1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of degenerative dementia, typically starting with subtle memory deficits

[1]. Unfortunately, AD is still underdiagnosed in the community

[2] despite 14 modifiable risk factors for developing dementia have been identified (including less education, hypertension, high LDL cholesterol, diabetes, obesity, smoking, excessive alcohol consumption, depression, physical inactivity, traumatic brain injury, air pollution, hearing and visual loss, and social isolation) and up to 45% of dementia cases could be prevented if prevention policies were implemented

[3][4]. Furthermore, several disease-modifying therapies for AD (monoclonal antibodies against beta-amyloid) have shown evidence of amyloid removal from the brain and modest slowing of cognitive decline, and have been recently approved for clinical use worldwide

[5]. In this scenario, detecting the initial symptoms of AD, such as memory loss or executive deficits, is crucial for enabling prompt intervention and management strategies to slow down the progression of cognitive decline and, consequently, improve the patient’s quality of life.

Our team at Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona has recently developed the online FACEmemory

® platform

[6] in response to the growing need for earlier detection of cognitive impairment and the increasing interest in new technologies. Initially released in 2015 as an in-person test with minimal supervision

[7], an optimized, fully online became freely accessible to the community in 2021

[6]. FACEmemory is the first completely self-administered verbal episodic memory test with voice recognition and automatic scoring

[6]. When tested at Ace Alzheimer Center in Barcelona with minimal supervision, the FACEmemory automatic scoring was proven to be reliable for detecting mild cognitive impairment (MCI), particularly the amnestic type

[7], which is at higher risk of progressing to AD dementia

[8]. Additionally, FACEmemory scoring has been linked to AD phenotype and biomarkers in late and early-onset cases

[7][9].

Aimed at reducing underdiagnoses of cognitive impairment and AD

[2], the online FACEmemory platform has reached over 3,000 adults from 37 different countries in just 1.5 years, with 82.10% reporting memory concerns

[6], a known risk factor for AD in individuals over 60

[10]. In our center, we had experience with the usefulness of an open house initiative (a screening strategy to help patients assess their memory easily without visiting their physician) to engage people with SCD

[11] and MCI

[12] in memory clinics. FACEmemory, derived from the FNAME-12

[13] (the abbreviated version of the Face-Name Associative Memory Exam (FNAME)

[14]), offers a promising pre-screening tool for individuals with SCD and MCI. However, it may be too complex for individuals with dementia, who usually obtain ground scores

[13].

In line with the theory that distinct cognitive processes play a role in different stages of memory

[15], a Machine Learning (ML) analysis demonstrated that FACEmemory subscores allowed the distinction of four different memory patterns: preserved execution, and storage, dysexecutive, and global memory impairments

[6]. These findings can potentially improve early detection of cognitive impairment in individuals over 50 by enhancing conventional clinical assessments.

In the present study, we aim to compare data collected through the online FACEmemory platform with information obtained from a formal cognitive assessment at a memory clinic to help identify individuals with MCI earlier. Specifically, the main objectives of this study are: 1) to disentangle the neuropsychological correlates of FACEmemory subscores with results from traditional paper-and-pencil neuropsychological tests and 2) to develop the most optimal algorithm using FACEmemory data and demographics to distinguish between cognitively healthy (CH) individuals and those with MCI.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

All individuals over the age of 50 who had completed the online FACEmemory platform and the diagnosis evaluation at Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona’s Memory Unit within 6 months, and who were diagnosed with either CH or MCI between June 2021 and May 2024, were included in the present study. Individuals showing evidence of impairment in their activities of daily living (dementia diagnosis), or who had severe auditory or visual impairments, were excluded from the study. Demographic information (age, sex, and years of formal education) was collected from all individuals.

2.2. The FACEmemory® Platform

As mentioned elsewhere [

6], the FACEmemory

® platform is available free of charge to individuals interested in a memory assessment. It can be used on a tablet or computer with voice recognition and an internet connection.

Upon accessing the FACEmemory platform, users are asked to select the preferred language of administration (Spanish or Catalan), accept informed consent for completing the test, and provide demographic information (i.e., age, sex, schooling, the country from which they are completing the test) and an e-mail address to receive their results. Additionally, subjective memory complaints and associated worries are assessed with three questions: 1. “Do you feel that your memory has worsened?” (yes/no); 2. “Are you worried about it?” (yes/no), and 3. “Since when have you noticed it?” (in years). Then, the FACEmemory is introduced through a brief video, followed by an audio test to ensure proper voice recognition for optimal self-administration.

FACEmemory is a memory test that includes two learning trials, a short-term memory task, and a long-term memory task that includes face, name, and occupation memory recognition. The first and second learning trials (Learning 1 and Learning 2) each consist of 12 faces, associated with a name and an occupation appearing beneath it for 8 seconds. The process is repeated, but the sequence of the faces is changed. The user is instructed to read the name and occupation beneath each face aloud and to try to remember them. Then, the application prompts the user to press the red microphone button and say the name and occupation associated with each face they remember.

A short-term memory task (Short-term) begins two minutes after the second learning trial. The user is instructed to press the red microphone button and say the name and occupation associated with each face shown on the screen. Finally, the long-term memory assessment (Long-term) begins 15 minutes after the second learning trial, including free recall and recognition tasks. First, the user is presented with three faces and is asked to select the one that appeared in the learning trials (Face Recognition). Upon selection, the correct face is displayed, and the user is prompted to say the name and occupation associated with each face. After providing their answer, a screen appears with the correct face and two rows below it, each containing 3-name and 3-occupation options. The users are instructed to select the name and occupation that they recall being associated with the face (Recognitions).

