1. Introduction

Since the first case of COVID-19 was identified in early 2020 and over the more than three years of the pandemic, Brazil has recorded almost 39 million cases and 712,000 deaths from the disease, according to notifications from state health departments to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, available on the Coronavírus/Brasil dashboard[

1]. In 2024 alone, 595,758 cases and 3,567 deaths were recorded, data updated on May 29.

Considering that individual health is a basic and universal social right and that its guarantee requires efforts to build more just and equitable societies[

2]. Brazil has a universal health system (SUS) and a robust system for responding to public health emergencies, as demonstrated throughout the COVID-19 era. However, the management experienced during the period underutilized these characteristics, placing Brazil in second place among countries with the highest number of fatal victims of COVID-19[

3].

In Brazil, the first confirmed cases of COVID-19 began in areas with better living conditions and a greater flow of contacts with the outside world, with the first report on February 26, 2020, and the first death recorded in the city of São Paulo on March 12, 2020. And, cases like this also followed in metropolitan cities such as Rio de Janeiro and Fortaleza[

4,

5].

The city of São Paulo is the largest, richest and one of the most unequal cities in the country, and ranks 8th as the most populous city in the world,

with 12,200,180 inhabitants[

6]

. It is considered the largest economic, financial and cultural center in Latin America, and during the COVID-19 pandemic, social inequalities were accentuated , worsening the living conditions of the poorest, women and the black population[

7].

Several studies have shown that COVID-19 does not affect everyone or everywhere with the same speed and intensity[

8], and it has been found that the pandemic found, in metropolitan areas, a very favorable environment for its spread. However, it quickly reached the poorest social classes and most precarious areas, with devastating effects on residents both in the most distant peripheries and in the central enclaves of slums and favelas[

9]. Especially due to two fundamental factors: housing conditions characterized to a large extent by precariousness and excessive density, and working conditions with a huge contingent of the population dedicated to informal and precarious work and with greater spatial mobility, making any more effective strategy of social isolation impossible[

9,

10].

COVID-19 has highlighted the weight of spatial inequalities, as mortality, lethality and incidence rates of the disease are higher in the poorest regions, where areas of high social vulnerability are concentrated[

11]. In addition, the start and course of the vaccination campaign are expected to have a predictable impact with a reduction in serious cases and deaths in the medium term.

It is possible that in each city, distinct urban structures also played an important role, along with other factors, in the advancement of the pandemic. It is therefore worth examining how urban structure relates, locally, to the spread of COVID-19. Thus, it is particularly important to understand the process of dissemination of the COVID-19 pandemic in the city of São Paulo.

Thus, the objective is to analyze the effects of vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 on the incidence, lethality and mortality from COVID-19 in the city of São Paulo, in the period 2020-2022.

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design and Database

Data were collected in March 2023, considering COVID-19 cases and deaths registered in the period between January 1, 2020 and December 31, 2022. Data were extracted from the official public data system. Confirmed cases and deaths were collected from the health information systems responsible for recording, analyzing and publishing the data.

All new cases and deaths that occurred in the city of São Paulo and were reported by the city to the State Health Department through compulsory notification were considered.

To minimize possible discrepancies and ensure quality and reliability, data were extracted by two researchers independently.

