Submitted:

25 October 2024

Posted:

29 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- This paper introduces a novel and efficient population-based algorithm called ENHCOVIDOA, tailored to address the multi-objective operational cost function during the operation phase. The algorithm excels at handling the intricate trade-offs involved in the operation of generators and renewable energy sources (RES), including factors such as costs, emissions, network losses, and voltage deviations.

- The proposed algorithm is capable of solving a broad spectrum of OPF problems for IEEE 30-bus and 57-bus standard power systems, achieving better results than algorithms of other literature both with and without the presence of distributed generation.

- This study accounts for uncertainties in the output of RES while formulating the probabilistic MO-OPF problem, using TPEM to improve the accuracy of the objectives by calculating mean and standard deviation of objectives.

- Calculate the multi-objective OPF for a reality 28 buses system from Iraq and analyze the impact of renewable energy uncertainty on the system's objectives.

2. The Non-Linear Mathematical Model for the OPF Problem

2.2. Control Variables

2.3. Objective Functions

2.4. The Constraints of Optimal Power Flow

2.5. Composite Objective Function

2.6. Constraint Handling

3. The Uncertainty of Renewable Energy Resorces

3.1. Uncertainty Modeling of Solar Irradiance

3.2. Uncertainty Modeling of Wind Speed

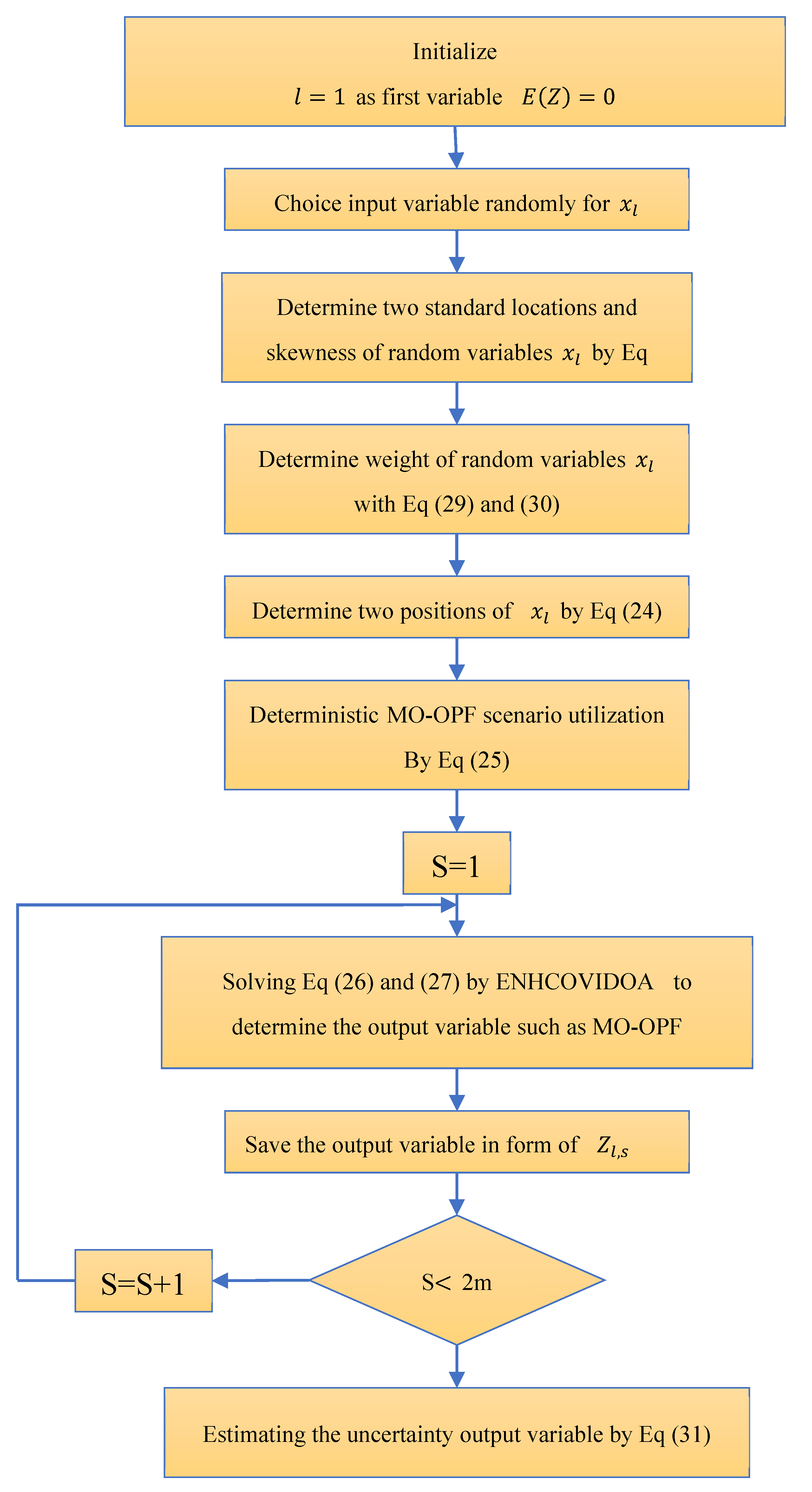

4. Two Point Estimation Method (TPEM) and Optimization Methods

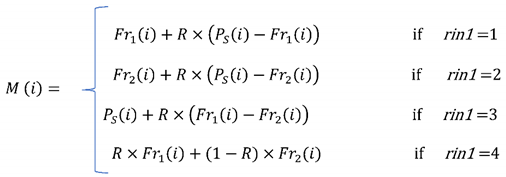

4.1. Two Point Estimation Method

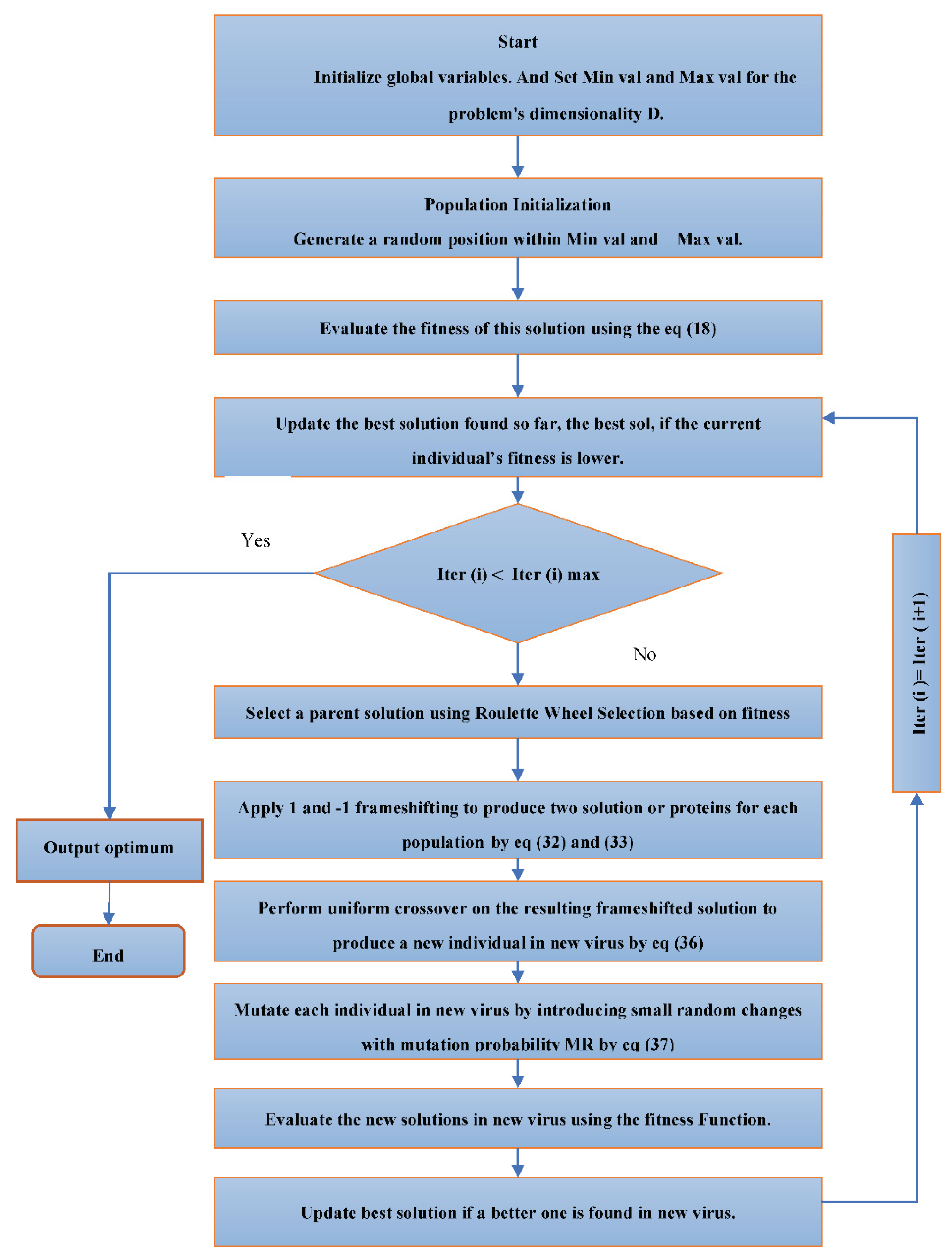

4.2. COVID Optimization Algorithm (COVIDOA)

4.2.1. Initialization:

4.2.2. Virus Replication Phase with Frameshifting Technique:

-

Frameshifting Process:

- If the +1 frameshifting technique is employed, the values of the parent solution are shifted one position to the right, and the first position is assigned a random value within the range ]. The protein is then determined by:where and represent the minimum and maximum possible values for the variables in each solution [11].

- If the −1 frameshifting technique is employed, the values of the parent solution are shifted one position to the left, and the value in the last position is randomly assigned within the range []. The protein is then computed as:

- In this context, denotes the k-th generated protein, is the parent solution, and D is the problem dimension (the number of variables in each solution). The outcome of the frameshifting technique is a new protein sequence.

