Submitted:

24 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

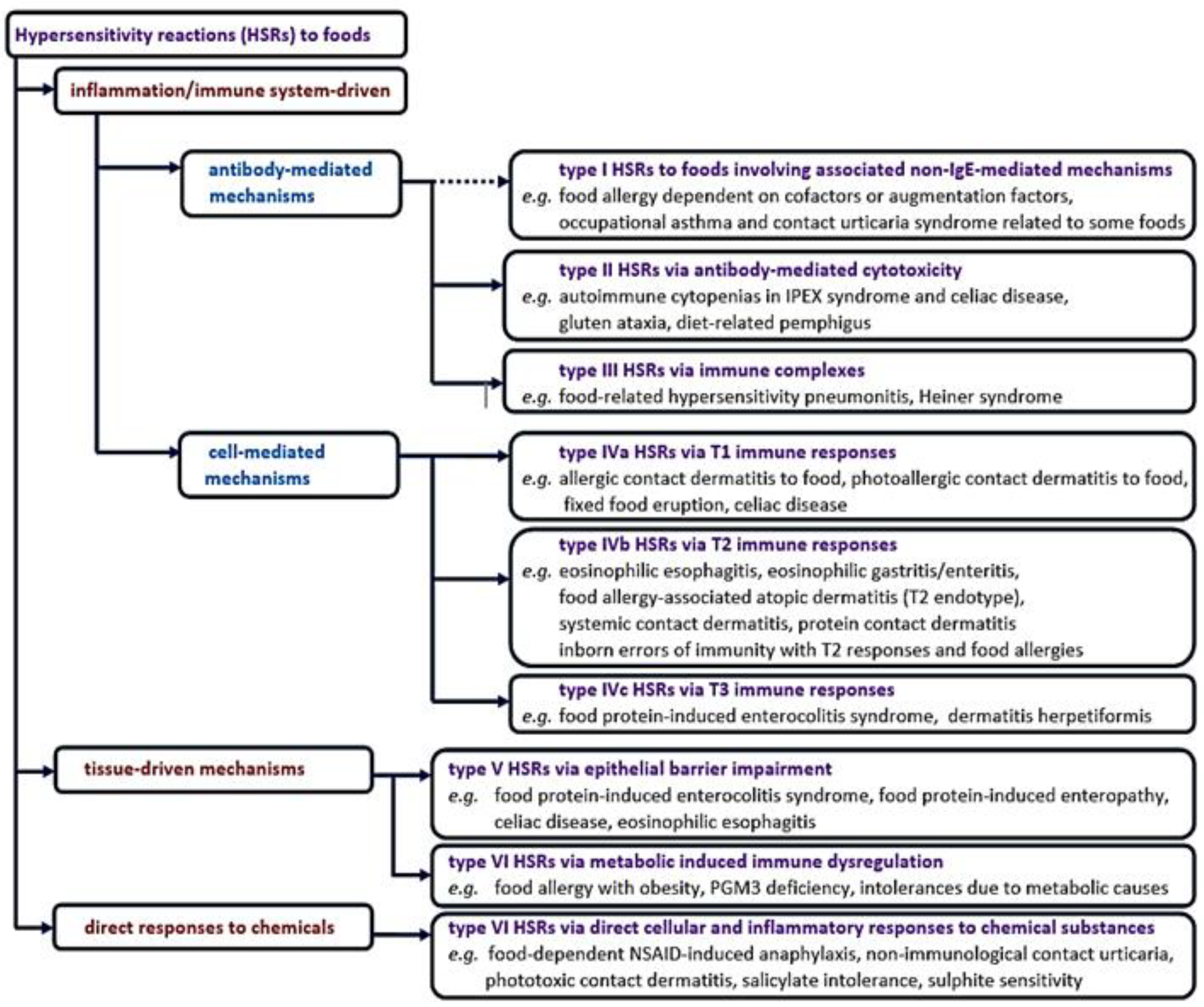

2. Classification of Hypersensitivity Reactions to Foods Focused on Non-IgE Mediated Mechanisms

2.1. Type I Hypersensitivity Reactions to Foods Involving Associated non-IgE-Mediated Mechanisms

2.2. Type II Hypersensitivity Reactions via Antibody-Mediated Cytotoxicity

2.3. Type III Hypersensitivity Reactions via Immune Complexes

2.4. Type IV Hypersensitivity Reactions via Cell-Mediated Mechanisms

2.4.1. Type IVa via T1 Immune Responses

2.4.2. Type IVb via T2 Immune Responses

2.4.3. Type IVc via T3 Immune Responses

2.5. Type V Tissue-Driven Hypersensitivity Reactions via Epithelial Barrier Impairment

2.6. Type VI Tissue-Driven Hypersensitivity Reactions via Metabolic-Induced Immune Dysregulation

2.7. Type VII Hypersensitivity Reactions via Direct Cellular and Inflammatory Responses to Chemical Substances

3. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jutel, M.; Agache, I.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M.; Akdis, M.; Chivato, T.; Del Giacco, S.; Gajdanowicz, P.; Gracia, I.E.; Klimek, L.; Lauerma, A. , et al. Nomenclature of allergic diseases and hypersensitivity reactions: Adapted to modern needs: An EAACI position paper. Allergy 2023, 78, 2851–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.N.; Xiang, L. Interpretation of 2023 EAACI guidelines on the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy. Zhonghua Yu Fang Yi Xue Za Zhi 2024, 58, 735–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, A.F.; Riggioni, C.; Agache, I.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M.; Alvarez-Perea, A.; Alvaro-Lozano, M.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; Barni, S.; Beyer, K. , et al. EAACI guidelines on the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy. Allergy 2023, 78, 3057–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansson, S.G.; Hourihane, J.O.; Bousquet, J.; Bruijnzeel-Koomen, C.; Dreborg, S.; Haahtela, T.; Kowalski, M.L.; Mygind, N.; Ring, J.; van Cauwenberge, P. , et al. A revised nomenclature for allergy. An EAACI position statement from the EAACI nomenclature task force. Allergy 2001, 56, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ring, J.; Jutel, M.; Papadopoulos, N.; Pfaar, O.; Akdis, C. Provocative proposal for a revised nomenclature for allergy and other hypersensitivity diseases. Allergy 2018, 73, 1939–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid-Grendelmeier, P.; Simon, D.; Simon, H.U.; Akdis, C.A.; Wüthrich, B. Epidemiology, clinical features, and immunology of the "intrinsic" (non-IgE-mediated) type of atopic dermatitis (constitutional dermatitis). Allergy 2001, 56, 841–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollenberg, A.; Christen-Zäch, S.; Taieb, A.; Paul, C.; Thyssen, J.P.; de Bruin-Weller, M.; Vestergaard, C.; Seneschal, J.; Werfel, T.; Cork, M.J. , et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema task force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020, 34, 2717–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.; Chebar Lozinsky, A.; Fleischer, D.M.; Vieira, M.C.; Du Toit, G.; Vandenplas, Y.; Dupont, C.; Knibb, R.; Uysal, P.; Cavkaytar, O.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Shah, N.; Venter, C. Diagnosis and management of Non-IgE gastrointestinal allergies in breastfed infants—An EAACI Position Paper. Allergy 2020, 75, 14–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pat, Y.; Yazici, D.; D'Avino, P.; Li, M.; Ardicli, S.; Ardicli, O.; Mitamura, Y.; Akdis, M.; Dhir, R.; Nadeau, K.; et al. Recent advances in the epithelial barrier theory. Int Immunol 2024, 36, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, F.D. Molecular biomarkers for grass pollen immunotherapy. World J Methodol 2014, 4, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggioni, C.; Oton, T.; Carmona, L.; Du Toit, G.; Skypala, I.; Santos, A.F. Immunotherapy and biologics in the management of IgE-mediated food allergy: Systematic review and meta-analyses of efficacy and safety. Allergy 2024, 79, 2097–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.W.; Suwanpradid, J.; Kim, I.H.; Staats, H.F.; Haniffa, M.; MacLeod, A.S.; Abraham, S.N. Perivascular dendritic cells elicit anaphylaxis by relaying allergens to mast cells via microvesicles. Science 2018, 362, eaao0666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.V.; Suresh, R.V.; Dispenza, M.C. Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibition for the treatment of allergic disorders. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2024, 133, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peavy, R.D.; Metcalfe, D.D. Understanding the mechanisms of anaphylaxis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2008, 8, 310–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeebhay, M.F.; Moscato, G.; Bang, B.E.; Folletti, I.; Lipińska-Ojrzanowska, A.; Lopata, A.L.; Pala, G.; Quirce, S.; Raulf, M.; Sastre, J.; et al. Food processing and occupational respiratory allergy - An EAACI position paper. Allergy 2019, 74, 1852–1871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popescu, F.D. Cross-reactivity between aeroallergens and food allergens. World J Methodol 2015, 5, 31–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benedé, S.; Garrido-Arandia, M.; Martín-Pedraza, L.; Bueno, C.; Díaz-Perales, A.; Villalba, M. Multifactorial modulation of food-induced anaphylaxis. Front Immunol 2017, 8, 552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortz, C.G.; Eller, E.; Garvik, O.S.; Kjaer, H.F.; Zuberbier, T.; Bindslev-Jensen, C. Challenge-verified thresholds for allergens mandatory for labeling: How little is too much for the most sensitive patient? Allergy 2024, 79, 1306–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spolidoro, G.C.I.; Ali, M.M.; Amera, Y.T.; Nyassi, S.; Lisik, D.; Ioannidou, A.; Rovner, G.; Khaleva, E.; Venter, C.; van Ree, R.; et al. Prevalence estimates of eight big food allergies in Europe: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2023, 78, 2361–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, 2024. Updated May 2024. Available from: https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/GINA-2024-Strategy-Report-24_05_22_WMS.pdf (Accessed 8 September 2024).

