Few studies have been conducted on second-order false-belief tasks in people with Williams syndrome (WS). Sullivan and Tager-Flusberg (1999) employed second-order false belief tasks among people with WS, Prader-Willis syndrome (PWS), and nonspecific mental retardation (NMR). People with WS did not outperform people with PWS and NMR. However, they demonstrated similar patterns in processing second-order false belief questions. Karmiloff-Smith et al. (1995) conducted tasks on the second-order theory of mind among people with WS and people with autism. People with WS passed the tasks with over 88% accuracy rate compared to the 20% low accuracy rate of people with autism spectrum disorder. This finding suggests that people with WS possess the ability to mentalize others’ minds despite deficient spatial and number cognition. Thus, conflicting results emerged. However, the sample was larger (n=22) with a similar mental age of 8.56 in Sullivan and Tager-Flusberg’s study. Conversely, the sample was smaller (n=8) with an unclear exact testing age in Karmiloff-Smith et al.’s study. Traditionally children aged 6–7 years could pass the English version of the second-order false belief task (Frith, 1989; Perner & Wimmer, 1985). However, people with WS passed the tasks at approximately 9 years old, which was later than the critical age. Limited studies have been conducted on the second-order false belief in people with WS. No other studies presented results in which people with WS passed the second-order false belief tasks at an earlier age. This study aimed to investigate whether the ability of the second-order false belief in people with WS could be improved via more vivid animations.

Second-order false belief ability refers to an individual’s ability to reason with others’ minds. Previous studies that examined this mentalizing ability in people with WS focused on mindreading tasks or tasks of the first-order false beliefs. Tager-Flusberg et al.’s study (1998) used the mind-reading task of eyes with various expressions on thoughts and emotions and assessed people with WS and control groups of people with PWS and typical development (TD). People with PWS and TD had the lowest and highest accurate in responding to the eyes, respectively. People with WS had an average accuracy. These results suggested that people with WS were not completely impaired in mentalizing other people’s minds through eyes; however, they still did not develop similarly to their TD controls.

Causal inference is the main point of false-belief reasoning, and advanced causal inference is required in second-order false-belief reasoning. Hsu (2013) conducted studies on forward and backward verbal reasoning in people with WS. In the forward reasoning, participants listened to sentences embedded with figurative words in the final positions, e.g., “Sponge Bob would like to eat the candies on a shelf. He asked for help from Squidward Tentacles. But Squidward Tentacles dampened Sponge Bob’s enthusiasm (original Chinese text) 海绵宝宝想吃柜子上的糖果,找章鱼哥帮忙,结果被章鱼哥泼冷水.” The literal and figurative meanings of the word “泼冷水” means to pour cold water on someone and dampen one’s enthusiasm, respectively. Participants had to choose the correct interpretation from three choices after listening to each sentence. People with WS had similar responses as the mental age (MA) controls. However, they significantly differed in responding to forward causal reasoning than the chronological age (CA) controls. In the backward reasoning, participants listened to sentences embedded with figurative words in the final positions, e.g., “Daxung failed the exam this time. His mother often reminded him to study hard, but Daxung was inattentive to his mother’s reminders (original Chinese text) 大雄这次考试不及格,妈妈平常叫大雄认真读书,大雄都把妈妈的话当作耳边风.” People with WS had the lowest accuracy compared with the MA and CA groups. These findings suggested that people with WS exhibited different causal and deficient reasoning abilities. This might be converging evidence to support impaired ability on second-order false belief tasks among people with WS.

With technological invention to improve presented materials, the comprehension of false belief could be enhanced (Hsu & Rao, 2023). Previous studies reported that people with WS older than 9 years of age and even at 21 years old failed first-order false-belief tasks. Hsu and Rao used animation clips to narrate scripts on first-order false belief tasks and found that people with WS showed had the ability to mentalize others’ minds at age 5.9 years. This finding suggests that beyond the traditional 2D presentation of actions embedded in false-belief tasks, 3D animation advanced technology could enhance the ability of people with WS to infer others’ mental states. This study aimed to examine the ability of second-order false belief among people with WS via 3D animation clips as computerized testing materials.

Methods

Participants

This study included five groups of participants. In total, 19 people with WS (five females/14 males, mean CA = 12.81, SD = 2.59, range = 9.60–19.20; mean MA = 9.10, SD = 2.03, range = 6.16–15.17) were recruited across all provinces in China. All participants were genetically diagnosed at hospitals at various ages. We individually matched two groups of participants with typical development in CA and MA with gender to those with WS via the Wechsler Scale of Intelligence for Children (4th edition, Chinese version). No difference was observed between the WS group and CA and MA groups regarding chronological and mental age, respectively. The CA and MA controls differed in age [

t(18) = 9.030,

p < 0.001], which indicated different developmental stages. Furthermore, two groups of healthy 5-and 6 years old children (11F/11M, 5 years old, mean age = 5.22, SD = 0.18; 11F/11M, 6 years old, mean age = 6.14, SD = 0.14;

t(41) = -21.627,

p < 0.001) were recruited as baseline for the second-order false belief task from a kindergarten in Changsha, Hunan Province, China.

