Submitted:

30 October 2024

Posted:

31 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Location

2.2. Data Source2.3. Data Analysis

2.3.1. Exploratory Analysis

2.4. An Analysis of the Impact of the Pandemic on Suicides in Brazil Using Interrupted Time Series

2.6. Ethical Aspects

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Bivariate Analyses

3.3. An Analysis of the Impact of the Pandemic on Suicides in Brazil Using Interrupted Time Series

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Word Health Organization. Suicide worldwide in 2019: global health estimates. Geneva: WHO, 2021.

- BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. Panorama de suicídios e lesões autoprovocadas no Brasil de 2010 a 2021. Boletim Epidemiológico, 2024, Brasília, DF, v. 55. Avaliable in: <https://www.gov.br/saude/ptbr/media/pdf/2021/setembro/20/boletim_epidemiologico_svs_33_final.pdf>. Access in: September 10, 2024.

- Cheung, Y. T.; Chau, P. H.; Yip, P. S.F. A revisit on older adults’ suicides and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in Hong Kong. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2008, 23, 1231–1238. [CrossRef]

- Basta, Maria; Vgontzas, A. N.; Bixler, E. O.; Kales, A. Suicide rates in Crete, Greece during the economic crisis: the effect of age, gender, unemployment and mental health service provision.BMC Psychiatry.2018, 1, 56. [CrossRef]

- Botega, Neury José. Comportamento suicida: epidemiologia.Psicologia USP. 2014, 25, 231-236. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Hao; Chen, Jianbo; Xu, Yifeng. Patients with mental health disorders in the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry.2020, 7, e21. September 10, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Gunnell, David et al. Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry.2020, 7,468-471. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, Debanjan; Kosagisharaf, Jishnu R.; Rao, T. S. Sathyanarayana. *‘The dual pandemic’ of suicide and COVID-19: A biopsychosocial narrative of risks and prevention.Psychiatry Res.2021, 295, 113577. [CrossRef]

- Souza, Alex Sandro Rolland et al. Factors associated with stress, anxiety, and depression during social distancing in Brazil. Rev. Saúde Pública.2021, 55,5. [CrossRef]

- Armitage, Richard et al. COVID-19 and the consequences of isolating the elderly.Lancet Public Health.2020, 5, e256. [CrossRef]

- Devitt, Patrick. Can we expect an increased suicide rate due to Covid-19? Irish J. Psychol. Med.2020, 37, 264–268. [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, B.; Al-Jumaily, A.; Fong, K. N. K.; Prasad, P.; Meena, S. K.; Tong, R. K.-Y. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak quarantine, isolation, and lockdown policies on mental health and suicide.Front Psychiatry.2021,12,565190. [CrossRef]

- Moyer, Jonathan D.; Verhagen, Wouter; Mapes, Brian; Bohl, Douglas K.; Xiong, Yiming; Yang, Vivian W.; McNeil, Kate; Solórzano, Javier; Irfan, Muhammad; Carter, Charles; Hughes, Barry B. How many people is the COVID-19 pandemic pushing into poverty? A long-term forecast to 2050 with alternative scenarios.PLoS One. 2022,17, 7,e0270846. [CrossRef]

- McGowan, Victoria J.; Bambra, Clare. COVID-19 mortality and deprivation: pandemic, syndemic, and endemic health inequalities.Lancet Public Health. 2022, 7, e966-e975. [CrossRef]

- Munford, Luke; Khavandi, Shoaib; Bambra, Clare et al. A year of COVID-19 in the North: regional inequalities in health and economic outcomes. Northern Health Science Alliance, 2021. Avaliable in: https://www.thenhsa.co.uk/app/uploads/2021/09/COVID-REPORT-2021-EMBARGO.pdf.Acess in: September 1, 2024.

- Bastos, Leonardo S.; Ranzani, Otavio T.; Souza, Tamires M. L.; Hamacher, Silvio; Bozza, Felipe A. COVID-19 hospital admissions: Brazil’s first and second waves compared.Lancet Respir Med.2021, 9, e82–e83. [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall E. Syndemics: a new path for global health research. Lancet 2017; 389:889-91.

- Guimarães, Roberto Manoel. Suicide as a response for economic crisis: A call for action in Brazil.Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry. 2024, 70, 4, 830-831. [CrossRef]

- Appleby, Louis; Richards, Nicola; Ibrahim, Saied; Turnbull, Philippa; Rodway, Cathryn; Kapur, Navneet. Suicide in England in the COVID-19 pandemic: Early observational data from real-time surveillance. Lancet Reg. Health Eur. 2021, 4,100110. [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, R. S.; Lui, L. M.; Rosenblat, J. D.; Ho, R.; Gill, H.; Mansur, R. B.; Teopiz, K.; Liao, Y.; Lu, C.; Subramaniapillai, M.; Nasri, F.; Lee, Y. Suicide reduction in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons informing national prevention strategies for suicide reduction.J. R. Soc. Med.2021, 114, 473–479. [CrossRef]

- Pirkis, J.; John, A.; Shin, S.; DelPozo-Banos, M.; Arya, V.; Analuisa-Aguilar, P.; Appleby, L.; Arensman, E.; Bantjes, J.; Baran, A.; Bertolote, J. M.; Borges, G.; Brečić, P.; Caine, E.; Castelpietra, G.; Chang, S.-S.; Colchester, D.; Crompton, D.; Curkovic, M.; ... Spittal, M. J. Suicide trends in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic: An interrupted time-series analysis of preliminary data from 21 countries. Lancet Psychiatry.2021, 8,579–588. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Okamoto, S. Increase in suicide following an initial decline during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan.Nat. Hum. Behav.2021, 5, 229-238. [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y. H.; Chang, S. S.; Hsu, C. Y.; Gunnell, D. *Impact of Pandemic on Suicide: Excess Suicides in Taiwan During the 1918-1920 Influenza Pandemic.J. Clin. Psychiatry.2020, 81, 20l13454. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.; Subedi, K.; Acharya, P.; Ghimire, S. Association between COVID-19 pandemic and the suicide rates in Nepal.PLoS One.2022,17,e0262958. [CrossRef]