- Chiang, V.; Mak, H.W.F.; Yeung, M.H.Y.; Kan, A.K.C.; Au, E.Y.L.; Li, P.H. Epidemiology, outcomes, and disproportionate burden of food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis from the Hong Kong Multidisciplinary Anaphylaxis Management Initiative (HK-MAMI). J Allergy Clin Immunol Glob 2023, 2, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulthanan, K.; Ungprasert, P.; Jirapongsananuruk, O.; Rujitharanawong, C.; Munprom, K.; Trakanwittayarak, S.; Pochanapan, O.; Panjapakkul, W.; Maurer, M. Food-Dependent Exercise-Induced Wheals/Angioedema, Anaphylaxis, or Both: A Systematic Review of Phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2023, 11, 1926–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preda, M.; Popescu, F.D.; Vassilopoulou, E.; Smolinska, S. Allergenic Biomarkers in the Molecular Diagnosis of IgE-Mediated Wheat Allergy. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 8210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scala, E.; Villella, V.; Asero, R. Food-dependent exercise-induced allergic reactions in Lipid Transfer Protein (LTP) hypersensitive subjects: new data and a critical reappraisal. Eur Ann Allergy Clin Immunol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, T.; Olivieri, B.; Skypala, I.J. Food-triggered anaphylaxis in adults. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2024, 24, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, K. Food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis: The need for better understanding and management of the disease. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2022, 14, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñoz-Cano, R.; San Bartolome, C.; Casas-Saucedo, R.; Araujo, G.; Gelis, S.; Ruano-Zaragoza, M.; Roca-Ferrer, J.; Palomares, F.; Martin, M.; Bartra, J. , et al. Immune-mediated mechanisms in cofactor-dependent food allergy and anaphylaxis: Effect of cofactors in basophils and mast cells. Front Immunol 2021, 11, 623071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherf, K.A.; Lindenau, A.C.; Valentini, L.; Collado, M.C.; García-Mantrana, I.; Christensen, M.; Tomsitz, D.; Kugler, C.; Biedermann, T.; Brockow, K. Cofactors of wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis do not increase highly individual gliadin absorption in healthy volunteers. Clin Transl Allergy 2019, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Cano, R.; Pascal, M.; Bartra, J.; Picado, C.; Valero, A.; Kim, D.K.; Brooks, S.; Ombrello, M.; Metcalfe, D.D.; Rivera, J.; Olivera, A. Distinct transcriptome profiles differentiate nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-dependent from nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-independent food-induced anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016, 137, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldo, B.A.; Pham, N.H. Opioid toxicity: histamine, hypersensitivity, and MRGPRX2. Arch Toxicol 2023, 97, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauppila, G.R.; Eagen, K.V. Opioid Use Disorder from Poppy Seed Tea Use: A Case Report. Am J Case Rep 2023, 24, e938675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalczyk, A.; Kuczyńska, R.; Żbikowska-Gotz, M.; Bartuzi, Z.; Krogulska, A. Anaphylaxis in an 8-Year-Old Boy Following the Consumption of Poppy Seed. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol 2020, 30, 288–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podzhilkova, A.; Nagl, C.; Hummel, K.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Eller, E.; Mortz, C.G.; Bublin, M.; Hoffmann-Sommergruber, K. Poppy Seed Allergy: Molecular Diagnosis and Cross-Reactivity With Tree Nuts. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2024, 12, 2144–2154.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Borges, M.; Fernández-Caldas, E.; Capriles-Hulett, A.; Caballero-Fonseca, F. Mite-induced inflammation: More than allergy. Allergy Rhinol (Providence) 2012, 3, e25–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Borges, M.; Suárez Chacón, R.; Capriles-Hulett, A.; Caballero-Fonseca, F.; Fernández-Caldas, E. Anaphylaxis from ingestion of mites: pancake anaphylaxis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013, 131, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werfel, T.; Asero, R.; Ballmer-Weber, B.K.; Beyer, K.; Enrique, E.; Knulst, A.C.; Mari, A.; Muraro, A.; Ollert, M.; Poulsen, L.K. , et al. Position paper of the EAACI: food allergy due to immunological cross-reactions with common inhalant allergens. Allergy 2015, 70, 1079–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darsow, U.; Gelincik, A.; Jappe, U.; Platts-Mills, T.A.; Ünal, D.; Biedermann, T. Algorithms in allergy: An algorithm for alpha-Gal syndrome diagnosis and treatment, 2024 update. Allergy 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, F.D.; Cristea, O.M.; Ionica, F.E.; Vieru, M. Drug allergies due to IgE sensitization to α-Gal. Farmacia 2019, 67, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikemoto, C.; Tamagawa-Mineoka, R.; Masuda, K.; Iida, S.; Inomata, N.; Katoh, N. Immediate-onset anaphylaxis of Bacillus subtilis-fermented soybeans (natto). J Dermatol 2014, 41, 857–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inomata, N.; Chin, K.; Aihara, M. Anaphylaxis caused by ingesting jellyfish in a subject with fermented soybean allergy: possibility of epicutaneous sensitization to poly-gamma-glutamic acid by jellyfish stings. J Dermatol 2014, 41, 752–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopata AL, Jeebhay MF. Airborne seafood allergens as a cause of occupational allergy and asthma. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2013, 13, 288–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, A.K.; Seternes, O.M.; Larsen, M.; Kishimur, H.; Rudenskaya, G.N.; Bang, B. Purified sardine and king crab trypsin display individual differences in PAR-2-, NF-κB-, and IL-8 signaling. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2011, 93, 1991–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pougnet, R.; Loddé, B.; Lucas, D.; Jégaden, D.; Bell, S.; Dewitte, J.D. A case of occupational asthma from metabisulphite in a fisherman. Int. Marit. Health 2010, 62, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Smit, L.A.; Wouters, I.M.; Hobo, M.M.; Eduard, W.; Doekes, G.; Heederik, D. Agricultural seed dust as a potential cause of organic dust toxic syndrome. Occup. Environ. Med. 2006, 63, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaro, C.; Goossens, A. Immunological occupational contact urticaria and contact dermatitis from proteins: a review. Contact Dermatitis 2008, 58, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaccio, R.R.; Alvarez, M.S. Contact allergy to food. Dermatol. Ther. 2004, 17, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giménez-Arnau, A.M.; Pesqué, D.; Maibach, H.I. Contact Urticaria Syndrome: a comprehensive review. Curr. Dermatol. Rep. 2022, 11, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, A.; Seegräber, M.; Wollenberg, A. Food-related contact dermatitis, contact urticaria, and atopy patch test with food. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 56, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashbaugh, A.G.; Abel, M.K.; Murase, J.E. Protein causes of urticaria and dermatitis. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 2021, 41, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vethachalam, S. Persaud, Y. Contact Urticaria. [Updated 2023 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549890/.

- Bajwa, S.F.; Mohammed, R.H. Type II hypersensitivity reaction. [Updated 2023 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563264.

- Dispenza, M.C. Classification of hypersensitivity reactions. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2019, 40, 470–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justiz Vaillant, A.A.; Vashisht, R.; Zito, P.M. Immediate hypersensitivity reactions (Archived). 2023 May 29. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan–. [PubMed]

- Husebye, E.S.; Anderson, M.S.; Kämpe, O. Autoimmune polyendocrine syndromes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampasona, V.; Passerini, L.; Barzaghi, F.; Lombardoni, C.; Bazzigaluppi, E.; Brigatti, C.; Bacchetta, R.; Bosi, E. Autoantibodies to harmonin and villin are diagnostic markers in children with IPEX syndrome. PLoS One 2013, 8, e78664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.H.; Lee, K.H.; Jeon, B.; Ochs, H.D.; Lee, J.S.; Gee, H.Y.; Seo, S.; Geum, D.; Piccirillo, C.A.; Eisenhut, M.; van der Vliet, H.J.; Lee, J.M.; Kronbichler, A.; Ko, Y.; Shin, J.I. Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome: a systematic review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2020, 19, 102526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torgerson, T.R.; Linane, A.; Moes, N.; Anover, S.; Mateo, V.; Rieux-Laucat, F.; Hermine, O.; Vijay, S.; Gambineri, E.; Cerf-Bensussan, N.; Fischer, A.; et al. Severe food allergy as a variant of IPEX syndrome caused by a deletion in a noncoding region of the FOXP3 gene. Gastroenterology 2007, 132, 1705–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbsky, J.W.; Chatila, T.A. Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) and IPEX-related disorders: an evolving web of heritable autoimmune diseases. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2013, 25, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altintas, A.; Pasa, S.; Cil, T.; Bayan, K.; Gokalp, D.; Ayyildiz, O. Thyroid and celiac diseases autoantibodies in patients with adult chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Platelets 2008, 19, 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisgin, T.; Yarali, N.; Duru, F.; Usta, B.; Kara, A. Hematologic manifestation of childhood celiac disease. Acta Haematol. 2004, 111, 211–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarina, A.; Marinoni, M.; Lassandro, G.; Saracco, P.; Perrotta, S.; Facchini, E.; Notarangelo, L.D.; Russo, G.; Giordano, P.; Romano, F.; et al. Association of immune thrombocytopenia and celiac disease in children: a retrospective case control study. Turk. J. Haematol. 2021, 38, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjivassiliou, M.; Aeschlimann, P.; Sanders, D.S.; Mäki, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Grünewald, R.A.; Bandmann, O.; Woodroofe, N.; Haddock, G.; Aeschlimann, D.P. Transglutaminase 6 antibodies in the diagnosis of gluten ataxia. Neurology 2013, 80, 1740–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadjivassiliou, M.; Davies-Jones, G.A.; Sanders, D.S.; Grünewald, R.A. Dietary treatment of gluten ataxia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003, 74, 1221–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauret, E.; Rodrigo, L. Celiac disease and autoimmune-associated conditions. Biomed Res Int. 2013, 2013, 127589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapone, A.; Bai, J.C.; Ciacci, C.; Dolinsek, J.; Green, P.H.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Kaukinen, K.; Rostami, K.; Sanders, D.S.; Schumann, M.; et al. Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: consensus on new nomenclature and classification. BMC Med. 2012, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Todd, P.K.; Shakkottai, V.G. Overview of cerebellar ataxia in adults. In: Hurtig, H.I., ed. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Updated August 5, 2024. Available online: www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-cerebellar-ataxia-in-adults (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Brenner, S.; Goldberg, I. Drug-induced pemphigus. Clin Dermatol. 2011, 29, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brenner, S.; Ruocco, V.; Ruocco, E.; Russo, A.; Tur, E.; Luongo, V.; Lombardi, M.L. In vitro tannin acantholysis. Int J Dermatol. 2000, 39, 738–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halil Yavuz, I.; Ozaydın Yavuz, G. The role of pentraxin 3 in pemphigus vulgaris. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2020, 37, 503–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertl, M.; Sitaru, C. Pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and diagnosis of pemphigus. In: Zone, J.J., ed. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Updated January 25, 2024. Available online: www.uptodate.com/contents/pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-of-pemphigus (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Ruocco, V.; Brenner, S.; Ruocco, E. Pemphigus and diet: does a link exist? Int J Dermatol. 2001, 40, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, N.; Annamaraju, P. Type III Hypersensitivity Reaction. [Updated 2023 May 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available online: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559122/.