Once the short-term memory test is completed, participants are asked to fill out a medical and family history questionnaire used in the Open House Initiative (OHI questionnaire) [

11]. However, since the main goal is to administer the FACEmemory test in a standardized manner, completing the OHI questionnaire is not mandatory. If a user does not complete the questionnaire within the assigned time, the system automatically proceeds to the FACEmemory long-term recall tasks.

All subscores range from 0 to 12. The total score, the sum of all subscores, ranges from 0 to 132. As reported previously [

7], the sum of all free recalled subscores (excluding Face Recognition and Recognitions -FR, REN, and REO-) was also calculated from 0 to 96. The time taken to complete the FACEmemory test was recorded in minutes. Additionally, derived subscores were calculated, including the number of consecutive failures and omissions (instances where a previously correctly recalled name or occupation was subsequently failed).

After completing the FACEmemory test, the user cannot re-access it for one year. Eleven months after completing the test, the user receives an invitation via their registered e-mail to complete it again. An alternative test form (A or B) is provided to avoid practice effects.

2.3. Diagnosis Evaluation

All participants underwent the diagnosis evaluation at Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona’s Memory Clinic [

16], which included a social worker interview with an informant, a neurological examination, and a complete neuropsychological assessment using the Neuropsychological Battery of Ace (NBACE©), with normative data [

17] and cut-off scores for impairment [

18]. The NBACE includes measures of cognitive information processing speed, orientation, attention, verbal learning and long-term memory, language, praxis, and visuospatial, visuoperceptual, and executive functions [

17].

The clinical diagnosis for CH individuals, with or without subjective memory complaints, was determined as follows: they had an absence of objective cognitive impairment, with preserved scores on NBACE [

18][

17]; normal global cognition (the Spanish version of Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score ≥ 27) [

19,

20]; a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) [

21] score of 0; and no history of functional impairment resulting from cognitive decline, with a score below 4 on the Blessed Dementia Rating Scale (BDRS) [

22,

23]. The clinical diagnosis for patients with MCI included: subjective cognitive complaints, preserved global cognition (MMSE score ≥ 24), normal performance in activities of daily living (a BDRS score of less than 4), absence of dementia, a CDR score of 0.5, and an objectively measurable impairment in memory and/or another cognitive function (amnestic MCI -aMCI- or non-amnestic MCI -naMCI-) using NBACE [

24][

8].

2.4. Statistical and Descriptive Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26 for Windows (version 26.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and Python version 3.11.7. All data were examined for normality, skewness, and restriction of range.

Descriptive analyses were conducted using t-test and chi-square test to compare FACEmemory, demographic, clinical, memory complaints, and medical history variables between CH and MCI groups.

Pearson partial correlations between FACEmemory variables and neuropsychological composites derived from NBACE were performed, using age, sex, and years of schooling as covariates. The neuropsychological composites were estimated via structural equation modeling (SEM) following the procedure outlined elsewhere [

25]. Seven composites were considered. The grouping of the NBACE variables within each cognitive domain was informed by exploratory factor analysis and expert consensus. The memory composite was generated from the long-term and recognition memory variables of the Word List subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale, third edition (WMS-III). Attention function was assessed using the Digit Forward and Digit Backward subtests from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, third edition (WAIS-III). The visuospatial/visuoperceptive function composite included the 15-Objects Test [

26,

27], Poppelreuter-type overlap figures, and Luria’s Clock Test. The executive function composite was constructed from the Phonetic and Semantic Verbal Fluencies and the Automatic Inhibition subtest of the Syndrom Kurtz Test (SKT). The language function composite included the abbreviated Boston Naming Test with 15 items (15-BNT) and the Verbal Comprehension and Repetition tests. The reality orientation composite was calculated from the Temporal, Spatial, and Personal orientation tests. Finally, the praxis composite was based on the Imitation, Ideomotor, and Block Design tests.

The SEM models were fitted using robust maximum likelihood estimation except for the orientation and praxis composites, which, due to their ordinal distribution, were calculated using a weighted least square mean, and variance-adjusted estimator. The variances of the latent variables were fixed at 1 for model identification [

28]. The R package lavaan was utilized to calculate the composites [

29].

For all the analyses, an effect was considered significant when p < 0.05, and all hypotheses were tested bidirectionally at a 95% confidence level.

2.5. FACEmemory for Classification Between CH and MCI

To search for an algorithm able to discriminate between CH and MCI (all MCI, aMCI, or naMCI) groups, ML techniques were applied using the FACEmemory variables. Additionally, demographic information (age, sex, and schooling) was included as input variables to evaluate the performance of the ML model trained solely on FACEmemory variables with those trained on a combination of FACEmemory variables and demographic information.

For the classification tasks (CH-MCI, CH-aMCI, and CH-naMCI), the following ML models were used: k-nearest neighbor (KNN), decision tree (DT), support vector machine (SVM), random forest (RF), and extreme gradient boosting (XGB). Cross-validation (CV) with class stratification was used to ensure balanced representation. Model performance was assessed using sensitivity, specificity, and balanced accuracy (BA). The input variables were standardized to z-scores based on the training data statistics.

The hyperparameters of the ML model were determined using hyperparameter optimization (HPO) with nested cross-validation, within a defined search space.

Appendix A provides an overview of the hyperparameter search space used for the machine learning models. The hyperparameters for each model are outlined in the corresponding tables: the KNN model in

Table A6, the DT model in

Table A7, the SVM model in

Table A8, the RF model in

Table A9, and the XGB model in

Table A10 (

Appendix A). The outer cross-validation consisted of five folds, while the inner cross-validation also utilized five folds for HPO. The nested CV models were used to predict the test sets, and the final performance metrics were calculated as the average performance on these predictions. The HPO was implemented using the Optuna open-source library [

30], applying a Bayesian optimization (BO) using a tree-structured Parzen estimator (TPE) as a surrogate model [

31]. In the HPO CV, the balanced accuracy of the validation sets was maximized.

