1. Introduction

In the era of knowledge economy, innovation has become the main driving force for the development of every country and region. Innovation is becoming increasingly important not only to create new market opportunities, but also to promote economic transformation and upgrading, and improve a country international competitiveness. Zoltaszek and Olejnik argue that the literature on regional innovation research has evolved significantly over the past few decades [

1],including regional innovation system [

2,

3], learning region [

4,

5], innovation milieu [

6,

7], regional innovation network [

8], regional innovation patterns [

9,

10] and social filter theory [

11,

12,

13,

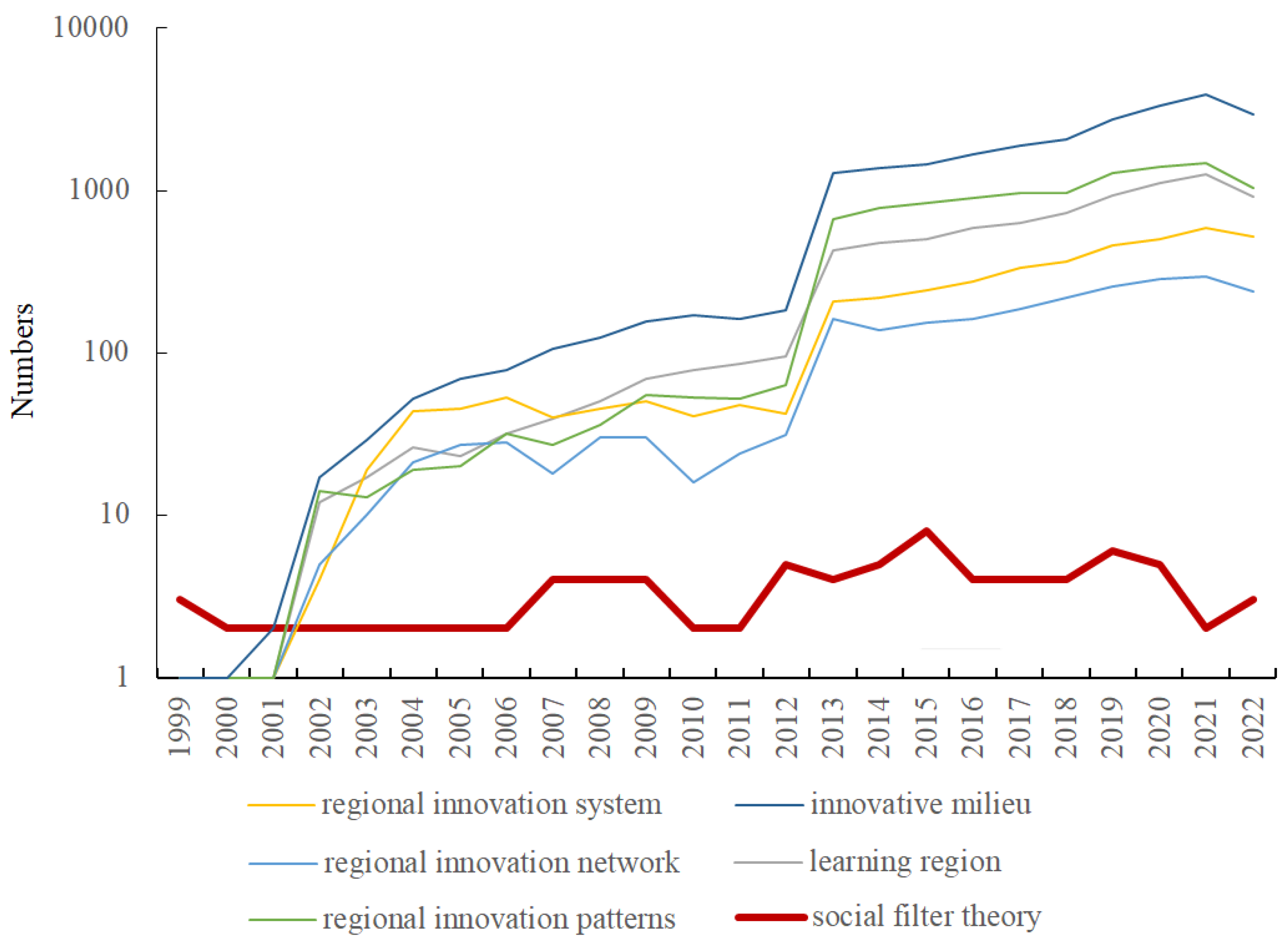

14]. We searched for relevant keywords through Web of Science to summarize the frequency of these theories (

Figure 1). It’s worth noting that the articles of social filter theory were relatively few and the research progress was relatively slow compared with the vigorous development of other innovation theories from 1999 to 2022. Social filter theory didn’t attract widespread attention from scholars. However, social filter condition is the prerequisites for the successful development of all innovation activities, which not only affect the generation of regional innovation, but also determine the efficiency of innovation transformation [

15,

16]. As yet, there is still a lack of unified understanding of the conceptual connotation and extension of social filter, and we find expressions such as “social filter” [

17], “cultural filter device” [

18] and “institution playing the role of ‘social filter’ ” [

19,

20,

21] in different literatures.

In the above statement, social structure, culture or institution are only a certain dimension or domain of social filter. The synergy of these elements is an important guarantee for building a mature innovation system. Scholars such as Rodríguez-Pose argue that different regions vary greatly in transforming their R&D efforts into innovation and economic growth, and the reason for this is that each region has different social filters. Social filter theory emphasizes that regional socio-economic conditions constitute social filters, which may have a heterogeneous impact on innovation and the ability to innovation transformation and form invisible barriers to knowledge spillover between regions, affecting the spatial diffusion of knowledge [

22]. Throughout the available literature on social filter, besides most of them just appearing in the form of review citations, Rodríguez-Pose and his collaborators have conducted some empirical studies using social filter as an alternative tool for regional innovation systems, mainly focusing on developed countries and regions, such as European Union, United States, Italy [

19,

23] and emerging countries, such as China, India, Russia, Mexico [

22,

24,

25].

In general, social filter theory has a strong explanatory ability for the formation of innovation geography in various countries and regions, as well as the law of the direction and extent of knowledge space diffusion. It is a pity that over the past 20 years, social filter theory has been as silent as a sleeping beauty and hasn’t been fully developed. Nowadays, innovation is so valued by society, the social filter theory will surely shine with new brilliance, usher in the spring of academic research, and put its stamp on the regional innovation theory.

The article is structured as follows.

Section 2 summarizes the concept of social filter, tracing the relevant literature and identifying the connotation of social filter. In section 3, we clarify the measurement indicators and methods of social filter. In section 4, we illustrate the mechanisms of social filter affecting regional innovation and innovation transformation, highlighting the role of social filter within and between regions. In section 5, we compare relative empirical researches based on social filter. Our discussion in section 6 and some perspectives carry broader future development direction about social filter theory.

2. What’s the Social Filter?

Since Schumpeter proposed the theory of innovation, it has become a widely accepted consensus that technology serves as the engine of economic growth. However, it’s not always smooth process from R&D to innovation and then to economic growth. Some regions experience positive effects on economic performance from their R&D investment and innovation capabilities, while others fail to establish a connection between innovation and growth. Furtherly, the phenomenon of R&D investment not yielding expected results is due to the filter effect of local social conditions on innovation and knowledge spillover (Rodríguez-Pose ,1999).

