Submitted:

29 October 2024

Posted:

29 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

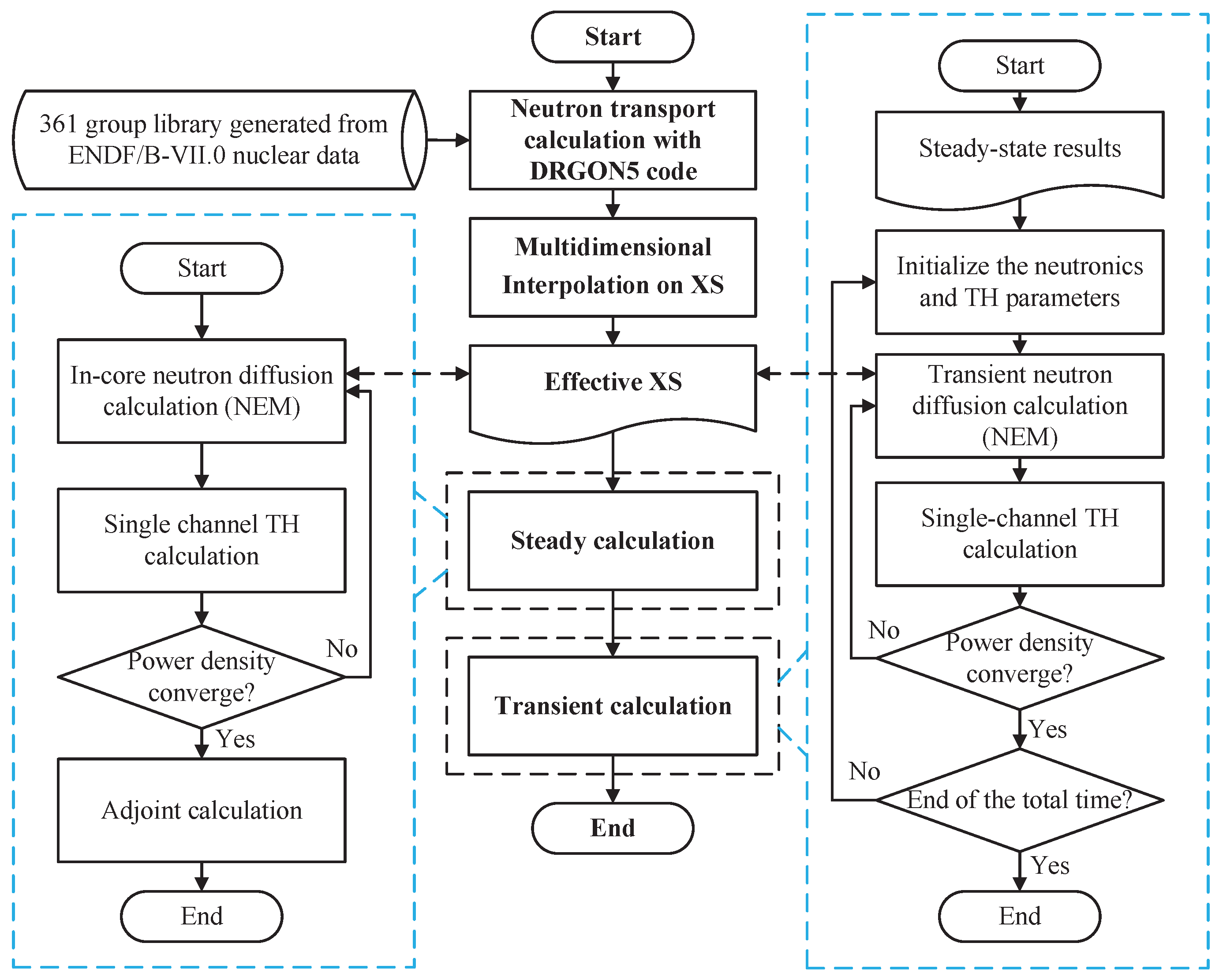

2. Numerical Model and Solution Method

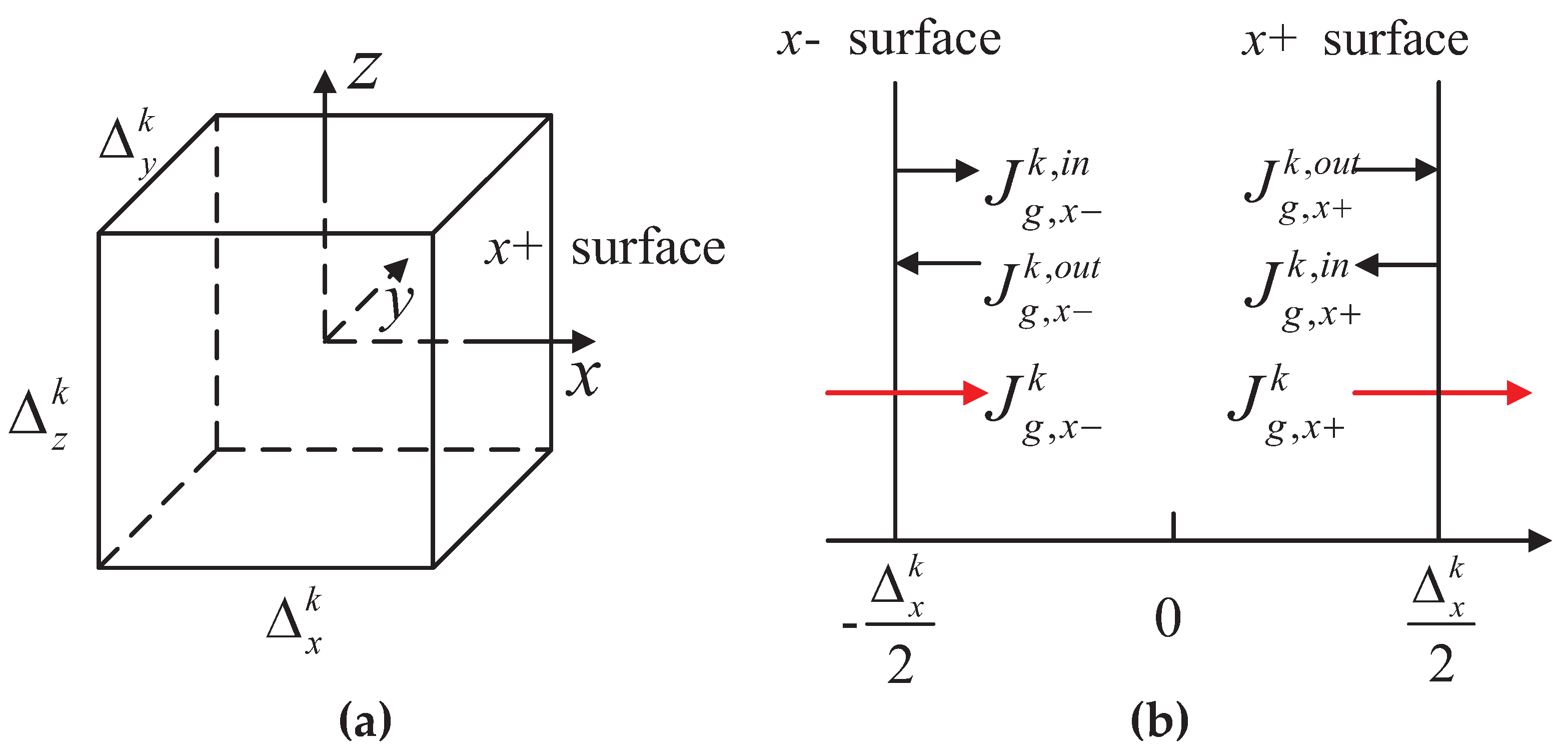

2.1. Brief Description of the Neutronics Model

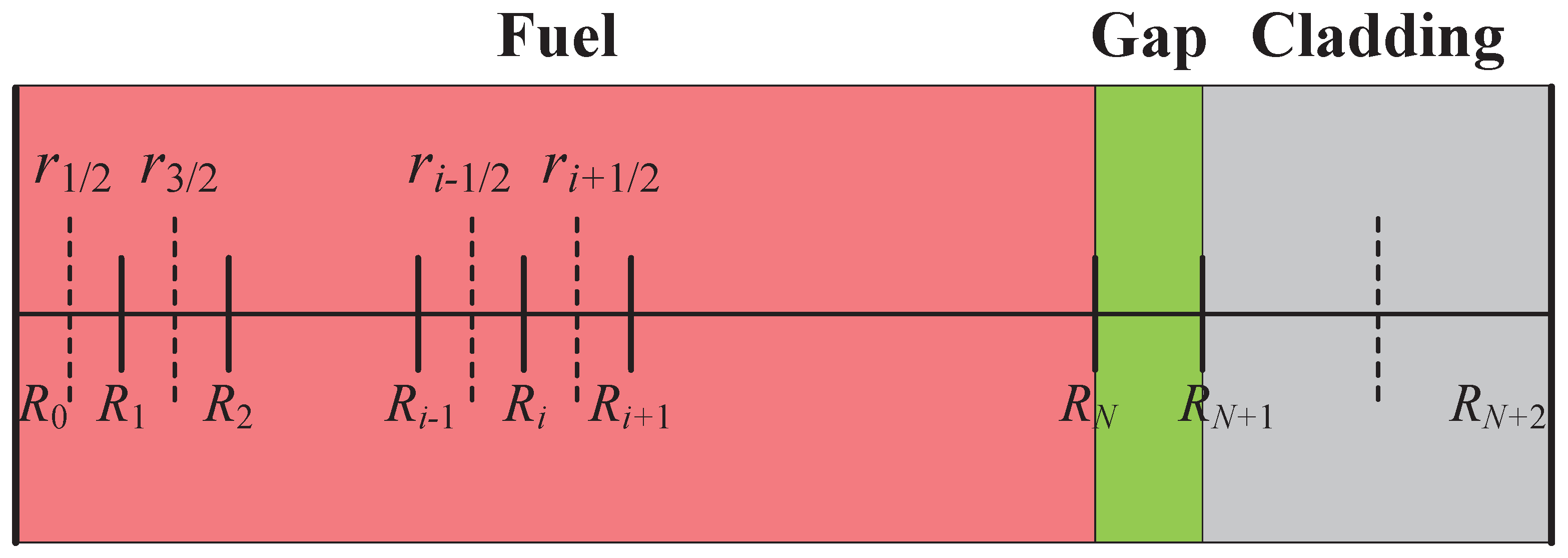

2.2. Single-Channel TH Model

2.3. Coupling Scheme

3. Results and Discussion

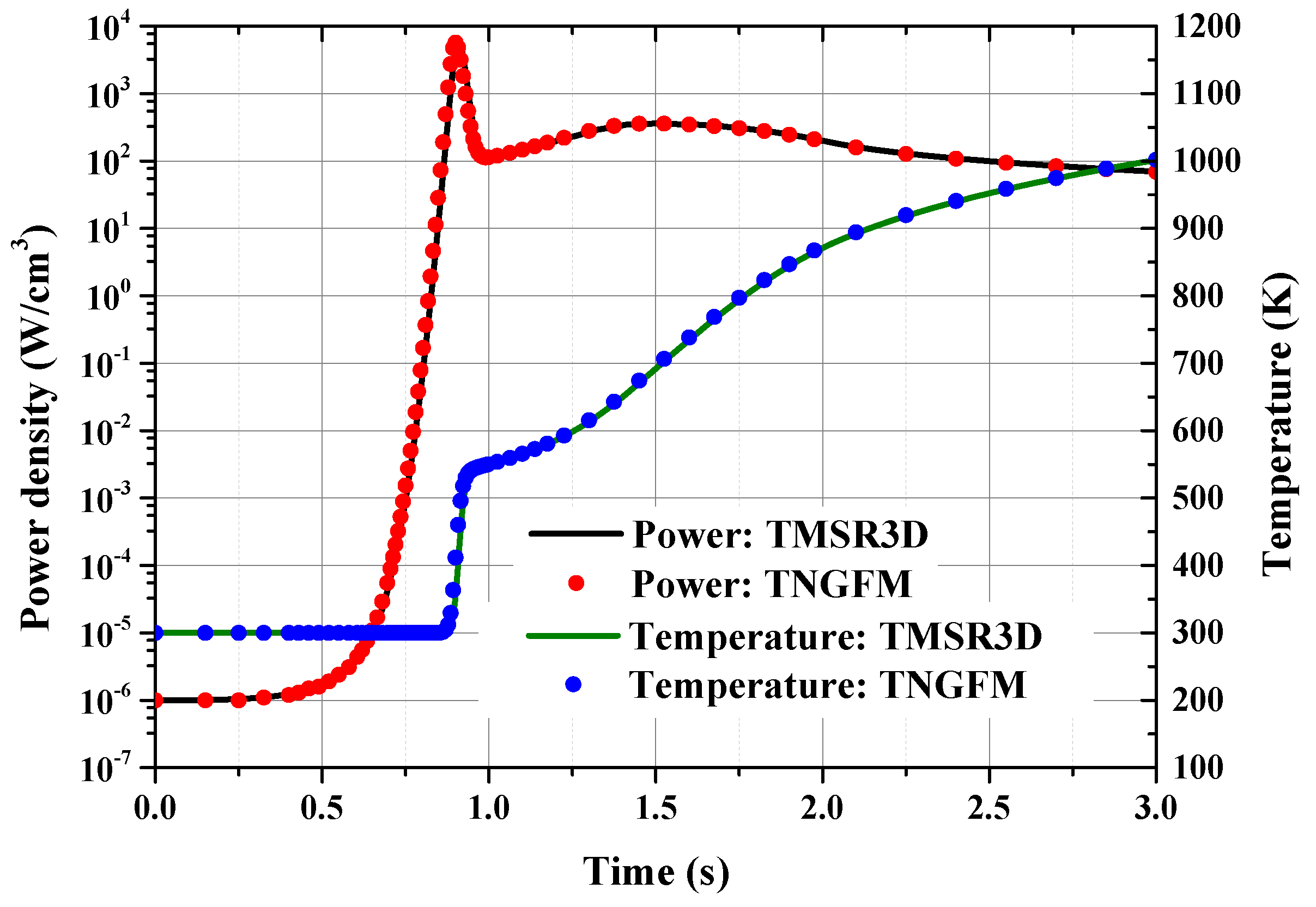

3.1. 3D-LRA Benchmark

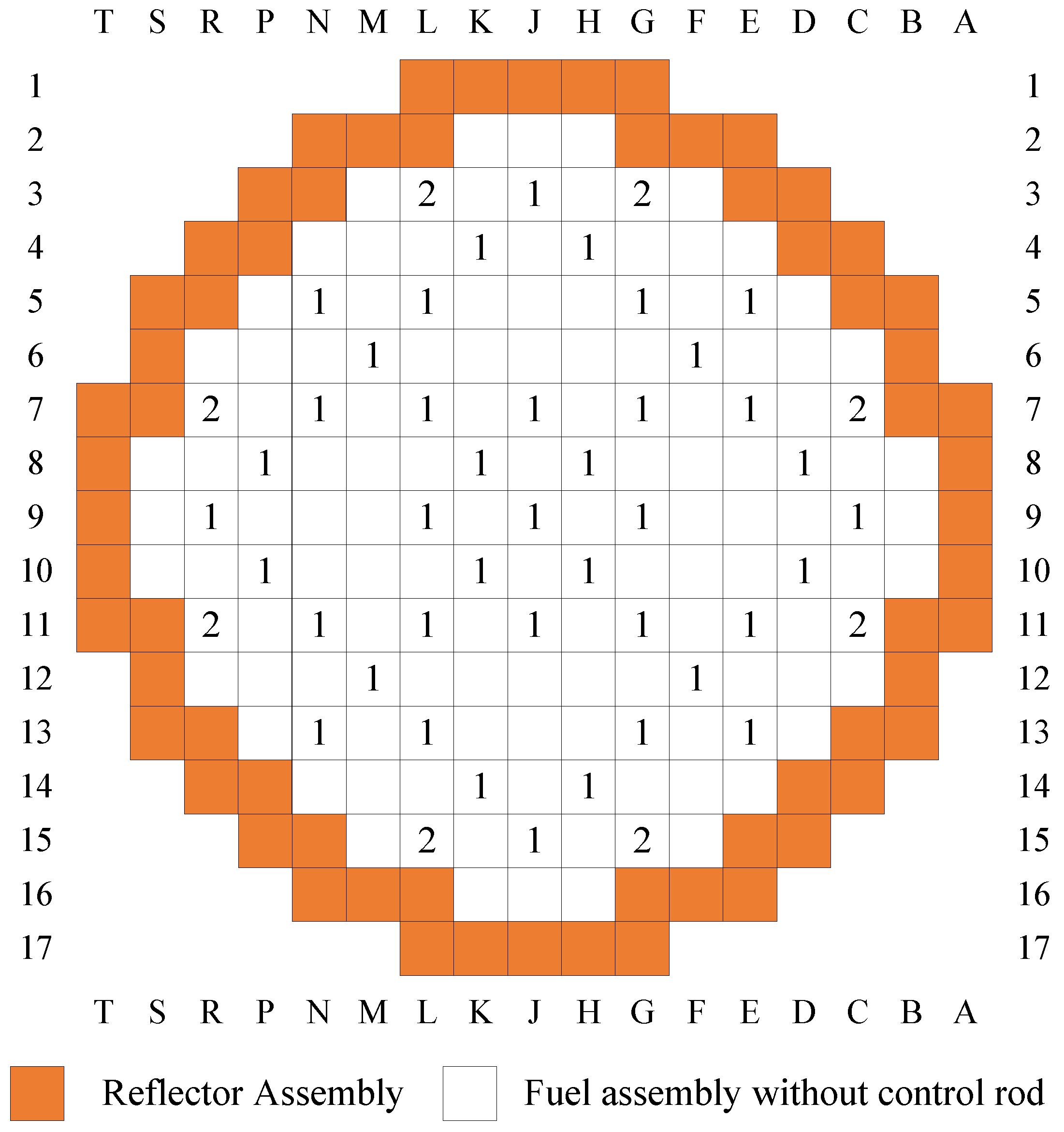

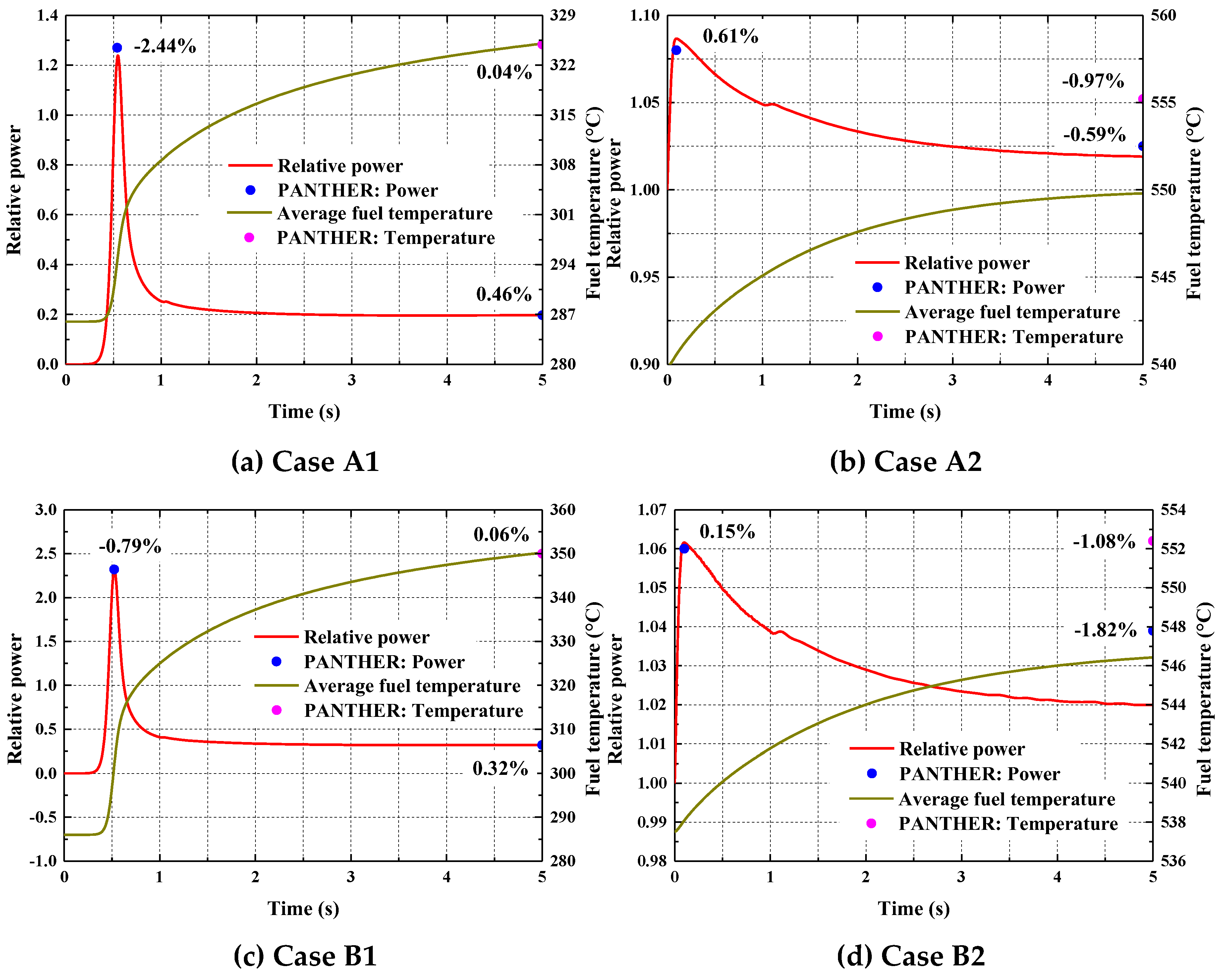

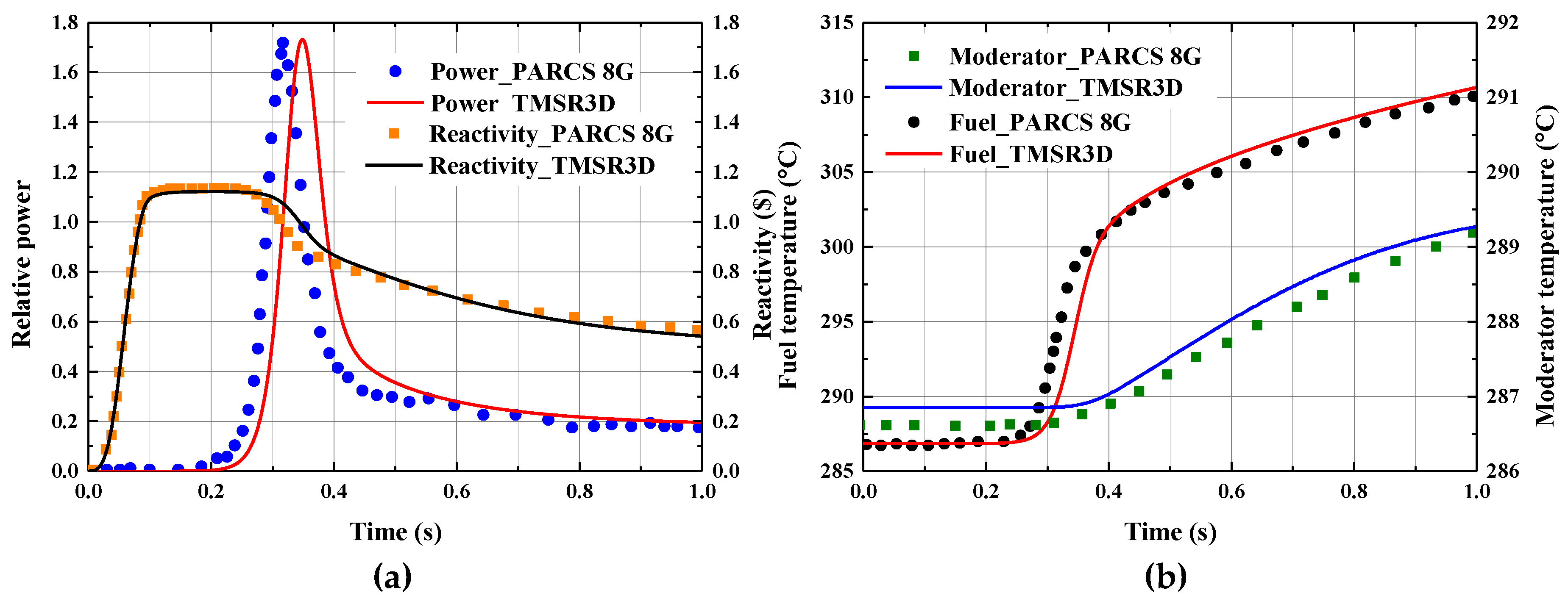

3.2. NEACRP 3D PWR Benchmark

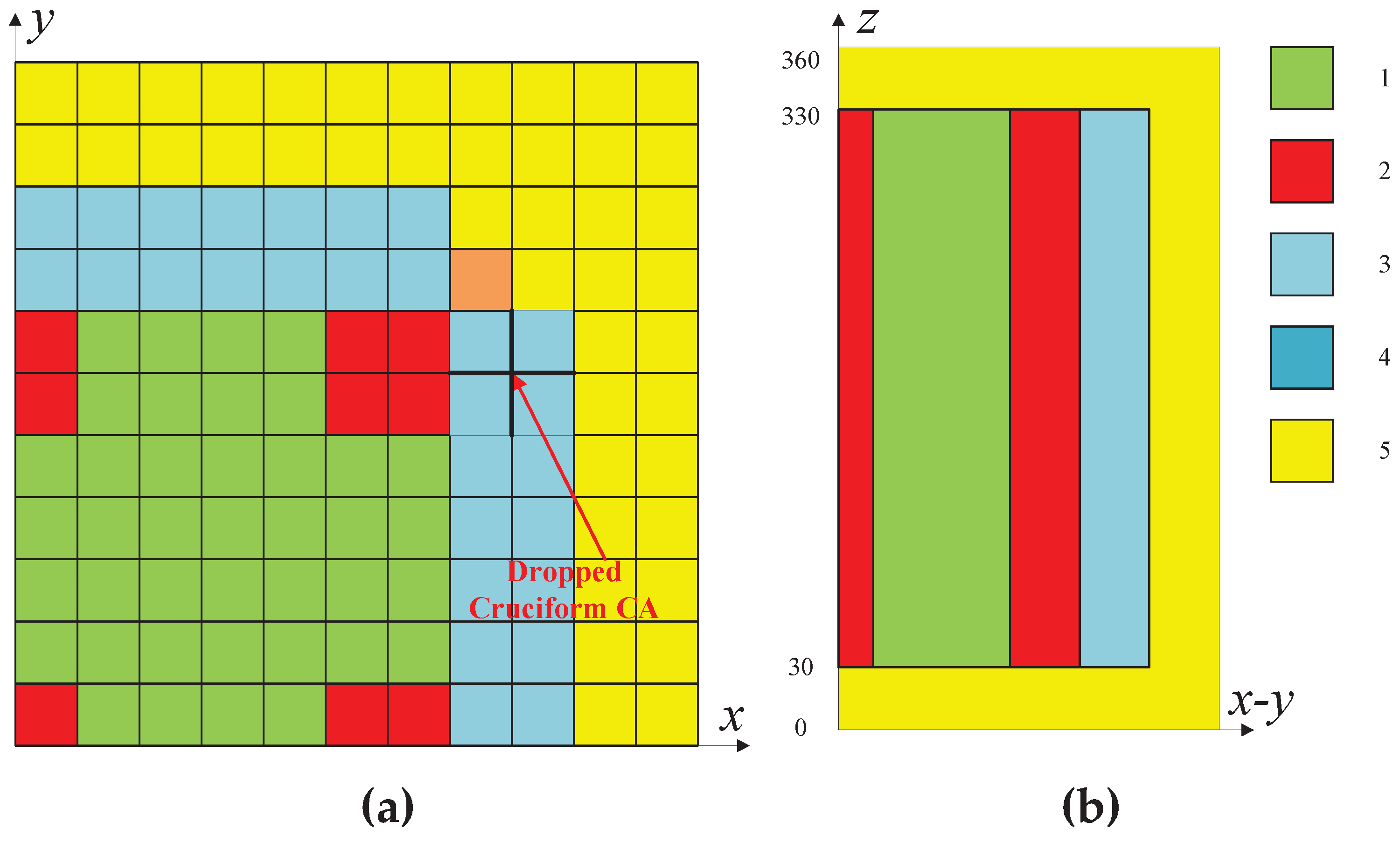

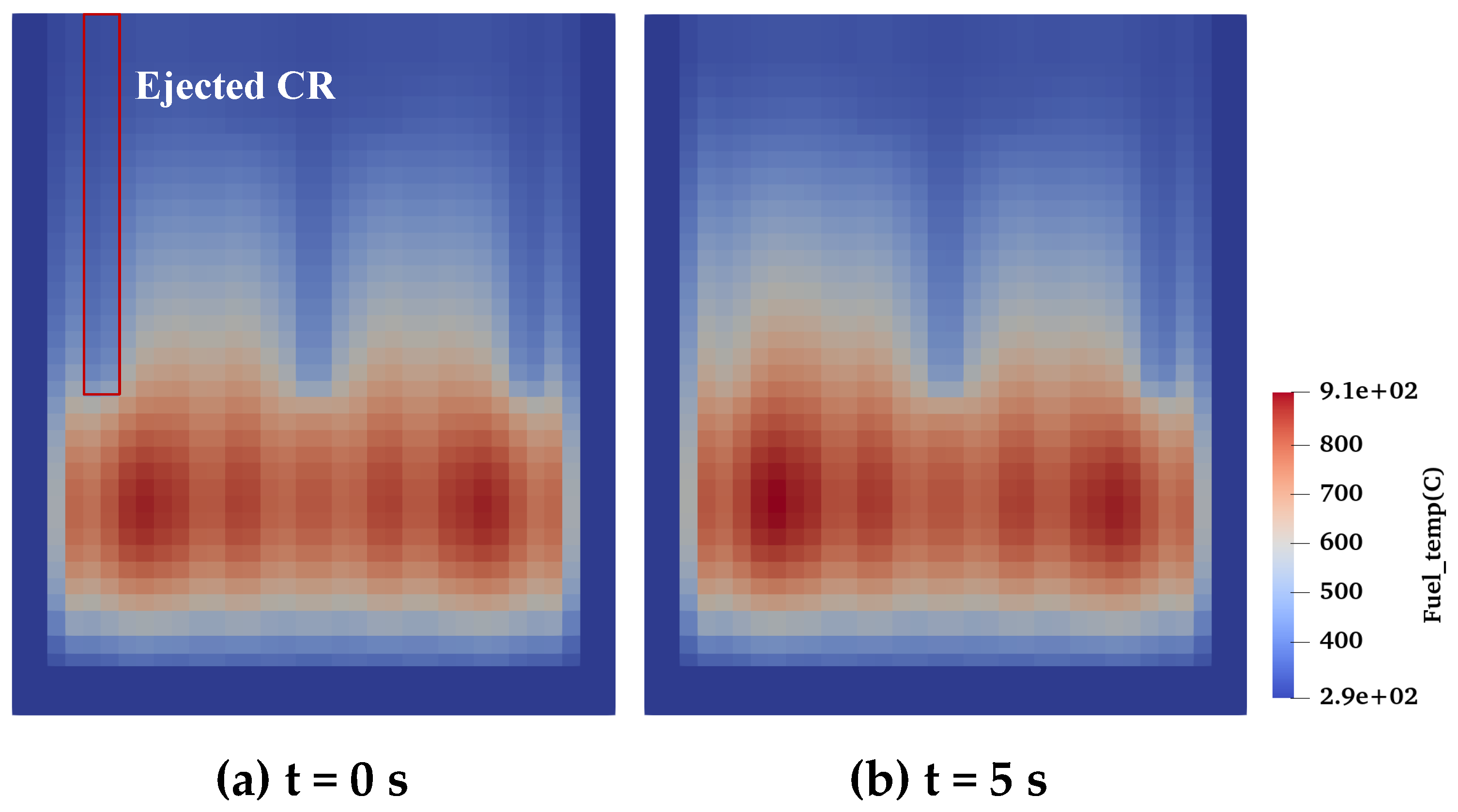

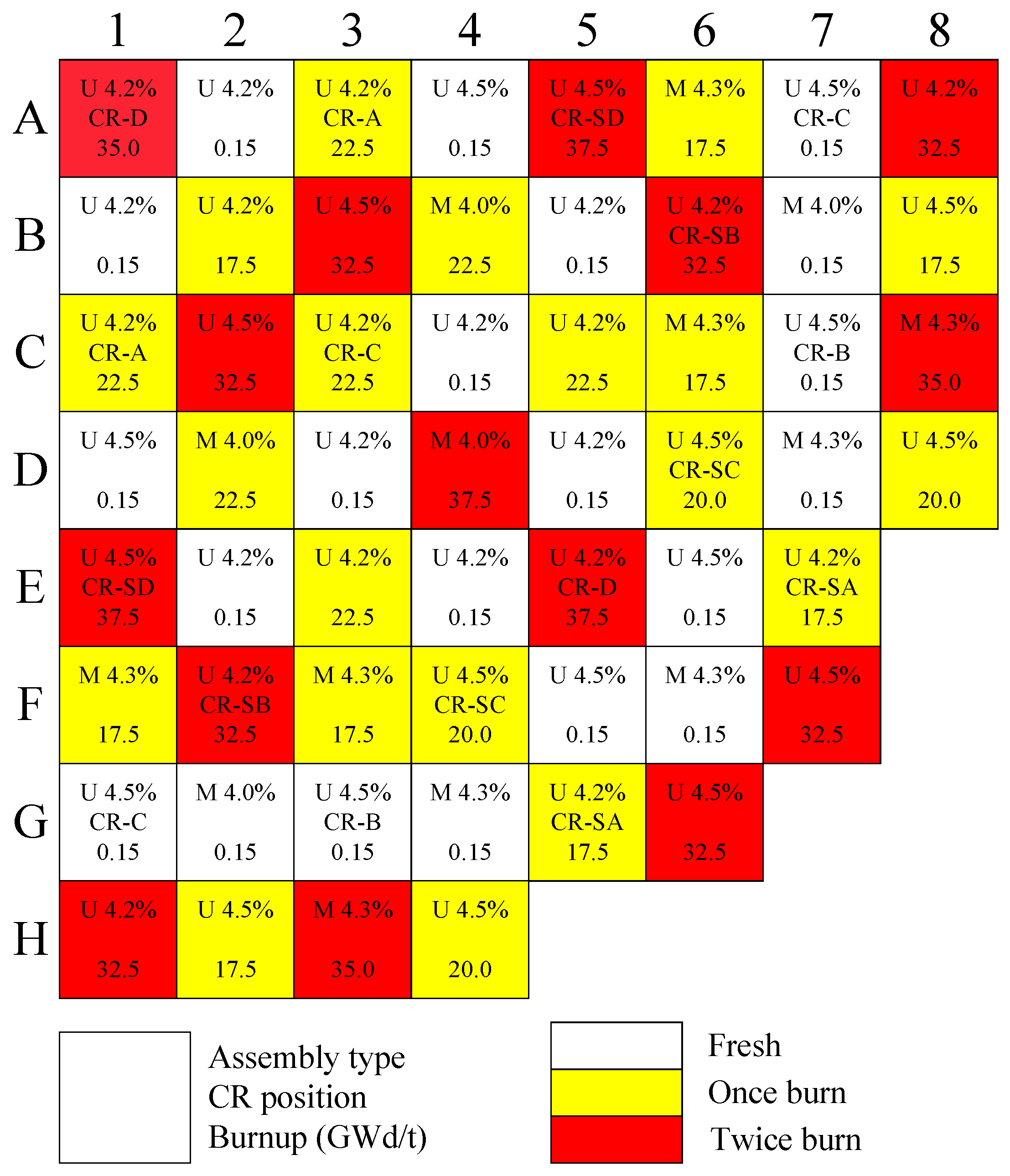

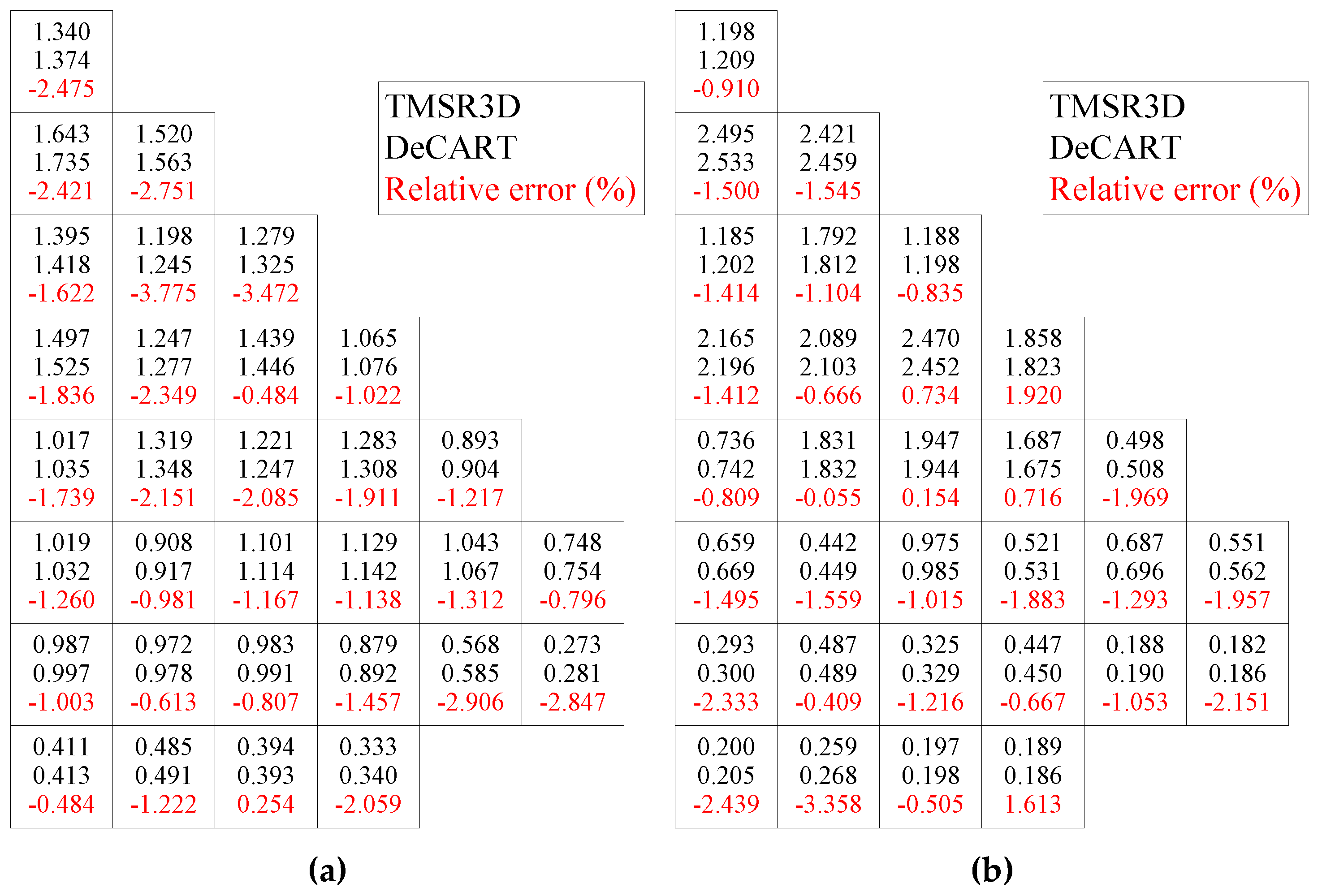

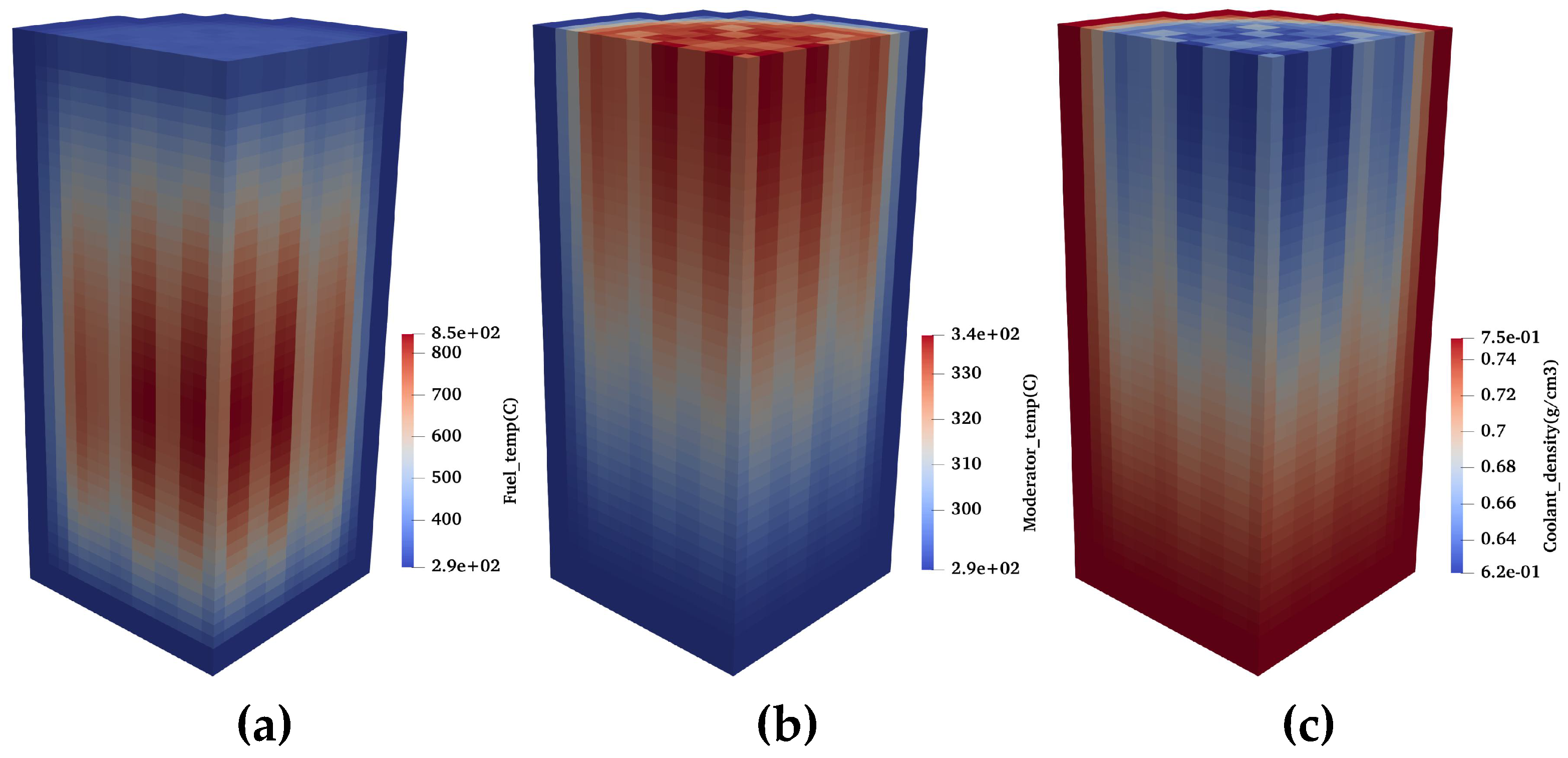

3.3. PWR MOX/UO2 Core Benchmark

