Introduction

Matching into a U.S. general surgery categorical residency program is highly competitive and challenging. In 2023, 355 programs offered 1,670 positions while receiving 3,100 certified rank lists, including those from international medical schools [

1]. The match rate for US allopathic medical students (USMD) was 72%, osteopathic medical students (DO) was 56%, and international medical graduates (IMGs) was 12% [

2]. The evaluation process for residents is not standardized across programs. Each program independently evaluates, interviews, and ranks candidates based on its unique culture, mission, resources, and level of desirability.

Recent changes in the match process have potentially altered the calculus of the match for applicants and programs. Firstly, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, nearly all programs transitioned from in-person to virtual interview formats [

3]. This shift, while reducing the financial and time burdens, allowed applicants to interview more broadly due to drastically lower costs. However, for residency training programs, organizing interviews remains a substantial logistical and financial undertaking [

4].

Secondly, as of January 2022, the USMLE Step 1 exam, an important metric in distinguishing applicants, transitioned from continuously scored to pass/fail [

5]. Starting with the 2024 application cycle, only USMLE Step 2 scores are available [

6]. How programs will adapt to the loss of this standardized objective metric remains to be determined.

Each surgical training program possesses a distinct character and mission, whether academic, independent, research-oriented, rural, or urban. While we do not anticipate deriving generalizable conclusions that will assist residents in matching with any specific program, an analysis of the match process might alleviate some of the unique anxieties associated with graduate medical education. This study examined the predictors of obtaining an interview invitation (II) using a publicly available, self-reported dataset spanning five years, from before the pandemic in 2020 to the first year of pass/fail reporting for the USMLE Step 1 exam in 2024. We aimed to describe the changes in the match process over the last several years and to identify factors influencing the likelihood of receiving an II. IIs are an established proxy for successful matching, as the number of contiguous ranks closely correlates with the probability of matching into a residency [

7].

Methods

Data for this study was sourced from a publicly available, self-reported residency match tool published on Google Sheets, currently managed by author A.G., covering the residency application years 2020 to 2024 [

8]. This resource is utilized globally by students. The database contains no identifiers such as names, ages, location, or gender. Each application year's data is managed by different moderators, resulting in slight variations in the available metrics. While some data for 2019 was available, nearly all our measured independent variables were not collected; thus, that year was excluded. This database also included copious comments, advice, messages, and links to a popular messaging channel. While not quantifiable, this information provided unfiltered insight into some students' concerns about the match process.

The available data included type of medical school (allopathic versus osteopathic), graduation year, USMLE Step 1 and Step 2 scores, class quartile rank, Alpha Omega Alpha (AOA) and Gold Humanism Honor Society (GHHS) membership status, grades, number of publications and volunteer experiences, couples match status, research, number of invitations received, IMG status, signaling information, and the grading system of the medical school (e.g., pass/fail). We could not reliably distinguish between US IMG and non-US IMG students. As not every applicant completed every survey category, the number of respondents to any category might not always add up to 1117. The gender of the applicant was not a captured variable.

