1. Introduction

FDML lasers have emerged as exceptionally attractive light sources given high scanning rate. Proposed as high-speed sources for optical coherence tomography (OCT) in 2006 [

1], they have rapidly garnered industry interest for the fast wavelength-scanning capabilities, becoming the preferred light sources in numerous biomedical imaging and measurement applications. Unlike conventional wavelength-scanning lasers, FDML lasers utilize a longer intracavity fiber delay line to extend the laser cavity. This design enables the laser cavity to store the entire scan signal, thereby circumventing the need for repeated laser buildup associated with spontaneous emission [

1]. Consequently, FDML lasers overcome the limitations of traditional wavelength-scanning lasers, which experience scanning speed constraints due to the buildup time of the new laser signal [

2]. Through this innovative architecture, FDML lasers have successfully elevated the scanning rate from tens of kHz to hundreds of kHz while achieving substantial enhancements in noise performance, coherence length, and output power.

FDML lasers are extensively utilized across numerous fields owing to high-speed, narrow-band, and highly phase-stable optical frequency scanning capabilities, along with an innovative mode-locking mechanism. They achieve unprecedented imaging rates for densely sampled volumetric datasets, significantly enhancing the visualization of tissue morphology [

3]. Initial in vivo experiments using FDML-based OCT systems in ophthalmology [

4] and cardiology [

5] have demonstrated excellent performance, providing the exceptional temporal resolution needed to observe complex dynamics. Furthermore, FDML lasers have proven to be efficient real-time measurement tools in high-speed spectroscopy, successfully measuring various gas parameters, including temperature, pressure, water concentration, and gas velocity [

6]. The integration of FDML lasers with microwave photonics has recently opened new avenues for microwave frequency measurements [

7] and high-resolution temperature sensing [

8]. These developments not only showcase the extensive range of applications of FDML lasers but also emphasize the considerable potential for future research and industrial applications.

With the deepening of FDML research, researchers have improved the performance of FDML lasers in many aspects. For instance, the scanning rate has been increased to MHz through buffering techniques [

9]. The broadest scanning range to date has been achieved by employing two semiconductor optical amplifiers (SOAs) in parallel with a wavelength division multiplexer [

10]. As a result of the improvements in the production and performance of FDML lasers, new advances have also been made in various fields, including OCT, spectral analysis, metrology, nonlinear microscopy, and microwave signal generation.

This review summarizes the performance metrics and recent advancements of FDML lasers, highlighting key future research directions. The paper is organized into three parts: the first part introduces the fundamental principles and main parameters of FDML lasers, the second part discusses their development across different application scenarios, and the third part elaborates on the further development of FDML lasers.

2. Theoretical Research of FDML Lasers

2.1. Principle of FDML Lasers

Frequency-swept laser sources typically consist of a broadband gain medium and a tunable bandpass filter. Each time the center frequency of the filter is adjusted, the laser must re-establish a stable mode of operation, which severely limits the performance of high-speed frequency-swept lasers and necessitates trade-offs among sweep speed, linewidth, output power, and tuning range [

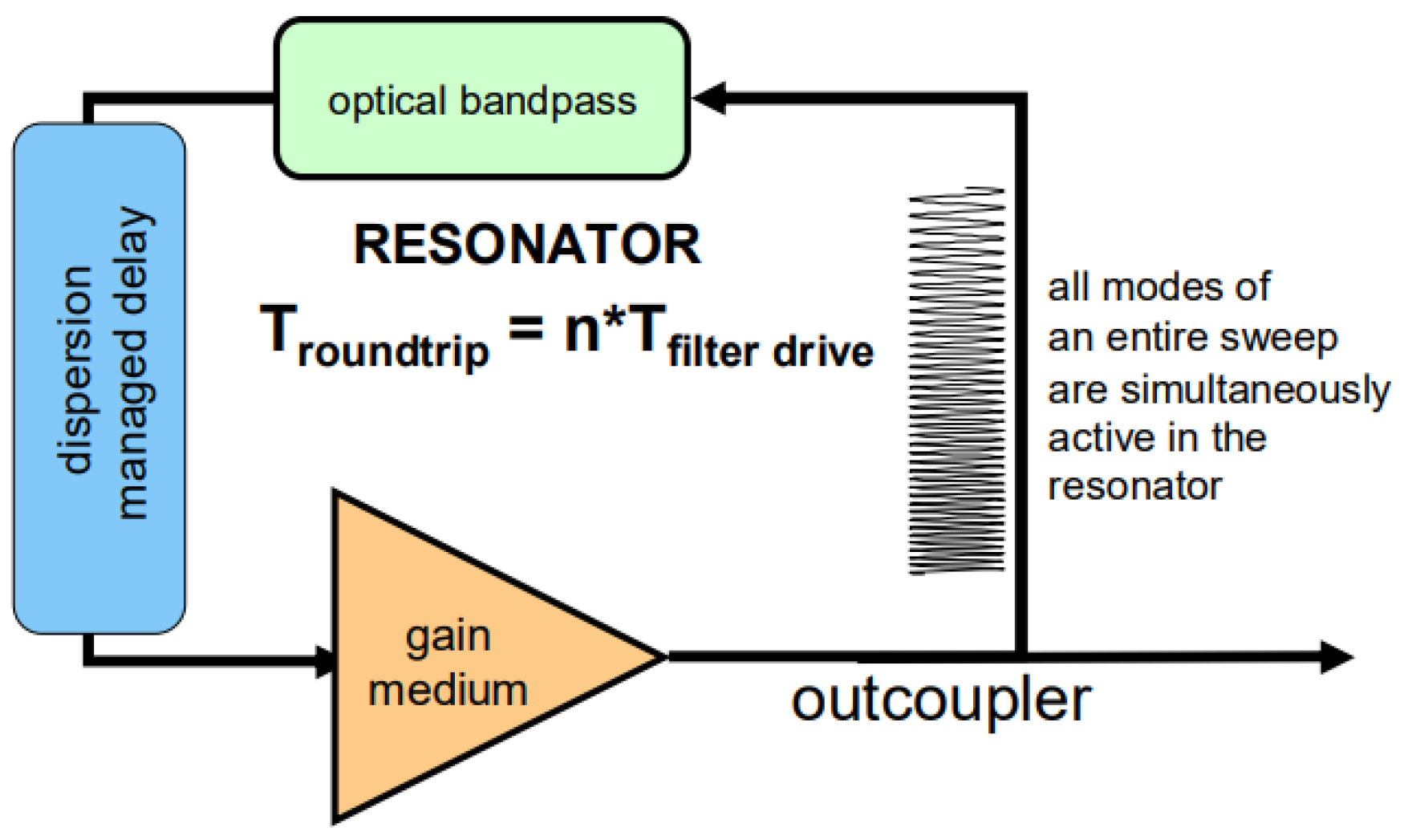

11]. This challenge is addressed in FDML lasers. In addition to the conventional gain medium and tunable bandpass filter, FDML lasers incorporate a section of dispersion-managed fiber with varying dispersion characteristics and lengths, serving as a delay line.

Figure 1 shows the schematic of a typical FDML laser. This design achieves low dispersion across the entire operating wavelength range and enhances the coherence length of the scanned signal, effectively increasing the laser ring cavity time.

Tunable optical bandpass filters are periodically driven with a period that matches the cavity or its harmonic round-trip time. This approach establishes a fixed phase relationship between the longitudinal cavity modes, allowing the transient electric field at the optical bandpass filter to contain only those frequency components that align with the filter’s transient transmission. All other frequency components destructively interfere [

1]. When the transmission window of an optical bandpass filter is tuned to a specific optical frequency, light from that frequency scan can propagate through the cavity and return to the filter. Consequently, the entire frequency scan is stored in the dispersion-managed delay line within the laser cavity, eliminating the need for laser light to be generated by spontaneous emission.

2.2. Parameters of FDML Lasers

FDML lasers are capable of generating optical pulses with extremely short pulse widths and high repetition rates, making them invaluable for scientific research and various applications. The parametric specifications of FDML lasers are crucial for evaluating the performance and suitability for FDML-based applications. Key parameters include the following:

Scan rate: It is defined as the number of wavelength scans performed by the laser per unit time, which directly dictates the imaging speed of a swept-source OCT (SS-OCT) system. The primary advantage of FDML lasers lies in the ability to store the entire scanning signal in long fiber delays, effectively preventing the accumulation of spontaneously emitted signals. Thus, the scan rate is theoretically constrained only by the speed of the tunable filter.

Tuning range: It represents the variable extent of the laser’s output wavelength. The width of this range significantly influences the system’s spectral resolution and detection depth. It is closely related to the axial resolution of OCT and the precision of optical measurements.

Output power: It refers to the laser’s power output, which critically influences the system’s sensitivity and image quality. High output power allows substantial reflected light from the sample to be captured, resulting in considerably clear images and improved sensitivity.

Coherence length: It defines how far the laser can propagate while maintaining coherence, directly influencing the imaging depth of SS-OCT. However, current FDML lasers often produce output signals with dense, disordered high-frequency fluctuations, which degrade signal quality and reduce coherence [

12]. Therefore, determining how to achieve a stable output without high-frequency fluctuations is one of the research difficulties for the future of FDML lasers.

3. Application Progress of FDML Lasers

FDML technology has already demonstrated its significant potential and application value across various fields. It has been extensively utilized in fast OCT systems, achieving notable advancements in ophthalmology, intravascular OCT (IV-OCT), cardiac OCT, and surgical microscope. In addition, FDML lasers are employed in numerous applications related to spectral analysis, measurements, microwave signal generation, and nonlinear microscopy. These applications are detailed below.

3.1. OCT

The use of FDML technology enables unprecedented high-quality OCT imaging results. Compared with conventional low-speed systems, FDML technology significantly increases imaging speed, which means not only a higher update rate but also the ability to acquire richer 3D information. From ophthalmology to IV-OCT, cardiac OCT, and surgical microscope, the range of applications for FDML technology continues to expand. In recent years, researchers have paid particular attention to applications in ophthalmology and surgical microscope. These studies aim to reduce surgical risk and advance minimally invasive surgical techniques.

3.1.1. Ophthalmology

In ophthalmology, the advent of FDML has transformed OCT technology into a vital tool for diagnosing and monitoring eye diseases. The ability of OCT based on FDML lasers to provide high-resolution depth imaging of ocular structures is a considerable advantage for ophthalmologists. In ophthalmic OCT, researchers have improved the performance indicators of FDML, as detailed in

Table 1.

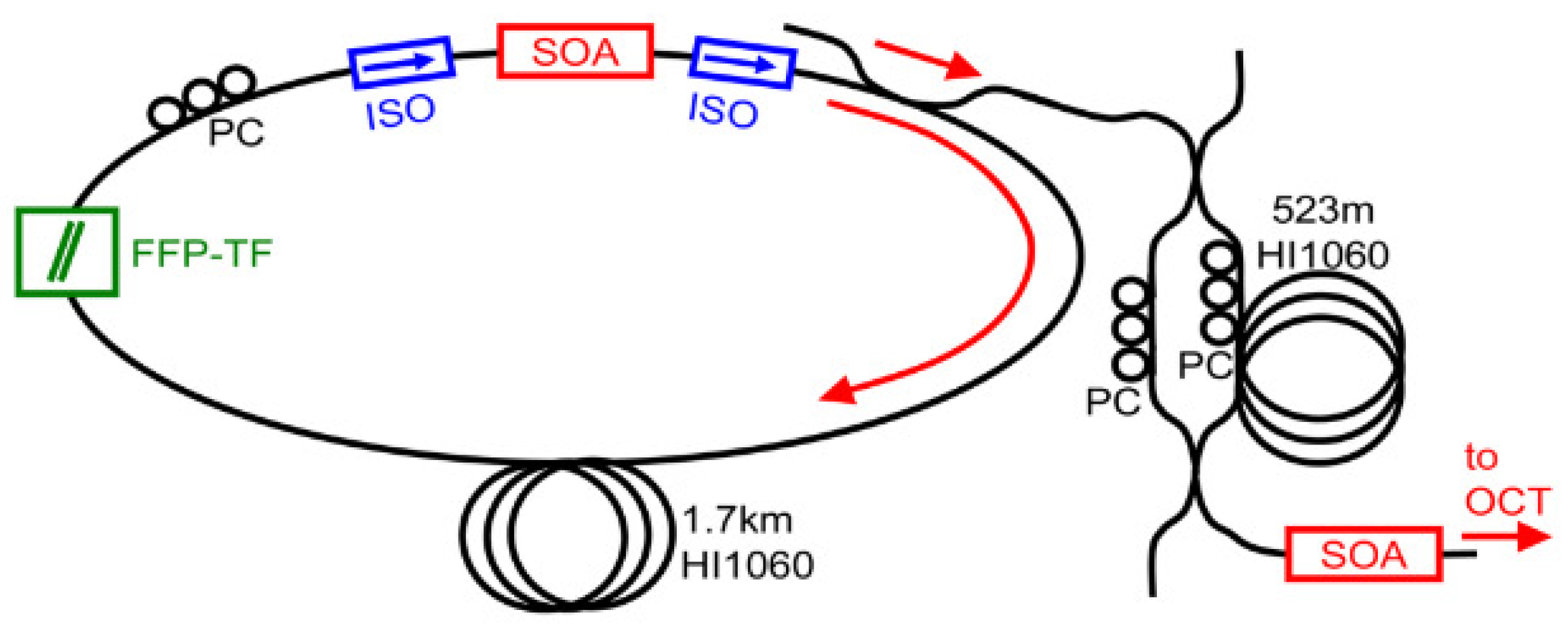

A buffering technique is employed following the use of an FDML laser, as shown in

Figure 2, in which multiple scans are time-division-multiplexed to enhance the scan rate, yielding unidirectional scans at multiple times the filter drive frequency. Retinal imaging has been conducted using a pair of detector mirrors and relay optics, achieving retinal OCT imaging at 236,000 axial scans (A-scans) per second [

13]. A combination of SOAs and ytterbium (Yb)-doped fiber amplifiers in the FDML laser provides over 50 mW of output power [

14]. Buffer stages, either 4× or 8×, further increase the scan rate to 684 kHz and 1.8 MHz, respectively. Ultrawide-field data consisting of 1900×1900 A-scans with approximately 70° angle of view were acquired within only 3 and 6s, respectively. The axial resolution in tissue is 12 and 19

.

