Submitted:

30 October 2024

Posted:

31 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This study combines two methodologies—key indicators from the Sustainable Livelihoods Framework (SLF) and the Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture Systems (SAFA) approach—to evaluate sustainability among 330 producers from three associations working within the recently recognized Amazonian Chakra system, designated as a Globally Important Agricultural Heritage System (GIAHS). The SAFA framework's four dimensions—Good Governance, Environmental Integrity, Economic Resilience, and Social Well-being—were used to assess sustainability, while the SLF considered key capitals such as financial, natural, and human capitals as critical for understanding livelihood outcomes. The discriminant analysis revealed significant differences across the associations, with Kallari and Wiñak performing better in financial management, environmental practices, and governance compared to Tsatsayaku, which exhibited weaker outcomes in these domains. Key indicators such as chakra income, price determination, and civic responsibility were the most effective in distinguishing the groups. The income analysis further highlights that Tsatsayaku reported the highest total income but relies heavily on non-Chakra sources, while Kallari and Wiñak showed stronger reliance on Chakra income, which aligns with their more sustainable agricultural practices. Per-capita income was higher for Tsatsayaku, but extreme poverty levels remained similar across all associations, underscoring the need for targeted financial interventions. Policy recommendations include promoting access to financial resources and strengthening participatory governance models to enhance sustainability outcomes across associations. For future research, combining the SAFA and SLF provides a comprehensive and robust methodology for assessing sustainability in agricultural systems, enabling a deeper understanding of the interactions between social, economic, and environmental factors in diverse contexts.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework and Context of the Amazonian Chakra

