Methods

Colloidal PBCA nanoparticles were prepared by controlled emulsion polymerization of butyl cyanoacrylate, as described elsewhere [

9]. Briefly, the polymerization medium was prepared by dissolving 500 mg of Pluronic F68 and 400 mg of citric acid in 200 ml of distilled water. Then, 2 ml of butyl cyanoacrylate monomer was added dropwise to the medium under vigorous stirring at 600 rpm. Within the first 10 minutes, the emulsion turned milky white, and polymerization proceeded for six hours. The pH of the resulting dispersion was adjusted to 5.6 by adding 4 ml of 1M NaOH. Next, the polymerized dispersion was centrifuged at 14,500 rpm for 15 minutes and washed twice with double-distilled water. The resulting precipitate was dried under vacuum, yielding a fine white powder used for nanoparticle preparation.

For PBCA nanoparticle preparation, the precipitation medium was prepared with 20 mg of Pluronic F68 as a colloidal stabilizer and 20 mg of citric acid dissolved in 10 ml of 5% glucose solution. Then, 50–100 mg of pre-synthesized PBCA was dissolved in 5 ml of acetone and added dropwise to the nanoprecipitation medium under vigorous stirring at 600 rpm, allowing acetone to evaporate as the suspension was left in a fume hood for 5 hours. Residual acetone was removed by vacuum evaporation. Nanoparticle concentrations were determined gravimetrically by repeated centrifugation and washing of particles from an aliquot of the dispersion, followed by drying of the sediment to a constant mass in pre-weighed Eppendorf tubes in a vacuum desiccator. Water dispersions of PBCA nanoparticles with concentrations of 6–8 mg/ml were prepared, as well as PBCA nanoparticle solutions in chloroform with concentrations of 1.5 ± 0.2 mg/ml.