- Ornell, F.; Benzano, D.; Borelli, W. V.; Narvaez, J. C. M.; Moura, H. F.; Passos, I. C.; Sordi, A. O.; Schuch, J. B.; Kessler, F. H. P.; Scherer, J. N.; von Diemen, L. Differential impact on suicide mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in Brazil. Braz. J. Psychiatry.2022, 44, 628-634. [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, E. O Suicídio: estudo de sociologia. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 2019.

- Salib, E. Effect of 11 September 2001 on suicide and homicide in England and Wales.Br. J. Psychiatry.2003, 183, 207–212. PMID: 12948992. [CrossRef]

- Salib, E.; Cortina-Borja, M. Effect of 7 July 2005 terrorist attacks in London on suicide in England.Br. J. Psychiatry.2009, 194, 80–85. [CrossRef]

- Claassen, C. A.; Carmody, T.; Stewart, S. M.; Bossarte, R. M.; Larkin, G. L.; Woodward, W. A.; Trivedi, M. H. Effect of 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks in the USA on suicide in areas surrounding the crash sites.Br. J. Psychiatry.2010, 196, 359–364. [CrossRef]

- Mak, I. W. C.; Chu, C. M.; Pan, P. C.; Yiu, M. G. C.; Chan, V. L. Long-term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors.Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry.2009, 31,318–326. [CrossRef]

- Orellana, J. D. Y.; de Souza, M. L. P. Excess suicides in Brazil: Inequalities according to age groups and regions during the COVID-19 pandemic.Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry.2022, v. 68, n. 5, p. 997-1009. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-Y.; Yang, C.-T.; Pinkney, E.; Yip, P. S. F.Suicide trends varied by age-subgroups during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 in Taiwan.J. Formosan Med. Assoc.2021.121,1174-1177. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Ueda, M.; Nordström, R.; Matsubayashi, T. Suicide and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. J. Public Health.2022.25,541-548. [CrossRef]

- Orellana, J. D. Y.; de Souza, M. L. P.; Horta, B. L. Excess suicides in Brazil during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic: Gender, regional and age group inequalities. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry.2024, 70, 99-112. [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Oh, J.; Kim, S. I.; Kang, C.; Ha, E.; Kim, H.; Lee, W. Excess suicide attributable to the COVID-19 pandemic and social disparities in South Korea.Sci. Rep.2022, 12, 18390. [CrossRef]

- The Lancet. COVID-19 in Brazil: “So what?”.Lancet.2020, 395, 1461. [CrossRef]

- Ventura, D.; Aith, F.; Reis, R. Crimes against humanity in Brazil’s COVID-19 response - A lesson to us all.BMJ,2021, 375,2625. [CrossRef]

- Bispo Júnior, J. P.; Santos, D. B. D. COVID-19 as a syndemic: A theoretical model and foundations for a comprehensive approach in health.Cad. Saúde Pública.2021,37, e00119021. [CrossRef]

- Soares, F. C.; Stahnke, D. N.; Levandowski, M. L. Tendência de suicídio no Brasil de 2011 a 2020: foco especial na pandemia de covid-19 [Trends in suicide rates in Brazil from 2011 to 2020: special focus on the COVID-19 pandemic]Rev. Panam. Salud Publica.2022, 46, e212. [CrossRef]

- Beautrais, A. L. Women and suicidal behavior.Crisis.2006, 27, 153-156.

- Shelef, L. The Gender Paradox: Do Men Differ from Women in Suicidal Behavior?J. Mens Health.2021, 17, 22-29. [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L. J. Suicide in cultural context: An ecosocial approach. Transcult. Psychiatry.2022, 59, 3–12. [CrossRef]

- Scott, J. W. Gender: a Useful Category of Historical Analysis.Am. Hist. Rev.1988, 91, 1053-1075.

- Zanello, V. Saúde Mental, Gênero e Dispositivos: cultura e processos de subjetivação. Curitiba: Appris Editora 2018. 301p.

- Canetto, S. S.; Sakinofsky, I. The gender paradox in suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1998, 28, 1-23. PMID: 9560163.

- Canetto, S. S. Women and suicidal behavior: a cultural analysis.Am. J. Orthopsychiatry.2008, 78, 259-266. [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, K. The gender-ing of suicide. Aust. Fem. Stud.2010, 25, 47-61. [CrossRef]

- Meneghel, S. N.; Gutierez, D. M. D.; Silva, R. M.; Grubits, S.; Hesler, L. Z.; Ceccon, R. F. Suicide in the elderly from a gender perspective.Ciênc. Saúde Colet. 2012, 17,1983–1992. [CrossRef]

- Stevens, G. A.; Alkema, L.; Black, R. E.; et al. Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting: the GATHER statement. Lancet.2016, 388, e19-23. [CrossRef]

- IBGE - Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Estimativas de população enviadas ao TCU. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE 2021. Avaliable in:<https://ftp.ibge.gov.br/Estimativas_de_Populacao/Estimativas_2021/POP2021_20230710.pdf.

- Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde, Ministério da Saúde, Brasil. Sistema de Informação Sobre Mortalidade. Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil 2024. Avaliable in: <http://www2.datasus.gov.br/DATASUS/index.php?area=0205> . Acess in: April 30,2024.

- Instituto de Pesquisas Econômicas e Aplicadas, Brasil. O Retrato das Desigualdades de Gênero e Raça.2024. Avaliable in https://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/retrato/indicadores/fontes-e-metadados. Acess in: May 15,2024.

- Mathers, C. D.; Bernard, C.; Iburg, K. M.; Inoue, M.; Fat, D. M.; Shibuya, K.; Stein, C.; Tomijima, N.; Xu, H. Global burden of disease in 2002: Data sources, methods and results.Glob. Programme Evid. Health Policy Disc. Pap.2004, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

- Triola, M. F. Estatística. 13ª ed. São Paulo: Pearson **2018**.

- Morettin, P. A.; Toloi, C. M. Análise de séries temporais. 2ª ed. São Paulo: Blucher 2006. 564p.

- Bernal, J. L.; Cummins, S.; Gasparrini, A.; Artundo, C.; McKee, M. The effect of the late 2000s financial crisis on suicides in Spain: an interrupted time series analysis.Eur. J. Public Health. 2013, 23, 732–736. [CrossRef]

- Shadish, W. R.; Cook, T. D.; Campbell, D. T. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.2002.

- Biglan, A.; Ary, D.; Wagenaar, A. C. The value of interrupted time series experiments for community intervention research.Prev. Sci.2000, 1, 31-49. [CrossRef]

- Kontopantelis, E.; Doran, T.; Springate, D. A.; Buchan, I.; Reeves, D. Regression based quasi-experimental approach when randomisation is not an option: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ.2015, 350, h2750. [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, D. C. M. M.; Sanchéz-Villegas, P.; Figueiredo, A. M.; Moraes, R. M.; Daponte-Codina, A.; Schmidt Filho, R.; Vianna, R. P. T. Effects of the economic recession on suicide mortality in Brazil: interrupted time series analysis.Rev. Bras. Enferm.2022, 75 (Suppl. 3), e20210778. [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, M. I.; Massahud, F. C.; Barbosa, N. G.; Lopes, C. D.; Rodrigues, V. C. Mortalidade prematura por câncer de colo uterino: estudo de séries temporais interrompidas. Rev. Saúde Pública.2020, 54, 139. [CrossRef]

- Wagner, A. K.; Soumerai, S. B.; Zhang, F.; Ross-Degnan, D. Segmented regression analysis of interrupted time series studies in medication use research.J. Clin. Pharm. Ther.2002, 27, 299-309. [CrossRef]

- Bernal, J. L.; Cummins, S.; Gasparrini, A. Corrigendum to: Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial.Int. J. Epidemiol.2021, 50, 1045. [CrossRef]

- Durbin, J.; Watson, G. S. Testing for serial correlation in least squares regression.Biometrika. 1951, 38, 159-178. PMID: 14848121.

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria 2013.Avaliable in: <https://www.R-project.org/> . Access in: January15,2024.

- Conselho Nacional de Saúde (BR). Resolução nº 510, de 7 de abril de 2016. 2016. Avaliable in:<http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/2016/res0510_07_04_2016.html>. Access in: January15,2024.

- Rodrigues, C. D.; Souza, D. S.; Rodrigues, H. M.; Konstantyner, T. C. R. O. Trends in suicide rates in Brazil from 1997 to 2015. Braz. J. Psychiatry.2019, 41,380–388. [CrossRef]

- Galvão, P. V. M.; da Silva, C. M. F. P. Analysis of age, period, and birth cohort effects on suicide mortality in Brazil and the five major geographic regions.BMC Public Health.2023, 23, 1351. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, W. T. D. S.; Simões, T. C.; Magnago, C.; Dantas, E. S. O.; Guimarães, R. M.; Jesus, J. C.; de Andrade Fernandes, S. M. B.; Meira, K. C. The influence of the age-period-cohort effects on male suicide in Brazil from 1980 to 2019.PLoS One.2023, 18, e0284224. [CrossRef]

- Meneghel, S. N.; Moura, R. Suicídio, cultura e trabalho em município de colonização alemã no sul do Brasil.Interface.2018, v.22, 1135-1146. [CrossRef]

- Palma, D. C. A.; Oliveira, B. F. A.; Ignotti, E. Suicide rates between men and women in Brazil, 2000-2017.Cad. Saúde Pública.2021, 37, e00281020. [CrossRef]

- Meneghel, S. N.; Danilevicz, I. M.; Polidoro, M.; Plentz, L. M.; Meneghetti, B. P. Femicide in borderline Brazilian municipalities.Ciênc. Saúde Colet.2020, 27, p. 493–502. [CrossRef]

- Martins, J. S. Fronteira: a degradação do outro nos confins do humano. São Paulo: Contexto 2009.

