be treated.

5. Conclusions

The administration of Gerovital H3 can be promoted for aged patients who face difficulties in carrying out daily activities, which can lead to the improvement of both pain and functional capacity. No adverse reactions from GH3 administration were found in this study. This exploratory study shows that treatment with GH3 can reduce pain and improve locomotor function in patients with OA of the knee and/or hip as a complementary therapy.

These preliminary results show that it can be proposed mainly to elderly, aged 65-74y, and in cases with osteoarthritis of the peripheral joints (POA). It seems that the oldest old population, over 85 years can especially benefit from improving walking. Considering that depression seems to be improved by physical therapy, a complex care plan can be developed and tested in the future, which combines both the administration of Gerovital H3 and physical therapy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.M.A. and A.C.; Data curation: A.I.V.T., R.M., A.Z. and J.A.; Investigation: C.D.G., M.S.G. and A.G.P.; Methodology: S.M.A.,M.V.A.,A.I.V.T; Resources: R.M., J.A., A.Z., C.D.G. and M.S.G.; Software: C.O. and J.A.; Supervision: J.A., S.M.A. and A.C.; Validation: S.M.A.; Visualization: S.M.A., J.A. and C.O.; Writing – original draft: S.M.A., R.M. and C.O.; Writing – review & editing: C.O. and J.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Commission of the HOSPITAL OF CHRONIC DISEASES SF. LUCA; (protocol code 10, date of approval 09.06.2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent to participate in the research was obtained from each patient/subject.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

Publication of this paper was supported by the University of Medicine and Pharmacy Carol Davila, through the institutional program Publish not Perish.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest and no competing interests. All authors made appropriate contributions to the conception and design of the study. All authors have no conflict of interest that may have affected the conduct or presentation of the research.

References

- Loeser, R.F.; Goldring, S.R.; Scanzello, C.R.; Goldring, M.B. Osteoarthritis—a disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis Rheum 2012, 64, 1697–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, R.C.; Felson, D.T.; Helmick, C.G.; Arnold, L.M.; Choi, H.; Deyo, R.A. , et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum, 2008; 58, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, J.; Krasnokutsky, S.; Abramson, S.B. Osteoarthritis: a tale of three tissues. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 2008, 66, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schwan, J.; Sclafani, J.; Tawfik, V.L. Chronic Pain Management in the Elderly. Anesthesiol Clin 2019, 37, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan Tat, S.; Lajeunesse, D.; Pelletier, J.P.; Martel-Pelletier, J. Targeting subchondral bone for treating osteoarthritis: what is the evidence? Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010, 24, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Winzenberg, T.; Nguo, K.; Lin, J.; Jones, G.; Ding, C. Association between serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013, 52, 1323–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, T.A.; Wang, X.; Nevitt, M.; Abdelshaheed, C.; Arden, N.; Hunter, D.J. Association between current medication use and progression of radiographic knee osteoarthritis: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021, 60, 4624–4632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriarty, F.; Cahir, C.; Bennett, K.; Fahey, T. Economic impact of potentially inappropriate prescribing and related adverse events in older people: a cost-utility analysis using Markov models. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e021832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradinaru, D.; Ungurianu, A.; Margina, D.; Moreno-Villanueva, M.; Bürkle, A. Procaine-The Controversial Geroprotector Candidate: New Insights Regarding Its Molecular and Cellular Effects. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 3617042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasca, L.A.; Donca, V. Gerovital – Prophylaxis of aging and geriatric treatment. Balneo Research Journal 2015, 6, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capisizu, A.; Aurelian, S.M.; Mirsu-Paun, A.; Badiu, C. A key for post stroke rehabilitation in the elderly. Acta Mediterranea 2016, 3, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Ueberall, M.A.; Mueller-Schwefe, G.H.; Wigand, R.; Essner, U. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of an oral enzyme combination vs diclofenac in osteoarthritis of the knee: results of an individual patient-level pooled reanalysis of data from six randomized controlled trials. J Pain Res 2016, 9, 941–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babaahmadi M, Tayebi B, Gholipour NM, Kamardi MT, Heidari S, Baharvand H, Eslaminejad MB, Hajizadeh-Saffar E, Hassani SN. Rheumatoid arthritis: the old issue, the new therapeutic approach. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023 Sep 23;14(1):268. [CrossRef]

- Altman, R.; Asch, E.; Bloch, D.; Bole, G.; Borenstein, D.; Brandt, K.; Christy, W.; Cooke, T.D.; Greenwald, R.; Hochberg, M.; et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum 1986, 29, 1039–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ploynumpon, P.; Wilairatana, V.; Chompoosang, T. Efficacy of a Combined Periarticular and Intraosseous Multimodal Analgesic Injection Technique in Simultaneous Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cureus 2024, 16, e53946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.D.; McGrath, P.A.; Rafii, A.; Buckingham, B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 1983, 17, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faucher, M.; Poiraudeau, S.; Lefevre-Colau, M.M.; Rannou, F.; Fermanian, J.; Revel, M. Assessment of the test-retest reliability and construct validity of a modified Lequesne index in knee osteoarthritis. Joint Bone Spine 2003, 70, 521–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, S.; Ford, A.B.; Moskowitz, R.W.; Jackson, B.A.; Jaffe, M.W. Studies of illness in the aged: The index of ADL: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963, 185, 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, C.; Yang, F.; Liu, L. Effectiveness of Continuous Care Interventions in Elderly Patients with High-Risk Pressure Ulcers and Impact on Patients’ Activities of Daily Living. Altern Ther Health Med 2024, 30, 118–123. [Google Scholar]

