1. Introduction

Industrial production has become a self-evident prerequisite for the supply of new goods, necessary for the daily life of a person. The goods that reached the shelves of stores in the 20th century were made with the assumption of long-term use by their future owners. The consumer lifestyle, which began to be more massively enforced in developed economic countries from about the middle of the 20th century, also contributed to the trend of constant GDP growth. The industry began to produce products with a shorter shelf life, which on the one hand meant better affordability for the wider masses of people, but on the other hand it led to an extreme increase in waste. At the time, society was not burdened with the questions of what the secondary consequences of this trend would be. It was assumed that the company could continue to cope with technical waste. In the following decades, the problem of the growing amount of waste was localized as a problem of developing countries. Moreover, waste was almost exclusively associated with poor people or marginalized social groups. Similarly, like other aspects of environmental social work, the issue of waste and its impact on the life of society has remained unnoticed for a long time in Slovak social work.

Two facts can be identified as the cause of lack of interest:

- 1)

there were no such types of waste landfills in Slovakia as in India, Africa or Mexico,

- 2)

the inhabitants of Slovakia subsisted on waste products in a minimal amount, and moreover, this way of life was clearly not linked to any ethnic community, but to the homeless, among whom there have been also members of the majority. The fact that the amount of hazardous and toxic materials also increases with increasing waste [

1], puts pressure on the way it is processed, from landfilling to e.g. burning waste [

2], which can also produce toxic substances, resulting in environmental damage. This fact contradicts the long-term mission of social work aimed at achieving an adequate quality of life for as many people as possible [

3,

4,

5] and also with the newer ecosocial paradigm [

6,

7,

8]. The ecosocial paradigm strives to overcome the limited understanding of individually focused case study social work towards a holistic understanding of the interconnectedness of the entire planet with all its species [

9] (Stamm, 2023). According to [

9], the natural environment is the basis for the fulfillment of many human rights recognized today, which include the right to life, the right to an adequate standard of living, and the right to health. Despite the general agreement on this conceptual framework, the ecosocial paradigm is generally neglected, both at the level of education and research, as well as at the level of direct practice. As stated by [

10], the environmental problems that individuals and entire communities are already facing remain outside the framework of social work discourse.

The natural environment plays a key role not only for all human beings, but also for all living species found on our planet [

9]. A man, as a biological species, is existentially dependent on a healthy natural environment, therefore it is not appropriate to separate human problems from environmental problems. The ecosocial approach in social work requires the integration of the natural environment into social work, raising awareness of the risks and injustices caused by environmental problems and contributing to the urgently needed transition to a more sustainable society e.g. [

11,

12]. The environmental paradigm is also anchored in the global agenda for social work and social development, which emphasizes two basic principles, which are: environmental justice and environmental sustainability [

6]. Social workers should pay adequate attention to all aspects that are somehow connected with the environment. We do not consider it appropriate to narrow the radius of the environmental paradigm only to problems caused by the environmental crisis. We agree with the statement [

9], according to which environmental problems refer to a wide range of phenomena, from minor problems associated with climate change to the loss of greenery. The issue of environmental pollution also belongs to this category. Important factors causing environmental pollution include waste, both industrial and municipal. According to the UN, wastes are materials that are not primary products (i.e. products produced for the market), for which the producer has no further use in terms of his own purposes of production, transformation or consumption, therefore he wants to get rid of them. Waste can be generated during the extraction of raw materials, the processing of raw materials into intermediate products and final products, the consumption of final products and other human activities. And, of course, waste is also created in ordinary households. According to the directive of the European Parliament, by waste we mean a movable thing or a substance that its owner gets rid of, wants to get rid of, which is in accordance with the Waste Act or is obliged to get rid of it in accordance with special regulations [

13]. Pursuant to Act no. 372/2021 Coll. we divide waste into two basic types, namely: hazardous waste and other waste. [

14] further divide waste according to its state into solid, liquid and gaseous, and according to the place of origin into municipal, industrial and energy. According to the OECD, hazardous waste is mostly generated during industrial activities and is driven by specific production models. Such waste is of great concern because, if not adequately managed, it poses serious environmental risks: the environmental impact mainly concerns the toxic contamination of soil, water and air, which seriously damages environmental health [

15]. According to [

16], the most common method of waste disposal in low- and middle-income countries is landfilling, with most landfills being open, but few of which can be considered sanitary landfills. Despite the fact that landfills seem safe at first glance, they release various impurities into the environment. Landfill biogas, for example, contains approximately 48-56% methane, which contributes to the greenhouse gas effect. Groundwater under or near landfills is also often contaminated with hazardous and toxic waste [

16,

17,

18]. All these products have a negative impact on environmental health. Environmental health is defined as

"the theory and practice of assessing and controlling factors in the environment that may potentially adversely affect the health of present and future generations" [

19]. The original environmental approach to health reflects a predominantly natural science perspective with a focus on the direct, biophysical effects of the environment on human health, i.e. it is oriented towards the protection of human health through regulation and standards. In addition, a critical systems view of environmental health pays attention to the social environment. It recognizes the importance of factors such as clustering, social inequalities or historical, socio-economic and cultural determinants, while emphasizing the importance of political-economic and socio-economic factors such as deprivation and poverty and psychosocial processes that influence health [

20].