2.1. Sustainable Livelihoods Framework

2.2. Sustainability Assessment of Food and Agriculture Systems (SAFA)

2.3. Context of the Amazonian Chakra system

3. Materials and Methods

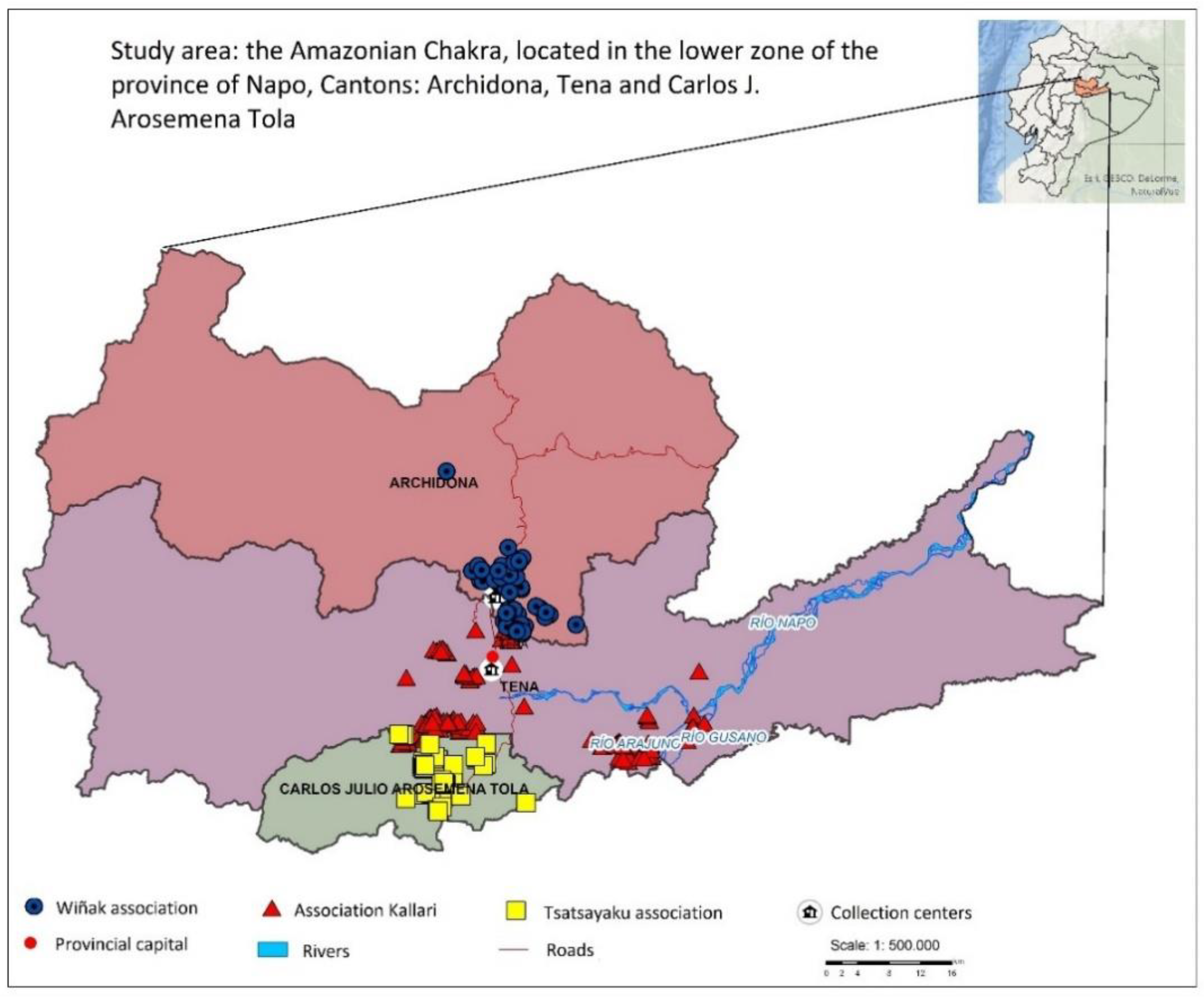

3.1. Study Area

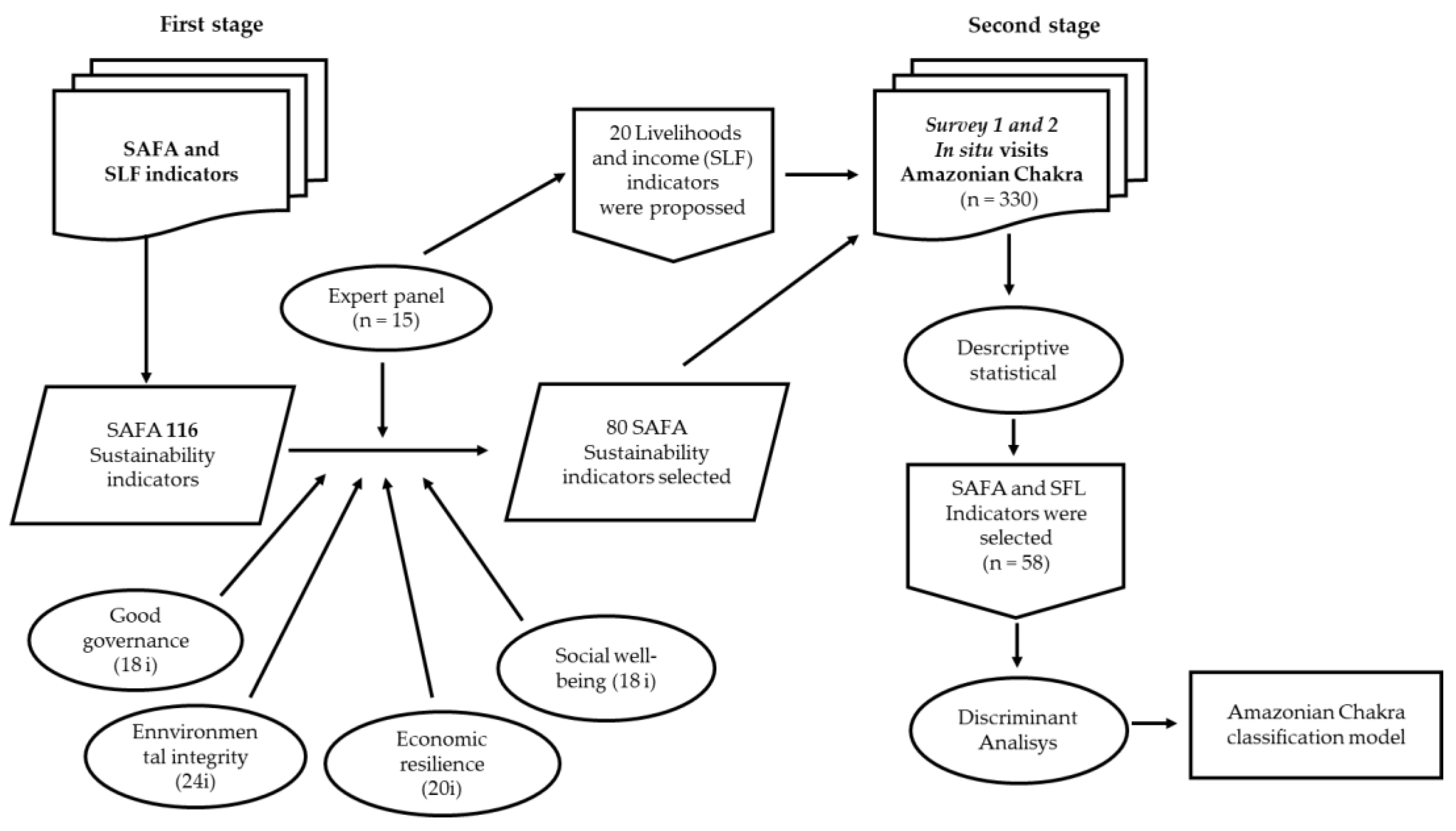

3.2. Sampling and Data Collection

3.3. Determination of Per Capita Income and Poverty Index

3.4. Research Design

3.5. Statistical Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Livelihoods in the Amazonian Chakra

| Livelihood variables | Mean n=330 |

Kallari n=156 |

Wiñak n=129 |

Tsatsayaku n=45 |

sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Capital (L-HC) | |||||

| Gender/Head of household (female%) | 59 | 57.7 a | 68.2 b | 51.1 a | * |

| Ethnicity (% Kichwa) | 88.4 | 94.2 b | 97.7 b | 73.3 a | *** |

| Household head age (years) | 48.7 | 51.8 a | 43.8 b | 50.5 a | *** |

| Social Capital (L-SC) | |||||

| Training received (BMP) (%) | 52.3 | 43.6 a | 51.2 a | 62.2 b | * |

| Natural Capital (L-NC) | |||||

| Chakra (ha) | 2.2 | 2.1 a | 1.9 a | 2.7 b | *** |

| Forest (ha) | 5.7 | 4.1 a | 1.2 a | 11.8 b | *** |

| Other crops (ha) | 0.4 | 0.0 a | 0.3 a | 1 b | ** |

| Total farm area (ha) | 8.4 | 6.2 a | 3.5 a | 15.6 b | *** |

| Finantial Capital (L-FC) | |||||

| Access to credit (%) | 08 | 9.6 a | 4.7 a | 24.4 b | ** |

| Access to government bonus (%) | 56 | 60.9 b | 62.0 b | 44.4 a | ** |

| Physical Capital (L-PhC) | |||||

| engine technology (yes=1) | 1.54 | 64.1 c | 24.8 a | 48.9 b | *** |

| Cell phone (yes=1) | 69 | 59.6 a | 62.0 a | 77.8 b | * |

4.2. Well-Being, Income, and Poverty Index in Households of the Amazonian Chakra

4.3. Sustainability Dimensions Assessment

4.3.1. Good Governance

4.3.2. Environmental Integrity

4.3.3. Economic Resilience

4.3.4. Social Welfare

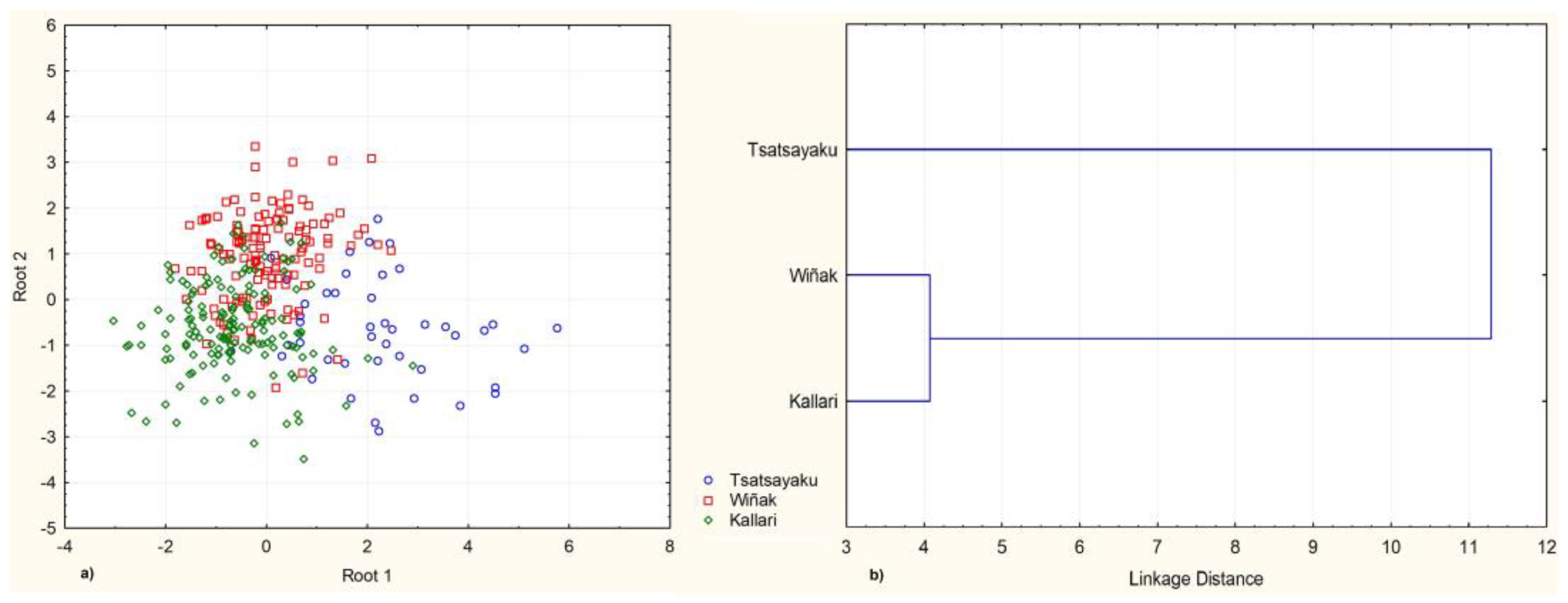

4.4. Multivariate Discriminant Analysis by Association (SAFA- SLF)

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chopin, P.; Mubaya, C.P.; Descheemaeker, K.; Öborn, I.; Bergkvist, G. Avenues for improving farming sustainability assessment with upgraded tools, sustainability framing and indicators. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 41, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prost, L.; Martin, G.; Ballot, R.; Benoit, M.; Bergez, J.-E.; Bockstaller, C.; Cerf, M.; Deytieux, V.; Hossard, L.; Jeuffroy, M.