Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

04 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Double Caregiving and Work–Life Balance in Healthcare

1.2. Burnout and Double Caregiving

1.3. Job Satisfaction in Healthcare Professionals

1.4. Study Aim

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Assessment Instruments

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Issues

3. Results

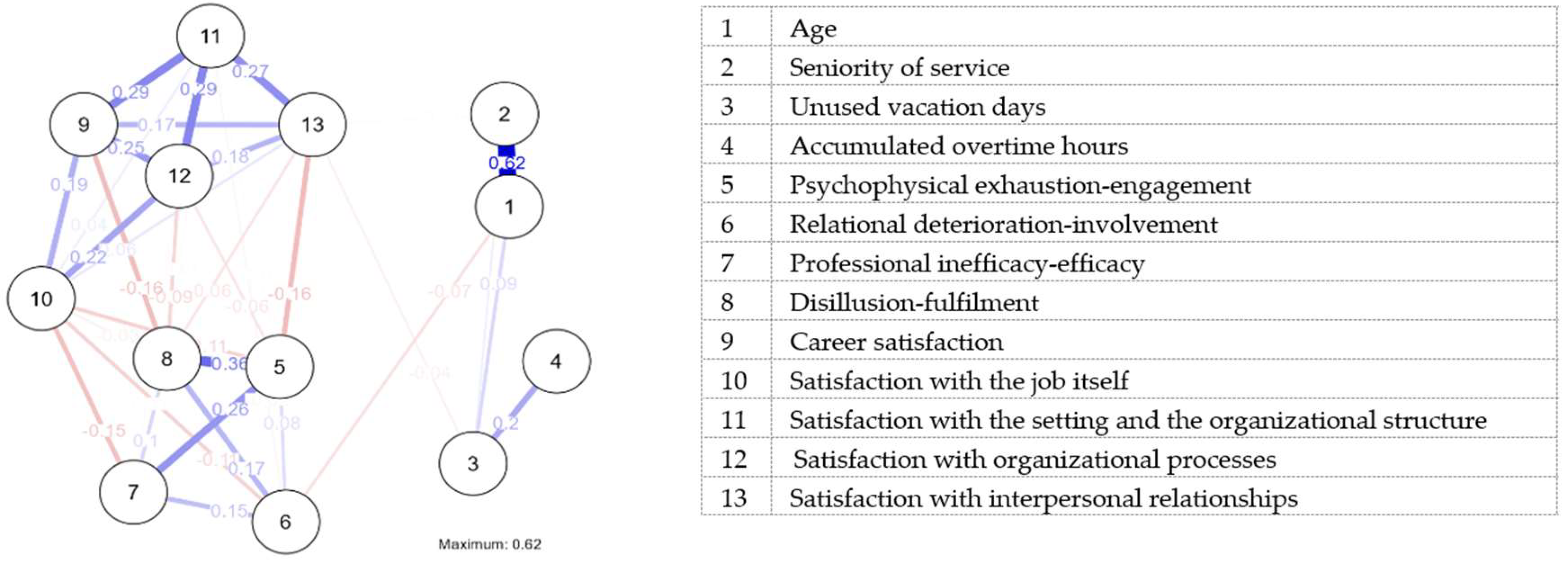

3.1. Results of the Overall Sample

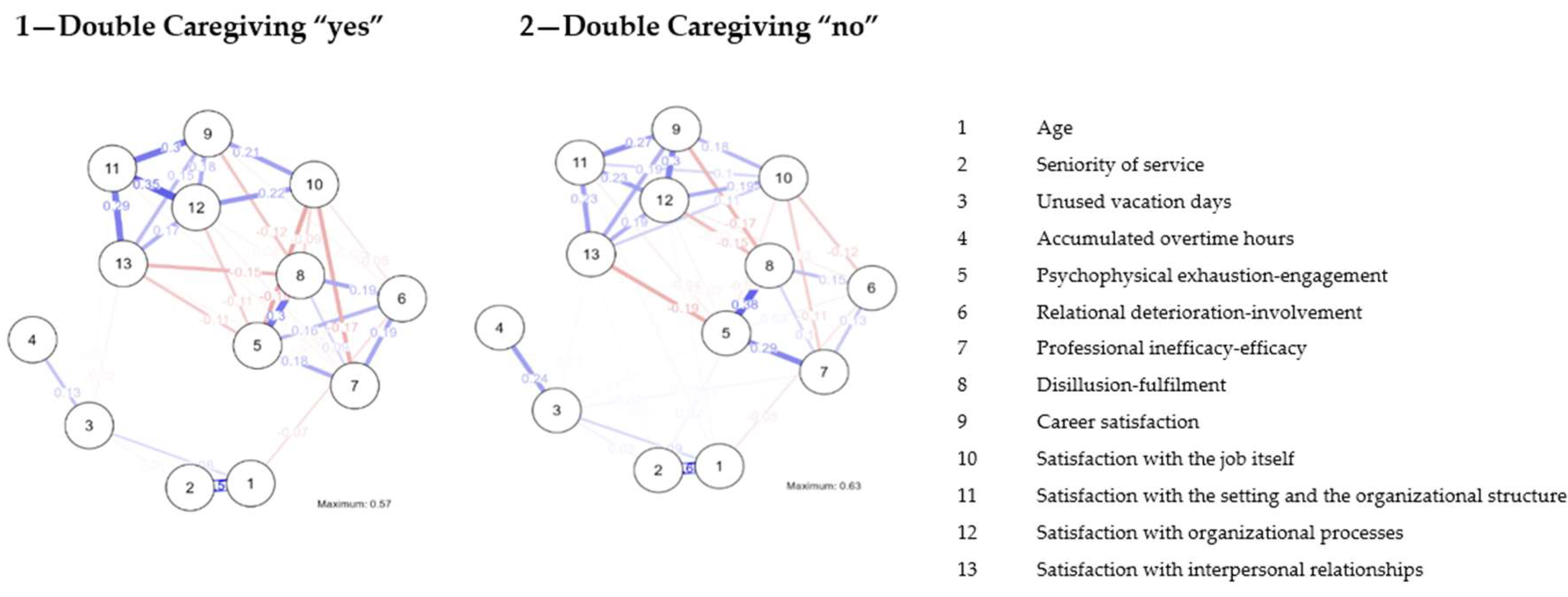

3.2 Results of the Subsample Comparison

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Sample

4.2. Comparison of Subsamples

4.3. Practical Implications

4.4. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boumans, N.P.G.; Dorant, E. Double-duty Caregivers: Healthcare Professionals Juggling Employment and Informal Caregiving. A Survey on Personal Health and Work Experiences. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 1604–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Detaille, S.I.; De Lange, A.; Engels, J.; Pijnappels, M.; Hutting, N.; Osagie, E.; Reig-Botella, A. Supporting Double Duty Caregiving and Good Employment Practices in Health Care Within an Aging Society. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 535353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häusler, N.; Bopp, M.; Hämmig, O. Informal Caregiving, Work-Privacy Conflict and Burnout among Health Professionals in Switzerland—A Cross-Sectional Study. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gérain, P.; Zech, E. Informal Caregiver Burnout? Development of a Theoretical Framework to Understand the Impact of Caregiving. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, K.; Eggett, D.; Patten, E.V. How Work and Family Caregiving Responsibilities Interplay and Affect Registered Dietitian Nutritionists and Their Work: A National Survey. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gérain, P.; Zech, E. Do Informal Caregivers Experience More Burnout? A Meta-Analytic Study. