1. Introduction

Contemporary software, whether it involves computing algorithms executing process workflows or mimicking the brain using neural network algorithms, has its roots in Alan Turing’s profound observation [

1] p. 231: “We may compare a man in the process of computing a real number to a machine which is only capable of a finite number of conditions.” Today, software is ubiquitous, permeating every aspect of our lives by facilitating communication, collaboration, and commerce on a global scale. It powers everything from social media platforms and online marketplaces to advanced scientific research and artificial intelligence.

However, this pervasive presence comes with significant challenges. The very connectivity that enables global interaction also exposes us to risks related to privacy and data security. Despite the implementation of multiple layers of complex systems and processes designed to safeguard our software infrastructure, vulnerabilities persist. Hackers and fraudsters continually exploit these weaknesses, leveraging the global reach of the Internet to launch sophisticated attacks.

Moreover, the rapid evolution of software technologies brings both opportunities and ethical dilemmas. As we integrate software into critical areas such as healthcare, finance, and autonomous systems, the stakes become higher. Ensuring the ethical use of software, maintaining transparency in algorithmic decision-making, and protecting user data are paramount concerns that require ongoing attention and innovation.

In essence, while contemporary software drives unprecedented advancements and connectivity, it also necessitates vigilant efforts to address the accompanying risks and ethical considerations.

In this paper, we argue that the current problems associated with the complexity and vulnerability to hacking and fraud in information systems using general-purpose computers are not merely operational issues but stem from the foundational shortcomings of the stored program implementation of the Turing machine computing model. As Cockshott et al., point out in their book Computation and its Limits, the concept of the universal Turing machine has allowed engineers and mathematicians to create general-purpose computers and use them to “deterministically model any physical system, of which they are not themselves a part, to an arbitrary degree of accuracy. Their logical limits arise when we try to get them to model a part of the world that includes themselves” [

2] p. 215).

In addition, digital computing processes, especially when distributed, are executed by several software components using computing resources often owned and managed by different providers. Ensuring end-to-end process sustenance, stability, safety, security, and compliance with global requirements necessitates a complex layer of additional processes. This complexity leads to the “who manages the manager” conundrum. Any failure in the system requires information access and analysis from multiple sources, resulting in a reactive approach to fixing problems.

As von Neumann said in his Hixon lectures in 1948 [

3] p. 409 “The basic principle of dealing with malfunctions in nature is to make their effect as unimportant as possible and to apply correctives, if they are necessary at all, at leisure. In our dealings with artificial automata, on the other hand, we require an immediate diagnosis. Therefore, we are trying to arrange the automata in such a manner that errors will become as conspicuous as possible, and intervention and correction follow immediately." Comparing the computing machines and living organisms, he points out that the computing machines are not as fault tolerant as the living organisms. He goes on to say [

3] p. 474 "It's very likely that on the basis of philosophy that every error has to be caught, explained, and corrected, a system of the complexity of the living organism would not run for a millisecond.”

There are several discussions of computing models pointing to the foundational shortcomings and suggesting new computing models [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. However, recent application of the General Theory of Information (GTI) [

13,

14] and the theory of structural reality [

15] offer a new insight into how biological systems use information and knowledge to observe, model, and make sense of what they are observing fast enough to do something about it while they are still observing it. According to GTI, knowledge belongs to the realm of biological systems and Knowledge processing is an important feature of intelligence. GTI provides a bridge between our understanding of the material world consisting of matter and energy and the mental worlds of biological systems which utilize information and knowledge to interact with the material world. Biological systems, while made up of material structures, are unique in their ability to maintain the identity of their structures, observe themselves and their interactions with the external world using information processing structures, and make sense of what they are observing fast enough to do something about it while they are still observing it. The biological structures are self-regulating and use autopoietic and cognitive processes, which assure their stability, sustenance, safety, and survival through homeostasis. The genome provides the operational knowledge to execute life processes used to build, self-organize, operate, and maintain the system using both inherited and learned knowledge and assure stability, sustenance, safety, security, and survival in the face of fluctuations in the interactions within the system and with its environment. GTI allows us to derive a schema that represents the knowledge consisting of fundamental triads/named sets [

13,

14,

16,

17] dealing with various entities, relationships, and event driven interactions. It helps explain how knowledge is represented in the form of associative memory and the event driven interaction history and used in making intelligent decisions. In addition, GTI provides a schema-based knowledge representation in digital automata allowing us to infuse autopoietic and enhanced cognitive behaviors using associative memory and event-driven interaction history of the entities, their relationships and behaviors constituting the system being represented [

18]. The objectives of this paper are:

Explore the nature of natural and machine intelligence.

Explain the new GTI-based approach to design, build, deploy and operate distributed software systems with enhanced cognition and are autopoietic. Autopoietic behavior refers to the self-producing and self-maintaining nature of both living and digital computing systems. Cognitive behavior refers to obtaining and using knowledge to act based on associative memory and event-driven interaction history.

Explain the relationship between AI, Gen-AI, AGI, which are based on symbolic and sub-symbolic computing structures and GTI-derived super-symbolic computing structures.

Give some examples of implantation of autopoietic and cognitive software systems.

Section 2 explores the nature of natural and machine intelligence.

Section 3 discusses the evolution of AI and Gen-AI from symbolic computing and the aspirations of AGI.

Section 4 discusses GTI and the schema-based computing structures.

Section 5 discusses the nature of autopoietic and cognitive behaviors in digital automata.

Section 6 describes the methodology and a couple of prototypes using the new approach.

Section 7 discusses the comparison with current approaches and the new approach.

Section 7 concludes with some observations on the future direction.

2. Machine and Natural Intelligence

Biological systems, while made up of material structures, are unique in their ability to keep the identity of their structures, observe themselves and their interactions with the external world using information processing structures, and make sense of what they are observing fast enough to do something about it while they are still observing it. They inherit the knowledge to build, run, manage their structures, and interact with their environment using neural cognitive capabilities acquired from their genome transmitted by the survivor to the successor. A genome is an organism’s complete set of genetic instructions. Each genome contains all of the information needed in the form of life processes to build the organism and allow it to grow and operate a society of genes. As described by Itai and Lercher in their book [

19] p. 11 “The Society of Genes”, the single fertilized egg cell develops into a full human being without a construction manager or architect. The responsibility for the necessary close coordination is shared among the cells as they come into being. It is as though each brick, wire, and pipe in a building knows the entire structure and consults with the neighboring bricks to decide where to place itself”.

