Submitted:

23 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design & Context of the SPLE weeks

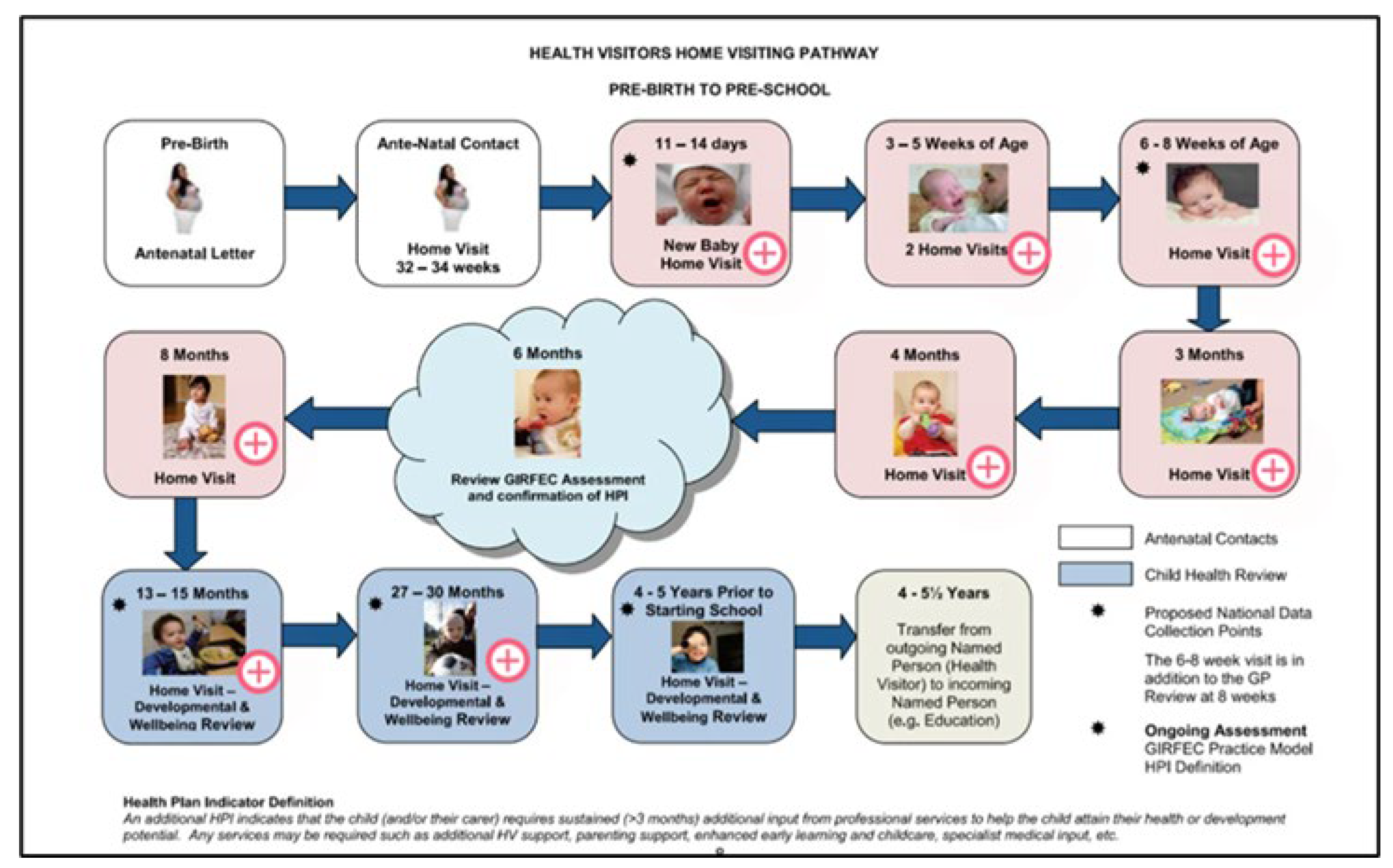