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2021, 26, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boy, Y.; Sürmeli, M. Quiet quitting: A significant risk for global healthcare. Journal of Global Health 2023, 13, 03014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DePasquale, N.; Davis, K.D.; Zarit, S.H.; Moen, P.; Hammer, L.B.; Almeida, D.M. Combining Formal and Informal Caregiving Roles: The Psychosocial Implications of Double- and Triple-Duty Care. GERONB 2016, 71, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S.P.; Adair, K.C.; Bae, J.; Rehder, K.J.; Shanafelt, T.D.; Profit, J.; Sexton, J.B. Work-Life Balance Behaviours Cluster in Work Settings and Relate to Burnout and Safety Culture: A Cross-sectional Survey Analysis. BMJ Quality & Safety 2019, 28(2), 142–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; Hasan, O.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Sinsky, C.; Satele, D.; Sloan, J.; West, C.P. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2015, 90, 1600–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanafelt, T.D.; West, C.P.; Sinsky, C.; Trockel, M.; Tutty, M.; Wang, H.; Carlasare, L.E.; Dyrbye, L.N. Changes in Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Integration in Physicians and the General US Working Population Between 2011 and 2020. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2022, 97, 491–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodendieck, E.; Jung, F.U.; Conrad, I.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Hussenoeder, F.S. The Work-Life Balance of General Practitioners as a Predictor of Burnout and Motivation to Stay in the Profession. BMC Prim. Care 2022, 23, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volk, J.O.; Schimmack, U.; Strand, E.B.; Reinhard, A.; Hahn, J.; Andrews, J.; Probyn-Smith, K.; Jones, R. Work-Life Balance Is Essential to Reducing Burnout, Improving Well-Being. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2024, 262, 950–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, J.; L’Heureux, T.; Lobchuk, M.; Penner, J.; Charles, L.; St. Amant, O.; Ward-Griffin, C.; Anderson, S. Double-Duty Caregivers Enduring COVID-19 Pandemic to Endemic: “It’s Just Wearing Me down”. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, X.W.; Shang, S.; Brough, P.; Wilkinson, A.; Lu, C. Work, Life and COVID -19: A Rapid Review and Practical Recommendations for the post-pandemic Workplace. Asia Pac J Human Res 2023, 61, 257–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayar, D.; Karaman, M.A.; Karaman, R. Work-Life Balance and Mental Health Needs of Health Professionals During COVID-19 Pandemic in Turkey. Int J Ment Health Addiction 2022, 20, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfouz, M.S.; Osman, S.A.; Mohamed, B.A.; Saeed, E.A.M.; Ismaeil, M.I.H.; Elkhider, R.A.A.; Orsud, M.A. Healthcare Professionals’ Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Sudan: A Cross-Sectional Survey Assessing Quality of Life, Mental Health, and Work-Life-Balance. Int J Public Health 2023, 68, 1605991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thro, P.D.; Prasain, G.P. Work-Life Balance—Its Impact on Job Satisfaction among the Healthcare Workers in Senapati District, Manipur. SDMIMD 2024, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Keshky, M.E.S.; Sarour, E.O. The Relationships between Work-Family Conflict and Life Satisfaction and Happiness among Nurses: A Moderated Mediation Model of Gratitude and Self-Compassion. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1340074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pien, L.-C.; Cheng, W.-J.; Chou, K.-R.; Lin, L.-C. Effect of Work–Family Conflict, Psychological Job Demand, and Job Control on the Health Status of Nurses. IJERPH 2021, 18, 3540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, L.G.; Sharma, J.; Walia, H.S. Improving Work–Life Balance and Satisfaction to Improve Patient Care. Indian J Crit Care Med 2024, 28, 326–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B. Job Demands-Resources Theory in Times of Crises: New Propositions. Organizational Psychology Review 2023, 13, 209–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslach, C.; Leiter, M.P.; Schaufeli, W.B. Measuring burnout. In The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Well-Being; Cooper, C.L., Cartwright, S., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 86–108. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout: A short socio-cultural history. In Burnout, Fatigue, Exhaustion; Neckel, S., Schaffner, A., Wagner, G., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2017a; pp. 105–127. [Google Scholar]

