Submitted:

23 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

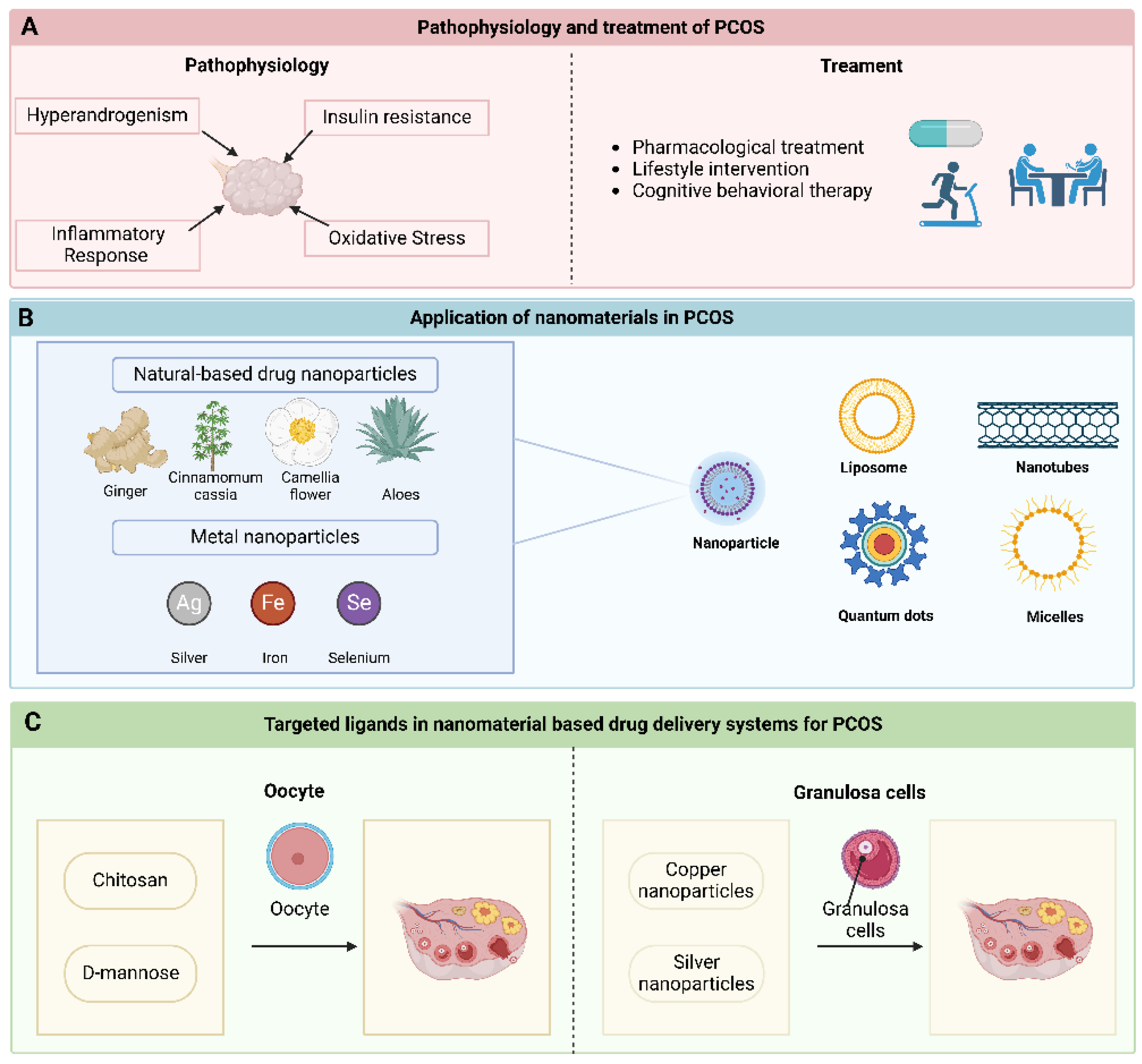

2. The Pathophysiology of PCOS

2.1. Hyperandrogenism

2.2. IR

2.3. Inflammatory Response and Oxidative Stress

3. Diagnosis and Treatment of PCOS

3.1. Diagnosis of PCOS

3.2. Treatment of PCOS

4. Nanomaterials in PCOS Treatment

4.1. Nanoparticle

4.1.1. Natural-Based Drug Nanoparticles

4.1.2. Metal Nanoparticles

4.2. Liposome

4.3. Nanotubes

4.4. Quantum Dots

4.5. Micelles

5. Targeted Ligands in Nanomaterial-Based Drug Delivery Systems for PCOS

5.1. Oocyte

5.2. Granulosa Cells

6. Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xing:, L. : Xu, J.; Wei, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhuang, H.; Tang, W.; Yu, S.; Zhang, J.; Yin, G.; Wang, R.; et al. Depression in polycystic ovary syndrome: Focusing on pathogenesis and treatment. Front Psychiatry 2022, 13, 1001484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.E.; Daley, D.; Tarta, C.; Stanciu, P.I. Risk of endometrial cancer in patients with polycystic ovarian syndrome: A meta-analysis. Oncol Lett 2023, 25, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, F.; Wu, P.; Heald, A.; Fryer, A. Diabetes detection in women with gestational diabetes and polycystic ovarian syndrome. Bmj 2023, 382, e071675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, G.; Badeghiesh, A.; Suarthana, E.; Baghlaf, H.; Dahan, M.H. Polycystic ovary syndrome as an independent risk factor for gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a population-based study on 9.1 million pregnancies. Hum Reprod 2020, 35, 1666–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.J.; Tay, C.T.; Laven, J.; Dokras, A.; Moran, L.J.; Piltonen, T.T.; Costello, M.F.; Boivin, J.; Redman, L.M.; Boyle, J.A.; et al. Recommendations from the 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome†. Hum Reprod 2023, 38, 1655–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riestenberg, C.; Jagasia, A.; Markovic, D.; Buyalos, R.P.; Azziz, R. Health Care-Related Economic Burden of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in the United States: Pregnancy-Related and Long-Term Health Consequences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022, 107, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Delau, O.; Bonner, A.J.; Markovic, D.; Patterson, W.; Ottey, S.; Buyalos, R.P.; Azziz, R. Direct economic burden of mental health disorders associated with polycystic ovary syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Elife 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melin, J.; Forslund, M.; Alesi, S.; Piltonen, T.; Romualdi, D.; Spritzer, P.M.; Tay, C.T.; Pena, A.; Witchel, S.F.; Mousa, A.; et al. The impact of metformin with or without lifestyle modification versus placebo on polycystic ovary syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Endocrinol 2023, 189, S37–s63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseka, S.; Wijeyaratne, C.N.; Gawarammana, I.B.; Kalupahana, N.S.; Rosairo, S.; Ratnatunga, N.; Kumarasiri, R. Effectiveness of Low-dose Ethinylestradiol/Cyproterone Acetate and Ethinylestradiol/Desogestrel with and without Metformin on Hirsutism in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Randomized, Double-blind, Triple-dummy Study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2020, 13, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Teede, H.J.; Tay, C.T.; Laven, J.; Dokras, A.; Moran, L.J.; Piltonen, T.T.; Costello, M.F.; Boivin, J.; L, M.R.; J, A.B.; et al. Recommendations from the 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Fertil Steril 2023, 120, 767–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Pascual, A.M.; Rahdar, A. Functional Nanomaterials in Biomedicine: Current Uses and Potential Applications. ChemMedChem 2022, 17, e202200142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, S.; Gao, Z.; Ding, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, Z.; Jin, W.; Qu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Guo, D.; et al. Nanocomposites based on nanoceria regulate the immune microenvironment for the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome. J Nanobiotechnology 2023, 21, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, S.; Mateen, S.; Ahmad, R.; Moin, S. A brief insight into the etiology, genetics, and immunology of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS). J Assist Reprod Genet 2022, 39, 2439–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumesic, D.A.; Meldrum, D.R.; Katz-Jaffe, M.G.; Krisher, R.L.; Schoolcraft, W.B. Oocyte environment: follicular fluid and cumulus cells are critical for oocyte health. Fertil Steril 2015, 103, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade, V.H.; Mata, A.M.; Borges, R.S.; Costa-Silva, D.R.; Martins, L.M.; Ferreira, P.M.; Cunha-Nunes, L.C.; Silva, B.B. Current aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome: A literature review. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992) 2016, 62, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson-Degrave, V.L.; Wickenheisser, J.K.; Hendricks, K.L.; Asano, T.; Fujishiro, M.; Legro, R.S.; Kimball, S.R.; Strauss, J.F., 3rd; McAllister, J.M. Alterations in mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase and extracellular regulated kinase signaling in theca cells contribute to excessive androgen production in polycystic ovary syndrome. Mol Endocrinol 2005, 19, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willis, D.; Mason, H.; Gilling-Smith, C.; Franks, S. Modulation by insulin of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone actions in human granulosa cells of normal and polycystic ovaries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996, 81, 302–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, B.B.; Lopes-Costa, P.V.; Rosal, M.A.; Pires, C.G.; dos Santos, L.G.; Gontijo, J.A.; Alencar, A.P.; de Jesus Simões, M. Morphological and morphometric analysis of the adrenal cortex of androgenized female rats. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2007, 64, 44–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S. Relationship between early follicular serum estrone level and other hormonal or ultrasonographic parameters in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol 2020, 36, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumariya, S.; Ubba, V.; Jha, R.K.; Gayen, J.R. Autophagy in ovary and polycystic ovary syndrome: role, dispute and future perspective. Autophagy 2021, 17, 2706–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, V.; Verduci, E.; Cena, H.; Magenes, V.C.; Todisco, C.F.; Tenuta, E.; Gregorio, C.; De Giuseppe, R.; Bosetti, A.; Di Profio, E.; et al. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome in Insulin-Resistant Adolescents with Obesity: The Role of Nutrition Therapy and Food Supplements as a Strategy to Protect Fertility. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Garrido, M.A.; Tena-Sempere, M. Metabolic dysfunction in polycystic ovary syndrome: Pathogenic role of androgen excess and potential therapeutic strategies. Mol Metab 2020, 35, 100937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCartney, C.R.; Campbell, R.E.; Marshall, J.C.; Moenter, S.M. The role of gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Neuroendocrinol 2022, 34, e13093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomba, S.; Piltonen, T.T.; Giudice, L.C. Endometrial function in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: a comprehensive review. Hum Reprod Update 2021, 27, 584–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, E.; Mbanya, A.; Kemfang-Ngowa, J.D.; Dohbit, S.; Tchana-Sinou, M.; Foumane, P.; Donfack, O.T.; Doh, A.S.; Mbanya, J.C.; Sobngwi, E. The Relationship between Adiposity and Insulin Sensitivity in African Women Living with the Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: A Clamp Study. Int J Endocrinol 2016, 2016, 9201701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E. Polycystic ovarian syndrome: pathophysiology, molecular aspects and clinical implications. Expert Rev Mol Med 2008, 10, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, H.G. Androgen production in women. Fertil Steril 2002, 77 Suppl 4, S3–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsilchorozidou, T.; Honour, J.W.; Conway, G.S. Altered cortisol metabolism in polycystic ovary syndrome: insulin enhances 5alpha-reduction but not the elevated adrenal steroid production rates. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003, 88, 5907–5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghetti, P.; Tosi, F.; Bonin, C.; Di Sarra, D.; Fiers, T.; Kaufman, J.M.; Giagulli, V.A.; Signori, C.; Zambotti, F.; Dall'Alda, M.; et al. Divergences in insulin resistance between the different phenotypes of the polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013, 98, E628–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armanini, D.; Andrisani, A.; Bordin, L.; Sabbadin, C. Spironolactone in the treatment of polycystic ovary syndrome. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2016, 17, 1713–1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ROOT, H.F. Insulin Resistance and Bronze Diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine 1929, 201, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghetti, P.; Tosi, F. Insulin resistance and PCOS: chicken or egg? J Endocrinol Invest 2021, 44, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunaif, A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome: mechanism and implications for pathogenesis. Endocr Rev 1997, 18, 774–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E.; Dunaif, A. Insulin resistance and the polycystic ovary syndrome revisited: an update on mechanisms and implications. Endocr Rev 2012, 33, 981–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nestler, J.E.; Jakubowicz, D.J.; de Vargas, A.F.; Brik, C.; Quintero, N.; Medina, F. Insulin stimulates testosterone biosynthesis by human thecal cells from women with polycystic ovary syndrome by activating its own receptor and using inositolglycan mediators as the signal transduction system. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998, 83, 2001–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, Y.L.; Liang, X.Y.; Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Wei, L.N. Low-grade chronic inflammation in the peripheral blood and ovaries of women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2011, 159, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulman, N.; Levy, Y.; Leiba, R.; Shachar, S.; Linn, R.; Zinder, O.; Blumenfeld, Z. Increased C-reactive protein levels in the polycystic ovary syndrome: a marker of cardiovascular disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004, 89, 2160–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudnicka, E.; Kunicki, M.; Suchta, K.; Machura, P.; Grymowicz, M.; Smolarczyk, R. Inflammatory Markers in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Biomed Res Int 2020, 2020, 4092470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, C.C.; Lyall, H.; Petrie, J.R.; Gould, G.W.; Connell, J.M.; Sattar, N. Low grade chronic inflammation in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001, 86, 2453–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awonuga, A.O.; Camp, O.G.; Abu-Soud, H.M. A review of nitric oxide and oxidative stress in typical ovulatory women and in the pathogenesis of ovulatory dysfunction in PCOS. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2023, 21, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immediata, V.; Ronchetti, C.; Spadaro, D.; Cirillo, F.; Levi-Setti, P.E. Oxidative Stress and Human Ovarian Response-From Somatic Ovarian Cells to Oocytes Damage: A Clinical Comprehensive Narrative Review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.Y.; Wang, D.H.; Zou, X.Y.; Xu, C.M. Mitochondrial functions on oocytes and preimplantation embryos. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B 2009, 10, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaeib, F.; Khan, S.N.; Ali, I.; Thakur, M.; Saed, M.G.; Dai, J.; Awonuga, A.O.; Banerjee, J.; Abu-Soud, H.M. The Defensive Role of Cumulus Cells Against Reactive Oxygen Species Insult in Metaphase II Mouse Oocytes. Reprod Sci 2016, 23, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, J.; Shaeib, F.; Maitra, D.; Saed, G.M.; Dai, J.; Diamond, M.P.; Abu-Soud, H.M. Peroxynitrite affects the cumulus cell defense of metaphase II mouse oocytes leading to disruption of the spindle structure in vitro. Fertil Steril 2013, 100, 578–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, F.; Rote, N.S.; Minium, J.; Kirwan, J.P. Reactive oxygen species-induced oxidative stress in the development of insulin resistance and hyperandrogenism in polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006, 91, 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruegsegger, G.N.; Creo, A.L.; Cortes, T.M.; Dasari, S.; Nair, K.S. Altered mitochondrial function in insulin-deficient and insulin-resistant states. J Clin Invest 2018, 128, 3671–3681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M.T.; Kasper, J.D.; Bazil, J.N.; Frisbee, J.C.; Wiseman, R.W. Quantification of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation in Metabolic Disease: Application to Type 2 Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Zhu, M.; Xu, W. Roles of Oxidative Stress in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Cancers. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2016, 2016, 8589318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, I.F.; Leventhal, M.L. Amenorrhea associated with bilateral polycystic ovaries. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1935, 29, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Hum Reprod 2004, 19, 41–47. [CrossRef]

- Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril 2004, 81, 19–25. [CrossRef]

- Teede, H.J.; Misso, M.L.; Costello, M.F.; Dokras, A.; Laven, J.; Moran, L.; Piltonen, T.; Norman, R.J. Recommendations from the international evidence-based guideline for the assessment and management of polycystic ovary syndrome. Hum Reprod 2018, 33, 1602–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dapas, M.; Lin, F.T.J.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Sisk, R.; Legro, R.S.; Urbanek, M.; Hayes, M.G.; Dunaif, A. Distinct subtypes of polycystic ovary syndrome with novel genetic associations: An unsupervised, phenotypic clustering analysis. PLoS Med 2020, 17, e1003132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moran, L.J.; Norman, R.J.; Teede, H.J. Metabolic risk in PCOS: phenotype and adiposity impact. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2015, 26, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, R.; Yang, S.; Li, R.; Liu, P.; Qiao, J.; Zhang, Y. Effects of hyperandrogenism on metabolic abnormalities in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2016, 14, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Mol, B.W. The Rotterdam criteria for polycystic ovary syndrome: evidence-based criteria? Hum Reprod 2017, 32, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Mortada, R.; Porter, S. Diagnosis and Treatment of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Am Fam Physician 2016, 94, 106–113. [Google Scholar]

- Azziz, R. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Obstet Gynecol 2018, 132, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, K.; Brown, A.J. Secondary amenorrhea: Diagnostic approach and treatment considerations. Nurse Pract 2017, 42, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neven, A.C.H.; Laven, J.; Teede, H.J.; Boyle, J.A. A Summary on Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Diagnostic Criteria, Prevalence, Clinical Manifestations, and Management According to the Latest International Guidelines. Semin Reprod Med 2018, 36, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyritsi, E.M.; Dimitriadis, G.K.; Kyrou, I.; Kaltsas, G.; Randeva, H.S. PCOS remains a diagnosis of exclusion: a concise review of key endocrinopathies to exclude. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2017, 86, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de-Medeiros, S.F.; Yamamoto, M.M.W.; de-Medeiros, M.A.S.; Barbosa, J.S.; Norman, R.J. Should Subclinical Hypothyroidism Be an Exclusion Criterion for the Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome? J Reprod Infertil 2017, 18, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gibson-Helm, M.; Teede, H.; Dunaif, A.; Dokras, A. Delayed Diagnosis and a Lack of Information Associated With Dissatisfaction in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2017, 102, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrmann, D.A. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2005, 352, 1223–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teede, H.J.; Tay, C.T.; Laven, J.J.E.; Dokras, A.; Moran, L.J.; Piltonen, T.T.; Costello, M.F.; Boivin, J.; Redman, L.M.; Boyle, J.A.; et al. Recommendations From the 2023 International Evidence-based Guideline for the Assessment and Management of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2023, 108, 2447–2469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Q.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.J.; Wu, B.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Fan, B. Effects of thiazolidinediones on polycystic ovary syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Adv Ther 2012, 29, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S.; Satish, S. Endophytes: toward a vision in synthesis of nanoparticle for future therapeutic agents. Int. J. Bio-Inorg. Hybd. Nanomat 2012, 1, 67–77. [Google Scholar]

- Jaybhaye, S.V. Antimicrobial activity of silver nanoparticles synthesized from waste vegetable fibers. Materials Today: Proceedings 2015, 2, 4323–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndayishimiye, J.; Kumeria, T.; Popat, A.; Falconer, J.R.; Blaskovich, M.A.T. Nanomaterials: The New Antimicrobial Magic Bullet. ACS Infect Dis 2022, 8, 693–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Li, J.; Mei, Y.; Yin, Y.; Wang, W. Multifunctional inorganic nanomaterials for cancer photoimmunotherapy. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2022, 42, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Ouyang, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, P.; Jin, W.; Qu, S.; Yang, F.; He, Z.; Qin, M. Nanomaterials for Delivering Antibiotics in the Therapy of Pneumonia. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Guo, H.; Lin, Q. Nanomaterials: a promising multimodal theranostics platform for thyroid cancer. J Mater Chem B 2023, 11, 7544–7566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, W.K.; Cheung, S.C.M.; Lau, R.A.W.; Benzie, I.F.F. Bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus L.). In Herbal Medicine: Biomolecular and Clinical Aspects, Benzie, I.F.F., Wachtel-Galor, S., Eds.; CRC Press/Taylor & Francis Copyright © 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC.: Boca Raton (FL), 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Romaiyan, A.; King, A.J.; Persaud, S.J.; Jones, P.M. A novel extract of Gymnema sylvestre improves glucose tolerance in vivo and stimulates insulin secretion and synthesis in vitro. Phytother Res 2013, 27, 1006–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arentz, S.; Abbott, J.A.; Smith, C.A.; Bensoussan, A. Herbal medicine for the management of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and associated oligo/amenorrhoea and hyperandrogenism; a review of the laboratory evidence for effects with corroborative clinical findings. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014, 14, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, T.A.E.A.-S.r.P.C.W. Consensus on women's health aspects of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)†. Human Reproduction 2011, 27, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Lord, J.M.; Norman, R.J.; Yasmin, E.; Balen, A.H. Insulin-sensitising drugs (metformin, rosiglitazone, pioglitazone, D-chiro-inositol) for women with polycystic ovary syndrome, oligo amenorrhoea and subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010, Cd003053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.H.; Rana, S.; Hussain, L.; Asif, M.; Mehmood, M.H.; Imran, I.; Younas, A.; Mahdy, A.; Al-Joufi, F.A.; Abed, S.N. Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: A Disorder of Reproductive Age, Its Pathogenesis, and a Discussion on the Emerging Role of Herbal Remedies. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13, 874914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moini Jazani, A.; Nasimi Doost Azgomi, H.; Nasimi Doost Azgomi, A.; Nasimi Doost Azgomi, R. A comprehensive review of clinical studies with herbal medicine on polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Daru 2019, 27, 863–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharjan, R.; Nagar, P.S.; Nampoothiri, L. Effect of Aloe barbadensis Mill. formulation on Letrozole induced polycystic ovarian syndrome rat model. J Ayurveda Integr Med 2010, 1, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farideh, Z.Z.; Bagher, M.; Ashraf, A.; Akram, A.; Kazem, M. Effects of chamomile extract on biochemical and clinical parameters in a rat model of polycystic ovary syndrome. J Reprod Infertil 2010, 11, 169–174. [Google Scholar]