Based on this, Rodríguez-Pose (1999), following definition of relationship space [

26], believes that each region has a unique social filter consisting of innovative and conservative elements that favour or deter the development of successful regional innovation systems. If the innovative elements of a region’s social filter dominates, its ability to learn technology and obtain returns from R&D investment will be stronger. Conversely, if the conservative elements dominates, its ability to obtain returns from R&D will be weaker [

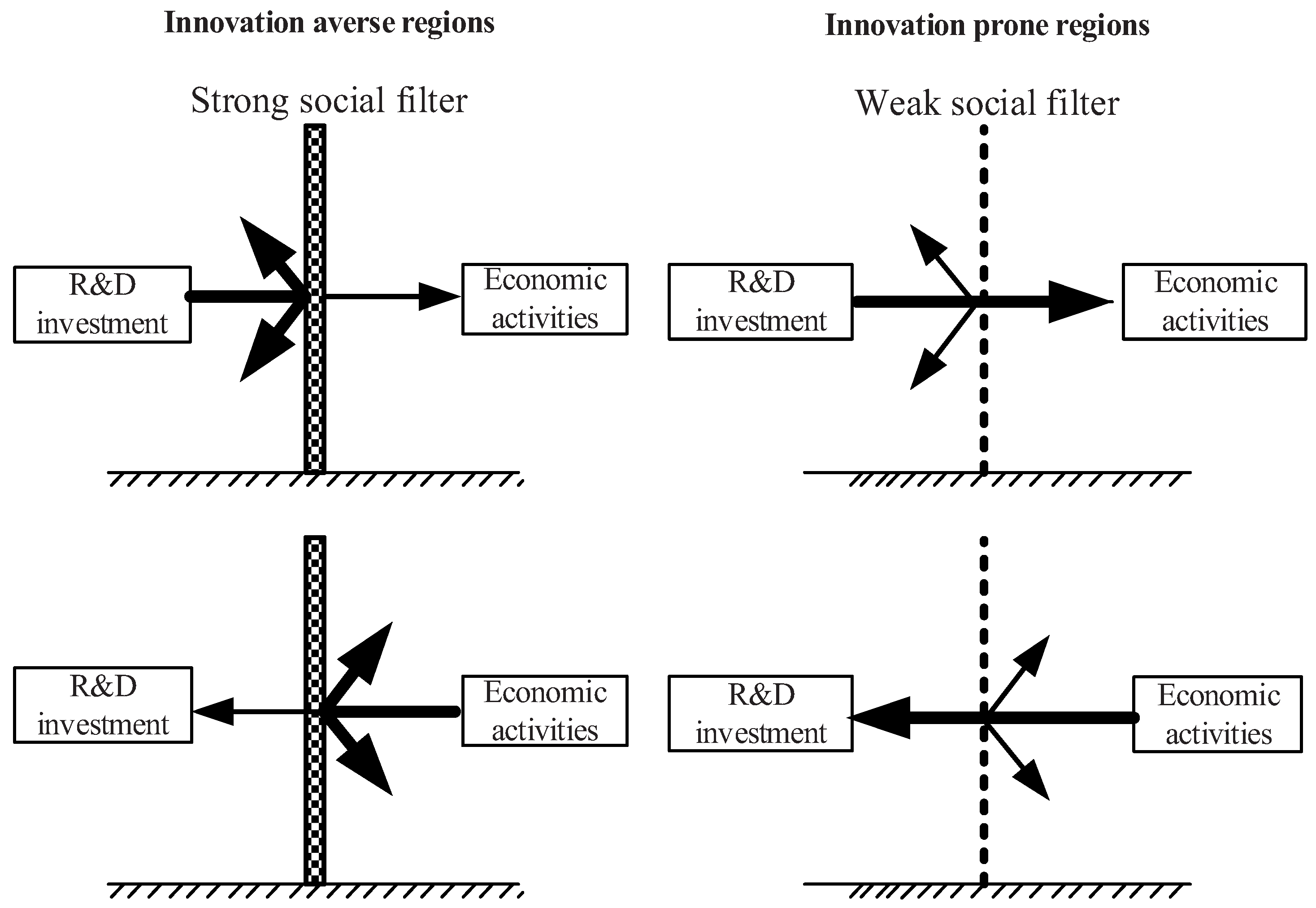

27].According to the social filter condition, regions can be divided into two types: innovation prone region

1 and innovation averse region (

Figure 2). Regions with weak social filter, such as innovation prone regions, have a adquate permeability to innovation and change, are more open to external innovation, and actively learn from advanced regions. These regions can smoothly transition from product innovation technology to economic activities and efficiently transform their innovation inputs into outputs. On the other hand, social filters of regions with innovation averse characteristics are almost impervious. Companies and even the entire society in these countries and regions haven't the ability to transform technological innovation into higher value-added economic activities. It can be seen that social filter produces impedance and permeation effects between R&D investment and economic activity.The social filter is composed of regional socio-economic and institutional conditions, as well as intangible capital such as human and social capital, which influence knowledge generation, diffusion, and ultimately affect innovation performance [

28,

29,

30].

The coexistence of innovation prone regions and innovation averse regions suggests that not all regions possess the same capacity for innovation and transforming it into economic growth [

31]. In some situations, some regions experience multiple economic growth as a result of their R&D investment, while others derive less benefit from their investment in spite of the same R&D investment. This is because social filters create impedance and penetration effects between R&D investment and economic activities in each region. Rodríguez-Pose (1999) provided examples of traditional industrial decay and depressed regions, as well as peripheral regions, exhibiting characteristics of an innovation averse society. This is due to the rigid social structures established in industrial decline regions during the era of mass production, which have become significant obstacles for these regions to adapt rapidly to external technological changes.

On the one hand, a considerable portion of the skilled and unskilled blue-collar workers, who dominated the era of mass production, were trained according to Taylor’s principles, making it difficult to redeploy them and adapt to new technological transformations. On the other hand, a rigid labor market has witnessed troubles of finding suitable jobs among the younger and talented generation. The lower social mobility and limited economic activities in certain social sectors further contribute to the transformation of these regions into innovation averse societies. Similarly, some peripheral regions struggle with insufficient innovation dynamics, making it difficult to achieve growth. Additionally, these peripheral regions also face challenges related to weak economic organization and lack of entrepreneurial spirit.

In this regard, the concept of social filter provides a more convincing explanation for the diverse regional innovation patterns observed in different countries and regions. Social filter is essentially a filter system composed of local social conditions, and due to the incoordination of various factors, R&D activities cannot fully penetrate into the production system. Social filter conditions exert a strong influence on innovation performance. It’s not one single social economic factor in isolation that matters for innovation. Instead, it’s the combination of a set of local feartures — human capital, young people, social capital and so on — that capture their synergies and interations. In extreme cases, it’s challenging to expect innovation to emerge in societies characterized by fragile trust, human capital deficiencies, and inadequate protection of property rights. Only the accumulation of human capital is combined with a youthful population structure and a vibrant labor market, can a virtuous cycle of human capital accumulation be formed [

32].

3. Indicators and Measurement Methods of Social Filter

Social filter is the result of a multifactor composite representation, and its complexity and intertwined characteristics make it challenging to describe qualitatively and quantitatively, which hampers comparative analysis between regions [

33]. In order to measure social filter, scholars have made continuous explorations on how to specifically characterize indicators of social filter, leading to the development of valuable conceptual frameworks and measurement approaches [

15,

22].

3.1. Indicators for Measuring Social Filter

Currently, there is still debate regarding the measurement indicators of social filter among domestic and international scholars. In the early stages of social filter researches, social filter could be measure by indicators composed of demographic structure, the proportion of agricultural labor, long-term unemployment rate, and education level, serving as the prototype indicators of social filter [

17]. Moreover, socioeconomic indicators should reveal a region’s skill levels, labor market conditions, and economic structure [

34]. Among them, human capital is a core indicator of social filter [

33]. This is because human capital, as reflected by education levels, can represent a region’s capacity for learning and absorption, and many observable and unobservable factors (e.g. talent mobility, local education quality, and the social returns of education) can indirectly impact innovation through the accumulation of human capital. In particular, the varibles that seem to be more relevant for shaping the social filter are those relative to three aspects such as educational attainment, productive employment of human resources, and demographic structure [

35]. Specifically, compared to other sectors, productive employment in the agricultural sector tends to have lower productivity and represents hidden unemployment. Long-term unemployment rate is an important indicator of labor market rigidity, reflecting the plight of regional workers who lack the necessary skills for productive work. Young people are the driving force behind regional innovation and social change, and regions with active youth populations tend to generate more innovation [

23]. Ultimately, the above aspects were synthesized a preliminary framework of social filter indicators, including local market rigidity, demographic structure, education, technology and human capital, as well as scientific infrastructure [

36]. These socioeconomic conditions can be both catalysts and filters for innovation [

37].

In addition to economic structural elements, scholars have also incorporated cultural and institutional factors into the system of social filter indicators. For example, Entrepreneurial culture should be factored into the social filter [

38]. Social exclusion and institutional efficiency should also be included besides the core indicator of human capital when the primary concern is the institutional level of society [

39]. For one thing, regional innovation depends on the sharing and exchange of information or knowledge among individuals, adverse social institutional conditions can hinder the local economic system absorption of knowledge; for another, regional innovation is also constrained by social capital and institutions, impeding economic growth [

25]. Empirical researches demonstrated that institutional quality plays a role in social filter, affecting a region ability to transform innovation into economic growth [

40]. Moreover, institutions profoundly shape the innovation environment of firms by facilitating or impeding learning and knowledge spillovers, thereby influencing firms’ innovation performance [

19]. Others further refine the institutional indicators, including urbanization rate, social capital, privatization, financial development index, and property rights development index. Apart from that the agglomeration effect resulting from urbanization can promote innovation, social capital facilitates innovation by disseminating knowledge and valuable information, and institutional factors such as contract law, property rights, or privatization play a crucial role in innovation [

41].