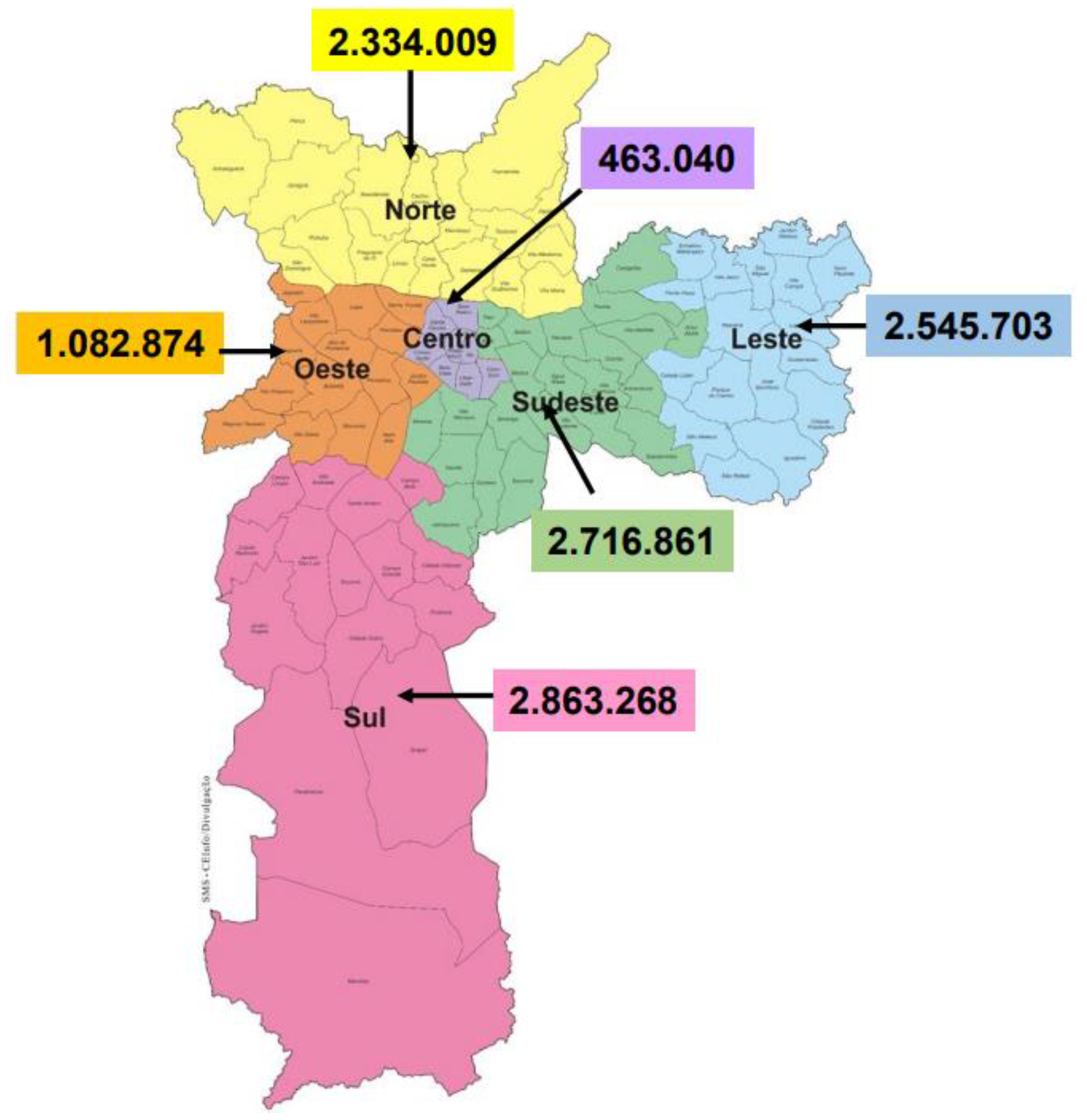

Figure 1.

Map of the Municipality of São Paulo according to the six Regional Health Coordinators. Source: SEADE Foundation – Projected population for 2023[

13].

Figure 1.

Map of the Municipality of São Paulo according to the six Regional Health Coordinators. Source: SEADE Foundation – Projected population for 2023[

13].

The Regional Health Coordinating Offices are subdivided into six strata and include the following sub-prefectures: CRS East – Sub-prefectures of São Mateus; CRS Southeast – Sub-prefectures of Vila Mariana/Jabaquara, Ipiranga, Mooca/Aricanduva/Formosa/Carrão, Penha, Vila Prudente/Sapopemba; CRS Center – Sub-prefectures of Sé and Santa Cecilia; CRS South – Sub-prefectures of Campo Limpo, M'Boi Mirim, Santo Amaro, Capela do Socorro, Parelheiros; CRS West – Sub-prefectures of Lapa/Pinheiros, Butantã; and CRS North – Sub-prefectures of Perus, Pirituba, Freguesa/Brasilândia, Casa Verde/Cachoeirinha, Santana/Tucuruvi/Jaçanã/Tremembé.

Study Population Data

All notifications of new cases and deaths were considered using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10) of U07.1 “COVID-19, virus not identified” and a diagnosis of COVID-19 disease confirmed by laboratory tests, or U07.2 “COVID-19, virus not identified” associated with a diagnosis of the disease, according to clinical, laboratory criteria, or epidemiological confirmation[

14].

This study involves only the analysis of secondary data and all these sources of information are in the public domain. No additional information that is not freely accessible was collected. Furthermore, no personally identifiable information was obtained for this study.

Statistical Analysis

The collected data were organized into a spreadsheet using Microsoft® Excel 2016. Three trends were used and calculated:

incidence rates (new cases/population) expressed per 100,000 inhabitants during a given period in a specified population ;

mortality (deaths/population) of COVID 19, expressed per 100,000 inhabitants and

lethality or case-fatality which consists of the proportion of individuals diagnosed with COVID 19 who died, and is therefore a measure of severity among the cases detected. (total deaths / total cases ) expressed as a percentage (%).

All rates were expressed as a daily percentage, between January 2020 and December 2022, according to the population projection according to the Regional Health Coordination Offices of the municipality of São Paulo.

For trend analysis, the methods proposed by Antunes and Cardoso[15] were used. Thus, the Prais-Winsten regression[16] model was used , which allowed first-order autocorrelation corrections to be performed on the values organized in time, between the years 2020, 2021 and 2022. The following values were estimated: angular coefficient of linear regression (b) and respective probability (p) considering the significance level of 95% confidence interval (95%CI).

The data modeling process includes transformation rates (dependent variable = Y value) into a base 10 logarithmic function. The independent variable (X value) was the days of the historical series.

The results of the logarithmic rates (B) of the Prais-Wisten regression[16] allowed estimation of the percentage variation of daily change ( Daily Percent Change – DPC) in each regional coordination office of the city of São Paulo, with the respective confidence intervals (95% CI)

This procedure made it possible to classify the temporal trend of COVID-19 rates as increasing, decreasing or stationary, and to quantify the percentage variation in the daily incidence, mortality and fatality rates[

17]. The trend was considered stationary when the coefficient was not significantly different from zero (p>0.05).

To facilitate the visualization of lethality trends, we reduced the random variation of the graph using the 5th order moving average technique[

15]. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 15.1 software ( College Station , TX, 2018).

3. Results

Monthly Distribution of Confirmed SARS Cases and Deaths for COVID-19 in the City of São Paulo, According to its Regional Health Coordinators

In the period analyzed (2020-2023), the city of São Paulo registered 1,988,657 confirmed cases of COVID-19, equivalent to approximately 17% of its total population being infected at least once by the SARS CoV-2 virus, with a fatal outcome in 0.4% of its total population. According to the coordination regions, the region that presented the highest absolute number of cases was the CRS Sul (524,406 confirmed cases), followed by the CRS Sudeste (488,129 confirmed cases), representing, respectively, 18.7% and 18% of its total population. The latter presented 0.46% of deaths in the population.

The highest number of new SARS COVID-19 cases was recorded in January 2022 (212,931 cases) (

Table 1). This was the month with the highest relative frequency for all regions, with emphasis on the West CRS (11.65%) of confirmed cases. Regarding the absolute number of cases, the region with the highest number of cases was the South (59,530 cases), followed by the Southeast CRS (50,294 cases). This explains why they are the most populated regions of the city of São Paulo.

Regarding the number of deaths, 46,436 deaths from SARS COVID-19 were recorded in the city of São Paulo, and the highest number of deaths recorded in the month occurred in March and April 2021 (6,322 deaths and 5,704 deaths). And, in this same period, the same peak in the number of deaths was recorded in all regions of the city of São Paulo, with March and April standing out as the most severe months in terms of the relative frequency of deaths. Highlighting the CRS Leste with the highest relative frequency (15.86%) in this same month of March 2021.