-H.; et al. Key research challenges to supporting farm transitions to agroecology in advanced economies. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 43, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, C.; Carney, D. Sustainable livelihoods: Lessons from early experience. Development 1999, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, F.; Biggs, S. Evolving Themes in Rural Development 1950s-2000s. Dev. Policy Rev. 2001, 19, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bebbington, A. Capitals and Capabilities, A Framework for Analyzing and rural livelihoods. World Dev. 1999, 27, 2021–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, C.; Soukoutou, R.; Sustainability, D.C.-; 2022, undefined Sustainability framing of controlled environment agriculture and consumer perceptions: A review. mdpi.com 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.H. ur; Ahrends, H.E.; Raza, A.; Gaiser, T. Current approaches for modeling ecosystem services and biodiversity in agroforestry systems: Challenges and ways forward. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, P.; Planning, N.E.-M.I.&; 2021, undefined Sustainability-oriented strategy and sustainable development goals. emerald.comPBO Claro, NR EstevesMarketing Intell. Planning, 2021•emerald.com.

- Goparaju, L.; Ahmad, F.; Uddin, M.; Questions, J.R.-E. ; 2020, undefined Agroforestry: An effective multi-dimensional mechanism for achieving Sustainable Development Goals. apcz.umk.pl 2020, 31, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terpstra, J. De Agricultura. In Antiquitas Homerica; 2024; pp. 223–233.

- Holt-Giménez, E. One Billion Hungry: Can We Feed the World? by Gordon Conway. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2013, 37, 968–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera-Vélez, R.; Cota-Sánchez, J.H.; Grijalva-Olmedo, J. Beta diversity and fallow length regulate soil fertility in cocoa agroforestry in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon. Agric. Syst. 2021, 187, 103020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadán, O.; Torres, B.; Selesi, D.; Peña, D.; Rosales, C.; Gunter, S. Diversidad Florística Y Estructura En Cacaotales Tradicionales Y Bosque Natural (Sumaco, Ecuador). Colomb. For. 2016, 19, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Jadan, O.; Aguirre, P.; Hinojosa, L.; Guenter, S. The contribution of traditional agroforestry to climate change adaptation in the Ecuadorian Amazon: The chakra system. In Handbook of Climate Change Adaptation; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015: Berlin, 2015; ISBN 978-3-642-38669-5. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, C.; Torres, B.; Alemán, R.; Marín, H.; Durazno, G.; Navarrete, H.; Gutiérrez, E.T.; Tapia, A. Indicadores morfológicos y estructurales de calidad y potencial de erosión del suelo bajo diferentes usos de la tierra en la Amazonía ecuatoriana. An. Geogr. la Univ. Complut. 2017, 37, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco Pérez, C.; Bilsborrow, R.; Torres, B. Income diversification of migrant colonists vs. indigenous populations: Contrasting strategies in the Amazon. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Vasco, C.; Günter, S.; Knoke, T. Determinants of agricultural diversification in a hotspot area: Evidence from colonist and indigenous communities in the Sumaco Biosphere Reserve, Ecuadorian Amazon. Sustain. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacPherson, J.; Voglhuber-Slavinsky, A.; Olbrisch, M.; Schöbel, P.; Dönitz, E.; Mouratiadou, I.; Helming, K. Future agricultural systems and the role of digitalization for achieving sustainability goals. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulé, E.; Michonneau, P.; Michel, N.; Bockstaller, C. Environmental sustainability assessment in agricultural systems: A conceptual and methodological review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero, A.M.; Thornton, P.K.; Notenbaert, A.M.; Wood, S.; Msangi, S.; Freeman, H.A.; Bossio, D.; Dixon, J.; Peters, M.; van de Steeg, J.; et al. Smart investments in sustainable food production: Revisiting mixed crop-livestock systems. Science (80-. ). 2010, 327, 822–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia-R, M.; Torres, B.; Cayambe, J.; Ramos, N.; Luna, M.; Diaz-Ambrona, C.G.H. Sustainability Assessment of Smallholder Agroforestry Indigenous Farming in the Amazon: A Case Study of Ecuadorian Kichwas. Agronomy 2020, 10, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Olde, E.M.; Oudshoorn, F.W.; Sørensen, C.A.G.; Bokkers, E.A.M.; De Boer, I.J.M. Assessing sustainability at farm-level: Lessons learned from a comparison of tools in practice. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 66, 391–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO SAFA Sustainability assessment of food and agriculture system - guidelines version 3.0; Rome, Italy, 2013;