Table 1.

Social filter indicator systems in relevant studies.

Table 1.

Social filter indicator systems in relevant studies.

| Author |

Social Filter Proxy |

Secondary Indicator |

Tertiary Indicator |

| Rodríguez-Pose(1999) |

Social conditions |

Demographic structure |

No measurement |

| Agricultural labor |

| Unemployment rate |

| Education level |

| Bilbao-Osorio and Rodríguez-Pose(2004) |

Social economic factors |

Level of skill |

Percentage of adult population (25-59 years old) |

| Labor market situation |

Employment rate |

| Economic structure |

Percentage of employees in high-tech manufacturing and service industries |

| Crescenzi(2005) |

Human capital |

Educational attainment |

Percentage of educated population |

| Crescenzi et al., (2007);Rodríguez-Pose and Crescenzi(2008);Crescenzi et al., (2012);Rodríguez-Pose and Peralta(2015) |

Social economic conditions |

Educational achievements |

Life-long learning |

| Labour force with higher education |

| Productive employment of human resources |

Percentage of labour force employed in agriculture |

| Long-term unemployment rate |

| Demographic structure |

Percentage of youth population (15-24 years old) |

| Rodríguez-Pose and Comptour(2012) |

Social economic conditions |

Local market rigidities |

Long-term unemployment rate |

| Agriculture employment |

| Corporate tax rate |

| Demographic aspects |

Percentage of youth population (15-24 years old) |

| Education, skill, and human capital |

Total population education |

| Life-long learning |

| Scientific base of the region |

Human resources in science and technology |

| D'Agostino and Scarlato(2015) |

Social Institutional conditions |

Social exclusion |

Long-term unemployment rate |

| Juvenile unemployment rate |

| Families poverty index |

| Education level |

High school dropout rate at the end of the first year |

| Secondary education rate |

| Percentage of employed adults |

| Institutional efficiency |

Municipal waste-sorting services |

| Perception of the risk of crime |

| Rodríguez-Pose and Zhang (2019) |

Social filter |

Demographic structure |

Percentage of youth population (15-24 years old) |

| Sectoral composition |

Percentage of agricultural employment |

| Use of human resourse |

The employment rate |

| Ownership structure |

The share of employment in private firms |

| Kaneva and Untura(2019) |

Social-economic filter |

Availability of a skilled labor force |

The share of university graduate |

| The share of labour with tertiary education |

| Demographic structure |

Labour aged 15-30 employed |

| Industrial structure |

The share of labour employed in agriculture |

| Xiong et al., (2020) |

Social filter conditions |

Urbanization rate |

Proportion of residents living in cities |

| Social capital |

Number of social organizations per ten thousand people |

| |

|

Privatization |

Percentage of private fixed investment |

| Financial development index |

China’s Marketization Index Report 2011 |

| Property rights development index |

China’s Marketization Index Report 2011 |

3.2. Methods of Measuring Social Filter

From the composition of social filter indicators proposed by the aforementioned scholars, social filter is a composite of a unique set of social and structural elements, some of which promote regional economic activity while others hinder it [

19]. Moreover, there is correlation and even information overlap among certain constituent indicators. Including all of these variables simultaneously in a regression model can lead to collinearity. Therefore, principal component analysis (PCA) is used to measure social filter by synthesizing these variables into a single indicator that can capture as much of the original indicators variation as possible. Principal component analysis provides a “joint measure” for assessing social filter in each region.

Scholars often use the first principal component as the social filter index to measure the social filter conditions across different regions. In the research conducted on EU member states, the first principal component explained 43.1% of the total variance, with an eigenvalue significantly greater than 1. The signs of the weight coefficients for the sub-variables align with expectations: the impact of the educated population, educated labor force, and participation in lifelong learning are positive, while the influence of agricultural labor and long-term unemployment is negative, and the weight for the 15-24 age group is relatively small [

35]. In research on the states of the United States, the first principal component alone is able to account for around 36 percent of total variance, and the proportion of the population aged 15-24 and the proportion of the population with a bachelor’s degree and higher had negative contributions to the comprehensive social filter index, while the proportion of the unemployment rate and agricultural employment population had positive contributions [

32], this is contrary to the findings of EU member states [

35]. In the comparative research of China and India [

24], the first principal component alone accounts for 45% and 36% of the total variance of the original variables considered for China and India respectively, and the weight coefficients of the subvariables were completely opposite. The influence of the proportion of young people and the proportion of educated population is negative in China and positive in India; The impact of unemployment and the proportion of people employed in primary industries is negative in India and positive in China. It is not difficult to find that the result of China is the same as the measurement result of Rodríguez-Pose (2012) for American states, while the result of India is consistent with the results of EU member states.

In the research on Mexican states, the first principal component used to measure social filter explained 54% of the total variance, and each sub-variable made the expected positive or negative contribution to the composite variable of the social filter index. Educational and skill variables, as well as the percentage of young population, were positively correlated with the composite social filter index, while the percentage of agricultural employment showed a negative correlation [

22]. Additionally, on Chinese prefecture-level cities, the first principal component explained 37.8% of the total variance, with the weight for the proportion of youth population and private sector employees being negative [

42]. This contrasts with the contribution of the youth population to the social filter index as measured in the EU and Mexico. The results of other scholars aren’t listed here.

It can be seen that although the use of principal component analysis to measure social filter and the use of the first principal component score as a social filter index have been widely accepted and used by scholars, the measurement results of the social filter index aren’t necessarily the same due to differences in research subjects and constituent indicators. It is particularly noteworthy that there is a lack of more scientific arguments and explanations for the selection of constituent indicators for social filter. Importantly, the generalization and arbitrariness in indicator selection need to be addressed. Hence, it’s urgent to establish scientific evaluation criteria and strive for a unified understanding. It is worth mentioning that in statistics, in addition to principal component analysis, cluster analysis, analytic hierarchy process, and self-organizing mapping are popular methods for condensing high-dimensional data into low-dimensional data.