Lethality (%) According to Regional Health Coordination Offices. Municipality of São Paulo, Brazil

Regarding lethality, the City of São Paulo presented 2.34% in the period between January 2020 to December 2022, the regions of the city of São Paulo, which presented the highest lethality were the CRS Norte (2.80%), being higher at the beginning of the pandemic (2020) followed by the CRS Leste (2.72%) and Sudeste (2.57%) (

Table 2).

Temporal Trends in Lethality and Incidence and Mortality Rates of COVID-19, in the City of São Paulo and its Regions, in the period 2020-2022

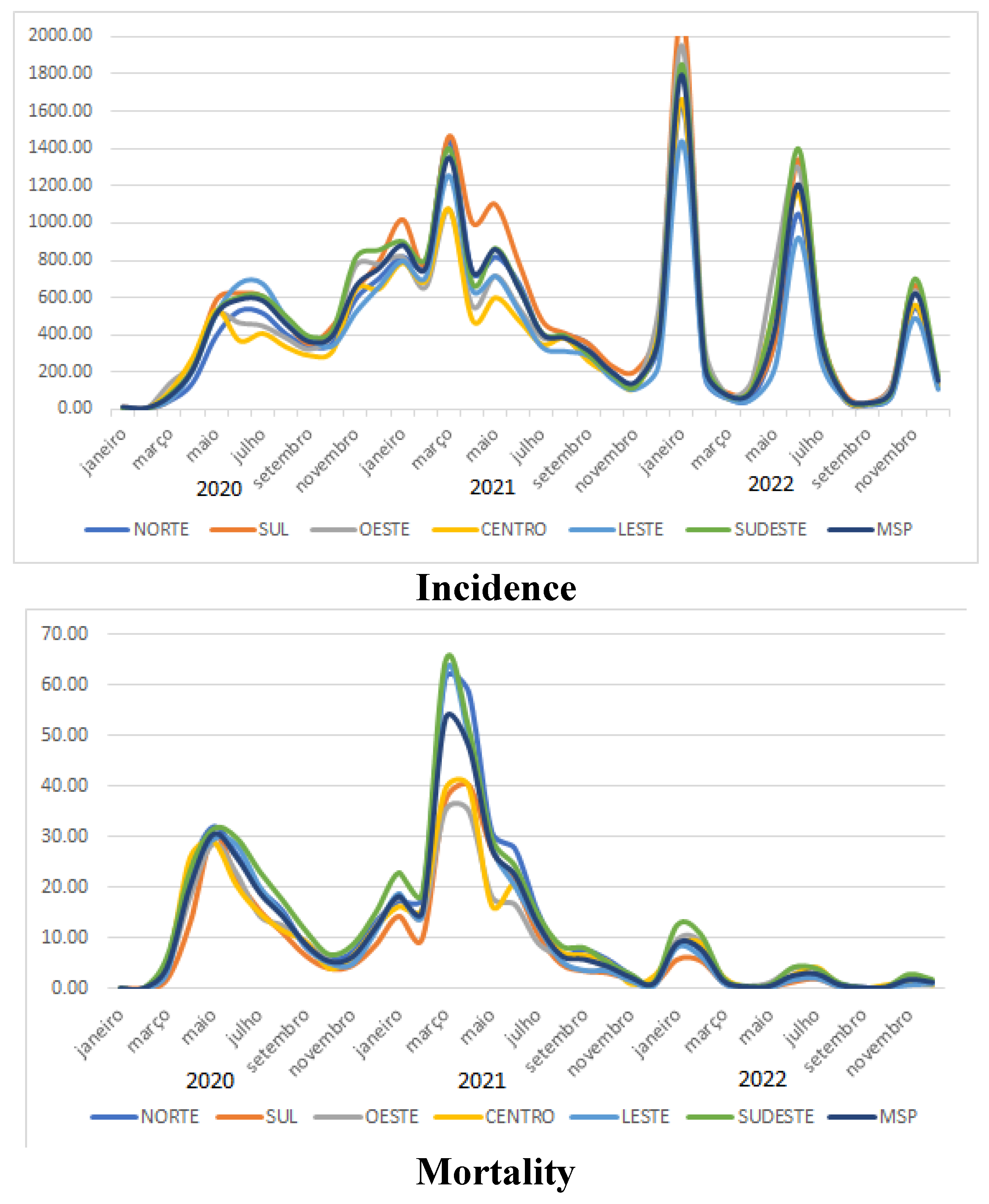

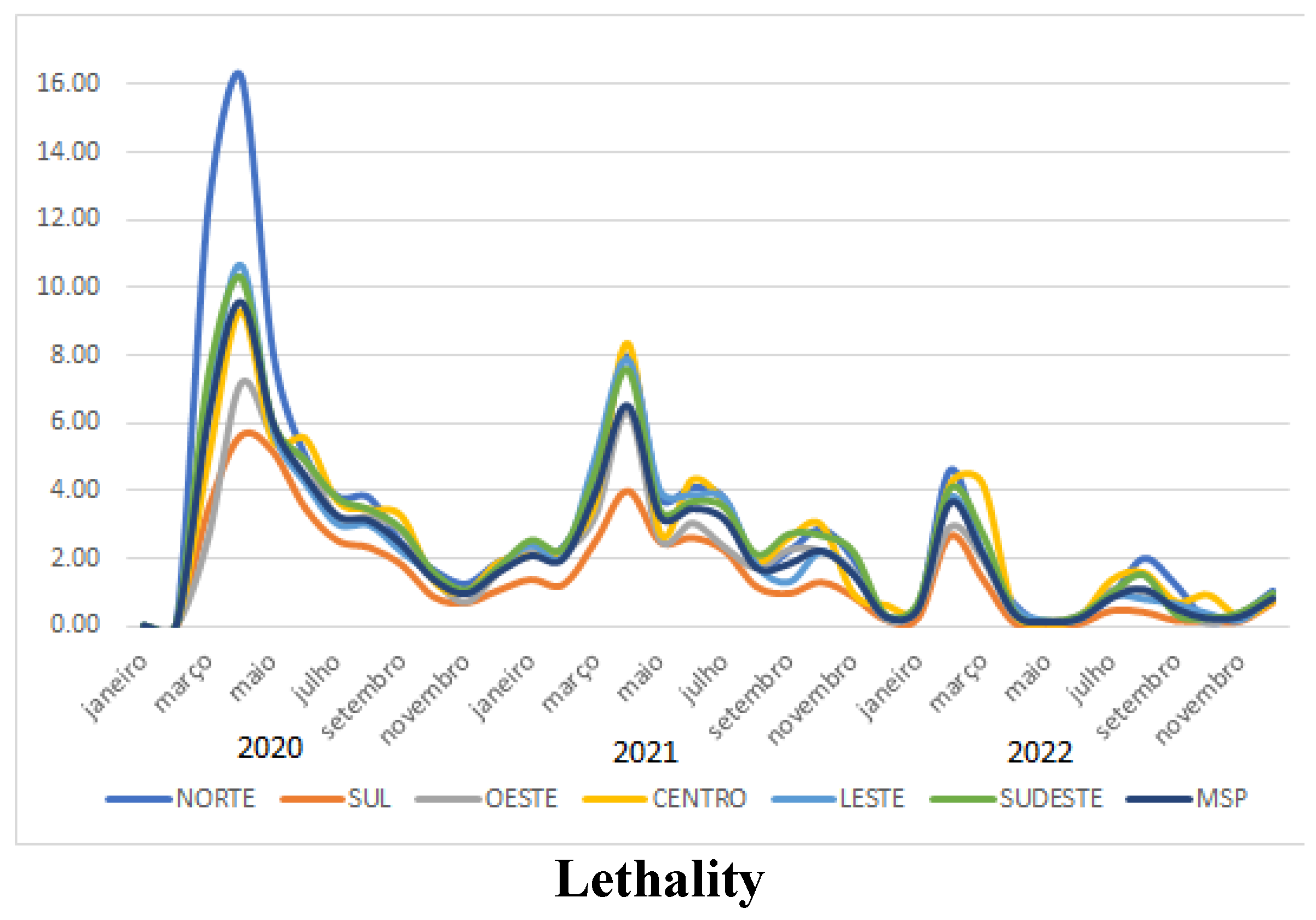

The temporal analysis of incidence, mortality and lethality rates for each CRS shows that all regions presented the same epidemic peaks, with discreet changes in relation to the regional health coordinators.

Regarding incidence, there is a slight difference in incidence in the Central CRS, which is higher at the beginning of the pandemic. The Southern CRS has a higher incidence in the months between January 2021 and January 2022. The Southeast CRS has an increase in incidence different from the other regions in November 2020 and a plateau that extends until January 2021, and in June 2022 and November 2022 it has higher incidence peaks than the other regions.

Regarding the mortality rate, all regions present the same patterns of curves and epidemic peaks. However, the region that stands out the most is the CRS Sudeste, leading almost the entire period with the highest mortality rate.

In the analysis of Lethality, it is observed that the CRS Norte presented a greater discrepancy at the beginning of the pandemic in April 2020 (16.31%), decreasing significantly over the period, followed by the East region (10.65%) and Southeast (10.32%).

Figure 2.

