1. Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is the most

common adult motor neuron disease (MND), which is characterized by the

relentless loss in varying proportions of both upper motor neurons (UMNs) in

the brain and lower motor neurons (LMNs) in the brainstem and spinal cord.

Although the crude worldwide incidence and prevalence of ALS is estimated at

1.59 per 100,000 person-years and 4.42 per 100,000 population [1], significant regional variations have been

reported [2–5].

Understanding disease presentation and

characteristics has evolved from purely a clinical diagnosis to one currently

supported by electrodiagnostic criteria, although still heavily reliant on the neurologic

examination. Current ALS diagnostic criteria include the revised El Escorial

Criteria [6,7] supplemented by the Awaji

electrodiagnostic modifications [8] as well as

the Gold Coast Criteria [9]. These criteria

have been well described in the literature and rely upon demonstrating

progressive motor neuron dysfunction with varying degrees of diagnostic

certainty. However, these diagnostic criteria are complex to apply, and

patients often experience significant delays in diagnosis, which may bias MND

clinical trials with patients presenting in later stages of disease.

Paralleling the development of categorical

diagnostic criteria, functional markers of disease progression have been

devised, with attention to patient-reported symptom burden via the revised

ALS-Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS-R) [10],

muscle strength by MRC sum score or hand-held dynamometry, and respiratory

function by vital capacity measures [11].

Developing neurophysiologic biomarkers revealing early disease progression or

engagement of pathophysiologic targets would assist patient stratification in

clinical trials and ultimately generate new trial outcome measures, fulfilling

critical needs in the MND field.

From its conception in the 1970’s, the goal of

employing electrodiagnostic techniques to explore the integrity of functional

motor units has remained an area of focus in the MND field. Because of

degeneration of LMNs and their subsequent incomplete reinnervation, ALS and

LMN-predominant MNDs (e.g. progressive muscular atrophy, Kennedy disease) are

ideal conditions to use motor-unit number estimation (MUNE) and other

electrodiagnostic techniques to describe the complex progressive LMN pathology.

Furthermore, neurophysiologic assessment of UMN dysfunction is important for

objective characterization of ALS and UMN-predominant MNDs (e.g. primary

lateral sclerosis), as current diagnostic paradigms rely almost solely on

bedside examination.

2. Lower Motor Neuron Assessment

2.1. MUNE History

In neuromuscular medicine, the assessment of a

single motor unit and its recruitment pattern requires significant training,

mastery of technique, appropriate participation by the patient, and a sense of

the rater’s own self-reliability. In the 1970’s, electrodiagnostic research

groups sought to achieve more objective assessments of the motor unit. McComas

et al. derived the first motor-unit number estimation (MUNE) technique in which

incremental sub-threshold stimulation of a single nerve-muscle pair was used to

generate a stimulus-response curve, with the graded increase of compound muscle

action potential (CMAP) response averaged to approximate the single-motor unit

action-potential (SMUP) amplitude. That SMUP amplitude was divided into the

supra-threshold generated CMAP of the same nerve-muscle pair, with the

resultant value approximating the number of motor units [12].

The advent of a novel MUNE technique was not

without criticism, and later groups challenged the assumptions of the McComas

method, most critically that the earliest recruited SMUP’s have distinct firing

levels and that they are representative of the population of later recruited

SMUP population in that same muscle [13].

Given the concern that there could be significant alternation of SMUP firing in

the earliest recruited motor units, a multi-point stimulation motor unit

estimation method was devised to better characterize the population of early

motor unit recruitment [13,14]. Multi-point

stimulation remains a tool to which more recently developed MUNE techniques are

compared (MUNIX, MScanFit as described later in the text), and demonstrates

strong reproducibility and ability to differentiate MND patients from health

controls [15].

2.2. Motor Unit Number Index

The motor unit number index (MUNIX) technique

describes an idealized motor unit number estimation from the parameters of the

maximal compound muscle action potential (CMAP) of a given muscle and a

surface-EMG interference pattern (SIP) across multiple levels of isometric

force provided by the patient, yielding an ideal case motor unit count (ICMUC) [16]. The ICMUC is defined by [CMAP Power * SIP

Area]/[CMAP Area * SIP Power] which approximates the number of motor units

for a given muscle. A further term, the motor unit size index (MUSIX) is

derived from the CMAP amplitude divided by the MUNIX. In healthy controls

across multiple assessed muscles, ranges of normative values have been

tabulated and MUNIX has correlated well to CMAP amplitude [17,18]. The clinical application of MUNIX has

proven to be reproducible in test-retest models with strong inter- and

intra-rater reliability [18].