-

New Virion Formation:

- A uniform crossover technique is applied to the newly generated sub-proteins to produce a new virion (new solution).Where , are the first and second proteins after applying Frameshifting in COVIDOA and is a random value in the range []. is the th elements of new virion or solutions

4.2.3. Mutation:

4.2.4. Evaluation and Update:

4.3. Enhanced Coronavirus Optimization Algorithm (ENHCOVIDOA)

5. Simulation Results and Discussion

5.1. The Analyzed Cases for the IEEE 30-Bus System

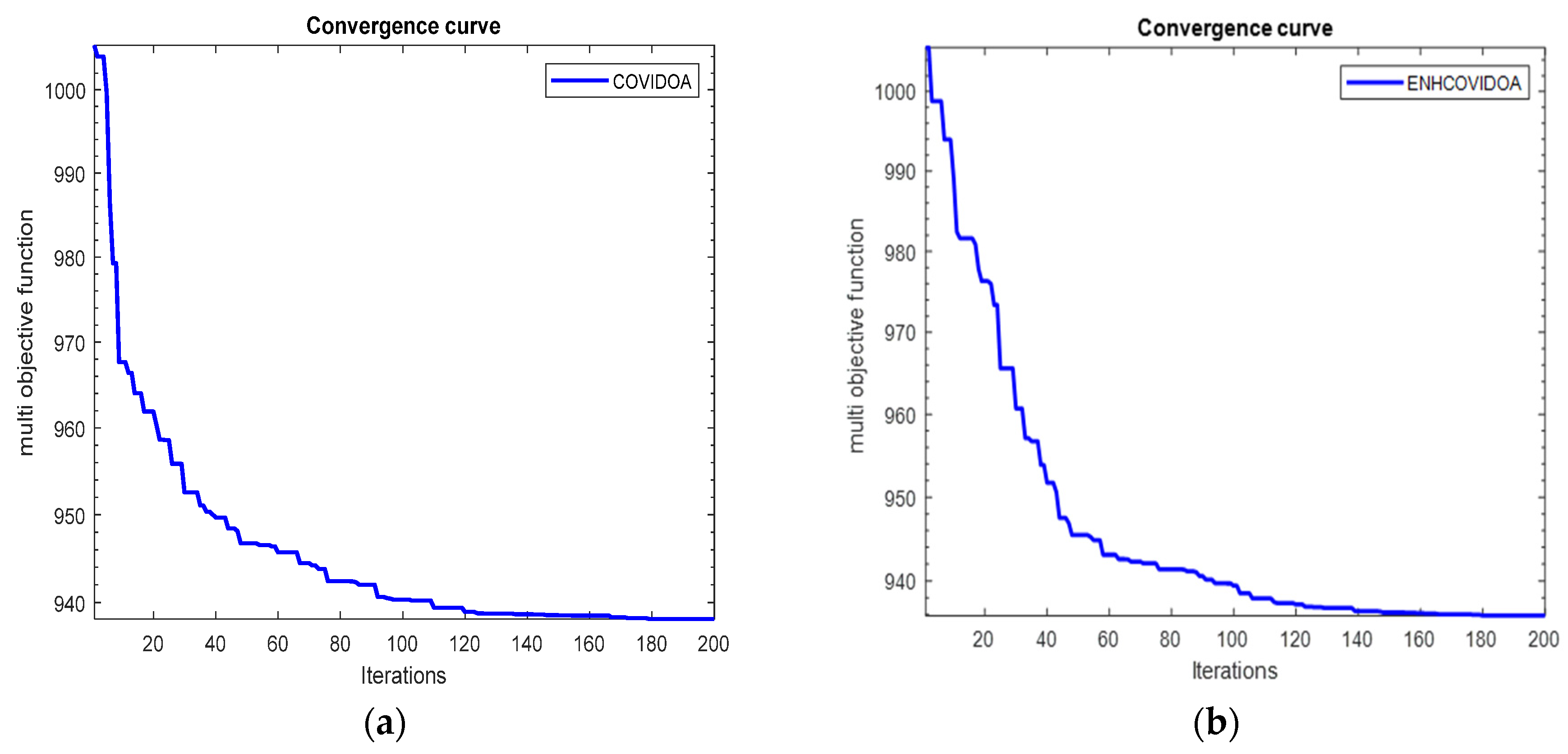

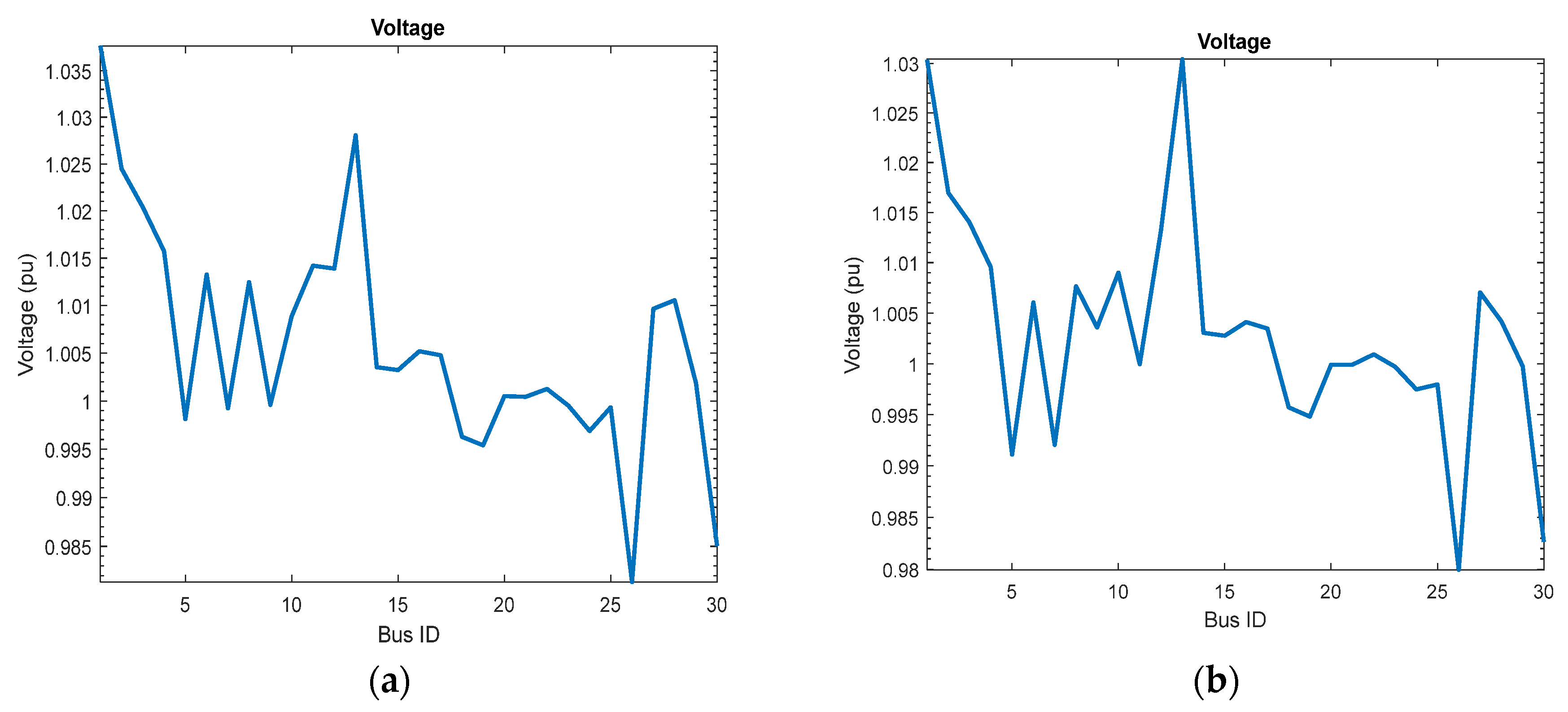

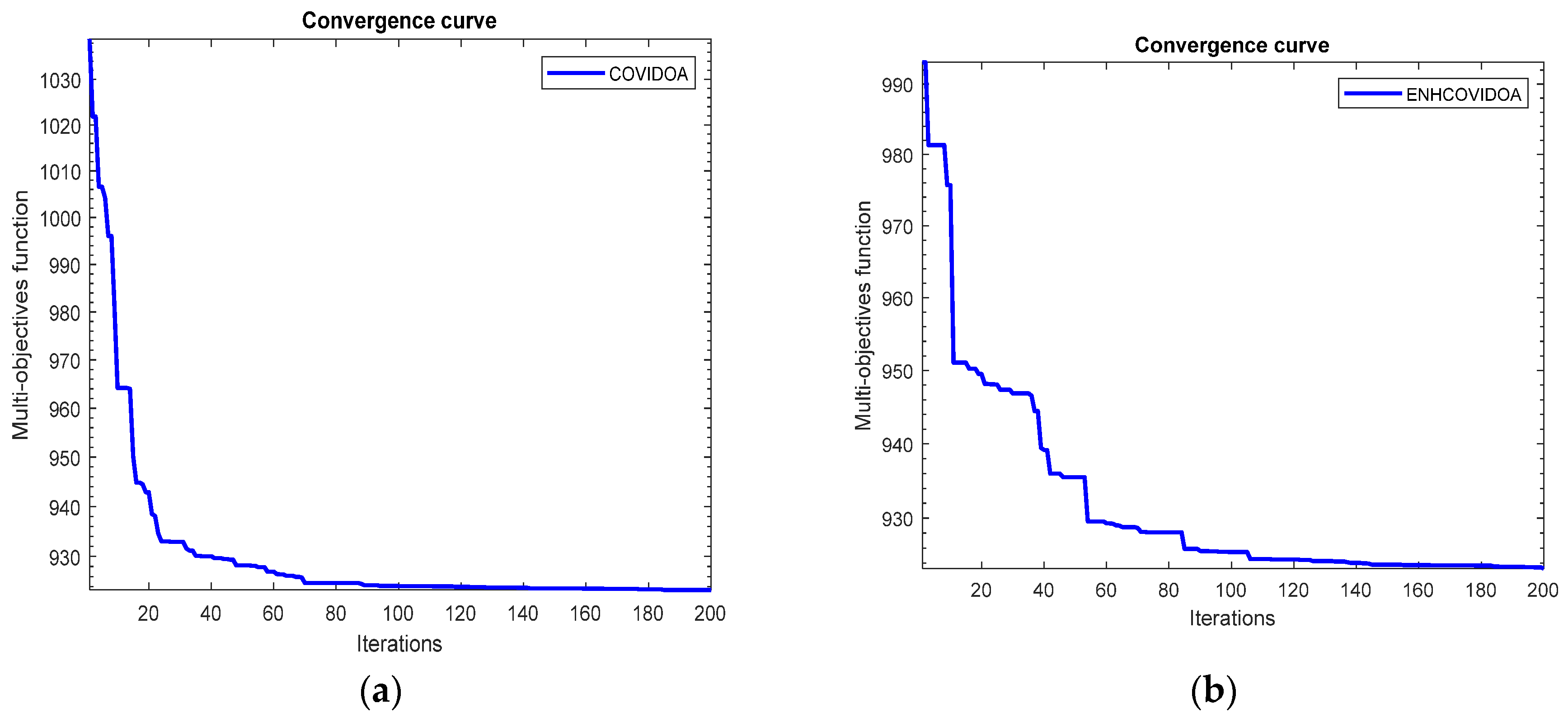

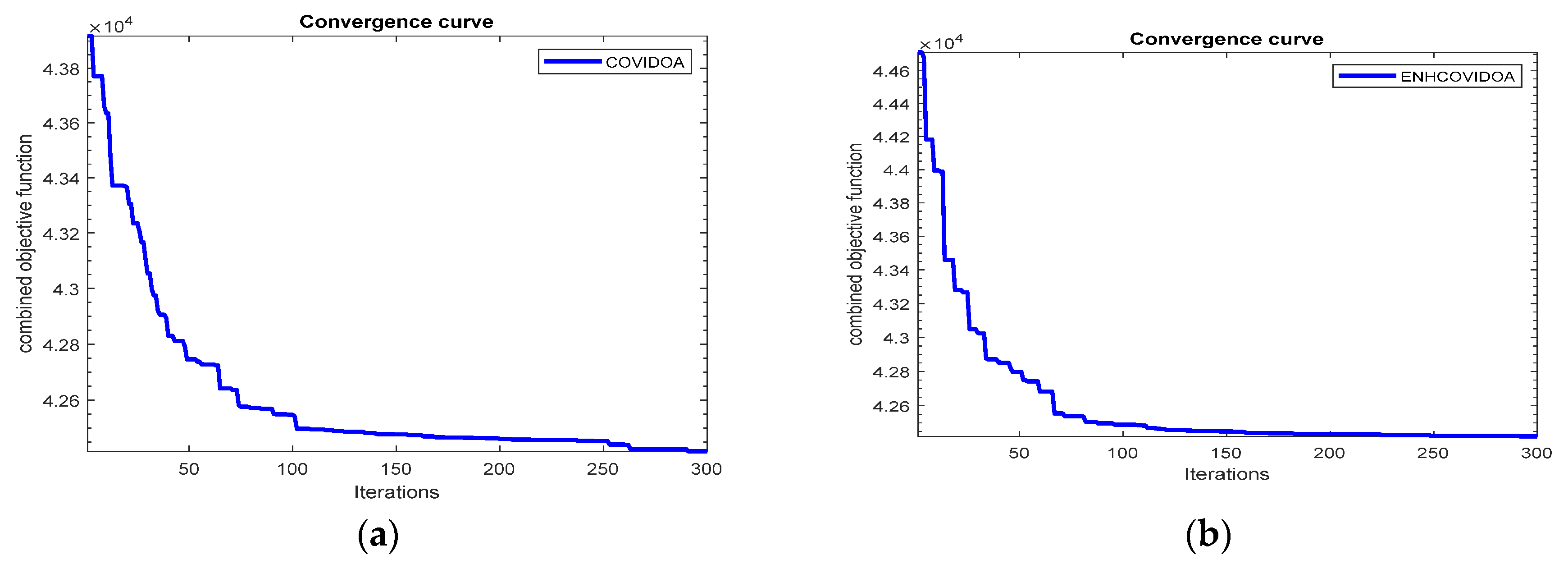