The knowledge is passed on from the successors to the survivors as chromosomes which contain knowledge to create a society of cells that behave like a community, where individual cell roles are well-defined, and their relationships with other cells are defined through shared knowledge and they collaborate by exchanging messages with each other defined by specific relationships and behaviors. DNA provides a symbolic computing structure with the knowledge to use matter and energy to create and maintain stable structures with specific tasks. In addition, the neurons, also known as nerve cells, form the fundamental units of brain and the nervous system which carry information. The brain contains billions of neurons and form complex networks that process information, and update knowledge which is stored in form of associative memory and event-driven interaction history. Both associative memory and event-driven interaction history strengthen connections based on experiences and events. This allows the brain to learn, adapt, and recall information efficiently.

Alan Turing, in addition to giving us the Turing Machine from his observation of how humans used numbers and operations on them, also discussed unorganized A-type machines. His 1948 paper “Intelligent Machinery” gives an early description of the artificial neural networks used to simulate neurons today. His paper was not published until 1968 – years after his death – in part because his supervisor at the National Physical Laboratory, Charles Galton Darwin, described it as a “schoolboy essay.”

While in 1943 McCulloch and Pitts [

20], proposed mimicking the functionality of a biological neuron, Turing’s 1948 paper [

21] discusses the teaching of machines as this summary says from his 1948 paper. “The possible ways in which machinery might be made to show intelligent behavior are discussed. The analogy with human brain is used as a guiding principle. It is pointed out that the potentialities of the human intelligence can only be realized if suitable education is provided. The investigation mainly centres round an analogous technique teaching process applied to machines. The idea of an unorganized machine is defined, and it is suggested that the infant human cortex is of this nature. Simple examples of such machines are given, and their education by means of rewards and punishment is discussed. In one case, the education process is carried through until the organization is similar to that of an ACE”

Here ACE refers to the Automatic Computing Machine which was a British early electronic serial stored program computer designed by him. Current-generation digital computers are stored program computers that use sequences of symbols to represent data containing information about a system and programs that operate on the information to create knowledge of how the state of the system changes when certain events represented in the program change the behavior of various components or entities that are interacting with each other in the system. The machines thus are taught about human knowledge of how various systems they observe behave in the digital notation using sequences of symbols.

It is remarkable that Turing predicted what areas are suitable and had an opinion about what would be most impressive. “What can be done with a ‘brain’ which is more or less without a body providing, at most, organs of sight, speech, and hearing. We are then faced with the problem of finding suitable branches of thought for the machine to exercise its powers its powers in. …. Of the above possible fields, the learning of languages would be the most impressive, since it is the most human of these activities.”. In addition, he went on to predict machines where mere communication to the machine, which alters its behavior. “The types of machines that we have considered so far are mainly ones that are allowed to continue in their own way for indefinite periods without interference from outside. The universal machines were an exception to this, in that from time to time one might change the description of the machine which is being imitated. We shall now consider machines in which such interference is the rule rather than the exception. We may distinguish two kinds of interference. There is the extreme form in which parts of the machine are removed and replaced by others. This may be described as ‘screwdriver interference’. At the other end of the scale is ‘paper interference’, which consists in the mere communication of information to the machine, which alters its behavior. In view of the properties of the universal machine we do not need to consider the difference between these two kinds of machine as being so very radical after all. Paper interference when applied to the universal machine can be as useful as screwdriver interference. We shall mainly be interested in paper interference. Since screwdriver interference can produce a completely new machine without difficulty there is rather little to be said about it. In future ‘interference’ will normally mean ‘paper interference’.”

