1. Introduction

Barrett’s Esophagus (BE) is the direct precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), the most common form of esophageal cancer in the U.S, which has increased by six-fold between 1975 and 2001.[

1] BE and EAC have the same well defined risk factors but in contrast to EAC, BE can be effectively treated using endoscopic techniques such as radiofrequency or cryotherapy ablation with 80-90% success rates.[

2,

3,

4] U.S. gastroenterology societies have published guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of BE, which include non-endoscopic alternatives to traditional esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for BE screening.[

5,

6] The underlying goal of BE detection is to reduce EAC mortalities by diagnosing pre-neoplastic disease, which can then be followed by either surveillance (non-dysplastic BE) or treatment (dysplasia) to effectively halt disease progression.[

5]

The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommends BE screening in patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) defined as ≥5 years of at least weekly symptoms, and ≥3 of the following risk factors: male sex, white race, age >50 years, tobacco smoking, obesity, and family history of BE or EAC in a first degree relative. Additionally, the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recommends screening in patients with any 3 or more of the same risk factors, without mandating chronic GERD as a prerequisite.[

5,

6] The prevalence of BE is estimated at 5.6% in the US population (around 18.5 million adults, based on population size of 331.9 million people in 2021).[

7,

8] Disease in a multi-risk factor population is estimated to be anywhere between 5-15%, however, given the historically low rates of BE screening, this is likely a gross underestimate.[

9] Literature shows only 10-30% of patients with chronic GERD who meet appropriate screening criteria undergo EGD, attributable to both patient and provider-related factors (e.g. invasiveness, need for sedation, under-reporting of heartburn symptoms, low familiarity of primary care physicians with BE).[

10,

11,

12] Non-endoscopic strategies for disease detection were developed to overcome these obstacles and to facilitate more wide-spread screening of at-risk patients by shifting testing to in-office settings. The strategy involves a two-step approach: 1. Administering a non-invasive, accurate, office-based triage test followed by, 2. Confirmatory EGD in those patients with a positive result from the triage test.

EsoGuard® (EG) is the first such test to be commercially available in the U.S. It utilizes DNA targeted Next Generation Sequencing (NGS), combined with a proprietary algorithm to examine the presence of aberrant methylation on two specific genes, for the qualitative detection of BE and EAC. The esophageal cell samples for EG analysis can be collected non-endoscopically using the 510(k)-cleared EsoCheck® (EC) device. The test has been clinically validated in multiple studies demonstrating sensitivity up to 92.9% and negative predictive value (NPV) of 98.6%.[

13,

14,

15] We now present the findings of a multicenter, prospective, observational study designed to evaluate the clinical utility of the test in a real-world population at high risk for BE/EAC.

2. Materials and Methods

This prospective, multi-center, observational study (

CLinical

Utility Study of EsoGuard® on Samples Collected with

EsoCheck® (EG/EC) as a Triage Test for Endoscopy to Identify Barrett’s Esophagus – CLUE; NCT06030180) is designed to collect real-world data from use of EC and EG among patients at high risk for BE/EAC according to U.S gastroenterology societies. The study methods have previously been described.[

16] To assess the clinical utility of EG/EC, provider decision impact was measured by the concordance between EG results (positive or negative) and the provider’s decision to recommend or not recommend the patient for subsequent EGD. Information on whether patients underwent their follow-up EGD was also documented, as a measure of compliance outcomes.

Study enrollment was across eight clinical sites, with a single independent ordering provider at each location. Two of the ordering providers were gastroenterologists, one a foregut surgeon, and the remaining five were primary care providers. The primary care providers referred patients to local endoscopists when they deemed EGD indicated based on EG results, and the specialists performed EGDs on their own patients when deemed indicated.

The follow-up period for each patient was up to 18 weeks after the EG result became available. The tolerability of the EC cell collection was measured by the rate of successful cell collections compared to the total attempted. Only patients recommended for BE screening per ACG or AGA criteria were eligible for study participation. Additionally, those with contraindications to EC cell collection (defined in the device Instructions for Use (IFU), available upon request from

https://www.luciddx.com/precancer-detection/esocheck) were excluded from participation. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the WCG Institutional Review Board (IRB tracking number 20222402). All participants signed informed consent prior to collection of any study information or cell samples.

