Submitted:

17 October 2024

Posted:

23 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

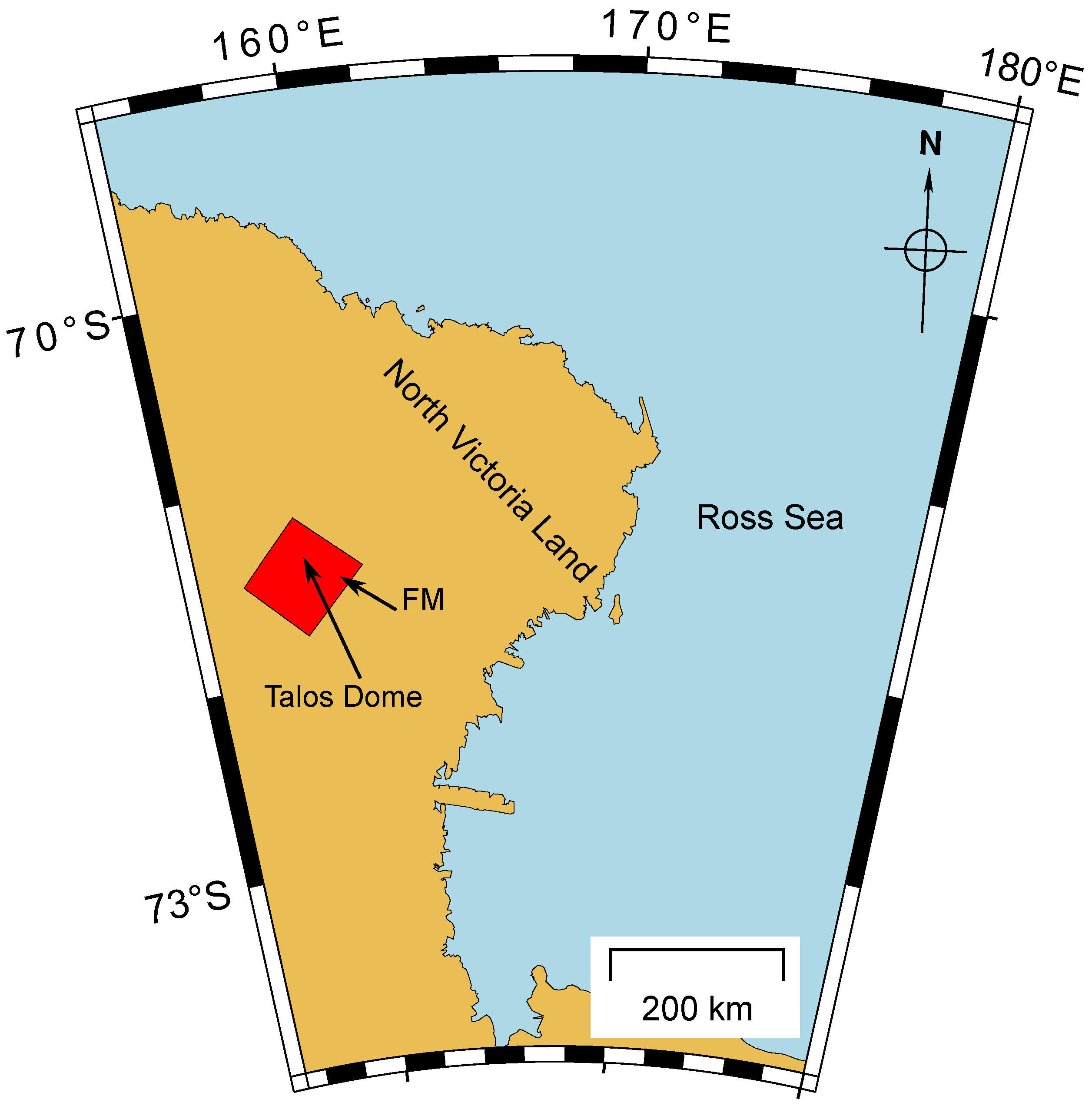

1. Introduction

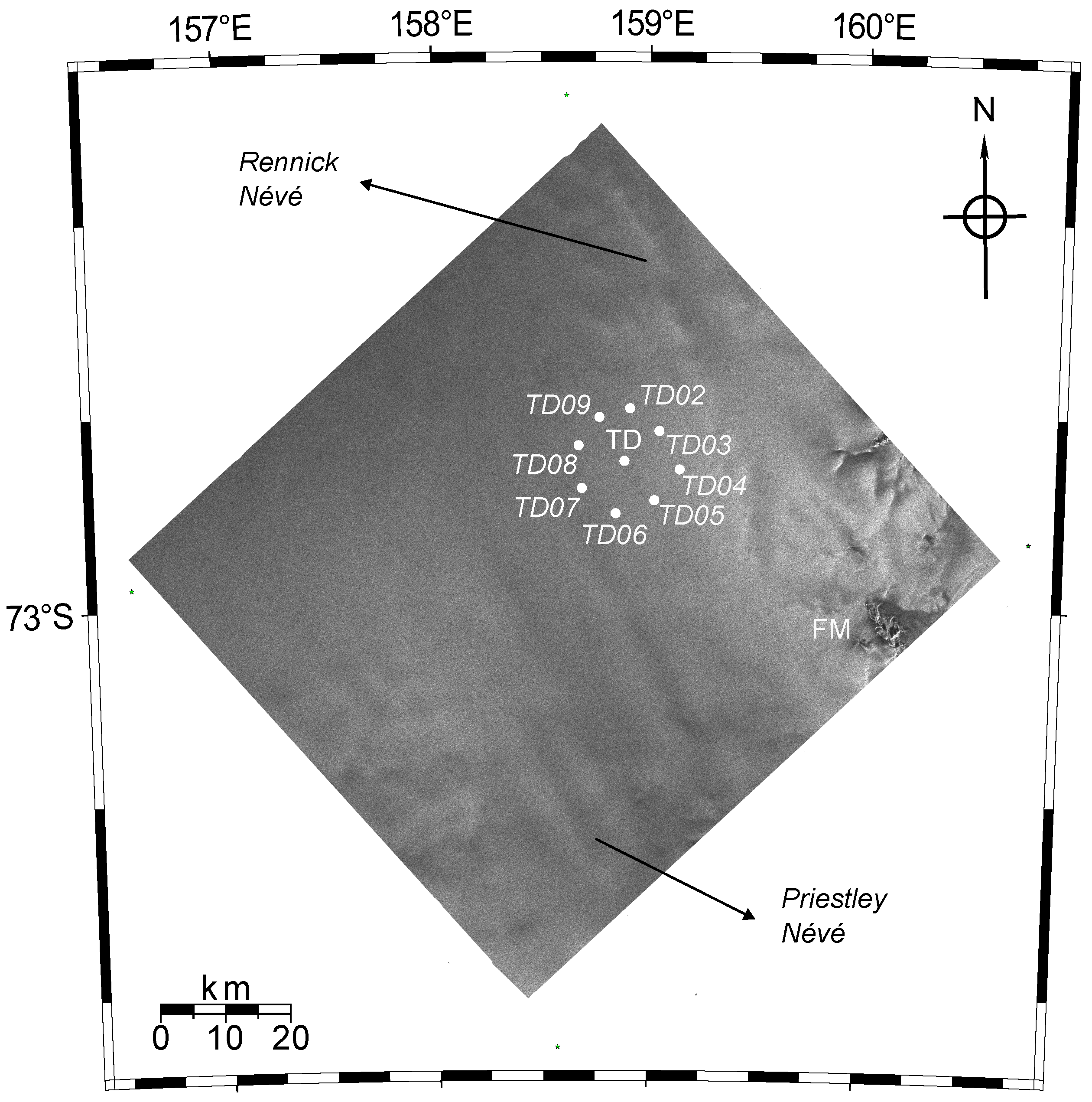

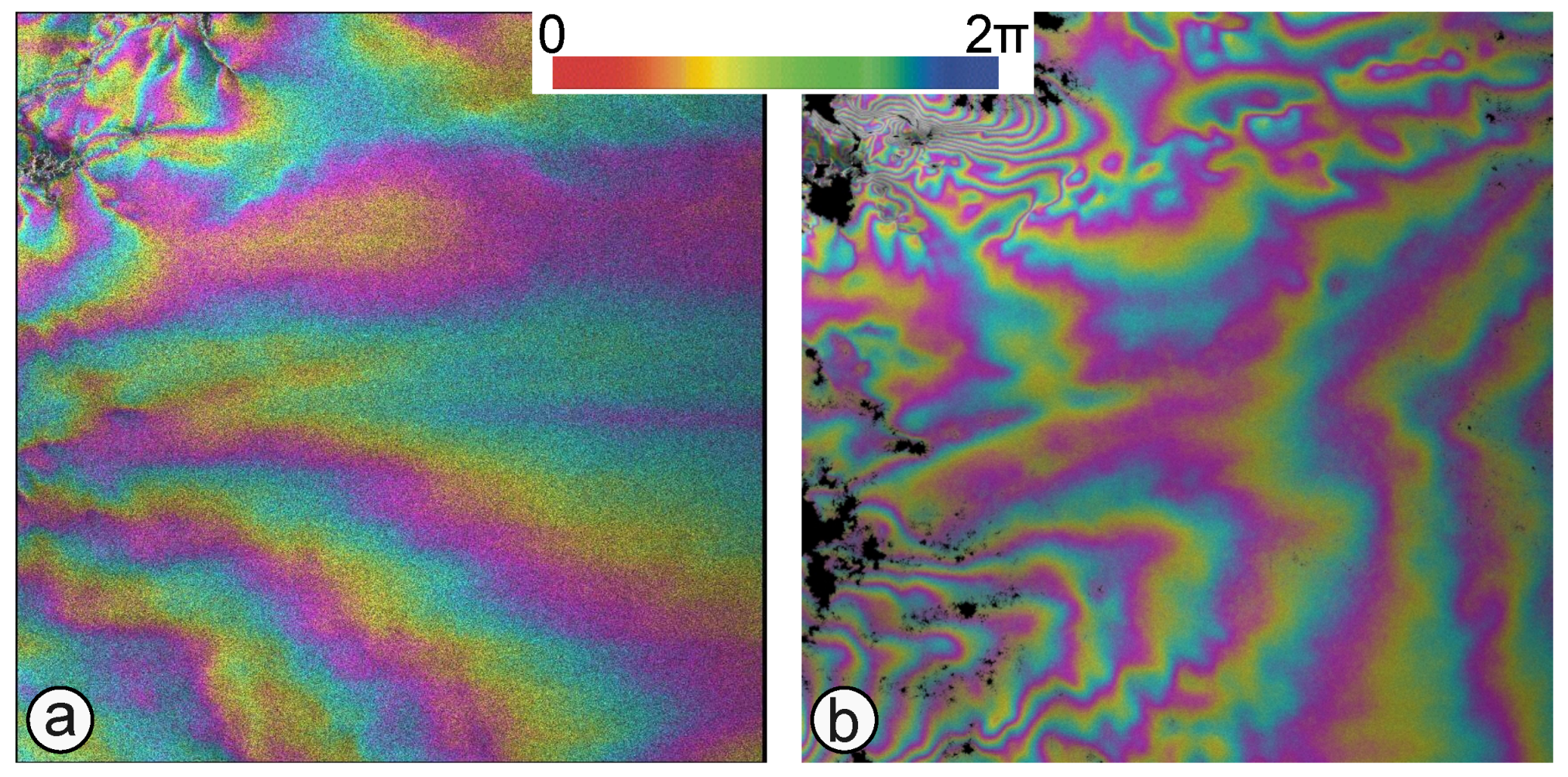