- Heshmati, J.; Moini, A.; Sepidarkish, M.; Morvaridzadeh, M.; Salehi, M.; Palmowski, A.; Mojtahedi, M.F.; Shidfar, F. Effects of curcumin supplementation on blood glucose, insulin resistance and androgens in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Phytomedicine 2021, 80, 153395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Viennois, E.; Xu, C.; Merlin, D. Plant derived edible nanoparticles as a new therapeutic approach against diseases. Tissue Barriers 2016, 4, e1134415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, J.; Zhuang, X.; Wang, Q.; Jiang, H.; Deng, Z.B.; Wang, B.; Zhang, L.; Kakar, S.; Jun, Y.; Miller, D.; et al. Interspecies communication between plant and mouse gut host cells through edible plant derived exosome-like nanoparticles. Mol Nutr Food Res 2014, 58, 1561–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhuang, X.; Mu, J.; Deng, Z.B.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, L.; Xiang, X.; Wang, B.; Yan, J.; Miller, D.; et al. Delivery of therapeutic agents by nanoparticles made of grapefruit-derived lipids. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Qu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Y. Therapeutic effect and safety of curcumin in women with PCOS: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 1051111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akter, T.; Zahan, M.S.; Nawal, N.; Rahman, M.H.; Tanjum, T.N.; Arafat, K.I.; Moni, A.; Islam, M.N.; Uddin, M.J. Potentials of curcumin against polycystic ovary syndrome: Pharmacological insights and therapeutic promises. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiwari, P.M.; Vig, K.; Dennis, V.A.; Singh, S.R. Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles and Their Biomedical Applications. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2011, 1, 31–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzzarelli, C.; Stanic, V.; Gobbi, L.; Tosi, G.; Muzzarelli, R.A. Spray-drying of solutions containing chitosan together with polyuronans and characterisation of the microspheres. Carbohydrate Polymers 2004, 57, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Xu, Z.; Chen, S.; Gu, W.; Chen, L.; Li, Y. Arginine-chitosan/DNA self-assemble nanoparticles for gene delivery: In vitro characteristics and transfection efficiency. International journal of pharmaceutics 2008, 359, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, R.; Prabaharan, M.; Reis, R.; Mano, J. Graft copolymerized chitosan—present status and applications. Carbohydrate Polymers 2005, 62, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, R.; Nwe, N.; Tokura, S.; Tamura, H. Sulfated chitin and chitosan as novel biomaterials. International journal of biological macromolecules 2007, 40, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelma, R.; Sharma, C.P. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of curcumin loaded lauroyl sulphated chitosan for enhancing oral bioavailability. Carbohydrate Polymers 2013, 95, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, R.C.; Ng, T.B.; Wong, J.H.; Chan, W.Y. Chitosan: An Update on Potential Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Applications. Mar Drugs 2015, 13, 5156–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raja, M.A.; Maldonado, M.; Chen, J.; Zhong, Y.; Gu, J. Development and Evaluation of Curcumin Encapsulated Self-assembled Nanoparticles as Potential Remedial Treatment for PCOS in a Female Rat Model. Int J Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 6231–6247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Q.Q.; Xu, X.Y.; Cao, S.Y.; Gan, R.Y.; Corke, H.; Beta, T.; Li, H.B. Bioactive Compounds and Bioactivities of Ginger (Zingiber officinale Roscoe). Foods 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Sundaram, K.; Teng, Y.; Mu, J.; Sriwastva, M.K.; Zhang, L.; Hood, J.L.; Yan, J.; Zhang, X.; Park, J.W.; et al. Ginger nanoparticles mediated induction of Foxa2 prevents high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance. Theranostics 2022, 12, 1388–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.T.; Tung, T.H.; Jiesisibieke, Z.L.; Chien, C.W.; Liu, W.Y. Safety of Cinnamon: An Umbrella Review of Meta-Analyses and Systematic Reviews of Randomized Clinical Trials. Front Pharmacol 2021, 12, 790901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakovic, S.; Jakovljevic, V.; Jovic, N.; Andric, K.; Milinkovic, M.; Anicic, T.; Pindovic, B.; Kareva, E.N.; Fisenko, V.P.; Dimitrijevic, A.; et al. Exploring the Antioxidative Effects of Ginger and Cinnamon: A Comprehensive Review of Evidence and Molecular Mechanisms Involved in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and Other Oxidative Stress-Related Disorders. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, L.; Zheng, Y.; Li, L.; Gui, X.; Chen, Y.; Yu, M.; Guo, Y. The effect of cinnamon on polycystic ovary syndrome in a mouse model. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2018, 16, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borzoei, A.; Rafraf, M.; Asghari-Jafarabadi, M. Cinnamon improves metabolic factors without detectable effects on adiponectin in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2018, 27, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouame, K.; Peter, A.I.; Akang, E.N.; Moodley, R.; Naidu, E.C.; Azu, O.O. Histological and biochemical effects of Cinnamomum cassia nanoparticles in kidneys of diabetic Sprague-Dawley rats. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2019, 19, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yahya, R.; Al-Rajhi, A.M.H.; Alzaid, S.Z.; Al Abboud, M.A.; Almuhayawi, M.S.; Al Jaouni, S.K.; Selim, S.; Ismail, K.S.; Abdelghany, T.M. Molecular Docking and Efficacy of Aloe vera Gel Based on Chitosan Nanoparticles against Helicobacter pylori and Its Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activities. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosen, M.E.; Rahman, M.A.; Rahman, M.S.; Akash, S.; Khalekuzzaman, M.; Alsahli, A.A.; Bourhia, M.; Nafidi, H.A.; Islam, M.A.; Zaman, R. Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Camellia sinensis Leaf Extract: Promising Particles for the Treatment of Cancer and Diabetes. Chem Biodivers 2024, 21, e202301661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javid-Naderi, M.J.; Mahmoudi, A.; Kesharwani, P.