EsoGuard® and EsoCheck®: EsoGuard is a laboratory developed test (LDT) performed in a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendment (CLIA) certified, College of American Pathologists (CAP) accredited, and New York State (NYS)-licensed laboratory (LucidDx Labs, Lake Forest, CA) that utilizes NGS sequencing combined with a proprietary algorithm to assess the presence of cytosine methylation at 31 different genomic locations on the vimentin (VIM) and Cyclin-A1 (CCNA1) genes. EG results are reported in a binary fashion (positive or negative) indicating presence or absence of methylation changes to suggest presence of BE or disease along the full BE to EAC progression spectrum. Quantity Not Sufficient (QNS) may be reported if the cell sample has insufficient DNA for EG analysis, or “unevaluable” if the sample fails quality control (QC) during laboratory processing. Patients with QNS or unevaluable samples were given the option to repeat cell collection.

EsoCheck is an FDA 510(k)-cleared swallowable ballon-capsule device designed for the non-endoscopic, circumferential, targeted sampling of mucosal cells from the distal esophagus that can then be analyzed for cytology or with biomarker assays like EG. Cell collection can be performed in any office setting without sedation and usually takes approximately 3 minutes (

Figure 1). The unique, balloon-capsule Collect+Protect™ technology ensures the specimen collected from the target region of the esophagus (distal 5 centimeters) is protected from contamination and dilution as it passes through the upper esophagus and oropharynx during retrieval of the device.

Statistical Analysis: Continuous variables are summarized using the number of observations (n), mean, standard deviation (SD), median, interquartile range (IQR), minimum, and maximum, along with total number of patients contributing values. Categorical variables are described by frequency of counts and percentages. The total number of applicable patients (N) are used as the denominator for percent calculations unless stated otherwise within a table footnote. Binomial exact two-sided 95% confidence intervals are calculated wherever relevant. Missing data points on BE/EAC risk factors were imputed as not present, wherever applicable.

Since provider decision impact was measured by the concordance between EG results and the decision for EGD referral/non-referral, only patients with either a positive or negative EG result were evaluated for this endpoint. Patients unable to successfully swallow the EC device and patients with QNS or unevaluable samples were included in the summary of baseline characteristics, EC tolerability, and EG results, but did not contribute to the analysis of provider decision impact.