- López, M. V.; Pastor, M. P.; Giraldo, C. A.; García, H. I. Delimitación de fronteras como estrategia de control social: el caso de la violencia homicida en Medellín, Colombia. Salud Colectiva.2014, 10,397-406. [CrossRef]

- Jafari, H.; Heidari, M.; Heidari, S.; Sayfouri, N. Risk Factors for Suicidal Behaviours after Natural Disasters: A Systematic Review.Malays J. Med. Sci.2020, 27, 20-33. [CrossRef]

- Sinyor, M.; Knipe, D.; Borges, G.; Ueda, M.; Pirkis, J.; Phillips, M.R.; Gunnell, D. Suicide Risk and Prevention During the COVID-19 Pandemic: One Year On. Arch. Suicide Res. 2022, 26, 1944-1949. [CrossRef]

- Rahimi-Ardabili, H.; Feng, X.; Nguyen, P. Y.; Astell-Burt, T. Have Deaths of Despair Risen during the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Systematic Review.Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health.2022, v. 19, 12835. [CrossRef]

- Gelezelyte, O.; Dragan, M.; Grajewski, P.; Kvedaraite, M.; Lotzin, A.; Skrodzka, M.; Nomeikaite, A.; Kazlauskas, E. Factors Associated With Suicide Ideation in Lithuania and Poland Amid the COVID-19 Pandemic.Crisis.2022, 43, 460-467. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, R. M.; Oliveira, M. P. R. P. B.; Dutra, V. G. P. Excesso de mortalidade segundo grupo de causas no primeiro ano de pandemia de COVID-19 no Brasil.Rev. Bras. Epidemiol. 2022, 25, e220029. [CrossRef]

- Feijó, J.; Peruchetti, P. Recuperação do mercado de trabalho nas regiões brasileiras ainda desperta preocupação. Available in: <https://www18.fgv.br/mailing/2022/ibre/boletim-macro-maio/26/>. 2022. Acess in: June 10 ,2024.

- Barbosa, J. P. M.; Moreira, L. R. de C.; Santos, G. B. M.; Lanna, S. D.; Andrade, M. A. C. Interseccionalidade e violência contra as mulheres em tempos de pandemia de covid-19: diálogos e possibilidades.Saúde Soc.2021, 30, e200367. [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, C. F. M.; Vidal, E. C. F.; Kerntopf, M. R.; Lima Júnior, C. M.; Alves, M. N. T.; Carvalho, M. G.. Violência contra as mulheres na pandemia do COVID-19: um estudo sobre casos durante o período de quarentena no Brasil.Rev. Multidiscip. Psicol.2020, 14, 474-485. [CrossRef]

- BRASIL. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. Atlas da violência 2021. Rio de Janeiro: IPEA 2021.

- BRASIL. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. Atlas da violência 2023. Rio de Janeiro: IPEA 2023.

- Minayo, M. C. S.; Cavalcante, F. G. Estudo compreensivo sobre suicídio de mulheres idosas de sete cidades brasileiras.Cad. Saúde Pública.2013, 29, 2405-2415. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. A.; et al. The association between satisfaction with husband's participation in housework and suicidal ideation among married working women in Korea.Psychiatry Res. 2018, 261, 541-546. [CrossRef]

- Meneghel, S. N.; et al. Tentativa de suicídio em mulheres idosas – uma perspectiva de gênero.Ciênc. Saúde Colet.2015, 20,1721-1730.

- Baére, F.; Zanello, V. Suicídio e masculinidades: uma análise por meio do gênero e das sexualidades.Psicol. Estud.2020, 25, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Guimarães, R.M.; Meira, K.C.; da Silva Vicente, C.T.; de Araújo Caribé, S.S.; da Silva Neves, L.B.; Vardiero, N.A. The Role of Race in Deaths of Despair in Brazil: Is it a White People Problem? J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparities 2024. Epub ahead of print. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)a | p-value | Mean (SD)a | p-value | |

