Submitted:

01 November 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets and Simulation Procedure

2.1.1. Data to Train the Diffusion Model

2.1.2. Data for Evaluating Longitudinal Power

2.1.3. Data to Evaluating Harmonization Performance

2.2. Image Analysis and Simulation

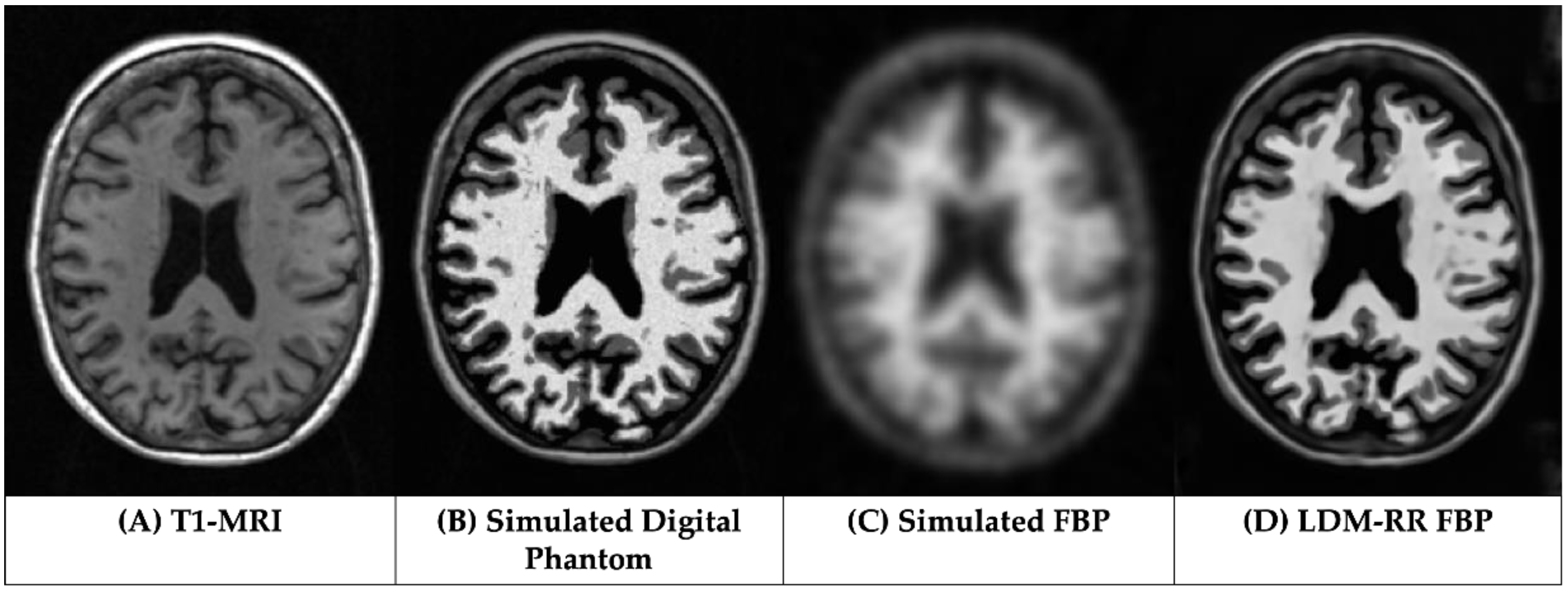

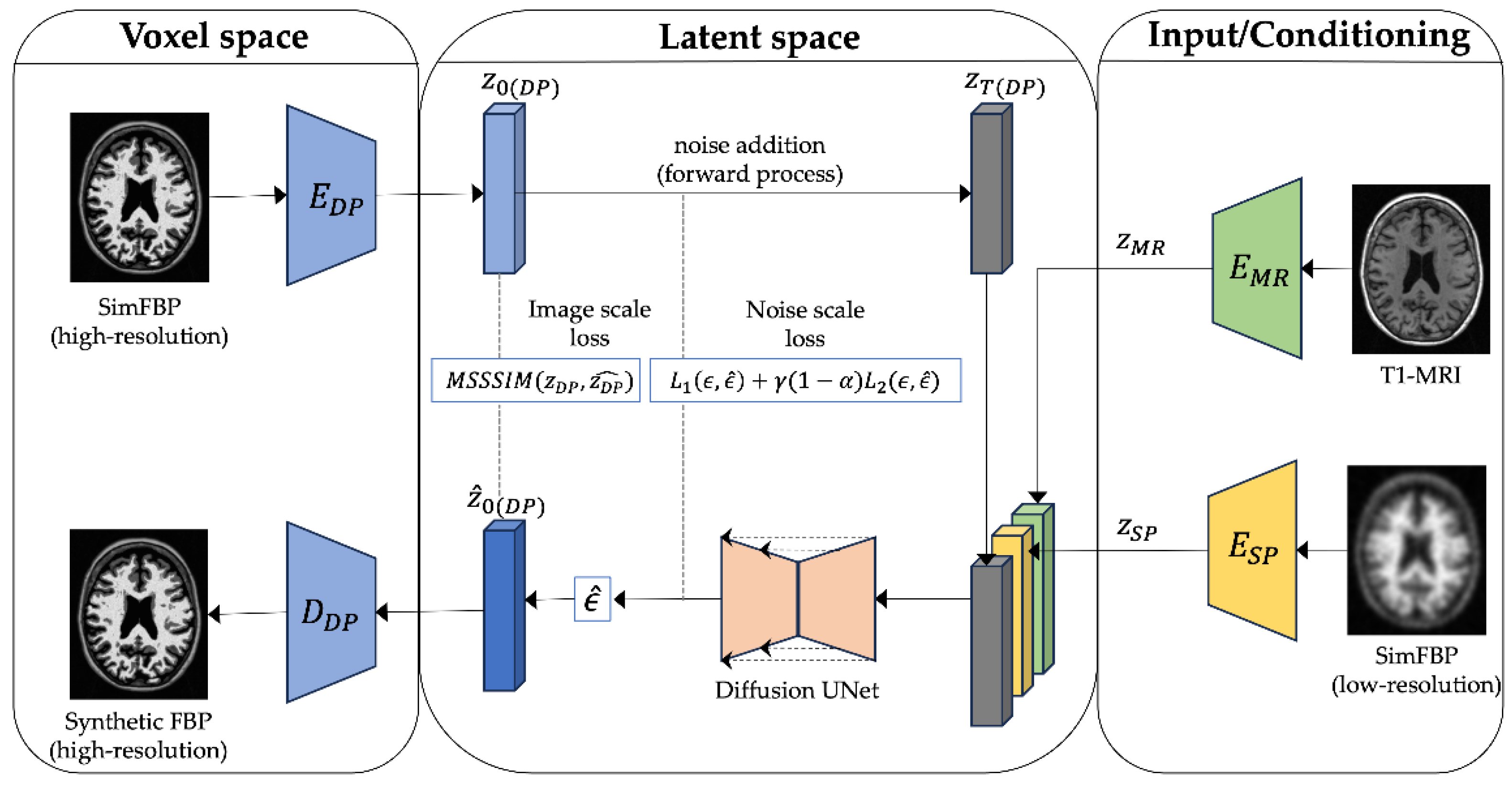

2.3. LDM-RR: PET Resolution Recovery Framework

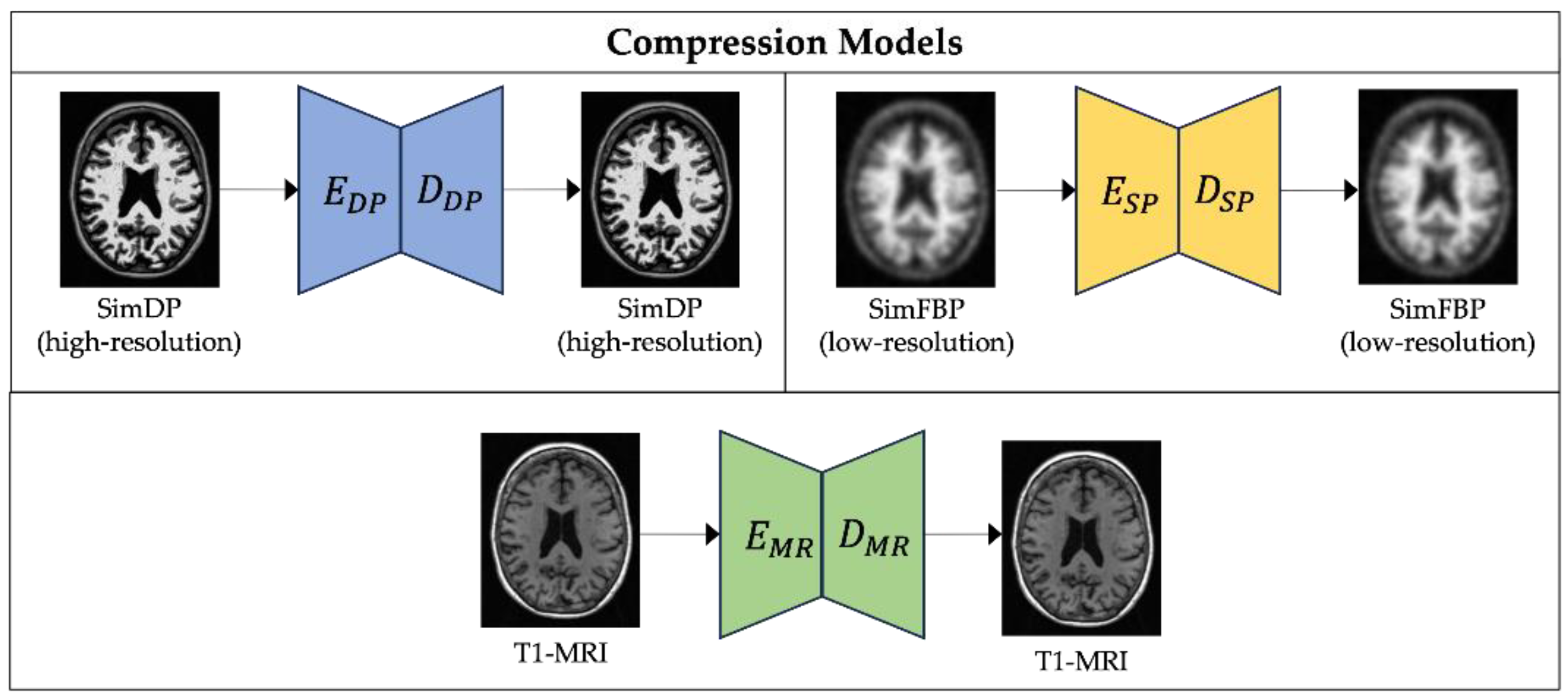

2.3.1. Compression Models

2.3.2. Diffusion Model

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.4.1. Simulated Data Analysis

