INTRODUCTION

Probiotic are live microorganisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host. The particular health benefits of probiotics include helping reduce the incidence of conditions such as antibiotic-associated diarrhea, digestive discomfort (including in irritable bowel syndrome), colic symptoms in breastfed babies, atopic issues such as eczema in infants, symptoms of lactose maldigestion, acute pediatric infectious diarrhea, upper respiratory tract infections (such as the common cold), and gut infections [

1,

2].

Nonetheless, there are investigators and organizations that remain skeptical about the benefits of probiotics. For example, the American Gastroenterological Association does not recommend the use of probiotics for most digestive conditions [

3]. Some critics argue that the scientific evidence supporting probiotic benefits is not sufficiently robust, citing that many studies are small, short-term, or yield conflicting results. Additionally, probiotics vary in dosage and bacterial strains, and not all strains have the same effects.

Probiotic dietary supplements are typically consumed as dry powder encapsulated in capsules, and to a lesser extent in the form of tablets or gummies. Once the gelatin capsule or gummy is digested by stomach pepsin, the dry powder probiotics are exposed to stomach acid (HCl at a pH of ~1.5). Existing literature from clinical trials demonstrates either the ineffectiveness or limited effectiveness of various dry powder probiotics following ingestion.

Prantera et al. (2002), in a randomized controlled trial, reported ineffectiveness of probiotics (

Lactobacillus GG) in preventing recurrence after curative resection for Crohn's disease [

4].

Mastretta et al. (2002) found that

Lactobacillus GG was ineffective in preventing nosocomial rotavirus infections, whereas breast-feeding was effective [

5].

Kuisma et al. (2003) reported that a single-strain probiotic bacterium supplement of

Lactobacillus GG changed the ileal pouch intestinal bacterial flora, but did not evoke a clinical or endoscopic response and hence was ineffective as a primary therapy [

6].

Banaszkiewics and Szajewska (2005), in a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial, found

Lactobacillus GG used as an adjunct to lactulose to be ineffective for the treatment of constipation in children [

7].

Marteau et al. (2006), in a double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial, determined that

Lactobacillus johnsonii LA1 is ineffective for prophylaxis of postoperative recurrence in Crohn's disease [

8].

Hegar et al. (2015) conducted a double-blind randomized trial in Indonesian children and showed probiotics to be ineffective in acute diarrhea [

9].

Little et al. (2017) found in a randomized controlled factorial trial that neither probiotics nor advice to chew xylitol-based chewing gum was effective for managing pharyngitis [

10].

There is also abundant evidence indicating that the survivability of probiotics in the harsh acidic environment of the stomach is a critical determinant of their effectiveness.

Tompkins et al. (2011) studied meal impact on a probiotic during transit through a model of the human upper gastrointestinal tract and showed that bacterial survival was best when given either with a meal or 30 minutes before a meal [

11].

Fredua-Agyeman and Gaisford (2015) explored the survival of commercial probiotic formulations in biorelevant gastric fluids, conducting real-time measurements using microcalorimetry. They found that, in general, liquid-based products tended to give superior survival results compared with freeze-dried products [

12].

Corcoran et al. (2005) analyzed the effect of glucose on

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG survival after 90 minutes in simulated gastric juice at pH 2.They found that glucose concentrations from 1 to 19.4 mM enhanced bacterial survival, achieving final bacterial concentrations from 6.4 to 8 log

10 CFU ml

-Subsequent experiments with dilute HCl confirmed that glucose was the sole component responsible, with survival in acidic conditions occurring only in the presence of sugars that the bacteria could metabolize efficiently. Specifically, they determined that provision of ATP to F

0F

1-ATPase via glycolysis enables proton exclusion and thereby enhances survival during gastric transit [

13].

In current practice, dry powder probiotics are protected from direct exposure to stomach acid by means of acid-resistant, delayed-release enteric-coated capsules, which help ensure that the probiotics reach the less harsh environment of the small intestine and therefore realize optimal effectiveness. However, these enteric-coated capsules are often more expensive than regular capsules because the coating process incurs additional cost.

We hypothesized that pre-hydrating dry powder probiotics in a fruit and vegetable juice carrier would enhance their resistance to stomach acid on account of the combined effects of cellular hydration, buffering properties and sugar content of the juice.