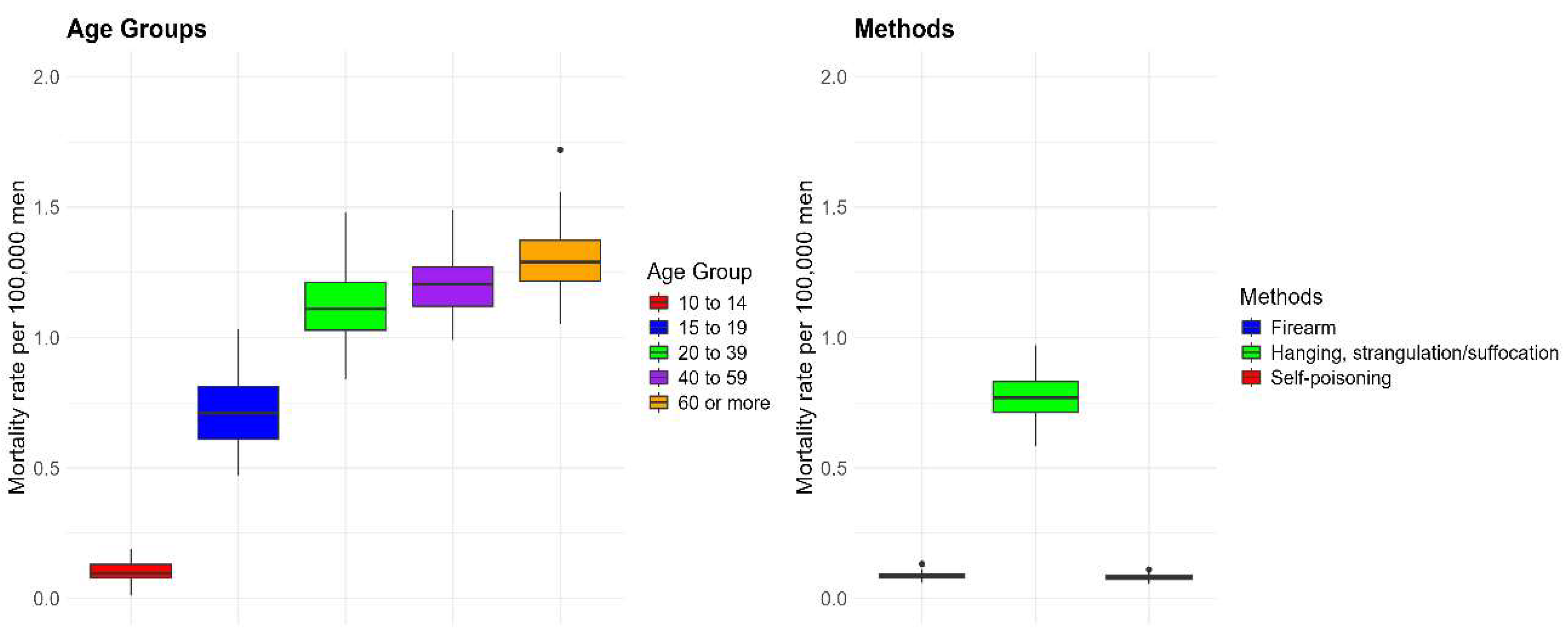

| Age group (age)b | ||||

| 10 to 14 | 0.098 (0.039) | <0.001 | 0.109 (0.042) | <0.001 |

| 15 to 19 | 0.713 (0.134) | 0.313 (0.074) | ||

| 20 to 39 | 1.125 (0.148) | 0.282 (0.049) | ||

| 40 to 59 | 1.212 (0.121) | 0.308 (0.041) | ||

| 60 or more | 1.302 (0.131) | 0.249 (0.047) | ||

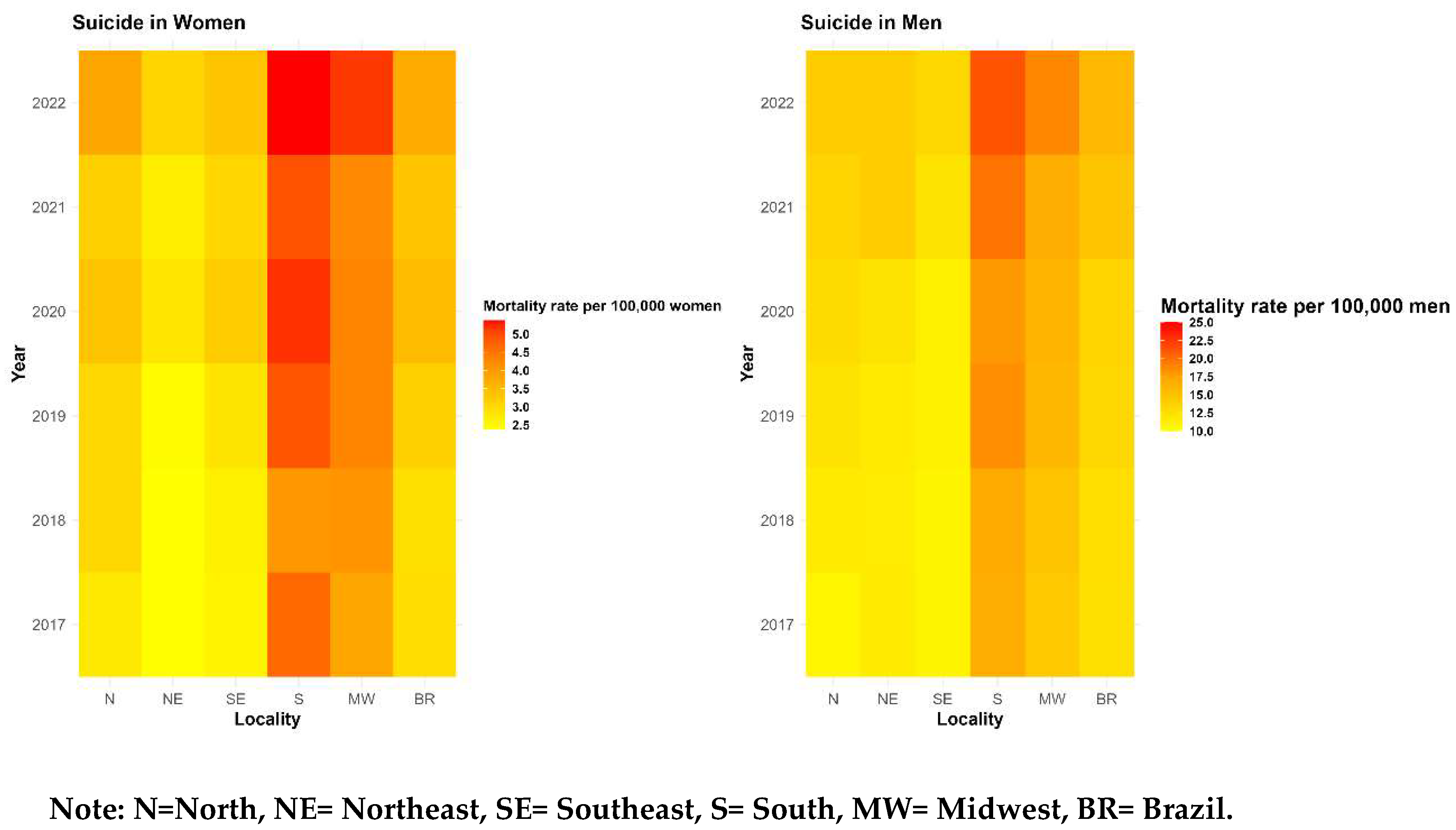

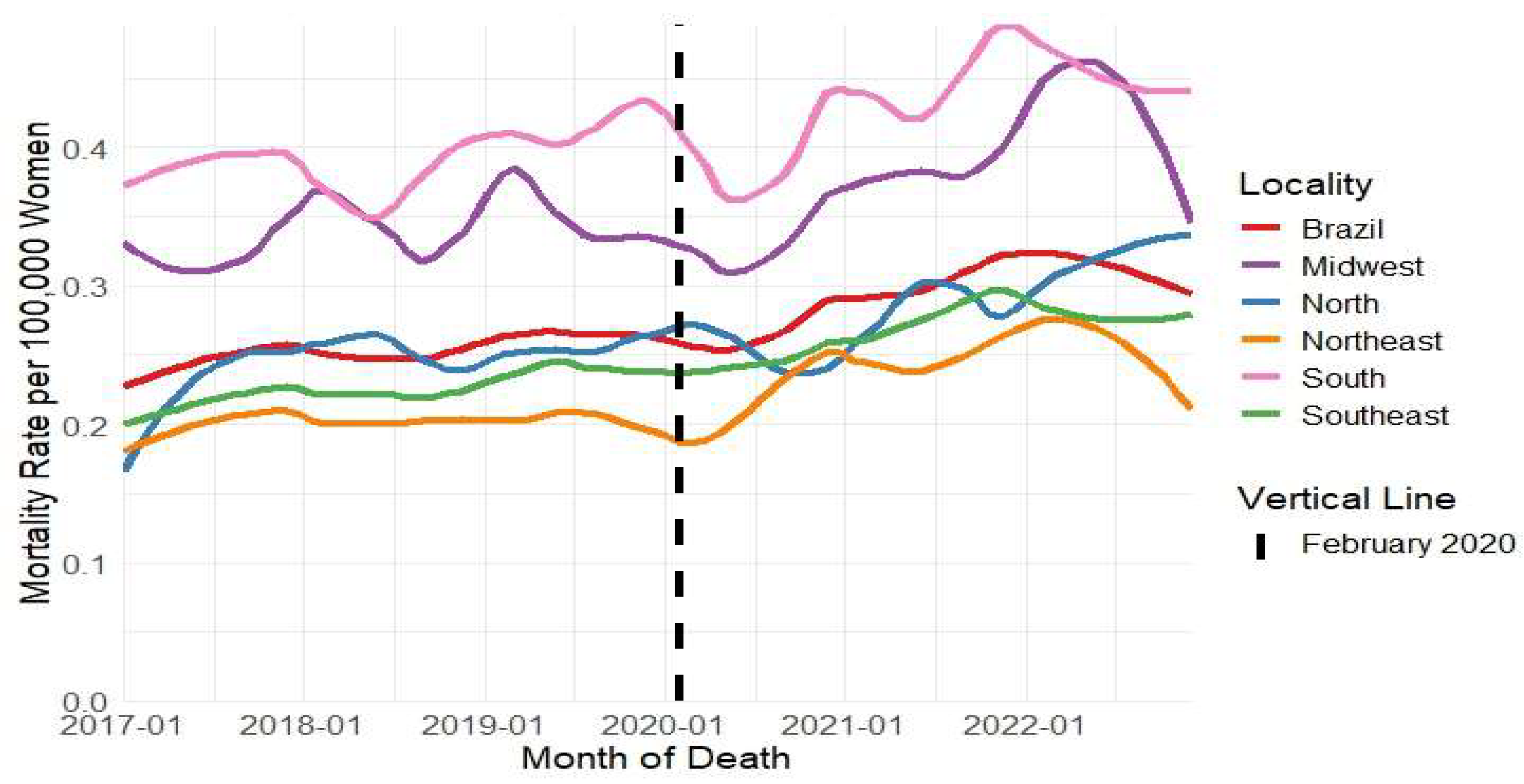

| Locality b | ||||

| North | 1.041 (0.167) | <0.001 | 0.266 (0.06) | <0.001 |

| Northeast | 1.048 (0.125) | 0.220 (0.039) | ||

| Southeast | 0.967 (0.112) | 0.245 (0.037) | ||

| South | 1.811 (0.227) | 0.403 (0.083) | ||

| Midwest | 1.346 (0.194) | 0.360 (0.080) | ||

| Brazil | 1.049 (0.111) | 0.273 (0.034) | ||

| Race/skin colorc | ||||

| Black | 0.795 (0.108) | <0.001 | 0.193 (0.033) | <0.001 |

| White | 1.000 (0.097) | 0.288 ( 0.036) | ||

| Method of perpetration b | ||||

| Firearm | 0.085 (0.011) | <0.001 | 0.008 (0.003) | <0.001 |

| Autointoxication | 0.080 (0.012) | 0.058 (0.011) | ||

| Hanging, strangulation and suffocation | 0.777 (0.092) | 0.1587 (0.022) | ||

| Variable | Before pandemic | After pandemic | Men | Before pandemic | After pandemic | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Men | Women | Women | |||

| Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | p-valuec | Mean (SDa) | Mean (SDa) | p-valuec | |

| Age group (age) | ||||||

| 10 to 14 | 0.092 (0.041) | 0.089 (0.048) | 0.144 | 0.097 ( 0.042) | 0.121(0.038) | 0.016 |

| 15 to 19 | 0.669 (0.138) | 0.658 (0.179) | 0.002 | 0.283 ( 0.066) | 0.345 (0.070) | <0.0001 |

| 20 to 39 | 1.051 (0.094) | 1.207 (0.154) | <0.0001 | 0.253 (0.035) | 0.316 (0.041) | <0.0001 |

| 40 to 59 | 1.148 (0.091) | 1.283 (0.113) | <0.0001 | 0.294 ( 0.030 | 0.324(0.047) | 0.003 |

| 60 or more | 1.255 ( 0.119) | 1.355 (0.124) | 0.001 | 0.242 (0.048) | 0.256 (0.048) | 0.217 |

