1. Introduction

Mammary and sweat glands originate from the ectoderm during embryonic devel-opment [

1], which explains their similar structure and function [

2]. Consequently, distin-guishing between tumors arising from these glands can be challenging due to their mor-phological and clinical similarities [

2,

3]. While both mammary gland carcinoma (MGC) and sweat gland carcinoma (SGC) share overlapping histological and immunohisto-chemical features [

2,

4], their treatment and prognosis differ significantly. Thus, accurate differentiation is essential for proper clinical management.

The World Health Organization's (WHO) 4th edition of the Classification of Skin Tumors has emphasized the importance of immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis in iden-tifying adnexal tumors, such as sweat gland neoplasms [

5]. Various cytokeratin (CK) markers, including CK5 [

4], CK8 [

6], CK18 [

6], CK8/18 [

7], and CK19 [

6,

8], are routinely used to diagnose skin appendage tumors, particularly those of sweat gland origin. Addi-tionally, Sox9, a marker involved in the development of various tissues, including skin adnexa, is instrumental in distinguishing between sweat and mammary gland neo-plasms [

9,

10,

11].

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) is a low-grade ad-nexal tumor with neuroendocrine differentiation [

12,

13,

14]. This tumor, originally described in human cases, is rare, and information on animal cases is limited. EMPSGC shares histological characteristics with other neuroendocrine tumors, such as solid papillary carcinoma and ductal carcinoma in situ of the mammary gland [

13,

14]. Histologically, EMPSGC exhibits mucin accumulation, neuroendocrine features [

13], and poor nuclear differentiation.

This study reports the first canine case of EMPSGC, focusing on its diagnostic chal-lenges and the utility of immunohistochemical markers in distinguishing it from other adnexal tumors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Histopathology

Tissues were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and sectioned at 4-µm thickness for histopathological examination.

Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains. Immunohistochemistry was performed using antibodies for CK19, Sox9, CK5, AE1/AE3+CK8/18, p63, vimentin, E-cadherin, and synaptophysin (

Table 1). Antigen retrieval was achieved with a citrate buffer (pH 6.0), and sections were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. A biotinylated secondary antibody was applied, followed by the avidin-biotin complex (ABC) method with diaminobenzidine (DAB) as the chromogen.