Table 1 presents the participants’ background information. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Foreign Languages of Hunan University, China (20210628000004).

Materials and Design

We conducted 20 trials that assessed second-order false beliefs digitized and presented as cartoons (total length = 31.85 min, mean = 1.60 min, SD = 0.07 min). Two practice trials were offered before the task began (total length = 3.30 min, mean = 1.65 min, SD = 0.05 min). Each video was a scenario with three cartoon-protagonists who acted according to a script. All experimental trials were creatively organized in a parallel structured design to the second-order false-belief task. Each scenario was well arranged with one template, in the sequence of a general setting, an action on a key object, an action of changing its location for the first time, one left character, an action of changing location a second time, one transition point, another left character, an action of changing the location a third time, followed by comprehension questions. The comprehension questions included the most important second-order false-belief inducer (whether participants could infer protagonist B’s belief regarding protagonist A’s mental state), recognition of characters (triple characters in each scenario), memory (location of the key object was placed the second time), and reality (the final location of the key object).

Table 2 presents an example of the scenario of the second-order false belief task.

Children’s developmental stage of language comprehension was considered when the scenario scripts were designed. Strict selection of the key objects and contexts was applied. Time points (e.g., okay at that time) rather than explicit time expressions (e.g., before, after, then) were narrated. With effort, scenarios shown in videos were ready to be assessed. A total of five experimental triple cartoon characters were selected: (1) Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Panda Kiki, (2) Tom Cat, Jerry Mouse, Minion, (3) SpongeBob, Patrick Star, Doraemon, (4) Winnie the Pooh, Tigger, Peppa, and (5) Pleasant Goat, Grey Wolf, Slowy Goat. In a practice session, the triple characters were Pikachu, Squirtle, and Charmander. Each triple cartoon characters were shown twice in different videos. All cartoon characters were highly familiar to children in China and purchased from a picture-producing company that owned their copyrights. Video narrations were recorded in a male and female voice, changed alternatively every five trials. Supplementary material animation videos were created via Photoshop software. Subsequently, the narrations were recorded via a cell phone. The triple characters were introduced consecutively at the beginning of each video.

Procedure

Participants were individually assessed by the experimenter in a quiet room. Participants received practice trials. Participants were instructed to watch each video quietly with full attention. After they had watched each trial, they responded to comprehension questions. Simultaneously, the experimenter wrote the participants’ responses on an answer sheet, where code 1 and 0 indicated correct and incorrect responses, respectively.

Results

To determine the pattern of second-order false belief tasks, studies were conducted on 5–6 year old Chinese-speaking children with typical development. Correct responses were analyzed.

Analyses of 5- and 6-Year-Old Groups

Correct responses, which included the accurate recognition of characters (recognition questions), accurate inferences regarding second-order false beliefs (belief questions), accurate identification of the target object’s location in the final situation (reality question), and accurate indication of the original position (memory question), were analyzed.