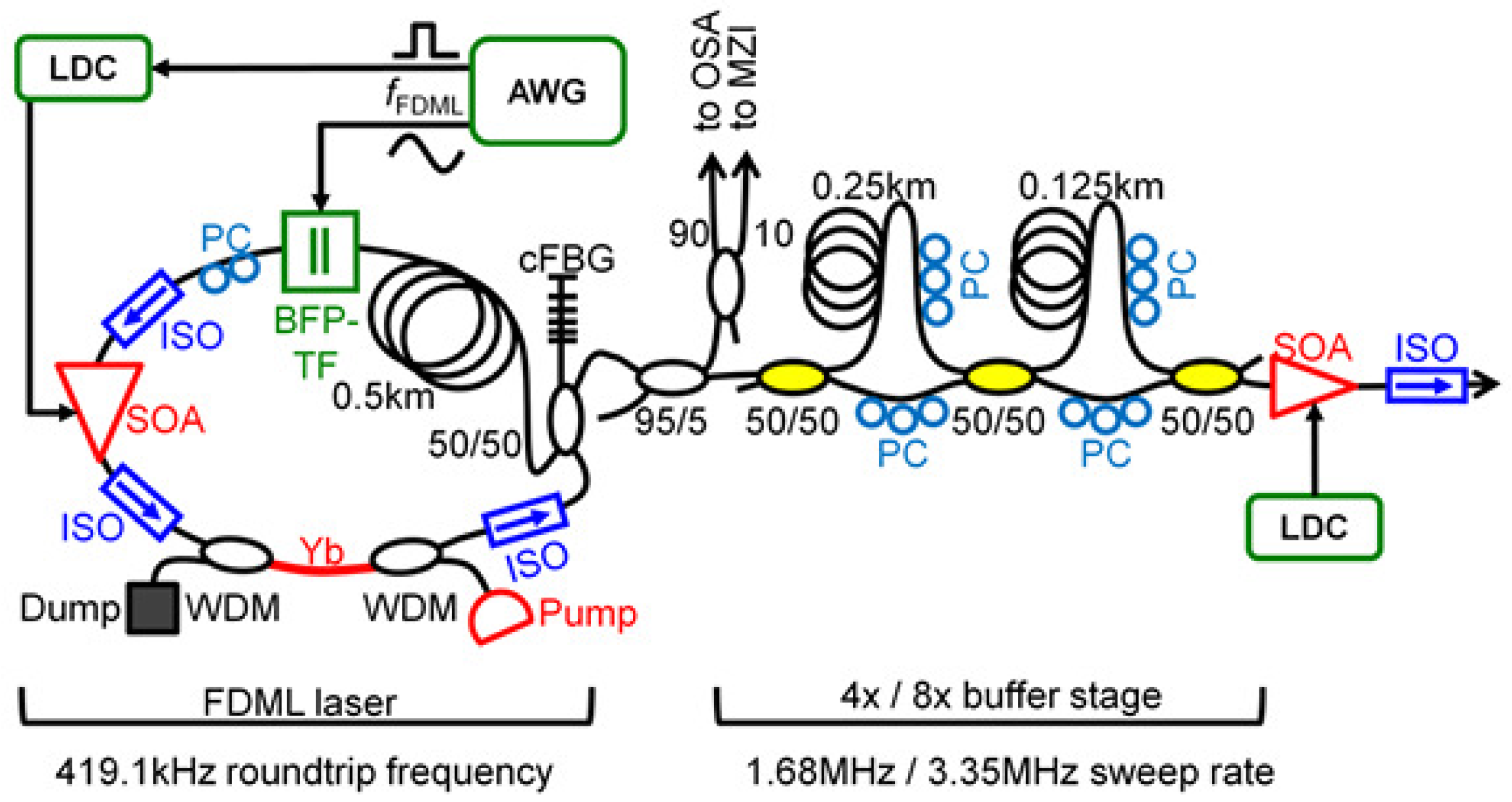

In 2013, Klein et al. improved upon the work in [

14] by using a Fabry–Pérot tunable filter, significantly enhancing the sweep rate and stabilizing laser operation. Intracavity dispersion was compensated by a chirped fiber Bragg grating (CFBG), which increased the coherence length of the FDML laser. The improved system is shown in

Figure 3. This configuration allowed alignment and averaging of 24 datasets at an axial line(A-line) rate of 1.68 MHz, ultra-dense transverse sampling at a rate of 3.35 MHz, and dual-beam imaging on the retina with two laser spots, achieving an effective line rate of 6.7 MHz [

9].

Kolb and colleagues used a buffered FDML laser similar to that in [

9] but without the intracavity Yb amplifier, achieving an effective line rate of 1.68 MHz. This system employed three different sample arm configurations, demonstrating for the first time single-volume ultrawide-field imaging with an field of view (FOV) of up to 100°. It also achieved 85° single-volume OCT imaging and 100° imaging by stitching together five 60° images, representing the widest FOV OCT image with a dense sampling pattern to date [

15]. For improving the axial resolution of the MHz-OCT system while maintaining a high imaging speed, the CFBG, SOA, and Fabry–Pérot filters used for dispersion compensation were improved on the basis of the buffered FDML OCT structure proposed in [

9]. A spectral bandwidth of 120 nm was achieved at an A-scan rate of 1.67 MHz, even 143 nm at an A-scan rate of 834 kHz [

16].

Table 1.

Improvement in corresponding indicators of FDML

Table 1.

Improvement in corresponding indicators of FDML

| |

Improvement |

Indicator changes |

| Sweep rate |

8× buffering [14] |

1.37 MHz |

| |

Using a bulk Fabry–Pérot tunable

filter, 8× buffering [9] |

419 kHz repetition rate

increased to 3.35 MHz |

| Sweep range |

Novel grating with a reflectivity of

50%-70%, a bandwidth of 200nm,

and novel SOA with a gain

bandwidth of 110 nm [16] |

143 nm (without buffering)

120 nm (4× buffering) |

| Output power |

A combination of SOA

and Yb fiber amplifiers [14] |

Over 50 mW of output power |

| Coherence length |

CFBG [9] |

Improved coherence length

of FDML lasers |

Objective optical assessment of photoreceptor function may facilitate the early diagnosis of retinal diseases. As shown in

Figure 4, Azimipour et al. described an adaptive optics (AO)-OCT system. By leveraging the 3D cellular resolution of AO-OCT and the speed of the FDML laser, this system enables the visualization of cone photoreceptors in 3D and characterizes morphological changes in individual cone cells induced by pulsed bleaching flashes [

17]. Moreover, they proposed a system that integrates AO with scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO) and OCT imaging [

18]. The FDML laser’s 1.6 MHz scan rate permits SLO and OCT to utilize the same scanner for in vivo retinal imaging. AO provides diffraction-limited cellular resolution for both imaging modalities, enhancing the overall quality of retinal assessment.

Torzicky et al. proposed the integration of polarization-sensitive OCT (PS-OCT) with an FDML laser featuring active spectral shaping. This innovative laser, as depicted in

Figure 5, allows for forward and backward scanning, effectively doubling the imaging speed without the need for buffering [

19]. The dual-channel system simultaneously acquires data in two orthogonal polarization states during each A-scan. As a result, the system achieves high axial resolution and deep penetration into the choroid and sclera. It demonstrates the capability to rapidly collect large 3D datasets while producing high-resolution 2D images.

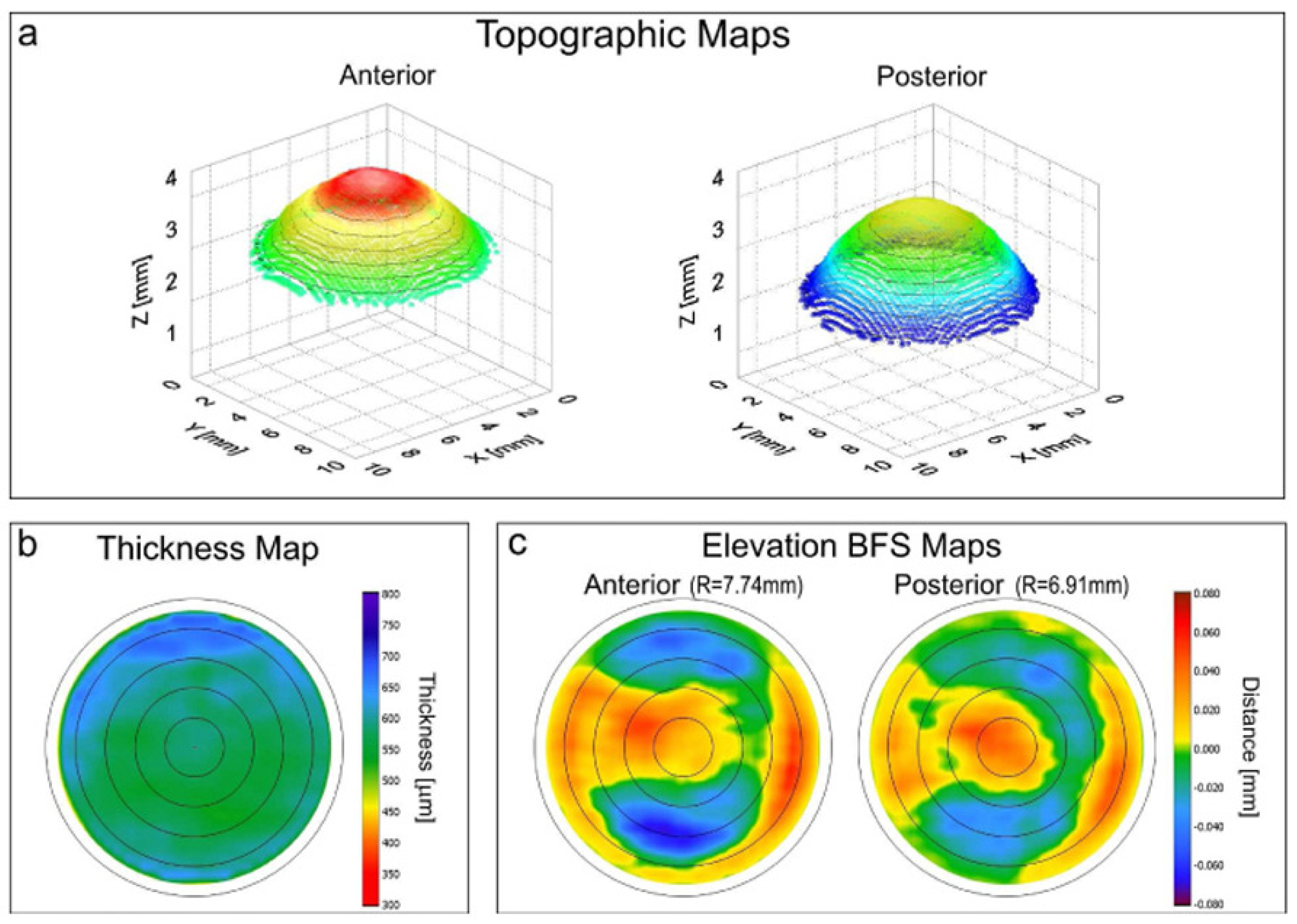

High-speed Fourier domain OCT utilizing a 1310 nm FDML laser has demonstrated effective application in imaging the human anterior segment [

20]. This system achieves an effective axial scan rate of 200 kHz, enabling 3D imaging of the anterior segment while significantly reducing motion artifacts, as shown in

Figure 6. Karnowski was the first to employ high-speed SS-OCT for quantitative corneal analysis [

21]. Through adjusting the Fabry–Pérot filter drive frequency and scanning range, an axial resolution of 20

and a tissue imaging depth of 9 mm were attained, facilitating the assessment of the corneal surface and the iris. The 108,000 lines per second high-speed OCT device allows for rapid 3D imaging of the anterior segment in less than a quarter of a second, thereby minimizing the effect of motion artifacts on the final image and subsequent morphometric analysis. The combination of a dispersion-compensated FDML laser and a 4× buffer stage OCT system ensures excellent roll-off performance and a high imaging speed of 1.6 MHz, making it suitable for comprehensive imaging of the entire anterior segment of the human eye [

22]. Likewise, Yao et al. utilized an FDML laser with a 4× buffer stage to achieve an effective line rate of 1.66 MHz, successfully imaging Schlemm’s canal using an achromatic lens designed for anterior segment imaging [

23].