- Nadon, L.; De Beer, L.T.; Morin, A.J.S. Should Burnout Be Conceptualized as a Mental Disorder? Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B. Burnout: A Critical Overview. In Organizational Stress and Well-Being; Lapierre, L.M., Cooper, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2023; pp. 214–259. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B. Applying the Job Demands-Resources Model. Organ. Dyn. 2017b, 46, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Taris, T.W. How Are Changes in Exposure to Job Demands and Job Resources Related to Burnout and Engagement? A Longitudinal Study among Chinese Nurses and Police Officers. Stress and Health 2017, 33, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rattrie, L.T.B.; Kittler, M.G.; Paul, K.I. Culture, Burnout, and Engagement: A Meta-Analysis on National Cultural Values as Moderators in JD-R Theory. Applied Psychology 2020, 69, 176–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B. Work Engagement. What Do We Know and Where Do We Go? Rom. J. Appl. Psychol. 2012, 14, 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Defining and measuring work engagement: Bringing clarity to the concept. In Work Engagement: A Handbook of Essential Theory and Research; Bakker, A.B., Leiter, M.P., Eds.; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2010; pp. 10–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Ropponen, A.; Schaufeli, W.B.; De Witte, H. Who Is Engaged at Work?: A Large-Scale Study in 30 European Countries. J Occup Environ Med 2019, 61, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Van Rhenen, W. How Changes in Job Demands and Resources Predict Burnout, Work Engagement, and Sickness Absenteeism. J Organ Behavior 2009, 30, 893–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B. Do Burnout and Work Engagement Predict Depressive Symptoms and Life Satisfaction? A Three-Wave Seven-Year Prospective Study. J Affec Disord 2012, 141, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nonnis, M.; Pirrone, M.P.; Cuccu, S.; Agus, M.; Pedditzi, M.L.; Cortese, C.G. Burnout Syndrome in Reception Systems for Illegal Immigrants in the Mediterranean. A Quantitative and Qualitative Study of Italian Practitioners. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Work Engagement: A Critical Assessment of the Concept and Its Measurement. In Handbook of Positive Psychology Assessment; Tuch, W.R., Bakker, A.B., Tay, L., Gander, F., Eds.; Hogrefe: Göttingen, Germany, 2022; pp. 273–295. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/129180281 (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Santinello, M.; Negrisolo, A. Quando Ogni Passione è Spenta. La Sindrome del Burnout nelle Professioni Sanitarie; Mc Graw Hill: Milan, Italy, 2009; pp. 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Borgogni, L.; Consiglio, C.; Alessandri, G.; Schaufeli, W.B. “Don’t Throw the Baby out with the Bathwater!” Interpersonal Strain at Work and Burnout. Eur J Work Organ Psychol 2012, 21, 875–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelwich, J.; Brodsky, A. Burnout: Stages of Disillusionment in the Helping Professions; Kluwer Academic Plenum Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1980; pp. 7–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tanios, M.; Haberman, D.; Bouchard, J.; Motherwell, M.; Patel, J. Analyses of Burn-out among Medical Professionals and Suggested Solutions—A Narrative Review. J Hosp Manag Health Policy 2022, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, S.; Han, D.