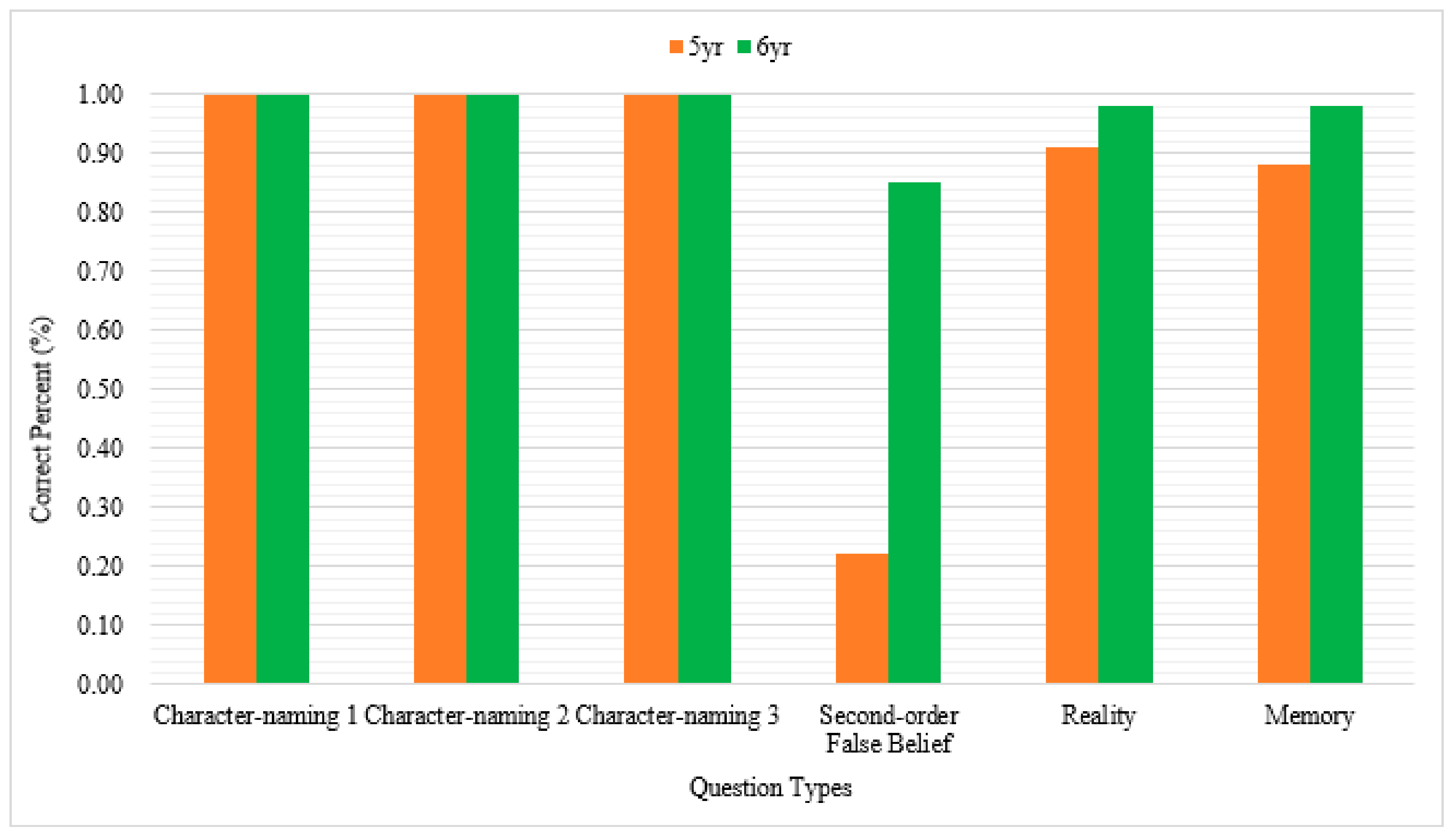

Non-parametric binomial statistics tests were used to analyze the second-order false-belief task data. Both 5- and 6-year-old children passed the recognition of characters test (p < 0.001) with highly accurate values (100% in both age groups [SD = 0]) in video comprehension. Moreover, both age groups also showed highly accurate responses to the reality question (5-year-olds, 91%, SD = 0.29; 6-year-olds, 98%, SD = 0.13). Fisher’s exact test revealed a significant difference between the 5- and 6-year-olds (p < 0.00001). The memory question also reached a high accuracy level in both the groups (5-year-olds, 88%, SD = 0.32; 6-year-old, 98%, SD = 0.13). Fisher’s exact test revealed a significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.00001).

Regarding the key second-order false-belief questions, the two groups of 5- and 6-year-olds revealed significant differences. The 5- and 6-year-olds exhibited a low passing percentage and relatively high accuracy for the second-order false-belief task (22%, SD = 0.41 and 85%, SD = 0.36), respectively. Multivariate analyses of variance revealed group differences in the false-belief question,

F(1,878) = 594.72,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.404, which suggested that 6-year-olds had attained the milestone of discerning second-order false belief compared to 5-year-olds. Fisher’s exact test revealed a significant difference between the two groups (

p < 0.00001) in the second-order false-belief question. Multivariate analyses revealed group difference in responding to the reality [

F(1,878) = 26.17,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.029] and memory questions [

F(1,878) = 38.30,

p < 0.001,

η2 = 0.042], which suggested higher accuracy in 6-year-olds than 5-year-olds. These differences indicated advanced cognitive development in older children.

Figure 1 illustrates the accuracy of 5-year-olds and 6-year-olds.