3.1.2. IV-OCT

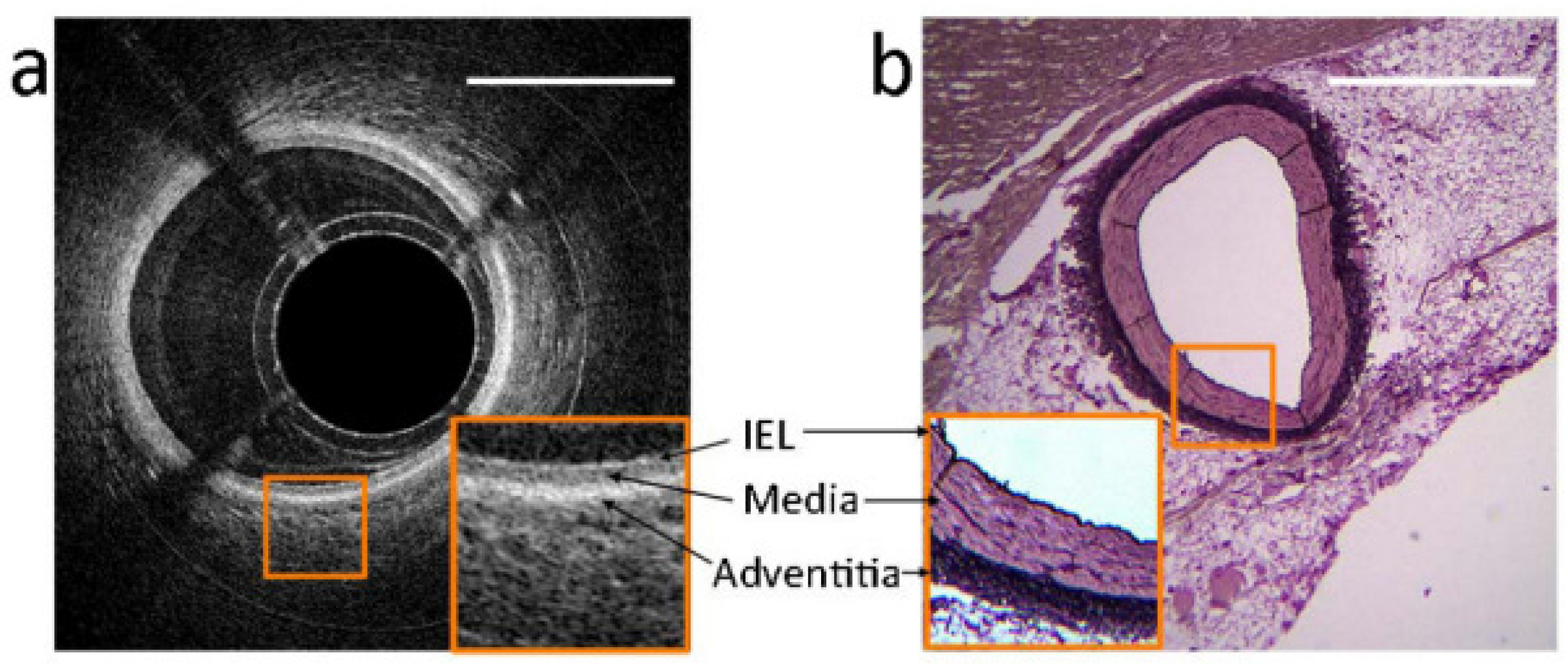

IV-OCT is a vital technology for diagnosing and studying coronary artery disease, offering exceptional high-resolution imaging capabilities. This technique provides a detailed view of the microscopic features of coronary arteries without disturbing blood flow, thereby minimizing motion artifacts crucial for accurate vascular health assessment. An OCT system employing a fast micromotor catheter and an FDML laser, operating at a depth scan rate of 1.6 MHz, enables intravascular imaging at a frame rate of 3.2 kHz. This system can acquire a fully sampled 3D dataset of coronary arteries in less than 1s [

24]. Wang et al. introduced a “heartbeat OCT” imaging system that integrates a fast FDML laser, rapid pullback, and a micromotor-driven catheter to examine coronary arteries within a single cardiac cycle [

25]. The buffer-class FDML laser increased the fundamental scan rate by a factor of eight, achieving an in vitro imaging speed of 5600 fps at a scan rate of 2.88 MHz and enabling the first in vivo imaging at 4000 fps. The in vivo imaging is shown in

Figure 7(a). In 2019, they demonstrated MHz intravascular Doppler OCT using a 1.5 MHz, 4× buffering FDML laser and a newly developed motorized catheter [

26]. Doppler images were reconstructed by calculating the phase shift between adjacent A-lines. A 3D Doppler OCT dataset containing morphology and Doppler information of the entire coronary artery could be acquired with a single pullback, which was the first in vitro 3D intravascular Doppler imaging.

3.1.3. Cardiac OCT

In cardiac imaging, conventional OCT techniques encounter several challenges, particularly due to the high frequency of heartbeats, which complicates the direct capture of cardiac dynamics in temporal and spatial domains. Nevertheless, advancements in technology, specifically the application of OCT using FDML lasers, have effectively addressed these issues. The high scanning rate and sensitivity of FDML lasers enable the detection of minute changes in heartbeats, which are essential for observing the complex morphodynamics of cardiac contraction.

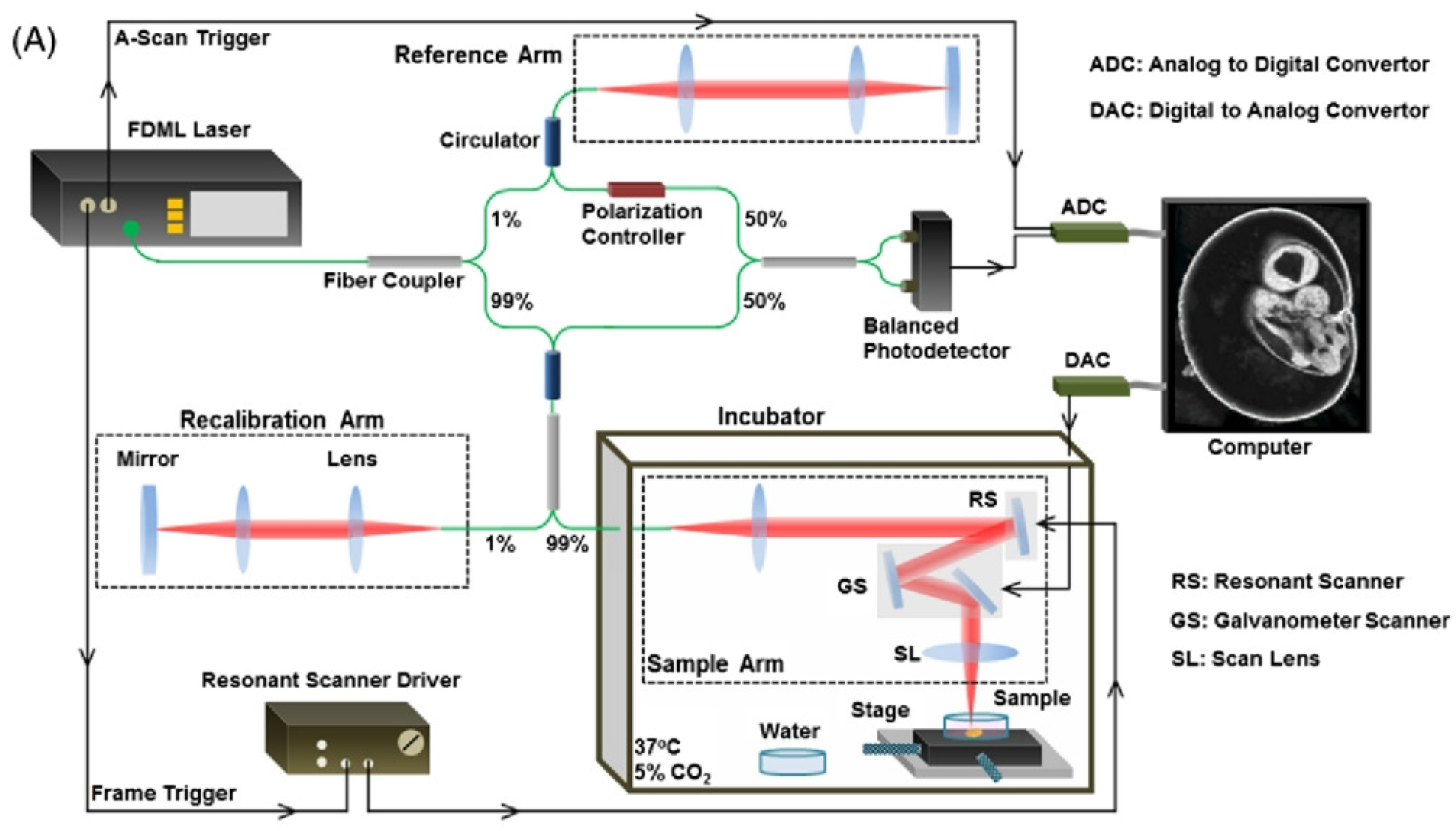

An OCT system utilizing a buffered FDML laser can achieve ultrafast, noninvasive imaging of embryonic quail hearts at a rate of 100,000 axial scans per second [

5]. For a further enhanced imaging speed, a resonance scanner was integrated into the sample arm, along with a dual orthogonal mirror oscillating scanner,as shown in

Figure 8 [

27]. This setup achieved large-field 3D OCT imaging and direct 4D imaging at a volume rate of approximately 43 Hz. This ultrafast OCT imaging provided sufficient spatial resolution to visualize embryonic cardiac structures.

Fu et al. presented a fiber-optic catheter-based PS-OCT system that acquires intensity and phase-delayed images of biological tissues, including the myocardium [

28]. This system employs a polarization-sensitive SOA operating at saturation to convert the output light of an FDML laser into a line-polarized state. This passive multiplexing of alternating polarization states eliminates the need for active components to be synchronized with A-scan data acquisition. It is a simple way to implement all-fiber PS-OCT using an FDML laser. The system effectively captures intensity and phase-delayed images of highly birefringent materials, in vivo human skin, and untreated and thermally ablated isolated porcine myocardium. In vivo images of the heart wall could also be obtained to aid in the treatment of arrhythmias by radiofrequency ablation [

28].