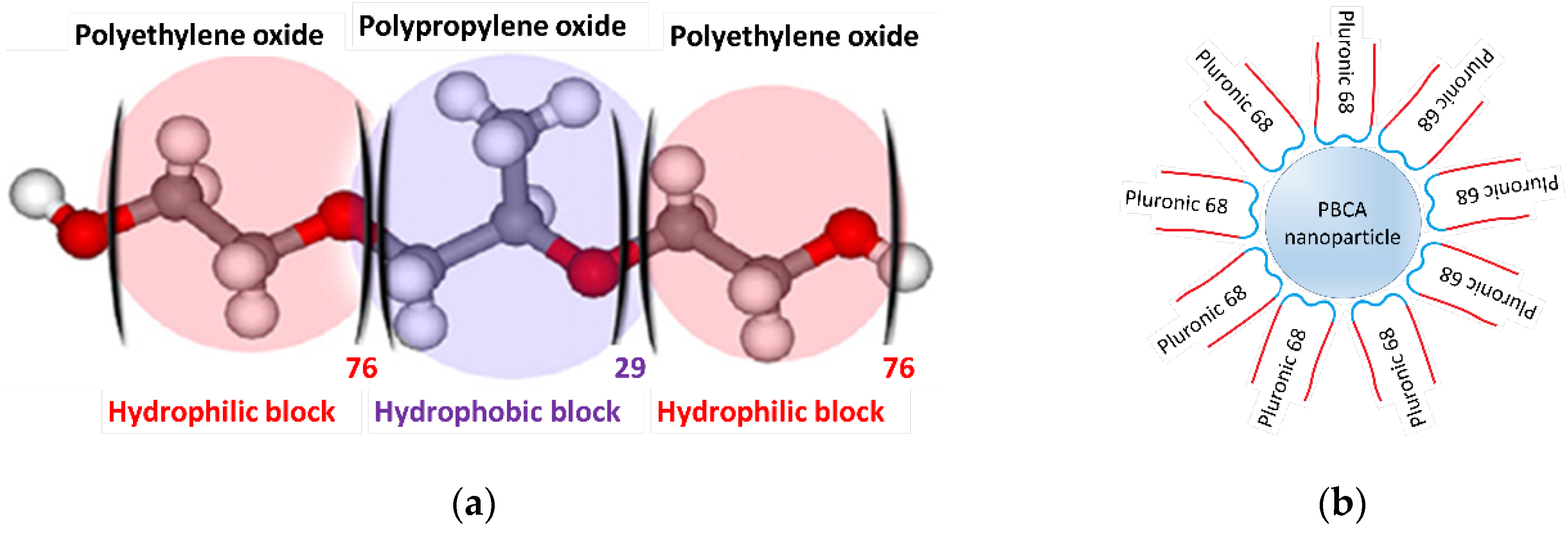

It should be noted that the prepared PBCA is soluble in acetone but not in water. Therefore, Pluronic F68, a triblock copolymer of poly(ethylene oxide)-poly(propylene oxide)-poly(ethylene oxide) (EO₇₆-PO₂₉-EO₇₆), was used as a colloidal stabilizer to stabilize the nanoparticles in the water phase. This polymer has a molecular weight of 8400 and consists of three parts: two hydrophilic EO blocks and a central hydrophobic PO block (

Figure 1a). This structure enables Pluronic molecules to adsorb on the surface of PBCA nanoparticles, creating a hydrophilic shell around them (

Figure 1b) that prevents aggregation.