2.4.2. Longitudinal Analysis

2.4.3. Cross-Tracer Analysis

3. Results

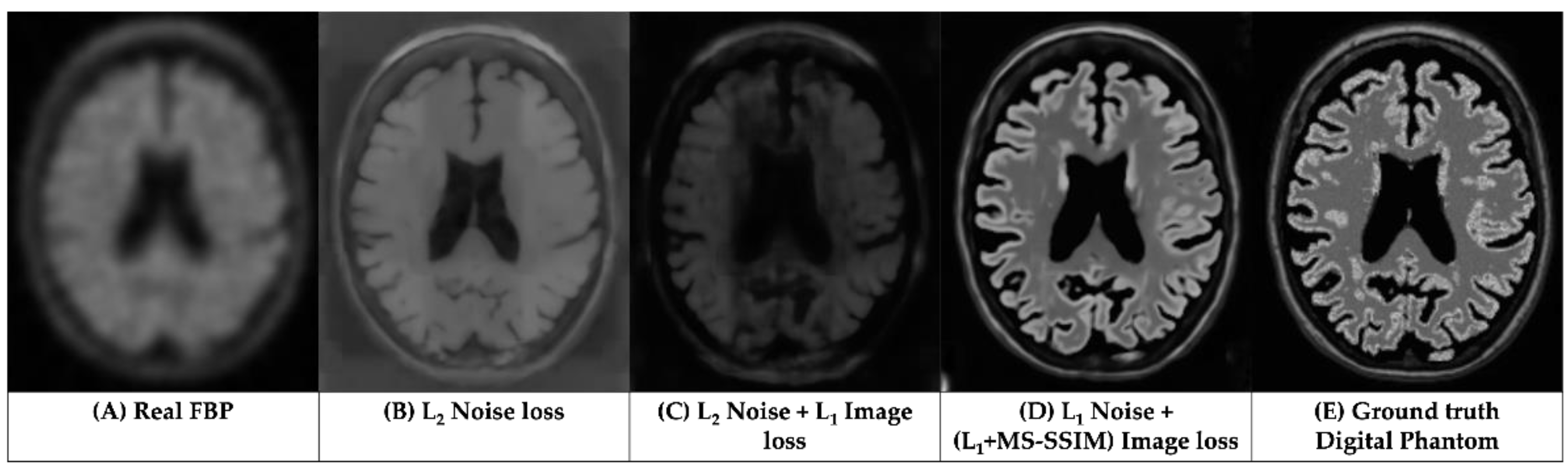

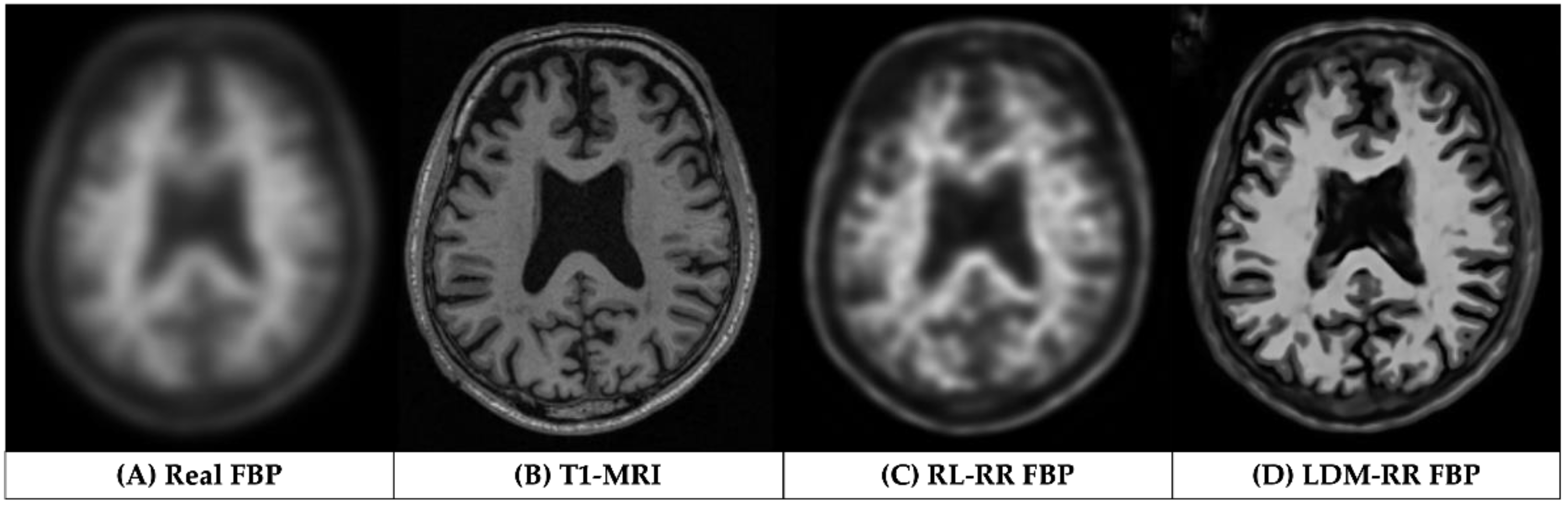

3.1. Qualitative Assessments

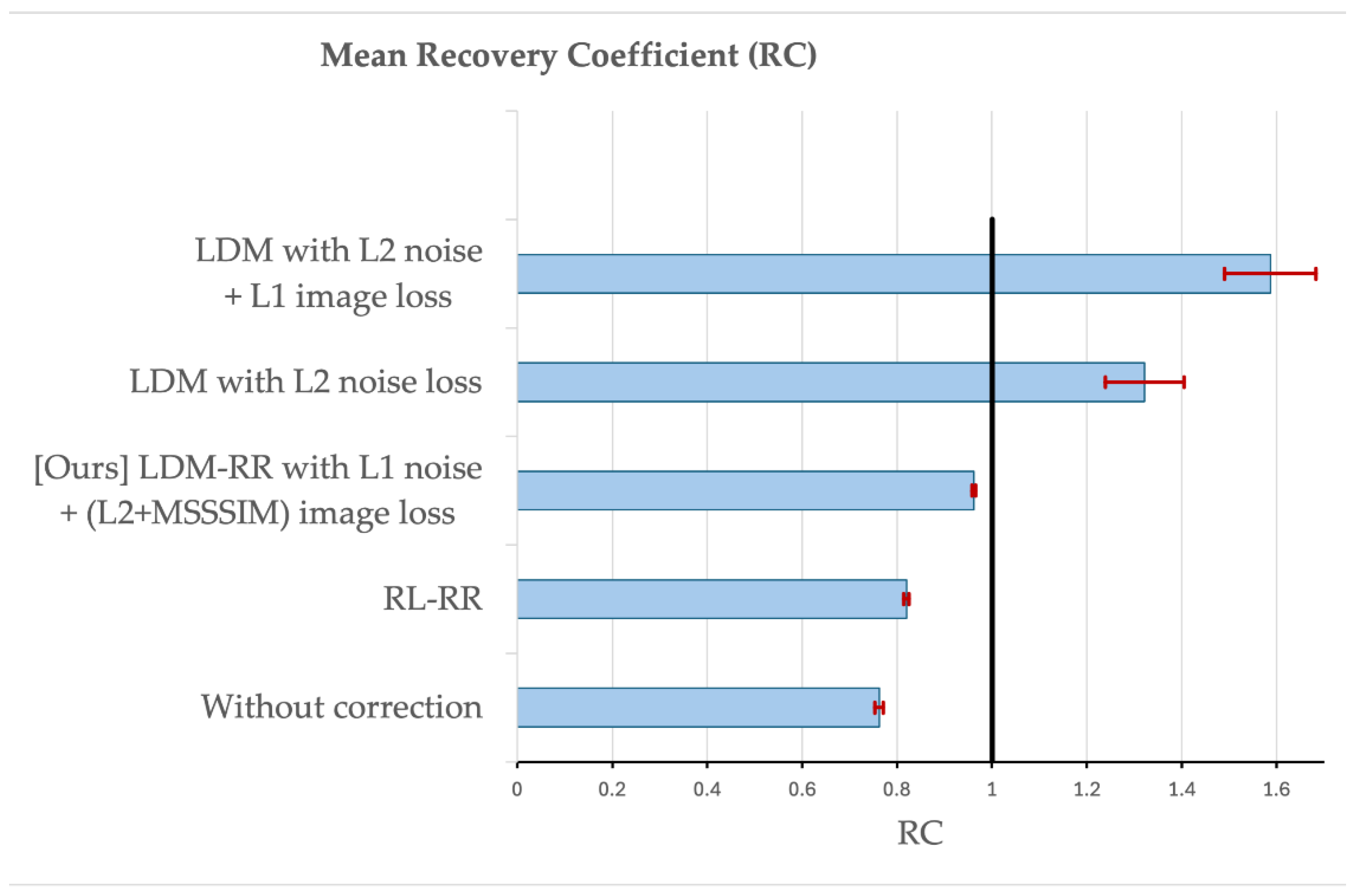

3.2. Evaluation on Simulated Data

3.2. Evaluation on Real Longitudial Amyloid PET Data

3.3. Evaluation on Real Cross-Tracer Amyloid PET Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Appendix A

Appendix B

| 1 |

References

- Chapleau, M.; Iaccarino, L.; Soleimani-Meigooni, D.; Rabinovici, G.D. The Role of Amyloid PET in Imaging Neurodegenerative Disorders: A Review. J Nucl Med 2022, 63, 13S–19S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, B.A.; Erlandsson, K.; Modat, M.; Thurfjell, L.; Vandenberghe, R.; Ourselin, S.; Hutton, B.F. The Importance of Appropriate Partial Volume Correction for PET Quantification in Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011, 38, 1104–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffman, E.J.; Huang, S.-C.; Phelps, M.E. Quantitation in Positron Emission Computed Tomography: 1. Effect of Object Size. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography 1979, 3, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Koeppe, R.A.; Fessler, J.A. Reducing between Scanner Differences in Multi-Center PET Studies. Neuroimage 2009, 46, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klunk, W.E.; Koeppe, R.A.; Price, J.C.; Benzinger, T.; Devous, M.D.; Jagust, W.; Johnson, K.; Mathis, C.A.; Minhas, D.; Pontecorvo, M.J.; et al. The Centiloid Project: Standardizing Quantitative Amyloid Plaque Estimation by PET. Alzheimers Dement 2015, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Ghisays, V.; Luo, J.; Chen, Y.; Lee, W.; Wu, T.; Reiman, E.M.; Su, Y. Harmonizing Florbetapir and PiB PET Measurements of Cortical Aβ Plaque Burden Using Multiple Regions-of-Interest and Machine Learning Techniques: An Alternative to the Centiloid Approach. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2024, 20, 2165–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.; Gao, F.; Li, B.; Ghisays, V.; Luo, J.; Chen, Y.; Lee, W.; Zhou, Y.; Benzinger, T.L.S.; Reiman, E.M.; et al. Deep Residual Inception Encoder-Decoder Network for Amyloid PET Harmonization. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2022, 18, 2448–2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, J.; Chen, K.; Reiman, E.M.; Li, B.; Wu, T.; Su, Y. Transfer Learning Based Deep Encoder Decoder Network for Amyloid PET Harmonization with Small Datasets. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2023, 19, e062947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessio, A.M.; Kinahan, P.E. Improved Quantitation for PET/CT Image Reconstruction with System Modeling and Anatomical