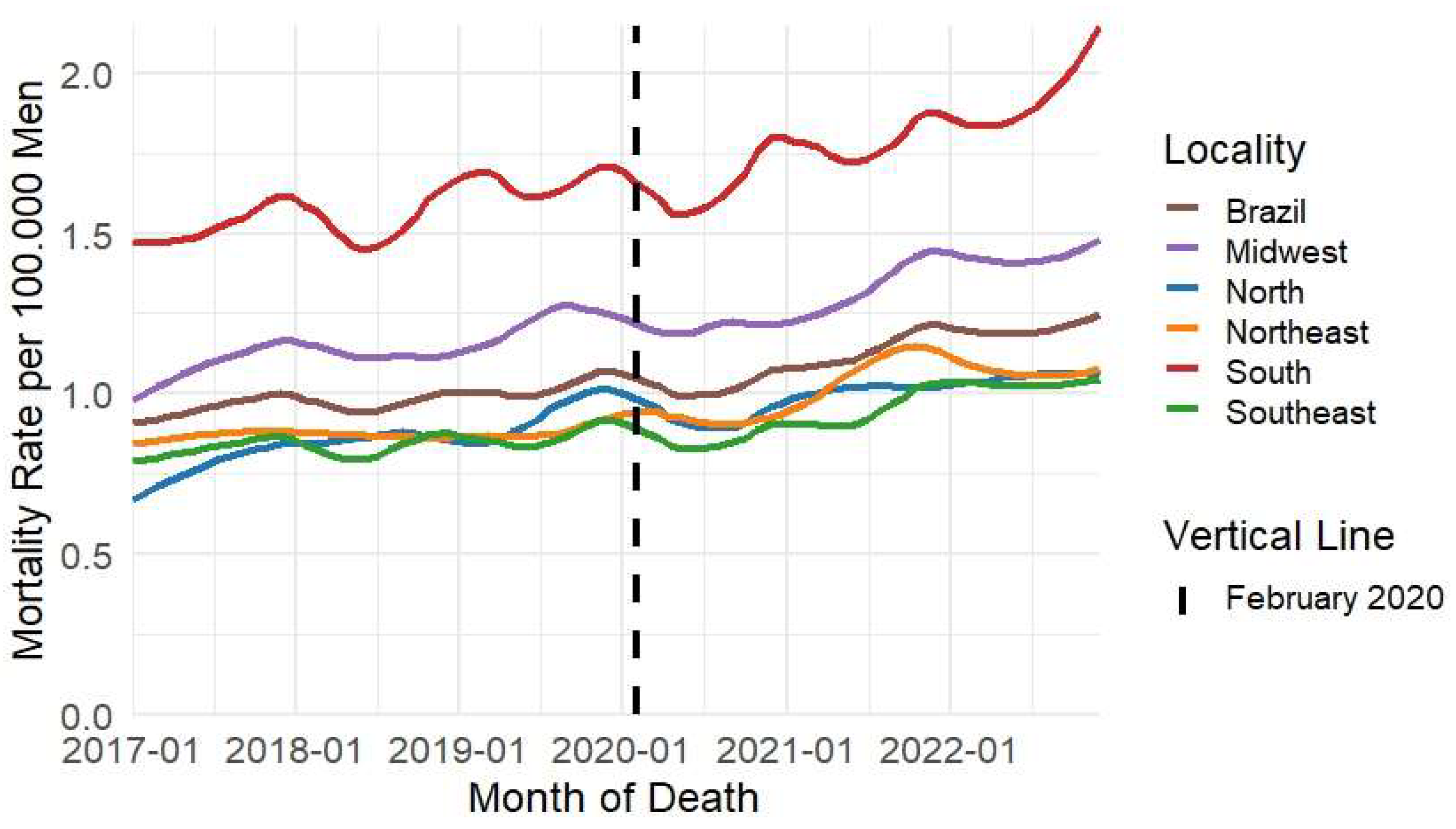

| Locality | ||||||

| North | 0.973 (0.154) | 1.116 (0.149) | <0.0001 | 0.247(0.04) | 0.287 (0.107) | 0.011 |

| Northeast | 0.974 (0.077) | 1.130 (0.118) | <0.0001 | 0.201(0.029) | 0.241(0.039) | <0.0001 |

| Southeast | 0.920 (0.088) | 1.021 (0.113) | <0.0001 | 0.224(0.027) | 0.269 (0.032) | <0.0001 |

| South | 1.716 (0.177) | 1.918 (0.231) | <0.0001 | 0.381 (0.080) | 0.429 (0.080) | 0.014 |

| Midwest | 1.257 ( 0.156) | 1.446 (0.185) | <0.0001 | 0.340(0.066) | 0.382(0.089) | 0.028 |

| Brazil | 0.986(0.074) | 1.121 (0.104) | <0.0001 | 0.253 (0.020) | 0.294 (0.032) | <0.0001 |

| Race/skin colorc | ||||||

| White | 0.968 (0.073) | 1.037 (0.101) | 0.003 | 0.271 (0.029) | 0.310 (0.034) | <0.0001 |

| Black | 0.7215 (0.062) | 0.8763 (0.090) | <0.0001 | 0.174 (0.022) | 0.214(0.029) | <0.0001 |

| Methods | ||||||

| Firearm | 0.0843 (0.011) | 0.086 (0.0116) | 0.338 | 0.009 (0.002) | 0.008 (0.002) | 0.648 |

| Autointoxication | 0.075 (0.009) | 0.085 (0.0118) | <0.0001 | 0.054 (0.007) | 0.064 (0.011) | <0.0001 |