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liao, H.; Ma, Y.; Yan, C.; Wang, J. Association of Job Characteristics and Burnout of Healthcare Workers in Different Positions in Rural China: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Public Health 2023, 68, 1605966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izdebski, Z.; Kozakiewicz, A.; Białorudzki, M.; Dec-Pietrowska, J.; Mazur, J. Occupational Burnout in Healthcare Workers, Stress and Other Symptoms of Work Overload during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. IJERPH 2023, 20, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrowes, S.A.B.; Casey, S.M.; Pierre-Joseph, N.; Talbot, S.G.; Hall, T.; Christian-Brathwaite, N.; Del-Carmen, M.; Garofalo, C.; Lundberg, B.; Mehta, P.K.; et al. COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts on Mental Health, Burnout, and Longevity in the Workplace among Healthcare Workers: A Mixed Methods Study. J Interprof Educ Pract 2023, 32, 100661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antao, H.S.; Sacadura-Leite, E.; Correia, A.I.; Figueira, M.L. Burnout in Hospital Healthcare Workers after the Second COVID-19 Wave: Job Tenure as a Potential Protective Factor. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 942727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, P.E. Job Satisfaction: Application, Assessment, Causes, and Consequences; SAGE Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Caraballo-Arias, Y.; Feola, D.; Milani, S. The Science of Joy: Happiness among Healthcare Workers. Curr Opin Epidemiol Public Health 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negri, L.; Cilia, S.; Falautano, M.; Grobberio, M.; Niccolai, C.; Pattini, M.; Pietrolongo, E.; Quartuccio, M.E.; Viterbo, R.G.; Allegri, B.; et al. Job Satisfaction among Physicians and Nurses Involved in the Management of Multiple Sclerosis: The Role of Happiness and Meaning at Work. Neurol Sci 2022, 43, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, S.; Vargas, M.; Servillo, G. Organizational Strategies to Reduce Physician Burnout: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021, 33, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Misra, R.; Madan, P. ‘The Saviors Are Also Humans’: Understanding the Role of Quality of Work Life on Job Burnout and Job Satisfaction Relationship of Indian Doctors. Journal of Health Management 2019, 21, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barili, E.; Bertoli, P.; Grembi, V.; Rattini, V. Job Satisfaction among Healthcare Workers in the Aftermath of the COVID-19 Pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0275334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, E.; Widestrom, M.; Gould, J.; Fang, R.; Davis, K.G.; Gillespie, G.L. Examining the Impact of Stressors during COVID-19 on Emergency Department Healthcare Workers: An International Perspective. IJERPH 2022, 19, 3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selič-Zupančič, P.; Klemenc-Ketiš, Z.; Onuk Tement, S. The Impact of Psychological Interventions with Elements of Mindfulness on Burnout and Well-Being in Healthcare Professionals: A Systematic Review. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2023, 16, 1821–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamlub, S.; Harun-Or-Rashid, M.; Sarker, M.A.B.; Hirosawa, T.; Outavong, P.; Sakamoto, J. Job Satisfaction of Health-Care Workers at Health Centers in Vientiane Capital and Bolikhamsai Province, Lao PDR. Nagoya J Med Sci 2013, 75, 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Deshmukh, N.; Raj, P.; Chide, P.; Borkar, A.; Velhal, G.; Chopade, R. Job Satisfaction Among Healthcare Providers in a Tertiary Care Government Medical College and Hospital in Chhattisgarh. Cureus 2023, 15(6). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaferis, D.; Aletras, V.; Niakas, D.N. Job Satisfaction of Primary Healthcare Professionals: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Greece: Job Satisfaction in Greek Primary Care. Acta Biomed 2023, 94, e2023077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanis, P.; Moisoglou, I.; Katsiroumpa, A.; Vraka, I.; Siskou, O.; Konstantakopoulou, O.; Meimeti, E.; Kaitelidou, D. Increased Job Burnout and Reduced Job Satisfaction for Nurses Compared to Other Healthcare Workers after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Nursing Reports 2023, 13, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santinello, M. Link Burnout Questionnaire — LBQ; Giunti, O.S., Ed.; Organizzazioni Speciali: Firenze, Italia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, L.C.; Sloan, S.J.; Williams, S. OSI: Occupational Stress Indicator. Adattamento Italiano a cura di Saulo Sirigatti e Cristina Stefanile; 2002.