The performance of the ML models was assessed relative to a baseline cutoff model, which differentiated diagnostic groups using a threshold on the FACEmemory total score. This threshold was optimized to maximize balanced accuracy.

All models were implemented using Python. The scikit-learn library was utilized for RF, KNN, and SVM algorithms [

32]. The xgboost package [

33] was employed for the XGB models.

Additionally, the models were trained using the subscores of the test up to each block, as described in

Table 2. So, we obtained models that had only been trained with data up to a certain point of the test. It allowed us to distinguish between the different diagnostic groups without having all the test information. This approach enables us to determine whether the test duration could be shortened or if the test duration has already been optimized. This methodology also facilitates the potential to evaluate whether we could provide results for individuals who could not complete the test for any reason. While there is not a widely standardized name for this feature selection method, it shares characteristics with Blockwise Feature Selection [

34].

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive

A total of 669 individuals (251 men and 418 women) were included in this study. Their mean age was 68.4 (with a standard deviation, SD, of 8.7), ranging from 50 to 93 years old. Most (98.1%) participants had at least 6 years of formal education, with 58% having completed elementary or high school, 40.1% holding a university degree, and only 1.9% having less than elementary school education. 62.6% (419 subjects) completed the FACEmemory in Spanish and 250 subjects in Catalan. Most (94.5%) participants reported subjective memory complaints with associated worries. Regarding the diagnoses assigned after the clinical evaluation at Ace’s Memory Clinic, 266 subjects were classified as CH and 403 as MCI (206 naMCI and 197 aMCI), with a mean scoring on the MMSE of 29.3 and 28.2, respectively (for details, see

Table 1 and

Table 3). The average time between the FACEmemory test and the diagnostic evaluation was 5.2 days (SD: 54.0).

As detailed in

Table 2, the MCI group performed significantly worse on FACEmemory variables than the CH, with a mean difference of 21 points in the total score. As shown in