Priors. Medical Physics 2006, 33, 4095–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baete, K.; Nuyts, J.; Laere, K.V.; Van Paesschen, W.; Ceyssens, S.; De Ceuninck, L.; Gheysens, O.; Kelles, A.; Van den Eynden, J.; Suetens, P.; et al. Evaluation of Anatomy Based Reconstruction for Partial Volume Correction in Brain FDG-PET. NeuroImage 2004, 23, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erlandsson, K.; Dickson, J.; Arridge, S.; Atkinson, D.; Ourselin, S.; Hutton, B.F. MR Imaging–Guided Partial Volume Correction of PET Data in PET/MR Imaging. PET Clinics 2016, 11, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meltzer, C.C.; Leal, J.P.; Mayberg, H.S.; Wagner, H.N.J.; Frost, J.J. Correction of PET Data for Partial Volume Effects in Human Cerebral Cortex by MR Imaging. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography 1990, 14, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller-Gärtner, H.W.; Links, J.M.; Prince, J.L.; Bryan, R.N.; McVeigh, E.; Leal, J.P.; Davatzikos, C.; Frost, J.J. Measurement of Radiotracer Concentration in Brain Gray Matter Using Positron Emission Tomography: MRI-Based Correction for Partial Volume Effects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1992, 12, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussel, O.G.; Ma, Y.; Evans, A.C. Correction for Partial Volume Effects in PET: Principle and Validation.