- Case 1: Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses without DG by COVIDOA.

- Case 2: Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses without DG by ENHCOVIDOA .

- Case 3: Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses with DG by COVIDOA.

- Case 4: Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses with DG by ENHCOVIDOA .

- Case 5: Estimating multiple objectives, including fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation, and losses under the uncertainty of DG by using TPEM & ENHCOVIDOA.

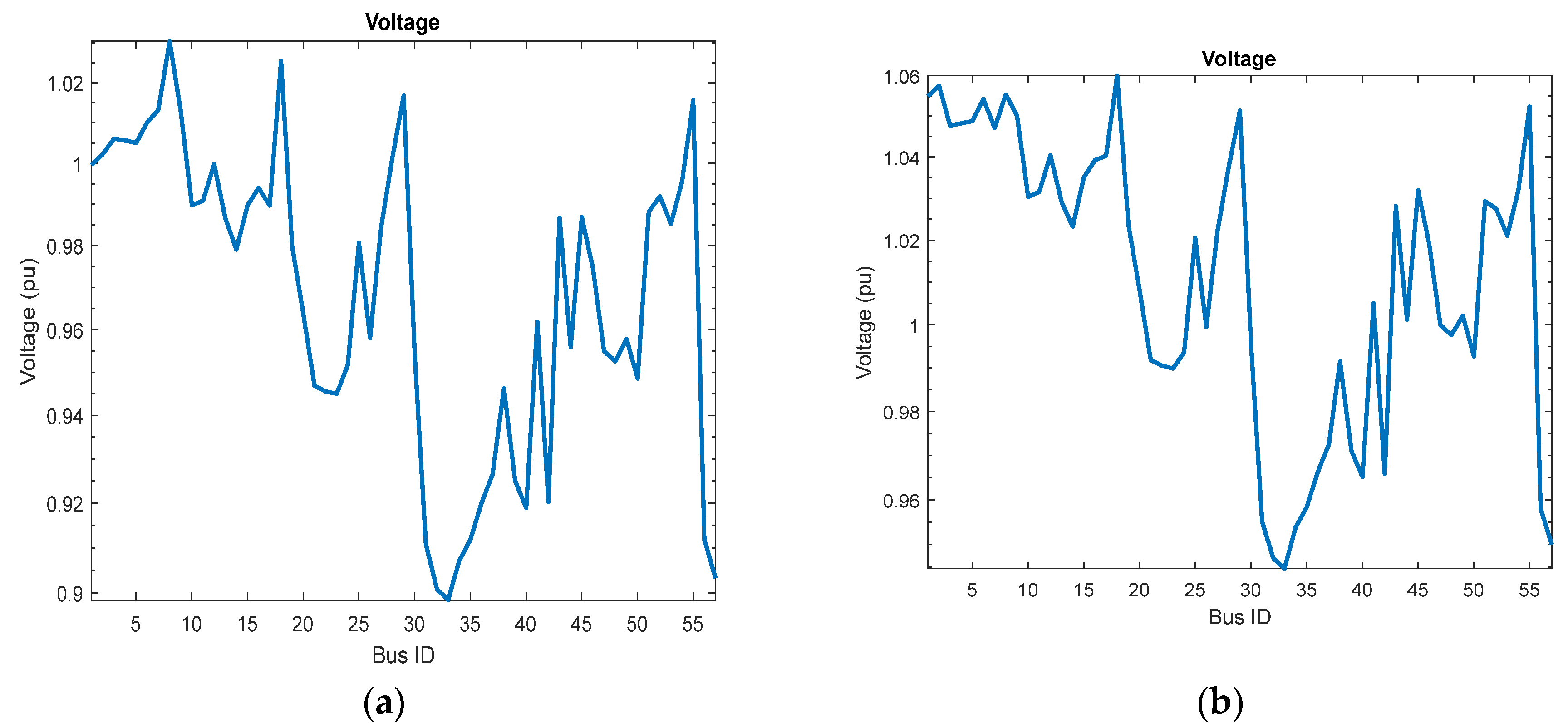

5.2. The Analyzed Cases for the IEEE 57-Bus System

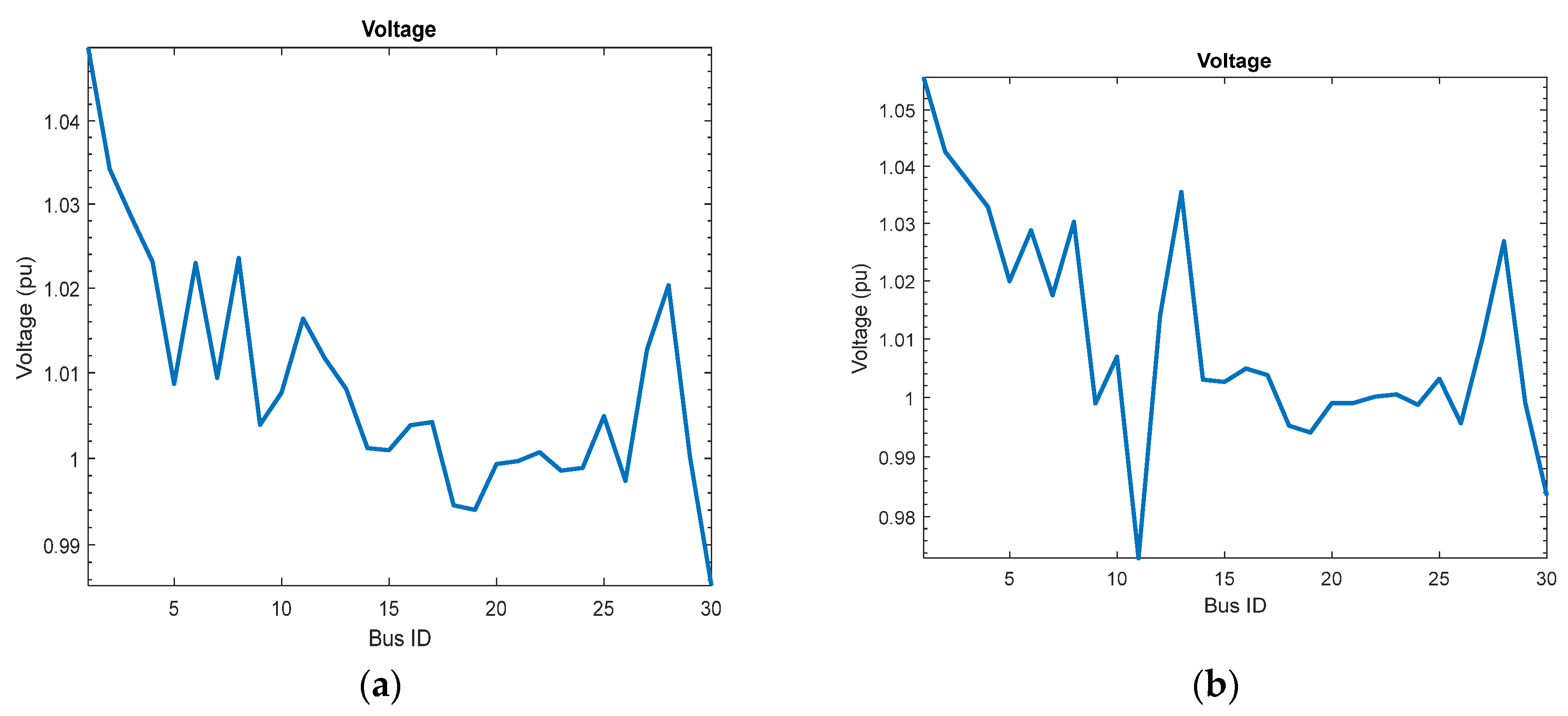

- Case 6: Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses without DG by COVIDOA.