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Turinsky, P.J.; Kothe, D.B. Modeling and simulation challenges pursued by the Consortium for Advanced Simulation of Light Water Reactors (CASL). J. Comput. Phys. 2016, 313, 367–376. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.N.; Chen, P.; Wu, Y.W.; Su, G.H.; Tian, W.X.; Qiu, S.Z. Preliminary evaluation of U3Si2-FeCrAl fuel performance in light water reactors through a multi-physics coupled way. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2018, 328, 27–35. [CrossRef]

- Short, M.P.; Hussey, D.; Kendrick, B.K.; Besmann, T.M.; Stanek, C.R.; Yip, S. Multiphysics modeling of porous CRUD deposits in nuclear reactors. J. Nucl. Mater. 2013, 443, 579–587. [CrossRef]

- Gaston, D.; Newman, C.; Hansen, G.; Lebrun-Grandié, D. MOOSE: A parallel computational framework for coupled systems of nonlinear equations. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2009, 239, 1768–1778. [CrossRef]

- Cammi, A.; Di Marcello, V.; Luzzi, L.; Memoli, V.; Ricotti, M.E. A multi-physics modelling approach to the dynamics of Molten Salt Reactors. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2011, 38, 1356–1372. [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Jaradat, M.K.; Yang, W.S.; Lee, C. Development of coupled PROTEUS-NODAL and SAM code system for multiphysics analysis of molten salt reactors. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2022, 168, 108889. [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Chen, J.G.; Wu, J.H.; Zou, C.Y.; Cui, L.; He, F.; Cai, X.Z. Development and verification of a three-dimensional spatial dynamics code for molten salt reactors. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2022, 171, 109040. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Chen, J.; Cao, L.Z.; Zhao, C.; He, Q.M.; Wu, H.C. Development and verification of the high-fidelity neutronics and thermal-hydraulic coupling code system NECP-X/SUBSC. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2018, 103, 114–125. [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.S.; Shim, C.B.; Lim, C.H.; Joo, H.G. Practical numerical reactor employing direct whole core neutron transport and subchannel thermal/hydraulic solvers. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2013, 62, 357–374. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.M.; Xie, H.Y.; Mao, W.C.; Ping, J.L. Nuclear-data uncertainty analysis for the start-up physics test of CPR1000 reactor. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2021, 156, 108197. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, S.; Hong, H.; Choi, N.; Joo, H.G. Methods and performance of a GPU-based pin wise two-step nodal code VANGARD. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2023, 156, 104528. [CrossRef]

- Hegyi, G.; Maráczy, C.; Temesvári, E. Simulation of xenon transients in the VVER-1200 NPP using the KARATE code system. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2022, 176, 109258. [CrossRef]

- Marleau, G.; Hébert, A.; Roy, R. A User Guide for DRAGON Version 5. Technical Report IGE–335, Institut de génie nucléaire, Département de génie mécanique, École Polytechnique de Montréal, 2019.

- Cui, Y.; Chen, J.G.; Dai, M.; Cai, X.Z. Development of A Steady State Analysis Code for Molten Salt Reactor based on Nodal Expansion Method. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2021, 151, 107950. [CrossRef]