- Shidahara, M.; Tsoumpas, C.; Hammers, A.; Boussion, N.; Visvikis, D.; Suhara, T.; Kanno, I.; Turkheimer, F.E. Functional and Structural Synergy for Resolution Recovery and Partial Volume Correction in Brain PET. NeuroImage 2009, 44, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohka, J.; Reilhac, A. Deconvolution-Based Partial Volume Correction in Raclopride-PET and Monte Carlo Comparison to MR-Based Method. NeuroImage 2008, 39, 1570–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golla, S.S.V.; Lubberink, M.; van Berckel, B.N.M.; Lammertsma, A.A.; Boellaard, R. Partial Volume Correction of Brain PET Studies Using Iterative Deconvolution in Combination with HYPR Denoising. EJNMMI Research 2017, 7, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, K.; Ibaraki, M.; Kinoshita, T. ; for the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative DeepPVC: Prediction of a Partial Volume-Corrected Map for Brain Positron Emission Tomography Studies via a Deep Convolutional Neural Network. EJNMMI Physics 2022, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, M.-S.; Kamali-Asl, A.; Ay, M.-R.; Zeraatkar, N.; Hosseini, M.-S.; Sanaat, A.; Dadgar, H.; Arabi, H. Deep Learning-Based Partial Volume Correction in Standard and Low-Dose Positron Emission Tomography-Computed Tomography Imaging. Quant Imaging Med Surg 2024, 14, 2146–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, B.B.; Raue, F.; Frolov, S.; Palacio, S.; Hees, J.; Dengel, A. Hitchhiker’s Guide to Super-Resolution: Introduction and Recent Advances. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2023, 45, 9862–9882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Ali, H.; Shah, Z.; Azmat, S. A New Generative Adversarial Network for Medical Images Super Resolution. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 9533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Van Gool, L. Is Image Super-Resolution Helpful for Other Vision Tasks? In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV); March 2016; pp. 1–9.

- Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Chang, M.; Chen, S.; Feng, H.; Xu, Z.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y. SRDiff: Single Image Super-Resolution with Diffusion Probabilistic Models. Neurocomputing 2022, 479, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haris, M.; Shakhnarovich, G.; Ukita, N. Task-Driven Super Resolution: Object Detection in Low-Resolution Images. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing; Mantoro, T., Lee, M., Ayu, M.A., Wong, K.W., Hidayanto, A.N., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; pp. 387–395. [Google Scholar]

- Rasti, P.; Uiboupin, T.; Escalera, S.; Anbarjafari, G. Convolutional Neural Network Super Resolution for Face Recognition in Surveillance Monitoring. In Proceedings of the Articulated Motion and Deformable Objects; Perales, F.J., Kittler, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016; pp. 175–184. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Sixou, B.; Peyrin, F. A Review of the Deep Learning Methods for Medical Images Super Resolution Problems. IRBM 2021, 42, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenspan, H. Super-Resolution in Medical Imaging. The Computer Journal 2009, 52, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, J.S.; Kulkarni, R. Super Resolution Techniques for Medical Image Processing. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Technologies for Sustainable Development (ICTSD); February 2015; pp. 1–6.