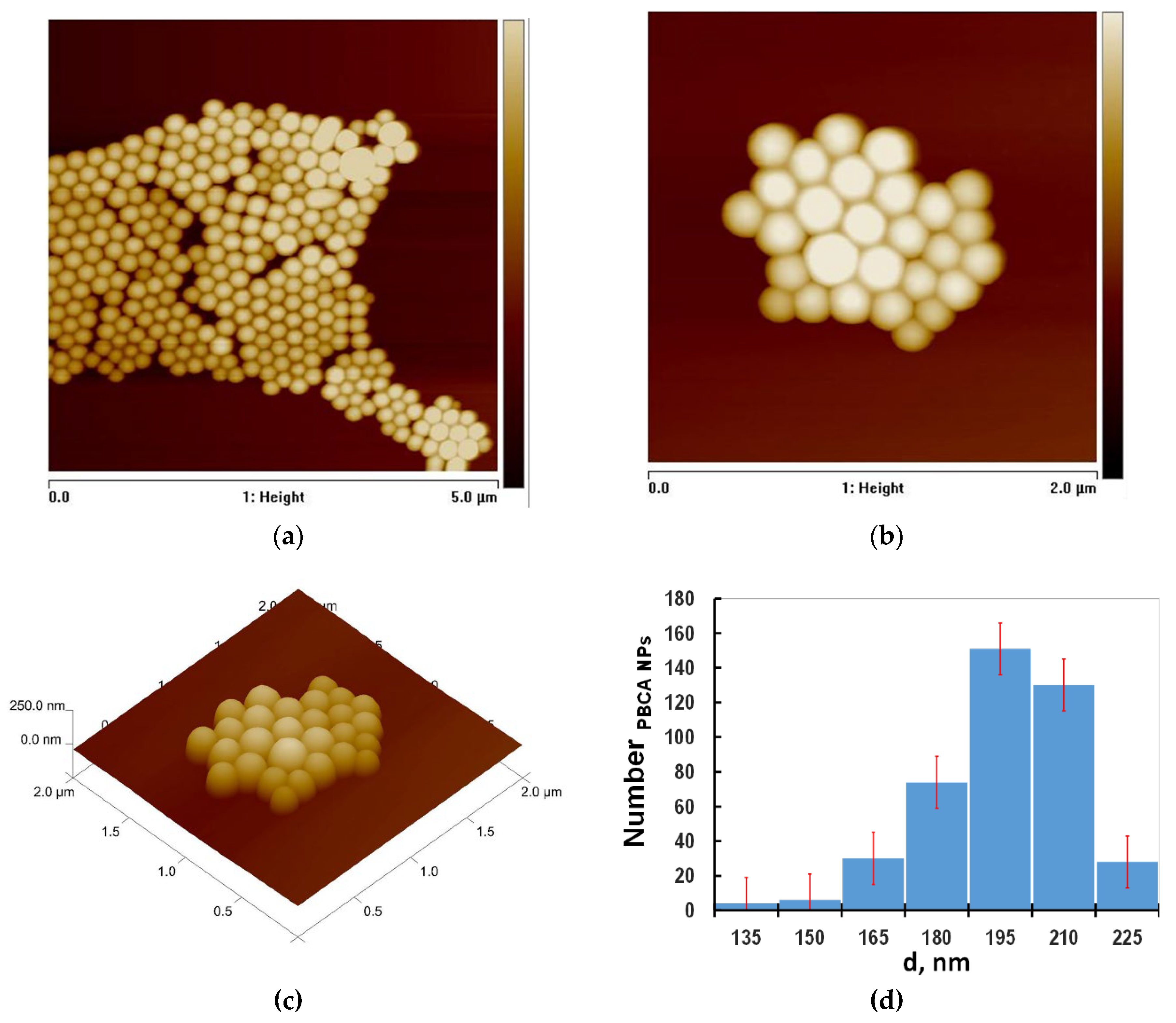

The PBCA nanoparticles were characterized by atomic force microscopy (AFM). Sample preparation for AFM imaging involved depositing a freshly synthesized PBCA nanoparticle solution onto a freshly cleaved mica surface before the addition of Pluronic F68. Freshly cleaved Grade V-4 Muscovite mica sheets (10 × 10 mm) from SPI Supplies (USA) were used for deposition of approximately 100 μL of nanoparticle solution. These mica sheets were also used in LB experiments. After a 10-minute incubation, samples were gently dried with nitrogen gas for 5 minutes.

AFM imaging was performed on a NanoScope MultiMode V system (Bruker Inc., Germany) in tapping mode in air at room temperature. The system uses a stationary probe oscillated vertically by a piezoelectric stack, while the sample, mounted on a metal puck magnetically attached to the scanner tube, is translated horizontally. The probe detects sample surface information through the deflection of the cantilever as it encounters the surface, revealing vertical height and other features of the deposited material. Silicon cantilevers (Tap 300 Al-G, Budget Sensors, Innovative Solutions Ltd, Bulgaria) with a 30 nm-thick aluminum reflex coating were used, with a spring constant range of 1.5–15 N/m and a resonance frequency of 150 ± 75 kHz. The tip radius was under 10 nm.

Before imaging, samples were thoroughly dried with N₂ gas. Scans were conducted at a scanning rate of 1 Hz, capturing images in both height and phase modes at 512 × 512-pixel resolution and saved in JPEG format. Multiple areas along the mica sheets were scanned, and all images were flattened using Nanoscope software (v.7.30). These imaging settings were consistently applied across all AFM experiments.

Figure 2 shows typical AFM images of PBCA nanoparticles deposited on the mica surface in 2D topography format, with a scanned area of 5 × 5 μm² and a z-scale of 300 nm (

Figure 2a), where the arrangement of the polymer nanoparticles in the X-Y plane is clearly distinguishable.

In the other images, the scanned area along the XY-plane was reduced to 2 × 2 μm², and the images were presented in both 2D (

Figure 2b) and 3D (

Figure 2c) formats. The analysis of nanoparticle size was performed through section analysis across individual nanoparticles, measuring their diameters while considering a well-known artifact in AFM metrology known as the convolution (rounding) effect. This effect arises from the interaction between the AFM tip and the surface, as well as the size of the tip's radius of curvature [

17]. The histogram for the size distribution and the average size of the nanoparticles derived from the section analysis is presented in

Figure 2d. The estimated diameter of the PBCA nanoparticles was d = 200 nm, consistent with reported results from scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements [

8].