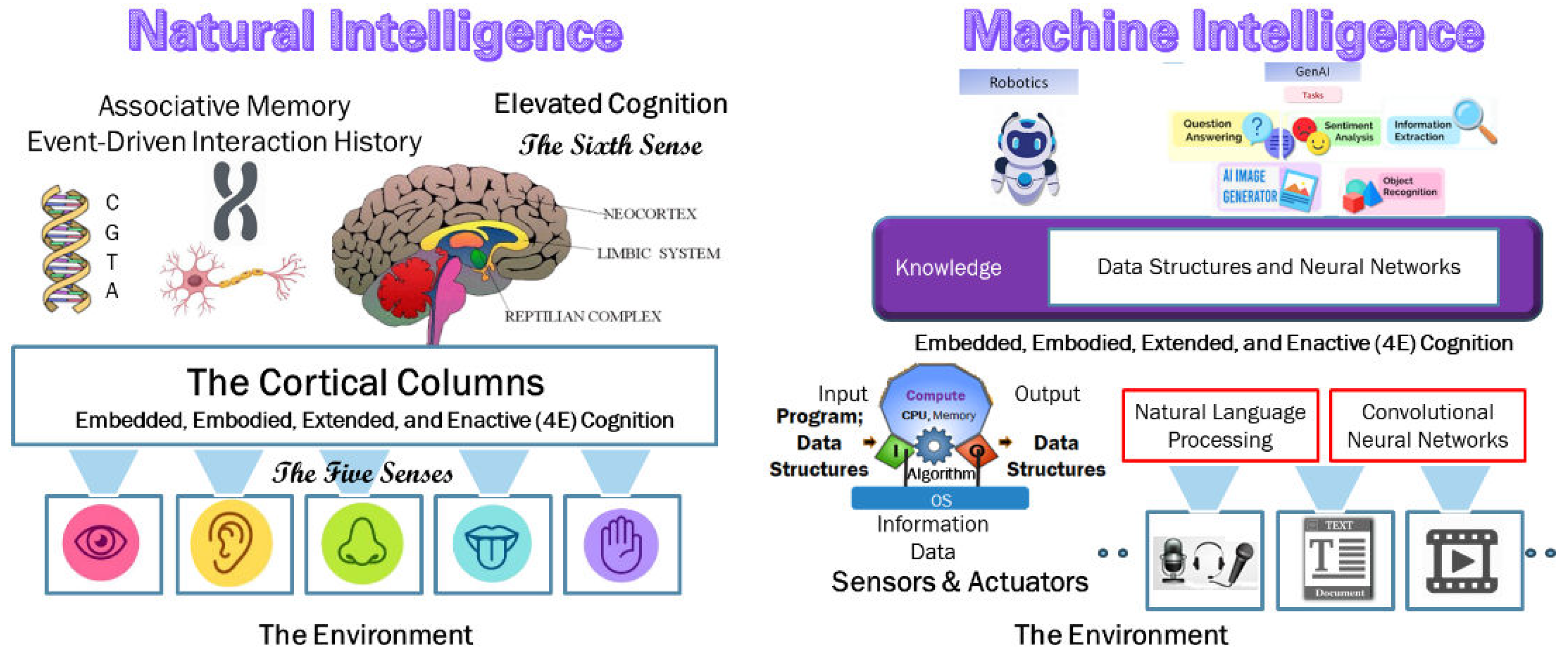

Figure 1 depicts the nature of natural and machine intelligence.

Natural intelligence is derived from the knowledge inherited from the genome. The picture shows the information received through the five senses processed by the cortical columns and the knowledge stored in the associative memory and event-driven transaction history as neural networks. The neocortex provides a higher-level elevated cognition that has the model of the “self” and the knowledge to model and use the interactions with the external world also stored in the associative memory and the interaction history.

Machine intelligence stems from the execution of algorithms represented as a sequence of symbols (0 and 1) operating on data also represented as a sequence of symbols (0 and 1). Symbolic computing executing algorithms designed to implement well-defined tasks and processes and sub-symbolic processing algorithms mimicking the neural networks are used to convert information from different sources into knowledge stored as neural networks.

In the next section, we will examine the evolution of symbolic, sub-symbolic computing structures through language processing to AI and Gen-AI.

3. Evolution of AI, Generative AI, and AGI

The term “Artificial Intelligence” was coined by John McCarthy in 1955 [

22]. McCarthy, along with other pioneers like Marvin Minsky, Allen Newell, and Herbert A. Simon, played a crucial role in shaping the field of AI. Today, there are two different types of algorithms under the umbrella of AI. Machine learning is a subset of AI that enables systems to learn and improve from experience without being explicitly programmed. Deep learning is a subset of machine learning that uses artificial neural networks with many layers (hence “deep”) to model complex patterns in data.

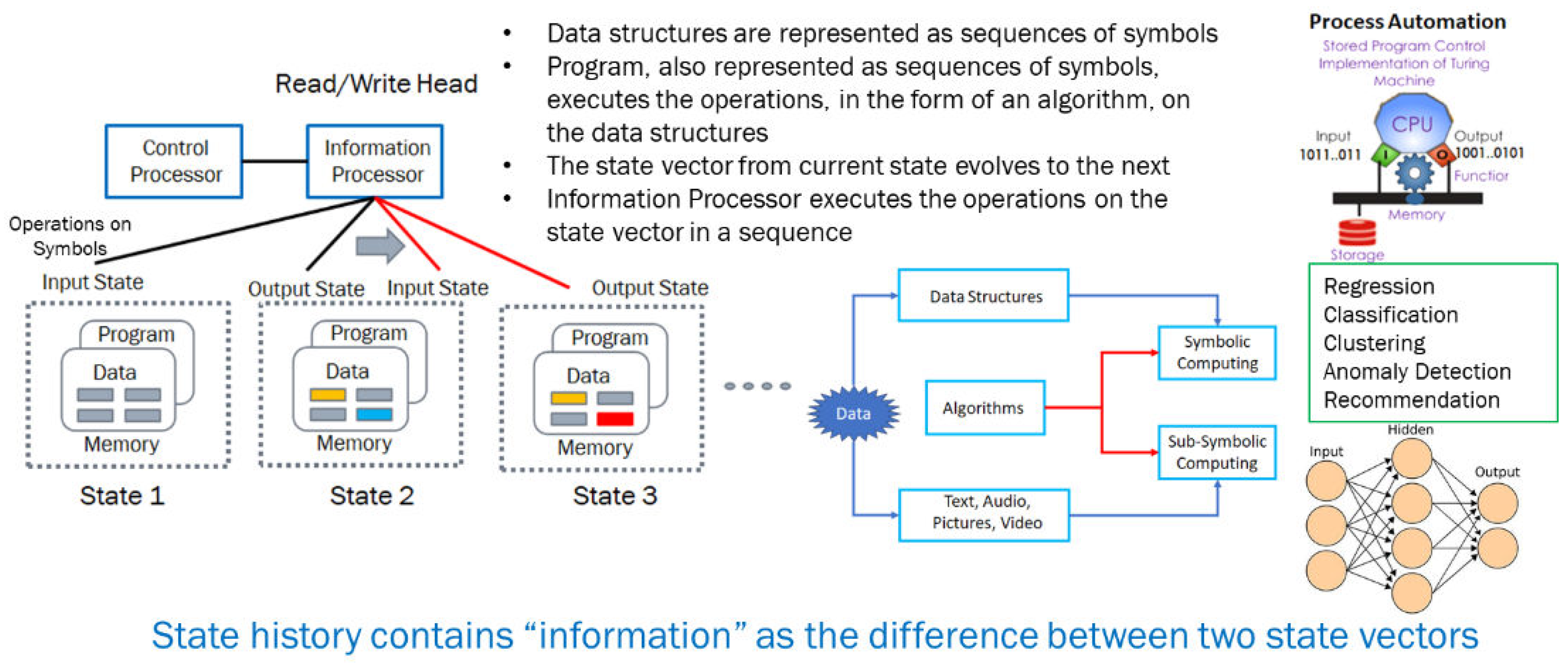

Figure 2 shows the schema that implements the stored program control architecture and the relationship between symbolic and symbolic computing. The differences between process automation, machine learning, and deep learning stem from the algorithm used. The program contains an algorithm which changes the state of the data structures and a sequence of steps execute a workflow defining a process with a purpose defined by functional requirements. Machine learning models involve state evolution, where the model’s parameters are updated iteratively to improve performance using large sets of data and identify patterns. These include regression, classification, clustering, anomaly detection and recommendations. Deep learning involves optimizing the parameters of a neural network through various training and error correction algorithms.