Temporal trend of Incidence Rates and Mortality Rate per 100,000 inhabitants and Lethality per 100 cases in all health regions of the city of São Paulo in the period from January 2020 to December 2022.

Figure 2.

Temporal trend of Incidence Rates and Mortality Rate per 100,000 inhabitants and Lethality per 100 cases in all health regions of the city of São Paulo in the period from January 2020 to December 2022.

Prais-Winsten and Dayly Regression Estimates Percent Chance (DPC) trend in Lethality, Incidence and Mortality of COVID-19, in the City of São Paulo

The results obtained through the lethality trend demonstrated that the regions of the North, South, East and Southeast coordinations presented similar trends in the Total period (2020 to 2022). However, in the CRS Oeste there was a difference in the periods 2021 and 2022, in which it presented a stationary trend. And in the CRS Central, in the year 2021, this trend was increasing.

Regarding mortality, the regions of the North and West coordination offices showed decreasing trends throughout the period analyzed. This differed from the South, East and Southeast regions, which showed decreasing trends throughout the period, except in 2020, when the trend was stationary.

The incidence trend was the one that showed differences in each region, when compared to the general period (2020 to 2022), mainly in the West and Central regions, where this trend remained increasing, while for the North, South, East and Southeast regions the trend was stationary. In the period of 2022, the incidence trend decreased for the North, South and Central regions and was stationary for the East, Southeast and West regions.

Table 3.

Prais-Winsten and Dayly regression estimates Percent Chance (DPC) of COVID-19 lethality, incidence and mortality trends, according to the health regions (General, North, South and West) of the city of São Paulo, from 2020 to 2022.

Table 3.