Analyses of People with Williams Syndrome and the Two Control Groups

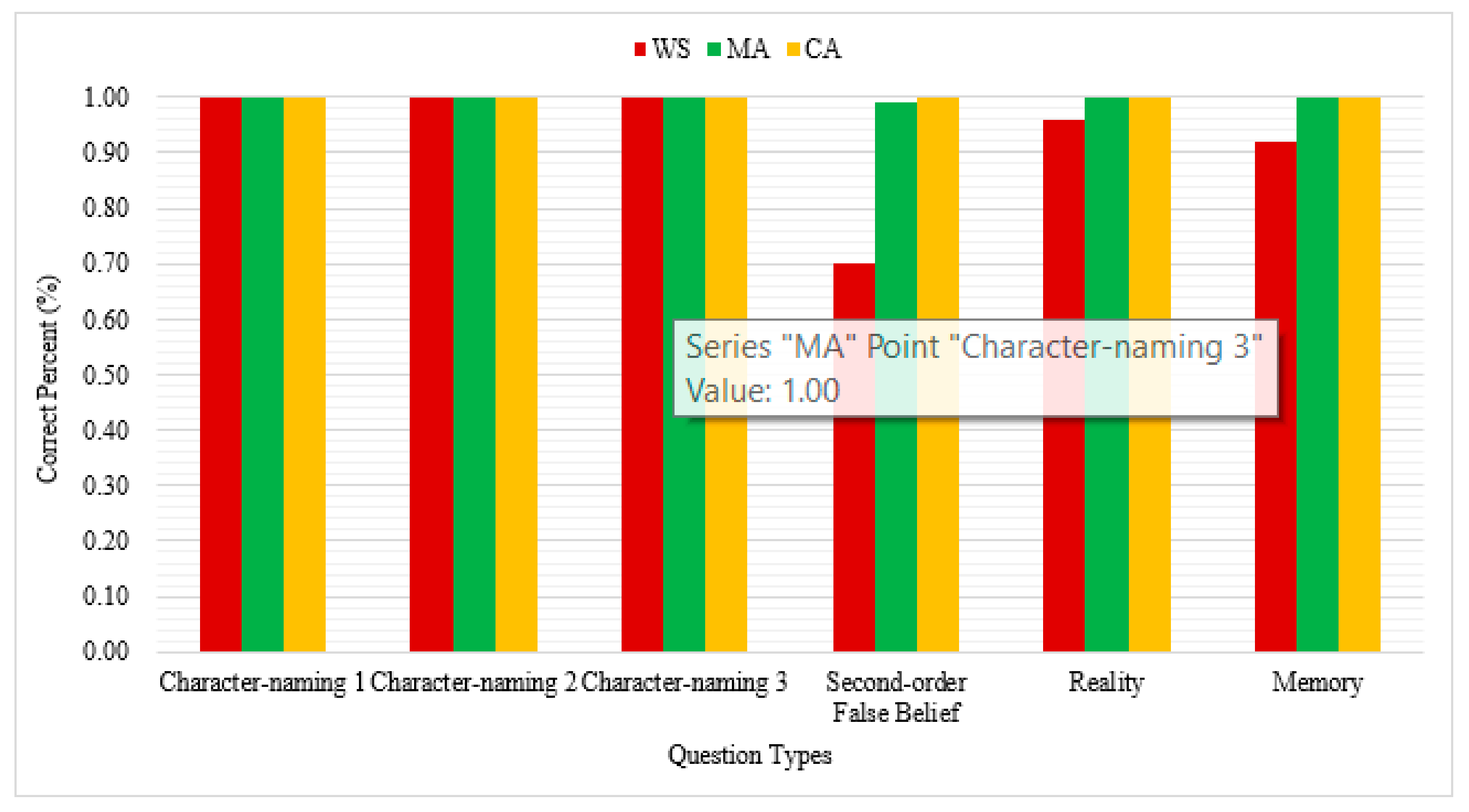

Non-parametric binomial statistical tests were used to analyze the second-order false-belief task data of each group based on each question. The average of all correct responses was calculated. The higher percentage of the type of observatory response was compared with the expected value of the chance level, 0.50. If the difference between the observatory and expected value reached significance, the performance (e.g., false belief passing or failing rate) was valid. This validation confirmed whether the participants in that group had succeeded or failed the test. Significant differences were observed in the comprehension questions of character recognition, reality, and memory between each group [100% in three character-naming questions: WS, MA, CA; reality question: WS, 96%; MA, 100%; CA, 100%; memory question: WS, 92%; MA, 100%; CA, 100%]. Regarding responses to the second-order false-belief question, people with WS had 70% accuracy compared to a passing rates of 99% and 100% of the MA and CA controls, respectively.

Figure 2 illustrates the response percentages of the three groups for all the types of questions.

A multivariate analysis of variance revealed group differences in responding to questions related to reality [F(2, 1137) = 14.49, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.025], memory [F(2, 1137) = 34.85, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.058] and second-order false belief [F(2, 1137) = 155.74, p < 0.001, η2 = 0.215]. Post-hoc analyses with Tukey’s comparison showed significant differences between the WS group and two control groups (MA and CA) regarding the reality, memory, and second-order false belief questions (p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed between the MA and CA groups. This finding suggested that people with WS differed in processing second-order false beliefs.

