1. Introduction

Malnutrition is a widespread issue among the old people across various care settings, significantly impacting health outcomes. Studies have shown that the prevalence of malnutrition varies depending on diagnostic criteria and care settings. For instance, research indicates that up to 18.2% of nursing home residents are malnourished, with higher rates observed when age-specific criteria are used [

1] Additionally, among hospitalized old people patients, the risk of malnutrition is strongly associated with higher mortality rates and longer hospital stays [

2].

Nutritional interventions aimed at countering protein-energy malnutrition have shown promising results in improving health outcomes among the old people. An aggregated analysis of several randomized clinical trials (RCTs) demonstrated that dietary counseling combined with oral nutritional supplementation (ONS) significantly increased energy intake and body weight among older adults at risk of malnutrition [

3]. Furthermore, short-term protein supplementation during rehabilitation improved dietary protein intake and physical recovery, although more robust studies are needed to confirm these findings [

4].

The role of caregivers and healthcare workers is crucial for the success of nutritional interventions. Education and education for healthcare workers can significantly enhance nutritional care practices. For example, an interprofessional approach that includes staff education has been shown to improve nutritional outcomes in hospitals and long-term care facilities [

5]. Additionally, patient nutritional education combined with physical exercise has been found to be more effective than nutritional interventions alone in improving frailty and physical performance in older adults [

6].

Several studies highlight gaps in nutritional care due to inadequate education and education among healthcare workers [

7,

8,

9]. Poor nutritional knowledge and negative attitudes towards nutritional care are common issues. A study on the nutritional status of old people patients in geriatric rehabilitation revealed that malnutrition is often inadequately addressed, partly due to insufficient education among healthcare workers [

10]. Moreover, a systematic review found that nutritional interventions in hospitals and long-term care facilities are more effective when combined with comprehensive staff education and an interprofessional approach [

5].

The role of continuing education is emphasized in recent work by Castaldo and Patel [

11,

12], which identified a strong link between malnutrition interventions and healthcare worker education. This study found that healthcare workers with specialized education on malnutrition had significantly more positive attitudes toward personalized care, reinforcing the idea that education is essential for effective interventions. However, the study also highlighted persistent gaps in nutritional knowledge and the need for broader educational initiatives to ensure consistency in care across different healthcare settings.

Furthermore, Johnston [

9] demonstrated that structured educational programs for healthcare workers in dementia wards significantly improved the nutritional status of residents in care facilities. Their findings align with our observations, during the study, emphasizing the need for practical learning approaches that incorporate tools like the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) [

14] and food diaries. These tools not only enhance care but also help healthcare workers better understand and address the unique nutritional challenges faced by the old people.

Despite the focus on interventions such as ONS supplementation and integration, there remains a gap in addressing the attitudinal competencies of healthcare workers regarding malnutrition. Literature often concentrate on the technical aspects of nutritional interventions but overlook the importance of attitudinal change through education [

12]. Therefore, to be effective, interventions should integrate both knowledge-based and attitudinal education to ensure that healthcare workers can confidently address malnutrition in the frail old people populations [

13].

2. Materials and Methods

This study aims to assess healthcare workers' attitudes and practices regarding old people nutrition through the application of the Italian version of the SANN-G questionnaire, developed by Bonetti [

15], which has been validated for use in Italian healthcare settings. The study focuses on healthcare workers employed in nursing homes in Northern Italy.

Healthcare workers from various professional roles, including nurses, nursing assistants, and physicians, were recruited from several nursing homes in Northern Italy. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were assured of the anonymity of their responses. The inclusion criteria for participants were:

(1) employment in a healthcare role within a nursing home and

(2) direct provision of care to old people residents.

No exclusion criteria were applied based on professional roles, including all care workers employed in nursing homes.

Data collection was conducted using the Italian version of the SANN-G questionnaire, which evaluates healthcare workers' attitudes, knowledge, and practices regarding old people nutrition. This questionnaire consists of 18 items with a five-option Likert-type Scale (1 = completely agree, 2 = agree, 3 = doubtful, 4 = disagree and 5 = completely disagree). The cut-off score for negative attitudes is <54 points, while a score ≥ 72 reflected positive attitudes. A cut-off score for positive attitudes can be obtain also for each dimension. The questionnaire includes several sections covering key areas such as (cut-off for positive attitudes in brackets):

Norms: Attitudes toward nutritional standards and guidelines in old people care (≥ 20):

Habits: Routine nutritional practices and interventions (≥ 16);

Assessment: Approaches to nutritional screening and monitoring (≥ 16);

Intervention: Strategies for managing malnutrition and associated nutritional risks (≥ 12);

Intervention: interventions needed to manage the disorders linked to malnutrition (≥ 12);

Individualization: Adaptation of nutritional care to meet the individual needs of patients (≥ 8).