2. Methods and Database: The Synthetic Aperture Radar

3. Results

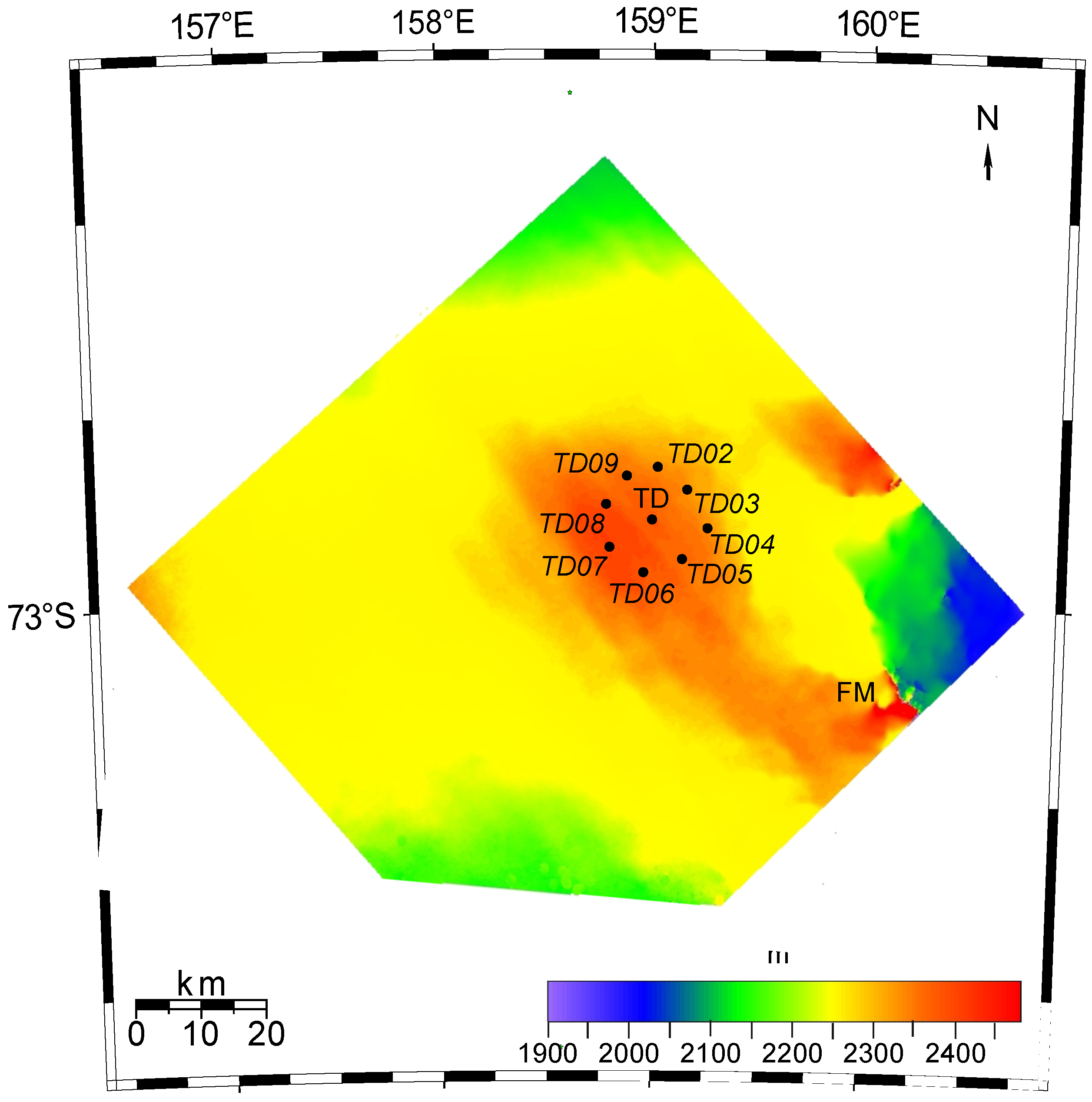

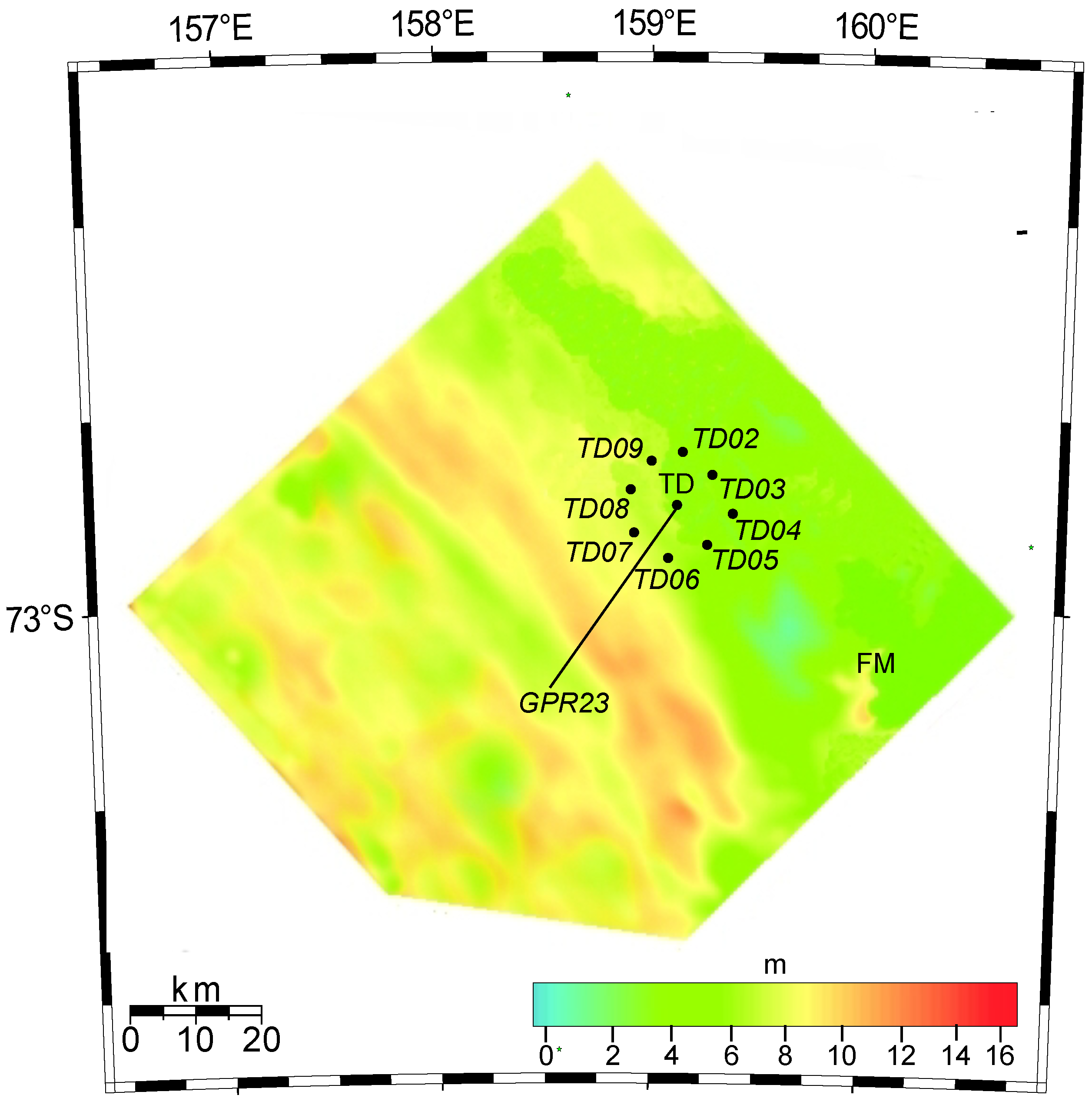

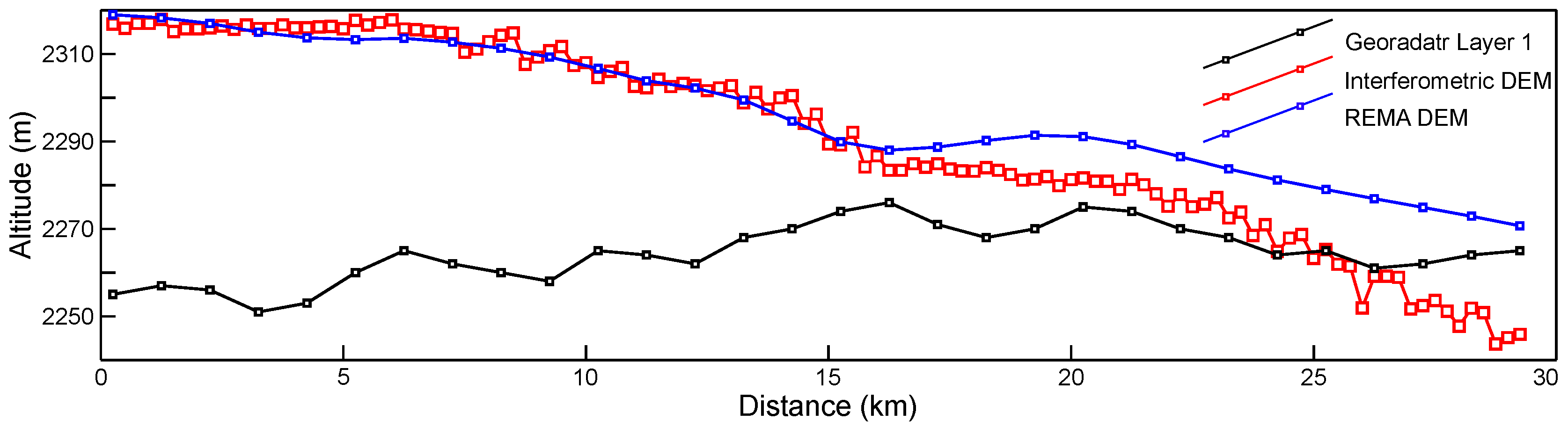

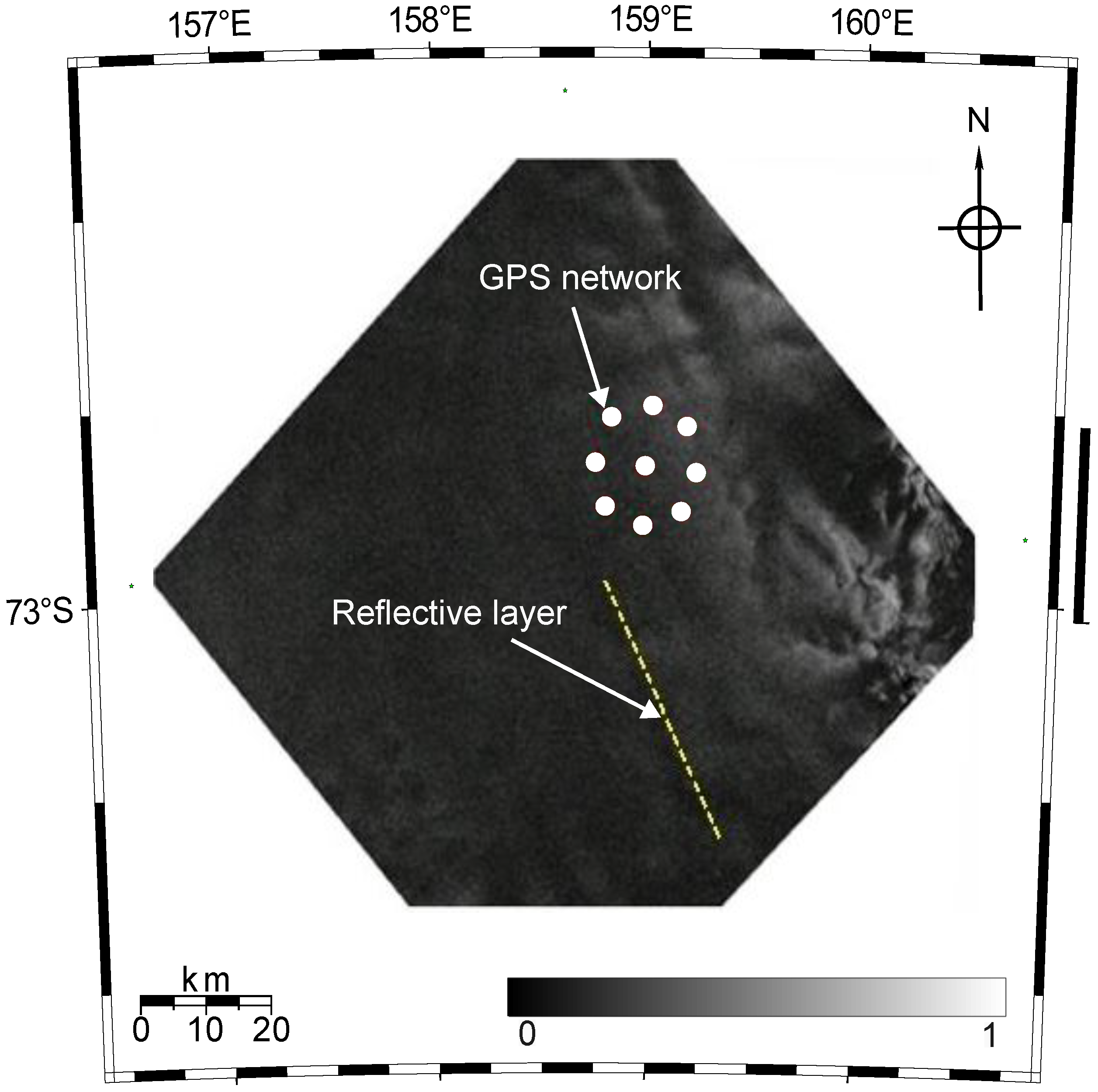

3.1. Talos Dome DEM and Magnitude Image Analysis

- the penetration of the radar bands in cold firn;

- fitting errors associated with the ground control points (GCP) used to refine the interferometric baselines;

- phase noise resulting from differentiating the interferograms one or more times to remove the contribution of phase difference due to motion. Despite this significant error budget, the correlations between the REMA DEM and the interferometric DEM are high.