2.2. Case presentation

2.2.1. Case 1

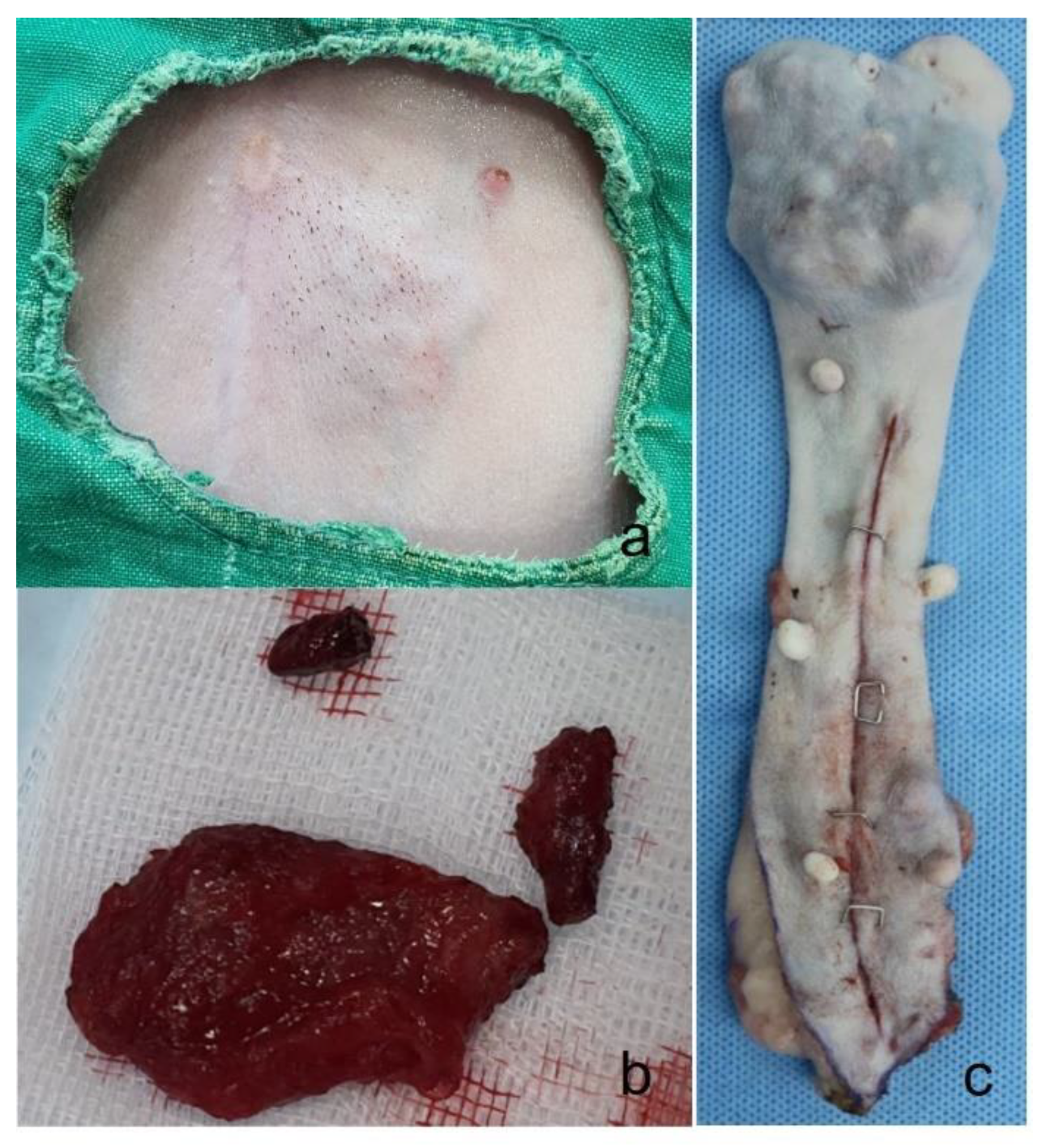

A seven-year-old spayed female poodle presented with several small, spindle-shaped nodules approximately the size of rice grains on the skin near the left second mammary gland (

Figure 1a). Despite the presence of these nodules, the dog’s appetite, water intake, urine output, and overall vitality remained within normal limits. During physical examination, a slight inspiratory bronchial sound was noted upon pulmonary auscultation, while both cardiac auscultation and heartworm testing were normal. A comprehensive diagnostic evaluation, including blood tests (complete blood count, serum chemistry panels, C-reactive protein, symmetrical dimethylarginine, thyroxine levels), and thoracic radiographs, revealed no significant abnormalities.

One month after the initial presentation, the skin overlying the abdominal masses became bluish in color, and the nodules coalesced into a larger, irregular mass. The mass was firm and caused visible protrusion of the skin. Surgical excision was performed at JUNG Animal Clinic, during which it was noted that the mass was firmly adherent to the underlying skin and sub-cutaneous connective tissue and exhibited moderate bleeding (

Figure 1b). The mass was successfully removed, and postoperative recovery was uneventful. The dog’s prognosis was favorable, with no signs of recurrence observed to date.

2.2.2. Case 2

A sixteen-year-old neutered female Maltese presented with a 7x6 cm mass on the right 2nd mammary gland, persisting for five years. The mass was excised (

Figure 1c) at Chungnam National University-Veterinary Medicine Teaching Hospital, and no metastatic lesions were detected.