The SANN-G questionnaire was administered both online and in paper format, depending on participant preference. The online survey was distributed via a secure link to the “Sondaggi.unige.it” server, which ensured encrypted and protected data acquisition. Paper versions were made available at the workplace and collected by designated coordinators. Both methods ensured participant anonymity, with no identifying information being requested or recorded.

Data were collected between 2019 and 2023, with a total of 1789 healthcare workers participating in the survey. All participants provided written informed consent before completing the questionnaire. The survey was designed to take approximately 20 minutes, and participants were given adequate time to provide accurate and thoughtful responses.

All survey responses, both online and paper-based, were digitized and compiled into a single dataset for analysis. Data analysis was performed using the statistical software R [

16], an open-source environment widely used for statistical computation and data analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated to summarize the demographic characteristics of the sample, such as gender, age, professional role, and years of experience in old people care.

In addition to descriptive statistics, inferential analyses were conducted to examine the relationships between healthcare workers' demographic characteristics and their attitudes toward old people nutrition. Chi-square tests were used to assess associations between categorical variables and the SANN-G scores. The significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Scatter plots were generated to visually assess the distribution of responses across the main attitudinal dimensions, including norms, habits, assessment, intervention, and individualization. Additionally, contingency tables were used to explore interactions between variables such as professional education on malnutrition and corresponding attitudinal scores. The results of these analyses were used to identify trends and outliers, providing a comprehensive understanding of healthcare workers' attitudes toward old people nutritional care.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval for the study was obtained from the Regional Ethics Committee of Liguria (ID 11116 - No. 677/2020). All participants provided informed consent prior to participation, and no personally identifiable information was collected.

3. Results

The analysis of the SANN-G project, conducted across 41 nursing homes with a sample of 1,789 participants, primarily aimed to examine healthcare workers' attitudes toward old people nutrition. Descriptive statistics revealed that the majority of respondents were female (68.59%) and aged between 41 and 50 years (33.31%). Various professional roles were represented, with nursing assistants comprising the largest group (35.83%) (

Table 1).