2.3. MUNIX as a Diagnostic/Categorical Biomarker

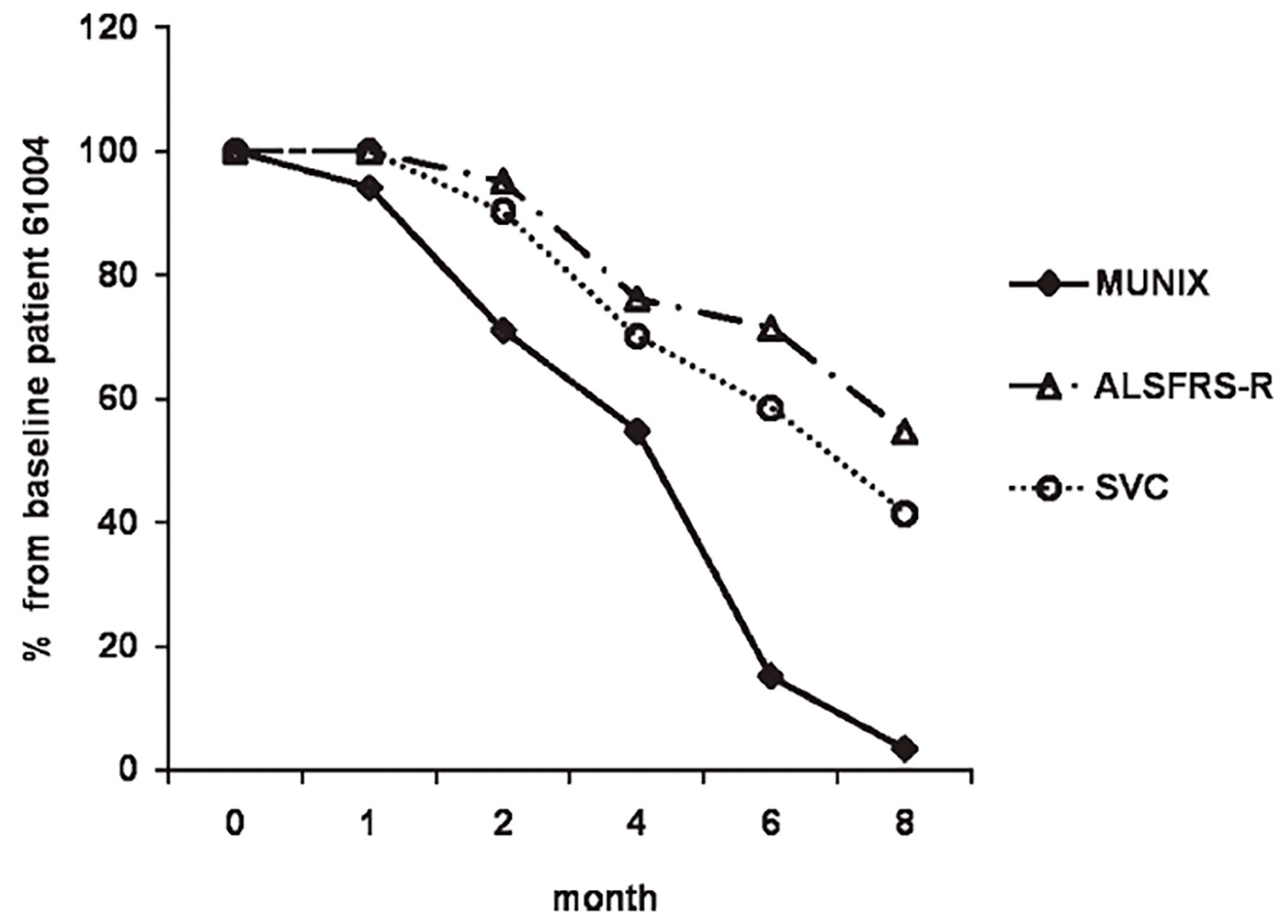

MUNIX values of ALS patients are significantly lower than those of healthy controls with motor unit loss by MUNIX detected in ALS patients well before a decline in CMAP amplitude can be identified by traditional nerve conduction study (NCS)[

19]. MUNIX loss has reliably demonstrated a steeper decline than currently used physiologic markers of MND severity and progression, including the revised ALS-functional rating scale (ALSFRS-R) and slow vital capacity (SVC)[

10,

19]

(Figure 1) prompting investigators to consider whether MUNIX-based motor unit estimation could serve as an electrodiagnostic biomarker in ALS at multiple phases of clinical trial design. More recently, MUNIX mean scores have been shown to significantly predict more rapid rates of ALS disease progression measured by serial ALSFRS-R responses [

20]. Other groups have attempted to enrich the sensitivity and specificity of MUNIX-based testing by incorporating known clinical phenomena seen in ALS, namely the presence of the split-hand pattern, in which CMAP amplitudes are lower in the abductor pollicis brevis (APB) and/or first dorsal interosseous (FDI) muscles than in the relatively spared abductor digiti minimi (ADM) muscle [

21,

22]. The split-hand MUNIX, [(APB MUNIX * FDI MUNIX)/ADM MUNIX], has been shown to better differentiate ALS patients from healthy controls than a previously described CMAP-based split hand index and better correlate with the ALSFRS-R [

23]. MUNIX decline has therefore been considered a potential biomarker of disease severity at inclusion to a clinical trial, an early sign of disease progression once enrolled in a trial, and ultimately a stabilization in the decline of MUNIX as a hopeful sign of pharmacodynamic target engagement as a trial outcome[

24].

2.4. MUNIX as a Marker of Disease Progression/Pharmacodynamic Biomarker

Beyond its use as an adjunct in ALS diagnosis and disease-severity stratification, MUNIX has also been utilized in the assessment of disease progression. Decline in MUNIX of single muscles as well as the sum of multiple MUNIX values has correlated well with previously established markers of ALS disease progression, namely the ALSFRS-R [

25,

26] In some studies, the relative rate of progressive decline in MUNIX values was greater than that of the ALSFRS-R and could even precede the development of clinical objective weakness evaluated by manual muscle testing [

27]. Given the apparent early clinical changes in ALS by MUNIX compared with more traditional assessments of motor function, there has been interest in employing this technique as a pharmacodynamic biomarker in ALS clinical trials. Studies have estimated that employment of MUNIX as a defined clinical outcome in trials could reduce both the time needed to assess therapeutic efficacy and reduce the number of participants required to generate statistical significance. The RESCUE ALS investigators used the mean percent change in summed MUNIX score as the primary outcome in their CNM-Au8 gold nanoparticle antioxidant trial in ALS, which, while not demonstrating significant change in MUNIX values between the trial arms, did show that this technique could prove useful in future clinical studies[

28,

29]. There are many active and recently closed clinical trials employing MUNIX as a secondary outcome with the goal that reduction of MUNIX decline could prove a useful electrodiagnostic biomarker of target engagement [

30,

31,

32].

The use of MUNIX in the clinical assessment of ALS patients has not been without criticism. One of the most common critiques of the MUNIX technique is that it requires the participation of the patient to provide varying levels of force to generate different surface interference patterns on surface EMG, thus making the technique difficult to apply to patients with comorbid cognitive impairment and in non-functional muscle [

33]. There is also some concern from other groups that MUNIX may not obtain a fully representative sample of motor units[

34]. Nonetheless, given the shorter acquisition time and robust data supporting its use, MUNIX remains a widely applied technique in the MND clinical trial landscape.