Generative AI (Gen-AI) is a subset of deep learning. While deep learning focuses on analyzing large datasets to make predictions and recognize patterns, Gen-AI is designed to create new content from existing data. uses models like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) to generate new, original content [

23,

24,

25]. For example, GANs consist of two neural networks (a generator and a discriminator) that work together to create realistic images, text, or other data types. While deep learning is about understanding and interpreting data, Gen-AI takes it a step further by using that understanding to create new content. Examples are GPT-4 for text generation and DALL·E for image creation.

It is important to note that all these approaches are based on defining specific algorithms and executing them using the computing structures that provide the required CPU, memory and the energy required. As such, they are still subject to the constraints discussed in the introduction about the foundational shortcomings. While symbolic or sub-symbolic computing algorithms model any physical system with functional requirements which are well defined, they do not include the computing structures that execute them. The computer and the computed are decoupled and third-party management infrastructure is required to manage the non-functional requirements which define the sustenance, safety, survival and the management of deviation that may occur in fulfilling the functional requirements. Self-regulation which is the hallmark of biological system is a requirement if machine intelligence to reach the level of natural intelligence. In addition, the computing structures must develop a sense of “self” and the ability to model the world with which it interacts to be able to make sense of its interactions while the observation is still in progress and decide on possible courses of action. This requires overcoming the foundational shortcomings of digital machines mentioned earlier.

In essence, while symbolic computing extends our modeling, sensing, and controlling the environment, and sub-symbolic computing extends some of the brain functions converting of information into knowledge, what are lacking in digital machines are the functions of the mind provided by the neocortex which has the model of the “self” and its interaction history that natural intelligence possesses.

Currently there are two approaches to fill this gap. First one is AGI [

26,

27,

28] and the other which infuses autopoietic and enhanced cognitive behaviors into digital automata derived from the GTI.

AGI aims to replicate human-like intelligence, capable of performing any intellectual task that a human can do. AGI would possess the ability to learn, reason, and solve problems across a wide range of domains, not limited to specific tasks. According to Ben Goertzel [

26], “At the moment, AGI system design is as much artistic as scientific, relying heavily on the designer’s scientific intuition. AGI implementation and testing are interwoven with (more or less) inspired tinkering, according to which systems are progressively improved internally as their behaviors are observed in various situations. This sort of approach is not unworkable, and many great inventions have been created via similar processes. It’s unclear how necessary or useful a more advanced AGI theory will be for the creation of practical AGI systems. But it seems likely that, the further we can get toward a theory providing tools to address questions like those listed above, the more systematic and scientific the AGI design process will become, and the more capable the resulting systems”. I refer the readers to the papers by Ben for an excellent review of the state of the art of AGI and its future. We devote the rest of the paper to the application of GTI infusing autopoietic and cognitive behaviors using a knowledge representation in the form of associative memory and event-driven interaction history.

4. General Theory of Information, Matter, Energy, Information, and Knowledge

The GTI, developed by Mark Burgin, offers a comprehensive framework for understanding information across various domains. It bridges the gap between the material world (dealing with matter and energy) and the mental worlds of biological systems, which utilize information and knowledge [

29]. GTI emphasizes the role of information in maintaining the identity and stability of biological systems through processes like replication and metabolism. This theory is crucial for modeling digital systems that exhibit autopoietic (self-organizing and self-maintaining) and cognitive behaviors. Theory of structural reality [

30] helps us understand the structural aspects of cognitive systems, both natural and artificial, by emphasizing the relationships and interactions between different components of a system. By integrating the principles of GTI and structural reality, we can better understand and model the complex behaviors of both natural and artificial cognitive systems. This integration allows for the development of digital machines that mimic the self-regulation and self-determination seen in living organisms [

31].

While GTI has been discussed widely in several books and peer reviewed journals, its impact on the future of AI is not widely recognized [

32,

33]. None of the papers refer to GTI. In this paper, we will discuss the application of GTI to infusing autopoietic and enhanced cognitive behaviors into digital machines using the associative memory and event driven interaction history with well-defined functional requirements, non-functional requirements and best-practices gleaned from experience.

According to the GTI, material structures are the physical entities that exist in the material world. The state and evolution of these structures over time, represented as phase space, are governed by the laws of transformation of energy and matter. Depending on the nature of the structures, their phase space evolution can be modeled using either the Schrödinger equation or Hamilton’s equations. While material structures carry and represent information, the information itself is not physical.

Knowledge belongs to the realm of biological systems, which have evolved through natural selection to inherit through their genomes, the ability to receive information and convert it into knowledge in the form of mental structures. These mental structures are the cognitive and perceptual constructs within biological systems. They process and utilize information to interact with the material world.

GTI defines information as a bridge between the material and mental worlds. Information can have both physical and mental representations, but it is not inherently physical. It is the content that can be encoded, transmitted, and decoded by both material and mental structures. In the context of GTI, knowledge is the processed and structured form of information that mental structures use to understand and interact with the world. It involves the interpretation and application of information. GTI provides a schema to represent knowledge in the form of composable fundamental triads/named sets which capture the entities, relationships and their behaviors when interactions between the entities change their structures or their attributes.

In the next section, we will discuss how the same schema is used to create a new class of digital automata with autopoietic and enhanced cognitive behaviors.