3. Results

3.1. Case 1

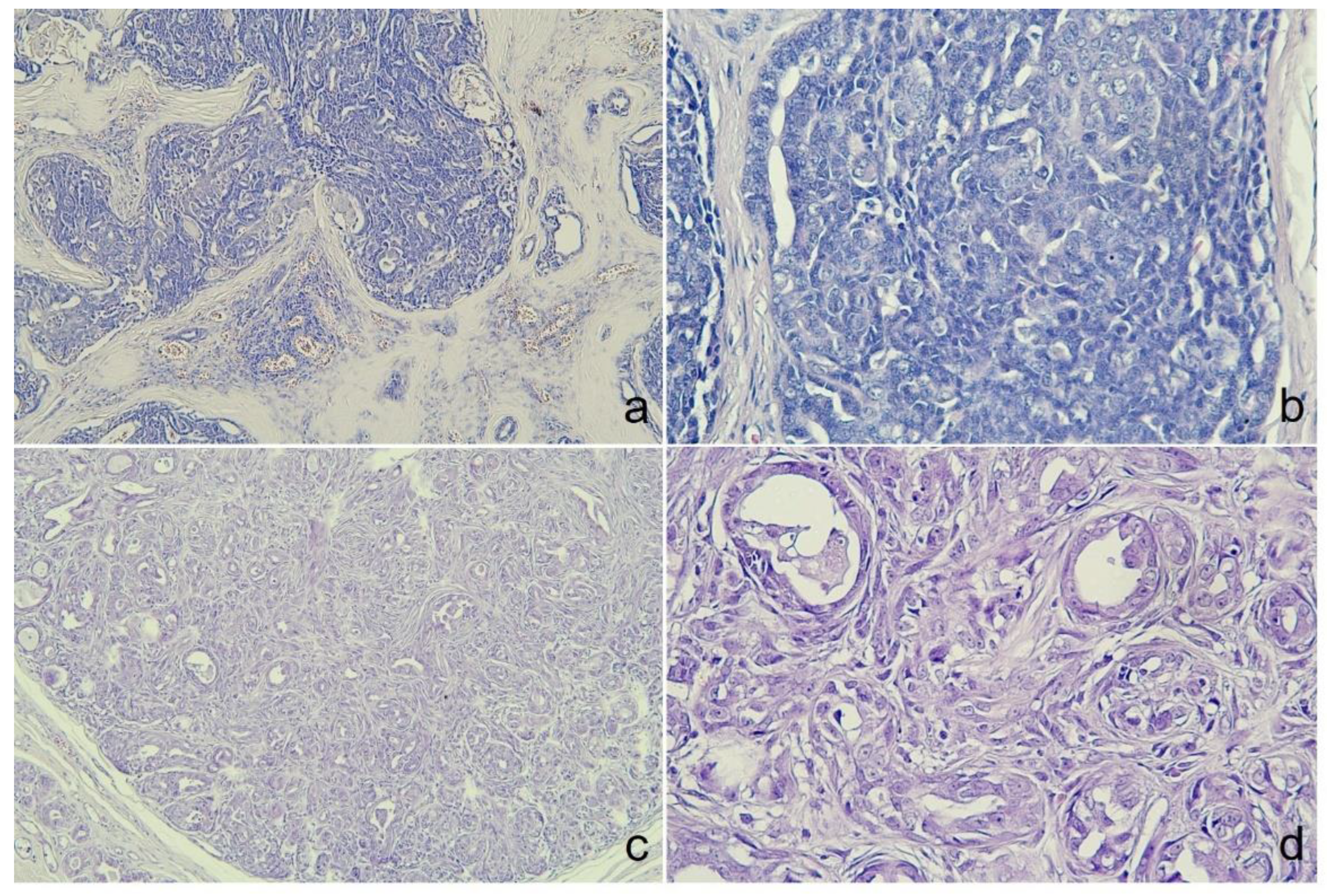

Microscopically, the tumor was organized into lobules divided by thick fibrous connective stroma. The tumor exhibited a heterogeneous architectural pattern, including solid nests, cribriform areas, and cystic formations filled with mucinous material (

Figure 2a). The round to oval neoplastic cells had eosinophilic cytoplasm with pleomorphic nuclei, and occasional mitotic figures were observed (

Figure 2b). Focal areas of mucin production and deposits were confirmed by PAS staining. There was no evidence of necrosis, although some inflammatory cells were identified in the interstitial areas. Immunohistochemical analysis (