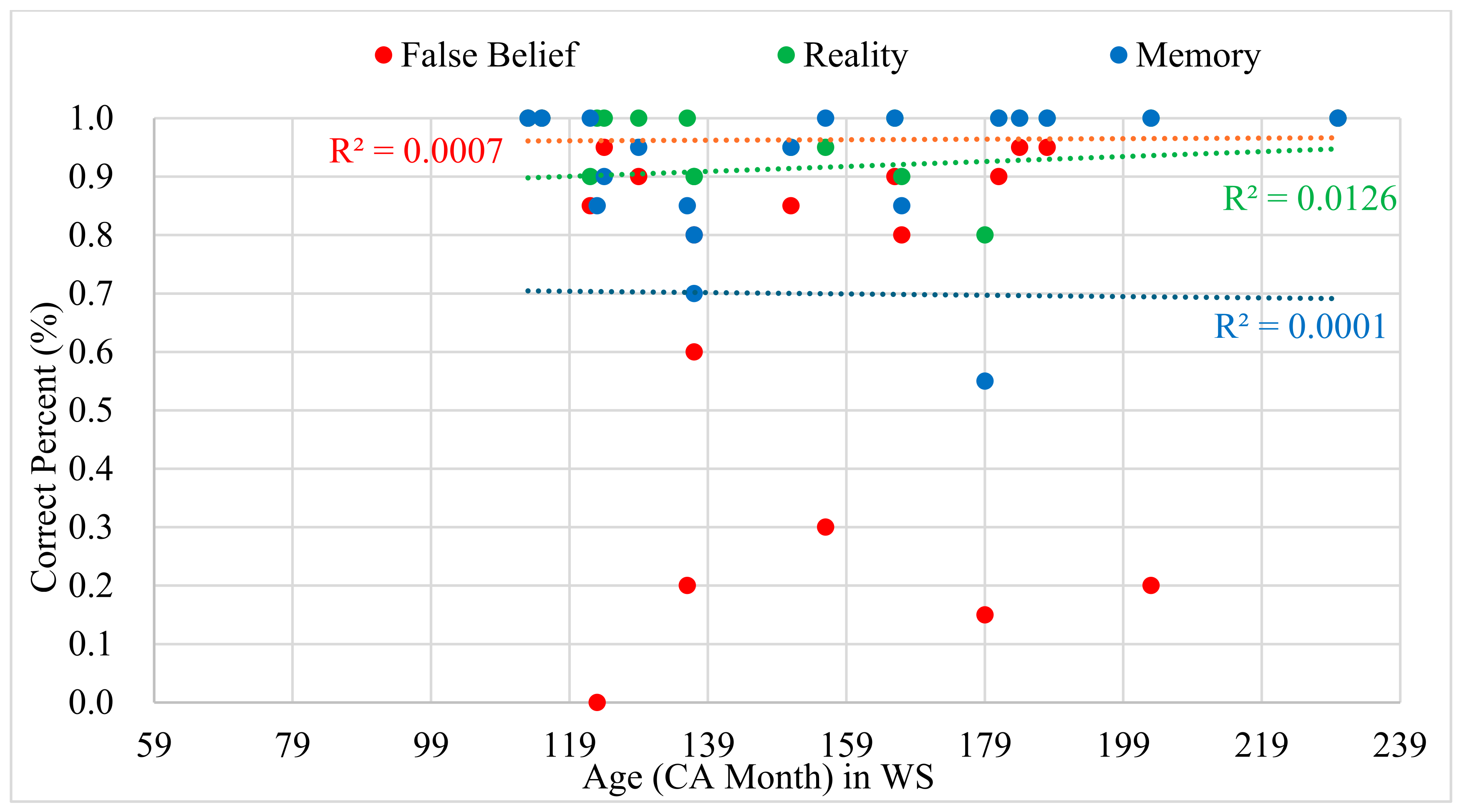

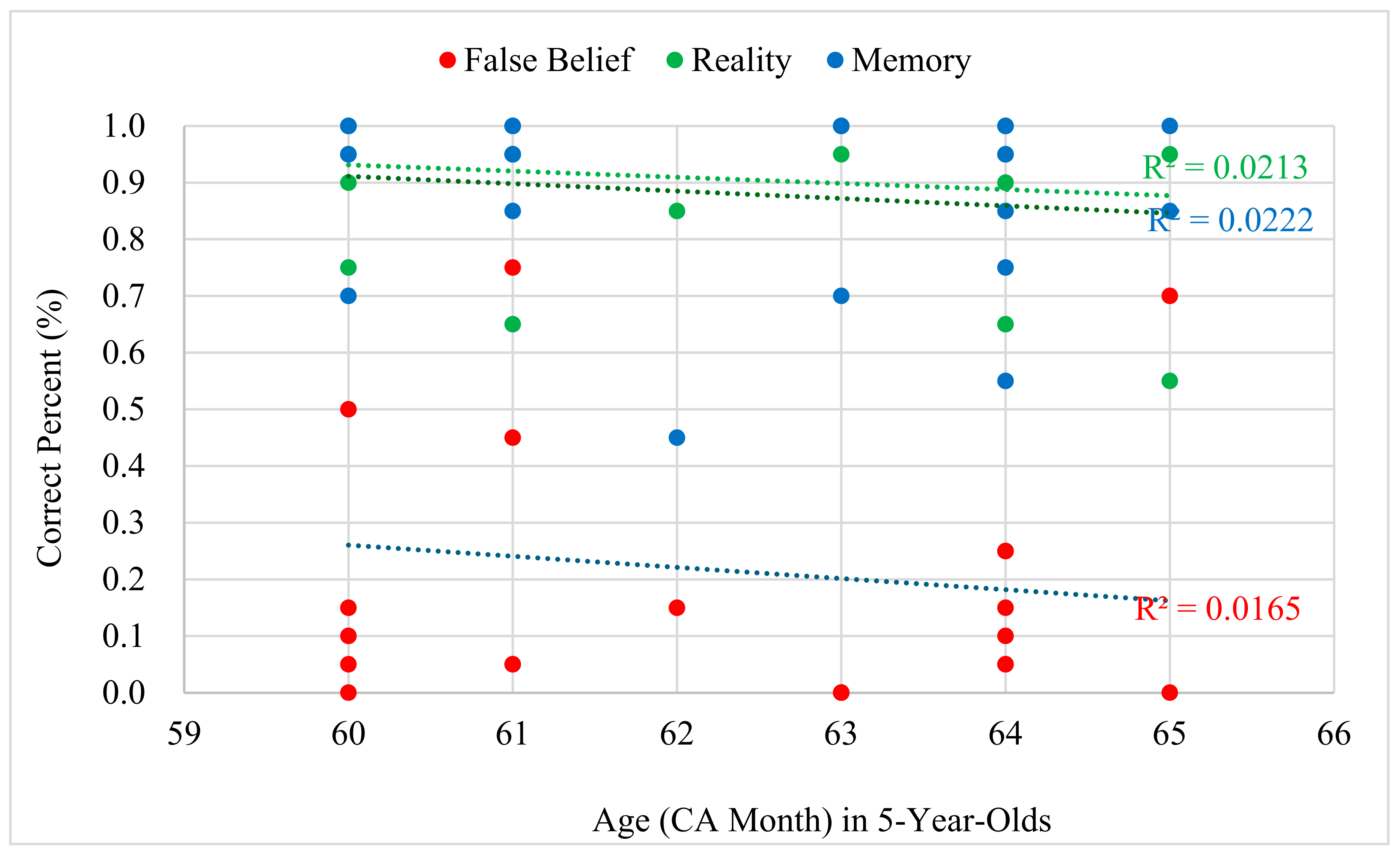

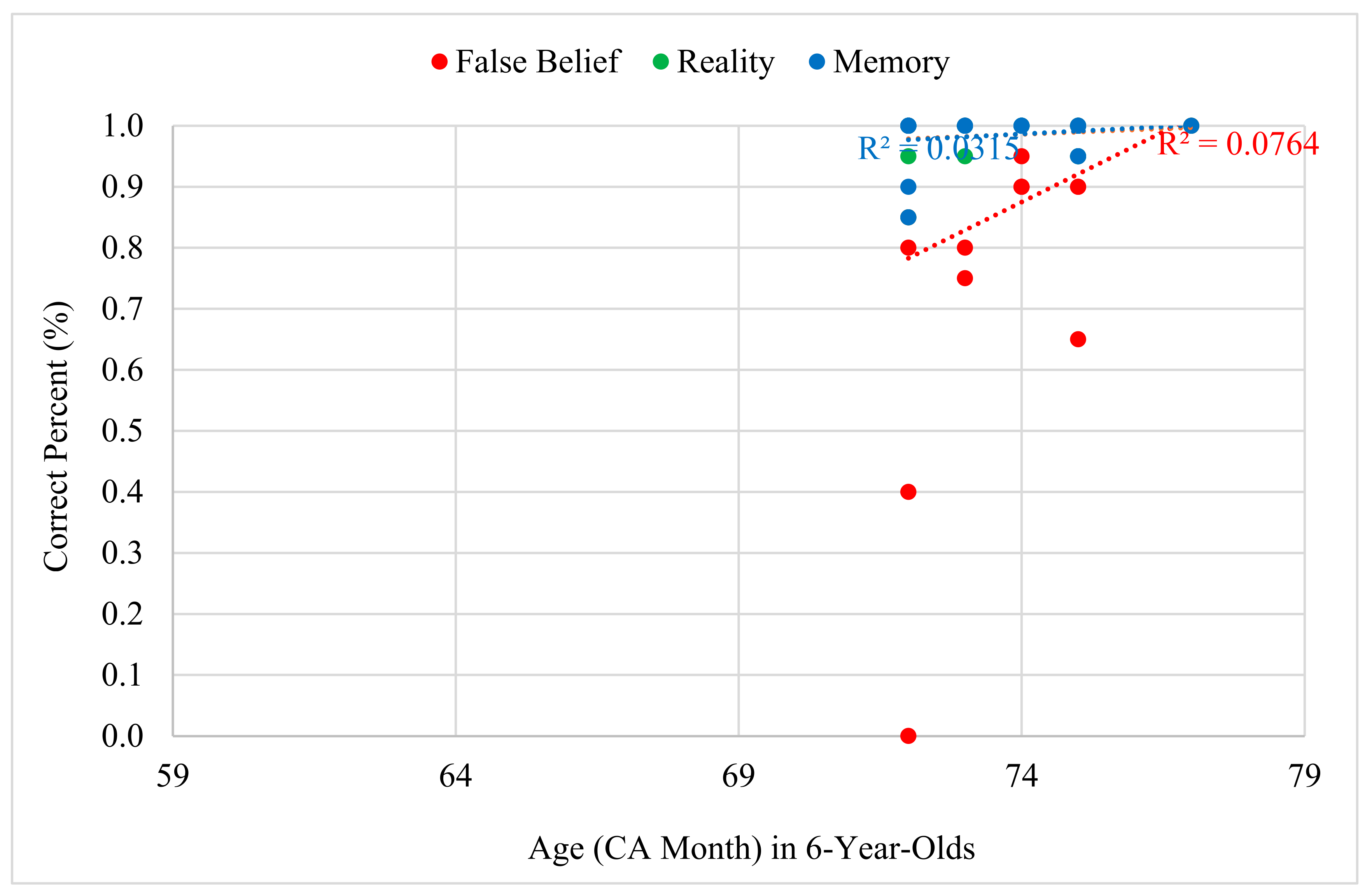

Analyses of Developmental Trajectories

To further discover the developmental trajectories of second-order false belief comprehension in people with WS, age-matched controls with typical development, and 5-to 6-year-old children, regression analyses of the correct responses with age to different questions were performed. The results showed no correlation in any group, which suggested that age was not a predictor of responses to second-order false-belief questions. Among the analyses, the MA and CA groups were almost at the ceiling for all the questions, which included the second-order false belief test. Only people with WS and control groups at 5 to 6-year-olds showed various percentage of correctness with age.

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 illustrate the graphs depicting the trends of developmental trajectories of the changed groups.

Discussion