5. Autopoietic and Enhanced Cognitive Behaviors in Digital Automata

The General Theory of Information (GTI) provides a comprehensive framework for modeling entities, relationships, and their behaviors. This allows us to model a system whose functional and non-functional requirements are defined along with best practice policies and constraints specified to deal with deviations from expected behaviors. Genome is an example where the various life processes to build, operate, and manage the system with a knowledge of the “self” and its interactions. Same schema and operations are used to model a digital genome based on the functional and non-functional requirements along with best practice policies and constraints specified to deal with deviations from expected behaviors of an algorithm-based workflow defining a software system [

18,

29,

31]. Functional requirements define the software workflow defining the goals, entities with various attributes participating in the workflow executing the goals, their relationships, and the behaviors when any of the attribute’s ore entities undergo a change in their state. The workflow consists of a hierarchical network of processes executing various functions fulfilling the functional requirements. The process may be executing symbolic or sub-symbolic computing algorithms.

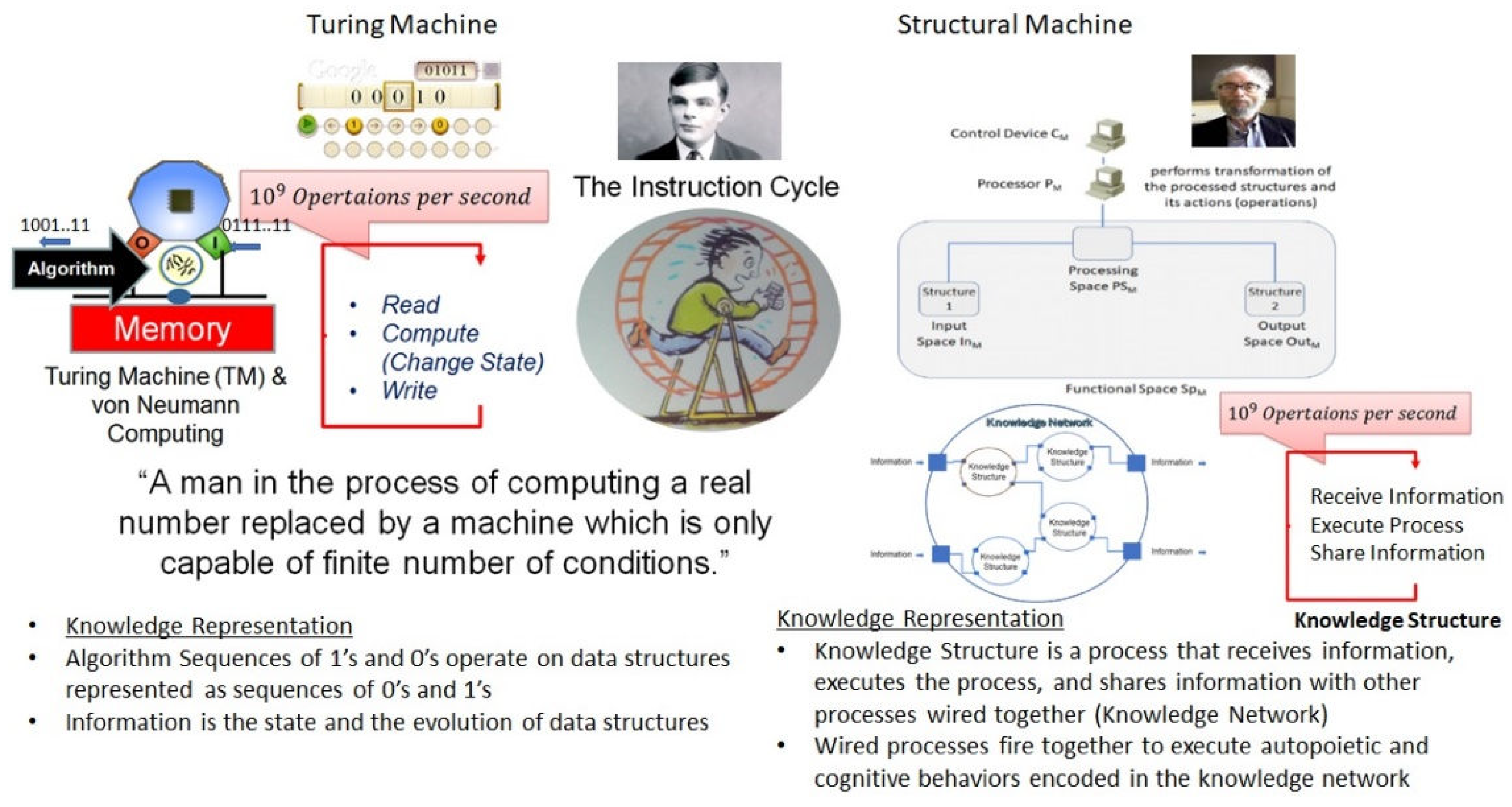

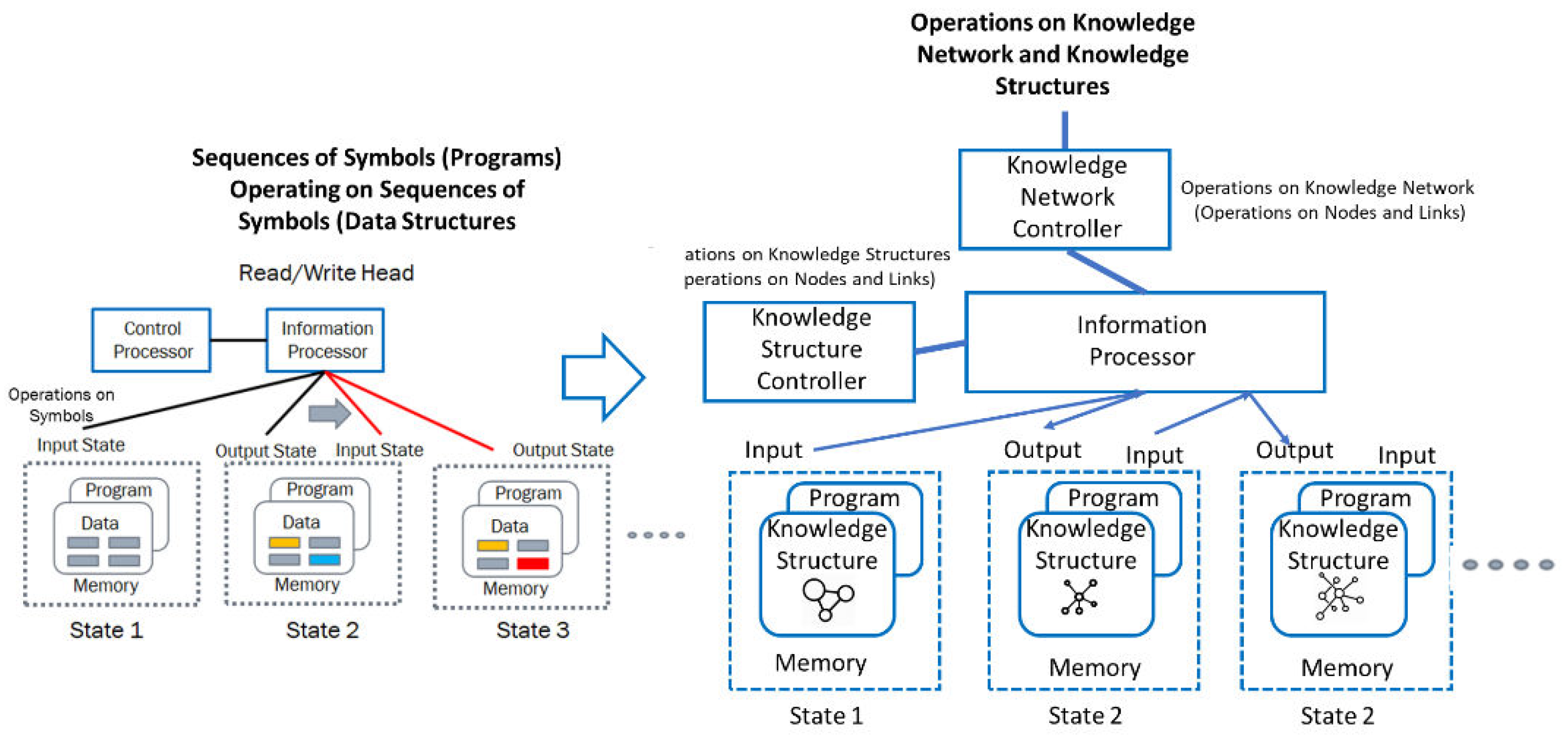

Figure 3 shows the new computing model derived from GTI and compares it with the Turing machine-based computing model.

The global workflow is represented as a knowledge network where sub workflows are represented as knowledge structures. While the information processor executes the functional workflow, the control processor executes the non-functional requirements and implements the policies and constraints defined in the digital genome.

Figure 4 shows the Turing Machine and Structural Machine comparison. In the Turing Computing model, operations are on strings of symbols (data structures). In the Structural machines, the operations are at two levels – one at the node level in the work and another on the network structure consisting of nodes and links.

In the next section, we describe the implementation of the knowledge network defined by a digital genome and provide references to a couple of implementations solving business problems.

6. The Digital Genome, Associative memory, and Event-Driven Interaction History

The methodology of implementing the structural machine using a digital genome specifying a workflow solving a business problem is as follows:

Planning and defining a problem statement: Using business knowledge from multiple sources, develop an understanding of the problem and solution. Identify various entities, relationships, and behaviors in various tasks involved. Behavior relates to changes in the state of the system.

Define Functional and non-functional requirements along with policies and constraints that manage deviations from expected behavior when they occur: Functional requirements define various entities, their relationships, and behaviors involved in executing the functional workflow. Non-functional requirements describe the structure of a computer network that provides the resources and the workflows to monitor and manage structure when deviations occur from the expected functional or structural behavior.