2.5. MScanFit

Given the questions raised above about MUNIX and its limitations, newer models of motor unit investigation have been designed, with the MScanFit MUNE technique emerging as another prospective electrodiagnostic ALS biomarker. Unlike MUNIX, MScanFit fits a mathematical model to a graded CMAP stimulus-response curve, which presumes to consider the variability of all the motor units recorded over a given muscle and generate a motor unit number estimation [

34]. Jacobsen et al. demonstrated that MScanFit reliably differentiated ALS patients from healthy controls better than MUNIX, at the cost of a longer examination time [

34]. Furthermore, MScanFit demonstrated larger rates of decline per month in ALS patients compared with alternate MUNE techniques, as well as with traditional markers of ALS disease progression including worsening ALSFRS-R scores and CMAP amplitude decline [

35]. Adding the characterization of the split-hand index to MScanFit exhibited greater diagnostic sensitivity and specificity than competing split-hand MUNE techniques [

36]. MScanFit has also been used to shed light on the putative mechanisms of ALS disease pathophysiology, demonstrating that the pattern of neurodegeneration in the distal muscles precedes that of proximal muscles, suggesting a dying-back phenomenon occurring at the level of the lower motor neuron [

33]. The clinical trial landscape has begun to employ MScanFit into trial design, with the recently closed trial RESCUE ALS trial and the active trial RANTAL (NCT06219759) trial using the technique.

2.6. The Neurophysiologic Index and F-Wave Investigations

In parallel to the development of motor unit number estimation techniques, other groups have investigated more traditional electrodiagnostic parameters, with efforts focused on incorporating the F-wave characteristics into MND biomarkers. The neurophysiologic index was developed based on observations that declining CMAP amplitude, prolonging distal motor latency, and decreasing frequency of F-wave responses correlated with loss of muscle bulk and clinical weakness, ultimately described by the formula NPI = [CMAP amplitude/Distal Motor Latency] x (F-wave frequency over 20 recordings) [

37]. This index has proven to be well-correlated with muscle strength and is a more sensitive indicator of clinical decline than more traditional MND biomarkers like FVC and delta-ALSFRS-R [

38,

39]. Attention to other parameters of the F-wave, including the assessment of identical “repeater F-waves” have demonstrated differentiation of ALS patients from healthy controls depending on the muscle assessed. This is thought to be possibly related to the split-hand phenomenon when comparing the ADM and APB CMAPs and has generated an additional MUNE method from the F-wave data [

40,

41].

2.7. LMN Hyper-Excitability

Another characteristic of MND pathophysiology is the concomitant axonal hyperexcitability that generates fasciculation potentials. Many properties of axonal hyperexcitability have been explored, most notably the strength-duration time constant (SDTC) reflecting Na+ current permissibility and threshold electrotonus (TE) representing axonal membrane accommodation due to K+ currents [

42]. First described by Bostock and colleagues in 1995, the principle of threshold electrotonus is to evoke a submaximal CMAP at different initial stimulus intensities and add a second polarizing current pulse, which provides a threshold response-time curve reflecting accommodation of the nerve to the polarized current [

43]. In this study, ALS patients showed two populations of TE responses in contrast to both healthy and other-neurologic-condition controls – a greater threshold reduction than control suggesting hyper-excitability (deemed type I responders) or a rapid increase in threshold representing significant hyperpolarization (type II responders); both pathophysiologies are thought to reflect abnormal K+ channel conductance [

42,

43]. The strength-duration time constant (SDTC) describes the rate of stimulus current decline as duration of a threshold stimulation increases, which is dependent partially on Na+ channel conductance [

42]. Interestingly, the SDTC is increased in ALS patients compared with healthy controls, distinguishing those two groups even in early disease states when CMAP’s are in the normal range [

44]. Thus, the identification of electrophysiologic markers of axonal hyperexcitability has both garnered interest in its use as a clinical trial biomarker and as a therapeutic target in MND, given the hypothesized abnormal axonal ion channel conductance described.

2.8. Electrical Impedance Myography

While traditional NCS-based and MUNE tools have generated much interest in ALS research, a parallel investigation into the electrophysiologic properties of affected muscle has also garnered attention as a possible biomarker of MND. Electrical impedance myography (EIM) describes the electrophysiologic properties of a given muscle, namely the electrical resistance to low-intensity but high-frequency electrical current and the phase which is a measure of cell membrane integrity and its ability to alter the application of an alternating current [

45]. This tool is non-invasive, quick to use, and relies on the inherent architecture of the underlying muscle. The phase parameter showed promising sensitivity (90%) and specificity (100%) in differentiating ALS patients from healthy controls [

46]. Furthermore, the coefficient of variation of EIM when used to track the rate of decline in ALS out-performed that of hand-held dynamometry and the ALSFRS-R [

47]. It has been proposed that EIM when used as a biomarker of therapeutic target engagement could significantly reduce the number of patients required in future clinical trials when compared with the traditionally used ALSFRS-R [

47,

48]. Another highlight of the EIM technique is its ability to assess bulbar disease progression, which is more difficult to characterize by traditional clinical measures (i.e. bulbar sub-score of the ALSFRS-R, vital capacity measurements). EIM of the tongues of ALS patients demonstrates reduced phase and increased resistance compared with those of healthy controls [

49]. With the advent of improved computational processing, a new technique called Tensor-EIM characterizes a multi-directional assessment of tongue muscle electrical impedance [

50]. This tool was projected in a hypothetical clinical trial scenario to reduce the number of needed participants significantly compared with the ALSFRS-R bulbar sub-score in an ALS patient cohort [

50].