- Clynes, M.A.; Jameson, K.A.; Edwards, M.H.; Cooper, C.; Dennison, E.M. Impact of osteoarthritis on activities of daily living: does joint site matter? Aging Clin Exp Res 2019, 31, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraru, M.V.; Stoleru, S.; Zugravu, A.; Coman, O.A.; Fulga, I. New Insights Into Pharmacology of GABAA Receptor Alpha Subunits-Selective Modulators. Am J Ther 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroianu, G.A.; Aloum, L.; Adem, A. Neuropathic pain: Mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023, 11, 1072629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giombini, A.; Menotti, F.; Di Cesare, A.; Giovannangeli, F.; Rizzo, M.; Moffa, S.; et al. Comparison between intrarticular injection of hyaluronic acid, oxygen ozone, and the combination of both in the treatment of knee osteoarthrosis. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents 2016, 30, 621–625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aurelian S, Ciobanu A, Cărare R, Stoica SI, Anghelescu A, Ciobanu V, Onose G, Munteanu C, Popescu C, Andone I, Spînu A, Firan C, Cazacu IS, Trandafir AI, Băilă M, Postoiu RL, Zamfirescu A. Topical Cellular/Tissue and Molecular Aspects Regarding Nonpharmacological Interventions in Alzheimer’s Disease-A Systematic Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 Nov 20;24(22):16533. [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Cao, Z.; Shariff, M.; Gu, P.; Nguyen, T.; Zhou, T.; Shi, R.; Rao, J. Effects of G.H.3. On mental symptoms and health-related quality of life among older adults: results of a three-month follow-Up study in Shanghai, China. Nutr J 2016, 15, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostfeld, A.; Smith, C.M.; Stotsky, B.A. The systemic use of procaine in the treatment of the elderly: a review. J Am Geriatr Soc 1977, 25, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramaglia, C.; Gattoni, E.; Marangon, D.; Concina, D.; Grossini, E.; Rinaldi, C.; Panella, M.; Zeppegno, P. Non-pharmacological Approaches to Depressed Elderly With No or Mild Cognitive Impairment in Long-Term Care Facilities. A Systematic Review of the Literature. Front Public Health 2021, 9, 685860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.J.; Areerob, P.; Hennessy, D.; Gonçalves-Bradley, D.C.; Mesagno, C.; Grace, F. Aerobic, resistance, and mind-body exercise are equivalent to mitigate symptoms of depression in older adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. F1000Res 2020, 9, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraaijkamp, J.J.M.; van Dam van Isselt, E.F.; Persoon, A.; Versluis, A.; Chavannes, N.H.; Achterberg, W.P. eHealth in Geriatric Rehabilitation: Systematic Review of Effectiveness, Feasibility, and Usability. J Med Internet Res 2021, 23, e24015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghinescu, M.; Olaroiu, M.; Aurelian, S.; Halfens, R.J.; Dumitrescu, L.; Schols, J.M.; Rahnea-Nita, G.; Curaj, A.; Alexa, I.; van den Heuvel, W.J. Assessment of care problems in Romania: feasibility and exploration. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015, 16, 86–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.; Dai, M.; Xu, P.; Sun, L.; Shu, X.; Xia, X.; Zhao, Y.; Song, Q.; Guo, D.; Deng, C.; Yue, J. Prevalence of Sarcopenia in Pain Patients and Correlation Between the Two Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2022, 23, 902–e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveria, S.A.; Felson, D.T.; Reed, J.I.; Cirillo, P.A.; Walker, A.M. Incidence of symptomatic hand, hip, and knee osteoarthritis among patients in a health maintenance organization. Arthritis Rheum 1995, 38, 1134–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrich, J.; Piribauer, F.; Mad, P.; Schmid, D.; Klaushofer, K.; Müllner, M. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2005, 172, 1039–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camanho, G.L.; Imamura, M.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Genesis of pain in arthrosis. Rev Bras Ortop 2015, 46, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recommendations for the medical management of osteoarthritis of the hip and knee: 2000 update. American College of Rheumatology Subcommittee on Osteoarthritis Guidelines. Arthritis Rheum 2000, 43, 1905–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, D.; Chard, J.; Dieppe, P. Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet 2000, 355, 2037–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, K.M.; Arden, N.K.; Doherty, M.; Bannwarth, B.; Bijlsma, J.W.; Dieppe, P.; Gunther, K.; Hauselmann, H.; Herrero-Beaumont, G.; Kaklamanis, P.; Lohmander, S.; Leeb, B.; Lequesne, M.; Mazieres, B.; Martin-Mola, E.; Pavelka, K.; Pendleton, A.; Punzi, L.; Serni, U.; Swoboda, B.; Verbruggen, G.; Zimmerman-Gorska, I.; Dougados, M.; Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials ESCISIT. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: Report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis 2003, 62, 1145–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghea, F.; Berghea, C.E.; Zaharia, D.; Trandafir, A.I.; Nita, E.C.; Vlad, V.M. Residual Pain in the Context of Selecting and Switching Biologic Therapy in Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 712645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, D.J.; Felson, D.T. Osteoarthritis. BMJ 2006, 332, 639–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, T.C.; Adams, M.J.; Mulliken, B.D.; Dalury, D.F. Efficacy of multimodal perioperative analgesia protocol with periarticular medication injection in total knee arthroplasty: a randomized, double-blinded study. J Arthroplasty 2013, 28, 1274–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Teng, Y.; Fan, Z.; Khan, M.S.; Cui, Z.; Xia, Y. The efficacy of periarticular multimodal drug injection for postoperative pain management in total knee or hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2013, 28, 1882–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).