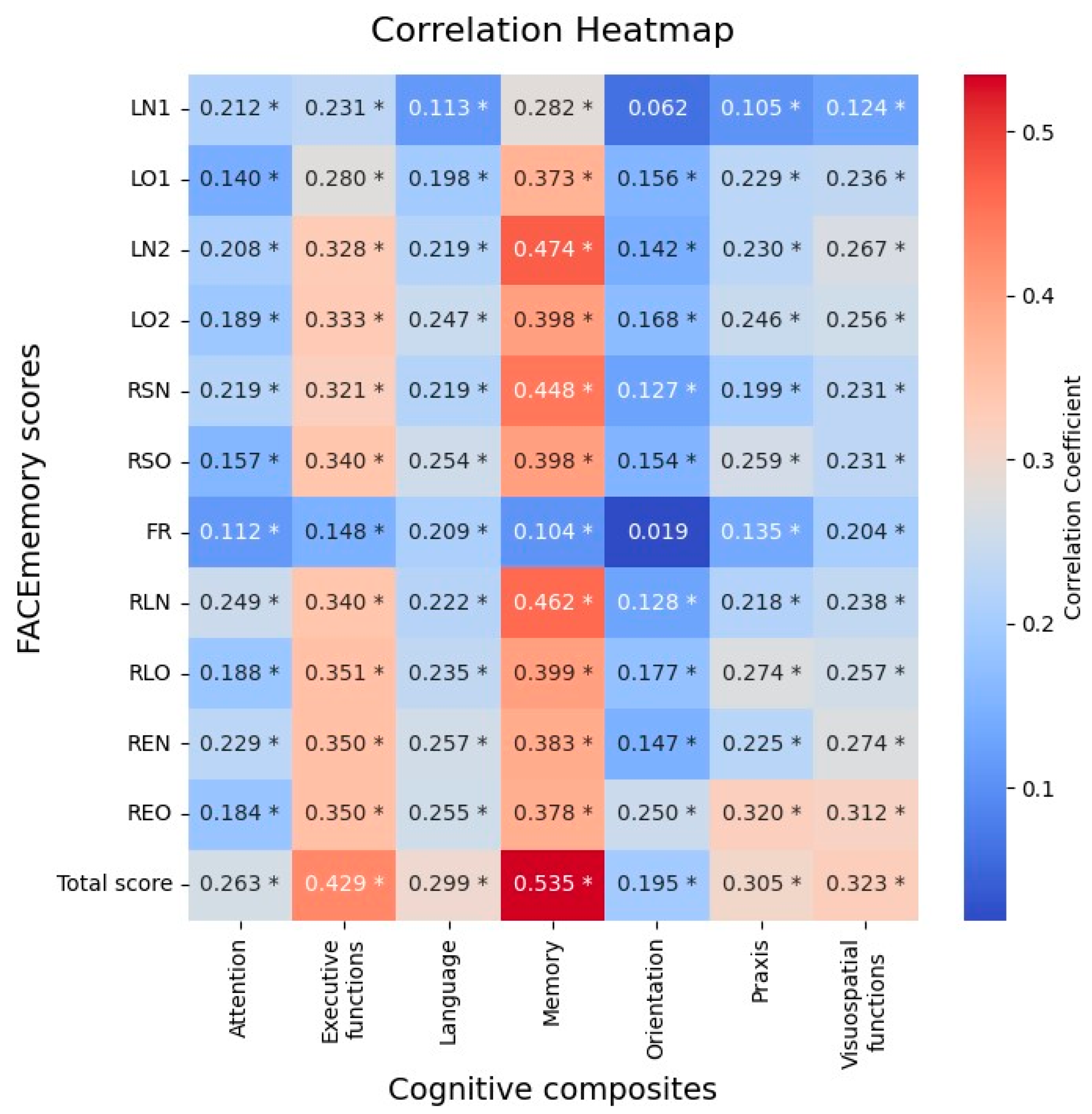

Table 3, there was a progressive worsening from CH, naMCI to aMCI groups. Pearson’s partial correlation analyses between FACEmemory scores and NBACE composites, covariated by age, schooling and sex, showed statistically significant correlations of FACEmemory with memory (r= 0.53, p < 0.001), executive functions (r= 0.43, p < 0.001), visuospatial/visuoperceptual (r= 0.32, p < 0.001), language (r= 0.30, p < 0.001), praxis (r= 0.30, p < 0.001) and attention (r= 0.26, p < 0.001) domains (

Figure 1).

Table 2.

Performance on FACEmemory subscores and total scores.

Table 2.

Performance on FACEmemory subscores and total scores.

| FACEmemory block |

Variable

(min-max) |

Whole sample (mean, SD) |

CH (mean, SD) |

MCI (mean, SD) |

Statistics (1) |

| Learning 1 |

LN1 (0-12) |

1.43 (2.14) |

2.23 (2.43) |

0.90 (1.73) |

8.26 * |

| LO1 (0-12) |

3.89 (2.74) |

5.00 (2.69) |

3.16 (2.52) |

8.99 * |

| CFN1 (0-6) |

5.51 (1.18) |

5.17 (1.46) |

5.73 (0.89) |

6.16 * |

| CFO1 (0-6) |

4.11 (1.90) |

3.43 (1.99) |

4.56 (1.69) |

7.88 * |

| Learning 2 |

LN2 (0-12) |

3.69 (3.27) |

5.36 (3.32) |

2.59 (2.72) |

11.79 * |

| LO2 (0-12) |

6.25 (3.11) |

7.52 (2.79) |

5.42 (3.02) |

9.07 * |

| CFN2 (0-6) |

4.05 (2.05) |

3.07 (2.14) |

4.69 (1.70) |

10.86 * |

| CFO2 (0-6) |

2.46 (2.08) |

1.71 (1.83) |

2.95 (2.09) |

7.88 * |

| Short-term |

RSN (0-12) |

3.38 (3.27) |

5.00 (3.48) |

2.31 (2.63) |

11.36 * |

| RSO (0-12) |

6.12 (3.10) |

7.41 (2.78) |

5.26 (3.00) |

9.33 * |

| CFN3 (0-6) |

4.36 (2.01) |

3.47 (2.22) |

4.94 (1.61) |

9.91 * |

| CFO3 (0-6) |

2.60 (2.08) |

1.85 (1.91) |

3.09 (2.04) |

7.89 * |

| Face Recognition |

FR (0-12) |

11.88 (0.49) |

11.94 (0.26) |

11.84 (0.59) |

2.60 * |

| Long-term |

RLN (0-12) |

3.17 (3.26) |

4.86 (3.45) |

2.05 (2.58) |

12.03 * |

| RLO (0-12) |

5.57 (3.28) |

7.02 (2.90) |

4.62 (3.17) |

9.91 * |

| CFN4 (0-6) |

4.38 (2.03) |

3.40 (2.24) |

5.03 (1.58) |

11.03 * |

| CFO4 (0-6) |

2.96 (2.17) |

2.12 (1.94) |

3.51 (2.13) |

8.55 * |

| Recognitions |

REN (0-12) |

8.56 (3.09) |

9.97 (2.40) |

7.64 (3.14) |

10.28 * |

| REO (0-12) |

11.11 (1.53) |

11.62 (0.86) |

10.78 (1.76) |

7.23 * |

| NO (0-18) |

2.87 (3.02) |

3.35 (3.01) |

2.56 (2.99) |

3.33 * |

| OO (0-23) |

5.83 (3.52) |

6.03 (3.71) |

5.70 (3.40) |

1.18 |

| |

Total score* (0-132) |

65.06 (22.79) |

77.93 (20.50) |

56.58 (20.12) |

13.33 * |

| Execution time (in min) |

25.38 (6.47) |

23.62 (5.76) |

26.53 (6.65) |

5.83 * |

3.2. FACEmemory for the Discrimination Between MCI Subgroups

With regard to the MCI subgroups, the aMCI and naMCI groups did not differ in age, sex, or schooling. However, the aMCI showed a statistically significant worse performance on MMSE and FACEmemory, with average scores 1 and 12 points lower, respectively (

Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the MCI group, stratified by amnestic and non-amnestic subtypes. .

Table 3.

Clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the MCI group, stratified by amnestic and non-amnestic subtypes. .