3.1.4. Surgical Microscope

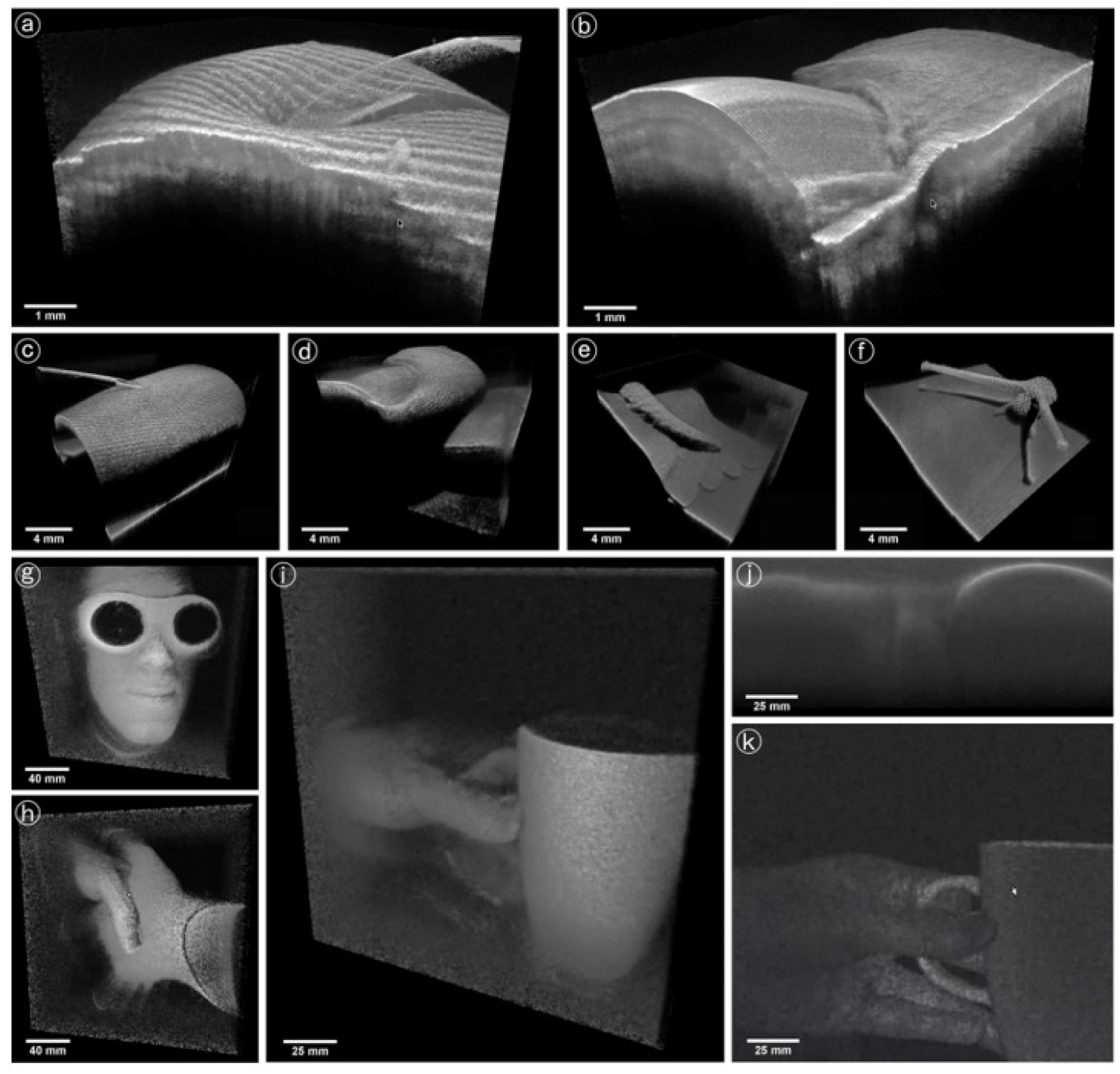

With advancements in FDML technology, the advent of real-time 4D-OCT technology has revolutionized surgical microscope. This technology offers sufficient volume size and high update frequency, enabling surgeons to monitor tissue structure changes in real time during procedures, which significantly enhances safety and efficacy. The integration of fast OCT with rapid computing facilitates real-time visualization of 4D-OCT images [

29]. The FDML cavity incorporates a dual-fiber Bragg grating dispersion compensation module operating at the fifth harmonic frequency of 402 kHz. With 8× buffer stages, the scan rate is increased to 3.2 MHz. Two high-speed digitizers operating in interleaved mode, along with a dual GPU card and dedicated processing software, enable efficient data processing and visualization. This system allows for OCT imaging with a real-time display rate exceeding 1 GVoxel/s, facilitating the acquisition, processing, and 3D visualization of volumes with either 320×320×400 available voxels at a frame rate of 26 Hz or 320×160×400 available voxels at 51 Hz [

29].

For accommodating the differing demands of real-time and non-real-time imaging, two buffer configurations based on the buffered FDML OCT system proposed in previous research [

9] were implemented to achieve varying A-scan rates. The system supports non-real-time retinal imaging at rates of up to 191 V/s and enables real-time retinal volumetric OCT imaging at 1.58 GVoxel/s, with a volume size of 330×330×595 usable voxels and an impressive update rate of 24.2 Hz [

30].

Göb et al. introduced a system that implements a 3D spectral scaling function within real-time 4D-OCT imaging [

31]. The light output from the FDML is amplified by an 8× buffer and a boosted SOA, which then feeds into the OCT system for real-time imaging. The online recalibration procedure is executed by capturing the recalibration signal at the turning point of the fast axis scanner during the OCT raster scan’s dead time. This approach allows for the OCT signal to be resampled at every frame during real-time processing of 3D-rendered OCT images, synchronizing adjustments of the imaging area and lateral FOV for 3D scaling. As shown in

Figure 9, the system can acquire OCT datasets with various resolution modalities, and imaging ranges of up to 10 cm at real-time update rates exceeding 1 GVoxel/s.

OCT, while renowned for its medical applications, also holds significant promise in nonmedical fields. Adler et al. introduced an active contrast agent detection technique utilizing photothermal modulation for high-speed OCT imaging [

32]. This system employs a double-buffered FDML laser, which allows high contrast to be observed between models with and without nanoparticles. The future integration of molecularly targeted nanoshell contrast agents with photothermally modulated OCT could facilitate highly sensitive and specific detection of diseases, such as cancer. FDML-based 3D-OCT systems are particularly promising for art conservation given ultrahigh imaging speed and extensive depth range. This technology enhances the visualization of microstructural features in base materials and can identify unique aspects of 3D punch contours that are often missed in high-resolution photography [

33]. Wang et al. developed a miniaturized, low-cost, monolithic silicon photonic integrated SS-OCT coherent receiver using an FDML laser [

34]. This receiver features dual-polarization, dual-balance detection, as well as in-phase and quadrature detection, enabling full-range OCT and PS-OCT.

As technology advances, OCT is expected to become increasingly valuable in nonmedical applications, leveraging its high-resolution, noncontact, and nondestructive detection capabilities to become an indispensable tool across various fields.

3.2. Spectral Analysis

3.2.1. Scattering Spectroscopy

FDML lasers have emerged as a crucial tool for measurements in the broadband Raman jump energy range. Karpf et al. utilized continuous and repetitive wavelength sweeping to generate broadband, high-resolution excited Raman spectra through a novel time-encoded (TICO) concept [

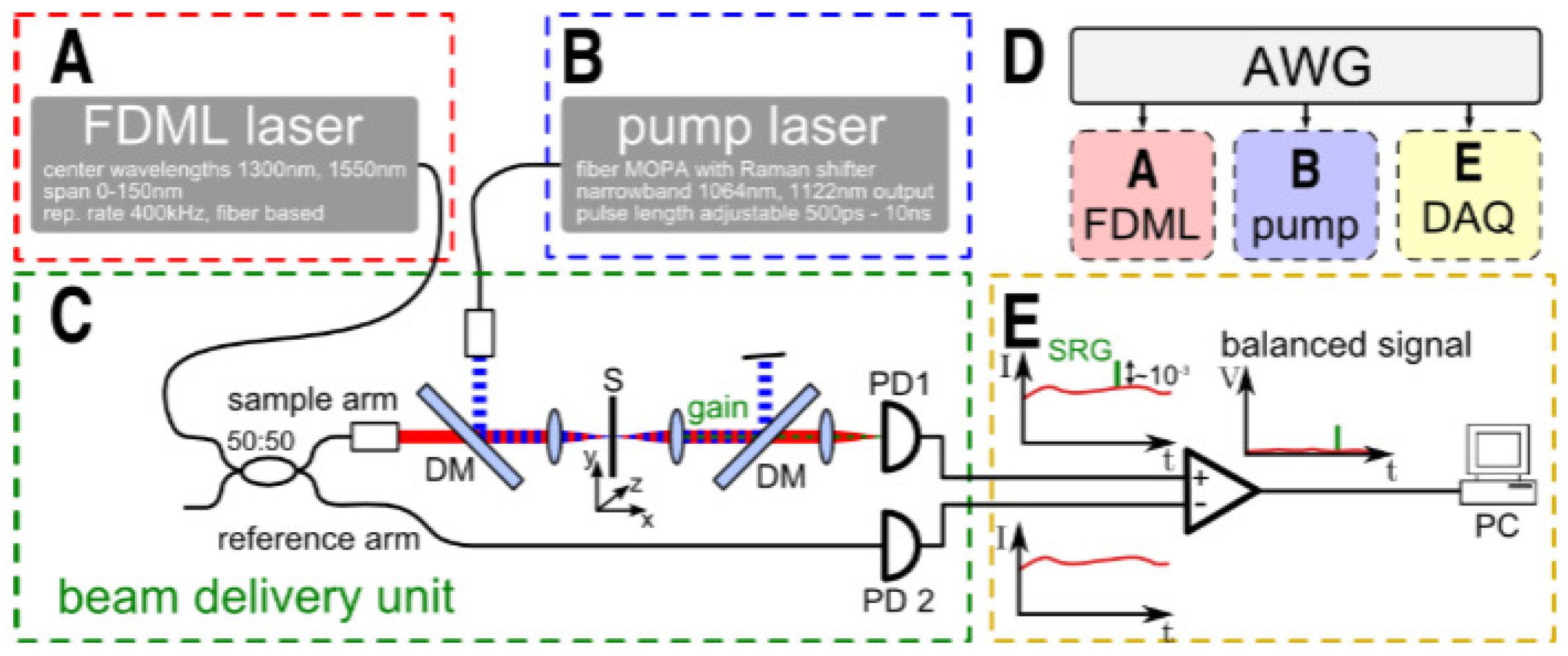

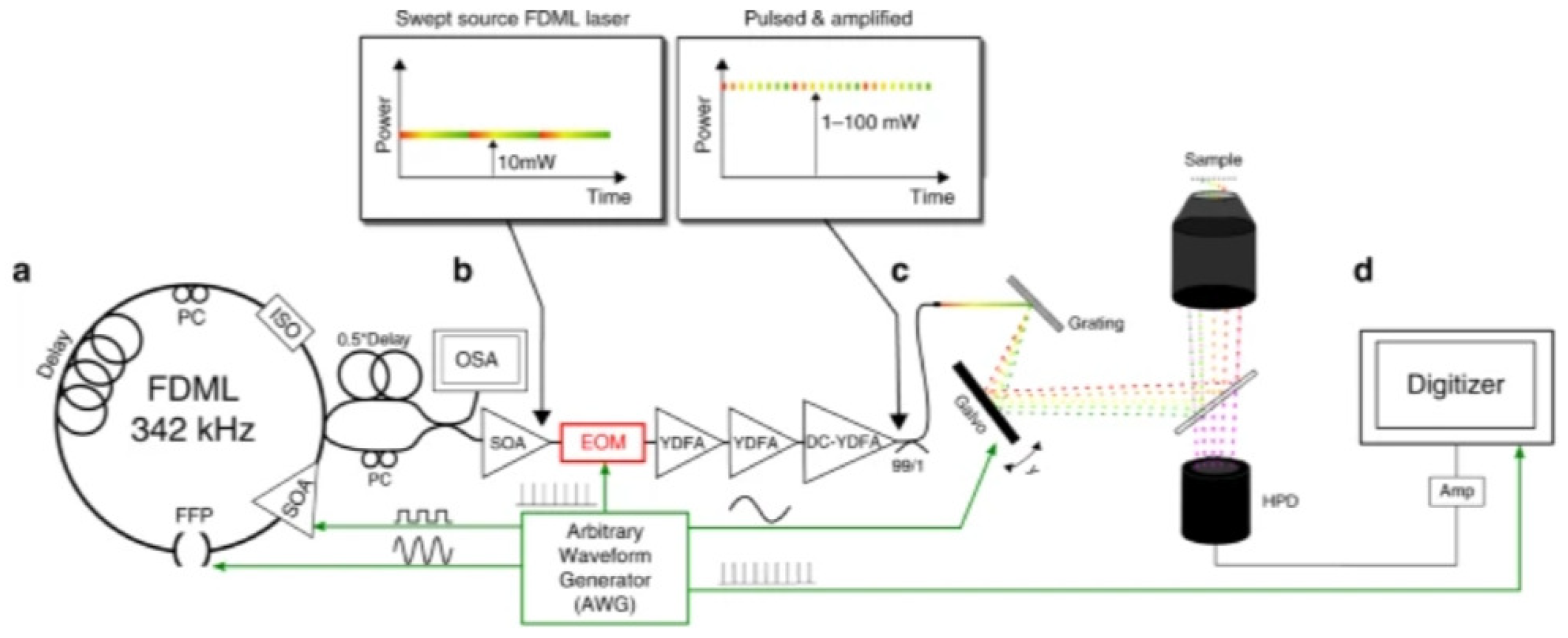

35]. As shown in

Figure 10, in the FDML Raman microscope system proposed by [

36], a fast wavelength-swept FDML laser serves as the Raman probe, while a laser incorporating a master oscillator power amplifier (MOPA) and Raman-shifted emission is employed as the Raman pump. The FDML-MOPA system, which includes probe and pump lasers, produces near-infrared nanosecond optical pulses with adjustable pulse lengths and repetition rates. By employing the TICO-Raman concept, the researchers successfully generated high-resolution excited Raman spectra [

36]. They also achieved a nonlinear excited Raman scatter spectrum with noise reduced to the ultimate scatter noise limit by optimizing the matching of the pump pulse length to the detection bandwidth [

37]. This approach ensured that the excited Raman amplification effect was fully and effectively digitized.