Prais-Winsten and Dayly regression estimates Percent Chance (DPC) of COVID-19 lethality, incidence and mortality trends, according to the health regions (General, North, South and West) of the city of São Paulo, from 2020 to 2022.

| Periods |

DPC (95% CI) Lethality |

p |

Lethality Trend |

DPC (95% CI) Mortality |

p |

Mortality Trend |

CPD (95% CI) Incidence |

p |

Incidence Trend |

| General |

| Total Period |

-0.25 (-0.31 : -0.18) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.40 (-0.52 : -0.29) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

0.03 (-0.23 : 0.29) |

0.821 |

Stationary |

| 2020 |

-0.56 (-0.75 : -0.38) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

1.29 (-0.24 : 2.83) |

0.098 |

Stationary |

1.15 (0.52 : 1.78) |

<0.001 |

Growing |

| 2021 |

-0.49 (-0.74 : -0.24) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.99 (-1.24 : -0.75) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.47 (-0.66 : -0.28) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

| 2022 |

0.02 (-0.35 : 0.38) |

0.93 |

Stationary |

-0.27 (-0.69 : 0.16) |

0.214 |

Stationary |

-0.76 (-1.73 : 0.22) |

0.127 |

Stationary |

| North |

| Total Period |

-0.14 (-0.20 : -0.09) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.30 (-0.36 : -0.25) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

0.14 (-0.10 : 0.37) |

0.254 |

Stationary |

| 2020 |

-0.93 (-1.03 : -0.82) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.38 (-0.59 : -0.17) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

1.48 (1.06 : 1.91) |

<0.001 |

Growing |

| 2021 |

-0.37 (-0.52 : -0.21) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.93 (-1.10 : -0.75) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.49 (-0.66 : -0.31) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

| 2022 |

0.16 (-0.21 : 0.54) |

0.383 |

Stationary |

-0.21 (-0.39 : -0.04) |

0.016 |

Descending |

-1.31 (-2.50 : -0.10) |

0.033 |

Descending |

| South |

| Total Period |

-0.18 (-0.22 : -0.13) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.25 (-0.30 : -0.19) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

0.16 (-0.17 : 0.49) |

0.347 |

Stationary |

| 2020 |

-0.81 (-0.91 : -0.71) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.23 (-0.49 : 0.04) |

0.092 |

Stationary |

1.50 (0.89 : 2.11) |

<0.001 |

Growing |

| 2021 |

-0.37 (-0.52 : -0.22) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.87 (-1.06 : -0.69) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.46 (-0.63 : -0.30) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

| 2022 |

0.10 (-0.28 : 0.47) |

0.613 |

Stationary |

-0.25 (-0.41 : -0.09) |

0.002 |

Descending |

-1.46 (-2.69 : -0.22) |

0.021 |

Descending |

| West |

| Total Period |

-0.10 (-0.14 : -0.06) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.16 (-0.20 : -0.13) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

0.36 (0.07 : 0.64) |

0.014 |

Growing |

| 2020 |

-0.69 (-0.80 : -0.57) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.32 (-0.47 : -0.17) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

1.61 (1.14 : 2.09) |

<0.001 |

Growing |

| 2021 |

-0.06 (-0.18 : 0.06) |

0.333 |

Stationary |

-0.60 (-0.71 : -0.48) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.41 (-0.61 : -0.20) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

| 2022 |

0.16 (-0.17 : 0.49) |

0.344 |

Stationary |

-0.20 (-0.34 : -0.06) |

0.006 |

Descending |

-0.87 (-1.75 : 0.01) |

0.053 |

Stationary |

Table 4.

Prais-Winsten and Dayly regression estimates Percent Chance (DPC) of COVID-19 lethality, incidence and mortality trends, according to the health regions (Center, Southeast and East) of the city of São Paulo, from 2020 to 2022 (continued).

Table 4.

Prais-Winsten and Dayly regression estimates Percent Chance (DPC) of COVID-19 lethality, incidence and mortality trends, according to the health regions (Center, Southeast and East) of the city of São Paulo, from 2020 to 2022 (continued).

| Periods |

DPC (95% CI) Lethality |

p |

Lethality Trend |

DPC (95% CI) Mortality |

p |

Mortality Trend |

CPD (95% CI) Incidence |

p |

Incidence Trend |

| Center |

| Total Period |

-0.04 (-0.08 : 0.01) |

0.099 |

Stationary |

-0.10 (-0.13 : -0.07) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

0.26 (0.07 : 0.45) |

0.006 |

Growing |

| 2020 |

-0.63 (-0.74 : -0.51) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.30 (-0.42 : -0.19) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

1.36 (0.99 : 1.74) |

<0.001 |

Growing |

| 2021 |

0.16 (0.01 : 0.32) |

0.039 |

Growing |

-0.36 (-0.47 : -0.24) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.47 (-0.62 : -0.32) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

| 2022 |

0.09 (-0.27 : 0.45) |

0.61 |

Stationary |

-0.14 (-0.23 : -0.06) |

0.001 |

Descending |

-0.69 (-1.36 : -0.01) |

0.048 |

Descending |

| East |

| Total Period |

-0.14 (-0.19 : -0.09) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.28 (-0.33 : -0.22) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

0.08 (-0.13 : 0.29) |

0.481 |

Stationary |

| 2020 |

-0.81 (-0.91 : -0.71) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.27 (-0.54 : 0.00) |

0.052 |

Stationary |

1.31 (0.75 : 1.87) |

<0.001 |

Growing |

| 2021 |

-0.38 (-0.53 : -0.23) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-1.02 (-1.19 : -0.84) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.58 (-0.72 : -0.44) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

| 2022 |

-0.04 (-0.37 : 0.29) |

0.803 |

Stationary |

-0.25 (-0.42 : -0.09) |

0.003 |

Descending |

-0.58 (-1.40 : 0.25) |

0.167 |

Stationary |

| Southeast |

| Total Period |

-0.19 (-0.24 : -0.14) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.31 (-0.37 : -0.26) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

0.03 (-0.20 : 0.25) |

0.806 |

Stationary |

| 2020 |

-0.74 (-0.86 : -0.62) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.17 (-0.41 : 0.08) |

0.174 |

Stationary |

1.19 (0.66 : 1.73) |

<0.001 |

Growing |

| 2021 |

-0.37 (-0.52 : -0.23) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.93 (-1.08 : -0.79) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

-0.49 (-0.70 : -0.28) |

<0.001 |

Descending |

| 2022 |

0.01 (-0.29 : 0.30) |

0.963 |

Stationary |

-0.26 (-0.47 : -0.06) |

0.011 |

Descending |

-0.65 (-1.59 : 0.30) |

0.176 |

Stationary |

4. Discussion

Brazil only recognized the first case of coronavirus on February 26, 2020, in the metropolitan region of São Paulo. From that moment on, health organizations began very slowly to initiate strategies to contain the virus, still facing a very divergent scenario with the federal government regarding the continuation of the distancing, quarantine and lockdown protocols.