| |

naMCI |

aMCI |

Statistics |

| Sample size (N) |

206 |

197 |

|

| Age (mean, SD) |

70.00 (9.45) |

69.34 (8.67) |

0.72 (1) |

| Sex (N, % woman) |

135 (65.53) |

117 (59.39) |

1.62 (2) |

| Years of formal education (mean, SD) |

11.44 (4.49) |

10.84 (4.40) |

1.35 (1) |

| MMSE (mean, SD) |

28.60 (1.33) |

27.78 (1.57) |

5.66 (1)* |

| FACEmemory Total score (mean, SD) |

62.84 (19.83) |

50.08 (18.26) |

6.71 (1)* |

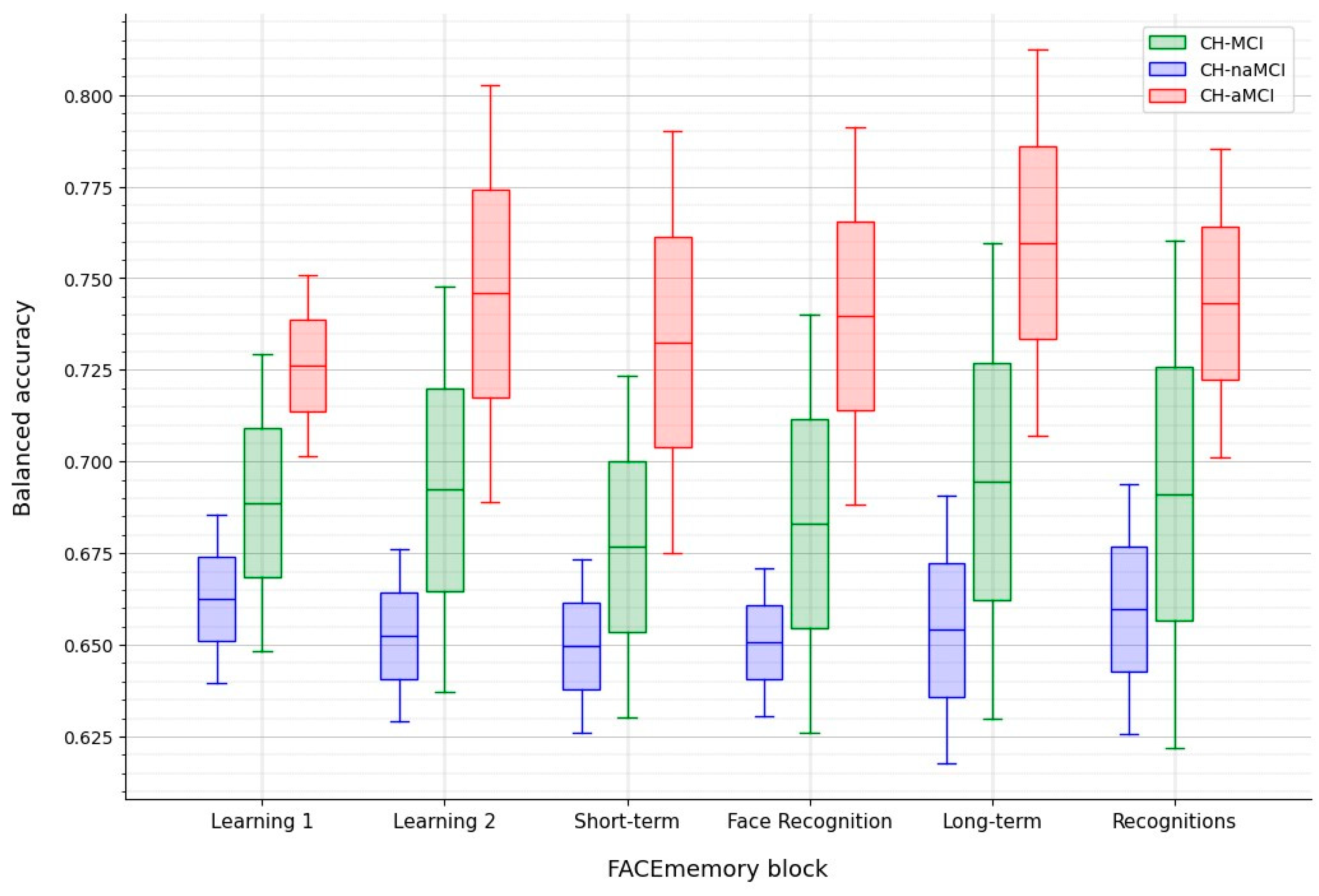

To discriminate between CH and MCI (all MCI, naMCI, or aMCI), the model that maximized the BA was chosen.

The best performance was achieved at the Long-term block for distinguishing between CH and aMCI. In contrast, the most effective approach for differentiating CH and naMCI was using data up to Face Recognition using an RF model with subscores and demographic features. Adding demographic information did not enhance the CH and aMCI classification but improved the CH and naMCI classification. At the Learning 2 block, the CH-aMCI classification reached a BA of 0.74, while the Long-term block achieved the highest BA of 0.76. The model using the cumulative score up to the Long-term block performed best in distinguishing between CH and aMCI (

Table 4).

The total FACEmemory

® cutoff between CH and aMCI was reported to maximize the BA. A total FACEmemory cutoff of 44.5 achieved sensitivity and specificity values of 0.81 and 0.72, respectively (

Table 4 and

Figure 2). Without the Face Recognition and Recognition blocks, a cutoff of 33.5 achieved sensitivity and specificity values of 0.82 and 0.70, respectively.

4. Discussion

The results of the present study confirm that the FACEmemory is a promising online tool for identifying people with early cognitive impairment in the community. The FACEmemory tracked cognitive progression and achieved sensitivity and specificity values that enable CH and MCI discrimination, mainly in detecting the amnestic type. Thus, this tool can identify cognitive impairment including aMCI and dementia, particularly AD, in the community. It represents an opportunity to reduce the current underdiagnosis of cognitive impairment and AD [

2]. The novelty of this study lies in the fact that this optimized version of the FACEmemory consists of a web-based complex memory test that covers all memory processes, including learning, long-term memory, and recognition memory. Importantly, individuals can perform this test independently, even at home, without requiring supervision from a specialist [

6].

FACEmemory is derived from the FNAME-12 [

13], a cognitive test with 12 face-name-occupation-associated items for learning. It was developed to identify the early stages of AD, including preclinical and prodromal phases, and to track cognitive progression [

13]. Similar to the previous version of FACEmemory [

7], performance on the online FACEmemory worsened progressively from CH individuals to those with naMCI and aMCI, indicating a gradual decline in complex memory function from normal aging to aMCI, which carries an increased risk of conversion to dementia, mainly AD [

8]. Although the effects of age, schooling, and sex can vary depending on the study sample, our results are consistent with those reporting that worse associative memory performances on the original FNAME-12 and the computerized FACEmemory were related to lower education levels and older age, but not to sex [

9][

13].