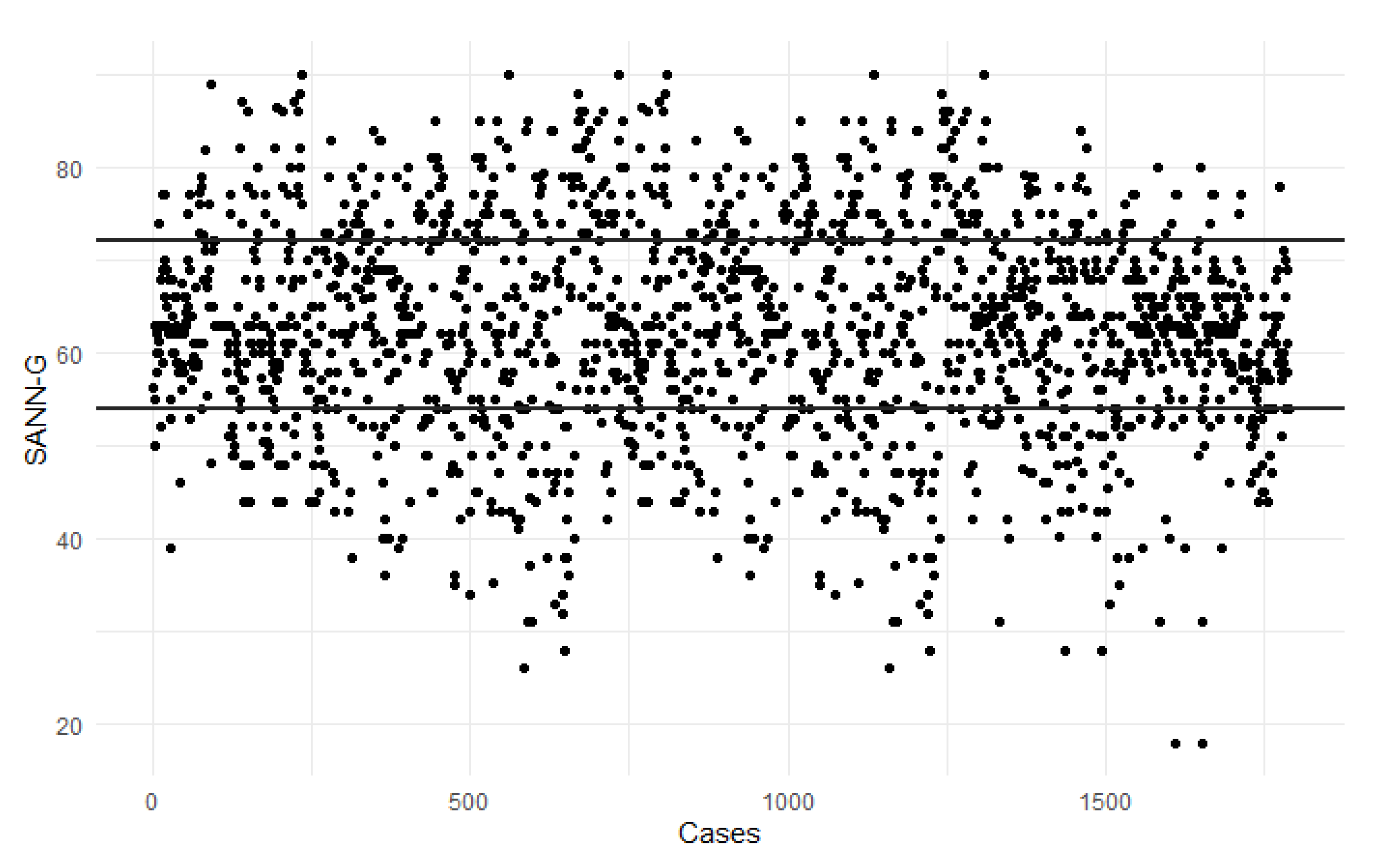

We chose to use scatter plots to visually illustrate the distribution of attitudes, allowing for easy identification of patterns, outliers, and general trends. Scatter plots help in understanding the concentration of attitudes across different scales, revealing nuances in responses that simple statistical tables might not capture.

In the SANN-G analysis, scatter plots were employed to visually represent the distribution of attitudes across various study dimensions, including nutritional norms, habits, assessment, intervention, and individualization. These plots provided a clear visual differentiation among participants with positive, negative, or neutral attitudes, highlighting where the majority of the sample fell within each category.

Attitudes were measured across several dimensions, such as norms, habits, assessment, intervention, and individualization. Positive attitudes toward personalization and individualized care for old people patients were particularly prevalent among younger respondents and healthcare workers who had received specialized education. However, only 23.48% of respondents achieved an overall positive score on the SANN-G scale, indicating that a significant portion of the sample still held neutral or negative attitudes toward old people nutritional care (

Figure 1).

The scatter plot for nutritional standards revealed that only a small percentage of respondents scored positively (≥20), with the majority reflecting more neutral or negative attitudes. In contrast, for habits, half of the participants (50.42%) demonstrated positive attitudes (≥16), suggesting a more balanced view in this area. In the analysis of assessment, fewer than half (40.02%) of the participants achieved a positive score (≥16), indicating that the majority held more conservative or neutral views regarding nutritional assessment practices.

In terms of intervention, the scatter plot showed that approximately half of the respondents (48.69%) achieved a positive score (≥12), indicating mixed opinions on the application of active intervention strategies. However, the individualization dimension stood out, with more than half (54.95%) of respondents scoring positively (≥8), suggesting stronger support for personalized care in old people nutrition.

Contingency tables in the SANN-G analysis were used to examine the relationships between respondent characteristics (such as gender, age, professional role, and whether they had completed specific malnutrition education) and their attitudes toward old people nutritional care. These tables provided insights into the statistical significance of these relationships and highlighted key demographic and professional factors influencing attitudes.

The contingency table (

Table 2) indicate that there is no significant difference in responses based on the gender of the respondents. However, a significant difference emerges with respect to age. Respondents aged 31–40 and 51–60 years displayed a significantly higher percentage of positive attitudes towards the guidelines (p = .002). Additionally, a variation in responses was observed based on professional roles. Nurses and other healthcare professionals, compared to physicians and support staff, exhibited a significantly higher percentage of positive attitudes towards the guidelines (p <.001). Furthermore, completing a specialized course on malnutrition had a significant impact, as those who participated in such a course demonstrated a significantly higher percentage of positive attitudes towards the guidelines (p <.001). Contingency tables for each single dimension of the SANN-G scale are reported in Supplementary Tables (Appendix 1).