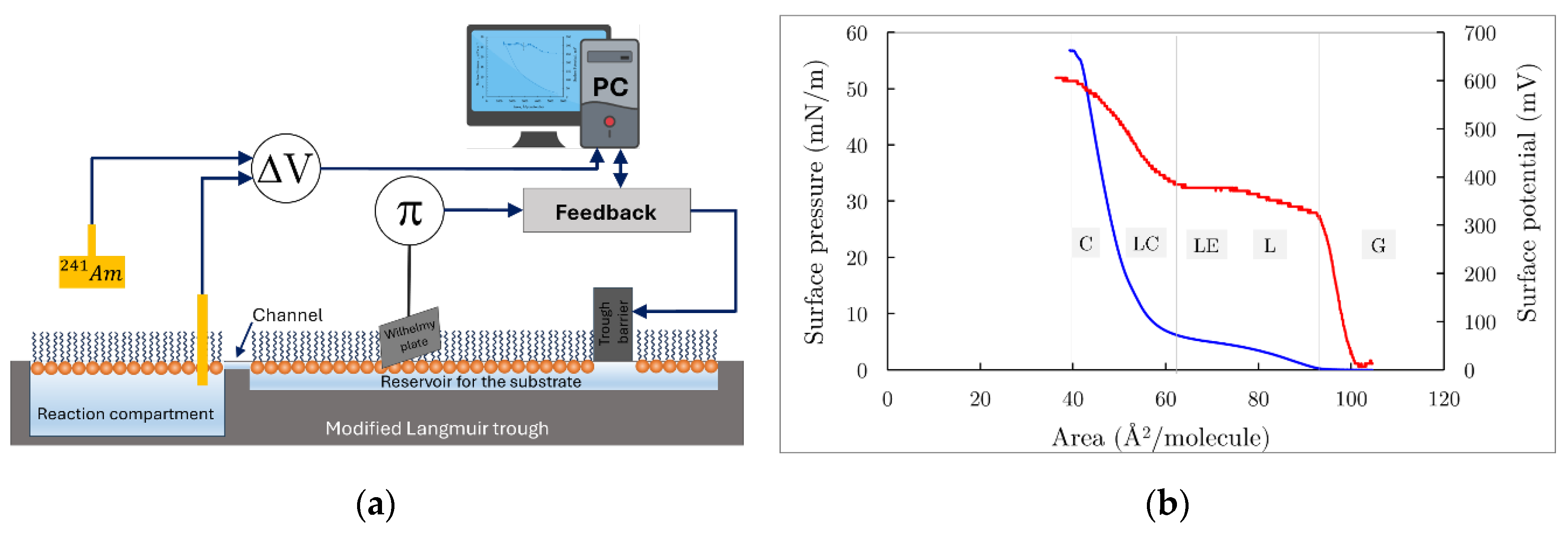

Phospholipid monolayers at the water-air interface are convenient and well-defined biological membrane models [

18]. They are formed after the spreading of phospholipids from their volatile organic solutions on a liquid surface in a Langmuir trough (

Figure 3a).

Due to the thermal motion of phospholipid molecules that is constrained within the plane of the phospholipid monolayer at the air/water interface and the difference in the surface tensions of the liquid phase and that of the phospholipid monolayer, a surface pressure (π) arises. This is an experimentally measurable quantity and the main characteristic of the thermodynamic state of the monolayer. Hence, using the Langmuir trough, equipped with movable barriers, by controlling the area of the monolayer one can obtain the dependence of the surface pressure (π) versus the area per one phospholipid molecule (), i.e. surface pressure/area isotherm.