In exploring the neuropsychological correlates of FACEmemory scoring with those obtained using traditional paper-and-pencil neuropsychological tests, the total FACEmemory score (including recognition tasks) was found to be related to all cognitive domains, showing moderate correlations with memory and executive functions, and weak correlations with visuospatial/visuoperceptual, language, praxis and attention domains. The finding that FACEmemory scoring was related not only to memory but also to other cognitive domains, primarily executive functions, aligns with the notion that distinct cognitive processes support different stages of memory execution [

15]. Moreover, it must be considered that this online version of FACEmemory is a complex episodic memory test offered on a web-based platform to be completely self-performed [

6]. Thus, its complexity requires the preservation of various cognitive domains.

Additionally, a recent systematic review that compared different digital cognitive biomarkers from computerized tests to detect MCI and dementia, including the FACEmemory with minimal supervision [

7], demonstrated that digital cognitive biomarkers related to memory and executive functions were more sensitive than those related to other cognitive domains [

35]. Therefore, the findings of the present study reinforce the idea that FACEmemory may be a valuable tool for detecting not only cognitive impairment but also individuals with very mild MCI (less impaired than MCI) as named by Dr. Frank Jessen [

10].

The comparison of ML models to identify the best algorithm to discriminate between CH and MCI (all MCI, aMCI, or naMCI) groups using cumulative FACEmemory subscores (with and without demographics) showed that the best performance was achieved including the long-term memory scores, particularly for CH vs aMCI group. Although worse FACEmemory scores were associated with lower education levels and older age, adding demographic information to the algorithm did not enhance the classification between CH and aMCI. Consistent with its nature as a test of episodic memory, these results emphasize the importance of maintaining long-term memory tasks, despite the extra 15 minutes required. These findings confirm the optimal test duration as originally designed by our team [

7], based on neuropsychological principles [

13].

Furthermore, the baseline model based on a cutoff on the FACEmemory score showed the best performance for the CH-aMCI classification. A cutoff score of 44.5 points (up to the Long-term block) achieved sensitivity and specificity values of 0.81 and 0.72, respectively. Our previous study calculated the FACEmemory cutoff score for impairment of 31.5 (without recognition tasks) in the CH and aMCI classification [

7]. In the present study, the cutoff score without recognition tasks was 33.5, with sensitivity and specificity values of 0.82 and 0.70, respectively.

An interesting finding of ML analyses was that models trained with data up to the two face-name learning trials (Learning 1 and 2), as well as those trained up to the face-name long-term memory (Long-term) showed similar discriminant performance than the baseline models for classifying CH and MCI. Given that the main aim of the FACEmemory platform is to detect cognitive impairment, this finding supports the platform’s potential to provide results for individuals unable to complete the test for any reason.

We acknowledge several limitations in this study. First, although FACEmemory was offered at no cost to the community, only data from individuals who were also evaluated at Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona’s Memory Clinic were analysed, making it a single-center study; but being potentially extensible to other centers. Second, we cannot rule out that those CH individuals with low FACEmemory scores may have preclinical AD. However, AD-related biomarkers are not currently approved for clinical use in normal aging. Third, this is a cross-sectional study. Further, longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether lower baseline scores on FACEmemory® are associated with an increased risk of developing dementia or AD and whether individuals who progress to dementia show a decline in FACEmemory scores over time while non-converters show stable scores.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, FACEmemory has proven to be a promising online tool for identifying individuals with MCI, particularly the amnestic subtype, within the community; and for tracking cognitive progression from normal aging to aMCI. It offers an opportunity for individuals worried about their memory to comfortably perform this prescreening memory test at home using an electronic device and an internet connection, without needing to visit a healthcare professional. FACEmemory could play a key role in reducing the underdiagnosis of AD and supporting early intervention efforts in the community.

6. Patents

The FACEmemory® is copyrighted by Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona and is made freely available for noncommercial purposes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and design of the study: MA, MB, AR, MM and DMR. Writing of the main manuscript text: MA, JBF. Analysis and interpretation of the data: JBF, FGG, MA, SV, EAM. Enrollment and assessment of participants at the Memory Clinic of Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona: MA, AP, GO, NM, AE, AS, SG, MM, IH, CR, AM, CA, MRR, JPT, LV. Critical review of the manuscript and approval of the final version: all authors. FACEmemory is copyrighted by ACE and is made freely available for noncommercial purposes.

Funding

This work was funded by the research funds of Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona, and was partially supported by funding from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) Acción Estratégica en Salud, integrated into the Spanish National RCDCI Plan and financed by ISCIII-Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) grants PI22/01403 and PI19/00335; project TARTAGLIA, Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation R&D Missions in the Artificial Intelligence program, Spain Digital 2025 Agenda and the National Artificial Intelligence Strategy and financed by the European Union through Next Generation EU funds, under the grant Nº MIA.2021.M02.0005; and from some sponsors (Grifols SA, Life Molecular Imaging GmbH, Araclon Biotech, Laboratorios Echevarne S.A. and Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona). MB, AR, MM and MA acknowledge the support of the Spanish ISCIII, Acción Estratégica en Salud, integrated in the Spanish National R+D+I Plan and financed by ISCIII Subdirección General de Evaluación and the Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER “Una manera de hacer Europa”) grants PI13/02434, PI16/01861, PI17/01474, PI19/01240, PI19/01301, PI19/00335 PI22/00258 and the ISCIII national grant PMP22/00022, funded by the European Union (NextGenerationEU). The support of CIBERNED (ISCIII) under the grants CB06/05/2004 and CB18/05/00010. The support from the ADAPTED and MOPEAD projects, European Union/EFPIA Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint (grant numbers 115975 and 115985, respectively); from PREADAPT project, Joint Program for Neurodegenerative Diseases (JPND) grant Nº AC19/00097; from HARPONE project, Agency for Innovation and Entrepreneurship (VLAIO) grant Nº PR067/21 and Janssen. DESCARTES project is funded by German Research Foundation (DFG).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and Spanish biomedical laws (Law 14/2007, July 3, about biomedical research; Royal Decree 1716/2011, November 18). The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Bellvitge Hospital on December 5, 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants provided written informed consent before the assessment.