- Arulnathan, V.; Heidari, M.D.; Doyon, M.; Li, E.; Pelletier, N. Farm-level decision support tools: A review of methodological choices and their consistency with principles of sustainability assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Andrade, A.; Enriquez, F.; Luna, M.; Heredia-R, M.; Bravo, C. Estudios sobre medios de vida, sostenibilidad y captura de carbono en el sistema agroforestal Chakra con cacao en comunidades de pueblos originarios de la provincia de Napo: casos de las asociaciones Kallari, Wiñak y Tsatsayaku, Amazonía Ecuatoriana.; Primera.; FAO-Ecuador: Quito, 2022; ISBN 978-9942-42-211-8. [Google Scholar]

- Heredia-R, M.; Torres, B.; Vasseur, L.; Puhl, L.; Barreto, D.; Díaz-Ambrona, C.G.H. Sustainability Dimensions Assessment in Four Traditional Agricultural Systems in the Amazon. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 5, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods a Framework for Analysis. Analysis 1998, 72, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, E. Metodología práctica para establecer los beneficios brutos de la extracción de madera de bosque natural a nivel de finca en ecuador, CATIE, 2023.

- Vasco, C.; Torres, B.; Jácome, E.; Torres, A.; Eche, D.; Velasco, C. Use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides in frontier areas: A case study in the Northern Ecuadorian Amazon. Land use policy 2021, 107, 105490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Günter, S.; Acevedo-Cabra, R.; Knoke, T. Livelihood strategies, ethnicity and rural income: The case of migrant settlers and indigenous populations in the Ecuadorian Amazon. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 86, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sherbinin, A.; VanWey, L.K.; McSweeney, K.; Aggarwal, R.; Barbieri, A.; Henry, S.; Hunter, L.M.; Twine, W.; Walker, R. Rural household demographics, livelihoods and the environment. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2008, 18, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, C.L.; Bilsborrow, R.E.; Bremner, J.L.; Lu, F. Indigenous land use in the Ecuadorian Amazon: A cross-cultural and multilevel analysis. Hum. Ecol. 2008, 36, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, F. The determinants of rural livelihood diversification in developing countries. J. Agric. Econ. 2000, 51, 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walelign, S.Z. Livelihood strategies, environmental dependency and rural poverty: the case of two villages in rural Mozambique. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2016, 593–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.M.; Kari, F.; Yahaya, S.R.B.; Al-Amin, A.Q. Livelihood Assets and Vulnerability Context of Marine Park Community Development in Malaysia. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 125, 771–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Wu, J.; Zhou, K.; Li, R. Livelihood resilience and livelihood construction path of China’s rural reservoir resettled households in the energy transition. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walelign, S.Z.; Jiao, X. Dynamics of rural livelihoods and environmental reliance: Empirical evidence from Nepal. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 0–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, M.; Barcellos-Paula, L. Structured Equations to Assess the Socioeconomic and Business Factors Influencing the Financial Sustainability of Traditional Amazonian Chakra in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Sustain. 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hřebíček, J.; Faldík, O.; …, E.K.-A. universitatis; 2015, undefined Determinants of sustainability reporting in food and agriculture sectors. acta.mendelu.czJ Hřebíček, O Faldík, E Kasem, O TrenzActa Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendelianae Brun. 2015•acta.mendelu.cz 2015, 63, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, P.K.; Herrero, M. Integrated crop-livestock simulation models for scenario analysis and impact assessment. In Proceedings of the Agricultural Systems; 2001; Vol. 70; pp. 581–602. [Google Scholar]

- Schader, C.; Grenz, J.; Meier, M.; society, M.S.-E. and; 2014, undefined Scope and precision of sustainability assessment approaches to food systems. JSTORC Schader, J Grenz, MS Meier, M StolzeEcology Soc. 2014•JSTOR 2014. [CrossRef]

- FAO Amazonian Chakra | Sistemas Importantes del Patrimonio Agrícola Mundial (SIPAM) | Organización de las Naciones Unidas para la Alimentación y la Agricultura | GIAHS | Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Available online:. Available online: https://www.fao.org/giahs/giahsaroundtheworld/designated-sites/latin-america-and-the-caribbean/amazon-chakra/es/ (accessed on Oct 27, 2024).

- Myers, N.; Mittermeier, R.A.; Fonseca, G.A.B.; Fonseca, G.A.B.; Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 2000, 403, 853–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittermeier, R.A.; Myers, N.; Thomsen, J.B.; da Fonseca, G.A.B.; Olivieri, S. Biodiversity Hotspots and Major Tropical Wilderness Areas: Approaches to Setting Conservation Priorities. Conserv. Biol. 1998, 12, 516–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, J.; Greer, J.; Thorbecke, E. A Class of Decomposable Poverty Measures. Econometrica 1984, 52, 761–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INEC Encuesta Nacional de Empleo, Desempleo y Subempleo 2023 (ENEMDU) Available online:. Available online: https://scholar.google.es/scholar?hl=es&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Encuesta+Nacional+de+Empleo+%2C+Desempleo+y+Subempleo+2023+%28+ENEMDU+%29+&btnG= (accessed on Oct 27, 2024).