- Borsboom, D.; Deserno, M.K.; Rhemtulla, M.; Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I.; McNally, R.J.; Robinaugh, D.J.; Perugini, M.; Dalege, J.; Costantini, G.; et al. Network Analysis of Multivariate Data in Psychological Science. Nat Rev Methods Primers 2021, 1, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Borsboom, D.; Fried, E.I. Estimating Psychological Networks and Their Accuracy: A Tutorial Paper. Behav Res 2018, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S.; Fried, E.I. A Tutorial on Regularized Partial Correlation Networks. Psychological Methods 2018, 23, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hevey, D. Network Analysis: A Brief Overview and Tutorial. Health Psychol Behav Med 2018, 6, 301–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epskamp, S.; Cramer, A.O.J.; Waldorp, L.J.; Schmittmann, V.D.; Borsboom, D. Qgraph : Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. J. Stat. Soft. 2012, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AA.VV. (2024). JASP 0.18.3 software [Software]. https://jasp-stats.org/.

- Robinaugh, D.J.; Millner, A.J.; McNally, R.J. Identifying Highly Influential Nodes in the Complicated Grief Network. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2016, 125, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantini, G.; Perugini, M. Generalization of Clustering Coefficients to Signed Correlation Networks. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e88669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Horvath, S. A General Framework for Weighted Gene Co-Expression Network Analysis. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol 2005, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, M.; Fan, Y.; Di, Z. Characterizing Dissimilarity of Weighted Networks. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 5768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tantardini, M.; Ieva, F.; Tajoli, L.; Piccardi, C. Comparing Methods for Comparing Networks. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 17557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonnis, M.; Agus, M.; Corona, F.; Aru, N.; Urban, A.; Cortese, C.G. The Role of Fulfilment and Disillusion in the Relationship between Burnout and Career Satisfaction in Italian Healthcare Workers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, J.W.; Weatherly, R.A.; Girod, D.A.; Barber, C.E.; Tsue, T.T. A Longitudinal Study of Emotional Intelligence Training for Otolaryngology Residents and Faculty. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014, 140, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, R.; Stirling, J.; Adams, W. Promoting Wellness and Stress Management in Residents through Emotional Intelligence Training. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2018, 9, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foji, S.; Vejdani, M.; Salehiniya, H.; Khosrorad, R. The Effect of Emotional Intelligence Training on General Health Promotion among Nurse. J Edu Health Promot 2020, 9, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, G.; Bourke, L.; Rickard, M.J.F.X. Review of Emotional Intelligence in Health Care: An Introduction to Emotional Intelligence for Surgeons. ANZ Journal of Surgery 2020, 90, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharjee, A.; Ali, A.; Basu, A. Effectiveness Of Emotional Intelligence Training Programs For Healthcare Providers In Kolkata. EATP 2024, 3784–3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory. In P. A. M. Van Lange, A.W. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology: Volume 1; SAGE Publications Ltd.: London, UK, 2012; pp. 416–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Olafsen, A.H.; Ryan, R.M. Self-Determination Theory in Work Organizations: The State of a Science. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2017, 4, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Sanz-Vergel, A. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Ten Years Later. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2023, 10, 25–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | R | — | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| p-value | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Seniority of service | R | 0.684 | *** | — | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| p-value | < .001 | — | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Unused vacation days | R | 0.202 | *** | 0.177 | *** | — | |||||||||||||||||||||

| p-value | < .001 | < .001 | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Accumulated overtime hours | R | -0.002 | 0.034 | 0.287 | *** | — | |||||||||||||||||||||

| p-value | 0.960 | 0.465 | < .001 | — | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Psychophysical exhaustion-engagement | R | -0.053 | -0.004 | 0.057 | 0.058 | — | |||||||||||||||||||||

| p-value | 0.249 | 0.927 | 0.217 | 0.212 | — | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Relational deterioration-involvement | R | -0.157 | *** | -0.089 | -0.014 | -0.022 | 0.537 | *** | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| p-value | < .001 | 0.054 | 0.771 | 0.636 | < .001 | — | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Professional inefficacy-efficacy | R | 0.001 | -0.041 | 0.048 | -0.037 | 0.652 | *** | 0.500 | *** | — | |||||||||||||||||

| p-value | 0.998 | 0.381 | 0.298 | 0.428 | < .001 | < .001 | — | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Disillusion-fulfilment | R | -0.056 | 0.021 | 0.002 | 0.026 | 0.778 | *** | 0.563 | *** | 0.598 | *** | — | |||||||||||||||

| p-value | 0.228 | 0.647 | 0.959 | 0.578 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | — | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Career Satisfaction | R | 0.053 | -0.023 | -0.064 | -0.045 | -0.660 | *** | -0.460 | *** | -0.500 | *** | -0.720 | *** | — | |||||||||||||

| p-value | 0.252 | 0.624 | 0.168 | 0.332 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | — | ||||||||||||||||||

| 10. Satisfaction with the Job itself | R | 0.020 | 0.066 | -0.048 | -0.032 | -0.679 | *** | -0.513 | *** | -0.581 | *** | -0.669 | *** | 0.756 | *** | — | |||||||||||

| p-value | 0.670 | 0.157 | 0.303 | 0.491 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | — | |||||||||||||||||

