Submitted:

29 October 2024

Posted:

31 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

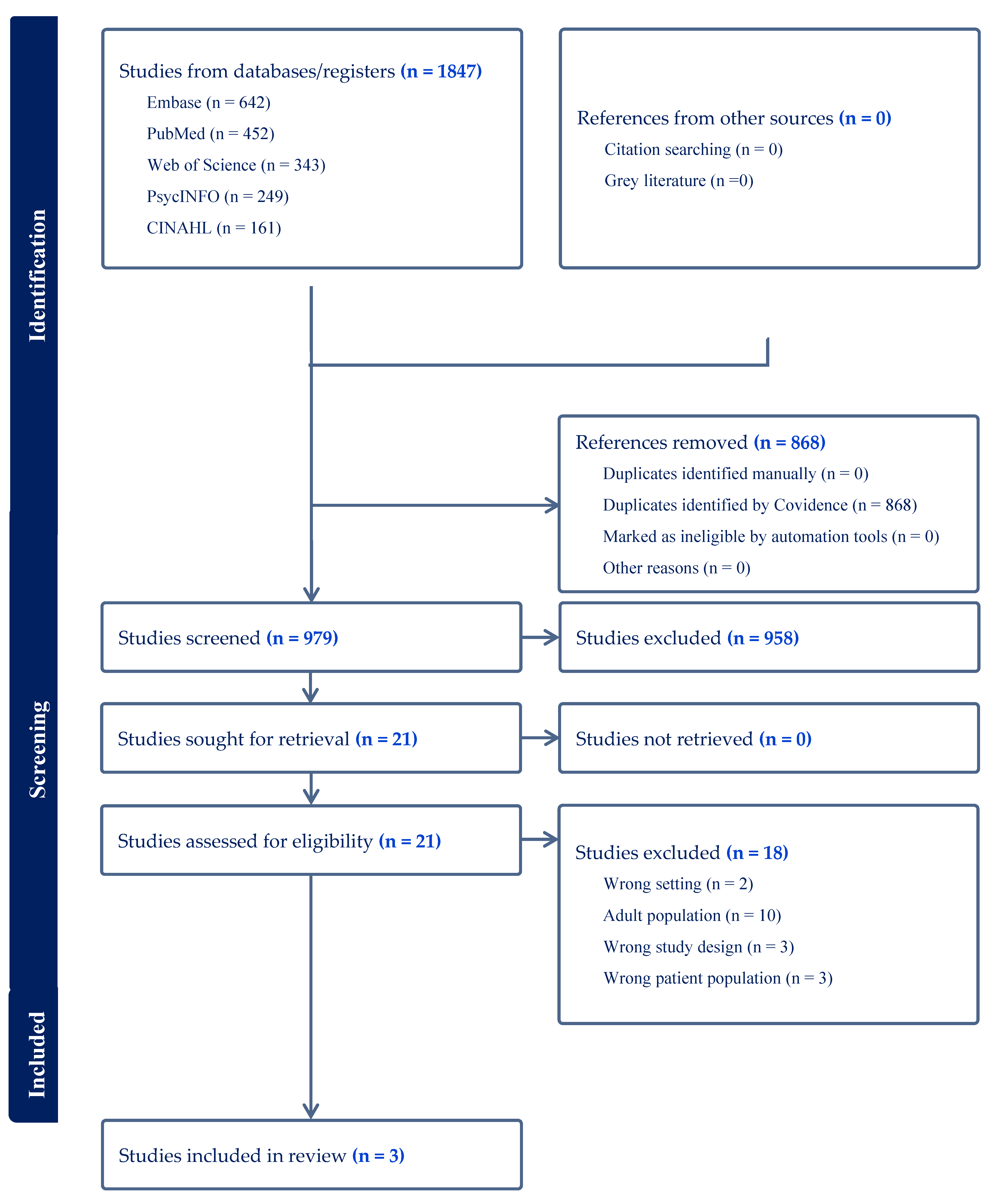

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Information Sources

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

2.4. Selection Process

2.5. Data Extraction

2.6. Quality Assessment

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristic of Included Studies

3.2. Quality Appraisal of Included Studies

3.3. Narrative Synthesis

3.3.1. Independecne

3.3.2. Connecting with Others

3.3.3. Equitable Multisensory Spaces

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations of This Review

4.2. Implications for Practice

4.3. Suggestions for Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dinu Roman Szabo M, Dumitras A, Mircea DM, Doroftei D, Sestras P, Boscaiu M, et al. Touch, feel, heal. The use of hospital green spaces and landscape as sensory-therapeutic gardens: a case study in a university clinic. Front Psychol. 2023;14(November):1–20. [CrossRef]