3. Results

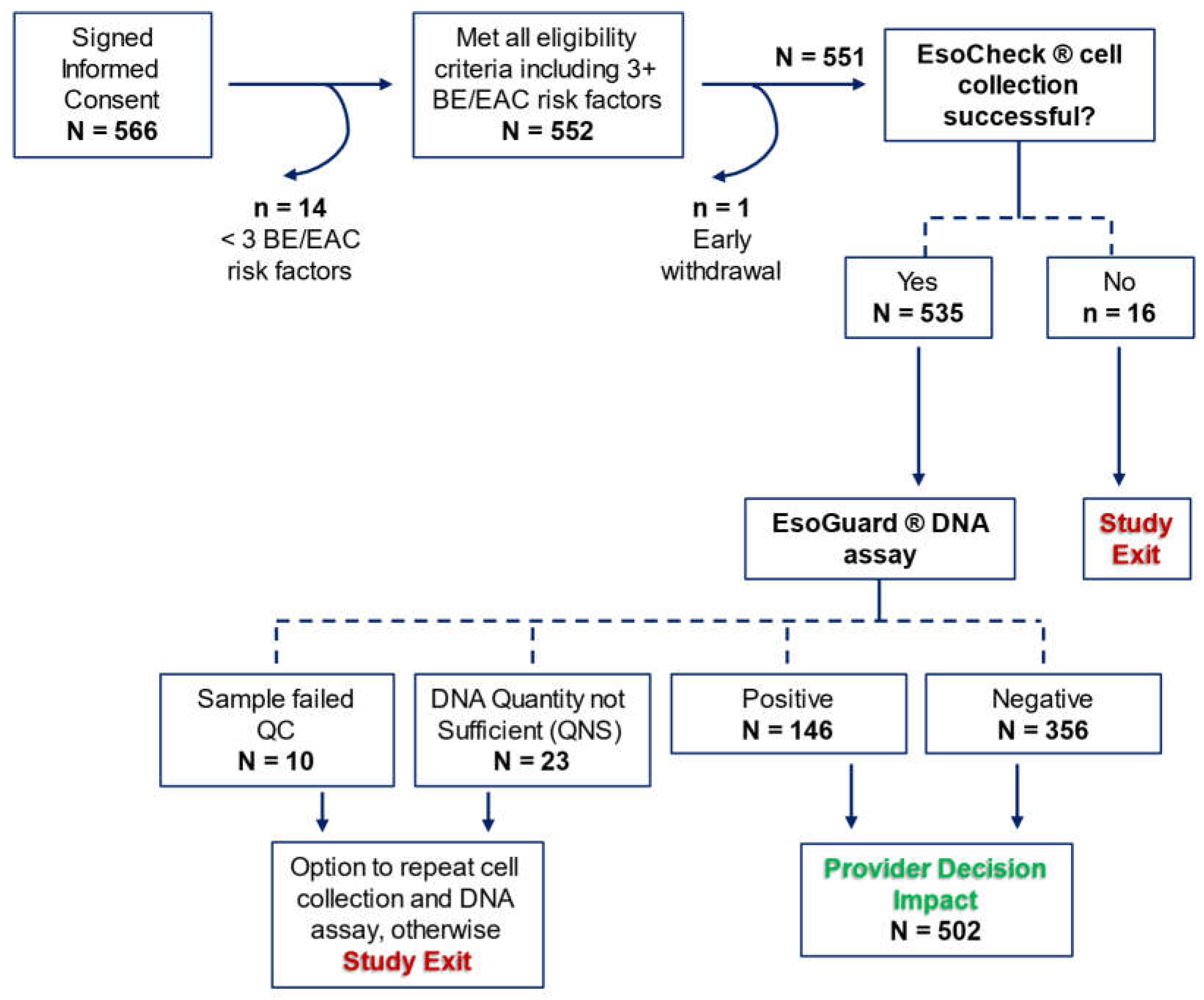

There were 566 patients who consented to study participation, among which 14 were later discovered to fail eligibility criteria, and one withdrew consent prior to initiation of study procedures. Among the 551 who attempted EC cell collection, 97.1% (n = 535) successfully provided a sample. Binary EG results were available for 93.8% (502/535) of the cell samples, and these patients contributed to the assessment of provider decision impact.

Figure 2 details participant disposition in the study.

Baseline characteristics are summarized in

Table 1 for the 551 patients who underwent EC. Mean age was 62.0 ± 12.4 years; 58.4% (n = 322) were male, 67.5% (n = 372) were White, 87.1% (n = 480) had chronic GERD, 59.9% (n = 330) were obese, 53.7% (n = 296) had tobacco smoking history (either former or current smoker), and 4.7% (n = 26) had a family history of BE or EAC. Patients meeting ACG risk criteria for BE and EAC, the “ACG cohort” accounted for 56.1% (309/551) of study participants.

A summary of metrics from the EC cell collection and EG assay are summarized in

Table 2. EC was successful in 97.1% (535/551) of patients, with a median cell collection duration of four minutes. The EG positivity rate was 27.3% (n = 146), 4.3% (n = 23) of samples were QNS, and 1.9% (n = 10) of samples failed QC.

Patients with binary EG results were included in the assessment of provider decision impact, which is summarized in

Table 3a (all evaluable patients) and

Table 3b (evaluable patients meeting ACG guideline criteria for BE/EAC screening). One hundred percent of EG positive patients were recommended/referred for EGD by their EG ordering providers. Among the 356 patients with negative EG results, only three were referred for follow-up EGD, all of whom required the EGD for non-screening purposes. One patient underwent the EGD prior to anti-reflux surgery, and the other two patients underwent diagnostic EGD for evaluation of intractable GERD symptoms.

Data was collected on patient follow-up among those referred for EGD after a positive EG result. Overall, 28.1% (n = 41) failed to undergo EGD for the reasons summarized in

Table 4a (

all EG positive patients) and

Table 4b (EG positive patients meeting ACG criteria). One patient died (0.7%) of unrelated causes before the EGD could be performed, four patients (2.7%) were referred by primary care to a gastroenterologist for EGD but were informed by the specialist that an EGD was not immediately necessary, and nine patients (6.2%) delayed the EGD due to more pressing comorbid medical conditions. Among the remaining 27 patients, nine were lost to follow-up and the rest refused EGD (

Table 4a).

Patient compliance with follow-up EGD was calculated after first excluding patients who died before the procedure could be performed, deferred the procedure due to comorbid health issues, the endoscopist did not deem EGD warranted, and those with incomplete data due to loss to follow-up (indicated by gray rows in

Table 4a and

Table 4b). Compliance was 85.4% (105/123) in the full EG positive population, and 85.1% (63/74) in the ACG cohort. Older patients within this cohort (i.e., those of Medicare-eligible age) were similarly compliant, with 85.2% (46/54) undergoing the recommended follow-up procedure.