3.2.2. Absorption Spectroscopy

FDML-based high-speed spectroscopy has considerable potential for real-time spectral analysis, offering a novel and efficient tool characterized by its high temporal resolution. Kranendonk introduced a method for monitoring the temperature of high-speed engine gases by detecting molecular absorption spectra [

38]. This technique utilizes an FDML laser combined with a time-division-multiplexed split-pulse data acquisition system. It monitors the temperature of high-speed engine gases by measuring the H

2O absorption spectra with a spectral resolution higher than 0.1 nm. Previously, Kranendonk proposed using FDML lasers to derive water vapor temperatures in homogeneous charge compression ignition engines, aiding combustion diagnostics [

39].

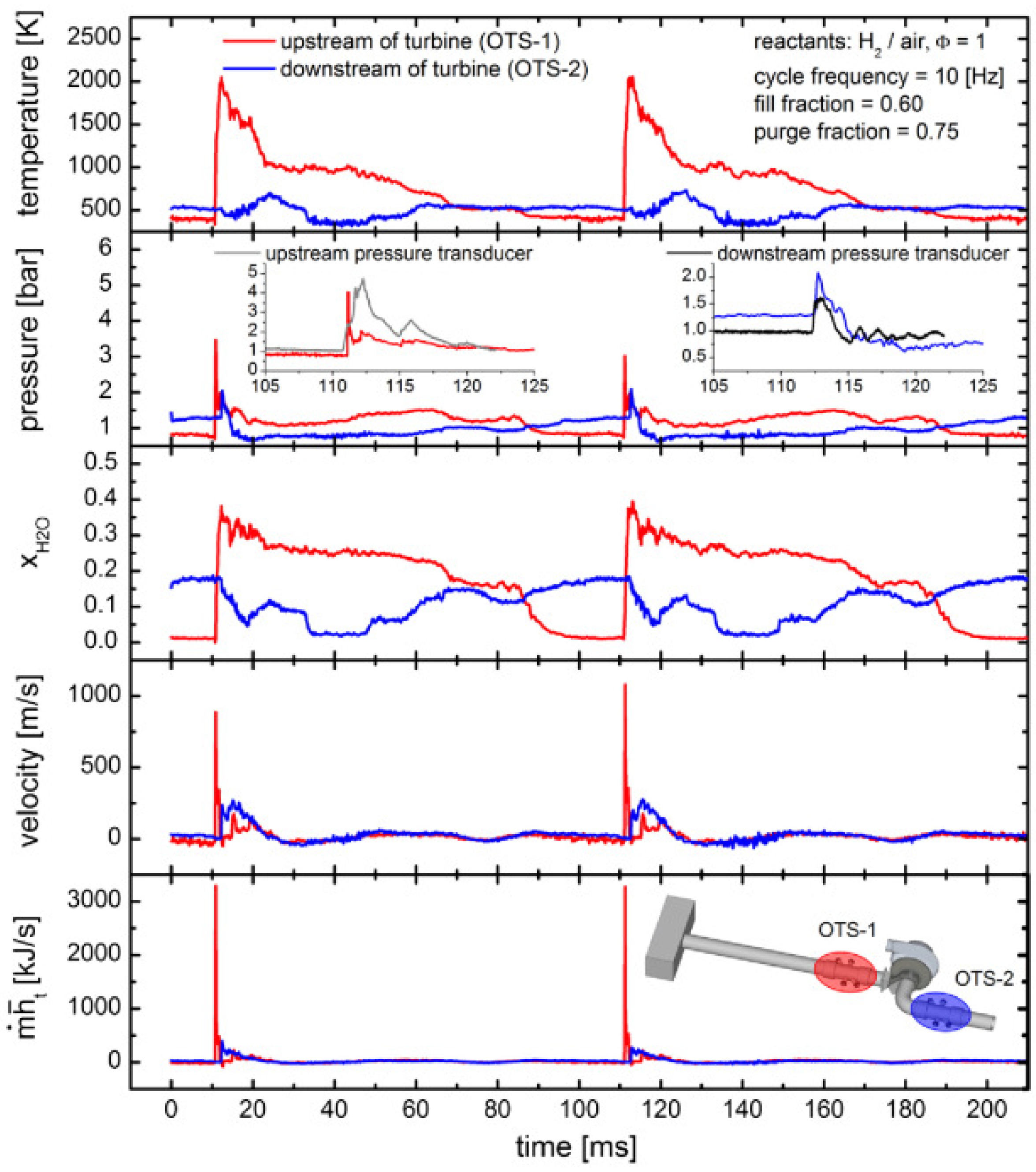

The integration of tomography and hyperspectral absorption spectroscopy enhances traditional absorption-based diagnostics. The TDM3-FDML hyperspectral source, composed of three time-division-multiplexed (TDM) FDML lasers, enables simultaneous 2D imaging of temperature and H

2O concentration across 225 spatial grid points with a temporal resolution of 50 kHz [

40]. In 2013, this technique was utilized to measure temperature, pressure, H

2O concentration, and gas velocity at a temporal resolution of approximately 50 kHz over a sustained period of 2s [

6], as shown in

Figure 11.

Yamaguchi et al. developed a fast and broadband spectroscopic measurement system using an FDML laser operating at approximately 1550 nm [

41]. This broadband FDML laser employs two SOAs with center wavelengths of 1509 and 1554 nm, achieving a scanning bandwidth of 120 nm centered at 1544 nm, along with a high scanning rate of 50.7 kHz. This system is anticipated to be utilized for the acquisition of gas absorption spectra in future applications.

3.3. Nonlinear Microscopy Techniques

3.3.1. Laser Confocal Microscopy

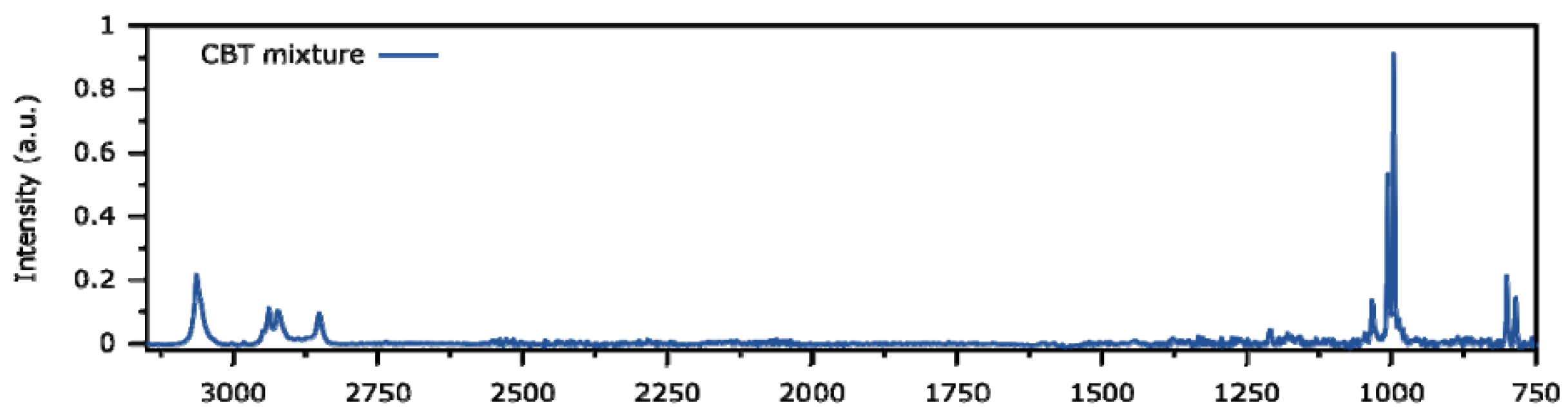

FDML lasers are extensively utilized in stimulated Raman scattering (SRS) microscopy owing to the rapid wavelength-scanning capabilities. These lasers enable high-speed, narrow linewidth optical frequency-scanning, which is crucial for achieving high-resolution SRS imaging. Eibl et al. developed an excited Raman microscopy system based on the FDML-MOAP system and the TICO-Raman concept [

42]. This system detects specific Raman bands by adjusting the relative timing between the pump and detection lasers, covering a spectral range from 750

to 3200

, as shown in

Figure 12.

Particularly, the fingerprint region from 400

to 2000

allows for highly specific hyperspectral Raman imaging because of the presence of numerous distinct Raman bands in this area. Hakert et al. combined a 1064 nm pump laser with a 1300 nm FDML laser to achieve highly specific hyperspectral Raman imaging [

43]. Utilizing the TICO-Raman concept, they time coded the wavelength of the excited Raman transition, achieving hyperspectral imaging in the range of 1500–1800

.

3.3.2. Optical Coherence Microscopy (OCM)

OCT and confocal scanning microscopy are powerful techniques currently used for in vivo imaging of tissue microstructures [

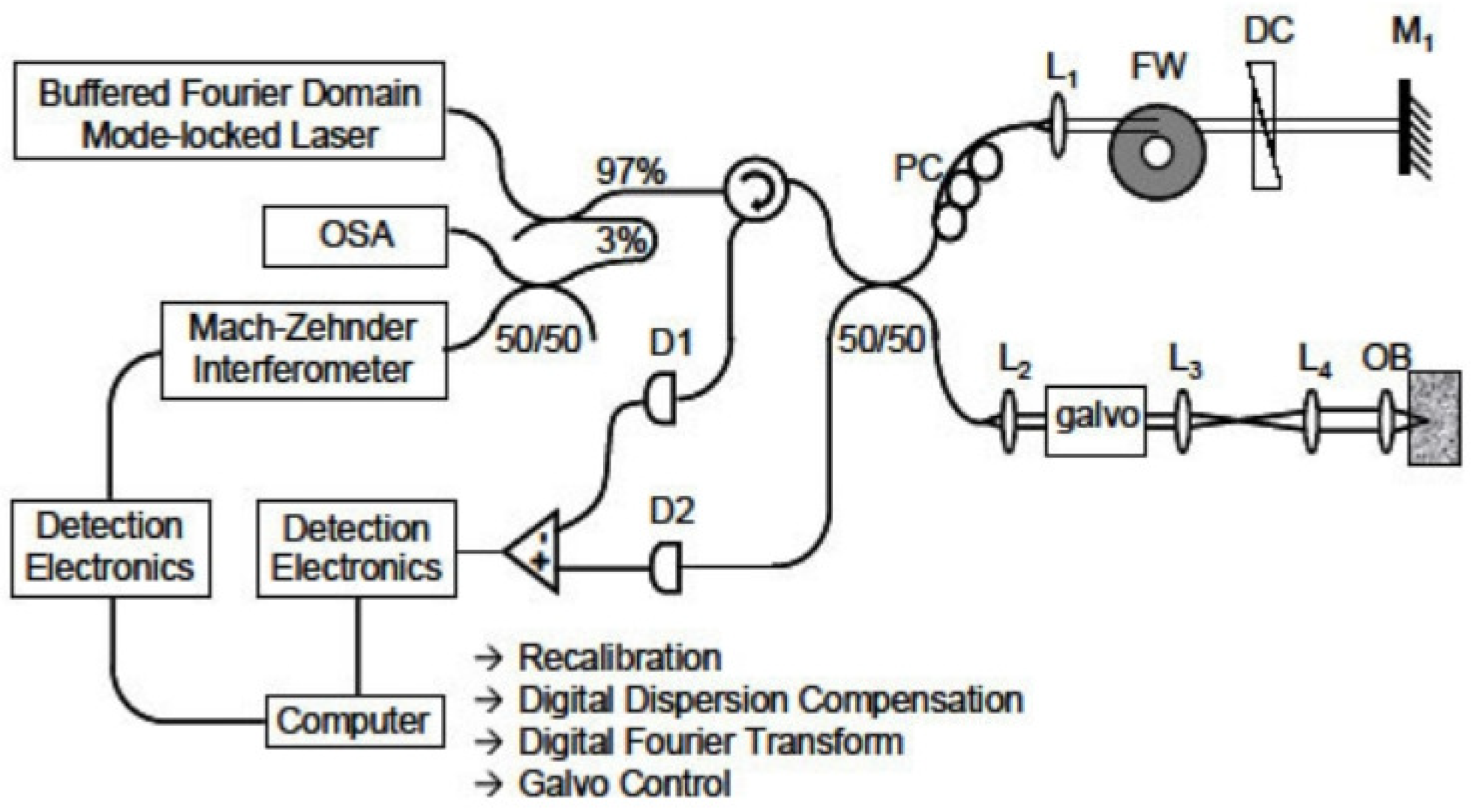

44]. The emergence of OCM technology combines the advantages of confocal microscopy for high-resolution imaging and high-sensitivity coherence-gated detection. It enables deeper imaging depth and higher contrast in highly scattering biological tissues compared with conventional confocal microscopy. As shown in