- Week 1 - Maternity Care SPLE

- Week 2 - Learning Disability SPLE

- Week 3 - Child Health SPLE

- Week 4 - Community VPLE

2.2. Study Design & Methodology

2.3. Ethical Implications

3. Results

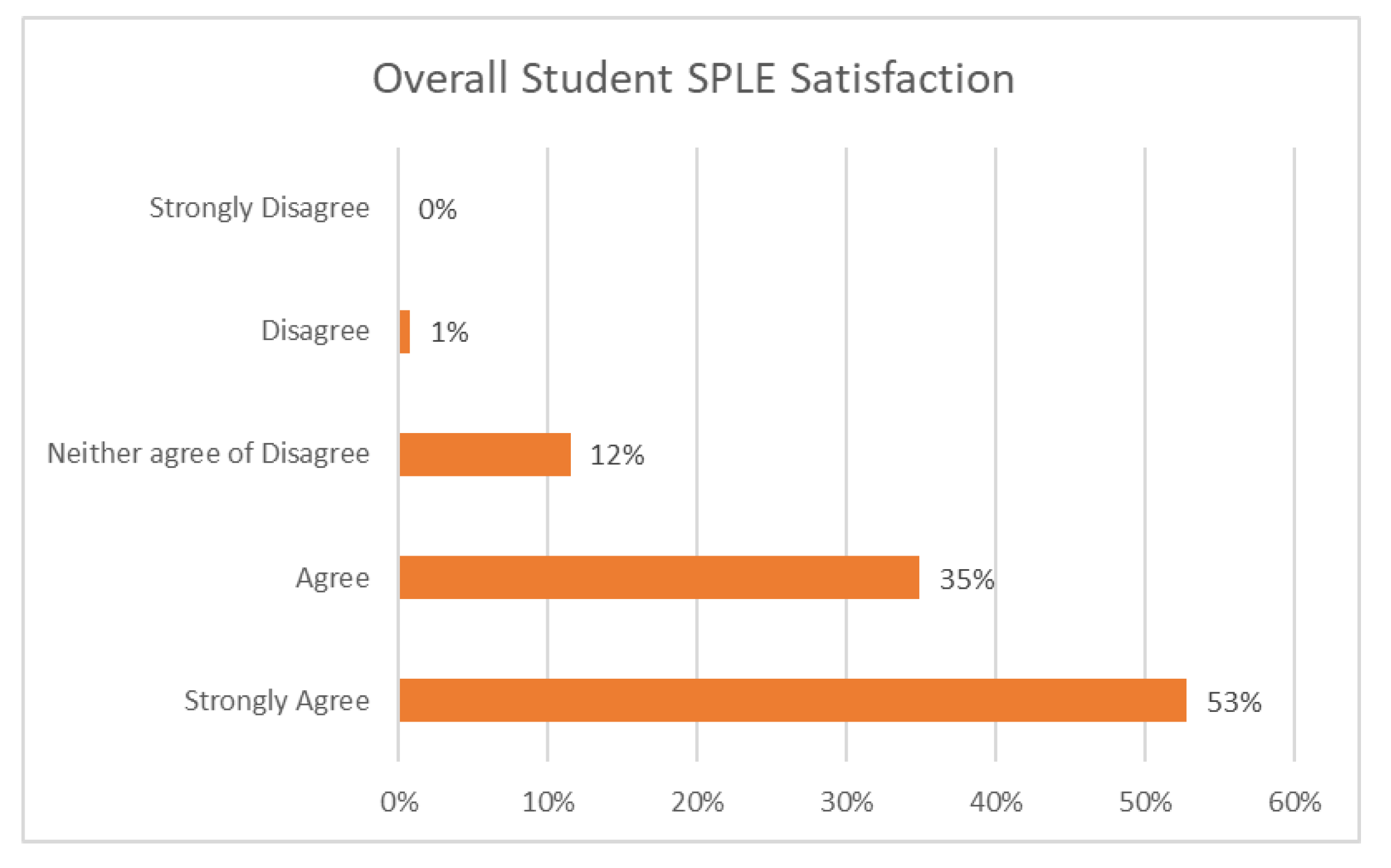