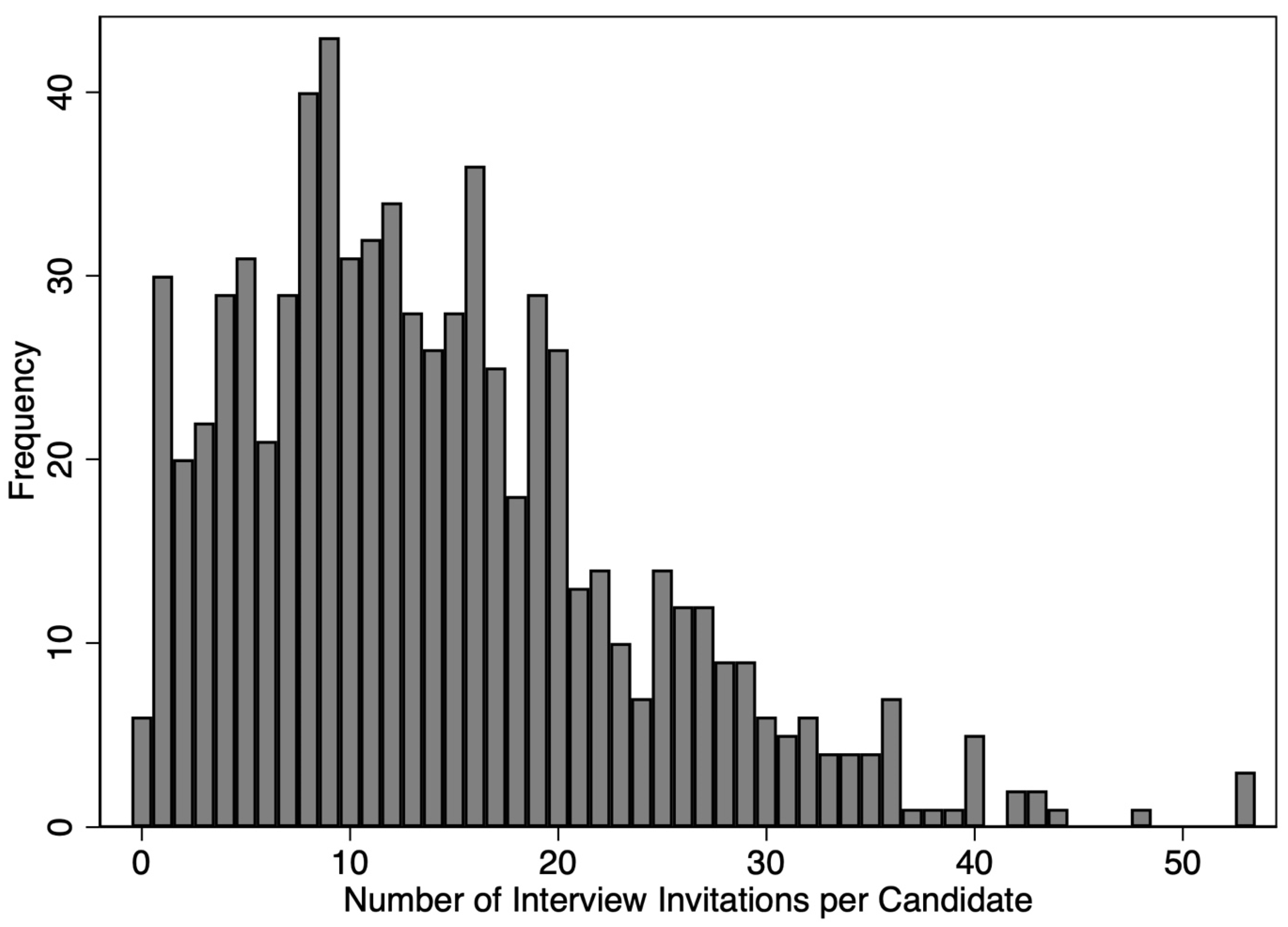

We created a multivariable tobit regression, designating the number of IIs as the dependent variable. A left-censored regression was used as the number of invitations was significantly skewed, Fig. 1. Initial analysis also revealed a nonlinear relationship between USMLE scores and the number of invitations at extremes of score. This effect was determined to negligibly affect the model's final results. Categorical variables included the application year, AOA and GHHS status, student type (DO, USMD, IMG), class rank, presence of a gap year (none or more than one year), school tier (top 10% vs. other), and honors in surgery (yes, no, or pass/fail). Statistical significance was determined at the p<0.05 level. Institutional Review Board (IRB) exempt status was secured for this study. Means are reported with standard error and 95% confidence intervals. We used the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to compare the overall error of statistical models. All calculations were performed using Stata 18.0 (College Station, TX).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the number of interview invitations. 33% of candidates had more than 18 interview invitations, predicting a 99% probability of matching.

Figure 1.

Distribution of the number of interview invitations. 33% of candidates had more than 18 interview invitations, predicting a 99% probability of matching.