| 11. Satisfaction with the setting and the Organizational Structure | R | 0.065 | -0.026 | -0.080 | -0.016 | -0.646 | *** | -0.456 | *** | -0.479 | *** | -0.664 | *** | 0.832 | *** | 0.704 | *** | — | |||||||||

| p-value | 0.161 | 0.570 | 0.086 | 0.734 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | — | ||||||||||||||||

| 12. Satisfaction with Organizational Processes | R | 0.083 | 0.029 | -0.027 | -0.039 | -0.693 | *** | -0.464 | *** | -0.540 | *** | -0.714 | *** | 0.842 | *** | 0.768 | *** | 0.835 | *** | — | |||||||

| p-value | 0.074 | 0.530 | 0.561 | 0.404 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | — | |||||||||||||||

| 13. Satisfaction with Interpersonal Relationships | R | 0.005 | -0.055 | -0.113 | * | -0.023 | -0.696 | *** | -0.384 | *** | -0.520 | *** | -0.688 | *** | 0.796 | *** | 0.699 | *** | 0.804 | *** | 0.801 | *** | — | ||||

| p-value | 0.907 | 0.234 | 0.015 | 0.629 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | — |

| Centrality measures per variable | Clustering measure per variable | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Betweenness | Closeness | Strength | Expected Influence | Zhang | ||||||

| 1 | Age | 1.641 | -0.679 | -0.008 | 0.753 | -1.475 | |||||

| 2 | Seniority of service | -0.949 | -0.957 | -0.436 | 0.776 | -0.475 | |||||

| 3 | Unused vacation days | 0.408 | -1.605 | -1.527 | -0.634 | -0.879 | |||||

| 4 | Accumulated overtime hours | -0.949 | -2.068 | -2.119 | -1.007 | -1.835 | |||||

| 5 | Psychophysical exhaustion-engagement | -0.085 | 0.696 | 0.889 | -0.355 | -0.281 | |||||

| 6 | Relational deterioration-involvement | 2.011 | 0.981 | -0.669 | -0.981 | 0.107 | |||||

| 7 | Professional inefficacy-efficacy | -0.949 | 0.642 | -0.461 | -0.412 | 0.801 | |||||

| 8 | Disillusion-fulfilment | 0.901 | 1.019 | 0.721 | -0.706 | -0.166 | |||||

| 9 | Career satisfaction | -0.209 | 0.526 | 0.985 | 1.180 | 0.898 | |||||

| 10 | Satisfaction with the job itself | -0.332 | 0.486 | 0.389 | -1.370 | 0.075 | |||||

| 11 | Satisfaction with the setting and the organizational structure | -0.949 | 0.204 | 0.519 | 1.638 | 1.593 | |||||

| 12 | Satisfaction with organizational processes | -0.702 | 0.247 | 1.135 | 1.294 | 0.874 | |||||

| 13 | Satisfaction with interpersonal relationships | 0.161 | 0.507 | 0.583 | -0.178 | 0.763 | |||||

| Variables | t | df | p | Cohen’s d | Group | Mean | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Age | 1.128 | 464 | 0.260 | 0.105 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 50.158 | 8.783 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 49.133 | 10.388 | ||||||

| 2 | Seniority of service | 2.617 | 464 | 0.009 | 0.245 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 20.015 | 10.428 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 17.319 | 11.454 | ||||||

| 3 | Unused vacation days | 1.771 | 463 | 0.077 | 0.166 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 27.713 | 35.252 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 22.087 | 32.914 | ||||||

| 4 | Accumulated overtime hours | -0.548 | 456 | 0.584 | -0.052 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 100.111 | 156.760 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 109.039 | 184.263 | ||||||

| 5 | Psychophysical exhaustion-engagement | -0.843 | 464 | 0.400 | -0.079 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 19.421 | 6.189 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 19.909 | 6.199 | ||||||

| 6 | Relational deterioration-involvement | 1.166 | 464 | 0.244 | 0.109 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 16.158 | 3.705 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 15.758 | 3.657 | ||||||