- Sun, J.; Xu, Z.; Shum, H.-Y. Image Super-Resolution Using Gradient Profile Prior. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; June 2008; pp. 1–8.

- Chang, H.; Yeung, D.-Y.; Xiong, Y. Super-Resolution through Neighbor Embedding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2004. CVPR 2004.; June 2004; Vol. 1, p. I–I.

- Image Super-Resolution Via Sparse Representation | IEEE Journals & Magazine | IEEE Xplore. Available online: https://ieeexplore-ieee-org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/abstract/document/5466111 (accessed on 11 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Hoi, S.C.H. Deep Learning for Image Super-Resolution: A Survey 2020. [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Pouget-Abadie, J.; Mirza, M.; Xu, B.; Warde-Farley, D.; Ozair, S.; Courville, A.; Bengio, Y. Generative Adversarial Networks. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1406.2661v1 (accessed on 11 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Rezende, D.; Mohamed, S. Variational Inference with Normalizing Flows. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning; PMLR, June 1 2015; pp. 1530–1538.

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.11239v2 (accessed on 11 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Rodriguez-Andina, J.J.; Luo, H.; Yin, S.; Kaynak, O. When Medical Images Meet Generative Adversarial Network: Recent Development and Research Opportunities. Discov Artif Intell 2021, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, Y. Diffusion Normalizing Flow. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Curran Associates, Inc., 2021; Vol. 34, pp. 16280–16291. [Google Scholar]

- Khader, F.; Müller-Franzes, G.; Tayebi Arasteh, S.; Han, T.; Haarburger, C.; Schulze-Hagen, M.; Schad, P.; Engelhardt, S.; Baeßler, B.; Foersch, S.; et al. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models for 3D Medical Image Generation. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 7303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Franzes, G.; Niehues, J.M.; Khader, F.; Arasteh, S.T.; Haarburger, C.; Kuhl, C.; Wang, T.; Han, T.; Nolte, T.; Nebelung, S.; et al. A Multimodal Comparison of Latent Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models and Generative Adversarial Networks for Medical Image Synthesis. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 12098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinaya, W.H.L.; Tudosiu, P.-D.; Dafflon, J.; Da Costa, P.F.; Fernandez, V.; Nachev, P.; Ourselin, S.; Cardoso, M.J. Brain Imaging Generation with Latent Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the Deep Generative Models; Mukhopadhyay, A., Oksuz, I., Engelhardt, S., Zhu, D., Yuan, Y., Eds.; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2022; pp. 117–126. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, S.; Dall’Olio, D.; Sala, C.; Dall’Olio, L.; Sauta, E.; Zampini, M.; Asti, G.; Lanino, L.; Maggioni, G.; Campagna, A.; et al. Synthetic Data Generation by Artificial Intelligence to Accelerate Research and Precision Medicine in Hematology. JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajotte, J.-F.; Bergen, R.; Buckeridge, D.L.; Emam, K.E.; Ng, R.; Strome, E. Synthetic Data as an Enabler for Machine Learning Applications in Medicine. iScience 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thambawita, V.; Salehi, P.; Sheshkal, S.A.; Hicks, S.A.; Hammer, H.L.; Parasa, S.; Lange, T. de; Halvorsen, P.; Riegler, M.A. SinGAN-Seg: Synthetic Training Data Generation for Medical Image Segmentation. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0267976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Killeen, B.D.; Hu, Y.; Grupp, R.B.; Taylor, R.H.; Armand, M.; Unberath, M. Synthetic Data Accelerates the Development of Generalizable Learning-Based Algorithms for X-Ray Image Analysis. Nat Mach Intell 2023, 5, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lei, J.; Sun, D.; Xu, F.; Xu, X. Anomaly Segmentation in Retinal Images with Poisson-Blending Data Augmentation. Medical Image Analysis 2022, 81, 102534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyu, F.; Ye, M.; Carlsen, J.F.; Erleben, K.; Darkner, S.; Yuen, P.C. Pseudo-Label Guided Image Synthesis for Semi-Supervised COVID-19 Pneumonia Infection Segmentation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2023, 42, 797–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, C.J.; Carrillo, M.C.; Jagust, W.; Jack, C.R.; Shaw, L.M.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Saykin, A.J.; Beckett, L.A.; Sur, C.; Rao, N.P.; et al. The Worldwide Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: ADNI-3 Updates and Global Perspectives. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2021, 7, e12226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OASIS-3: Longitudinal Neuroimaging, Clinical, and Cognitive Dataset for Normal Aging and Alzheimer Disease | medRxiv. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2019.12.13.19014902v1 (accessed on 19 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Standardization of Amyloid Quantitation with Florbetapir Standardized Uptake Value Ratios to the Centiloid Scale - Navitsky - 2018 - Alzheimer’s & Dementia - Wiley Online Library. Available online: https://alz-journals-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/doi/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.06.1353 (accessed on 24 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Blazey, T.M.; Snyder, A.Z.; Raichle, M.E.; Marcus, D.S.; Ances, B.M.; Bateman, R.J.; Cairns, N.J.; Aldea, P.; Cash, L.; et al. Partial Volume Correction in Quantitative Amyloid Imaging. NeuroImage 2015, 107, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. NeuroImage 2012, 62, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; D’Angelo, G.M.; Vlassenko, A.G.; Zhou, G.; Snyder, A.Z.; Marcus, D.S.; Blazey, T.M.; Christensen, J.J.; Vora, S.; Morris, J.C.; et al. Quantitative Analysis of PiB-PET with FreeSurfer ROIs. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e73377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucy, L.B. An Iterative Technique for the Rectification of Observed Distributions. The Astronomical Journal 1974, 79, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, D.S.C.; Andrews, M. Acceleration of Iterative Image Restoration Algorithms. Appl. Opt., AO 1997, 36, 1766–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saharia, C.; Chan, W.; Saxena, S.; Li, L.; Whang, J.; Denton, E.; Ghasemipour, S.K.S.; Ayan, B.K.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Gontijo-Lopes, R.; et al. Photorealistic Text-to-Image Diffusion Models with Deep Language Understanding.