Figure 13, Huang et al. demonstrated the use of an FDML laser with a center wavelength of 1290 nm and a scan rate of 370 kHz for scanning source OCM imaging [

45]. An objective with an effective numerical aperture of approximately 0.35 (corresponding to a theoretical confocal gate of about 16

) strikes a balance between lateral resolution and depth of field. This approach allows for the extraction of a series of high-quality, coherently gated images from a 3D dataset. An image resolution of 1.6

× 8

(lateral × axial) with a sensitivity greater than 98 dB has been achieved, and cellular resolution imaging has been demonstrated in an African clawed toad tadpole, a rat kidney, and a human colon.

3.3.3. Fluorescence Microscopy

Two-photon microscopy is increasingly utilized in biological and medical research given its high sensitivity, molecular specificity, and ability to penetrate deep tissues. Karpf et al. proposed a high-speed laser scanning technique for nonlinear imaging [

46]. In the system setup shown in

Figure 14, the pulse output from the FDML-MOPA laser is directed to a diffraction grating for line scanning. They also introduced a spectro-temporal encoding technique, in which each pulse illuminates a distinct pixel both in time and in space. This advanced system can record fluorescence lifetimes at an impressive rate of 88 million pixels per second, operating at an FDML scan rate of 342 kHz. This fast two-photon microscopy is termed spectral laser imaging diffraction excitation (SLIDE) microscopy. Quasi-phase-matched broadband frequency doubling in a sector-periodically polarized lithium niobate crystal shifts the output of the FDML-MOPA laser to around 780 nm. Consequently, the SLIDE system enables 780 nm two-photon microimaging at a frame rate of 2 kHz [

47]. This capability allows for imaging using UV-excited dyes or endogenous autofluorescence, addressing the limitations of the previous system [

46], which was unable to utilize red dyes.

3.4. Measurement

3.4.1. Frequency Measurement

Real-time measurement of microwave frequencies is essential in critical domains, such as radar, communications. Although conventionl measurement methods offer high resolution, they often exhibit high power consumption, susceptibility to electromagnetic interference, and limitations in handling only single-tone microwave signals. In practice, however, received signals may comprise various unknown frequency components, necessitating multi-tone signal measurements.

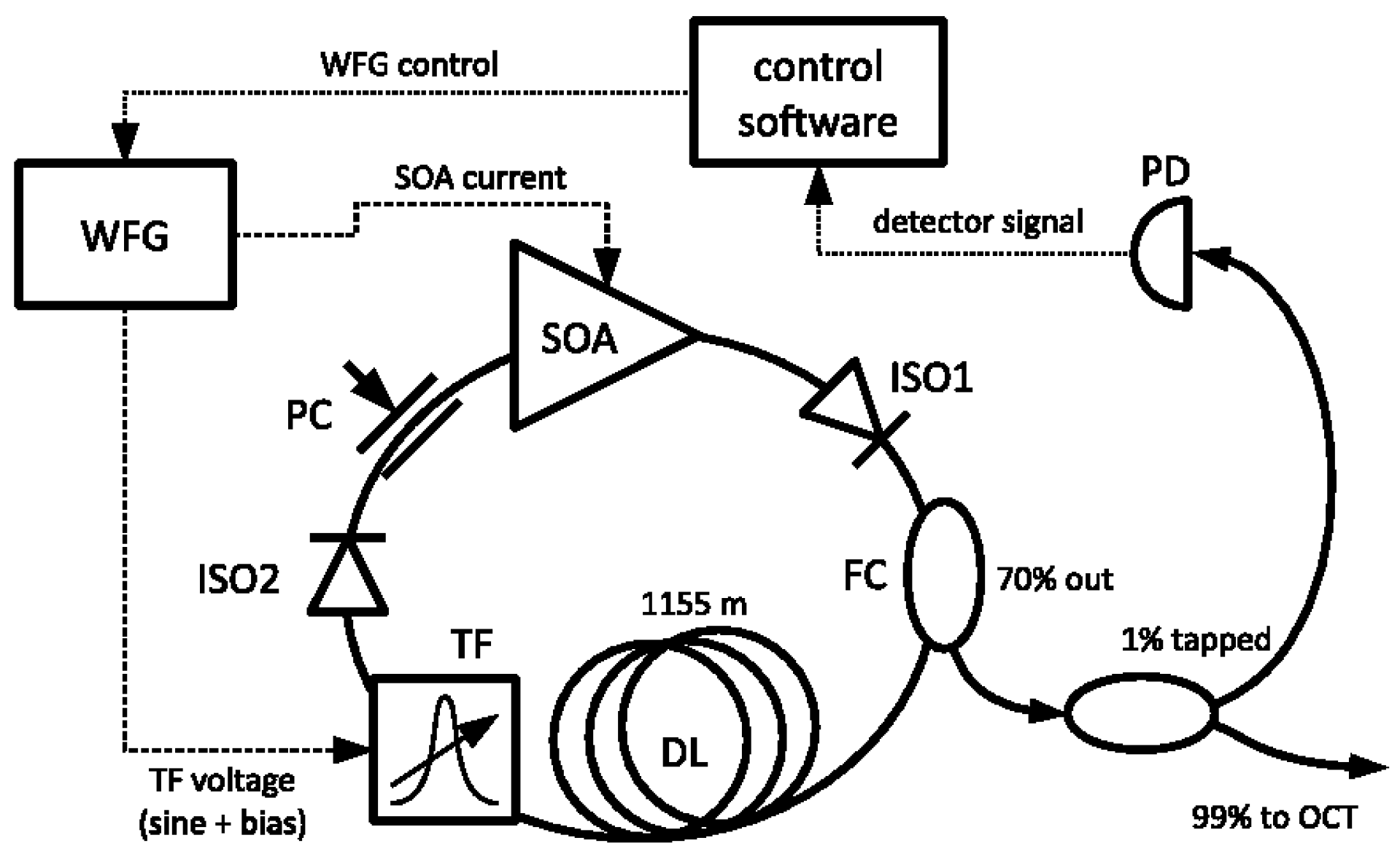

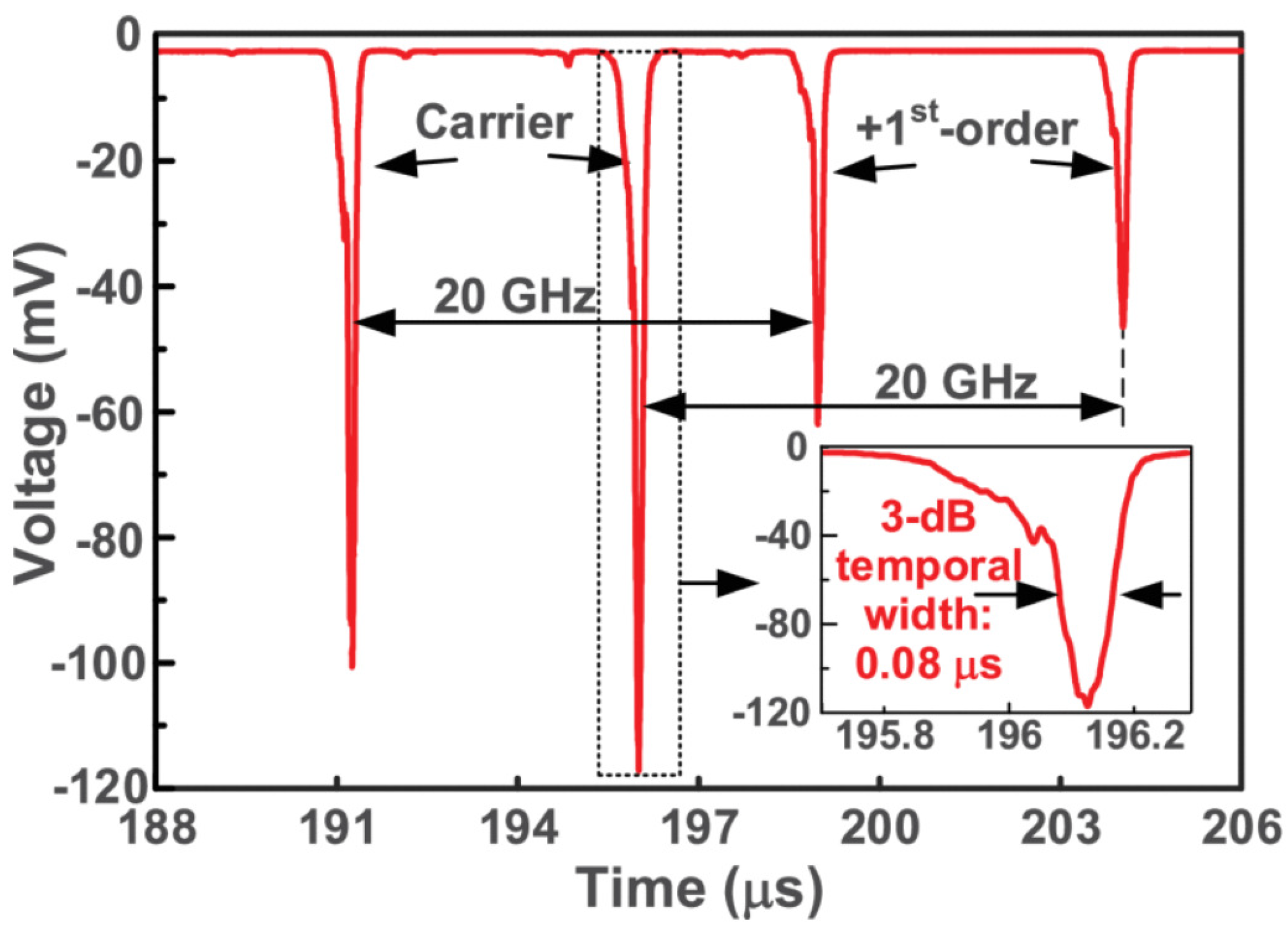

The frequency-time mapping technique in photon-based measurements establishes a relationship between the frequency of an unknown input microwave signal and the time difference of the output pulse, enabling multi-frequency measurements. Hao et al. utilized frequency-time mapping technology and the frequency sweep capabilities of an FDML optoelectronic oscillator (OEO) to achieve microwave frequency measurements [

7]. The measurement system achieved a range of 15 GHz with a measurement error of less than 60 MHz. To further enhance the measurement range, they proposed using an FDML OEO operating near the oscillation threshold, achieving a range of up to 16 GHz with a measurement error of only 0.07 GHz [

48].

In the improved system, an electronically controlled silicon microdisk resonator with a linewidth of 60 pm was incorporated into the FDML loop as a tunable optical filter. The frequency information of the microwave signal is mapped into the time domain using broadband-swept chirped pulses generated by a laser. A low-speed oscilloscope then detects the time delay to measure the microwave frequency. This enhanced system successfully performs single- and multi-tone microwave frequency measurements over a range of up to 20 GHz, as shown in

Figure 15, with a measurement resolution of 200 MHz and an accuracy higher than ± 100 MHz [

49].