Results

Between the academic years of 2020 and 2024, 1,117 applications to general surgery categorical residency programs were analyzed: 70% were USMD, 16% were DO, and 14% were IMG

Table 1. The percentage of IMGs represented in the database from 2020-2024 was 11%, 14%, 10%, 12%, and 20%, respectively. The applicant characteristics are further detailed in

Table 2 and

Table 3.

The Number of Applications Sent Out by Each Applicant Significantly Increased over the Past Five Years

The number of applications per applicant increased every year from 2020 until 2024. The mean number of applications submitted by each student was highly dependent on the student type (IMG>>DO>MD) when examining both the unadjusted data (

Table 1) and controlling for all other factors (DO 28.45, p<0.0001; IMG 64.8, p<0.0001 compared to USMD). Over the time period, applications submitted per candidate increased by 32%, from 78.0±3.8 in 2020 to 103±3.2 in 2024. When excluding IMGs, the number of applications per US candidate (DO combined with USMD) increased by 26%. Controlling for student type, 2023 and 2024 still saw significantly greater applications per student than the prior years. Lower USMLE2 scores correlated with more applications submitted (-0.97±0.11, p<0.0001).

USMLE 2 Scores After USMLE 1 Scoring Elimination Does Not Affect the Predictive Model

In a multivariable analysis, USMLE1 scores were predicted by higher class rank (each lower quartile decreased score, p<0.002), honors in surgery (7.3±1.4, p<0.0001), but not number of publications, tier of medical school, gap years, or student category.

The relationship between USMLE2 and IIs was nonlinear, with inflection points in IIs below a USMLE2 score of 245 and above a USMLE of 265 with a relatively flat area between. Using our multivariable regression model to identify predictors of IIs (

Table 4), USMLE1 and USMLE2 were equivalent in predicting IIs (

Table 4) as the coefficients for the statistical model for USMLE1 and USMLE2 were nearly identical (0.15 and 0.17, respectively). Repeating the statistical model without including USMLE1 as an independent variable, the coefficient for USMLE2 increased to 0.27. This model with only USMLE2 had no difference in the quality of the fit (AIC 3379 vs. 3471), suggesting they were statistically interchangeable. The USMLE2 score alone replaced the combination of USMLE scores without any other changes to the coefficients or significance of the other independent variables. This might have been due to the significant cross-interaction between the scores (p=0.007), the correlations between scores (r=0.67), or the other proxies available to program evaluators for academic performance.

The Relationship Between Applications Submitted and Interview Invites Varied by Applicant Type

In 2024, despite an increase in applications per candidate, the number of invitations received decreased by an average of eight from the base year 2020. (

Table 2). The average number of interview invites received varied by student type, with USMD students receiving an average of 15.8±0.41, DO students 12.6±0.82, and IMG students significantly fewer at 5.0±0.49. For 2023 and 2024, when signaling was first available, signaled programs yielded a 68%±2 (64-72) II rate of IIs. The percent II yield (IIs/applications) for USMD, DO, and IMG students over the entire study period was 25%±0.06, 14%±0.008, and 3.9%±0.005, respectively. Over the study period, the yield for USMDs decreased from 31%±0.19 in 2020 to 19.5%±0.01 in 2024.

Using our multivariable model, the student type significantly predicted the number of IIs received (p<0.0001). IMG students received markedly fewer invitations than US and DO students, even when controlling for all other factors. There was no measurable correlation for IMGs between the number of applications and interviews received. For USMD and DO students, there was a quadratic relationship between the number of applications submitted and IIs.

Increasing class rank, self-reported into quartiles, was a significant predictor of more IIs, with the lowest quartile receiving 7.3±2.5 fewer invitations than the highest quartile. Receiving honors in surgery predicted obtaining 1.2±0.9 more IIs, p=0.003. Students who went to schools that did not offer honors (i.e., pass-fail) were treated as if they did not get honors. Any gap in time between graduation and application submission negatively affected the number of invitations (except for IMG students). Graduating from the highest-tier medical schools (top ten percent) had a minimal impact on the number of invitations (2.13, p=0.05). Variables that did not predict the number of IIs included the number of publications, GHHS membership (except for the year 2024), and participating in a couple's match.