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Recent advances of nanotechnology in the treatment and diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology 2023, 79, 104014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwan, S.H.; Al-Saeed, M.H. Silver Nanoparticles Biofabricated from Cinnamomum zeylanicum Reduce IL-6, IL-18, and TNF-ɑ in Female Rats with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome. Int J Fertil Steril 2023, 17, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Gao, P.; Du, J.; Zhao, X.; Wong, K.K.Y. Long-term anti-inflammatory efficacy in intestinal anastomosis in mice using silver nanoparticle-coated suture. J Pediatr Surg 2017, 52, 2083–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girigoswami, A.; Yassine, W.; Sharmiladevi, P.; Haribabu, V.; Girigoswami, K. Camouflaged Nanosilver with Excitation Wavelength Dependent High Quantum Yield for Targeted Theranostic. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 16459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatemi Abhari, S.M.; Khanbabaei, R.; Hayati Roodbari, N.; Parivar, K.; Yaghmaei, P. Curcumin-loaded super-paramagnetic iron oxide nanoparticle affects on apoptotic factors expression and histological changes in a prepubertal mouse model of polycystic ovary syndrome-induced by dehydroepiandrosterone - A molecular and stereological study. Life Sci 2020, 249, 117515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdallah, A.B.E.; El-Ghannam, M.A.; Hasan, A.A.; Mohammad, L.G.; Mesalam, N.M.; Alsayed, R.M. Selenium Nanoparticles Modulate Steroidogenesis-Related Genes and Improve Ovarian Functions via Regulating Androgen Receptors Expression in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome Rat Model. Biol Trace Elem Res 2023, 201, 5721–5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabah, H.M.; Mohamed, D.A.; Mariah, R.A.; Abd El-Khalik, S.R.; Khattab, H.A.; AbuoHashish, N.A.; Abdelsattar, A.M.; Raslan, M.A.; Farghal, E.E.; Eltokhy, A.K. Novel insights into the synergistic effects of selenium nanoparticles and metformin treatment of letrozole - induced polycystic ovarian syndrome: targeting PI3K/Akt signalling pathway, redox status and mitochondrial dysfunction in ovarian tissue. Redox Rep 2023, 28, 2160569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymek, M.; Sikora, E. Liposomes as biocompatible and smart delivery systems - the current state. Adv Colloid Interface Sci 2022, 309, 102757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Marioli, M.; Zhang, K. Analytical characterization of liposomes and other lipid nanoparticles for drug delivery. J Pharm Biomed Anal 2021, 192, 113642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, D.; Cavaco-Paulo, A.; Nogueira, E. Design of liposomes as drug delivery system for therapeutic applications. Int J Pharm 2021, 601, 120571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Józkowiak, M.; Kobylarek, D.; Bryja, A.; Gogola-Mruk, J.; Czajkowski, M.; Skupin-Mrugalska, P.; Kempisty, B.; Spaczyński, R.Z.; Piotrowska-Kempisty, H. Steroidogenic activity of liposomal methylated resveratrol analog 3,4,5,4'-tetramethoxystilbene (DMU-212) in human luteinized granulosa cells in a primary three-dimensional in vitro model. Endocrine 2023, 82, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prajapati, S.K.; Malaiya, A.; Kesharwani, P.; Soni, D.; Jain, A. Biomedical applications and toxicities of carbon nanotubes. Drug Chem Toxicol 2022, 45, 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Sharma, A.; Kang, C.; Han, J.; Tripathi, K.M.; Lee, H.J. N-Doped Carbon Nanorods from Biomass as a Potential Antidiabetic Nanomedicine. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2022, 8, 2131–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Tirado, E.; González-Cortés, A.; Yáñez-Sedeño, P.; Pingarrón, J.M. Magnetic multiwalled carbon nanotubes as nanocarrier tags for sensitive determination of fetuin in saliva. Biosens Bioelectron 2018, 113, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.K.; Jha, R.K.; Rout, D.; Gnanasekar, S.; Rana, S.V.S.; Hossain, M. Potential targetability of multi-walled carbon nanotube loaded with silver nanoparticles photosynthesized from Ocimum tenuiflorum (tulsi extract) in fertility diagnosis. J Drug Target 2017, 25, 616–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Luo, W.; Xu, Y.; Ling, J.; Deng, L. Potential reproductive toxicity of multi-walled carbon nanotubes and their chronic exposure effects on the growth and development of Xenopus tropicalis. Sci Total Environ 2021, 766, 142652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Yang, B.; Jiang, X.; Ma, X.; Lu, C.; Chen, C. Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes Inhibit Steroidogenesis by Disrupting Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory Protein Expression and Redox Status. J Nanosci Nanotechnol 2017, 17, 914–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, K.; Chatterjee, A.; Bankura, B.; Bank, S.; Paul, N.; Chatterjee, S.; Das, A.; Dutta, K.; Chakraborty, S.; De, S.; et al. Efficacy of pegylated Graphene oxide quantum dots as a nanoconjugate sustained release metformin delivery system in in vitro insulin resistance model. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0307166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagheri, E.; Ansari, L.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Ramezani, P.; Ramezani, M.; Alibolandi, M. Silica-Quantum Dot Nanomaterials as a Versatile Sensing Platform. Crit Rev Anal Chem 2021, 51, 687–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, Y.; Hao, X.; Shang, X.; Cai, M.; Jiang, J.; Tang, Z.; Wang, H. Recording force events of single quantum-dot endocytosis. Chem Commun (Camb) 2011, 47, 3377–3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Chang, Q.; Sun, Z.X.; Liu, J.; Deng, X.; Liu, Y.; Cao, A.; Wang, H. Fate of CdSe/ZnS quantum dots in cells: Endocytosis, translocation and exocytosis. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2021, 208, 112140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hunt, N.J.; Lockwood, G.P.; Le Couteur, F.H.; McCourt, P.A.G.; Singla, N.; Kang, S.W.S.; Burgess, A.; Kuncic, Z.; Le Couteur, D.G.; Cogger, V.C. Rapid Intestinal Uptake and Targeted Delivery to the Liver Endothelium Using Orally Administered Silver Sulfide Quantum Dots. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 1492–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, N.; Zhang, M.; Kim, K. Quantum Dots and Their Interaction with Biological Systems. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-García, D.; Díaz-Sánchez, M.; Álvarez-Conde, J.; Gómez-Ruiz, S. Emergence of Quantum Dots as Innovative Tools for Early Diagnosis and Advanced Treatment of Breast Cancer. ChemMedChem 2024, 19, e202400172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V.; Kashyap, S.; Yadav, U.; Srivastava, A.; Singh, A.V.; Singh, R.K.; Singh, S.K.; Saxena, P.S. Nitrogen doped carbon quantum dots demonstrate no toxicity under in vitro conditions in a cervical cell line and in vivo in Swiss albino mice. Toxicol Res (Camb) 2019, 8, 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshizawa, M.; Catti, L. Aromatic micelles: toward a third-generation of micelles. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci 2023, 99, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Xue, L.; Guo, Y.; Dong, X.; Chen, Z.; Wei, S.; Yi, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, S.; et al. Microenvironmentally Responsive Chemotherapeutic Prodrugs and CHEK2 Inhibitors Self-Assembled Micelles: Protecting Fertility and Enhancing Chemotherapy. Adv Mater 2023, 35, e2210017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazarian, M.; Aramjoo, H.; Roshanravan, B.; Samarghandian, S.; Farkhondeh, T. Protective Effects of Curcumin and Nanomicelle Curcumin on Chlorpyrifos-induced Oxidative Damage and Inflammation in the Uterus, Ovary and Brain of Rats. Curr Pharm Biotechnol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roshanfekr Rad, M.; Nejati, V.; Razi, M.; Najafi, G. Nano-micelle Curcumin; A Hazardous and/or Boosting Agent? Relation with Oocyte In-vitro Maturation and Pre-implantation Embryo Development in Rats. Iran J Pharm Res 2020, 19, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, S.I.; Lee, S.K.; Goh, E.A.; Kwon, O.S.; Choi, W.; Kim, J.; Lee, M.S.; Choi, S.J.; Lim, S.S.; Moon, T.K.; et al. Weekly treatment with SAMiRNA targeting the androgen receptor ameliorates androgenetic alopecia. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Sun, X.; Liu, G.; Ma, R.; Li, Z.; An, Y.; Shi, L. Glucose-responsive complex micelles for self-regulated release of insulin under physiological conditions. Soft Matter 2013, 9, 8589–8599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orisaka, M.; Mizutani, T.; Miyazaki, Y.; Shirafuji, A.; Tamamura, C.; Fujita, M.; Tsuyoshi, H.; Yoshida, Y. Chronic low-grade inflammation and ovarian dysfunction in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome, endometriosis, and aging. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2023, 14, 1324429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Broi, M.G.; Giorgi, V.S.I.; Wang, F.; Keefe, D.L.; Albertini, D.; Navarro, P.A. Influence of follicular fluid and cumulus cells on oocyte quality: clinical implications. J Assist Reprod Genet 2018, 35, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orisaka, M.; Miyazaki, Y.; Shirafuji, A.; Tamamura, C.; Tsuyoshi, H.; Tsang, B.K.; Yoshida, Y. The role of pituitary gonadotropins and intraovarian regulators in follicle development: A mini-review. Reprod Med Biol 2021, 20, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naby, A.A.H.; Ibrahim, S.; Hozyen, H.F.; Sosa, A.S.A.; Mahmoud, K.G.M.; Farghali, A.A. Impact of nano-selenium on nuclear maturation and genes expression profile of buffalo oocytes matured in vitro. Mol Biol Rep 2020, 47, 8593–8603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaz, F.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Khazaei, M.; Arkan, E.; Sajadimajd, S.; Mozafari, H.; Rahimi, Z.; Pourmotabbed, T. Co-encapsulation of tertinoin and resveratrol by solid lipid nanocarrier (SLN) improves mice in vitro matured oocyte/ morula-compact stage embryo development. Theriogenology 2021, 171, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Huang, L.; Qiu, L.; Li, S.; Yan, Y.; Ding, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, F.; Shi, X.; Zhao, J.; et al. Enhancing oocyte in vitro maturation and quality by melatonin/bilirubin cationic nanoparticles: A promising strategy for assisted reproduction techniques. Int J Pharm X 2024, 8, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, S.; Sali, V. Connecting the dots in drug delivery: A tour d'horizon of chitosan-based nanocarriers system. Int J Biol Macromol 2021, 169, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraru, C.; Mincea, M.M.; Frandes, M.; Timar, B.; Ostafe, V. A Meta-Analysis on Randomised Controlled Clinical Trials Evaluating the Effect of the Dietary Supplement Chitosan on Weight Loss, Lipid Parameters and Blood Pressure. Medicina (Kaunas) 2018, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Gómez, C.P.; Cecilia, J.A. Chitosan: A Natural Biopolymer with a Wide and Varied Range of Applications. Molecules 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guzmán, E.; Ortega, F.; Rubio, R.G. Chitosan: A Promising Multifunctional Cosmetic Ingredient for Skin and Hair Care. Cosmetics 2022, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafernik, K.; Ładniak, A.; Blicharska, E.; Czarnek, K.; Ekiert, H.; Wiącek, A.E.; Szopa, A. Chitosan-Based Nanoparticles as Effective Drug Delivery Systems-A review. Molecules 2023, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosano, G.; Caille, A.M.; Gallardo-Ríos, M.; Munuce, M.J. D-Mannose-binding sites are putative sperm determinants of human oocyte recognition and fertilization. Reprod Biomed Online 2007, 15, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, B.; Qi, X.; Yun, C.; Qiao, J.; Pang, Y. Effects of Androgen Excess-Related Metabolic Disturbances on Granulosa Cell Function and Follicular Development. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2022, 13, 815968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.H.; Liu, X.Y.; Wang, J. Essential Role of Granulosa Cell Glucose and Lipid Metabolism on Oocytes and the Potential Metabolic Imbalance in Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirotkin, A.V.; Radosová, M.; Tarko, A.; Martín-García, I.; Alonso, F. Effect of morphology and support of copper nanoparticles on basic ovarian granulosa cell functions. Nanotoxicology 2020, 14, 683–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabandeh, M.R.; Samie, K.A.; Mobarakeh, E.S.; Khadem, M.D.; Jozaie, S. Silver nanoparticles induce oxidative stress, apoptosis and impaired steroidogenesis in ovarian granulosa cells of cattle. Anim Reprod Sci 2022, 236, 106908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Nanocarrier | Key Ingredient | Therapeutic Agent | Research object | Mechanism | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chitosan nanoparticles | Chitosan | Curcumin | Rat | Reduce the levels of serum luteinizing hormone , prolactin, testosterone and insulin | [95] |