- Cuturi LF, Cappagli G, Yiannoutsou N, Price S, Gori M. Informing the design of a multisensory learning environment for elementary mathematics learning. J Multimodal User Interfaces [Internet]. 2022;16(2):155–71. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson A, Calder A, Elliott B, Rodger R, Mulligan H, Hale L, et al. Disabled People or Their Support Persons’ Perceptions of a Community Based Multi-Sensory Environment (MSE): A Mixed-Method Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(19). [CrossRef]

- Putrino D, Ripp J, Herrera JE, Cortes M, Kellner C, Rizk D, et al. Multisensory, Nature-Inspired Recharge Rooms Yield Short-Term Reductions in Perceived Stress Among Frontline Healthcare Workers. Front Psychol. 2020;11(November):1–6. [CrossRef]

- Cameron A, Burns P, Garner A, Lau S, Dixon R, Pascoe C, et al. Making Sense of Multi-Sensory Environments: A Scoping Review. Int J Disabil Dev Educ [Internet]. 2020;67(6):630–56. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Strøm BS, Ytrehus S, Grov EK. Sensory stimulation for persons with dementia: A review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(13–14):1805–34. [CrossRef]

- Unwin KL, Powell G, Jones CRG. A sequential mixed-methods approach to exploring the experiences of practitioners who have worked in multi-sensory environments with autistic children. Res Dev Disabil [Internet]. 2021;118(April):104061. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Unwin KL, Powell G, Jones CRG. The use of Multi-Sensory Environments with autistic children: Exploring the effect of having control of sensory changes. Autism. 2022;26(6):1379–94. [CrossRef]

- Basadonne I, Cristofolini M, Mucchi I, Recla F, Bentenuto A, Zanella N. Working on cognitive functions in a fully digitalized multisensory interactive room: A new approach for intervention in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Sci. 2021;11(11). [CrossRef]

- Novakovic N, Milovancevic MP, Dejanovic SD, Aleksic B. Effects of Snoezelen—Multisensory environment on CARS scale in adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Res Dev Disabil [Internet]. 2019;89(July 2018):51–8. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Lotan M, Gold C. Meta-analysis of the effectiveness of individual intervention in the controlled multisensory environment (Snoezelen®) for individuals with intellectual disability. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2009;34(3):207–15. [CrossRef]

- Fakoya OA, McCorry NK, Donnelly M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: a scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2020 Dec 14;20(1):129. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-020-8251-6. [CrossRef]

- Pu L, Pan D, Wang H, He X, Zhang X, Yu Z, et al. A predictive model for the risk of cognitive impairment in community middle-aged and older adults. Asian J Psychiatr [Internet]. 2023;79(December 2022):103380. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Liu CJ, Chang PS, Griffith CF, Hanley SI, Lu Y. The Nexus of Sensory Loss, Cognitive Impairment, and Functional Decline in Older Adults: A Scoping Review. Gerontologist. 2022;62(8):E457–67. [CrossRef]

- Vazini Taher A, Khalil Ahmadi M, Zamir P. Effects of multi-sensory stimulation on cognition function, depression, anxiety and quality of life in elderly persons with dementia. Int J Sport Stud [Internet]. 2015;5(3):355–60. Available from: http:www.ijssjournal.com.

- Helbling M, Grandjean ML, Srinivasan M. Effects of multisensory environment/stimulation therapy on adults with cognitive impairment and/or special needs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spec Care Dent. 2024;44(2):381–420. [CrossRef]

- Griffiths S, Dening T, Beer C, Tischler V. Mementos from Boots multisensory boxes – Qualitative evaluation of an intervention for people with dementia: Innovative practice. Dementia. 2019;18(2):793–801. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez A, Marante-Moar MP, Sarabia C, De Labra C, Lorenzo T, Maseda A, et al. Multisensory Stimulation as an Intervention Strategy for Elderly Patients with Severe Dementia: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31(4):341–50. [CrossRef]

- Cox H. Multisensory Environments for Leisure Promoting Well-being in Nursing Home Residents With Dementia. J Gerontol Nurs. 2004;37–46.

- Schofield P. A pilot study into the use of a multisensory environment (Snoezelen) within a palliative day-care setting. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2003;9(3):124–30. [CrossRef]

- Veritas Health Innovation. Covidence systematic review software [Internet]. Melbourne; 2023. Available from: www.covidence.org.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88:1–11.

- Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018. [Internet]. Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. 2018. Available from: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf%0Ahttp://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/.

- Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A, Petticrew M, Arai L, Rodgers M, et al. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. A Prod from ESRC Methods Program. 2006;(April 2006):211–9.

- Litwin S, Clarke L, Copeland J, Tyrrell J, Tait C, Mohabir V, et al. Designing a Child-, Family-, and Healthcare Provider–Centered Procedure Room in a Tertiary Care Children’s Hospital. Heal Environ Res Des J. 2023;16(3):195–209. [CrossRef]

- Malysheva E, Skripnikova E, Logina T. Age-related peculiarities of changes in functional state of a person in the recreation areas. BIO Web Conf. 2020;22:01028. [CrossRef]

- Emmerson C, Frayne C, Goodman A. How much would it cost to increase UK health spending to the European Union average? The Institute for Fiscal Studies. 2002.

- Ansah JP, Chiu CT. Projecting the chronic disease burden among the adult population in the United States using a multi-state population model. Front Public Heal. 2023;10. [CrossRef]

- Ogugua, J. Muonde, M. Maduka, C. Olorunsogo, T. Omotayo, O. Demographic shifts and healthcare: A review of aging populations and systemic challenges. Int J Sci Res Arch. 2024;11(1):383–95.

- Hudson K. Practitioners’ views on involving young children in decision making: Challenges for the children’s rights agenda. Aust J Early Child. 2012;37(2):4–9. [CrossRef]

- Bollig G. Ageism and Lack of Shared Decision-Making is a Problem in Healthcare and Geriatrics. Int J Clin Stud Med Case Reports. 2024;35(4):1–4. [CrossRef]

- Langmann E. Vulnerability, ageism, and health: is it helpful to label older adults as a vulnerable group in health care? Med Heal Care Philos. 2023;26(1):133–42.

- Cerino A. The importance of recognising and promoting independence in young children: the role of the environment and the Danish forest school approach. Educ 3-13 [Internet]. 2023;51(4):685–94. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee D, Rabheru K, de Mendonca Lima CA, Ivbijaro G. Role of Dignity in Mental Healthcare: Impact on Ageism and Human Rights of Older Persons. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry [Internet]. 2021;29(10):1000–8. Available from. [CrossRef]

- Kwan C, Gitimoghaddam M, Collet JP. Effects of social isolation and loneliness in children with neurodevelopmental disabilities: A scoping review. Brain Sci. 2020;10(11):1–36. [CrossRef]

- Park G, Nanda U, Adams L, Essary J, Hoelting M. Creating and Testing a Sensory Well-Being Hub for Adolescents with Developmental Disabilities. J Inter Des. 2020;45(1):13–32. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Treaty Ser [Internet]. 2006;2515:3. Available from: http://www.un.org/disabilities/.

- United Nations. The United Nations convention on the rights of the chid. Vol. 1577. 1989.

- Americans with Disabilities Act. of 1990, 42 U.S.C. 12101 (1990). https://www.ada.gov/pubs/adastatute08.htm.

- Equality Act [Internet]. UK; 2010. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents.

- Disability Discrimination Act [Internet]. Australia; 1992. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2004A04426/latest/text.

| Intergenerational | Sensory spaces |

|---|---|

| Intergen* OR Child* OR Adolescen* OR “Young adult*” OR Adult* OR “older adult*” OR elderly |

“sensory room*” OR “sensory space*” OR “sensory environment*” OR “multi-sensory environment*” OR “quiet room*” |

| Author and Country of Origin | Aim(s) | Design | Participants |

Measures employed or interview questions | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Litwin et al (2023) Canada |

To co-design new paediatric procedure room prototypes with children, caregivers, and healthcare providers |

Qualitative design employing observation, semi-structured interviews and co-design workshops. | n=11 children and youth; n=38 physicians; n=8 youth and parent advisors | Not provided | 1 Control: Helathcare professionals and patients need to be able to control features in the environment; 2 Privacy: Spaces must be designed with features to help patients feel safe, secure, and respected during procedures; 3 Evidence-based pain-reduction and distraction methods: Positive distraction tools available for all patients. Distractions must be age appropriate and flexible to suit individual needs; 4 Sensory environment: Patients and healthcare providers should be able to modify sensory stimuli in the room; 5 Human factors organization of the space and equipment: Rooms must enable the seamless flow of people and storage of equipment; 6 Equitable spatial design: Create a space that is inclusive for all patients and families; 7 The journey: experience of a medical procedure begins prior to arriving at the hospital. |

| Malysheva et al (2020) Russia |

To study the physiological effects of staying in park areas in people of different ages. | Pre-post-test experimental design | n=20 children aged 14-15 years; n=20 students aged 18-20 years; n=11 older people aged 69-76 years |