- Rivas, J.; Perea, J.M.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Angon, E.; Barba, C.; García, A. Canonical correlation of technological innovation and performance in sheep’s dairy farms: Selection of a set of indicators. Agric. Syst. 2019, 176, 102665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, A.; Rivas-Rangel, J.; Rangel-Quintos, J.; Espinosa, J.A.; Barba, C.; de-Pablos-Heredero, C. A methodological approach to evaluate livestock innovations on small-scale farms in developing countries. Futur. Internet 2016, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Eche, D.; Torres, Y.; Bravo, C.; Velasco, C.; García, A. Identification and assessment of livestock best management practices (BMPs) using the REED+ approach in the ecuadorian amazon. Agronomy 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEN Cuestionario prototipo PEN 2007, 1–25.

- Angelsen, A.; Larsen, H.O.; Lund, J.F.; Smith-hall, C.; Wunder, S. Measuring Livelihoods and Environmental Dependence; Angelsen, A. , Larsen, H.O., Lund, J.F., Smith-hall, C., Wunder, S., Eds.; First.; Earthscan: Washington D.C, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Martinez, A.; De-Pablos-heredero, C.; González, M.; Rodriguez, J.; Barba, C.; García, A. Morphological variations of wild populations of brycon dentex (Characidae, teleostei) in the guayas hydrographic basin (ecuador). the impact of fishing policies and environmental conditions. Animals 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caez, J.; Gonzalez, A.; González, M.A.; Angón, E.; Rodriguez, J.M.; Peña, F.; Barba, C.; Garcia, A. Application of multifactorial discriminant analysis in the morphostructural differentiation of wild and cultured populations of Vieja Azul (Andinoacara rivulatus). Turkish J. Zool. 2019, 43, 516–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, C.; Torres, B.; Pacheco, P.; Griess, V. The socioeconomic determinants of legal and illegal smallholder logging: Evidence from the Ecuadorian Amazon. For. Policy Econ. 2017, 78, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasco, C.; Bilsborrow, R.; Torres, B.; Griess, V. Agricultural land use among mestizo colonist and indigenous populations: Contrasting patterns in the Amazon. PLoS One 2018, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasco Pérez, C.; Bilsborrow, R.; Torres, B. Income diversification of migrant colonists vs. indigenous populations: Contrasting strategies in the Amazon. J. Rural Stud. 2015, 42, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, T.; Gray, C.L. Livelihood Diversification and Shifting Social Networks of Exchange : A Social Network Transition ? World Dev. 2014, 60, 14–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, R.; Tamayo Cordero, F.; Ojeda Luna, T.; Ferrer Velasco, R.; DeDecker, M.; Torres, B.; Giessen, L.; Günter, S. Interplay of governance elements and their effects on deforestation in tropical landscapes: Quantitative insights from Ecuador. World Dev. 2021, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Montes-Botella, J.L.; García, A. Impact of Technological Innovation on Performance in Dairy Sheep Farms in Spain; 2020; Vol. 22;

- Bastanchury-López, M.T.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Montes-Botella, J.L.; Martín-Romo-Romero, S.; García, A. Impact of dynamic capabilities on performance in dairy sheep farms in Spain. Sustain. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ochoa, C.P.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Jimenez, F.J.B. The role of business accelerators in generating dynamic capabilities within startups. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. Manag. 2022, 26, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulletin, S.M.-I.L.; 2001, U. Giving credit where it’s due: the operation of micro-credit models in an Indigenous Australian context. search.informit.orgS McDonnellIndigenous Law Bull. 2001•search.informit.org.

- Soni, B. MOVING BEYOND FEAR AND EGO-DRIVEN LEADERSHIP THROUGH THE YOGIC CHAKRA SYSTEM STATES OF CONSCIOUSNESS, 2021.

- Villarroel-Molina, O.; De-Pablos-Heredero, C.; Barba, C.; Rangel, J.; García, A. Does Gender Impact Technology Adoption in Dual-Purpose Cattle in Mexico? Animals 2022, 12, 3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, B.; Starnfeld, F.; Vargas, J.C.; Ramm, G.; Chapalbay, R.; Jurrius, I.; Gómez, A.; Torricelli, Y.; Tapia, A.; Shiguango, J.; et al. Gobernanza participativa en la Amazonía del Ecuador: recursos naturales y desarrollo sostenible; Universida.; Universidad Estatal Amazónica: Quito, 2014; ISBN 9789942932112. [Google Scholar]