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess healthcare workers’ attitude toward old people nutrition. The role of continuous education for healthcare professionals in improving nutritional care for frail old people patients is well-documented across several studies. This study provides some insights into the impact of continuous education on healthcare workers' attitudes toward old people nutrition in long-term care facilities, highlighting the necessity of targeted educational interventions. The findings align with a growing body of international research that underscores the critical role of healthcare worker training in addressing malnutrition among old people populations—a persistent global public health challenge [

3,

4]. The study by Castaldo et al. [

11] further supports the importance of continuous education, showing that healthcare workers who had received specific malnutrition education exhibited significantly more positive attitudes toward nutritional interventions compared to those without such education. Similar to our findings, the majority of healthcare workers initially displayed neutral or negative attitudes toward old people nutrition, but those with formal education demonstrated a clear shift toward more proactive and personalized care. This is consistent with the evidence from Johnston [

9] which highlighted the role of structured education in improving nutritional outcomes for patients with dementia. Their study showed that professionals learned to better assess and address nutritional deficiencies using tools like the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and detailed food diaries, leading to improved patient energy intake and nutritional status.

Our analysis revealed significant disparities in attitudes toward old people nutrition based on factors such as professional role, age, and prior training. Giving sensitive interventions can lead to better quality of life for patients and cost savings in nursing homes [

21,

22]. Notably, healthcare workers who had undergone specific training in malnutrition exhibited significantly more positive attitudes toward nutritional care, particularly in areas like assessment, intervention, and individualization. These results are consistent with prior studies [

9,

11] that highlight the transformative potential of education in enhancing healthcare practices. Younger healthcare workers and nursing staff were found to have more favorable attitudes toward proactive nutritional intervention, emphasizing the importance of integrating continuous education early in a professional’s career.

Moreover, our findings suggest that professional roles and demographic factors, such as age and experience, play a significant role in shaping attitudes toward old people nutrition. For example, physicians were found to have less favorable attitudes toward personalized nutritional interventions compared to nurses and healthcare assistants, indicating the need for more interdisciplinary collaboration and education. The study conducted by Thomson [

17] adds a critical dimension to this discussion. Their systematic review examined the effectiveness of oral nutritional supplements (ONS) for frail old people populations, finding that outcomes often depended on staff education levels and the consistency in applying intervention protocols. While nutritional supplements showed potential benefits in terms of energy intake and mobility, their research implies that a successful intervention hinged on the healthcare workers' ability to effectively implement the interventions, something that can only be achieved through comprehensive and ongoing education. Without adequate education, even well-designed nutritional programs may fail to yield significant results.

Multidisciplinary approaches, as demonstrated in the study by Beck [

18], further highlight the need for education that involves various healthcare roles. Their randomized trial showed that the involvement of dietitians, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists in old people care led to significant improvements in quality of life, muscle strength, and oral care. The success of these interventions underscores the importance of interdisciplinary education, ensuring that all healthcare team members are aligned in their approach to nutritional care. This mirrors our findings, where trained staff were more engaged and displayed a greater inclination toward individualized and collaborative care strategies.

However, it is important to acknowledge the limitations within the existing body of evidence. For example, Brown and Copeman [

19] did not find a statistically significant relationship between increased nutritional knowledge and actual improvements in residents' diets. This suggests that while education is critical, it must be accompanied by strategies that translate knowledge into sustained practices. In some cases, repeated exposure to education and practical tools, such as food diaries or nutritional assessments, may be necessary to reinforce behavioral changes among healthcare workers [

9].

In countries facing rapid population aging, healthcare systems must prioritize continuing education for healthcare workers in geriatrics. Policymakers should consider allocating resources to education programs that specifically address nutritional care, an area that is often overlooked in favor of other medical interventions. Ongoing research, such as the COFRAIL trial [

20], underscores the potential for involving families and caregivers in nutritional interventions. This trial aims to evaluate whether shared decision-making through family conferences can improve patient safety and care outcomes for frail old people individuals. Although still in progress, the study reflects a growing awareness that education should not be limited to healthcare workers but should also extend to families and caregivers to ensure a more holistic approach to care. Integrating families into the care process could amplify the effects of professional education, fostering a shared commitment to improving nutritional health outcomes.