2. Materials and Methods

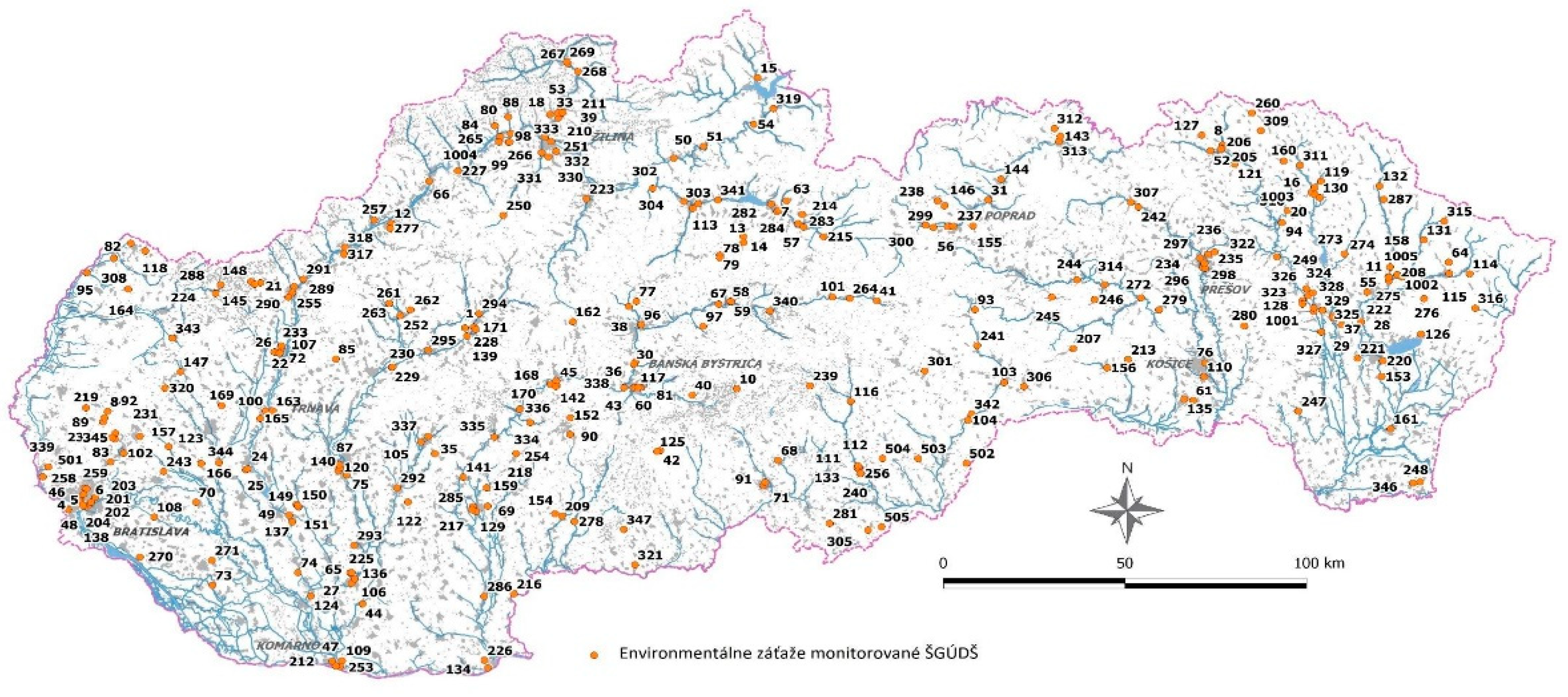

In the article, we present part of the results obtained from a more broadly conceived research focused on environmental justice in the context of social work. The Slovak Republic (hereafter SR) is literally littered with a large number of environmental burdens that threaten the health and life of its inhabitants. In

Figure 1, created by the State Geological Institute of Dionýz Štúr (hereinafter referred to as ŠGÚDŠ), it is possible to see the coverage of SR by environmental loads. The causes of their occurrence are different, but their common element is the long-term failure to solve problems associated with negative impacts on environmental health.

The main goal was to gain a better understanding of the situation surrounding the leaching residue landfill, which has been known for more than 60 years to have a negative impact on environmental health, and yet has not yet been disposed of.

The research questions to which we were looking for an answer were: How and why was Nickel Smelter Sereď created? How is it possible that, despite the knowledge about the harmfulness of nickel to the environment, production continued for so long? Why, even 30 years after the end of production, was the leaching residue waste dump not disposed of?

From the research designs, we decided to use a case study [

21,

22], which allows an intensive systematic study of a chosen subject, in the context of a given situation, while researchers respect the social environment, culture and interactions that arise in the system of which the subject under investigation is a part [

23]. Thus, the case study makes it possible to grasp, explore, describe and explain the phenomenon that is the focus of the researcher’s attention [

23]. Several authors state that the case study does not have an established methodology that would precisely determine the sequence of specific steps or sub-procedures. This fact provides the researcher with a high degree of flexibility [

24], but at the same time it places demands on him or her to define as precisely as possible the goal, context, space, etc., in which the case study is carried out [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

In our case, the analyzed unit [

33] was the leaching residue landfill, which is located in the outskirts of the city of Sereď. Our case study was carried out in a historical-political context [

28], The case study was spatially and temporally bounded [

29,

30,

31,

32]. Spatially, the study was limited to the wider surroundings of the city of Sereď, in which the landfill is located. This is an area approximately 50 km from the landfill. We limited the research to the years 1962 - 2024. The reason for such a wide time range is the start of production in the Nickel Smelter in Sered, which took place in 1962 and the ongoing impacts on the quality of the environment and environmental health in the region today. The upper time interface is given by the year 2024, i.e. the current time.

The main methods for data collection were a content analysis of secondary data, a self-constructed questionnaire and semi-structured interviews. The subject of the content analysis were the reports of institutions that carried out research on the landfill or in its surroundings, professional and scientific journals, books, official websites of the Ministry of the Environment of the Slovak Republic (hereafter referred to as the Ministry of the Environment of the Slovak Republic), websites of the city of Sered, local newspapers and NGO websites, which have been striving for years to achieve the elimination of the leachate landfill. The interviews, which lasted between 30-45 minutes, were transcribed and we used a qualitative thematic analysis to process them [