Lethality

In many global cities, especially the larger ones, there are different levels of socioeconomic inequality. In the American city of New York, a delay in social isolation measures led to a steep increase in cases, with significant social impacts on the poorest sections of the population[

18].

In this scenario, all regions of the city of SP showed an accelerated growth in lethality, reaching in April 2020, the highest lethality in the entire period (2020-2022). At this time, the epicenter of COVID-19 was the city of São Paulo[

18].

The North CRS had the highest lethality rate in 2020 (2.80%). With emphasis on the month of April, where the lethality rate was 16.3%, followed by the East (10.6%), Southeast (10.32%), Center (9.3%), and West (7.15%) regions. However, after this period, all regions showed another peak in lethality in April 2021. However, when compared to the other regions of the city of SP, the North CRS showed a significant decrease in lethality (7.98%), configuring itself as the region with the greatest decreasing trend (DPC - 0.93; p < 0.001).

When analyzing the trend in the periods of 2020 before vaccination and 2021 with the beginning of vaccination, it is observed that, except for the CRS Centro, the lethality was decreasing for all CRS in the city of São Paulo, showing a significant decrease in the daily percentage variation, demonstrating that vaccination had an effect on reducing the lethality. It is assumed that with the advent of vaccination there was a gradual return to work activities, increasing the flow of people to the Central region. In metropolitan areas such as São Paulo, there is a shift of the population from peripheral areas to the central region with greater job offers, resulting in greater exposure of this population and an increasing trend for the year 2021. However, with the increase in vaccination coverage, a change in this trend to a decreasing trend can be observed in the year 2022.

Despite following the same trend pattern in the years recorded, the CRS Sul was the region that presented the lowest fatalities throughout the period. This result corroborates a study carried out at the beginning of the pandemic that highlighted the West and South zones of the city with the lowest number of deaths, while the majority of deaths were concentrated in the North and East zones[

19].

It is important to highlight that the spatial-temporal differences in COVID-19 lethality between Brazilian states may reflect social, economic, cultural and structural inequalities[

20]; however, the spatial heterogeneity of the subdivisions of the regional health coordinators does not allow us to measure the difference between the regions.

Mortality

Spatial analyses carried out in 2020 detected spatial patterns and critical points of the pandemic for this year[

21]. In our study, we can observe that the highest mortality rates occurred in May 2020, and even higher in March and April 2021, when the curve reached its peak for all regions. It is important to highlight that the increase in vaccination was just beginning, and while other countries already had considerable portions of their population vaccinated, starting vaccination in December 2020, Brazil was still facing the worst pandemic scenarios in 2021.

The partial adherence to social isolation observed in São Paulo can still be considered as a factor that may have contributed to the increase in cases[

5]. Research predicted a collapse of the health system in a second wave, with the Omicrom variant[

22].

In February 2021, Brazil reached its lowest level of social isolation in a year (32.2%). On March 2, 2021, data from the São Paulo state government stated that the state had recorded a collapse in its health system and the highest number of deaths in 24 hours, 60,000 deaths from COVID-19. This catastrophe reached the world's media to such an extent that two of the most influential newspapers on the planet — the British "The Guardian" and the American "The New York Times" — addressed the Brazilian tragedy with COVID-19 and positioned the country as a “global health threat”. By that date, 18 countries had suspended flights or established restrictions on passengers leaving Brazil, for fear of the spread of the new coronavirus and its variants. For the City of São Paulo, the death data showed the highest number of deaths in 24 hours, on March 26, 2021, with 337 deaths. This data is even more alarming, especially in the Southeast CRS, responsible for 100 deaths on this date.

Still considering the month of March 2021, for the CRS Leste of the city of São Paulo, it was the worst month in the entire study period, presenting 15.86% of relative frequency of confirmed deaths. Which was configured with the greatest negative daily percentage variation for this region relative to the year 2021 (DPC -1.02; p<0.001).

Studies[

23,

24,

25] suggest that social disparities and worsening indicators may reflect a combination of factors that result in greater vulnerability to exposure to the virus and, consequently, an increase in mortality rates. Examples include household crowding, underlying medical conditions, occupation and means of transportation, and commuting time to work. Our study assumes that these variables can directly influence mortality rates; however, more specific studies should be carried out to assist in the formulation of public policies and guidance for local managers. According to the 2020 Map of Inequality in the City of São Paulo, the two districts with the highest number of deaths from COVID-19 have a percentage of households in favelas 3 times higher than the city average. Brasilândia (CRS Norte) and Sacomã (CRS SE) have 30% and 28% of their households in favelas. Together, they account for more than 500 deaths.

The month of March 2021 therefore presented the highest peak in mortality in all regions and from this month onwards there was a significant decrease in mortality which may be directly related to the increase in vaccination. Thus, the high number of deaths and the collapse of the health system in 2021 could have been avoided if the country had prepared correctly and anticipated the acquisition of vaccines.

Prains trend analysis Wintein[

16] observed that the CRS regions showed a decreasing trend (p<0.001) for the years 2021 and 2022

Incidence

Regarding the incidence trend analysis, we can observe that in 2020 all regions of the city of São Paulo showed an increasing trend (p<0.001) and in 2021 the trend was decreasing (p<0.001). This scenario may be related to the increase in vaccination for this year. However, for the year 2022, we can observe differences in that for the North, South and Center regions of the city of São Paulo there is a decreasing trend, unlike the East, Southeast and West regions where the trend was stationary.

By analyzing the incidence graphs of the regions, it is also possible to visualize the importance of social isolation and lockdown , which kept the curves and peaks more attenuated. The fact is that from 2022 onwards, the incidence starts to have higher peaks. This becomes more evident when viewed from a monthly perspective. We can see that in all regions, the incidence curves remained similar. While the state maintained lockdown policies, the curves were more attenuated. While after vaccination, with the release of distancing policies in 2022, the curves reached high rates with more frequent epidemic peaks, during the years, as observed in 2022, with peaks in the months of January, June, and November, presenting gradually smaller epidemic peaks. This can also be demonstrated by the greater daily percentage variation in the incidence rate that occurred in 2020 and 2022 for all regions.