Some limitations should be considered. First, this was a descriptive analysis of data collected through a survey, thus a real cause-effect relationship could not be assessed. Moreover, a social desirability bias may exist, thus respondents may have given responses that they thought were more socially acceptable, rather than their true attitudes. Generalizability of these results cannot be granted, as the healthcare providers who participated in this study were recruited from 41 healthcare facilities in six Italian regions out of 21.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, improving old people nutritional care requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates education, interdisciplinary collaboration, and policy support. As this study demonstrates, healthcare workers equipped with the right knowledge and positive attitudes are more likely to implement effective nutritional interventions, leading to better health outcomes for old people populations worldwide. International health organizations and national healthcare systems should take note of these findings and promote continuous education as a cornerstone of geriatric care to combat the global issue of malnutrition in older adults.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: preprints.org, Contingency Table S1.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conceptualization

Milko Zanini and Annamaria Bagnasco; Data curation, Milko Zanini and Marco Di Nitto; Formal analysis, Milko Zanini, Marco Di Nitto and Stefania Ripamonti; Investigation, Milko Zanini, Lara Delbene and Maria Musio; Methodology, Milko Zanini; Resources, Milko Zanini; Software, Marco Di Nitto; Supervision, Milko Zanini and Annamaria Bagnasco; Validation, Milko Zanini, Gianluca Catania and Annamaria Bagnasco; Visualization, Milko Zanini and Annamaria Bagnasco; Writing – original draft, Milko Zanini, Marco Di Nitto, Lara Delbene, Stefania Ripamonti and Maria Musio; Writing – review & editing, Milko Zanini and Marco Di Nitto.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Approval for the study was obtained from the Regional Ethics Committee of Liguria (ID 11116 - No. 677/2020). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval for the study was obtained from the Regional Ethics Committee of Liguria (ID 11116 - No. 677/2020).

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation, and no personally identifiable information was collected.

Data availability status

the data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and legal reasons.

Acknowledgments

Authors want to acknowledge all the support given by Healthy Ageing Research Group (HARG SB) and all health care workers in the Nursing Homes that have taken part in the study .

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Wolters, M., Volkert, D., Streicher, M., Kiesswetter, E., Torbahn, G., O'Connor, E., O’Keeffe, M., Kelly, M., O'Herlihy, E., O’Toole, P., Timmons, S., O’Shea, E., Kearney, P., Zwienen-Pot, J., Visser, M., Maître, I., Wymelbeke, V., Sulmont-Rossé, C., Nagel, G., Flechtner-Mors, M., Goisser, S., Teh, R., & Hebestreit, A. (2019). Prevalence of malnutrition using harmonized definitions in older adults from different settings - A MaNuEL study. Clinical nutrition. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T., Matsumoto, M., Haraguchi, Y., Ishida, T., & Momomura, S. (2020). Prognostic impact of malnutrition assessed using geriatric nutritional risk index in patients aged ⩾80 years with heart failure. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 19, 172 - 177. [CrossRef]

- Reinders, I., Volkert, D., Groot, L., Beck, A., Feldblum, I., Jobse, I., Neelemaat, F., Schueren, M., Shahar, D., Smeets, E., Tieland, M., Twisk, J., Wijnhoven, H., & Visser, M. (2019). Effectiveness of nutritional interventions in older adults at risk of malnutrition across different health care settings: Pooled analyses of individual participant data from nine randomized controlled trials. Clinical nutrition, 38 4, 1797-1806. [CrossRef]

- Strasser, B., Grote, V., Bily, W., Nics, H., Riedl, P., Jira, I., & Fischer, M. (2023). Short-Term Effects of Dietary Protein Supplementation on Physical Recovery in Older Patients at Risk of Malnutrition during Inpatient Rehabilitation: A Pilot, Randomized, Controlled Trial. Healthcare, 11. [CrossRef]

- Brunner S, Mayer H, Qin H, Breidert M, Dietrich M, Müller Staub M. Interventions to optimise nutrition in older people in hospitals and long-term care: Umbrella review. Scand J Caring Sci. 2022 Sep;36(3):579-598. doi: 10.1111/scs.13015. Epub 2021 Jul 1. PMID: 34212419; PMCID: PMC9545538.