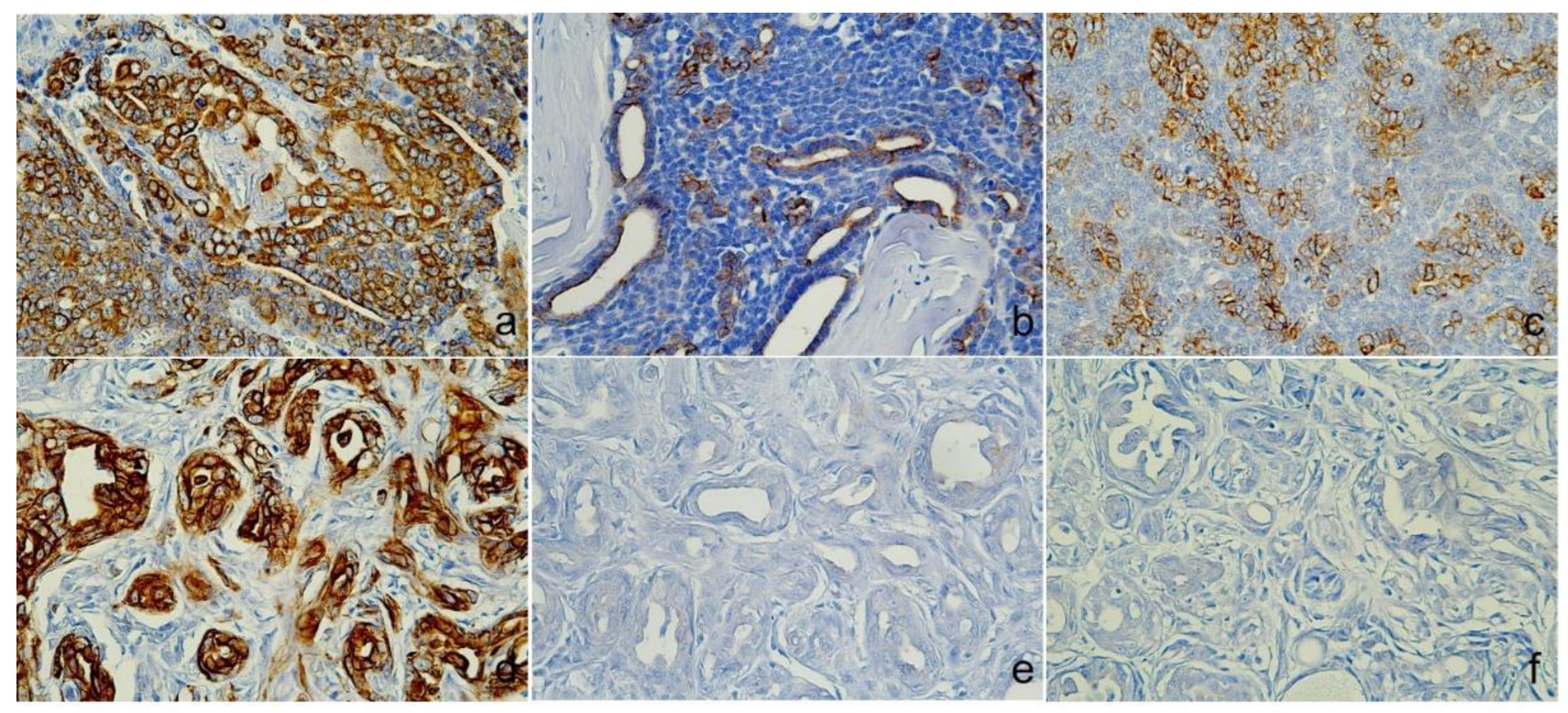

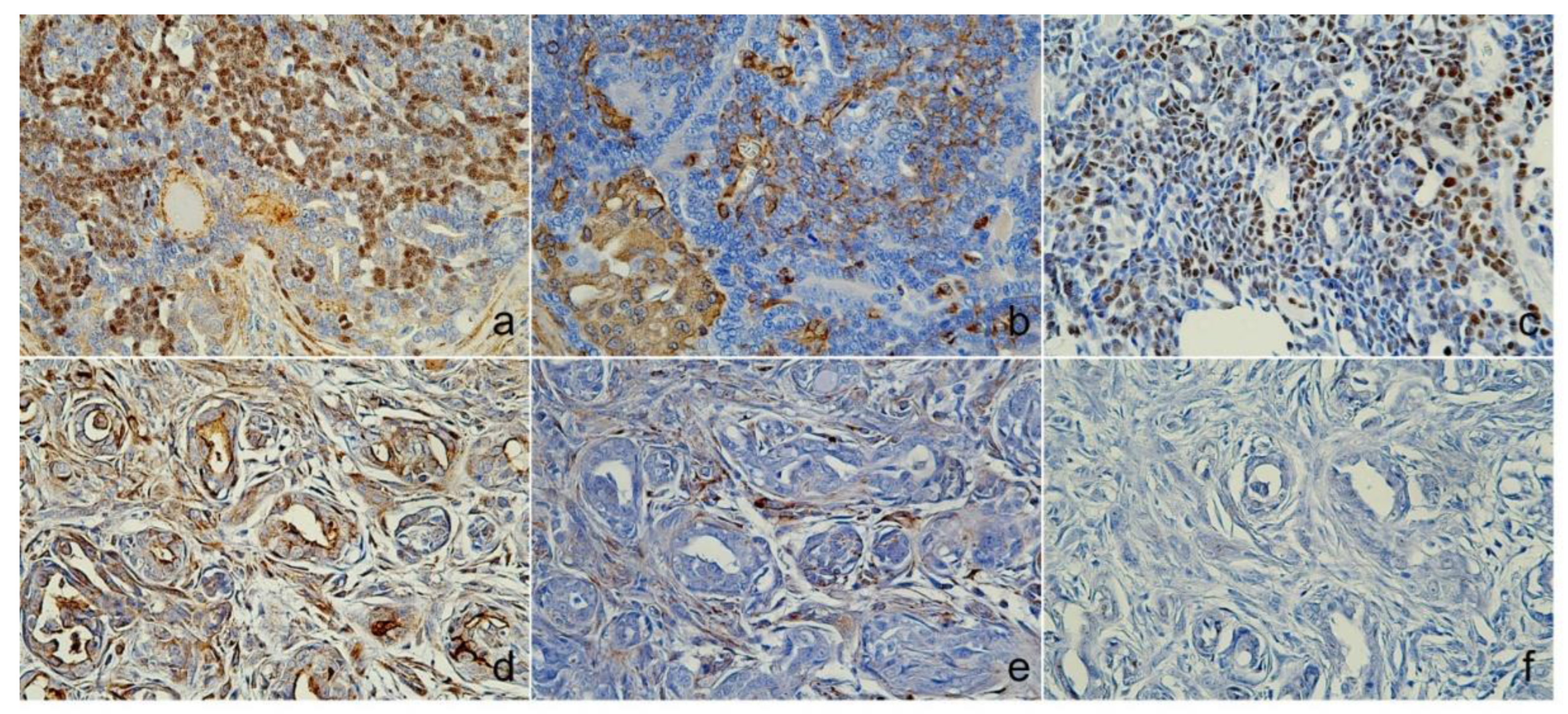

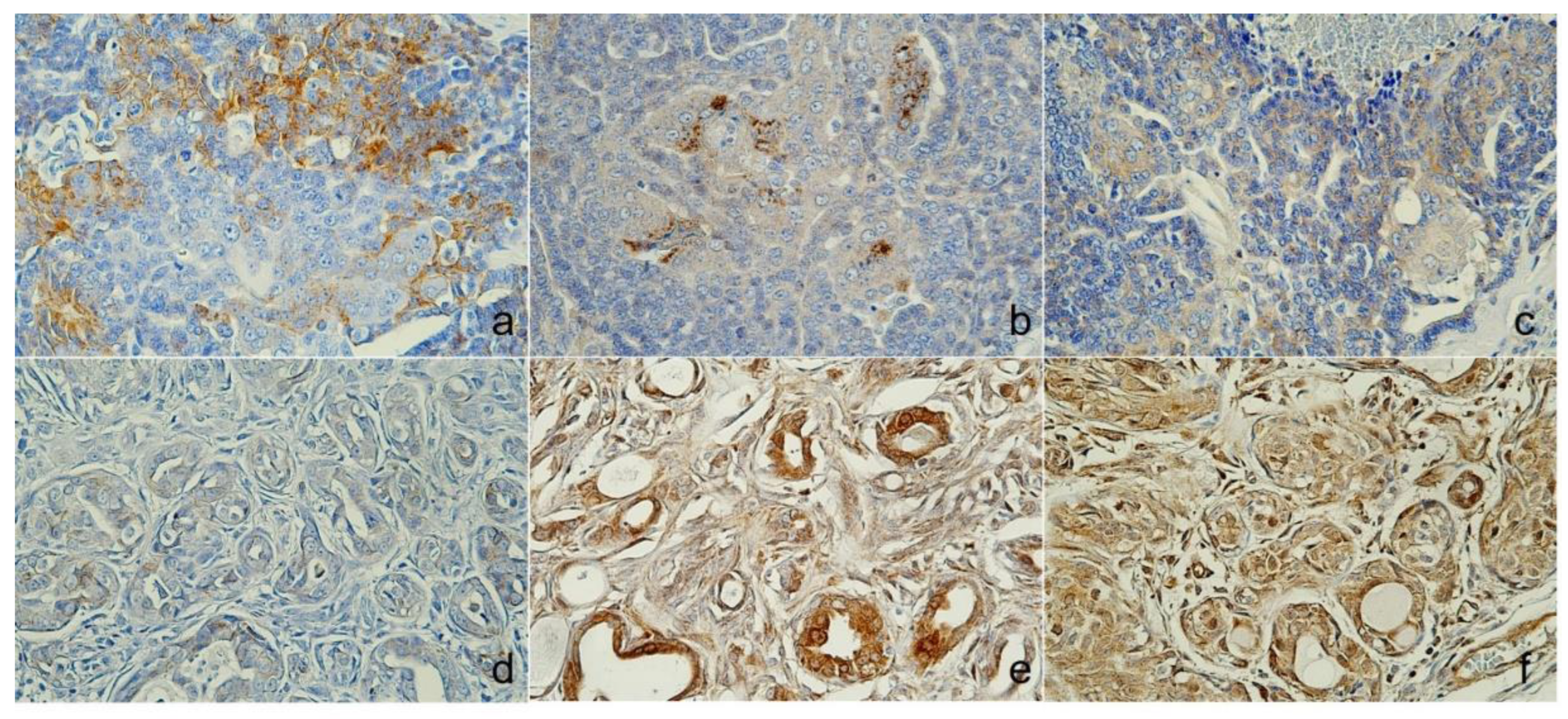

Table 2) showed positive staining for CK5, AE1/AE3+CK8/18, and CK19 (

Figure 3a–c), p63, vimentin, and Sox9 (

Figure 4a–c), E-cadherin, and synaptophysin, while estrogen receptor staining was negative (

Figure 5a–c). The presence of neuroendocrine differentiation, confirmed by positive synaptophysin staining, along with the overall histomophological features, led to the final diagnosis of EMPSGC.

3.2. Case 2

The tumor from the sixteen-year-old Maltese was histologically diagnosed as MGC. Microscopically, the tumor showed poorly defined margins (

Figure 2c) with 2 mitotic counts per 10 high-powered fields, and no lymphovascular invasion was observed (

Figure 2d). Immunohistochemistry revealed positive expressions of CK5 (

Figure 3d), p63, and vimentin in the myoepithelial cells (

Figure 4d and e), while markers such as AE1/AE3+CK8/18 (

Figure 3e), CK19 (

Figure 3f), Sox9 (

Figure 4f), and E-cadherin were negative (Figure d). Estrogen and synaptophysin immunoreactivities were positive (

Figure 5e and f), supporting the diagnosis of MGC.