The aim of this in vitro study was to determine whether a pre-hydrated Doctor's Biome Signature Probiotic Blend (DBSPB) in a fruit and vegetable juice carrier can better survive the stomach's acidic environment (HCl at pH 1.5) compared to the same probiotic blend in its dry powdered form.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Doctor's Biome Signature Probiotic Blend (DBSPB):

Bacteria of the genera

Bifidobacterium and

Lactobacillus are broadly recognized for their key roles in the human intestinal microflora. We designed a proprietary blend of five strains of

Bifidobacterium and ten strains of

Lactobacillus obtained from the reputable company Cultures Supporting Life (

Table 1). Species identification of these probiotics has been performed by sequence analysis of the 16S rRNA gene, and strain identification by pulse field gel electrophoresis. These probiotics have been shown to be sensitive to antibiotics and have passed microbiological assays and heavy metal analyses. They are not genetically modified, are free from allergens, are considered safe with respect to bovine spongiform encephalopathy, and do not contain colorants.

Organic Green Juice (OGJ):

As an optimum liquid carrier, we chose a proprietary sterilized blend of 100% organic green fruit and vegetable juices, specifically mint, cucumber, apple, lettuce, kale, celery and lemon juice (pH 4.0).

Study Design:

Table 2 summarizes the evaluations used in this study and associated sample counts.

- 1)

-

Evaluation of the PRE-HYDRATED probiotic blend

Testing performed at room temperature

0.154 g probiotic blend added to 59 ml OGJ, mixed for 1 min

Stored for 0 min, 30 min, and 60 min at room temperature

- 2)

-

Evaluation of the DRY probiotic blend

Testing performed in a 37 °C water bath

0.154 g probiotic blend added to 59 ml HCl at pH 1.5, mixed for 1 min

Stored for 0 min, 30 min, and 60 min in a 37 °C water bath

- 3)

-

Evaluation of the COMBINED pre-hydrated probiotic blend (in juice) & the dry probiotic blend

Pre-hydrated probiotics in OGJ and dry probiotics in HCl prepared as above

Combined OGJ preparation with HCl preparation in the 37 °C water bath

Stored for 0 min, 30 min, and 60 min at 37 °C

Probiotic Enumeration (Three Replicates)

Probiotic enumeration was performed following published reference methods [

14,

15]. This evaluation was performed three times.

Baseline Evaluation

The pH of the Organic Green Juice (three separate aliquots) was assessed (AOAC 981.12) at baseline, and that of the HCl throughout the titration to achieve a final working solution with pH 1.5.

RESULTS

Visual Observation:

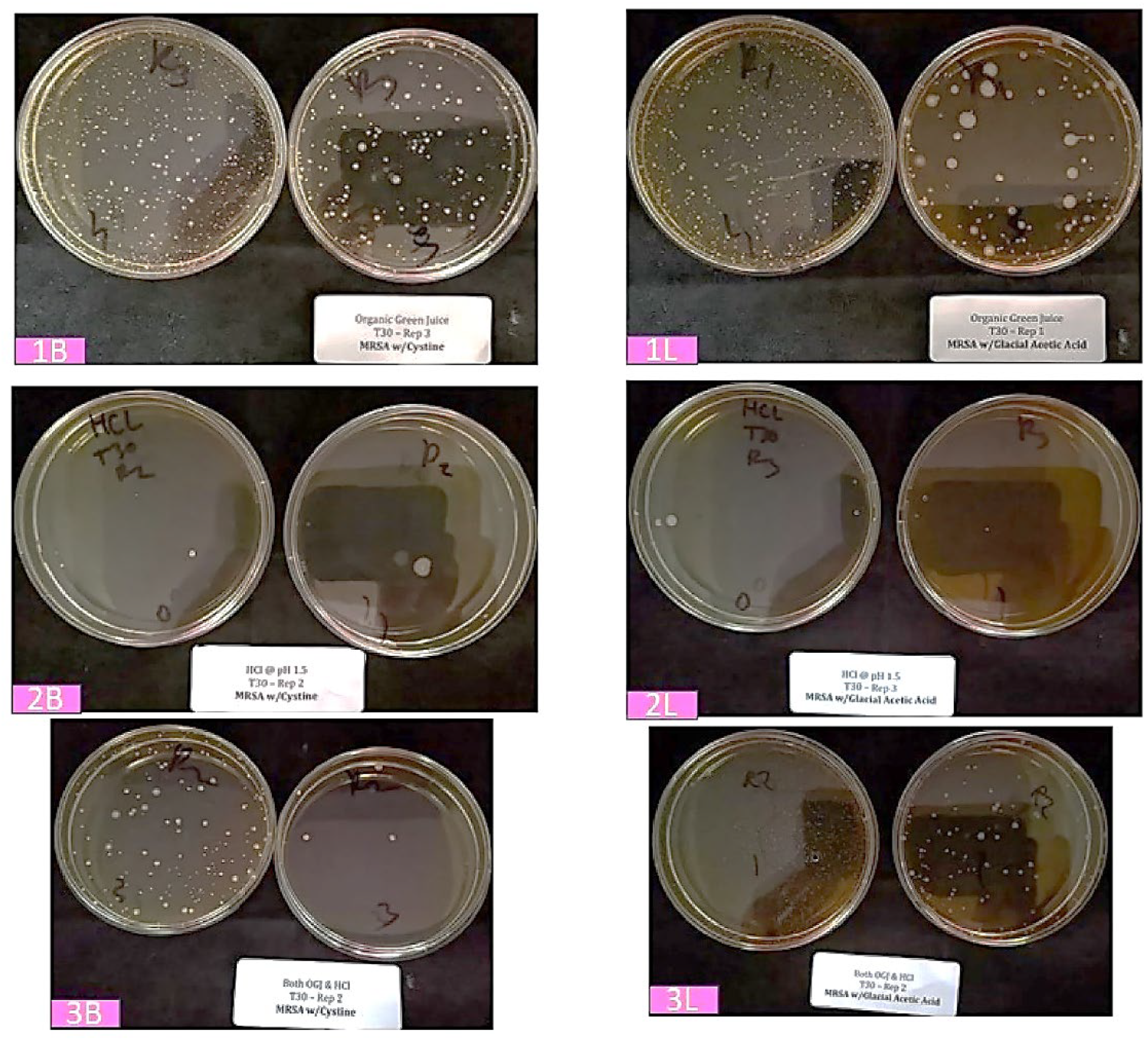

As can be observed in the representative images of enumeration plates (

Figure 1, 30 minutes storage at 37 °C), when mixed in OGJ (“baseline”), colonies of the probiotic

Bifidobacteria (1B) and lactic acid bacteria (1L) happily survive and grow. However, when the corresponding dry powder formulations (2B and 2L) are mixed with HCl solution (pH 1.5), the bacteria do not survive to form colonies. Interestingly, when the probiotic bacteria pre-hydrated in OGJ are combined with the HCl solution (3B and 3L), a substantial number survive to form colonies—far more than with direct mixing of the dry powder probiotic and HCl solution.

Enumerative Observation:

Table 3 presents the enumerations of probiotic

Bifidobacteria, lactic acid bacteria, and their total in OGJ, HCl @ pH 1.5, and the combined treatment.