34,

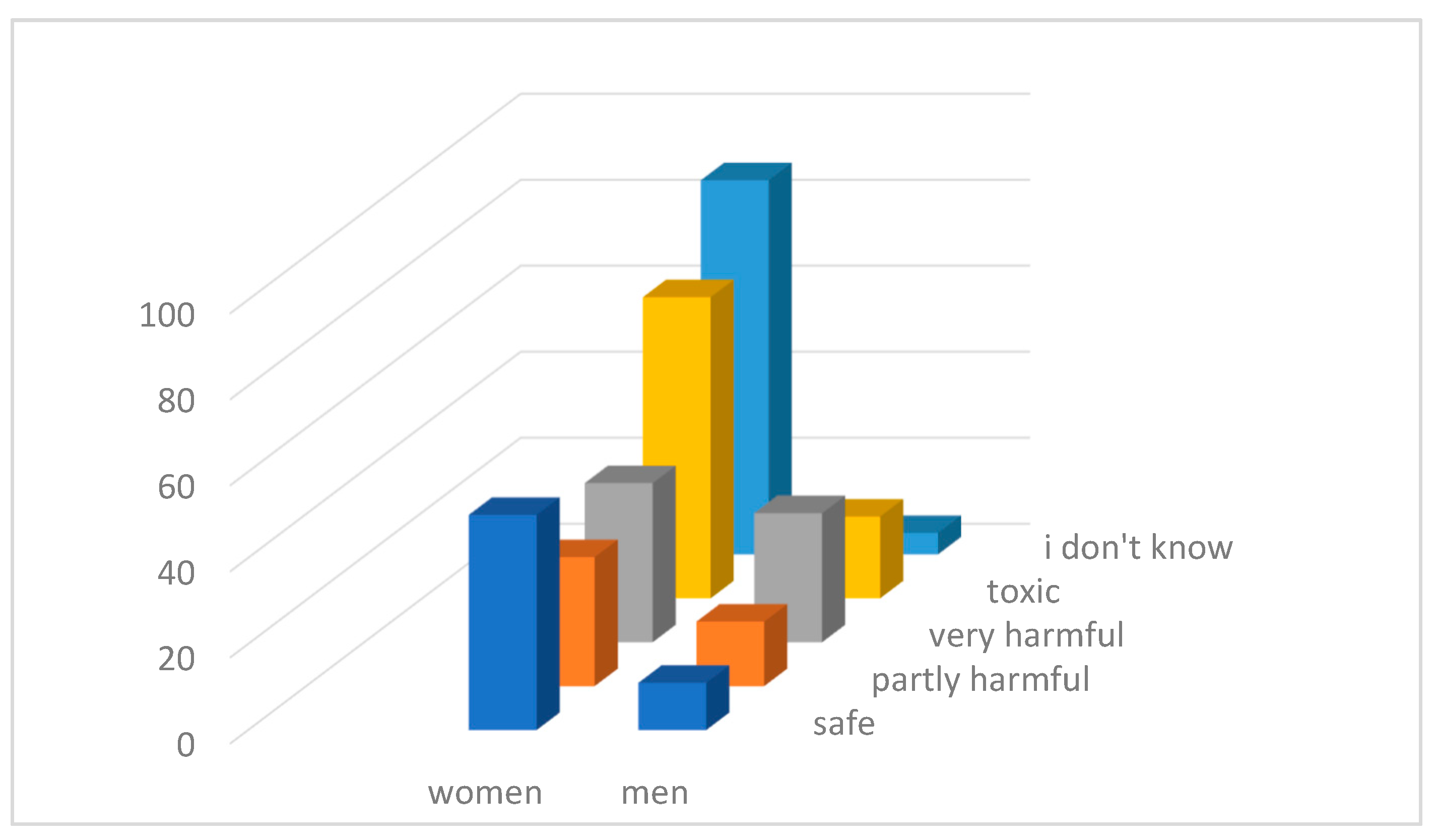

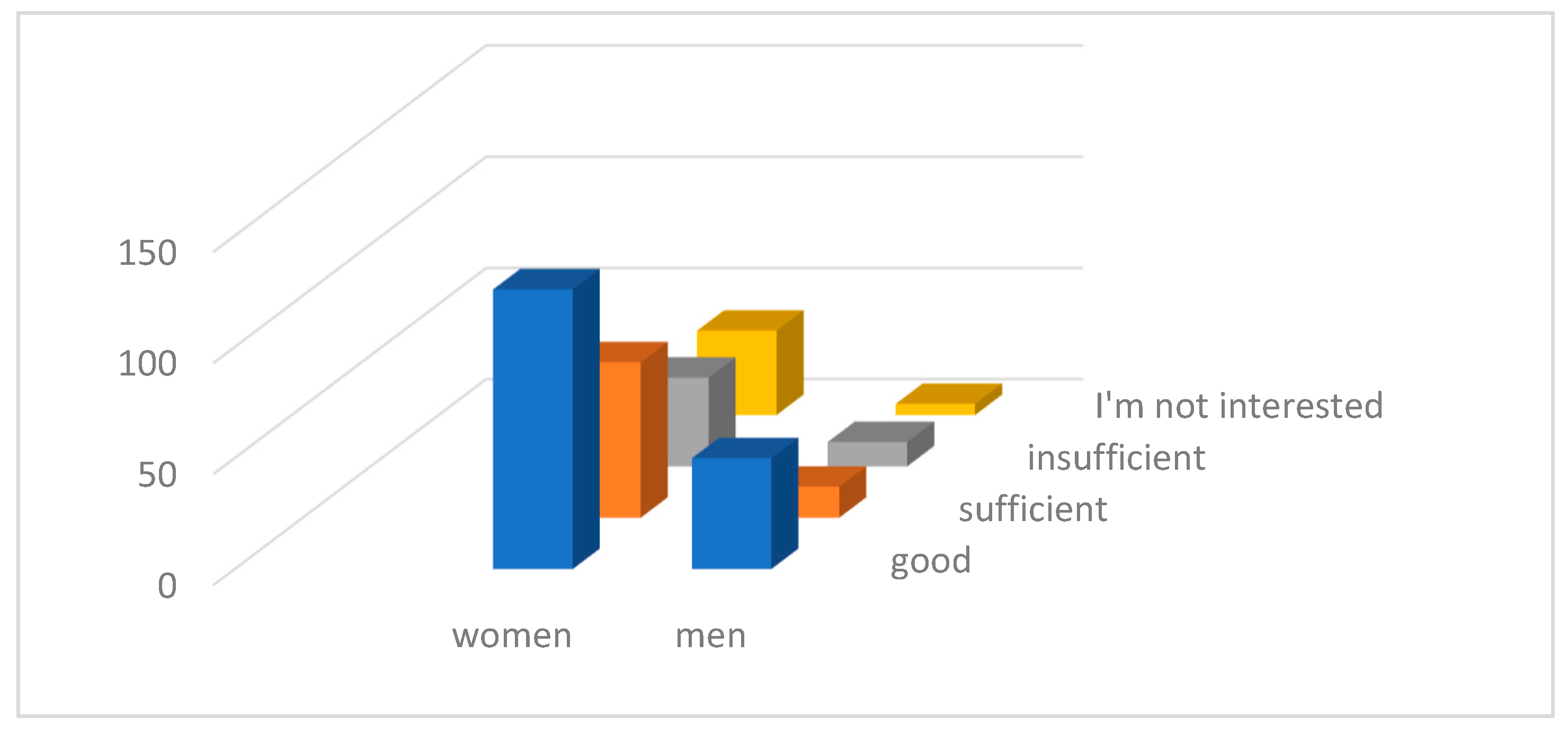

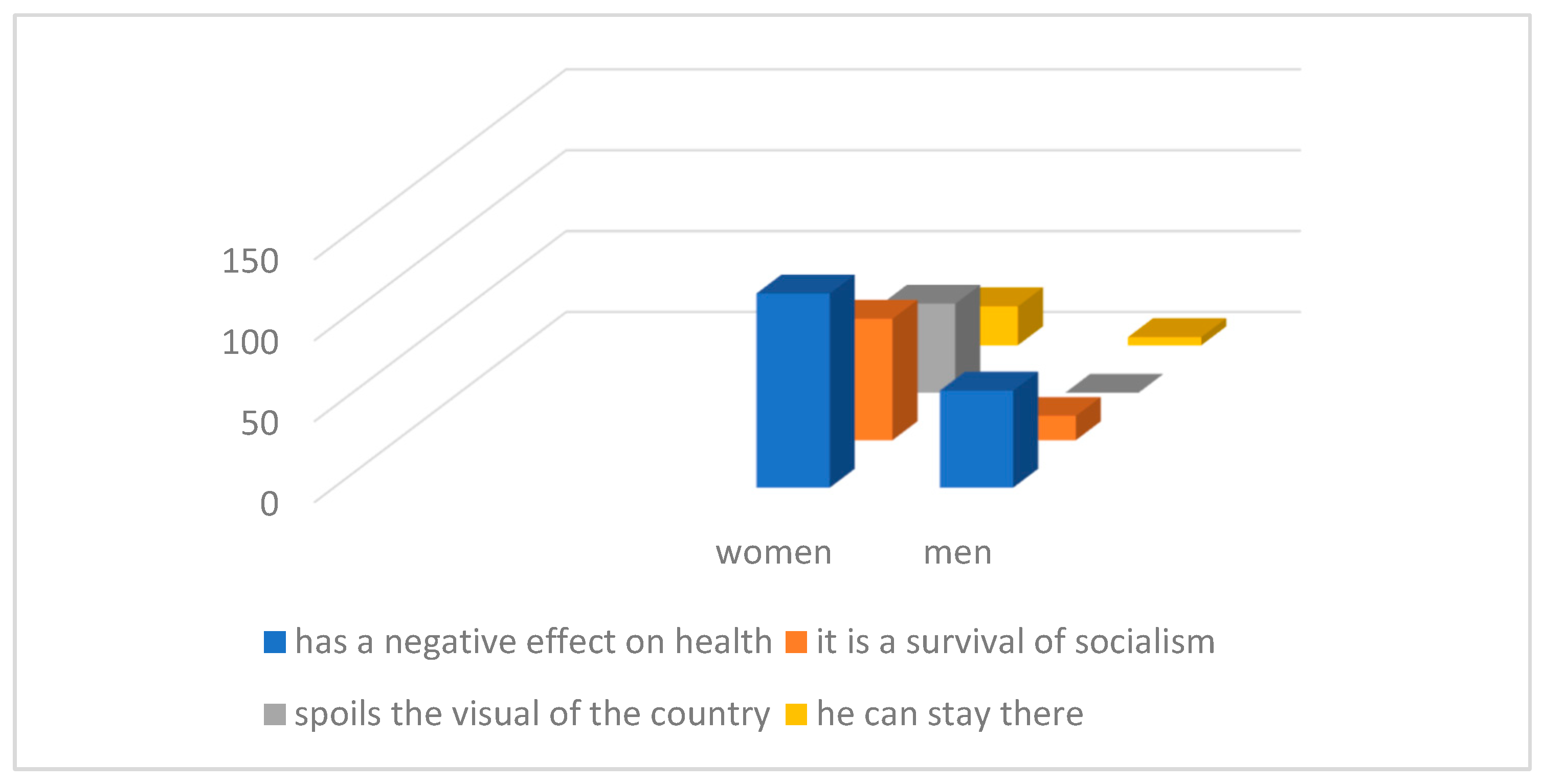

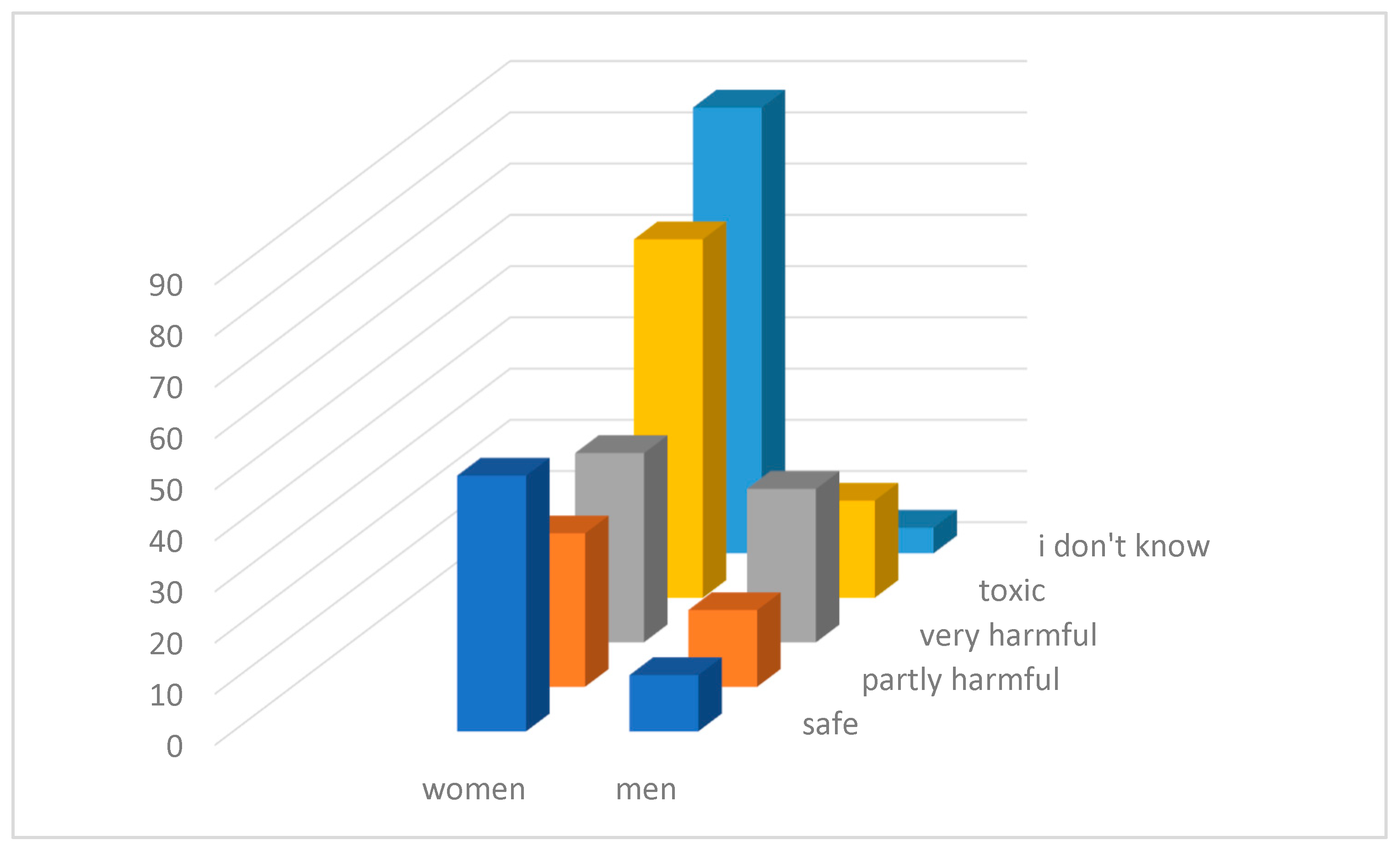

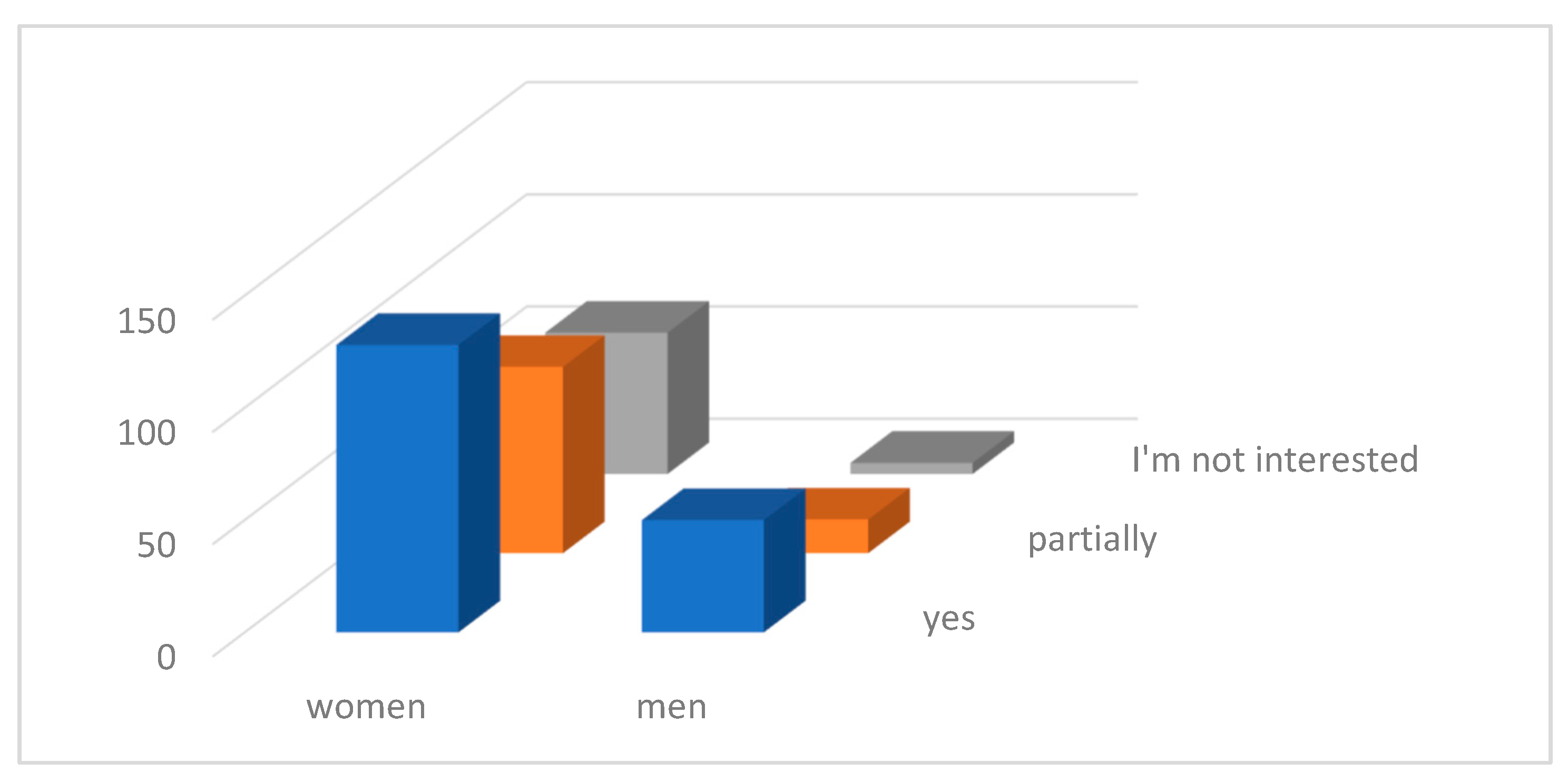

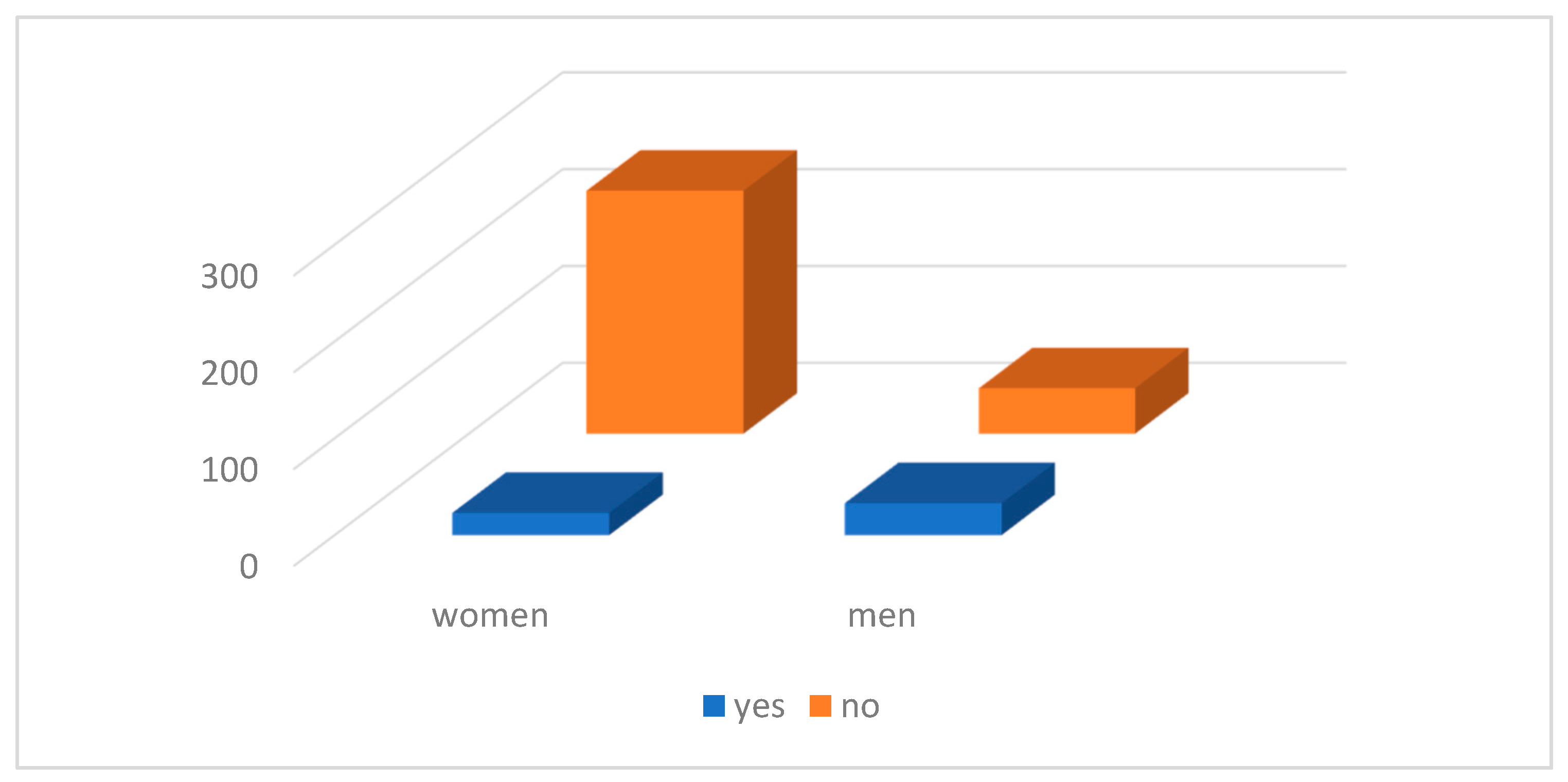

35]. The research sample consisted of 12 informants, of which 9 were men and 3 were women. This research set was created using the snow-ball technique. The self-designed questionnaire was published online. The data were collected in the period March - April 2024. The research group consisted of 354 respondents, of which 274 (77.40%) were women and 80 men (22.60%).

The data obtained by the questionnaire are presented through descriptive statistics. We processed the obtained data in such a way that they together create a text that provides answers to our research questions.

3. Results

We have obtained the information necessary for plotting the history of the leaching residue landfill through a content analysis of secondary data. The analyzed materials were reports of institutions that carried out research on the landfill or in its vicinity, official websites of the Ministry of the Environment, local newspapers and websites of NGOs that have been striving for years to achieve the elimination of the leaching residue landfill.