Model the schema: Using a graph database, define the nodes representing various entities with the necessary attributes and the algorithms that change the state when events occur. In essence, each attribute contains a name with value or a link to a process that provides the value using an algorithm. Each node, called a knowledge structure, is translated into its own containerized software service. Functional requirement processes are defined and executed by the algorithms. Non-functional requirements are implemented to manage the resources in the cloud environment and ensure a stable state of expected behavior. All connected nodes share knowledge through API to create a network of communication that reflects the vertex and edge relationship in our schema.

Each node is deployed as a service with inputs, a process execution engine executing the workflow defined in the knowledge structure node, and outputs that communicate with other knowledge structures using shared knowledge between the knowledge structures. A knowledge network, thus, comprises a hierarchical set of knowledge structures (nodes) executing various processes that are activated by inputs and communicating with other knowledge structures using their shared knowledge. Wired nodes fire together to perform the functional and non-functional requirements and policy constraints that keep the system steady, safe, and secure while fulfilling the mission without disruption.

The policies are implemented using agents called “Cognizing Oracles” that monitor the system's structure and function as it evolves, detect deviations from the expected behavior, and take corrective actions.

As the system evolves, the phase space (the system state and history) is captured in the graph database as associative memory and interaction history. These provide a single point of truth for the system to reason and act using the cognizing oracles. Knowledge about the phase space is captured and represented in the associative memory and interaction history.

We refer the reader for detailed implementations using two examples. First [

18] one provides a detailed implementation with a video presentation. The authors “demonstrate a structural machine, cognizing oracles, and knowledge structures derived from GTI used for designing, deploying, operating, and managing a distributed video streaming application with autopoietic self-regulation that maintains structural stability and communication among distributed components with shared knowledge while maintaining expected behaviors dictated by functional requirements.”

The second [

34] one is an application of the structural machine to reduce the knowledge gap between a patient and doctor using a digital genome-based digital assistant. Here is the abstract. “Recent advances in large language models, our understanding of the general theory of information, and the availability of new approaches to building self-regulating domain-specific software are driving the creation of next-generation knowledge-driven digital assistants to improve the efficiency, resiliency, and scalability of various business processes while fulfilling the functional requirements addressing a specific business problem. Here, we describe the implementation of a medical-knowledge-based digital assistant that uses medical knowledge derived from various sources including the large language models and assists the early medical diagnosis process by reducing the knowledge gap between the patient and medical professionals involved in the process.”

These applications demonstrate several unique capabilities that are challenging to achieve with traditional AI or AGI approaches:

Resilience and Autonomy: By integrating self-corrective mechanisms, these systems maintain functionality without continuous external management, making them more resilient in dynamic environments.