Discussion

From 2020 to 2024, we document a 32% increase in applications per candidate and a corresponding decrease in interview invitations. The remarkable change in applicant behavior correlates with the drastically lower cost (both in time and money) of applying with the transition to virtual interviews [

9,

10]. Applicants are incentivized to apply broadly, anxious about the career risks of not matching. Our independent program, for instance, used to receive 700-800 applicants a year before the pandemic, and since 2021, we have received 2000 candidates a year for four positions.

The change in application volume might alter a program’s selection behavior. Some programs might be unable to review thousands of applications diligently with their current resources, while some might have increased the number of interviews. Others might have changed the calculus for interview selection. Previously, the candidate’s cost to interview indicated earnest interest and a program could reliably rank from their top applicants. Now, as the average student applies to nearly one-third of all programs, programs might seek candidates who would likely rank them highly instead of being the most competitive. So, traditional metrics such as USMLE scores or grades might have a decreased weight relative to declared geographic preference [

11]. These unpredictable program behaviors might frustrate applicants. From our data showing a decrease in average IIs, we suspect that programs did not increase the number of IIs proportionately in response to an increase in applications. Instead, the minority of top applicants might have crowded out the majority’s ability to obtain IIs. According to the National Resident Matching Program (NRMP), 18 interviews correspond to a 99% match success rate. 33% of US applicants in our study received more than 18 IIs, an excess of 1670 interviews beyond assuring a 99% match [

8,

12].

In addition to the increased volume of applications, we have measured other changes in the application process. The USMLE1 score changed to pass-fail for the 2024 application year. Also, many schools changed their clerkship grades to pass-fail during the pandemic, and some did not revert to traditional grades educational systems normalized. In 2023 and 2024, there was the largest jump in the number of applications per candidate in the last five years, as fewer differentiating factors might have encouraged students who would have felt less competitive by having to report poor scores. There were also more applicants to surgery residency programs, possibly for the same reasons.

This change in applicant and program behavior might have created unintended consequences that have harmed students applying to general surgery. Students have fewer opportunities, with the average number of IIs for US students dropping from 17.4 to 12.7, a 31% decline. [

12,

13]. According to the NMRP, 12 contiguous ranks correlate with a 90% probability of matching. One-half of USMD applicants did not receive 12 IIs to then rank, thus limiting choice and opportunity. Whether harm will occur to programs is more challenging to measure except in the most extreme where a program does not fill all its positions.

According to the NRMP, the number of US senior applicants submitting a rank order list increased from 2020-2024 by 36%, while positions grew by only 16% [

2]. Even the 3100 applicants in 2023 listed by the NRMP are a subset of those trying to apply for surgical residency programs. The electronic residency application service (ERAS®) reports that in 2023, 5167 applications were submitted (ERAS® does not provide any additional data such as student type) [

14]. Thus, 40% of all applicants did not submit a rank list; presumably, most of those did not receive any interviews.

This is one of the first studies to measure the effects of signaling on the general surgery interview process, and it has early signs of some success. During this period, applicants were given five tokens to “spend” on programs highlighting their interests. Signaling programs seemed to improve the yield for an interview substantially, with a mean yield of 21% for all applications and 68% for signaled programs.

Historically, IMGs had a slim chance of obtaining interviews, especially in highly competitive fields, including general surgery. We documented these students' huge barriers and suspect an IMG's chances of matching could be even more difficult than we described. Our database does not reflect the entire body of international applications. IMGs were underrepresented in the database as they only represented 14% of the candidates. Still, according to the published NRMP data in 2023, they represented more than 35%. That percentage might be a huge underrepresentation as it includes only those who submitted a rank list and thus had at least one II. Also, we could not sub-categorize IMGs by residency status. There likely are differences between US IMGs, non-US IMGs, and IMGs in preliminary US programs.