- Costabel, U.; Miyazaki, Y.; Pardo, A.; Koschel, D.; Bonella, F.; Spagnolo, P.; Guzman, J.; Ryerson, C.J.; Selman, M. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020, 6, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, T.E. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (extrinsic allergic alveolitis): Epidemiology, causes, and pathogenesis. In: Flaherty, K.R., Ed. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. Updated August 01, 2023. Available online: www.uptodate.com/contents/hypersensitivity-pneumonitis-extrinsic-allergic-alveolitis-epidemiology-causes-and-pathogenesis (Accessed 8 September 2024).

- Kongsupon, N.; Walters, G.I.; Sadhra, S.S. Occupational causes of hypersensitivity pneumonitis: a systematic review and compendium. Occup Med 2021, 71, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirce, S.; Vandenplas, O.; Campo, P.; Cruz, M.J.; de Blay, F.; Koschel, D.; Moscato, G.; Pala, G.; Raulf, M.; Sastre, J.; Siracusa, A.; Tarlo, S.M.; Walusiak-Skorupa, J.; Cormier, Y. Occupational hypersensitivity pneumonitis: an EAACI position paper. Allergy 2016, 71, 765–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, M.; Pardo, A.; King, T.E., Jr. Hypersensitivity pneumonitis: insights in diagnosis and pathobiology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012, 186, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arasi, S.; Mastrorilli, C.; Pecoraro, L.; Giovannini, M.; Mori, F.; Barni, S.; Caminiti, L.; Castagnoli, R.; Liotti, L.; Saretta, F. , et al. Heiner Syndrome and Milk Hypersensitivity: An Updated Overview on the Current Evidence. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.L.; Sicherer, S.H. Classification of adverse food reactions. J Food Allergy 2020, 2, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Park, M.; Jung, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Hahn, S.M.; Kim, S.; Lee, M.J.; Shim, H.S.; Sohn, M.H.; Kim, K.W.; Kim, M.J. Children with Heiner Syndrome: A Single-Center Experience. Children 2021, 8, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aquino, M.; Rosner, G. Systemic Contact Dermatitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2019, 56, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Killig, C.; Werfel, T. Contact reactions to food. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2008, 8, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas-Muñoz, E.; Lepoittevin, J.P.; Pujol, R.M.; Giménez-Arnau, A. Allergic contact dermatitis to plants: understanding the chemistry will help our diagnostic approach. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2012, 103, 456–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, C.; Mauro, M.; Belloni Fortina, A.; Giulioni, E.; Larese Filon, F. Occupational Contact Dermatitis in Food Handlers: A 26-Year Retrospective Multicentre Study in North-East Italy (Triveneto Group on Research on Contact Dermatitis). Dermatitis 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.L.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Peeva, E. Role of Innate Immunity in Allergic Contact Dermatitis: An Update. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 12975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Leonard, A.; Guttman-Yassky, E. The Unique Molecular Signatures of Contact Dermatitis and Implications for Treatment. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2019, 56, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brites, G.S.; Ferreira, I.; Sebastião, A.I.; Silva, A.; Carrascal, M.; Neves, B.M.; Cruz, M.T. Allergic contact dermatitis: From pathophysiology to development of new preventive strategies. Pharmacol Res. 2020, 162, 105282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheinman, P.L.; Vocanson, M.; Thyssen, J.P.; Johansen, J.D.; Nixon, R.L.; Dear, K.; Botto, N.C.; Morot, J.; Goldminz, A.M. Contact dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021, 7, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipinda, I.; Hettick, J.M.; Siegel, P.D. Haptenation: chemical reactivity and protein binding. J Allergy (Cairo) 2011, 2011, 839682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepoittevin, J.P.; Berl, V.; Giménez-Arnau, E. Alpha-methylene-gamma-butyrolactones: versatile skin bioactive natural products. Chem Rec 2009, 9, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, D.W.; Benezra, C. Quantitative structure-activity relationships for skin sensitization potential of urushiol analogues. Contact Dermatitis 1993, 29, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukakul, T.; Bruze, M.; Svedman, C. Fragrance Contact Allergy—A Review Focusing on Patch Testing. Acta Derm Venereol 2024, 104, adv40332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeem, M.; Kader, H.; Kerstan, A.; Hetta, H.F.; Serfling, E.; Goebeler, M.; Muhammad, K. Intricate Relationship Between Adaptive and Innate Immune System in Allergic Contact Dermatitis. Yale J Biol Med 2020, 93, 699–709. [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto, E.; Katahira, Y.; Mizoguchi, I.; Watanabe, A.; Furusaka, Y.; Sekine, A.; Yamagishi, M.; Sonoda, J.; Miyakawa, S.; Inoue, S. , et al. Chemical- and Drug-Induced Allergic, Inflammatory, and Autoimmune Diseases Via Haptenation. Biology 2023, 12, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksic, M.; Rajagopal, R.; de-Ávila, R.; Spriggs, S.; Gilmour, N. The skin sensitization adverse outcome pathway: exploring the role of mechanistic understanding for higher tier risk assessment. Crit Rev Toxicol 2024, 54, 69–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Neves, C.; Gibbs, S. Progress on Reconstructed Human Skin Models for Allergy Research and Identifying Contact Sensitizers. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2021, 430, 103–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhingra, N.; Shemer, A.; Correa da Rosa, J.; Rozenblit, M.; Fuentes-Duculan, J.; Gittler, J.K.; Finney, R.; Czarnowicki, T.; Zheng, X.; Xu, H.; et al. Molecular profiling of contact dermatitis skin identifies allergen-dependent differences in immune response. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014, 134, 362–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcain, J.; Infante Cruz, A.D.P.; Barrientos, G.; Vanzulli, S.; Salamone, G.; Vermeulen, M. Mechanisms of unconventional CD8 Tc2 lymphocyte induction in allergic contact dermatitis: Role of H3/H4 histamine receptors. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 999852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afvari, S.; Zippin, J.H. Type I hypersensitivity in photoallergic contact dermatitis. JAAD Case Rep 2023, 44, 47–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheman, A.; Gupta, S. Photoallergic contact dermatitis from diallyl disulfide. Contact Dermatitis 2001, 45, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahuja, K.; Issa, C.J.; Nedorost, S.T.; Lio, P.A. Is food-triggered atopic dermatitis a form of systemic contact dermatitis? Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2024, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil-Pallares, P.; Alvarez-Garcia, O.; González-Moure, C.; Castro-Murga, M.; Monteagudo-Sánchez, B. Fixed food eruption caused by Maja squinado (European spider crab) in a child. Contact Dermatitis 2020, 83, 510–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McWilliam, V.; Koplin, J.; Lodge, C.; Tang, M.; Dharmage, S.; Allen, K. The prevalence of tree nut allergy: A systematic review. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2015, 15, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, L.; Agarwal, R.; Chopra, A.; Mitra, B. A cross-sectional observational study of clinical spectrum and prevalence of fixed food eruption in a tertiary care hospital. Indian Dermatol Online J 2020, 11, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, T.; Berner, D.; Weigert, C.; Röcken, M.; Biedermann, T. Fixed food eruption caused by asparagus. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005, 116, 1390–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lania, G.; Nanayakkara, M.; Maglio, M.; Auricchio, R.; Porpora, M.; Conte, M.; De Matteis, M.A.; Rizzo, R.; Luini, A.; Discepolo, V.; et al. Constitutive alterations in vesicular trafficking increase the sensitivity of cells from celiac disease patients to gliadin. Commun Biol 2019, 2, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiuri, L.; Villella, V.R.; Raia, V.; Kroemer, G. The gliadin-CFTR connection: New perspectives for the treatment of celiac disease. Ital J Pediatr 2019, 45, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, A.; Di Gioacchino, M.; Gammeri, L.; Inchingolo, R.; Chini, R.; Santilli, F.; Nucera, E.; Gangemi, S. The emerging role of innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) and alarmins in celiac disease: An update on pathophysiological insights, potential use as disease biomarkers, and therapeutic implications. Cells 2023, 12, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tye-Din, J.A.; Galipeau, H.J.; Agardh, D. Celiac disease: A review of current concepts in pathogenesis, prevention, and novel therapies. Front Pediatr 2018, 6, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, X.; Vargas, J.; Green, P.H.R.; Bhagat, G. Innate lymphoid cells and celiac disease: Current perspective. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 11, 803–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijelić, B.; Matić, I.Z.; Besu, I.; Janković, L.; Juranić, Z.; Marušić, S.; Andrejević, S. Celiac disease-specific and inflammatory bowel disease-related antibodies in patients with recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Immunobiology 2019, 224, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camarca, A.; Rotondi Aufiero, V.; Mazzarella, G. Role of regulatory T cells and their potential therapeutic applications in celiac disease. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 14434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cellier, C.; Patey, N.; Mauvieux, L.; Jabri, B.; Delabesse, E.; Cervoni, J.P.; Burtin, M.L.; Guy-Grand, D.; Bouhnik, Y.; Modigliani, R.; Barbier, J.P.; Macintyre, E.; Brousse, N.; Cerf-Bensussan, N. Abnormal intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes in refractory sprue. Gastroenterology 1998, 114, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halttunen, T.; Mäki, M. Serum immunoglobulin A from patients with celiac disease inhibits human T84 intestinal crypt epithelial cell differentiation. Gastroenterology 1999, 116, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husby, S.; Murray, J.A.; Katzka, D.A. AGA clinical practice update on diagnosis and monitoring of celiac disease—changing utility of serology and histologic measures: Expert review. Gastroenterology 2019, 156, 885–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Görög, A.; Antiga, E.; Caproni, M.; Cianchini, G.; De, D.; Dmochowski, M.; Dolinsek, J.; Drenovska, K.; Feliciani, C.; Hervonen, K.; et al. S2k guidelines (consensus statement) for diagnosis and therapy of dermatitis herpetiformis initiated by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2021, 35, 1251–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furue, M. Regulation of Skin Barrier Function via Competition between AHR Axis versus IL-13/IL-4‒JAK‒STAT6/STAT3 Axis: Pathogenic and Therapeutic Implications in Atopic Dermatitis. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, I.H.; Chung, W.H.; Wu, P.C.; Chen, C.B. JAK-STAT signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis: An updated review. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 1068260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogame, T.; Egawa, G.; Kabashima, K. Exploring the role of Janus kinase (JAK) in atopic dermatitis: a review of molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Immunol Med 2023, 46, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upadhyay, P.R.; Seminario-Vidal, L.; Abe, B.; Ghobadi, C.; Sims, J.T. Cytokines and Epidermal Lipid Abnormalities in Atopic Dermatitis: A Systematic Review. Cells 2023, 12, 2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasserer, S.; Jargosch, M.; Mayer, K.E.; Eigemann, J.; Raunegger, T.; Aydin, G.; Eyerich, S.; Biedermann, T.; Eyerich, K.; Lauffer, F. Characterization of High and Low IFNG-Expressing Subgroups in Atopic Dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 6158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, L.; D'Onghia, M.; Lazzeri, L.; Rubegni, G.; Cinotti, E. Blocking the IL-4/IL-13 Axis versus the JAK/STAT Pathway in Atopic Dermatitis: How Can We Choose? J Pers Med 2024, 14, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Ahn, K. Atopic dermatitis endotypes: knowledge for personalized medicine. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2022, 22, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyal, R.D.; Pavel, A.B.; Glickman, J.; Chan, T.C.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, N.; Cueto, I.; Peng, X.; Estrada, Y.; Fuentes-Duculan, J.; et al. Atopic dermatitis in African American patients is TH2/TH22-skewed with TH1/TH17 attenuation. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2019, 122, 99–110.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Leonard, A.; Pavel, A.B.; Malik, K.; Raja, A.; Glickman, J.; Estrada, Y.D.; Peng, X.; Del Duca, E.; Sanz-Cabanillas, J.; et al. Age-specific changes in the molecular phenotype of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019, 144, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esnault, S.; Kelly, E.A.; Johnson, S.H.; DeLain, L.P.; Haedt, M.J.; Noll, A.L.; Sandbo, N.; Jarjour, N.N. Matrix Metalloproteinase-9-Dependent Release of IL-1β by Human Eosinophils. Mediators Inflamm. 2019, 7479107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packi, K.; Matysiak, J.; Klimczak, S.; Matuszewska, E.; Bręborowicz, A.; Pietkiewicz, D.; Matysiak, J. Analysis of the Serum Profile of Cytokines Involved in the T-Helper Cell Type 17 Immune Response Pathway in Atopic Children with Food Allergy. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.O.; Kim, S.M.; Lee, K.H.; Bieber, T. Biomarkers for Phenotype-Endotype Relationship in Atopic Dermatitis: A Critical Review. EBioMedicine 2024, 103, 105121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renert-Yuval, Y.; Thyssen, J.P.; Bissonnette, R.; Bieber, T.; Kabashima, K.; Hijnen, D.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Biomarkers in Atopic Dermatitis—A Review on Behalf of the International Eczema Council. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 1174–1190.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutton, C.E.; Lalor, S.J.; Sweeney, C.M.; Brereton, C.F.; Lavelle, E.C.; Mills, K.H. Interleukin-1 and IL-23 Induce Innate IL-17 Production from γδ T Cells, Amplifying Th17 Responses and Autoimmunity. Immunity 2009, 31, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kido-Nakahara, M.; Onozuka, D.; Izuhara, K.; Saeki, H.; Nunomura, S.; Takenaka, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Kataoka, Y.; Fujimoto, R.; Kaneko, S.; et al. Exploring Patient Background and Biomarkers Associated with the Development of Dupilumab-Associated Conjunctivitis and Blepharitis. Allergol. Int. 2024, 73, 332–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolkhir, P.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M.; Bachert, C.; Bieber, T.; Canonica, G.W.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Metz, M.; Mullol, J.; Palomares, O.; Renz, H.; Ständer, S.; Zuberbier, T.; Maurer, M. Type 2 Chronic Inflammatory Diseases: Targets, Therapies and Unmet Needs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2023, 22, 743–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellon, E.S.; Gonsalves, N.; Abonia, J.P.; Alexander, J.A.; Arva, N.C.; Atkins, D.; Attwood, S.E.; Auth, M.K.H.; Bailey, D.D.; Biederman, L.; et al. International Consensus Recommendations for Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Nomenclature. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022, 20, 2474–2484.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Ruan, G.; Liu, S.; Xu, T.; Guan, K.; Li, J.; Li, J. Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Chin Med J (Engl) 2023, 136, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neely, J.L.; Reimers, A.; Taylor, S.; Garg, S.; Masuda, M.Y.; Schroeder, S.; Wright, B.L.; Doyle, A.D. GATA-3 and T-bet as Diagnostic Markers of Non-Esophageal Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease. Allergy 2022, 77, 1042–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greuter, T.; Straumann, A.; Fernandez-Marrero, Y.; Germic, N.; Hosseini, A.; Chanwangpong, A.; Yousefi, S.; Simon, D.; Collins, M.H.; Bussmann, C.; et al. A Multicenter Long-Term Cohort Study of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Variants and Their Progression to Eosinophilic Esophagitis Over Time. Clin Transl Gastroenterol 2024, 15, e00664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorge, A.; Aldinio, G.; Marinoni, B.; Visaggi, P.; Penagini, R.; Maniero, D.; Ghisa, M.; Marabotto, E.; de Bortoli, N.; Pasta, A.; Dipace, V.; Calabrese, F.; Vecchi, M.; Savarino, E.V.; Coletta, M. Distribution of Esophageal Inflammation in Patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Its Impact on Diagnosis and Outcome. Dig Liver Dis 2024, 56, S1590–S865800967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, B.; Troutman, T.D.; Schwartz, J.T. Breaking Down the Complex Pathophysiology of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2023, 130, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsohaibani, F.I.; Peedikayil, M.C.; Alzahrani, M.A.; Azzam, N.A.; Almadi, M.A.; Dellon, E.S.; Al-Hussaini, A.A. Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Current Concepts in Diagnosis and Management. Saudi J Gastroenterol 2024, 30, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cianferoni, A.; Shuker, M.; Brown-Whitehorn, T.; Hunter, H.; Venter, C.; Spergel, J.M. Food Avoidance Strategies in Eosinophilic Oesophagitis. Clin Exp Allergy 2019, 49, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ridolo, E.; Barone, A.; Ottoni, M.; Peveri, S.; Montagni, M.; Nicoletta, F. The New Therapeutic Frontiers in the Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Biological Drugs. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.M.; Santacroce, G.; Lenti, M.V.; di Sabatino, A. Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the Era of Biologics. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024, 18, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B.E.; Sacta, M.A.; Wright, B.L.; Spergel, J.; Wolfset, N. The Relationship Between Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Immunotherapy. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2024, 44, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franciosi, J.P.; Mougey, E.B.; Dellon, E.S.; Gutierrez-Junquera, C.; Fernandez-Fernandez, S.; Venkatesh, R.D.; Gupta, S.K. Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: History, Mechanisms, Efficacy, and Future Directions. J Asthma Allergy 2022, 15, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rochman, Y.; Kotliar, M.; Ben-Baruch Morgenstern, N.; Barski, A.; Wen, T.; Rothenberg, M.E. TSLP Shapes the Pathogenic Responses of Memory CD4+ T Cells in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Sci Signal 2023, 16, eadg6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greuter, T.; Straumann, A.; Fernandez-Marrero, Y.; Germic, N.; Hosseini, A.; Yousefi, S.; Simon, D.; Collins, M.H.; Bussmann, C.; Chehade, M.; et al. Characterization of Eosinophilic Esophagitis Variants by Clinical, Histological, and Molecular Analyses: A Cross-Sectional Multi-Center Study. Allergy 2022, 77, 2520–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odiase, E.; Zhang, X.; Chang, Y.; Nelson, M.; Balaji, U.; Gu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Pan, Z.; Spechler, S.J.; Souza, R.F. In Esophageal Squamous Cells From Eosinophilic Esophagitis Patients, Th2 Cytokines Increase Eotaxin-3 Secretion Through Effects on Intracellular Calcium and a Non-Gastric Proton Pump. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 2072–2088.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, T.; Iwamura, C.; Kiuchi, M.; Kurosugi, A.; Onoue, M.; Matsumura, T.; Chiba, T.; Nakayama, T.; Kato, N.; Hirahara, K. Amphiregulin-Producing TH2 Cells Facilitate Esophageal Fibrosis of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Glob 2024, 3, 100287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoda, T.; Wen, T.; Caldwell, J.M.; Ben-Baruch Morgenstern, N.; Osswald, G.A.; Rochman, M.; Mack, L.E.; Felton, J.M.; Abonia, J.P.; et al. Loss of Endothelial TSPAN12 Promotes Fibrostenotic Eosinophilic Esophagitis via Endothelial Cell-Fibroblast Crosstalk. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, J.M.; Collins, M.H.; Stucke, E.M.; Putnam, P.E.; Franciosi, J.P.; Kushner, J.P.; Abonia, J.P.; Rothenberg, M.E. Histologic Eosinophilic Gastritis Is a Systemic Disorder Associated with Blood and Extragastric Eosinophilia, TH2 Immunity, and a Unique Gastric Transcriptome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014, 134, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishihara, S.; Shoda, T.; Ishimura, N.; Ohta, S.; Ono, J.; Azuma, Y.; Okimoto, E.; Izuhara, K.; Nomura, I.; Matsumoto, K.; Kinoshita, Y. Serum Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis. Intern Med 2017, 56, 2819–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, G.; Visaggi, P.; Vassallo, M.; Fiocca, M.; Cremon, C.; Barbaro, M.R.; De Bortoli, N.; Bellini, M.; Stanghellini, V.; Savarino, E.V.; Barbara, G. Current and Novel Therapies for Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 15165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunkara, T.; Rawla, P.; Yarlagadda, K.S.; Gaduputi, V. Eosinophilic Gastroenteritis: Diagnosis and Clinical Perspectives. Clin Exp Gastroenterol 2019, 12, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troncone, R.; Discepolo, V. Colon in Food Allergy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009, 48 Suppl 2, S89–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuizen, N.; Herbert, D.R.; Brombacher, F.; Lopata, A.L. Differential Requirements for Interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13 in Protein Contact Dermatitis Induced by Anisakis. Allergy 2009, 64, 1309–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, A.; Yuki, T.; Takai, T.; Yokozeki, K.; Katagiri, A.; Takahashi, Y.; Yokozeki, H.; Basketter, D.; Sakaguchi, H. Epicutaneous Challenge with Protease Allergen Requires Its Protease Activity to Recall TH2 and TH17/TH22 Responses in Mice Pre-sensitized via Distant Skin. J Immunotoxicol 2021, 18, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, A.; Yuki, T.; Katagiri, A.; Lai, Y.T.; Takahashi, Y.; Basketter, D.; Sakaguchi, H. Proteolytic Activity Accelerates the TH17/TH22 Recall Response to an Epicutaneous Protein Allergen-Induced TH2 Response. J Immunotoxicol 2022, 19, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.; Gomułka, K.; Dziemieszonek, P.; Panaszek, B. Systemowe Kontaktowe Zapalenie Skóry [Systemic Contact Dermatitis]. Postepy Hig Med Dosw 2016, 70, 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, J.F.; Hammond, M.I.; Nedorost, S.T. Food Avoidance Diets for Dermatitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2015, 15, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burden, A.D.; Wilkinson, S.M.; Beck, M.H.; Chalmers, R.J. Garlic-Induced Systemic Contact Dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 1994, 30, 299–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, T.K.; Zug, K.A. Systemic Contact Dermatitis to Raw Cashew Nuts in a Pesto Sauce. Am J Contact Dermat 1998, 9, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kothari, R.; Kishore, K.; Sandhu, S.; Bhatnagar, A.; Pal, R.; Chand, S. Systemic Contact Dermatitis to Spices: Report of a Rare Case. Contact Dermatitis 2022, 86, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulsen, E. Systemic Allergic Dermatitis Caused by Sesquiterpene Lactones. Contact Dermatitis 2017, 76, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Groot, A.C. Myroxylon Pereirae Resin (Balsam of Peru) - A Critical Review of the Literature and Assessment of the Significance of Positive Patch Test Reactions and the Usefulness of Restrictive Diets. Contact Dermatitis 2019, 80, 335–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooms-Goossens, A.; Dubelloy, R.; Degreef, H. Contact and Systemic Contact-Type Dermatitis to Spices. Dermatol Clin 1990, 8, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheman, A.; Rakowski, E.M.; Chou, V.; Chhatriwala, A.; Ross, J.; Jacob, S.E. Balsam of Peru: Past and Future. Dermatitis 2013, 24, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, K.; Issa, C.J.; Nedorost, S.T.; Lio, P.A. Is Food-Triggered Atopic Dermatitis a Form of Systemic Contact Dermatitis? Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2024, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, J.; Sarin, A.; Wollina, U.; Lotti, T.; Navarini, A.A.; Mueller, S.M.; Grabbe, S.; Saloga, J.; Rokni, G.R.; Goldust, M. Review of Biologics in Allergic Contact Dermatitis. Contact Dermatitis 2020, 83, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez-Rivera, V.A.; Patel, H.; Dupuy, F.P.; Allakhverdi, Z.; Bouchard, C.; Madrenas, J.; Bissonnette, R.; Piccirillo, C.A.; Jack, C. NOD2 Agonism Counter-Regulates Human Type 2 T Cell Functions in Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell Cultures: Implications for Atopic Dermatitis. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikajiri, R.; Fukunaga, A.; Miyoshi, M.; Maeshige, N.; Washio, K.; Masaki, T.; Nishigori, C.; Yamamoto, I.; Toda, A.; Takahashi, M.; Asahara, S.I.; Kido, Y.; Usami, M. Dietary Intervention for Control of Clinical Symptom in Patients with Systemic Metal Allergy: A Single Center Randomized Controlled Clinical Study. Kobe J Med Sci 2024, 69, E129–E143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricciardi, L.; Arena, A.; Arena, E.; Zambito, M.; Ingrassia, A.; Valenti, G.; Loschiavo, G.; D'Angelo, A.; Saitta, S. Systemic Nickel Allergy Syndrome: Epidemiological Data from Four Italian Allergy Units. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2014, 27, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veien, N.K. Systemic Contact Dermatitis. Int J Dermatol 2011, 50, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Contaminants in the Food Chain (CONTAM); Schrenk, D. ; Bignami, M.; Bodin, L.; Chipman, J.K.; Del Mazo, J.; Grasl-Kraupp, B.; Hogstrand, C.; Hoogenboom, L.R.; Leblanc, J.C.; Nebbia, C.S.; et al. Update of the Risk Assessment of Nickel in Food and Drinking Water. EFSA J 2020, 18, e06268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roach, K.; Roberts, J. A Comprehensive Summary of Disease Variants Implicated in Metal Allergy. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 2022, 25, 279–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.D. Low Chromate Diet in Dermatology. Indian J Dermatol 2009, 54, 293–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontana, M.; Bianchi, L.; Hansel, K.; Agostinelli, D.; Stingeni, L. Nickel Allergy: Epidemiology, Pathomechanism, Clinical Patterns, Treatment and Prevention Programs. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2020, 20, 992–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnoli, R.; Lougaris, V.; Giardino, G.; Volpi, S.; Leonardi, L.; La Torre, F.; Federici, S.; Corrente, S.; Cinicola, B.L.; Soresina, A.; et al. Immunology Task Force of the Italian Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology (SIAIP). Inborn Errors of Immunity with Atopic Phenotypes: A Practical Guide for Allergists. World Allergy Organ J 2021, 14, 100513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Cabrera, N.M.; Bauman, B.M.; Iro, M.A.; Dabbah-Krancher, G.; Molho-Pessach, V.; Zlotogorski, A.; Shamriz, O.; Dinur-Schejter, Y.; Sharon, T.D.; Stepensky, P.; et al. Management of Atopy with Dupilumab and Omalizumab in CADINS Disease. J Clin Immunol 2024, 44, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaseghi-Shanjani, M.; Smith, K.L.; Sara, R.J.; Modi, B.P.; Branch, A.; Sharma, M.; Lu, H.Y.; James, E.L.; Hildebrand, K.J.; Biggs, C.M.; Turvey, S.E. Inborn Errors of Immunity Manifesting as Atopic Disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021, 148, 1130–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, H.C. Insights into the Pathogenesis of Allergic Disease from Dedicator of Cytokinesis 8 Deficiency. Curr Opin Immunol 2023, 80, 102277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbieux, C.; Bonnet des Claustres, M.; de la Brassinne, M.; Bricteux, G.; Bagot, M.; Bourrat, E.; Hovnanian, A. Duality of Netherton Syndrome Manifestations and Response to Ixekizumab. J Am Acad Dermatol 2021, 84, 1476–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hannula-Jouppi, K.; Laasanen, S.L.; Heikkilä, H.; Tuomiranta, M.; Tuomi, M.L.; Hilvo, S.; Kluger, N.; Kivirikko, S.; Hovnanian, A.; Mäkinen-Kiljunen, S.; et al. IgE Allergen Component-Based Profiling and Atopic Manifestations in Patients with Netherton Syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2014, 134, 985–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluel-Marmont, C.; Bellon, N.; Barbet, P.; Leclerc-Mercier, S.; Hadj-Rabia, S.; Dupont, C.; Bodemer, C. Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Colonic Mucosal Eosinophilia in Netherton Syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017, 139, 2003–2005.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prodinger, C.; Yerlett, N.; MacDonald, C.; Chottianchaiwat, S.; Goh, L.; Du Toit, G.; Mellerio, J.E.; Petrof, G.; Martinez, A.E. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Nutritional Deficiency and Food Allergy in a Cohort of 21 Patients with Netherton Syndrome. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2023, 34, e13914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuvel, K.; Heeringa, J.J.; Dalm, V.A.S.H.; Meijers, R.W.J.; van Hoffen, E.; Gerritsen, S.A.M.; van Zelm, M.C.; Pasmans, S.G.M.A. Comel-Netherton Syndrome: A Local Skin Barrier Defect in the Absence of an Underlying Systemic Immunodeficiency. Allergy 2020, 75, 1710–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abonia, J.P.; Wen, T.; Stucke, E.M.; Grotjan, T.; Griffith, M.S.; Kemme, K.A.; Collins, M.H.; Putnam, P.E.; Franciosi, J.P.; von Tiehl, K.F.; Tinkle, B.T.; Marsolo, K.A.; Martin, L.J.; Ware, S.M.; Rothenberg, M.E. High Prevalence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Patients with Inherited Connective Tissue Disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013, 132, 378–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Shea, K.M.; Aceves, S.S.; Dellon, E.S.; Gupta, S.K.; Spergel, J.M.; Furuta, G.T.; Rothenberg, M.E. Pathophysiology of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 333–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, C.A.; Yu, X.; O'Connell, M.P.; Lawrence, M.G.; Zhang, Y.; Karpe, K.; Zhao, M.; Siegel, A.M.; et al. ERBIN Deficiency Links STAT3 and TGF-β Pathway Defects with Atopy in Humans. J Exp Med 2017, 214, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, F.; Agrawal, D.K. Ethnic and Racial Disparities in Clinical Manifestations of Atopic Dermatitis. Arch Intern Med Res 2024, 7, 114–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savva, M.; Papadopoulos, N.G.; Gregoriou, S.; Katsarou, S.; Papapostolou, N.; Makris, M.; Xepapadaki, P. Recent Advancements in the Atopic Dermatitis Mechanism. Front Biosci 2024, 29, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simpson, E.L.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Pawlikowski, J.; Ghorayeb, E.G.; Ota, T.; Lebwohl, M.G. Interleukin-1α Inhibitor Bermekimab in Patients with Atopic Dermatitis: Randomized and Nonrandomized Studies. Arch Dermatol Res 2024, 316, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brough, H.A.; Nadeau, K.C.; Sindher, S.B.; Alkotob, S.S.; Chan, S.; Bahnson, H.T.; Leung, D.Y.M.; Lack, G. Epicutaneous Sensitization in the Development of Food Allergy: What is the Evidence and How Can This Be Prevented? Allergy 2020, 75, 2185–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, F. , Eigenmann PA. Atopic dermatitis and its relation to food allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020, 20, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hervé, P.L.; Dioszeghy, V.; Matthews, K.; Bee, K.J.; Campbell, D.E.; Sampson, H.A. Recent Advances in Epicutaneous Immunotherapy and Potential Applications in Food Allergy. Front Allergy 2023, 4, 1290003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.M.; Anvari, S.; Hauk, P.; Lio, P.; Nanda, A.; Sidbury, R.; Schneider, L. Atopic Dermatitis and Food Allergy: Best Practices and Knowledge Gaps—A Work Group Report from the AAAAI Allergic Skin Diseases Committee and Leadership Institute Project. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2022, 10, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubin, C.; Del Duca, E.; Guttman-Yassky, E. The IL-4, IL-13 and IL-31 Pathways in Atopic Dermatitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2021, 17, 835–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang IH, Chung WH, Wu PC, Chen CB. JAK-STAT signaling pathway in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis: An updated review. Front Immunol. 2022, 13, 1068260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Agache, I.; Song, Y.; Posso, M.; Alonso-Coello, P.; Rocha, C.; Solà, I.; Beltran, J.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M.; Brockow, K.; et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab for moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: A systematic review for the EAACI biologicals guidelines. Allergy 2021, 76, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agache, I.; Akdis, C.A.; Akdis, M.; Brockow, K.; Chivato, T.; Del Giacco, S.; Eiwegger, T.; Eyerich, K.; Giménez-Arnau, A.; Gutermuth, J.; et al. EAACI Biologicals Guidelines—dupilumab for children and adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2021, 76, 988–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czarnowicki, T.; He, H.; Krueger, J.G.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Atopic dermatitis endotypes and implications for targeted therapeutics. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019, 143, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maintz, L.; Welchowski, T.; Herrmann, N.; Brauer, J.; Traidl-Hoffmann, C.; Havenith, R.; Müller, S.; Rhyner, C.; Dreher, A.; Schmid, M.; Bieber, T. ; CK-CARE study group. IL-13, periostin and dipeptidyl-peptidase-4 reveal endotype-phenotype associations in atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2023, 17 January. [CrossRef]