4. Discussion

The diagnosis of EMPSGC presents a significant challenge in veterinary pathology due to its rarity and histological similarities to other adnexal tumors, particularly MGC [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Accurate differentiation is critical because the treatment and prognosis of SGC and MGC differ significantly [

4]. This study reports the first documented case of EMPSGC in a dog, highlighting the use of IHC markers to distinguish [

16] between these tumors and offering insights into the clinical management of similar cases in veterinary practice.

The IHC markers CK19 and Sox9 were pivotal in this case, allowing for a clear differentiation between SGC and MGC, thereby ensuring accurate diagnosis and proper clinical management. CK19, a well-known marker for adnexal tumors [

6,

7,

8], and Sox9 [

9,

10,

11], a transcription factor involved in glandular differentiation, played a pivotal role in con-firming the sweat gland origin of the tumor in case 1. which the great sensitivity and specificity with SGC [

11] and immunoreactivity pattern was nuclear and mostly located in basaloid cells of the tumor nest [

9] that similar as our sweat gland case, palisading cells were readily positive for SOX9 while mammary gland showed negative result. This finding is essential given the overlapping histological features of SGC and MGC, particularly in tumors located near mammary tissue.

In addition to CK19 and Sox9, synaptophysin staining revealed neuroendocrine dif-ferentiation [

5,

12,

13], a hallmark of EMPSGC, further supporting the diagnosis. Neuro-endocrine differentiation is unusual in typical sweat gland tumors, making this case unique. The absence of estrogen receptor (ER) expression in case 1, which is often positive in mammary gland tumors, further confirmed the sweat gland origin of the tumor. These findings are consistent with human cases of EMPSGC, although species-specific differences may exist, such as the variation in hormonal receptor expression.

This case underscores the importance of employing a comprehensive IHC panel to distinguish between SGC and MGC. Misdiagnosis can lead to inappropriate treatment [

4]. and negatively impact patient outcomes, as these tumors have different therapeutic protocols [

12]. The IHC panel used in this study, including markers such as CK19, Sox9, p63, and synaptophysin, provided a reliable method for differentiating between these neo-plasms and offered crucial diagnostic clarity.

From a clinical perspective, the surgical excision of the tumor in Case 1 resulted in a favorable outcome, with no signs of recurrence during follow-up. This suggests that complete surgical removal may be effective treatment [

16,

17] for EMPSGC in dogs. While recurrence has been reported in human cases of EMPSGC [

17], the absence of recurrence in this canine case is encouraging, though long-term follow-up remains essential to fully understand the tumor's behavior in animals. Given the limited data on EMPSGC in veterinary medicine, future studies are necessary to investigate the long-term prognosis and potential for metastasis or recurrence in similar cases.

This case also contributes to the broader understanding of adnexal tumors in veterinary oncology. As the World Health Organization (WHO) continues to update the Classification of Skin Tumors, particularly in the 4th edition, this report supports the need for detailed histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluation of skin tumors in animals [

5]. The identification of reliable IHC markers such as CK19 and Sox9 adds to the diagnostic toolkit for veterinarians, allowing for more accurate differentiation of skin adnexal tumors, including rare neoplasms like EMPSGC.

In conclusion, this report provides valuable insights into the diagnosis and clinical management of EMPSGC in dogs, representing the first documented case in veterinary literature. By highlighting the diagnostic utility of IHC markers such as CK19, Sox9, and synaptophysin, this study offers a framework for the accurate diagnosis of rare adnexal tumors. The findings underscore the importance of a multidisciplinary diagnostic ap-proach and contribute to the growing body of knowledge regarding the behavior and management of EMPSGC in animals. Future research should focus on the biological be-havior and optimal treatment strategies for EMPSGC, as well as further exploration of its occurrence in other species.

5. Conclusions

This study documents the first case of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) in a dog, successfully differentiating it from MGC using immunohistochemical markers such as CK19, Sox9, and synaptophysin. Accurate diagnosis is crucial due to the differing treatment strategies for these tumors. Surgical excision led to a favorable outcome with no recurrence observed. While rare, EMPSGC requires further study to understand its long-term behavior and optimal treatment in veterinary medicine.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Son HY; Formal analysis: Tangchang W, Jung GY; Funding acquisition: Son HY; Methodology: Tangchang W, Kim DH, and Kwon HJ; Supervision: Son HY; Writing - original draft: Tangchang W, Song JY, Kumbukgahadeniya P; Writing - review & editing: Kwon HJ, Son HY. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the owner of the animal involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Biggs LC, Mikkola ML. Early inductive events in ectodermal appendage morphogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014, 25-26, 11-21.

- Mentrikoski MJ, Wick MR. Immunohistochemical distinction of primary sweat gland carcinoma and metastatic breast carcinoma: can it always be accomplished reliably?. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015, 143(3), 430-436.