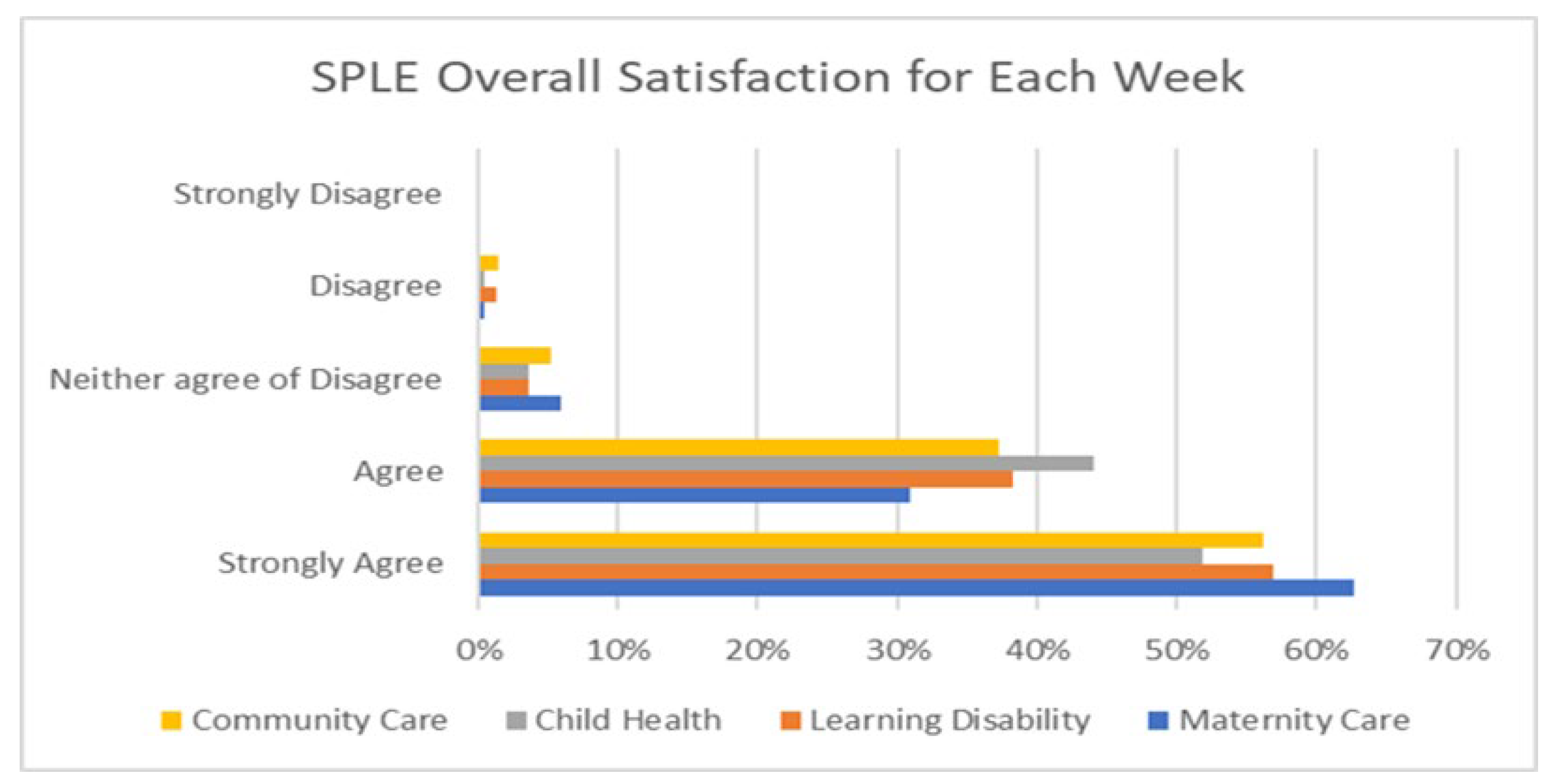

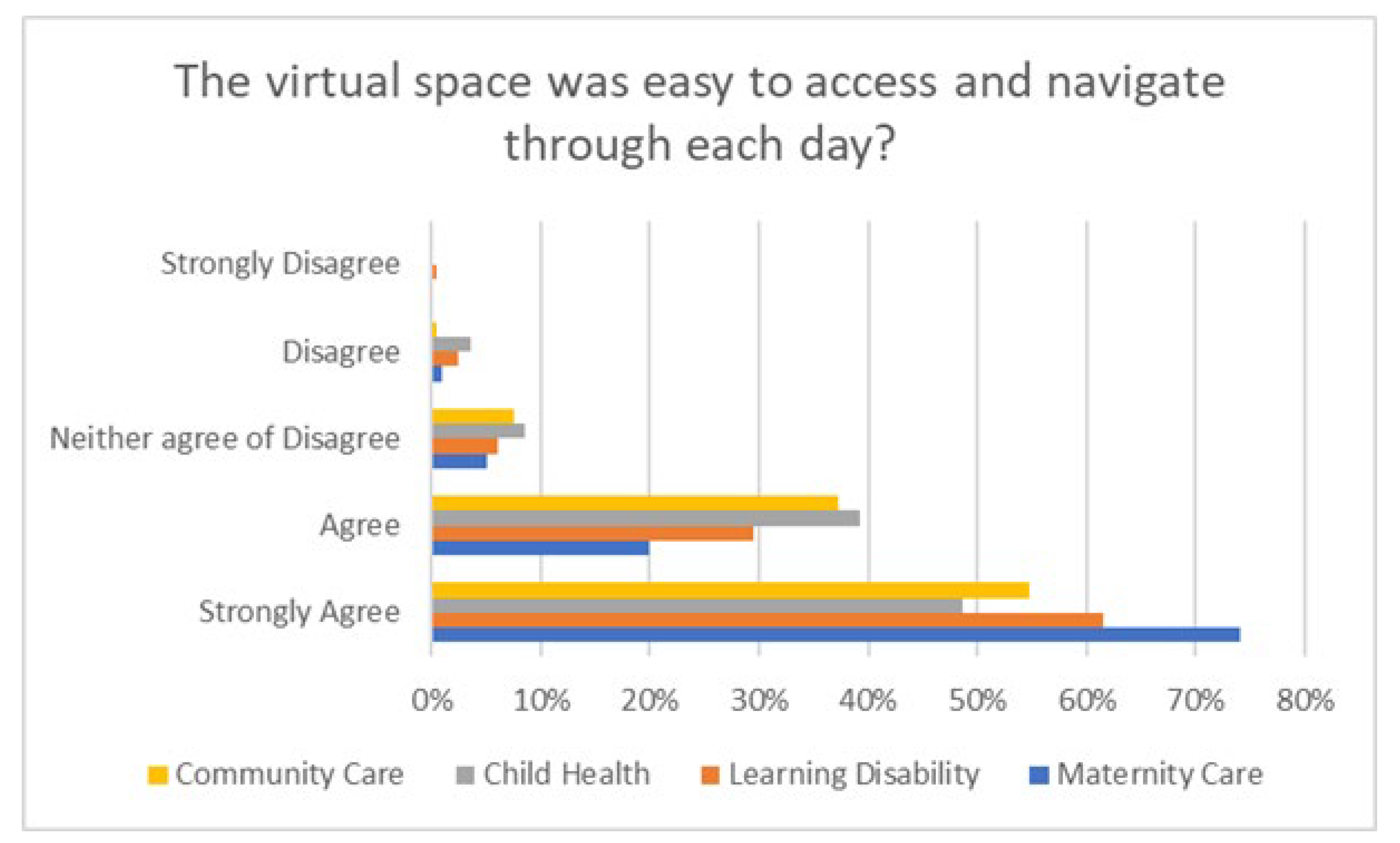

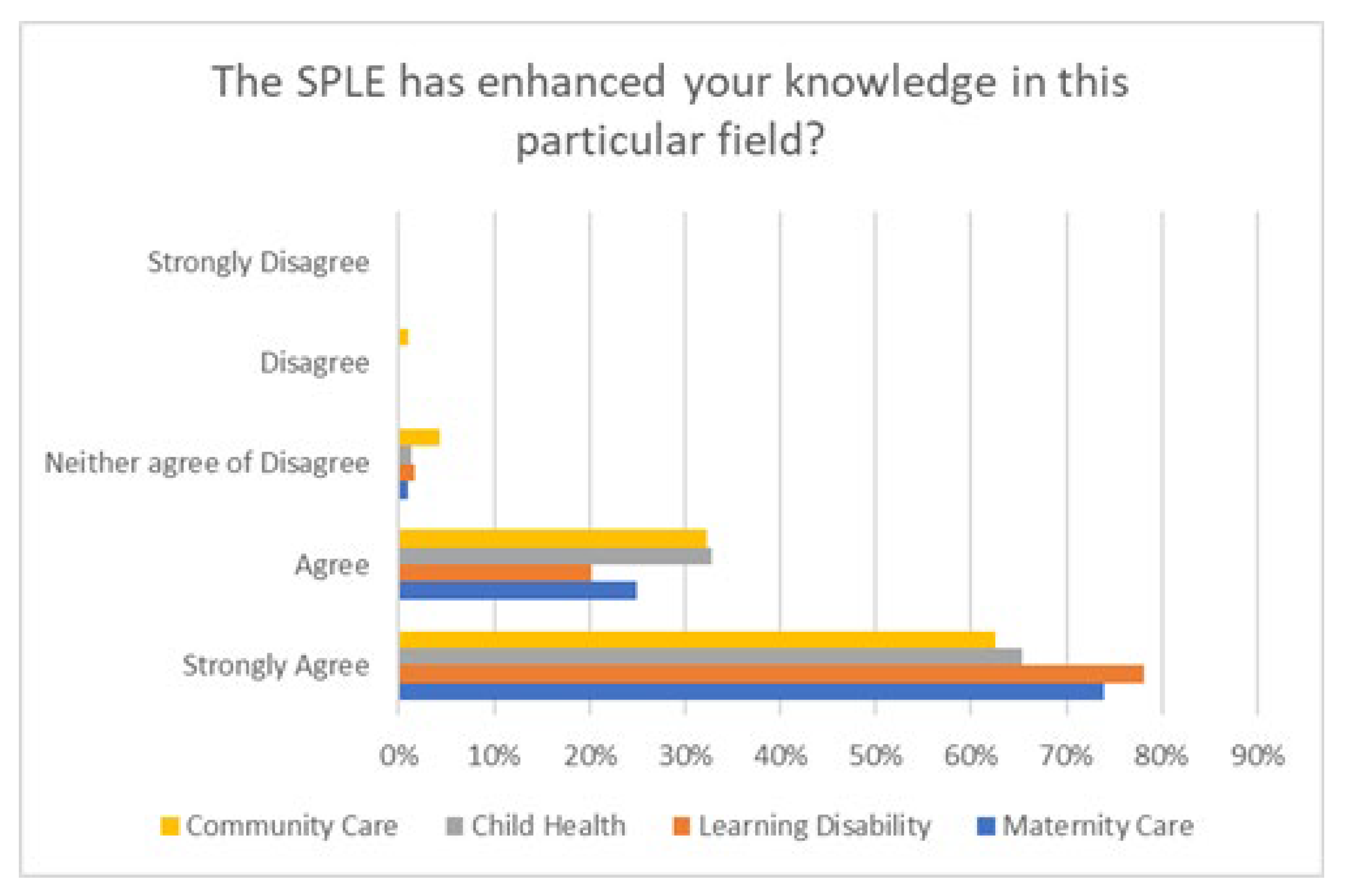

3.1. Quantitative

- Variation in sample size across the week’s accounts for sickness, non-engagement and students on leave of absence.