- Song, A.; Lee, S.E.; Kim, J.H. Immunopathology and immunotherapy of inflammatory skin diseases. Immune Netw 2022, 22, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Wijs, L.E.M.; Nguyen, N.T.; Kunkeler, A.C.M.; Nijsten, T.; Damman, J.; Hijnen, D.J. Clinical and histopathological characterization of paradoxical head and neck erythema in patients with atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab: A case series. Br J Dermatol 2020, 183, 745–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glatz, M.; Bossard, P.P.; Hoetzenecker, W.; Schmid-Grendelmeier, P. The role of Malassezia spp. in atopic dermatitis. J Clin Med 2015, 4, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokura, Y.; Hayano, S. Subtypes of atopic dermatitis: From phenotype to endotype. Allergol Int 2022, 71, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuberbier, T.; Abdul Latiff, A.; Aggelidis, X.; Augustin, M.; Balan, R.G.; Bangert, C.; Beck, L.; Bieber, T.; Bernstein, J.A.; Bertolin Colilla, M.; et al. A concept for integrated care pathways for atopic dermatitis—A GA2LEN ADCARE initiative. Clin Transl Allergy 2023, 13, e12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, D.Y.M.; Calatroni, A.; Zaramela, L.S.; LeBeau, P.K.; Dyjack, N.; Brar, K.; David, G.; Johnson, K.; Leung, S.; Ramirez-Gama, M.; et al. The nonlesional skin surface distinguishes atopic dermatitis with food allergy as a unique endotype. Sci Transl Med 2019, 11, eaav2685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, J.; Melén, E.; Haahtela, T.; Koppelman, G.H.; Togias, A.; Valenta, R.; Akdis, C.A.; Czarlewski, W.; Rothenberg, M.; Valiulis, A.; et al. Rhinitis associated with asthma is distinct from rhinitis alone: The ARIA-MeDALL hypothesis. Allergy 2023, 78, 1169–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K.L.; Claudio-Etienne, E.; Frischmeyer-Guerrerio, P.A. Atopic dermatitis and food allergy: More than sensitization. Mucosal Immunol, 2024; S1933-021900059-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sernicola, A.; Amore, E.; Rizzuto, G.; Rallo, A.; Greco, M.E.; Battilotti, C.; Svara, F.; Azzella, G.; Nisticò, S.P.; Dattola, A.; Chello, C.; Pellacani, G.; Grieco, T. Dupilumab as Therapeutic Option in Polysensitized Atopic Dermatitis Patients Suffering from Food Allergy. Nutrients 2024, 16, 2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmann, M.M.; Caubet, J.C.; Boguniewicz, M.; Eigenmann, P.A. Evaluation of food allergy in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2013, 1, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breuer, K.; Heratizadeh, A.; Wulf, A.; Baumann, U.; Constien, A.; Tetau, D.; Kapp, A.; Werfel, T. Late eczematous reactions to food in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy 2004, 34, 817–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manam, S.; Tsakok, T.; Till, S.; Flohr, C. The association between atopic dermatitis and food allergy in adults. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2014, 14, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papapostolou, N.; Xepapadaki, P.; Gregoriou, S.; Makris, M. Atopic Dermatitis and Food Allergy: A Complex Interplay What We Know and What We Would Like to Learn. J Clin Med 2022, 11, 4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werfel, T.; Breuer, K. Role of food allergy in atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2004, 4, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dębińska, A.; Sozańska, B. Epicutaneous sensitization and food allergy: preventive strategies targeting skin barrier repair—facts and challenges. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werfel, T.; Ballmer-Weber, B.; Eigenmann, P.A.; Niggemann, B.; Rancé, F.; Turjanmaa, K.; Worm, M. Eczematous reactions to food in atopic eczema: position paper of the EAACI and GA2LEN. Allergy 2007, 62, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, H.; Hirasawa, N.; Asakawa, S.; Okita, K.; Tokura, Y. Intrinsic atopic dermatitis shows high serum nickel concentration. Allergol Int 2015, 64, 282–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glocova, I.; Brück, J.; Geisel, J.; Müller-Hermelink, E.; Widmaier, K.; Yazdi, A.S.; Röcken, M.; Ghoreschi, K. Induction of skin-pathogenic Th22 cells by epicutaneous allergen exposure. J Dermatol Sci 2017, 87, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuge, I.; Kondo, Y.; Tokuda, R.; Kakami, M.; Kawamura, M.; Nakajima, Y.; Komatsubara, R.; Yamada, K.; Urisu, A. Allergen-specific helper T cell response in patients with cow's milk allergy: Simultaneous analysis of proliferation and cytokine production by carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester dilution assay. Clin Exp Allergy 2006, 36, 1538–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, J.; Noh, G. Allergen-specific responses of CD19(high) and CD19(low) B Cells in Non-IgE-mediated food allergy of late eczematous reactions in atopic dermatitis: presence of IL-17- and IL-32-producing regulatory B cells (Br17 & Br32). Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 2012, 11, 320–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, J.; Noh, G.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, A.R.; Choi, W.S. Allergen-specific responses of CD19(+)CD5(+)Foxp3(+) regulatory B cells (Bregs) and CD4(+)Foxp3(+) regulatory T cell (Tregs) in immune tolerance of cow milk allergy of late eczematous reactions. Cell Immunol 2012, 274, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sütas, Y.; Kekki, O.M.; Isolauri, E. Late onset reactions to oral food challenge are linked to low serum interleukin-10 concentrations in patients with atopic dermatitis and food allergy. Clin Exp Allergy 2000, 30, 1121–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abernathy-Carver, K.J.; Sampson, H.A.; Picker, L.J.; Leung, D.Y. Milk-induced eczema is associated with the expansion of T cells expressing cutaneous lymphocyte antigen. J Clin Invest 1995, 95, 913–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolàs, L.S.S.; Czarnowicki, T.; Akdis, M.; Pujol, R.M.; Lozano-Ojalvo, D.; Leung, D.Y.M.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Santamaria-Babí, L.F. CLA+ memory T cells in atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2024, 79, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glickman, J.W.; Han, J.; Garcet, S.; Krueger, J.G.; Pavel, A.B.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Improving evaluation of drugs in atopic dermatitis by combining clinical and molecular measures. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020, 8, 3622–3625.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homey, B.; Alenius, H.; Müller, A.; Soto, H.; Bowman, E.P.; Yuan, W.; McEvoy, L.; Lauerma, A.I.; Assmann, T.; Bünemann, E.; et al. CCL27-CCR10 interactions regulate T cell-mediated skin inflammation. Nat Med 2002, 8, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, A.; Wang, J.; Yu, L.; Liu, H.; Estrada, Y.; Greenlees, L.; McPhee, R.; Ruzin, A.; Guttman-Yassky, E.; Howell, M.D. Atopic Dermatitis Endotypes Based on Allergen Sensitization, Reactivity to Staphylococcus aureus Antigens, and Underlying Systemic Inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020, 8, 236–247.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, N.; Benfeitas, R.; Katayama, S.; Bruhn, S.; Andersson, A.; Wikberg, G.; Lundeberg, L.; Lindvall, J.M.; Greco, D.; Kere, J.; et al. Epigenetic alterations in skin homing CD4+CLA+ T cells of atopic dermatitis patients. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 18020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnowicki, T.; Malajian, D.; Shemer, A.; Fuentes-Duculan, J.; Gonzalez, J.; Suárez-Fariñas, M.; Krueger, J.G.; Guttman-Yassky, E. Skin-homing and systemic T-cell subsets show higher activation in atopic dermatitis versus psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015, 136, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, S.M.; Irvine, A.D.; Weidinger, S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2020, 396, 345–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sans-De San Nicolàs, L.; Figueras-Nart, I.; Bonfill-Ortí, M.; De Jesús-Gil, C.; García-Jiménez, I.; Guilabert, A.; Curto-Barredo, L.; Bertolín-Colilla, M.; Ferran, M.; Serra-Baldrich, E.; et al. SEB-induced IL-13 production in CLA+ memory T cells defines Th2 high and Th2 low responders in atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2022, 77, 3448–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soul, J.; Carlsson, E.; Hofmann, S.R.; Russ, S.; Hawkes, J.; Schulze, F.; Sergon, M.; Pablik, J.; Abraham, S.; Hedrich, C.M. Tissue gene expression profiles and communication networks inform candidate blood biomarker identification in psoriasis and atopic dermatitis. Clin Immunol 2024, 265, 110283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.H.; Dong, C. Signaling of interleukin-17 family cytokines in immunity and inflammation. Cell Signal 2011, 23, 1069–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberth, G.; Daegelmann, C.; Röder, S.; Behrendt, H.; Krämer, U.; Borte, M.; Heinrich, J.; Herbarth, O.; Lehmann, I.; LISAplus study group. IL-17E but not IL-17A is associated with allergic sensitization: results from the LISA study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2010, 21, 1086–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, M.A.; Fluhr, J.W.; Ruwwe-Glösenkamp, C.; Stevanovic, K.; Bergmann, K.C.; Zuberbier, T. Role of IL-17 in atopy—A systematic review. Clin Transl Allergy 2021, 11, e12047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żbikowska-Gotz, M.; Pałgan, K.; Gawrońska-Ukleja, E.; Kuźmiński, A.; Przybyszewski, M.; Socha, E.; Bartuzi, Z. Expression of IL-17A concentration and effector functions of peripheral blood neutrophils in food allergy hypersensitivity patients. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2016, 29, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berin, M.C.; Lozano-Ojalvo, D.; Agashe, C.; Baker, M.G.; Bird, J.A.