4. Mechanisms of Social Filter Affecting Regional Innovation and Innovation Transformation

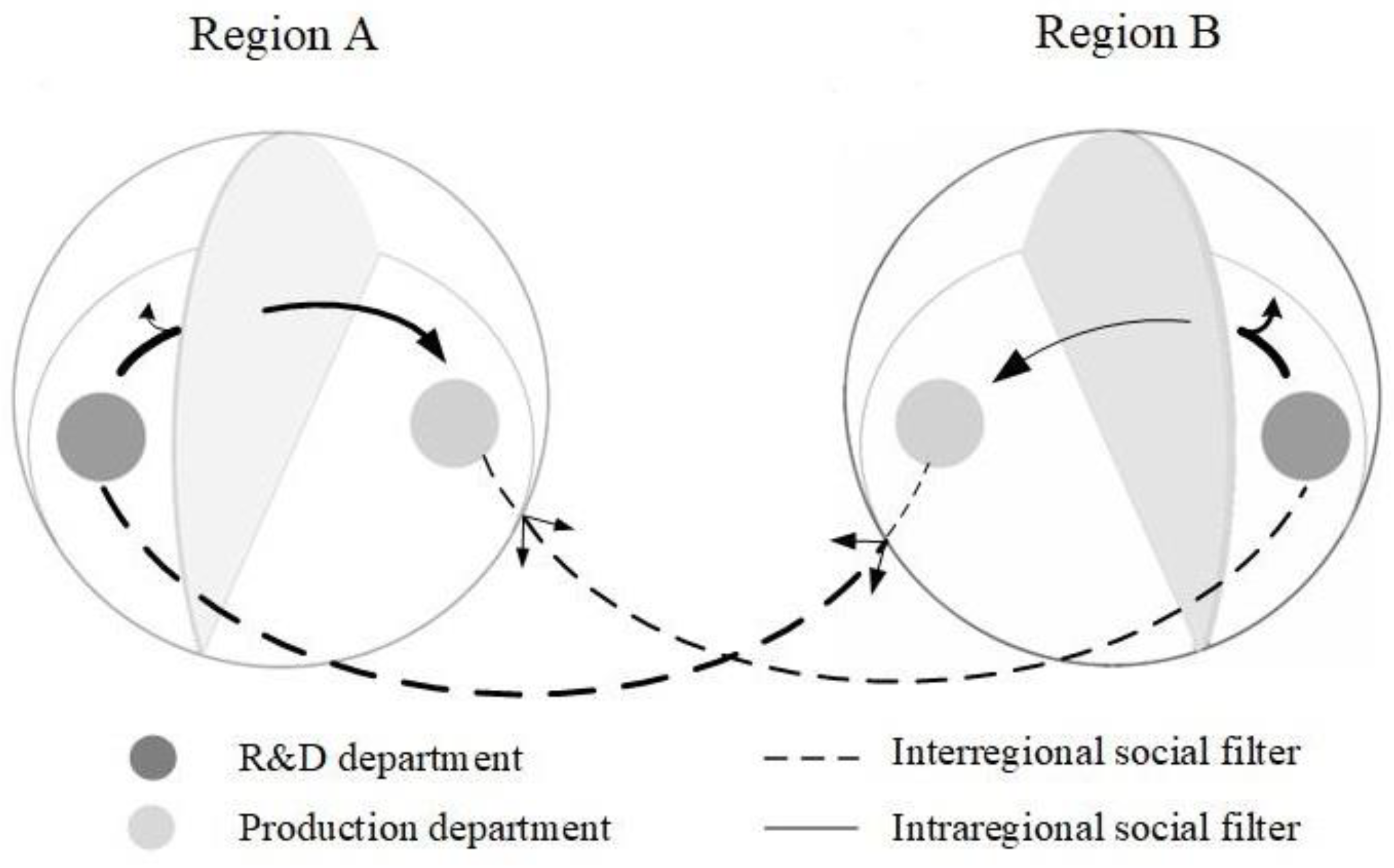

For regional innovation and innovation transformation, the mechanism of social filter can be understood as a process of digestion and absorption, where the constituent elements of social filter form a filter organization. In terms of filter way, social filter manifests itself in two ways: internal filter and external filter, corresponding to intra-regional R&D and interregional knowledge spillovers, respectively. In terms of filter channels, social filter influences the generation, dissemination, absorption, and utilization of knowledge, ultimately impacting the efficiency of regional innovation and innovation transformation (Ren, 2021). In order to comprehensively summarize and reveal the mechanisms through which social filter affects regional innovation and innovation transformation, this research presents a conceptual diagram illustrating the interplay between social filter and knowledge spillovers in two regions (

Figure 3). For instance, assuming an economy with two regions, A and B, where the region A’s social filter condition is more adequate than region B. The darker one is knowledge production department referring to universities and research institutions, while the lighter one is innovation transformation sector referring to the production department. In this way, the baffle inside the ball in

Figure 3 is similar to the social filter generated by the region itself on knowledge transformation in

Figure 2, and the surface of the ball can describe the social filter generated by the two regions on knowledge spillover from both sides. As can be seen from the

Figure 3, region B has a stronger social filter effect on both regional knowledge transformation and inter-regional knowledge spillover.It’s production department can absorb knowledge from its own and its neighbor’s investment due to an adequate social filter condition in region A. Due to deficient social filter condition of region B, however, whose production department can’t successfully make full use of interregional and intraregional knowledge spillover.

4.1. Heterogeneous R&D Activities and Innovation Transformation

The R&D process can be divided into two stages: knowledge creation and innovation transformation [

43]. Knowledge possesses the characteristics of a public good, with both non-rivalrous and partially excludable attributes [

44]. Therefore, the location of innovation transformation can be completely different from the place of innovation [

45]. Knowledge generated within a region and knowledge generated outside the region are both important sources of regional growth [

46]. In fact, regions can choose to simultaneously transform local innovations and innovations from other regions into local production activities, thereby promoting local economic growth [

47]. However, other factors should also be taken into account, as different regions demonstrate varying capacities in absorbing and transforming innovation into economic growth.

R&D activities in different regions aren’t homogeneous and exhibit various types due to differences in product characteristics and ownership forms, resulting in disparities in productivity [

48]. R&D investments in the private sector are more directly linked to new products and services. In contrast, research conducted by the public sector and higher education institutions often leans towards basic research, posing challenges in the transformation of their inventions and patents [

34]. In brief, the phenomenon that new knowledge and creative ideas struggle to be effectively translated into products or processes innovation as the “knowledge paradox” [

49].

In addition, different types of R&D activities lead to varying economic performances, and the selection of regional innovation patterns should be aligned with the region’s development stage and conditions. For example, the regions is in a relatively low stage of development, even if they forcefully pursue independent innovation and increase R&D investments, they may lack the talent and market foundation necessary to promote advanced technologies [

50]. Thus, the choice of innovation patterns should match a country or region’s factor endowments, institutional environment, and technological ecosystem, as only a proper match can effectively achieve sustained high-level technological progress. Bilbao-Osorio and Rodríguez-Pose (2004) also highlight the numerous obstacles faced by peripheral regions in terms of R&D investments. Firstly, financially constrained peripheral regions struggle to allocate sufficient funding to reach the critical mass for innovation due to the high costs of R&D activities. Secondly, these regions often lack a well-established innovation system involving government, industry, university, and research institution, and they have limited capacity to establish technological linkages with other regions. Lastly, peripheral regions often lack a clear strategy for scientific and technological development. In contrast to more developed regions, Oughton et al. (2002) further emphasize that peripheral regions have a higher demand for innovation inputs but relatively low capacity to absorb public funds for promoting and investing in innovation-related activities.

However, it is worth noting that the challenges faced by peripheral regions in achieving innovation through independent R&D investments may extend beyond these bottlenecks. It may seem more reasonable for underdeveloped regions to achieve development by free-ride of other innovation core regions. In reality, there is no single standard for how different regions should choose their preferred innovation patterns, and further exploration is needed.