Table 4b.

EsoGuard (+) patient compliance outcomes following referral for EGD: ACG cohort.

Table 4b.

EsoGuard (+) patient compliance outcomes following referral for EGD: ACG cohort.

| Full ACG cohort (n = 86) |

|---|

| Did the patient undergo an upper endoscopy procedure? |

|

| Yes* |

73.3% (63/86) |

| No |

26.7% (23/86) |

| Why was endoscopy not performed? |

|

| Patient refused |

47.8% (11/23) |

| Deferred due to health/comorbid conditions |

26.1% (6/23) |

| Patient lost to follow-up |

26.1% (6/23) |

| Overall compliance |

63/74 = 85.1%

|

| |

| Medicare-eligible (aged 65 years or older) sub-group of ACG cohort (n = 60) |

| Did the patient undergo an upper endoscopy procedure? |

|

| Yes* |

76.7% (46/60) |

| No |

23.3% (14/60) |

| Why was endoscopy not performed? |

|

| Patient refused |

57.1% (8/14) |

| Deferred due to health/comorbid conditions |

28.6% (4/14) |

| Patient lost to follow-up |

14.3% (2/14) |

| Overall compliance |

46/54 = 85.2%

|

*One patient who underwent EGD was unable to fully complete the procedure due to respiratory instability; at the time of study end, this patient was pending re-scheduling of a repeat EGD

The gray rows indicate patients for whom EGD was not performed due to factors beyond their own control. |

4. Discussion

DNA biomarkers and non-endoscopic cell collection devices for detecting BE such as EG and EC (respectively) may serve an important role in combating the low penetrance of EGD-based BE screening that has resulted in the ever-increasing incidence of EAC. We report on the clinical utility of EG/EC in real-world use across eight clinical centers as demonstrated by provider decision impact. Additionally, we report outcomes utility, measured by patient compliance with recommended EGD following a positive EG result. Our data demonstrates EC is effective for in-office esophageal cell sample collection, and providers are consistently utilizing EG as a triage to EGD in patients at-risk for BE and EAC who do not otherwise have an indication for urgent diagnostic upper endoscopy. Following a positive EG result, patient compliance with follow-up EGD was 85.4%, which contrasts starkly with the 10-30% of at-risk patients that typically undergo EGD for BE evaluation.[

10,

11,

12] This data supports EC/EG as a reasonable alternative to screening EGD for more widespread and easily accessible testing in patients who meet criteria established by gastroenterology society guidelines. It may be especially useful in the primary care population to guide referrals.

In our population, 99.2% (353/356) of patients with negative EG results were not referred for further diagnostic workup, reflecting provider confidence in the negative predictive value of the assay. The number of EGDs that would otherwise have been required to evaluate the same volume of patients for disease is effectively reduced. There were three (3) EG negative patients who did undergo EGD; all were for non-screening purposes (one was required prior to anti-reflux surgery, the other two for severe reflux symptoms), and not due to concern of false negative results. Among patients who were EG positive, 100% were recommended for EGD (or referred to a specialist for EGD evaluation, in the case of primary care providers). The high concordance between EG results and the ordering provider’s decision for EGD referral demonstrates strong provider decision impact. These patterns indicate the ordering providers are utilizing EG as a triage to EGD, and in doing so, can take a more intentional approach to how endoscopy resources are allocated for the purpose of diagnosing BE.

Follow-up data showed 85.4% (105/123) of EG positive patients underwent the recommended confirmatory EGD. The incidence of patients being “lost to follow-up” was low, at 6.2% (n = 9); all except one of the patients were tested in the primary care setting. There were four patients (2.7%) referred to a gastroenterologist from the primary care setting who were not scheduled for EGD based on the specialists’ judgement. All four met AGA but not ACG criteria for high risk of BE/EAC. In three of the four, the ACG guideline criteria were not met either due to insufficient chronicity of GERD symptoms (n = 2), or absence of GERD (n = 1). In the fourth individual, GERD symptoms were chronic but well-controlled on acid-suppressive medications, and the patient was young (aged 39 years); other risk factors were white race and previous history of tobacco smoking. One patient died of a comorbid condition before EGD could be performed (0.7%), and nine (6.2%) deferred EGD due to comorbid health issues. These patients were not counted as “non-compliant,” given that follow-up data was either missing, or the patient had indeed complied with follow-up referral but the endoscopist decided not to move forward.