Our results do not allow us to analyze the effect of specific incidence in the vaccinated population, however we can observe that vaccination considerably reduced mortality and lethality in the population studied. Studies carried out after one year of vaccination also demonstrated a reduction in the incidence of infection and severe COVID-19 after vaccination, particularly among those clinically vulnerable to severe COVID-19[

26,

27] . Our study suggests the importance of booster doses in order to reduce the epidemic peaks found in the months of 2022.

Still in this monthly perspective, we can observe that the first peak of incidence occurred in May 2020 for the West, Center and North regions, demonstrating that it possibly began in these regions and later reached the Southeast, East and South CRS[

18]. also observed this change in incidence patterns in which they detected that at the beginning of the pandemic the most affected urban patterns were what they classified as A, B, C and explained that this scenario occurred because COVID-19 arrived in São Paulo through travelers who had been to Italy.

These results suggest that the spread of COVID-19 in São Paulo may have followed the expected pattern, in which regions with poor urban structures in the city were proportionally more affected by the disease[

18]. However, the number of deaths and lethality rates were higher for the different urban patterns with greater vulnerability. In our study, this pattern can also be observed, with a higher lethality rate in the North, East, and Southeast regions[

28].

Still in the monthly distribution of cases, we can observe that, for all regions, the worst month with the highest number of confirmed cases was January 2022, in which the city of São Paulo had 212,931 confirmed cases (10.71% of the relative frequency), with January 10th having 16,092 confirmed cases. However, what can be observed in the temporal trend is that although January 2022 was the month with the highest incidence and prevalence of cases, the lethality and mortality rates were low when compared to what occurred in March 2021. This can possibly be explained by the increase in vaccination, demonstrating that although people became infected with the Sars CoV-2 virus, they did not present the severe form of the disease that could lead to death[

29].

In general, we observed that all regions presented subtle differences in relation to the period studied. In fact, in contrast to the divisions of the regional health coordinators that exist today, the municipality of São Paulo is clearly a group of “cities” with very different vulnerabilities in response to external factors. Statistically distinguishing groups of urban patterns in the city that allow a different view of the political-administrative (districts) that are artificial divisions and do not allow us to glimpse specific details of the vulnerability related to the spread of the COVID-19 disease[

18,

29].

According to the UNDP Program, the city of São Paulo has enormous internal inequality, the worst indicators are found in the Southern CRS and the extremes of the Eastern CRS, in the South zone also concentrates 21.3% of residents in substandard agglomerations (favelas), while the most central areas and areas contiguous to the North, West and Southeast have the best Human Development Index. Regarding income, 5.6% of the inhabitants of the Western CRS receive more than 20 minimum wages per month. The Southeast CRS presents intermediate data between the extremes of the Eastern, Central and Western CRS, in which a large part of the population receives up to two minimum wages[

30,

31].

To identify vulnerability patterns, we should check the trend in each region specifically in order to have a more in-depth look at how the spread of COVID-19 occurred in each scenario in the city of São Paulo. To this end, more studies should be carried out with a more specific look at each territory.

5. Conclusions

The city of São Paulo, in general, presented a strong spatial interdependence when analyzing the grouped concentrations of incidence and mortality due to COVID-19. When comparing the differences between the Regional Health Coordinators, it was observed that the CRS Norte presented a greater discrepancy in lethality at the beginning of the pandemic, decreasing significantly over the period. And the CRS Central, in 2021, showed an increasing trend different from the other regions. Regarding mortality, the CRS Norte, Centro and Oeste presented a decreasing trend for all periods analyzed (2020, 2021 and 2022), different from the CRS Leste, Sudeste and Sul which in 2020 presented a stationary trend. Demonstrating that territorial disparities, determined by the subdivisions by Regional Health Coordinators, demonstrate unequal impacts and we found a relationship between the effects of COVID-19 related to sociodemographic characteristics, demonstrating that vulnerable groups are most affected by the pandemic . We highlight that vaccination has had an effect on reducing lethality and mortality. Analyzing the incidence graphs of the regions also shows the importance of social isolation and lockdown, which kept the curves and peaks more attenuated.

References

- Ministério da Saúde. Coronavírus Brasil [Internet]. covid.saude.gov.br. 2024. Available from: https://covid.saude.gov.br/.

- BRASIL. CONSTITUIÇÃO DA REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL DE 1988 [Internet]. Planalto.gov.br. 1988. Available from: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm.

- Worldometer. Coronavirus Update (Live): 69,290 Cases and 1,671 Deaths from COVID-19 Wuhan China Virus Outbreak - Worldometer [Internet]. www.worldometers.info. 2022. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/#countries.

- Silva SA da. A Pandemia de Covid-19 no Brasil : a pobreza e a vulnerabilidade social como determinantes sociais. Confins. 2021 Nov 12;(52).

- Lorenz C, Ferreira PM, Masuda ET, Lucas PC de C, Palasio RGS, Nielsen L, et al. COVID-19 no estado de São Paulo: a evolução de uma pandemia. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia [Internet]. 2021;24. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbepid/a/scMYQN96Dx5nJzNmRrDFYTM/?lang=pt&format=pdf.

- IBGE Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística Censo demográfico. Prévia da População dos Municípios com base nos dados do Censo Demográfico 2022 [Internet]. [cited 2023 May 1]. Available from: https://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Censos/Censo_Demografico_2022/Previa_da_Populacao/POP2022_Municipios.pdf.

- Rede Nova São Paulo. Início [Internet]. Rede Nossa São Paulo. 2022. Available from: https://www.nossasaopaulo.org.br/.