3. Upper Motor Neuron Assessment

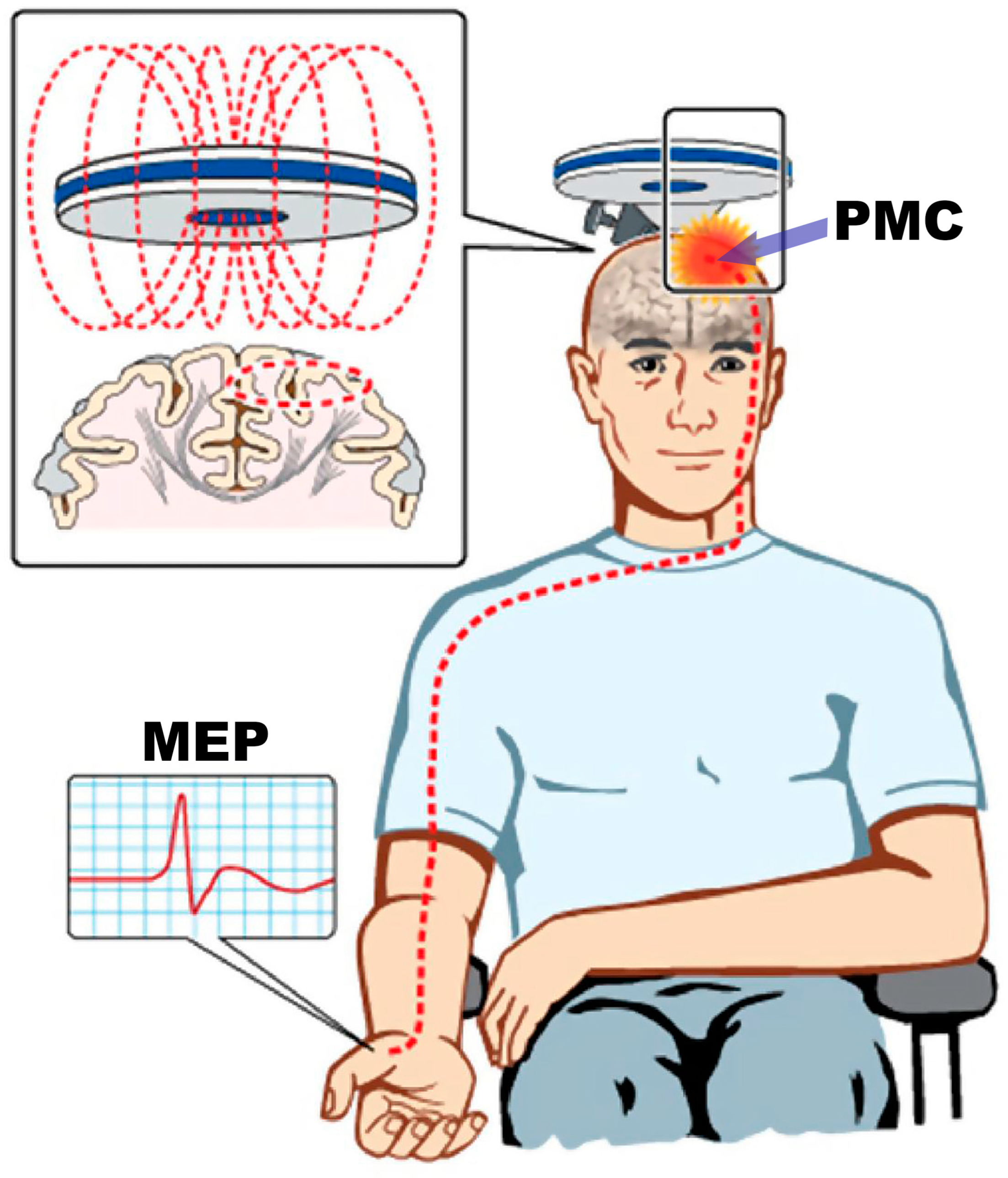

3.1. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (Single-Pulse and Paired-Pulse Models)

Though understanding of LMN dysfunction in ALS has been well characterized by traditional and research electrodiagnostic methods, the characteristics of upper motor neuron (UMN) pathophysiology remain challenging. At the time of this report, there is still no electrophysiologic tool to detect UMN dysfunction in routine clinical practice. Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a noninvasive method for understanding the pathophysiology of UMN dysfunction by using a targeted magnetic pulse to induce a stimulating electric current within the primary motor cortex. This in turn activates the corticomotoneuron pool and generates a motor evoked potential (MEP) in the relevant contralateral muscle [

51,

52]

(Figure 2)[

53].

Within the TMS literature, both single-pulse and multi-pulse paradigms have been used with success in differentiating ALS disease characteristics from controls. Single pulse TMS methods have demonstrated that patients with ALS have increased motor evoked potential (MEP) amplitudes and a steeper MEP response-curve when compared to healthy controls [

54] or disease mimics [

55]. Additional studies highlight that the cortical silent period, which is the duration of electromyographic silence following a TMS stimulus, is reduced significantly in ALS compared with both healthy controls and ALS disease mimics [

56]. Further work in paired-pulse TMS models by Vucic and colleagues, in which subthreshold conditioning stimuli are delivered at different interstimulus time intervals and the effect of that preconditioning stimulus on the amplitude of a second applied stimulus needed to generate a fixed MEP amplitude (called threshold-tracking TMS) is assessed, has further explored the underpinnings of UMN dysfunction in MND [

57].

Two promising threshold-tracking paired-pulse TMS parameters differentiating ALS from controls are short-interval cortical-inhibition (SICI) and intracortical facilitation (ICF). SICI which is described by the increase in the conditioned stimulus intensity needed to maintain a targeted MEP, is significantly reduced in ALS patients from control subjects, most prominently in patients with spinal-onset ALS [

57]. This reduced SICI period in ALS patients is followed by a period of increased ICF, which is manifested by a decrease in the stimulus intensity required to maintain the target MEP amplitude. These findings suggest underlying corticomotoneuronal signaling hyperexcitability [

57]. This has been validated by multiple groups in recent years, and that increased cortical hyperexcitability is correlated with shorter survival [

58,

59] as well as with ALS-associated cognitive impairment [

60]. Furthermore, Otani and colleagues combined the measures of elevated SDTC reflecting LMN hyperexcitability with reduction in SICI into a prognostic model showing ALS patients manifesting both central and peripheral hyperexcitability have significantly reduced survival compared to ALS patients with one or no hyperactive parameters[

59].

