Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

31 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Study design

2.3. Isolated ex-vivo reperfusion model

2.4. Biochemistry

2.5. Histopathological Evaluation

2.6. Gene expression

2.7. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. BUN, Cr, CPK, LDH, And Lactate in the Perfusate Solution

3.2. Histological Observations During Reperfusion

3.2.1. Hematoxylin–Eosin Staining

3.2.2. ERG and CD42b Immunohistochemistry

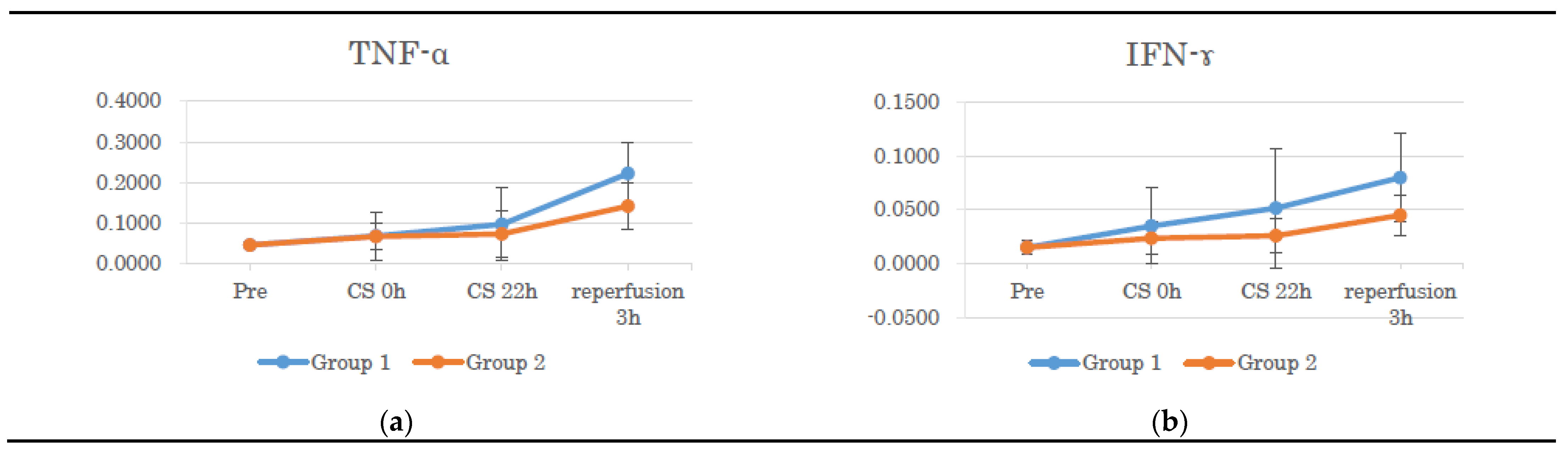

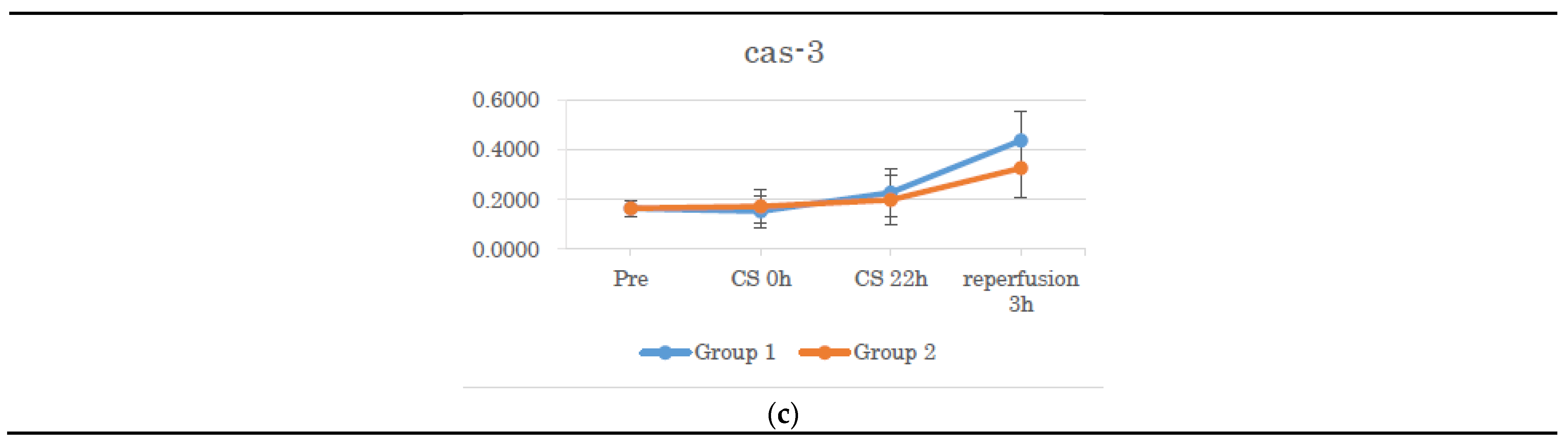

3.3. Gene Expression

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Southard, J.H.; Belzer, F.O. Organ preservation. Annu Rev Med 1995, 46, 235–247. [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.M.; Zheng, Y.L.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Z.F.; Fan, S.H.; Wu, D.M.; Ma, J.Q. Quercetin protects rat liver against lead-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 2010, 29, 158–166. [CrossRef]

- Zielińska, M.; Kostrzewa, A.; Ignatowicz, E.; Budzianowski, J. The flavonoids, quercetin and isorhamnetin 3-O-acylglucosides diminish neutrophil oxidative metabolism and lipid peroxidation. Acta Biochim Pol 2001, 48, 183–189.

- Kinaci, M.K.; Erkasap, N.; Kucuk, A.; Koken, T.; Tosun, M. Effects of quercetin on apoptosis, NF-κB and NOS gene expression in renal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Exp Ther Med 2012, 3, 249–254. [CrossRef]

- Ahlenstiel, T.; Burkhardt, G.; Köhler, H.; Kuhlmann, M.K. Bioflavonoids attenuate renal proximal tubular cell injury during cold preservation in Euro-Collins and University of Wisconsin solutions. Kidney Int 2003, 63, 554–563. [CrossRef]