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A. Acute FPIES reactions are associated with an IL-17 inflammatory signature. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021, 148, 895–901.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Ojalvo, D.; Chen, X.; Dunkin, D.; Agashe, C.; Baker, M.G.; Bird, J.A.; Molina, E.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Berin, M.C. Untargeted serum metabolomic analysis reveals a role for purinergic signaling in FPIES. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023, 151, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Delgado, P.; Anvari, S.; Barrachina, J.; Portillo, A.L.J.; Jimenez, T.; Marco de la Calle, F.M.; Fernandez, J. Egg-induced adult food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome: Clinical phenotypes, natural history and immunological characteristics. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024, 12, 1657–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fina, D.; Sarra, M.; Caruso, R.; Del Vecchio Blanco, G.; Pallone, F.; MacDonald, T.T.; Monteleone, G. Interleukin 21 contributes to the mucosal T helper cell type 1 response in coeliac disease. Gut 2008, 57, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omidian, Z.; Ahmed, R.; Giwa, A.; Donner, T.; Hamad, A.R.A. IL-17 and limits of success. Cell Immunol 2019, 339, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, C.; Fernández, S.; Estévez, O.A.; Aguado, R.; Molina, I.J.; Santamaría, M. IL-17 producing T cells in celiac disease: angels or devils? Int Rev Immunol 2013, 32, 534–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjöberg, V.; Sandström, O.; Hedberg, M.; Hammarström, S.; Hernell, O.; Hammarström, M.L. Intestinal T-cell responses in celiac disease - impact of celiac disease associated bacteria. PLoS One 2013, 8, e53414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicerone, C.; Nenna, R.; Pontone, S. Th17, intestinal microbiota and the abnormal immune response in the pathogenesis of celiac disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2015, 8, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lahdenperä, A.I.; Fälth-Magnusson, K.; Högberg, L.; Ludvigsson, J.; Vaarala, O. Expression pattern of T-helper 17 cell signaling pathway and mucosal inflammation in celiac disease. Scand J Gastroenterol 2014, 49, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madi, M.; Abdelsalam, M.; Elakel, A.; Zakaria, O.; AlGhamdi, M.; Alqahtani, M.; AlMuhaish, L.; Farooqi, F.; Alamri, T.A.; Alhafid, I.A.; Alzahrani, I.M.; Alam, A.H.; Alhashmi, M.T.; Alasseri, I.A.; AlQuorain, A.A. Salivary interleukin-17A and interleukin-18 levels in patients with celiac disease and periodontitis. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caproni, M.; Capone, M.; Rossi, M.C.; Santarlasci, V.; Maggi, L.; Mazzoni, A.; Rossettini, B.; Renzi, D.; Quintarelli, L.; Bianchi, B.; et al. T Cell Response Toward Tissue-and Epidermal-Transglutaminases in Coeliac Disease Patients Developing Dermatitis Herpetiformis. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 645143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, P.; Salmi, T.T.; Hervonen, K.; Kaukinen, K.; Reunala, T. Dermatitis herpetiformis: a cutaneous manifestation of coeliac disease. Ann Med 2017, 49, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bañares, F.; Crespo, L.; Planella, M.; Farrais, S.; Izquierdo, S.; López-Palacios, N.; Roy, G.; Vidal, J.; Núñez, C. Improving the Diagnosis of Dermatitis Herpetiformis Using the Intraepithelial Lymphogram. Nutrients 2024, 16, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, C.N.; Kim, S.J. Dermatitis Herpetiformis: An Update on Diagnosis, Disease Monitoring, and Management. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021, 57, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velikova, T.; Shahid, M.; Ivanova-Todorova, E.; Drenovska, K.; Tumangelova-Yuzeir, K.; Altankova, I.; Vassileva, S. Celiac-Related Autoantibodies and IL-17A in Bulgarian Patients with Dermatitis Herpetiformis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina 2019, 55, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, D.S.; Nierkens, S.; Knol, E.F.; Giovannone, B.; Delemarre, E.M.; van der Schaft, J.; van Wijk, F.; de Bruin-Weller, M.S.; Drylewicz, J.; Thijs, J.L. Confirmation of multiple endotypes in atopic dermatitis based on serum biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021, 147, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peled, A.; Sarig, O.; Sun, G.; Samuelov, L.; Ma, C.A.; Zhang, Y.; Dimaggio, T.; Nelson, C.G.; Stone, K.D.; Freeman, A.F.; et al. Loss-of-function mutations in caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 14 (CARD14) are associated with a severe variant of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2019, 143, 173–181.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y.C.; Tsai, T.F. Overlapping Features of Psoriasis and Atopic Dermatitis: From Genetics to Immunopathogenesis to Phenotypes. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, M.S.; Yun, J.S.; Su, J.C. Management of atopic dermatitis: a narrative review. Med J Aust 2022, 216, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laska, J.; Tota, M.; Łacwik, J.; Sędek, Ł.; Gomułka, K. IL-22 in Atopic Dermatitis. Cells 2024, 13, 1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugaya, M. The Role of Th17-Related Cytokines in Atopic Dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsoi, L.C.; Rodriguez, E.; Stölzl, D.; Wehkamp, U.; Sun, J.; Gerdes, S.; Sarkar, M.K.; Hübenthal, M.; Zeng, C.; Uppala, R.; et al. Progression of acute-to-chronic atopic dermatitis is associated with quantitative rather than qualitative changes in cytokine responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2020, 145, 1406–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidinger, S.; Novak, N. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet 2016, 387, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furue, M. Regulation of Filaggrin, Loricrin, and Involucrin by IL-4, IL-13, IL-17A, IL-22, AHR, and NRF2: Pathogenic Implications in Atopic Dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, T.; Honda, T.; Kabashima, K. Multipolarity of cytokine axes in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis in terms of age, race, species, disease stage and biomarkers. Int Immunol 2018, 30, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giancotta, C.; Colantoni, N.; Pacillo, L.; Santilli, V.; Amodio, D.; Manno, E.C.; Cotugno, N.; Rotulo, G.A.; Rivalta, B.; Finocchi, A.; Cancrini, C.; Diociaiuti, A.; El Hachem, M.; Zangari, P. Tailored treatments in inborn errors of immunity associated with atopy (IEIs-A) with skin involvement. Front Pediatr 2023, 11, 1129249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luchsinger, I.; Knöpfel, N.; Theiler, M.; Bonnet des Claustres, M.; Barbieux, C.; Schwieger-Briel, A.; Brunner, C.; Donghi, D.; Buettcher, M.; Meier-Schiesser, B.; Hovnanian, A.; Weibel, L. Secukinumab Therapy for Netherton Syndrome. JAMA Dermatol 2020, 156, 907–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontone, M.; Giovannini, M.; Filippeschi, C.; Oranges, T.; Pedaci, F.A.; Mori, F.; Barni, S.; Barbati, F.; Consonni, F.; Indolfi, G.; Lodi, L.; Azzari, C.; Ricci, S.; Hovnanian, A. Biological treatments for pediatric Netherton syndrome. Front Pediatr 2022, 10, 1074243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.J.; Eller, E.; Kjaer, H.F.; Broesby-Olsen, S.; Mortz, C.G.; Bindslev-Jensen, C. Exercise-induced anaphylaxis: causes, consequences, and management recommendations. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2019, 15, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, E.; Chinuki, Y.; Kohno, K.; Matsuo, H. Cofactors of wheat-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis increase gastrointestinal gliadin absorption by an inhibition of prostaglandin production. Clin Exp Allergy 2023, 53, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M. Food allergies and food-induced anaphylaxis: role of cofactors. Clin Exp Pediatr 2021, 64, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, L.; Bérard, F.; Debrauwer, L.; Chabo, C.; Langella, P.; Buéno, L.; Fioramonti, J. Impairment of the intestinal barrier by ethanol involves enteric microflora and mast cell activation in rodents. Am J Pathol 2006, 168, 1148–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feuille, E.; Nowak-Węgrzyn, A. Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome, Allergic Proctocolitis, and Enteropathy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2015, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A.; Nobleza, K.; Haddad, C.; Eubanks, J.; Rana, R.; Rider, N.L.; Pompeii, L.; Nguyen, D.; Anvari, S. Applying Market Basket Analysis to Determine Complex Coassociations Among Food Allergens in Children With Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome (FPIES). Health Serv Res Manag Epidemiol 2024, 11, 23333928241264020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labrosse, R.; Graham, F.; Caubet, J.C. Non-IgE-Mediated Gastrointestinal Food Allergies in Children: An Update. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berin, M.C.; Lozano-Ojalvo, D.; Agashe, C.; Baker, M.G.; Bird, J.A.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A. Acute FPIES reactions are associated with an IL-17 inflammatory signature. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2021, 148, 895–901.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lozano-Ojalvo, D.; Chen, X.; Dunkin, D.; Agashe, C.; Baker, M.G.; Bird, J.A.; Molina, E.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Berin, M.C. Untargeted serum metabolomic analysis reveals a role for purinergic signaling in FPIES. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2023, 151, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzi, A.; Lo Presti, E.; Chini, R.; Gammeri, L.; Inchingolo, R.; Lohmeyer, F.M.; Nucera, E.; Gangemi, S. Emerging Role of Alarmins in Food Allergy: An Update on Pathophysiological Insights, Potential Use as Disease Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Implications. J Clin Med 2023, 12, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wada, T.; Matsuda, Y.; Toma, T.; Koizumi, E.; Okamoto, H.; Yachie, A. Increased CD69 Expression on Peripheral Eosinophils from Patients with Food Protein-Induced Enterocolitis Syndrome. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2016, 170, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubeldia-Varela, E.; Barker-Tejeda, T.C.; Blanco-Pérez, F.; Infante, S.; Zubeldia, J.M.; Pérez-Gordo, M. Non-IgE-Mediated Gastrointestinal Food Protein-Induced Allergic Disorders: Clinical Perspectives and Analytical Approaches. Foods 2021, 10, 2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koksal, B.T.; Barıs, Z.; Sencelikel, T.; Ozcay, F.; Ozbek, O.Y. Food Protein-Induced Allergic Proctocolitis in Infants Is Associated with Low Serum Levels of Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-3a. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2024, 78, 211–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsabouri, S.; Nicolaou, N.; Douros, K.; Papadopoulou, A.; Priftis, K.N. Food Protein Induced Proctocolitis: A Benign Condition with an Obscure Immunologic Mechanism. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets 2017, 17, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, J.; Deb, C.; Bornstein, J.; Horvath, K.; Mehta, D.; Smadi, Y. Using Eosinophil Biomarkers from Rectal Epithelial Samples to Diagnose Food Protein-Induced Proctocolitis: A Pilot Study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2020, 71, e109–e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rycyk, A.; Cudowska, B.; Lebensztejn, D.M. Eosinophil-Derived Neurotoxin, Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha, and Calprotectin as Non-Invasive Biomarkers of Food Protein-Induced Allergic Proctocolitis in Infants. J Clin Med 2020, 9, 3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jauregi-Miguel, A. The Tight Junction and the Epithelial Barrier in Coeliac Disease. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 2021, 358, 105–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowińska, A.; Morsy, Y.; Czarnowska, E.; Oralewska, B.; Konopka, E.; Woynarowski, M.; Szymańska, S.; Ejmont, M.; Scharl, M.; Bierła, J.B.; Wawrzyniak, M.; Cukrowska, B. Transcriptional and Ultrastructural Analyses Suggest Novel Insights into Epithelial Barrier Impairment in Celiac Disease. Cells 2020, 9, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taraz, T.; Mahmoudi-Ghehsareh, M.; Asri, N.; Nazemalhosseini-Mojarad, E.; Rezaei-Tavirani, M.; Jahani-Sherafat, S.; Naseh, A.; Rostami-Nejad, M. Overview of the Compromised Mucosal Integrity in Celiac Disease. J Mol Histol 2024, 55, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak-Budnik, T.; Moura, I.C.; Arcos-Fajardo, M.; Lebreton, C.; Ménard, S.; Candalh, C.; Ben-Khalifa, K.; Dugave, C.; Tamouza, H.; van Niel, G.; et al. Secretory IgA Mediates Retrotranscytosis of Intact Gliadin Peptides via the Transferrin Receptor in Celiac Disease. J Exp Med 2008, 205, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbaro, M.R.; Cremon, C.; Morselli-Labate, A.M.; Di Sabatino, A.; Giuffrida, P.; Corazza, G.R.; Di Stefano, M.; Caio, G.; Latella, G.; Ciacci, C.; et al. Serum Zonulin and Its Diagnostic Performance in Non-Coeliac Gluten Sensitivity. Gut 2020, 69, 1966–1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotondi Aufiero, V.; Fasano, A.; Mazzarella, G. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: How Its Gut Immune Activation and Potential Dietary Management Differ from Celiac Disease. Mol Nutr Food Res 2018, 62, e1700854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapone, A.; Lammers, K.M.; Mazzarella, G.; Mikhailenko, I.; Cartenì, M.; Casolaro, V.; Fasano, A. Differential Mucosal IL-17 Expression in Two Gliadin-Induced Disorders: Gluten Sensitivity and the Autoimmune Enteropathy Celiac Disease. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2010, 152, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingone, F.; Bertin, L.; Maniero, D.; Palo, M.; Lorenzon, G.; Barberio, B.; Ciacci, C.; Savarino, E.V. Myths and Facts about Food Intolerance: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleuskens, M.T.A.; Bek, M.K.; Al Halabi, Y.; Blokhuis, B.R.J.; Diks, M.A.P.; Haasnoot, M.L.; Garssen, J.; Bredenoord, A.J.; van Esch, B.C.A.M.; Redegeld, F.A. Mast Cells Disrupt the Function of the Esophageal Epithelial Barrier. Mucosal Immunol 2023, 16, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyon, G.C.; Masuda, M.Y.; Putikova, A.; Luo, H.; Gibson, J.B.; Dao, A.D.; Ortiz, D.R.; Heiligenstein, P.L.; Bonellos, J.J.; LeSuer, W.E.; Pai, R.K.; Garg, S.; Rank, M.A.; Nakagawa, H.; Kita, H.; Wright, B.L.; Doyle, A.D. Tissue-Specific Inducible IL-33 Expression Elicits Features of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2024, S0091-6749, 00910–00912. [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.; Page, B.; Vogel, M.; Bussmann, C.; Blanchard, C.; Straumann, A.; Simon, H.U. Evidence of an Abnormal Epithelial Barrier in Active, Untreated and Corticosteroid-Treated Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Allergy 2018, 73, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolinska, S.; Antolín-Amérigo, D.; Popescu, F.D.; Jutel, M. Thymic Stromal Lymphopoietin (TSLP), Its Isoforms and the Interplay with the Epithelium in Allergy and Asthma. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 12725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, A.M.; Lenehan, P.J.; Vimalathas, P.; Miller, K.C.; Valencia-Yang, M.; Qiang, L.; Canha, L.A.; Ali, L.R.; Dougan, M.; Garber, J.J.; Dougan, S.K. Tissue Eosinophils Express the IL-33 Receptor ST2 and Type 2 Cytokines in Patients with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Allergy 2022, 77, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Litosh, V.A.; Rochman, M.; Rymer, J.K.; Porollo, A.; Kottyan, L.C.; Rothenberg, M.E. Calpain-14 and Its Association with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017, 139, 1762–1771.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAleer, M.A.; Pohler, E.; Smith, F.J.; Wilson, N.J.; Cole, C.; MacGowan, S.; Koetsier, J.L.; Godsel, L.M.; Harmon, R.M.; Gruber, R.; et al. Severe Dermatitis, Multiple Allergies, and Metabolic Wasting Syndrome Caused by a Novel Mutation in the N-terminal Plakin Domain of Desmoplakin. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015, 136, 1268–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, C.; Zhao, A.; Li, M. Atopic Dermatitis-like Genodermatosis: Disease Diagnosis and Management. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12, 2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrodowczyk, A.; Markiewicz, L.; Wróblewska, B. Mutations in the Filaggrin Gene and Food Allergy. Prz Gastroenterol 2014, 9, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, A.D.; McLean, W.H.; Leung, D.Y. Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic diseases. N Engl J Med 2011, 365, 1315–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, E.H.; Leung, D.Y. Mechanisms by Which Atopic Dermatitis Predisposes to Food Allergy and the Atopic March. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2019, 11, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, A.; Guttman-Yassky, E. The Unique Molecular Signatures of Contact Dermatitis and Implications for Treatment. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2019, 56, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sashikawa-Kimura, M.; Takada, M.; Hossain, M.R.; Tsuda, H.; Xie, X.; Komine, M.; Ohtsuki, M.; Imokawa, G. Overexpression of the β-Subunit of Acid Ceramidase in the Epidermis of Mice Provokes Atopic Dermatitis-like Skin Symptoms. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25, 8737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawai, T.; Autieri, M.V.; Scalia, R. Adipose Tissue Inflammation and Metabolic Dysfunction in Obesity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2021, 320, C375–C391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; Khanna, S.; Khanna, P.; Kahar, P.; Patel, B.M. Obesity: A Chronic Low-Grade Inflammation and Its Markers. Cureus 2022, 14, e22711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Ortega, O.; Moreno-Corona, N.C.; Cruz-Holguin, V.J.; Garcia-Gonzalez, L.D.; Helguera-Repetto, A.C.; Romero-Valdovinos, M.; Arevalo-Romero, H.; Cedillo-Barron, L.; León-Juárez, M. The Immune Response in Adipocytes and Their Susceptibility to Infection: A Possible Relationship with Infectobesity. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 6154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morąg, B.; Kozubek, P.; Gomułka, K. Obesity and Selected Allergic and Immunological Diseases—Etiopathogenesis, Course and Management. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P. The Role of Diet and Nutrition in Allergic Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gargano, D.; Appanna, R.; Santonicola, A.; De Bartolomeis, F.; Stellato, C.; Cianferoni, A.; Casolaro, V.; Iovino, P. Food Allergy and Intolerance: A Narrative Review on Nutritional Concerns. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poto, R.; Fusco, W.; Rinninella, E.; Cintoni, M.; Kaitsas, F.; Raoul, P.; Caruso, C.; Mele, M.C.; Varricchi, G.; Gasbarrini, A. The Role of Gut Microbiota and Leaky Gut in the Pathogenesis of Food Allergy. Nutrients 2023, 16, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangye, S.G.; Al-Herz, W.; Bousfiha, A.; Cunningham-Rundles, C.; Franco, J.L.; Holland, S.M.; Klein, C.; Morio, T.; Oksenhendler, E.; Picard, C.; Puel, A.; et al. Human Inborn Errors of Immunity: 2022 Update on the Classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee. J Clin Immunol 2022, 42, 1473–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]