Our study does have noteworthy limitations. We used a residency match resource with non-verifiable and incomplete metrics. There might also be differences between those using the resource versus the total applicant pool. However, this database is unique and adds to the story of the match process that was otherwise inaccessible: access to longitudinal data, up-to-date data, metrics regarding signaling, type of grading systems, the number of applications and IIs, and academic rank.

The goal of the match system, however, is not to collect IIs but to secure a position to optimize career aspirations. Our study did not directly evaluate the match's success, as the resource database we used had limitations. Namely, applicants seemed to stop updating the database once match results were published – likely because the public database had much less utility after the match. As the number of IIs correlates strongly with the likelihood of matching into a program, we believe using IIs was an excellent proxy [

12,

15]. In fact, using IIs gave us more powerful statistical insight into predictors by providing a wider range of assessing an application's strength instead of a binary variable (i.e., matched vs unmatched).

Not all applicants applied to the same types of programs as applicants likely self-selected themselves to programs that suited their goals. However, considerable overlap of applied programs may exist with candidates applying to so many programs. Similarly, programs are not a monolithic group. Different programs have varying interests and selection processes. For instance, while publications were not predictive of the overall number of invitations, they might be more heavily relied upon particular programs whose mission is to train surgeon-scientists. Heterogeneity in the program’s and applicant’s behavior decreased the predictive power of our modeling.

Our advice to students attempting to match into general surgery includes focusing on obtaining USMLE2 scores – noting inflection points at 245 and again at 265. Using the residency application to its fullest to stand out from the thousands of other candidates is vital – especially focusing on why specific programs are of interest. Match your career aspirations with the residency training program. IMGs should be aware of the substantial barriers to training in the US. Use signal tokens wisely and apply widely. We recommend that students pursue leadership, research, community engagement, or other extracurricular activities consistent with their career aspirations, even though we could not measure the benefit (likely as all students listed a considerable volume of experiences). Quality of experience might stand out more than quantity. Ultimately, the selection process is determined by unique individuals with different biases and philosophies, not computers. As we have quantified, considerable uncertainty exists in the match (R squared=0.31), and candidates should expect the match process to produce some unexpected results.

Ostensibly, the purpose of the match is to optimize the students' needs over the training programs'. To that end, we have recommendations for improving the match process.

Tokens could be better used for accepting interviews rather than for applying. We suggest extending the number of “interview” tokens to 18-20. Programs might be forced to have more robust wait lists. We estimate this alone would reapportion 20 percent of IIs and maximize opportunities.

Candidates should be allowed to detail a limited number of narrow geographic requirements that would be viewable only by programs in those locations.

Medical schools should provide standardized and meaningful measures of academic performance. The lack of differentiation between candidates creates randomness in interview selection. The de-emphasis on grades to decrease student stress in some schools does a disservice to all those interested in competitive residency programs. For instance, we found that schools that were pass-fail for clerkships hindered the chances for an II.

DOs do not yet approach USMDs in match rate (72% vs. 56%) but have a similar number of interviews (13 vs. 11.7), even controlling for other factors. This suggests biases exist in the final program ranking that should be monitored closely.

While in-person interviews might return the system to “normal,” the typical financially strained applicant with medical school-related debt is disadvantaged. In all other post-graduate fields, a free market exists where the employer often pays for an interview. However, the match obligates the resident to train for five or more years in a program or city they might have never visited, and perhaps organized hospital fairs before application season might achieve some balance.

Programs should transparently declare their mission and list characteristics of their previously matched residents (application metrics and ultimate career paths). Thus, applicants can consider their career objectives when applying to programs. Also, citations, probations, and board pass rates should all be in one easy-to-view location.

Conclusion

This study documents a substantial increase in the number of applications per candidate to general surgery residency training programs over the last few years, without a proportionate increase in positions or, seemingly, in interview invitations. Coupled with fewer distinguishing characteristics, selecting candidates for an interview invitation and ranking them has become more difficult for programs to apportion equitably. While we cannot offer surgical training for all who want to become surgeons, we should strive towards a fair process that maximizes student opportunities and ensures we meet our social obligations as educators.