The remaining 18 patients (12.3%) simply refused EGD; four of these cited fear of the procedure and sedation, six expressed concern about potential cost, while the others did not clarify their reasons. This resulted in an EGD non-compliance rate of 14.6% (18/123). Non-compliance rates were similar in the cohort who met ACG guideline criteria for BE screening (14.9%; 11/74), including in the sub-group aged 65 years or older (14.8%; 8/54). The rates for follow-up EGD of over 85% in EG positive patients is notably higher than typical rates of screening EGD being performed in the eligible U.S population. Given that only 10-30% of chronic GERD patients in the literature undergo endoscopic evaluation for BE, our observed EGD compliance rates demonstrate a 2.8 to 8.5-fold increase.[

10,

11,

12]

When comparing rates of follow-up in the EG positive cohort to that of other biomarker-based screening tests, results are similar or better. A retrospective study of claims data (2006-2020) for patients enrolled in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening showed the rate of follow-up colonoscopy within 6 months after a positive stool-based test was 65%.[

17] Colonoscopy compliance was 46% for those with a positive fecal immunochemical test (FIT), and 72% for those with a positive multi-target stool DNA (mt-sDNA) test (i.e., Cologuard). In a different published retrospective analysis of claims data (2015-2021), one-year follow-up colonoscopy rates after a positive stool-based test was shown to be only 53.4% among average-risk individuals, and significantly lower in those with comorbidities (hazard ratio 0.64).[

18] In the same data set, compliance with colonoscopy was higher among those who screened positive with DNA-based tests than with FIT (hazard ratio 1.63). Finally, in a third study utilizing comprehensive retrospective data, compliance with colonoscopy after a positive FIT test was 42.6% and 84.9% after a positive mt-sDNA test.[

19] Findings consistently demonstrated higher compliance in the patients who tested positive in DNA-based test compared to FIT. Along with the observations from our own study, the data may suggest that patient attitudes and confidence in DNA-based biomarkers contribute to increased urgency and compliance with provider-recommended follow-up endoscopy.

This study has some limitations. First, factors such as race and ethnicity may be inaccurately documented since they rely on patient self-report, and the electronic data capture system did not allow documentation of multiple ethnic backgrounds. For purposes of counting BE/EAC risk factors, patients were documented as “white” only if they were Caucasian non-Hispanic without mixed ethnicity. Additionally, among the 480 patients who were reported to have a history of GERD, 22 (4.6%) did not provide information on the duration and/or frequency of their symptoms, and therefore it is unknown if they met definitions for “chronic” disease. As a conservative approach, these patients were imputed as non-chronic when assessing who met criteria for inclusion in the ACG analysis cohort. This could therefore have led to an underestimate of the number of patients meeting ACG guideline criteria for BE screening. Consequences are likely minimal, given the consistency of provider decision across all study cohorts. Finally, among patients who were non-compliant with EGD, the reason for refusal was unavailable for nearly half (8/18). However, this number is low compared to published studies on patient willingness to undergo EGD for BE screening, where patient surveys showed 20.4% endorsed fear of the procedure as a key barrier.[

20]

5. Conclusions

The goal of BE screening and early detection is to facilitate appropriate surveillance and treatment, given the known risk for EAC progression and the mortality associated with it. Improved BE detection requires more widespread testing of at-risk individuals utilizing a combination of both non-endoscopic and endoscopic strategies, as supported by existing gastroenterology society guidelines. Experience from this CLUE study demonstrates EC is easy to implement for non-endoscopic in-office esophageal cell sampling, and the EG methylated DNA assay is effective in guiding provider decision-making. Patients with positive test results also demonstrate high compliance with recommended follow-up endoscopy. EC/EG may be particularly useful in the primary care setting where triaging patients to or away from EGD would allow more efficient allocation of resources.

Author Contributions

DL – Conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing—review and editing; AF – investigation, writing—review and editing; SM – investigation, writing—review and editing; PSB – investigation, writing—review and editing; BL – investigation, writing—review and editing; VTL – Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation; BJD – Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing; SV – validation, formal analysis, writing—review and editing; LA – Conceptualization, methodology, writing—review and editing, funding acquisition.