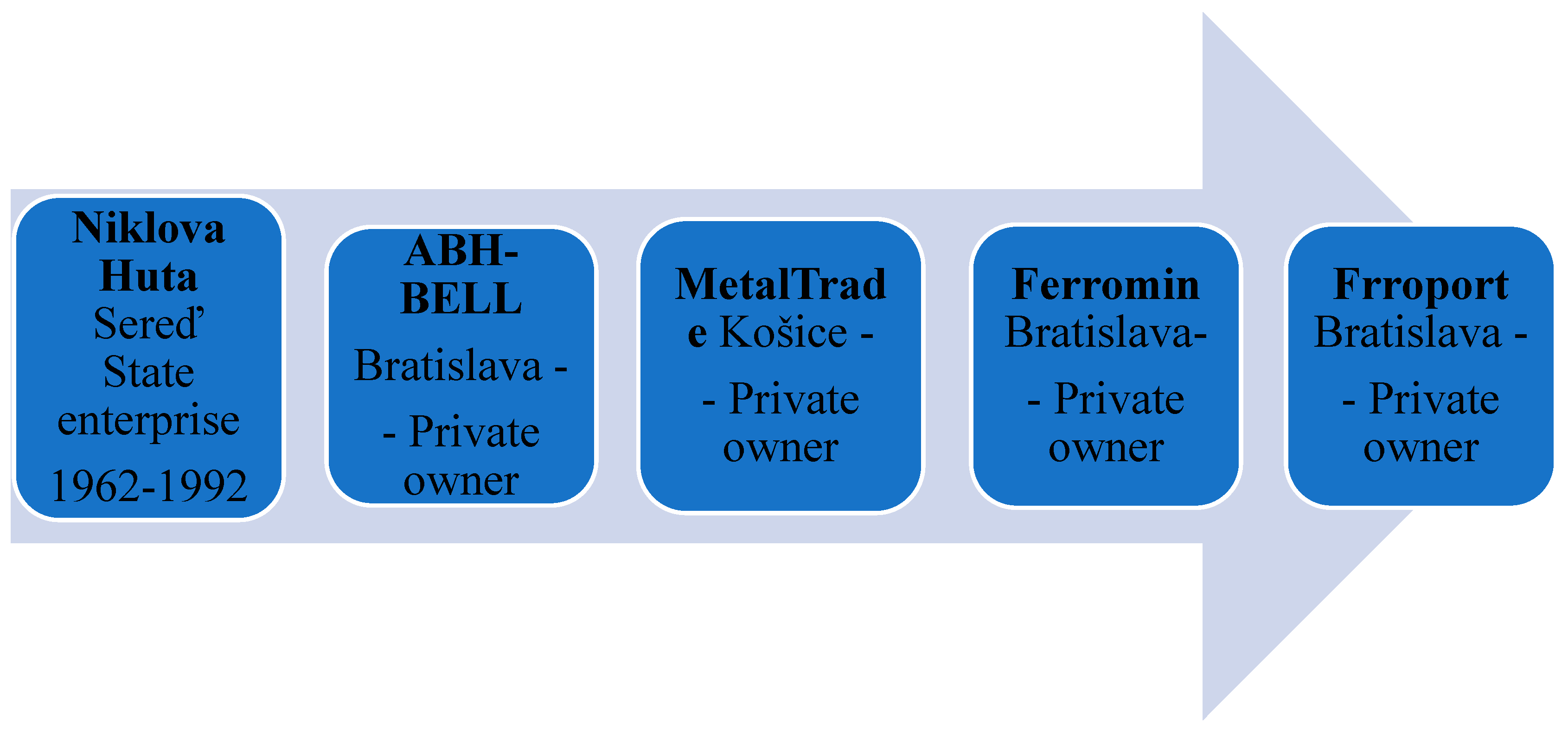

The Reasons for the Establishment of Nickel Smelter Sered

The Nickel Smelter Sered was established in 1962 as a state enterprise. At that time, Slovakia, as part of the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, was a member of the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (Comecon). Comecon was a multilateral international organization based in Moscow. When it was created, there were originally 6 Eastern European countries in it. However, their number grew rapidly. The main goal of Comecon was the coordination of the economic development, scientific and research development of the member states, as well as the coordination of their investment and trade policy, which was based on the principles of central planning [

36,

37,

38]. The decision to start nickel production in Sered was the result of Comecon’s decision, which knew that Czechoslovakia could handle the production of nickel, by which it would supply its member states.

4. Discussion

Waste, which in the past was considered unusable, is now considered an economic commodity thanks to new knowledge and technologies. Nevertheless, [

53] state that about 70% of municipal solid waste ends up in various landfills.

[

54] also draw attention to the gradual increase in electronic and electrical waste. This type of waste is an important source of recycling, as it contains metals such as copper, aluminum, iron, or steel. They are all precious metals, the reserves of which are exhaustible in nature. [

55] also draw attention to the other side of electronic and electrical waste, according to which this waste also contains heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, and arsenic, which are harmful to health. In the context of social responsibility, it is necessary to solve the question of how to process waste, which is, on the one hand, a source of necessary substances and, on the other hand, threatens environmental health through its processing. From the point of view of social work, we note that working in landfills and handling waste stored in landfills can be seen as the result of unfairly distributed power. Those who cause environmental pollution benefit from the production that produces the waste. However, waste producers are minimally involved in the removal and processing of this, often dangerous, even toxic waste. The claim that organized waste disposal creates job opportunities underlines the social injustice that manifests itself in the fact that people with low education, who are also socially excluded, are involved in waste disposal activities [

54] and they perform their work for minimal financial income. Lack of education is the cause of poor waste management. This fact can be considered a global problem, the consequence of which is environmental contamination and strengthening of social exclusion [

56]. In our case, common residents of the Sered region work on the liquidation of the leaching residue landfill, and their salaries correspond to usual salaries for workers and drivers in this area. Since their health status is not monitored in any way, it cannot be ruled out that their health is threatened not only by the content of materials contained in the landfill waste, but also by rodents, flies and other insects that live in landfills and can transmit various infectious diseases, as [

57]. In addition, the landfill near Sered has a negative impact on the health of people who live within a radius of approximately 50 km from the landfill, which represents approximately 1 million people.

Ref. [

5] states that the destruction of the environment is the result of the pursuit of economic wealth by a part of society, which reinforces economic injustice. This statement is in line with our findings, as we found that the main reason for the slow liquidation of the leaching residue landfill near Sered is the reluctance of the current owner. The Ferroport Company withdrew from the project developed by the city of Sereď, because this solution would bring it a lower profit than when they sell the leaching residuals on its own [

58]. It should be noted that this landfill is not currently a worthless pile of waste. The leaching residue contain 46-53% iron and several other usable elements such as silicon, chromium, and magnesium. If we realize that the estimated amount of the leaching residue in the landfill is between 6.5-8.5 million tons, it is a relatively valuable property. As the owner of Ferroport stated, in 2004 they sold 1,000 tons of the leaching residue and wanted to sell another 4,000 tons by the end of the year. Experts claim that at this rate, the liquidation of the leaching residue landfill will take approximately 600 years [

58]. This is a huge period of time during which the health of countless residents of the region may be at risk.

The toxicity of the leaching residue landfill has already been confirmed, which was the reason for its cultivation by the city of Sereď. The gradual slow sale of leaching residue waste also means the "opening" of a partially rehabilitated landfill. Ferroport is gradually liquidating the forested upper part, which facilitates easier penetration of alkaline waste into the environment.