- Case 7: Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses without DG by ENH COVIDOA .

- Case 8: Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses with DG by COVIDOA.

- Case 9 : Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses with DG by ENHCOVIDOA .

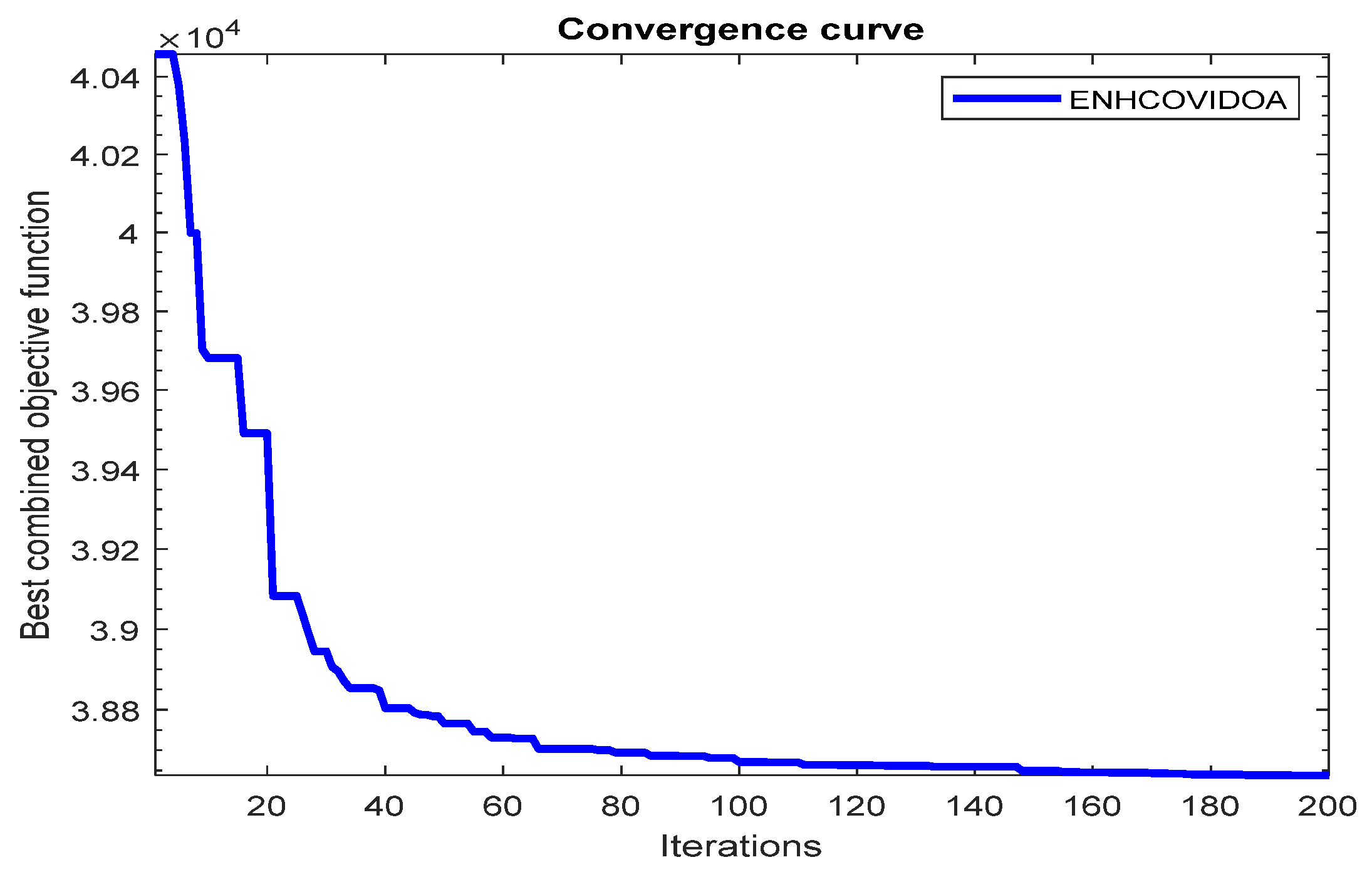

- Case 10: Estimating multiple objectives, including fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation, and losses under the uncertainty of DG by using TPEM & ENHCOVIDOA.

5.3. The Analyzed Cases for SISGHV-28 Buses System

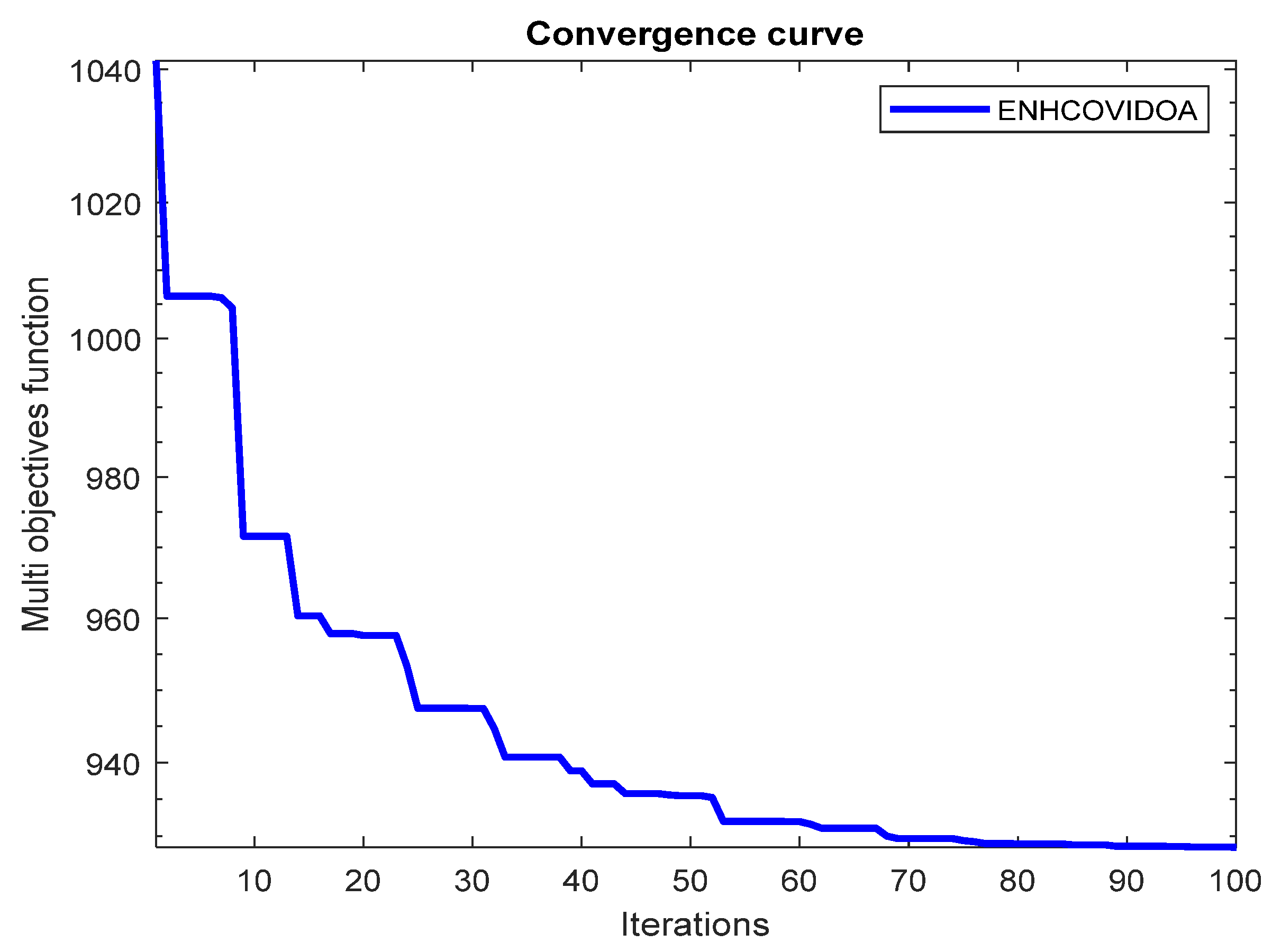

- Case 11 : Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses without DG by ENH COVIDOA.

- Case 12 : Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses with DG by ENH COVIDOA.

- Case 13 : Estimating multiple objectives, including fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation, and losses under the uncertainty of DG by using TPEM & ENHCOVIDOA.

- Case (1&2) : IEEE 30-Bus System Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses without DG by COVIDOA in case1& ENHCOVIDOA for case2 .

- Case (3&4): IEEE 30-Bus System Minimizing multi objectivesof OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses with DG by COVIDOA in case3& ENHCOVIDOA for case4.

- Case 5: IEEE 30-Bus System Estimating multiple objectives, including fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation, and losses under the uncertainty of DG by using TPEM-ENHCOVIDOA

- Case (6&7): IEEE 57-Bus System Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses without DG by COVIDOA in case 6 & ENHCOVIDOA for case7 .

- Case (8 & 9): IEEE 57-Bus System Minimizing multi objectives of OPF the fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation and losses with DG by COVIDOA in case 8 &ENHCOVIDOA for case9 .