3.2. Qualitative

- Transferable Skills & Personal Growth

- Peer Learning

- Benefits of Learning Within the Virtual Environment

- Appreciation of Service User and Health Care Professional Input

- Areas For Improvement

4. Discussion

4.1. Transferable Skills & Personal Growth

4.2. Peer Learning

4.3. Benefits of Learning Within the Virtual Environment

4.4. Appreciation of Service User and Health Care Professional Input

4.5. Areas for Improvement

4.6. Strengths

4.7. Limitations

4.8. Future Considerations and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Public Involvement Statement

Guidelines and Standards Statement

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leary:, M.; Demiris, G.; Brooks Carthon, J.M.; Cacchione, P.Z.; Aryal, S.; Bauermeister, J.A. Determining the innovativeness of nurses who engage in activities that encourage innovative behaviors. Nurs. Rep. 2024, 14, 849–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. Current Recovery Programme Standards; NMC: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. Standards Framework for Nursing and Midwifery Education; NMC: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Pit, S.W.; Velovski, S.; Cockrell, K.; Bailey, J. A qualitative exploration of medical students' placement experiences with telehealth during COVID-19 and recommendations to prepare our future medical workforce. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 1–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- West, R. Adapting to online placements. Br. J. Nurs. 2021, 30, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mian, A.; Khan, S. Medical education during a pandemic: a UK perspective. BMC Med. 2020, 18, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triemstra, J.D.; Haas, M.R.C.; Bhavsar-Burke, I.; Gottlieb-Smith, R.; Wolff, M.; Shelgikar, A.V.; Samala, R.V.; Ruff, A.L.; Kuo, K.; Tam, M.; Gupta, A.; Stojan, J.; Gruppen, L.; Ellinas, H. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the clinical learning environment: Addressing identified gaps and seizing opportunities. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 1276–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, A.G.; Soheilian, S.S.; Luu, L.P. Telesupervision: Building bridges in a digital era. J. Clin. Psychol. 2019, 75, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twogood, R.; Hares, E.; Wyatt, M.; Cuff, A. Rapid implementation and improvement of a virtual student placement model in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. BMJ Open Qual. 2020, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peart, A.; Wells, N.; Yu, M.; Brown, T. ‘It became quite a complex dynamic’: The experiences of occupational therapy practice educators' move to digital platforms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Aust. Occup. Ther. J. 2022, 69, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salje, J.; Moyo, M. Implementation of a virtual student placement to improve the application of theory to practice. Br. J. Nurs. 2023, 32, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perone, A.K. Surviving the semester during COVID-19: Evolving concerns, innovations, and recommendations. J. Soc. Work 2021, 57, 194–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldridge, M.D.; McQuagge, E. "Finding my own way": The lived experience of undergraduate nursing students learning psychomotor skills during COVID-19. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2021, 16, 347–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, S.H.J.; Chow, M.S.C.; Lam, W.W.T. Medical education and mental wellbeing during COVID-19: A student’s perspective. Med. Sci. Educ. 2021, 31, 1183–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, D.; Louca, C.; Leeves, L.; Rampes, S. Undergraduate medical education and COVID-19: Engaged but abstract. Med. Educ. Online 2020, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, M.; Stapleton, E. Undergraduate experience of ENT teaching during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A qualitative study. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2021, 138, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franklin, G.; Martin, C.; Ruszaj, M.; Matin, M.; Kataria, A.; Hu, J.; Brickman, A.; Elkin, P.L. How the COVID-19 pandemic impacted medical education during the last year of medical school: A class survey. Life 2021, 11, 294, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amankwaa, I.; Boateng, D.; Quansah, D.Y.; Akuoko, C.P.; Desu, A.P.B.; Hales, C. Innovations in nursing education in response to the COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. Nurs. Prax. Aotearoa N. Z. 2022, 38, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, D.; Twycross, A. Impact of COVID-19 on nursing students’ mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Evid. Based Nurs. 2022, 25, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jowsey, T.; Foster, G.; Cooper-Ioelu, P.; Jacob, S. Blended learning via distance in preregistration education: A scoping review. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2020, 44, 102775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, K.Y.; Binil, V. E-learning challenges in nursing education during COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative review. Indian J. Forensic Med. Toxicol. 2021, 15, 2317–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiskow, K.M.; Subramaniam, S.; Montenegro-Montenegro, E. A comparison of individual and group equivalence-based instruction delivered via Canvas. J. Appl. Behav. Anal. 2024, 57, 262–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, C.W.; Rodrigues, S.M.; Jones-Patten, A.E.; Ju, E.; Abrahim, H.L.; Saatchi, B.; Wilcox, S.P.; Bender, M. Novel pedagogical training for nursing doctoral students in support of remote learning: A win-win situation. Nurse Educ. 2021, 46, (4), E79–E83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.A.F.A.; Souza, M.M.P.; Barros, T.D.; Nishu, G.; Reis, M.J.C.S. Using the ThingLink computer tool to create a meaningful environmental learning scenario. EAI Endorsed Trans. Smart Cities 2022, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffery, A.J.; Rogers, S.L.; Jeffery, K.L.A.; Hobson, L. A flexible, open, and interactive digital platform to support online and blended experiential learning environments: Thinglink and thin sections. Geoscience Commun. 2021, 4, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yew, E.H.J.; Goh, K. Problem-based learning: An overview of its process and impact on learning. Health Prof. Educ. 2016, 2, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFoor, M.; Darby, W.; Pierce, V. “Get connected”: Integrating telehealth triage in a prelicensure clinical simulation. J. Nurs. Educ. 2020, 59, 518–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.; Leontino, G. Learning disability simulations for all student nurses. Br. J. Nurs. 2023, 32, 98–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsin, W.; Cigas, J. Short videos improve student learning in online education. J. Comput. Sci. Coll. 2013, 28, 253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, L. Challenges and opportunities: the role of the district nurse in influencing practice education. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2020, 25, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. Standards of Proficiency for Registered Nurses; NMC: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nursing and Midwifery Council. Standards for Student Supervision and Assessment; NMC: London, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, J.L.; Sanders, J.R.; Worthen, B.R. Program Evaluation: Alternative Approaches and Practical Guidelines, 4th ed.; Pearson: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- NHS Education for Scotland. Indicators for the Quality Standards for Practice Learning; NES: Edinburgh, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D.K. Likert scale: Explored and explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Thematic Analysis: A Practical Guide; Sage: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Billet, S. Integrating learning experiences across tertiary education and practice settings: A socio-personal account. Educ. Res. Rev. 2014, 12, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, A.; Briggs, J.; Schoonbeek, S.; Paterson, K. A framework to develop a clinical learning culture in health facilities: Ideas from the literature. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2011, 58, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, A.; Bell, A. Peer learning partnerships: Exploring the experience of pre-registration nursing students. J. Clin. Nurs. 2010, 19, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stone, R.; Cooper, S.; Cant, R. The value of peer learning in undergraduate nursing education: A systematic review. Int. Scholarly Res. Notices 2013, 930901–930911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuti, B.; Houghton, T. Service user involvement in teaching and learning: Student nurse perspectives. J. Res. Nurs. 2019, 24, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Ooms, A.; Maran-Marks, D. Active involvement of learning disabilities service users in the development and delivery of a teaching session to pre-registration nurses: Students' perspectives. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2016, 16, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odro, A.; Clancy, C.; Foster, J. Bridging the theory-practice gap in student nurse training: An evaluation of a personal and professional development programme. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2010, 5, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SPLE Week | Completed Questionnaire |

|---|---|

| Maternity Care | 216 |

| Leaning Disability | 205 |

| Child Health | 198 |

| Community Care | 199 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).