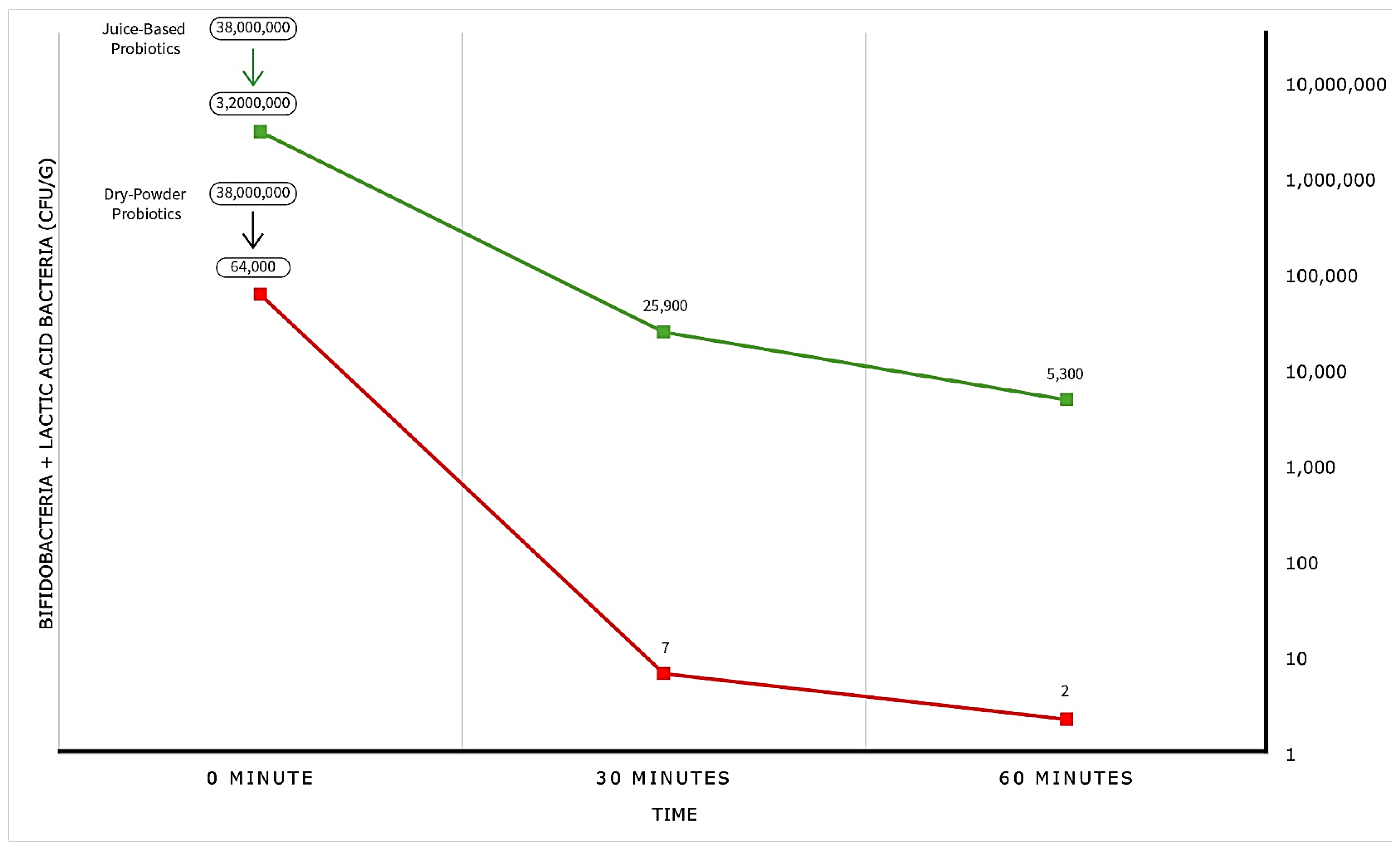

For probiotics hydrated in OGJ, both individual and total bacterial numbers were high and relatively constant (36 million CFU/g to 28 million CFU/g) for up to 60 minutes. Let’s consider this 36 million CFU/g as the baseline.

For the dry powder formulation, the total bacterial number was reduced to 64,000 CFU/g upon mixing with HCl (pH 1.5), declined further to 7 CFU/g after 30 minutes, and reached a low of 2 CFU/g after 60 minutes. For practical purposes, the bacteria were eliminated.

In contrast, when pre-hydrated probiotics were mixed with HCl (pH 1.5), the baseline abundance was immediately reduced to 3.2 million CFU/g, then to 25,900 CFU/g after 30 minutes, and finally to 5,100 CFU/g after 60 minutes. This represents impressive resistance to elimination.

Graphical Observation:

Figure 2 presents the enumeration data in graphical form, vividly that illustrating the greatly superior survival of probiotics exposed to stomach acid (HCl, pH 1.5) when delivered in a juice carrier rather than as a dry powder.

DISCUSSION

From the averages of our enumerative observations, we can calculate the "Survival Ratio" at each timepoint of CFUs in HCl for OGJ pre-hydrated DBSPB and for dry DBSPB.

Table 4 presents these values. In short, the pre-hydrated probiotics survived stomach acidity 50 times better at time zero, 3,700 times better after 30 minutes, and 2,188 times better after 60 minutes.