- Case 10 : IEEE 57-Bus System Estimatingmultiple objectives, including fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation, and losses under the uncertainty of DG by using TPEM & ENHCOVIDOA

- Cases (11,12&13) : SISGHV-28 buses systemEstimating multiple objectives, including fuel cost, emissions, voltage deviation, and losses under the uncertainty of DG by using TPEM & ENHCOVIDOA.

6. Conclusion

- The ENHCOVIDOA enhances search ability in high-dimensional problems like multi-objective of OPF. In case 1&2 of the IEEE 30-Bus and case 6&7 of the IEEE 57 system, ENHCOVIDOA reduces fuel cost, emissions, and voltage deviation for 30 Bus by (0.5258%, 1.7966%, and 12.1419%) and for 57 Bus by (0.1643%, 0.0641%, and 0.9715%) when compared to the original COVIDOA without present DG.

- The effectiveness of the proposed ENHCOVIDOA method, enhanced for optimizing multi-objective OPF problems, particularly in the presence of renewable energy generation such as wind and solar as DG is certainty. As highlighted by the results, significant reductions in fuel cost, emissions, and voltage deviation were achieved. For the IEEE 30 Bus system, in cases (3&4) these reductions were 0.3076%, 2.5168%, and 6.0630% respectively, while for the IEEE 57 Bus system, in cases (8 & 9) the reductions were 0.1400%, 0.2667%, and 1.7734%, respectively, when compared to the results of the COVIDOA method. Moreover, ENHCOVIDOA outperforms other algorithms from the literature, as demonstrated by the data presented in the tables.

- In cases 5 and 10, a new methodology was introduced to solve the MOPF problem under uncertain renewable generation using the TPEM. The results highlight the superior performance of the TPEM-ENHCOVIDOA, providing greater accuracy and more optimal outcomes. This led to significant annual fuel cost savings, with $87,772.94 for the IEEE 30 Bus system and $391,246.87 for the IEEE 57 Bus system, compared to cases 4 and 9, which did not incorporate TPEM.

- In Cases 12 and 13, the effectiveness of the proposed TPEM-ENHCOVIDOA method was tested using a reality system from Iraq's SISGHV-28 Buses, both with and without DG. The method successfully optimized multiple objectives, resulting in annual fuel cost savings of $2,493,881.40.

- Based on the presented information, the algorithm is also scalable for larger systems and has shown competitive performance, as evidenced by the results.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

| Abbreviations and Acronyms | Description |

| Selected objective function | |

| Total no. of objective functions | |

| Equality constraints | |

| Inequality constraints | |

| a and b | The state and control variable. |

| Apparent power flow of transmission line | |

| The total generation cost function | |

| The total emission functions | |

| Active and reactive power output generation | |

| The demand for active and reactive power at the load bus | |

| The total voltage deviation function | |

| The voltage magnitude of generation | |

| The voltage magnitude for bus | |

| Voltage reference equal to 1.0 per unit | |

| The voltage magnitude for transmission line | |

| Cost coefficients of the th generator | |

| Emission coefficients | |

| Reactive power of the VAR source | |

| COVIDOA | Coronavirus Disease Optimization Algorithm |

| ENHCOVIDOA | Enhanced Coronavirus Disease Optimization Algorithm |

| COA | Cuckoo optimization algorithm |

| MCOA | The modified Cuckoo optimization algorithm |

| TFWO | Turbulent flow of a water-based optimizer |

| SMA | SlimeMould Algorithm |

| J-PPS | Jaya algorithm and Powell’s Pattern Search |

| Jaya | Jaya algorithm |

| TLBO | Teaching–learning-based optimization |

| AGTLBO | Adaptive Gaussian Teaching–learning-based optimization |

| HHO | Harris Hawks Optimization |

| PSO-SSO | Particle swarm optimization with slap swarm optimization |

| DA | Dragonfly Algorithm |

| GWO | Grey Wolf Optimization |

| MODA | Multi-objective dragon fly |

| MOICA | Multi-objective imperialist competitive algorithm |

| MOMICA | Multi-Objective Modified Imperialist Competitive Algorith |

Appendix A

| Fuel cost coefficient | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | G2 | G5 | G8 | G11 | G13 | ||

| a | 0.00375 | 0.0175 | 0.0625 | 0.00834 | 0.025 | 0.025 | |

| b | 2 | 1.75 | 1 | 3.25 | 3 | 3 | |

| c | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Emission coefficient | |||||||

| 4.091 | 2.543 | 4.258 | 5.326 | 4.258 | 6.131 | ||

| -5.554 | -6.047 | -5.094 | -3.55 | -5.094 | -5.555 | ||

| 6.49 | 5.638 | 4.586 | 3.38 | 4.586 | 5.151 | ||

| 2.00 | 5.00 | 1.00 | 2.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 2.857 | 3.33 | 8 | 2 | 8 | 6.67 | ||

| Fuel cost coefficient | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | G2 | G3 | G6 | G8 | G9 | G12 | |

| a | 0.0775795 | 0.01 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.0222222222 | 0.01 | 0.0322580645 |

| b | 20 | 40 | 20 | 40 | 20 | 40 | 20 |

| c | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Emission coefficient | |||||||

| 4.091 | 2.543 | 6.131 | 3.491 | 4.258 | 2.754 | 5.326 | |

| -5.554 | -6.047 | -5.555 | -5.754 | -5.094 | -5.847 | -3.555 | |

| 6.49 | 5.638 | 5.151 | 6.39 | 4.586 | 5.238 | 3.38 | |

| 2.00 | 5.00 | 1.00 | 3.00 | 1.00 | 4.00 | 0.002 | |

| 0.286 | 0.333 | 0.667 | 0.266 | 0.8 | 0.288 | 0.2 | |

| Generator | a | b | c | |

| 1 | 275 | 0.35 | 0.0012 | |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | 200 | 3.5 | 0.04 | |

| 4 | 2581 | 2.155 | 0.05 | |

| 5 | 1698 | 11.91 | 0.03 | |

| 6 | 154 | 7.05 | 0.0136 | |

| 7 | 200 | 0.64 | 0.0017 | |

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 | 250 | 0.5 | 0.02 | |

| 10 | 300 | 2.2 | 0.003 | |

| 11 12 13 14 |

200 159 120 685 |

0.652 0.561 0.8 3.1 |

0.002 0.002 0.0025 0.0158 |

| Generator | |||||

| 1 | 2.543 | -6.047 | 5.638 | 0.00005 | 0.5047 |

| 2 | 4.091 | -5.554 | 6.490 | 0.00042 | 0.000288 |

| 3 | 3.123 | -6.085 | 5.643 | 0.0003 | 0.376 |

| 4 | 3.642 | -3.441 | 3.564 | 0.0001 | 0.045 |

| 5 | 4.785 | -1.765 | 3.432 | 0.0002 | 0.287 |

| 6 | 3.765 | -5.333 | 6.543 | 0.00065 | 0.34 |

| 7 | 3.456 | -3.567 | 4.485 | 0.000032 | 0.0076 |

| 8 | 2.473 | -2.084 | 3.538 | 0.000132 | 0.043 |

| 9 | 3.258 | -2.084 | 6.566 | 0.000002 | 0.054 |

| 10 | 1.416 | -6.510 | 2.310 | 0.0001 | 0.68 |

| 11 12 13 14 |

3.255 4.221 2.198 6.456 |

-5.064 -6.333 -4.542 -4.441 |

3.555 3.231 1.586 3.131 |

0.0005 0.000014 0.0004 0.00001 |

0.098 0.57 0.012 0.266 |

| Bus | Voltage Mag(pu) | Voltage Ang(deg) | Generation P (MW) |

Generation Q (MVAr) |

Load P (MW) |

Load Q (MVAr) |

| 1 | 1.039 | 0.000 | 159.40 | 2347.40 | 206.00 | 56.00 |

| 2 | 1.020 | 9.525 | 396.59 | 77.77 | - | - |

| 3 | 1.010 | 7.695 | 282.29 | -46.24 | 150.00 | 75.00 |

| 4 | 1.020 | 6.74 | 347.61 | -84.12 | 125.00 | 93.00 |

| 5 | 1.020 | 6.792 | -0.00 | -25.51 | - | - |

| 6 | 1.020 | -0.773 | 247.07 | -112.80 | 130.00 | 10.00 |

| 7 | 1.010 | 2.645 | 1390.76 | 162.09 | - | - |

| 8 | 1.020 | 0.243 | 382.55 | -75.50 | 200.00 | 50.00 |

| 9 | 1.020 | -0.654 | 564.91 | -1946.89 | - | - |

| 10 | 1.030 | 1.618 | 351.72 | 34.22 | - | - |

| 11 | 1.030 | -2.117 | 266.86 | -77.00 | - | - |

| 12 | 1.020 | -9.663 | 572.14 | -85.11 | 423.00 | 101.00 |

| 13 | 1.010 | -9.48 | 605.83 | 78.51 | 155.00 | 72.00 |

| 14 | 1.010 | 7.252 | 445.07 | 48.50 | 200.00 | 101.00 |

| 15 | 1.011 | -1.251 | - | - | 650.00 | 302.00 |

| 16 | 1.020 | -0.947 | - | - | - | - |

| 17 | 1.004 | -1.802 | - | - | 576.00 | 302.00 |

| 18 | 1.006 | -1.583 | - | - | 849.00 | 295.00 |

| 19 | 1.008 | -0.533 | - | - | 413.00 | 149.00 |

| 20 | 1.014 | -1.278 | - | - | 127.00 | 56.00 |

| 21 | 1.005 | -1.528 | - | - | 50.00 | 182.00 |

| 22 | 1.004 | -1.953 | - | - | 84.00 | 22.0 |

| 23 | 1.022 | -2.023 | - | - | 260.00 | 108.00 |

| 24 | 1.016 | -1.438 | - | - | 109.00 | 40.00 |

| 25 | 1.032 | -0.650 | - | - | 308.00 | 185.00 |

| 26 | 1.026 | -1.080 | - | - | 213.00 | 152.00 |

| 27 | 0.998 | -3.604 | - | - | 311.00 | 161.00 |

| 28 | 1.005 | -0.693 | - | - | 455.00 | 145.00 |

| Branch # | From Bus |

To Bus |

From Bus P (MW) |

Injection Q (MVAr) |

To Bus P (MW) |

Injection Q (MVAr) |

Loss P (MW) |

Loss Q (MVAr) |

| 1 | 15 | 2 | -197.71 | -71.63 | 198.3 | 38.88 | 0.591 | 4.83 |

| 2 | 15 | 3 | -135.63 | -3.22 | 135.95 | -42.66 | 0.328 | 2.98 |

| 3 | 15 | 4 | -67.7 | -72.53 | 67.91 | -35.55 | 0.202 | 1.65 |

| 4 | 15 | 6 | -51.26 | -82.99 | 51.4 | -54.16 | 0.138 | 1.26 |

| 5 | 3 | 4 | -3.67 | -78.58 | 3.7 | -12.49 | 0.036 | 0.33 |

| 6 | 4 | 5 | 0 | -0.3 | 0 | -0.3 | 0 | 0 |

| 7 | 4 | 17 | 76.5 | -38.96 | -76.19 | -91.6 | 0.31 | 2.82 |

| 8 | 4 | 17 | 74.5 | -41.54 | -74.2 | -92.68 | 0.302 | 2.75 |

| 9 | 4 | 8 | 0 | -48.28 | 0 | -48.28 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | 5 | 6 | 0 | -25.2 | 0 | -25.2 | 0 | 0 |