Additional work by Vucic and colleagues in symptomatic familial ALS (fALS) patients carrying the superoxide dismutase type 1 (SOD1) mutation revealed similar reduction in SICI and increased ICF in this specific cohort; asymptomatic SOD1 fALS patients also demonstrated significant reduction in SICI prior to development of clinical symptoms[

61]. This finding suggests that cortical hyperexcitability may precede clinical symptoms of ALS, which are manifestations of predominantly LMN death, the putative “dying forward hypothesis” [

61]. This technique has further evaluated the therapeutic effects of riluzole in significantly increasing SICI in patients with ALS treated with riluzole compared to untreated ones [

62]. Ultimately, this foundational work suggests that (a) corticomotoneuronal hyperexcitability may precede the clinical syndrome of ALS and differentiate such patients from controls, (b) this hyperexcitability can be modulated by approved ALS therapies, and (c) use of such techniques as a categorical and pharmacodynamic biomarkers in future clinical trials is warranted [

52,

63].

3.2. Peristimulus Time Histograms in ALS Patients

In addition to studying the MEP after applying TMS over a region of motor cortex, investigations led by Eisen and colleagues used the peristimulus time histogram (PSTH) technique to characterize the probability of firing a single voluntarily-activated motor unit after a single motor cortex directed impulse. This approach allows for the investigation of a small pool of TMS-activated corticomotoneurons and their converging excitatory post-synaptic potentials on the spinal motor neuron, which leads to changes in the firing probability of the respective motor unit [

64]. Normally, when a voluntarily recruited single motor unit encounters a TMS-induced corticomotoneuron volley, an increased probability of motor unit firing occurs with a latency of 20 milliseconds after the stimulation; this is the primary peak, which reflects the compound excitatory post-synaptic potential (EPSP) [

65]. In normal aging, there is a linear decline of the EPSP amplitude, while in purely lower motor neuron disorders there is no change to the EPSP [

65]. In ALS, multiple PSTH patterns have been demonstrated, likely reflecting differing time-points across disease progression. While most ALS patients exhibit a reduced or absent EPSP, another subset demonstrates higher than expected EPSP amplitudes for age [

65]. Later studies demonstrated a delay in the primary peak onset, increased temporal dispersion and more EPSP peak sub-components in the post-TMS corticomotoneuron volley period within ALS subjects [

66,

67]. These changes are theorized to reflect asynchronous temporal summation of the descending corticomotoneuron volley as well as increased repetitive firing of a hyperactive corticomotoneuronal pool in ALS [

67]. This method provides an additional way to study progression of UMN degeneration in ALS, and possibly serve as a pharmacodynamic biomarker of therapeutic target engagement in clinical trials.

3.3. High Density EEG and MEG

Given the known association of ALS with frontotemporal dementia, as well as the growing understanding of non-motor manifestations of ALS, it is important to assess the function of distributed brain networks in this condition. Resting state high density EEG (HDEEG) demonstrates increased connectivity across the fronto-central cerebrum of cognitively normal ALS patients thought to reflect pathologic hyperconnectivity within the Salience and Default Mode networks [

68]. Further studies into event-related potentials (ERPs) show that there are significant differences in mismatch negativity (an ERP reflecting the late potential difference between expected and deviant auditory tones) as well as in the sustained attention to response task network delineating ALS patients from healthy controls [

69,

70]

Magnetoencephalography (MEG) has also been useful in MND electrophysiology, as high-definition resolution of cortical beta band synchronization helps illuminate the role of this synchronization in movement preparation and execution, as well as the dysfunction of this local network in ALS [

71]. ALS patients demonstrate augmented beta band desynchronization in the bilateral motor cortex during movement preparation phase, followed by a delayed rebound of beta power after movement completion which is thought to reflect local cortical hyperexcitability [

71]. Like studies with EEG, resting-state MEG in ALS patients reveals diffusely increased connectivity throughout cortical networks, particularly within posterior cingulate cortex and its connections to the motor cortex [

72]. These tools can reliably differentiate ALS patients from healthy controls, sub-stratify disease subtypes based exclusively on unique cortical network abnormalities, and possibly serve as both categorical and pharmacodynamic biomarkers of ALS cortical dysfunction in clinical trials [

73].