4.2. Social Filter and Regional Internal R&D Activities

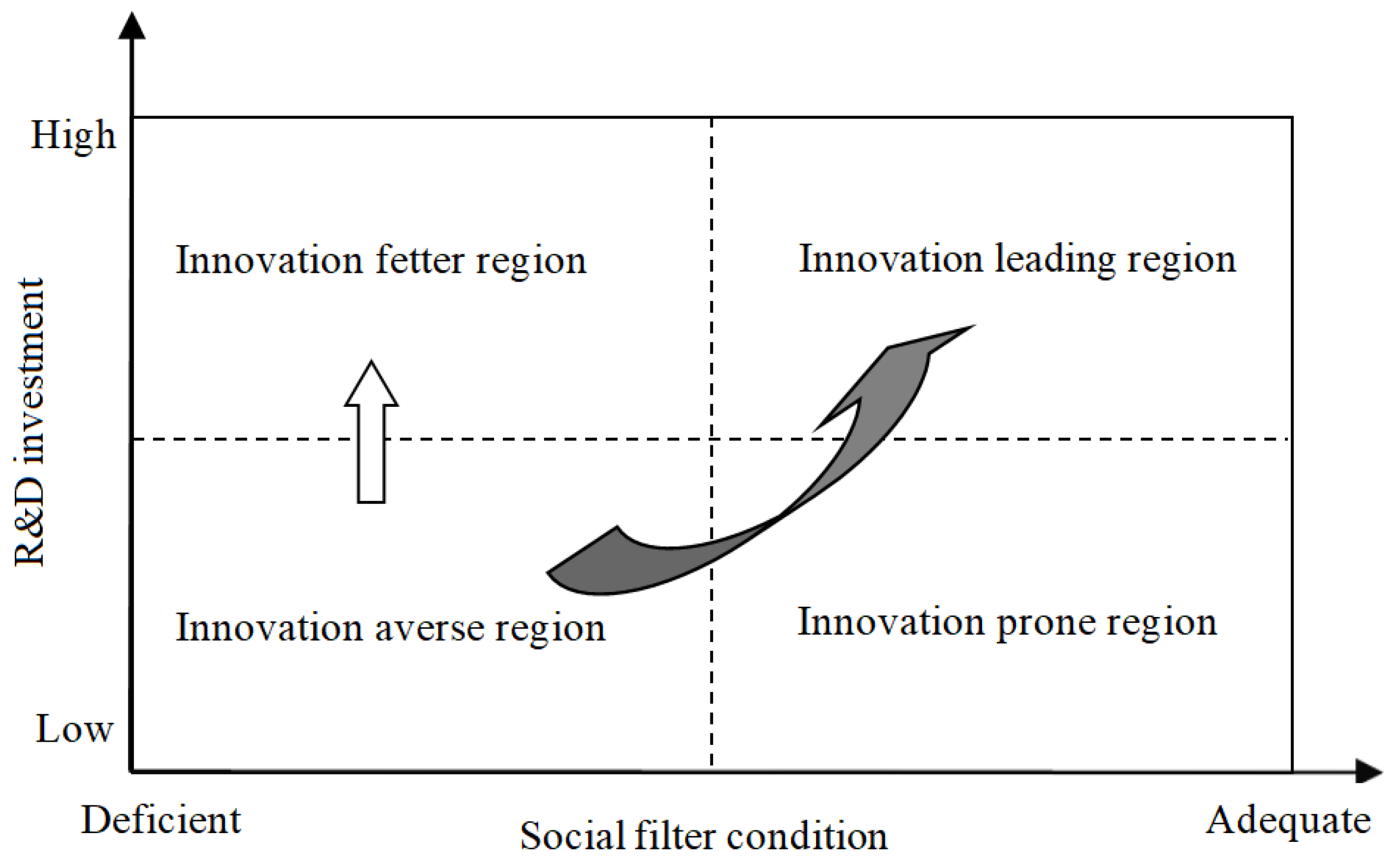

R&D activities are the main form of regional innovation, and the social filter conditions vary across regions. Social filter, composed of specific social, political, and economic features, influences the ability to transform R&D investments into innovation and economic growth. According to Rodríguez-Poses (1999) description of social filter, stronger social filter indicates worse local social filter conditions. The matching between regional R&D activities and social filter conditions may result in different economic performances.

Figure 4 provides a visual representation of the potential combinations between regional R&D investments and social filter conditions, categorizing regions into four types: innovation averse regions, innovation fetter regions, innovation prone regions, and innovation leading regions.

As shown in

Figure 4, the innovation leading regions are located in the upper right corner. These regions have a strong permeability of social filter on R&D activities, and high levels of R&D investment can effectively drive economic growth. Innovation leading regions are typically the innovation centers and growth poles of a country or region, playing a leading and demonstrative role in economic and social development. In contrast, innovation averse regions are located in the lower left corner of the figure. These regions have insufficient R&D investment and worse social filter. They often have low organizational thickness, lack innovation spirit, and exhibit inertia and disregard for innovation. They are usually lagging and peripheral regions. In addition to these two opposite situations, two intermediate scenarios may also exist. The innovation prone regions, located in the lower right corner of the figure, have adequate social filter conditions but relatively low levels of R&D investment. These regions can achieve innovative development more easily by encouraging indigenous innovation efforts or absorbing knowledge spillovers from other regions, accumulating capital for R&D investment, and surpassing the threshold for R&D investment. Conversely, the innovation fetter regions in the upper left corner are less optimistic. Due to deficent social filter conditions, blindly encouraging R&D investment poses risks similar to “building a cathedral in the desert” [

51]. Hence, the innovation transformation path indicated by the curved black arrows in the figure represents a more objective and reasonable choice.

Figure 4.

R&D investment and social filter.

Note: Modified based on the literature [

52]. The arrows in the diagram represent the transition from innovation averse regions to innovation leading regions, characterized by increased R&D investment and improve social filter condition.

Figure 4.

R&D investment and social filter.

Note: Modified based on the literature [

52]. The arrows in the diagram represent the transition from innovation averse regions to innovation leading regions, characterized by increased R&D investment and improve social filter condition.

It is evident that the economic performance potential of innovation activities in a region can only be realized when the region has adequate social filter conditions [

53]. Specifically, the impact of these conditions on regional innovation can be explain from three main domains: educational achievements, productive employment of human resources, and demographic structure. professionals and skilled labor are important forces for ensuring innovative mechanisms, and R&D becomes profitable when human capital reaches a certain threshold level. Employment rate is an important factor influencing the innovation process because young people possess stronger learning and adaptability skills, as well as more innovative spirit and risk-taking attitude. The economic structure of a region also plays a significant role in the generation and absorption of innovation. Regions dominated by agriculture are less likely to generate a large number of patents as agriculture often lacks the same level of innovativeness as other high-tech industries. Conversely, certain sub-industries within manufacturing and services sectors may be more conducive to promoting innovation [

34]. What’s more, the improvement of geographical accessibility and the accumulation of human capital can interact with regional innovation activities, facilitating the effective transformation of regional innovation into economic growth. Improvement in accessibility can influence the creation and dissemination of technology through various mechanisms. Accessibility serves as a good indicator reflecting the impact of distance on innovation because it considers not only the localized spillover represented by the frequency of interactions within a region but also the opportunities and barriers for communication between regions. Human capital accumulation, as the primary mechanism for innovation diffusion, highlights the interaction between education and innovation in the approach of the innovation system. The innovation system approach emphasizes the impact of education on the learning ability of local society [

33].

These analyses have important policy implications for innovation peripheral regions. A more effective approach to innovation-based development strategy is not only to actively encourage R&D investment but also to focus on optimizing social filter conditions [

15]. Furthermore, social filter conditions will shape the opportunity space for the future development of the region [

54]. For many regions, improving their social filter conditions is much more challenging compared to increasing R&D investment, and it can’t be expected that social filter conditions will automatically improve. Because some components of social filter adjustments cannot be achieved in the short term. In the absence of automatic adjustment mechanisms in the labor market, regional disparities in technological labor endowments may persist [

55]. At the national level, many cultural and institutional barriers are common challenges faced by regions [

23,

56], and this is one of the significant reasons why only a few regional innovation centers exist in many countries. Therefore, comprehensive improvement of social filter conditions in various regions is an important measure to enhance innovation capacity and achieve a balanced innovation development way for every country.

4.3. Social Filter and Interregional Knowledge Spillovers[23,56]

The increase in the capacity of regional knowledge pool can be achieved through its own R&D investment or by absorbing knowledge spillovers from other regions. In other words, knowledge spillovers can to some extent compensate for or even substitute for a region own R&D activities. Rodríguez-Pose (1999) expresses concerns about this free-riding behavior. He believes that even though knowledge is a pure public good and regions can access knowledge generated by other regions without friction, not every region has the necessary conditions, capabilities, and readiness to absorb knowledge. Different social filter conditions in each region create differentiated patterns of knowledge acquisition and utilization.

Although knowledge exchange can occur between regions, each region utilizes the capabilities of other regions differently. Maybe even worse, local knowledge can’t be effectively absorbed and utilized locally, but instead becomes a source of innovation for other regions. There is not always a direct connection between regional innovation and its growth. Sometimes, innovation in one region leads to increased income and employment in another region [

57]. This type of knowledge spillover phenomenon as reverse spillovers [

58]. Reverse spillovers indicates that a region innovation capacity and transformation capacity aren’t necessarily proportional. The frog jumping phenomenon of “blooming within walls but fragrance outside”is indeed present in reality. The Sicilian Paradox described serves as an example. Sicily, a lagging region in southern Italy, is not lacking in innovative companies, especially with STMicroelectronics ranking first in terms of patent authorizations among top Italian firms. However, these patents are not effectively utilized locally [

59]. When the utilization capacity outside the region is strong, but local utilization capacity is weak, a region own R&D and innovation efforts end up benefiting the development of other regions. The prerequisite socio-economic conditions for innovation should be generated locally, without relying on neighboring regions [

32]. Each region has the motivation to utilize the innovation output of others, but different social filter conditions result in varying innovation utilization capacities in each region. The social filter is the structural precondition of successful innovation development for regions. Therefore, social filter conditions not only affect knowledge production but also influence knowledge utilization [

22]. From the perspective of exchange patterns, input-output mechanisms, and intellectual exchange, regions with weak social filter conditions are more likely to benefit from external knowledge spillovers [

59]. Thus, knowledge spillovers not only are emphasized, but the externalities of social filter also need receive attention by scholars [

15].