| 11 | 6 | 18 | 65.67 | -43.44 | -65.44 | -91.23 | 0.238 | 2.16 |

| 12 | 17 | 19 | -265.57 | -20.68 | 266.22 | 1.2 | 0.651 | 5.93 |

| 13 | 17 | 21 | -87.11 | -3.61 | 87.16 | -12.47 | 0.046 | 0.42 |

| 14 | 17 | 8 | -72.92 | -93.42 | 73.22 | -43.24 | 0.297 | 2.7 |

| 15 | 16 | 20 | 87.13 | 55 | -87.04 | -77.06 | 0.095 | 0.87 |

| 16 | 16 | 20 | 87.13 | 55 | -87.04 | -77.06 | 0.095 | 0.87 |

| 17 | 16 | 21 | 137.57 | 146.94 | -137.16 | -169.53 | 0.409 | 3.72 |

| 18 | 16 | 1 | -131.66 | -196.05 | 132.24 | 167.09 | 0.581 | 4.84 |

| 19 | 16 | 9 | -186.35 | 4.86 | 186.72 | -31.55 | 0.37 | 3.08 |

| 20 | 16 | 26 | 6.18 | -65.74 | -6.17 | -20.74 | 0.016 | 0.15 |

| 21 | 18 | 19 | -708.65 | -1.8 | 710.09 | 6.94 | 1.44 | 13.01 |

| 22 | 18 | 20 | -158.98 | -200.96 | 159.25 | 191.52 | 0.269 | 2.47 |

| 23 | 18 | 22 | 84.06 | -1.02 | -84 | -22 | 0.062 | 0.56 |

| 24 | 19 | 7 | -694.66 | -78.57 | 695.38 | 81.04 | 0.721 | 6.63 |

| 25 | 19 | 7 | -694.66 | -78.57 | 695.38 | 81.04 | 0.721 | 6.63 |

| 26 | 20 | 10 | -112.17 | -93.39 | 112.56 | 28.56 | 0.381 | 3.47 |

| 27 | 23 | 10 | -238.22 | -46.18 | 239.17 | 5.66 | 0.95 | 8.64 |

| 28 | 23 | 12 | -91.85 | -43.94 | 92.21 | -74.11 | 0.361 | 3.28 |

| 29 | 23 | 27 | 70.06 | -17.89 | -69.73 | -110.64 | 0.337 | 3.07 |

| 30 | 8 | 24 | 109.34 | -33.98 | -109 | -40 | 0.336 | 2.75 |

| 31 | 1 | 9 | -373.62 | 1950.02 | 378.19 | -1915.35 | 4.572 | 38.15 |

| 32 | 1 | 25 | 97.39 | 87.15 | -97.24 | -108.65 | 0.144 | 1.2 |

| 33 | 1 | 25 | 97.39 | 87.15 | -97.24 | -108.65 | 0.144 | 1.2 |

| 34 | 25 | 11 | -157.98 | 36.08 | 158.21 | -58.33 | 0.23 | 1.89 |

| 35 | 25 | 26 | 44.47 | -3.79 | -44.41 | -60.08 | 0.061 | 0.51 |

| 36 | 11 | 26 | 108.65 | -18.68 | -108.39 | -40 | 0.255 | 2.09 |

| 37 | 26 | 12 | -54.03 | -31.19 | 54.16 | -75.69 | 0.126 | 1.14 |

| 38 | 12 | 14 | 2.77 | -36.31 | -2.75 | -85.34 | 0.027 | 0.25 |

| 39 | 27 | 13 | -241.27 | -50.36 | 242.97 | -13.02 | 1.699 | 15.47 |

References

- U. Khan, N. Javaid, K. A. A. Gamage, C. James Taylor, S. Baig, and X. Ma, “Heuristic Algorithm Based Optimal Power Flow Model Incorporating Stochastic Renewable Energy Sources,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 148622–148643, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Nadimi-Shahraki, S. Taghian, S. Mirjalili, L. Abualigah, M. A. Elaziz, and D. Oliva, “Ewoa-opf: Effective whale optimization algorithm to solve optimal power flow problem,” Electronics (Switzerland), vol. 10, no. 23, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, F. Jurado, S. Naetiladdanon, A. Sangswang, S. Kamel, and M. Ebeed, “Stochastic optimal power flow analysis of power system with renewable energy sources using Adaptive Lightning Attachment Procedure Optimizer,” International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, vol. 153, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, “Optimal Power Flow Considering Solar and Wind Energy Systems Via Modified Cuckoo Optimization Algorithm,” Journal of the North for Basic and Applied Sciences, no. 8, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Alghamdi, “Optimal Power Flow of Renewable-Integrated Power Systems Using a Gaussian Bare-Bones Levy-Flight Firefly Algorithm,” Front Energy Res, vol. 10, May 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. H. B. Huy, D. Kim, and D. N. Vo, “Multiobjective Optimal Power Flow Using Multiobjective Search Group Algorithm,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 77837–77856, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Gupta, N. Kumar, L. Srivastava, H. Malik, A. Anvari-moghaddam, and F. P. García Márquez, “A robust optimization approach for optimal power flow solutions using rao algorithms,” Energies (Basel), vol. 14, no. 17, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Chandrasekaran, “Multiobjective optimal power flow using interior search algorithm: A case study on a real-time electrical network,” Comput Intell, vol. 36, no. 3, pp. 1078–1096, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Daqaq, M. Ouassaid, and R. Ellaia, “A new meta-heuristic programming for multi-objective optimal power flow,” Electrical Engineering, vol. 103, no. 2, pp. 1217–1237, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Naderi, M. Pourakbari-Kasmaei, F. V. Cerna, and M. Lehtonen, “A novel hybrid self-adaptive heuristic algorithm to handle single- and multi-objective optimal power flow problems,” International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, vol. 125, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Khalid, H. M. Hamza, S. Mirjalili, and K. M. Hosny, “MOCOVIDOA: a novel multi-objective coronavirus disease optimization algorithm for solving multi-objective optimization problems,” Neural Comput Appl, vol. 35, no. 23, pp. 17319–17347, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Khalid, K. M. Hosny, and S. Mirjalili, “COVIDOA: a novel evolutionary optimization algorithm based on coronavirus disease replication lifecycle,” Neural Comput Appl, vol. 34, no. 24, pp. 22465–22492, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Gallego, J. F. Franco, and L. G. Cordero, “A fast-specialized point estimate method for the probabilistic optimal power flow in distribution systems with renewable distributed generation,” International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, vol. 131, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- F. Zishan, E. Akbari, and O. D. Montoya, “Analysis of probabilistic optimal power flow in the power system with the presence of microgrid correlation coefficients,” Cogent Eng, vol. 11, no. 1, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, P. Das, and A. K. Chakraborty, “A novel approach towards uncertainty modeling in multiobjective optimal power flow with renewable integration,” International Transactions on Electrical Energy Systems, vol. 29, no. 12, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Ali, G. Abbas, M. U. Keerio, M. A. Koondhar, K. Chandni, and S. Mirsaeidi, “Solution of constrained mixed-integer multi-objective optimal power flow problem considering the hybrid multi-objective evolutionary algorithm,” IET Generation, Transmission and Distribution, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 66–90, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Aien, M. Fotuhi-Firuzabad, and M. Rashidinejad, “Probabilistic optimal power flow in correlated hybrid wind-photovoltaic power systems,” IEEE Trans Smart Grid, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 130–138, Jan. 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Aien, R. Ramezani, and S. M. Ghavami, “Probabilistic Load Flow Considering Wind Generation Uncertainty,” 2011. [Online]. Available: www.etasr.com.