4. Conclusion

ALS and related MNDs remain areas of intense research aimed at unraveling their complex pathophysiologies and developing effective therapies. The advancements in electrophysiologic techniques, including MUNE, MUNIX, MScanFit, EIM and TMS, have significantly enhanced our understanding of both UMN and LMN dysfunction. These methods offer promise not only in improving diagnostic accuracy and stratification but also in serving as sensitive biomarkers of disease progression and therapeutic target engagement. Furthermore, techniques like high-density EEG and MEG provide additional dimensions in tracking brain disease progression and even assessing non-motor manifestations of ALS. The integration of these advanced neurophysiologic tools into clinical trials has the potential to streamline the evaluation of therapeutic efficacy, ultimately accelerating the development of effective treatments for ALS and other MNDs. Continued research in this field is essential to refine these techniques and validate their clinical utility, bringing us closer to improving patient outcomes and quality of life.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conceptualization, preparation, and writing of this review. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in the preparation of this review. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xu, L.; Liu, T.; Liu, L.; Yao, X.; Chen, L.; Fan, D.; Zhan, S.; Wang, S. Global Variation in Prevalence and Incidence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Neurol 2020, 267, 944–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, H.; Rechtman, L.; Wagner, L.; Kaye, W. E. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Surveillance in Baltimore and Philadelphia. Muscle Nerve 2015, 51, 815–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logroscino, G.; Traynor, B. J.; Hardiman, O.; Chió, A.; Mitchell, D.; Swingler, R. J.; Millul, A.; Benn, E.; Beghi, E. Incidence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Europe. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2010, 81, 385–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camacho-Soto, A.; Searles Nielsen, S.; Faust, I. M.; Bucelli, R. C.; Miller, T. M.; Racette, B. A. Incidence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in Older Adults. Muscle Nerve 2022, 66, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfson, C.; Gauvin, D. E.; Ishola, F.; Oskoui, M. Global Prevalence and Incidence of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Neurology 2023, 101, E613–E623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, B.; et al. El Escorial World Federation of Neurology Criteria for the Diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 1994, 124, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rix Brooks, B.; Miller, R. G.; Swash, M.; Munsat, T. L. El Escorial Revisited: Revised Criteria for the Diagnosis of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. ALS and other motor neuron disorders 2000, 1, 293–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, M.; Dengler, R.; Eisen, A.; England, J. D.; Kaji, R.; Kimura, J.; Mills, K.; Mitsumoto, H.; Nodera, H.; Shefner, J.; Swash, M. Electrodiagnostic Criteria for Diagnosis of ALS. Clinical Neurophysiology 2008, 119, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shefner, J. M.; Al-Chalabi, A.; Baker, M. R.; Cui, L. Y.; de Carvalho, M.; Eisen, A.; Grosskreutz, J.; Hardiman, O.; Henderson, R.; Matamala, J. M.; Mitsumoto, H.; Paulus, W.; Simon, N.; Swash, M.; Talbot, K.; Turner, M. R.; Ugawa, Y.; van den Berg, L. H.; Verdugo, R.; Vucic, S.; Kaji, R.; Burke, D.; Kiernan, M. C. A Proposal for New Diagnostic Criteria for ALS. Clinical Neurophysiology 2020, 131, 1975–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedarbaum, J. M.; Stambler, N.; Malta, E.; Fuller, C.; Hilt, D. The ALSFRS-R: A Revised ALS Functional Rating Scale That Incorporates Assessments of Respiratory Function. J Neurol Sci 1999, 169, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verber, N. S.; Shepheard, S. R.; Sassani, M.; McDonough, H. E.; Moore, S. A.; Alix, J. J. P.; Wilkinson, I. D.; Jenkins, T. M.; Shaw, P. J. Biomarkers in Motor Neuron Disease: A State of the Art Review. Front Neurol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McComas, A. J.; Fawcett, P. R.; Campbell, M. J.; Sica, R. E. Electrophysiological Estimation of the Number of Motor Units within a Human Muscle. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1971, 34, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, W. F.; Milner-Brown, H. S. Some Electrical Properties of Motor Units and Their Effects on the Methods of Estimating Motor Unit Numbers. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1976, 39, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadrie, H. A.; Yates, S. K.; Milner-Brown, H. S.; Brown’, W. F.; Brown, W. F. Multiple Point Electrical Stimulation of Ulnar and Median Nerves. Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1976, 39, 973–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmouna, K.; Milants, C.; Wang, F. C. Correlations between MUNIX and Adapted Multiple Point Stimulation MUNE Methods. Clinical Neurophysiology 2018, 129, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandekar, S.; Nandekar, D.; Barkhaus, P.; Stalberg, E. Motor Unit Number Index (MUNIX). IEEE Trans Biomed Eng 2004, 51, 2211–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandedkar, S. D.; Barkhaus, P. E.; Stalberg, E. V. Motor Unit Number Index (MUNIX): Principle, Method, and Findings in Healthy Subjects and in Patients with Motor Neuron Disease. Muscle Nerve 2010, 42, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escorcio-Bezerra, M. L.; Abrahao, A.; de Castro, I.; Chieia, M. A. T.; de Azevedo, L. A.; Pinheiro, D. S.; de Oliveira Braga, N. I.; de Oliveira, A. S. B.; Manzano, G. M. MUNIX: Reproducibility and Clinical Correlations in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Clinical Neurophysiology 2016, 127, 2979–2984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuwirth, C.; Nandedkar, S.; Stålberg, E.; Weber, M. Motor Unit Number Index (MUNIX): A Novel Neurophysiological Technique to Follow Disease Progression in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2010, 42, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risi, B.; Cotti Piccinelli, S.; Gazzina, S.; Labella, B.; Caria, F.; Damioli, S.; Poli, L.; Padovani, A.; Filosto, M. Prognostic Usefulness of Motor Unit Number Index (MUNIX) in Patients Newly Diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Clin Med 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, A.; Kuwabara, S. The Split Hand Syndrome in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2012, 83, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilbourn, A. J. The “Split Hand Syndrome.”