Our case study confirms the findings of [

59] that the environmental crisis needs to be reflected in the context of social justice, which belongs to the domains of social work.

Strengths and Limitations

This study is unique in Slovakia as similar research, focused on a systemic approach to the so-called old environmental burdens, i.e. to burdens whose foundations are in socialism, has not been realized yet. The environmental paradigm itself is not sufficiently known in the Slovak environment. The case study was focused only on one location, which may mean that some facts are tied only to the location where the landfill is located. However, we consider the conceptual model created by us to be usable in solving other environmental burdens. The study unequivocally confirms a strong role of the state in the creation of environmental burdens, but also its obligations in their removal.

Ethical Aspects of the study

During the implementation of the case study, the ethical principles of scientific work were strictly followed, from truthful information to research participants, voluntary participation of respondents, anonymity of respondents to objectivity in data processing. This study was financially supported by the project: APVV-20-0094 Environmental justice in the context of social work.

5. Conclusion

The operation in Nickel Smelter Sered was finished in 1992, but to this day it pollutes the environment in the wide outskirts of the city of Sered. The reasons for this state of affairs must also be sought in the deep past, as the government of Czechoslovakia assumed the disposal of waste from the processing of Albanian ore. Memorialists claim that research was also carried out in the company, which also investigated the possibilities of further processing of the leaching residuals. Some experiments were even carried out. However, at that time, the use of waste proved to be too financially demanding and not very effective. The whole pile of leaching residue is rightly called a toxic legacy of socialism [

45].

Another reason was the lack of legislation that would have sufficiently protected the environmental health of the Slovak population at the time of privatization after 1990. In Slovakia, we have more than 2,000 registered loads and thousands of illegal landfills, which threaten the environmental health of not only the residents of the Slovak Republic, but also the residents of neighboring countries.

In our research, we found out that the main cause of the slow liquidation of the leaching residuals landfill near Sered can be attributed to the reluctance of the current owner to participate in the project with which the city of Sered wanted to speed up the liquidation of the landfill.

The failure to solve the problems caused by environmental burdens in the Slovak Republic is also helped by the fact that individual scientific fields investigate this issue only in the context of their scientific field. Ecological, environmental and natural sciences are dominant in this area. Social work brings into the discourse on environmental burdens the discourse on issues of the right to a healthy environment, or environmental justice. The potential of the social work profession lies precisely in its possible contribution to opening discourse in an interdisciplinary context and "bringing" environmental problems into public discourse.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and M.O.; Methodology J.L. and M.O.; Validation, J.L. and M.O.; Formal Analysis, J.L. and M.O.; Investigation, J.L. and M.O.; Resources, J.L. and M.O.; Data Curation, J.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, J.L.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.O.; Visualization, M.O.; Supervision J.L. ; Project Administration, J.L. and M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the APVV (SRDA)-20-0094 Environmental justice in the context of social work

Institutional Review Board Statement

Full ethics approval was not required. The implementation of the study is in accordance with the ethical rules of The Slovak Research and Development Agency. The study was conducted with the approval of the University of Nebraska Lincoln Institutional Review Board (protocol code #20200320177EX approved 4 December 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Inquiries regarding the availability of the data included in this study may be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ojeda-Benitez, S.; Aguilar-Virgen, Q.; Taboada-Gonzalez, P.; et al. Household hazardous wastes as a potential source of pollution: a generation study. In: Waste Manag Res. 2013;31(12):1279–1284. [CrossRef]

- 2. Uddin ,S.M.N.; Li, Z., Adamowski, J.F.; et al. Feasibility of ‘greenhouse system’ for household greywater treatment in nomadic-cultured communities in peri-urban ger areas of Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia: way to reduce greywater-borne hazards and vulnerabilities. In: J Clean Prod. 2016; 114:431–442. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, I. Reclaiming Social Work: Challenging Neo-liberalism and Promoting Social Justice, London: Sage. 2008; Available online: https://www.torrossa.com/en/resources/an/4913062.

- Dominelli, L. Green Social Work: From Environmental Degradation to Environmental Justice, Cambridge: Polity Press. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Peeters, J. The place of social work in sustainable development: towards ecosocial practice, In: International Journal of Social Welfare, 2012; 21: 287–98. [CrossRef]

- Levická, J. Environmentálna sociálna práca. Trnava: Fakulta sociálnych vied, UCM. 2023; ISBN 978-80-572-0379-7.

- Krings, A.; Copic, C. Environmental justice organizing in a gentrifying community: Navigating dilemmas of representation, issue selection, and recruitment. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 102(2), 2020; 154–166. [CrossRef]

- Närhi, K., Mathies;A.-L. Conceptual and historical analysis of ecological social work. In: McKinnon, Jennifer & Alston, Margaret (eds.) Ecological social work: toward sustainability. Palgrave Macmillan, 21-38 London: Routledge. 2016. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315615912.

- Stamm, I. Human Rights-Based Social Work and the Natural Environment: Time for New Perspectives. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work,2023; 8 , 42–50 . 2023. [CrossRef]

- Staub-Bernasconi, S. (2018). Soziale Arbeit als Handlungswissenschaft: Soziale Arbeit auf dem Weg zu kritischer Professionalität (2nd ed.) 2018. Budrich. ISBN: 9783825247935.

- Boetto, H. “A Transformative Eco-Social Model: Challenging Modernist Assumptions in Social Work.” British Journal of Social Work 47 (1): 48–67. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Matthies, A.-L.; Närhi, K. 2017. The Contribution of Social Work and Social Policy in Ecosocial Transition of Society. 2017; In: Ecosocial Transition of Societies: Contribution of Social Work and Social Policy, edited by A.-L. Matthies and K. Nikku, B. R., H. B. Ku, and L. Dominelli, eds. The Routledge Handbook of Green Social Work. 2018; London: Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008; on waste and repealing certain Directives. Document 32008L0098. [online]. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/98/oj.

- Soldán, M.; Soldánová, Z.; Michalíková, A. Ekologické nakladanie s materiálmi a odpadmi. Slovenská technická univerzita v Bratislave, 2005; 103 pg. ISBN 80-227-2223-5.

- OECD. Industrial and hazardous waste. In: Environment at a Glance 2013;: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris.

- Gutherbelt, J. Urban recycling cooperatives: building resilient communities. London, New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group; 2016; p. 183.

- Xi, B.; Jiang, Y.; Li ,M.,;et al. Groundwater pollution and its risks in solid waste disposal sites. In: Xi B. et al. Optimization of solid waste conversion process and risk control of groundwater pollution. In: Springer Briefs in Environmental Sciences 2016; ISBN 978-3-662-49462-2 (E-BOOK). [CrossRef]

- Mikac, N.; Cosovic, B.; Ahel, M.; et al. Assessment of groundwater contaminant in the vicinity of a municipal solid waste landfill (Zagreb, Croatia). In: Water Sci Technol. 1998; 37(8):37–44.

- WHO. Environmental Protection Act 1994. Available online: https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/whole/html/inforce/current/act-1994-062.