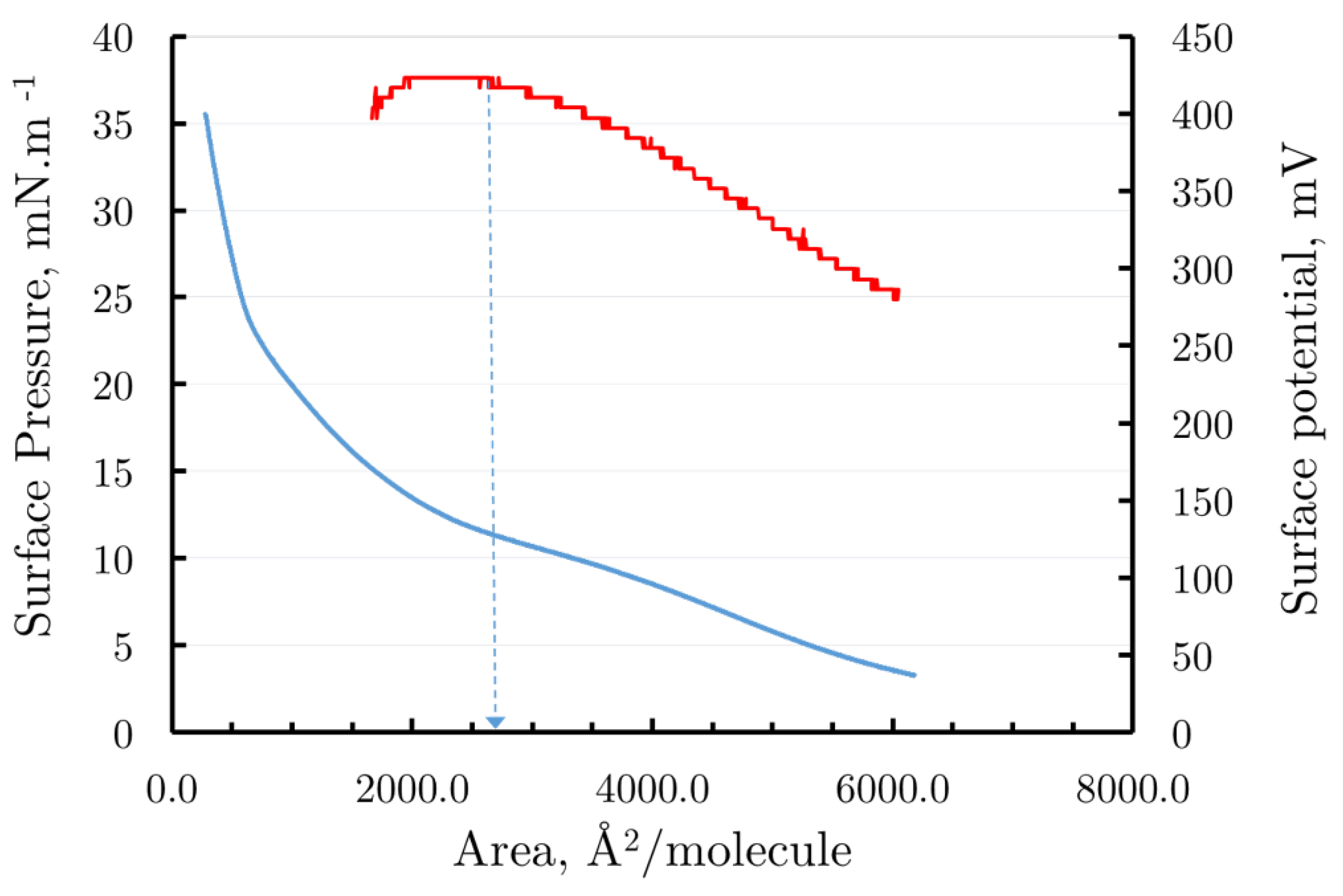

In

Figure 3b (blue curve), a typical DPPC isotherm is presented. At the largest areas per molecule, the monolayer exists in a molecular state where individual DPPC molecules are separated by distances too great for any force interactions among them to occur. This thermodynamic state is considered a 2D gas. Further compression of the monolayer leads to the appearance of different phases or states, which depend on surface concentration (or surface pressure), temperature, and molecular structure. It is now generally accepted that a DPPC monolayer can exist in four distinct pure phases below the critical temperature (~ 40 °C): gas (G), liquid expanded (LE), liquid condensed (LC), and solid or crystalline (S) phases (monolayer states) [

18]. From the π-A curve (

Figure 3b) under these conditions, the area per phospholipid molecule can be determined; for a DPPC monolayer, this area is 49 Ų.

On the other hand, at the air-water interface between the two phases, the dipole moments of the phospholipid molecules remain partially uncompensated, resulting in a potential difference known as the Volta potential. This potential is defined as the work required to transfer a unit charge from infinity to the interface and equals the difference between the potentials of the water substrate and the monomolecular layer spread at the air-water interface. The Volta potential is proportional to the effective dipole density (μ) for an uncharged monolayer and represents the main electrical characteristic of the monolayer. In a continuum approximation, the Helmholtz equation gives:

where ε is the dielectric constant (assuming it is unity), n corresponds to the number of molecules at the surface (or the surface concentration Γ), and

is the vertical component of the dipole moment of the molecules. Measuring ΔV when the area of the monolayer changes provides information about the change in the perpendicular component of the dipole moments of the phospholipid molecules, reflecting structural changes in the monolayer [

19]. In

Figure 3b (red curve), a typical surface potential versus area isotherm of the DPPC monolayer is also presented, where all states of the monolayer during compression are distinguishable, particularly the phase transition from G to L, which is undetectable on the surface pressure/area isotherm.