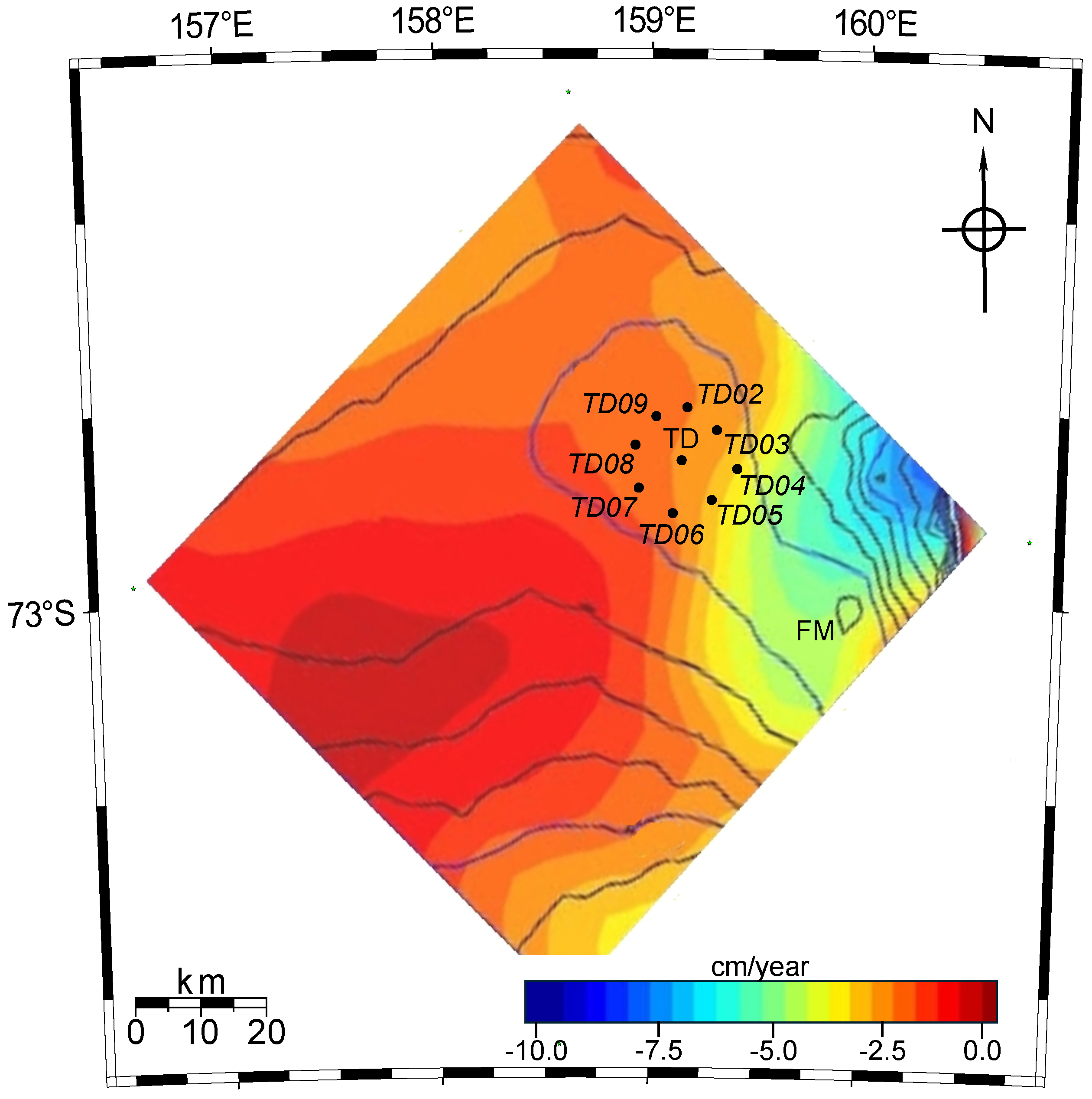

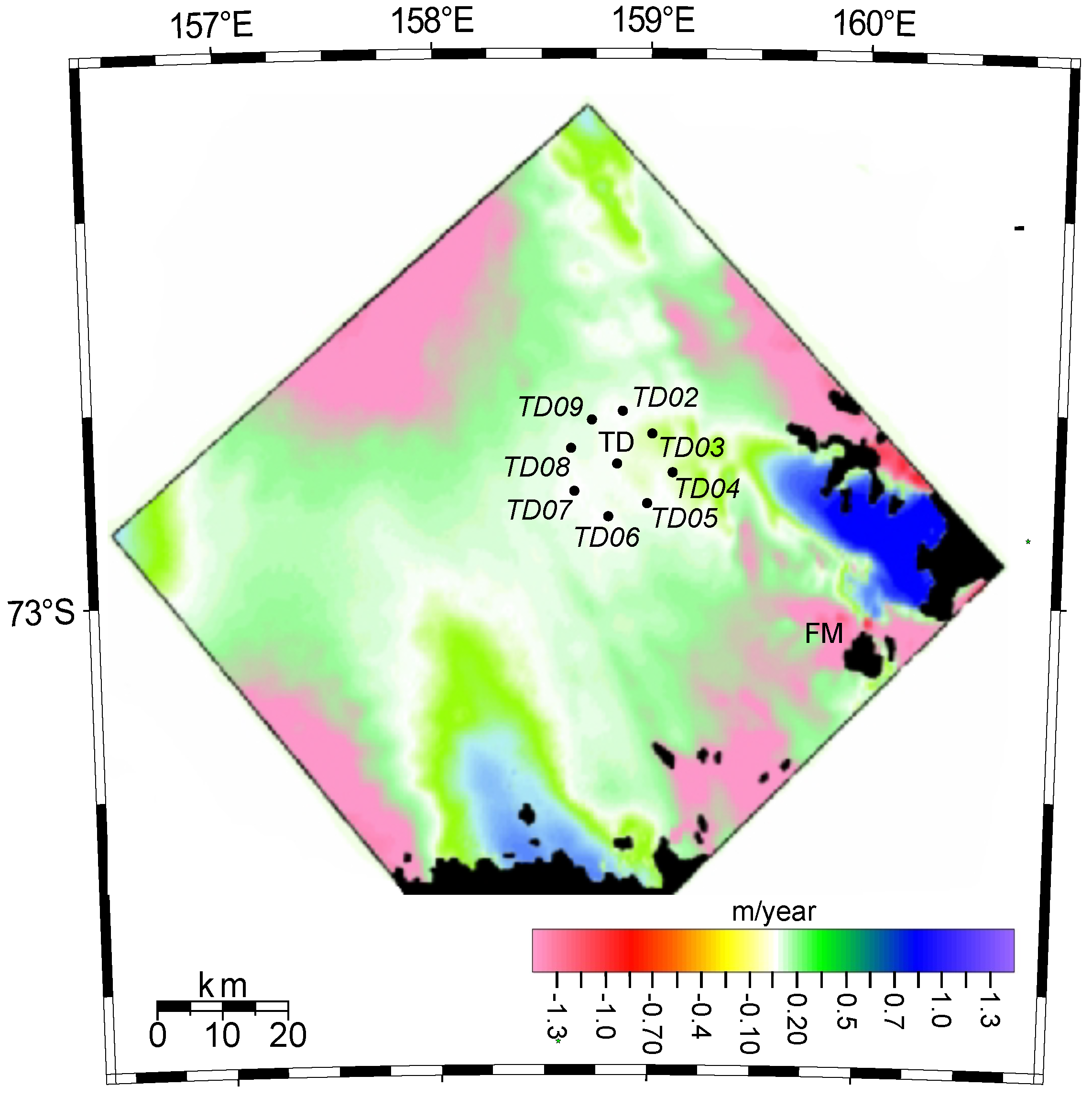

3.2. The Ice Flow Velocity Image

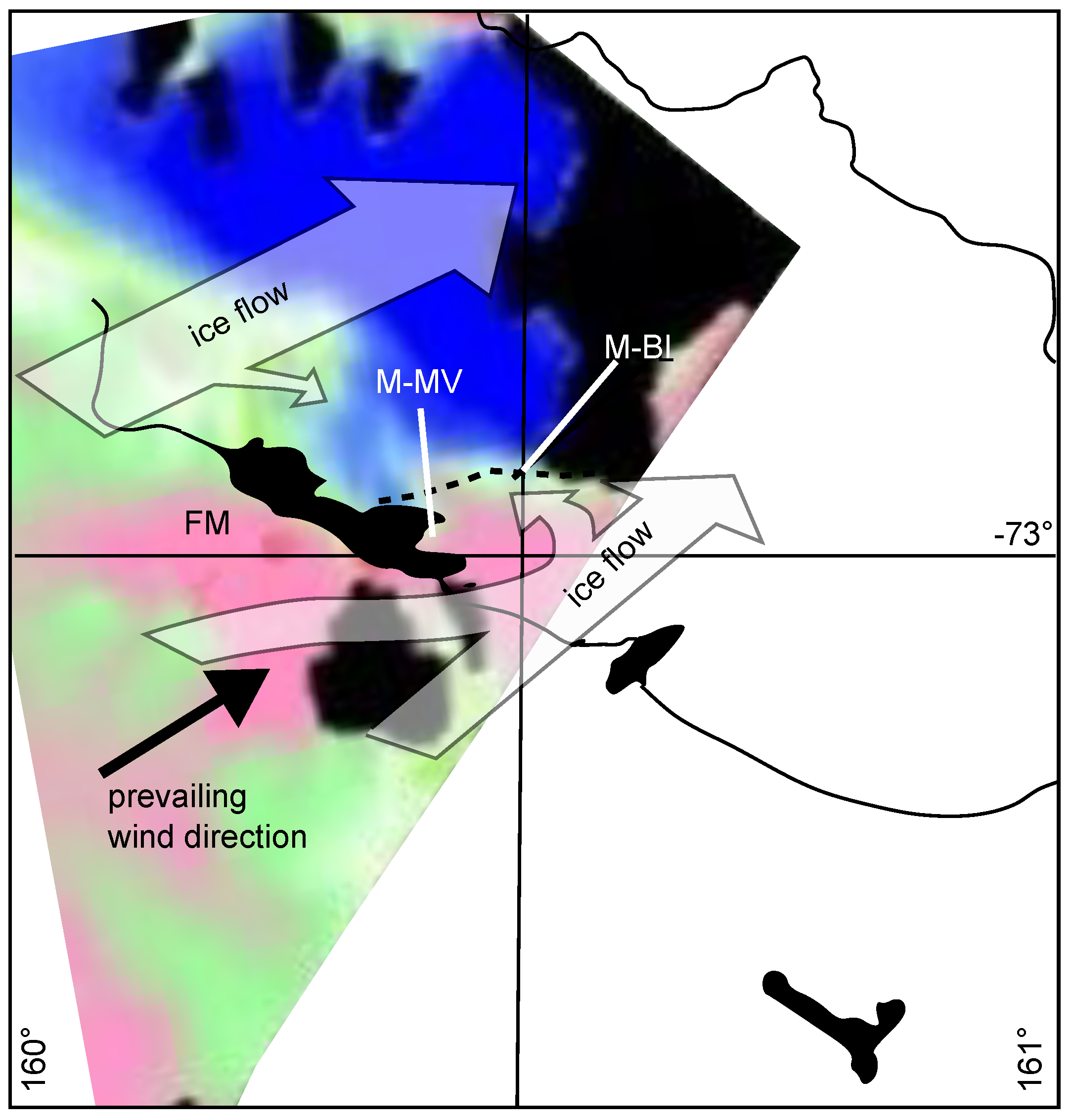

3.3. The Frontier Mountain Area

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TD | Talos Dome |

| FM | Frontier Mountain |

| PNRA | Programma Nazionale di Ricerche in Antartide |

| TALDICE | The TALos Dome Ice CorE |

| RES | Radio Echo Sounding |

| DEM | Digital Elevation Model |

| SAR | Synthetic Apertur Radar |

References

- Mouginot, J.; Scheuchl, B.; Rignot, E. Mapping of ice motion in Antarctica using synthetic-aperture radar data. Remote Sensing 2012, 4, 2753–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, K.E.; Willis, I.C.; Benedek, C.L.; Williamson, A.G.; Tedesco, M. Toward monitoring surface and subsurface lakes on the Greenland ice sheet using Sentinel-1 SAR and Landsat-8 OLI imagery. Frontiers in Earth Science 2017, 5, 251152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Floricioiu, D. The penetration effects on TanDEM-X elevation using the GNSS and laser altimetry measurements in Antarctica. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 2017, 42, 1593–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milillo, P.; Rignot, E.; Mouginot, J.; Scheuchl, B.; Morlighem, M.; Li, X.; Salzer, J.T. On the short-term grounding zone dynamics of Pine Island Glacier, West Antarctica, observed with COSMO-SkyMed interferometric data. Geophysical Research Letters 2017, 44, 10–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedl, P.; Weiser, F.; Fluhrer, A.; Braun, M.H. Remote sensing of glacier and ice sheet grounding lines: A