Data Availability Statement

Data used can be requested through the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We want to express our gratitude to everyone who completed FACEmemory®. Without their collaboration, this work would not have been possible. Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona is a member of Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red sobre Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CIBERNED), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades. We also want to thank Raul Espinosa for his support and persistence in finding a way to automate and optimize the tool, Xavier Manrubia from Editorial Glosa, Pau Plana and Martin Dans from 3iPunt Solucions Informàtiques, and all the personnel from Ace Alzheimer Center Barcelona for their constant collaboration and intellectual input.

Conflicts of Interest

MB has consulted for Araclon, Avid, Grifols, Lilly, Nutricia, Roche, Eisai and Servier. She received fees from lectures and funds for research from Araclon, Biogen, Grifols, Nutricia, Roche and Servier. She reports grants/research funding from Abbvie, Araclon, Biogen Research Limited, Bioiberica, Grifols, Lilly, S.A, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, Laboratorios Servier, Nutricia SRL, Oryzon Genomics, Piramal Imaging Limited, Roche Pharma SA, and Schwabe Farma Iberica SLU, all outside the submitted work. She has not received personal compensations from these organizations. AR is member of scientific advisory board of Landsteiner Genmed and Grifols SA. AR has stocks of Landsteiner Genmed. MM has consulted for F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. and is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of Biomarkers of Araclon. The rest of the authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix A Provides an Overview of the Hyperparameter Search Space Used for the Machine Learning Models

Table A6.

Table 6. Hyperparameters of KNN.

Table A6.

Table 6. Hyperparameters of KNN.

| Hyperparameter |

Range |

|

| n_neighbors |

[2, 100] |

|

| weights |

{uniform, distance} |

|

| algorithm |

{auto, ball_tree, kd_tree, brute} |

|

| leaf_size |

[10, 100] |

|

| p |

[1, 5] |

|

Table A7.

Hyperparameters of DT.

Table A7.

Hyperparameters of DT.

| Hyperparameter |

Range |

| max_depth |

[2, 15] |

| min_samples_split |

[0.01, 0.5] |

| min_samples_leaf |

[0.01, 0.5] |

| max_features |

[0.5, 1] |

| max_samples |

[0.5, 1] |

| ccp_alpha |

[1e-6, 0.5] |

| citerion |

{gini, entropy} |

| class_weight |

{balanced} |

Table A8.

Hyperparameters of SVM.

Table A8.

Hyperparameters of SVM.

| Hyperparameter |

Range |

| C |

[1e-5, 1e2] |

| gamma |

[1e-5, 1e2] |

| kernel |

{rbf} |

| class_weight |

{balanced} |

Table A9.

Hyperparameters of RF.

Table A9.

Hyperparameters of RF.

| Hyperparameter |

Range |

| max_depth |

[2, 15] |

| min_samples_split |

[0.01, 0.2] |

| min_samples_leaf |

[0.01, 0.2] |

| max_features |

[0.5, 1] |

| max_samples |

[0.5, 1] |

| ccp_alpha |

[1e-6, 0.5] |

| n_estimators |

200 |

| class_weight |

{balanced_subsample} |

Table A10.

Hyperparameters of XGB.

Table A10.

Hyperparameters of XGB.