. Muscle Nerve 2000, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. G.; Hong, Y. ho; Shin, J. young; Park, K. H.; Sohn, S. Y.; Lee, K. W.; Park, K. S.; Sung, J. J. Split-Hand Phenomenon in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Motor Unit Number Index Study. Muscle Nerve 2016, 53, 885–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMackin, R.; Bede, P.; Ingre, C.; Malaspina, A.; Hardiman, O. Biomarkers in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Current Status and Future Prospects. Nat Rev Neurol 2023, 19, 754–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathi, D.; Mohammadi, B.; Dengler, R.; Böselt, S.; Petri, S.; Kollewe, K. Lower Motor Neuron Involvement in ALS Assessed by Motor Unit Number Index (MUNIX): Long-Term Changes and Reproducibility. Clinical Neurophysiology 2016, 127, 1984–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimaldi, S.; Duprat, L.; Grapperon, A. M.; Verschueren, A.; Delmont, E.; Attarian, S. Global Motor Unit Number Index Sum Score for Assessing the Loss of Lower Motor Neurons in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2017, 56, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuwirth, C.; Barkhaus, P. E.; Burkhardt, C.; Castro, J.; Czell, D.; de Carvalho, M.; Nandedkar, S.; Stålberg, E.; Weber, M. Motor Unit Number Index (MUNIX) Detects Motor Neuron Loss in Pre-Symptomatic Muscles in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Clinical Neurophysiology 2017, 128, 495–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucic, S.; Menon, P.; Huynh, W.; Mahoney, C.; Ho, K. S.; Hartford, A.; Rynders, A.; Evan, J.; Evan, J.; Ligozio, S.; Glanzman, R.; Hotchkin, M. T.; Kiernan, M. C. Efficacy and Safety of CNM-Au8 in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (RESCUE-ALS Study): A Phase 2, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial and Open Label Extension. Lancet 2023, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucic, S.; Kiernan, M. C. Nanocrystalline Gold (CNM-Au8): A Novel Bioenergetic Treatment for ALS. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2023, 32, 783–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geijo-Barrientos, E.; Pastore-Olmedo, C.; De Mingo, P.; Blanquer, M.; Gómez Espuch, J.; Iniesta, F.; Iniesta, N. G.; García-Hernández, A.; Martín-Estefanía, C.; Barrios, L.; Moraleda, J. M.; Martínez, S. Intramuscular Injection of Bone Marrow Stem Cells in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Front Neurosci 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingor, P.; Weber, M.; Camu, W.; Friede, T.; Hilgers, R.; Leha, A.; Neuwirth, C.; Günther, R.; Benatar, M.; Kuzma-Kozakiewicz, M.; Bidner, H.; Blankenstein, C.; Frontini, R.; Ludolph, A.; Koch, J. C. ROCK-ALS: Protocol for a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Phase IIa Trial of Safety, Tolerability and Efficacy of the Rho Kinase (ROCK) Inhibitor Fasudil in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front Neurol 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, J. C.; Kuttler, J.; Maass, F.; Lengenfeld, T.; Zielke, E.; Bähr, M.; Lingor, P. Compassionate Use of the ROCK Inhibitor Fasudil in Three Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front Neurol 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunes, T.; Sirin, N. G.; Sahin, S.; Kose, E.; Isak, B. Use of CMAP, MScan Fit-MUNE, and MUNIX in Understanding Neurodegeneration Pattern of ALS and Detection of Early Motor Neuron Loss in Daily Practice. Neurosci Lett 2021, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, A. B.; Bostock, H.; Fuglsang-Frederiksen, A.; Duez, L.; Beniczky, S.; Møller, A. T.; Blicher, J. U.; Tankisi, H. Reproducibility, and Sensitivity to Motor Unit Loss in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, of a Novel MUNE Method: MScanFit MUNE. Clinical Neurophysiology 2017, 128, 1380–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, A. B.; Bostock, H.; Tankisi, H. Following Disease Progression in Motor Neuron Disorders with 3 Motor Unit Number Estimation Methods. Muscle Nerve 2019, 59, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavey, N.; Hannaford, A.; Higashihara, M.; van den Bos, M.; Kiernan, M. C.; Menon, P.; Vucic, S. Utility of Split Hand Index with Different Motor Unit Number Estimation Techniques in ALS. Clinical Neurophysiology 2023, 156, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, M.; Swash, M. Nerve Conduction Studies in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2000, 23, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, M.; Scotto, M.; Lopes, A.; Swash, M. Clinical and Neurophysiological Evaluation of Progression in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2003, 28, 630–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swash, M.; de Carvalho, M. The Neurophysiological Index in ALS. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Other Motor Neuron Disorders 2004, 5 (SUPPL. 1), 108–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguz-Akarsu, E.; Sirin, N. G.; Kocasoy Orhan, E.; Erbas, B.; Dede, H. O.; Baslo, M. B.; Idrisoglu, H. A.; Oge, A. E. Repeater F-Waves in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Electrophysiologic Indicators of Upper or Lower Motor Neuron Involvement? Clinical Neurophysiology 2020, 131, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguz-Akarsu, E.; Sirin, N. G.; Artug, T.; Erbas, B.; Kocasoy Orhan, E.; Idrisoğlu, H. A.; Ketenci, A.; Baslo, M. B.; Oge, A. E. Automatic Detection of F Waves and F-MUNE in Two Types of Motor Neuron Diseases. Muscle Nerve 2022, 65, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, K.; Kuwabara, S.; Misawa, S.; Tamura, N.; Ogawara, K.; Nakata, M.; Sawai, S.; Hattori, T.; Bostock, H. Altered Axonal Excitability Properties in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Impaired Potassium Channel Function Related to Disease Stage. Brain 2006, 129, 953–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bostock, H.; Sharief, M. K.; Reid, G.; Murray, N. M. F. Axonal Ion Channel Dysfunction in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Brain 1995, 118, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lugg, A.; Schindle, M.; Sivak, A.; Tankisi, H.; Jones, K. E. Nerve Excitability Measured with the TROND Protocol in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Neurophysiol 2023, 130, 1480–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkove, S. B.; Aaron, R.; Shiffman, C. A. Localized Bioimpedance Analysis in the Evaluation of Neuromuscular Disease. Muscle Nerve 2002, 25, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarulli, A. W.; Garmirian, L. P.; Fogerson, P. M.; Rutkove, S. B. Localized Muscle Impedance Abnormalities in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2009, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutkove, S. Electrical Impedance Myography as a Biomarker for ALS. Lancet Neurol 2009, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkove, S. B.; Caress, J. B.; Cartwright, M. S.; Burns, T. M.; Warder, J.; David, W. S.; Goyal, N.; Maragakis, N. J.; Clawson, L.; Benatar, M.; Usher, S.; Sharma, K. R.; Gautam, S.; Narayanaswami, P.; Raynor, E. M.; Watson, M. Lou; Shefner, J. M. Electrical Impedance Myography as a Biomarker to Assess ALS Progression. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis 2012, 13, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shellikeri, S.; Yunusova, Y.; Green, J. R.; Pattee, G. L.; Berry, J. D.; Rutkove, S. B.; Zinman, L. Electrical Impedance Myography in the Evaluation of the Tongue Musculature in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 2015, 52, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schooling, C. N.; Healey, T. J.; McDonough, H. E.; French, S. J.; McDermott, C. J.; Shaw, P. J.; Kadirkamanathan, V.; Alix, J. J. P. Tensor Electrical Impedance Myography Identifies Bulbar Disease Progression in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Clinical Neurophysiology 2022, 139, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, A.; Freeston, I.; Jalinous, R.; Jarratt Sheffield, J. Non-Invasive Stimulation of Motor Pathways within the Brain Using Time-Varying Magnetic Fields. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucic, S.; Kiernan, M. C. Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation for the Assessment of Neurodegenerative Disease. Neurotherapeutics 2017, 14, 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vucic, S.; Ziemann, U.; Eisen, A.; Hallett, M.; Kiernan, M. C. ranscranial Magnetic Stimulation and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Pathophysiological Insights. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. BMJ Publishing Group 2013, pp 1161–1170. [CrossRef]