Respiratory rate (RR), respiratory minute volume (RMV), maximal pulmonary ventilation (MPV) were recorded with a spirograph. Anfimov’s table technique used to assess attention. Auditory memory test (word recall task). Blood pressure, heart rate and hemodynamics. | Students made fewer mistakes, the number of selected symbols, the capacity of visual memory, the speed of information processing increase, but their attention span decreased. After a walk in the park, their levels of state anxiety decreased. In older people mental capacity slightly improved, which showed itself in an increase in intellectual efficiency, accuracy in completing tasks, as well as an improved visual and auditory memory, though attention span decreased. There was a positive effect on hemodynamic parameters in elderly people. |

| Wilkinson et al (2023) New Zealand |

To explore disabled users’ experiences of the MSE that they operate and support with a view to expanding access to MSE-type environments within the metropolitan area. Given the paucity of evidence internationally and nationally of the benefits of community-based MSEs, it was deemed relevant to understand who uses the MSE and their perceptions of it. | Mixed methods employing an electronic survey and semi-structured interviews. | n=104 survey responses, n=74 parents, n=15 MSE room users, n=12 support persons. Age < 4 n=45, 5-21 n=32, >21 n=19. n=14 Interviews, disabled adult MSE users n=3 males, n=5 females aged 20-70 years; child MSE users n=5 males, n=3 females aged 1-11 years old. |

Survey collected data on: (i) indication of whether the respondent was the MSE room user (participant) or completing the e-survey on behalf of a room user (support person); (ii) participant demographics (age, gender, ethnicity, region where they resided, who (if anyone) accompanied the room user to the MSE, mode of transport, and frequency and length of SCMSE room use); (iii) barriers to access; and iv) reported participant disability via the Washington Group Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS) Demographics: age, gender, ethnicity. Interview guide: Can you share your thoughts along with some examples of your experiences of using the multisensory room? Prompts: Reasons for using the room, benefits, or barriers, if you could change anything in the room what might it be and why? Could you share your thoughts about your equipment preferences? Prompts: What equipment do you enjoy using and why? Is there other equipment that you would like added or removed from the multisensory room? Please explain. Talk me though what is involved for you (and your support persons) in getting ready and then getting to the multisensory room. Prompts: Transport, the path of travel from the building entrance to the multisensory room Talk me through what is involved for you (and your support persons) in the return journey, from the multisensory room to home. Can you share your experiences and some examples about the accessibility of information about the multisensory room. Prompts: Can you tell us about how you found out about the multisensory room (i.e., who referred you and why?). What information was available (e.g., online, brochures)? Did the information available meet your needs (i.e., was there enough information or too much)? Where and how did you go about finding further information if you needed to? Is there anything that could be done differently to enhance the information about the multisensory room? Who accompanies them to the room. Understanding the impairments, they experience/sensory systems affected |

Survey findings: Overall, 131 participants responded to the e-survey, representing a response rate of 8.8%. Most of the child room users were male; conversely, most of the adult users were female. The types of limitations, as per the WSS-GS, of the room users included: Seeing (n = 2), Hearing (n = 1), Walking (n = 6), Concentration (n = 10), Self-care (n = 14), and Communication (n = 9). Frequency of room use was every two weeks n=8, Monthly n=20, 2-4 times a year n=25, one a year or less n=51. Barriers to MSE access included booking system n=11, distance to MSE n=4, time constraints n=6, location of front desk n=3, MSE too overwhelming n=2, staff shortages n=5, upstairs location n=8, other n=4. Qualitative themes: 1 Self-determination - Choice and control, individualisation, independence, and safety ; 2 Enhancing wellbeing opportunities - MSE created opportunities for social connection with others, influenced the room user’s behaviour and mood, and provided respite and a space to extend therapy; 3 Engagement in the MSE - Environmental factors, such as the room design, the role of the MSE staff, and implicit room rules, either facilitated or created challenges; 4 Accessibility - participants predominantly described external environmental barriers (such as the MSE being upstairs), rather than internal barriers (i.e., lack of time) to access. |

| First Author & Year | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Litwin et al (2023) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Insufficient illustrative quotations. |

| Malysheva et al (2020) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | CT | CT | School children recruited only represented those aged 14-15 years. No detail provided on recruitment or statistical analysis. |

| Wilkinson et al (2023) | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | No rationale given for using a mixed methods design, lack of synthesis of qualitative and quantitative methods, no explanation of divergence between quantitative and qualitative findings. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).