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis With Latent Diffusion Models.; 2022; pp. 10684–10695.

- Loss Functions for Image Restoration With Neural Networks | IEEE Journals & Magazine | IEEE Xplore. Available online: https://ieeexplore-ieee-org.ezproxy1.lib.asu.edu/document/7797130 (accessed on 14 September 2024). [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regularization and Variable Selection Via the Elastic Net. [CrossRef]

- López-González, F.J.; Silva-Rodríguez, J.; Paredes-Pacheco, J.; Niñerola-Baizán, A.; Efthimiou, N.; Martín-Martín, C.; Moscoso, A.; Ruibal, Á.; Roé-Vellvé, N.; Aguiar, P. Intensity Normalization Methods in Brain FDG-PET Quantification. NeuroImage 2020, 222, 117229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Meng, C.; Ermon, S. DENOISING DIFFUSION IMPLICIT MODELS. 2021.

- Jennewein, D.M.; Lee, J.; Kurtz, C.; Dizon, W.; Shaeffer, I.; Chapman, A.; Chiquete, A.; Burks, J.; Carlson, A.; Mason, N.; et al. The Sol Supercomputer at Arizona State University. In Proceedings of the Practice and Experience in Advanced Research Computing 2023: Computing for the Common Good; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, September 10 2023; pp. 296–301.

| Cohort | ADNI | OASIS-3 | Centiloid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample count | 334 (167 baseline-followup FBPs) |

113 (FBP-PIB pairs) |

46 (FBP-PIB pairs) |

|

Age (SD) years |

75.1 (6.9) | 68.1 (8.7) | 58.4 (21.0) |

|

Education (SD) years |

16.1 (2.7) | 15.8 (2.6) | NA |

| Male (%) | 182 (54.5%) | 48 (42.5%) | 27 (58.7%) |

|

Cognitive impairment (%) |

236 (70.6%) | 5 (4.4%) | 24 (52.2%) |

| APOE4+ (%) | 218 (65.3%) | 38 (33.6%) | 15 (46.9*%) [*14 out of 46 unknown] |

|

PET interval (SD) years |

2.0 (0.06) | NA | NA |

| Annualized rate | Raw | RL-RR | LDM-RR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.0278 | 0.0377 | 0.0459 |

| SD | 0.0664 | 0.0807 | 0.0881 |

| p-value | 1.0E-07 | 5.0E-09 | 1.3E-10 |

| SS | 1431 | 1154 | 926 |

| Method | Pearson Correlation |

Steiger’s p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Without correction | 0.9163 | N/A |

| RL-RR | 0.9308 | <0.0001 (RL-RR vs. without correction) |

| LDM-RR | 0.9411 | 0.0001 (LDM-RR vs. without correction) |

| 0.0421 (LDM-RR vs. RL-RR) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).