- Boerner, J.; Shively, G.; Wunder, S.; Wyman, M. How Do Rural Households Cope with Economic Shocks? Insights from Global Data using Hierarchical Analysis. J. Agric. Econ. 2015, 66, 392–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walelign, S.Z. Getting stuck, falling behind or moving forward: Rural livelihood movements and persistence in Nepal. Land use policy 2017, 65, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phalan, B.; Onial, M.; Balmford, A.; Green, R.E. Reconciling food production and biodiversity conservation: Land sharing and land sparing compared. Science (80-. ). 2011, 333, 1289–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schroth, G.; Bede, L.C.; Paiva, A.O.; Cassano, C.R.; Amorim, A.M.; Faria, D.; Mariano-Neto, E.; Martini, A.M.Z.; Sambuichi, R.H.R.; Lôbo, R.N. Contribution of agroforests to landscape carbon storage. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2015, 20, 1175–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izurieta, G.; Torres, A.; Patiño, J.; Vasco, C.; Vasseur, L.; Reyes, H.; Torres, B. Exploring community and key stakeholders’ perception of scientific tourism as a strategy to achieve SDGs in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | Mean n=330 |

Kallari n=156 |

Wiñak n=129 |

Tsatsayaku n=45 |

sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | |||||

| Total income (USD) | 1652.73 | 1540.68 a | 1287.45 a | 3096.94 b | *** |

| Chakra income (USD) | 575.69 | 673.34 b | 487.38 a | 490.36 a | * |

| Other income (USD) | 565.54 | 305.12 a | 299.03 a | 2232.35 b | *** |

| Per-capita income (USD/annual) | 394.94 | 361.46 a | 324.07 a | 714.15 b | ** |

| Headcount index (% extremely poor) | 82 | 86.5 | 89.1 | 68.9 | n.s |

| SAFA – Themes – Indicators |

All n = 330 |

Kallari n = 156 |

Wiñak n = 129 |

Tsatsayaku n = 45 |

Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Godd governance (14) | G1.1.1 | Mission Explicitness | 3.08 | 3.21 b | 3.27 b | 2.09 a | *** |

| G1.1.2 | Mission Driven | 3.07 | 3.20 b | 3.25 b | 2.13 a | *** | |

| G1.2.1 | Due Diligence | 3.03 | 3.10 b | 3.25 b | 2.18 a | *** | |

| G2.1.1 | Holistic Audits | 3.11 | 3.14 b | 3.40 b | 2.18 a | *** | |

| G2.2.1 | Responsibility | 3.02 | 3.03 b | 3.33 b | 2.11 a | *** | |

| G2.3.1 | Transparency | 3.05 | 3.08 b | 3.32 b | 2.13 a | *** | |

| G3.1.1 | Stakeholder Identification | 3.23 | 3.28 b | 3.46 b | 2.38 a | *** | |

| G3.1.2 | Stakeholder Engagement | 3.25 | 3.24 b | 3.48 b | 2.60 a | *** | |

| G3.1.4 | Effective Participation | 3.05 | 3.13 b | 3.13 b | 2.51 a | ** | |

| G3.2.1 | Grievance Procedures | 3.11 | 3.27 b | 3.09 b | 2.64 a | ** | |

| G4.2.1 | Remedy, Restoration and Prevention | 3.34 | 3.32 a, b | 3.52 b | 2.87 a | * | |

| G4.3.1 | Responsibility | 3.19 | 3.03 a, b | 3.48 b | 2.91 a | *** | |

| G5.1.1 | Sustainability Management Plan | 3.38 | 3.50 b | 3.53 b | 2.51 a | *** | |

| G5.2.1 | Full-Cost Accounting | 3.18 | 3.33 b | 3.22 b | 2.56 a | *** | |

| Ennvironmental integrity (15) | E1.1.1 | GHG Reduction Target | 3.48 | 3.68 b | 3.44 b | 2.91 a | *** |

| E1.1.2 | GHG Mitigation Practices | 3.58 | 3.70 b | 3.57 a, b | 3.20 a | * | |

| E2.1.2 | Water Conservation Practices | 3.26 | 3.10 a | 3.27 a, b | 3.78 b | * | |

| E2.2.2 | Water Pollution Prevention Practices | 4.14 | 4.31 b | 4.04 a, b | 3.87 a | * | |

| E3.2.1 | Land Conservation and Rehabilitation Plan | 3.68 | 3.86 b | 3.66 b | 3.13 a | *** | |

| E3.2.2 | Land Conservation and Rehabilitation Practices | 3.86 | 3.92 b | 4.00 b | 3.29 a | *** | |

| E4.1.4 | Ecosystem Connectivity | 3.96 | 4.06 b | 3.98 b | 3.53 a | ** | |

| E4.1.5 | Land-Use and Land-Cover Change | 3.78 | 3.96 b | 3.76 b | 3.27 | *** | |

| E4.2.2 | Species Conservation Practices | 3.83 | 4.01 b | 3.79 b | 3.31 a | *** | |