- Pinem, S.; Sembiring, T.M.; Liem, P.H. NODAL3 sensitivity analysis for NEACRP 3D LWR core transient benchmark (PWR). Sci. Technol. Nucl. Ins. 2016, 2016, 7538681. [CrossRef]

- Biery, M.; Avramova, M. Investigations on coupled code PWR simulations using COBRA-TF with soluble boron tracking model. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2014, 77, 72–83. [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.K. Study on Numerical Solution for Three Dimensional Nodal Space-Time Neutron Kinetic Equations and Coupled Neutronic/Thermal-Hydraulic Core Transient Analysis (in Chinese). PhD thesis, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an, China, 2002.

- Imron, M. Development and verification of open reactor simulator ADPRES. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2019, 133, 580–588. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.D. Progress in nodal methods for the solution of the neutron diffusion and transport equations. Prog. Nucl. Energy 1986, 17, 271–301. [CrossRef]

- Hendricks, J. Finite difference solution of the time dependent neutron group diffusion equations. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Massachusetts, The U.S., 1975. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.S.; Cho, N.Z. Kinetics calculation under space-dependent feedback in analytic function expansion nodal method via solution decomposition and Galerkin scheme. Nucl. Sci. Eng. 2002, 140, 267–284. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, W.; Kretzschmar, H. International Steam Tables: Properties of Water and Steam Based on the Industrial Formulation. Technical Report IAPWSIF97, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2008.