- Kiger, M. E.; Varpio, E.; L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med Teach. 2020; Aug;42(8):846-854.. Epub 2020 May 1. PMID: 32356468. [CrossRef]

- Bergen, A.; White, A. A case for case studies: exploring the use of case study design in community nursing research. In: Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2000; 31(4), 926–934. [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. The case study method as a tool for evaluation. Current Sociology, 40(1), 121–137. 1992. [CrossRef]

- Bromley, D. 1986. The case-study method in psychology and related disciplines. Ches ter, England: Wiley.

- Chrastina, J. Případová studie – metoda kvalitatívní výzkumní strategie a designování výzkumu. Olomouc: PF UP v Olomouci. 2019; ISBN: 978-80-244-5373-6.

- Wholey, J. S.; Hatry, H.P.; Newcomer, K. E. Handbook of practical program evaluation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1994; Available online: http://www.blancopeck.net/HandbookProgramEvaluation.pdf.

- Yount, W. R. Research Design and Statistical Analysis in Christian Ministry. Fort Worth, Texas: Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary Fort Worth. 2006;

- De Marrais, K. B.; Lapan, S. D. Foundations for Research. Methods of Inquiry in Education and the Social Sciences. London, UK: Routledge. 2003. ISBN 9780805836509.

- Ulin, P. R.; Robinson, E. T.; Tolley, E. E. Qualitative methods in public health: a fi eld guide for applied research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. 2005; Available online: https://content.e-bookshelf.de/media/reading/L-7690576-38cc771cc4.pdf.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 2006. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(2), 219–245. [CrossRef]

- Levy, J. Case Studies: Types, Designs, and Logics of Inference. Conflict Management and Peace Science, 25, 1–18. 2008; Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/i26275100.

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikg, A. The case study approach. In: BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11(100), 1–9. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100.

- YIN, R. K. 2014. Case study research: design and methods. Th ousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 2014; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308385754_Robert_K_Yin_2014_Case_Study_Research_Design_and_Methods_5th_ed_Thousand_Oaks_CA_Sage_282_pages.

- Yin, R.K. Case study research: design and methods. 2003; 3rd E Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Krieger, N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2001; 30:668–677. [CrossRef]

-

Kaplan, K. Rada vzájemné hospodářské pomoci a Československo 1957-1967. 1. vyd. Praha: Karolinum, 2002; 234 s. ISBN 80-246-0417-5.

- Grzybowski, K. The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance and the European Community. In: American Journal of International Law. 1990; 84(1):284-292. [CrossRef]

- Faudot, A.; Marinova, T.; Nenovsky, N. Comecon Monetary Mechanisms. A history of socialist monetary integration (1949 – 1991). Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/114701/.

- Daniel, B. NIKLOVÁ huta je jedno z najznečistenejších miest v Seredi a jej okolí. Prečítajte si o nej zopár faktov a pozrite si zaujímavé fotky. 2022; Available online: https://seredsity.sk/tag/niklova-huta/.

- From Black to Green. 2020; [online]. Available online: https://www.peticie.com/z_iernej_na_zelenú_peticia_za_rieenie_environmentalnych_zaai_sere__niklova_huta__areal_byvaleho_podniku_a_skladka_luenca_skezga221_a_skezga222.

- Dragomir, E. Vytvorenie Rady pre vzájomnú hospodársku pomoc z rumunských archívov, Historický výskum, 88(240): 355-379, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Kaser, M.C. 1967. RVHP: Integračné problémy plánovaných ekonomík. Oxford: Oxford University Press.1967; ISBN 0-192-14956-3.

- Lányi , K. Kolaps trhu RVHP. Ruské a východoeurópske financie a obchod, 29(1), 68–86. 1993; Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27748962.

- Michaeli, E., Boltižiar, M. Vybrané lokality environmentálnych záťaží v zaťažených oblastiach Slovenska. Geografické štúdie, 14(1):18-48. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Slahučková, Z. Rozhovor: Niklovej hute zasvätil 20 rokov svojho života. Seredčan Jozef Valábek porozprával o rizikovej práci v závode. 2021; Available online: https://seredsity.sk/niklovej-hute-zasvatil-20-rokov-svojho-zivota-seredcan-jozef-valabek-porozpraval-o-rizikovej-praci-v-zavode-rozhovor-2/.

- Michaeli, E. et. al. Skládka priemyselného odpadu lúženca ako príklad environmentálnej záťaže pri bývalej Niklovej hute v Seredi. 2012; Available online: http://147.213.211.222/sites/default/files/2012_2_063_068_michaeli.pdf.

- Moncľová, V. Posolstvo Niklovej huty. 2014; Available online: http://www.mladireporteri.sk/posolstvo-niklovej-huty-1-miesto-v-sutazi-litter-less-11-14-rokov-clanok.

- Klaučo, S. Súčasný stav a prognóza kvality podzemných vôd v širšom okolí skládky lúženca a popolčeka Niklovej huty š. p. v Seredi. 1994; Expertízna štúdia SkOV – Bratislava.

- Škultéty, P. Vplyv environmentálnych záťaží na charakter krajiny. In: Zborník vedeckých prác Katedry ekonómie a ekonomiky FM. Prešov: PU, 2008; ISBN 978-808068-798-4, s. 278-285.

- Monitoring environmentálnych záťaží 2021. [online]. Bratislava: ŠGÚDŠ. Dostupné na: https://apl.geology.sk/mapportal/img/pdf/MapaEZ.pdf.

-

Register environmentálnych záťaží SR. 2024; Available online: https://envirozataze.enviroportal.sk/.

- Naeem M.; Ozuem W. Understanding misinformation and rumors that generated panic buying as a social practice during COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from twitter, YouTube and focus group interviews. In: Information Technology & People, 35(7), 2140–2166. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Awasthi, AK.; Wei, F.; Tan, Q.; Li, J. Single use plastics: production, usage, disposal and adverse impacts, Science of the Total Environment, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bender, A.P.; Bilotta, P. Circular Economy and Urban Mining: Resource Efficiency in the Construction Sector for Sustainable Cities. Sustainable Cities and Communities, 2020. In: Journal Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham, pp. 68-81. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Guthberlet, J.; Uddin, A. M. N. Household waste and health risks affecting waste pickers and the environment in low- and middle-income countries. In: International Journal of Occupational Environmental Health, 23(4):299-310. 2017. [CrossRef]

- De Souza Melaré, V. A.; Gonzáles, S. M.; FACELI, K.; CASADEI, V. Technologies and decision support systems to aid solid-waste managment: A systematic review. [online]. Waste Managment. 59:567-584 2017. [CrossRef]

- Chileshe, B.; Moonga, S. Alternatives for dumpsite scavenging: the case of waste pickers at Lusaka’s Chunga Landfill Int. J. Humanit. 2017; Soc. Sci. Educ. 4 40–51.

- Vrabec, N. Likvidácia lúžencovej hory je v nedohľadne. 2004; [online]. Available online: https://hnonline.sk/finweb/podniky-a-trhy/41765-likvidacia-luzencovej-hory-je-v-nedohladne.

- Nöjd, T.; Kannnasoja, S.; Niemi, P.; Ranta- Tyrkkö, S. NÄRHI, K. Social welfare professionals´views on addressing anvironmental issues in social work in Finland. Nordic Social Work Research, 1–15. 2023. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).