- Kumano, K.; Wang, W.; Endo, T. [Effects of osmotic agents for cold kidney preservation.] Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 1994, 85, 925–931. [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzo, V.R.; Cescon, M.; Odaldi, F.; Di Laudo, M.; Cucchetti, A.; Ravaioli, M.; Del Gaudio, M.; Ercolani, G.; D'Errico, A.; Pinna, A.D. Actual risk of using very aged donors for unselected liver transplant candidates: a European single-center experience in the MELD era. Ann Surg 2017, 265, 388–396. [CrossRef]

- Flores, A.; Asrani, S.K. The donor risk index: a decade of experience. Liver Transpl 2017, 23, 1216–1225. [CrossRef]

- Hoyer, D.P.; Paul, A.; Gallinat, A.; Molmenti, E.P.; Reinhardt, R.; Minor, T.; Saner, F.H.; Canbay, A.; Treckmann, J.W.; Sotiropoulos, G.C.; Mathé, Z. Donor information based prediction of early allograft dysfunction and outcome in liver transplantation. Liver Int 2015, 35, 156–163. [CrossRef]

- Agopian, V.G.; Petrowsky, H.; Kaldas, F.M.; Zarrinpar, A.; Farmer, D.G.; Yersiz, H.; Holt, C.; Harlander-Locke, M.; Hong, J.C.; Rana, A.R.; Venick, R.; McDiarmid, S.V.; Goldstein, L.I.; Durazo, F.; Saab, S.; Han, S.; Xia, V.; Hiatt, J.R.; Busuttil, R.W. The evolution of liver transplantation during 3 decades: analysis of 5347 consecutive liver transplants at a single center. Ann Surg 2013, 258, 409–421. [CrossRef]

- Elahi, M.M.; Kong, Y.X.; Matata, B.M. Oxidative stress as a mediator of cardiovascular disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2009, 2, 259–269. [CrossRef]

- Kaçmaz, A.; Polat, A.; User, Y.; Tilki, M.; Ozkan, S.; Sener, G. Octreotide: a new approach to the management of acute abdominal hypertension. Peptides 2003, 24, 1381–1386. [CrossRef]

- Salahudeen, A.K.; Huang, H.; Patel, P.; Jenkins, J.K. Mechanism and prevention of cold storage-induced human renal tubular cell injury. Transplantation 2000, 70, 1424–1431. [CrossRef]

- Heijnen, C.G.M.; Haenen, G.R.M.M.; Oostveen, R.M.; Stalpers, E.M.; Bast, A. Protection of flavonoids against lipid peroxidation: the structure activity relationship revisited. Free Radic Res 2002, 36, 575–581. [CrossRef]