3.4.2. Temperature Measurement

Microwave photonics, an emerging field, has recently been proposed and demonstrated for temperature sensing. This technology, particularly based on FDML lasers, offers a novel solution for real-time temperature measurement by converting wavelength changes in the optical domain into microwave frequency changes in the electrical domain. Wang et al. proposed a high-speed, high-resolution temperature sensor utilizing microwave photonics [

8]. In this approach, sensing information is encoded into the spectrum as broadband frequency-chirped optical pulses are delivered from an FDML laser to two cascaded fiber-optic Sagnac loops. Through spectral shaping and wavelength-to-time mapping, the encoded sensing information is converted into the time domain, enabling high-resolution temperature sensing. This developed sensor achieves a remarkable temperature resolution of

°C with a sampling rate of up to 23.497 kHz.

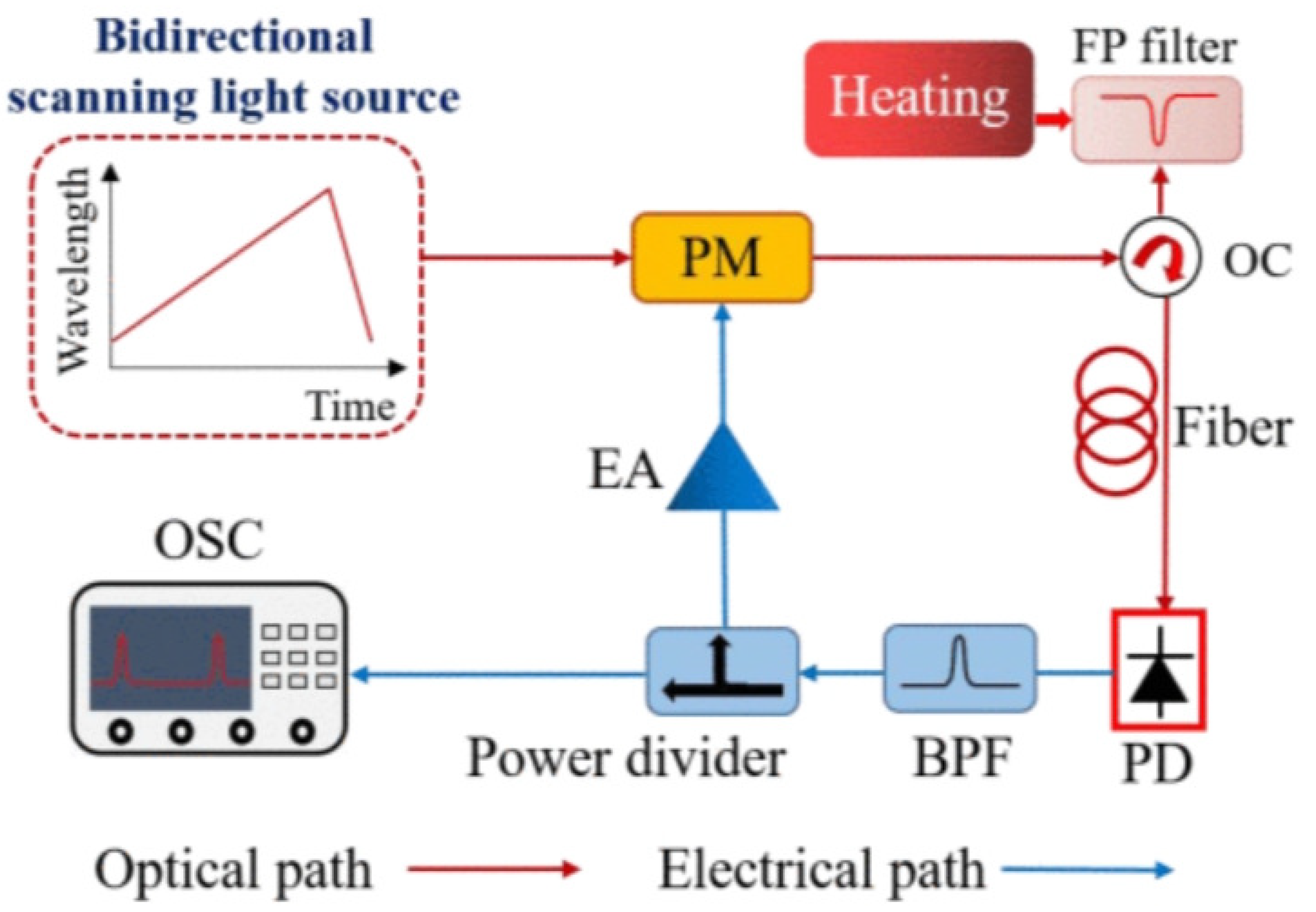

As shown in

Figure 16, Wang et al. introduced a novel temperature sensor based on an FDML OEO and temperature-to-time mapping [

50]. The bidirectional scanning microwave photonic filter (MPF) comprises a bidirectional scanning light source and a temperature-sensitive Fabry–Pérot optical trap filter. The MPF is critical for OEO-based temperature sensors, allowing for the mapping of temperature changes to oscillation frequency. By incorporating a narrow-band pass filter into the FDML OEO loop alongside the MPF, they established the desired temperature-time mapping relationship, achieving a high sensitivity of

°C and a resolution of 0.03°C.

3.5. Microwave Signal Generation

Brillouin ring cavity laser technology has advanced significantly in recent years. Laser based on stimulated Brillouin scattering demonstrates considerable potential for applications in various fields, including laser gyroscopes [

51] and temperature sensing systems [

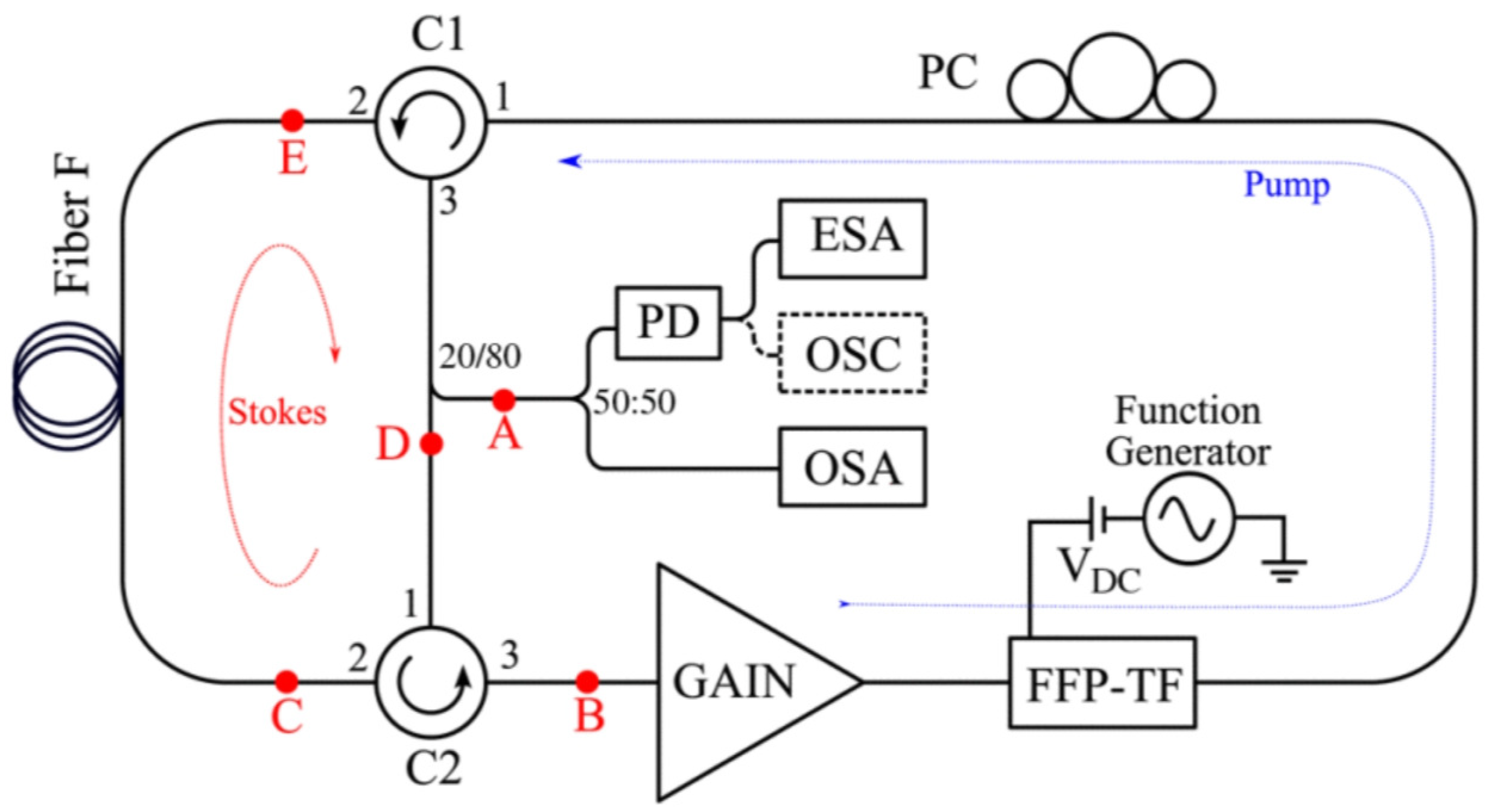

52], owing to narrow linewidth gain, low threshold power, and high coherence. Leveraging these properties, along with the high-speed scanning capabilities of FDML lasers, Galindez et al. proposed an FDML-pumped Brillouin fiber laser with tunable pulses and wavelengths [

53], as shown in

Figure 17. This tunable laser comprises two ring cavities: a primary fiber ring cavity for generating FDML signals and a secondary fiber ring cavity for amplifying Stokes signals. A spectral tuning range of 2.54 nm centered at 1531 nm was achieved by adjusting the offset voltage of the fiber Fabry–Pérot tunable filter. In addition, through varying the amplitude of the modulation signal applied to the fiber Fabry–Pérot filter, the Brillouin linewidth of the laser was modified from 0.282 nm to 0.462 nm.

4. Conclusion

As a novel mode-locking mechanism, FDML lasers address the limitations of traditional wavelength-scanning light sources, which are often constrained by the accumulation time of signals arising from spontaneous emissions. FDML lasers offer several advantages, including rapid wavelength scanning, narrow instantaneous linewidths, fast and stable operating modes, and excellent phase stability, making them highly promising for various applications. However, several challenges remain to be addressed. First, stability and noise in FDML lasers are critical issues. Frequency noise can degrade imaging accuracy, especially during prolonged scans, which may reduce coherence and affect image clarity. For efficient locking and stable operation, precise control of several laser parameters, including cavity dispersion, the properties of the gain medium, and thedriving frequency of the scanning filter, is necessary.Second, increasing output power poses another challenge. While FDML lasers can generate high signal-to-noise ratio outputs with narrow linewidths, maintaining these characteristics while boosting power output requires further technological advancements.Third, extending the coherence length is a key research focus. Although FDML lasers have achieved coherence lengths of tens of meters, further improvement is needed for deep tissue imaging and applications requiring large imaging ranges.Lastly, the miniaturization and integration of FDML lasers present significant challenges. With increasing demand for portable and low-cost optical imaging devices, integrating FDML lasers with other optical components into a compact system while maintaining high performance is a current research priority.With continued technological advances, FDML lasers are expected to enable ultrahigh-speed, high-resolution, and deep real-time imaging, remarkably contributing to a broad range of applications.