- Khan YS, Fakoya AO, Sajjad H. Anatomy, Thorax, Mammary Gland. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing:Treasure Island (FL), 2023.

- Rollins-Raval M, Chivukula M, Tseng GC, Jukic D, Dabbs DJ. An immunohistochemical panel to differentiate metastatic breast carcinoma to skin from primary sweat gland carcinomas with a review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011, 135(8), 975-983.

- Brenn T. Do not break a sweat: avoiding pitfalls in the diagnosis of sweat gland tumors. Mod Pathol. 2020, 33(Suppl 1), 25-41.

- Zhou X, Li G, Wang D, Sun X, Li X. Cytokeratin expression in epidermal stem cells in skin adnexal tumors. Oncol Lett. 2019, 17(1), 927-932.

- Lei YH, Li X, Zhang JQ, Zhao JY. Important immunohistochemical markers for identifying sweat glands. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013, 126(7), 1370-1377.

- Goto K, Ishikawa M, Hamada K, et al. Comparison of Immunohistochemical Expression of Cytokeratin 19, c-KIT, BerEP4, GATA3, and NUTM1 Between Porocarcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021, 43(11), 781-787.

- Vidal VP, Ortonne N, Schedl A. SOX9 expression is a general marker of basal cell carcinoma and adnexal-related neoplasms. J Cutan Pathol. 2008, 35(4), 373-379.

- Shi G, Sohn KC, Li Z, et al. Expression and functional role of Sox9 in human epidermal keratinocytes. PLoS One. 2013, 8(1), e54355.

- Nishimura Y, Ryo E, Inoue S, et al. Strategic Approach to Heterogeneity Analysis of Cutaneous Adnexal Carcinomas Using Computational Pathology and Genomics. JID Innov. 2023, 3(6), 100229.

- Agni M, Raven ML, Bowen RC, et al. An Update on Endocrine Mucin-producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma: Clinicopathologic Study of 63 Cases and Comparative Analysis. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020, 44(8), 1005-1016.

- Zembowicz A, Garcia CF, Tannous ZS, Mihm MC, Koerner F, Pilch BZ. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma: twelve new cases suggest that it is a precursor of some invasive mucinous carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005, 29(10), 1330-1339.

- Flieder A, Koerner FC, Pilch BZ, Maluf HM. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma: a cutaneous neoplasm analogous to solid papillary carcinoma of breast. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997, 21(12), 1501-1506.

- Adiputra PAT, Sudarsa IW, Irawan H, Saputra H. Malignant adnexal tumor of the skin on breast: A case report of apocrine carcinoma. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2023, 108, 108383.

- Brett MA, Salama S, Gohla G, Alowami S. Endocrine Mucin-Producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma, a Histological Challenge. Case Rep Pathol. 2017, 2017, 6343709.

- Chang S, Shim SH, Joo M, Kim H, Kim YK. A case of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma co-existing with mucinous carcinoma: a case report. J Pathol Transl Med. 2010, 44(1), 97–100.

Figure 1.

Gross finding figure. (A) The skin shows bluish discoloration, and numerous nodules form irregular mass that protrude into the skin of case 1. (B) Removed tumor mass from case 1, The mass is firmly adhered to the skin and subcutaneous connective tissue. (C) A removed mass (7x6cm) in the right 2nd mammary gland from case 2.

Figure 1.

Gross finding figure. (A) The skin shows bluish discoloration, and numerous nodules form irregular mass that protrude into the skin of case 1. (B) Removed tumor mass from case 1, The mass is firmly adhered to the skin and subcutaneous connective tissue. (C) A removed mass (7x6cm) in the right 2nd mammary gland from case 2.

Figure 2.

Histological examination of both cases. (A) The tumor displayed a thickened stroma of lobular. Lymphovascular invasion was found in interstitial lobular area. Pseudorosettes, cribriforming in the solid areas could be observed from case 1, Mag.=X100. (B) Within the lobules, peripheral palisading was identified in some areas. Nuclei were bland with moderate pleomorphism and diffusely stippled chromatin from case 1, Mag.=X400. (C) The irregular proliferation of small glands of case 2, Mag.=X100. (D) The tubules lined by a single layer of cuboidal or columnar cell hyperplasia with atypia of case 2, Mag.=X400., Hematoxylin and eosin (HE).

Figure 2.

Histological examination of both cases. (A) The tumor displayed a thickened stroma of lobular. Lymphovascular invasion was found in interstitial lobular area. Pseudorosettes, cribriforming in the solid areas could be observed from case 1, Mag.=X100. (B) Within the lobules, peripheral palisading was identified in some areas. Nuclei were bland with moderate pleomorphism and diffusely stippled chromatin from case 1, Mag.=X400. (C) The irregular proliferation of small glands of case 2, Mag.=X100. (D) The tubules lined by a single layer of cuboidal or columnar cell hyperplasia with atypia of case 2, Mag.=X400., Hematoxylin and eosin (HE).