review. Earth-Science Reviews 2020, 201, 102948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legresy, B.; Rignot, E.; Tabacco, I.E. Constraining ice dynamics at Dome C, Antarctica, using remotely sensed measurements. Geophysical research letters 2000, 27, 3493–3496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbini, S.; Frezzotti, M.; Gandolfi, S.; Vincent, C.; Scarchilli, C.; Vittuari, L.; Fily, M. Historical behaviour of Dome C and Talos Dome (East Antarctica) as investigated by snow accumulation and ice velocity measurements. Global and Planetary Change 2008, 60, 576–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezzotti, M.; Bitelli, G.; De Michelis, P.; Deponti, A.; Forieri, A.; Gandolfi, S.; Maggi, V.; Mancini, F.; Remy, F.; Tabacco, I.E.; et al. Geophysical survey at Talos Dome, East Antarctica: the search for a new deep-drilling site. Annals of Glaciology 2004, 39, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folco, L.; Capra, A.; Chiappini, M.; Frezzotti, M.; Mellini, M.; Tabacco, I.E. The Frontier Mountain meteorite trap (Antarctica). Meteoritics & Planetary Science 2002, 37, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, M.; Winther, J.G.; Isaksson, E. Measuring snow and glacier ice properties from satellite. Reviews of Geophysics 2001, 39, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, A.K.; Goldstein, R.M.; Zebker, H.A. Mapping small elevation changes over large areas: Differential radar interferometry. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 1989, 94, 9183–9191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, R.M.; Engelhardt, H.; Kamb, B.; Frolich, R.M. Satellite radar interferometry for monitoring ice sheet motion: application to an Antarctic ice stream. Science 1993, 262, 1525–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howat, I.M.; Porter, C.; Smith, B.E.; Noh, M.J.; Morin, P. The reference elevation model of Antarctica. The Cryosphere 2019, 13, 665–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scharroo, R.; Visser, P. Precise orbit determination and gravity field improvement for the ERS satellites. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans 1998, 103, 8113–8127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rignot, E.; Forster, R.; Isacks, B. Interferometric radar observations of glaciar san rafael, chile. Journal of Glaciology 1996, 42, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rignot, E.; Forster, R.; Isacks, B. Mapping of glacial motion and surface topography of Hielo Patagónico Norte, Chile, using satellite SAR L-band interferometry data. Annals of Glaciology 1996, 23, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinert, M.; Ferraccioli, F.; Schwabe, J.; Bell, R.; Studinger, M.; Damaske, D.; Jokat, W.; Aleshkova, N.; Jordan, T.; Leitchenkov, G.; et al. New Antarctic gravity anomaly grid for enhanced geodetic and geophysical studies in Antarctica. Geophysical Research Letters 2016, 43, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; Nixon, D.; Hurley, J. Semi-automated classification of river ice types on the Peace River using RADARSAT-1 synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering 2003, 30, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterson, W.S.B. Physics of glaciers; Butterworth-Heinemann, 1994.