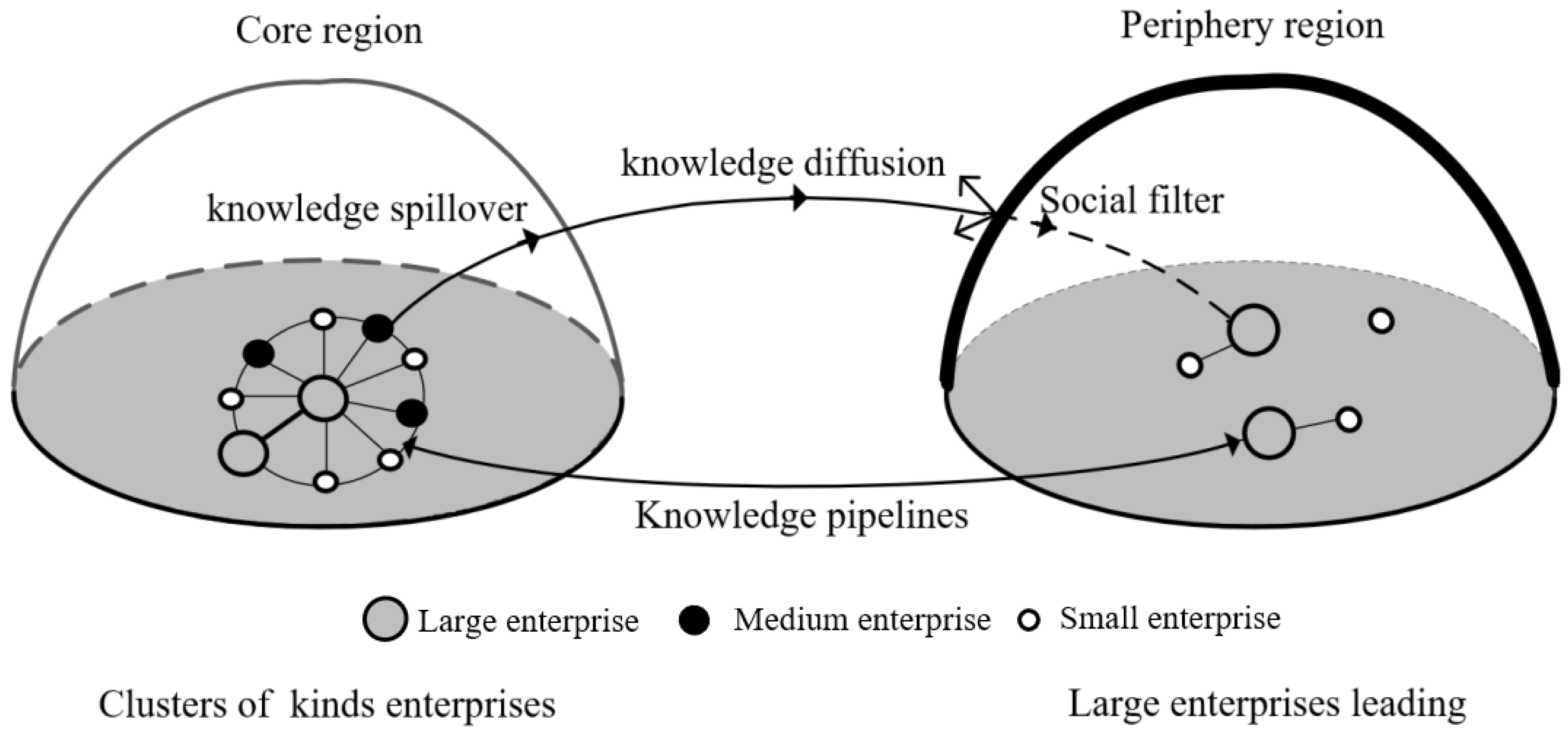

In general, regarding regional economic growth, social filters conditions play a dual role as filters for innovative activities and invisible barriers to knowledge spillovers [

60]. Regions attempting to achieve innovative development by hitchhiking face risks. If a region has poor social filter conditions, it not only fails to absorb knowledge generated by other regions but also its own knowledge diffuse and benefit other regions. The excessive concentration of knowledge or innovation in a few innovation centers leads to a widening gap between regions [

61]. Therefore, for regions to gain an advantage in achieving economic growth through innovation, they should strive to improve their social filter conditions. Nonetheless, because of path dependence, adjusting or improving social filter conditions is not easily accomplished in the short term. In addressing this issue, some scholars suggest adopting a reverse thinking approach to consider measures or channels that can penetrate, overcome, even remove the invisible barriers of social filter [

62]. When the peripheral region is usually composed of a few large enterprises, there is lack of local buzz, and at the same time, the absorption of knowledge spillovers from the core region is limited by geographical distance decay and deficient social filter conditions. In this regard, high-tech enterprises in periphery regions will deploy their R&D departments to core regions, and even in some regions, the government can purchase land in core areas, establish industrial parks, and form innovation enclaves. So as to build knowledge pipelines, avoid knowledge filter, and absorb knowledge from the core region, then flow back to the enterprises in the peripheral regions. These measures try to absorb the knowledge dividend of core regions, and gradually cultivate a local innovation system to overcome the negative impact of local unfavourable social filter (

Figure 5). Therefore regions need to have the absorptive capacity to benefit from these knowledge spillovers or from a so-called ‘social filter’ [

63].

5. Empirical Research on the Impact of Social Filter on Regional Innovation and Knowledge Spillover

Scholars have used modeling and empirical analysis to uncover how social filter affects a region’s ability to absorb innovation and transform it into economic growth. Research in this field continues to enrich and evolve. Initially, the focus of analysis was primarily on European countries, then expanded to include developed countries like the United States and Japan, and later extended to developing countries such as China, India, and Mexico. Analytical approaches employed include graphical methods, two-step analysis, and three-step progression methods. The econometric techniques have evolved from simple graphical representations to encompass simple linear regression, multiple linear and nonlinear regressions, instrumental variable methods, and dynamic GMM estimation. The analytical perspective has also shifted from initially providing a simple description of the socio-economic conditions to analyzing externality and its impact on economic growth, as well as the mechanisms of moderation and spillover effects.

5.1. The Relationship between R&D and Economic Growth as the Starting Point

Based on Schumpeter’s research on the threshold effect of R&D and the assumption of diminishing marginal returns in the neoclassical growth model, Rodríguez-Pose (2001) conducted a simple cross-sectional regression analysis of R&D investment and per capita GDP in Western European countries. The research found a significant positive correlation between R&D investment in technologically peripheral regions and economic growth, while the relationship between R&D investment and economic growth in technologically advanced regions was less apparent. However, the reliability of these results is questionable due to the presence of omitted variable bias, making it difficult to establish a direct causal relationship between R&D investment and economic growth, as other factors may be at work. Rodríguez-Pose (1999) also found that unfavorable socio-economic conditions such as low female employment rates, an aging workforce, a lack of high-skilled talent, and labor market rigidity hinder innovation in peripheral regions. It is evident that a simple one-way regression of R&D on patents or economic growth is unreliable owing to endogeneity issues, thus questioning the credibility of research conclusions in this regard.

5.2. The Analysis Models and Methods

Represented by Rodríguez-Pose and his collaborators, following scholars have expanded and enriched the models and methods that examine the impact of social filter on regional innovation and innovation transformation. Among them, the model is considered the most classic and widely used [

35,

36]. The specific equation is as follows:

According to the growth model [

64], when

is negative, it indicates conditional convergence, meaning that the economic growth of different regions tends to converge. W is the spatial weight matrix,

,

, and

represent knowledge spillovers, social filter spillovers, and economic spillovers, respectively. Among them, when the social filter has a positive spillover effect, it indicates that the behavior of free riding may be OK; When the social filter spillover effect is negative, it indicates that there is a siphon effect and polarization is easy to occur. This model combines R&D inputs, local social filter conditions, and various external spillover effects in the innovation process, which collectively contribute to the formation and evolution of innovation systems, leading to diverse regional innovation patterns across countries and regions. This model has been widely used in studies, which has improved by incorporating moderation effects and threshold effects. In terms of estimation methods, scholars have commonly employed panel fixed effects, generalized method of moments (GMM), maximum likelihood estimation (MLE), Huasman-Taylor and so on [

22,

24,

45,

65].

5.3. The Drivers of the Geography of Innovation

The spatial agglomeration of innovation activities reflects the maturity of a country innovation system, and countries with a more balanced spatial distribution of innovation activities tend to have more mature national innovation systems [

24]. So far, the literature directly relating to social filter, research on the geography of innovation has been mainly focused on the TRIAD and BRICs. America is the world’s leading innovator, the more innovative regions are located along the country’s Eastern and Western coasts, as well as in the Great Lakes region [

32]. In EU, innovation activities are highly concentrated, the 20 EU-15 regions account for about 70% of total patents. For developing and emerging countries, Brazil’s innovation hubs are mainly located in and around São Paulo, which brings together manufacturing activities, modern services, financial institutions, headquarters of large national and multinational subsidiaries, as well as excellent infrastructure and urban facilities [

66]. Likewise, the geography of innovation in Russia is spatially concentrated, eleven regions are considered strong innovators: Moscow, St. Petersburg, Republic of Tatarstan, Tomsk region, Novosibirsk region, Kaluga region, Republic of Bashkortostan, Nizhny Novgorod region, Moscow region, Samara region and Krasnoyarsk Krai [

45]. The geography of innovation in India is dominated by the high-tech hubs, such as Bangalore, Chennai, Delhi, Hyderabad, Mumbai and Pune, which consist of 60-70% patents [

24]. Moreover, the spatial concentrated of innovative activity in China is more pronounced, the three innovative regions are Guangdong, Beijing and Shanghai, which produce 60% of the country’s patents [

67]. Mexico is one of the largest emerging countries. According to IMF data, Mexico is the 11th largest economy in the world and the largest emerging country outside the BRICs. From a geographical point of view, there are also major differences in terms of the capacity of Mexican states to generate innovation. Eight Mexican states—Mexico State, the Federal District, Veracruz, Jalisco, Puebla, Guanajuato, Chiapas, and Nuevo León—concentrate 50 percent of the overall R&D expenditure in the country [

22].