This study investigated the ability of second-order false belief among people with WS. With the invention of computerized assisted testing materials, people with WS exhibited enhanced ability of mentalizing others’ minds. Instead of traditional 2D presentations as materials, this study used 3D animations. A cause of the enhancement could rely on a clear presentation of actions depicted in scenarios of location change shown in 3D animations related to second-order false-belief tasks. Since it was impossible for traditional 2D presentation of any false-belief tasks to clearly act out the protagonists’ actions, people with WS could not comprehend the meaning of the pictures related to the inference of the second-order false belief. Another possibility was the threshold of age passing the second-order false belief of people with WS. Their mental age ranged from 6.2–15.2 years in this study. Hence, the minimum age to pass the second-order false belief among people with WS was at least the same as the critical age of healthy controls aged 6 years. Though actual age passed the second-order false belief was 7.14 years of age. People with WS recruited in Sullivan and Tager-Flusberg’s study (1999) had a mental age range of 4.67–15.5 years. In their study, people with WS at the minimum age were unable to pass the second-order false-belief tasks, which was another possible reason why people with WS did not outperform people with PWS and NMR. Our study met the criteria of passing age to second-order false beliefs at 6 years old in people with WS, as revealed by the healthy controls. This finding confirmed that with the use of computerized-assisted testing materials as animations, people with WS could pass the second-order false-belief tasks. Our study contributes to the field of neurodevelopmental disorders as it provides evidence on the use of advanced technology as appropriate testing materials. Our study also challenges previous studies that used traditional 2D testing materials to probe the ability of false-belief tasks in people with WS and other neurodevelopmental disabilities. This study contributes to the invention of advanced technology to enhance the mentalizing ability of people with WS.