References

- Rasic, G.; Collado, L.; Kobzeva-Herzog, A.; Dechert, T. Standing in Unity Amidst Change: A Group Mentorship Model that Addresses the Logistical and Emotional Needs of Applicants for Surgical Residency. J. Surg. Educ. 2023, 81, 161–166. [CrossRef]

- NRMP. NRMP® releases the 2023 Main Residency Match Results and Data report, the most trusted data resource for the Main Residency Match® | NRMP [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 30]. Available from: https://www.nrmp.org/about/news/2023/05/nrmp-releases-the-2023-main-residency-match-results-and-data-report-the-most-trusted-data-resource-for-the-main-residency-match/.

- Wames, W.M.; Welter, M.; Folkert, K.; Elian, A.; Timmons, J.; Sawyer, R.; Shebrain, S. Applicants Performance in Interview for a General Surgery Residency Pre- and During Coronavirus Disease-19 Pandemic. J. Surg. Res. 2023, 293, 341–346. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Denham, Z.; Ungerman, E.A.; Stollings, L.; McCausland, J.B.; Hamilton, M.F.; Gonzaga, A.M.; Bump, G.M.; Metro, D.G.; Adams, P.S. Do Lower Costs for Applicants Come at the Expense of Program Perception? A Cross-Sectional Survey Study of Virtual Residency Interviews. J. Grad. Med Educ. 2022, 14, 666–673. [CrossRef]

- USMLE. USMLE Step 1 Transition to Pass/Fail Only Score Reporting | USMLE [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2023 Dec 30]. Available from: https://www.usmle.org/usmle-step-1-transition-passfail-only-score-reporting.

- Guiot, H.M.; Franqui-Rivera, H. Predicting performance on the United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 and Step 2 Clinical Knowledge using results from previous examinations. Adv. Med Educ. Pr. 2018, 9, 943–949. [CrossRef]

- NRMP. Characteristics of U.S. MD Seniors Who Matched to Their Preferred Specialty in the 2022 Main Residency Match. 2022 [cited 2023 Dec 30]; Available from: https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Charting-Outcomes-MD-Seniors-2022_Final.pdf.

- Residency Application Data. 2024 General Surgery Residency Application Spreadsheet [Internet]. Public Data for General Residency Applications. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 30]. Available from: https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1MYqD0QtWvg3a65k8O6Qgm3VCDWTFCvfhPB33y9dxbLU/edit#gid=808967751.

- Labiner, H.E.; Anderson, C.E.; Patel, N.M. Virtual Recruitment in Surgical Residency Programs. Curr. Surg. Rep. 2021, 9, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, K.; Walling, A.M.C.; Johnson, M.; Curran, M.; Irwin, G.M.; Meyer, M.; Unruh, G. The Impact of Virtual Interviewing During the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Residency Application Process: One Institution’s Experience. Acad. Med. 2022, 97, 1546–1553. [CrossRef]

- Iwai, Y.; Lenze, N.R.; Becnel, C.M.; Mihalic, A.P.; Stitzenberg, K.B. Evaluation of Predictors for Successful Residency Match in General Surgery. J. Surg. Educ. 2021, 79, 579–586. [CrossRef]

- NRMP Residency Data & Reports. 2023 Main Residency Match. National Residency Matching Program; 2023.

- APDS. APDS Task Force General Surgery Application and Interview Recommendations for 2023 - 2024 Recruitment Cycle [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://students-residents.aamc.org/media/13466/download.

- ERAS. ERAS Statisitics. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/data/eras-statistics-data. Accessed Jan 11 2024.

- NRMP. Charting OutcomesTM: Characteristics of Applicants who Match to Their Preferred Specialty | NRMP [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Dec 30]. Available from: https://www.nrmp.org/match-data-analytics/interactive-tools/charting-outcomes/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).