In addition to the high concentration of innovation activities, there are significant differences in innovation drivers in different countries and regions (

Table 2). In the European Union, the United States, India, and Mexico, R&D investment is the primary determinant of innovation. Adequate social filter conditions enhance the returns on R&D, indicating better human capital endowment, lower unemployment rates, and a younger population structure that promotes knowledge generation and dissemination. In the European Union, India, and Mexico, knowledge spillovers also play a positive role in fostering innovation and the conversion of outcomes. The most innovative regions in these countries are those that provide adequate socio-economic conditions and are able to absorb, digest, and utilize R&D and knowledge spillovers. However, compared to developed regions in the European Union and the United States, as well as emerging countries like India and Mexico, China’s innovation dynamics rely more on agglomeration forces rather than traditional innovation drivers such as R&D investment, human capital endowment, and knowledge spillovers. The spatial range of knowledge spillover radiation from China major innovation sources is limited to metropolitan regions and hasn’t achieved inter-regional diffusion [

67]. To sum up, the country’s path to innovation is unique and diverse, just as an old saying goes: All roads lead to Rome.

6. Future Perspectives toward a Research Agenda

Equally important as theories on regional innovation systems, learning regions, innovative milieu and regional innovation networks, social filter theory has emerged as a significant branch within regional innovation theory. These theories attempt to identify the prerequisites for regional innovation and explain the link between regional innovation and economic performance. The difference lies in the fact that the former four innovation theories emphasize the importance of proximity and interrelationships among innovation actors, while social filter theory highlights how the socio-economic conditions of different regions generate impedance and permeation effects on R&D investment and knowledge spillovers, ultimately impacting the innovation transformation. When the impedance effect outweighs the permeation effect, strong filter occurs, thereby weakening the economic returns on R&D investment and knowledge spillovers. Conversely, when the impedance effect is smaller than the permeation effect, weak filter occurs, thereby enhancing the economic returns on R&D investment and knowledge spillovers. In summary, social filter theory is an important step to empirically research the role of regional innovation system, which also provides a new way to explain the heterogeneity of regional innovation and transformation capacity, as well as the asymmetry of inter-regional knowledge spillover. Objectively speaking, there are still some shortcomings in the theoretical framework and practical application of social filter theory that need to be addressed and improved. Hence, we recommend the following directions for future research.

Firstly, the concept and index system of social filter need to be further clarified. According to the idea conceived by the proponents of the concept of social filter, each nation and region has its unique social filter that hampers or sustains innovation [

46], and its permeability reflects the region ability to absorb innovation and transform it into economic activity. This is actually a relatively abstract concept, so that when scholars portray social filter, there are different descriptions of social conditions, socio-economic conditions, regional innovation systems, social institution conditions, social filter conditions, etc. At the same time, scholars haven’t sufficiently defined the connotation of social filter, and its constituent elements haven’t reached a consensus, and sometimes they are even simply regarded as a collection of economic structural variables. Notwithstanding “cultural filter device”, “social filter”, “institution plays the role of ‘social filter’ ” and other expressions in different literature, we believe that whether it is social structure, culture or institution and other aspects are just a dimension or domain of social filter. In order to avoid the generalization of the concept, the above description can be unified with social filter to characterize, which is more conducive to the construction and development of social filter theory [

68].

Secondly, future research should put more emphasis on the mechanisms how social filter influences regional innovation and knowledge spillover. Currently, the existing research on mechanisms primarily focuses on the interaction between social filter and internal regional innovation, as well as internal regional knowledge spillovers. However, this research is still at a general and descriptive analysis stage. There is a lack of more detailed research and understanding regarding how social filter affects the absorption, digestion, and utilization of knowledge, how the strength or weakness of permeability is manifested, and why it may act as an invisible barrier to knowledge spillovers. Particularly, there is short of in-depth analysis of the characteristics and mechanisms of the constituent elements of social filter. Moreover, we should pay attention to the externality of social filter and explore the mechanism, way and channel of its spatial spillover.

Thirdly, there is a need to improve the empirical methods and models that examine the impact of social filter on regional innovation and knowledge spillovers. Currently, the existing empirical studies have conducted relatively general tests. However, the process of how social filter influences the transformation of regional innovation into economic growth is complex. Social filter can have both facilitating and inhibiting effects, and a simplistic and absolute testing approach cannot effectively distinguish between these two effects. Additionally, the promotion of regional innovation for economic growth involves a series of transformations, from R&D investment to invention, invention to innovation, innovation to production, and ultimately, production to economic growth. But the accent is put on independent and localized analyses among most existing studies, lacking a comprehensive examination and identification of the entire process. Furthermore, these studies mostly rely on multiple regression models, with insufficient consideration of endogeneity issues.

Fourthly, until now the literature has been seemly dominated by case studies of developed countries or regions such as UE and the United States, and whether it is suitable for East Asian and African countries needs to be further explored. Another step would be clarify the content filtered by the social filter, whether it is filter redundant knowledge or digesting and absorbing beneficial knowledge. Regarding the spatial scale of social filter, on the one hand, different regions have different social filters, so what is the minimum spatial scale of the region. On the other hand, whether to divide regions by social filters or by regions to divide social filters, similar regions are sharing the same social filter. What’s more, whether the social filter can break through the regional scale, exist within the enterprise organization, and be affected by the organizational structure and culture of the enterprise.

Despite the research of social filter theory is still in the preliminary exploration stage, its ideological core is very enlightening. Social filter as a precondition for innovation to occur, and its interaction and integration research with innovation networks, innovation clusters, high-skilled talent flow [

69], localized knowledge spillover, innovation transformation in periphery regions and other topics will definitely have different gains and academic contributions, until it is introduced into the public vision, and then shines stronger theoretical vitality, and gradually enters the mainstream regional innovation theory system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.R.; formal analysis, J.R.; resources, L.L., B.P, W.Z; writing—original draft preparation, J.R.; writing—review and editing, J.R., L.L; visualization, L.L; supervision, J.R.; project administration, J.R.; funding acquisition, J.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. J.R., L.L., B.P. and W.Z.

Funding

This research was funded by The National Natural Science Foundation of China(grant number 42101179) and Humanities and Social Science Project of Ministry of Education(grant number 21YJC790096).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Note

| 1 |

the notion of innovation prone regions as regional systems that are “capable of transforming a larger share of their own R&D into innovation and economic activity” (Rodríguez-Pose, 1999, p.82). |

References

- Zoltaszek, A.; Olejnik, A. Regional effectiveness of innovation: leaders and followers of the EU NUTS 0 and NUTS 2 regions. Innovation-the European Journal of Social Science Research 2024, 37, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, P.; Uranga, M.G.; Etxebarria, G.J. Regional innovation systems: Institutional and organisational dimensions. 1997, 26, 475–491. Research policy 1997, 26, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iammarino, S. An evolutionary integrated view of regional systems of innovation: concepts, measures and historical perspectives. European planning studies 2005, 13, 497–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, A.; Morgan, K. Spaces of innovation: Learning, proximity and the ecological turn. Regional Studies 2012, 46, 1041–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K. The learning region: institutions, innovation and regional renewal. Regional studies 2007, 41 (Suppl. 1), S147–S159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breschi, S.; Lissoni, F. Localised knowledge spillovers vs. innovative milieux: Knowledge “tacitness” reconsidered. Papers in regional science 2001, 80, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R.P. The concept of innovative milieu and its relevance for public policies in European lagging regions. Papers in regional science 1995, 74, 317–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piazza, M.; Mazzola, E.; Abbate, L.; Perrone, G. Network position and innovation capability in the regional innovation network. European Planning Studies 2019, 27, 1857–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camagni, R.; Capello, R. Regional innovation patterns and the EU regional policy reform: towards smart innovation policies. Seminal Studies in Regional and Urban Economics: Contributions from an Impressive Mind 2017, 313-343.