In this study, the isotherms of Pluronic F68 monolayers were measured. The monolayers were spread on a water subphase in a Langmuir film balance (KSV 2200, Finland) with a maximum available trough area of 476 cm². A Hamilton microsyringe was used to spread 10 μl of Pluronic F68 from a chloroform solution at the water interface. Both surface potential (ΔV) and surface pressure (Δπ) were simultaneously measured, as shown in

Figure 3a. For surface potential measurements, the ionization method was employed, which required a gold probe coated with an emitter of

241Am (approximately 750 μCi) positioned above the surface, and a reference calomel electrode, both connected to the KP511 electrometer (Kriona, Bulgaria). Real-time data acquisition was managed by a personal computer equipped with user-specific hardware and software.

After the monolayer was spread, surface pressure initially fluctuated around 0.1 mNm-1 and stabilized after approximately 10–15 minutes. The monolayer was then compressed at a constant velocity of Ub = 50 cm2min-1. Under these conditions, the isotherms were highly reproducible.

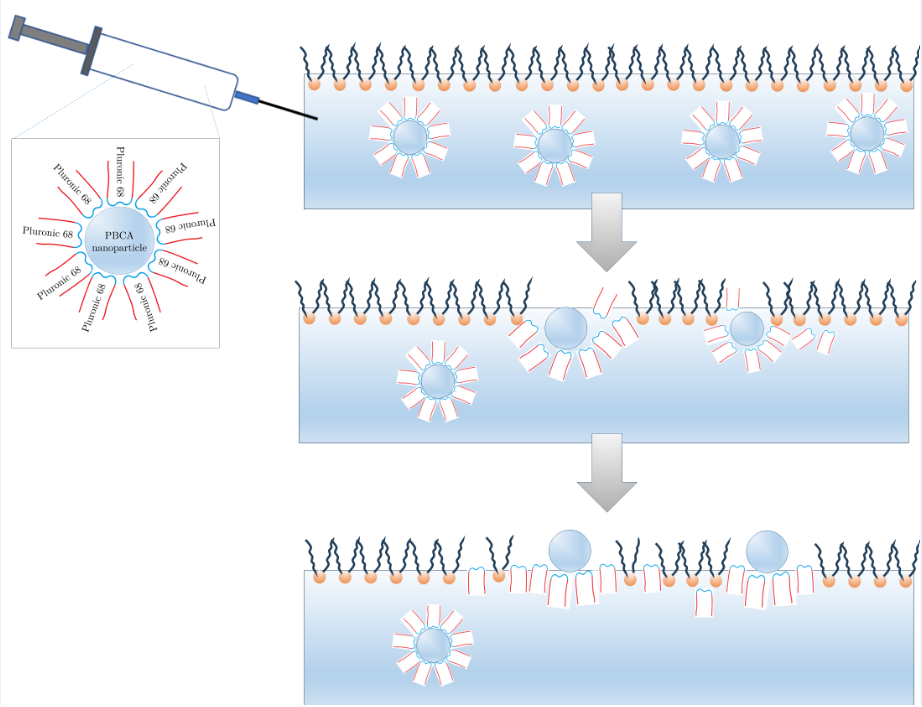

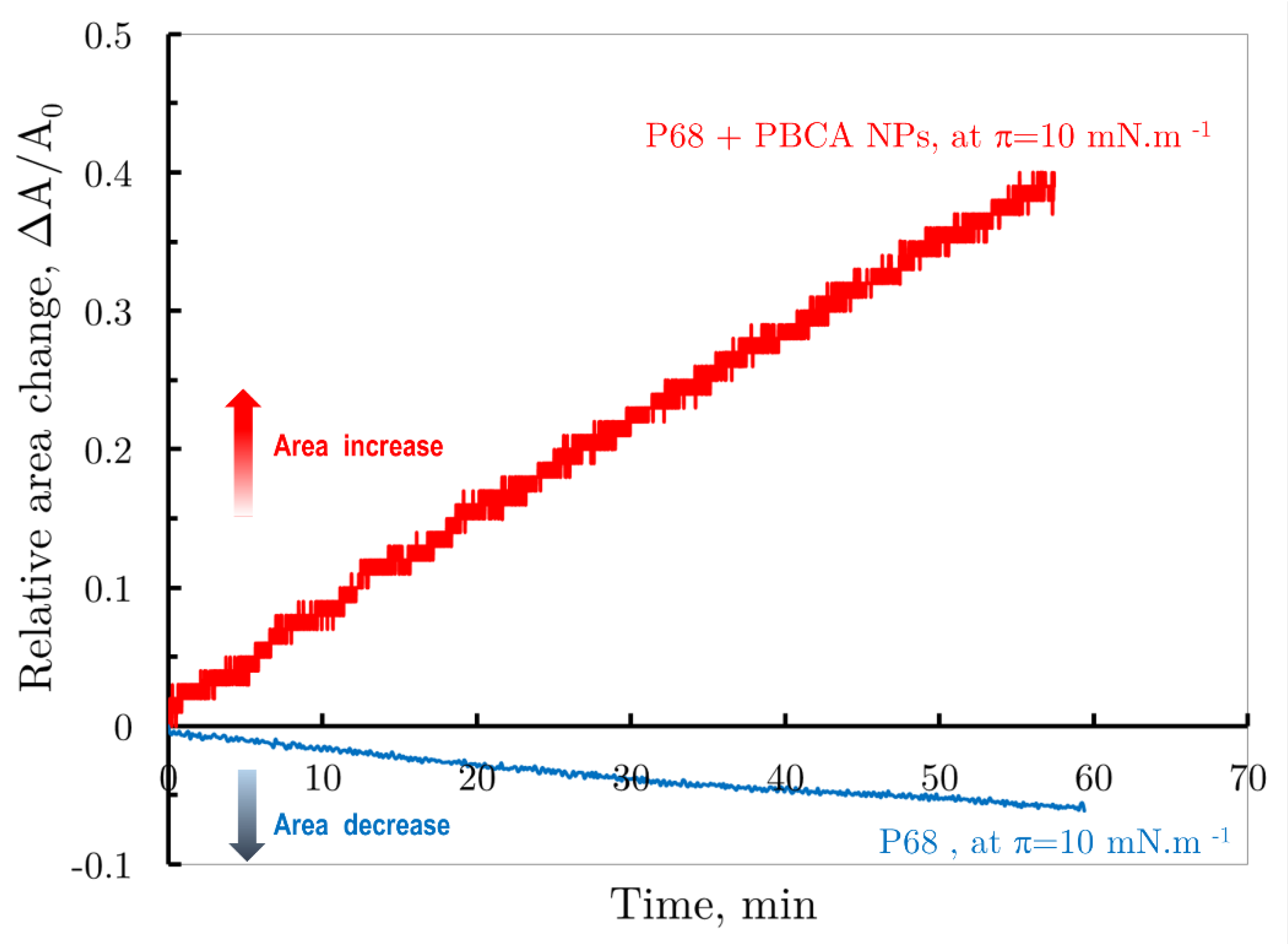

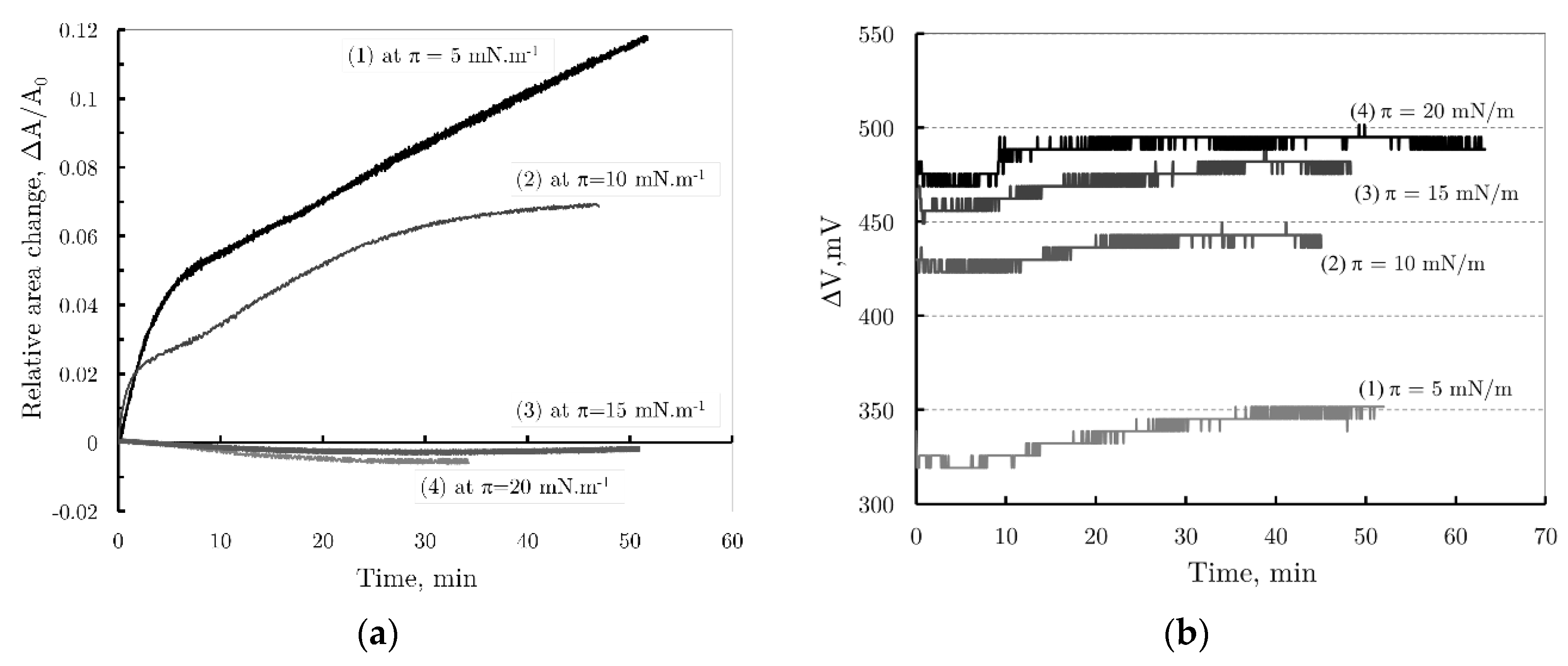

During the reorganization and possible penetration of PBCA nanoparticles into the DPPC monolayer, both the increase in surface area (ΔA) and the evolution of surface potential (ΔV) over time (t) were simultaneously measured at a constant surface pressure (π). A "zero-order" Langmuir trough, containing a reaction compartment with an area of 50 cm² connected to a reservoir compartment (area 260 cm²) by a 0.5 cm wide channel, was utilized (

Figure 3a).

After spreading over the maximum available area (A = 310 cm²), the DPPC monolayer was compressed at a constant velocity of Ub = 100 cm2min-1 to a set endpoint surface pressure, after which the barostatic mode was activated. Ten minutes later, 50 μL of PBCA nanoparticle dispersion was injected into the reaction compartment containing a 0.15 M NaCl solution. Due to the penetration of PBCA nanoparticles into the DPPC monolayer and their reorganization at the air/water interface, surface pressure increased, with the surface pressure barostat adjusting by barrier displacement, thereby altering the surface area (ΔA). The final concentration of PBCA in the reaction compartment was . The bulk in the reaction compartment was continuously stirred at 250 rpm using a magnetic rod, and the reservoir compartment’s aqueous subphase was also 0.15 M NaCl solution.

The monolayers were transferred from the air/water interface onto mica supports via Langmuir–Blodgett (LB) deposition. For this, the solid support was dipped vertically into the subphase and then moved upward through the monolayer. The mica plates were removed from the subphase approximately 50 minutes after the injection of the PBCA nanoparticles, at a transfer rate of 5 mm/min. Before AFM imaging, the LB film was thoroughly dried with a gentle nitrogen gas flow for about 10–15 minutes and then imaged as described above.