| Hyperparameter |

Range |

| max_depth |

[2, 15] |

| learning_rate |

[1e-2, 0.3] |

| gamma |

[1e-6, 100] |

| min_child_weight |

[0, 100] |

| subsample |

[0.2, 1] |

| colsample_bytree |

[0.2, 1] |

| colsample_bynode |

[0.2, 1] |

| reg_alpha |

[0.1, 10] |

| reg_lambda |

[0.1, 10] |

| scale_pos_weight |

[0.1, 10] |

| n_estimators |

200 |

References

- Werheid, K.; Clare, L. Are faces special in Alzheimer’s disease? Cognitive conceptualisation, neural correlates, and diagnostic relevance of impaired memory for faces and names. Cortex 2007, 43, 898–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 1598–695. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-X.; Tian, Y.; Wang, Z.-T.; Ma, Y.-H.; Tan, L.; Yu, J.-T. The Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s Disease Modifiable Risk Factors and Prevention. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2021, 8, 313–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Costafreda, S.G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet 2024, 404, 572–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.; Apostolova, L.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Atri, A.; Aisen, P.; Greenberg, S.; et al. Lecanemab: Appropriate Use Recommendations. J. Prev. Alzheimers Dis. 2023, 10, 362–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegret, M.; García-Gutiérrez, F.; Muñoz, N.; Espinosa, A.; Ortega, G.; Lleonart, N.; et al. FACEmemory®, an Innovative Online Platform for Episodic Memory Pre-Screening: Findings from the First 3,000 Participants. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2024, 97, 1173–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegret, M.; Muñoz, N.; Roberto, N.; Rentz, D.M.; Valero, S.; Gil, S.; et al. A computerized version of the Short Form of the Face-Name Associative Memory Exam (FACEmemory®) for the early detection of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2020, 12, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, A.; Alegret, M.; Valero, S.; Vinyes-Junqué, G.; Hernández, I.; Mauleón, A.; et al. A Longitudinal Follow-Up of 550 Mild Cognitive Impairment Patients: Evidence for Large Conversion to Dementia Rates and Detection of Major Risk Factors Involved. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2013, 34, 769–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegret, M.; Sotolongo-Grau, O.; de Antonio, E.E.; Pérez-Cordón, A.; Orellana, A.; Espinosa, A.; et al. Automatized FACEmemory® scoring is related to Alzheimer’s disease phenotype and biomarkers in early-onset mild cognitive impairment: the BIOFACE cohort. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessen, F.; Amariglio, R.E.; van Boxtel, M.; Breteler, M.; Ceccaldi, M.; Chételat, G.; et al. A conceptual framework for research on subjective cognitive decline in preclinical Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014, 10, 844–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelnour, C.; Rodríguez-Gómez, O.; Alegret, M.; Valero, S.; Moreno-Grau, S.; Sanabria, Á.; et al. Impact of Recruitment Methods in Subjective Cognitive Decline. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2017, 57, 625–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegret, M.; Rodríguez, O.; Espinosa, A.; Ortega, G.; Sanabria, A.; Valero, S.; et al. Concordance between Subjective and Objective Memory Impairment in Volunteer Subjects. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2015, 48, 1109–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papp, K.V.; Amariglio, R.E.; Dekhtyar, M.; Roy, K.; Wigman, S.; Bamfo, R.; et al. Development of a Psychometrically Equivalent Short Form of the Face–Name Associative Memory Exam for use Along the Early Alzheimer’s Disease Trajectory. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2014, 28, 771–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amariglio, R.E.; Frishe, K.; Olson, L.E.; Wadsworth, L.P.; Lorius, N.; Sperling, R.A.; et al. Validation of the Face Name Associative Memory Exam in cognitively normal older individuals. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2012, 34, 580–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolk, D.A.; Dickerson, B.C. Fractionating verbal episodic memory in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage 2011, 54, 1530–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boada, M.; Tárraga, L.; Hernández, I.; Valero, S.; Alegret, M.; Ruiz, A.; et al. Design of a comprehensive Alzheimer’s disease clinic and research center in Spain to meet critical patient and family needs. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014, 10, 409–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegret, M.; Espinosa, A.; Vinyes-Junqué, G.; Valero, S.; Hernández, I.; Tárraga, L.; et al. Normative data of a brief neuropsychological battery for Spanish individuals older than 49. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2012, 34, 209–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegret, M.; Espinosa, A.; Valero, S.; Vinyes-Junqué, G.; Ruiz, A.; Hernández, I.; et al. Cut-off Scores of a Brief Neuropsychological Battery (NBACE) for Spanish Individual Adults Older than 44 Years Old. PLoS One 2013, 8, e76436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blesa, R.; Pujol, M.; Aguilar, M.; Santacruz, P.; Bertran-Serra, I.; Hernández, G.; et al. Clinical validity of the “mini-mental state” for Spanish speaking communities. Neuropsychologia 2001, 39, 1150–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-mental state.” A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.C. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology 1993, 43, 2412–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blessed, G.; Tomlinson, B.E.; Roth, M. The Association Between Quantitative Measures of Dementia and of Senile Change in the Cerebral Grey Matter of Elderly Subjects. Br. J. Psychiatry 1968, 114, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peña-Casanova, J.; Aguilar, M.; Bertran-Serra, I.; Santacruz, P.; Hernandez, G.; Insa, R.; et al. [Normalization of cognitive and functional assessment instruments for dementia (NORMACODEM) (I): objectives, content and population]. Neurologia 1997, 12, 61–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Petersen, R.C. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J. Intern. Med. 2004, 256, 183–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Gutiérrez, F.; Alegret, M.; Marquié, M.; Muñoz, N.; Ortega, G.; Cano, A.; et al. Unveiling the sound of the cognitive status: Machine Learning-based speech analysis in the Alzheimer’s disease spectrum. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 2024, 16, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillon, B.; Dubois, B.; Bonnet, A.-M.; Esteguy, M.; Guimaraes, J.; Vigouret, J.-M.; et al. Cognitive slowing in Parkinson’s disease fails to respond to levodopa treatment. Neurology 1989, 39, 762–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegret, M.; Boada-Rovira, M.M.; Vinyes-Junqué, G.; Valero, S.; Espinosa, A.; Hernández, I.; et al. Detection of visuoperceptual deficits in preclinical and mild Alzheimer’s disease. J. Clin. Exp. Neuropsychol. 2009, 31, 860–7, Available from: PubMed Abstract. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. An Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling; 2021; pp. 1–29.

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 2623–31. [Google Scholar]

- Bergstra, J.; Bardenet, R.; Bengio, Y.; Kégl, B. Algorithms for hyper-parameter optimization. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2011, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Buitinck, L.; Louppe, G.; Blondel, M.; Pedregosa, F.; Mueller, A.; Grisel, O.; et al. API design for machine learning software: experiences from the scikit-learn project. arXiv preprint arXiv:13090238 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–94. [Google Scholar]

- Jenul, A.; Schrunner, S.; Pilz, J.; Tomic, O. A user-guided Bayesian framework for ensemble feature selection in life science applications (UBayFS). Mach. Learn. 2022, 111, 3897–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Lee, T.; Chan, A.S. Digital Cognitive Biomarker for Mild Cognitive Impairments and Dementia: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).