- Hong, L.P.; Surian, P.; Malem, S.T.; Hoai, N.T. Status on development and verification of reactivity initiated accident analysis code for PWR (NODAL3). Nucl. Sci. Tech. 2016, 6, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Finnemann, H.; Galati, A. NEACRP 3-D LWR Core Transient Benchmark-Final Specifications. Technical Report NEACRP-L-335, OECD Nuclear Energy Agency, 1991.

- Ban, Y.; Endo, T.; Yamamoto, A. A unified approach for numerical calculation of space-dependent kinetic equation. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2012, 49, 496–515. [CrossRef]

- Institute of Nuclear and New Energy Technology. Verification report of the TNGFM code. Technical report, Tsinghua University, Beijing, 2009.

- Kinght, M.P.; Bryce, P. Derivation of a Refined PANTHER Solution to the NEACRP PWR Rod-Ejection Transient. In Proceedings of the Joint International Conference on Mathematical Method Applications, Saratoga, Springs, 1997; Vol. 1, pp. 302–313.

- Kozlowski, T.; Downar, T. PWR MOX/UO2 Core Transient Benchmark Final Report. Technical report, Purdue University, 2007.

- Han, G.J.; Jin, Y.C.; Ha, Y.K.; Sung, Q.Z.; Moon, H.C. Dynamic Implementation of the Equivalence Theory in the Heterogeneous Whole Core Transport Calculation. In Proceedings of the PHYSOR 2002, Seoul, Korea, 2002.

- Thomas, J.D.; Douglas, A.B.; Miller, R.M.; Deokjung, Chang, H.L.; Tomasz, K.; Deokjung, L.; Xu, Y.L.; Gan, J.; Cho, H.G.; Joo, J.Y.; et al. PARCS: Purdue Advanced Reactor Core Simulator. In Proceedings of the PHYSOR 2002, Seoul, Korea, 2002.

- Wu, J.H.; Guo, C.; Cai, X.Z.; Yu, C.G.; Zou, C.Y.; Han, J.L.; Chen, J.G. Flow effect on 135I and 135Xe evolution behavior in a molten salt reactor. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2017, 314, 318–325. [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Values | Parameters | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal power (MW) | 2775 | Clad wall thickness (mm) | 0.571 |

| Inlet temperature (°C) | 286 | Fuel rod pitch (mm) | 12.655 |

| Inlet mass flow rate (kg/s) | 12893 | Inner diameter of guide tube (mm) | 11.448 |

| Fraction of heat deposited in coolant (%) | 1.9 | Outer diameter of guide tube (mm) | 12.259 |

| Fuel pellet diameter (mm) | 8.239 | Fuel pin number/Assembly | 264 |

| Cladding outer diameter (mm) | 9.517 | Guide tube number/Assembly | 25 |

| Case | Ejected CR Number | Work Condition | Position of Ejected Rod (Steps) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | |||

| A1 | 1 (central) | HZP | 0 | 228 |

| A2 | 1 (central) | HFP | 100 | 228 |

| B1 | 4 (peripheral) | HZP | 0 | 228 |

| B2 | 4 (peripheral) | HFP | 150 | 228 |

| C1 | 1 (Full core) | HZP | 0 | 228 |

| C2 | 1 (Full core) | HFP | 100 | 228 |

| Cases | A1 | A2 | B1 | B2 | C1 | C2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reactor conditions | HZP | HFP | HZP | HFP | HZP | HFP |

| Critical Boron Concentration (ppm) | ||||||

| PANTHER | 561.20 | 1156.63 | 1247.98 | 1183.83 | 1128.29 | 1156.63 |

| TMSR3D | 560.53 | 1156.14 | 1247.38 | 1184.54 | 1127.69 | 1156.06 |

| Relative Error (%) | −0.119 | -0.042 | −0.048 | 0.060 | −0.053 | -0.049 |

| Maximal power peaking factor | ||||||

| PANTHER | 2.8792 | 2.2073 | 1.9330 | 2.0954 | 2.1867 | 2.2073 |

| TMSR3D | 2.8467 | 2.2171 | 1.8853 | 2.0688 | 2.1729 | 2.2690 |

| Relative Error (%) | −1.129 | 0.444 | -2.468 | −1.269 | −0.631 | 2.795 |

| Reactivity introduced by control rod ejection (pcm) | ||||||

| PANTHER | 824.31 | 91.58 | 826.18 | 99.45 | 949.09 | 79.23 |

| TMSR3D | 820.12 | 91.32 | 822.97 | 94.11 | 944.10 | 80.93 |

| Relative Error (%) | -0.508 | −0.284 | −0.389 | −5.370 | −0.526 | 2.146 |

| Parameters | Values | Parameters | Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core power (MWt) | 3565 | Core pressure (Mpa) | 15.5 |

| Inlet temperature (°C) | 286.85 | Guide tubes per assembly | 25 |

| Inlet mass flow rate (kg/s) | 15849.4 | Active fuel length (cm) | 365.76 |

| Fuel lattice, fuel rods per assembly | 17 ×17, 264 | Assembly pitch (cm) | 21.42 |

| Number of fuel assemblies | 193 | Pin pitch (cm) | 1.26 |

| Code | Total CR worth (pcm) | Error (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARI | ARO | |||

| DeCART | 0.987430 | 1.058520 | 6801 | / |

| PARCS 2G | 0.991536 | 1.063786 | 6850 | 0.710 |

| CITATION | 0.988785 | 1.060337 | 6825 | 0.339 |

| TMSR3D | 0.991535 | 1.063782 | 6849 | 0.706 |

| Code | Core Critical Boron Concent. (ppm) |

Core Average TH Properties | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fuel | Coolant | Coolant | Outlet Cool. | Outlet Cool. | ||

| Temp. | Density | Temp. | Density | Temp. | ||

| (°C) | (g/cm3) | (°C) | (g/cm3) | (°C) | ||

| PARCS 2G | 1679 | 562.9 | 0.7061 | 308.2 | 0.6621 | 325.7 |

| PARCS 4G | 1674 | 563.0 | 0.7061 | 308.2 | 0.6621 | 325.7 |

| PARCS 8G | 1672 | 563.1 | 0.7061 | 308.2 | 0.6621 | 325.7 |

| SKETCH | 1675 | 563.5 | 0.7055 | 307.8 | 0.6596 | 325.8 |

| TMSR3D | 1673 | 562.8 | 0.7057 | 308.1 | 0.6615 | 325.5 |

| Code | Peak Power (%) | Peak Time (s) | Peak Reactivity ($) | (pcm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PARCS 2G | 142 | 0.34 | 1.12 | 579 |

| PARCS 4G | 152 | 0.33 | 1.12 | 579 |

| PARCS 8G | 172 | 0.32 | 1.14 | 580 |

| SKETCH | 144 | 0.34 | 1.12 | 579 |

| TMSR3D | 173 | 0.35 | 1.12 | 580 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).