Enhanced Cognition and Self-Modeling: The GTI framework allows these systems to possess a sense of “self” by storing interaction histories, enabling them to learn from experience and apply this knowledge to new situations, much like biological systems.

Policy-Driven Ethical Compliance: Especially in the medical assistant, policy constraints derived from ethical and procedural guidelines ensure that the system operates within safety and ethical boundaries, addressing key concerns in healthcare AI applications.

In essence, these applications highlight GTI’s potential to enable a new class of digital automata that go beyond executing static algorithms, embodying self-awareness, resilience, and ethical considerations to meet the demands of complex, real-world environments.

7. Discussion

There are two approaches to advancing the current state of machine intelligence to come closer to the natural intelligence of biological systems. As Charles Darwin [

35] p.5 pointed out, “the difference in mind between humans and higher animals, great as it is, certainly is one of degree and not of kind.” AGI uses deep learning algorithms and agent-based architectures to implement reasoning and higher-level cognition. However, there are yet no mechanisms to infuse a sense of “self,” autopoietic behaviors and enhanced cognition that allows the system to make sense of the current state and use the past experience using associative memory and interaction history to predict options to meet the objectives.

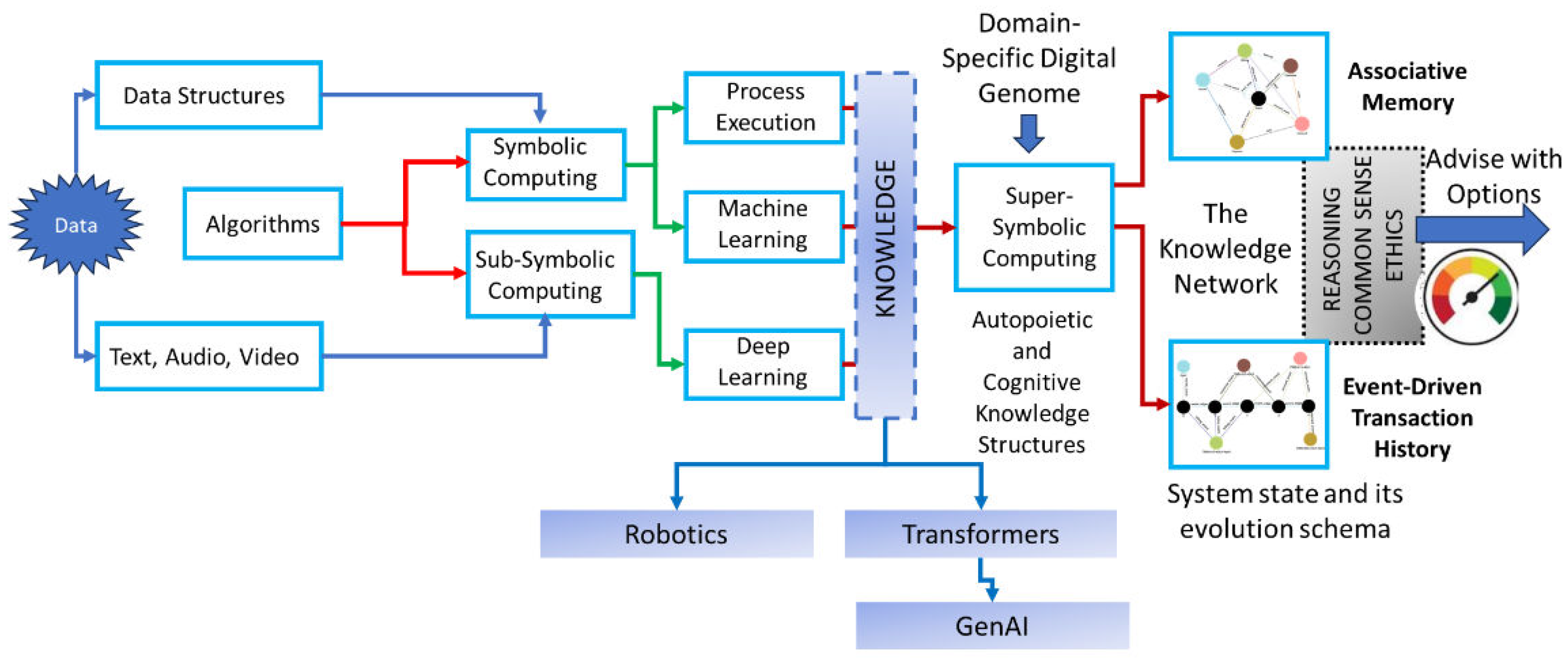

GTI seems to provide an alternative that uses both symbolic and sub-symbolic computing structures as shown in

Figure 5.

Figure 5 depicts the two approaches. In symbolic computing structures, the knowledge is represented as data structures and their state evolution. In sub-symbolic structures, knowledge is represented as optimized parameters in a deep learning neural network. In structural machines, knowledge is represented as a knowledge network composed of knowledge structures. Knowledge structures provide a higher -level abstraction of the systems state and its evolution in terms of workflows. Each knowledge structure executes a process triggered by inputs and communicates the outputs with other knowledge structures using shared knowledge encapsulated. The wired nodes fire together to exhibit collective behavior in fulfilling the functional requirements. Non-functional requirements and policies are fulfilled using cognizing oracles managing the knowledge network. The methodology described allows us to design, deploy, operate and manage the knowledge network where nodes are executed as symbolic or sub-symbolic co9mputing structures.

8. Conclusions

While GTI has been well articulated in many books and peer-reviewed papers, its application to build autopoietic and enhanced cognitive digital automata is new. Hopefully, this paper introduces the novice to the basic concepts and we recommend the original papers and books for a deeper comprehension. Only time will tell the usefulness of this approach. We conclude this paper with the following quote from the Late Prof. Mark Burgin [

36]. “Theory of fundamental triads has three components: mathematical component (theory of named sets), science (including social sciences) component, and philosophical component. In the book some elements of the theory of fundamental triads (named sets) as well as of the theory of chains of named sets are exposed and their applications to the knowsphere - the sphere of knowledge, intellect, and information are considered. The results are applied to various problems of computer science. For example, an exact distinction is obtained between data and knowledge making possible to extract more developed systems of data that are situated between data and knowledge."