| Hanging, strangulation and suffocation | 0.722 (0.061) | 0.838 (0.083) | <0.0001 | 0.147(0.018) | 0.171 (0.020) | <0.0001 |

| Variables | Categories | Interpretation | RRa | CI95%b | p-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | 10 to 14 | ||||

| Level change | Not detected | 0.939 | 0.982;1.138 | 0.142 | |

| trend change | Progressive increase | 1.002 | 1.001;1.004 | 0.007 | |

| 15 to 19 | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.864 | 0.832;0.899 | <0.0001 | |

| trend change | Progressive increase | 1.006 | 1.005;1.007 | <0.0001 | |

| 20 to 39 | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.868 | 0.8433;0.894 | <0.0001 | |

| trend change | Progressive increase | 1.008 | 1.007;1.009 | <0.0001 | |

| 40 to 59 | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.987 | 0.976;0.998 | 0.031 | |

| trend change | Progressive increase | 1.006 | 1.005;1.006 | <0.0001 | |

| 60 or more years | |||||

| Level change | Increase abrupta | 1.042 | 1.027;1.057 | <0.0001 | |

| trend change | Progressive increase | 1.004 | 1.003;1.005 | <0.0001 | |

| Locality | North | ||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.891 | 0.865 ;0.917 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.009 | 1.008 ;1.010 | <0.0001 | |

| Northeast | |||||

| Level change | Increase abrupta | 1.036 | 1.012;1.061 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.004 | 1.003;1.005 | <0.0001 | |

| Southeast | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.916 | 0.886;0.947 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.056 | 1.050;1.062 | <0.0001 | |

| South | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.901 | 0.875;0.924 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.007 | 1.006;1.008 | <0.0001 | |

| Midwest | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.936 | 0.926;0.946 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.007 | 1.006;1.008 | <0.0001 | |

| Brazil | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.939 | 0.918;0.960 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.006 | 1.0054;1.007 | <0.0001 | |

| Race/Skin color | Black | ||||

| Level change | Not detected | 0.986 | 0.949; 1.025 | 0.503 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.007 | 1.005.1.009 | <0.0001 | |

| White | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.884 | 0.851; 0.919 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.006 | 1.005;1.007 | <0.0001 | |

| Methods | Firearm | ||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.873 | 0.861;0.885 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.005 | 1.005;1.006 | <0.0001 | |

| Autointoxication | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.982 | 0.972;0.991 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.004 | 1.0044;1005 | <0.0001 | |

| HSSd | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.936 | 0.912;0.960 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.007 | 1.006;1.008 | <0.0001 |

| Variables | Categories | Interpretation | RRa | CI95%b | p-valuec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | 10 to 14 | ||||

| Level change | Not detected | 0.917 | 0.648 ;1.296 | 0.624 | |

| trend change | Not detected | 1.008 | 1.000;1.017 | 0.053 | |

| 15 to 19 | |||||

| Level change | Not detected | 0.959 | 0.789;1.165 | 0.674 | |

| trend change | Progressive increase | 1.007 | 1.002 ;1.011 | 0.0069 | |

| 20 to 39 | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.945 | 0.932 ;0.958 | <0.0001 | |

| trend change | Progressive increase | 1.105 | 1.101 ;1.108 | <0.0001 | |

| 40 to 59 | |||||

| Level change | Not detected | 1.004 | 0.895 ;1.127 | 0.9414 | |

| trend change | Not detected | 1.003 | 1.000 ;1.005 | 0.0689 | |

| 60 or more years | |||||

| Level change | Not detected | 1.087 | 0.913;1.295 | 0.352 | |

| trend change | Not detected | 0.996 | 0.989;1.003 | 0.732 | |

| Locality | North | ||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.920 | 0.865 ;0.937 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.008 | 1.007 ;1.009 | <0.0001 | |

| Northeast | |||||

| Level change | Not detected | 1.047 | 0.909 ;1.205 | 0.5262 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.004 | 1.000 1.007 | 0.0312 | |

| Southeast | |||||

| Level change | Not detected | 1.046 | 0.940;1.164 | 0.4127 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.004 | 1.001;1.006 | 0.0048 | |

| South | |||||

| Level change | Not detected | 0.957 | 0.904 ;1.014 | 0.139 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.005 | 1.004;1.006 | <0.0001 | |

| Midwest | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.889 | 0.869 ;0.909 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.007 | 1.007;1.008 | <0.0001 | |

| Brazil | |||||

| Level change | Not detected | 0.985 | 0.969;1.000 | 0.055 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.005 | 1.001;1.006 | <0.0001 | |

| Race/Skin color | Black | ||||

| Level change | Not detected | 0.950 | 0.857 ;1.053 | 0.334 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.007 | 1.005;1.010 | <0.0001 | |

| White | |||||

| Level change | Not detected | 0.995 | 0.908 ;1.090 | 0.914 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.004 | 1.001 1.006 | 0.002 | |

| Methods | Firearm | ||||

| Level change | Not detected | 1.12 | 0.848;1.479 | 0.427 | |

| Trend change | Not detected | 0.996 | 0.989;1.003 | 0.24 | |

| Autointoxication | |||||

| Level change | Not detected | 1.04 | 0.897;1.206 | 0.607 | |

| Trend change | Not detected | 1.004 | 1.000;1.007 | 0.05 | |

| HSSd | |||||

| Level change | Abrupt reduction | 0.947 | 0.926;0.968 | <0.0001 | |

| Trend change | Progressive increase | 1.006 | 1.005;1.007 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).