Funding

This research was funded by Lucid Diagnostics Inc.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the WCG Institutional Review Board (IRB tracking number 20222402).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to patient privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

DL – Consultant for Lucid Diagnostics Inc., Castle Biosciences, Laborie, and Merit Endotek; AF – None; SM – None; PSB – None; BL – None; VTL – Executive employee and shareholder – Lucid Diagnostics; BJD – Executive employee and shareholder – Lucid Diagnostics; SV – Executive employee and shareholder – Lucid Diagnostics; LA – Executive employee, Board member, and shareholder – Lucid Diagnostics

References

- Pohl, H. and H.G. Welch, The role of overdiagnosis and reclassification in the marked increase of esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2005. 97(2): p. 142-6.

- Shaheen, N.J., et al., Durability of radiofrequency ablation in Barrett's esophagus with dysplasia. Gastroenterology, 2011. 141(2): p. 460-8.

- Shaheen, N.J., et al., Safety and efficacy of endoscopic spray cryotherapy for Barrett's esophagus with high-grade dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc, 2010. 71(4): p. 680-5.

- Shaheen, N.J., et al., Radiofrequency ablation in Barrett's esophagus with dysplasia. N Engl J Med, 2009. 360(22): p. 2277-88.

- Shaheen, N.J., et al., Diagnosis and Management of Barrett's Esophagus: An Updated ACG Guideline. Am J Gastroenterol, 2022. 117(4): p. 559-587.

- Muthusamy, V.R., et al., AGA Clinical Practice Update on New Technology and Innovation for Surveillance and Screening in Barrett's Esophagus: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2022. 20(12): p. 2696-2706.e1. [CrossRef]

- Hayeck, T.J., et al., The prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in the US: estimates from a simulation model confirmed by SEER data. Dis Esophagus, 2010. 23(6): p. 451-7.

- Kuipers, E.J., Barrett esophagus and life expectancy: implications for screening? Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y), 2011. 7(10): p. 689-91.

- Runge, T.M., J.A. Abrams, and N.J. Shaheen, Epidemiology of Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterol Clin North Am, 2015. 44(2): p. 203-31. [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, A.K., D.A. Katzka, and P.G. Iyer, Endoscopic Screening for Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: Rationale, Candidates, and Challenges. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am, 2021. 31(1): p. 27-41.

- Eluri, S., et al., Low Prevalence of Endoscopic Screening for Barrett's Esophagus in a Screening-Eligible Primary Care Population. Am J Gastroenterol, 2022. 117(11): p. 1764-1771.

- Stewart, M., et al., Missed opportunities to screen for Barrett's esophagus in the primary care setting of a large health system. Gastrointest Endosc, 2023. 98(2): p. 162-169. [CrossRef]

- Moinova, H.R., et al., Identifying DNA methylation biomarkers for non-endoscopic detection of Barrett's esophagus. Sci Transl Med, 2018. 10(424). [CrossRef]

- Moinova, H.R., et al., MULTICENTER, PROSPECTIVE TRIAL OF NON-ENDOSCOPIC BIOMARKER-DRIVEN DETECTION OF BARRETT'S ESOPHAGUS AND ESOPHAGEAL ADENOCARCINOMA. Am J Gastroenterol, 2024.

- Greer, K.B., et al., Non-endoscopic screening for Barrett's esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma in at risk Veterans. Am J Gastroenterol, 2024.

- Dan Lister, A.F., Shail Maheshwari, Paul S. Bradley, Victoria T. Lee, Brian J. deGuzman, Suman Verma, Lishan Aklog., Clinical Utility of EsoGuard® on Samples Collected with EsoCheck® as a Triage to Endoscopy for Identification of Barrett’s Esophagus – Interim Data from the CLUE Study. Archives of Clinical and Biomedical Research, 2023. 7: p. 626-634. [CrossRef]

- Austin, G., et al., Patterns of initial colorectal cancer screenings after turning 50 years old and follow-up rates of colonoscopy after positive stool-based testing among the average-risk population. Curr Med Res Opin, 2023. 39(1): p. 47-61. [CrossRef]

- Mohl, J.T., et al., Rates of Follow-up Colonoscopy After a Positive Stool-Based Screening Test Result for Colorectal Cancer Among Health Care Organizations in the US, 2017-2020. JAMA Netw Open, 2023. 6(1): p. e2251384. [CrossRef]

- Finney Rutten, L.J., et al., Colorectal cancer screening completion: An examination of differences by screening modality. Prev Med Rep, 2020. 20: p. 101202. [CrossRef]

- Kolb, J.M., et al., Patient Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Barriers to Barrett's Esophagus Screening. Am J Gastroenterol, 2023. 118(4): p. 615-626.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).