- Seok, Y.M.; Kim, J.; Park, M.J.; Boo, Y.C.; Park, Y.K.; Park, K.M. Wen-pi-tang-Hab-Wu-ling-san attenuates kidney fibrosis induced by ischemia/reperfusion in mice. Phytother Res 2008, 22, 1057–1063. [CrossRef]

- Spandou, E.; Tsouchnikas, I.; Karkavelas, G.; Dounousi, E.; Simeonidou, C.; Guiba-Tziampiri, O.; Tsakiris, D. Erythropoietin attenuates renal injury in experimental acute renal failure ischaemic/reperfusion model. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006, 21, 330–336. [CrossRef]

- Inal, M.; Altinişik, M.; Bilgin, M.D. The effect of quercetin on renal ischemia and reperfusion injury in the rat. Cell Biochem Funct 2002, 20, 291–296. [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, N.; Pratt, J.R.; Potts, D.J.; Lodge, J.P.A. Comparative efficacy of renal preservation solutions to limit functional impairment after warm ischemic injury. Kidney Int 2006, 69, 884–893. [CrossRef]

- Kato, F.; Gochi, M.; Kawagoe, T.; Yotsuya, S.; Matsuno, N. The protective effects of quercetin and sucrose on cold preservation injury in vitro and in vivo. Organ Biology 2020, 27, 207–215. [CrossRef]

- Gochi, M.; Kato, F.; Toriumi, A.; Kawagoe, T.; Yotsuya, S.; Ishii, D.; Otani, M.; Nishikawa, Y.; Furukawa, H.; Matsuno, N. A novel preservation solution containing quercetin and sucrose for porcine kidney transplantation. Transplant Direct 2020, 6, e624. [CrossRef]

- Soares, B.L.F.; de Freitas, M.A.L.; Montero, E.F.S.; Pitta, G.B.B.; Miranda, F., Jr. Alprostadil attenuates inflammatory aspects and leucocytes adhesion on renal ischemia and reperfusion injury in rats. Acta Cir Bras 2014, 29 Suppl 2, 55–60. [CrossRef]

- Ahlenstiel, T.; Burkhardt, G.; Köhler, H.; Kuhlmann, M.K. Improved cold preservation of kidney tubular cells by means of adding bioflavonoids to organ preservation solutions. Transplantation 2006, 81, 231–239. [CrossRef]

- Cardinal, H.; Dieudé, M.; Hébert, M.J. Endothelial dysfunction in kidney transplantation. Front Immunol 2018, 9, 1130. [CrossRef]

- Jansen, M.P.B.; Emal, D.; Teske, G.J.D.; Dessing, M.C.; Florquin, S.; Roelofs, J.J.T.H. Release of extracellular DNA influences renal ischemia reperfusion injury by platelet activation and formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Kidney Int 2017, 91, 352–364. [CrossRef]

- Kinsey, G.R.; Li, L.; Okusa, M.D. Inflammation in acute kidney injury. Nephron Exp Nephrol 2008, 109, e102–e107. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Swaminathan, S.; Bachman, L.A.; Croatt, A.J.; Nath, K.A.; Griffin, M.D. Resident dendritic cells are the predominant TNF-secreting cell in early renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Kidney Int 2007, 71, 619–628. [CrossRef]

- Donnahoo, K.K.; Meng, X.; Ayala, A.; Cain, M.P.; Harken, A.H.; Meldrum, D.R. Early kidney TNF-alpha expression mediates neutrophil infiltration and injury after renal ischemia-reperfusion. Am J Physiol 1999, 277, R922–R929. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lan, S.; Dieudé, M.; Sabo-Vatasescu, J.P.; Karakeussian-Rimbaud, A.; Turgeon, J.; Qi, S.; Gunaratnam, L.; Patey, N.; Hébert, M.J. Caspase-3 is a pivotal regulator of microvascular rarefaction and renal fibrosis after ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Am Soc Nephrol 2018, 29, 1900–1916. [CrossRef]

| Primer | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | AGGAGTAAGAGCCCCTGGAC | GTGTGTTGGGGGATCGAGT |

| TNF-α | TTGTCGCTACATCGCTGAAC | CCAGTAGGGCGGTTACAGAC |

| IFN-γ | TTCAGCTTTGCGTGACTTTG | TGCATTAAAATAGTCCTTTAGGATCG |

| Caspase-3 | GAATGGCATGTCGATCTGGT | TTGTGAAGGTCTCCCTGAGATT |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).