| 2 | Ginger nanoparticles | Lipid | Ginger | Mice | Elevated the expression of forkhead transcription factor (Foxa2) to mitigate insulin resistance induced by intestinal epithelial cell (IEC) exosomes. | [97] |

| 3 | Silver nanoparticles | Silver | Cinnamomum cassia | Rat | Antioxidant | [102] |

| 4 | Silver nanoparticles | Silver | Cinnamomum zeylanicum | Rat | Reduce the levels of inflammatory markers such as IL-6, IL-18, and TNF - α | [106] |

| 5 | Iron nanoparticles | Iron oxide | Curcumin | Mice | Inhibition of ovarian injury cell apoptosis and dehydroepiandrosterone induced cell apoptosis | [109] |

| 6 | Selenium nanoparticles | Chitosan | Selenium dioxide | Rat | Reduce androgen synthesis and block the vicious cycle caused by excessive androgen secretion by reducing the expression of androgen receptors | [110] |

| 7 | Selenium nanoparticles | Chitosan | Selenium dioxide | Rat | Upregulation of PI3K and Akt gene expression reduces insulin sensitivity, lipid profile, sex hormone levels, inflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial functional markers | [111] |

| 8 | Liposomes | Glycerol phospholipid | Methoxy derivatives of resveratrol (DMU-212) | Ovarian granulosa cells | Increase the secretion of estradiol and progesterone | [115] |

| 9 | Carbon nanotubes | Silkworm powder | Nitrogen doped carbon nanorods (N-CNR) | Mice | Reduce fasting blood glucose and improve serum biomarker levels associated with oxidative stress and inflammation | [117] |

| 10 | Quantum dot | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) | Metformin | Hepg2 cells | Restore glucose uptake and reverse insulin resistance | [122] |

| 11 | Micelle | / | Curcumin | Rat | Reduced oxidative damage and inflammatory response | [132] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).