These results confirm our hypothesis that incorporating dry powder probiotics like DBSPB into a fruit and vegetable juice carrier enhances their resistance and survivability when exposed to stomach acid.

We believe this enhanced survivability is due to the combined effects of hydrating the probiotic cells, the buffering capacity of the juices, and the presence of glucose in the juices. In dry powder form, probiotic cells quickly absorb proton ions from HCl, leading to their inactivation, whereas in pre-hydrated form, the cells absorb proton ions more gradually. Additionally, the juices provide buffering capacity, meaning the solution can resist pH changes when acids or bases are introduced. Finally, glucose metabolism has been shown to improve probiotic survival during exposure to gastric acid.

In light of the above, it is appropriate to designate a blend of optimal probiotics (such as DBSPB) delivered in fruit and vegetable juices as a "Next Generation Probiotic."

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the valuable contributions of Wendy Reid (Senior Research Operations Manager) and Ben Howard (Laboratory Director) from the accredited Certified Laboratories (

www.certified-laboratories.com) in performing this study.

Author Contributions

ARK proposed, designed and oversaw this study and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. HFR had observed the efficacy of juice-based probiotics in his patients, and reviewed the draft of the manuscript. EF assisted in the preparation of the samples, contractual arrangements with Certified Laboratories, conversion of tabulated values to graphs, and reviewed the draft of the manuscript.

Funding

Dr. Robins: Dr. Kamarei, and Mr. Finkelstein are partners in Doctor’s Biome Company (Newgen 27 LLC). Dr. Kamarei was paid for consulting services, and Certified Laboratories were paid for performing the study.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset (final report from Certified Laboratories) used and/or analyzed during the current study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

There is no competing interest in this study.

References

- ISAPP - International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics. International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) https://isappscience.org/.

- International Probiotics Association. International Probiotics Association – The Global Voice of Probiotics. Internationalprobiotics.org https://internationalprobiotics.org/home/ (2022).

- Su, G.L.; et al. AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Role of Probiotics in the Management of Gastrointestinal Disorders. Gastroenterology 2020, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prantera, C. Ineffectiveness of probiotics in preventing recurrence after curative resection for Crohn’s disease: a randomised controlled trial with Lactobacillus GG. Gut 2002, 51, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastretta et al. Effect of Lactobacillus GG and Breast-Feeding in the Prevention of Rotavirus Nosocomial Infection. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12394379/ (2002).

- Kuisma, J.; et al. Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG on ileal pouch inflammation and microbial flora. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2003, 17, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszkiewicz, A.; Szajewska, H. Ineffectiveness of Lactobacillus GG as an adjunct to lactulose for the treatment of constipation in children: A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. The Journal of Pediatrics 2005, 146, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marteau, P. Ineffectiveness of Lactobacillus johnsonii LA1 for prophylaxis of postoperative recurrence in Crohn’s disease: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled GETAID trial. Gut 2006, 55, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegar, B.; Waspada, I.M.I.; Gunardi, H.; Vandenplas, Y. A Double-Blind Randomized Trial Showing Probiotics to be Ineffective in Acute Diarrhea in Indonesian Children. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics 2014, 82, 410–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, P.; et al. Probiotic capsules and xylitol chewing gum to manage symptoms of pharyngitis: a randomized controlled factorial trial. Canadian Medical Association Journal 2017, 189, E1543–E1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tompkins, T.; Mainville, I.; Arcand, Y. The impact of meals on a probiotic during transit through a model of the human upper gastrointestinal tract. Beneficial Microbes 2011, 2, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredua-Agyeman, M.; Gaisford, S. Comparative Survival of Commercial Probiotic formulations: Tests in Biorelevant Gastric Fluids and real-time Measurements Using Microcalorimetry. Beneficial Microbes 2015, 6, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corcoran, B.M.; Stanton, C.; Fitzgerlad, G.F.; Ross, R.P. Survival of Probiotic Lactobacilli in Acidic Environments Is Enhanced in the Presence of Metabolizable Sugars. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005, 71, 3060–3067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lactic Acid Bacteria enumeration, APHA Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Food, Chapter 19.

-

Bifidobacteria enumeration, APHA Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Food, Chapter 20.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).