- Capello, R.; Lenzi, C. Regional innovation patterns from an evolutionary perspective. Regional Studies 2018, 52, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Crescenzi, R. Research and development, spillovers, innovation systems, and the genesis of regional growth in Europe. Regional Studies 2008, 42, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. Innovation prone and innovation averse societies: Economic performance in Europe. Growth and change 1999, 30, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casi, L.; Resmini, L. Foreign direct investment and growth: Can different regional identities shape the returns to foreign capital investments? Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space 2017, 35, 1483–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Government reform and innovation performance in China. Papers in Regional Science 2024, 103, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Innovation and Regional Growth in The European Union. Berlin, 2011.

- Rodriguez-Pose, A.; Crescenzi, R. Mountains in a flat world: why proximity still matters for the location of economic activity. LSE Research Online Documents on Economics 2008, 1, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. Innovation prone and innovation averse societies: Economic performance in Europe. Growth and Change 1999, 30, 75–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, R.D. Making Democracy Work. Civil Traditions In Modern Italy. Princeton, 1993.

- D'Ingiullo, D.; Evangelista, V. Institutional quality and innovation performance: evidence from Italy. Regional Studies 2020, 54, 1724–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratesi, U. Regional Knowledge Flows and Innovation Policy: A Dynamic Representation. Regional Studies 2015, 49, 1859–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akçomak, İ.S.; Müller-Zick, H. Trust and inventive activity in Europe: causal, spatial and nonlinear forces. The Annals of Regional Science 2018, 60, 529–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Peralta, E.M.V. Innovation and Regional Growth in Mexico: 2000-2010. Growth and Change 2015, 46, 172–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. The territorial dynamics of innovation: a Europe-United States comparative analysis. Journal of Economic Geography 2007, 7, 673–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Storper, M. The territorial dynamics of innovation in China and India. Journal of Economic Geography 2012, 12, 1055–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N.; Thomas, E. Socio-institutional environment and innovation in Russia. Journal of East-West Business 2015, 21, 182–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. Spatial divisions of labour. Social structure and the geography of production. London, 1984.

- Ege, A.; Ege, A.Y. How to create a friendly environment for innovation? A case for Europe. Social indicators research 2019, 144, 451–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N. Psychology and the Geography of Innovation. Economic Geography 2017, 93, 106–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peiro-Palomino, J. The geography of social capital and innovation in the European Union. Papers in Regional Science 2019, 98, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Li, Y.; Ye, K.; Nie, T.; Liu, R.J.L. Does transport infrastructure inequality matter for economic growth? Evidence from China. Land 2021, 10, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Agostino, L.M.; Moreno, R. Green regions and local firms' innovation. Papers in Regional Science 2019, 98, 1585–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. R&D, Socio-economic conditions, and regional innovation in the U.S. Growth and Change 2013, 44, 287–320. [Google Scholar]

- Crescenzi, R. Innovation and regional growth in the enlarged Europe: the role of local innovative capabilities, peripherality, and education. Growth and Change 2005, 36, 471–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao-Osorio, B.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. From R&D to innovation and economic growth in the EU. Growth and Change 2004, 35, 434–455. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Crescenzi, R. Research and development, spillovers, innovation systems, and the genesis of regional growth in Europe. Regional Studies 2008, 42, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Comptour, F. Do clusters generate greater innovation and growth? An analysis of European regions. Professional Geographer 2012, 64, 211–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosconi, F.; D’Ingiullo, D. Institutional quality and innovation: evidence from Emilia-Romagna. Economics of Innovation and New Technology 2023, 32, 165–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beugelsdijk, S. Entrepreneurial culture, regional innovativeness and economic growth. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 2007, 17, 187–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Agostino, G.; Scarlato, M. Innovation, socio-institutional conditions and economic growth in the italian regions. Regional Studies 2015, 49, 1514–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Pose, A.; Di Cataldo, M. Quality of government and innovative performance in the regions of Europe. Journal of Economic Geography 2015, 15, 673–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, A.; Xia, S.; Ye, Z.P.; Cao, D.; Jing, Y.; Li, H. Can innovation really bring economic growth? The role of social filter in China. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics 2020, 53, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Zhang, M. Government institutions and the dynamics of urban growth in China. Journal of Regional Science 2019, 59, 633–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. An ‘integrated’ framework for the comparative analysis of the territorial innovation dynamics of developed and emerging countries. Journal of Economic Surveys 2012, 26, 517–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragkandreas; Thanos, When innovation does not pay off: introducing the “European regional paradox”. European Planning Studies 2013, 21, 2078–2086. [CrossRef]

- Kaneva, M.; Untura, G. The impact of R&D and knowledge spillovers on the economic growth of Russian regions. Growth and Change 2019, 50, 301–334. [Google Scholar]

- Capello, R.; Caragliu, A.; Nijkamp, P. Territorial capital and regional growth: increasing returns in knowledge use. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie 2011, 102, 385–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, M. Towards the new economic geography in the brain power society. Regional Science and Urban Economics 2007, 37, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griliches, Z. Productivity, R&D and basic research at firm levelin the 1970s. American Economic Review 1986, 76, 141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Knockaert, M.; Spithoven, A.; Clarysse, B. The knowledge paradox explored: what is impeding the creation of ICT spin-offs? Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 2010, 22, 479–493. [Google Scholar]

- Sterlacchini, A. R&D, higher education and regional growth: Uneven linkages among European regions. Research Policy 2008, 37, 1096–1107. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Ren, J. Research progress on the relationship between social filter and economic growth. Economic Dynamics 2016, 667, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Crescenzi, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Systems of Innovation and Regional Growth in the EU: Endogenous vs. External Innovative Activities and Socio-Economic Conditions. Berlin, 2009; p 167-191.

- Crescenzi, R.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Infrastructure and regional growth in the European Union. Papers in Regional Science 2012, 91, 487–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurikka, H.; Kolehmainen, J.; Sotarauta, M.; Nielsen, H.; Nilsson, M. Regional opportunity spaces – observations from Nordic regions. Regional Studies 2022, 56, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggi, M.R.; Maggioni, M.A. Regional Growth and the Co-Evolution of Clusters: The Role of Labour Flows. Berlin, 2009; p 245-267.

- Augier, M.; Guo, J.; Rowen, H. The Needham Puzzle Reconsidered: Organizations, Organizing, and Innovation in China. Management and Organization Review 2016, 12, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearmur, R.; Bonnet, N. Does local technological innovation lead to local development? A policy perspective. Regional Science Policy & Practice 2011, 3, 249–270. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, Q.; Yuan, L.; Yao, Z.; Zeng, L. The impact of R&D elements flow and government intervention on China’s hi-tech industry innovation ability. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 2021, 35, 856–874. [Google Scholar]

- Caragliu, A.; Nijkamp, P. The impact of regional absorptive capacity on spatial knowledge spillovers: the Cohen and Levinthal model revisited. Applied Economics 2012, 44, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capello, R.; Caragliu, A.; Fratesi, U. Breaking Down the Border: Physical, Institutional and Cultural Obstacles. Economic Geography 2018, 94, 485–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, M.S.; Wolfe, D.A.; Garkut, D. No place like home? The embeddedness of innovation in a regional economy. Review of International Political Economy 2000, 7, 688–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotarauta, M. Policy learning and the ‘cluster-flavoured innovation policy’ in Finland. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 2012, 30, 780–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggian, A.; Partridge, M.; Malecki, E.J.I.J. o. U.; Research, R. Creating an environment for economic growth: Human capital, creativity or entrepreneurship? International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 2017, 41, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, R.J.; Sala-I-Martin, X. Economic Growth. New York, 1995.

- Ren, J. Innovation, Social Filter, and Regional Economic Growth. Shanxi, 2021.

- Goncalves, E.; Almeida, E. Innovation and spatial knowledge spillovers: evidence from Brazilian patent data. Regional Studies 2009, 43, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Pose, A.; Wilkie, C. Putting China in perspective: a comparative exploration of the ascent of the Chinese knowledge economy. Cambridge Journal of Regions Economy and Society 2016, 9, 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Lai, L. Social filter theory: a review of regional innovation theory. Regional Economic Review 2023, 63, 145–155. [Google Scholar]

- Aldieri, L.; Kotsemir, M.; Vinci, C.P. The role of labour migration inflows on R&D and innovation activity: evidence from Russian regions. Foresight 2020, 22, 437–468. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).