- Khor, P., Vearing, R., & Charlton, K. (2021). The effectiveness of nutrition interventions in improving frailty and its associated constructs related to malnutrition and functional decline among community-dwelling older adults: A systematic review. Journal of human nutrition and dietetics: the official journal of the British Dietetic Association. [CrossRef]

- James, M. (2023). The Lack of Nutritional Competency among the Medical Practitioners and Medical Students: A Systematic Review. European Journal of Nutrition & Food Safety. [CrossRef]

- Crowley, J., Ball, L., & Hiddink, G. (2019). Nutrition in medical education: a systematic review.. The Lancet. Planetary health, 3 9, e379-e389 . [CrossRef]

- Johnston, E., Mathews, T., Aspry, K., Aggarwal, M., & Gianos, E. (2019). Strategies to Fill the Gaps in Nutrition Education for Health Professionals through Continuing Medical Education. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 21, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Wojzischke, J., Wijngaarden, J., Berg, C., Cetinyurek-Yavuz, A., Diekmann, R., Luiking, Y., & Bauer, J. (2020). Nutritional status and functionality in geriatric rehabilitation patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Geriatric Medicine, 11, 195-207. [CrossRef]

- Castaldo A, Bassola B, Zanetti ES, Nobili A, Zani M, Magri M, Verardi AA, Ianes A, Lusignani M, Bonetti L. Nursing Home Organization Mealtimes and Staff Attitude Toward Nutritional Care: A Multicenter Observational Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2024 May;25(5):898-903. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2023.10.011. Epub 2023 Nov 18. PMID: 37989497.

- Patel, P., & Kassam, S. (2021). Evaluating nutrition education interventions for medical students: A rapid review. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 35, 861 - 871. [CrossRef]

- Cereda E. Mini nutritional assessment. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2012 Jan;15(1):29-41. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32834d7647. PMID: 22037014.

- Roberts, S., Collins, P., & Rattray, M. (2021). Identifying and Managing Malnutrition, Frailty and Sarcopenia in the Community: A Narrative Review. Nutrients, 13. [CrossRef]

- Bonetti L, Bagnasco A, Aleo G, Sasso L. Validation of the Staff Attitudes to Nutritional Nursing Care Geriatric scale in Italian. Int Nurs Rev. 2013 Sep;60(3):389-96. doi: 10.1111/inr.12033. Epub 2013 Jul 26. PMID: 23961802.

- R Core Team (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

- Thomson K, Rice S, Arisa O, Johnson E, Tanner L, Marshall C, Sotire T, Richmond C, O'Keefe H, Mohammed W, Gosney M, Raffle A, Hanratty B, McEvoy CT, Craig D, Ramsay SE. Oral nutritional interventions in frail older people who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess. 2022 Dec;26(51):1-112. doi: 10.3310/CCQF1608. PMID: 36541454; PMCID: PMC9791461.

- Beck AM, Christensen AG, Hansen BS, Damsbo-Svendsen S, Møller TK. Multidisciplinary nutritional support for undernutrition in nursing home and home-care: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Nutrition. 2016 Feb;32(2):199-205. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2015.08.009. Epub 2015 Sep 3. PMID: 26553461.

- Brown, L.E. and Copeman, J. (2008), Nutritional care in care homes: experiences and attitudes of care home staff. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 21: 383-383. [CrossRef]

- Mortsiefer A, Löscher S, Pashutina Y, Santos S, Altiner A, Drewelow E, Ritzke M, Wollny A, Thürmann P, Bencheva V, Gogolin M, Meyer G, Abraham J, Fleischer S, Icks A, Montalbo J, Wiese B, Wilm S, Feldmeier G. Family Conferences to Facilitate Deprescribing in Older Outpatients With Frailty and With Polypharmacy: The COFRAIL Cluster Randomized Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Mar 1;6(3):e234723. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.4723. PMID: 36972052; PMCID: PMC10043750.

- Zanini M, Catania G, Ripamonti S, Watson R, Romano A, Aleo G, Timmins F, Sasso L, Bagnasco A. The WeanCare nutritional intervention in institutionalized dysphagic older people and its impact on nursing workload and costs: A quasi-experimental study. J Nurs Manag. 2021 Nov;29(8):2620-2629. doi: 10.1111/jonm.13435. Epub 2021 Aug 17. PMID: 34342076; PMCID: PMC9292428.

- Zanini M, Bagnasco A, Catania G, Aleo G, Sartini M, Cristina ML, Ripamonti S, Monacelli F, Odetti P, Sasso L. A Dedicated Nutritional Care Program (NUTRICARE) to reduce malnutrition in institutionalised dysphagic older people: A quasi-experimental study. J Clin Nurs. 2017 Dec;26(23-24):4446-4455. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13774. Epub 2017 Apr 11. PMID: 28231616.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).