- Vanessa B. Opinion | There’s a Menace Hanging Over Brazil. The New York Times [Internet]. 2023 Mar 6; Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/06/opinion/brazil-military-bolsonaro.html.

- Associação Brasileira de Saúde Coletiva (ABRASCO). PLANO NACIONAL DE ENFRENTAMENTO À PANDEMIA DA COVID-19 [Internet]. 2020. Available from: https://frentepelavida.org.br/uploads/documentos/PEP-COVID-19_v3_01_12_20.pdf.

- Bógus LMM, Magalhães LFA. DESIGUALDADES SOCIAIS E ESPACIALIDADES DA COVID-19 EM REGIÕES METROPOLITANAS. Caderno CRH [Internet]. 2022 Dec 16;35:e022033. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/ccrh/a/8KZPyqRMyGKbzNMcPwWVXyJ/.

- OLIVEIRA K. Estimativa dos anos de vida potencialmente perdidos devido ao impacto da Covid-19 no Brasil. 2021.

- TabNet Win32 3.0: COVID19 e-SUS-VE Síndrome Gripal (SG) [Internet]. Sp.gov.br. 2024 [cited 2024 Sep 16]. Available from: http://tabnet.saude.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/cgi/deftohtm3.exe?secretarias/saude/TABNET/RCOVID19/covid19.def.

- Evolução Populacional (MSP) | Seade População [Internet]. Seade População. 2023 [cited 2024 Sep 16]. Available from: https://populacao.seade.gov.br/evolucao-populacional-msp.

- PREFEITURA DO MUNICÍPIO DE SÃO PAULO SECRETARIA MUNICIPAL DA SAÚDE RELATÓRIO ANUAL DE GESTÃO 2020 AÇÕES PREVISTAS E EXECUTADAS [Internet]. Available from: https://www.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/cidade/secretarias/upload/saude/Relatorio_Anual_Gestao_2020_enviado.pdf.

- Antunes JLF, Cardoso MRA. Uso da análise de séries temporais em estudos epidemiológicos. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde [Internet]. 2015 Sep;24(3):565–76. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/pdf/ress/v24n3/2237-9622-ress-24-03-00565.pdf.

- PRAIS SJ, WINSTEN CB. Trend estimators and serial correlation. Chicago: Cowles Commission discussion paper. 1954;

- Zeng W, Zhang Y, Wang L, Wei Y, Lu R, Xia J, et al. Ambient fine particulate pollution and daily morbidity of stroke in Chengdu, China. Chen Y, editor. PLOS ONE. 2018 Nov 6;13(11):e0206836. [CrossRef]

- Jardim VC, Buckeridge MS, Jardim VC, Buckeridge MS. Análise sistêmica do município de São Paulo e suas implicações para o avanço dos casos de Covid-19. Estudos Avançados [Internet]. 2020 Aug 1;34(99):157–74. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0103-40142020000200157&script=sci_arttext&tlng=pt.

- Sonia A. COVID-19: A DOENÇA DOS ESPAÇOS DE FLUXOS GEOgraphia Niterói, Universidade Federal Fluminense. 2020;vol: 22, n. 48.

- Souza CDF de, Paiva JPS de, Leal TC, Silva LF da, Santos LG, Souza CDF de, et al. Evolução espaçotemporal da letalidade por COVID-19 no Brasil, 2020. Jornal Brasileiro de Pneumologia [Internet]. 2020;46(4). Available from: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1806-37132020000401001&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt.

- Rex FE, Borges CA de S, Käfer PS, Rex FE, Borges CA de S, Käfer PS. Spatial analysis of the COVID-19 distribution pattern in São Paulo State, Brazil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva [Internet]. 2020 Sep 1;25(9):3377–84. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S1413-81232020000903377&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en.

- Lana RM, Coelho FC, Gomes MF da C, Cruz OG, Bastos LS, Villela DAM, et al. Emergência do novo coronavírus (SARS-CoV-2) e o papel de uma vigilância nacional em saúde oportuna e efetiva. Cadernos de Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2020 Mar 13;36(3):e00019620. Available from: https://www.scielosp.org/article/csp/2020.v36n3/e00019620/pt/.

- Ribeiro KB, Ribeiro AF, de Sousa Mascena Veras MA, de Castro MC. Social inequalities and COVID-19 mortality in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2021 Feb 28; [CrossRef]

- Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, et al. OpenSAFELY: factors associated with COVID-19 death in 17 million patients. Nature. 2020 Jul 8;584(7821):430–6. [CrossRef]

- Blundell R, Dias MC, Joyce R, Xu X. Covid-19 and Inequalities. Fiscal Studies. 2020 Jun 27;41(2):291–319. [CrossRef]

- Watson OJ, Barnsley G, Toor J, Hogan AB, Winskill P, Ghani AC. Global impact of the first year of COVID-19 vaccination: a mathematical modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2022 Jun 23;22(9):1293–302. [CrossRef]

- Wells CR, Galvani AP. The global impact of disproportionate vaccination coverage on COVID-19 mortality. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2022 Jun; [CrossRef]

- Souto LRF, Travassos C. Plano Nacional de Enfrentamento à Pandemia da Covid-19: construindo uma autoridade sanitária democrática. Saúde em Debate. 2020 Sep;44(126):587–9. [CrossRef]

- Nogueira D. Determinantes Sociais da Vulnerabilidade à Covid-19: Proposta de um Esquema Teórico 1 -Parte I [Internet]. Available from: https://acoescovid19.unifesspa.edu.br/images/Artigo_-_Parte_1_-_Daniel_-_24_de_maio.pdf.

- Censo 2000 | IBGE [Internet]. www.ibge.gov.br. Available from: https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/administracao-publica-e-participacao-politica/9663-censo-demografico-2000.html.

- Brasil, Cidade de São Paulo. Plano Municipal de Saúde - PMS 2022-2025 [Internet]. 2023. Available from: https://docs.bvsalud.org/biblioref/2021/10/1342035/plano_municipal_de_saude_2021_compressed.pdf.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).