GTI provides a schema and operations to deal with knowledge representation that enables both natural and artificial intelligence.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not Applicable

Acknowledgments

The author expresses his gratitude to the late Mark Burgin, who spent countless hours explaining the General Theory of Information and helped him understand its applications regarding software development.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Turing, A. (1936) On Computable Numbers with an Application to the Entscheidungs-problem, Proc. Lond. Math. Soc., Ser.2, v. 42, p. 231.

- Cockshott, P.; MacKenzie, L.M.; Michaelson, G. Computation and Its Limits; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012; p. 215.

- Aspray, W., & Burks, A. (1989). Papers of John von Neumann on Computing and Computer Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- van Leeuwen, J., & Wiedermann, J. (2000). The Turing machine paradigm in contemporary computing. In B. Enquist, & W. Schmidt, Mathematics Unlimited—2001 and Beyond. LNCS. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- Eberbach, E., & Wegner, P. (2003). Beyond Turing Machines. The Bulletin of the European Association for Theoretical Computer Science (EATCS Bulletin), 81(10), 279-304.

- Wegner, P., & Goldin, D. (2003). Computation beyond Turing Machines: Seeking appropriate methods to model computing and human thought. Communications of the ACM, 46(4), 100.

- Wegner, P., & Eberbach, E. (2004). New Models of Computation. The Computer Journal, 47(1), 4-9.

- Wegner, P., & Eberbach, E. (2004). New Models of Computation. The Computer Journal, 47(1), 4-9.

- Cockshott, P., & Michaelson, G. (2007). Are There New Models of Computation? Reply to Wegner and Eberbach. Computer Journal, 5(2), 232-247.

- Denning, P. (2011). What Have We Said About Computation? Closing Statement. http://ubiquity.acm.org/symposia.cfm. ACM.

- Dodig Crnkovic, G. Significance of Models of Computation, from Turing Model to Natural Computation. Minds Mach. 2011, 21, 301–322.

- Burgin, M. Super-Recursive Algorithms; Springer: New York, NY, USA; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. Super-Recursive Algorithms | SpringerLink.

- Burgin. M. (2010) Theory of Information, World Scientific Publishing, New York.

- Burgin, M. Theory of Knowledge: Structures and Processes; World Scientific: New York, NY, USA; London, UK; Singapore, 2016.

- Burgin, M. Structural Reality, Nova Science Publishers, New York, 2012.

- Burgin, M. (2011). Theory of named sets. Nova Science Publishers, N.Y.

- Burgin M, Mikkilineni R. From data Processing to Knowledge Processing: Working with Operational Schemas by Autopoietic Machines. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2021; 5(1):13. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilineni R, Kelly WP, Crawley G. Digital Genome and Self-Regulating Distributed Software Applications with Associative Memory and Event-Driven History. Computers. 2024; 13(9):220. [CrossRef]

- Yanai, I.; Martin, L. The Society of Genes; Harvard University Boston, MA, USA, 2016.

- McCulloch, W.S., Pitts, W. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics 5, 115–133 (1943). [CrossRef]

- Turing, Alan, 'Intelligent Machinery (1948)', in B J Copeland (ed.), The Essential Turing (Oxford, 2004; online edn, Oxford Academic, 12 Nov. 2020), accessed 26 Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J., Minsky, M. L., Rochester, N., & Shannon, C. E. (2006). A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, August 31, 1955. AI Magazine, 27(4), 12. [CrossRef]

- Sengar, S.S., Hasan, A.B., Kumar, S. et al. Generative artificial intelligence: a systematic review and applications. Multimed Tools Appl (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bond-Taylor, S., Leach, A., Long, Y., & Willcocks, C. G. (2021). Deep generative modelling: A comparative review of vaes, gans, normalizing flows, energy-based and autoregressive models. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 44(11), 7327-7347.

- S. Bengesi, H. El-Sayed, M. K. Sarker, Y. Houkpati, J. Irungu and T. Oladunni, "Advancements in Generative AI: A Comprehensive Review of GANs, GPT, Autoencoders, Diffusion Model, and Transformers," in IEEE Access, vol. 12, pp. 69812-69837, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Goertzel, B. Artificial General Intelligence: Concept, State of the Art, and Future Prospects. J. Artif. Gen. Intell. 2009, 5, 1–46.

- Goertzel, B. (2021). The general theory of general intelligence: a pragmatic patternist perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2103.15100.

- Goertzel, B. (2023). Generative ai vs. agi: The cognitive strengths and weaknesses of modern llms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.10371.

- Mikkilineni R. Mark Burgin’s Legacy: The General Theory of Information, the Digital Genome, and the Future of Machine Intelligence. Philosophies. 2023; 8(6):107. [CrossRef]

- Burgin, M. Structural Reality; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2012.

- Mikkilineni R. Infusing Autopoietic and Cognitive Behaviors into Digital Automata to Improve Their Sentience, Resilience, and Intelligence. Big Data and Cognitive Computing. 2022; 6(1):7. [CrossRef]

- https://michaelsantosauthor.com/bcpjournal/autopoiesis-4e-cognition-future-of-artificial-intelligence/ accessed October 28, 2024.

- Arshi, O., Chaudhary, A. (2025). Overview of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). In: El Hajjami, S., Kaushik, K., Khan, I.U. (eds)Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) Security. Advanced Technologies and Societal Change. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Kelly WP, Coccaro F, Mikkilineni R. General Theory of Information, Digital Genome, Large Language Models, and Medical Knowledge-Driven Digital Assistant. Computer Sciences & Mathematics Forum. 2023; 8(1):70. [CrossRef]

- Darwin, C. On the Origin of Species using Natural Selection, or Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life; John Murray: London, UK, 1859.

- Mark Burgin, FUNDAMENTAL STRUCTURES OF KNOWLEDGE AND INFORMATION: REACHING AN ABSOLUTE, Summary of a book.https://www.math.ucla.edu/~mburgin/papers/FstrSUM4.pdf Accessed October 29, accessed on October, 29, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).