- M. Dadkhah and B. Venkatesh, “Cumulant based stochastic reactive power planning method for distribution systems with wind generators,” IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 2351–2359, 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. Aurangzeb, S. Shafiq, M. Alhussein, Pamir, N. Javaid, and M. Imran, “An effective solution to the optimal power flow problem using meta-heuristic algorithms,” Front Energy Res, vol. 11, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Sarhan, R. El-Sehiemy, A. Abaza, and M. Gafar, “Turbulent Flow of Water-Based Optimization for Solving Multi-Objective Technical and Economic Aspects of Optimal Power Flow Problems,” Mathematics, vol. 10, no. 12, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Al-Kaabi, V. Dumbrava, and M. Eremia, “A Slime Mould Algorithm Programming for Solving Single and Multi-Objective Optimal Power Flow Problems with Pareto Front Approach: A Case Study of the Iraqi Super Grid High Voltage,” Energies (Basel), vol. 15, no. 20, Oct. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Gupta, N. Kumar, L. Srivastava, H. Malik, A. Pliego Marugán, and F. P. García Márquez, “A hybrid jaya–powell’s pattern search algorithm for multi-objective optimal power flow incorporating distributed generation,” Energies (Basel), vol. 14, no. 10, May 2021. [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, M. Alanazi, Z. A. Memon, and A. Mosavi, “Determining Optimal Power Flow Solutions Using New Adaptive Gaussian TLBO Method,” Applied Sciences (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 16, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhao, L. Li, J. Yu, and Z. Li, “An Improved Marine Predators Algorithm for Optimal Reactive Power Dispatch With Load and Wind-Solar Power Uncertainties,” IEEE Access, vol. 10, pp. 126664–126673, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Ebeed, A. Alhejji, S. Kamel, and F. Jurado, “Solving the optimal reactive power dispatch using marine predators algorithm considering the uncertainties in load and wind-solar generation systems,” Energies (Basel), vol. 13, no. 17, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Karthik, A. K. Parvathy, R. Arul, and K. Padmanathan, “Multi-objective optimal power flow using a new heuristic optimization algorithm with the incorporation of renewable energy sources,” International Journal of Energy and Environmental Engineering, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 641–678, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Ilyas, G. Abbas, T. Alquthami, M. Awais, and M. B. Rasheed, “Multi-Objective Optimal Power Flow with Integration of Renewable Energy Sources Using Fuzzy Membership Function,” IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 143185–143200, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Mohseni-Bonab, A. Rabiee, B. Mohammadi-Ivatloo, S. Jalilzadeh, and S. Nojavan, “A two-point estimate method for uncertainty modeling in multi-objective optimal reactive power dispatch problem,” International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, vol. 75, pp. 194–204, Feb. 2016. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Morales and J. Pérez-Ruiz, “Point estimate schemes to solve the probabilistic power flow,” IEEE Transactions on Power Systems, vol. 22, no. 4, pp. 1594–1601, 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. Peik-Herfeh, H. Seifi, and M. K. Sheikh-El-Eslami, “Decision making of a virtual power plant under uncertainties for bidding in a day-ahead market using point estimate method,” International Journal of Electrical Power and Energy Systems, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 88–98, Jan. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Figueroa, R. Kharel, M. Quiroz-Castellanos, and E. Mezura-Montes, “Variation Operators for Grouping Genetic Algorithms: A Review”. [CrossRef]

- G. Gad, “Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm and Its Applications: A Systematic Review,” Archives of Computational Methods in Engineering, vol. 29, no. 5, pp. 2531–2561, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Z. Islam et al., “A Harris Hawks optimization based singleand multi-objective optimal power flow considering environmental emission,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 13, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. AL-Kaabi, S. Q. Salih, A. I. B. Hussein, V. Dumbrava, and M. Eremia, “Optimal Power Flow Based on Grey Wolf Optimizer: Case Study Iraqi Super Grid High Voltage 400 kV,” in Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH, 2023, pp. 490–503. [CrossRef]

- L. Slimani and T. Bouktir, “Multi-objective optimal power flow considering the fuel cost, emission, voltage deviation and power losses using Multi-Objective Dragonfly algorithm,” 2017. [Online]. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/322939107.

- R. A. El Sehiemy, F. Selim, B. Bentouati, and M. A. Abido, “A novel multi-objective hybrid particle swarm and salp optimization algorithm for technical-economical-environmental operation in power systems,” Energy, vol. 193, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Ghasemi, S. Ghavidel, M. M. Ghanbarian, M. Gharibzadeh, and A. Azizi Vahed, “Multi-objective optimal power flow considering the cost, emission, voltage deviation and power losses using multi-objective modified imperialist competitive algorithm,” Energy, vol. 78, pp. 276–289, Dec. 2014. [CrossRef]

| Control variables | min | max | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case3 | Case 4 | Case 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pg1(MW) | 50 | 200 | 140.2514 | 134.5761 | 134.6114 | 139.9049 | 130.1052 |

| Pg2(MW) | 20 | 80 | 50.43805 | 53.1141 | 48.70912 | 50.29628 | 50.1031 |

| Pg5(MW) | 15 | 50 | 27.80691 | 27.8523 | 29.05698 | 29.48819 | 27.49195 |

| Pg8(MW) | 10 | 35 | 35.34707 | 35.1804 | 34.07451 | 32.31542 | 33.62404 |

| Pg11(MW) | 10 | 30 | 19.489 | 22.2084 | 23.20275 | 21.42332 | 23.39687 |

| Pg13(MW) | 12 | 40 | 20.96857 | 18.9320 | 18.29716 | 15.3875 | 19.33414 |

| Q10(MVAr) | 0 | 5 | 4.595368 | 1.9572 | 3.578709 | 2.451346 | 3.17631 |

| Q12(MVAr) | 0 | 5 | 2.055626 | 1.0990 | 2.804495 | 0.465449 | 2.40793 |

| Q15(MVAr) | 0 | 5 | 4.402551 | 4.4817 | 4.187433 | 3.135117 | 0.53022 |

| Q17(MVAr) | 0 | 5 | 1.931677 | 3.8037 | 4.575689 | 4.725294 | 2.14841 |

| Q20(MVAr) | 0 | 5 | 4.550504 | 4.9286 | 3.436736 | 4.482416 | 1.60314 |

| Q21(MVAr) | 0 | 5 | 2.947572 | 4.6435 | 4.675022 | 4.528572 | 2.18216 |

| Q23(MVAr) | 0 | 5 | 2.544655 | 2.3785 | 1.870116 | 2.815127 | 1.78985 |

| Q24(MVAr) | 0 | 5 | 4.82601 | 3.5773 | 4.627495 | 4.96885 | 2.93594 |

| Q29(MVAr) | 0 | 5 | 4.300718 | 4.1293 | 2.424171 | 3.06705 | 1.08940 |

| Tr6-9 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.006707 | 1.044504 | 1.014857 | 1.016047 | 1.05741 |

| Tr6-10 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.021691 | 1.014578 | 1.051505 | 1.056226 | 1.01909 |

| Tr4-12 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.009127 | 1.00571 | 1.023904 | 1.029375 | 1.01495 |

| Tr27-28 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.990478 | 0.991432 | 1.003469 | 1.00641 | 1.01421 |

| VG1 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.030368 | 1.037668 | 1.057574 | 1.0558 | 1.09406 |

| VG2 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.016942 | 1.024458 | 1.046787 | 1.042571 | 1.08053 |

| VG3 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 0.99113 | 0.998129 | 1.019273 | 1.019921 | 1.05439 |

| VG4 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.007653 | 1.012465 | 1.035755 | 1.030266 | 1.0591 |

| VG5 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 0.99996 | 1.014189 | 0.970747 | 0.973151 | 1.01485 |

| VG6 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.030428 | 1.028067 | 1.023615 | 1.03548 | 1.01028 |

| cost ($/h) | ------ | ----- | 830.2781 | 825.9120 | 812.6197 | 810.12 | 799.959 |

| loss (MW) | ------ | ----- | 5.9010 | 6.0336 | 5.2519 | 5.415597 | 5.65531 |

| VD p.u | ------ | ----- | 0.1606 | 0.1411 | 0.2441 | 0.2293 | 0.2322 |

| Emission(ton/h) | ------ | ----- | 0.2449 | 0.2405 | 0.2372 | 0.231231 | 0.2516 |

| Papers | Method | Fuel cost $/h | Loss power (MW) | Emissions ton/h | V.D p.u |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [4] | COA | 830.2933 | 5.7225 | 0.2558 | 0.3319 |

| [4] | MCOA | 830.2793 | 5.5876 | 0.2529 | 0.2971 |

| [21] | TFWO | 826.779 | 5.459 | 0.255 | 0.459 |

| [22] | SMA | 832.3665 | 6.4495 | 0.2675 | 0.2189 |

| [23] | J-PPS1 | 830.9938 | 5.612 | 0.2355 | 0.299 |

| [23] | J-PPS2 | 830.8672 | 5.6175 | 0.2357 | 0.2948 |

| [23] | J-PPS3 | 830.3088 | 5.6377 | 0.2363 | 0.949 |

| [23] | Jaya | 831.5493 | 5.578 | 0.23582 | 0.31147 |

| [24] | AGTLBO | 830.1559 | 5.5823 | 0.2529 | 0.2975 |

| [24] | TLBO | 831.3186 | 5.5847 | 0.2538 | 0.2982 |

| [34] | HHO | 906.52 | 4.21 | 0.297 | ----------- |

| [37] | PSO-SSO | 826.94 | 5.515 | 0.258 | 0.466 |

| Present paper | COVIDOA | 830.2781 | 5.9010 | 0.2449 | 0.1606 |

| proposal | ENHCOVIDOA | 825.9120 | 6.0336 | 0.2405 | 0.1411 |

| Paper | Method | Fuel cost ($/h) |

Power loss (MW) |

Emission (ton/h) | Voltage deviation p.u | Combined objective function ($/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [23] | DA | 811.9476 | 5.2318 | 0.2328 | 0.3385 | 938.5816 |

| [23] | GWO | 811.2105 | 5.2836 | 0.2340 | 0.3142 | 938.4980 |

| [23] | Jaya | 812.3347 | 5.2871 | 0.2327 | 0.2525 | 938.3787 |

| [23] | J-PPS1 | 811.9609 | 5.2381 | 0.2329 | 0.2875 | 937.6646 |

| [23] | J-PPS2 | 811.8993 | 5.2171 | 0.2330 | 0.2990 | 937.3837 |

| [23] | J-PPS3 | 811.8635 | 5.2214 | 0.2329 | 0.2946 | 937.3486 |

| [34] | HHO | 905.19 | 4.02 | 0.219 | ---------- | ------------- |

| Present paper | COVIDOA | 812.6197 | 5.2519 | 0.2372 | 0.2441 | 925.0389 |

| Proposal | HENCOVIDOA | 810.12 | 5.41559 | 0.231231 | 0.2293 | 922.4154 |

| objectives | Mean value of objectives in case (4) | Mean value of objectives in case (5) |