| 7 | Professional inefficacy-efficacy | -0.988 | 464 | 0.323 | -0.092 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 14.847 | 5.293 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 15.330 | 5.178 | ||||||

| 8 | Disillusion-fulfilment | 0.092 | 464 | 0.927 | 0.009 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 14.094 | 4.285 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 14.057 | 4.345 | ||||||

| 9 | Career satisfaction | -0.927 | 464 | 0.354 | -0.087 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 10.554 | 2.782 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 10.795 | 2.779 | ||||||

| 10 | Satisfaction with the job itself | 0.291 | 464 | 0.771 | 0.027 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 20.411 | 7.628 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 20.208 | 7.317 | ||||||

| 11 | Satisfaction with the setting and the organizational Structure | -0.405 | 464 | 0.686 | -0.038 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 15.916 | 5.685 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 16.125 | 5.408 | ||||||

| 12 | Satisfaction with organizational processes | -1.741 | 464 | 0.082 | -0.163 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 13.302 | 4.897 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 14.125 | 5.177 | ||||||

| 13 | Satisfaction with interpersonal relationships | 0.002 | 464 | 0.999 | 0.001 | 1 – Double caregiving yes | 17.569 | 8.142 |

| 2 – Double caregiving no | 17.568 | 7.669 |

| 1 – Double caregiving yes | 2 – Double caregiving no | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centrality | Clustering | Centrality | Clustering | ||||||||||

| Variable | Betweenness | Closeness | Strength | Expected influence | Zhang | Betweenness | Closeness | Strength | Expected influence | Zhang | |||

| 1 | Age | 1.853 | -0.484 | -0.165 | 0.646 | -1.705 | 1.572 | -0.752 | 0.022 | 0.910 | -1.280 | ||

| 2 | Seniority of service | -0.865 | -0.743 | -0.610 | 0.646 | -0.313 | -0.761 | -0.955 | -0.357 | 0.859 | -0.742 | ||

| 3 | Unused vacation days | 0.166 | -1.623 | -1.720 | -0.717 | -1.244 | 0.124 | -1.643 | -1.431 | -0.495 | -0.851 | ||

| 4 | Accumulated overtime hours | -0.865 | -2.097 | -2.123 | -0.923 | -1.820 | -0.761 | -1.927 | -2.015 | -1.130 | -1.577 | ||

| 5 | Psychophysical exhaustion-engagement | -0.584 | 0.977 | 0.963 | -0.550 | 0.128 | 0.124 | 0.762 | 0.778 | -0.320 | -0.528 | ||

| 6 | Relational deterioration-involvement | 2.134 | 1.051 | -0.283 | 0.025 | 0.636 | 1.814 | 0.996 | -0.994 | -1.721 | -0.327 | ||

| 7 | Professional inefficacy-efficacy | 0.072 | 0.754 | -0.228 | -0.580 | 0.744 | -0.681 | 0.602 | -0.473 | -0.260 | 0.525 | ||

| 8 | Disillusion-fulfilment | 0.541 | 1.039 | 0.681 | -0.705 | 0.108 | 1.572 | 1.136 | 0.808 | -0.802 | -0.353 | ||

| 9 | Career Satisfaction | -0.865 | 0.255 | 0.710 | 1.013 | 0.771 | -0.118 | 0.530 | 1.183 | 1.278 | 1.063 | ||

| 10 | Satisfaction with the job itself | -0.022 | 0.577 | 0.556 | -1.620 | -0.002 | -0.761 | 0.594 | 0.292 | -0.838 | 0.500 | ||

| 11 | Satisfaction with the setting and the organizational structure | -0.865 | 0.003 | 0.661 | 1.780 | 1.176 | -0.761 | -0.035 | 0.553 | 1.200 | 1.524 | ||

| 12 | Satisfaction with organizational processes | -0.584 | 0.015 | 1.048 | 1.317 | 0.674 | -0.761 | 0.417 | 1.107 | 1.156 | 1.113 | ||

| 13 | Satisfaction with interpersonal relationships | -0.115 | 0.277 | 0.511 | -0.331 | 0.848 | -0.600 | 0.274 | 0.527 | 0.163 | 0.934 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).