References

- Huber, R.; Wojtkowski, M.; Fujimoto, J. Fourier Domain Mode Locking (FDML): A new laser operating regime and applications for optical coherence tomography. Optics express 2006, 14, 3225–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slepneva, S.; O’shaughnessy, B.; Kelleher, B.; Hegarty, S.; Vladimirov, A.; Lyu, H.C.; Karnowski, K.; Wojtkowski, M.; Huyet, G. Dynamics of a short cavity swept source OCT laser. Optics express 2014, 22, 18177–18185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jirauschek, C.; Biedermann, B.; Huber, R. A theoretical description of Fourier domain mode locked lasers. Optics express 2009, 17, 24013–24019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinivasan, V.J.; Adler, D.C.; Chen, Y.; Gorczynska, I.; Huber, R.; Duker, J.S.; Schuman, J.S.; Fujimoto, J.G. Ultrahigh-speed optical coherence tomography for three-dimensional and en face imaging of the retina and optic nerve head. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2008, 49, 5103–5110. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, M.; Adler, D.; Gargesha, M.; Huber, R.; Rothenberg, F.; Belding, J.; Watanabe, M.; Wilson, D.; Fujimoto, J.; Rollins, A. Ultrahigh-speed optical coherence tomography imaging and visualization of the embryonic avian heart using a buffered Fourier Domain Mode Locked laser. Optics express 2007, 15, 6251–6267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caswell, A.W.; Roy, S.; An, X.; Sanders, S.T.; Schauer, F.R.; Gord, J.R. Measurements of multiple gas parameters in a pulsed-detonation combustor using time-division-multiplexed Fourier-domain mode-locked lasers. Applied optics 2013, 52, 2893–2904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Tang, J.; Li, W.; Zhu, N.; Li, M. Microwave photonics frequency-to-time mapping based on a Fourier domain mode locked optoelectronic oscillator. Optics Express 2018, 26, 33582–33591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Liao, B.; Cao, Y.; Feng, X.; Guan, B.O.; Yao, J. Microwave photonic interrogation of a high-speed and high-resolution temperature sensor based on cascaded fiber-optic sagnac loops. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2020, 39, 4041–4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, T.; Wieser, W.; Reznicek, L.; Neubauer, A.; Kampik, A.; Huber, R. Multi-mhz retinal oct. Biomedical optics express 2013, 4, 1890–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, K.; Meemon, P.; Lee, K.S.; Delfyett, P.J.; Rolland, J.P. Broadband Fourier-domain mode-locked lasers. Photonic Sensors 2011, 1, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, R.; Wojtkowski, M.; Taira, K.; Fujimoto, J.G.; Hsu, K. Amplified, frequency swept lasers for frequency domain reflectometry and OCT imaging: design and scaling principles. Optics express 2005, 13, 3513–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, D.; Shi, Y.; Li, F.; Wai, P.K.A. Fourier domain mode locked laser and its applications. Sensors 2022, 22, 3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, R.; Adler, D.C.; Srinivasan, V.J.; Fujimoto, J.G. Fourier domain mode locking at 1050 nm for ultra-high-speed optical coherence tomography of the human retina at 236,000 axial scans per second. Optics letters 2007, 32, 2049–2051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, T.; Wieser, W.; Eigenwillig, C.M.; Biedermann, B.R.; Huber, R. Megahertz OCT for ultrawide-field retinal imaging with a 1050nm Fourier domain mode-locked laser. Optics express 2011, 19, 3044–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, J.P.; Klein, T.; Kufner, C.L.; Wieser, W.; Neubauer, A.S.; Huber, R. Ultra-widefield retinal MHz-OCT imaging with up to 100 degrees viewing angle. Biomedical Optics Express 2015, 6, 1534–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, J.P.; Pfeiffer, T.; Eibl, M.; Hakert, H.; Huber, R. High-resolution retinal swept source optical coherence tomography with an ultra-wideband Fourier-domain mode-locked laser at MHz A-scan rates. Biomedical optics express 2017, 9, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimipour, M.; Migacz, J.V.; Zawadzki, R.J.; Werner, J.S.; Jonnal, R.S. Functional retinal imaging using adaptive optics swept-source OCT at 1.6 MHz. Optica 2019, 6, 300–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimipour, M.; Jonnal, R.S.; Werner, J.S.; Zawadzki, R.J. Coextensive synchronized SLO-OCT with adaptive optics for human retinal imaging. Optics letters 2019, 44, 4219–4222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torzicky, T.; Marschall, S.; Pircher, M.; Baumann, B.; Bonesi, M.; Zotter, S.; Götzinger, E.; Trasischker, W.; Klein, T.; Wieser, W.; others. Retinal polarization-sensitive optical coherence tomography at 1060 nm with 350 kHz A-scan rate using an Fourier domain mode locked laser. Journal of biomedical optics 2013, 18, 026008–026008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gora, M.; Karnowski, K.; Szkulmowski, M.; Kaluzny, B.J.; Huber, R.; Kowalczyk, A.; Wojtkowski, M. Ultra high-speed swept source OCT imaging of the anterior segment of human eye at 200 kHz with adjustable imaging range. Optics Express 2009, 17, 14880–14894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnowski, K.; Kaluzny, B.J.; Szkulmowski, M.; Gora, M.; Wojtkowski, M. Corneal topography with high-speed swept source OCT in clinical examination. Biomedical Optics Express 2011, 2, 2709–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieser, W.; Klein, T.; Adler, D.C.; Trépanier, F.; Eigenwillig, C.M.; Karpf, S.; Schmitt, J.M.; Huber, R. Extended coherence length megahertz FDML and its application for anterior segment imaging. Biomedical optics express 2012, 3, 2647–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, X.; Tan, B.; Ho, Y.; Liu, X.; Wong, D.; Chua, J.; Wong, T.T.; Perera, S.; Ang, M.; Werkmeister, R.M.; others. Full circumferential morphological analysis of Schlemm’s canal in human eyes using megahertz swept source OCT. Biomedical optics express 2021, 12, 3865–3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Wieser, W.; Springeling, G.; Beurskens, R.; Lancee, C.T.; Pfeiffer, T.; Van Der Steen, A.F.; Huber, R.; Soest, G.v. Intravascular optical coherence tomography imaging at 3200 frames per second. Optics letters 2013, 38, 1715–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Pfeiffer, T.; Regar, E.; Wieser, W.; van Beusekom, H.; Lancee, C.T.; Springeling, G.; Krabbendam, I.; van der Steen, A.F.; Huber, R.; others. Heartbeat OCT: in vivo intravascular megahertz-optical coherence tomography. Biomedical optics express 2015, 6, 5021–5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Pfeiffer, T.; Daemen, J.; Mastik, F.; Wieser, W.; van der Steen, A.F.; Huber, R.; Van Soest, G. Simultaneous morphological and flow imaging enabled by megahertz intravascular Doppler optical coherence tomography. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2019, 39, 1535–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Singh, M.; Lopez III, A.L.; Wu, C.; Raghunathan, R.; Schill, A.; Li, J.; Larin, K.V.; Larina, I.V. Direct four-dimensional structural and functional imaging of cardiovascular dynamics in mouse embryos with 1.5 MHz optical coherence tomography. Optics letters 2015, 40, 4791–4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.T.; Jenkins, M.W.; Rollins, A.M. Fiber-optic catheter-based polarization-sensitive OCT for radio-frequency ablation monitoring. Optics letters 2014, 39, 5066–5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, W.; Draxinger, W.; Klein, T.; Karpf, S.; Pfeiffer, T.; Huber, R. High definition live 3D-OCT in vivo: design and evaluation of a 4D OCT engine with 1 GVoxel/s. Biomedical optics express 2014, 5, 2963–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, J.P.; Draxinger, W.; Klee, J.; Pfeiffer, T.; Eibl, M.; Klein, T.; Wieser, W.; Huber, R. Live video rate volumetric OCT imaging of the retina with multi-MHz A-scan rates. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0213144. [Google Scholar]

- Göb, M.; Pfeiffer, T.; Draxinger, W.; Lotz, S.; Kolb, J.P.; Huber, R. Continuous spectral zooming for in vivo live 4D-OCT with MHz A-scan rates and long coherence. Biomedical Optics Express 2022, 13, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, D.C.; Huang, S.W.; Huber, R.; Fujimoto, J.G. Photothermal detection of gold nanoparticles using phase-sensitive optical coherence tomography. Optics express 2008, 16, 4376–4393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, D.C.; Stenger, J.; Gorczynska, I.; Lie, H.; Hensick, T.; Spronk, R.; Wolohojian, S.; Khandekar, N.; Jiang, J.Y.; Barry, S.; others. Comparison of three-dimensional optical coherence tomography and high resolution photography for art conservation studies. Optics Express 2007, 15, 15972–15986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Lee, H.C.; Vermeulen, D.; Chen, L.; Nielsen, T.; Park, S.Y.; Ghaemi, A.; Swanson, E.; Doerr, C.; Fujimoto, J. Silicon photonic integrated circuit swept-source optical coherence tomography receiver with dual polarization, dual balanced, in-phase and quadrature detection. Biomedical optics express 2015, 6, 2562–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpf, S.; Eibl, M.; Wieser, W.; Klein, T.; Huber, R. A Time-Encoded Technique for fibre-based hyperspectral broadband stimulated Raman microscopy. Nature Communications 2015, 6, 6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpf, S.; Eibl, M.; Wieser, W.; Klein, T.; Huber, R. Time-encoded Raman scattering (TICO-Raman) with Fourier domain mode locked (FDML) lasers. European Conference on Biomedical Optics. Optica Publishing Group, 2015, p. 95410F.

- Karpf, S.; Eibl, M.; Wieser, W.; Klein, T.; Huber, R. Shot-Noise Limited Time-Encoded Raman Spectroscopy. Journal of Spectroscopy 2017, 2017, 9253475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranendonk, L.A.; An, X.; Caswell, A.W.; Herold, R.E.; Sanders, S.T.; Huber, R.; Fujimoto, J.G.; Okura, Y.; Urata, Y. High speed engine gas thermometry by Fourier-domain mode-locked laser absorption spectroscopy. Optics Express 2007, 15, 15115–15128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kranendonk, L.A.; Walewski, J.W.; Sanders, S.T.; Huber, R.; Fujimoto, J.G. Measurements of gas temperature in an HCCI engine by use of a Fourier-domain mode-locking laser. Laser Applications to Chemical, Security and Environmental Analysis. Optica Publishing Group, 2006, p. TuB2.

- Ma, L.; Li, X.; Sanders, S.T.; Caswell, A.W.; Roy, S.; Plemmons, D.H.; Gord, J.R. 50-kHz-rate 2D imaging of temperature and H 2 O concentration at the exhaust plane of a J85 engine using hyperspectral tomography. Optics express 2013, 21, 1152–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, T.; Nakamoto, A.; Shinoda, Y. Consideration of spectroscopic measurements with broadband Fourier domain mode-locked laser with two semiconductor optical amplifiers at 1550 nm. Optical Engineering 2023, 62, 036101–036101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibl, M.; Karpf, S.; Wieser, W.; Klein, T.; Huber, R. Hyperspectral stimulated Raman microscopy with two fiber laser sources. European Conference on Biomedical Optics. Optica Publishing Group, 2015, p. 953604.

- Hakert, H.; Eibl, M.; Tillich, M.; Pries, R.; Hüttmann, G.; Brinkmann, R.; Wollenberg, B.; Bruchhage, K.L.; Karpf, S.; Huber, R. Time-encoded stimulated Raman scattering microscopy of tumorous human pharynx tissue in the fingerprint region from 1500–1800 cm-1. Optics Letters 2021, 46, 3456–3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A.; Hsiung, P.; Ko, T.; Hartl, I.; Fujimoto, J. High-resolution optical coherence microscopy for high-speed, in vivo cellular imaging. Optics letters 2003, 28, 2064–2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.W.; Aguirre, A.D.; Huber, R.A.; Adler, D.C.; Fujimoto, J.G. Swept source optical coherence microscopy using a Fourier domain mode-locked laser. Optics express 2007, 15, 6210–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpf, S.; Riche, C.T.; Di Carlo, D.; Goel, A.; Zeiger, W.A.; Suresh, A.; Portera-Cailliau, C.; Jalali, B. Spectro-temporal encoded multiphoton microscopy and fluorescence lifetime imaging at kilohertz frame-rates. Nature communications 2020, 11, 2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutscher, T.F.; Stock, C.; Sommer, F.; Jurkevicius, J.; Meyer, S.; Gruber, A.; Hunold, A.; Wiggert, M.; Leonardt, C.; Lamminger, P.; others. Kilohertz Two-Photon SLIDE Microscopy using a newly developed 780nm excitation laser. European Conference on Biomedical Optics. Optica Publishing Group, 2023, p. 126300B.

- Hao, T.; Tang, J.; Shi, N.; Li, W.; Zhu, N.; Li, M. Multiple-frequency measurement based on a Fourier domain mode-locked optoelectronic oscillator operating around oscillation threshold. Optics letters 2019, 44, 3062–3065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, B.; Tang, J.; Zhang, W.; Pan, S.; Yao, J. Broadband instantaneous multi-frequency measurement based on a Fourier domain mode-locked laser. IEEE Transactions on Microwave Theory and Techniques 2021, 69, 4576–4583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Hao, T.; Li, G.; Li, M.; Zhu, N.; Li, W. Microwave photonic temperature sensing based on Fourier domain mode-locked OEO and temperature-to-time mapping. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2022, 40, 5322–5327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarinetchi, F.; Smith, S.; Ezekiel, S. Stimulated Brillouin fiber-optic laser gyroscope. Optics letters 1991, 16, 229–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culverhouse, D.; Farahi, F.; Pannell, C.; Jackson, D. Potential of stimulated Brillouin scattering as sensing mechanism for distributed temperature sensors. Electronics letters 1989, 25, 913–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galindez, C.; Lopez-Higuera, J. Pulsed Wavelength-Tunable Brillouin Fiber Laser Based on a Fourier-Domain Mode-Locking Source. IEEE Photonics Journal 2013, 5, 1500907–1500907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).