Standard deviation value of objectives | Percentage error of objectives % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost $/h | 810.12 | 799.9597 | 26.1802 | 1.2540 |

| Power loss (MW) | 5.415597 | 5.655313 | 0.2207 | 4.238 |

| Emission ton/h | 0.23123 | 0.23169 | 0.00551 | 0.1989 |

| V.D p.u | 0.2293 | 0.2322 | 0.08106 | 0.22 |

| Control variables | Min | Max | Case 6 | Case 7 | Case 8 | Case 9 | Case 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PG1(MW) | 0.0 | 576 | 147.7466 | 147.3466 | 138.2847 | 139.4484 | 126.3896 |

| PG2(MW) | 30 | 100 | 76.90452 | 76.90452 | 55.91601 | 64.024 | 82.52883 |

| PG3(MW) | 40 | 140 | 44.96443 | 44.96443 | 47.05652 | 44.3149 | 43.49 |

| PG6(MW) | 30 | 100 | 82.88241 | 82.28241 | 66.60258 | 56.42907 | 77.60407 |

| PG8(MW) | 100 | 550 | 440.0902 | 440.0902 | 396.2878 | 414.49 | 416.4948 |

| PG9(MW) | 30 | 100 | 91.28159 | 91.18159 | 85.92483 | 76.05979 | 62.79682 |

| PG12(MW) | 100 | 410 | 382.655 | 382.155 | 378.8193 | 374.7441 | 359.8531 |

| VG1 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.05486 | 1.05486 | 0.999617 | 0.999848 | 1.014681 |

| VG2 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.057506 | 1.057506 | 1.002474 | 1.003335 | 1.024809 |

| VG3 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.047676 | 1.047676 | 0.997826 | 1.001074 | 1.021833 |

| VG6 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.054179 | 1.054179 | 1.006701 | 1.013864 | 1.027252 |

| VG8 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.055289 | 1.055289 | 1.029734 | 1.03665 | 1.055995 |

| VG9 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.050137 | 1.050137 | 1.017335 | 1.019945 | 1.047834 |

| VG12 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.040447 | 1.040447 | 0.999728 | 1.001865 | 1.027677 |

| T4-18 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.083404 | 1.083404 | 1.002931 | 0.992828 | 0.967174 |

| T4-18 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.078778 | 1.078778 | 1.038215 | 1.080058 | 0.952725 |

| T21-20 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.992588 | 0.992588 | 1.03737 | 1.061319 | 0.947047 |

| T24-25 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.024639 | 1.024639 | 1.028365 | 1.081288 | 0.918847 |

| T24-25 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.996758 | 0.996758 | 1.042208 | 1.089272 | 0.99157 |

| T24-26 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.033145 | 1.033145 | 1.092891 | 1.095885 | 0.985932 |

| T7-29 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.992827 | 0.992827 | 0.990088 | 0.992962 | 1.019252 |

| T34-32 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.083837 | 1.083837 | 1.001526 | 1.031651 | 0.919699 |

| T11-41 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.067665 | 1.067665 | 1.023986 | 1.022516 | 0.994203 |

| T15-45 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.004601 | 1.004601 | 1.092798 | 0.99325 | 0.994758 |

| T14-46 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.020462 | 1.020462 | 1.026692 | 1.007397 | 0.953022 |

| T10-51 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.995079 | 0.995079 | 1.027912 | 1.038841 | 0.987867 |

| T13-49 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.018602 | 1.018602 | 1.07377 | 1.072386 | 0.904351 |

| T11-43 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.08058 | 1.08058 | 1.038348 | 1.095747 | 0.941726 |

| T40-56 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.02203 | 1.02203 | 1.066259 | 1.085865 | 0.969629 |

| T39-57 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.085325 | 1.085325 | 1.045029 | 1.019932 | 1.016022 |

| T9-55 p.u | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.094524 | 1.094524 | 1.003751 | 1.006241 | 0.965147 |

| Qc18 (MVAr) | 0.0 | 20 | 7.853548 | 7.853548 | 10.80543 | 9.883294 | 15.63243 |

| Qc25 (MVAr) | 0.0 | 20 | 7.137135 | 7.137135 | 16.33461 | 13.77547 | 5.431922 |

| Qc53 (MVAr) | 0.0 | 20 | 16.18947 | 16.18947 | 15.58332 | 8.537731 | 10.88658 |

| Fuel cost ($/h) | --------- | --------- | 41789.3378 | 41720.67 | 37852.000 | 37799.000 | 37753.7149 |

| power loss(MW) | --------- | --------- | 14.1550 | 14.1249 | 13.2619 | 13.8806 | 13.5276 |

| Emission(ton/h) | --------- | --------- | 1.32605 | 1.3252 | 1.1997 | 1.1965 | 1.1551 |

| V.D p.u | -------- | -------- | 1.4101 | 1.396422 | 0.7894 | 0.7754 | 0.83219 |

| Papers | Method | Fuel cost $/h |

Power loss (MW) | Emission (ton/h) | VD p.u |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [23] | DA | 42,584.46 | 13.6065 | 1.3577 | 0.8124 |

| [23] | GWO | 42,587.97 | 13.2727 | 1.3447 | 0.7921 |

| [23] | Jaya | 42,547.09 | 12.772 | 1.3708 | 0.8202 |

| [23] | J-PPS1 | 42,575.97 | 12.5408 | 1.3336 | 0.7893 |

| [23] | J-PPS2 | 42,580.09 | 12.5242 | 1.3433 | 0.7251 |

| [23] | J-PPS3 | 42,564.46 | 12.5079 | 1.3566 | 0.7365 |

| [24] | TLBO | 41,932.01 | 11.5285 | 1.4357 | 0.9528 |

| [24] | AGTLBO | 41,929.39 | 13.2563 | 1.4328 | 0.9526 |

| [36] | MODA | 43897 | 16.7039 | 1.6312 | 0.004 |

| [38] | MOICA | 41,998.57 | 13.3353 | 1.7605 | 0.8748 |

| [38] | MOMICA | 41983.06 | 13.6969 | 1.496 | 0.797 |

| Present paper | COVIDOA | 41789.3378 | 14.1550 | 1.32605 | 1.4101 |

| proposal | ENHCOVIDOA | 41720.67 | 14.1249 | 1.3252 | 1.396422 |

| Papers | Method | Fuel cost ($/h) | Power loss (MW) | Emission (ton/h) | Voltage deviation p.u | Combined objective function ($/h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [23] | DA | 38,120.833 | 12.3189 | 1.2751 | 0.5454 | 39,200.17 |

| [23] | GWO | 38,114.735 | 13.1703 | 1.3099 | 0.4504 | 39,173.097 |

| [23] | Jaya | 38,105.956 | 12.5706 | 1.3218 | 0.4721 | 39,162.889 |

| [23] | J-PPS1 | 38,059.913 | 12.8818 | 1.3035 | 0.5469 | 39,167.596 |

| [23] | J-PPS2 | 38,048.250 | 13.3724 | 1.3612 | 0.5136 | 39,165.964 |

| [23] | J-PPS3 | 38,033.832 | 12.9742 | 1.3115 | 0.5329 | 39,136.324 |

| Present paper | COVIDOA | 37852.000 | 13.2619 | 1.1997 | 0.7894 | 38748.123 |

| proposal | ENHCOVIDOA | 37,799.000 | 13.8806 | 1.1965 | 0.7754 | 38,733.676 |

| objectives | Mean value of objectives in case (9) |

Mean value of objectives in case (10) |

Standard deviation value of objectives |

Percentage error of mean (9) & mean (10) % |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost $/h | 37799.000 | 37753.7149 | 1175.8062 | 0.1198 | |

| Power loss (MW) | 13.8806 | 13.5276 | 1.2534 | 2.54311 | |

| Emission ton/h | 1.1965 | 1.1551 | 0.0668 | 3.4600 | |

| V.D p.u | 0.7754 | 0.83219 | 0.06986 | 7.3239 |

| Control variables | Min | Max | Case 11 | Case 12 | Case 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pg1(MW) | 150 | 1200 | 699.9615 | 618.2087 | 719.1426 |

| Pg2(MW) | 130 | 988 | 492.2544 | 485.9416 | 489.1143 |

| Pg3(MW) | 150 | 750 | 214.1131 | 220.9904 | 215.9316 |

| Pg4(MW) | 120 | 1320 | 187.6118 | 157.4339 | 143.732 |

| Pg5(MW) | 70 | 636 | 86.83202 | 99.40292 | 103.8542 |

| Pg6(MW) | 50 | 260 | 218.9916 | 216.6991 | 225.7888 |

| Pg7(MW) | 180 | 910 | 900.778 | 905.4464 | 871.8454 |

| Pg8(MW) | 60 | 660 | 423.9247 | 402.1977 | 407.9387 |

| Pg9(MW) | 50 | 500 | 364.8132 | 82.70119 | 75.19729 |

| Pg10(MW) | 250 | 1320 | 354.707 | 295.1099 | 296.9072 |

| Pg11(MW) | 250 | 1250 | 403.361 | 731.3575 | 708.5445 |

| Pg12(MW) | 210 | 800 | 622.2266 | 577.7357 | 543.7552 |

| Pg13(MW) | 100 | 940 | 857.7883 | 742.7903 | 731.771 |

| Pg14(MW) | 50 | 250 | 185.3944 | 176.0874 | 170.8831 |

| VG1 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.031671 | 0.971935 | 0.980602 |

| VG2 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.059468 | 1.058471 | 1.058493 |

| VG3 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 0.943989 | 0.942145 | 0.941001 |

| VG4 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 0.996006 | 1.037361 | 0.946481 |

| VG5 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 0.999072 | 1.040843 | 0.947657 |

| VG6 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.021664 | 1.055141 | 0.941425 |

| VG7 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.056341 | 1.059461 | 1.000028 |

| VG8 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.054181 | 1.05847 | 1.058423 |

| VG9 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 0.941005 | 1.059939 | 1.034749 |

| VG10p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.056691 | 1.052316 | 1.03147 |

| VG11 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.054986 | 1.053859 | 1.032116 |

| VG12 p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.059054 | 1.055919 | 1.052243 |

| VG13p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 1.049867 | 1.047947 | 1.043022 |

| VG14p.u | 0.94 | 1.06 | 0.966548 | 0.961948 | 0.958046 |

| Fuel cost ($/h) | ------ | ----- | 27166.96 | 24053.64 | 23762.34 |

| power loss (MW) | ------ | ------ | 31.37879 | 34.1026 | 32.10262 |

| Emission(ton/h) | ------ | ------ | 0.8038 | 0.7379 | 0.7332 |

| V.D p.u | ------ | ------ | 0.3305 | 0.658 | 0.5408 |

| Objectives | Mean value of objectives in case (12) | Mean value of objectives in case (13) | Standard deviation value of objectives | Percentage error of objectives case12 & case 13 % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cost $/h | 24053.64 | 23762.34 | 896.0824 | 1.2 | |

| Power loss (MW) | 34.1026 | 32.10262 | 7.6639 | 5.8645 | |

| Emission ton/h | 0.7379 | 0.7332 | 0.91397 | 0.6369 | |

| V.D p.u | 0.658 | 0.5408 | 0.01563 | 17.8115 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).