- Rémy, F.; Shaeffer, P.; Legrésy, B. Ice flow physical processes derived from the ERS-1 high-resolution map of the Antarctica and Greenland ice sheets. Geophysical Journal International 1999, 139, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guneriussen, T.; Hogda, K.A.; Johnsen, H.; Lauknes, I. InSAR for estimation of changes in snow water equivalent of dry snow. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2001, 39, 2101–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoen, E.W. A correlation-based approach to modeling interferometric radar observations of the Greenland ice sheet; Stanford University, 2002.

- Rignot, E.; Echelmeyer, K.; Krabill, W. Penetration depth of interferometric synthetic-aperture radar signals in snow and ice. Geophysical Research Letters 2001, 28, 3501–3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrésy, B.; Rémy, F. Along track repeat satellite radar altimetry over land surfaces, applications in Antarctica. Rem. Sens. Environment 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez, E.; Martin, J. Theory and design of interferometric synthetic aperture radars. IEE proceedings f (radar and signal processing). IET, 1992, Vol. 139, pp. 147–159.

- Mouginot, J.; Rignot, E.; Scheuchl, B. Continent-wide, interferometric SAR phase, mapping of Antarctic ice velocity. Geophysical Research Letters 2019, 46, 9710–9718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folco, L.; Mellini, M.; others. 1990-2000: Ten years of Antarctic meteorite search by the Italian PNRA. In Antarctic Meteorites XXV; 2000; pp. 8–9.

- Cassidy, W.; Harvey, R.; Schutt, J.; Delisle, G.; Yanai, K. The meteorite collection sites of Antarctica. Meteoritics 1992, 27, 490–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welten, K.; Nishiizumi, K.; Masarik, J.; Caffee, M.; Jull, A.; Klandrud, S.; Wieler, R. Cosmic-ray exposure history of two Frontier Mountain H-chondrite showers from spallation and neutron-capture products. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 2001, 36, 301–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welten, K.C.; Nishiizumi, K.; Caffee, M.W.; Schäfer, J.; Wieler, R. Terrestrial ages and exposure ages of Antarctic H-chondrites from Frontier Mountain, North Victoria Land. Antarctic Meteorite Research. Twentythird Symposium on Antarctic Meteorites, NIPR Symposium No. 12, held June 10-12, 1998, at the National Institute of Polar Research, Tokyo. Editor in Chief, Takeo Hirasawa. Published by the National Institute of Polar Research, 1999, p. 94, 1999, Vol. 12, p. 94.

- Delisle, G.; Franchi, I.; Rossi, A.; Wieler, R. Meteorite finds by EUROMET near Frontier Mountain, North Victoria Land, Antarctica. Meteoritics 1993, 28, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coren, F.; Delisle, G.; Sterzai, P. Ice dynamics of the Allan Hills meteorite concentration sites revealed by satellite aperture radar interferometry. Meteoritics & Planetary Science 2003, 38, 1319–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delisle, G. Sub-ice topography of selected areas in central Dronning Maud Land, east Antarctica (Ground-Based RES Survey). Geologisches Jahrbuch. Reihe B, Geophysik 2005, 97, 197. [Google Scholar]

- Delisle, G.; Schultz, L.; Suter, M.; Wölfli, W.; Spettel, B.; Weber, H. Meteorite finds near Frontier Mountain Range in North Victoria Land. Geologisches Jahrbuch. Reihe E, Geophysik 1989, pp. 483–513.

| Ref. Orbit | Image Num. | Ref. Date | Interf. Orbit | Image Num. | Interf. Date | Elapsed time | (m)a | Ambig. height((m)b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1-23949 | 1 | 1996.01.12 | E2-04276 | 2 | 1996.20.13 | 1 day | ∼132 | ∼68 |

| E1-24951 | 3 | 1996.04.22 | E2-05278 | 4 | 1996.04.23 | 1 day | ∼13 | ∼692 |

| TD | 03 | 04 | 05 |

|---|---|---|---|

| INT(m/year) | 0.42±0.14 | 0.35±0.11 | 0.15±0.25 |

| GPS(m/year) | 0.343±13 | 0.336±13 | 0.161±13 |

| Heading | 76° | 82° | 122° |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).