Our finding of a high passing rate to second-order false-belief tasks in people with WS at 6 years old similar to the controls with typical development provides evidence for the hypothesis of asymmetrical brain and behavioral performance in people with WS (Hsu & Chen, 2014; Hsu et al., 2007). The hypothesis indicates neuroplasticity in people with neurodevelopmental disabilities, although neuro-constructivism argues devastating influence of early gene mutations in people with neurodevelopmental disabilities on later development. People with WS are impaired at chromosome 7 with severe mental retardation and delayed cognitive development. However, their behavior could be normal considering atypical neurological mechanism. Hsu et al. (2007) used a false memory paradigm to examine the ability of concept formation in people with WS and revealed that they formed gist themes behaviorally similar to the CA controls. However, they were neurologically deviant. Moreover, Hsu and Chen (2014) investigated the face processing ability of people with WS and found that they could detect configure-changed and feature-changed faces from model faces similar to the CA controls behaviorally. However, they showed distinct patterns at the neurological level. The CA controls processed configure-changed and model faces without a difference in the right hemisphere. Conversely, people with WS processed configure-changed faces as feature-changed faces. These findings suggested that people with WS processed configure-changed faces via the processing strategy of feature-changed faces. These results were consistent with the cognitive style of local processing of people with WS. These studies confirmed the hypothesis of an asymmetrical brain and behavioral performances in people with neurodevelopmental disabilities. This supported neural plasticity in people with neurodevelopmental disabilities. Future studies should conduct neural imaging or brainwave-related experiments and determine the underlying mechanism in the processing of the second-order false beliefs in people with WS.

The hypersocial personality of people with WS was characterized by proficient facial processing, fluent language, and affective expressions. This characterization led to the hypothesis of the social module (Karmiloff-Smith et al., 1995). This module was proposed to account for the hypersocial ability of people with WS who were smooth in interpersonal interaction and frequently initiated conversations. This hypothesis was also compatible with the concept of social brain, which was built on empathy intertwined with morality and justice (Chen et al., 2018). The ability of empathy was related to the theory of mind, which mentalized others’ minds. Among the ability of the theory mind, first-order false belief mentalizing ability developed at approximately 5.9 years of age (Hsu & Rao, 2023). Furthermore, based on this study, people with WS developed advanced complex second-order false belief mentalizing abilities from the age of 7.14 years via 3D animation clips. Put together, people with WS delayed their mentalizing abilities a maximum of 1.9 years to the first-order inferences and 1.14 years to the second-order inferences. However, the extent to which people with WS reflect social brain warrants further investigation at both the behavioral and neurological levels.

References

- Chen, C. Y., Martinez, R. M., & Cheng, Y. W. (2018). The developmental origins of the social brain: Empathy, morality, and justice. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2584.

- Frith, U. (1989). Autism: Explaining the Enigma. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Hsu, C.F. (2013). Contextual Integration of Causal Coherence in People with Williams Syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(10), 3332–3342.

- Hsu, C. F. & Chen, J. Y. (2014). Deviant Neural Correlates of Configural Detection in Facial Processing of People with Williams Syndrome. Bulletin of Special Education, 39(1), 61–84.

- Hsu, C. F., Karmiloff-Smith, A., Tzeng, O., Chin, R. T., & Wang, H. C. (2007). Semantic Knowledge in Williams Syndrome: Insights from Comparing Behavioural and Brain Processes in False Memory Tasks. Proceedings of the 6th IEEE International Conference on Development and Learning, 6, 48–52.

- Hsu, C. F., & Rao, S. Y. (2023). Computerized False Belief Tasks Impact Mentalizing Ability in People with Williams Syndrome. Brain Sciences: insight into the ability of language understanding and writing in neurodevelopmental disorders (special issue Developmental Neuroscience section), 13, 72.

- Karmiloff-Smith, A., Klima, E., Bellugi, U., Grant, J., & Baron-Cohen, S. (1995). Is there a social module? Language, face processing, and theory of mind in individuals with Williams syndrome. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 7(2), 196–208.

- Perner, J., & Wimmer, H. (1985). “John thinks that Mary thinks that…”: Attribution of second-order beliefs by 5- to 10-year-old children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 39(3), 437–471.

- Sullivan, K., & Tager-Flusberg, H. (1999). Second-order belief attribution in Williams syndrome: intact or impaired? American journal of mental retardation, 104(6), 523–532.

- Tager-Flusberg, H., Boshart, J., & Baron-Cohen, S. (1998). Reading the windows to the soul: Evidence of domain-specific sparing in Williams syndrome. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 10(5), 631–639.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).