| E4.2.3 | Diversity and Abundance of Key Species | 3.94 | 4.09 b | 3.96 b | 3.33 a | ** | |

| E4.2.4 | Diversity of Production | 4.00 | 4.14 b | 4.01 b | 3.49 a | *** | |

| E4.3.1 | Wild Genetic Diversity Enhancing Practices | 4.06 | 4.10 b | 4.19 b | 3.51 a | *** | |

| E4.3.2 | Agro-Biodiversity in-situ Conservation | 4.07 | 4.10 b | 4.14 b | 3.73 a | * | |

| E5.2.1 | Renewable Energy Use Target | 2.43 | 2.62 b | 2.40 b | 1.87 a | *** | |

| E5.2.2 | Energy-Saving Practices | 2.39 | 2.63 b | 2.32 b | 1.73 a | *** | |

| Economic resilience (11) | C1.2.1 | Community Investment | 3.47 | 3.62 b | 3.39 a, b | 3.20 a | * |

| C1.3.1 | Long Term Profitability | 3.23 | 3.40 b | 3.16 a, b | 2.82 a | ** | |

| C1.3.2 | Business Plan | 3.15 | 3.42 c | 3.05 b | 2.51 a | *** | |

| C1.4.1 | Net Income | 3.19 | 3.40 b | 3.06 a, b | 2.82 a | *** | |

| C1.4.2 | Cost of Production | 3.15 | 3.36 b | 3.03 a, b | 2.80 a | *** | |

| C1.4.3 | Price Determination | 3.26 | 3.44 b | 3.12 a, b | 3.09 a | ** | |

| C2.1.2 | Product Diversification | 3.59 | 3.67 b | 3.67 b | 3.09 a | ** | |

| C2.3.1 | Stability of Market | 3.09 | 3.22 b | 3.10 b | 2.64 a | ** | |

| C2.4.1 | Net Cash Flow | 3.09 | 3.25 b | 3.08 b | 2.60 a | *** | |

| C2.4.2 | Safety Nets | 2.96 | 3.17 b | 2.93 b | 2.31 a | *** | |

| C2.5.1 | Risk Management | 3.31 | 3.47 b | 3.22 a, b | 2.96 a | * | |

| Social well-being (4) |

S2.1.1 | Fair Pricing and Transparent Contracts | 3.30 | 3.45 b | 3.29 b | 2.82 a | *** |

| S5.1.1 | Safety and Health Training | 3.47 | 3.74 b | 3.36 a, b | 2.84 a | *** | |

| S5.2.1 | Public Health | 4.19 | 4.12 a | 4.24 b | 4.29 b | *** | |

| S6.1.1 | Indigenous Knowledge | 4.26 | 4.44 b | 4.36 b | 4.21 a | *** |

| No. | Parameters 1 | Wilks’ - Lambda | Partial - Lambda | F-remove | p-level 2 | Toler | 1-Toler |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | L-PhC.1 | 0.39 | 0.88 | 20.30 | *** | 0.90 | 0.10 |

| 2 | L-NC.1 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 2.50 | * | 0.04 | 0.96 |

| 3 | C1.3.2 | 0.35 | 0.97 | 4.23 | ** | 0.52 | 0.48 |

| 4 | E2.1.2 | 0.36 | 0.94 | 8.98 | *** | 0.72 | 0.28 |

| 5 | L-HC.1 | 0.36 | 0.96 | 5.92 | *** | 0.90 | 0.10 |

| 6 | E2.2.2 | 0.36 | 0.95 | 7.25 | *** | 0.54 | 0.46 |

| 7 | L-HC.2 | 0.35 | 0.97 | 4.12 | *** | 0.79 | 0.21 |

| 8 | C2.4.2 | 0.35 | 0.97 | 4.28 | ** | 0.32 | 0.68 |

| 9 | C1.4.3 | 0.35 | 0.97 | 4.91 | ** | 0.54 | 0.46 |

| 10 | S5.2.1 | 0.35 | 0.97 | 5.06 | ** | 0.62 | 0.38 |

| 11 | S5.1.1 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 3.16 | * | 0.72 | 0.28 |

| 12 | E4.3.1 | 0.35 | 0.97 | 4.91 | ** | 0.19 | 0.81 |

| 13 | L-FC.1 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 3.42 | ** | 0.74 | 0.26 |

| 14 | E4.3.2 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 3.38 | * | 0.22 | 0.78 |

| 15 | L-FC.2 | 0.35 | 0.97 | 4.06 | ** | 0.79 | 0.21 |

| 16 | L-FC.3 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 3.28 | * | 0.83 | 0.17 |

| 17 | G4.3.1 | 0.36 | 0.96 | 6.95 | *** | 0.40 | 0.60 |

| 18 | G5.2.1 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 3.01 | * | 0.73 | 0.27 |

| 19 | G2.1.1 | 0.35 | 0.98 | 3.68 | ** | 0.34 | 0.66 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).