- Zanette, G.; Tamburin, S.; Manganotti, P.; Refatti, N.; Forgione, A.; Rizzuto, N. Different Mechanisms Contribute to Motor Cortex Hyperexcitability in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Clinical Neurophysiology 2002, 113, 1688–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucic, S.; Kiernan, M. C. Cortical Excitability Testing Distinguishes Kennedy’s Disease from Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Clinical Neurophysiology 2008, 119, 1088–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vucic, S.; Cheah, B. C.; Yiannikas, C.; Kiernan, M. C. Cortical Excitability Distinguishes ALS from Mimic Disorders. Clinical Neurophysiology 2011, 122, 1860–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vucic, S.; Kiernan, M. C. Novel Threshold Tracking Techniques Suggest That Cortical Hyperexcitability Is an Early Feature of Motor Neuron Disease. Brain 2006, 129, 2436–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, Y. I.; Shibuya, K.; Misawa, S.; Suichi, T.; Tsuneyama, A.; Kojima, Y.; Nakamura, K.; Kano, H.; Prado, M.; Aotsuka, Y.; Otani, R.; Morooka, M.; Kuwabara, S. Relationship between Motor Cortical and Peripheral Axonal Hyperexcitability in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2022, 93, 1074–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otani, R.; Shibuya, K.; Suzuki, Y. I.; Suichi, T.; Morooka, M.; Aotsuka, Y.; Ogushi, M.; Kuwabara, S. Effects of Motor Cortical and Peripheral Axonal Hyperexcitability on Survival in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2024, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higashihara, M.; Pavey, N.; Van Den Bos, M.; Menon, P.; Kiernan, M. C.; Vucic, S. Association of Cortical Hyperexcitability and Cognitive Impairment in Patients With Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurology 2021, 96, E2090–E2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vucic, S.; Nicholson, G. A.; Kiernan, M. C. Cortical Hyperexcitability May Precede the Onset of Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Brain 2008, 131, 1540–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vucic, S.; Lin, C. S. Y.; Cheah, B. C.; Murray, J.; Menon, P.; Krishnan, A. V.; Kiernan, M. C. Riluzole Exerts Central and Peripheral Modulating Effects in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Brain 2013, 136, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmins, H. C.; Vucic, S.; Kiernan, M. C. Cortical Hyperexcitability in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: From Pathogenesis to Diagnosis. Curr Opin Neurol 2023, 36, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, M.; Eisen, A. Peristimulus Time Histograms (PSTHs)-a Marker for Upper Motor Neuron Involvement in ALS? ALS and other motor neuron disorders 2000, S51–S55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, A.; Entezari-Taher, M.; Stewart, H. Cortical Projections to Spinal Rnotoneurons: Changes with Aging and Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurology 1996, 46, 1396–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M.; Eisen, A.; Stewart, H. Comparison of Corticomotoneuronal EPSPs and Macro-MUPs in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Muscle Nerve 1998, 21, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisen, A.; Nakajima, M.; Weber, M. Corticomotorneuronal Hyper-Excitability in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 1998, 160, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, P. M.; Egan, C.; Pinto-Grau, M.; Burke, T.; Elamin, M.; Nasseroleslami, B.; Pender, N.; Lalor, E. C.; Hardiman, O. Functional Connectivity Changes in Resting-State EEG as Potential Biomarker for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. PLoS One 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, P. M.; Mohr, K.; Broderick, M.; Gavin, B.; Burke, T.; Bede, P.; Pinto-Grau, M.; Pender, N. P.; McLaughlin, R.; Vajda, A.; Heverin, M.; Lalor, E. C.; Hardiman, O.; Nasseroleslami, B. Mismatch Negativity as an Indicator of Cognitive Sub-Domain Dysfunction in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Front Neurol 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMackin, R.; Dukic, S.; Costello, E.; Pinto-Grau, M.; Fasano, A.; Buxo, T.; Heverin, M.; Reilly, R.; Muthuraman, M.; Pender, N.; Hardiman, O.; Nasseroleslami, B. Localization of Brain Networks Engaged by the Sustained Attention to Response Task Provides Quantitative Markers of Executive Impairment in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cerebral Cortex 2020, 30, 4834–4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, M.; Rohenkohl, G.; Quinn, A.; Colclough, G. L.; Wuu, J.; Talbot, K.; Woolrich, M. W.; Benatar, M.; Nobre, A. C.; Turner, M. R. Altered Cortical Beta-Band Oscillations Reflect Motor System Degeneration in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Hum Brain Mapp 2017, 38, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, M.; Colclough, G. L.; Quinn, A.; Wuu, J.; Talbot, K.; Benatar, M.; Nobre, A. C.; Woolrich, M. W.; Turner, M. R. Increased Cerebral Functional Connectivity in ALS: A Resting-State Magnetoencephalography Study. Neurology 2018, 90, E1418–E1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dukic, S.; McMackin, R.; Costello, E.; Metzger, M.; Buxo, T.; Fasano, A.; Chipika, R.; Pinto-Grau, M.; Schuster, C.; Hammond, M.; Heverin, M.; Coffey, A.; Broderick, M.; Iyer, P. M.; Mohr, K.; Gavin, B.; McLaughlin, R.; Pender, N.; Bede, P.; Muthuraman, M.; Van Den Berg, L. H.; Hardiman, O.; Nasseroleslami, B. Resting-State EEG Reveals Four Subphenotypes of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Brain 2022, 145, 621–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).