Figure 3.

Immunoreactivity of Cytokeratin (CK). Case 1 (Sweat gland carcinoma), (A) lumino-basal tumor cells were positive for CK5, (B) Luminal tumor cells were positive for AE1/AE3+CK8/18, (C) CK19 was cytoplasmic, and cell membrane expression. Case 2 (Mammary gland carcinoma), (D) CK5 was positive, (E) AE1/AE3+CK8/18 and (F) CK19 shown no immunoreactivities., Immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Figure 3.

Immunoreactivity of Cytokeratin (CK). Case 1 (Sweat gland carcinoma), (A) lumino-basal tumor cells were positive for CK5, (B) Luminal tumor cells were positive for AE1/AE3+CK8/18, (C) CK19 was cytoplasmic, and cell membrane expression. Case 2 (Mammary gland carcinoma), (D) CK5 was positive, (E) AE1/AE3+CK8/18 and (F) CK19 shown no immunoreactivities., Immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Figure 4.

Immunoreactivity of myoepithelial and other markers. Case 1 (Sweat gland carcinoma), (A) nuclear was positive for p63, (B) Cytoplasmic areas were positive for vimentin, (C) Sox9 found nuclear expression. Case 2 (Mammary gland carcinoma), (D) p63 and (E) Vimentin were myoepithelial cell positive, and (F) Sox9 was negative expression., Immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Figure 4.

Immunoreactivity of myoepithelial and other markers. Case 1 (Sweat gland carcinoma), (A) nuclear was positive for p63, (B) Cytoplasmic areas were positive for vimentin, (C) Sox9 found nuclear expression. Case 2 (Mammary gland carcinoma), (D) p63 and (E) Vimentin were myoepithelial cell positive, and (F) Sox9 was negative expression., Immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Figure 5.

Immunoreactivity of endocrine and other markers. Case 1 (Sweat gland carcinoma), (A) Membranous and cytoplasmic areas were positive for E-cadherins, (B) Cytoplasmic expression of synaptophysin, (C) nuclear was negative for estrogen. Case 2 (Mammary gland carcinoma), (D) E-cadherins was negative expression, (E) Synaptophysin was cytoplasmic expression, and (F) nuclear cell shown positive for estrogen., Immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Figure 5.

Immunoreactivity of endocrine and other markers. Case 1 (Sweat gland carcinoma), (A) Membranous and cytoplasmic areas were positive for E-cadherins, (B) Cytoplasmic expression of synaptophysin, (C) nuclear was negative for estrogen. Case 2 (Mammary gland carcinoma), (D) E-cadherins was negative expression, (E) Synaptophysin was cytoplasmic expression, and (F) nuclear cell shown positive for estrogen., Immunohistochemistry (IHC).

Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry Antibody Information.

Table 1.

Immunohistochemistry Antibody Information.

| Antibody |

Clonality1

|

Clone |

Species |

Source of Antibody |

Dilution |

| CK5 |

mAb |

ab52635 |

rabbit |

abcam |

1:200 |

| AE1/3+CK8/18 |

mlAb |

ab86734 |

mouse |

abcam |

1:250 |

| p63 |

mAb |

ab124762 |

rabbit |

abcam |

1:1000 |

| Vimentin |

mAb |

MAB3400 |

mouse |

Sigma-Aldrich |

1:200 |

| Sox9 |

mAb |

ab185966 |

rabbit |

abcam |

1:1000 |

| Synaptophysin |

mAb |

ab32127 |

rabbit |

abcam |

1:100 |

| Estrogen |

mAb |

ab32063 |

rabbit |

abcam |

1:250 |

| E-cadherin |

mAb |

4A2 |

mouse |

Cell Signaling Technology |

1:200 |

| CK19 |

mAb |

D7F7W |

mouse |

Cell Signaling Technology |

1:100 |

Table 2.

Comparative of Immunohistochemical (IHC) results between sweat gland carcinoma (SGC) and mammary gland carcinoma (MGC).

Table 2.

Comparative of Immunohistochemical (IHC) results between sweat gland carcinoma (SGC) and mammary gland carcinoma (MGC).

| IHC marker |

SGC |

MGC |

| Type of marker1 |

Name |

Area2 |

B |

L |

M |

S |

B |

L |

M |

S |

| B, L and M cell |

CK5 |

Cy |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

| B and M cell |

p63 |

N |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

| Vimentin |

Cy |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

| L cell |

AE1/3+CK8/18 |

C, Cy |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Epithelial cells |

E-cadherin |

C |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Neuroendocrine |

Synaptophysin |

Cy |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

| Hormone |

Estrogen |

N |

- |

- |

- |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

| Sweat gland |

CK19 |

C, Cy |

+ |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Sox9 |

N |

+ |

- |

+ |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).